AGRICULTURE AND THE EUROPEAN UNION, A

FORWARD-LOOKING ROADMAP

European agricultural production will be key to a more prosperous, more sovereign European Union, responsibly preparing its legacy for future generations.

The European Union must put itself in a position where it can rely on agriculture:

- to strengthen its food sovereignty, to maintain the EU as a powerful player on international markets, and to be able to meet the supply needs of a fast growing bioeconomy,

- to provide sustainability solutions for itself and for economic sectors that will not be able to achieve carbon neutrality without it.

This orientation must become the backbone of the European Union's action in all its policies that have an impact on, or need to rely on, agriculture.

These numerous policies, which depend on the work of various European Commission departments and the decisions of various Council of Ministers formations and European Parliament committees, need to be brought together under the same banner.

Common Agricultural Policy, Energy Policy (renewable energies, transport), Border Policy (fight against deforestation, implementation of the CBAM, health requirements to be met by imports, enlargement of the EU to 30, neighborhood policy and policy in favor of developing countries), Trade Policy (tariff and non-tariff agreements and concessions, impact on European agricultural trade of geopolitical crises exogenous to agriculture, sanctions and exceptional tariffs, reduction of our dependencies, principle of reciprocity), Environmental policy (ecosystems), Climate policy (reduction of emissions and carbon sequestration, decarbonization of value chains), health policy (use of inputs -phytosanitary, fertilizers, veterinary- in agriculture and livestock farming, animal welfare, NGTs genetics), health policy (nutrition policy, fight against NCDs and cancer), financial policy (agricultural part of the taxonomy remains), cohesion policy (development of the economy and infrastructure in rural areas), all these policies need to be aligned and coherent to turn the goal of strong, sustainable growth in European agricultural production into a tangible reality to the benefit of the European Union, its farmers, consumers and citizens.

In this context, a number of issues are strategic in transforming such a vision into reality:

1) An incentive-based Common Agricultural Policy, the linchpin of European agriculture's transition to a dual-performance agriculture, anticipating tomorrow's European Union, i.e. a carbon-neutral Union and a Union of 30 member states.

To meet the challenge of both growing production and increasing the sustainability of its agriculture, the European Union is facing a wall of double-competitiveness investments designed to generate a rebound in productivity/hectare and real sobriety in the use of production factors (optimum).

To achieve this, a more efficient and clearer CAP must evolve around the following principles:

- Putting farmers at the heart of the CAP. CAP measures must be aimed at those who actually produce agricultural goods and externalities linked to their activity as producers, rather than constituting rents or incentives for idle decline. The approach of promoting environmental managers inspired by the vision of non-productive environmental payments must be rejected in favor of focusing tools primarily on production issues integrating environmental imperatives, one and the other, but not one without the other. Objectives and requirements of the policy should be clearer. Its rational and its requirements should be easier to understand to those who should implement them.

- Putting the entrepreneur at the heart of our actions. If politics is to set objectives and a framework for action, farmers must be recognized as entrepreneurs who decide on the best ways and means to achieve them. The development of a policy objectives and means, and the implementation of objective and effective benchmarking, will be key and much cheaper option in this respect. Rather than conceding systematically greater flexibilities to Member States with no guarantee of results, the European Union should promote an innovative approach offering flexibilities to farmers themselves, giving them the choice between different forms of support depending on their operating challenge and achieved result. Income support remains relevant, indeed indispensable, for a large proportion of EU farms. Having notably in mind the challenge of generational renewal, it could be appropriate as well to design more incentive schemes 1st pillar, such as to offer the possibility to opt for investment envelopes, including allowing front-loading of part of their payment entitlements, which could be enhanced by 2nd pillar type cofinancing incentives. This could provide powerful support for setting-up, generational renewal and competitiveness.

- Incentivize change and reap the economic and environmental benefits, not atrophy them with costs and partial compensation. The incentive to invest in dual-performance agriculture must be THE concern of tomorrow's CAP. Current CAP measures must be resolutely geared towards this priority:

o By making support for double-performance investments in farms and businesses an intangible priority, by increasing dedicated resources and accompanying these measures with stronger support for training. In this context, a European agricultural data plan is a basic step, aimed at covering

the European UAA with data sensors and building up interconnectable databases, an essential step in the large-scale development of precision agriculture for all farms, whatever their size or production method.

o By rethinking eco-schemes as genuine incentives to counterbalance the disincentives or fear to switching to dual-performance agriculture, and not as measures to compensate for new normative costs (avoiding any confusion with the very purpose of agri-environmental measures under the 2nd pillar of the CAP), and by focusing them resolutely on sustainable production tools, defining as a basic principle that these schemes should not induce yield losses.

o By guaranteeing a stable, shared political environment, and a more controlled economic environment in a context of more frequent and widerranging risks and crises: with risk management tools (insurance, IST, health funds) that must be made more attractive, through greater education and European support when risks degenerate into serious crises, with encouraging farmers to adopt hedging instruments, with the rethinking of the current crisis reserve into a European crisis management fund for agriculture, complementing the risk management tools offered by the CAP and taking over in case of major crises.

