APRIL 2022

APRIL 2022

GAI’s Community Solutions Group (CSG) is a cross-functional team of professionals that helps create sustainable, livable places. We plan and design public spaces, sculpt landscapes and parks, reimagine streets and roads, and provide the regulatory and economic insight necessary to bring projects to life.

Raymond Stangle | Community Development Administrator

Steven Kane | Director of Transportation and Transit

Kelly Haddock | Community Development Assistant Administrator

Kevin Ostrowski | Sports and Events Facilities Manager

Jeff Kuenzli | Sports Facility Manager

Osceola County 1 Courthouse Square Kissimmee, FL 34741 (407) 742.0336

GAI CONTACTS

Owen Beitsch, PhD, FAICP, CRE | Senior Director

Laura Smith | Project Manager

Natalie Frazier | Senior Analyst

Community Solutions Group, GAI Consultants, Inc. 618 East South Street, Suite 700 Orlando, FL 32801 (407) 625.1280

▪ This Publication is intended for the Client’s use for purposes of information, marketing, and other activities. Partial excerpts of, or partial references to the Publication in any form must acknowledge that these passages are out of context and the entire Publication must be considered or viewed.

▪ Possession of the Publication or copy thereof by anyone other than the Client, does not carry with it the right of publication or reproduction.

▪ Certain data used in compiling the Publication was furnished from sources which we consider reliable; however, we do not guarantee the correctness of such data, although so far as possible, we have made reasonable, diligent efforts to check and/or verify the same and believe it to be accurate. There could be small errors of fact based on data and methods of reporting or accounting for that data. No liability is assumed for omissions or inaccuracies that subsequently may be disclosed for any data used in the Publication.

▪ GAI has no obligation to update the Publication for information or knowledge of events or conditions that become available after the date of publication.

▪ Authorization and acceptance of, and/or use of, the Publication constitutes acceptance of the above terms and limiting conditions.

▪ In no event shall either party be liable for any loss of profits, loss of business, or for any indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages of any kind.

Osceola County (“County”) is currently contemplating expansion of Austin Tindall Park (“Austin Tindall” or “Park”), one of central Florida’s largest multi-purpose sports complexes. The expansion will add to the desirability of Osceola County as a destination and also enhance the quality of life for those living in the area. To date, the Park comprises ten multi-purpose fields, a stadium, parking for about 1,700 cars, and various administrative or support facilities. Expansion plans contemplate the addition of ten multi-purpose fields, as well as areas dedicated to cross country running, paint ball and rowing via controlled lake access.

Toward understanding how an enhanced sports complex might fit into Osceola County’s recreational context and what positive impacts and benefits may result from the Park’s expansion, GAI Consultants (“GAI”) was tasked with estimating the economic and fiscal impacts stemming from sports complex activity under various assumed conditions or scenarios.

The work considered academic literature for background, theory, and findings; case studies of multi-purpose sports facilities and complexes; sports participation data for context; review of locally available tourism data for comparisons; and the application of an Impact Analysis and Planning (IMPLAN) model based on the summarized assumptions developed from our research and case studies.

Our findings, based on generalized data with local adjustments, suggest that there could be very significant economic and fiscal impacts as a result of the Austin Tindall Park expansion in Osceola County. Given the nature of the impacts, it is appropriate to support the expansion of Boggy Creek Road with tourist tax dollars.

The findings and conclusions drawn from this economic and fiscal impact analysis are further detailed within the following pages.

▪ In Osceola County, there are many local outlets, such as restaurants, drinking establishments, retail shops, other entertainment alternatives, and proximate destinations which we believe may stimulate and capture the elevated direct spending which would occur as a result of the Austin Tindall Park expansion.

▪ The case study research provided valuable data points on their operational impacts, annual visitation, and overnight accommodations which proved beneficial in estimating the potential use and demand of the Park expansion in Osceola County.

▪ Annual attendees to the proposed Park expansion in Osceola County will be between 416,820 to nearly 833,640 visitors based on the current capture at Austin Tindall Park and the expected capture at a stabilized year following the expansion. Additionally, the annual visitors who stem from non-local attendees will be about 58.6%, and the average percentage of annual visitors who spend the night in the local area will be between 24% and 40%.

▪ Economic impacts within our IMPLAN model were measured in terms of sales, income, jobs, and value added. The IMPLAN model accounts for two types of visitor spending: (1) total daily expenditures, and (2) spending on overnight accommodations.

▪ Our analysis reflected a low, moderate, and high range of potential impacts. We believe the moderate scenario to be the most likely and plausible scenario for planning purposes. However, there are reasons to believe the high scenario could also be attainable, if not conservative.

▪ These impacts reflect a 2025 dollar year, as we assume the County will not experience the impacts associated with the construction of the Park expansion until a later date.

▪ The moderate scenario indicates that direct visitor spending would be approximately $78.4 million on daily expenditures and lodging, as reflected in the table below (see Figure 1).

▪ In our analysis, tax receipts may include any combination of local, state, and federal taxes which accrue to Osceola County. In this analysis, GAI calculated the discrete collections or levies associated with direct property taxes and direct tourist taxes, and relied on IMPLAN to provide taxes on imports and productions for personal property taxes and other taxes associated with the Austin Tindall Park expansion in each development scenario.

Sources: GAI Consultants.

