Time, Wilderness & Ownership

Desire to Turn Away from the Immutable Chronological Framework

The Abandoned House

The Tent Transparency, Superimpositions & The Distance

The Digital Nomad

Sites

Foundations

Scale & Shape

Materiality

Skin Design Users

Time, Wilderness & Ownership

Desire to Turn Away from the Immutable Chronological Framework

The Abandoned House

The Tent Transparency, Superimpositions & The Distance

The Digital Nomad

Sites

Foundations

Scale & Shape

Materiality

Skin Design Users

François-Mathieu Mariaud de Serre

M.Arch Thesis Project

Advisor: Andrew King

Co-Advisors: David Theodore & Theodora Vardouli

Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture

Fall 2021

Keep it Movin’ is an original essay, speculation, and project, about fundamentals of motion in lifestyles, tools, and architecture. It is structured in seven chapters of varied thoughts illustrated in the first two alternating partitions. The analytical and anthropological observations are translated at the end of each chapters into elements of assemblage, for an architectural artifact. The speculation being constructed throughout the study builds up towards a project, synthesized in a third conclusive partition.

Why can we comprehend movement as a post-capitalist probable global outcome, nay desire, based on elements of history and identity?

How can we manifest the speculation of motion throughout an architectural artifact?

sanguine - france - 610

Introduction

1. Kinetic energy is defined by the Britannica Encyclopaedia as a form of energy that an object or a particle has by reason of its motion. If work, which transfers energy, is done on an object by applying a net force, the object speeds up and thereby gains kinetic energy. Kinetic energy is a property of a moving object or particle and depends not only on its motion but also on its mass. The kind of motion may be translation (or motion along a path from one place to another), rotation about an axis, vibration, or any combination of motions.

It is a question of seeing in the Nomad, a spontaneous human, closer to his environment than any other, one who will dwell in a space, a time. It is an affiliation to the kinetic energy of a body. 1 Nomadism is defined by the Larousse French dictionary as a way of life characterized by the movement of human groups to ensure their survival.2 It is also known that since the Paleolithic era, outside of our knowledge and technology, humanity has always lived in a nomadic fashion. Far from ownership and far from the constructionists that we are today, the unfolding of movement and its tangible processes requires an interpretation by analogies.3 These bridge theories of motion, and their need, with interposed speculative elements of an architectural artifact in construction.

Keywords: Mobility, Nomadism, Ownership, Space, Time, Wilderness

1. Britannica Encyclopedia (2021)

2. French Larousse dictionnary (2021)

“Welcome my son, welcome to the machine. What did you dream?

Nowadays, owners and some elites devastate wilderness, pulling the strings of a sedentary westernized world with capitalist streams. Humanity urbanizes by extending cities with further rigid private spaces, a requirement of comfort and lifestyles that have evolved.5 It is acknowledged that more and more new hybrid forms of housing, and secure private residences, question the way we interact with others.6 It shows how we poorly respect our environment (i.e., Climate Change), and how we poorly respect our human nature. Housing bound to lifestyle calls for constant renewal. One that is still distant from the most fundamental realities.7

A mobile architecture as a sublime dynamic form of housing for today and tomorrow’s nomads responds to this perpetual reconstruction: a bottom-up strategy that wishes for a romanticized worldwide ecstasy, and integrity, unachieved by our current social growth model. It is a strategy and communication inspired by “Speculative Everything Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming”.8 Nomads of today are perceived here as a marginalized society in this now and post-urban wilderness, composing at the same time, promise of future and return of an ancient past.

7.

8.

It’s alright we told you what to dream.”44. Pink Floyd - Welcome to the Machine, Roger Waters (1975). 5. Junger, Ernst (1963). Le mur du Temps. Paris: Gallimard. 313 p. 6. Wright, Frank L. (2013). La ville évanescente. Editor: Infolio. Traduction de Claude Massu. 170 p. Sorkin, Michael (1992). Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space. Hill and Wang. 272 p. Dunne, Anthony & Raby, Fiona (2013). Speculative Everything Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Editor: MIT Press. 240 p.

Originally, nature was used as a habitat, as a dwelling place (e.g., Caves, Tree Trunks, Dwelling Below, Troglodytes, and Craters that were used as shelters) so that humanity could protect itself from the elements. Either the primitive resources at hand made it possible to build a shelter to preserve oneself, or nature itself served as the architect.

Bernard Rudofsky evokes the principle of a spontaneous architecture that adapts and takes full advantage of the contextual characteristics of its environment. It meets the functional and practical needs of a community.9 The building methods depicted here by Rudofsky deserve to be described as Mari Lending outlines Stendhal’s inherent crystallization of dissolved minerals, as the transformation of a natural objet trouvé into pure beauty.10 So to speak, Stendhal’s description of this chemical process was intended to be an illustrious metaphor for love. A wooden branch would be thrown in the distance, a distance now depicted by the roads, in a mine and be covered in sparkling magnificent salt crystals after a period.11

The pure delicacy of a spontaneous architecture compared to the wooden branch thrown in Stendhal’s crystallization, witnesses the potential and the value of being so close to your environment. A symbiosis,

9. Rudofsky, Bernard (1964). Architecture without Architects. Editor: New York: The Museum of Modern Art. 157 p.

10. Lending, Mary & Zumthor, Peter (2018). A feeling of History. Zurich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess. 80 p.

11. The beauty and the power of the most trivial object, all of its phenomenological interactions, beyond the built environment. It’s about a greater Critical Regionalism (Kenneth Frampton, 1983), also more than the use and the function. It starts to think about how architects can begin by not building buildings.

Fig 2. Social crisis emerging from the shifting of time to speed. Pandolfi, Mariella (1999). Corps nomade, mémoire nomade. Dans La mémoire des déchets : Essais sur la culture et la valeur du passé. Montréal : Éditions Nota Bene. 245 p.

love, and respect for the space that welcomes beings. Thus, it is an act far, very far from how space and time are lately translated, piloted by Berners’s 1989 World Wide Web as its sublime vehicle, as space and speed, increasing several social crises. A hazardous speed that is nonetheless regulated on the roads. 12 13

12. Debray, Régis (1996). Qu’est-ce qu’une route? in Les cahiers de médiologie. Paris: Gallimard. 318 p.

13. The roads, and parking lot were defined as a site for the contemporary nomads after a conversation with the architect Natalie Lafortune who suggested the close consideration of this new landscape that emerged from moving vehicles.

