Magda Maaoui

Magda Maaoui

Magda Maaoui

What we can learn from elsewhere

to fix New York’s housing crisis

Description

At Home and Abroad examines the diverse approaches to housing across cultural, political, and economic contexts. In a selection of cities across the globe, students pull from different housing systems, and probe how each one responds to local problems–and sometimes, creates new ones. We invert the usual lists of best practices, prioritizing traveling policies that move from South to North, and taking lessons from housing actors beyond the usual suspects. What makes New York a good laboratory for this inquiry? The scale of its housing crisis, paired with the relentless attempts at solving it.

Studio Instructor

Magda Maaoui

Teaching Associate

Elmo Tumbokon

Students

Roua Atamaz Sibai, Schola Eburuoh, Nour El Zein, Jo Fang, Karthik Girish, Ellie Lauderback, Issa Lee, Giovanna Lia Toledo, Daniel Mellow, Sulaya Ranjit, Sebastián Rodriguez, Jada Rossman, Meagan Tan Jingchuu, Elmo Tumbokon, Sophia Zhang

Final Review Critics

Clara Parker, Zayba Abdulla Polina Bakhteiarov, Heather Beck, Maia Berlow, Laura Capucilli, Julie Chou, Julian St. Patrick Clayton, Allan Co, Jacob Dugopolski, Koray Duman, Erik Forman, Rachel Goodfriend, Palak Kaushal, John Kimble, Teddy Kofman, Joel Kolkmann, Allison Lane, Kenny Lee, Emily Lehman, Rebecca Macklis, Samantha Maldonado, Hallie Martin, Maulin Mehta, Alexa Mendel, Sylvia Morse, Nasra Nimaga, Delma Palma, Marcella Pena, Franz Prinsloo, Sadia Rahman, Neil Reilly, Doug Rose, Amy Schaap, Wendi Shafran, Ellen Shakespear, Kavya Shankar, Ashley Smith, Sarah Solon, Adán Soltren, Lauren Stander, Jennifer Tausig, Eli Tedesco, Catherine Vaughan, Silvia Vercher Pons, Nicole Vlado Torres, Laura Wainer, Trax Wang, Pablo Zevallos.

