Jog Raj*, Hunor Farkaš, Svetlana Ćujić, Zdenka Jakovčević and Marko Vasiljević PATENT CO. DOO., Vlade Cetkovica 1A, 24 211 Mišicevo, Serbia

*jog.raj@patent-co.com

Jog Raj*, Hunor Farkaš, Svetlana Ćujić, Zdenka Jakovčević and Marko Vasiljević PATENT CO. DOO., Vlade Cetkovica 1A, 24 211 Mišicevo, Serbia

*jog.raj@patent-co.com

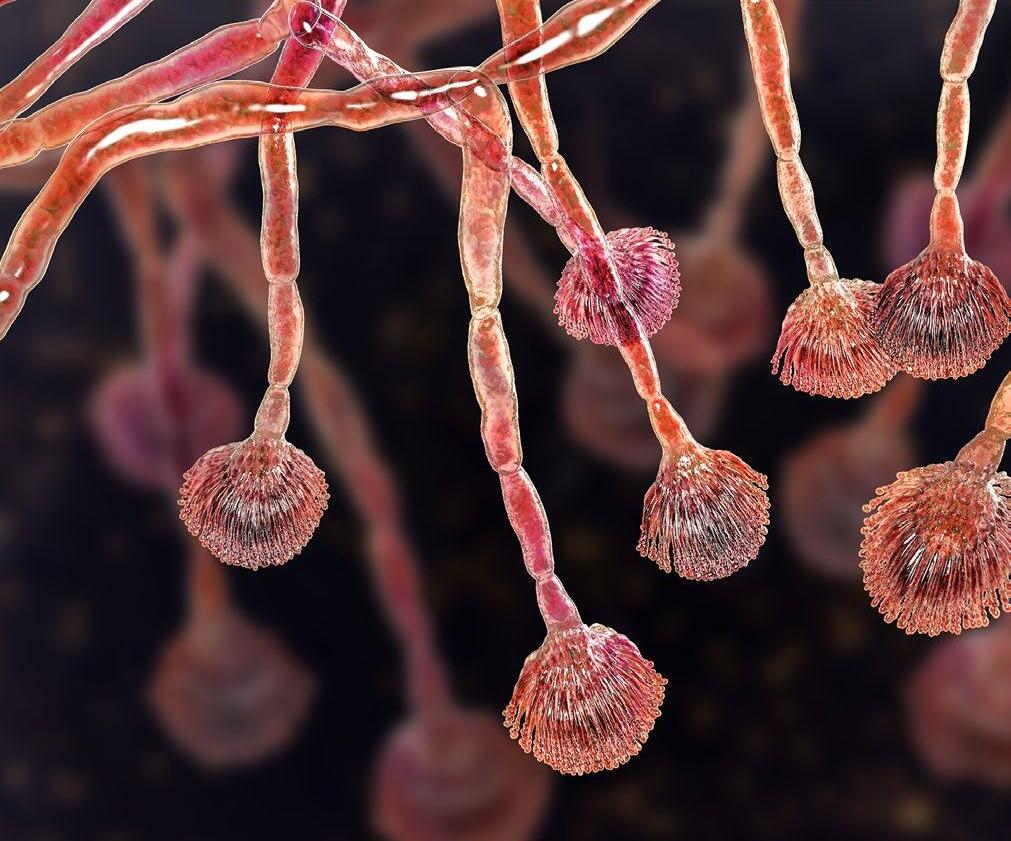

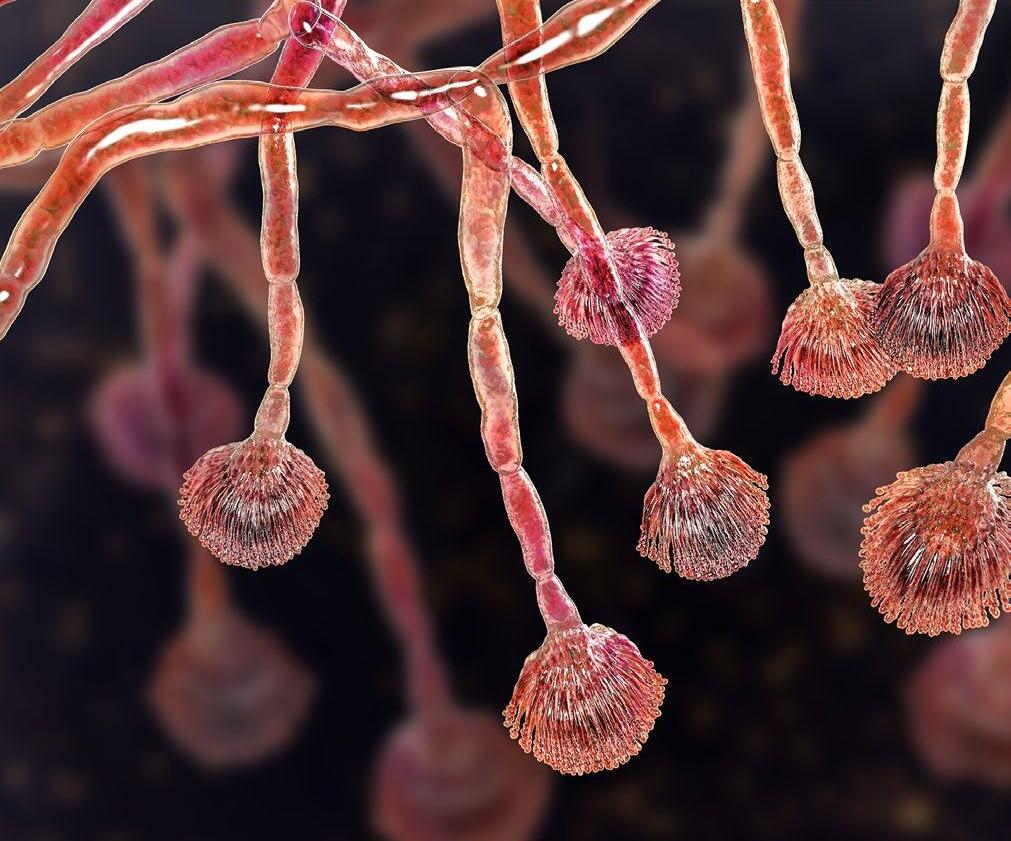

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by fungal species on food and feed materials. Most of them are produced by Aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium spp.

Commonly, people think of the six main mycotoxins that contaminate feed:

Aflatoxins (AF)

Deoxynivalenol (DON)

T-2 toxin

Fumonisins (FUM)

Ochratoxin A (OTA)

Zearalenone (ZEN)

A recent corn survey conducted by PATENT CO. DOO Mišićevo, Serbia, in 2024 also demonstrated a higher occurrence of emerging mycotoxins in corn.

However, testing and reporting on the prevalence of mycotoxins in feed have increased awareness about emerging mycotoxins, such as fusaric acid (FA), enniatins (ENNs), beauvericin (BEA) and monilformin (MON), which are also commonly produced by various Fusarium molds.

Enniatins (ENNs): Fusaric acid (FA)

Read the survey: Higher prevalence and co-occurrence of aflatoxins, fumonisins, and emerging mycotoxins in 2024-harvested corn from 18 countries

The structures of emerging mycotoxins are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of emerging mycotoxins produced by Fusarium spp.: fusaric acid (FA), enniatins (ENNs), beauvericin (BEA), and moniliformin (MON). The table shows the chemical side chains (R1, R2, R3) for the main enniatin analogs (A, A1, B, B1).

(BEA) Moniliformin (MON)

Enniatins (ENNs): Fusaric acid (FA)

Enniatins (ENNs): Fusaric acid (FA)

(BEA) Moniliformin (MON)

Beauvericin (BEA) Moniliformin (MON)

1: Efficacy of MYCORAID against emerging mycotoxins

Figure 1: Efficacy of MYCORAID against emerging mycotoxins

MYCORAID is a premium mycotoxin remediation product developed by PATENT CO. for the bioremediation of polar and less polar mycotoxins.

In this study, MYCORAID was tested at pH 3.0 for adsorption and pH 6.5 for desorption with emerging mycotoxins.

A total of 100 mg of the mycotoxin remediation product was weighed into duplicate 15 mL Falcon tubes.

10 mL of 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 3.0) containing 2 ppm of BEA, ENN A, ENN A1, ENN B, ENN B1, FA, and MON was pipetted into each tube.

A control sample was prepared to measure non-specific binding and eliminate exogenous peaks.