Fig 3. The Zoetrope recognizes space and time while it is put into motion at an adequate speed (v1) It allows us to see and understand the movement of the figure (person walking) on the surface. It places it in our minds with our senses and constructs an assimilated interpretation.

Fig 4. The Zoetrope, with the transfer of speed (v2). Here, time becomes speed (v 2 > v 1) While we ignore other superposed drawings, it seems to our eyes that the figure starts to be in motion. Yet, the figure is static on the surface. A remarkable likeness to sedentary lifestyle enclosed in a machine. A constructed illusion.

1.1. The road

Def: A route for traveling between places by vehicle, one that has been specially surfaced and made flat: a gravel/dirt/ paved road. (Cambridge)

Plan. Standard road dimensions

Section. Typical pavement road system (Landcaster, OH)

Asphalt Surface Asphalt Binder Aggregate base course

fabric

Def: An outside area of ground where you can leave a vehicle for a period of time. (Cambridge) Parking lots as sites answer to the analogy of time, wilderness, and ownership. They are stops in motion. They can be translated into limits traced inside and leading, to the elsewhere. Flat roads and parking lots make us think of shared yet owned drawn deserts of asphalt, dust as seen in Nomadland (2020), movement enabled by plane surfaces. They refer to the playground for kinetic energy, a vehicle that is empowered with resources increasing its speed between lines and boundaries. These limits are because of a context that we seek to protect and preserve. The site can be read between powerful white painted lines.

Aervoe® Vers-A-Striper Line Striper, 20 oz.

Def: At, in, from, or to another place or other places; anywhere or somewhere else. (Cambridge) The elsewhere is all of the flat places accessible. The degree of abstraction is kept by the routes of all possible in all landscapes. «Earth, Water and air» (p.23).

Australia. 2400 x 5400 Canada. 2700 x 5200 Japan. 2100 x 5100 South Africa. 2500 x 5000 UK. 2400 x 4800 USA. 2700 x 5400

Standard formats of parking lots are flexible painted lines between continents that depend on heritage.

Shared or private, free, and priced property lines for a time, they can have their own hours of accessibility. They articulate the interdependence of the object and its contextualization. The dimensions of a page format, a portrait, or a landscape. The fundamental triviality, yet needed of white painted lines in an urban or unbuilt environment. Perpendicular, parallel, and at an angle, accesses to a parking lot below:

Def: Walmart Inc. is an American multinational retail corporation that operates a chain of hypermarkets.

As seen in the movie Nomadland (2020), Walmart stores allow RV to spend the night on their property with permission from a store manager. It is a scalable reality in North America. It is also scalable in the artifact itself, in number and in length. On the side: artifact dimension scalable on site.

The Nomad knows instinctively then intuitively the function of the space with which he or she is presented to build his or her habitat. Today, there is an undeniable social and economic dimension in the double field of public space and habitat, inherited from structuralist and capitalists’ streams.14 They insidiously defined our current sedentary lifestyles and systems. Likewise, private rigid motionless structures spreading in suburbs today, adjacent to rural soils, respond to the notion of how we are affected by ownership and what we share. To help narrow the scope towards an architecture being able to move, this housing renewal involves a deeper unfolded understanding of nomadic ways of sheltering. We will look at their purposes, their systems, and their correlation with time and sites.

“Man is above all nomadic, not sedentary. He is nomadic for reasons of survival, he moves to hunt, gather, reproduce, find water or a quieter place than the one he is in and from which he is simply driven away.”15

The concept of mobility and a nomadic shelter nowadays: what does it imply? Mobile in space, immobile in time, the Nomad is not an owner. Nature as its changing environment is its best ally; he or she adapts to it for a given time but will always have to leave it.

Compared to the Nomad and his or her simple needs, the inflexible way we accommodate today unequivocally questions the horizontally and vertically privatization of public and shared space in their wilderness. We are unsuccessfully respecting them by constantly adding constraints, with overloaded self-reflection and complexity, and in a less natural adequation.16

There’s room enough to ask now if an architecture being in motion inspired by the Nomad’s primitive and instinctive behaviors can be a sustainable and durable counter model to our perpetual reconstruction. A model that is outside of a real estate market and for future speculation.

The magnified vision of dwelling for tomorrow’s revolution asks for open and flat sites, flexible programs, and a scalable series of intentions in the object itself. It is nonetheless about how can it have a moving foundation in the first place? A moving architecture is looked at with an exchange between

the analytical theory of movement in different time periods and with the undeniable desire for motion, an escape that provides the limitless options of space and visual relationship.

The research is influenced by the evocative, spiritual, and playful ways of sculpting explored by Arthur Ganson in small assemblages. It is also affected by Paul Klee’s «Pensée Créatrice» and his theory of dynamics in shapes and drawings.17

“What was there in the beginning? The objects moved freely, so to speak, without following a determined path, neither straight nor curved. We have to imagine them as pure mobility; they go where they go, with the only purpose of going, without a precise destination, without a will, without obeying anything, simply with the evidence of moving, the original state of the mobility of objects. It is a given: from this original state, mobility is a preliminary condition of the evolution”18

This architecture is understanding the Nomad body as a physical object fleeing the standards and institutions that participate in organized repression of our now urbanized, owned, and domesticated built environment. 19

