13 minute read

Freemasonry, Fundraising, and the Fair

By B. Chris Ruli Grand Historian

Acommon perception of early Freemasonry, especially in the District of Columbia, is that the Craft relegated itself to a quiet existence—that Masons covertly met in humble meeting places, conferred degrees, and went about their personal or professional affairs, choosing to keep their affiliation discrete. When we examine our past, however, we find that this perception fails history’s litmus test, and there is no better example than the fraternity’s attempt to build a national Masonic temple in the District at the turn of the twentieth century. Instead of fundraising amongst themselves, prominent Masons advocated for a series of grand public Masonic exhibitions, similar to the then immensely popular World’s Fairs, to raise funds and promote the fraternity’s goals.

Advertisement

Freemasonry experienced a dramatic influx in membership following the Civil War, which coincided with growing interest nationally in fraternities and civic-focused

organizations. Building a national Masonic temple was necessary, in part, because the Grand Lodge’s temple on 9th and F street became ill-equipped to handle crowded Masonic and non-Masonic events. By 1896, Columbia Commandery No. 2, Knights Templar, called for a meeting across interested groups to build a larger space. The group identified a corner lot intersecting New York Avenue, Thirteenth, and H streets, and with Grand Lodge approval, moved to purchase the space for $70,000.

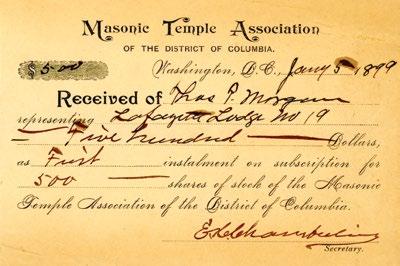

Meanwhile, the group tackled their first problem: how to manage and organize a large public Masonic event. They reconvened on November 27, 1897 to organize the “Masonic Temple Association,” elect their first executive board, and lay out their strategy. “The Board” established twelve sprawling subcommittees to manage every aspect of the event, which included committees on entertainment, finance, charitable contributions, etc. They selected April 1898 as their opening night and secured the Northern Liberty Market, the District’s first conventional hall and now site of the Carnegie Library, as their venue. News spread quickly and Masonic groups rushed to secure coveted space in the hall.

With limited space, the board invited Masonic bodies across the District to apply to participate. This provided an opportunity to select the most lucrative proposals and help cut down on costs. It also introduced a competitive spirit to the event. The Washington daily newspaper, The Evening Star, reported:

“There is already generous but spirited rivalry [among the Masonic groups] for the different privileges in which there seems to be the most money. Almas Temple of the Mystic Shrine has already put in an application for the paddles privilege. Pentalpha Lodge asks for the use of all the galleries as an ice cream parlor.”

Charitable contributions and publicity helped fuel the fair’s early success. The Donations Committee launched an enormous letter-writing campaign, which sent thousands of requests to Masonic and fraternal organizations across the United States and abroad. Weekly reports in The Evening Star and other newspapers covered the interesting donations: $1 from the oldest Mason in New Hampshire, a brick from President Grant’s Tomb in New York City, round-trip tickets to Yellowstone National park, $100 from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West company, and an autographed picture from Mexican President and Past Grand Master Porifiro Diaz. Diaz’s picture included a personalized note: “I regret

to say that I cannot accept the invitation [to attend] as my official duties prevent my being absent from my country, but I assure you of my great satisfaction at the consideration thus expressed.” In February, reporters announced the fair’s largest donation, a deed to ocean-front property in Ocean City, Maryland – lot 7 block 49.

As competition picked up, the Board fretted over shrinking space. Crews at the conventional hall erected a large stage on the north wall to host nightly concerts. This connected to a thirty-foot walking path with three rows of booths arranged on either side. Each booth stood twentyfive feet tall and was decorated with flags, banners, and intricate designs. Engineers set up smaller booths around the perimeter and each Masonic group was free to decorate their own booth. Harmony and Pentalpha Lodges competed for the hall’s largest attractions, a series of connected booths called the Old English Village and the Swiss Chalet, respectively. Several groups joined either lodge to create complementary decorated booths. On February 28, the Board announced that they had secured the adjoining building, the former National Guard armory for overflow space.

An international theme permeated the fair as crews erected Roman temples, English cathedrals, German castles, and mosques. The Shrine acquired two booths, on either side of the hall, and built a replica of the Acropolis. Lafayette Royal Arch Chapter installed a telegraph cable that connected patrons with Masons in Hawaii and Spain for a nickel. The Communications Committee contracted with local journalists to operate their own daily newspaper of the event, which operated out of the hall and disseminated advertisements, news, and gossip.

