The New Australian Dream

rethinking our suburbs

If “A Man’s Home is his Castle”1, we live in a nation with the biggest and most sparsely spread castles in the world, and we’re building them at an alarming rate2.

Robin Boyd once wrote about our “vandalistic disregard for the community’s appearance3” in his scathing but seminal book, The Australian Ugliness.

Little did he know how pervasive that disregard would become.

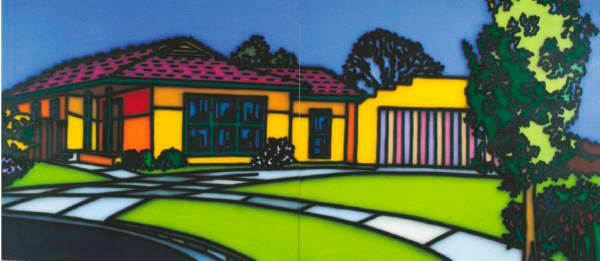

“Featurism” was born out of a quest for an Australian sense of identity and belonging, manifesting itself in well-intentioned but ultimately skin deep surface treatments.

It has only gotten worse as we’ve spread out ever further from established city centres4 and easily accessed amenities and transport, in a phenomenon known as urban sprawl.

We are building bigger homes5, or McMansions, on smaller blocks6 that don’t relate to their environments, but rather aspire to “shout the importance of their owner7”.

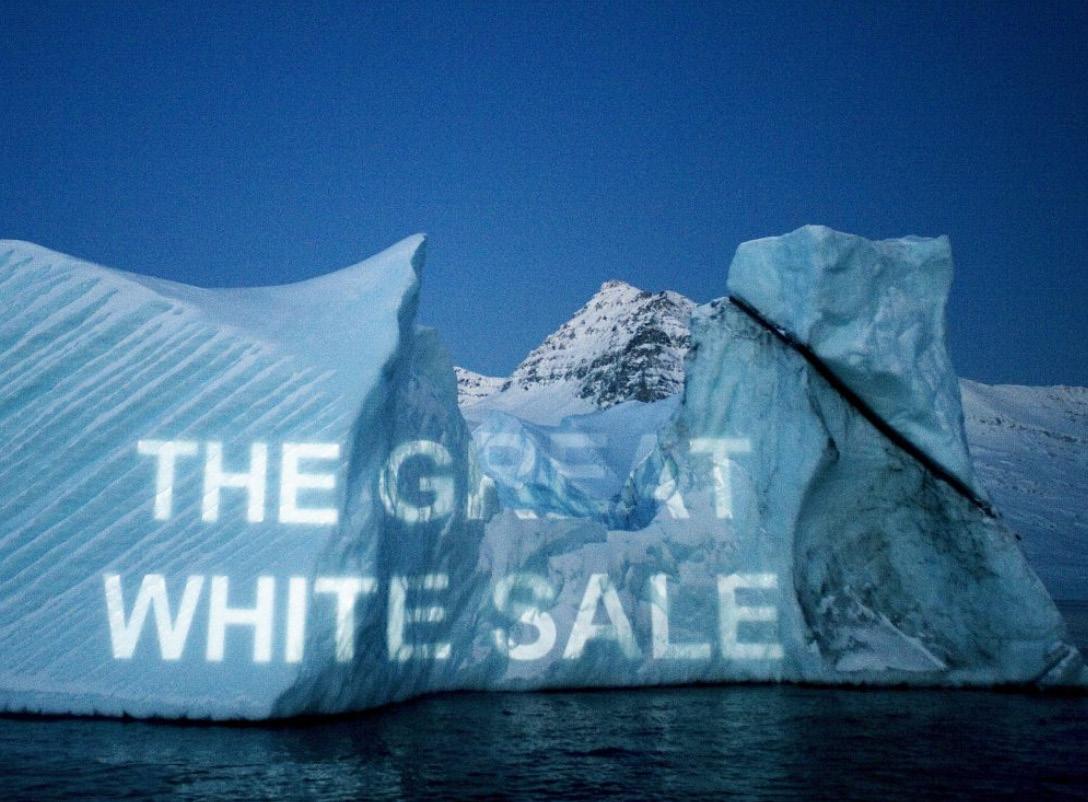

The negative influence of humans on the climate and the environment is well established, and it has led to our current ecological age, The Age of the Antrhopocene.

The way we've chosen to live and build has undeniably contributed to this regrettable and potentially disastrous age.

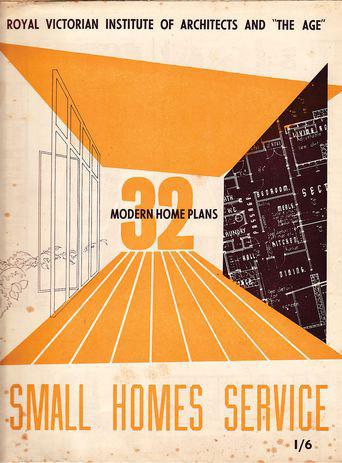

In the years after WW2 Architects reconsidered what it meant to live in Australia out of pure necessity.