▪ With direct spending of $78.4 million, the total economic impact achieved by Osceola County would be approximately $160.2 million with 831 added employees from on-going operations generating an annual economic output of $81.8 million. The value added, a measure of the County’s contribution to GDP, as a result of the Park expansion reflects about $45.4 million, as reflected in the table below (see Figure 2).

Total Spending

▪ Based on data collected from Osceola County, Experience Kissimmee, and the case study research, our analysis assumes that overnight visitors are estimated to spend between $80 and $160 per person per night, and typically consist of 1 to 3.1 persons per room.

▪ Specifically, we assumed overnight demand is driven mostly by hotel/motel guests for the type of sporting events and activities which take place at Austin Tindall Park.

▪ The moderate scenario indicates that total taxes paid would be about $3.4 million annually, as reflected in the following table (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Total Taxes Paid – Moderate Scenario

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants. Notes: (1) Represented in thousands. (2) Reflects total spending from the moderate scenario of key input assumptions, as described in previous table.

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants.

$3,369,900

Osceola County is currently contemplating expansion of Austin Tindall Park, one of central Florida’s largest multi-purpose sports complexes. The Park, which is now comprised of ten multi-purpose fields, a stadium, parking for about 1,700 cars, and various administrative or support facilities, has plans to grow to about twice its size. Expansion plans contemplate the addition of ten multi-purpose fields, as well as areas dedicated to cross country running, paint ball and rowing via controlled lake access.

With its size and unusually strong orientation to regional and national users and events, the Park and its facilities have few competitors within the greater Orlando area or Florida. As a consequence of its market position, Austin Tindall’s reach and operations have far greater economic and fiscal impacts than other multi-purpose sports parks in Florida and the southeastern United States. Those impacts could literally double in size commensurate with the scope of the planned expansion which will occur over holdings of more than 100 acres acquired by the County over the last few years.

County staff and its consultants have completed several studies to define the operational and planning considerations associated with the expansion of Austin Tindall, including the scope of the park itself, as well its infrastructure and service requirements. These studies have specifically identified a need to make substantial improvements to Boggy Creek Road, the primary surface route providing direct regional access to the Park. In addition to Boggy Creek Road being the only roadway connection to the Park, signage at the Orlando International Airport (“MCO”) directs high volumes of tourist traffic to and from the airport and the Disney entertainment areas along Boggy Creek.

Despite Boggy Creek Road’s high volume of traffic, this road and its direct access to MCO are a means to distinguish and market Austin Tindall park as one of the very few sports facilities which offers extensive and proximate air service to the Park’s targeted

national teams, leagues, and major tournaments events. Austin Tindall has consistently attracted those users and groups who value the ability to move quickly from MCO to the fields themselves, the Disney area, and other nearby fields and attractions.

Studies show the surface transportation network that has benefited Austin Tindall is now a physical challenge to the Park’s expansion. Based on the materiality of that road connection, it is reasonable to posit that the failure to advance improvements along Boggy Creek Road poses very real limits to the potential growth of the Park’s activity and any subsequent fiscal economic impacts. At the very least, the reported decline in the level of service for Boggy Creek Road creates operational constraints on the Park and its scheduling. These constraints will only be more challenging with additional background traffic from residential growth, new schools, and the County’s own interest in advancing commercial development that would directly benefit from close proximity to Austin Tindall.

This Economic and Fiscal Impact study describes the growth in sports activity and participation which shapes trends in the highly competitive sports tournament and training businesses. This study also details national interest in facilities like Austin Tindall Park, the economic benefits often associated with these sporting activities and businesses, the scope of the Park expansion, the experience at other sports complexes, and the specific impacts to be gained (or lost) as the result of the required improvements to Boggy Creek Road and planned Park expansion.

Spending associated with youth and adult organized sports is a basis for big business, major transactional activity, and significant economic impact. Much of this activity occurs in parks and recreational facilities developed and supported by local governments. These are developed and operated as a way to provide local venues for residents but also as a way of drawing outside visitation.

Without regard to the specific nature of the parks themselves, some estimates place the national economic accounts linked to recreational activity occurring in parks at about $166.0 billion (2017) annually. That level of activity supported more than 1,000,000 jobs and $51.0 billion in related wages, up from about $43.0 billion reported just a few years earlier (2015 NPRA Study). A large portion of those flows are experienced in Florida where a very narrowly focused study estimated impacts of $2.2 billion dollars from state park operations alone in fiscal year 2020 (EIA report), supporting about 32,000 jobs.

Existing within this broad framework, facilities supporting or associated with organized sports are an especially visible and highly marketed segment. While sports facilities may compete at multiple levels, there are only a limited number with (1) the approved or certified design, (2) supporting infrastructure, (3) capacity, (4) seasonal availability, and (5) general locational attractions to extend their reach nationally. Given that set of conditions, Austin Tindall Park is especially well positioned to maintain a dominant position, choosing among those teams and events that can most maximize its impacts.

The Park’s current scheduling and activity are a window into the longer-term impacts associated with its continuing operations. Toward understanding what a materially expanded Park and schedule of events could mean once the expansion is stabilized GAI Consultants (“GAI”) was tasked with estimating the economic and fiscal impacts gained under various assumed conditions. These conditions consider Austin Tindall’s reported experience, as well as information gleaned from other multi-purpose parks with a strong orientation to organized sports. Because of the hypothetical nature of the analysis, GAI believes the assumptions and outputs must reflect a low, moderate, and high range of potential outcomes. Austin Tindall’s prior performance, Disney’s presence, the region’s increasing air service, and other influences may not be adequately captured in our

models, potentially understating the results across scenarios.

