The Light of

Coincidence The Photograph of Kenneth Josephson

The Light of Coincidence

The Photograph of Kenneth Josephson University of Texas PressGenerous support for this publication was provided by the Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago, Illinois.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are copyright Kenneth Josephson, courtesy Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago, and Gitterman Gallery, New York.

Copyright © 2016 by Kenneth Josephson

Foreword © 2016 by Gerry Badger

Essay © 2016 by Lynne Warren

All rights reserved.

Printed in China

First edition, 2016

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions

University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO 239.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Josephson, Kenneth, photographer. [Photographs. Selections]

The light of coincidence: the photographs of Kenneth Joseph- son/Kenneth Josephson; foreword by Gerry Badger; essay by Lynne Warren. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4773-0938-4 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Photography, Artistic. 2. Street photography. 3. Josephson, Kenneth. I. Badger, Gerry, writer of supplementary textual content. II. Warren, Lynne, writer of supplementary textual content. III. Title. TR 655.J67 2016

770.92 dc23

2015028437

“Chance favors the prepared mind.” — Louis Pasteur

KENNETH JOSEPHSON IS TALL, and in his ninth decade he still stands straight. He has worn his hair long and tied back for years even as it has thinned and turned white. His gaze is steady, and often holds a slant of inquiry, as if he’s thinking deeply while he listens, and even more deeply while he speaks in his soft, deliberate voice with the flat tones of his midwestern heritage. He favors cowboy boots an hats; some of his self-portraits show his behatted shadow.

While I have known Josephson for over forty years, and he is friendly and open, there is an essential mystery about him, as there is about any true artist. I have long known of his Detroit origins and the path to his art form: a childhood interest that caused him to pursue an education as a commercial photographer at the Rochester Institute of Technology, followed by his enrollment in the now-legendary graduate program at Chicago’s Institute of Design (ID).

With Josephson in his eighties, still vital and still making photographs, contemplating his journey to success as a seminal, world-renowned photographer evokes faraway and perhaps mysterious times and places, especially for his younger admirers, bred as they are on digital photography

shaped by the conceptualism that Josephson in large part brought to the medium. For those of us who are longtime admirers, Josephson’s story, given that he emerged in an era of limited choices and significant barriers to establishing a life in the arts, has a bracing, optimistic quality.

What was it to be interested in photography coming up in Detroit in the 1950s? The city, at that time, was a potent symbol of American know-how and industrial might but hardly a cultural powerhouse, although it had produced one of the twentieth century’s most extraordinary artists in Josephson’s mentor, Harry Callahan. As a boy, Josephson had recognized how “wonderful”—to use his own word—it was to shoot and print photographs in his own darkroom. Pursuing his interest in photography, he attended the only photography school he’d then heard about, the Rochester Institute of Technology ( RIT) in upstate New York. At the time of Josephson’s attendance, RIT offered only a two-year program.

Upon graduating with an associate’s degree in applied science, he was drafted into the army and spent much of the obligatory two years working in a darkroom in Germany. It was mere happenstance that, during the period of Josephson’s military service, RIT's offerings in photographic education expanded to include a four-year degree program that featured on its faculty such well-known finearts photographers as Minor White.

This development drew Josephson back to Rochester, and it was from the contacts made in Rochester, the second time around that Josephson heard about ID. Armed with RIT's

newly bestowed bachelor’s degree, he was able to be admitted to the only graduate program in fine arts photography in the United States. He relocated to Chicago, where he thrived under the tutelage of instructors Callahan and Aaron Siskind, and obtained his MS in 1960, becoming part of the famous “Chicago School.” The G.I. Bill—a benefit afforded by his service in the army-had allowed Josephson to pursue an unlikely career for a man of his time: fine-arts photographer.

Not only was he entirely successful in that pursuit, as evidenced by his outstanding international career, he was also a path- finder for another unlikely vocation, that of professor of photography. After founding the photography department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in 1961, he taught there for thirty-seven years.