o By enhancing farm incomes; while the fruits of double performance investments will take a few years to be harvested, the importance of CAP direct aid, which accounts for an average of 53% of farm income, cannot be ignored and their current impact to be ability to invest. Some specific sectorial and territorial dedicated income supports will be needed too if the aim is to keep farmers and agricultural production in all regions across the EU.

o By ensuring that farmers receive a fair return for their work and the expected gains from their investments, at a time when the balance within the food chain has been lost for several years, with a shrinking share of added value going back to farmers. Farmers' ability to organize themselves, transparency and balanced commercial practices are key to this and to the selling of their production at fair price.

o By ensuring that farmers get fair revenues from the public goods they provide (for instance dynamism of rural areas, management of the environment, fight against climate change and challenge of carbon in Europe…)

o By investing in infrastructure - notably to overcome the pressing challenge of water availability and use in agriculture - to be in a position to respond sustainably to the challenge of European food and bio-economy sovereignty; answers have to be provided with no delay, considering the scale of problems affecting notably the mediterranean regions, also mobilizing support for agricultural entrepreneurship in other EU policies (i.e. the cohesion policy).

o All in all, by paving the way for a renewed attractiveness of the farming profession, farmers being entrepreneurs ensuring us healthy, high-quality food, and the linchpin of a more sustainable, more prosperous, stronger Europe

2) A science-based genetic innovation policy that gives farmers the ability to mobilize the full potential of new genomic techniques without constraint or contradiction. For both animal and plant production, genetic research is the other key innovation, along with precision agriculture, to fully combine improved European productivity, adaptation to climate change, reduced inputs and the fight against climate change, and a refined response to nutritional needs. Between now and 2026, the European Union needs to adopt ad hoc legislation.

3) A progressive climate policy aimed at developing a powerful and sovereign European bioeconomy.

a. The transition of entire sections of the European economy depends on our capacity to develop the bioeconomy and mobilize biomass resources. Unless we want to swap our dependence on fossil fuels for another dependence on imports, the European Union must ensure genuine sovereignty for its bioeconomy. This will involve optimizing existing resources (forests, agriculture, waste). But optimization alone will not suffice. We need to increase European agricultural production by more than 25% by 2050. This challenge can be met if the European Union resumes productivity gains of around 1.14% per year.

b. The European Union must stop opening up its bioeconomy outlets to imports to the detriment of its own production. Certification rules and checks on the validity of certifications submitted for imports must be tightened to prevent fraudulent imports (such as palm oils imported from China under used oil nomenclatures) or deforestation imports.

c. All RED Annex IX raw materials must be scrupulously controlled, while fraudulent imports, highlighted by the Court of Auditors, certain Member States and NGOs alike, are undermining the economic capacity of European industries to develop.

d. As bio-economy sectors become increasingly interdependent, the European Union must adopt a stable policy favorable to the development of liquid and gaseous biofuels in the European Union, produced from European raw materials, rejecting simplistic hierarchies of use that undermine emerging economic models.

e. The complementary nature of vegetable protein production and the production of 1st generation biofuels from European agricultural feedstocks is a fact. The distinction between biofuels produced from palm or soybean oil and biofuels produced in Europe from European agricultural raw materials must be clear, and the basis for revised European regulatory provisions that take into account the

dual benefits of the latter: massive reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and co-production of proteins, of which the European Union is woefully short.

f. Enhancing the ability of the EU farming sector to mitigate climate change has to go hand to hand with a focus on adaptation to climate change, both in terms of the investment required and farmers' ability to make the necessary changes.

4) Carbon and biodiversity policies to create value for European agriculture

Agriculture is the only major sector on which the European Union can rely to provide an answer to those economic sectors that will not be able to fully decarbonize. To achieve this, European agriculture must step up its efforts to reduce emissions and increase soil carbon sequestration as much as possible, while increasing production.

The inherent profitability of the sale of agricultural goods will not be enough to achieve such a transition for the benefit of the whole of the European Union.

European farmers must be able to count on the benefits of a clean agricultural carbon market, decoupled from the marketing of agricultural goods.

Imagining agricultural ETS would be counterproductive and would run counter to such a movement and to the detriment of European consumers. On the other hand, European farmers must be encouraged to generate carbon credits by adopting ad hoc practices, the benefits of which are certified. CAP subsidies - both investment aid and eco-schemes or agri-environmental measures - must be mobilized and simplified. Consistent regional baselines need to be defined, so as to reward farmers who are already committed to such approaches (and in no way penalize those who would be above the baseline, who, on the contrary, need to be encouraged and supported). Industrial players in the food chain will have to bear their own commitments to reduce emissions, as will industrial players outside the food chain and not on expense of farmers. Farmers should be able to sell the carbon credits they generate on a private market, and at the same time be able to make environmental claims relating to the farming practices they have implemented for the agricultural products they market.

For future biodiversity credits, the same principles should apply: incentives, accounting, certification, commercial valuation decoupled from the commercial value of the agricultural goods produced by the farm, and the ability to make an environmental claim for the virtuous agricultural practices implemented.

