FREEMASONRY, FUNDRAISING, AND THE FAIR By B. Chris Ruli Grand Historian

A

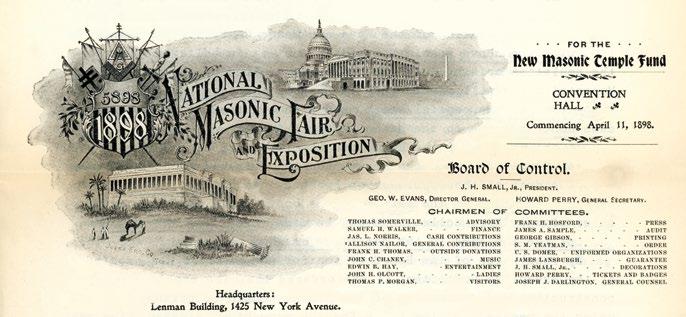

c o m m o n perception of early Freemasonry, especially in the District of Columbia, is that the Craft relegated itself to a quiet existence—that Masons covertly met in humble meeting places, conferred degrees, and went about their personal or professional affairs, choosing to keep their affiliation discrete. When we examine our past, however, we find that this perception fails history’s litmus test, and there is no better example than the fraternity’s attempt to build a national Masonic temple in the District at the turn of the twentieth century. Instead of fundraising amongst themselves, prominent Masons advocated for a series of grand public Masonic exhibitions, similar to the then immensely popular World’s Fairs, to raise funds and promote the fraternity’s goals. Freemasonry experienced a dramatic influx in membership following the Civil War, which coincided with growing interest nationally in fraternities and civic-focused

26 | THE VOICE OF FREEMASONRY ISSUE 3, 2020

organizations. Building a national Masonic temple was necessary, in part, because the Grand Lodge’s temple on 9th and F street became ill-equipped to handle crowded Masonic and non-Masonic events. By 1896, Columbia Commandery No. 2, Knights Templar, called for a meeting across interested groups to build a larger space. The group identified a corner lot intersecting New York Avenue, Thirteenth, and H streets, and with Grand Lodge approval, moved to purchase the space for $70,000. Meanwhile, the group tackled their first problem: how to manage and organize a large public Masonic event. They reconvened on November 27, 1897 to organize the “Masonic Temple Association,” elect their first executive board, and lay out their strategy. “The Board” established twelve sprawling subcommittees to manage every aspect of the event, which included committees on entertainment, finance, charitable contributions, etc. They selected April 1898 as their opening night and secured the Northern Liberty Market, the District’s first conventional hall and now site of the Carnegie Library, as their venue. News spread quickly and Masonic groups rushed to secure coveted space in the hall. With limited space, the board invited Masonic bodies across the District to

apply to participate. This provided an opportunity to select the most lucrative proposals and help cut down on costs. It also introduced a competitive spirit to the event. The Washington daily newspaper, The Evening Star, reported: “There is already generous but spirited rivalry [among the Masonic groups] for the different privileges in which there seems to be the most money. Almas Temple of the Mystic Shrine has already put in an application for the paddles privilege. Pentalpha Lodge asks for the use of all the galleries as an ice cream parlor.” Charitable contributions and publicity helped fuel the fair’s early success. The Donations Committee launched an enormous letter-writing campaign, which sent thousands of requests to Masonic and fraternal organizations across the United States and abroad. Weekly reports in The Evening Star and other newspapers covered the interesting donations: $1 from the oldest Mason in New Hampshire, a brick from President Grant’s Tomb in New York City, round-trip tickets to Yellowstone National park, $100 from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West company, and an autographed picture from Mexican President and Past Grand Master Porifiro Diaz. Diaz’s picture included a personalized note: “I regret