Against these normalized urban models nourished by an ontological point of view based on the body, an architecture that can move in space draws a line of resistance for the imprisoned beings, aside and inside of white traced lines. The organization of our modern life is indeed seen, as a sclerotic, socially controlled system that mainly serves an elite that sometimes lacks abnegation. Yet, it is this same elite that unfairly domesticates nature and adapts it to the needs and desires (e.g., National Parks).20 It is a critic of an understanding of space and time that has had slowly, digitally, and capitalistically been translated in space and speed; a speed that ignores the distance, the coincidences seen in the last chapter. Here, the distance traveled is a mean, it is indeterminate, it is only the idea of all possible routes, the will to turn away from the immutable. It is in all the continents of the world that the dwellings of the indigenous environments have drawn these preurban trajectories. Shared or kept heritage, beliefs, customs, and chances have shaped the different types of sheltering for nomadic people. They were able to move with kinetic energy suggested by their body, other species and animals, or tools for the most mechanically optimized tribes and people. Their way of sheltering links the dynamic and diverse spaces resulting from their movements, a distance traveled, with the contemplated, visual, and

20. Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness; or, getting back to the wrong nature. In W. Cronon (Ed.), Uncommon ground: rethinking the human place in nature (pp. 69–90). Norton. 562 p.

geometric spaces. Nevertheless, the main unit that allows us to classify these dwellings is time that will be look in more detail in the next chapter: ephemeral, episodic, periodic, seasonal, semi-permanent, and permanent.21

It is a matter of seeing time as the main gear in the metamorphosis of nature and its elements, to the shelter around the world. The sensual phenomenon is brought by the raw and minimal essence of what is spontaneously found. Here, the wheel becomes the contemporary tool for traveling and turning forward a metamorphosis of nature in front of our eyes: the minimal impact of observing and being. Appearing in 8000 B.C, the wheel has been the ever-revolving answer to the need and ambitions of human societies in traveling.22 The car has forever been an analogy to the house and has always had a strong relationship with kinetic energies, time, and speed.23

“Ingres is said to have introduced order into the inactivity. I would like, beyond the pathos, to introduce order in the movement.”

(Paul Klee,1914)Fig 11. The Wheel, The Footprint & The Diagonals in texture and superimpositions

Def: A circular object connected at the centre to a bar, used for making vehicles or parts of machines move.(Cambridge)

Def: The frame of a vehicle, usually including the wheels and engine, onto which the metal covering is fixed. (Cambridge)

The importance of the balance of forces; gravity, weight (a), and counterweight (a’). There is the fundamental, importance of horizontality and verticality.

Put into perspective, the wheel becomes an object, a symbol that puts forces together with a center point of attractivity and balance.

2.1. The wheelSketchs research for a wellstructured and flexible trailer.

Def: A structure that holds the parts of an object in position and gives them support.(Cambridge) The structural frame has been carefully designed to leave as much space as possible in between the structure. It allows great resistance to weight while being on wheels.

Def: The flat surface of a room on which you walk.(Cambridge)

A secondary structure made of C Channels permits addition of a thick layer of plywood. The flat surface is elevated and the frame is still contained in a 2100x4800 rectangle. Adequate with today’s standards.

The examination of how long into time these architectures are framed builds a first background data for our understanding of the shapes, the materiality, and the structures in which nomads were able to move in space. A chronological framework of these instinctive architectures addresses profound questions of time and temporality across spaces and mobility. Their shape and scale are affected by their needs and customs.

The transitory constructions are essentially composed of natural, degradable resources (e.g., Branches, Young Shoots, Grass...) destined to be used for only a few days. In the form of small huts with circular plans, the screens are in harmony with their environment. The African Bushmen or the Australian Aborigines who live from hunting and gathering take shelter from the wind in these more intimate dwellings, when they are not gathered around the fire in the middle of the camp.24 The huts of the Pygmy people, with their woven branch structures covered with large leaves, imitate the bird that shapes its nest, according to the movements of its body. Although, it is known that the constructions of traditional cultures are designed more by the body, muscles, and their movements, than by the eye.25

24. Hadzabe Hut Building - Amazing Traditional House from Natural Materials. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m2LJDIhjXC4&ab_ channel=NomadArchitecture

25. Pallasmaa, Juhani (2010). Le regard des sens. Editor : Linteau. Translated by Mathilde Bellaigue. 110 p.

26. Jousse, Marcel. (1969). L’anthropologie du geste. Paris : Resma Edition. pp. 207. 395 p.

“Indeed, we know the world only through the gestures we inflict on it by receiving its presence. It is a kind of tragic duel, so to speak: the world invades us from all sides and we conquer the world with our actions. And then we throw our triple bilateralism into the cosmos. And this is the great mechanism of Sharing. There is the right and there is the left. There is the front and there is the back. There is the top and then there is the bottom and in the center there is a human who does the sharing. This is the setiform structured world with only our hands! The tri-fold hand, in a body that oscillates symmetrically. This is one of the things in the problem of knowledge.”26

Sheltering in different continent, through time & lifestyles

Nomadic hunting and gathering, following wild plants and game available in season, is the oldest method of human subsistence.

Pastoralists raise, drive, or move with herds in patterns that normally avoid depleting pastures beyond their capacity to recover.

Itinerant

Itinerant nomads offer the skills of a craft or trade to the sedentary populations among whom they travel. They are the most common nomadic peoples in industrialized countries.

Towards the use of several weeks, the episodic dwellings are characterized by more sophisticated techniques. They have a much more consequent effect on the environment. The tribes hunt and fish, these men dig and use fire for their buildings and for burning on the land, an early form of agriculture.27 The Indian teepees evoke a more intimate relationship with technology and the use of new resources such as animal skins. Then, there is the cultivation and establishment of collective dwellings and hierarchical patterns within the more complex tribes; the Iroquois longhouses, the Wai Wai communal houses, the Inuit spiral igloos which can be grouped together.28

On the other hand, the Inuit tupiq in summer, demonstrates an increasingly adaptive technique and behavior that differs from the basic circular plan known until then. Building systems are evolving and progressing: the Piaroa collective house, which now has primary and then secondary structures, is evolving from a simple dome. Moreover, nomadic people evolve and move in all types of environments and terrains: this is the case of the Dayak tribes of Sarawak who live in longhouses on the water.29

Over a certain period, semi-nomadic communities settle somewhere for a long time, due to agricultural activities. The tribe sometimes owns the land,

27. Marcel Mazoyer : l’abattis-brûlis, une des premières formes d’agriculture. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXrNNarfaaE&ab_channel=TerrEthique

28. Découverte d’une maison longue iroquoienne par télédétection. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CZjV4hy5nq0&ab_channel=Forumenclips

29. Village Lifestyle in Iban Longhouse, Malaysia by Asiatravel.com. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_3xl1dvvdoM&ab_channel=AsiaTravelTV

settles there for long months, sometimes for years, and cultivates it until the land lies fallow or even runs out, and leave in respect of cycles. Their habitat is semi-permanent. These dwellings, which can be found among the Masai, Kikuyu of Kenya, or the Navajos of North America, are generally built from rough local materials such as dried bricks, straws, or branches. It gives information on the shapes and the scale they were able to build based on the found materials conditions.