The tubes were placed on an orbital shaker at 37 °C for 30 minutes and, after incubation, all samples (test and control) were centrifuged at 4,200 rpm for 5 minutes.

100 μL of supernatant was transferred to a glass vial and mixed with 900 μL of dilution solvent (50 % acetonitrile:50 % water with 0.1 % formic acid).

An aliquot of the pH 3.0 buffered mycotoxin solution was used as the standard for each mycotoxin.

All samples and controls were analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

The supernatant was removed from the remaining test and control Falcon tubes, and the mycotoxin remediation product pellet was resuspended in 4 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.5).

The tubes were shaken again, and the samples were prepared following the same procedure described above.

These samples and controls were also analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

The overall efficacy of the remediation product was calculated based on the adsorption and desorption data.

The overall efficacy against emerging mycotoxins is shown in Figure 2.

The results show that MYCORAID effectively removed over 97 % of ENNs and FA, 89 % of BEA, and 56 % of MON.

Due to the limited information on the toxicity and prevalence of emerging mycotoxins, it is difficult to fully assess their impact on animal health and performance.

However, these emerging mycotoxins are likely to co-occur with major mycotoxins that contaminate grains used in livestock production.

Implementing an effective remediation strategy is essential to reduce the carryover of mycotoxins from animals to humans.

Gruber-Dorninger, C. et al. (2017). Emerging mycotoxins: beyond traditionally determined food contaminants. J Agri Food chem, 65: 7052-7070.

Ekwomadu, T.I. et al. (2020). Variation of Fusarium free, masked, and emerging mycotoxin metabolites in maize form agriculture regions of south Africa, Toxins, 12(149); doi:10.3390/toxins12030149.

Jestoi, Marika (2008). Emerging Fusarium mycotoxins fusaproliferin, beauvericin, enniatins, and moniliformin – a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 48:1, 21-49.

https://www.porkbusiness.com/article/continue testing-mycotoxins, accessed Sept. 28, 2020. https://mycotoxinsite.com/higher-prevalence-and-co-occurrence-of-aflatoxins-fumonisinsand-emerging-mycotoxins-in-2024-harvested-corn-from-18-countries/?lang=en

Ramos, A.J., J. Fink-Gremmels, and E. Hernández. (1996). Prevention of toxic effects of mycotoxins by means of nonnutritive mycotoxin remediation product compounds. J. Food Protection, 59(6):631-641.