In both cases, the decoupling of the carbon and biodiversity markets from the agricultural products market is a red line, otherwise the value of these credits, integrated by the downstream sector into the price of the agricultural product, would quickly disappears for the farmer, to the benefit of the downstream and upstream players in the agri-food chain.

5) A European Union open to the world, without being native.

Being open to the world has been a clear driver of prosperity for the EU. However, the idea of a Continent focusing exclusively on services, abandoning its agriculture and industrial economic fabric has also proven risky, and calls for serious adjustment, the first one being to re-build competitiveness and efficiency in order to be able to strive. Only then the EU will become again a respected player on the world stage, and not only an attractive market for consumers enjoying low cost products, at the price of high debt. Unless it is to accelerate the economic stall that has already begun, the European Union must rethink its approach to trade negotiations and replace the idea of the overall benefit of an agreement - which accepts the sacrifice of certain sectors for the sake of a positive final economic or political benefit - with the notion of the benefit of each of the European Union's economic sectors. Reciprocity must no longer be just a political stance but a fundamental principle in all trade negotiations and agreements. Trade agreements take time to negotiate and the baseline expectations at the beginning are often no longer valid at the end. Economic sectors at risk are identified at an early stage. The absence of a strategy for both protecting and boosting these sectors before any agreement is signed is unacceptable. This is true of trade agreements, and it is eminently true of the accession process that the European Union has embarked upon, to the benefit of Ukraine in particular. All negotiations must be subject to serious sector-by-sector impact studies from the outset, and a clear strategy must be proposed and financed for at-risk sectors at the same time as discussions are launched (and not in extremis and too late when they are signed), failing which the European Union must adopt the policy of excluding them from the scope of said negotiations.

6) Health policies rooted in the reality of European citizens and industries

Whether they concern plant health or animal health and welfare, science-based policies are essential.

The European Union must systematically examine the costs and benefits of any proposals made by the European Commission, ruling out the gutless path of degrowth and passing on the problems to be dealt with to the countries that would take over from us - usually for the worse - in our agricultural regression.

While there is a consensus on the need to reduce the use of inputs and their impact, the mobilization of treatment products must be effective, when necessary, at a time when climate change and the opening up of borders are increasing health risks.

The search for zero residues must replace the search for announcement effects of flat-rate reductions that ignore the agronomic needs of agriculture. The data era - in which European agriculture must be helped to fully seize the opportunity - authorizes such pragmatic political orientations and calls for us to turn away from shortcuts with uncertain scientific foundations. They need to be worked out from the outset with the scientific community and the industry, in a spirit of both ambition and technical and economic realism.

The same applies to changes in animal welfare rules.

Lastly, there must be established real equality of treatment between European production and agricultural imports. On points with clear links to human health (hormones, growth promoters, residue levels not authorized for health reasons) or to health risks for the European Union, strict application of European standards must be the rule, without delay or exemptions.

When it comes to production standards adopted by the European Union for its agriculture, the EU's ability to impose them on imports is questioned and clear answers must be provided. In cases where this cannot be envisaged, an analysis of possible market distortion must be carried out, and answers provided. To achieve this effectively, policy option that would reverse the burden of proof from authorities to the operator shall be explored.

Last but not least considering diseases affecting European agriculture, cooperation and coordinated answers have to be enhanced in the EU.

Human health / nutrition

The European Union must maintain its high standards in terms of human health, and the high quality of its food chain, whose high sanitary standards start at the farm gate. The same must apply to imported products.

Even if health is not a fully European Policy, the E.U. has the objective of ensuring a high level of human health protection in the definition and implementation of all Union Policies and Activities and proper functioning of internal market for all. Internal Market and Consumer Protection are the basis for regulations in different areas such as food safety, labeling and food information to consumer, nutrition and health claims, advertising ...

As underlined by EFSA, "because diets are composed of multiple foods, overall dietary balance may be achieved through complementation of foods with different nutrient profiles so that it is not necessary for individual foods to match the nutrient profile of a nutritionally adequate diet. Nevertheless, individual foods might influence the nutrient profile of the overall diet, depending on the nutrient profile of the particular food and its intake, in terms of frequency and amount".

In that context, EU initiative is needed and has to be truly European: the design should be common, but the evaluation system be flexible enough to consider national sensibilities. National Dietary Guidelines can be used as baseline. It should impartially inform consumer about the facts, not judge or – even worse – manipulate them: FOP has to inform consumers about healthier choices, not make it for them. It has to use extensive approaches and avoid simplistic ones: not limit the evaluation only to some components

of food, and to use plausible portions, close to reality and finally to consider the level of processing as the link between ultraprocessed food and NCDs is very well documented.

The EU has to promote the value of its food cultures within the UE and outside. It has to be proud of the origins of its food and promote them through a clear labeling. A specific focus has to be developed on local food systems promoting bottom-up approach for the promotion of local networks of production and consumption:

• Improving the ecological footprint of the agri-food supply chains

• Distribute added value more fairly added value

• Improving flows and exchanges between rural and urban areas

• Promote habits healthy and more responsible from an environmentally and socially responsible.

