4 minute read

The figure of the alchemist in medieval and renaissance Europe

OLIVER ZOCCO, 5H

During the Middle Ages, specifically since 11 February 1144, with Robert of Chester’s translation of the Arabic Book of the Composition of Alchemy, alchemy took hold in Latin-speaking Europe: it would sow the seeds of what is known today as Chemistry. But what is alchemy? A layperson might immediately think of their pursuit for a way to turn common, or imperfect – according to alchemists – metals into gold, or their attempts at creating the Philosopher’s Stone, which could accomplish the aforementioned goal. But those are but a few objectives of medieval European alchemy: their actual objective was not simply the transmutation of lead to gold, but instead substantial transmutation: the ability to, through varying processes, transmute one substance into another, of which the process of turning base metals into gold, or chrysopoeia, is but the most famous. Oth-

Advertisement

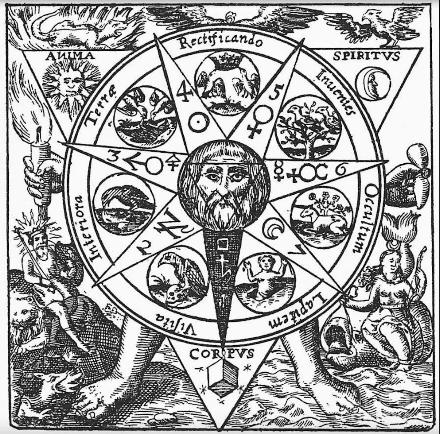

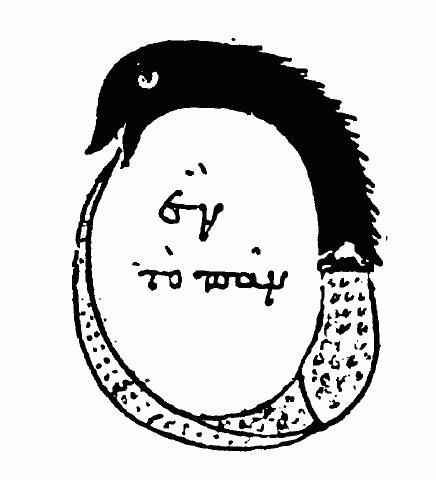

er objectives were the creation of the Philosopher’s Stone, the search for the Alcahest, a substance that could dissolve any other substance, the search for the Elixir of Life, that could confer quasi-immortality upon any person or animal that would just simply ingest it. With regards to their more philosophical and immaterial goals, their primary one was to integrate natural philosophy with metaphysics; such a conception was rendered possible by the recent rise of the Scholastic school of thought, that attempted to reconcile rational empiricism and faith, priming Europe for the influx of alchemical thought. For most of the following two centuries little to no contemporary contributions and advancements were made, with most of the efforts remaining focused on translations, and later summaries and explanations in Aristotelian terms of alchemical knowledge done by encyclopaedists, who succeeded the translators. During this time, the vast majority of alchemists were clergymen or scholars. This changed with Pseudo-Geber’s Summa Perfectionis, a staple summary of alchemy released shortly before 1310, that described practical operations and processes together with theory, and argued that artifice could replicate or even better nature, by perfecting matter, all while remaining clear and largely unobfuscated, unlike many other contemporary texts on the matter. Concurrently, alchemy had gained a fairly ordered system of beliefs, with

most of the adepts practicing their art systematically, but purposely cloaking their texts. The concepts of materia prima, the primitive substance that posed the base for all subsequent matter, anima mundi, or soul of the earth, the macrocosmos-microcosmos theories of Hermes, according to which the same processes that affect substances can affect the human body, and the purification and perfectioning of the human soul via the Magnum Opus, or

Great Work were particularly integral to alchemy. In the 14th century another shift in the figure of the alchemist occurred: with alchemy exiting the limited social spheres of Latin-speaking clergy and scholars, the pseudo-alchemical charlatan emerged. Because of this, the discourse around them shifted to social commentary on the alchemists themselves: Chaucer and Dante, to name a few, portrayed them as thieves, scammers and liars; Henry IV banned the practice of multiplying metals, and Pope John XXII forbade false promises of transmutation. The actual scholarly art of alchemy continued nonetheless, albeit gaining an increasingly Christian tone, with the vast majority of its adepts being clergymen. In the Renaissance, the branches of entrepreneurial, pharmaceutical and medical alchemy were born, thanks to the reintroduction of Platonic and Hermetic foundations to the subject. The latter two branches were pioneered by Paracelsus, who moved away from chrysopoeia, favoring instead the use of chemicals and minerals and medicine. Entrepreneurial alchemy instead arose from the crisis of the medieval economical system, and from a need to obtain a stable and abundant supply of precious metals, given the great fluctuations in their supply in the 15th and 16th century, first because of the shortage caused by the general lull in mining operations following the Black Death, and then in the 16th century because of the glut caused by the abundance of silver from Spain’s colonies in America. These new alchemists, who were expected to sign a contract with theirs sponsor, be it a king, prince, noble or merchant, that regulated very precisely almost everything about their practice, down to the specific transmutations they must do, and the layout of their laboratory. They marked the start of the transition from a mostly esoteric art, focusing on metaphysical and philosophical matters, to a more exoteric art, with their treatises and texts resembling more closely assaying and mining techniques and processes. While these contracts carried penalties in case of failure, fraud, theft, and a whole slew of infractions, usually under the form of death, these remained fairly common, with many using sleight of hand or other such methods to convince investors in their abilities, given that there was no guild

of alchemists that could guarantee their competency, nor had the field been recognized academically at universities. In conclusion, from the arrival of alchemy in Europe until the Renaissance, there were a multitude of types of alchemists, all taking up a somewhat differing roles in society, starting as translators, then philosophical and experimental debaters, charlatans (who were not considered true alchemists, despite their claims), and in the Renaissance pharmacologists, doctors and entrepreneurs. Across all of these, the true Alchemist has always resembled much more closely a proto-researcher, than a wizard, sorcerer or mage.