Today, modular shacks are used to house travelers, such as the Romani. Associations like Ava in France have found simple ways to accommodate them temporarily.30 This is indeed a social act, and as the architect Yona Friedman says, the social act is in fact the distribution of a stock that must be limited. The architecture of survival is, therefore, essentially a tool for survival. Friedman says that architecture, which has become a discipline, has forgotten its role as a tool and must rediscover it.31

Before being a tool, an object is a simple object, and casting it serves as a game at the start. One goes to the point where it falls, picks it up, and thus marks out one’s path. When you get up again, you become aware of the route you have taken, and you measure the distances. The scalable object then becomes the measuring tool of the first Nomad.

31.

Def: A set of numbers, amounts, used to measure or compare the level of something. (Cambridge) Here, the prototype is scalable because of the nature of its materials and the will to be suitable for the maximum of situations.

Def: The particular physical form or appearance of something. (Cambridge)

The trailer has its own scalable proportions, it has number of variations while following the same structural frame. The chronological framework depicts that the roof is the shelter and the ground gain again its natural function as a surface with respect to its variations.

The architectural artifact is superimposed with architectures from different period, vehicles, and living elements. It amalgamates the ideas of proportions and the ideas of shapes (i.e., line, circle, the oblique) in plan and section. The dimensions given here are exacts, or generalization of minimal variable heights. 0

The Abandoned House is both the place that has lived and the place that takes its strongest expression stripped of its inhabitants, its families, its couples, or its widow. It is the ruins that will remain. A future promise. It is only itself, damaged. It is also its broken parts, its fractures that make it an incomplete piece inviting the Nomad to justly use, complete, or prolong the Abandoned House in time. It speaks about reuse, sustainable speculative cycles. The spirit of the Nomad makes it his or her own, it speaks to its body, it waits for the Nomad to use it in every possible way.

It is also a fascinating piece of interest for the many photographers that freeze in time these houses that have lived and become useless, isolated.32 Because we do not take care of them, the structure abandoned in time is deformed and may deform the urban landscape. They become wild, sometimes frightening by their precariousness, and melting into the nature that will invade them. They become the scene of unsanitary squat and will eventually collapse. The abandoned house is a place that observes the world go by. But it is also a project, a source of materials.33

It is not a place to welcome, it has already been.

It is part of the path; it is in motion since it is no longer what it was.

It creates time for the one who comes. These houses serve as another analogy of time and ownership, the last remaining ruins of a story, from which we move on. The question is to know how these abandoned houses could not be rehabilitated, nor restored, but serve as a corner, for rest certainly, but also as a device to remain in the dynamics of the path. It stays in the walk of the Nomad and its fluidity and serve the basic needs of material resources.

A bit like a rule: no comfort, but instability in what it gives and what it gets. These houses can be shelters themselves in the first place. The oblique is seen as this new ritual of motion. We can read them in their new diagonals, falling pieces, a new ramp that links the ground to the shelter, inspired by Claude Parent for whom:

“The oblique function does not begin anywhere and never ends. The ground of reference of the Earth is not an obstacle to its development since the ramp is the structural element that makes two spaces communicate in continuity while they are inscribed in different natures - water and earth, earth, and sky - without interruption of the nature of the support.”34

These houses would become devices in the making, of unstable nature, that the bodies espouse all the better in their movements. It is thus a question of understanding the structure of these giving houses to use them in the second place for the artifact, subtracting objects of passage, fabrics, tarps, wood, steel frames... It answers to a pragmatic incapacity to lodge but also to enunciate a new symbol in the act of giving, as a potential of movement and change. The abandoned house is at the beginning and at the end of motion. A premise for other and different uses, and at the end of its scenario and function. An incredible source of fascination.

Def: A physical substance that things can be made from. (Cambridge)

Abandonned houses become the playground of mobile architecture. It starts by understanding the conditions of particular situations along the way and it leads a variety of scenarios, all unique in time and space.

On the right: System boundary diagram of harvesting wood and architectural salvage from a house.

When we talk about survival architecture, we of course think of makeshift shelters with rigid walls, mobile homes, and blue tarpaulins. Outside of the tiny house dimensions, romance, and optimization linked to real estate markets, the tent seeks to answer to more primary instincts towards which we should strive again. This architecture owes a lot to nomadism, which seeks simplicity through the removable and transportable shelters that are tents, with their multiple forms and functions. They are found in all parts of the world, except for the Aborigines of Australia and Southern Africa. The tent is a dwelling whose flexible walls are extended. The tension of the fabric ensures the stability of the covering and the rigidity of the frame like the Arab tent. This is an iso static system. In general, poles, often sculpted and painted with geometric figures, support a pole, and form an elementary framework on which rests a piece of fabric fixed to the ground. It is sewn and made of several woven or assembled strips, sometimes comprising up to forty sheepskins among the Tuaregs. Sometimes the tent does not fall to the ground and allows the air to circulate, sometimes it is fixed flush to the ground to protect it from the wind.

Or the opposite, the tent has a rigid frame that simply supports the skins. This is a hyper static system.