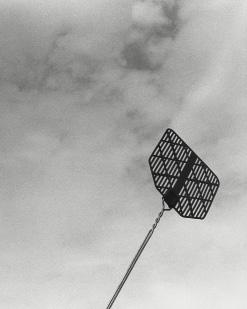

Contemplating this chain of events, it is not surprising to learn that Josephson is drawn to the words of the scientist Louis Pasteur: Chance favors the prepared mind. He cites this concept as a guiding principle for his life and art, and on the matter of how he works, Josephson is absolutely clear: “The idea is most important. . .I ‘make,’ not take, photographs.”

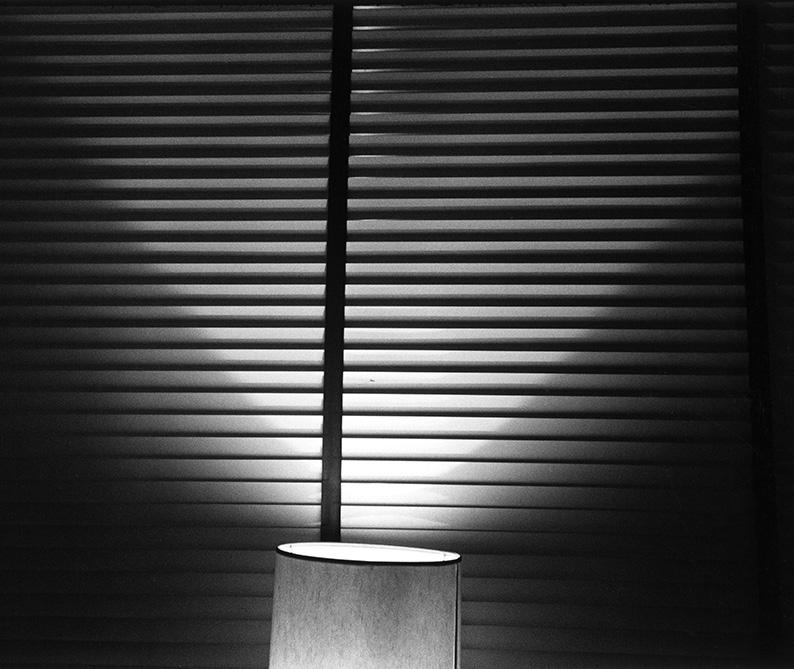

Despite all the change Josephson has seen during his lifetime, in the world and in his field, he still uses film and develops photos in his own darkroom. And even a cursory overview of his formidable oeuvre reveals his dedication to making photographs that accurately describe but at the same time intrigue; photographs that capture the world but cannot be said to document it; images that please the eye while exciting the brain. This cerebral approach of “making, not taking” photographs casts Josephson as one of the first conceptual photographers. He is an artist who creates photographs that are best understood by acknowledging and exploring the ideas presented by the images. Yet, despite being idea-driven, the images are visually interesting and often exquisite in their composition, tonality, and clarity.

Even when Josephson was producing photographs that are today classified as street photography, a genre seen as occupying many who studied at ID in the 1950s, it is clear that the ideas behind the making of the images were predominant. His ID training, like that of his fellow

students—Joseph Sterling, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Joseph Jachna, Ray Metzker, and Charles Swedlund—centered on the exploration of techniques (such as in-camera multiple exposure) and themes (such as city life). At sixty years’ remove, there is an undeniable fond nostalgia for the inky blacks and shrapnel whites of street photography, in which the gloom and grit and bleak anonymity of the midcentury industrial city are preserved, shrouding in shadow people with masklike, expressionless faces or illuminating them with harsh light.

But these photographs speak of more than romance for a bygone era. They also speak of the demographic of Josephson’s generation: postwar, mostly male, and seeking a very different vision than the precision of the f/64 school, as typified by

photographs that capture the world but cannot be said to document it; images that please the eye while exciting the brain.

the early- twentieth-century masters Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. Fame was never a consideration for the photographers making their way in the 1950s, because fine-arts photography was a rarefied field and few made a living at it unless they taught or did commercial studio work on the side. Although Josephson’s work clearly shares formal similarities with that of many of his ID contemporaries, even at this early stage in his development he was not merely documenting his surroundings. His images were not only carefully crafted, but carefully thought out.