Another crucial issue to address is denominations of food in order to provide true and reliable transparency to consumers and protect food products originated from agriculture and refuse any misuse by some synthetic food which poses societal, health, GMOs and environmental questions. Assessment of synthetic food can’t rely on EU Novel food regulation and the European Commission must initiate a broad debate and propose a new set of regulations adapted to such products.

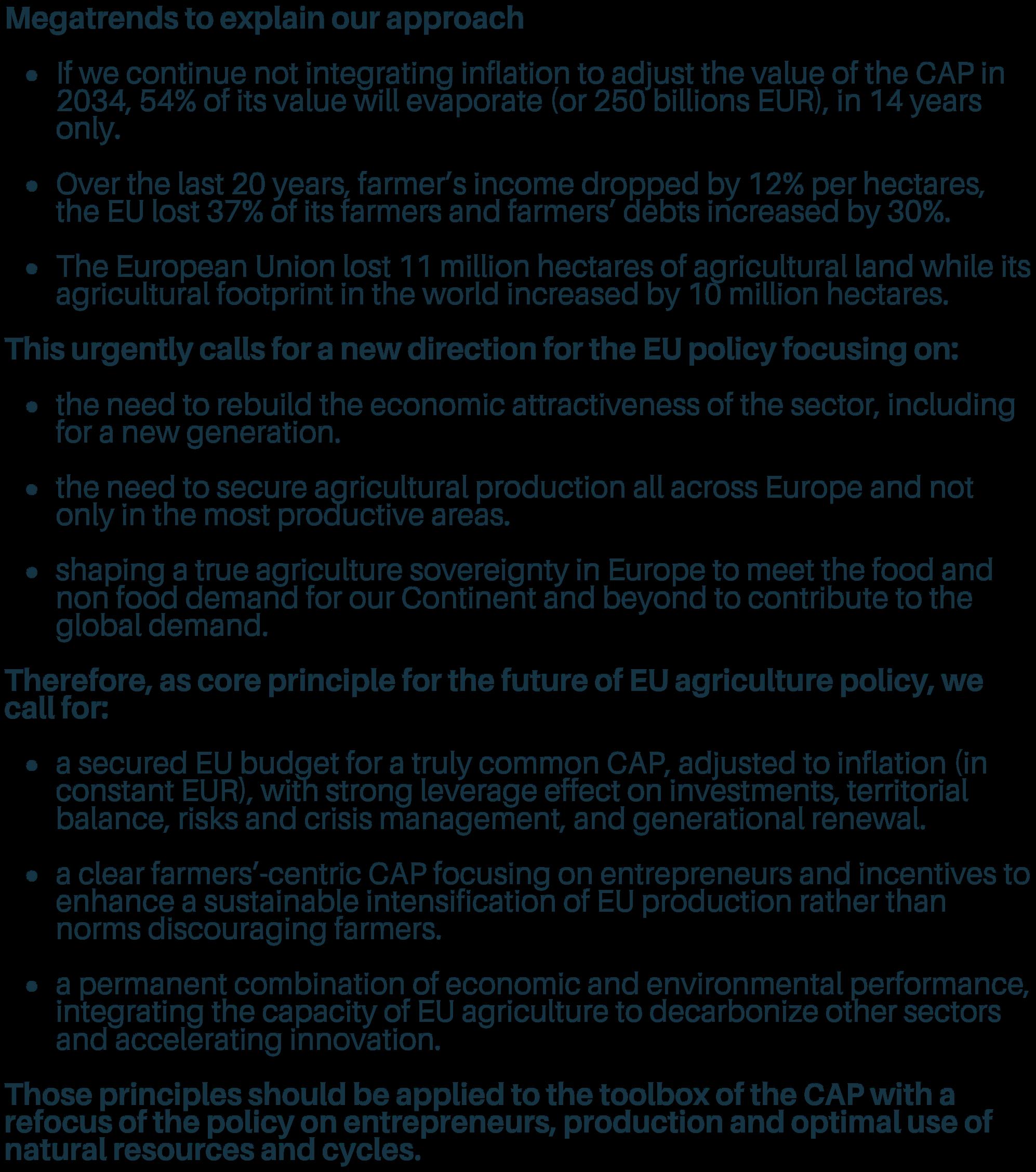

7) European funding to meet the challenges

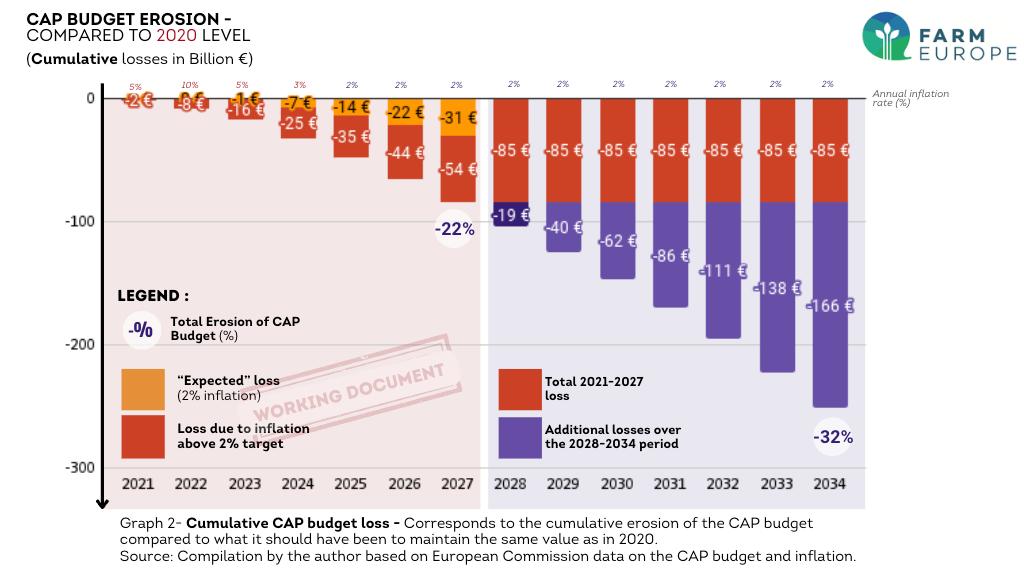

In 2019, the Heads of State and Government decided not to index the CAP budget to inflation for the period 2021-2027, assuming an average annual inflation rate of 2%. In fact, this decision confirmed the principle of a cut of 31 billion euros over the period, compared with a budget maintained in constant euros on the basis of 2020.

The return of high inflation in the EU as a result of the Covid crisis and the war in Ukraine has accelerated the erosion of the economic value of the CAP budget, which will fall by at least 85 billion euros (equivalent to 2 years of direct CAP aid) over the period 2021-27 (-22%).

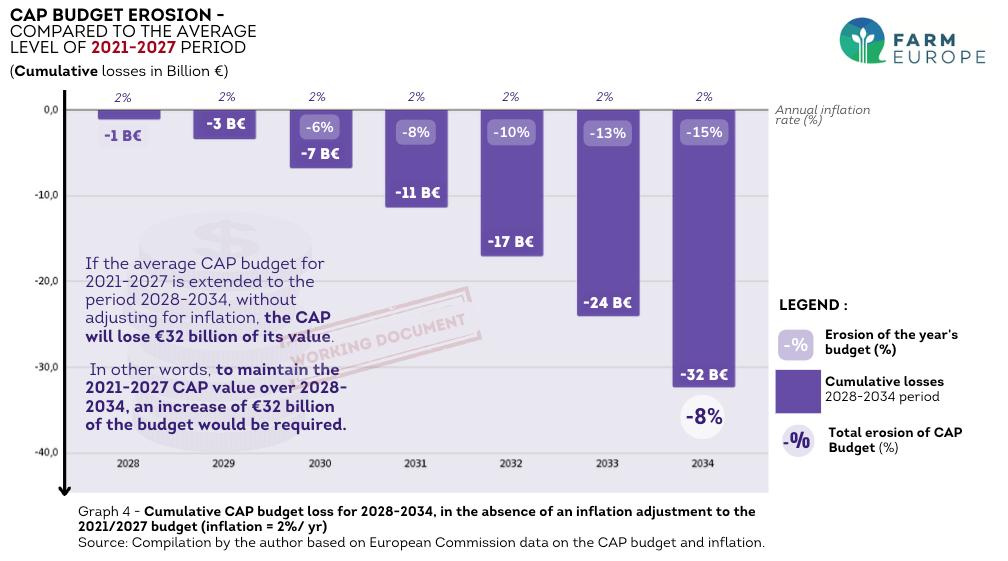

Simply maintaining an economic value for the CAP budget equal to that of the 20212027 period (constant euros) calls for a decision to increase the CAP budget by 32 billion current euros over the 2028-2034 period, subject to inflation returning to moderate levels (2%/year on average).