The comfortable Yurt can be erected and dismantled in half an hour. It is cylindrical in shape, covered with straw mats and topped with a cupola covered with pieces of felt. Its frame is made of a multi-piece lattice, joined by leather laces that allow the whole to be folded when the tent is dismantled. The diameter of the Yurt can be up to seven metres, and its walls are about one and a half metres high. The Tibetan tent, which is supported by a thick, onemetre-high wall of earth and grass, is rectangular in shape. It is made of extremely strong yak hair fabric. The frame is held together by several ropes decorated with small, coloured papers to ward off evil spirits. Next are the conical tents of Lapland or North America. They are built of birch or fir poles resting on hoops of naturally curved branches. This frame is covered with coarse horse, reindeer, or buffalo blankets, which are attached to it by leather straps. The round tent of the Tchoukchis is double conical, the roof of which rests on a circular wall. Three sacred poles form a tripod pole. Moreover, the placenta of each child born is topped by three sticks bound into a cone and covered with a piece of leather.35 Man is to the tent what the tent is to the world.

Def: The natural outer layer that covers a person, animal, fruit, etc. (Cambridge)

The skin is made of tarpaulin, the one available. Thickness and colors are variable. It is attached and fixed to custom-made aluminum pieces that help take care of the materials.

It is put in tension from both lateral sides. The metal rods help bear the wind forces.

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

2 x 5 mm diam. metal rod

custom c shaped steel piece

5 mm diam. metal rod

7mm hex bolt

lateral 0.28 mm silver tarp

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

2 x 5 mm diam. metal rod

variable air «buffer zone»

30mm plywood

45/45mm aluminum C Chanel

110/200mm I aluminum beam

head custom aluminum piece

30mm plywood

7mm hex bolt

45/45mm aluminum C Chanel

lateral 0.28 mm brown tarp

L shaped steel welded to bracket

110/200mm I aluminum beam

“We can consider the world either as the actual space of our life or as a hilly canvas on which the images of things are painted from a distance. In this second aspect, it is only to the eye; it is made up of simultaneous parts. [...] Empiricism relies mainly on muscular sensations to show that space is not a primitive datum of experience, but that it presupposes certain temporal series whose original characteristics we must interpret to construct the representation of the simultaneous.”36

Gyorgy Kepes in “The Language of Vision” defines transparency as perceiving several spatial layers simultaneously.37 It creates a rhythm that transforms our perception into discontinuity. Everything becomes a movement. This mobility that we find in the vanishing traces of travelers is there, in the folds and folds of the façades that metamorphose. There are nesting, assemblages, and diagonals which, through the combinatory play of light, extract themselves from a depth.

Nomadic architecture makes us think about the way we approach an architectural project and about the notion of space. A space in which we should constantly move.

All these superimpositions, this organization where a whole device of simultaneity plays the orchestra, lends itself to collage, an expression of a state of mind that encourages the politics of bricolage, a practice that implies the study of infinite limits. It is the heritage of human aspirations.38 Form calls for form, as it is assembled.

36. Lavelle, Louis (1921) La perception visuelle de la profondeur. Strasbourg: University of Strasbourg, pp. 29. 79 p.

37. Kepes, Gyorgy (1968). Signes, Image, Symboles. Bruges: La connaissance, les presses Saint-Augustin. 238 p.

38. Louis Lavelle (1921)

The Nomad, looking skywards:

“I take in the sky full of stars with a single glance Even with the naked eye, I roughly grasp the similarities and differences of the figures formed by the stars in the various regions of the sky. Isn’t there a geometry gathered in the moment?”39

Space is certainly defined by the elements that serve to delimit it, such as walls, doors, windows, curtains. Space is what is in between, it is also everything that isn’t owned or domesticated. It is the passages between two layers, volumes within volumes, superimpositions that create transparencies. It belongs only to the visitor, or better still, to the inhabitant who experiences it from the inside.

Architects have been looking at these small capsules, shelters to the scale of the body, even cities that can move at another scale.

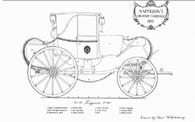

The study of nomadic architecture being able to move in time participate in a conversation. The long-lasting cult of mobile tools to travel distances, instinctive but pragmatic. All within the spectrum of available materials, customs, and rhythm. We seek to find here an overview of how nomadism is reflected through its shapes, symbolism, structures, and materials, in old and recent eras. The function

1. Dugout Canoe

2. Domesticated horse

3. Details of Napoleon’s Military Carriage

4. Leon Serpollet, Peugeot

5. Almere House/ Benthem&

6. Dymaxion House, Buckminster Fuller

7. RAPIDO, Constant Rousseau

8. Walking City/ Ron Herron

9. Plug-in City/ Peter Cook

10. Gasket Homes/ Warren

11. Capsules/ Warren Chalk

12.

13.

14.

isn’t a matter. Between the lines of a machine, the world, the scene stays in motion. It is an orchestra, a metamorphosis in which anyone can play a part and engage with what is found. Elements of design only allow flexibility and adaptability. The one lasting function of a mobile architecture belongs in the alternative.40

A glance is not enough, it is the repetition that makes the lines and walls dynamic. The lights move. The gaze is at the center of a new, dynamic space. A centre that moves, from one point to another, with motion, in all the design elements. These serve as secondary ergonomic tools.

Always between the terrestrial and cosmic domains, human beings inevitably travel. Either substantially or ethereally, a human’s physical impotence and the mobility of its spirit lies in duality within. The sublime tragedy of the spiritual.41

40. Mobility is nothing but the possibility and all the alternatives, available roads. It is flexible: it doesn’t have to move but it can. It is public and everywhere.

41. Paul Klee (1914)

Def: To stop something from being active, either temporarily or permanently. To hang something.(Cambridge)

The plywood at the top of the assemblage serves as a structure from which elements of design can be suspended. There is movement in the suspension. With distance and scalability, we find the superimpositions and rhythms in the perception of this new space.

Def: A number, amount, or situation that can change: (Cambridge)

The variability depends on what is found on the way, all of its changing elements. What is there to be found?

It is totally subjective and context-dependent. The everchanging context is also entirely dependent on if the shelter needs to move. It takes the time it needs. A subjective selection of furniture that is found in my thoughts is drawn here.

Isometric. Variable elements found along the way

«Utopians hate roads because they lead somewhere else», says François-Bernard Huygues.42 The Nomad is the one who escapes from modern utopias, whether it is the intellectual city linked little by little to the augmented human, or the original garden nourished by new communities, to find nature and its benefits.