At this time in his career Josephson alternated between the example of his teacher, Harry Callahan, who experimented with light and multiple imagery and sensitively photographed the city and its people-including his wife and daughterand the example of Aaron Siskind, who is best known for pulling the urbanscape in for close-ups of peeling paint, walls layered with posters, graffiti, and grime. Like most of his peers, Josephson set out into the city and made pictures of seemingly meager circumstances: people under the El, boys

playing on piles of rubble. But they are also beautiful and sensitive pictures, personal in a way that the great mountain ranges and elegantly posed nudes of his f/64 school predecessors are not.

By the late 1950s, however, as the economic growth of the postwar era offered stability and more options for a rabidly growing, consumerist middle class, opportunities emerged for the artists to both make a living and make a difference in the visual culture. The photo community, though it remained small and tightly knit, was beginning to feel the urgent necessity of change.

But for the moment, the world as pictured by Josephson was still dark, with an elegiac, closed-in quality. One of his early masterpieces is the poetic Chicago, 1961 (p. 145). This photograph shows a Callahan- frieze of bodies under Chicago’s famous El. The poses of the subjects and rhythms of this photograph are so astonishing that it is hard to believe the figures weren’t posed or choreographed, but they were not. The picture, a masterful melding of the photographer’s attuned eye and the chance occurrences that continually occur, demonstrates Josephson’s method.

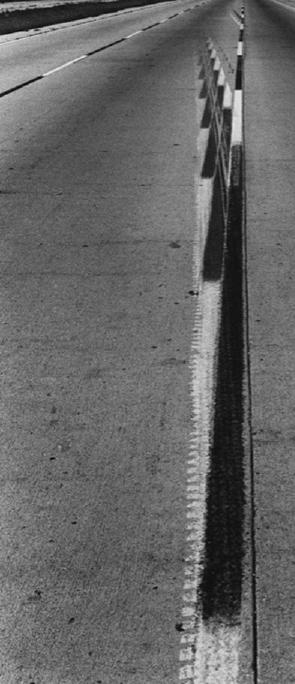

This “eye” is evident in the precise geometry of the lines of the pavement and the streaks of sunlight on it: the central vertical line falls virtually in the center of the image as it joins the black band that runs across the image’s lower edge. The chance occurrences of the world are represented by the “spot- light” that falls on the two men and two women: that is, the strong summer sunlight penetrating the deep shadows of the iron and wood structure of the elevated tracks and platforms and highlighting the perfect, balanced posture of the woman on the left; the graceful arc of the man’s body on the right; and the man in midstride, swinging by the woman in the center

whose stance is a less composed reflection of the poise displayed by her female counterpart. And then there is that astonishing bit of frivolity on the back of the man at the right as the sunlight illuminates a vertical pattern on his shirt fabric. This isn’t the magic of the darkroom, this is eye magic.

Given the immense poetry of an image such as Chicago, 1961, the matter-of-fact way that Josephson has spoken about the making of these works can be startling. In his early years of employment at the School of the Art Institute Josephson was hired shortly after obtaining his degree from ID on the strength of his graduate thesis-he was kept quite busy by his classes. But, dutiful to both his job and his craft, Josephson used his lunch breaks and his moments before heading home to expose film. SAIC is situated just east of that area of downtown Chicago called the Loop, so named because it is encircled by the elevated train.

The structure that provided a visual environment so appealing to Josephson-his beautiful images made under the El belie the hectic pedestrian traffic, the ear-splitting noise of bare metal on

This ‘eye’ is evident in the precise geometry of the lines of the pavement and the streaks of sunlight on it: the central vertical line falls virtually in the center of the image as it joins the black band that runs across the image’s lower edge.

metal, and the often overwhelming pigeon filthwas a convenient five-minute walk from his workplace. It was also a familiar environment in which he was comfortable. The Institute of Design, where he had spent the previous two years, was located near the El tracks on Chicago’s near-south side. Furthermore, the theme of bodies struck by light was an important aspect of “An Exploration of the Multiple Image,” the thesis Josephson had submitted in June 1960 as a requisite for receiving his master’s degree. In the thesis, an in-camera multiple exposure of children jumping titled Chicago, 1960 (p. 134) shows wildly distorted black shadows. These were cast by the nearby El tracks (now known as the “Red Line”), falling across the steep sandy mounds of a vacant lot across the street from ID. Another version of this image is Chicago, 1960 (p. 135), which is not a multiple exposure and which more clearly shows the boys in winter coats gleefully clambering up, and then throwing themselves off, the hillocks.

