Chapter Five: Environmental Risk Management

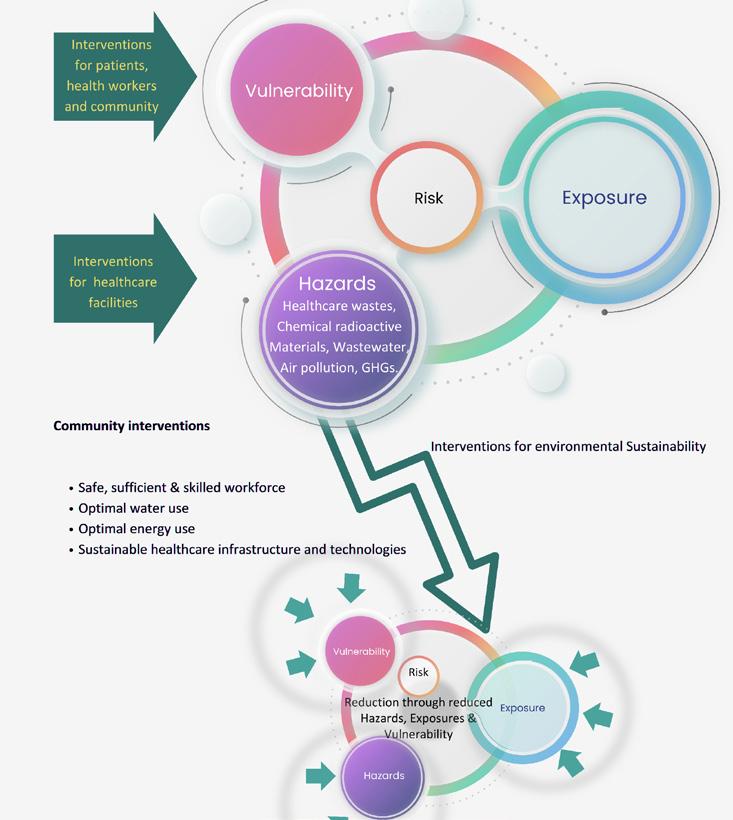

Environmental risk management and sustainability are critical components of modern healthcare sectors.

These sectors consume substantial amounts of energy and water and generate a considerable amount of waste and GHC.

As a result, healthcare sector has a significant environmental impact and vastly contributes to climate change and therefore have a responsibility to identify and mitigate environmental risks associated with their operations. This includes assessing potential hazards and developing strategies to minimise negative impacts on the environment. Environmental risk management in healthcare involves identifying sources of pollution, waste generation, and harmful emissions, and implementing measures to control and reduce these risks.(65)

The adoption of sustainable practices by healthcare sector is essential to promote the long-term wellbeing of both human health and the environment, through reducing the negative impact on the environment, promote cost savings, and improve its public image. Sustainable healthcare practices encompass a wide range of strategies, including reducing energy and water consumption, minimising waste generation, and implementing sustainable waste management practices, adopting green building design, and promoting environmentally friendly procurement practices.(66, 67)

Energy efficiency plays a vital role in sustainable healthcare with dual benefits: mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and achieving significant cost savings.(68) The inherent energy intensity of healthcare facilities, driven by the continuous operation of medical equipment, climate control systems, and lighting, emphasises the urgency of adopting measures to curtail energy consumption.

Strategic initiatives include the incorporation of advanced technologies designed for energy efficiency, retrofitting buildings with improved insulation to enhance thermal performance, optimising lighting systems to minimise electricity use, and incorporating renewable energy sources into the energy mix. These measures align with the World Health Organisation’s recommendations from 2009, emphasising the critical role of energy conservation in reducing the environmental footprint of healthcare operations.

Beyond environmental considerations, the economic implications of energy reduction strategies are substantial, with cost savings allowing for the reallocation of resources to core healthcare services, ultimately development a more sustainable and resilient healthcare infrastructure.

Integration of renewable energy sources holds promise in transforming the healthcare sector into a more environmentally conscious entity. The deployment of solar panels, wind turbines, and other renewable technologies can significantly contribute to the generation of clean and sustainable energy within healthcare facilities.

