8 minute read

Ritual as Renewal: The Schröder Ritual and Arminius Lodge

By Andrew U. Hammer, PM Deputy Grand Lecturer

WB Andrew Hammer

Advertisement

One of the blessings of our Grand Lodge is its ritual and cultural diversity, which although it might be argued arose more out of necessity than foresight, has given us a profile that is unique in the United States. It has also given us multiple ways to understand the Craft, and to educate ourselves about how Freemasonry works around the world.

Arminius Lodge No. 25 is the oldest nonEnglish language lodge in our jurisdiction, chartered in 1876 to serve the needs of German-speaking immigrants who either already were Masons, or wanted to be. At the time, German-speaking immigrants were in abundance in many of America’s cities, and such a lodge, while not exactly embraced from the start, could surely be justified as beneficial to the fraternity.

Over the years, as the children of those immigrants became native-born Americans with English as their first language, the bond of German language and culture on the generations to follow would naturally wane. The unfortunate political events of the 20th century did not help to strengthen them, and it could be said even placed such bonds at a higher disadvantage than those of other ethnic cultures.

In the case of Arminius Lodge, however, enough German-speaking brethren were able to sustain the vibrancy of the lodge, working the Preston-Webb ritual of our Grand Lodge in German, and conferring the degrees on worthy candidates all the way up to the present day. Brethren with enduring connections to their German families, military veterans with German brides or other associations to Germany resulting from their postings after the Second World War, made sure that Arminius had a steady flow of men who, upon their arrival in the DC metro area, could keep the lodge true to its mission as a German lodge in America.

The 21st century finds the lodge in an interesting position, as the number of German speakers in our area has decreased as it has elsewhere in America, and the number of those German speakers who might be interested in Masonry is exponentially less still. Arminius has found itself at a crossroads, and in the past two years, much discussion has taken place on how it might take a path which could, if carefully developed, not only revive the lodge, but make it a focal point of interest for brothers throughout the nation, as well as Masonic scholars.

I became a member of Arminius in 2018. Upon joining, I made the suggestion to a few brothers that one way to enhance the German element of the lodge would be to study and even explore an exemplification of the Schröder ritual, not in German, but in English. At the moment, the lodge opens and closes in German, and conducts its business in English. When degree work is done, it is also done in German. This provides a great opportunity for any visiting German or German-speaking Masons to see something they might not see elsewhere (i.e. the Preston-Webb work in German), but on the other hand, it may not attract too many other visitors to the lodge if the work is only in a language they do not understand.

Adding the study of the Schröder ritual to the work of the lodge provides Arminius the chance to not only work in the German language, but to learn about German Masonry itself, as well as enhance its understanding of German Masonic culture. And, although one doesn’t usually think in such terms when talking about Masonry, it could also offer an interesting marketing point both for our Grand Lodge and the lodge itself, as being yet another place in our jurisdiction where interested brethren from here and abroad can come to learn about the universality of our brotherhood.

So what is the Schröder ritual? The story of this ritual begins in the Masonic chaos of Germany in the late 1700s. At this time, in the German states as well as throughout the rest of Europe, Freemasonry had evolved in a way that found brethren engaged in any number of side degrees and orders, both legitimate and illegitimate, depending on how one viewed their respective interests. This was creating quite a bit of confusion in the Craft, and men who saw Masonry as a quasi-political movement were also involved in these developments. For those who desired an approach to the fraternity that was, shall we say, closer to the place whence it came, there was a feeling that they should

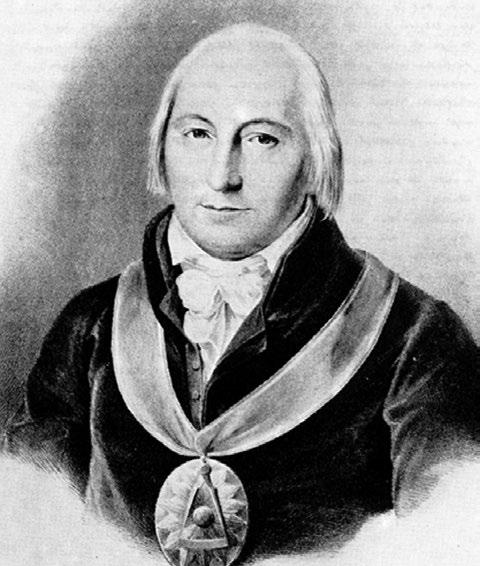

find a way to get back to what some felt were its roots. Enter Frederick Ludwig Schröder, whose role in German Masonry could be considered akin to that of William Preston in English-speaking Masonry.