The boy silhouetted against the horizon line of the mounds eerily recalls Robert Capa’s famous “The Falling Soldier” (Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936). But a photographic reference much closer to home would be Aaron Siskind’s renowned body of work, Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation, the

series of men caught in midair that he undertook between 1953 and the mid-1960s. Josephson’s chronicling of Chicago’s urban environment forms an essential component of his oeuvre and was continued in subsequent decades. He again photographed the glaring light and dark shadows beneath the El tracks in the virtually rococo Chicago, 1964 (p.158), and returned to this seminal subject matter in Chicago, 2012 (p. 207).

By the mid-1960s, however, he had begun to have deeper insight into what he was achieving as a photographer. His subject matter expanded as he realized an essential truth about his undertaking. “The photograph describes very little, actually. Photography can only describe surfaces,” Josephson told an interviewer in 1979, and then added the important caveat, “but it depends how you describe those surfaces.”

As his career unfolded, those surfaces included the urbanscape captured in unexpected juxtapositions, nature as touched by man, as well as his children and his wives and lovers, clothed or nude. With this highly conceptual approach, Josephson was able to realize in his work his maturing ideas about photography and the nature of photographic representation. Seeing the world as surfaces that photography was able to depict changed how he began to describe these surfaces. Josephson began to photograph his own arm extended into the picture plane, holding a postcard, a contour gauge, or a photograph. He began making photographs of photographs by placing his own images back into a setting that had been subsequently documented. Josephson employed not only traditional black and white photography but also the techniques of collage and assemblage. He created a genre-defining artists’ book, The Bread Book (1973), which

documents the slices of a loaf of white bread in a deadpan progression of photos, and experimented with “instant photographs” using the Polaroid SX-70 camera.

Over the years, Josephson has continued to pursue all of these subjects and methods of working. While it is not unusual for photographers to work in series, it is much less common for an artist to work in decades-long, ongoing series punctuated by other, more singular, explorations. In 1961 and 1962, perhaps as a break from the multiple-image landscapes and urbanscapes of his graduate portfolio work, Josephson photographed in-studio still lifes of paper bags. Possibly because this work was so different, it was not widely known until it was published in the catalogue for his 1999 retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago (see pp. 279 to 283). Years later, after making numerous photographs for his seminal Images within Images,

exploring the presentation of a sequential image within a singular picture

History of Photography, and Marks and Evidences series, Josephson photographed lightbulbs, exploring the presentation of a sequential image within a singular picture (Polapans, 1973 [p. 291]), a theme originally handled very differently in the breathrough images-within-images Chicago, 1964. Then, in the late 1980s, he produced elegant studies of books, including Chicago, 1988 (p. 303), that clearly refer to the paper bag images insofar as the pages have been folded into geometric shapes and photographed against a black background.

What is consistent over the span of his sixtyyear career is that almost all of Josephson’s images are made out of doors or inside his home, which he often trans- formed into a “studio” through the use of backdrops and/or props, but that never became, in any sense, a traditional photography studio. The only time Josephson photographed interiors outside his own home was in 1956 for his undergraduate RIT portfolio, “Front Street, Rochester,” which documents dimly lit, run down shops and bars as in Front Street, Rochester, N.Y., 1956-57 (p. 116). And although he is strongly associated with Chicago, many of Josephson’s best-known works were photographed in other places in the United States; in various countries of Europe, including Sweden, England, and France; and in India, where he traveled in 1975 and 1983.

By the 1980s Josephson’s reputation as an important and innovative photographer was secure, but his work had been little seen outside photography venues.15 Also by the 1980s, conceptual art was emerging as a mainstay in contemporary art. The happy combination of my having gotten to know Josephson and his work, as I had been his student in the early 1970s, and my position as a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago prompted a mid-career retrospective there in 1983.

Coming to Josephson’s work from the dual perspectives of the history of photography and recent developments in contemporary art, I considered it imperative that New York State, 1970 (p. 35), the now-iconic image of Josephson holding a postcard of an oceanging ship out over Lake Ontario, be on the catalogue’s cover. This photograph spoke eloquently of Josephson’s vision and illustrated the essence of conceptual art—that the idea structures the artwork and is the starting point for understanding the work. New York State, 1970 was first among equals, so to speak, in demonstrating Josephson as one of the first makers of conceptual photographs.