The Board released a tentative event schedule in March. Excluding the opening ceremonies, each night featured a salute to a certain Masonic and non-Masonic organization like the Shrine, Scottish Rite, or Order of Eastern Star. Masons were also encouraged to dress up for each night in the body’s respective regalia, which added a fun element each night. The entertainment committee partnered with musical groups, local theaters, circuses, and temperance societies to perform musical acts and educational lecturers. One night featured a program on the Veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic. President William McKinley and Vice President Garret Hobart, both Freemasons, accepted

invitations to participate in the opening festivities. Prince Albert, the Grand Master of England and future King Edward VII, extended his well wishes as official duties made it difficult for him to travel to Washington. Alexander R. Shepherd, the District’s first governor and notorious political boss, could not attend in person but provided the Board a “sizeable financial contribution” and a ceremonial brick for their new temple.

The convention hall pulsated with energy as committees, board staff, construction crew, and Masonic groups descended to make their final arrangements. “Decorators in scores were busily engaged putting deft and artistic touches to the numerous booths, and flowers, flags, bunting, emblems, and beauty-making articles, reported The Evening Star. “…and wagon after wagon rolled up and deposited their loads of useful, beautiful, novel, and attractive things.”

Then, on April 11, President McKinley situated himself at a table in the White House’s telegraph room. Unable to attend in person, fair engineers installed a special receiver box to connect McKinley to the hall. At around 8:30 PM, McKinley switched on the receiver, which immediately illuminated hundreds of lanterns scattered across the hall. McKinley then placed a call to a phone set up on the north stage which was received by Board president Henry Small. “The President,” Small announced, “sends greetings to the Fraternity and wishes them every possible success.” As the president wrapped up his remarks, a 300-person chorus erupted with a rendition of “America,” as Healy’s Band and the thousands in attendance joined in the rapturous patriotic spirit.

The opening ceremonies attracted such a large crowd that it prompted the Board to halt admission thirty minutes into opening. “So tremendous was the throng... that at 8 o’clock the entrance doors to the convention hall were closed, and probably a thousand people found themselves unable to gain admission,” reported The Evening Star. “Half an hour later...the doors were opened again, but at 9:30 it became necessary to repeat the closing. This time there were probably 4,500 people in the convention hall and armory annex.”

Small received Vice President Hobart and John A. Porter, McKinley’s private secretary and Freemason, at 10:00 PM. The White House Committee joined other dignitaries already in attendance including the Secretary of Agriculture James H. Wilson, Montana Senator Lee Mantle, California Senator George C. Perkins, and the District of Columbia’s three commissioners.

Three days later, on April 14, the bill to incorporate the temple association passed both Houses of Congress and made its way onto President McKinley’s desk for his signature.

Reporters recorded the largest fair attendance on April 16, during “Eastern Star Night.” Over 14,000 guests, nearly

double the average attendance, came out to support the women’s contributions to Freemasonry. While originally scheduled to close on April 23, the Fair’s success led Small to extend festivities for three additional nights. Booths expedited the clean-up process through flash auctions to clear remaining merchandise. The US Marine Band headlined entertainment on April 25 with guest conductor Clare Elizabeth Taylor. Taylor’s performance, which included an original Masonic composition entitled the Osiris March, made history as it was the first time a woman conducted the Marine Band.

The fair closed on April 27, but considerable work lay ahead to clear the board’s accounts and tally their collections. When the final tally was made, the first fair raised $72,000 towards the building project, which later swelled to $85,000 by 1902. Confident in future fundraising efforts, the Board paid off their debt towards the lot and issued bids to design the future building. They also immediately began working on a second fair.

Small, still acting as the Board’s president, appointed Frank H. Thomas as Director of the second fair, which allowed the Board to focus their attention on design and fundraising. Under Thomas’ stewardship, the second fair adopted a nature theme. Engineers installed verdant boughs, tree limbs, and hundreds of electrified Japanese lanterns across the hall and annex. Mount Vernon Royal Arch Chapter built a replica of George Washington’s estate around the pastoral landscape and transformed the balcony into a drinking parlor. Harmony Lodge constructed a dancing stage in the annex, which was a sorely missed feature of the previous fair. The entertainment committee secured rights to exhibit Houdon’s famous Washington Life Mask.

As Thomas fretted over the theme, Small and the Executive Committee aligned themselves with the District’s political and professional elite. By late February, newspapers reported that around hundred members of Congress, seventeen senators and sixty members of the

The Washington Times, Tuesday, May 22, 1906

house, and one hundred local businessmen signed on to serve as honorary members. Notable members included Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson, Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Milton E. Ailes, and the District’s three commissioners. The committee served a critical role a week leading up to opening ceremonies.