53

Magda Maaoui

Configuring Coalitions

Nour El Zein, Karthik Girish

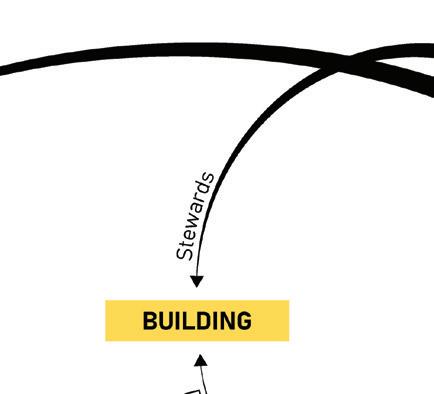

Building Housing Easier and Faster in NYC

Daniel Mellow, Sulaya Ranjit

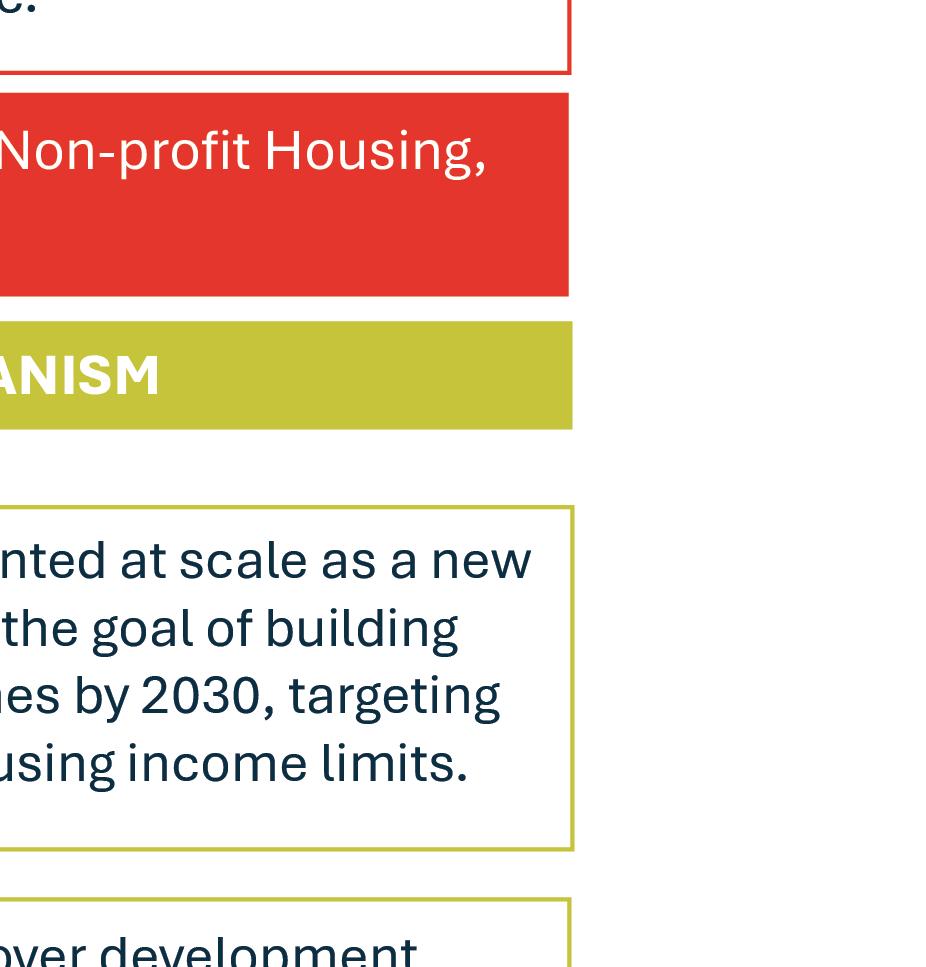

78 Expanding the Housing Affordability Patchwork

Roua Atamaz Sibai, Ellie Lauderback, Jada Rossman

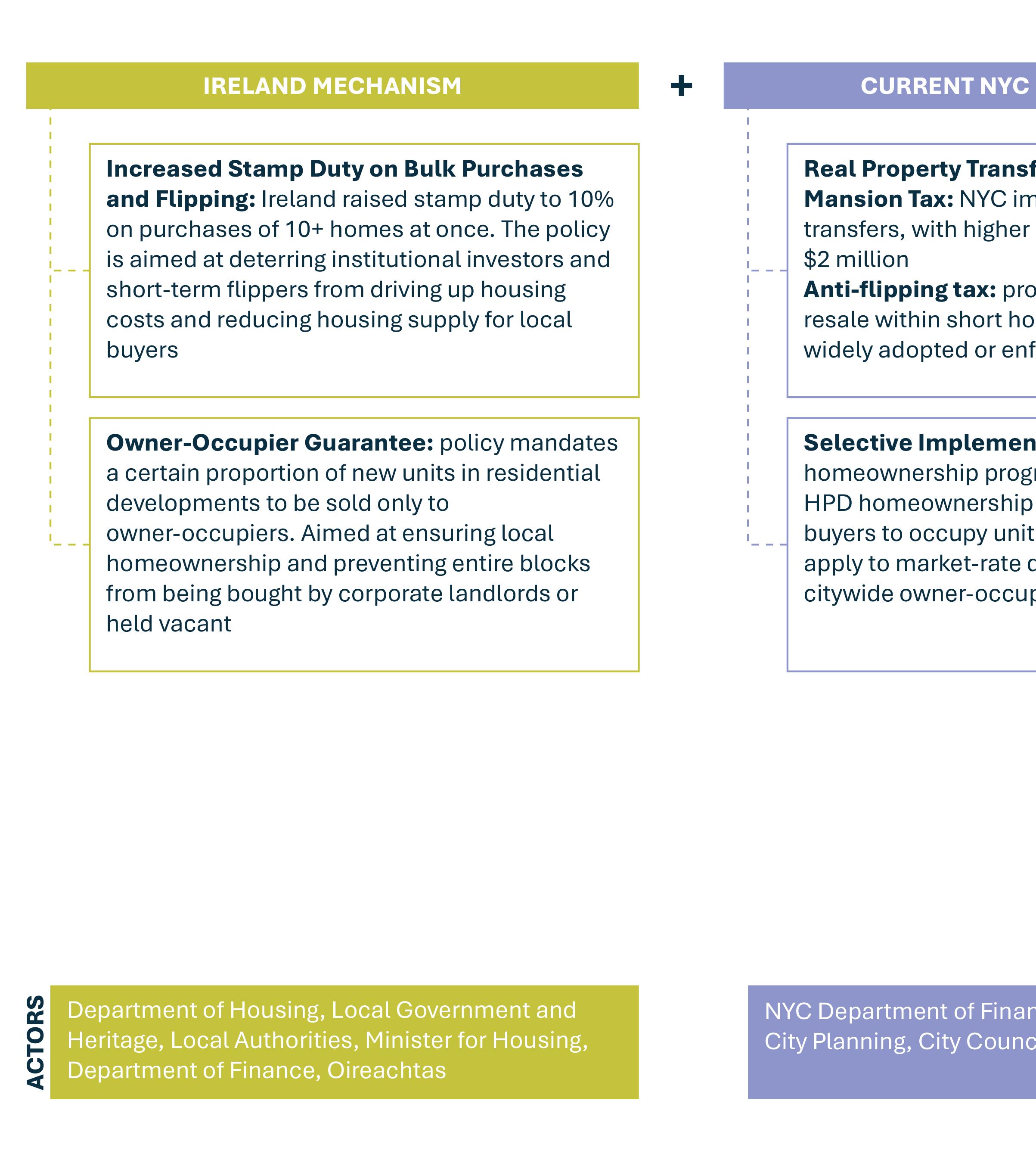

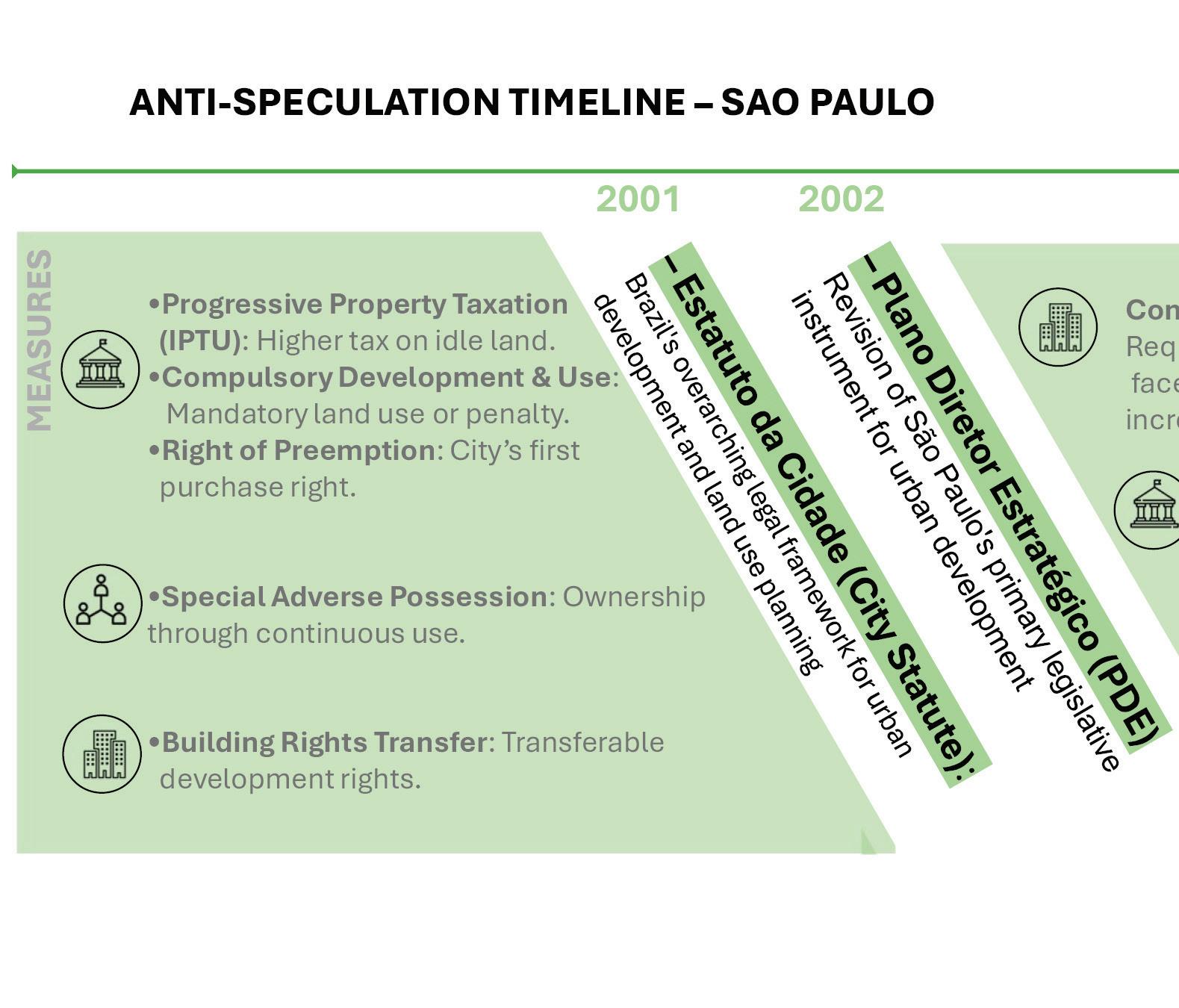

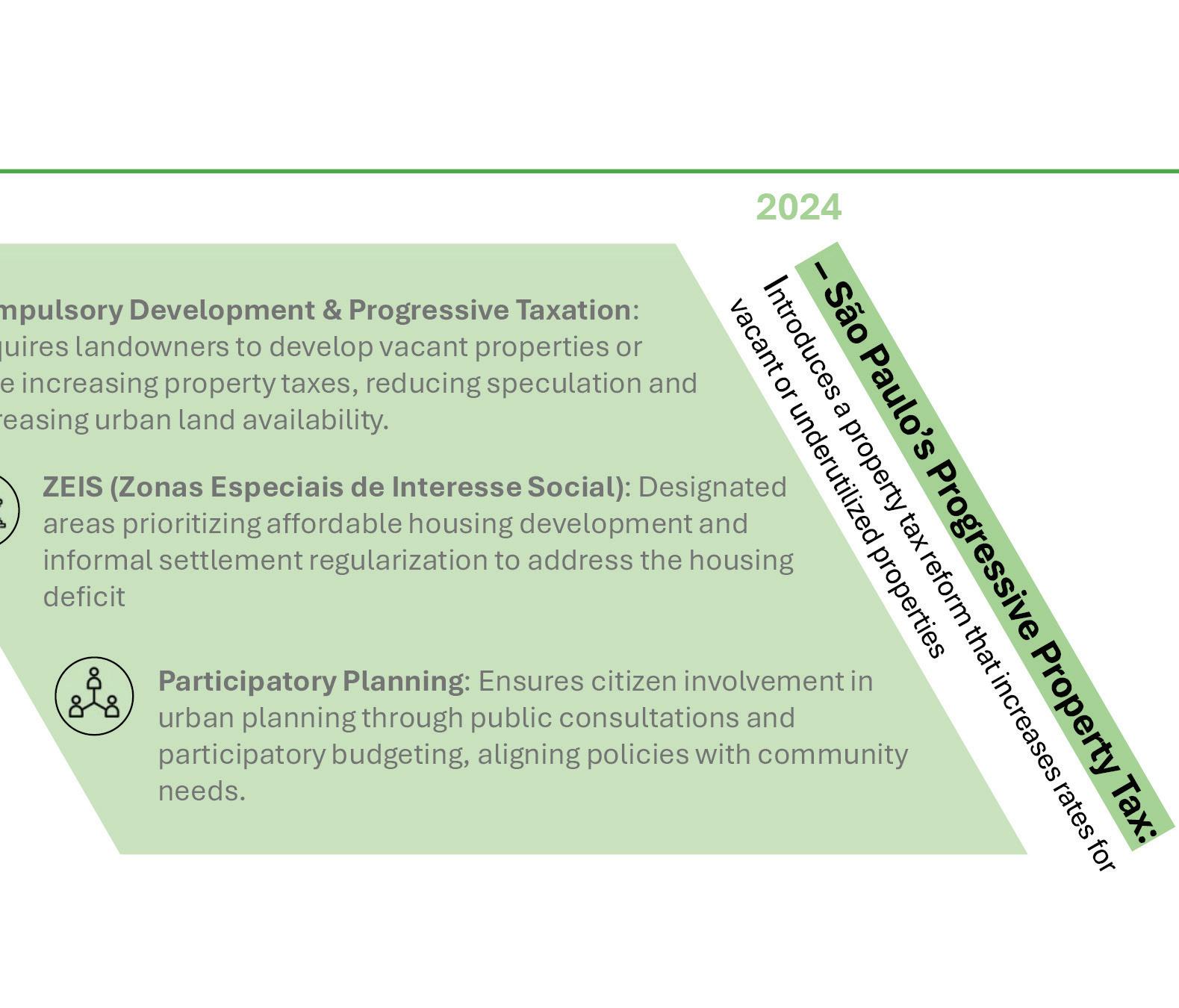

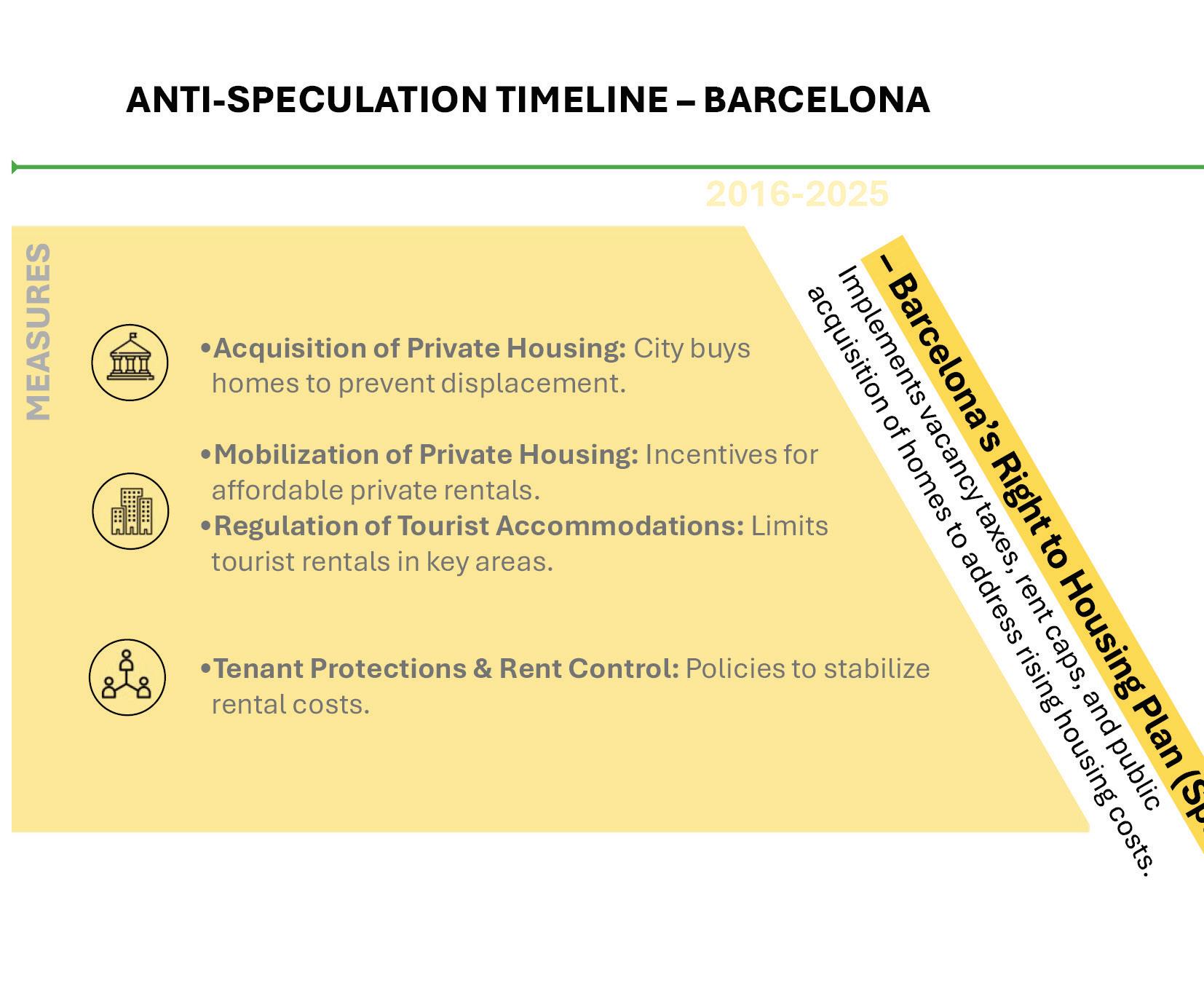

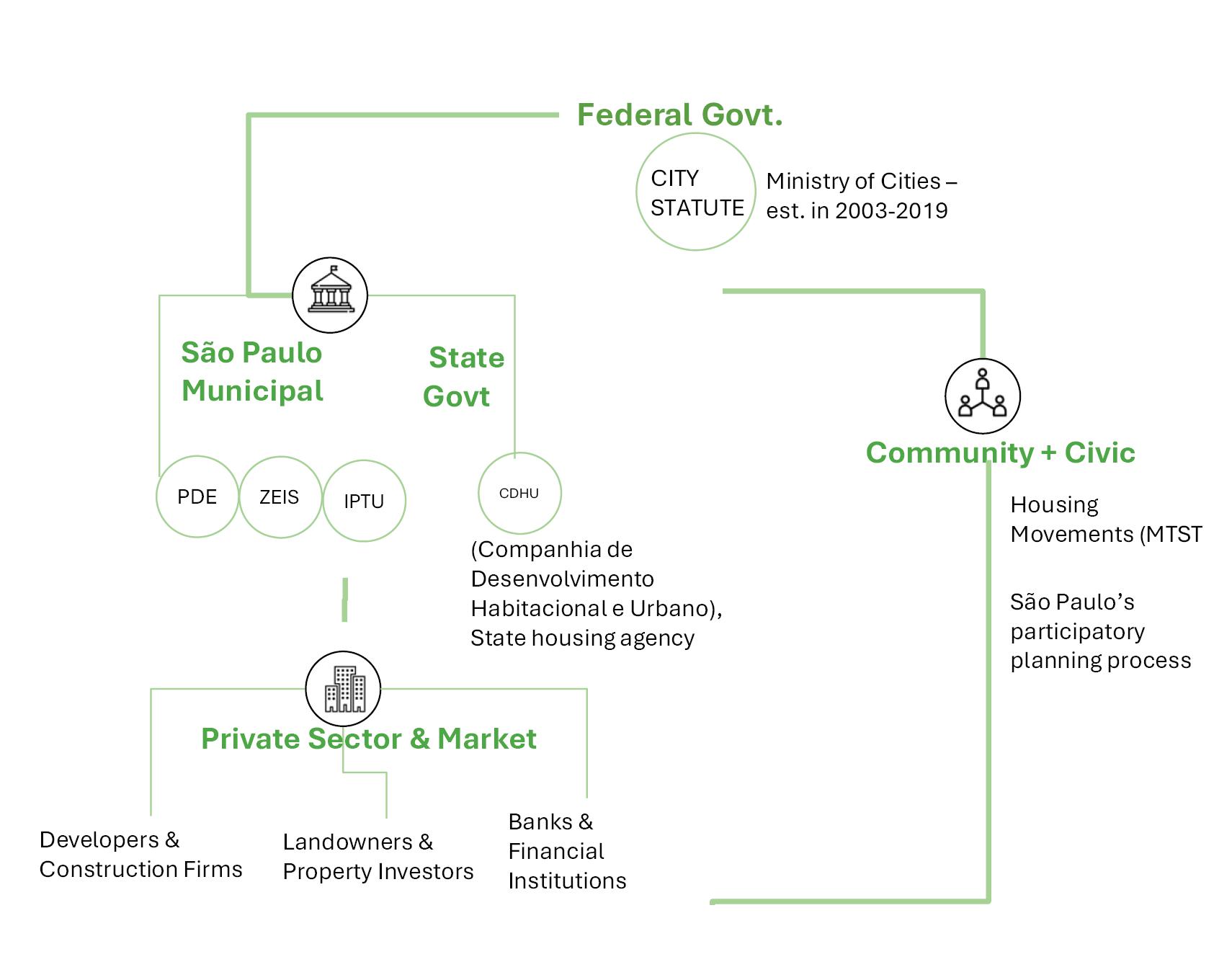

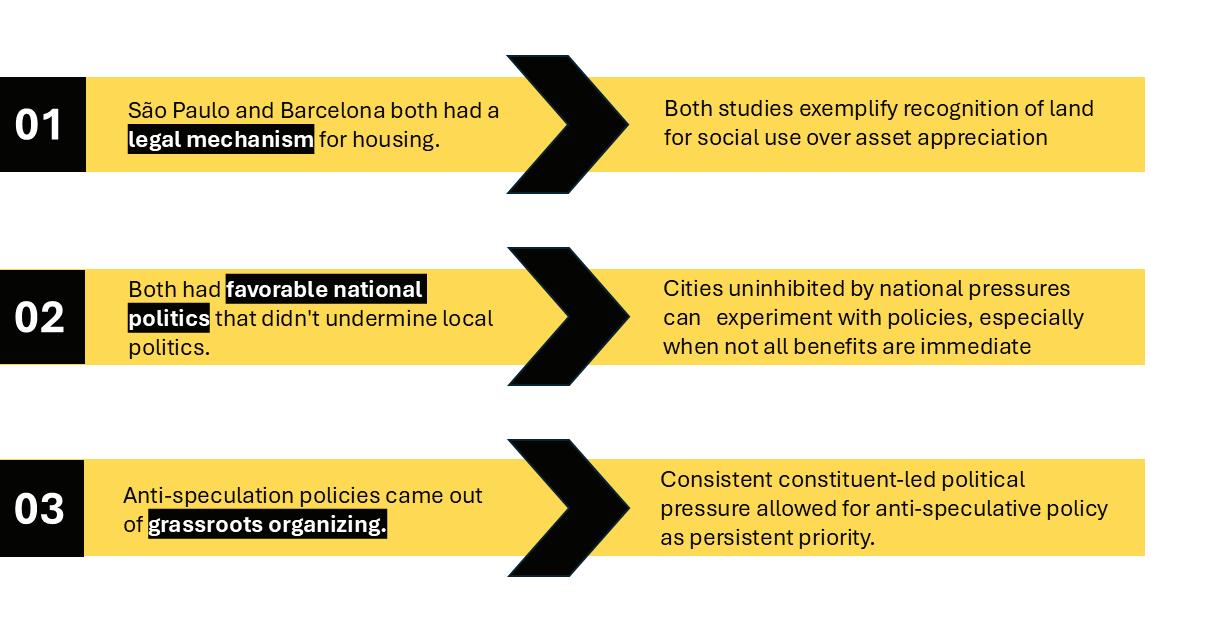

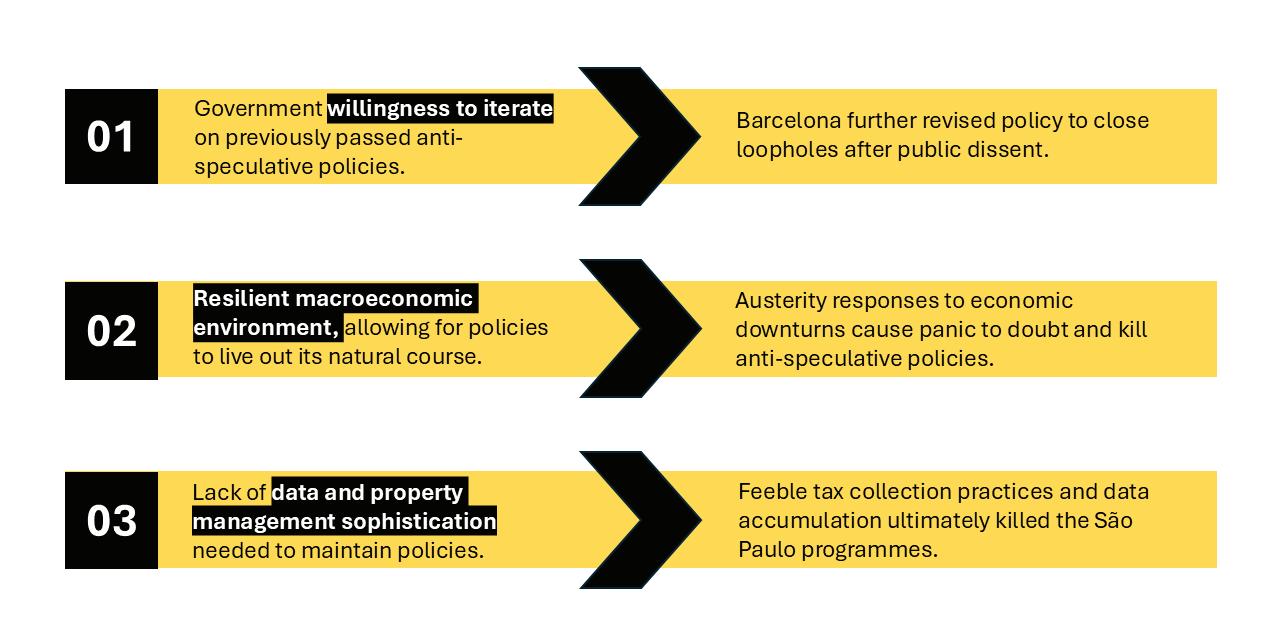

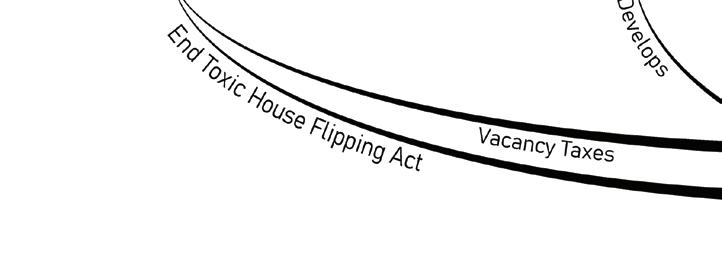

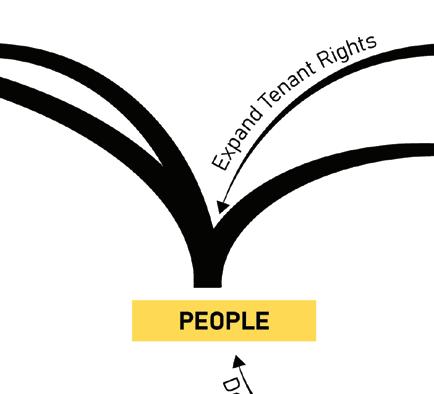

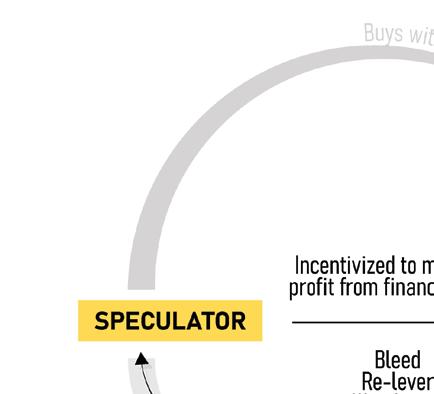

129 The Case(s) for Anti-Speculation

Schola Chioma Eburuoh, Jo Fang, Elmo Tumbokon

160 Mitigating Housing Constraints for Undocumented Migrants

Meagan Tan Jingchuu, Juan Sebastian Rodriguez Leon, Giovanna Lia Toledo

190 Scaling Modular Passive Housing in New York City

Issa Lee, Sophia (Guangzhao) Zhang

Magda Maaoui

Magda Maaoui General

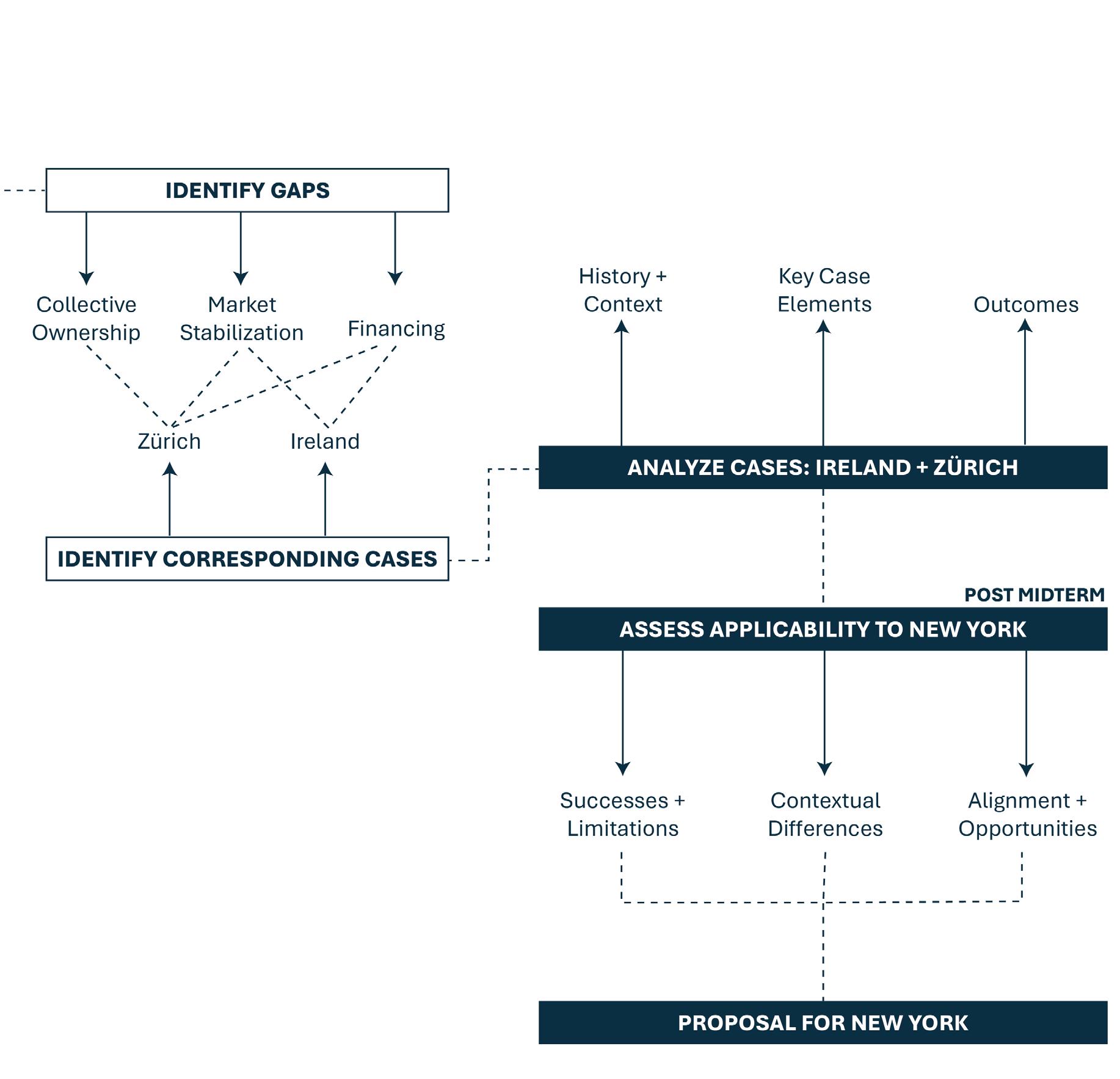

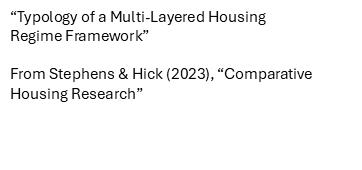

The course At Home and Abroad examines diverse approaches to housing across cultural, political, and economic contexts. In a selection of cities across the globe, students have learned from different housing systems how each one responds to local problems—and sometimes, creates new ones. During the Spring of 2025, we inverted the usual lists of best practices, prioritizing traveling policies that move from South to North, and taking lessons from housing actors beyond the usual suspects.

A unique feature of this course was the opportunity to work in tandem with the New York-based organization the Urban Design Forum. Students were paired with groups of Forum fellows as they set out to analyze international housing models and extract valuable lessons for addressing NYC’s ongoing housing crisis. What made New York a good laboratory for this inquiry? The scale of its housing crisis, paired with the relentless attempts at solving it. This provided students a chance to apply classroom knowledge to real-world challenges, and connect in real time with practitioners taking those challenges on.

In class, we divided our time between discussion and action. In addition to our work with the Urban Design Forum, each week we debated essential readings in comparative housing studies. We covered models in affordability, sustainability, governance, and financing. Students engaged with a variety of theoretical frameworks, case studies, and policy transfer stories. They completed the course with an understanding of how housing solutions are influenced by local, national, and transnational conditions—and how, in turn, they shape the fate of cities. Case studies included housing cooperatives in Uruguay and India, zoning reformers in New Zealand, Japanese aging-in-place strategies, Lebanon’s financialization of urban development, France’s social housing models, and so on. We also incorporated examples students chose

in each of our sessions.

The conceptual foundation of this course stems from a 2019 workshop I co-organized, titled “Atlantic Crossings Revisited” on the theme of transatlantic planning and the circulation of housing best practices. Inspired by the seminal work of Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Policy in a Progressive Age (2000), the event explored how urban and social policies have traversed the Atlantic in both directions to shape our increasingly connected urban regions. This workshop’s ambition was to start a dialogue that would help ensure policy solutions can be properly situated historically, translated, adapted, and implemented for the good of all. The notion of model which I mobilized in that workshop referred to a group of objects, policies, urban doctrines, sets of “best practices” or labels that all shared the same characteristic: that of being a reference or standard for imitation and reproduction, from one context of origin to a set of other contexts for which the policy had not initially been designed (Choay 1965). In Atlantic Crossings. Rodgers traced the genealogy of progressive policy transfers between North America and Europe. He wrote that “one finds oneself pulled into an intense, transnational traffic in reform ideas, policies, and legislative devices” (2000, 3). He gave scholars and practitioners alike a roadmap for future transatlantic work as “one begins to rediscover a largely forgotten world of transnational borrowings and imitation, adaptation and transformation” (2000, 7). In the course At Home and Abroad, we take this challenge one step further by decentering the standard comparative prisms, and situating these circulations from the Global South.

This class explicitly sought to include students from across the Graduate School of Design’s programs, and beyond. By the end of the course, students were able to:

1. Develop a comprehensive understanding of

2. Critically analyze and compare housing policies and practices across different regions

3. Evaluate the role of housing in promoting or hindering social equity, better health outcomes, and environmental justice

4. Synthesize cross-cultural perspectives to address housing challenges

5. Collaborate with industry leaders as they engage directly with ongoing efforts to transform NYC’s housing landscape

6. Debate whether we can produce a clearly identifiable set of “best practices” given the global diversity of contexts, institutional arrangements, and intractable challenges cities are faced with, which themselves are constantly changing

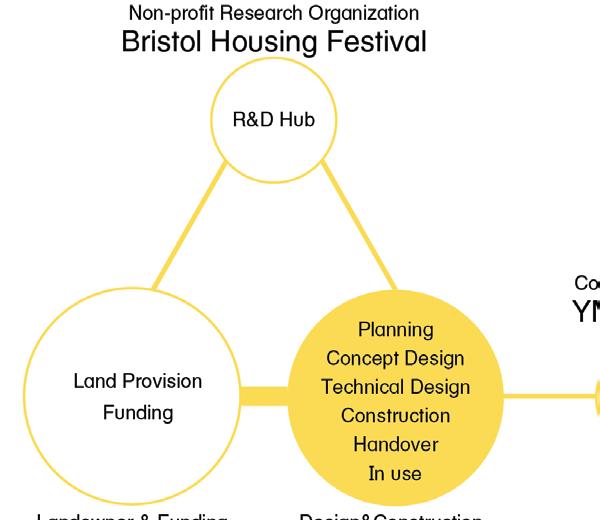

The Urban Design Forum is a member-powered organization of 1,000+ civic leaders committed to a more just future for NYC. They bring together New Yorkers of diverse backgrounds and experiences to learn, debate, and design a vibrant city for all. They believe interdisciplinary cohorts of emerging leaders can empower more diverse leadership in the design and development professions. They also believe New York should convene with and learn from international cities pioneering and inspiring solutions to urban challenges. In this course, we partnered with UDF on their Big Swings-Global Exchange fellowship, which seeks to build solidarity between leaders in New York and other cities taking “big swings” at their housing crises. The following report, compiling GSD student research carried through the Spring of 2025, was written in extension of the work developed by our course partner, the Urban Design Forum, whose Big Swings fellows published a report compiling their comparative findings in March 2025.

This nine-month fellowship, bringing together forty rising housing practitioners across design, development, policy, law advocacy and journalism, intends to complement the diligent work of local leaders, weave together diverse perspectives, and support a new generation of leaders to house every New Yorker. The goal is to build bridges between NYC and peer cities taking “big swings” at their housing crises. The goal of this project is to equip decision-makers to better advocate for reform, by weaving together diverse political perspectives, planning best practices and design strategies.

For the first iteration of this course, our students’ research aligned with the themes defined by the Urban Design Forum, looking specifically at global comparative solutions to deepen affordability, welcome new arrivals, build buy-in, cut red tape, and advance green solutions in NYC.

1. Deepening affordability: How are cities promoting affordability through mechanisms like rent regulation, community ownership, creative financing, and public-private partnership?

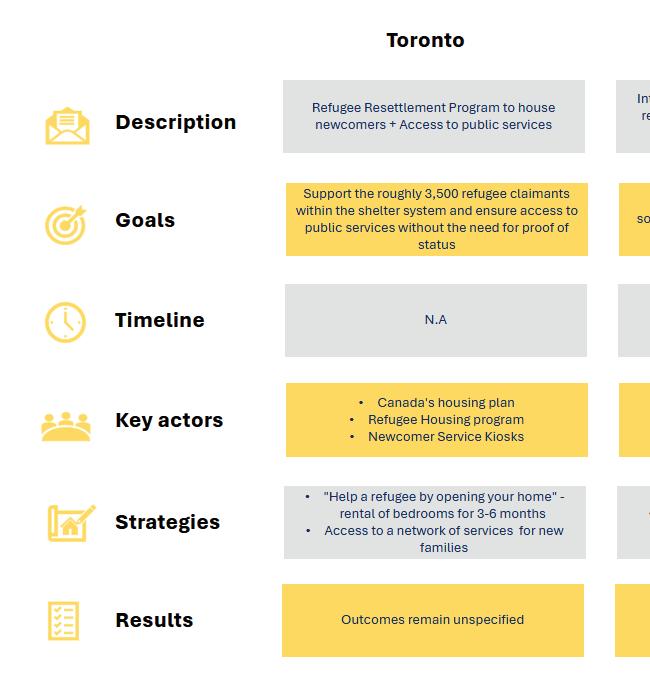

2. Welcoming new arrivals: How are cities housing newly arrived asylum seekers and supporting them to root within communities?

3. Advancing green solutions: How are cities creatively confronting the dual challenge of delivering housing while also limiting carbon emissions?

4. Cutting red tape: How are cities removing onerous regulations and streamlining zoning codes to build the kinds of housing most needed?

5. Building buy-In: How are cities engaging local communities to overcome the fear of neighborhood change to achieve successful infill development?

Granted, New York, the largest city in the United States, is in no way every city. But as it faces the growing challenges specific to hot housing markets, and as it experiments with housing strategies, it’s well suited to produce lessons for other cities that were left out of national conversations.

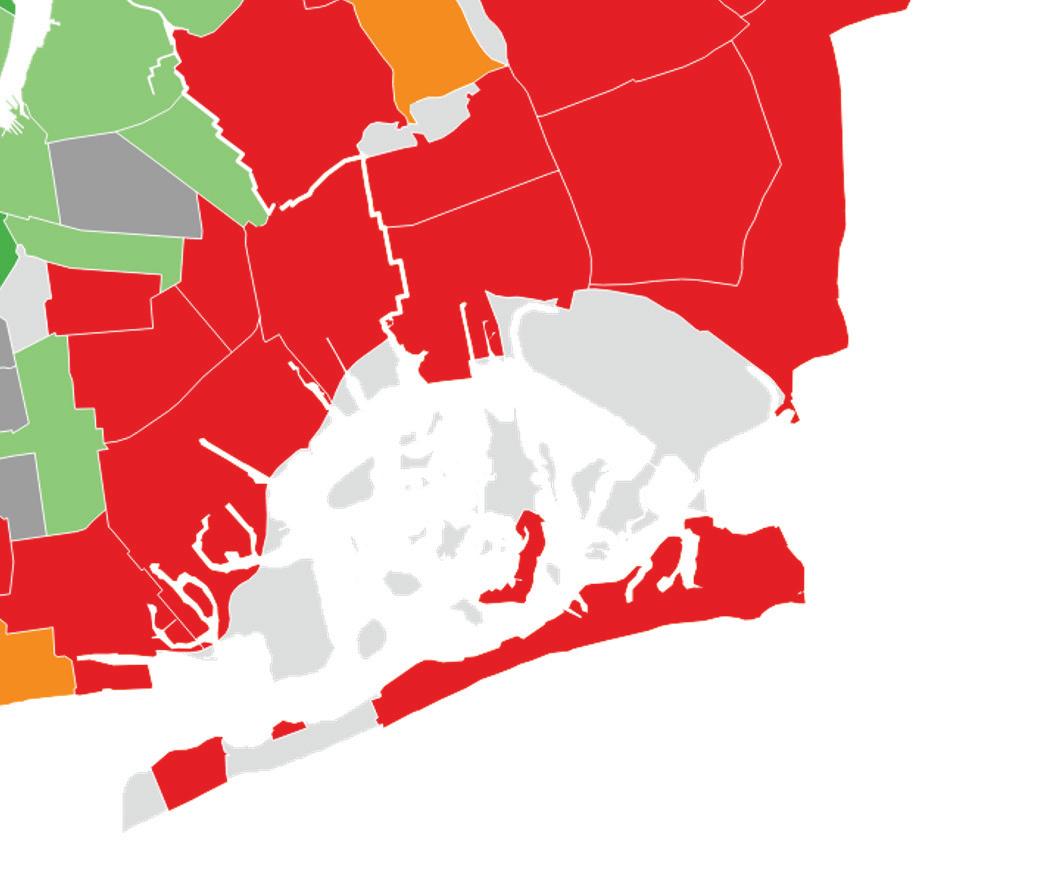

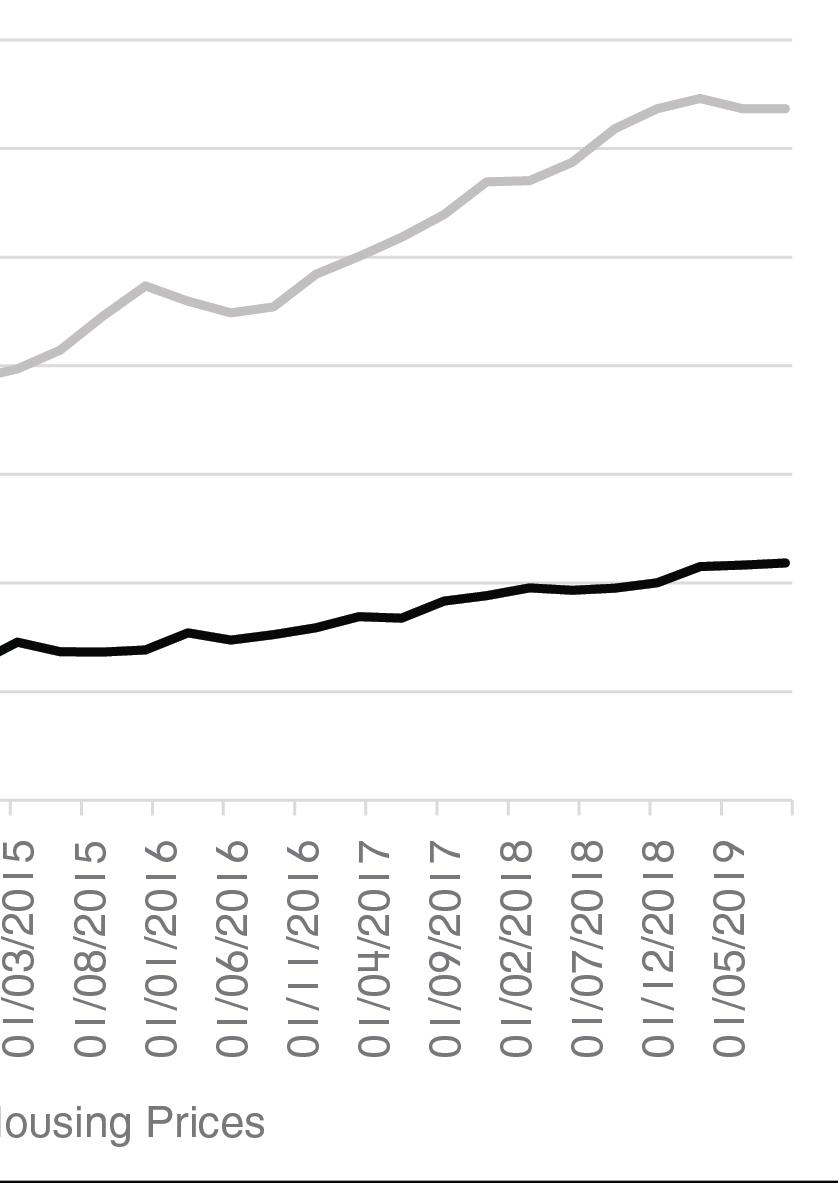

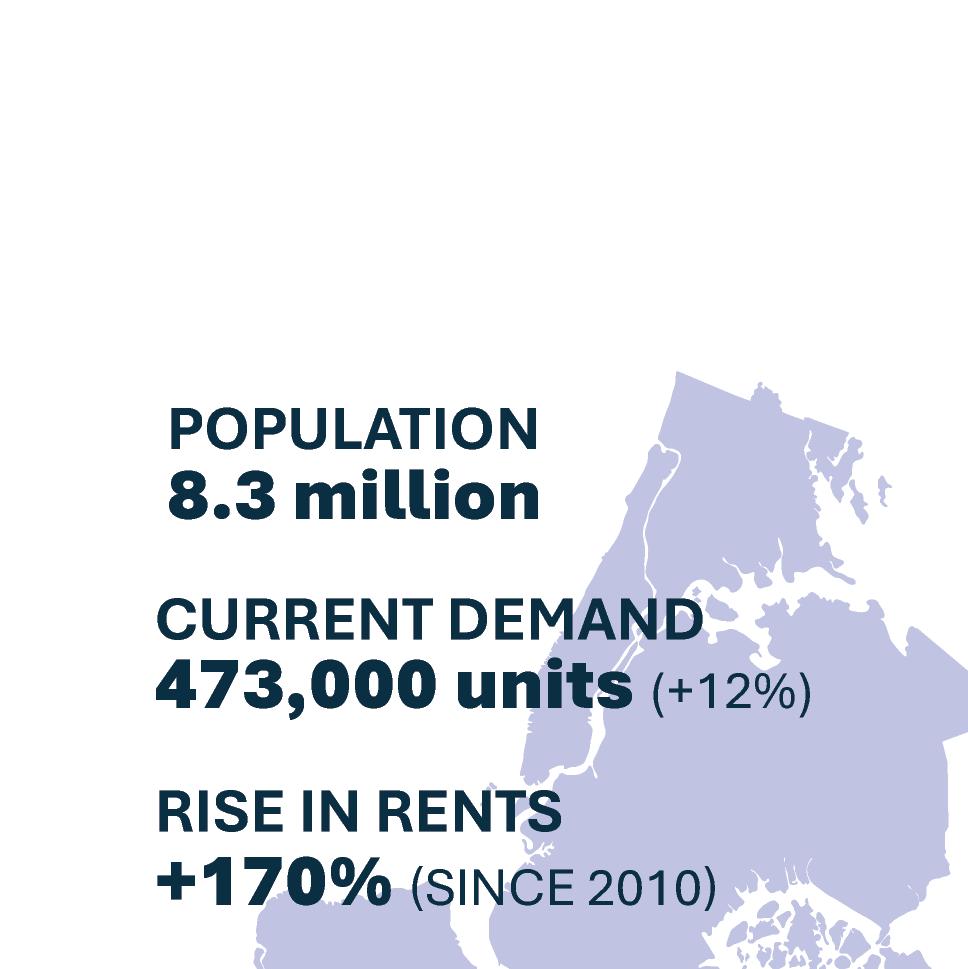

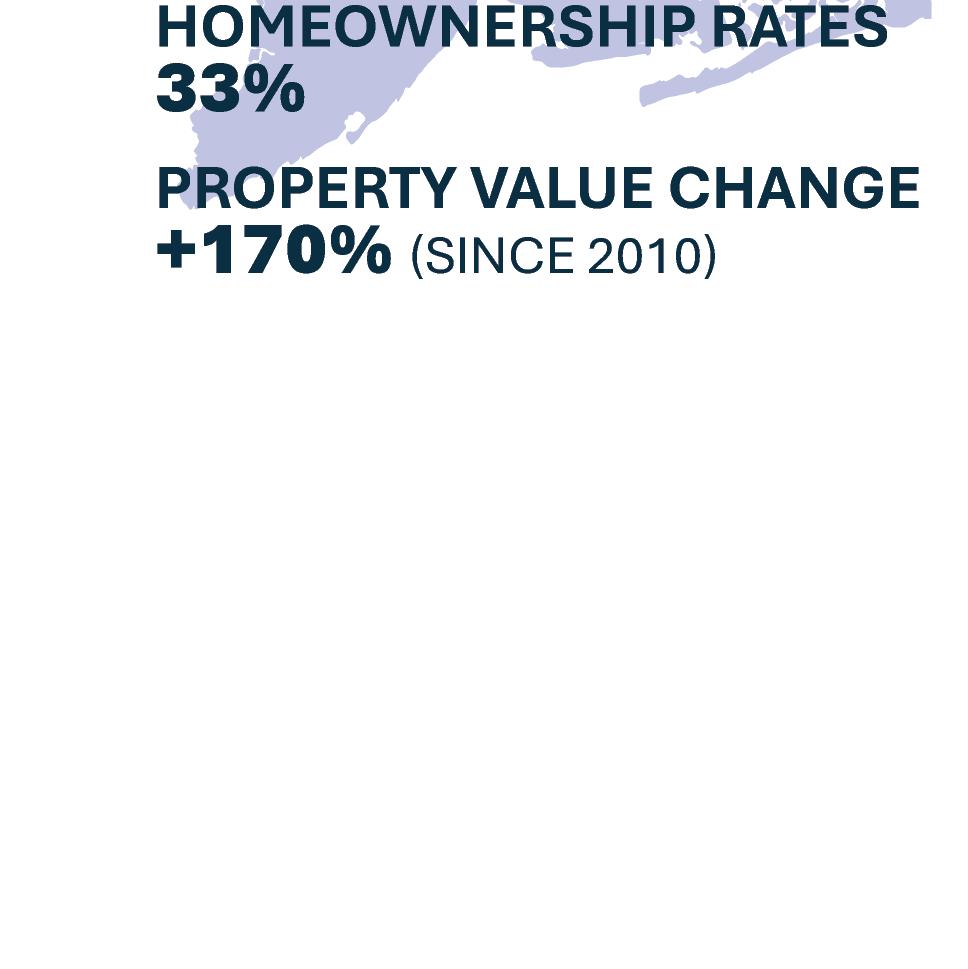

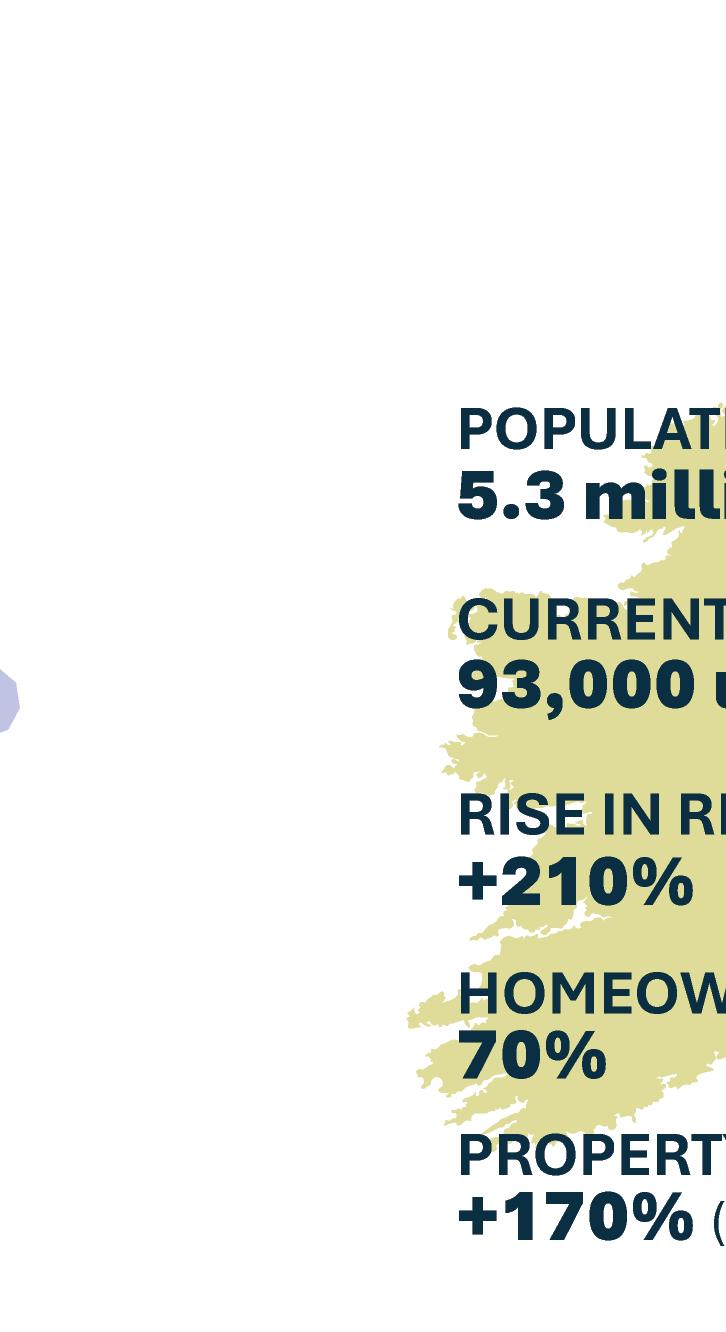

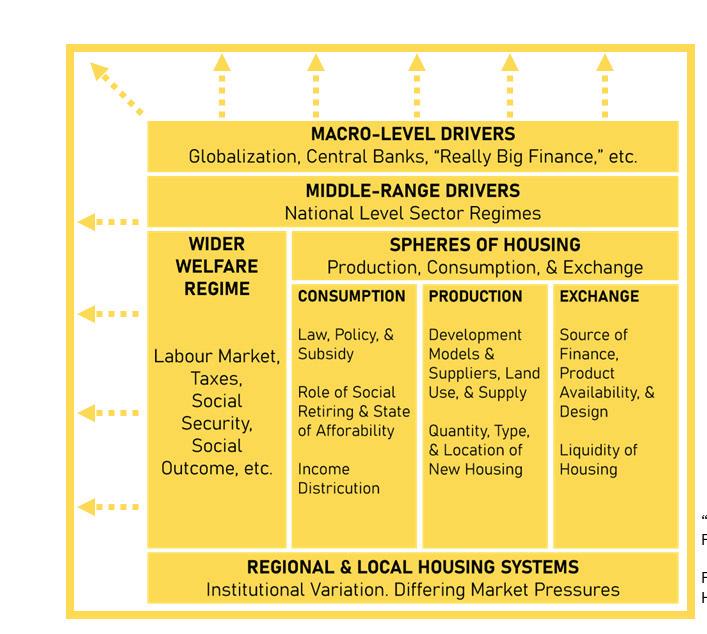

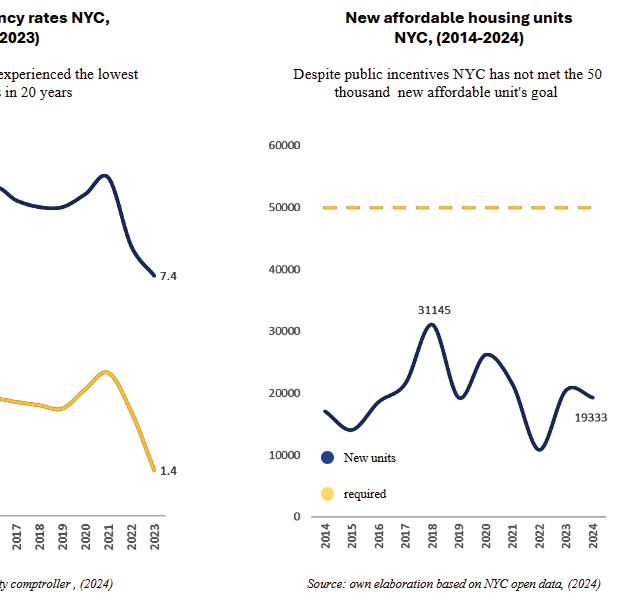

New York is the 14th most expensive city in the world. 546,000 residents left the city since 2020. The vacancy rate is lower than 1.5%, underscoring a very tight market with very limited supply. Over 50% New York households are rent burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Skyrocketing rents, a steep rise in tenant harassment and homelessness, and the fact that the city lags behind many smaller American cities in new construction, all underscore the severity of New York’s housing crisis (NYU Furman Center, nyc.gov 2025). The Covid-19 pandemic has also further underscored the growing socio economic polarization of the city, evidenced by the steep unequal health outcomes between neighborhoods in the Bronx

