9 minute read

The Sixth Science: Music

By Walter P. Benesch, PM LaFayette-Dupont Lodge No. 19

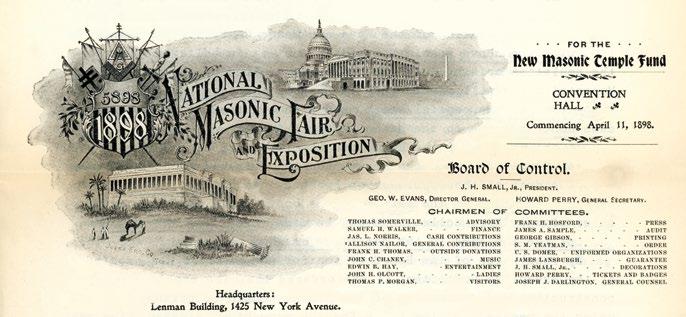

In the Fellowcraft Degree, a Mason is taught the importance of the seven liberal arts and sciences. Emphasis is placed on geometry with some attention on arithmetic and astronomy, but little attention on music. An exploration of the origins of Masonic adoption of the “arts and sciences,” and more importantly why considerable attention should be placed on music is the object of this article.

Advertisement

The likely origins of the concept of the arts and sciences is the Greek quadrivium. These were the four areas of study Plato proposed in The Republic. The areas were Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, and Music, in that order. The concept of the quadrivium is also found in the writings of Pythagoras and Aristotle, and later adopted by many philosophers in the Middle Ages.

In a review of these philosophers including documentation on the quadrivium, not enough attention is paid to music. In fact, music may be critical to the understanding of many of the other arts and sciences, in particular arithmetic, grammar, and rhetoric. To illustrate this idea, a look at the great minds who examined music will help us understand its importance and place in human history.

Pythagoras is associated with a legend (later proved false) where he discovered the idea of musical tuning listening to the sounds of blacksmith’s hammers, noticing both the consonance and dissonance when they were struck simultaneously. Although the story proved false, Pythagoras is still credited with establishing the concepts of dissonance and consonance, along with the ideas of harmony and ratio.

Xenocrates (4th century BCE), said: “Pythagoras discovered the intervals in music do not come into being apart from

An original score of Fantasy & Fugue in Beethovens hand

number; for they are an interrelation of quantity with quantity.” He set out to investigate under what conditions concordant intervals come about, and discordant ones, and everything wellattuned and ill-tuned.” This led to what is now known in Western music as the octave scale.

This historical evidence shows how music is related to arithmetic. Is it possibly linked to linguistic development which was a prerequisite to the development of grammar and rhetoric? If so, music would then be connected to three of the other six arts and sciences. Yet Pythagoras also considered the heavenly “music of the spheres” as part of the understanding of the workings of the universe and the movements of the planets, thus linking it to astronomy.

But Galileo and other astronomers of the Renaissance used arithmetic and geometry in the tracking of the stars and planets, as well as establishing the heliocentric theory for our solar system. Thus, directly or indirectly, music can be related to all the other arts and sciences as seen in history. But music itself went through its own unique stages of development.

Music in the Middle Ages began as monophonic chants. Then around 1000 AD, new types of polyphony developed and gradually expanded in rhythm, harmony, and texture until reaching an extremely complex style in the late 1300s. Unfortunately, a full assessment of Medieval music is difficult because the amount of musical source material that has survived from this era.

The Renaissance saw a revitalization of learning, commerce, exploration, scientific discovery, and spectacular artistic achievement as Renaissance artists and philosophers sought to reconcile theological practice with the new spirit of scientific inquiry. An important consequence of this new thinking was

the Protestant Reformation, which in turn had a tremendous impact on Renaissance music. While this religious rebellion was solidified in 1534 when King Henry VIII of England established his own Anglican church, in the larger process of reform, new churches gave rise to new types of sacred music, and with so much turmoil in the church scene, secular music began to rival its sacred counterpart.

This led to some of the most important revelations in composition, led by individuals such as: Josquin Desprez (Flanders, c. 1440-1521) who established a beautiful expressive sound with a constant changing of textures in his motets and songs. Giovanni da Palestrina (Italy, c. 1524 - 1594) who worked in the Vatican and is considered a master of sacred music, who developed counter-point. Thomas Weelkes (c. 1575-1623) and Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585) two of England’s great composers, both advanced the various styles of music, but were also instrumental (pun intended) in the patenting and publishing of music with the help of William Byrd (see Lumen). This transformed the printed forms of musical scores from the handwritten sheets of early music, into a slightly more recognizable form.

Following the Renaissance, the Baroque era of music is probably more

Giovanni Palestrina and Pope Julius III recognizable to modern ears, and was followed by the Classical and Romantic eras, where we get most of what we know now as “classical music.”

But what is the value of music beyond the enjoyment from listening to it? As a former social worker with a specialty in early childhood development, I promoted the idea of having classical, particularly Bach and Mozart, be played to infants. This advice was based on research developed in the 1990’s that suggested that the regular patterns found in that music emulate the basic structure of mathematics, which are then ingrained into the developing brain. Further cognitive research found that young test subjects performed better on spatial-temporal tasks when exposed to a Mozart sonata. Such temporal reasoning would aid in the development of mathematical capabilities later in life.