The work considered academic literature for background, theory, and findings; case studies of sport and recreational facilities, centering on spending patterns and attendance; sports participation data for context; review of locally available tourism data for comparisons; and the application of an IMPLAN model based on the summarized assumptions developed from our research and case studies. Altogether, GAI looked at the experience of approximately eighteen other sports facilities, pulling together various data from many parts of the Country, operating at different levels of sophistication, and servicing varied market segments or sports.

Not surprisingly, the literature which explores the economic relationships among sports-centric parks, business activity, and property values, is well developed by academics, organizations, and observers. The academic literature is especially important because it removes the obvious bias in studies prepared by advocates. Regardless, studies completed using different standards and measurements are largely in agreement on key issues, thus establishing an analytical framework that is well researched, understood, and accepted. Over many studies, researchers have explored a range of variables and factors associated with organized sports activity. This body of information offered a logical framework for considering, or excluding, similar factors and their impacts in our own local circumstance.

GAI relied extensively on data that had been collected over the course of many years in several settings and adjusted any spending information to 2021 dollars to aid comparisons. The analysis also considered data from Orlando and Kissimmee specifically which, of course, have their own discrete spending characteristics because of the region’s theme park influences. The reconciled case study data is illustrated in several tables within this report.

Finally, GAI prepared and discussed with staff the key activity and spending assumptions for use in the IMPLAN models. IMPLAN is a recognized input-output model that illustrates how spending generated within various economic sectors flow throughout the region. IMPLAN’s output is expressed in terms of regional sales activity, jobs, wages, and governmental receipts. GAI expanded upon IMPLAN’s measure of the latter by focusing on tourist taxes as well as several discrete classes of property taxes so this indicator of fiscal benefit would be much more specific to Osceola County.

It would be an omission to ignore the limitations of this or similar models which largely discount an area’s ability to absorb added spending or the relationship to corporate outflows which are considerable. In the first instance, this region has consistently demonstrated its capacity to accommodate new events and groups of visitors. The second point is more conjectural but the associated spending, wherever it ultimately flows, is employing large numbers of local residents.

Given such caveats, our findings based on generalized data with local adjustments, suggest that there could be significant economic and fiscal impacts. There would certainly be significant lost benefits if operational advantages are not sustained.

For planning purposes, GAI is inclined to adopt the moderate scenario within the analysis. Having made that observation, there are reasons to believe the high scenario could be a plausible, if not conservative, measure of impact because this region has a much more integrated economy than several of the case studies. As a result, there are more local outlets, such as restaurants, drinking establishments, retail shops, other entertainment alternatives, and proximate destinations which may stimulate and capture the elevated direct spending which would occur. Unlike most of the communities where sports facilities are located, Osceola County also has a highly evolved marketing system in place that heavily promotes substantial tourism activity, much of it directly and continuously targeted towards organized or sanctioned events.

The adjacent figure illustrates Austin Tindall’s existing complex in relation to Boggy Creek Road (see Figure 4).

The economic and fiscal analysis completed in this effort is consistent with the findings reported in many studies that have been reviewed for this analysis. Below, GAI has summarized findings from selected peer reviewed academic studies published within the last 10 years. These studies explore the benefits or value of tourism generated by sports activity and established sports venues.

The observations of Song, Dwyer, and others (Song, et. al., 2012) are an excellent beginning for the current effort. In their literature review, these authors describe many of the complex linkages among tourist related activities, explaining that the tourism industry follows the same pattern of other neo-classical economic activity. Like other industries, tourism generates spending which then produces measurable output. In particular, they point to spending allocated to various goods with the expectation that the output calculations are substantively dependent upon that spending, its elasticity, and the total count of visitors. Implicitly, if neither the visiting population nor the spending of the visiting population can be accommodated, the impacts that would be realized are displaced or simply never produced.

The authors describe and affirm the economic advantages of clustering and agglomeration. While not mentioned specifically in their work, the Orlando region is the archetype of the highly advanced agglomeration economy oriented to tourism. In such a setting, economic potential is maximized where there are many connected venues or attractions, distance or transportation costs among these are minimized, facility access is assured, and specialized labor skills reduce cost and enhance productivity.

Among the most notable concerns of these researchers is that input-output models often fail to exclude local spending from the calculations. While noting this issue, they also point to the functionality of using input-output models such as IMPLAN to rank order the complex interdependent spending relationships associated with many influencing factors.

Soonhwna Lee (Lee, 2008) advances the discussion about economic impacts by explaining that these impacts can be defined in terms of changes in the local economy resulting from a sport event which, in the Austin Tindall case, is a continuing series of events or activities with a combined level of impact. Such changes arise from the acquisition, operation, development and use of such facilities and their related services. These kinds of activities or initiatives then generate or stimulate spending from visits, visitors, employment opportunities, and tax revenue. Like Song, Dwyer, and others, Lee also cautions that input-output models can overstate their results if the appropriate data is not used, and later goes on to briefly mention the importance of additional social impacts that should be considered, each with its own set of attributes not directly captured in the inputoutput model.