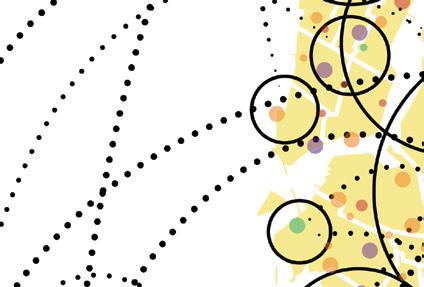

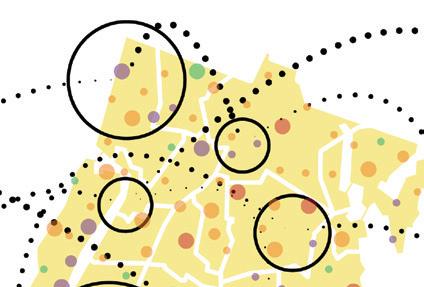

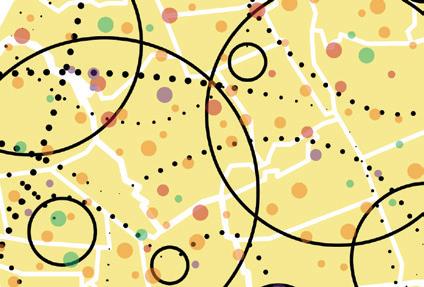

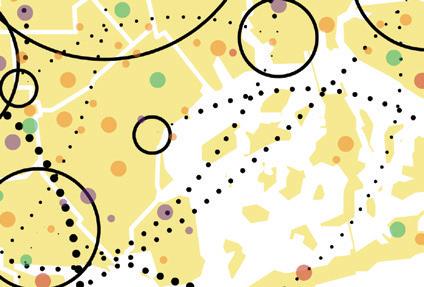

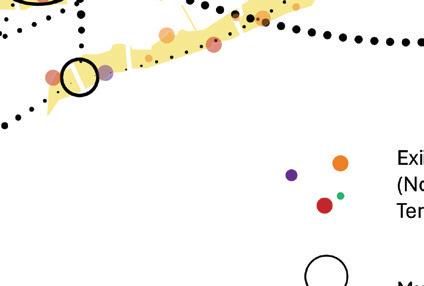

Chapter 4

BRISTOL Chapter 6

Chapters 1 & 3

Chapter 5

Chapter 3 USA Chapter 1

Chapter 5

Chapter 2

Chapter 5

Chapter 3

DENMARK

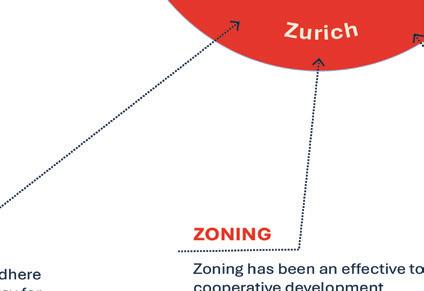

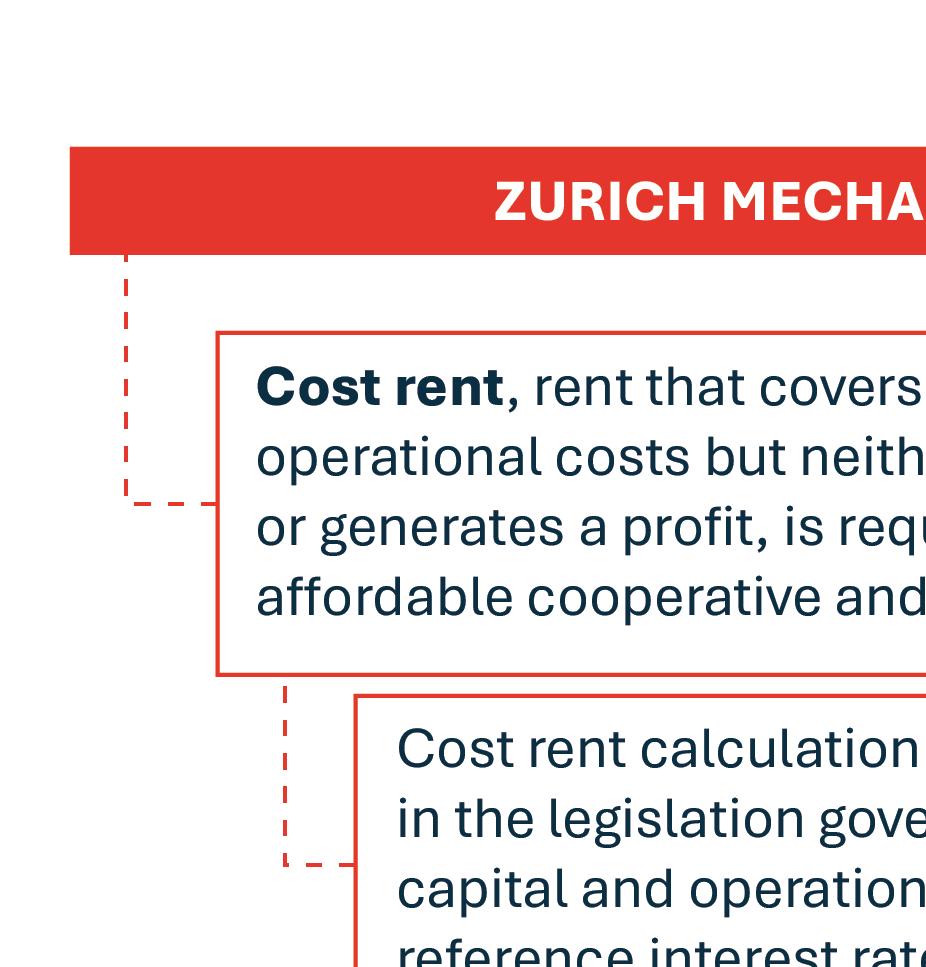

Chapter 2 ZURICH

WARSAW

Chapter 2

BANDUNG

Chapter 2

Chapter 2

and Queens that were some of the hardest hit in the country during the pandemic, and the rest of the city.

Stakeholders who make and break housing provision are numerous, from the macro region to local authorities, from the designers and developers to the brokers, from the willful house seekers to the actual residents who hope not to be moved from their neighborhood. In such a context of conflicting interests and competing forces, this report attempts to propose actionable strategies that consider the complexity of each housing context, in New York, and elsewhere.

Several seminal studies compare one competitive global city with the other, one tight housing market with the other. Foundational studies have laid the ground for contemporary comparative approaches to housing since the 1980s, offering frameworks to look at New York-LondonTokyo (Sassen 1991, 2001), London-New York (Fainstein 1994), Chicago-Paris (Wacquant 2006), New York-Paris (Albecker 2014), and so on. These frameworks are full of insights,

despite the many divergences in local political economies, modes of governance, financial mechanisms, scales of intervention or urban development cultures.

NYC has seen itself as a metropolitan region for over a century, and housing policy making is no exception to that configuration. Unlike the Grand Paris and Greater London Authority, NYC is run by several metropolitan governance agencies, and not a single organizing entity overseeing a defined administrative territory. The city of New York is made up of five boroughs (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, Bronx and Staten Island) and is administered by the Mayor of New York. The larger NYC metro region covers three states, which gave it its name of tri-state area: New York State, where NYC is located, as well as New Jersey and Connecticut. The metropolitan area therefore extends well beyond the borders of NYC and is built from a set of municipalities of these three states that no administrative entity unites. New York has historically been characterized by the omnipresence of “growth coalitions”, a system of alliances between local

government and the economic elites of a city in favor of economic growth (Logan and Molotch 1987). These coalitions have corresponded to a “progressive urban regime” (Fainstein, 2001). NYC is the perfect archetypical, rather than typical, illustrative case for this discussion, as a city that has long been the progressive arena of social movements that confronted the state. It is also the locality par excellence of spatial fixes deployed by powerful stakeholders, public and private, who are critical in shaping the real estate landscapes of the city (Mollenkopf 1988). Most importantly, when it comes to urban politics, it is the perfect platform for “patrimonial capitalism” (Piketty 2014), corporate, elected elite and middle-class new Reformers (Stone 1993, Stein 2017) concerned with tying such matters as historic preservation and affordable housing provision with securing their own private interests. In such a progressive regime, urban politics are about preserving coalitions, giving just the necessary space to citizen engagement, and extending decision-making power for nothing more than the periodic approval of planning processes. Former Mayor de Blasio’s two mandates, and current Mayor Eric Adams’ City of Yes proposal, might embody the most evident manifestation of new Reformers in how they plan and shape today’s cities. Perhaps what makes it the perfect case of lingering Progressive-era practices is how its implementation factors in top-down celebration and grassroots contestation, even more so underlining the limitations of its logic, and begging the question: “progress for whom, towards what?” (Stein 2017).

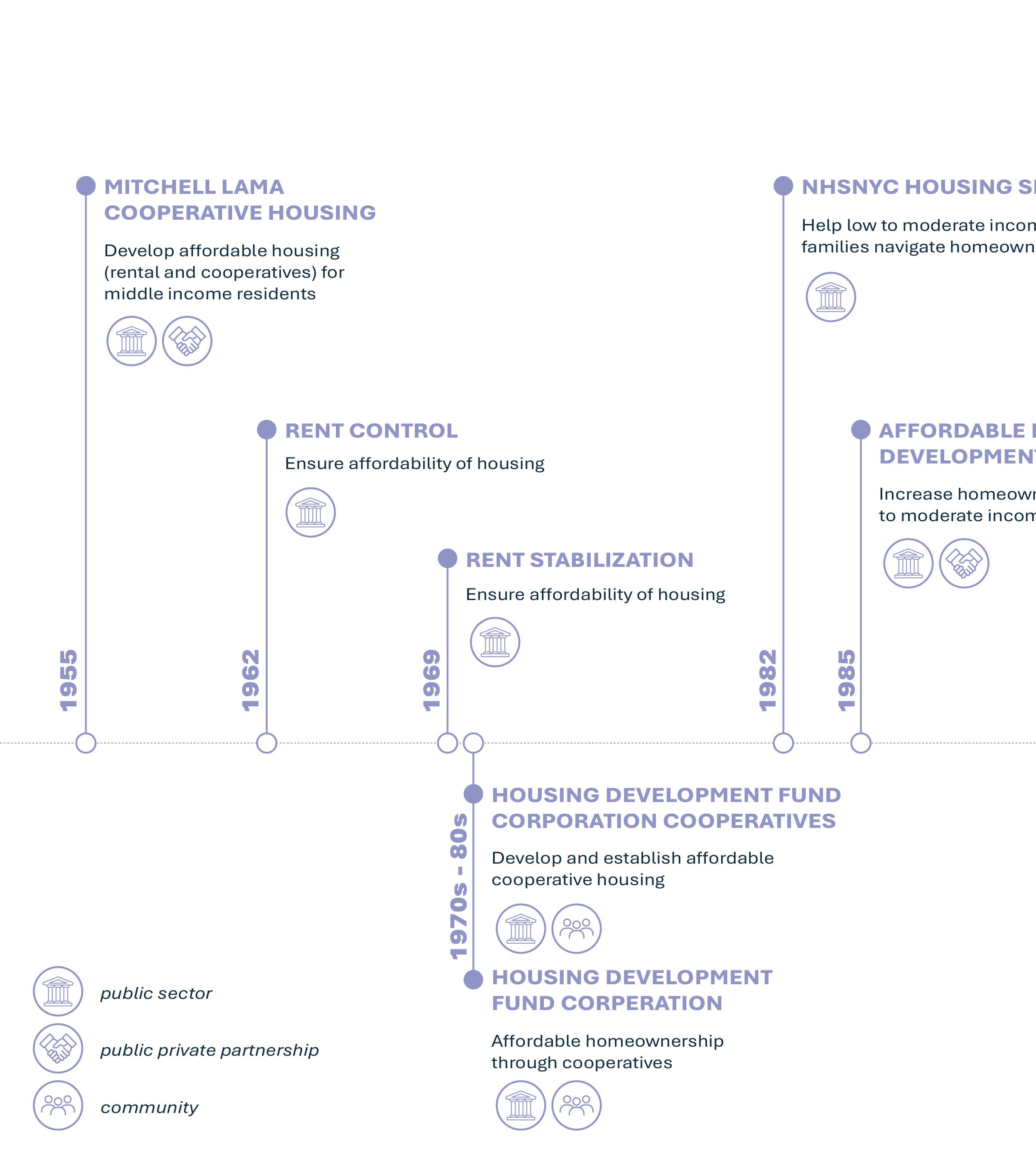

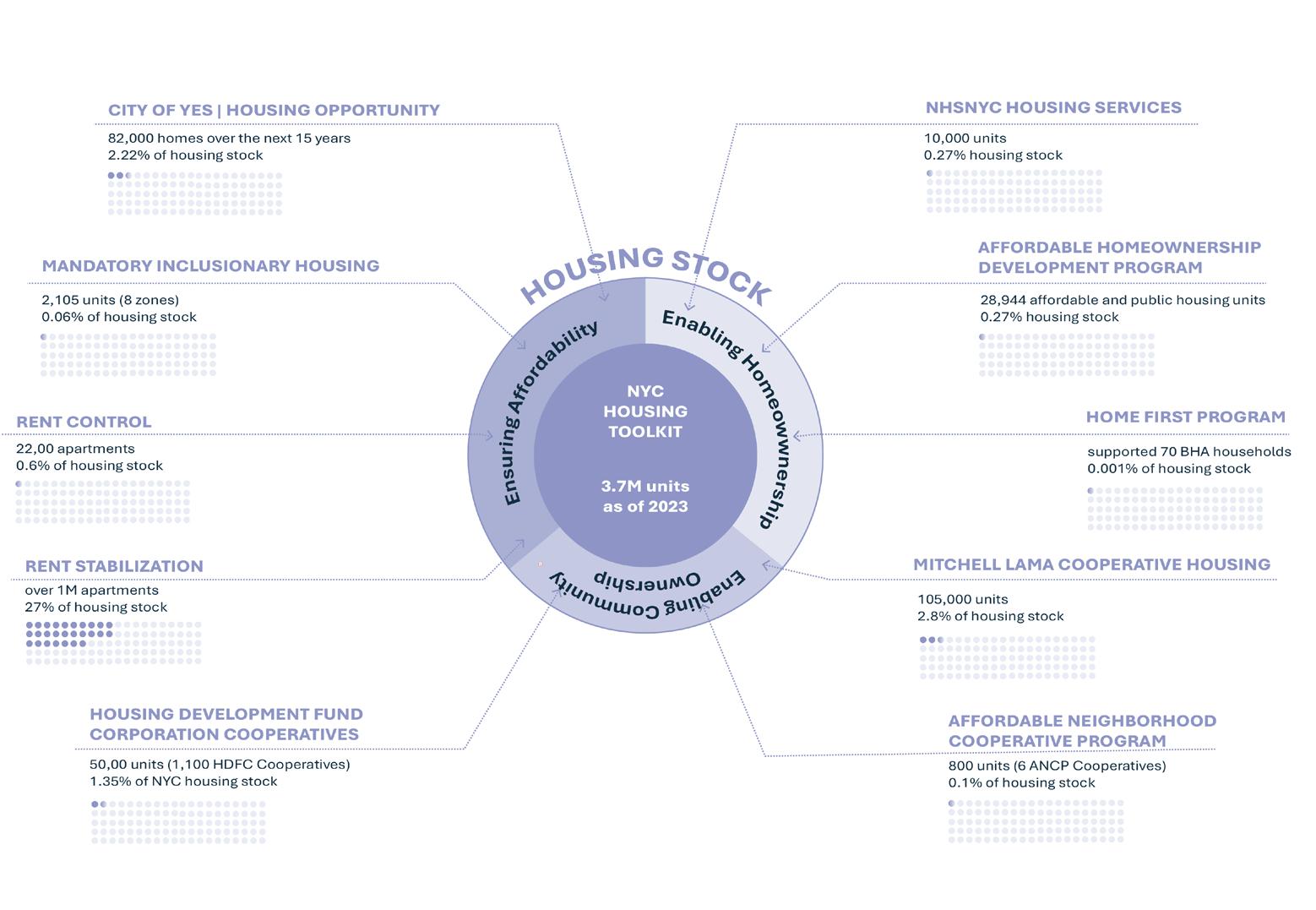

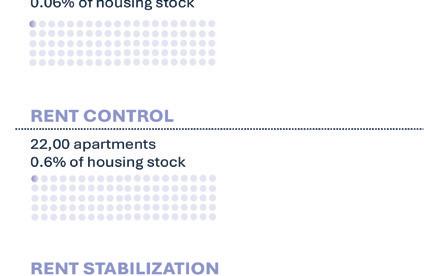

Looking at New York’s housing crisis requires a comprehensive assessment of the subsidized housing stock the city has tried to maintain over the past and current century. The four major historic social housing programs in New York are comprised of (1) the Mitchell-Lama programs launched by New York State in 1955 and predominant between 1960 and 1977, which provided middle-income housing to the city (between 80 and 130% of the median income), (2) HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development) federal funding or assistance programs, targeting households with incomes below 80% of the median income, over a period of 20 to 40 years - which have been dominant in the 1980s, meaning that a large portion saw their affordability expire recently, and (3) LIHTC (Low income housing credits), an indirect federal aid program targeting the most vulnerable lower income households (50 to 60% of median income), a program that has dominated the

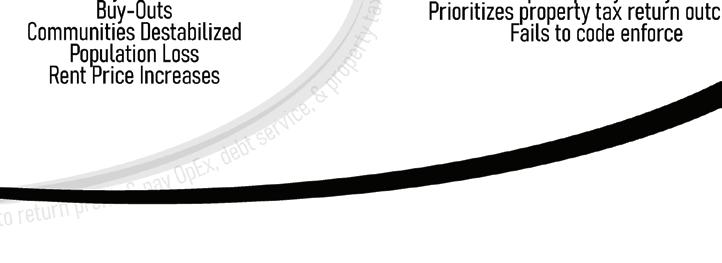

subsidized housing stock in New York since the 1990s. While these more standard subsidized housing programs position New York well in terms of providing housing options to its lower income residents, leaving public-private inclusionary zoning programs aside, the New York model has still been impacted negatively by the decrease of national social housing production since the 1980s. States and local authorities took over as the federal level retreated from housing policy making, leading to a drastic reduction in funding. Affordable housing construction therefore relied more and more on the private sector. It played a more important role in affordable housing construction, and the municipal public sector guaranteed this role through several breaks and incentives to private developers (Bloom and Lasner 2016). In recent years, new construction has been taking place in large part in “red-hot markets of gentrifying neighborhoods… both decried as the problem, because they displace existing tenants, and hailed as the solution, because of their appeal to real estate investors” (Slate 2015).

New York residential landscapes are often described today as being under permanent construction, but the city has come a long way. In parallel to “white flight” trends in the 1960s and 1970s, real estate investment had shifted away from the city center for decades, which resulted in a large stock of abandoned buildings, particularly in Harlem, downtown Brooklyn and the South Bronx. The loss of industrial jobs increased poverty rates in working-class minority neighborhoods, where growing trends of immigration were taking place. The urban crisis therefore led to the dual development of an inner city made up of bourgeois neighborhood “citadels” and ghettos (Marcuse 1997), and suburbs that were attracting growing flows of white middle-class households (Castells and Mollenkopf 1991, Albecker 2014). The rise of the mayor’s leadership role, often partnering with private sector agents, is also linked to the urban crisis of the 1970s and 1980s. Although private capital was a part of New York’s built environment throughout the twentieth century, it is also in this short-term crisis of urban policies that the role of private companies as a key agent of urban development was established. At the end of the 1970s, several interest groups coming from the fields of banking and insurance started playing a growing role in local urban development. Heads of large companies controlled many institutions that had access to municipal power, including City Club, the Real Estate Board of New York,

the Commerce and Industry Association, or the Regional Plan Association. These groups played a major role in reorienting New York’s management model towards privatization and tax breaks during fiscal crises (Fuchs 1992).

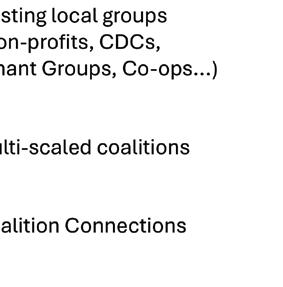

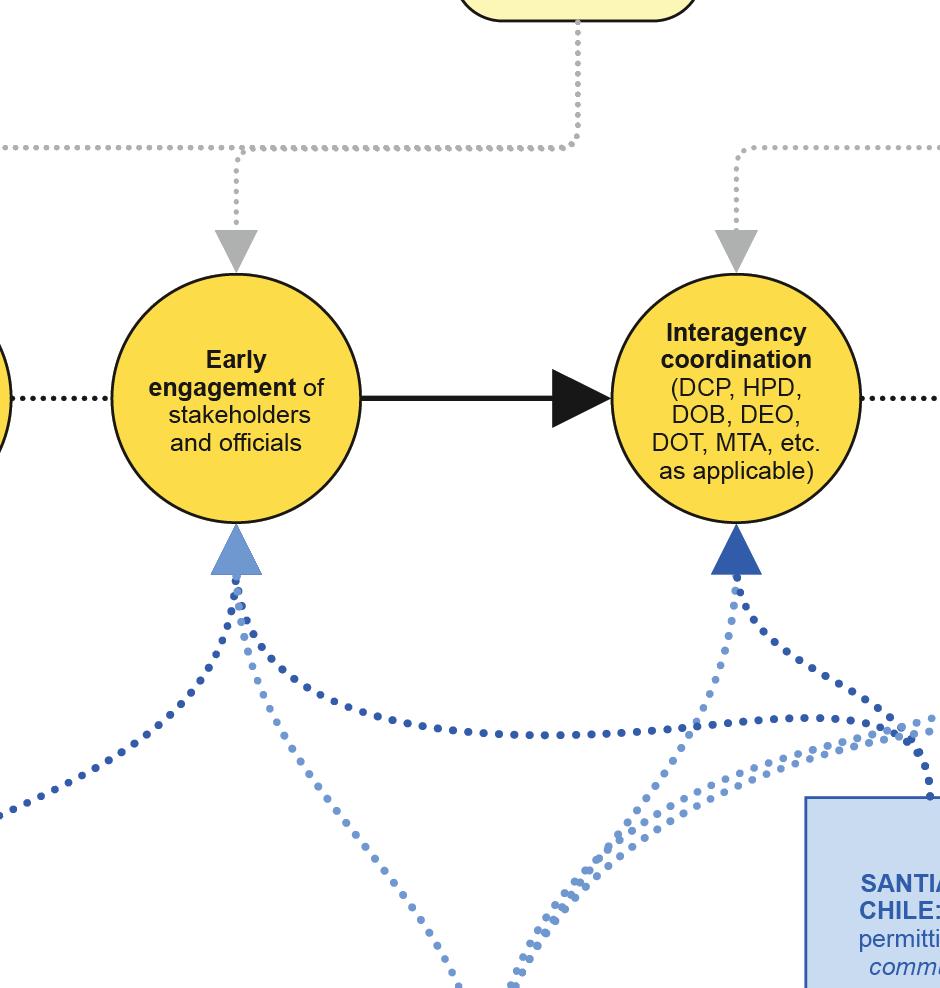

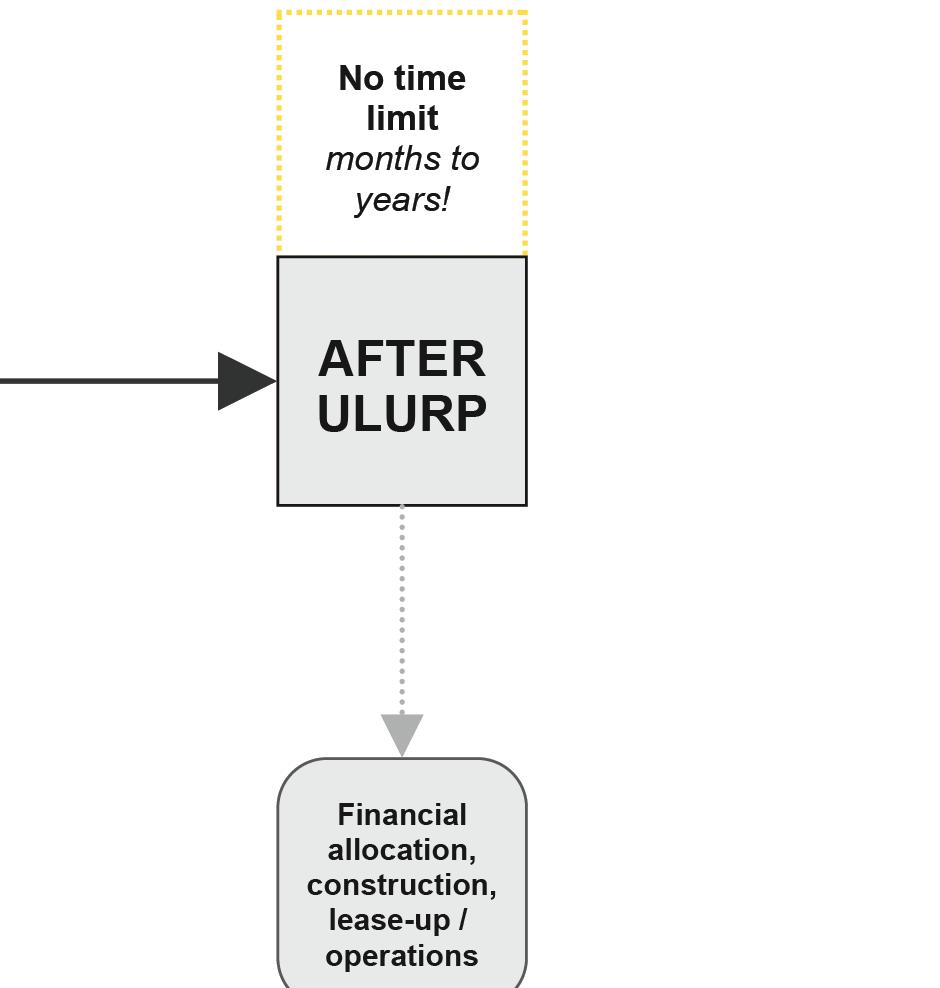

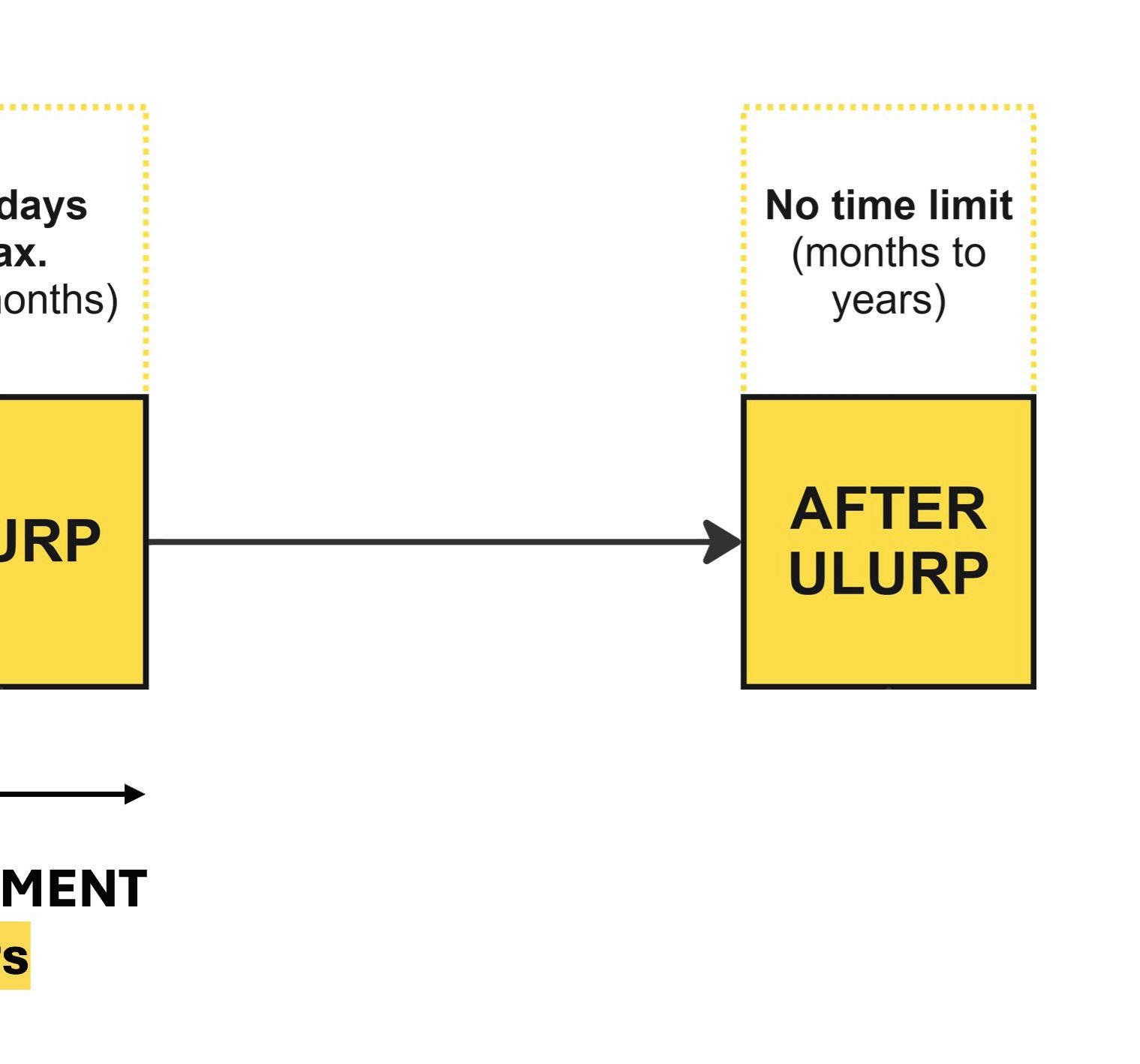

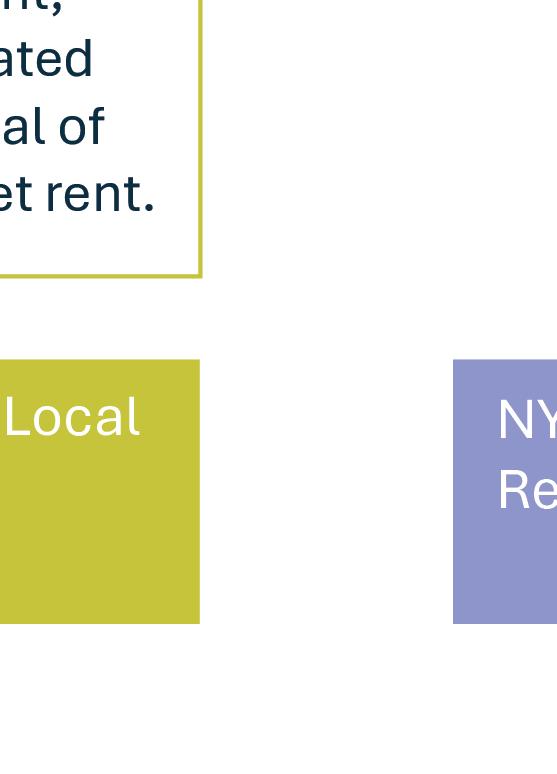

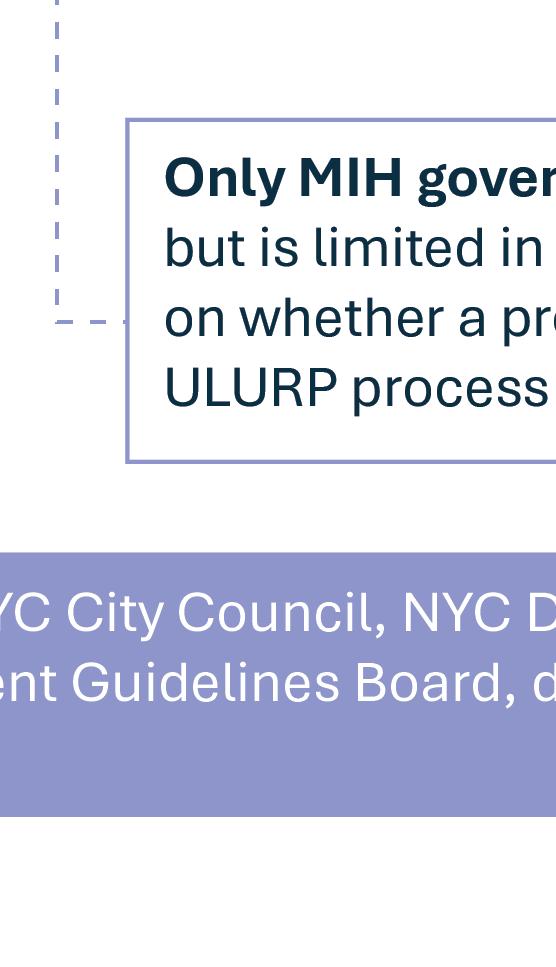

Most developments happen in New York “as of right.” This means that the proposed use for a project can proceed without a separate review if it matches a given site’s zoning. But if a developer wants to build residential condos on land that is zoned for instance for industrial use, or if the same developer wants to build denser buildings than what is locally authorized by the zoning code, then the zoning designation must be changed, which is where the municipal Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process comes in. ULURP could be defined, simply, as “a make-or-break vote” that takes place through a roughly seven- to nine-month long process (Curbed 2020). “These stages are also where the public gets involved, and where major drama can unfold; heated hearings, protests, and legal challenges are all par for the course” (Curbed 2020). Current proponents of reforms to the ULURP framework argue that there are always three separate sealed spaces in these rooms. The space of the session speakers who oversee addressing what is on the ULURP hearing agenda, through the most neutral of official programming. The space of community organizers, interrupting the session with their microphones and banners, which works more like an ephemeral one-minute way too vocal and quickly silenced intermission. Lastly the space of the residents - in other words the extras - but who do they represent after all, having the luxury to skip work in the middle of a Wednesday afternoon to come read a pre-typed letter voicing their concerns, distributed by one of their volunteer community representatives. The disconnect between these three groups of stakeholders is often strong, and this remains probably true for all steps of the ULURP process.