Schröder was an actor and playwright, born in Schwerin in 1744 to a mother who was also an actress. He had a fascination with Shakespeare, and would eventually become one of the most prominent dramatists of the era. He would have the privilege of working with both Mozart and Goethe during his life. His interest in Masonry developed just at the time when the aforementioned disputes amongst German Masons were reaching a fever pitch.

Initiated in Hamburg in 1774 at Loge Emanuel zum Maienblume, and raised the following year at Loge Josua zum Korallenbaum, he was an unusually eager Mason, and thirteen years later, after serving as Master of his mother lodge, he found himself at the forefront of a movement to re-establish Masonry in Germany on what he and others believed was a more sound, traditional footing. His knowledge of the English language made him the right man for the job.

This article will not touch upon the labyrinthine matter of the 1782 Convent of Wilhelmsbad and what resulted from it. Suffice it to say that regardless of how one might view the Rite of Strict Observance, the Bavarian Illuminati, or the Rectified Scottish Rite today, the fraternal factionalism of the late 1700s in Germany opened the door for Schröder and brothers who shared his views to embark on a course which would return the Craft to—what they felt was—its proper form.

After being appointed to an official reform commission in 1788, an initial report was presented by Schröder in 1789. Upon its adoption two years later, he then set about the work of drafting a restored ritual to German-speaking Masonry.

His position on the issue was the same that would be expressed by the Grand Lodge of Scotland and the UGLE (somewhat) only a few years later; that Masonry properly consisted of the three degrees of the symbolic lodge and did not need anything else. Schröder took hold of three English exposures as his inspiration: Masonry Dissected (1730), Three Distinct Knocks (1760), and Jachin and Boaz (1762). He translated Jachin and Boaz into German and worked from there.

Friedrich Ludwig Schröeder

What is interesting about Schröder’s work is that when one considers he sought to restore what he believed was proper English Masonry to Germany, the inclusion of certain elements in his work is most curious. The Schröder ritual explicitly includes the ‘Chamber of Reflection’ in the beginning of the ceremonies. The method of entry into the lodge room by the brethren is formal and individualized. One variation also specifies the passing of the candidate before the lodge prior to the degree, which is well-known in French Masonry to this day, but has all but disappeared from the dominant Englishspeaking forms of the work in the intervening centuries. Here, the candidate’s resolve to become a Mason is dramatically tested.

As for the logistical aspects of the lodge itself, just as is the case with other international lodges we know in our jurisdiction, the altar is placed closer to the East than in the centre. Pillars are arranged on the ‘carpet’ where our altars might be. As one might expect, music is an important part of this work, and singing is indicated at certain places, just as with our own DC Preston-Webb ritual. The modern application of this work, however, features two aspects that are not familiar in America; one of which is to be determined by the will of the brethren, and the other which would not likely be accepted even in our progressive Grand Jurisdiction. The brethren in lodges who use this ritual are attired in formal wear, namely white tie, to include top hats. They also read the ritual rather than commit it to memory. The latter is quite common in Europe, but almost unthinkable in English-speaking Masonry.

Reading the work is not our custom, and memory work is so valued by English-speaking Masonry, that in the event that Arminius Lodge finds itself in a position in the future where it would request permission to confer degrees using an English translation of the Schröder ritual, it is unthinkable to this writer that the brethren would not commit it to memory. The volume of the work is not such as to make that an unattainable goal, and neither the international nature of a lodge nor a different ritual working is a reason to excuse the memorization required of all lodges.

When writing about ritual, there is much in the way of specifics that cannot be written. But with so much information about the Craft readily available to brethren in this day and age, there is a strong interest in various forms and approaches to Freemasonry amongst new Masons. One can easily understand how a lodge with such an idiosyncratic history as Arminius might revitalize itself by exploring a ritual that could help it be an even more German lodge now than it might have been previously. Certainly, one expects it would attract a fair interest from the German-speaking Masonic world. A successful endeavor in that regard would only be another success for Masonry in the nation’s capital.