An extensive data set used by Nola Agha in her paper The Economic Impact of Stadiums and Teams: The Case of Minor League Baseball (Agha, 2013), provides a glimpse of the reported economic benefits specific to organized sports in two discrete time periods. Agha’s analysis has the advantages of not focusing on a major league franchise or mega event and using a nationwide base of multiple size teams and schedules. In addition, Agha’s study concludes that in the period covered within the analysis, there was significant positive change in local per capita income. This change was especially pronounced in the context of major league sports where similar data revealed less observable results.

While Agha offers several possible explanations, she comments that the most effective business model at this level of competition absolutely must draw outsiders from beyond a very local and narrow population. Part of that business model will also include a pricing strategy that does not dampen or displace spending otherwise allocated for other events. Where spending is not displaced, even modest local spending for minor league sports would be associated with net gains in output. Similar ideas are expressed by Graham, Ehlenz, and Han (Graham, et. al., 2021), where

they discuss the ways local governments can influence the expected impacts of second tier sports through direct intervention in site selection. Wilson (Wilson, 2006) makes it clear that the most monetary benefit will flow to commercial accommodations, food and drink, and some general retail spending.

Agha and Taks look again at sports in 2015, further distinguishing the impacts of small and large events, occurring in both large and small settings (Agha, 2015). For maximum impacts to be realized, the events need to be scaled to the size of the community to capture all spending. A gap in resource availability will cause the impacts to spillover into adjacent communities Sungsoo Kim (Sungsoo, 2021) states succinctly that sports activity is a valid means of attracting visitors and the impacts can be greater in a smaller jurisdiction if they have the resources to handle the event.

The composition of attendance is a key element in sport spending studies. Veltri, Miller, and Harris (Veltri, et. al., 2009), suggest that insufficient attention is given to the support of spectators that often travel with the actual participant engaged in the organized sports event. They may, for example, be friends or relatives outside the travel party. Many of those spectators, they conclude, are higher income households or individuals with the potential to allocate a bigger dollar share to local spending. That additional boost may not be reflected adequately in many studies.

Keane and others (Keane, et. al., 2019), describe a number of benefits to be considered in sports support. They identify four broad areas, as listed below:

▪ Physical Health

▪ Mental Health

▪ Economic Benefits

▪ Community Development and Well-Being

Their list of impacts and benefits clearly suggest many benefits outside those weighted in strictly economic terms. These social indicators, of course, are more difficult to compute but with time and resources could be equated to proxy measures. In any case, whatever

their precise value, these social or community impacts would be additive to those calculated in a simple economic framework.

Such economic and social impacts as those described above are not that dissimilar from the observations gathered in a number of studies centered primarily on parks and recreation which often include a focus on special events which, among others, typically include sports tournaments.

The country’s largest stadiums and arenas are particular targets of sports research and their impacts because of the substantial financial commitments often extended such facilities. What these studies often ignore or consider minimally are their broader value to the larger community. Matheson (Matheson, 2018) considers a perspective similar to that of Keane and others, arguing that these, or comparable, facilities have value as public goods in much the same fashion as other civic amenities or services, and they are worthy of financial support.

By embracing such venues as something more than settings for league play, Keane and others give these venues added value. They suggest these often criticized sports venues are not unlike libraries, for example, with benefits or attractiveness to a very discrete group of users, often very passionate about their interests. Extending that line of thought, many different sport venues are deserving of minimal support in some proportion to their larger impacts including less well defined social or civic benefits. Even then, that measure of support may not fully recognize the additional ways in which sports venues add to dimensions of civic pride, community amenity, and place building which together act as inducements to more frequent or more extensive periods of visitation.

In their study, Lindsey, Man, and others (Lindsey, et. al., 2004), also point to the appropriateness of public support for a variety of recreational facilities while noting that some jurisdictions will benefit much more than others in terms of increased property tax revenues. Stated somewhat differently, the widely

cast benefits realized from sophisticated recreational systems are not isolated to a specific municipality. As a result, it is rational that any largely attended sports activity or recreational venue would be supported through financial resources beyond those of a levy or charge only locally collected or imposed.

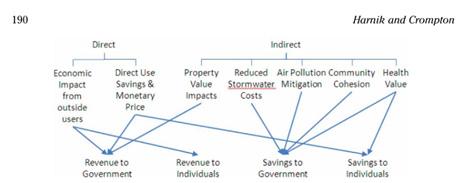

A system-wide illustration capturing these many reported layers, as well as their direct and indirect relationships and consequences, is provided by Harnik and Crompton in their 2014 parks study exploring parks and the claimed values (Harnik, 2014), as detailed in the figure below (see Figure 5).

▪ It is likely all additional spending can be absorbed with no displacement of spending.

▪ Related support facilities and complementing activities are themselves indicating steady growth in capacity.

▪ The focus is on accommodations, food, and limited retail segments

▪ Some attendance and visitation is almost certainly not accounted for in the accompanying models and there may not be sufficient adjustment to reflect additional attendance from friends or the impacts of higher incomes.

(2014).

These brief descriptions of other studies and the above graphic, while certainly not encompassing all viewpoints and possible results, are a balanced foundation for the focus and content of the study completed for Austin Tindall Park. To the points raised in these varied papers, the analysis examines and defined the following park characteristics and operational data:

▪ The attendance and usage of Austin Tindall Park.

▪ The Park has the advantages of its location in the context of roads, facilities, air service, and documented tourist appeal.

▪ Such advantages are important to its performance which is likely to be among the highest of other park or recreational facilities elsewhere.

▪ The Park is supported primarily by outside persons or groups.