In the words of our course partner, the Urban Design Forum, over the course of this academic year, NYC, the United States, and the world have all undergone significant changes. To address the housing crisis, policymakers approved the “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity” --a major rezoning reform aimed at increasing housing availability across all neighborhoods. Students learned to dissect how broad exemptions built into the plan have diluted its overall impact. Meanwhile, at the national level, the arrival of a new administration has also introduced fresh

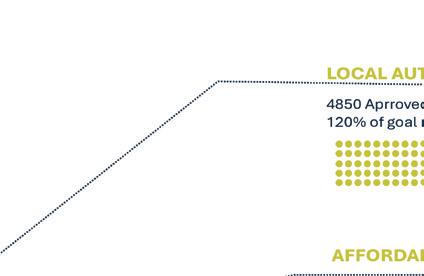

uncertainty regarding the direction of future housing policy. While current mayor Eric Adams has passed his signature housing plan called City of Yes last year, promising 82,000 new units within the next 15 years, the legacy of similarly ambitious plans passed by his predecessors forces New Yorkers to wait and see what this will exactly yield before declaring victory over the crisis. De Blasio, Adams’ predecessor, had promised 200,000 new units at the beginning of his first mandate. Recent evaluations of the MIH program’s impact on housing construction showed that the promises made by the de Blasio administration were far from being met. Furthermore, the implementation of the MIH program almost always in historically disinvested, low-income minority neighborhoods speaks to a larger issue of equity and distributive justice. Mayor Bloomberg’s mayoral mandate was also a turning point for these types of rezonings: during his time as mayor (2001-2013), more than 30% of the city’s area was rezoned, resulting in a total of 115 rezonings. These had several ambitions to rebrand certain areas of the city, for instance giving priority to waterfront redevelopment. New York still presents mitigated results in the targeted neighborhoods, and strong imbalances between social and market rate housing construction trends, even when production is on the rise. Rising housing costs are still one of the major reasons why households leave New York to go live elsewhere.

In a metropolitan area still faced with a lingering housing crisis, the short-term strategies of City of Yes is to continue tapping into a mix of existing tools and targeting select neighborhoods for rezonings, upzonings, and other similar strategies. Still, the question remains of whether this approach offers a strong enough long-term framework for neighborhoods facing crucial negotiations as to the type of urban development taking place on their premises. A report prepared by the Churches United for Fair Housing, titled Zoning and racialized displacement in NYC (CUFFH 2019) underscored that the fourth most segregated city in the United States ought to tie back its supply-side strategies to its long-time history of housing policy discrimination and redlining, given that more than fifty years after the Fair Housing Act (1968) was enacted as a landmark legislation of the Civil Rights Act, structural patterns of housing discrimination and segregation remain in NYC, in an even more acute way in lower-income neighborhoods.

Housing law experts underscore that there is

still a long way to go to reach the integration goals set by the 1968 Fair Housing Act and 2015 Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Act changes. The focus of the action must now be on “what remains elusive [, which] is the political economy— understanding what will persuade, encourage, and compel governments” (Johnson 2019, 1149), and “an understanding of the dynamics of change that might cause communities and government actors to adopt these strategies” (Johnson 2019, 1157). For Fair Housing law expert Olatunde Johnson, “(b)ehind the success or failure of regulatory and legal change in integration lies politics. Integration is thwarted by the politics of resistance, indifference, or adherence to status-preserving policies by middle and upper-middle classes.” (Johnson 2019, 1171).

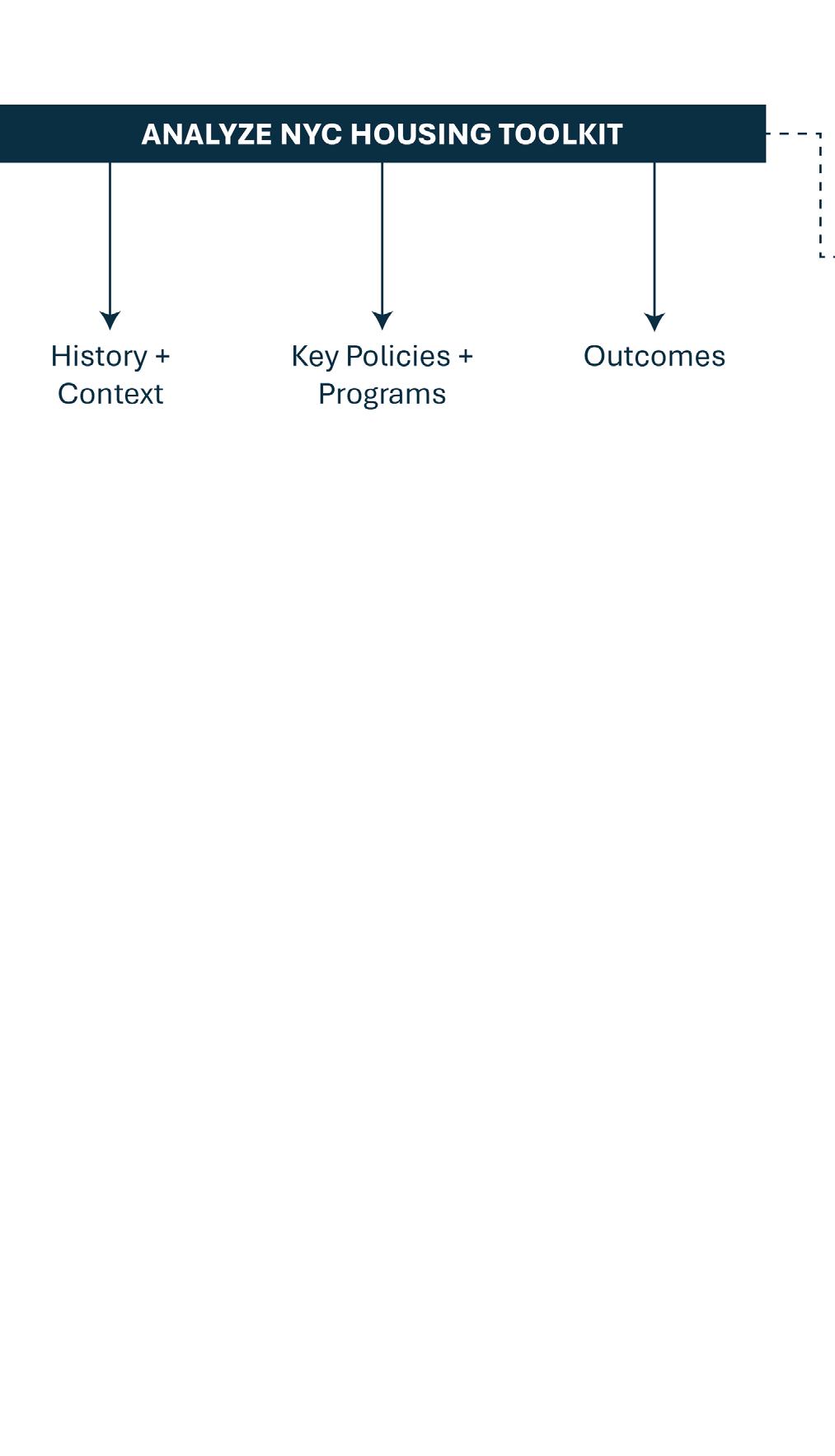

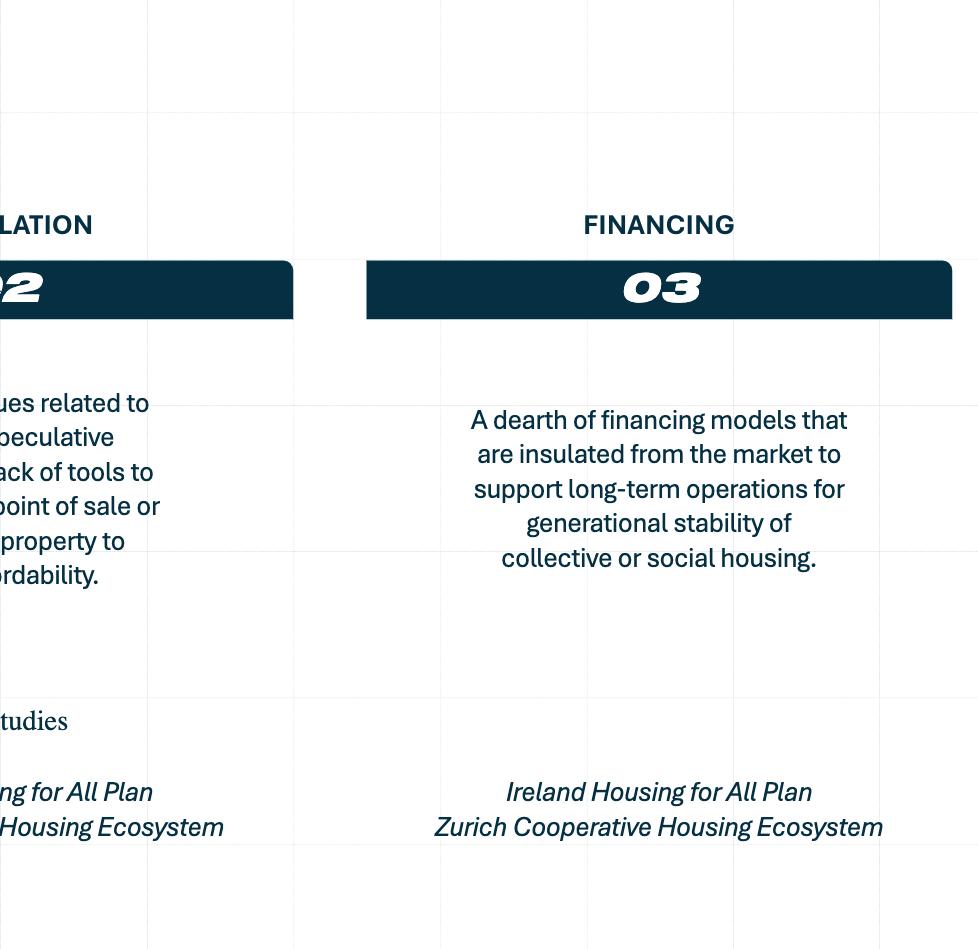

Because our class, At Home and Abroad: Housing in Comparative Perspective, has allowed us to develop a framework that goes beyond supply-side solutions, and considers the challenges of preserving affordability, strengthening multi-level comprehensive subsidies, and finding innovative ways to provide housing everywhere that impacts New Yorkers’ lives, health, educational and job opportunities, beyond simply housing, we chose to tackle the following five challenges: deepening affordability, welcoming new arrivals, advancing green housing solutions, cutting red tape, and confronting NIMBYism. In the following six comparative chapters, student groups triangulated background research on policy legislation, timelines, and financing mechanisms, using statistical data analysis, mapping, and interviews, in order to propose a fine-grain overview of what could be borrowed and translated from elsewhere to help New York answer its most pressing housing issues.

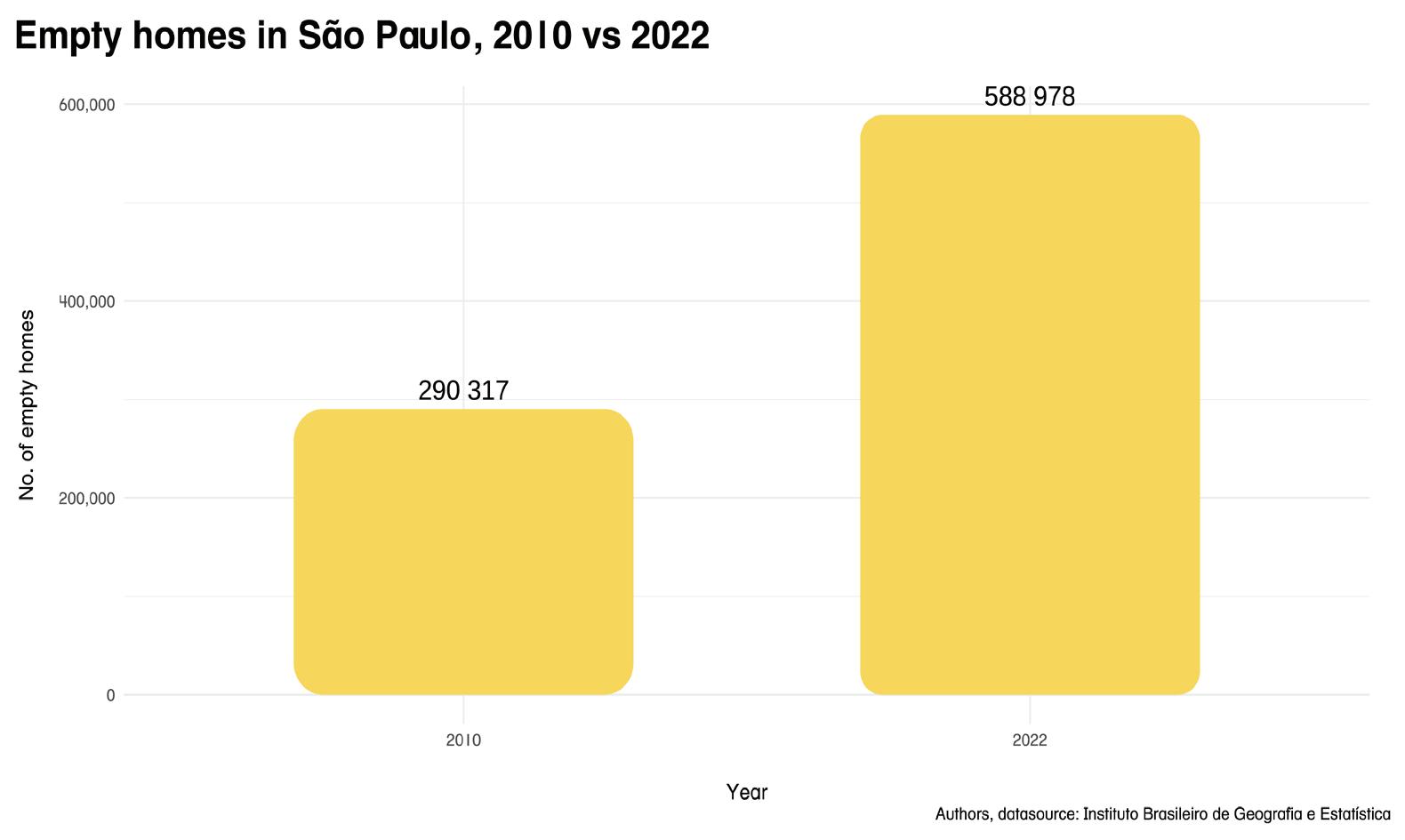

Our students also followed in the footsteps of UDF fellows as they concluded that no single strategy, policy, or program innovation could effectively solve all problems in each housing context, from Sao Paulo to Seoul, Poland to Canada, Bogotá to Zurich, or elsewhere. It became clear that bold initiatives don’t always succeed on the first attempt—some may falter initially but find success later, often in a different form or when combined with other complementary approaches.

In the end, looking at other peer cities taking a “big swing” at their housing crisis to inform what NYC should do going forward, requires treading lightly. Translation is more than the passage from one language to another, it is also

the passage from one culture to another (Eco, 2006), with the risk of facing untranslatable objects. Students took up that challenge this semester, and the following comparative case studies offer six insights into a more hopeful future for New Yorkers. Many questions remain unanswered and call for a committed decentered global comparative political economy.

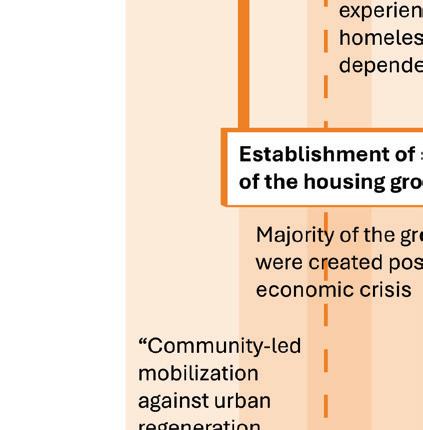

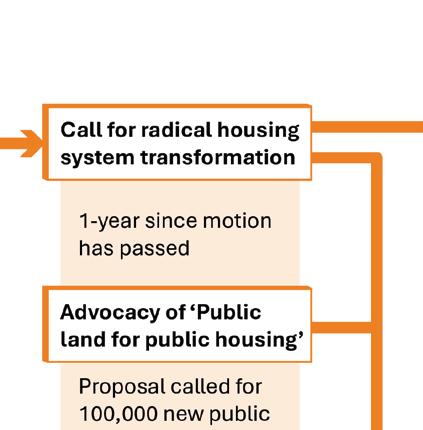

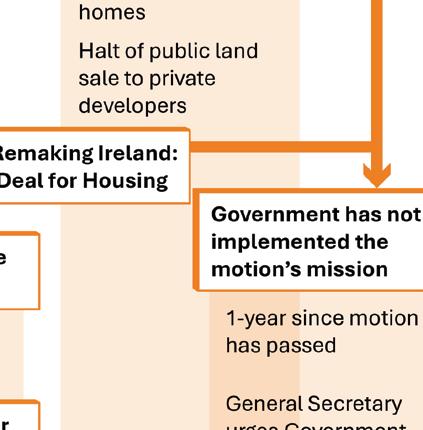

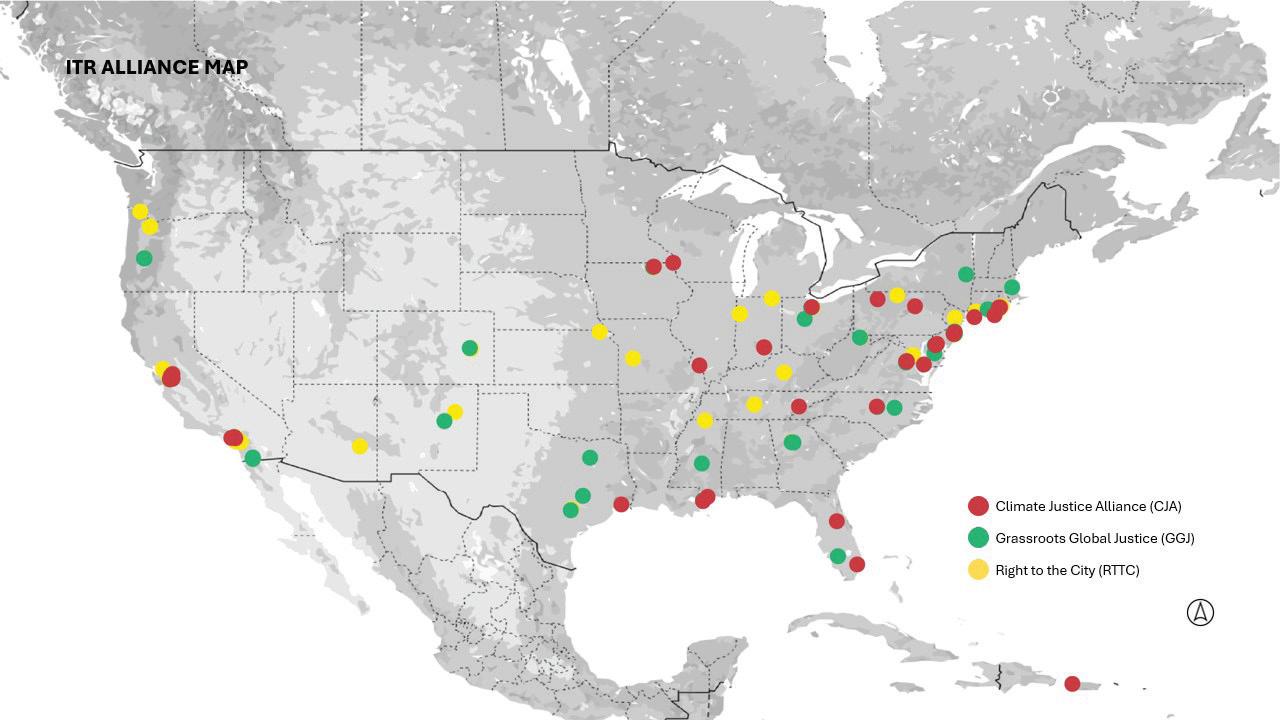

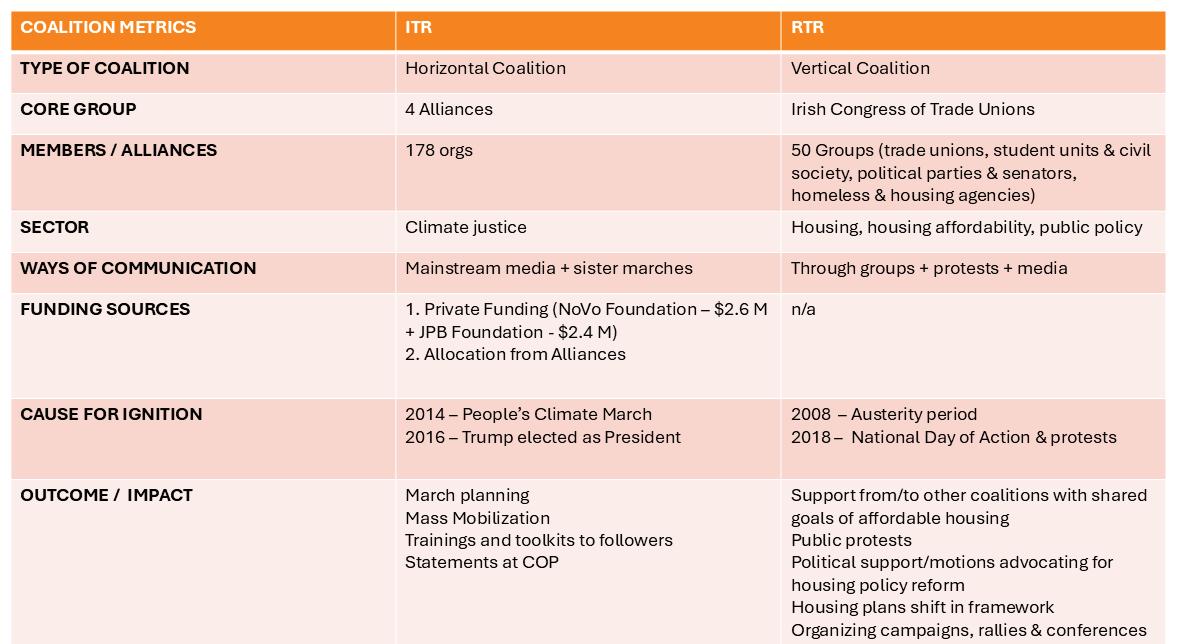

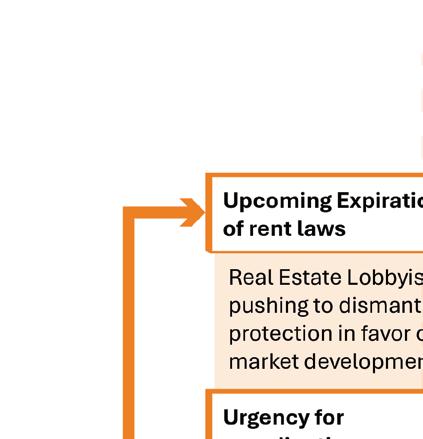

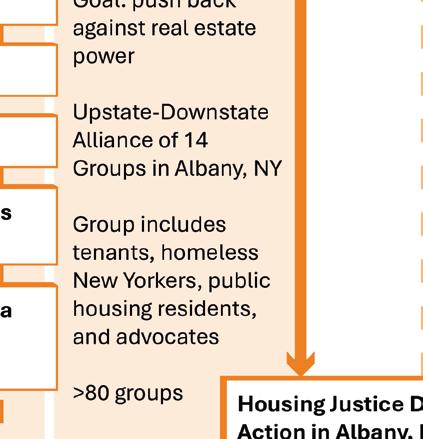

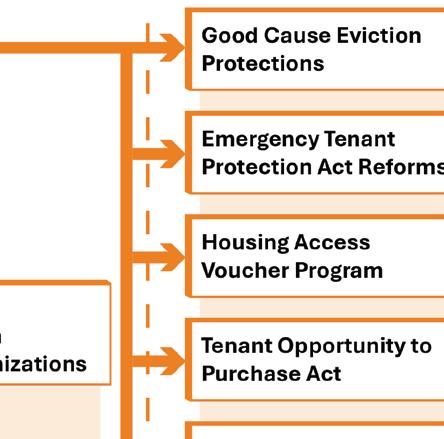

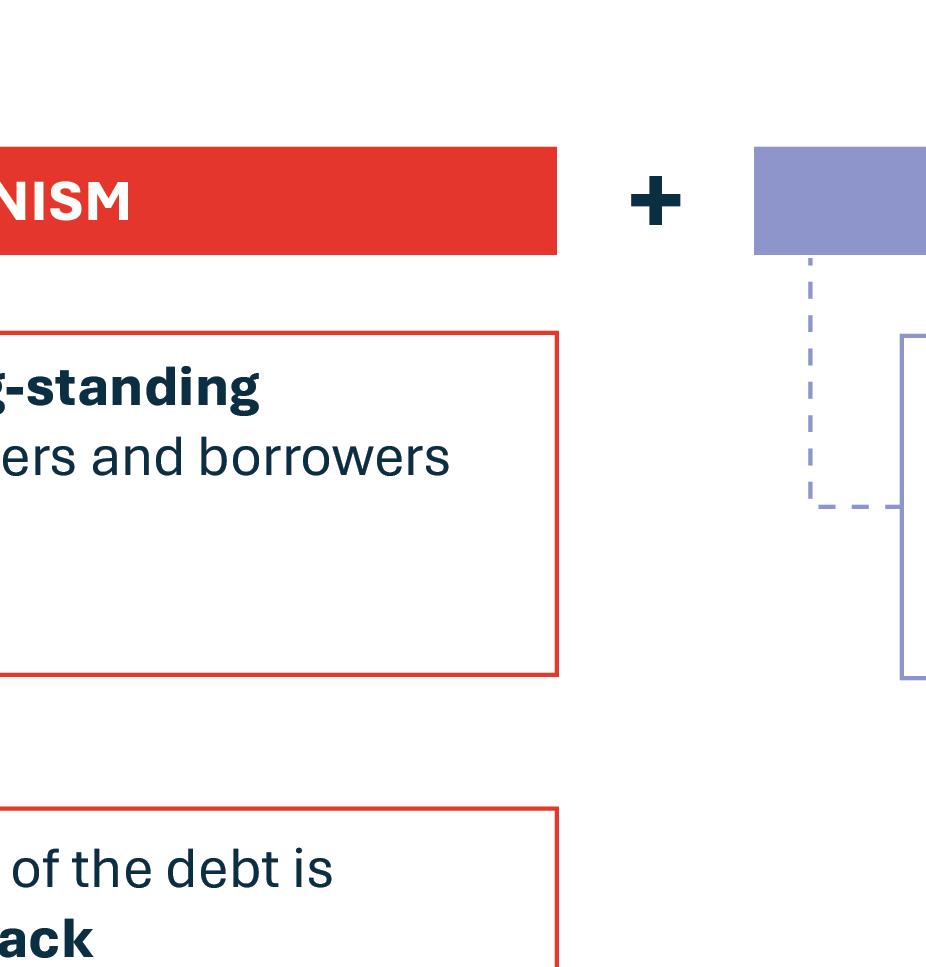

This memo explores how coalitions can serve as effective mechanisms for building public and political support for transformative housing policy. With NYC facing a critical housing shortage and intense affordability crises, coalitions — formal or informal alliances of stakeholders — are a potent tool for catalyzing system-wide reform. Drawing lessons from successful models in Dublin (Raise the Roof) and across the United States (It Takes Roots), and connecting them to local cases such as Yes to Housing and Housing Justice for All, the report unpacks how coalition structure, messaging, leadership, and strategy can coalesce into broader political power.

This analysis reveals that coalition-building is most effective when rooted in strong alliances, shared goals, and inclusive stakeholder representation. Theoretical and applied frameworks show that successful coalitions follow identifiable phases, from ignition and recruitment to institutionalization and long-term maintenance. The Raise the Roof coalition in Dublin demonstrates how a vertical coalition model can evolve from grassroots mobilization into national policy advocacy. Conversely, It Takes Roots shows the strength of horizontal, intersectional organizing across geographies, using mass mobilization and networked campaigns.