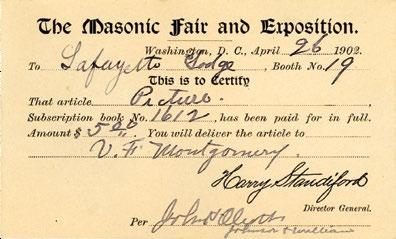

On April 8, the District’s fire inspectors notified Thomas that the Japanese lanterns arranged throughout the hall violated district code. “Thomas hurried to the Capitol, where he consulted a number of brother Masons who were members of Congress,” The Washington Times reported. “A joint resolution was immediately offered in the House by Mr. Richardson of Tennessee1…Similar action was taken in the Senate. It is understood that the favorable action will be taken by both bodies today.” With the permits secured in record time, Thomas negotiated to have DC Fire and Police attend the fair and set up a booth for public safety. The Board also covered the cost to install special sprinklers. The second Masonic Fair and Exposition opened on April 14, 1902. Over two thousand patrons crowded the busy north stage at 7:30 PM to witness another grand Masonic parade. As the procession entered the hall and marched up to the stage, lines broke into two columns to allow Small and George Walker, Deputy Grand Master of D.C., to walk between and ascend the stage. Walker, wielding the George Washington Gavel, provided a brief introductory oration. Several moments before his finale, a cable operator relayed a message to President Roosevelt in the White House War Room. Like his predecessor, Roosevelt switched on a receiver box from the White House turning on thousands of Japanese lanterns. Overall, about 109,000 individuals attend the second fair or an average of 6,500 attendees per night. While not as successful, the Board added a modest $50,000 into the Temple Fund.

The third Masonic Fair and Exhibition opened on April 15, 1906 with the usual pomp and flair. President Roosevelt returned for the opening ceremonies to

1 Congressman Richardson would soon leave the House of Representatives, forsaking his dream of becoming the Speaker of the House to serve the Craft as Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite.

Masonic May festival, 1906

switch on a receiver at the White House. He later sent over several autographed postcards and a pillow signed by the entire cabinet to raise funds. Approximately 10,000 guests attended the first evening, but Thomas was forced to temporarily close the hall’s doors an hour after the opening ceremony to prevent a fire hazard or stampede. The fair culminated with a grand ball and concert on May 2. Crews rearranged booths to create a large dance floor in the middle of the hall with sideline booths retrofitted to sell light refreshments. Smith set up a stage in the middle of the dance hall to host Professor Healy’s orchestra. Over 2,000 couples attended the ball, which provided a fitting end to the Fraternity’s most ambitious project.

Masons gathered two months later, on June 8, 1906 to lay the cornerstone of the new Masonic Temple. The ceremony culminated nine years’ worth of planning and execution. President Roosevelt accepted an invitation to help lay the cornerstone. Clad in a Masonic apron and wielding Masonic tools first used by George Washington in 1793, Roosevelt performed his Masonic duties to the delight of spectators. “Surely there is no place,” said Roosevelt, “where there should be as fine a Masonic Temple as here in Washington, for it is in a sense a National Temple where Masons from every jurisdiction gather.”

There are several factors to the fraternity’s success in these endeavors. First, by virtue of their membership, the board was able to tap key figures in DC’s political, economic, and social sphere. Many of whom, were members themselves. By the turn of the century, the Grand Lodge grew to around 9,000-members or about three times as large as our total membership today. This figure doesn’t take into account the role of the Eastern Star, sojourning Masons living in DC, and ancillary Masonic groups that increased total participation dramatically. Another direct benefit of this close association was the fair’s unprecedented marketing and media coverage through local newspapers.

The second factor to success revolved around public outreach. While recruitment is prohibited, the multi-week events offered the public an opportunity to better understand the goals of the Craft, their charitable efforts, and reach across different social-economic groups. Fairs showcased scientific breakthroughs, introduced patrons to new art, and entertained guests with nightly concerts and political discourse. Fairs provided an opportunity for Masons and their guests to hob-knobb with politicians, philanthropists, and DC’s social elite.

But perhaps the most important factor towards success was the decision to organize a fair in the first place. The idea broke from traditional public exercises like Masonic processions and cornerstone laying ceremonies. Letter-writing campaigns developed a global network of donations. A competitive environment also enabled lodges to think creatively, seek assistance across their entire membership, and

innovate. In a sense, each Masonic body transformed into their own sports team with their own fans and a “brand identity.”

The National Masonic Fair and Exhibitions were truly a unique showcase of the Fraternity’s ingenuity and spirit. It brought together the entire jurisdiction towards a singular goal. And the event provides valuable insight into what future leaders can do with fundraising projects and helps reshare our understanding of the District’s “Masonic experience.”