This transition not only lessens reliance on fossil fuels but also positions healthcare institutions as models for eco-friendly practices. Embracing renewable energy not only aligns with global efforts to combat climate change but also exemplifies the healthcare sector’s commitment to sustainable development.

Framework for Building Climate Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities

Waste management is another crucial aspect of sustainability in healthcare. Proper management of healthcare waste, including hazardous materials and pharmaceuticals, is essential to prevent environmental contamination.

Applying waste segregation, recycling programs, and safe disposal methods can minimise the impact of healthcare waste on ecosystems and public health.(69) Furthermore, sustainable building design and infrastructure contribute to the overall environmental performance of healthcare facilities.

Environmental Sustainability in Health Care Facilities

Green building practices focus on reducing resource consumption, improving indoor air quality, and utilising eco-friendly materials. Incorporating elements such as natural lighting, efficient water usage, and green spaces can create healthier environments for patients, staff, and the surrounding community.(68)

In ambulance sector, environmental management plays a crucial role in minimising the impact of ambulance operations on the environment.

As the front line of emergency care providers, ambulances contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and have an opportunity to adopt sustainable practices that can reduce their carbon footprint. Research indicates that each ground ambulance response in Australia is estimated to produce approximately 22 kg of CO2 emissions. This emission rate has significant implications when considering the scale of ambulance operations nationwide.

Sustainability in Ambulance Services

Annually, this translates to an estimated range of 216,369 to 546,688 tonnes of CO2 emissions produced by ground ambulances alone in Australia.(70, 71)

The magnitude of these emissions highlights the importance of addressing environmental impact within the ambulance sector. The emissions from ambulances represent a notable portion of the total carbon footprint of the Australian health sector, accounting for between 1.8% and 4.4% of the sector’s overall emissions.(71)

To minimise the environmental impact of ambulance operations, several strategies can be implemented.

One approach is to transition to greener and more fuel-efficient vehicles. This involves adopting hybrid or electric ambulances that produce fewer emissions or utilising alternative fuels such as biodiesel.

Vehicle maintenance and optimisation of routes can also contribute to reducing emissions and fuel consumption. Moreover, implementing eco-driving techniques and training programs for ambulance drivers can lead to more efficient driving practices, further reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Additionally, reducing idle time during ambulance responses and adopting energy-efficient equipment can contribute to lowering the carbon footprint of ambulance operations.

Furthermore, organisations within the ambulance sector can engage in sustainability initiatives, such as monitoring and tracking emissions, setting emission reduction targets, and implementing energy-saving measures in ambulance stations and facilities The use of renewable energy sources and energy-efficient technologies within ambulance facilities can help to decrease the environmental impact.

Environmental Policy Development and Sustainability

To avert the most severe health consequences of climate change, a decisive reduction in global emissions by half is indispensable by 2030, ultimately culminating in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. (10)

The mounting evidence of climate change has prompted nations to markedly enhance their climate commitments. The United States, for instance, recently pledged to slash emissions by 50–52% below 2005 levels by 2030, positioning itself on a trajectory towards net zero by 2050. Similar heightened commitments have been observed from Japan, Canada, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and South Korea, with the G7 collectively agreeing to cease financing new fossil fuel projects.(72)

Presently, many nations, representing over two-thirds of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 72% of global emissions, have established some form of net-zero emissions target.(70) If these commitments translate into tangible actions, the projected global temperature increase by 2100 is anticipated to fall within the range of 2.0–2.4 °C. While sustained efforts are crucial, the goals set in the Paris Agreement appear to be within reach.(73)

Environmental policy development and sustainability are critical issues that have become increasingly relevant in recent years.

Environmental policies are the guidelines, principles, regulations, and laws that govern the actions of individuals, organisations, and governments with regards to the environment. Sustainability, on the other hand, refers to the ability to meet the present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Environmental policy development involves the formulation of policies, strategies, and regulations aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of human activities on the environment. These policies aim to protect the environment by controlling pollution, conserving natural resources, and promoting sustainable development.