In NYC, coalitions like Housing Justice for All have already produced significant outcomes, including landmark tenant protection laws and rent control expansions. Yet the analysis of coalitions in the city reveals fragmentation and overlapping missions, often leading to saturation and weakened impact. Key local challenges include political inertia, community opposition to development, bureaucratic delays, funding constraints, and data access issues. Despite this, coalitions that employed multifaceted campaigns, digital and physical outreach, and cross-sector alliances were better positioned to achieve social change in the city.

The report’s comparative framework scores NYC coalitions on six indicators, highlighting both the achievements and limitations of current efforts.

To address limitations and amplify collective housing advocacy in NYC, the report recommends forming a “supercoalition” — a coordinated alliance of coalitions that transcends individual organizational missions while preserving their autonomy. This supergroup would unify efforts around shared goals such as tenant rights, anti-displacement, affordability, and sustainability, enhancing strategic alignment and resource-sharing. Such a coalition would not only streamline advocacy but also elevate community voices at every level of governance, from neighborhood to city-wide.

Specific actionable steps include connecting coalitions working in distinct geographic and strategic areas, supporting smaller, or emerging groups through established ones, maintaining relationship-building practices to reduce turnover and strengthen neutrality, and filtering broad member networks to align with the coalition’s focus. This model would enhance coordination, reduce redundancy, and increase the political capital necessary to pass ambitious housing reforms.

Further research should examine how leadership and governance would function within this supercoalition model, identifying the appropriate scale(s) (community, borough, or citywide) for its effective initiation. Integrating these strategies could transform NYC’s fragmented housing advocacy landscape into a unified force capable of driving long-term systemic change.

Building buy-in is a critical element in successfully addressing housing challenges, whether they are related to affordability, sustainability, displacement, or urban planning (Urban Design Forum 2025). It involves the acceptance of and willingness to actively support and participate in a proposed policy or plan. In the context of housing, this means residents, community organizations, policymakers, and developers all engaging meaningfully with housing initiatives to ensure that changes are both effective and inclusive.

Mass participation is a foundational pillar of buy-in. In housing projects, especially those involving large-scale development or redevelopment, mass participation ensures that a wide spectrum of voices is heard. When more people are involved, from tenants and homeowners to local business owners and civic leaders, there is greater legitimacy to the decisions made. Their input provides grounded insights into the lived realities of housing needs, improving both the design and implementation of housing solutions. Participation builds a sense of ownership over a program or strategy; when people are part of the process, they are more likely to support associated outcomes.

Public mindset plays an equally vital role. Housing policy often runs into resistance when public perceptions are misaligned with policy goals. For example, attempts to increase density through the construction of affordable housing units can face pushbacks from residents fearing a change in their neighborhood’s character. Shifting public mindset, through education, transparency, and demonstrating tangible benefits helps align public sentiment with long-term housing goals. This in turn creates momentum for transformative housing policies.

Finally, real representation ensures that housing policies respond to real (not assumed) problems. True buy-in requires policies to visibly address issues like housing insecurity, homelessness,

gentrification, and affordability. Representation also means recognizing and including historically marginalized communities who are often most affected by housing instability. By genuinely reflecting their needs and aspirations, housing policies become more equitable. There are several compelling reasons to take buy-in seriously. Maybe you want to shift the public mindset. Maybe you want to increase information-sharing, encourage community engagement, or restructure plans and policies. And the ways you could do this, or what we call build-ins, are numerous. These methods include pilot programs (public and private), Memorandum of Understandings (MOUs), shared statements, snowballing events, or our focus, coalitions.

Coalitions are powerful because they bring together diverse stakeholders who may not always agree but still share a vested interest in a common goal (Blount et al. 2023). They create spaces for dialogue, negotiation, and trust-building. In pooling resources, knowledge, and legitimacy, coalitions can amplify community voices and influence policy at scale. In housing, for example, coalitions might include tenants’ associations, municipal departments, developers, non-profits, and researchers working together to tackle affordability or combat displacement. Through these shared efforts, buy-in is not just built. It is reinforced and made resilient over time.

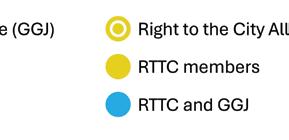

To understand coalitions and their roles for building buy-in, we ventured into two scales: citywide in Dublin, Ireland, and nationwide in the United States.

Dublin is a compelling citywide example because it faced acute housing crises marked by rising rents, evictions, and homelessness while also seeing a surge in grassroots activism. In response, coalitions have emerged, bringing together trade unions, political parties, student groups, and housing advocates. These alliances show how diverse actors can unify around a shared message to influence national debate and demand policy change from the ground up.

In contrast, the United States provides a valuable national lens, which unites over 200 organizations across racial, environmental, and housing justice movements. It demonstrates how buy-in can be cultivated across vast geographies and issues, particularly in a politically fragmented environment. The U.S. case highlights how national coalitions sustain momentum over time through coordinated campaigns, shared principles, and intersectional advocacy.

The response from UDF for building buy-ins was constructed through three case studies that looked at coalition-building in Oregon, structural change and policy feedback loops in New Zealand, and landmark cases in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. Their big swing idea is to build a cross-issue coalition that represents issues and needs in housing, transit, public space and climate. This required transforming decision-making and governance structures, shifting responsibilities of community boards in NYC, ending norms of member deference, and leveraging courts to advocate for the right to affordable housing.

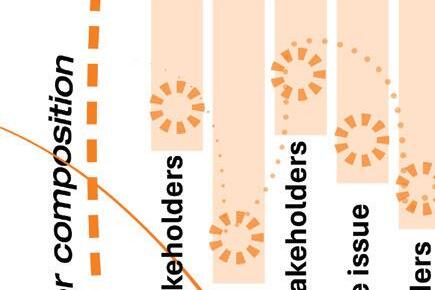

For this to be implemented, we recognize that an understanding of coalition-building as a method for building buy-in was necessary. The aim is to examine the strategies employed in successful housing campaigns, focusing on coalition building and messaging. It will identify the specific messaging techniques that resonated with target audiences and assess how these were tailored to different stakeholder groups. The analysis will also explore the composition of coalitions, detail-

ing how actors collaborated and how their roles complemented one another. Finally, it will evaluate these coalitions based on campaign success, as defined by its ability to garner policy changes, housing outcomes, public engagement levels, and shifts in public opinion or political will. hat may not want to actively participate to main

“Coalitions are powerful because they bring together diverse stakeholders who may not always agree but still share a vested interest in a common goal. They create spaces for dialogue, negotiation, & trust-building.”

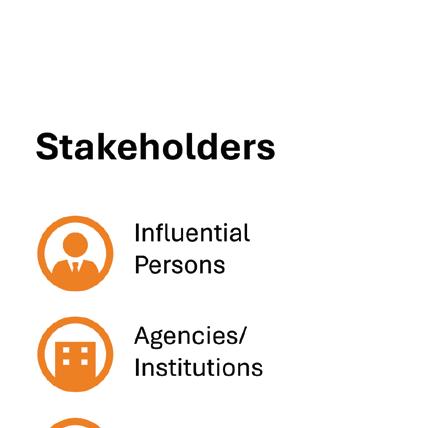

We offer two different analytical models to better understand the mechanics of coalitions: theoretical framework and timeline in addition to stakeholder mapping.

As we were conducting research for a general theoretical framework, we found a gap in the high-level analysis of housing coalition building processes. Moving forward, we began to find and piece together a wider literature that assesses coalitions from different planning sectors. The idea was to build a foundational interdisciplinary theoretical base to describe and analyze coalitions before proposing actionable items for NYC.

We devised a model that identifies stakeholder involvement and relationship building as key components of effective coalition building. To execute this, we conducted stakeholder mapping for the nation-wide ITR coalition. This cross-alliance group provided a valuable opportunity to analyze a broader and more complex coalition, particularly in contrast to the more localized RTR initiative. The ITR coalition’s roots lie in powerful mass mobilizations from across the country, which brought together diverse actors around a shared vision. Stakeholder mapping enabled us to better understand how large-scale coalitions function, sustain momentum, and coordinate efforts across geographic boundaries.

Acting as a clearinghouse

Acting as service coordinator

Acting as change agent

Grassroots Coalitions

Professional Coalitions

Community Coalitions

We began our study by exploring how coalitions are formed, as well as the core relationships that support their formation. Then we focused our research on understanding what models, types, and evaluation models can begin to frame coalitions. Our focus was later narrowed in defining what we call coalition stages typified by who gets involved and when do they become involved, the milestones that occur during each phase, and the relationship between actions and events that lead to certain outcomes. The RTR case acted as our precedent to apply our theoretical framework and timeline, by extrap-

olating information and assessing the sequence of events that occurred ahead of the coalition’s formation up until its current outcomes. We continued building our theoretical understanding by exploring the metrics of success for building effective coalitions.

As mentioned earlier, a coalition is a group of diverse stakeholders — both from private and public sectors — who are collaborating with a certain set of strategies to achieve a common goal.

Literature discussing coalitions has proven to us

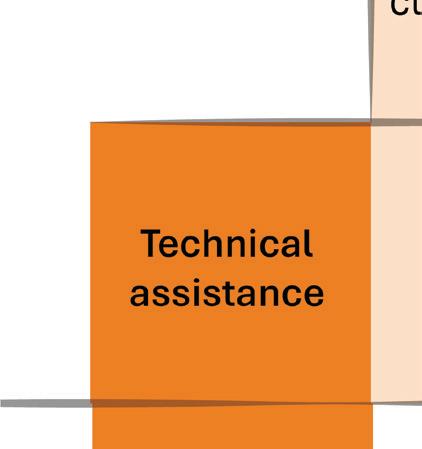

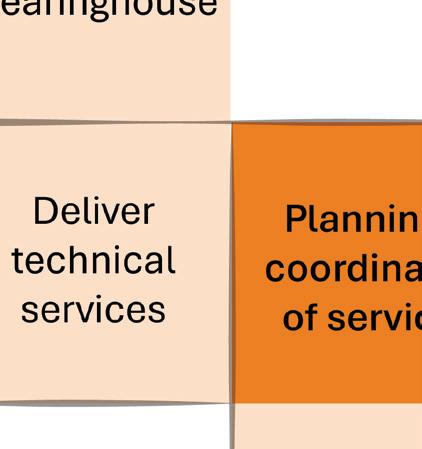

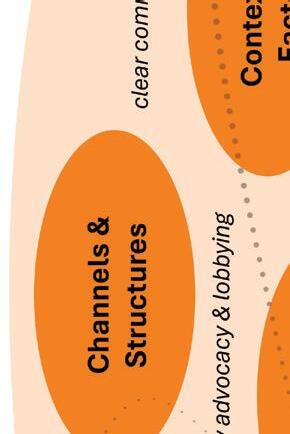

the complexity and multifaceted perspectives of understanding coalitions at a theoretical level. Kochhar (2013) bridges together different disciplines, and identifies coalition models, types, and evaluation models that can be considered when better understanding coalition effectiveness, synthesized in the figure above and broken down below:

1. Information and resourcing sharing—Act as a clearinghouse

2. Technical Assistance—Deliver technical services

3. Self-regulating—Set Standards

4. Planning and coordination of services—Act as service coordinator

5. Advocacy—Act as change agent

1. Grassroots Coalition

2. Professional Coalition

3. Community Coalition

1. Targeting Outcomes of Programs Model— focus on planning, implementing and evaluating programs

2. Community Toolbox Evaluation Model— provide a logical framework for assessing change across the different coalition stages

In determining a coalition’s effectiveness, we identified channels, structures, coordination, control, contextual factors, course of action, and collaboration (Kabateck Strategies 2023). Figure 3 outlines these notions acting as a general guide for those who are working within coalitions and those assessing coalitions.

The primary element that proves to be key in any type of coalition is alliance building. Managing alliances is an integral part at every stage in the coalition from its first stages of acquiring members to pushing for long-term social change—allowing to maintain a balance between organizational and public interests (Kochhar 2013).

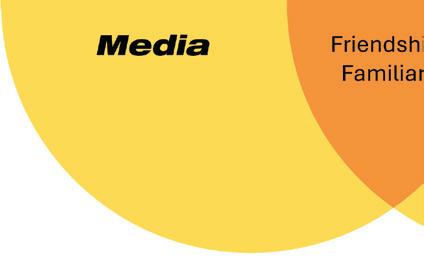

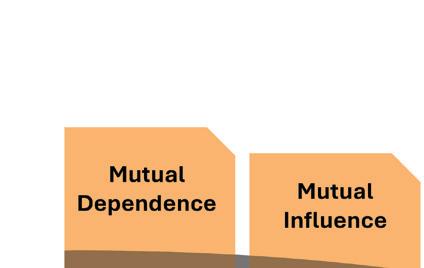

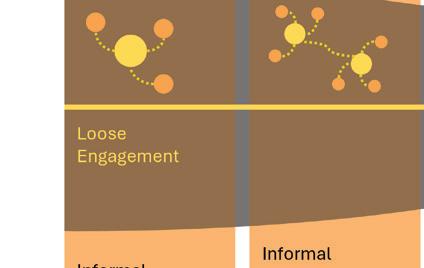

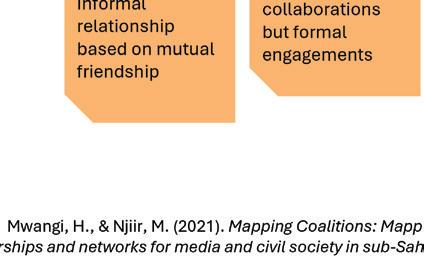

The model shown in figure 4 highlights the complex multilayered relationship between the media and civil society. Media plays an essential role in the way coalitions communicate, both with internal stakeholders but also with community and external stakeholders. Building coalitions requires a level of commitment from all parties, “from loose and task-based engagement to structured and formal engagement and collaboration” (Mwangi and Njiir 2021).

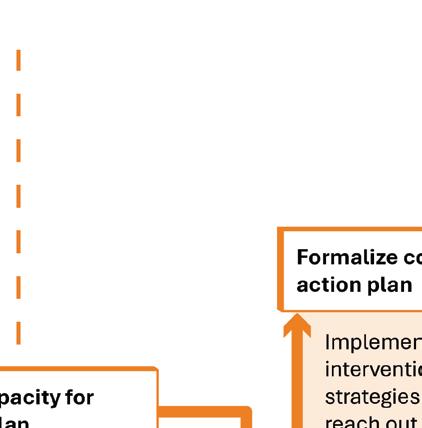

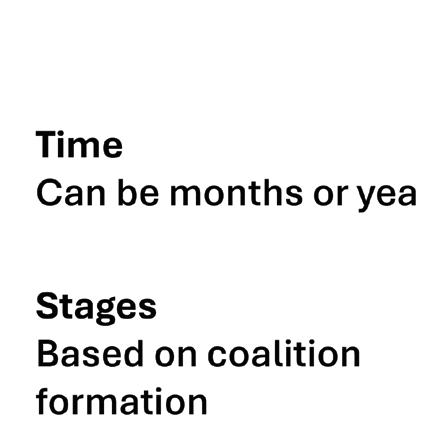

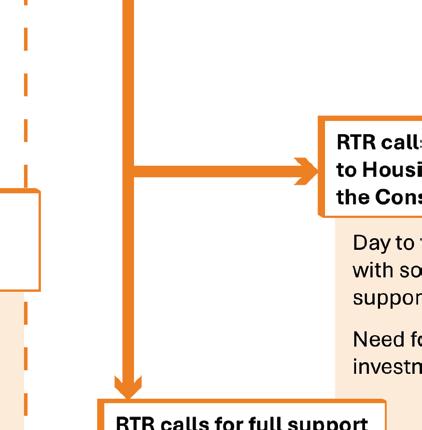

As we continued exploring the conceptual foundations of coalitions, we wanted to investigate actions that are integral to the process of building up a coalition. We decided to translate our research into a granular timeline representing coalition building.

As we continued exploring the conceptual foundations of coalitions, we wanted to investigate actions that are integral to the process of building up a coalition. We decided to translate our research into a granular timeline representing coalition building.

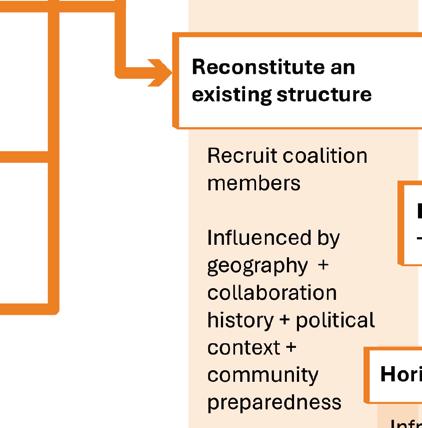

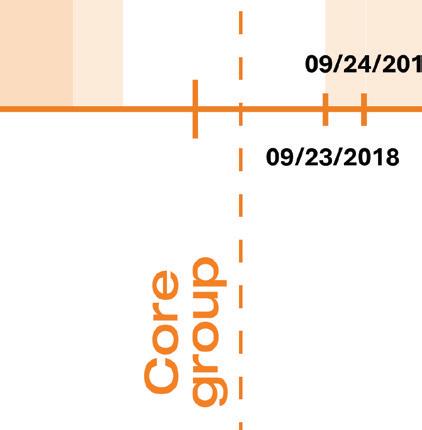

We identified five stages overall:

1. The ignition phase brings in stakeholders in society to either: 1) address urgent social situations, 2) empower communities by giving them control to address societal change, 3) convene stakeholders who are focusing on

achieving comprehensive intervention, 4) pool resources and services for more effective implementation, or 5) initiate political and social change through mobilization and relationship building (Kegler, Rigler, and Honeycutt 2010). Either of these notions, individually or collectively, can lead to the next stage in coalition building.

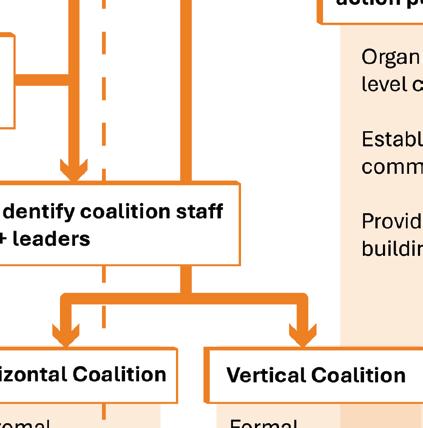

2. The core group of a coalition starts to form either from creating a new collaborative entity or reconstructing an existing coalition/organization. Different stakeholders such as public domain professionals,

institutions or residents start to engage in the process. Recruitment starts and is influenced by the context from a geographic, historic, and political context paired with the community’s willingness to advocate for mutual interest

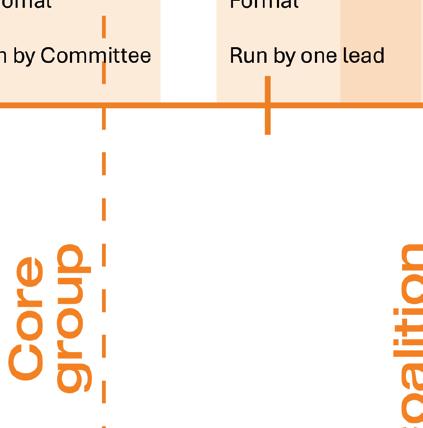

3. The coalition is then formed. That is when it becomes more defined in terms of leadership structure and staff, which shape up in either a horizontal or vertical coalition (Yu, Xu, and Dong 2019). The latter is run by one leader within a formal structure, whereas the former is run by a committee that func-

tions more informally through collaboration between the different organizations within the committee (Jenkins et al. 2022).

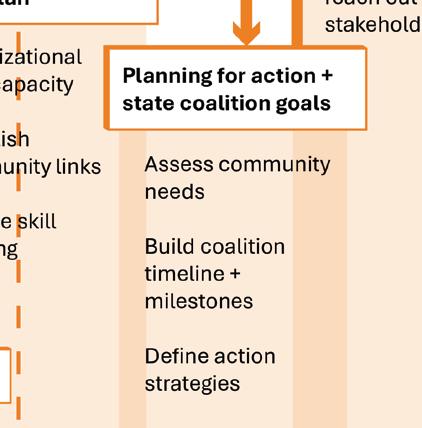

4. The action plan then starts to be formalized. Skill building, community connections, and organizational capacity open the way for the definition of goals, strategies, tools, and target audiences. The action plan is then published, setting the scope to help in reaching out to more constituents and stakeholders for support.

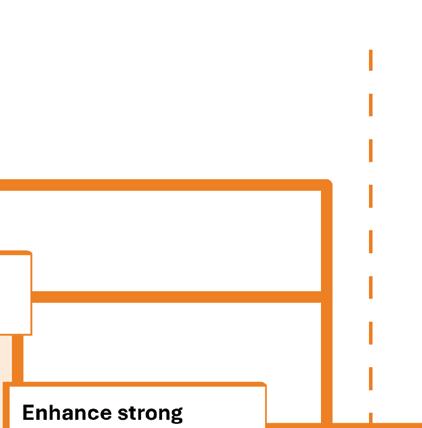

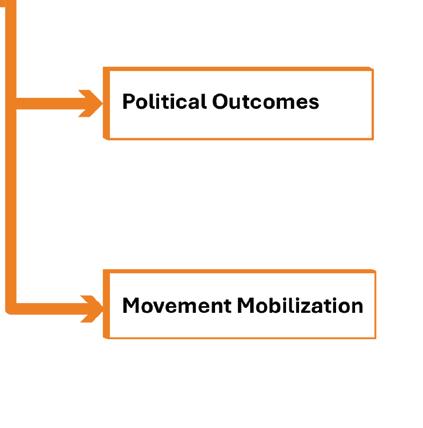

When implementation starts, the coalition is in full effect, and focus is on maintenance. This phase includes working towards the goals, engaging with community, implementing strategies to retain coalition membership, mobilizing resources, and improving leadership coordination (Kegler, Rigler, and Honeycutt 2010). Depending on associated outcomes, this can result in survival, organizational change, political outcomes, and movement mobilization (Jenkins et al. 2022).

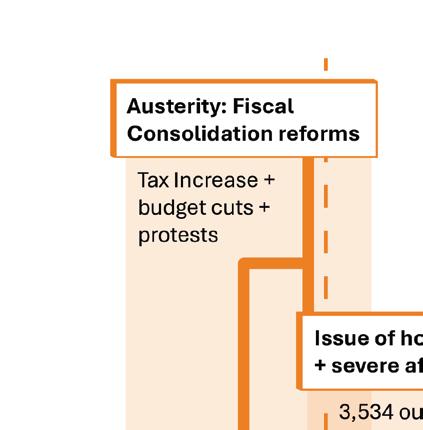

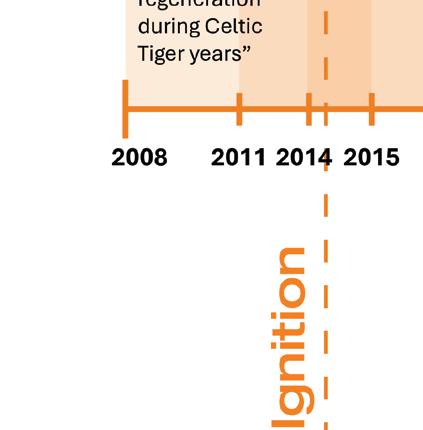

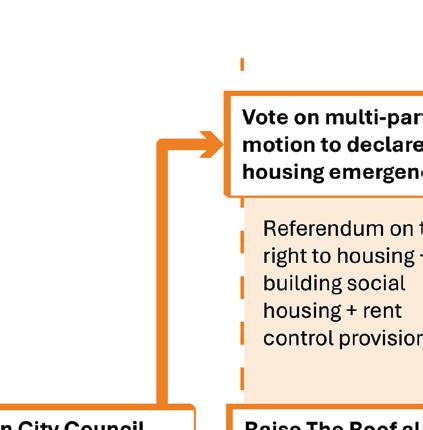

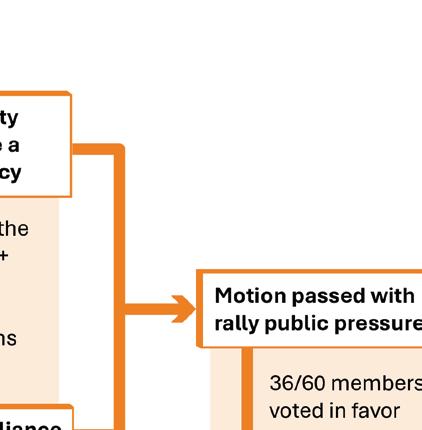

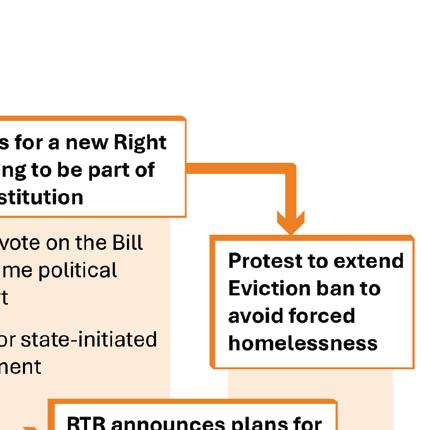

This is true of the RTR Coalition Timeline (figure 6) we were able to piece together through

different online media outlets of the published events as well as comparative literature. The coalition was the result of housing groups joining forces after the economic crises that hit Ireland (Lima 2021), which had led to a severe housing affordability crisis in Dublin. The union of these organizations led to the formalization of RTR as a vertical coalition shortly after the National Day of Action and Protests in 2018 (Shabeer 2018). The mobilization only kept growing in number from that point in time and would reach up to 15,000 participants. More than 50 organizations joined forces to lobby for policy change with organization efforts led by the Irish Congress

Trade Union (ICTU). It is remarkable to realize the evolution of this coalition’s actions from leading mass mobilization in its early stages to collaborating with public figures for housing policy changes.

It Takes Roots states that the organization launched as a collaboration between its founding members in 2014 during the organization of the People’s Climate March, during which approximately 400,000 protesters marched in the streets of Manhattan. The protest was organized to coincide with a United Nations climate change summit. It Takes Roots was created “immediately after” the 2016 presidential elections.

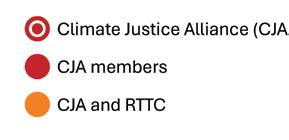

It emerged from the collaboration of groups like the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, Indigenous Environmental Network, Climate Justice Alliance, and Right to the City Alliance. These organizations center the voices of Indigenous peoples, Black communities, immigrants, and working-class neighborhoods.

Mass mobilization is central to their strategy. They organize by building local leadership, fostering community alliances, and connecting struggles across issues and geographies. Their mobilizations often coincide with major global events — like the UN Climate Summits — where they bring delegations, lead direct actions, and host People’s Assemblies to elevate frontline solutions. Digital tools, popular education, and grassroots media amplify their efforts, while horizontal decision-making ensures accountability to their base. Through this, they challenge systems of oppression and assert community-led visions for justice.

What struck us most was their ability to organize across the country. Figure 7 maps the location of all organizations within ITR. But to understand this coalition building precedent in detail, we needed to see how the core group and its subsequent members came together. Figure 8 illustrates the four main groups that form ITR. Within these groups, there are multiple coalitions that respectively came together. But it’s not just these coalitions that make up the group. As seen in figure 9, ITR also has coalitions that are simultaneously part of multiple groups. This enables them to effectively form a tight-knit community and form mobilizations all over the country.

One of the limitations of mapping is the lack of clarity around the exact role played by each of these coalitions within It Takes Roots (ITR). While the alliance is composed of several networks, the specific contributions, responsibilities, and degrees of influence of each within the broader structure of ITR are not clearly delineated. This ambiguity makes it difficult to assess, without further research, how strategic decisions are made, how resources are allocated, or how priorities are set across campaigns. Furthermore, without a transparent understanding of each coalition’s role, it becomes challenging to evaluate how internal power dynamics shape the alliance’s agenda and its ability to mobilize effectively.

NYC is home to a diverse and dynamic landscape of housing coalitions that play a crucial role in advocating for tenant rights, affordable housing, and community control over development. These coalitions bring together tenants, grassroots organizations, legal advocates, and policy groups. They focus on resisting displacement, challenging real estate speculation, and promoting rent control and public housing investment. Many are rooted in long-standing struggles led by working-class communities of color, and they employ a range of strategies from direct action and tenant organizing to policy advocacy and legal support. By coordinating citywide campaigns and leveraging the collective power of neighborhood-based groups, local housing coalitions have become key players in shaping the discourse and policies around housing justice in one of the most expensive and unequal housing markets in the world.