Outside of political refugees, homeless, travelers, nomad tribes, and itinerants, who are the users of such a lifestyle in our westernized world? Why, and how is there a will to escape out of the frame? An in or post-pandemic reaction or a digital, less analog experience?

The modern nomad has undergone a housing crisis, a work crisis. The increasingly fragmented family unit favors mobility. The loss of religious values resulting from rottenness is also one of the causes of modern nomadism. Distrust of educational institutions and failure at school is leading parents to turn to alternative voices, e-learning, where the screen becomes the teacher of choice. The screen is another phenomenon, but a compelling tool with overloaded digital information for the spirit. Yet, it excludes completely the art of a body in motion. Modern life, from metaverse to organics, is sending

42. PhD in political science and HDR, is president of the Strategic Information Observatory (OSI) and director of research at Iris (cyberstrategy, influence...).

out new signals which, until a decade ago, were very weak. Humanity, since self-reflection emerged, knows how to recognize a variety of signs that he or she learns to perceive and interpret, to orient their self in a world that is itself moving and changing by nature. The Nomad is the first to reject the systems of symbols42 imposed and structured by the new authorities, for a well-defined social order, with its laws, codes, transactions, and electronic enclosures. The nomads are then looking for new codes, new signs, new symbols that connect them to a more natural rhythm, from one point to another, excluding themselves from the «outside» of the city-bubbles, and from any miniaturization.

72% would trade their home for van life to pay off debt.

52% are more likely to consider van life due to COVID-19.

35% would like to be outdoor more.

35% would be in their van by the beach.

24% would try it for more than two years.

7% wouldn’t consider it.

The Nomad goes towards the great, the infinite of the road, he or she becomes small as nature expands in front of the body, and suddenly all around it. This shrinking of his or her condition converges with a growing autonomy of the Nomad. They organize their journeys, within an imposed road system, but also along paths imposed by nature itself, forcing the Nomad to self-build, interfering with the builders of the cities.

The Nomad makes the road a receptacle for new symbols to be conquered43, starting with a floor that becomes the roof through which he or she certainly shelters him or herself, but also through which he or she signifies growing up outside the world.

Def: Someone who uses a product, machine, or service.

(Cambridge)

The mobile architecture lives through its users. They are the ones to manipulate and act the change in any context. The use and design are thus, contextdependent.

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

2 x 5 mm diam. metal rod

variable air «buffer zone»

30mm plywood

45/45mm aluminum C Chanel

110/200mm I aluminum beam

Section. Longitudinal

Asphalt Surface

Asphalt Binder

Aggregate base course

Drainage

Separation fabric

Subgrade

This part of the project introduces the architectural artifact as an improved architecture. It brings it to a plausible use for the nomads of tomorrow. A comfortable envelope, operable openings for interior light and passive ventilation, as well as heat and furniture are added for an optimized use. It engages the same structure and skin used by previous users. It moves in different sites and orientations, within the same generic grid.

wheel. (700 x 700)

stairs. (L. 1500 x W. 285 x H. 200)

windoor. (W. 775 x H. 1981, window: 630 x 630)

fixed bench. (L. 1045 x W. 430 x H. 475)

mobile stool. (L. 485 x W. 430 x H. 450)

murphy table. (L. 1100 x W. 470 x H. 950)

operable skylight. (L. 720 x W. 645)

wood-burning insert. (L. 520 x W. 355 x H. 955)

double sized bed. (L. 2040 x W. 1420)

operable window. (L. 564 x W. 385)

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

vented air space

16mm osb sheating

19mm horinzontal straping

air barrier & waterproof membrane

70mm wood fiber insulation

air barrier & temp. wrb

30mm plywood

45/45mm perf. aluminum C chanel

110/200mm I aluminum beam

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

head custom aluminum piece

22mm head diam. bolt

lateral 0.41 mm brown tarp

vented air space

16mm osb sheating

19mm vertical straping

air barrier & waterproof membrane

60mm wood fiber insulation

2x30mm plywood

22mm head diam. bolt

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

head custom aluminum piece

110/200mm I aluminum beam

windoor: ( door: W. 775 x H.

1981, wood framed window: 630 x 630)

lateral 0.41 mm brown tarp

25x85mm aluminum handrail

25mm plywood

air barrier & waterproof membrane

2x50 wood fiber insulation

30mm plywood

wood framed operable skylight (L. 720 x W. 645)

aluminum sheat

vented air space

22mm head diam. bolt

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

custom 120x50mm wood stud

air barrier & waterproof membrane

30mm plywood

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

vented air space

16mm osb sheating

19mm horinzontal straping

air barrier & waterproof membrane

70mm wood fiber insulation

air barrier & temp. wrb

30mm plywood

16mm osb sheating

19mm vertical straping

air barrier & waterproof membrane

70mm wood fiber insulation

air barrier & temp. wrb

19mm vertical straping

30mm plywood

80mm diam. chimney

45/45mm perf. aluminum C chanel

15mm ceramic

15mm plywood

110/200mm I aluminum beam

60 mm diam. tube beam (chassis)

700mm diam. wheel

30mm plywood

2x50mm wood fiber insulation

50/100 aluminum C chanel

air barrier & waterproof membrane

30mm plywood

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

vented air space

16mm osb sheating

19mm horinzontal straping

air barrier & waterproof membrane

70mm wood fiber insulation

air barrier & temp. wrb

30mm plywood

45/45mm perf. aluminum C chanel

110/200mm I aluminum beam

top 0.41 mm brown tarp

head custom aluminum piece

22mm head diam. bolt

lateral 0.41 mm brown tarp

vented air space

16mm osb sheating

19mm vertical straping

air barrier & waterproof membrane

60mm wood fiber insulation

2x30mm plywood

22mm head diam. bolt

30/90mm wood stud

air barrier & waterproof membrane

30mm plywood

wood framed operable window (L. 564 x W. 385)

aluminum sheat

22mm head diam. bolt

76x122mm wood stud

air barrier & waterproof membrane

30mm plywood

lateral 0.41 mm brown tarp

16mm osb sheating

head custom aluminum piece

folded 0.41 mm brown tarp

bottom 0.41 mm brown tarp

22mm head diam. bolt

110/200mm I aluminum beam

30mm plywood

air barrier & waterproof membrane

2x50mm wood fiber insulation

50/100 aluminum C chanel

30mm plywood

50x300mm wood bed support

The flexibility of the shelter, whom answers to the most basic needs for now, lies in its panel assemblages. Inspired by the prefabricated module architecture, as well as the train wagon connexions, the streching of the architectural artifact enable multiple prototypes. These, strating to take upon diverse architectural strategies and complexity can be started to be ennounced as RV trailers for the nomads of tomorrow, free of all ownership.