Within Australia, there is an evident and expanding support for robust climate leadership (74). Public expectations are on the rise, with a widespread anticipation that the federal government should at least align its ambition with that of countries such as the UK and the US. Despite Australia’s recent commitment to a net-zero by 2050 target, the nation is often perceived as a climate laggard, contributing to the erosion of diplomatic credibility.(75)

Criticism from Pacific Island states and the United States has been voiced, and Australia ranks last for carbon and energy policy in the 2021 Sustainable Development Report.(76)

Nevertheless, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) underscores Australia’s unique economic advantage in the context of global decarbonisation due to abundant renewable resources.

Paradoxically, Australia is confronted with economic vulnerabilities and climaterelated challenges in a world undergoing both warming and decarbonisation.(77) (78)

The absence of a coherent national strategy and delayed action have resulted in missed opportunities, compelling Australia onto a steeper emissions reduction path to achieve net zero by 2050.(79) With carbon pricing becoming integral to global trade, Australia’s carbon-intensive export industries face unease, particularly with the European Union implementing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) in 2023–26, and the United States and China contemplating carbon tariffs.(80)

Health systems emerge both as contributors to and potential mitigators of the climate change predicament.(81-83)

Approximately 7% of Australia’s carbon emissions stem from its healthcare system, a figure equivalent to the entire emissions output of South Australia.(84) This compares with a global average of 4.4%, and figures of 6% and 10% in the UK and US, respectively.(85)

Health systems play a pivotal role in safeguarding populations from health threats resulting from climate change impacts, including rising temperatures and extreme weather events.

Thus, health systems occupy a unique position as both contributors to the climate change problem and key entities responsible for managing its health ramifications. Recognising this dual role, the World Health Organisation’s Special Report for COP offers an extensive overview of the health impacts of climate change, delineates the health co-benefits associated with climate action, and presents ten high-level recommendations for concerted action.(86)

Sustainability is at the core of environmental policy development in Australia as the country grapples with a range of environmental challenges, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

In Australia only, climate change resulted in exacerbating extreme weather events in the last decades. Heatwaves, hurricanes, floods, droughts, and wildfires have become more frequent and intense, causing widespread devastation to natural and human systems alike.

Environmental policy development in Australia has been driven by the recognition of the profound impacts of environmental degradation on human health and wellbeing.

Australia’s Climate has Warmed Since National Records Began in 1910. The Oceans Surrounding Australia have also Warmed.

Data Source: Bureau of Meteorology, ERSST, v5, www.esrl.noaa.gov

Environmental Policy Development and its Impact on Human Health in Australia

The environmental policies that were implemented by the Australian government include the National Environment Protection Council (NEPC), the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), and the Renewable Energy Target (RET).

Loss of Potential Habitat for Threatened Species, Migratory Species, and Threatened Ecological Communities

Dark blue represents compliant loss (or loss that occurred with a referral under the EPBC Act) and dark red represents non-compliant loss (or loss that occurred without a referral under the EPBC Act). Three panels highlight the southern Western Australia coast (left), Tasmania (middle), and northern Queensland coast (right). Source: Ward M. et al. Conservation Science and Practice (2019).

National Environment Protection Council (NEPC)

The NEPC stands as a crucial intergovernmental entity in Australia, tasked with the responsibility of safeguarding the nation’s environmental integrity.

Established to oversee the quality of the Australian environment, the NEPC operates through the development and implementation of national environmental standards. These standards, outlined in collaboration with state and territory governments, address a spectrum of environmental concerns, ranging from air and water quality to pollution control and waste management. In the context of human health and sustainable development, the NEPC plays a pivotal role in setting benchmarks that ensure the wellbeing of both the populace and the environment. For instance, the NEPC’s air quality standards are specifically crafted to regulate pollutant concentrations in the atmosphere, aiming to secure clean and healthy air for the Australian population.(87)

The air quality standards established by the NEPC are instrumental in mitigating health risks associated with air pollution. These standards actively contribute to the prevention of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases through delineating permissible levels of pollutants like particulate matter and ozone.