However, on further inspection of various coalitions that address the housing crisis, we found a saturated ecosystem of organizations, each offering too many distinct approaches to remarkably similar challenges. While this diversity reflects the urgency and complexity of the housing crisis, it also reveals an oversaturation of coalitions operating within overlapping geographic and thematic spaces. Many of these groups advocate

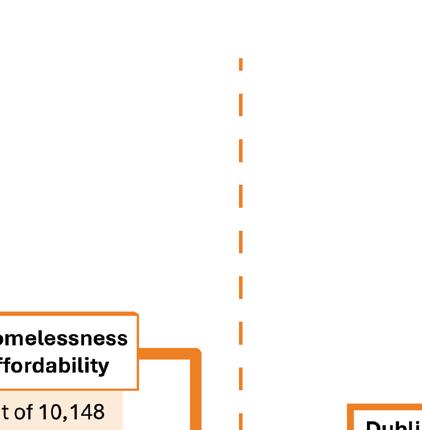

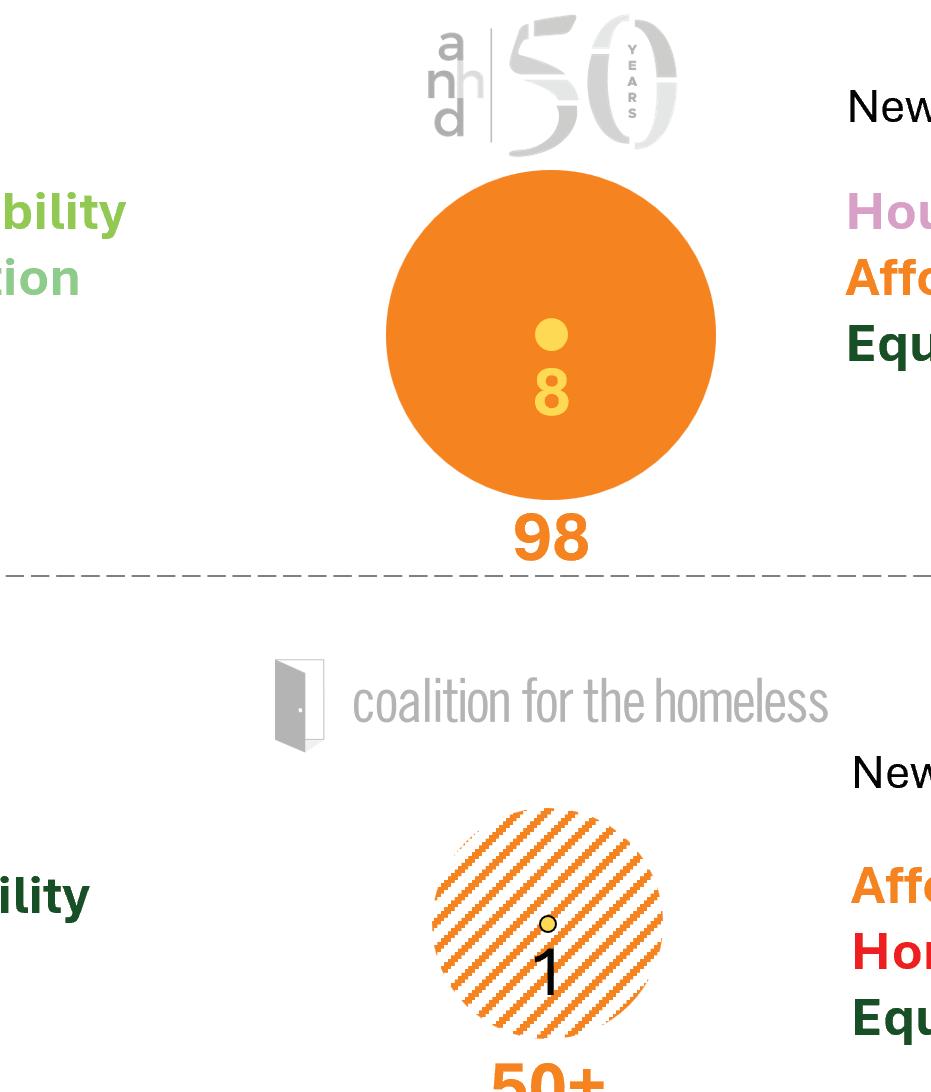

for affordable housing, tenant protections, and resistance to gentrification or displacement, yet they often do so through different frameworks — be it community land trusts, rent control advocacy, public housing reform, or anti-eviction organizing. This proliferation leads to fragmentation, duplication of efforts, and competition for limited funding and political influence. In some cases, it obscures opportunities for coordinated action and creates confusion among residents about which group to turn to. Although their existence speaks to the depth of grassroots mobilization, this landscape would benefit from greater alignment and strategic collaboration to maximize impact and build unified power. To take it a step further, we analyzed nine housing coalitions (figure 10) that are functionally addressing housing issues. What we found was that many of the coalitions had very similar goals, intents, and to a certain extent, even strategies. Some of them have been a part of the city for more than a decade. These coalitions primarily address affordability, homes for the homeless, housing justice, and equity.

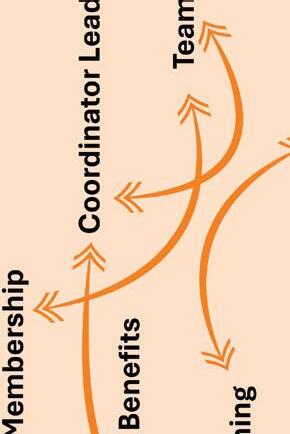

When beginning to tailor our analysis to NYC, the earlier theoretical analysis and stakeholder mapping acted as roadmaps once we narrowed down our focus. It was important to compare RTR and ITR at a high level, as each of them were able to achieve concrete outcomes. In figure 11, we outline in the table general coalition metrics that we used to finalize our first stage of analysis, focusing on the type of coalition, core group leadership model, number of alliances, sector, mode of communication, funding, ignition nodes, as well as noted impacts.

We then added to our comparative framework two NYC-based coalitions to assess successful strategies, as well as potential barriers:

• Yes to Housing: We conducted a general analysis of the elements within the City of Yes Housing Plan that this coalition supports, and the complex dynamics of coalition members and boards when approving the plan. As a result of this analysis, we were able to generalize core barriers.

• Housing Justice for All: We conducted a timeline assessment to understand the concrete policy changes that it was able to achieve both at a city and state level, and

the stakeholder composition that managed on achieving such results. We were able to generalize strategies that coalitions can apply to strengthen housing access and affordability.

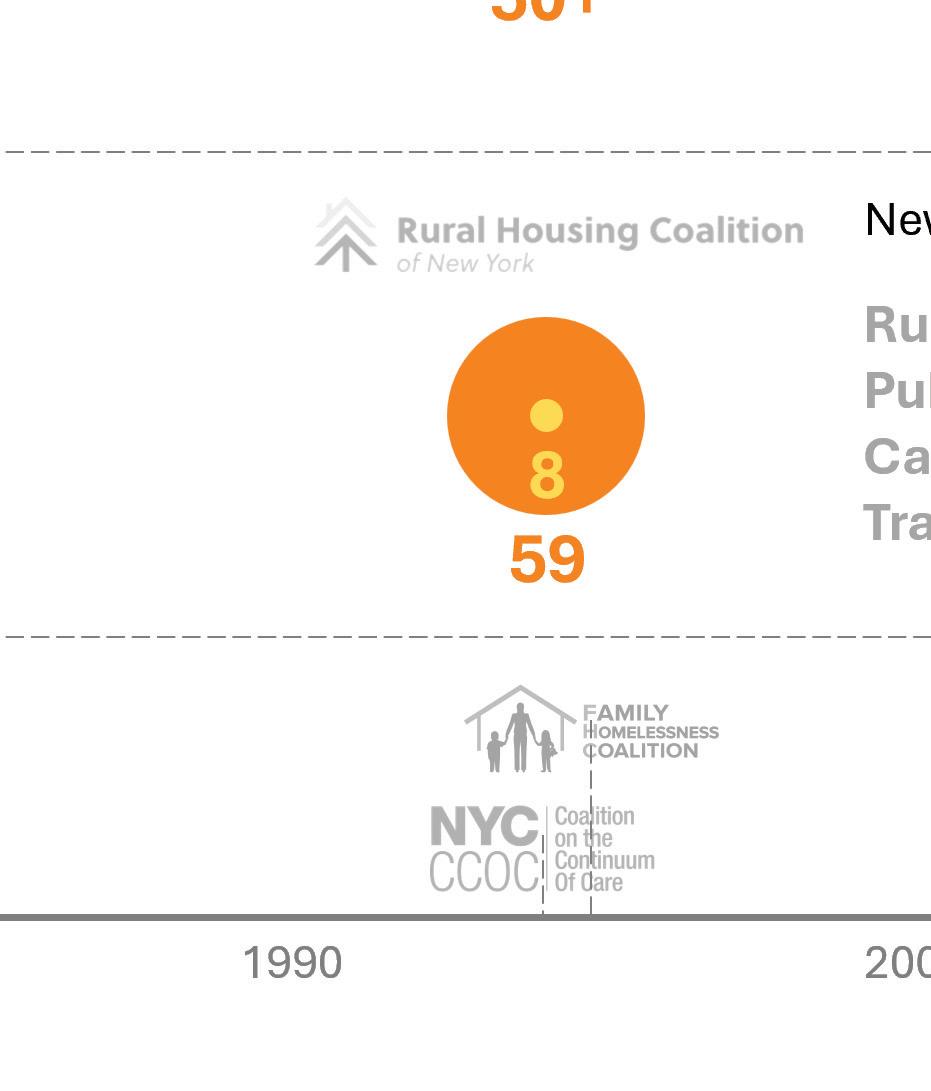

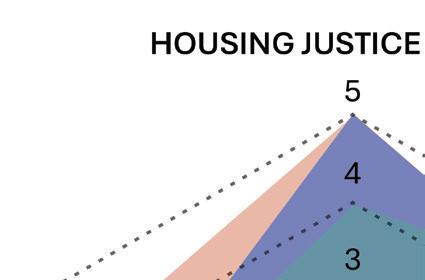

In tandem with these comparative assessments, we reapplied our understanding of the metrics of success and focused our efforts to six NYC-based coalitions: Housing Justice for All (HJ4A), Yes to Housing (YTH), Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD), Rural Housing Coalition (RHC), Coalition of the Continuum of Care (COTCOC), and Family Homelessness Coalition (FHC).

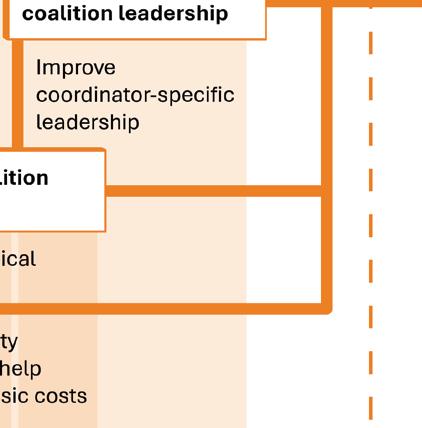

We assessed them based on six different metrics with a scoring system of 1 to 5 (Figure 12):

1. Level of establishment: Based on the year the coalition was established and how well it is established as a group in community.

2. Relationship growth: Based on the growth of the core group since the coalition’s establishment.

3. Social change impact: Based on the victories that the coalition has managed to achieve such as legislative wins/policy action, the number of protests it organized, the variety of workshops/conferences/events that the coalition held

Compiled by authors, 2025

4. Use of campaign tools: Based on the diversity of the outreach material, such as resources distributed during in-person events, and digital media presence, publication of digital toolkits and guidebooks for residents and constituents.

5. Allies composition: Based on the diversity of coalition members and groups as well as the types of groups that are part of the alliance (such as the intersection of housing cause with a climate group).

6. Community reach: Based on how many people have active members as well as protest presence, conference attendance, and so on.

First assessing the level of establishment, we see ANHD as the longest standing coalition. Looking at relationship growth we saw that COTCOC has had the highest growth rate of groups since its establishment. HJ4A remains the leading coalition with its number of victories and in terms of its social change impact, as well as in terms of its diverse use of resources for campaigning efforts. When understanding allies’ composition, both YTH and ANHD lead with the most diverse set

of stakeholders. Lastly, HJ4A ranked highest in terms of community reach, with the number of constituents was able to engage with.

We were able to realize barriers and strategies to apply within housing coalitions based on the assessments we made for YTH and HJ4A.

The City of Yes for Housing Opportunity is a major initiative in NYC to address the ongoing housing crisis through zoning reform, that focuses on building 80,000 new homes in 15 years. It aims to make it easier to build more housing citywide, to promote affordable and mixed-income housing, and reduce barriers created by outdated zoning laws. This plan was published in the summer of 2023, and was under public review up until it was adopted at the beginning of 2025. Yes to Housing was formed because of this Plan. The Housing Opportunity Plan focuses its efforts on 9 different proposals within three different scales: 1) Low-density proposals focus on town center zoning, transit-oriented development, accessory dwelling units and district fixes, 2) Within medium and high density, it primarily focuses on universal affordability preference, and 3) City-wide proposals focus on lifting costly parking mandates, converting non-residential building, and promoting small and shared housing as well as campus

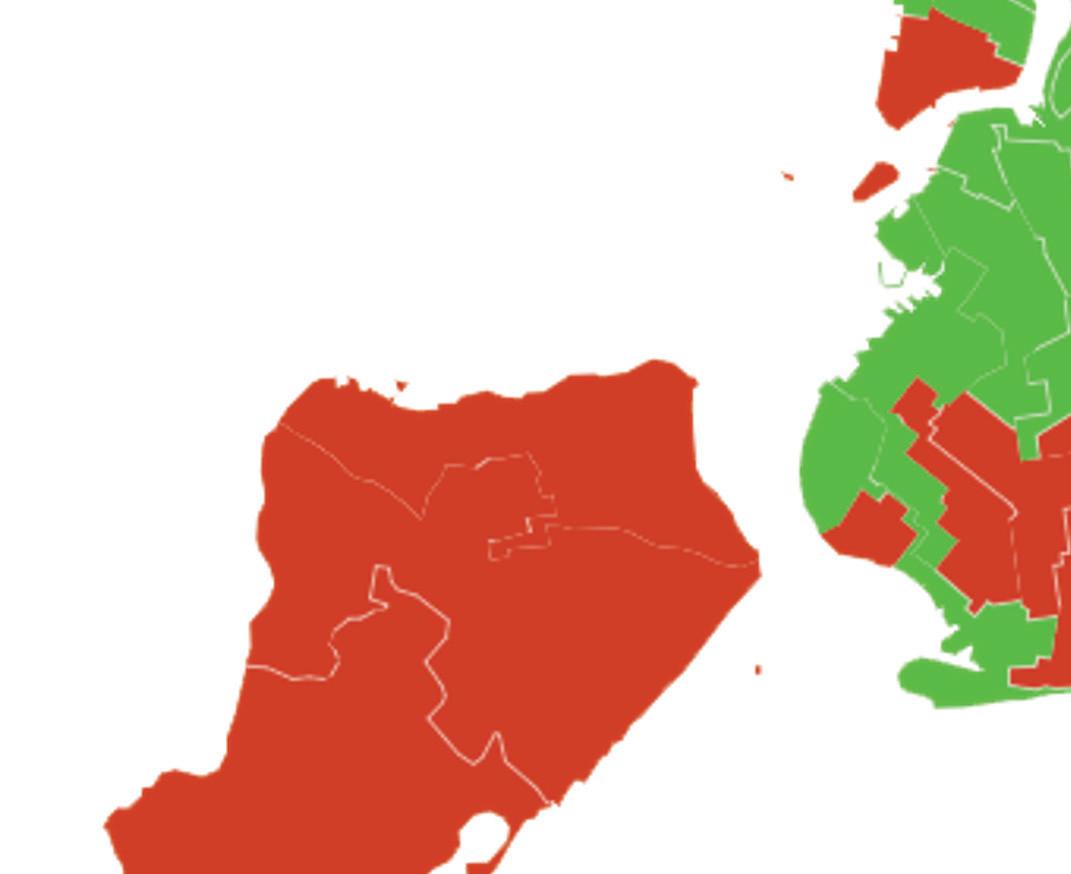

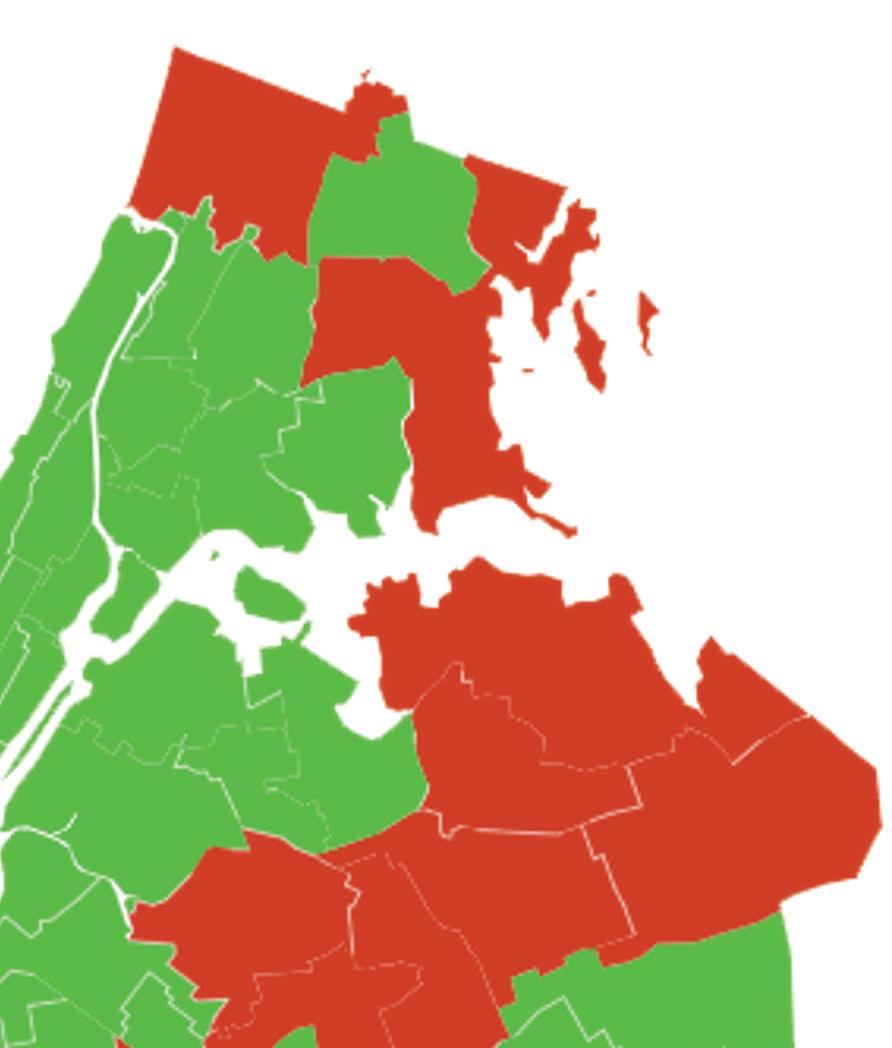

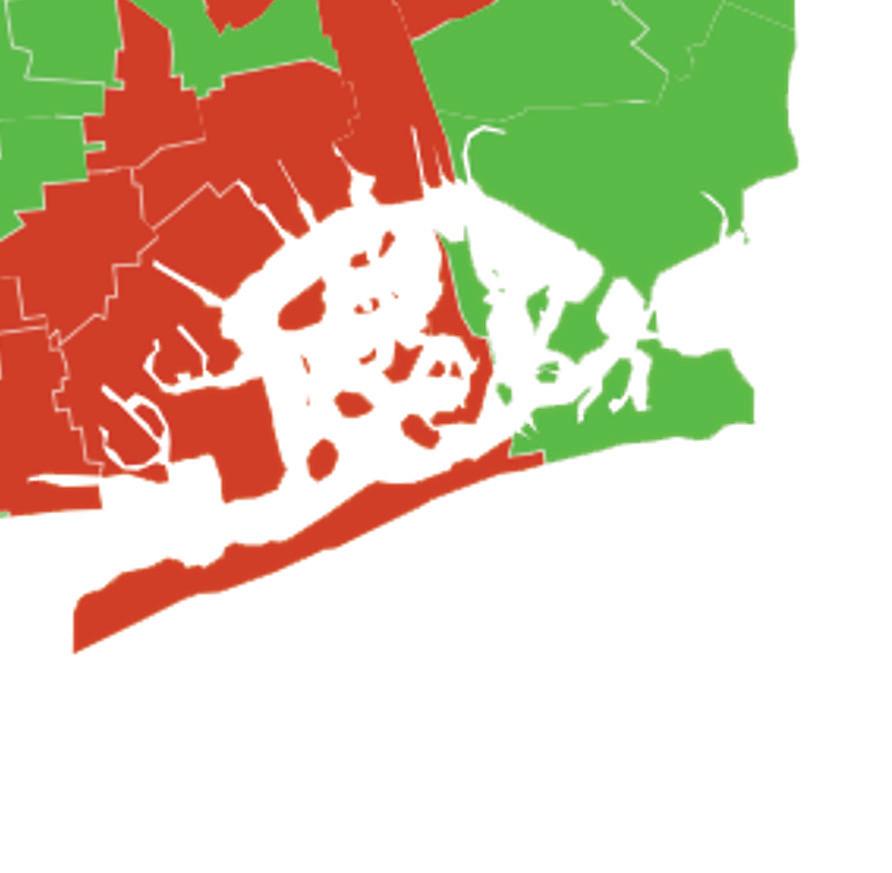

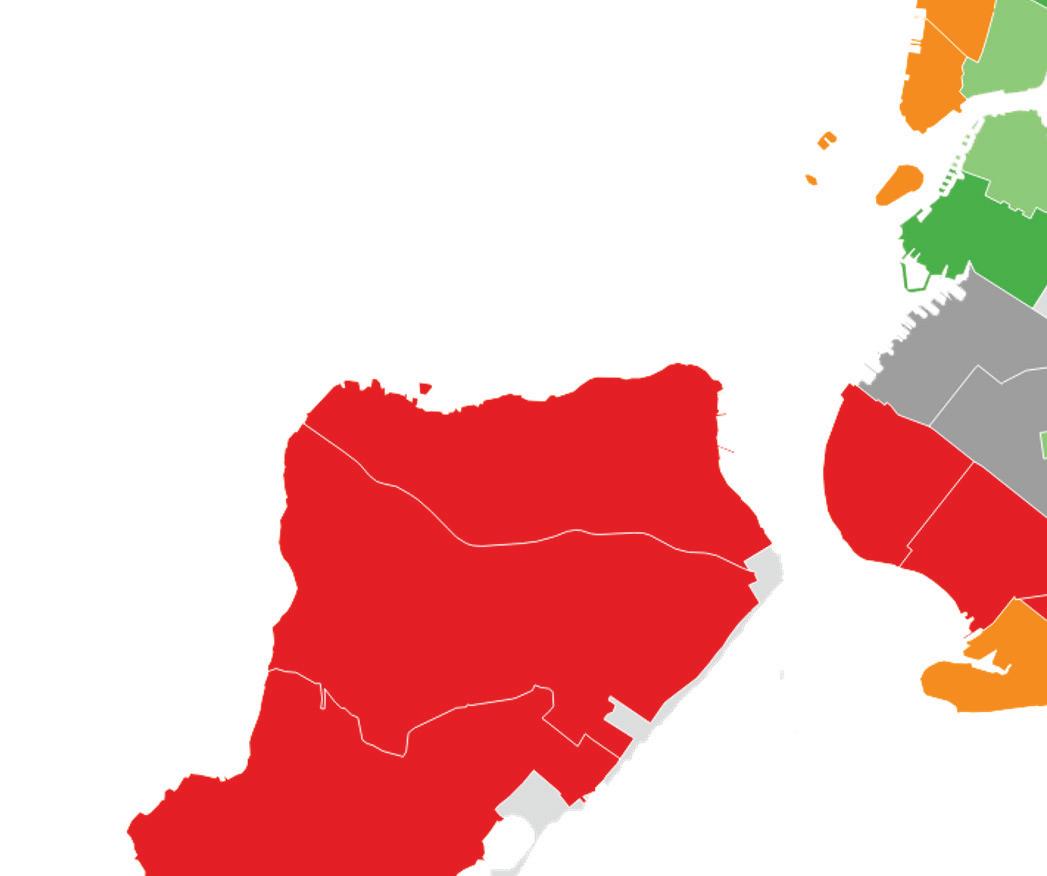

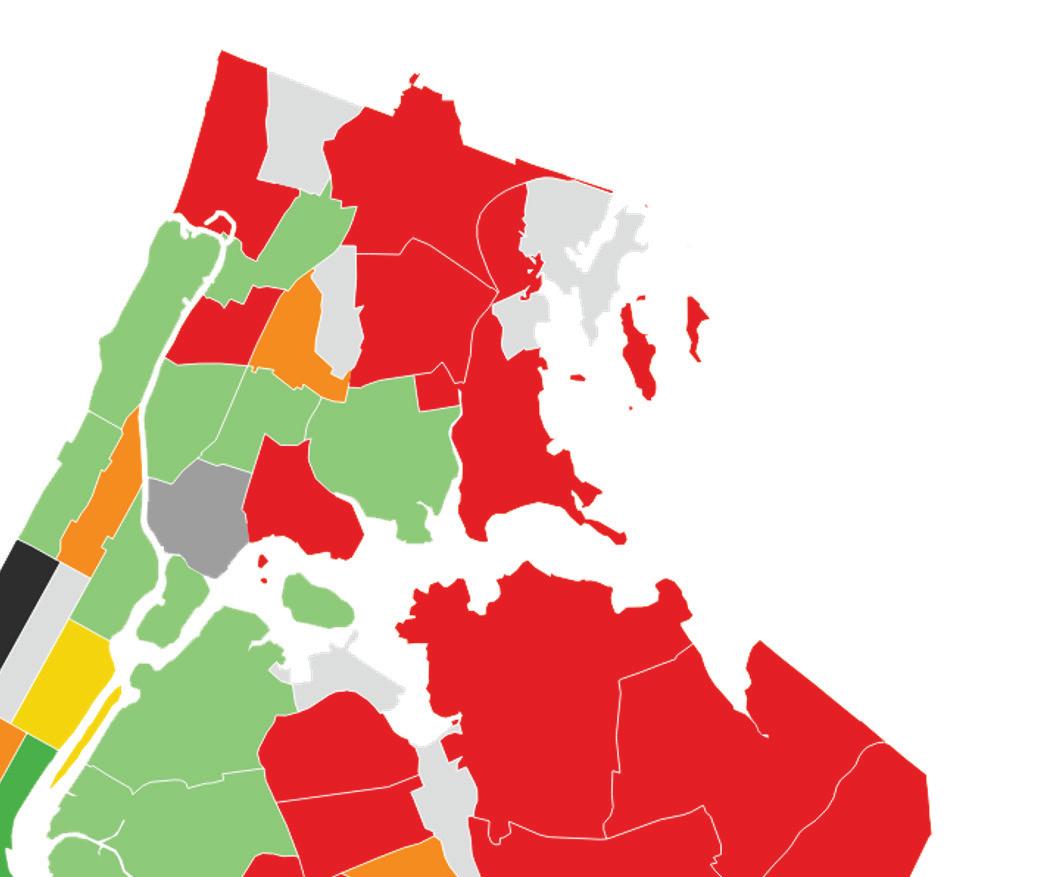

infill (NYC Department of City Planning 2024). While we can see these proposals as reasonable, not everyone in NYC agrees (Figure 13).

On the left of the figure, you can see that out of 51 councilmembers in NYC, there were still 20 that opposed the proposal due to conflicting strategies of parking, infrastructure load, homogenous zoning regulations, and increased disaster risk. It’s not just council members but also community boards who have shown their disapproval to the recommendations (Evelly 2024). There are only two community boards that are favorable to the proposal, with 57 others conditionally favorable and unfavorable. We realized that some of these barriers also apply to the larger coalition context.

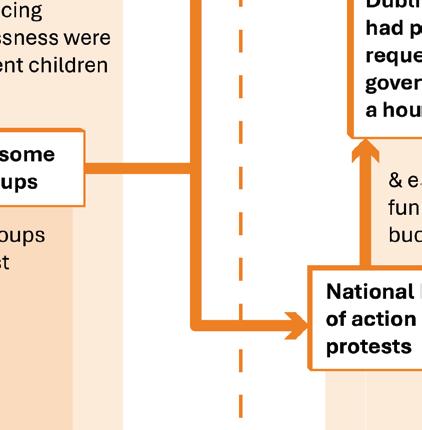

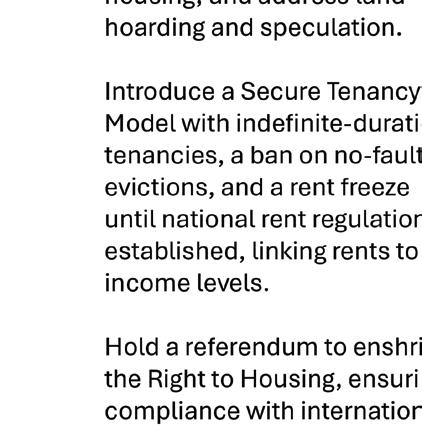

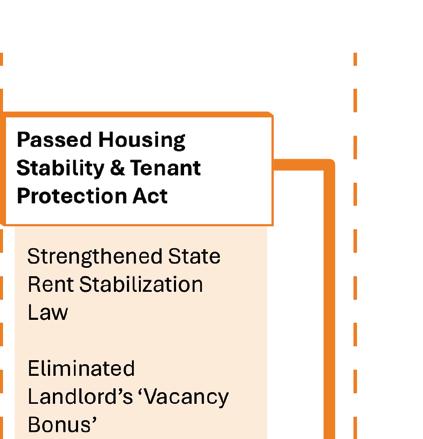

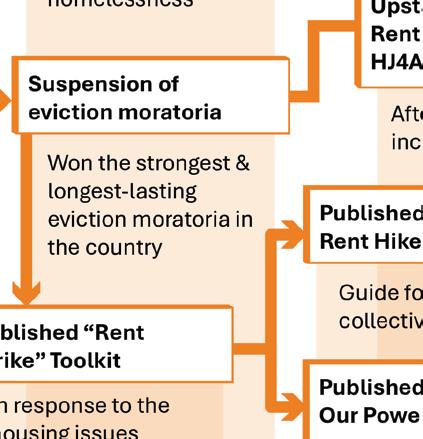

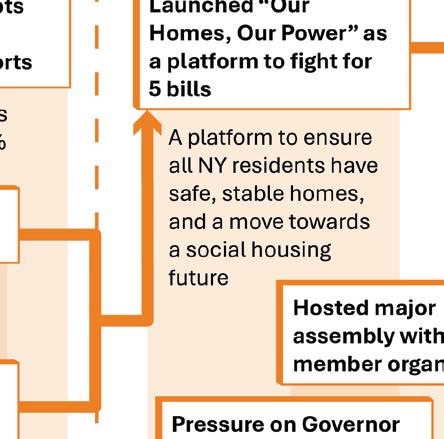

We investigated HJ4A as one of the most prominent coalitions that recently formed in 2017 after a group of 14 grassroots community groups met in Albany NY, to fight against real estate lobbyists who were trying to remove rent protection laws set to expire in 2019. We applied our theoretical framework and timeline model to this case and realized the impacts as represented in Figure 14.

HJ4A focuses on statewide initiatives, and started with a Housing Justice Day of Action in

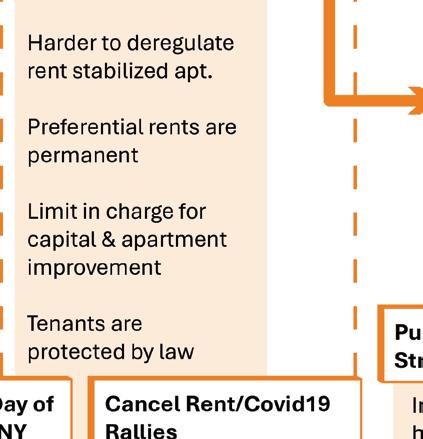

Albany in November 2018 shortly after its creation. It had major reform victories. One of the coalition’s Landmark Legislative victory to date was the Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act that passed in 2019 (DeVaan 2021), which ends vacancy deregulation, limits security deposits, and protects tenants from fast-track evictions and rent hikes.

Later, this was followed by eviction moratoria, one of the longest-lasting in the country, and rent control adoption in Kingston, one of the first after the pandemic hit (Chang 2022). This coalition has been supported financially,

primarily by Voices of Community Activists and Leaders (VOCAL NY),a grassroots organization that joined coalitions by playing a lead role in campaigns to strengthen rent laws and build more affordable housing.

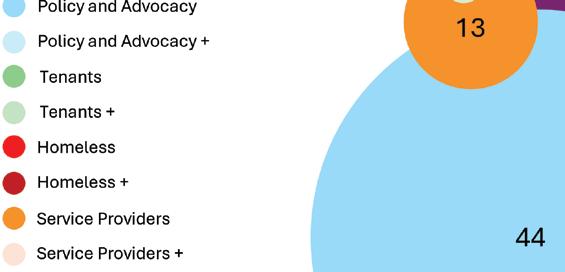

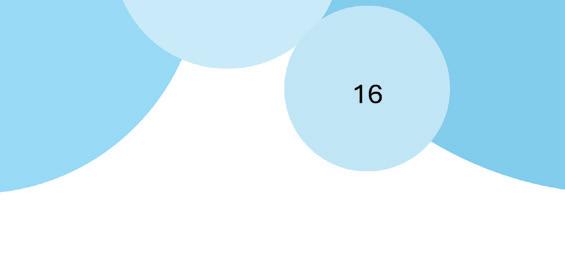

Figure 15 underscores how the largest groups that form the coalition are tenant organizations and policy/advocacy groups. Some of the organizations also overlap with each other. For example, an organization might address policy/ advocacy, homelessness, and service provision. For this reason, we have labeled them based on their primary focus.