Maximum streching size on site: 10400mm

Systematic repetition of the architectural artifact.

Six different options based on the section variations in different site orientations.

Irregularity of the systematic modules on the grid.

Impermanence of the artifacts. They come and leave in time with an engined vehicle able to move it with traction.

With space and distance between the livable trailers, openings are poked in lateral panels.

In semi-permanence, bridges connect adjacent artifacts, and openings are placed in more optimized positions.

This new complexity in within allows better adaptation. It answers to a larger spectrum of needs.

The architectural artifact becomes a village with time. Following different dispositions, it proposes a large variety of possibilities. Thus, all of the connexions are designed for assembly and desassembly. The village metamorphoses in accordance with its contexts, and to the most basic needs of its users, in permanence and impermanence. It depends on all sources of energy and will find its meaning in motion, within, and elsewhere.

For A. P Elkin, the aborigines were unable to place iron in their beliefs and rituals and therefore did not understand to which global system this new material belonged.45 The use of iron was at the origin of the loss of ancient values, and it was undoubtedly a material unsuited to the thought and memory of these people, as Rudolf Arnheim would say, even if they discovered its use through its handling.46

In 1973, Marc Le Bot posed the problem in these terms: «Is the city of the machine age the place where could be accomplished the desire of acceleration and perfect accomplishment of the social exchanges? Or is it the place of their un personalization by abstraction for the benefit of a system to which the binarism stated by Mondrian and van Doesburg imposes a mark like the logic that will be that of electronic computers?»47

The machine and the screen becoming this way of divinity, leads us to wonder about its impact on our own values, certainly, but on the harmony that connects us to our systems.

According to Heinz Von Foerster, «an organism that is in harmony with its environment possesses, in

45. Elkin, P (1968). Les aborigènes d’Australie, Collection Bibliothèque des Sciences humaines. Paris: Gallimard. 451 p.

46. Arnheim, R. (2004) Visual Thinking University of California Press; Second Edition.

352 p..

47. Le Bot, Marc (1973). Peinture et Machinisme. Paris : éditions Klincksieck. 259 p.

48. Von Foerster, H. (2003). Understanding Systems: Conversations on Epistemology and Ethics. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 158 p.

one way or another, an internal representation of the order and regularities of this environment. »48

We are certainly not talking about an organism here, but about a device that considers a necessity and a vitality dear to our human nature: movement and impermanence. Impermanence, the Nomad in his or her fluidity and detachment, tames it, dominates it. He or she is its custodian, he or she creates intervals, time, between the stages and in the displacements. Immobility lets time escape, the machine devours time, and to generate time today, is a luxury for us all.

Far from these architectures that consume the space we have left; it is necessary to speculate on autonomous architecture; «independent of the function and the container of a building, and that the goal is to make it free of any tangible relation with its use».

This architecture would aim at the harmony between the desire of the man of passage, the environment, and the situation of the moment. To quote Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky:

«Isn’t the politics of tinkering a practice that involves the study of infinite limits, the legacy of human aspirations? »49

49. Rowe, Slutzky (1992). Transparence réelle et virtuelle, Paris, Les éditions du demi-cercle. 95 p.

A mobile place, a place that is pulled and then dropped, a place that is borrowed, a place that is lost, a place that traces, a place that is destined, a place that is shared, a place without address. A place from place to place, a place that connects. A place that comes and goes, that swings, a place in permanent becoming, a place that never stops changing and changing itself. A naked place, and not really. A place without an owner, an opened place. A place for memory, for moving on to something else, to another part. A place of a part of oneself and of another. A place that is interwoven with the time of the nomad who explores, who transforms the place itself. A place that can be touched and retouched... a place that can be tinkered with. A chariot of fire.

Throughout the writing of this illustrated essay, I have received an amazing deal of support and assistance.

I would first like to thank my supervisor, Andrew King, whose expertise and flexibility were invaluable drivers in exploring inventive ways to illustrate my thoughts. Thank you for the space and time allowed to «move» between the bridges of speculation. Your insightful feedback pushed me to sharpen my methodology and brought my work to a higher level of communication.

I would also like to thank David Theodore and Theodora Vardouli for letting me pursue this subject, and for discerning questions at critical times.

I would like to acknowledge close friends, Sofia, and colleagues from McGill University for stimulating discussions as well as happy distractions to rest my mind outside of my research.

In addition, I would like to thank my family for their incredible support and compelling conversations along the semester.

Aitchison, Mathew (2017). “A House Is Not a Car (Yet)”, Journal of Architectural Education, 71:1. pp. 10-21.

Arendt Hannah (1958). Chapters 11& 12, The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press. 380 p.

Arnheim, R. (2004) Visual Thinking University of California Press; Second Edition. 352 p.

AVA – Habitat et Nomadisme. (2002). Pôle habitat. Online: http://www. avahabitatetnomadisme.org/

Bidault, Jacques & Giraud Pierre (1946). L’Homme et la Tente. Paris: J. Susse. 338 p.

Borella, Jean (2015). Penser l’Analogie. Paris: Harmattan. 228 p.

Bouchain, Patrick (2006). Construire autrement: comment faire? Arles: Actes Sud, pp. 13. 190 p.

Britannica Encyclopedia (2021)

Bulliet, Richard (2016). The Wheel: Inventions and Reinventions. Columbia University Press. 272 p.

Cambridge Dictionary (2021)

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness; or, getting back to the wrong nature. In W. Cronon (Ed.), Uncommon ground: rethinking the human place in nature. Norton. pp. 69–90 562 p.