The economic value of the CAP has plummeted. This must be stopped as a matter of urgency. The CAP's ability to provide real guidance will depend on the political choice that is made, and whether or not there is a corresponding financial incentive. Any financial incentive will have to be earmarked to meet the most pressing challenges, so that European agriculture can return to an upward spiral of profitability, investment cycle, increased production and concomitant greater sustainability.

In the recent years, the share of CAP expenditure in total agricultural income has fallen. If this trend continues, there is a substantial risk that the CAP will no longer have any political incentive and will logically lead European farmers to further concentrate agricultural production (continuous decline in the number of farms) and reorientate towards pure market signals, i.e. to retreat from addressing all the positive externalities that are needed in the context of the transition towards more sustainable production.

However, without waiting for the next financial perspective period, European agriculture is facing an investment wall estimated by the European Commission and the EIB at 62 billion euros. To overcome this wall, a fund for the dual competitiveness of European agriculture must be mobilized, in addition to the CAP budget. To be effective, this fund must represent at least a third of the investments to be made over the next few years.

(Let's not forget the negotiations on the agricultural share of the EU Recovery fund. Initially proposed by the Commission at 15 billion euros, the final decision only conceded 8 billion euros to a sector recognized as strategic for European sovereignty).

The findings: productivity struggling, environmental performance improving, economic profitability collapsing.