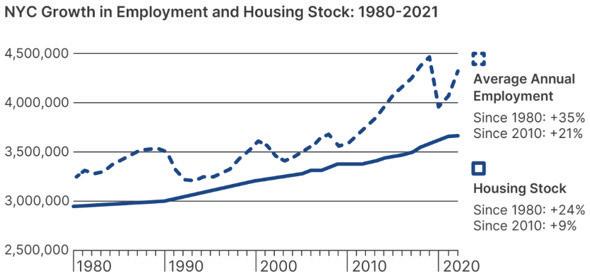

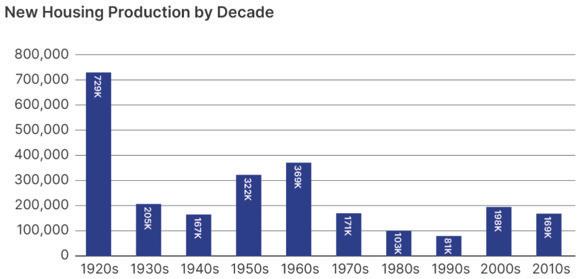

Over the past 40 years, NYC has created more jobs than homes. When more people need homes than are available, rents go up, landlords have more leverage, and disadvantaged tenants are forced into lower-quality living situations (NYC Department of City Planning 2025).

Regulations have restricted new housing production. In the past, when housing was more affordable, New York built much more housing than it does today. But over time, more barriers were created that hindered the construction of housing that people need (NYC Department of City Planning 2025).

We identified the following barriers that coalitions may face in NYC:

1. Community Opposition: Many neighborhoods resist new developments, fearing changes to “neighborhood character,” congestion, or property values.

2. Political Hurdles: Navigating multiple layers of city and state bureaucracy, securing funding, and dealing with shifting political priorities slows coalitions.

3. Time-consuming Process: Building a coalition from ground zero takes a lot of time making it difficult to keep the coalition

motivated towards the goals. Moreover, the process is even longer when the coalition does not have a political leader in their core group, who can heavily advocate in governmental settings for policy reform.

4. Financing Challenges: Coalitions require public subsidies, tax credits, and private investment. Putting these together takes years and can fall apart if one piece fails.

5. Access to Data: Many coalitions find it difficult to access private group data, making it a time-consuming process to create meaningful relationships.

6. Displacement Pressures: In some cases, new development accelerates gentrification, leading to mistrust of housing coalitions and protests from residents.

After understanding the coalitions from the ground up, we can see how different strategies they led with had resulted in major milestones, and how these strategies can also be applied to New York housing coalitions. We identified the following strategies that coalitions may apply in NYC: organize protests, rallies, campaigns, and community leaders, support tenants in forming unions throughout different housing typologies, coordinate press conferences and media presence, distribute resource training material through toolkits (digital and physical), engage through online platform advocating for varying legislations, connect with other groups across city movements and groups, lobby for housing policy reform for varying causes, and draft new housing policy frameworks.

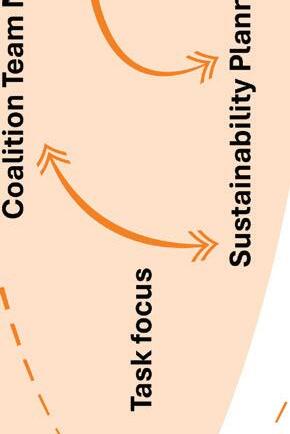

This all brings us to the idea of a supergroup, or a coalition of coalitions. If this were to be implemented today, it can be visualized as a broad alliance that brings together multiple coalitions, organizations, advocacy groups, tenant associations, nonprofit developers, labor unions, and/or political actors who each have their own internal memberships and goals, but who coordinate under a common agenda related to housing issues.

Mission statement: We unite housing coalitions across New York City to defend tenants’ rights, fight displacement, expand affordable housing, and ensure housing as a human right. Through collective action and shared power, we build a just, equitable city for all New Yorkers.

A super coalition would serve as a unifying force that brings together fragmented housing efforts under a cohesive and strategic umbrella. By aligning core issues —such as affordability, rent stability, tenant rights, housing for the homeless, eviction protection, equity, and sustainability — it could streamline advocacy efforts, amplify political pressure, and offer a more comprehensive policy vision. This coalition would not aim

to erase the unique strengths or approaches of individual groups. It would instead foster coordination, reduce redundancies, and build collective power. It would work across levels, from grassroots mobilization to policy lobbying, integrating legal advocacy, direct action, public education, and housing development models like community land trusts or social housing. Additionally, a super coalition could ensure that solutions are not only just and inclusive but also climate-resilient and rooted in long-term sustainability. By bridging urban and regional divides and centering the leadership of impacted communities, it could push for systemic change at scale.

equitablecityforall NewYorkers.

Over 2,500 housing focused organizations operate in New York, in the form of non-profits, CDCs, tenant groups as well as co-ops with more than 5,000 organizations providing housing related services. Within this pool of community groups, different coalitions have formed. We recommend that this supercoalition follows these actionable items:

• Fill in the Gaps: Connect coalitions that function with different missions/strategies and in different areas of the city to fill in the housing gaps/needs with the multi-pronged approach.

• Empower a Collaborative System: Aid smaller coalitions in reaching their constituents through the more established coalitions.

• Relationship Building: Ensuring that the turnover of the coalition is maintained by building new relationships and ensuring groups that may not want to actively participate to maintain a neutral direction, as well as ensure that the coalition is communicating to the needed communities/members.

• Strengthen Network: Filter groups that may not be directly implicated and frame the work of the coalition that may benefit their constituents.

Figure 18 proposes a conceptual framework for the types of connections and scales that we would want the supercoalition to function within.

It becomes clear how a diverse, community-led supercoalition can lead to significant milestones in the fight for housing justice. These approaches offer valuable lessons that can be applied to NYC’s housing coalitions more broadly. By organizing impactful protests, supporting the formation of tenant unions, hosting press conferences, and distributing critical resources, coalitions can strengthen their grassroots base. Additionally, engaging members through multiple platforms, forging connections with other local movements, and lobbying for bold housing reforms — all while developing new, community-driven policy frameworks — can collectively drive meaningful, systemic change. These tactics, when strategically aligned, have the power to transform fragmented efforts

into a unified, citywide force for housing equity.

Future research should examine the leadership dynamics that would emerge when integrating multiple coalitions under a single framework. This includes analyzing how roles, responsibilities, and decision-making processes would be coordinated to ensure cohesive action. The research should also identify the most effective scale at which to initiate this “supergroup” — whether it begins at the community board level, the borough level, or at the broader city scale — considering the advantages and limitations of each tier in fostering collaboration and achieving impact.

ANHD. n.d. “About Us.” ANHD Building Community Power since 1974 (blog). https:// anhd.org/about/.

Chang, Clio. 2022. “Kingston Becomes First Upstate City to Adopt Rent Control.” Curbed. August 2, 2022. https://www. curbed.com/2022/08/kingston-upstate-rent-control.html.

Climate Justice Alliance. n.d. “It Takes Roots.” Climate Justice Alliance (blog). Accessed May 13, 2025. https://climatejusticealliance. org/workgroup/it-takes-roots/.

DeVaan, Bella. 2021. “Building Tenant Power with the Housing Justice for All Coalition.” Inequality.Org (blog). July 15, 2021. https:// inequality.org/article/tenant-power-housing-justice/.

Evelly, Jeanmarie. 2024. “How Each NYC Councilmember Voted on City of Yes for Housing.” City Limits (blog). December 6, 2024. https://citylimits.org/ how-each-NYC-councilmember-voted-oncity-of-yes-for-housing/.

Housing Justice for All. n.d. “Who We Are.” Housing Justice for All (blog). https://housingjusticeforall.org/who-we-are/.

ICTU. n.d. “Raise the Roof Calls on TDs to Restore the Eviction Ban.” Irish Congress of Trade Unions. Accessed May 11, 2025. https://www.ictu.ie/publications/raiseroof-calls-tds-restore-eviction-ban.

Influence Watch. n.d. “It Takes Roots (ITR).” Influence Watch (blog). https://www. influencewatch.org/organization/it-takesroots-itr/.

Jenkins, Garrett J, Brittany Rhoades Cooper, Angie Funaiole, and Laura G Hill. 2022. “Which Aspects of Coalition Functioning Are Key at Different Stages of Coalition Development? A Qualitative Comparative

Analysis.” Implementation Research and Practice 3 (January):26334895221112694. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895221112694.

Kabateck Strategies. 2023. “Achieving Successful Coalition Building: Strategies and Tips.” May 26, 2023. https://kabateckstrategies. com/successful-coalition-building/.

Kegler, Michelle C, Jessica Rigler, and Sally Honeycutt. 2010. “How Does Community Context Influence Coalitions in the Formation Stage? A Multiple Case Study Based on the Community Coalition Action Theory.” BMC Public Health 10 (1): 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-90.

Kochhar, Sarab. 2013. “A Conceptual Model for Measuring Coalition Building Effectiveness.”

Lima, Valesca. 2021. “Housing Coalition Dynamics: A Comparative Perspective.” Comparative European Politics 19 (4): 534–53. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-02100245-6.

Mwangi, Haron, and Martha Njiir. 2021. Mapping Coalitions: Mapping out Coalitions, Collaborations, Partnerships and Networks for Media and Civil Society in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fojo: Media Institute. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-118245.

New York Housing Conference. n.d. “Yes to Housing.” NYHC (blog). https://thenyhc. org/city-of-yes/.

New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. 2009. “Chapter 3. Overview of NYC.”

In Coordinated Public Transit-Human Services Transportation Plan for NYMTC Region, 1–33. New York Metropolitan Transportation Council.

NYC Continuum of Care. n.d. “NYC Continuum of Care.” https://www.NYC.gov/site/

NYCccoc/about/about-the-NYC-coc.page.

NYC Department of City Planning. 2024. “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity - An Illustrated Guide.” https://www.NYC.gov/assets/ planning/downloads/pdf/our-work/plans/ citywide/city-of-yes-housing-opportunity/ housing-opportunity-guide-illustrated.pdf.

NYC Department of City Planning. 2025. “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity Story Map.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. May 6, 2025. https:// storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f266a53c9cda42d5b7f63b57dc08f849.

NYC Department of City Planning. n.d. “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity.” https:// www.NYC.gov/content/planning/pages/ our-work/plans/citywide/city-of-yes-housing-opportunity#overview.

Raise the Roof. n.d. “Raise the Roof Supporters.” Raise The Roof Homes for All. https://www. raisetheroof.ie/about-raise-the-roof.

Shabeer, Muhammed. 2018. “Raise the Roof Campaign Demands an End to Housing Crisis in Ireland.” Peoples Dispatch (blog). October 6, 2018. https:// peoplesdispatch.org/2018/10/06/ raise-the-roof-campaign-demands-an-endto-housing-crisis-in-ireland/.

VOCAL New York. n.d. “Homelessness.” VOCAL-NY (blog). Accessed May 13, 2025. https://www.vocal-ny.org/issues/homelessness/.

Yu, Baojun, Hangjun Xu, and Feng Dong. 2019. “Vertical vs. Horizontal: How Strategic Alliance Type Influence Firm Performance?” Sustainability 11 (23): 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236594.

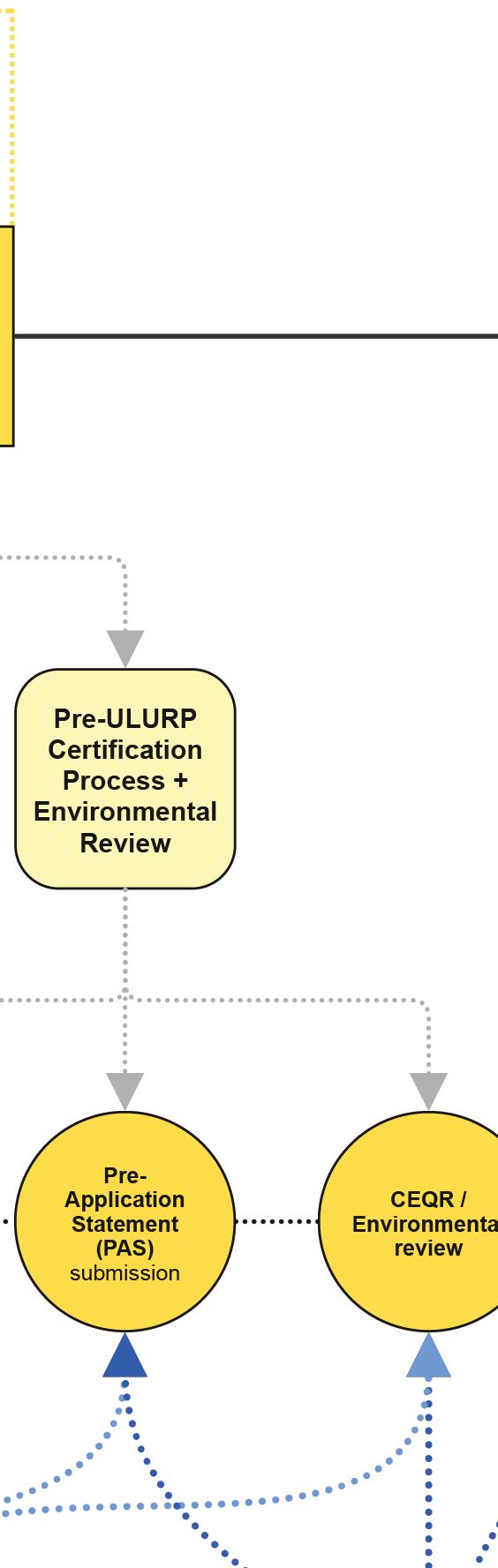

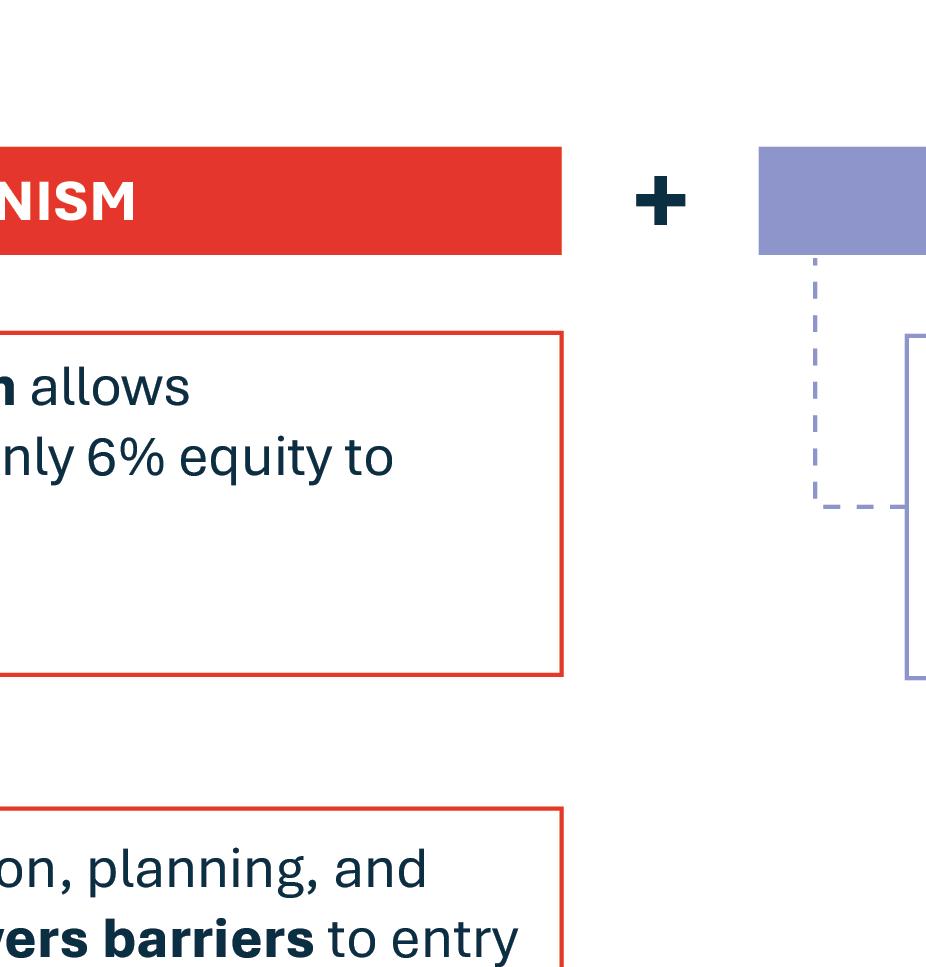

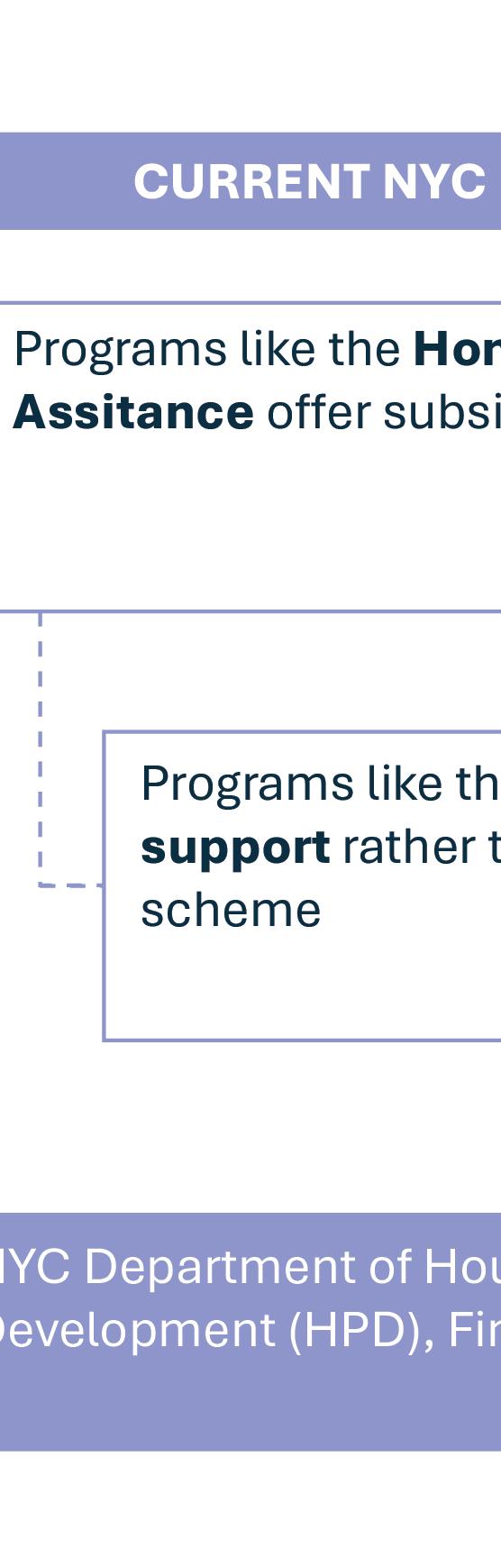

This memo examines procedural barriers that impede housing development in NYC, with a particular focus on those introduced by the Uniform Land Use Procedure (ULURP). As NYC faces an acute housing crisis, reforming key components within ULURP represents a critical opportunity to significantly increase housing production. The research is especially timely given the ongoing City Charter Revision process launched by Mayor Adams in December 2024, which has ULURP reform as a central theme and offers a unique chance to streamline housing provision across the city.

Our international comparative analysis identified four critical areas where NYC’s ULURP process creates unnecessary barriers to housing development, despite serving important democratic functions:

• Community engagement: Current community input in NYC is often reactive and late stage, leading to increased propensity for opposition during the ULURP process. Indonesia’s E-Musrenbang system demonstrates an alternative of transparent, early, and continuous community involvement through the development process in order to build broader support.

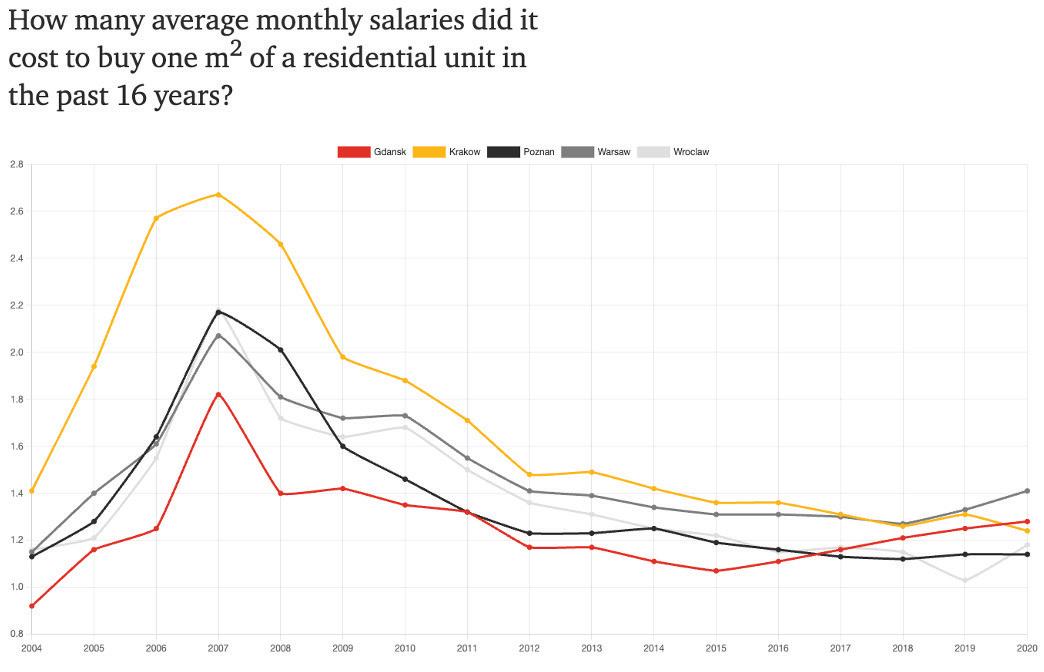

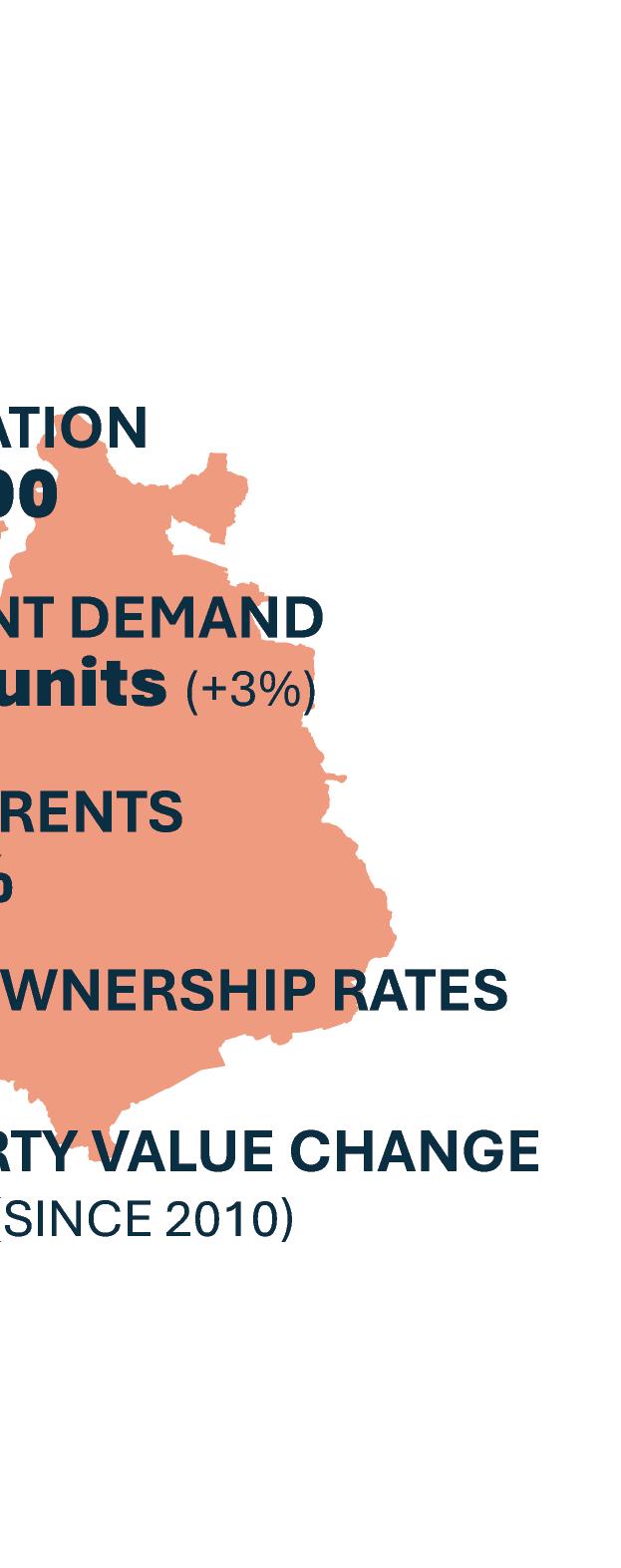

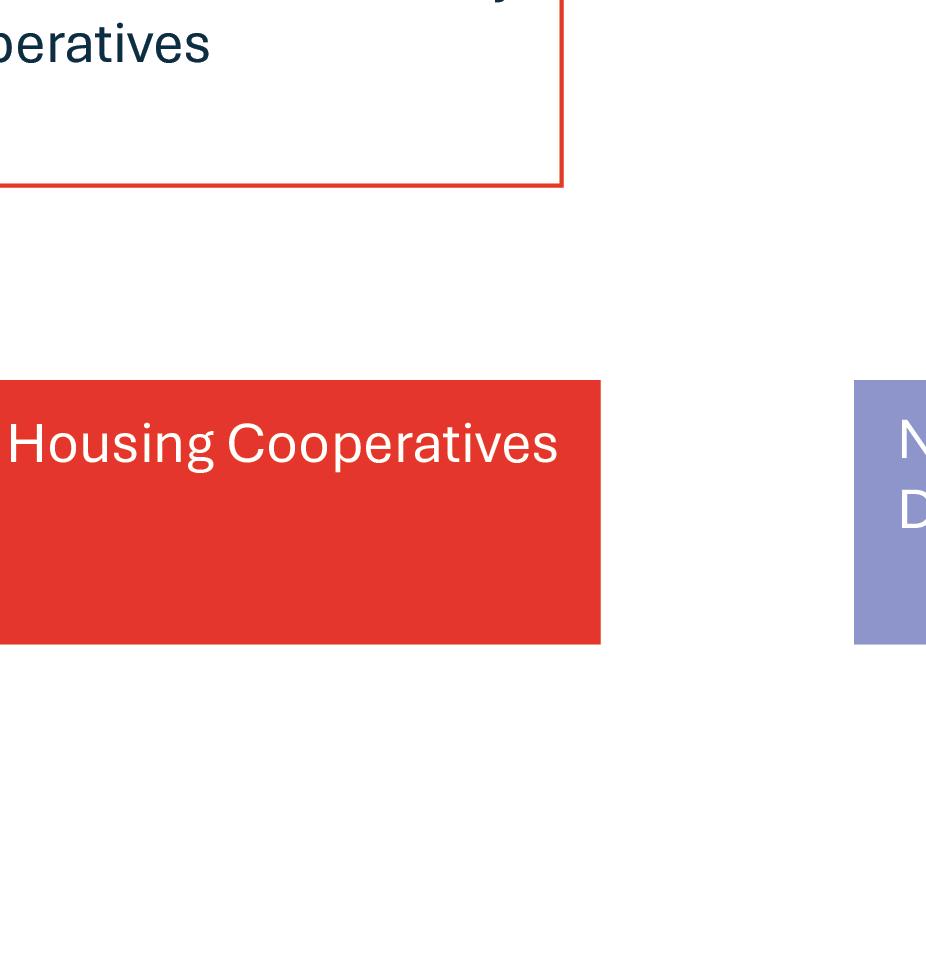

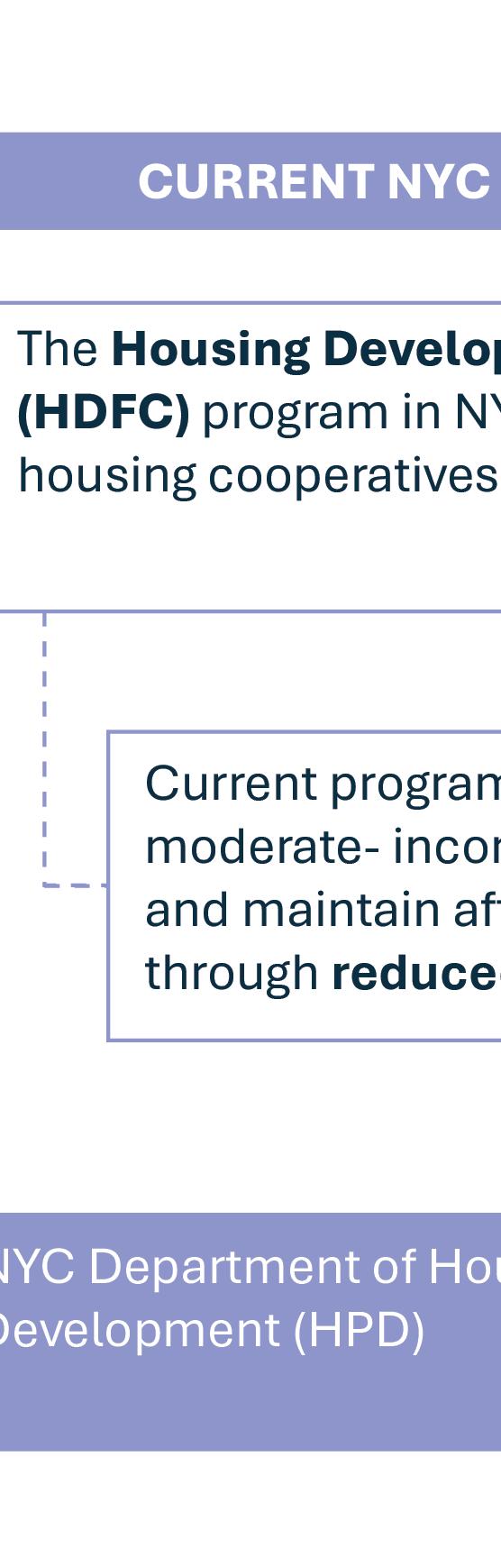

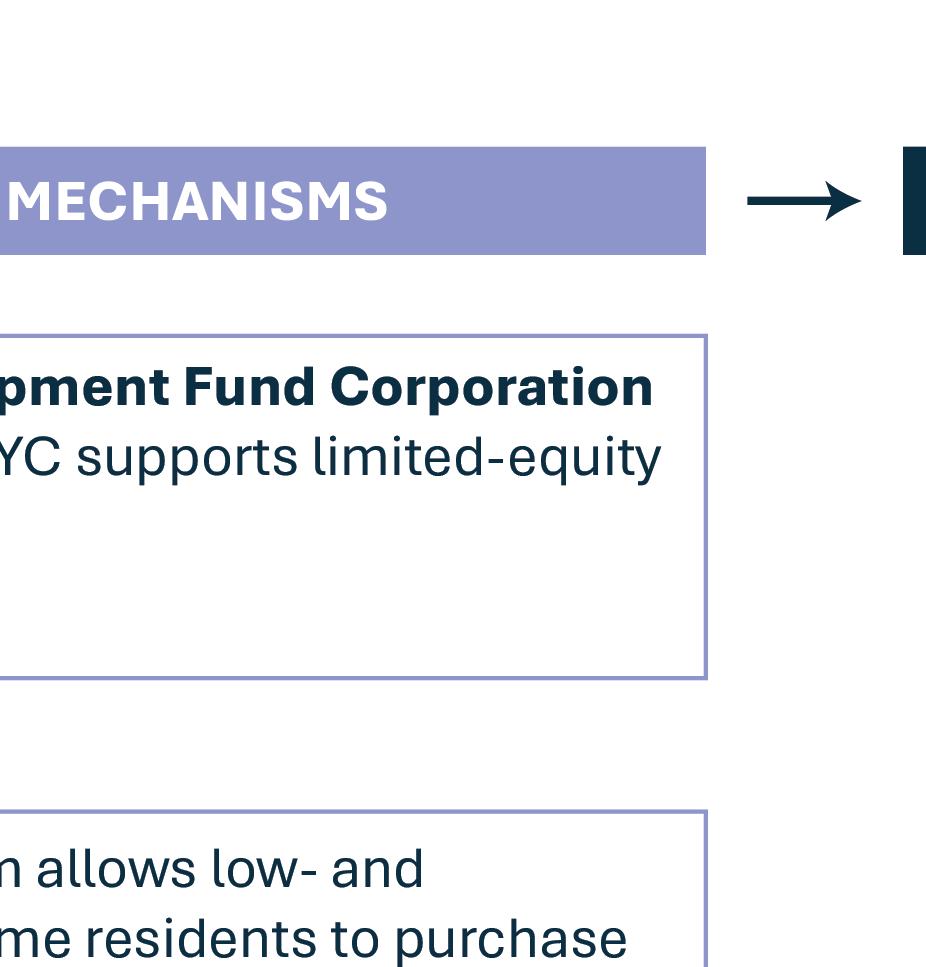

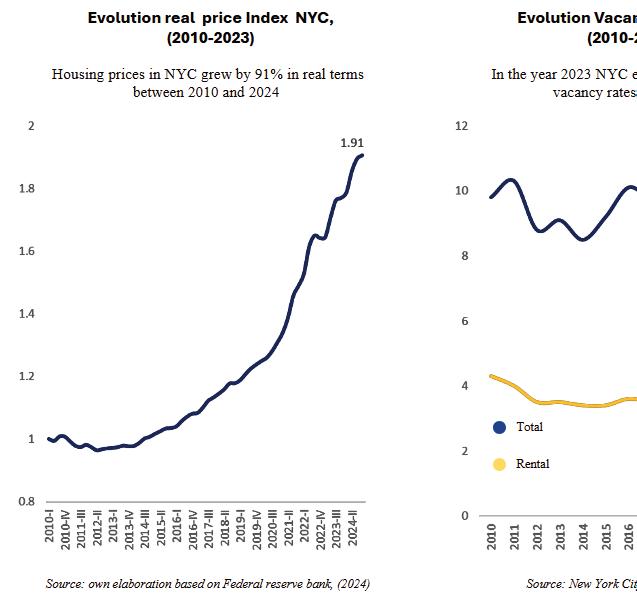

• Democratic oversight: Warsaw’s development review process empowers technical experts rather than elected officials in early stages, depoliticizing decisions while maintaining appropriate oversight. This approach has enabled Warsaw to increase its housing stock by 21% (2010-2019) compared to NYC’s 6%.