The careful regulation of air quality aligns with broader public health objectives and underlines the commitment of the Australian government, as reflected in the Commonwealth of Australia’s 2015 document, to fostering a sustainable and health-conscious living environment. Consequently, the NEPC serves as a cornerstone in Australia’s environmental governance framework, orchestrating collaborative efforts to ensure that environmental standards are not only met but also optimised for the holistic wellbeing of the nation’s citizens.(87)

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation ct 1999 (EPBC Act) holds utmost significance in the legal framework of Australia, as it plays a pivotal role in safeguarding the nation’s biodiversity and ensuring ecological sustainability.

Enacted to address and mitigate the potential adverse impacts of development activities on the environment, the EPBC Act places a particular emphasis on the conservation of threatened species and ecosystems, as outlined by the Department of Agriculture, Water, and the Environment. Beyond its immediate environmental focus, the Act holds broader implications for human health and wellbeing through its commitment to preserving biodiversity.

Biodiversity preservation is a cornerstone objective of the EPBC Act due to its recognition of the intricate linkages between ecosystems and human welfare. Biodiversity supports crucial ecosystem services that are indispensable for human survival, encompassing functions such as water purification, soil fertility maintenance, and climate regulation.

Decision tree outlining the referral process under the EPBC Act 1999

Source: Adapted from Australian Government, 2013.

The Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, in 2015, highlighted the pivotal role of biodiversity in securing clean water, nutritious food, and a stable climate— essential components for human health.

Therefore, the EPBC Act, by championing the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems, indirectly contributes to the enhancement of human health by ensuring access to these fundamental ecosystem services.(87, 88)

Within the broader context of environmental sustainability, the EPBC Act aligns with the RET policy in Australia. The RET policy seeks to bolster the utilisation of renewable energy sources by establishing a target of 33,000 gigawatt-hours of renewable energy by the year 2020.

Together, EPBC and RET legislative measures form a framework for the protection and management of Australia’s biodiversity, environment, and energy resources, reflecting a holistic approach towards sustainable development and the wellbeing of both the nation and its inhabitants.(89)

Renewable Energy Target (RET)

The RET in Australia is a comprehensive policy framework designed to promote and increase the share of renewable energy in the country’s electricity generation.

The primary objective of this initiative is to transition the energy sector towards cleaner and more sustainable sources, thereby reducing reliance on traditional fossil fuels and addressing environmental concerns, such as air pollution and climate change.(90)

The RET’s target of achieving 33,000 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electricity generation from renewable sources by the year 2020 is a crucial milestone that reflects the government’s commitment to fostering a more sustainable and environmentally friendly energy landscape. The policy operates by encouraging the development and deployment of renewable energy projects across various technologies, including solar, wind, hydro, and bioenergy.

To incentivise participation and investment in the renewable energy sector, the RET employs a system of Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs). These certificates are granted to renewable energy generators for each megawatt-hour of electricity produced and can be sold to liable entities, such as electricity retailers, who are obligated to acquire a certain percentage of their electricity from renewable sources.

The implications of the RET extend beyond the scope of energy production.

They also have significant impacts on human health and the environment. One of the most notable benefits is the reduction of air pollution. Traditional energy sources, particularly those based on fossil fuels like coal, contribute to air pollution through the release of pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter.

Australian GHG Emisssions MtCO2e/year

Through increasing the proportion of electricity generated from renewable sources, the RET helps decrease the emission of these harmful pollutants, leading to improvements in air quality and subsequently promoting better respiratory health among the population.

Climate targets of major Australian political parties and independent candidates, with historical emissions (grey), including from the land use, land use change and forestry sector (dark grey). The bar on the right indicates compliance with different temperature targets. Source: Climate Analytics. https://climateanalytics.org

The RET plays a crucial role in mitigating climate change.

