RITUAL AS RENEWAL: THE SCHRÖDER RITUAL AND ARMINIUS LODGE By Andrew U. Hammer, PM Deputy Grand Lecturer

WB Andrew Hammer

O

ne of the blessings of our Grand Lodge is its ritual and cultural diversity, which although it might be argued arose more out of necessity than foresight, has given us a profile that is unique in the United States. It has also given us multiple ways to understand the Craft, and to educate ourselves about how Freemasonry works around the world. Arminius Lodge No. 25 is the oldest nonEnglish language lodge in our jurisdiction, chartered in 1876 to serve the needs of German-speaking immigrants who either already were Masons, or wanted to be. At the time, German-speaking immigrants were in abundance in many of America’s cities, and such a lodge, while not exactly embraced from the start, could surely be justified as beneficial to the fraternity. Over the years, as the children of those immigrants became native-born Americans with English as their first language, the bond of German language and culture on

32 | THE VOICE OF FREEMASONRY ISSUE 3, 2020

the generations to follow would naturally wane. The unfortunate political events of the 20th century did not help to strengthen them, and it could be said even placed such bonds at a higher disadvantage than those of other ethnic cultures. In the case of Arminius Lodge, however, enough German-speaking brethren were able to sustain the vibrancy of the lodge, working the Preston-Webb ritual of our Grand Lodge in German, and conferring the degrees on worthy candidates all the way up to the present day. Brethren with enduring connections to their German families, military veterans with German brides or other associations to Germany resulting from their postings after the Second World War, made sure that Arminius had a steady flow of men who, upon their arrival in the DC metro area, could keep the lodge true to its mission as a German lodge in America. The 21st century finds the lodge in an interesting position, as the number of German speakers in our area has decreased as it has elsewhere in America, and the number of those German speakers who might be interested in Masonry is exponentially less still. Arminius has found itself at a crossroads, and in the past two years, much discussion has taken place on how it might take a path which could, if carefully developed, not only revive the lodge, but make it a focal point of interest for brothers throughout the nation, as well as Masonic scholars. I became a member of Arminius in 2018. Upon joining, I made the suggestion to a few brothers that one way to enhance the German element of the lodge would be to study and even explore an exemplification of the Schröder ritual, not in German,

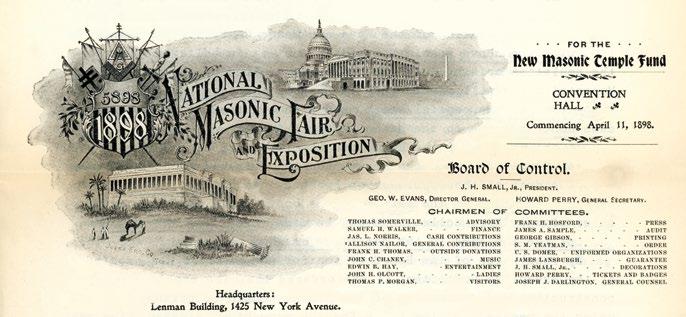

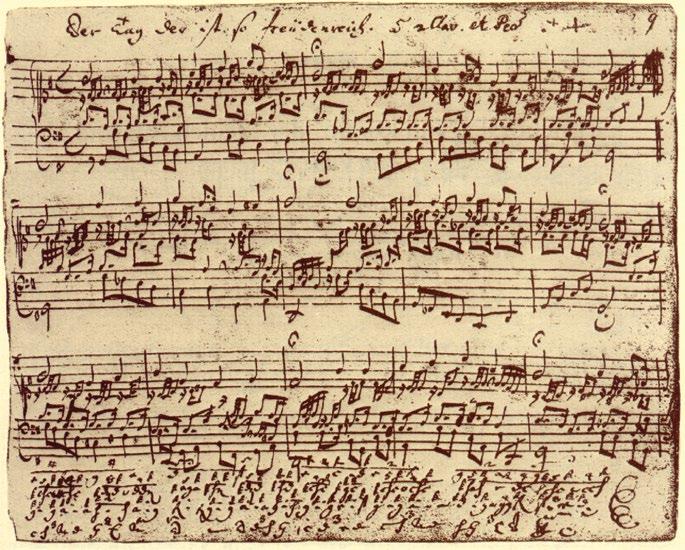

but in English. At the moment, the lodge opens and closes in German, and conducts its business in English. When degree work is done, it is also done in German. This provides a great opportunity for any visiting German or German-speaking Masons to see something they might not see elsewhere (i.e. the Preston-Webb work in German), but on the other hand, it may not attract too many other visitors to the lodge if the work is only in a language they do not understand. Adding the study of the Schröder ritual to the work of the lodge provides Arminius the chance to not only work in the German language, but to learn about German Masonry itself, as well as enhance its understanding of German Masonic culture. And, although one doesn’t usually think in such terms when talking about Masonry, it could also offer an interesting marketing point both for our Grand Lodge and the lodge itself, as being yet another place in our jurisdiction where interested brethren from here and abroad can come to learn about the universality of our brotherhood. So what is the Schröder ritual? The story of this ritual begins in the Masonic chaos of Germany in the late 1700s. At this time, in the German states as well as throughout the rest of Europe, Freemasonry had evolved in a way that found brethren engaged in any number of side degrees and orders, both legitimate and illegitimate, depending on how one viewed their respective interests. This was creating quite a bit of confusion in the Craft, and men who saw Masonry as a quasi-political movement were also involved in these developments. For those who desired an approach to the fraternity that was, shall we say, closer to the place whence it came, there was a feeling that they should