Respiratory Medicine | Volume 6 | Issue 9 | 2020

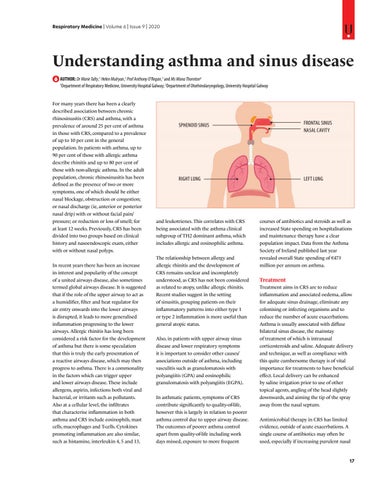

Understanding asthma and sinus disease AUTHOR: Dr Marie Talty,1 Helen Mulryan,1 Prof Anthony O’Regan,1 and Ms Mona Thornton2 1 Department of Respiratory Medicine, University Hospital Galway; 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University Hospital Galway For many years there has been a clearly described association between chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and asthma, with a prevalence of around 25 per cent of asthma in those with CRS, compared to a prevalence of up to 10 per cent in the general population. In patients with asthma, up to 90 per cent of those with allergic asthma describe rhinitis and up to 80 per cent of those with non-allergic asthma. In the adult population, chronic rhinosinusitis has been defined as the presence of two or more symptoms, one of which should be either nasal blockage, obstruction or congestion; or nasal discharge (ie, anterior or posterior nasal drip) with or without facial pain/ pressure; or reduction or loss of smell; for at least 12 weeks. Previously, CRS has been divided into two groups based on clinical history and nasoendoscopic exam, either with or without nasal polyps. In recent years there has been an increase in interest and popularity of the concept of a united airways disease, also sometimes termed global airways disease. It is suggested that if the role of the upper airway to act as a humidifier, filter and heat regulator for air entry onwards into the lower airways is disrupted, it leads to more generalised inflammation progressing to the lower airways. Allergic rhinitis has long been considered a risk factor for the development of asthma but there is some speculation that this is truly the early presentation of a reactive airways disease, which may then progress to asthma. There is a commonality in the factors which can trigger upper and lower airways disease. These include allergens, aspirin, infections both viral and bacterial, or irritants such as pollutants. Also at a cellular level, the infiltrates that characterise inflammation in both asthma and CRS include eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages and T-cells. Cytokines promoting inflammation are also similar, such as histamine, interleukin 4, 5 and 13,

SPHENOID SINUS

FRONTAL SINUS NASAL CAVITY

RIGHT LUNG

LEFT LUNG

and leukotrienes. This correlates with CRS being associated with the asthma clinical subgroup of TH2 dominant asthma, which includes allergic and eosinophilic asthma. The relationship between allergy and allergic rhinitis and the development of CRS remains unclear and incompletely understood, as CRS has not been considered as related to atopy, unlike allergic rhinitis. Recent studies suggest in the setting of sinusitis, grouping patients on their inflammatory patterns into either type 1 or type 2 inflammation is more useful than general atopic status. Also, in patients with upper airway sinus disease and lower respiratory symptoms it is important to consider other causes/ associations outside of asthma, including vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). In asthmatic patients, symptoms of CRS contribute significantly to quality-of-life, however this is largely in relation to poorer asthma control due to upper airway disease. The outcomes of poorer asthma control apart from quality-of-life including work days missed, exposure to more frequent

courses of antibiotics and steroids as well as increased State spending on hospitalisations and maintenance therapy have a clear population impact. Data from the Asthma Society of Ireland published last year revealed overall State spending of â‚Ź473 million per annum on asthma.

Treatment Treatment aims in CRS are to reduce inflammation and associated oedema, allow for adequate sinus drainage, eliminate any colonising or infecting organisms and to reduce the number of acute exacerbations. Asthma is usually associated with diffuse bilateral sinus disease, the mainstay of treatment of which is intranasal corticosteroids and saline. Adequate delivery and technique, as well as compliance with this quite cumbersome therapy is of vital importance for treatments to have beneficial effect. Local delivery can be enhanced by saline irrigation prior to use of other topical agents, angling of the head slightly downwards, and aiming the tip of the spray away from the nasal septum. Antimicrobial therapy in CRS has limited evidence, outside of acute exacerbations. A single course of antibiotics may often be used, especially if increasing purulent nasal

17