The MCA , as a museum of contemporary art, was not overly interested in traditional photography, and it is gratifying to look back and recognize that my col- leagues also saw something very different in Josephson’s work; otherwise, the exhibition would never have occurred. This “something different” was exactly what had caused Josephson, in his Rochester years, more than a bit of trepidation. As accepted as it is now, the idea of making a photograph was once revolutionary. Josephson’s own words illustrate this point: “Contriving the image was seemingly a mortal sin; I felt uneasy doing it at first.” It was Siskind and Callahan who encouraged him to look at the photograph for what it was a two-dimensional image that was also capable of curling at the edges to become a three-dimensional object.

At ID, founder László Moholy-Nagy taught that the image captured by a photograph was inherently objective given that it accurately recorded lights and darks. Supported by his own innovations and experimentations with photograms and his famous Light-Space Modulator in the 1920s, Moholy-Nagy looked at photography in the most basic way: “It must be stressed that the essential tool of photographic procedure is not the camera but the light-sensitive layer. This, of course, reminds all who think deeply about the field that the word “photograph” means “light-writing.” But

the popular view of photography was that the content of a photograph in one way or another documented the “real world,” a very different idea than that of Moholy-Nagy’s, and this belief was deeply ingrained. As recently as 1989, Merry Foresta, in a catalogue for an influential traveling exhibition, The Photography of Invention, penned an essay that was basically a long plea for our understanding that photographs can be “made.”

As Josephson began his career in the 1960s, he faced interesting times. As evidenced by numerous exhibitions at such venues as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, fine arts photography was enjoying considerable popularity. Articles on the medium were routinely featured in the New York Times and other big-city newspapers. Perhaps in part because of this new popularity, it remained intimidating for photographers to throw off the traditional beliefs that shaped the medium.

It must be stressed that the essential tool of photographic procedure is not the camera but the light-sensitive layer. This, of course, reminds all who think deeply about the field that the word ‘photograph’ means ‘light-writing’.

At the same time, the newly emerging discipline dubbed “con- temporary art” encouraged radical experimentation and the use of photography to document some of this experimentation. It is difficult to overstate how small, how segmented, and how insular the contemporary art world was as Josephson was beginning his career. Due to timeworn prejudices, photography was cordoned off from the “fine arts” painting and sculpture.” Even when photography, as practiced by those with traditional train- ing, received attention from the more broad-minded within contemporary art circles, it remained in the shadow of the rapidly developing “new media” of video, performance, installation, and earthworks.

During the 1960s, Marcel Duchamp’s anti-retinal stance had fired the intellects of numerous young artists-including Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Robert Smithson, Ed Ruscha, and Dan

Graham-who established themselves, in what was considered a great advance from Modernism, as conceptual artists. They created works in which, to use LeWitt’s famous phrase, “the idea is the machine that makes the art.” Some of these conceptual artworks were in part or solely realized as photographs by individuals with no formal training in photography, including Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) or Graham’s Homes for America (1966-1967), which was first shown as a slide presentation and later as an illustrated essay published in Arts Magazine. Yet for those with traditional photographic backgrounds, even when they engaged with the new visual culture, their efforts remained cloistered within departments of photography, promoted by a relative hand- ful of tastemakers, including curators John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and David Travis at the Art Institute of Chicago.

It is instructive to compare the timeline of Josephson’s development with that of conceptual art. As Josephson was completing his graduate portfolio at ID, the early projects of the 1960s

Fluxus artists — a group that included media innovators Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono, whose performances and happenings were documented by photographs-were in the avant-garde of contemporary art, introducing new ideas into an artworld long dominated by painting.

I love being around women. I’ve always been fascinated by them and curious about them. I have always been interested in the female form. Most of my models are women I am close to. When you live with a person, you observe them around you day-today, and when you see something, it could be that the light’s right at the moment, but most of the time, it was just seeing something interesting and making a picture quickly.

Era Mahoney // Spring 2023

GR_619_01: Type Composition

Academy of Art University

Body copy: Arno Pro 8.5pt / 12.5pt

Pull quote: Baskerville Display PT 13pt / 16.9pt

Column width: 14p4