The combustion of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere, contributing to the greenhouse effect and global warming. This increase in using renewable energy helps reduce the carbon footprint of the energy sector, contributing to national and global efforts to combat climate change. This, in turn, has broader implications for public health, as climate change itself poses various risks to health, including the spread of infectious diseases, heat-related illnesses, and disruptions to food and water supplies.

All together, Australia has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2030. The transition to renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, leading to improved air quality and reduced respiratory ailments. The substitution of fossil fuels with renewable energy also mitigates climate change, which has far-reaching consequences for human health, including the spread of infectious diseases, food security, and mental health impacts.(91)

Climate Action Goals Across State and territory Governmments

Chapter Six: Health Policies, Commonwealth Initiatives and State Disparities

Within the Commonwealth, the Australian Government has officially ratified the Paris Agreement, a commitment made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

This commitment necessitates parties to consider the ‘citizen’s right to health’ as an integral part of their national response to climate change.

In alignment with this Agreement, Australia has pledged to achieve an economy-wide emissions reduction target, aiming for a 26–28% decrease below 2005 levels by 2030.

Additionally, the nation is obligate to contribute financial support to the Green Climate Fund, amounting to $100 billion annually. Notably, Australia has not made any contributions to the fund since 2019.(92) Contrary to federal ambitions, recent reports indicate that state and territory energy policies, combined with household initiatives such as the installation of rooftop solar, are positioning Australia for emissions reductions ranging from 37–42% below 2005 levels.

Commonwealth Department of Health Programs

Presently, the Commonwealth Department of Health lacks specific programs addressing the intersection of climate change and health.

Funding for research in this domain is limited and predominantly comes from highly competitive grants offered by the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Although there are several NHMRC Centers of Research Excellence, none have been established specifically focusing on climate change and health. However, a one-off $10 million Special Initiative in Human Health and Environmental Change was granted in 2021.(58, 93)

Adaptation funding has experienced a decline, notably seen in the reduction of funds allocated to the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF) from $50 million over 5 years to a mere $9 million during 2014–2017, with no further funding allocated since 2018. While the Department of Health articulates a vision of ‘better health and wellbeing for all Australians, now and for future generations,’ it is noteworthy that climate change is absent from Australia’s Long-term National Health Plan. Moreover, it is not designated as a national health priority.

Although the draft National Preventive Health Strategy acknowledges climate change, its commitment to developing a national environmental health strategy by 2030 is deemed insufficient, considering the urgency and magnitude of the climate crisis. The absence of coordinated efforts and leadership from the Commonwealth on climate change and health has led to varying policies across state and territory jurisdictions, indicating a lack of a cohesive and organised approach in dealing with the complex issues arising from the intersection of climate change and health. This absence suggests there may be no clear direction or overarching plan to comprehensively tackle the health impacts of climate change.

Australian Jurisdictions’ Policies

The decentralisation of decision-making and policy implementation related to climate change and health across different state and territory jurisdictions can have several implications, both positive and negative.

While decentralisation allows for tailored approaches that consider local nuances and priorities, it may also give rise to challenges. One significant concern is the potential lack of consistency and uniformity in addressing climate-related health challenges. Each jurisdiction may adopt its own strategies, priorities, and timelines, leading to a fragmented response to the health risks associated with climate change. This lack of coherence can hinder the development of a comprehensive, nationwide approach to mitigating climate-related health issues.

The decentralised nature of policymaking also opens the door to a patchwork of policies, regulations, and initiatives. Different regions may implement varied measures to address climate change’s impacts on health, potentially creating confusion among the public, stakeholders, and even healthcare professionals. This lack of standardisation could impede efforts to communicate and educate the public about climate-related health risks and appropriate preventive measures.

Furthermore, the absence of a unified approach may hinder collaboration and information sharing between different jurisdictions. Effective responses to climate-related health challenges often require coordinated efforts, shared resources, and knowledge exchange. A decentralised system might struggle to facilitate the necessary collaboration, slowing down the implementation of effective strategies and interventions.