▪ The tourist tax structure in Osceola County aligns perfectly with an activity that extends its impacts to a host of related activities dispersed beyond the municipal level.

▪ Without regard to any specific computation, the methods employed, the models used, and the particular measures or issues considered, we erred on the conservative side.

While the interest in Austin Tindall may have some conjectural relationship to Disney or other area attractions, the fact remains that reported attendance and usage are derived from the facilities in place and the infrastructure that enables sports programming to occur.

If indeed attendance was prolonged or attendance at a specific event were a precursor to another visit, that would generate additive impacts only modestly reflected in the present analysis. Likewise, while every effort has been made to exclude the confounding effects of local activity, spending, or events, a certain share of that is additive to Osceola County’s normal economic activity because at least some share of those measures would have been allocated elsewhere.

Finally, as several researchers have observed, there are values well beyond those discretely estimated in the present analysis. GAI has determined that these values are incremental to those summarized within this analysis.

Based on current events data provided by Austin Tindall over the last couple of years, GAI concluded that soccer and tackle football comprise the core recreational activities which take place at the Park. This implies that participation for these discrete recreational activities is greater than 50 times per year. Comparatively, flag football, lacrosse, track and field, ultimate Frisbee, basketball, rugby, and paintball are all casual recreational activities, where participation is less than 50 times per year at Austin Tindall Park.

Sports Market Analytics (SMA) and Sports Business Research Network (SBR) compile a comprehensive profile of sports and recreational participation. The table below summarizes a number of discrete indicators from the SBR database, as well as the compound annual growth rate (“CAGR”) for a period of five years (see Figure 6).

Soccer

Football (Flag) All

Sources: SBRnet, Inc. 2021. All Rights Reserved.

Generally, GAI compiled selected user data for several discrete recreational activities that could benefit from an expansion of Austin Tindall Park. These include soccer, tackle football, flag football, track and field, lacrosse, ultimate frisbee, and paintball, although certainly there are others. The information largely parallels the kinds of users and interest described in the literature and the various case studies assembled in this analysis.

Although, the many millions of people nationwide that have elected to recreate outdoors has declined since 2016 with the exception of soccer and flag

football, the South Atlantic participation has grown in almost all recreation activities during this same time frame. Compared to the other recreational activities, track and field, ultimate frisbee, and soccer have seen the largest growth in the South Atlantic. Anecdotally, that figure could be up in SBR’s next release which would cover the post COVID era. In any case, the participants in these activities number in the high millions, and many of these users will be drawn to the expanded sports complex such as the proposed. The depth of interest and the number of possible participants is significant and consistent with our economic impact conclusions.

As part of this analysis, GAI relied extensively on data that had been collected over the course of many years in eighteen case study situations and adjusted any spending information to 2021 dollars to aid comparisons.

The various analyses of comparable multi-purpose sports facilities provided a frame of reference to assist our team in drawing assumptions for use within our IMPLAN model, as well as providing conclusions to the various degrees the proposed expansion of Austin Tindall Park could potentially achieve in terms of economic impact to Osceola County. GAI’s approach drew largely, but not exclusively, on the analysis and comparison of selected multi-purpose sports complexes located in other markets of various size and context. The analysis also considered data from Orlando and Kissimmee specifically which, of course, have their own discrete spending characteristics because of the region’s theme park influences.

Specifically, GAI analyzed the operational impacts achieved by each multi-purpose sports facility. These impacts include any activity that supports the visitor experience and overall spending, and are part of the ongoing operation of events at the sports

complexes. The analysis also examined the annual visitation, overnight accommodations, and types of use and sporting events achieved by each complex. These valuable data points and related characteristics are beneficial indicators to the potential market opportunities that are most likely achievable as a result of the proposed Austin Tindall park expansion in Osceola County, as well as an identification of longterm market potential.

The multi-purpose sports complexes within the case studies, where data was available, ranged in annual number of events from one tournament a year to over 400 events at a complex hosting multiple sporting events annually. The types of users and activity that could be achieved as a result of the proposed Park expansion is also important when considering the business cycle and planning for year-round economic activity. Although the case studies span across multiple towns, cities, and states, the main activities that users typically engaged in at the complexes was relatively uniform with soccer and tackle football comprising the largest share of events. This is comparable to Austin Tindall’s current event attendance with soccer and tackle football achieving

approximately 78% and 11%, respectively, of the total events in 2021.

Measuring the number of annual visitors is not necessarily uniform across all multi-purpose sports complexes and can vary depending on the size of the setting, the marketability of the facility, and if there are other local attractions and amenities in the nearby area to draw in visitors. In the case studies, annual visitors ranged from 1,005 to nearly 463,600 attendees.

Creating a destination sporting attraction is not limited to local populations, and will be greatly influenced by demand from non-local, distant local, and international visitors. Therefore, our analysis examined the percent of non-local residents using each sporting complex within the case studies. The analysis concluded that local residents make up approximately 41% of total annual visitors, where as non-local visitors comprise nearly 59% of annual attendees.

This analysis also considered how many annual visitors required overnight accommodations after attending a sporting event at the various facilities

within the case studies. GAI found that between 24% and 40% of annual attendees stay the night, with between 1 to 3.1 persons per room. According to the data received, Austin Tindall is currently achieving a room night per attendee capture of 24% as of 2021. The analysis concludes that the percentage of overnight guests examined within the case studies includes only visitors which require lodging within the local area in terms of hotel/motel accessibility.