"President Von der Leyen describes sustainable prosperity and competitiveness as one of the key priorities for the EU in her political guidelines for 2024-2029. The close link between productivity and competitiveness is also emphasized in the 2024 Report on the Future of European Competitiveness, which clearly states that "the core of a competitiveness strategy must be to increase productivity growth, the main driver of long-term growth, leading to higher living standards over time". These considerations also apply to European agriculture, and highlight the role of productivity in improving its long-term economic viability." . 1

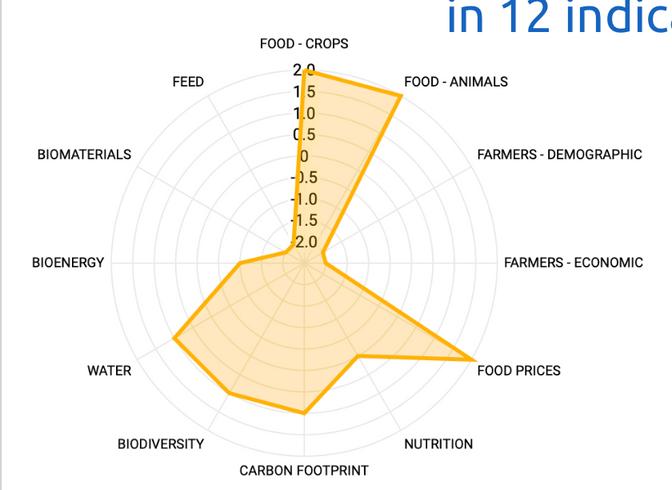

Radar Farm Europe:

- an overview of the key parameters of social, economic and environmental sustainability.

- 12 situation and trend indicators

- A coherent picture of the current situation, both at EU level and for each member state.

- Based on structural and economic data from international and European institutions (Eurostat, FADN, FAO, etc.).

SUSTAINABILITY OF EUROPEAN FOOD SYSTEMS

1) The competitiveness of European agriculture has been struggling for the past two decades, with profitability eroded and production stagnating, except in certain eastern EU countries which have been able to take advantage of the increased public support they have received to invest in their agriculture, and which have also experienced a sustained pace of agricultural restructuring.

1 Measuring agricultural productivity, October 2024 EC. DGAGRI.

2) Efforts to improve the environment and respond to societal demands have been genuine. From 1990 to the present day, European agriculture has been the "star performer" among European economic sectors, even if some member states have followed a different trajectory. ( https://www.farm-europe.eu/uncategorized/sustainabilityradar/ )

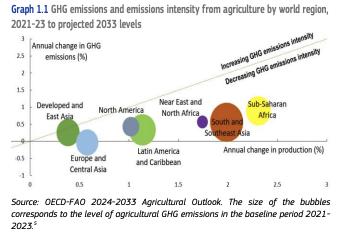

Europe is the area of the world that has most successfully decoupled the growth of its agricultural production from greenhouse gas emissions, albeit at the cost of slower growth than its major global competitors and a normative cost that weighs on its economic capacity to prepare for the future in the absence of an incentive policy combining economic and environmental gains.

The positive developments achieved in terms of carbon intensity, soil, air and water quality must be pursued. The ecological transition of European agriculture is a non-negotiable objective. However, the way in which this transition is to be carried out must be debated, without dogma or taboos. The orientation of Farm to Fork as proposed by the previous Commission led to a drop in European agricultural production of some 15%, higher prices for consumers and increased imports, in a way that was inconsistent with the needs of a European Union that would like to achieve a Green deal for its entire economy, while strengthening its sovereignty and competitive position in the world. In environmental terms, this proposal was at best neutral for the planet, and potentially negative notably due to impacts of imports.

The European Union's actions must be consistent with its objectives: in terms of pollution, the aim is to achieve minimal residues in soil, air, water and food. The modalities must therefore follow on from this.

With regard to carbon policy, it is the reduction of emissions from the sector and increased storage by agriculture that should be encouraged, as agriculture produces externalities in parallel with agricultural production, without any link to the remuneration of such externalities in the commercial value of the agricultural products.

3) On EU markets, the move upmarket has remained a promise that has not materialized. Prices remain consumers' and traders’ predominant purchasing criterion. Farmers' position in the distribution of added value in the food chain has deteriorated.

4) The limited productivity gains of recent years have been absorbed by rising normative and production costs and reduction in relative public subsidies, leaving European agriculture more cash-strapped than ever to face up to the challenges of European sovereignty, of the European Union's place as a credible global political and economic power, of the ecological transition whose path must nonetheless be pursued, and of combating the effects of climate change on our European economies.

The 9.1% average European increase in the productivity of agricultural production factorsessentially generated, moreover, by the fall in the number of agricultural workers and not by an increase in efficiency per hectare or ton produced - has been absorbed by the fall in the economic value of CAP subsidies. The economic value of CAP subsidies has fallen by over 30% in 20 years (in constant euros). Over the period 2021-2027, the decline is 22%, or 85 billion euros, or two years' worth of direct CAP aid over 7 years, under the effect of uncompensated inflation. These aids nevertheless represent an indispensable component of European farmers' current income: on average, 53%.