Climate Change and Australias Healthcare Systems

While permitting flexibility to address local needs, it is imperative to establish overarching principles, guidelines, and goals at the national level. This approach ensures a more coherent and synergistic strategy in dealing with the health impacts of climate change, minimising confusion, and optimising the effectiveness of public health initiatives throughout the entire country. A summary graphic of major climate policies and emissions targets across Australian jurisdictions is presented, with detailed tables available in Appendix 2.

Chapter Seven:

Public Health and Sustainability

Public health and sustainability are interlinked concepts crucial for fostering a healthier future for our planet.

In the face of numerous health and environmental challenges, the need to address these issues through a sustainable and comprehensive approach has never been more urgent.

Public health, at its core, aims to enhance the wellbeing of communities, an objective directly hindered by the environmental unsustainability we currently face. The degradation of sustainability impacts human health in various ways, from air and water pollution to climate change, food insecurity, and environmental toxins.(94)

How Climate Change Affects Population

The negative consequences of human activities on Earth’s environment have come back to affect humanity itself. While public health efforts, such as disease prevention and health promotion, contribute to sustainability by reducing the burden of diseases and disabilities, they can also impose a significant negative impact on the environment.

Source: Created by Cindy Klein-Banai, based on Climate change and human health: Present and future risks McMichael, A. J. et al. (2006). Lancet, 367, 859-869.

PM footprints for health care in selected countries in 2015

(A) PM footprint for health care in each country.

(B) PM footprint per capita.

(C) PM footprint of health care as a percentage of the country’s total PM footprint.

(D) PM footprint per US$. Countries are ordered according to their national health-care expenditure.

Left axes and blue columns show PM footprints; right axes and red columns show health-care expenditure. Shades of blue represent direct (dark blue), first-order (mid-blue), and second-order (light blue) supply-chain contributions. These national estimates are affected by uncertainties of between 15% (large countries) and 40% (small countries). PM=particulate matter.

Source: Lenzen M, Malik A, Li M, Fry J, Weisz H, Pichler PP, Chaves LS, Capon A, Pencheon D. The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2020 Jul 1;4(7):e271-9.

Public Health Waste Production

Public health systems generate substantial medical waste. Improper disposal and incineration of medical waste can lead to pollution of water, soil, and air, posing risks to wildlife, ecosystems, and human health, and contributing to climate change.

Such, this waste includes infectious materials, hazardous chemicals, radioactive substances, and general waste. Healthcare facilities generate approximately 5.9 million tonnes of waste annually, with about 20% being hazardous.

For example, the disposal of unused or expired medications poses a significant environmental risk, as improper disposal can lead to contamination of water sources, affecting aquatic life.(95, 96)

Pharmaceuticals route to a body of water and bioremediation technologies

Source: Ortúzar M, Esterhuizen M, Olicón-Hernández DR, González-López J, Aranda E. Pharmaceutical pollution in aquatic environments: a concise review of environmental impacts and bioremediation systems. Frontiers in microbiology. 2022 Apr 26;13:869332.

Breakdown of energy consumption by major fuel and usage type Chapter Seven: Public Health and Sustainability

The public health system’s contribution to waste generation includes a significant number of single-use items like disposable gloves, masks, and other personal protective equipment, which contribute to sustainability degradation.

The increased use of single-use items during the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this problem.(97)

These items, often made of nonbiodegradable plastics derived from fossil fuels, contribute to littering, pollution of natural habitats, and harm to wildlife.(98)

Source: Bawaneh, Khaled, Farnaz Ghazi Nezami, Md. Rasheduzzaman, and Brad Deken. 2019. Energy Consumption Analysis and Characterization of Healthcare Facilities in the United States Energies 12, no. 19: 3775.