The discrete spending behaviors for each case study was also examined. Specifically, the spending within Orlando and Kissimmee, since these regions have unique behaviors due to their theme park influences. These discrete spending behaviors significantly influenced our key input assumptions for the IMPLAN model and are described in detail in Section 5.

Each of the eighteen case studies provided valuable data points on their operational impacts, annual visitation, and overnight accommodations which can be beneficial in estimating the potential use and demand of the proposed Austin Tindall Park expansion in Osceola County, as detailed in the following section.

Our approach estimated operational impacts in terms of non-local attendee or visitor spending based on the results of approximately eighteen case studies, the insights provided from the academic literature, and current operations data of the existing Austin Tindall Park over the last five years. For this analysis, spending and spending changes from visitor behavior comprise inputs to our IMPLAN model to determine responses in economic activity resulting from these behaviors. The IMPLAN model accounts for two types of visitor spending: (1) total daily expenditures, and (2) spending on overnight accommodations. Spending for each of these categories was then broken down by industry according to NAICS codes.

Visitor spending is the primary link between recreation activity and the local economy. Visitors staying overnight in hotels and motels spend the most money per trip, followed by visitors on day trips from outside the local area. Visitors from the local area spend the least. There is also differences between the allocation of expenses across lodging, meals, groceries, transportation, and other categories varies between these segments. Total visitor spending is estimated by multiplying a spending average by the volume of activity. This is best carried out by disaggregating visitors into a set of visitor segments that capture the mix of visitor types and the associated differences in their spending. For this analysis, only non-local attendees were considered in calculating the total spending on daily expenditures and lodging. Since only expenditures by the non-local visitors contribute to the local economy by bringing in new money, our estimates should be further viewed as conservative.

It is important to note that visitors may also spend on other items not accounted for in this IMPLAN model, such as additional spending at other attractions in the area or spending on businesses that do not currently exist. Therefore, we believe even our high scenario of estimates are likely conservative, as the actual impacts could possibly be well above these numbers.

For regional economic analysis, our study reflects park usage and activity in terms of annual visitors and average percentage of total attendees who spend the night during their visit to Austin Tindall Park. Our analysis concludes that annual visitors to the proposed Park expansion will be between 416,820 to nearly 833,640, based on current capture at Austin Tindall Park and the expected capture at a stabilized year following the expansion. In addition, we assume that approximately 58.6% of annual visitors stem from non-local attendees, and the average percentage of annual visitors who spend the night in the local area will be between 24% and 40%. These values are consistent with the case study research and have been applied to our key input assumptions within the IMPLAN model.

In each of the development scenarios, all non-local attendees are estimated to spend between $103 and $186 per person per visit on daily expenditures which includes dining, groceries, transportation/ parking, entertainment, retail, miscellaneous/other, and fuel. These numbers were consistent with several of the case studies on spending behaviors related to multi-purpose sports facilities. The table below illustrates the breakdown between the individual daily expenditures categories listed above and the percentage applied to total spending per non-local attendee (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Daily Expenditures Breakdown

Sources: GAI Consultants.

These values were then applied to the estimated spending per non-local attendee which resulted in the total annual daily expenditures, which was used as a key input assumption in our IMPLAN model and is reflected in the table below (see Figure 8).

$ Spent2 $103.40 $144.50 $185.70 Est. Total Annual Expenditures ($, 000s) $25,248.0 $53,882.2 $90,694.9

Sources: GAI Consultants. Notes: (1) Represents % of annual park attendees who are non-local attendees. (2) Reflects per visitor per day.

Figure 9. Spending on Lodging Assumptions

Avg. $ Spent2 $79.86 $119.78 $159.71

Total

Sources: GAI Consultants. Notes: (1) Represents % of annual park visitors who spend the night. (2) Reflects per overnight visitor

The total combined estimated spending for daily expenditures and lodging for each development scenario is illustrated in the table below (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Total Direct Spending in All Scenarios

Sources: GAI Consultants. OVERNIGHT ACCOMMODATIONS

Overnight spending includes lodging at hotels, motels, bed and breakfasts, AIRBNB, campgrounds, or any other licensed establishment. As previously referenced, GAI found that between 24% to 40% of annual visitors are estimated to require overnight accommodation. Overnight visitors are estimated to spend between $80 and $160 per person per night, and typically consist of 1 to 3.1 persons per room. Since tourism in the Orlando and Kissimmee region is already high due to their theme park influences, we believe the range of overnight visitors should be considered conservative. Taking into account the percent of annual visitors who stay the night and the average of persons per room, the total estimated annual spending on lodging is reflected in the following table (see Figure 9), and was used as a key input assumption in our IMPLAN model.

000s)

Section 6 applies these key input assumptions into the IMPLAN model to generate the economic and fiscal impact of the proposed Austin Tindall Park expansion in Osceola County.

IMPLAN provides a basic input/output model of economic activity that can be used to identify the effects of a specific stimulus, such as employment in a specific industry or investment in the construction of new facilities or the operational expenditures from a firm or industry. IMPLAN and similar models replicate the reported interactions and accounts between or among industries and households in an economy, identifying forward and backward transactions which impact the production and consumption of goods and services. The various economic impacts are measured in terms of the sales, jobs, income and tax revenues generated by the activities being traced.