This average trend in European productivity masks contrasting trends: a net fall in productivity in the major agricultural countries of the western European Union, counterbalanced by an increase or status quo in the main producer countries of the eastern European Union.

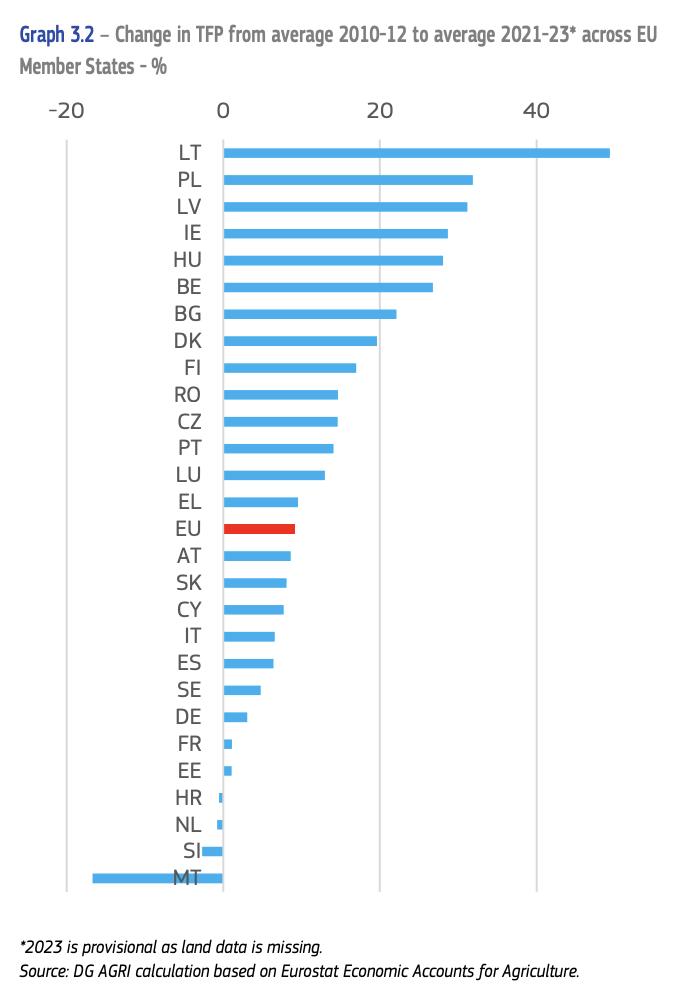

Change in Total Factors Productivity by Member State

An analysis by country reveals divergent trends:

I. A number of countries have seen their agriculture become more profitable and more able to invest in the future: Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Bulgaria, Ireland, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Portugal and Luxembourg.

II. A group of countries, such as Romania, the Czech Republic, Greece, Italy and Cyprus, experienced a situation between flat and slow growth.

III. Finally, some countries have lost the economic efficiency of their agriculture:

● Moderately: Austria, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden;

● of note: Germany;

● with severe loss: France, Estonia, Netherlands, Croatia, Slovenia, Malta.

This development seems to correlate with the patterns of agricultural restructuring and productive investment dynamics that the various countries experienced during this period.

5) It should be noted that the state aid policies implemented between 2021 and 2024 have profoundly changed the situation in certain countries that were particularly "generous" towards their agriculture. This was the case in Poland, which boosted the dynamism of its agricultural sectors even further when state aid was authorized for the "Covid" and "Ukraine" crises, and in Spain, which helped put Spanish agricultural sectors back in a position to invest and develop. The case of the Netherlands is particularly

noteworthy in view of the financial windfall provided by state aids -exceeding the sum of CAP direct aids over the period-, which more than compensated for the loss of economic efficiency inherent in its agricultural activities.

Beyond these particular cases, the lack of sufficient European capacity to really deal with agricultural crises in recent years has meant that member states willing and financially able to do so have been left to support their agricultural sectors with state aid. This was notorious during the dairy crisis of 2015, and has been a constant since, despite the activation of the European agricultural crisis reserve since the Covid crisis. It is also the observation of the limited economic impact of the current European crisis reserve. This position has led to marked differences in treatment between European farmers and between sectors.

6) On top of the economic fragility of its agricultural sectors, the EU faces two other major shortcomings: its dependence on animal feed stock and fertilizers and its virtual absence of participation in the global boom in the bio-economy. The EU is loosing opportunities to imports, which continue to increase. The surge in imports of so-called cooking oil from China illustrates this.

Protein production in the European Union has grown over the past three decades, mainlyif not almost exclusively - as a co-benefit of the growth in European biofuel production from European agricultural feedstocks. In this way, 13 million tons of high-protein products have been co-produced, avoiding this amount of imports, notably of soybean meal. The specific case of the European Union, where increasing its energy sovereignty through the production of biofuels from European agricultural raw materials (including 1ère generation) goes hand in hand with increasing its feed and food sovereignty, has been ignored, if not deliberately distorted, for a decade and a half by pressure groups and the attentive ear that certain departments of the European institutions seem to have paid to them.