Environmental footprints of health care (2015) Chapter Seven: Public Health and Sustainability

The impact of health care is shown as a percentage of total impact, for the world (segments) and selected countries (spokes), in terms of greenhouse gas emissions (global total=54·4 Gt CO2e), particulate matter (122·2 Mt), NOx (161·9 Mt) and SO2 (167·3 Mt) emissions, malaria risk (113·1 million people),28 nitrogen to water (79·0 Mt),29 and scarce water use (483·9 TL).24 Spokes represent data for the USA (U), Japan (J), the UK (G), Brazil (B), China (C), and India (I). Direct (lightest shade), first order (middle shade), and supply-chain (darkest shade) refer to impacts caused by health care directly, by health care’s immediate suppliers, and the remainder, respectively. CO2e=carbon dioxide equivalent. Gt=gigatonnes. Mt=megatonnes. NOx=nitrogen oxides. SO2=sulphur dioxide. TL=teralitres.

Lenzen M. et al., The Lancet Planetary Health, 2020, 4(7), e271-e279.

Public Health Energy and Water Usage

Healthcare sectors are energy-intensive operations, relying on electricity for lighting, heating, cooling, transportation, and medical equipment.

The reliance on fossil fuels contributes to air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and the depletion of finite natural resources.(99, 100)

Additionally, the healthcare sector’s significant water usage, coupled with inadequate water management, can contribute to water scarcity, especially in regions like Australia, where water resources are limited. The discharge of untreated or improperly treated wastewater from healthcare facilities can pollute water bodies and harm aquatic ecosystems, further impacting environmental sustainability.(100)

Anaesthetic Gases in Healthcare

Anaesthetic gases, including nitrous oxide, sevoflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane, play a pivotal role in medical procedures, but their impact on climate change is a critical concern within the healthcare sector.

Estimates of their impact on climate change vary widely, ranging from 0.01% to 0.1% of overall global greenhouse gas emissions.(101) Nitrous oxide, with a warming potential about 300 times greater than CO2, significantly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions when released during medical interventions. Desflurane, with an extraordinarily high global warming potential, exceeds that of CO2 by several thousand times. The release of these gases not only poses immediate environmental risks but also exacerbates the broader issue of climate change.

Global efforts to address the environmental impact of anaesthetic gases are gaining traction. Some countries and healthcare institutions are actively working to reduce their carbon footprint associated with anaesthesia through strategies like adopting more environmentally friendly agents, improving waste gas capture systems, and advancing anaesthetic delivery technologies to minimise emissions.

Key atmospheric parameters for nitrous oxide and halogenated anaesthetic gases

IPCC AR6=International Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report. NA=data not available. ppb=parts per billion. WMO=World Meteorological Organisation. *Recommended by the authors. Source: Sulbaek Andersen et al., (2023). The Lancet. Planetary health, 7(7), e622–e629.

Case study: Middlemore Hospital, New Zealand

In New Zealand, the primary anaesthetic gases employed are sevoflurane and desflurane. Halogenated ethers typically administered alongside oxygen, nitrous oxide, or a combination of both. Over 95% of administered anaesthetic gases are released into the atmosphere. The adoption of liquid anaesthetics isn’t a feasible substitute, as nearly half of these liquid anaesthesia drugs end up in landfills, contributing to environmental pollution and posing a significant risk of water contamination.

Scientists from the University of Auckland have pioneered an innovative approach. They have devised a novel adsorptive and hydrothermal deconstruction method, utilising hot, pressurised water to break down anaesthetic waste. This process transforms the waste into safe, inert compounds, primarily water, and organic acids like acetic acid. The implementation of this method is projected to slash emissions in New Zealand by 20,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually, while also preventing the release of 5,000 litters of liquid anaesthetic waste into the environment each year.(102)

In another successful initiative, New Zealand has emerged as a leader among developed nations in its campaign to phase out Desflurane, an exceptionally potent greenhouse gas extensively used in surgical procedures. Desflurane surpasses CO2 in potency by several thousand times, contributing significantly to environmental concerns. Remarkably, since 2014, New Zealand has made substantial strides in reducing its carbon footprint associated with volatile anaesthetics, including Desflurane, achieving an impressive 95% reduction.

The current annual usage of Desflurane in New Zealand is a mere 40 tonnes, a sharp contrast to England’s consumption of 40,000 tonnes. This accomplishment underscores New Zealand’s dedication to addressing environmental issues and embracing sustainable practices within the healthcare sector.(103, 104)