IMPLAN models estimate the resources required to produce given quantities of different kinds of output. The most direct impacts of activities involve economically connected or proximate businesses, households, and units of government. Economic impacts address distributional issues, identifying gains or losses in economic activity for particular regions or economic sectors.

The economic impacts are measured in terms of sales, income, jobs, value added, and tax receipts. The model traces impacts through direct and secondary effects. Visitor spending effectively is captured as sales activity by firms in the region within discrete categories, notably hotels, retail, and related accounts. Jobs are consistent with Bureau of Labor Statistics data and do not differentiate part- time jobs from full- time jobs. Personal income includes wages and salaries, payroll benefits, and income of sole proprietors. Total income adds in profits and rents of businesses.

Value added is the metric of economic significance preferred. It discretely centers on the contribution of the activity or industry to gross regional or national product. Value added includes the personal income to households (wages, salaries, and payroll benefits), profits and rents of private firms, and

indirect business taxes accruing to government units in the region. Because value added is not as widely understood as the other measures, personal or total income are often reported instead. Personal income, total income or value added are especially useful when comparing impacts across economic sectors.

These effects comprise initial and subsequent spending, as well as initial and subsequent rounds of impacts, which continue until all activity leaks to the larger region or state. This model, through the choice of inputs and appropriate multipliers, has considered economic impacts primarily to Osceola County and fiscal impacts, to the degree they are localized, exclusively to Osceola County. No local economy produces every good or service, capturing all economic activity. When there are gaps in local production, the local effects will be reduced.

As money and purchases circulate through the economy, moving from one business to another and one individual to another, the economic benefits are shared, the multiplier effect.

▪ Direct Effects are the sales, income, and jobs in those businesses selling directly to visitors, in this case the hotels, restaurants, amusements, gas stations, grocery stores, and retail shops.

▪ Indirect Effects result when hotels and other directly impacted businesses buy goods and services from other businesses within the region, so-called “backward-linked” industries. Inputoutput models estimate these effects by using a production function for each sector and estimate the propensity of businesses to buy goods and services from local suppliers.

▪ Induced Effects stem from household spending of income earned directly or indirectly from the visitor spending. For example, hotel and restaurant employees live in the area and spend their income on housing, groceries, and personal activities. This spending supports other or additional jobs in a variety of local businesses.

▪ Collectively, the indirect and induced effects are termed secondary effects. The total impact of visitor spending is the sum of direct, indirect, and induced effects. The figure below illustrates this multiplier effect (see Figure 11).

The following sub-sections illustrate the low, moderate, and high scenarios of impacts this analysis assumes to be possible of the proposed expansion to Austin Tindall Park in Osceola County based on the IMPLAN model. These impacts reflect a 2025 dollar year, as we assume the County will not experience the impacts associated with the construction of the Park expansion until a later date.

SCENARIO

The low scenario indicates that with direct spending of $33.2 million on annual expenditures (dining, groceries, transportation, entertainment, retail, and other) and lodging, the total economic impact achieved by Osceola County would be approximately $67.3 million (see Figure 12). The total job count of from on-going operations, at nearly 354 employees, is

associated with over $34.0 million in annual economic output and $10.0 million in total annual earnings. Direct job impacts associated with the Austin Tindall Park expansion total nearly $25.4 million in annual economic output and $7.9 million in annual earnings. The value added in this scenario, a measure of the County’s contribution to GDP, reflects about $18.6 million, as a result of the Park expansion.

The moderate scenario indicates that with direct spending of $78.4 million on annual expenditures (dining, groceries, transportation, entertainment, retail, and other) and lodging, the total economic impact achieved by Osceola County would be approximately $160.2 million (see Figure 13). The total job count of from on-going operations, at nearly 831 employees, is associated with more than $81.8 million in annual

economic output and $24.2 million in total annual earnings. Direct job impacts associated with the Austin Tindall Park expansion total nearly $61.3 million in annual economic output and $24.2 million in annual earnings. The value added in this scenario, a measure of the County’s contribution to GDP, reflects about $45.4 million, as a result of the Park expansion.

13. Moderate Scenario of Direct, Indirect, Induced Effects and Total Spending

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants. Notes: *Reflects total spending from the

The high scenario indicates that with direct spending of $144.3 million on annual expenditures (dining, groceries, transportation, entertainment, retail, and other) and lodging, the total economic impact achieved by Osceola County would be approximately $297.2 million (see Figure 14). The total job count of from on-going operations, at nearly 1,525 employees, is associated with more than $152.8 million in annual

economic output and $45.6 million in total annual earnings. Direct job impacts associated with the Austin Tindall Park expansion total nearly $114.9 million in annual economic output and $45.6 million in annual earnings. The value added in this scenario, a measure of the County’s contribution to GDP, reflects over $85.9 million, as a result of the Park expansion.

14. High Scenario of Direct, Indirect, Induced Effects and Total Spending

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants. Notes: *Reflects total spending from

The subsequent rounds of spending that create indirect and induced employment impacts are those most likely to benefit the neighboring areas adjacent to Austin Tindall Park. While these employment impacts can occur anywhere within the region, the direct activity stimulated by the expansion is likely a major benefit to the County. The indirect and induced employment impacts created from the direct development of the park expansion represents a mix of service-related and performing arts jobs, clearly providing adjacent neighboring areas with more employment opportunities than would otherwise exist. The table below estimates the top 5 employment sectors in each development scenario which would be created at build-out of the Austin Tindall Park expansion, resulting from the direct effects of on-going operations (see Figure 15).