As music advanced, science took more notice of its importance. Charles Darwin wondered if our love of music might have ancient roots with other apes. He tested his idea with an orangutan in the London Zoo, but with no definitive results. In his book The Descent of Man, Darwin looked at the musical cadences in various species of animals and birds to attract females. He noted spiders can be attracted by music (Chapter IX & XIX), and wondered if this carried over into human courtship ceremonies? He also wondered if the development of common speech was enhanced by cadences and rhythms (Chapter XIX), which may have been the basis for the development of language in our ancestors.

But modern science has carried this much further. Some remarkable studies have shown that music has a much greater positive impact on humans than realized before the turn of this century. In neonatal intensive care units, those which have music playing in the background helped the infants sleep better. This lowered stress level allowed for a 30% increase in growth, compared to the control group. The growth was seen in both the physical body AND in brain development. The music-exposed infants were released before similar infants who were not exposed (control group) to the music in the hospital wards (see Patel, 2008, 2015).

It has been seen repeatedly that small infants respond to musical rhythms and will clap and move in time with the beats of the music being heard. As they grow, a child exposed to music training beginning before the age of seven will have a greater capability to learn and retain language (see Moreno, et. al.). The rhythm of the language becomes more ingrained in the plasticity of the brain which is developing during this period.

The effects seen in these studies are reflected in my personal experience, as well. My daughter was given violin lessons before her seventh birthday and was exposed to classical music before birth. Her linguistics, math, and scientific abilities greatly exceeded those of her peers. And I strongly feel it was this strong foundation which resulted in her eventually matriculating as a physician–a profession in which she practices today.

The benefits of music can also be seen in the many other ways associated with physical and mental therapies. Hip replacement surgery is a prime example. Playing relaxing music decreased the need for anesthesia by 15% for patients going into surgery. When the patient was exposed to the relaxing music, the amount of anesthesia needed was significantly lower than patients not exposed to music. The result was an improved rate of recovery and a lower risk associated with the use of anesthesia (see Justin). In stoke victims, those exposed to music in the third to sixth month of post stroke therapy have superior cognitive and mood measures, perhaps due to the decrease in stress. It appears music was also able to increase the sprouting of axons and dendrite branching on both sides of the brain. This is true for Alzheimer’s patients, as well, aiding in the recovery of their longterm memory. All this is based on actual studies (see Justin).

Melodic intonation therapy (MIT) has proved to be more effective than speech therapy in patients suffering from aphasia and stroke. Neural plasticity (see Herholz) is enhanced through use of music in the forms of songs. It facilitates the changing of the brain structure by increasing white matter structure in several regions. What is most remarkable about this is that patients who are unable to produce normal speech are able to express themselves through song.

When applied to those suffering with Parkinson’s disease, music with a beat helps patients with motor disorders through rhythmic auditory stimulation. Both the physical velocity and stride gate in attempts to improve mobility, particularly walking, have significant improvements when music is applied. Patients move with more fluidly with music.

Of the arts and sciences provided to the Mason in our ceremonies, music is near the last on the list and usually quickly overlooked. But presented here is that music has been considered critical to learning from ancient times. Yet few are aware of the real impact it can and does have on our development and mental health. Therefore, music should rightly serve as an important tool in our Masonic teachings and study, as it not only forms an important part of the seven liberal arts and sciences, but has proven to be a critical tool in the development and health of mankind. REFERENCES 1. Quadrivium (education)”.

2.

3.

4.

5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Britannica Online. 2011. Patel, Anivruddh: Music and the Brain, The Great Courses, 2015. The Teaching Company.

Lumen - Music Appreciation web site

Herholz, S. C. and R. J. Zatorre: “Music Training as a Framework for Brain Plasticity: Behavior, Function and Structure.” Neuron 76 (2012) p. 486 - 502

Honing, H. “Structure and Interpretation of Rhythm in Music.” The Psychology of Music, 3rd Ed. London: Academic Press/

Elsevier, 2013 Justin, P. N.: “From Everyday Emotions to Aesthetic Emotions: Towards a Unified Theory of Musical Emotions.” Physics of Life Reviews, 10 #3 (2013, p 235 - 266.

Koelsch, S.: “Brain Correlates of Music-Evoked Emotions.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 15, #3 (2014,

p. 170-180. Moreno, S., C. Marques, A. Santos, M. Santos, S.L. Castro, and M. Besson: “Musical Training Influences Linguistic Abilities in 8-Year-Old Children: More Evidence for Brain Plasticity.” Cerebral Cortex, 19, #3 (2009, p.

712 - 723. Patel, A. D.: Music, Language and the Brain, NY: Oxford U. Press, 2008.

10.Vanstone, A., and L. Cuddy:

“Musical Memory in Alzheimer’s

Disease.” Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition 17 #1, (2009) p. 108–128.

11.Charles Darwin: The Descent of Man, on iPhone format only.