A versatile European policy on the development of biofuels since 2010, the tacit acceptance of fraudulent imports in the absence of a serious European certification policy, and tariff concessions granted or announced in favor of imports from across the Atlantic in particular, have frozen European investment in processing capacity of European agricultural raw materials and broken the momentum of the European response to our needs for greater protein sovereignty and responsible supply of our bio-economy sectors, on whose development the success of a European Green Deal is nonetheless based. In total, while the European Union reduced its agricultural area by 10 million hectares over the period, it increased its imported deforestation by almost 11 million hectares. This is an illustrative example of carbon leakage and contrary to the proclaimed basic principles of the Green deal.

7) Faced with a growing global need for proteins and the imperative to reduce emissions, certain capital-intensive players accompanied by pressure groups have in recent years

been trying to impose the production of alternative synthetic proteins to replace animal proteins (dairy proteins, meat) as unquestionable sustainability benefit

Such approach deliberately left unanswered and not debated questions that EU consumers are asking. While communication campaigns are hugely financed to pave the way for the consumption of alternative proteins in Europe, the right of consumers to make informed choices between vegetal and animal protein sources and their origin and production method, their right to understand what the Alternative protein agenda means when it comes to the energy use of such production, to the way it is produced usingdepending on the products- either GMOs, hormones or growth factors, are being overlooked.

A comprehensive debate is needed, incorporating ethical and environmental aspects, avoiding simplistic and unverified claims. Bioreactors would need to use a lot of energy that is assumed to come from renewable sources, whereas we know that even renewable energy is limited. Let's remind that photosynthesis is the only free energy and it is the very base of agricultural production. On the legislative framework, backing the calls from 16 member states at the EU Agricultural Council and the European Parliament, there is a need to assess if the "novel food" Regulation as it stands is fit for purpose, asking to consider future modifications that take into consideration the need to align some aspects of the evaluation of food produced in laboratories with the evaluation procedures of medicines, in particular the request to include pre-clinical and clinical studies to be used as criteria for assessing the safety and nutrition value of artificially produced food and feed substitutes, to take duly into consideration the regulations on GMOs and to address ethical issues. The same considerations imply to the rules that should be defined when it comes to denominations of food substitutes.

8) When it comes to the role and the impact of the livestock sector on environment as well as on our health, the debate should be based as well on science and real figures. On environment, it must take into consideration not only the emissions of the livestock sector, that no one denies are sizeable - even though with a decreasing trend in the last decades, the types of emissions, but also the positive externalities of the livestock production circle as well as the differences between emissions and their effects on the environment. The 80% of water "consumed" in the production cycle of a cow go back to the field with a better quality in terms of organic matter, contributing to make our soils healthier. Manure and by products produced by a cow are the base of a positive and virtuous bioeconomy model of production of energy (biogas, biomethane) that the EU needs, as of organic fertilizer (digestate, Renure), just to give examples.

9) Concerning the interlinked topic of agriculture, food and nutrition, prevention is more effective than any cure. Education is the key element in every long-term vision.

Food is above all source of life. In the last decades science has put the light on what we eat, and has shown that food is a critical factor in human health. Particular importance has been given to its relationship with Non Communicable Diseases (NCD) like obesity, cholesterol, diabetes, cancer, coronary diseases and others related, making from it a priority for public health, having in mind that science underlines that some NCDs are increasingly linked to an over-consumption of foods with chemical and artificial ingredients and a shortage of consumption of natural products Food and beverages are as well much more than simply providing humans the fuel for survive; it is culture, tradition, one of the most important sources of economic activity, employment and innovation in Europe, it is choice, taste, variety etc.... The systems that have been developed for food safety have proven not to be fit for the “health” dimension of food, and for nutrition science which is a much more complex and multifactorial issue.

Today, confusion and divergence of opinions are common, as well as the lack of trust and cooperation amongst all the stakeholders – while they should all have a common goal: improve the quality of life, lifestyles and health of the European consumer.

10) Finally, on the eve of a major enlargement for the European Union and the stability of the European continent, our industries are suffering from competitiveness differentials of 18% to 40% with their future Ukrainian partner.

In terms of its agricultural and agri-food foreign trade, the European Union is the world's second-largest importer of agricultural and food products (first for the least developed countries), and the world's leading exporter by value. Its ability to trade, to create wealth but also stability on world markets and with partner countries that are structurally importers, is key for the European Union’s strategic objectives and for the global security.

While the value of European exports is tending to grow, market shares are, depending on the product, more sluggish or even declining, reflecting the challenge of competitiveness that the European Union is struggling to meet, as well as a standards differential that is not fully evaluated, or even exploited, on third-party markets, and the application of European rules that can give imports into the European Union distorting competitive advantages. However, it is up to the European Union to rediscover the path of internal and external dynamism for its agriculture. Expectations from European agriculture are high, and the opportunities immense, if European policy choices converge to act as catalysts for a growing dual-performance agriculture.

To achieve this, we need to develop a coherent European vision and orderly strategies, with a clear common thread ensuring a hierarchy of actions generating the expected economic, societal and environmental benefits, in cascade.