Figure 15. Top 5 Employment Sectors (Low, Moderate, and High Scenario)

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants.

Tax receipts may include any combination of local, state, and federal taxes which accrue to Osceola County. In this analysis, GAI calculated the discrete collections or levies associated with direct property taxes and direct tourist taxes, and relied on IMPLAN to provide taxes on imports and productions for personal property taxes and other taxes associated with the Austin Tindall Park expansion in each development scenario.

As previously referenced, GAI found that between 24% to 40% of annual visitors are estimated to require overnight accommodation. Based on data collected from Osceola County, Experience Kissimmee, and the case study research, our analysis assumes that overnight visitors are estimated to spend between $80 and $160 per person per night, and typically consist of 1 to 3.1 persons per room. These values were applied to the projected annual visitors in each

Figure 16. Total Taxes Paid (Low, Moderate, and High Scenario)

development scenario to calculate the total daily overnight demand. Specifically, we assumed overnight demand is driven mostly by hotel/motel guests for the type of sporting events and activities which take place at Austin Tindall Park.

Based on our inspection and additional research of property tax data from the Osceola County Property Appraiser, we estimated the value per hotel room to be about $150,000. Applying these values to the total overnight demand, we were able to estimate the property tax on lodging which the County could potentially accrue. In addition, we applied a 6% tax on direct spending on lodging to calculate tourist taxes.

The following table illustrates the estimated taxes which could be accrued to Osceola County for each development scenario (see Figure 16).

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants.

Our analysis and findings on the economic and fiscal impact of the proposed expansion of Austin Tindall Park in Osceola County, based on generalized data with local adjustments, suggest that there could be very significant impacts. Given the nature of the impacts, it is appropriate to support the expansion of Boggy Creek Road with tourist tax dollars. While we are inclined to adopt the moderate scenario for planning purposes, there are reasons to believe the high scenario could be a plausible, if not conservative, reference point—in effect, this region has a much larger and more integrated

than several of the case studies. As a result, there are many more local outlets, such as restaurants, drinking establishments, retail shops, other entertainment alternatives, and proximate destinations which may stimulate and capture the elevated direct spending which would occur. Unlike most of the case studies, Osceola County has a highly evolved marketing system in place that heavily promotes substantial tourism activity, much of it targeted towards organized or sanctioned events that can be identified, planned, and quantified.

Agha, Nola. (2013). The Economic Impact of Stadiums and Teams: The Case of Minor League Baseball. Published by the Journal of Sports Economics, Vol. 144, No. 3, pp. 227-252. DOI: 10.1177/1527002511422939.

Agha, N., & Taks, M. (2015). A Theoretical Comparison of the Economic Impact of Large and Small Events. Published by the University of San Francisco, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 199-216. Available at: https://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1004&context=sm.

Graham et al., Graham, R., Ehlenz, M., & Han, A. (2021). Professional Sports Venues as Catalysts for Revitalization? Perspectives from Industry Experts. Published by Journal of Urban Affairs. DOI: 10.1080/07352166.2021.2002698.

Harnik, P., & Crompton, J. (2014). Measuring the total economic value of a park system to a community. Published by Managing Leisure, Vol. 19, Issue 3. DOI: 10.1080/13606719.2014.885713.

Keane et al., Keane, L., Hoare, E., Richards, J., & Bauman, A. (2019). Methods for quantifying the social and economic value of sport and active recreation: a critical review. Published by Sport in Society Journal, Vol. 22, No. 12, pp. 1-26. DOI: 10.1080/17430437.2019.1567497.

Lee, Soonhwan. (2008). A Review of Economic Impact Studies on Sporting Events. Published by The Sport Journal. Available at: https://thesportjournal.org/ article/a-review-of-economic-impact-studies-onsporting-events/.

Lindsey et al., Lindsey, G., Man, J., Payton, S., & Dickson, K. (2004). Property values, recreation values, and urban greenways. Published by Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 69-90. Available at: https://headwaterseconomics.org/trail/43-propertyrecreation-values-urban-greenways/.

Matheson, Victor. (2018). Is there a Case for Subsidizing Sports Stadiums? Published by the College of Holy Cross, Department of Economics. Available at: https:// web.holycross.edu/RePEc/hcx/HC1814-Matheson_ FavoringStadiumSubsidies.pdf.

Song et al., Song, H., Dwyer, L., & ZhengCao, G. (2012). Tourism Economics Research: A Review and Assessment. Published by Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 1653-1682. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2012.05.023.

Sungsoo, Kim. (2020). Assessing economic and fiscal impacts of sports complex in a small US county. Published by Tourism Economics, Sage Journals, Vol. 27, Issue 3. DOI: 10.1177/1354816619897151.

Veltri et al., Veltri, F., Miller, J., & Harris, A. (2009). Club Sport National Tournament: Economic Impact of a Small Event on a Mid-Size Community. Published by Recreational Sports Journal. DOI: 10.1123/rsj.33.2.119.

Wilson, Rob. (2006). The Economic Impact of Local Sports Events: Significant, Limited, or Otherwise? A Case Study of Four Swimming Events. Published by Managing Leisure, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 57-70. DOI: 10.1080/13606710500445718.

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants. Notes: Totals may not add due to rounding.

Sources: IMPLAN Group; GAI Consultants. Notes: Totals may not add due to rounding.