Debray, Régis (1996). Qu’est-ce qu’une route? in Les cahiers de médiologie. Paris: Gallimard. 318 p.

Dunne, Anthony & Raby, Fiona (2013). Speculative Everything Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Editor: MIT Press. 240 p.

Elkin P (1968). Les aborigènes d’Australie, Collection Bibliothèque des Sciences humaines. Paris: Gallimard. 451 p.

Forde C Daryll (2013). Habitat Economy and Society: A Geographical Introduction to Ethnology. 520 p.

Frampton, K. (1983). Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance, in The Anti-Aesthetic. Essays on Postmodern Culture Hal Foster, Bay Press, Port Townsen. 173 p.

French Larousse Dictionary (2021)

Friedman, Yona (1978). L’Architecture de Survie. Belgium: Casterman. 171 p.

Illich, Ivan (1977). Disabling Professions, London: Marion Boyars. 370 p.

Jousse, Marcel. (1969). L’anthropologie du geste. Paris : Resma Edition. pp. 207. 395 p.

Junger, Ernst (1963). Le mur du Temps. Paris: Gallimard. 313 p.

Kepes, Gyorgy (1968). Signes, Image, Symboles. Bruges: La connaissance, les presses Saint-Augustin. 238 p.

Klee, Paul (1973). Écrits sur l’art. 1, La pensée créatrice. Paris: Dessain et Tolra. 556 p.

Lavelle, Louis (1921) La perception visuelle de la profondeur. Strasbourg: University of Strasbourg, pp. 29. 79 p.

Le Bot, Marc (1973). Peinture et Machinisme. Paris éditions Klincksieck. 259 p.

Lending, Mary & Zumthor, Peter (2018). A feeling of History. Zurich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess. 80 p.

Mazoyer, Marcel : l’abattis-brûlis, une des premières formes d’agriculture. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXrNNarfaaE&ab_channel=TerrEthique

Marocco Joe (2008). “Climate Change and the Limits of Knowledge.” The Virtues of Ignorance, The University Press of Kentucky. 307 p.

Meadows, Donella H. (2008). Thinking in Systems. Chelsea Green Publishing. 240 p. National Center for Environmental Health – Healthy Housing Reference Manual, Chapter 1: Housing History and Purpose. (2009) Visited Online 2021.

Nicod, Jean (1924). La géométrie dans le monde sensible. Paris: Librairie Félix Alcan. pp. 120-121. 174 p.

Pallasmaa, Juhani (2010). Le regard des sens. Editor : Linteau. Translated by Mathilde Bellaigue. 110 p.

Pandolfi, Mariella. (1999). Corps nomade, mémoire nomade. Dans La mémoire des déchets : Essais sur la culture et la valeur du passé. Montréal : Éditions Nota Bene. 245 p. Parent, Claude & Virilio, Paul (2004). The Function of the Oblique. UK: AA Publications. 72 p.

Waters, Roger (1975). Pink Floyd - Welcome to the Machine

Proctor Robert N. (2008). Agnotology: A Missing Term to Describe the Cultural Production of Ignorance (and Its Study),” in Proctor, Robert, and Londa L. Schiebinger. Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance. Stanford University Press.

Roberge, Gabrielle (2014). « Habiter l’inhabituel : le nomadisme comme posture artistique dans les oeuvres de Jacques Bilodeau, d’Ana Rewakowicz et de JeanFrançois Prost » Mémoire. Montréal (Québec, Canada), Université du Québec à Montréal, Maîtrise en histoire de l’art. 168 p.

Rowe, Slutzky (1992). Transparence réelle et virtuelle, Paris, Les éditions du demicercle. 95 p.

Rudofsky Bernard (1964). Architecture without Architects. Editor: New York: The Museum of Modern Art. 157 p.

Sorkin Michael (1992). Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space. Hill and Wang. 272 p.

Tapie, Guy (2014). Sociologie de l’habitat contemporain: vivre l’architecture. Marseille : Parenthèse. 237 p.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2009). National Center for Environmental Health – Healthy Housing Reference Manual. 231 p. Online 2021 https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/publications/books/housing/housing_ref_manual_2012. pdf

Villeneuve Johanne; Neville, Brian; Dionne, Claude (1999). La mémoire des déchets, Éditions: Nota bene, Fonds (sciences humaines). 246 p.

Von Foerster, H. (2003). Understanding Systems: Conversations on Epistemology and Ethics. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 158 p.

Wright, Frank L. (2013). La ville évanescente. Editor: Infolio. Traduction de Claude Massu. 170 p.

It is a question of seeing in the Nomad, a spontaneous human being, closer to his environment than any other, one who will dwell in a space, a time: it is an analogy to the kinetic energy of a body.

Their way of living is characterized by a self or a group movement in forsaken places to ensure survival. It is also known that since the Paleolithic era, outside of our knowledge and technology, far from ownership and far from the constructionists that we are today, humanity has always lived in a nomadic fashion. This thesis is looking at the historical lessons we can learn from this lifestyle and how we can think about new countermodels, not buildings, to propose a gateway to the perpetual reconstruction involved by current practices. The reasoning is depicted through an illustrated essay entitled Keep it Movin’ divided into seven chapters: Time, Wilderness & Ownership, Desire to Turn Away from the Immutable, A Chronological Framework, The Tent, Transparency, Superimpositions & the Distance, The Digital Nomad, The Abandoned House.

Each of these evocative parts written and drawn by anumber of anthropological, architectural, and pictural references, decorticates aspects of the Nomad condition: Site, Foundation, Scale & Shape, Skin, Design, Users, Materiality.

Motion, distance, time, and ownership being the main concerns, the thesis pulls out a thorough interest in trying to introduce order in the movement.

Thus, the chapters become seven elements putting together an speculative architectural artifact: a vehicle dwelling in parking lots, unknown places, and roads leading to somewhere else.

François-Mathieu Mariaud de SerreM.Arch Thesis Project

Advisor: Andrew King

Co-Advisors: David Theodore & Theodora Vardouli

Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture McGill University Fall 2021