• Interagency collaboration: Santiago’s “one-stop-shop” permitting system coordinates between agencies centrally rather than requiring developers to navigate multiple bureaucracies independently, enabling the city to permit over 100,000 new housing units annually.

• Environmental review reform: Denmark’s interactive and tiered Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) model coupled with its quick screening process provides

developers with clear, predictable requirements and chance for proactive proposal alterations before they invest significantly in a project, reducing the risks and uncertainty that discourages development through NYC’s City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) process.

• Create an interactive public dashboard for tracking and providing community input on development proposals at multiple stages of the ULURP development process, increasing transparency and early community engagement.

• De-politicize the review process by empowering City Planning Commission for initial reviews and reducing political veto points.

• Incorporate a collaborative, tiered-screening process within the CEQR for the city to work with and establish expectations for developers before they commit resources.

• Allow third-party certification for certain reviews to address staff shortages.

• Develop a centralized coordination mechanism for developers to interface with multiple agencies simultaneously.

These reforms would preserve community input while streamlining processes, shortening development timelines, reducing risks and uncertainties for developers, and balancing local concerns with citywide housing needs — ultimately enabling New York to address its housing crisis more effectively.

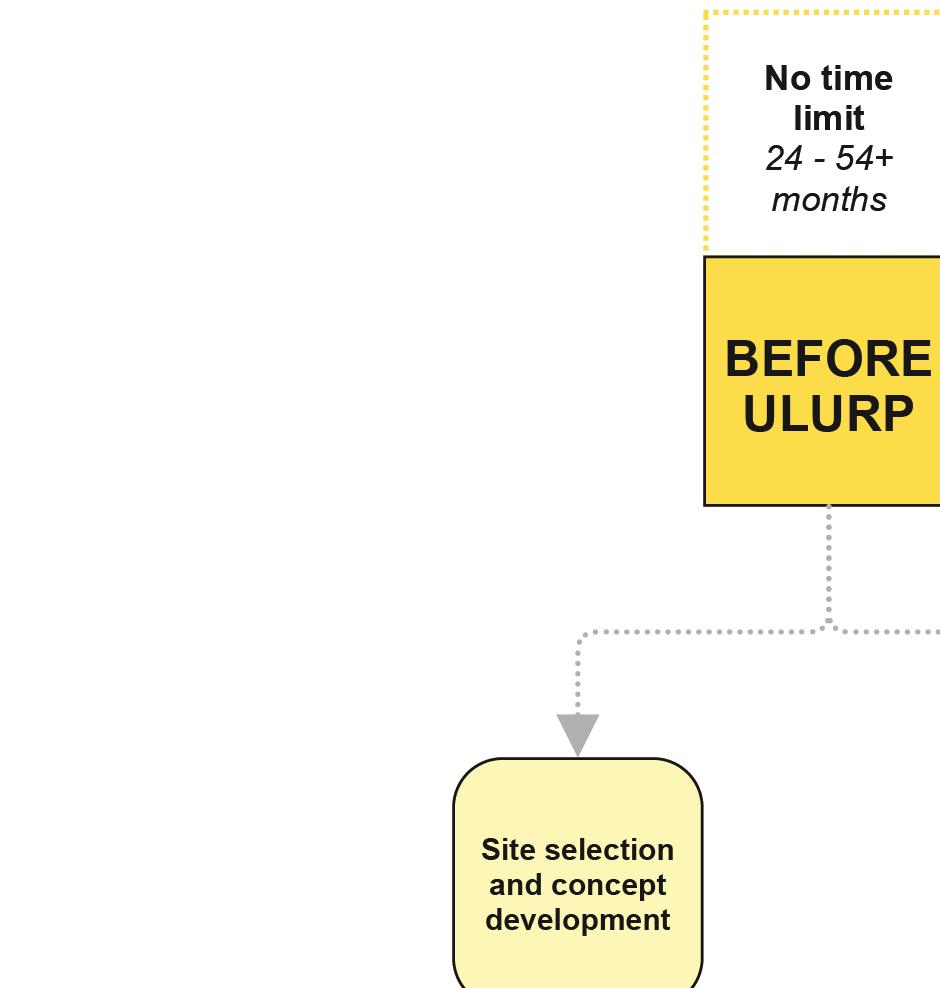

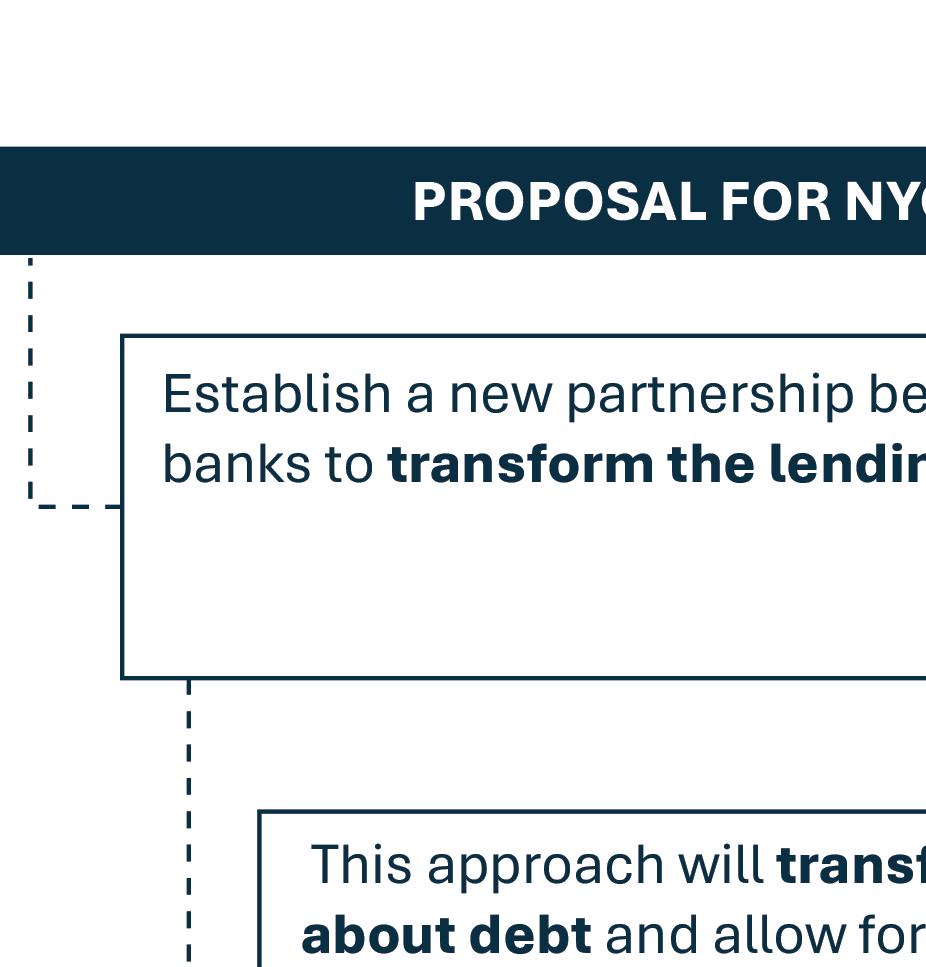

Responding to Urban Design Forum’s Big Swings research on cutting red tape, our research focuses on procedural barriers inherent to the housing development process in the context of NYC, particularly those that are required to go through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). As such, we identified the pre-development stages of a development proposal’s timeline, leading up to ULURP — the only process by which zoning regulations can be altered in NYC — as a key barrier despite ULURP’s well-meaning intentions of ensuring predictable, land-use review with broad participation from members of the public and various decision-makers in the city.

We began our research process by zooming in on ULURP as an institution in New York and identifying which aspects were most harmful to the development process of building easier and faster. These are governmental functions that are highly desirable in a democratic society – citizen input, democratic oversight, environmental protection and collaboration between different branches of governments – but which NYC does in an unjustifiably inefficient way.

For each of these areas for reform in the development process, we then selected an international jurisdiction from across the world that

represents an alternative way of meeting similar intended outcomes, but that could have more potential for success at keeping up production with the acute demands for housing in the city.

Although these places are all quite different, they showcase aspirational models for how NYC could cut red tape in various ways while keeping true to the democratic values about communities having a say in land used decisions. This inspired the creation of the ULURP system in the 1970s, as a reaction to the societal harm and injustice caused by urban renewal projects.

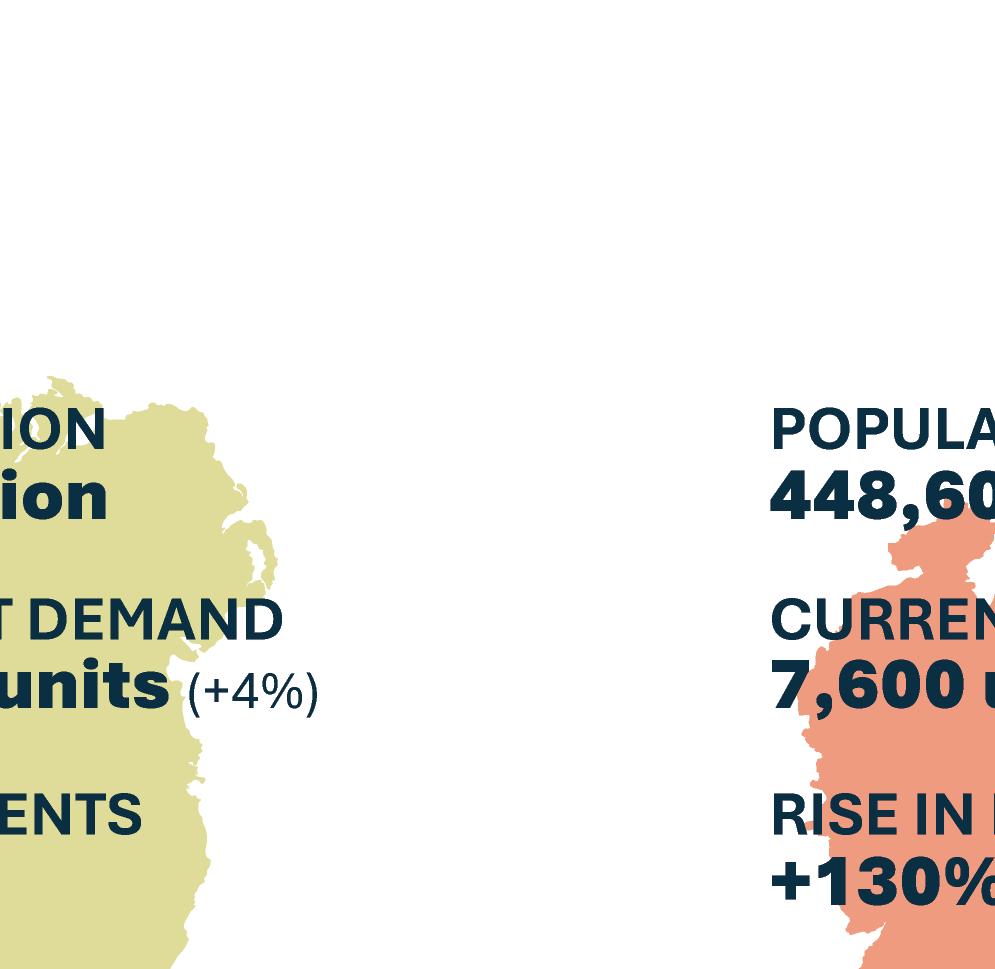

1. Bandung / Jakarta, Indonesia:Digital/online civic engagement in cities such as Bandung and Jakarta;

2. Warsaw, Poland:Politicians who say “yes” more than “no” in Warsaw, Poland;

3. Denmark:Collaborative and faster environmental reviews with a tiered screening process;

4. Santiago, Chile:One-stop-shop permitting and coordination in Santiago de Chile.

Our research began following the important

question posed by UDF fellows: How do we remove red tape across the full life cycle of a project to increase housing production? The fellows’ two major themes of inquiry and research included civil service reform (1) through the case of Kazakhstan in response to bureaucratic inefficiencies related to hurdles with hiring and retaining government officials; and (2) through the case of Tokyo toward the streamlining of design and construction regulations that stifle housing development.

As we further acquainted ourselves with existing and emerging research literature in the field, we noted there’s already a significant focus on building design and construction regulation reform. Furthermore, instead of replicating the important research of civil service reform produced by the UDF fellows, we decided to direct the framing of our inquiry toward the intersection of land use, zoning, and review processes inherent to housing development in NYC. On that note, ULURP emerged as a highly significant object of study given their relevance to high-impact housing projects not-fully addressed by the positive, yet more incremental strides made by NYC Department of City Planning’s City of Yes for Housing Opportunity plan (figure 1), solidifying our attention to procedural reform. Thus, we asked: How do we remove procedural red

tapes in the full development process to increase housing production?

Procedural reform is a timely topic considering the ongoing City Charter Revision process, launched by Mayor Adams in December 2024 to focus primarily on issues of housing and land use in NYC. The Revision process is in a critical stage at the time of writing. The Charter Revision Commission released their preliminary report on April 30, 2025, of which ULURP reform is a central theme. Public comments are ongoing; this memo could potentially be submitted as written testimony for consideration.

In addition, NYC is in the midst of a hotly contested mayoral election campaign in which issues of housing affordability and land use are hot button issues. Such debates can be informed by providing case studies of how other cities around the world manage their land use regulations, in a way that considers citizen voices, without deterring much needed housing development.

As part of our research methodology, we analyzed housing development timelines to identify points of the highest negative impact on developers and their ability to pursue their housing development proposal toward final implementation/construction.

Once these barriers were identified, considering potential to extend costs in terms of time, finance, uncertainties, and legal hurdles for developers reviewing emerging, rigorous research and testimonies on the topic of ULURP reform from institutions such as the NYU Furman Center (Been 2025) and Citizens Budget Commission NY (CBCNY 2022). To build on this momentum of dedicated research, we identified four respective international references for how the intended goals of specific procedures/barriers we identified in NYC were being addressed through different approaches. In other words, we began with a detailed diagnosis of problem points introduced by ULURP and looking at international alternatives. The goal was to ideally find places where alternative approaches had led to demonstrably better outcomes in terms of housing supply and affordability.

In an ideal world, this approach would yield a true counterfactual for New York, a city subject to the same pressures and policy environment

save for one small institutional detail which would allow us to showcase the effect of changing a single aspect of the ULURP process. Of course, however, no two cities are the same and the case study framework must consider each place’s unique history, housing model(s), economic environment and political culture. Beside basing our search on stages within the ULURP process, we also sought to include housing processes from a wide variety of geographies, especially those far from the major Western European capitals often employed as case studies in urban policy.

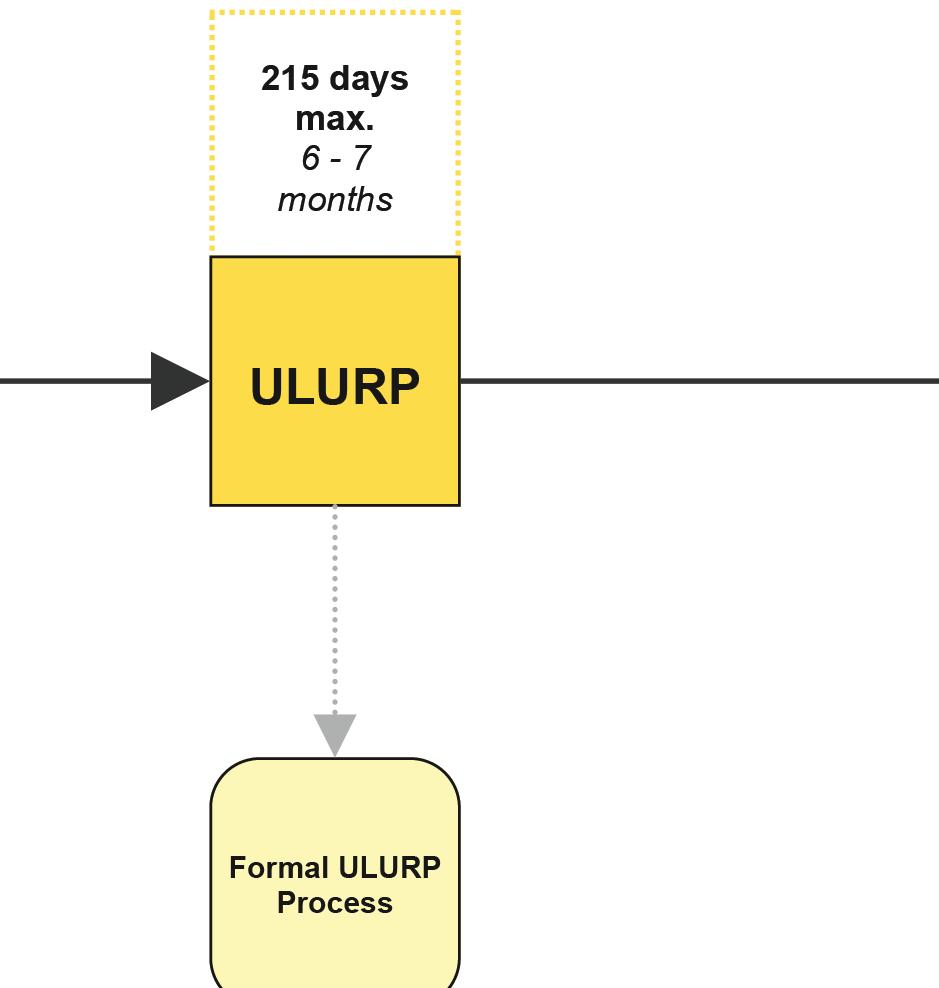

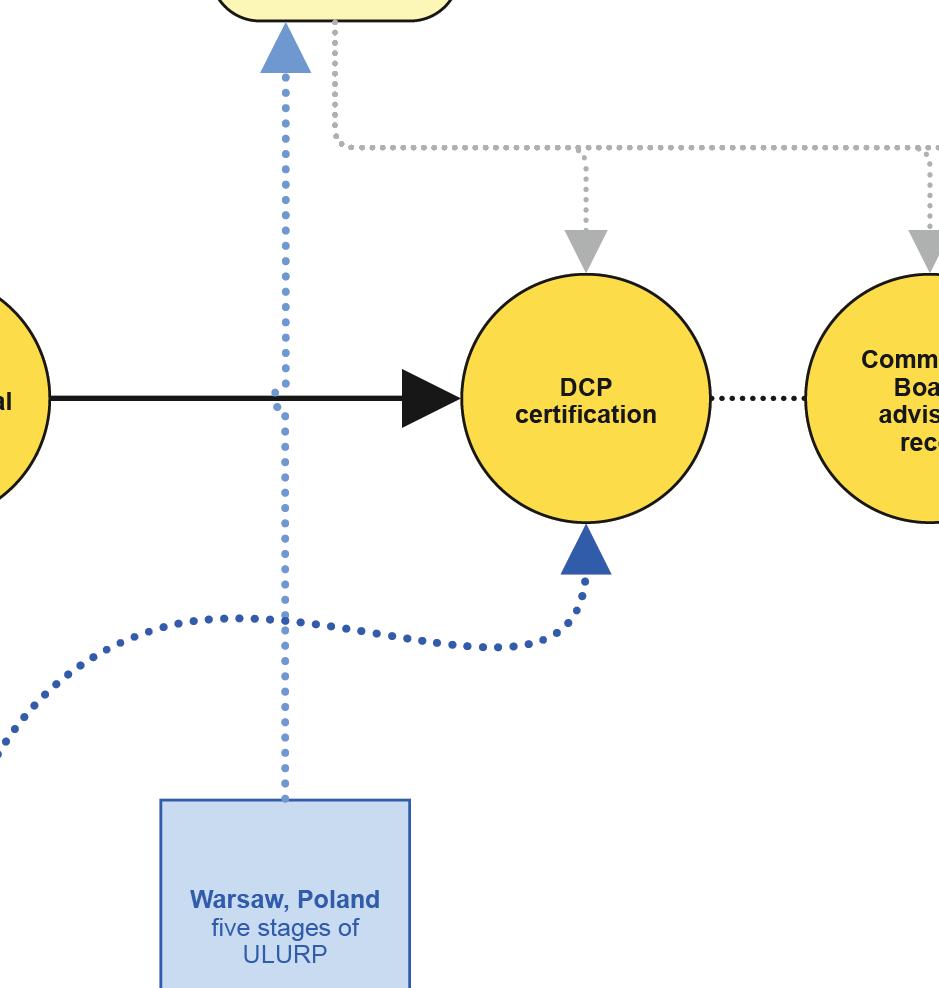

We combined official documentation of the ULURP process with a review of the literature on both de jure and de facto choke points to create a diagrammatic representation of the existing system for zoning changes from the point of view of a housing developer, from project conception through to the construction stage (Figure 2).

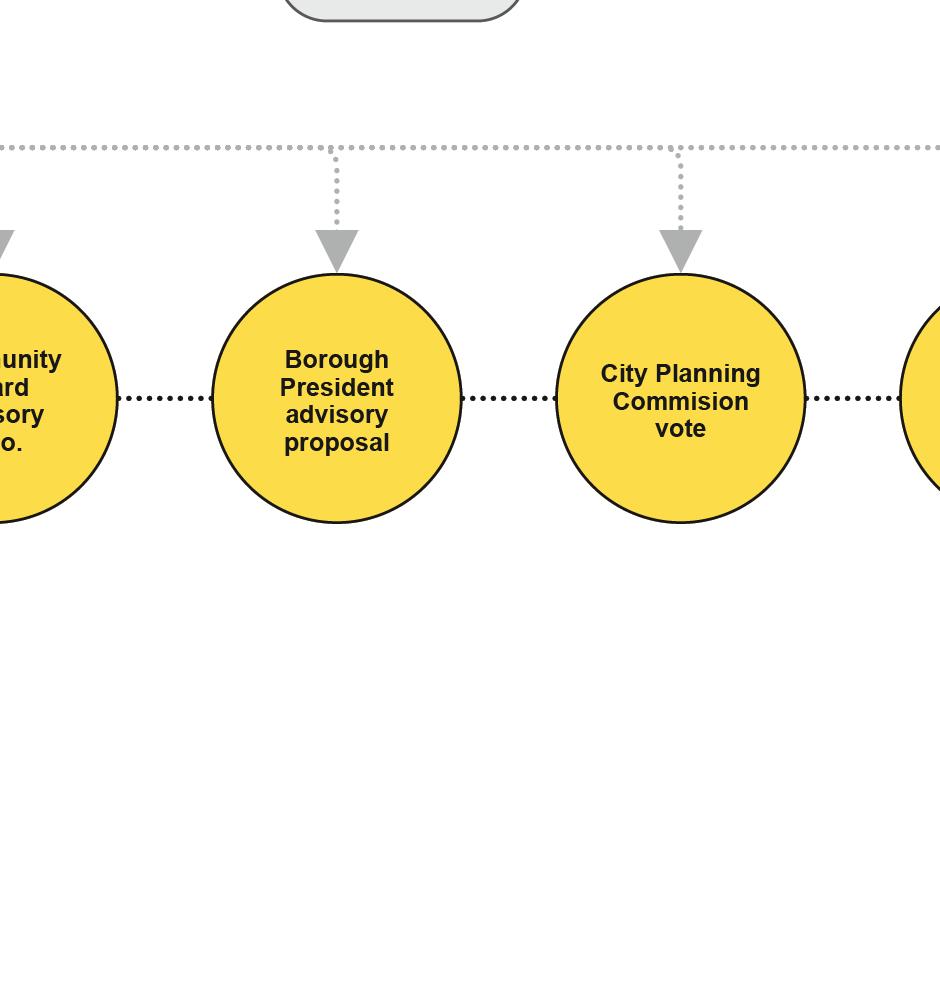

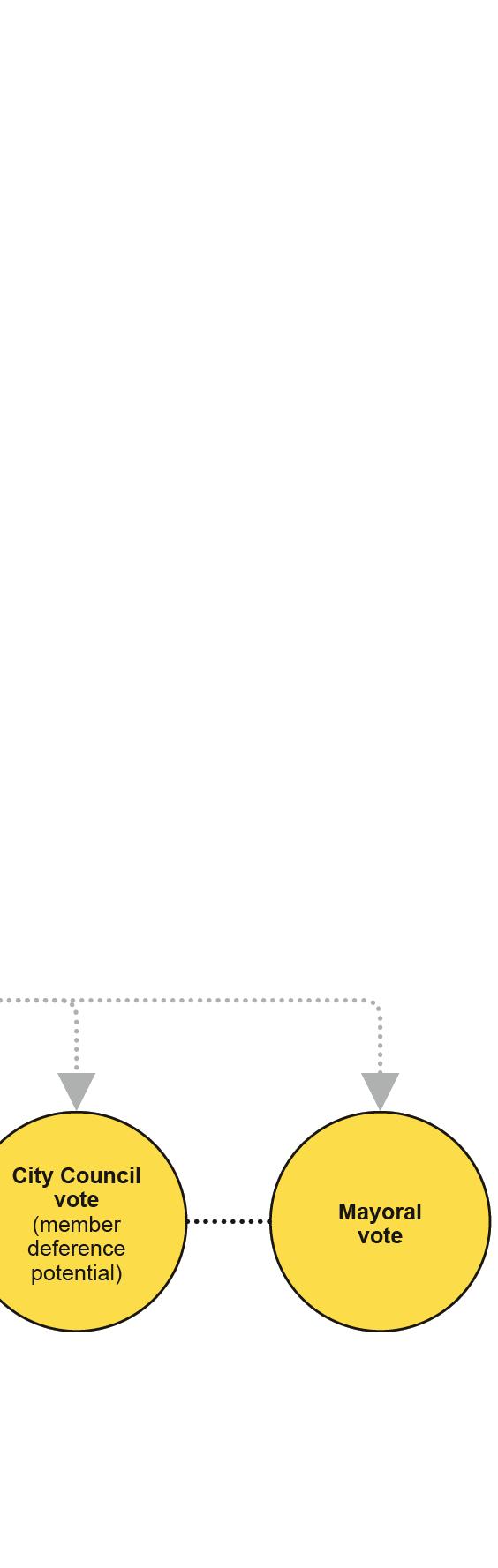

Based on this diagram, we identified four aspects of the ULURP process that are necessary functions to deliberate land use decision making in any city, but have become bottlenecks for increased housing supply in NYC:

1. Community engagement: This is the process by which existing residents of the city, especially communities that will be differentially impacted by changes in land use, in order to comment on and shape development proposals.

2. Democratic oversight: Where do elected representatives get a voice in the process? How should the preferences of different stakeholders be incorporated? How to institutionally balance the will of the local area vs. that of the city, state, metropolitan area or even country as a whole? In the existing ULURP process, there are five sequential reviews from various political bodies before the land use change is verified, for a statutory seven-month process: the Community Board (nominated by Borough Presidents and local City Councilmembers), the Borough President, the City Planning Commission (a panel nominated by the Mayor, all five Borough Presidents and the Public Advocate), the City Council and, finally, the Mayor.