A way to house ex-servicepeople and their families in affordable, well designed homes amidst a materials and housing shortage, was born out of revolutionary programs such as The Age Small Homes service8.

We have since gone backwards, as housing choice has diminished, and the problem we now face is environmental, economic, health-related, social and aesthetic, and it is increasingly dire, as 70% of Australia’s population now live in the suburbs9.

I grew up in some of Victoria’s earliest suburbs, both Carrum Downs and Frankston South, where my Lebanese migrant family operated neighbourhood Milk Bars, a once iconic mainstay of successful suburbs.

“The Great Australian Dream” we excitedly moved here in search of remains the dream for many. Let's prevent it from becoming a nightmare.

The amenity that made low density suburbs so desirable to begin with has all but disappeared. New suburbs are often disconnected from their surroundings and increasingly car reliant. The deep seeded cultural aspirations of most Australians helped spawn our favoured recipe for housing, but it is having increasingly negative impacts, all of which could be addressed by reconsidering our values through more holistic and integrated design approaches across the board.

The economic and political climate which created this Australian Suburban condition are beyond the scope of this Manifesto but are equally problematic and worthy of critique10.

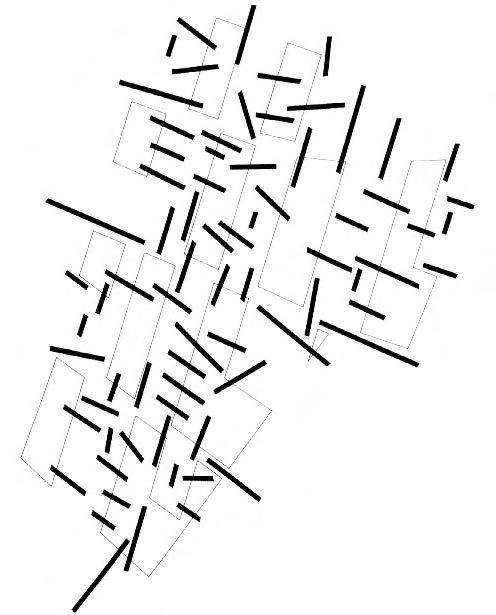

The Tabula Rasa, or clean slate, method of outer suburban development dominating our country, and many others, is environmentally unsustainable and unadaptable11.

It lacks both identity and amenity, while creating isolated experiences for residents. New homeowners have difficulty fostering a sense of community and place, and their wellbeing12 is negatively impacted as a result.

How can a suburb flourish and thrive if it’s doomed to fail before it’s built?

A series of scalable and repeatable interventions is proposed for the design of new low density suburbs at the overall planning (macro) level to foster inclusion and connectivity rather than seclusion.

•

Build flexibility and the ability for suburbs to adapt into neighbourhoods. Various scales of land parcels will allow for changing needs and dwelling types to be accommodated, as too frequently large family homes are the only choice.

• Break up strict land zoning to allow for mixed use precincts13. Commercial zones and shared workspaces will reduce increasingly long commutes to places of employment, retail and leisure.

• Encourage adaptive reuse of existing infrastructure (natural and built) to maintain the existing identity of places and increase pride of place.

•

Integrate alternative energy modes and transport, minimising fossil fuel reliance/energy bills /soften the harsh brutalscape14 (heavy infrastructure) often necessary for new suburbs in fringe areas. Install geothermal heat pumps, so suburbs can benefit from a shared cooling/heating system installed prior to the building of homes.

Fig 50

• Provide for self driving cars and future technologies, so that suburbs can become models of healthy, low carbon footprint living, not the opposite.

• Covenants in land titles mandate clean energy and materials in construction, and planting of native vegetation in landscaping. Incentivise and reward construction that exceeds these requirements.

Siting of land zones will be driven by climate data informed orientation and natural features of the site, not by yield or density maximastion. Views and provision of shared amenities/creation of privacy where needed will also drive overall planning.

Brownfield sites, areas that had previously been developed or used, must re-integrate planting and landscaping to create regenerative and repairing green areas and open spaces16, while assisting to preven the effects of climate change on suburbs, and creating new habitats for wildlife to return to.

•

Walkable access (within 600m) to a variety of shared public amenities, playgrounds, public transport, schools, sports facilities, libraries etc. must be considered from the outset to ensure a healthier, amenity rich and well connected suburb17 . • Connect to

These interventions, when combined with the smaller scales of planning (at street and home scale) will prepare new suburbs for the future challenges they, and Australian cities at large, are increasingly likely to face.

Typically new suburbs in Australia are lined in strips, the nature strip, occasionally the median strip, if you’re lucky a strip of shops, and increasingly strips of homes that look exactly the same.

Project homes with strips of thin veneers that create the appearance of difference, but are selected from the same catalogue used in another state with a completely different climate18.

We need to make streets, the lifeblood of our suburbs, places that people look forward to walking down, encourage community and foster neighbourly relationships19 as the influence of the street on suburban comfort and contentment is well documented20.

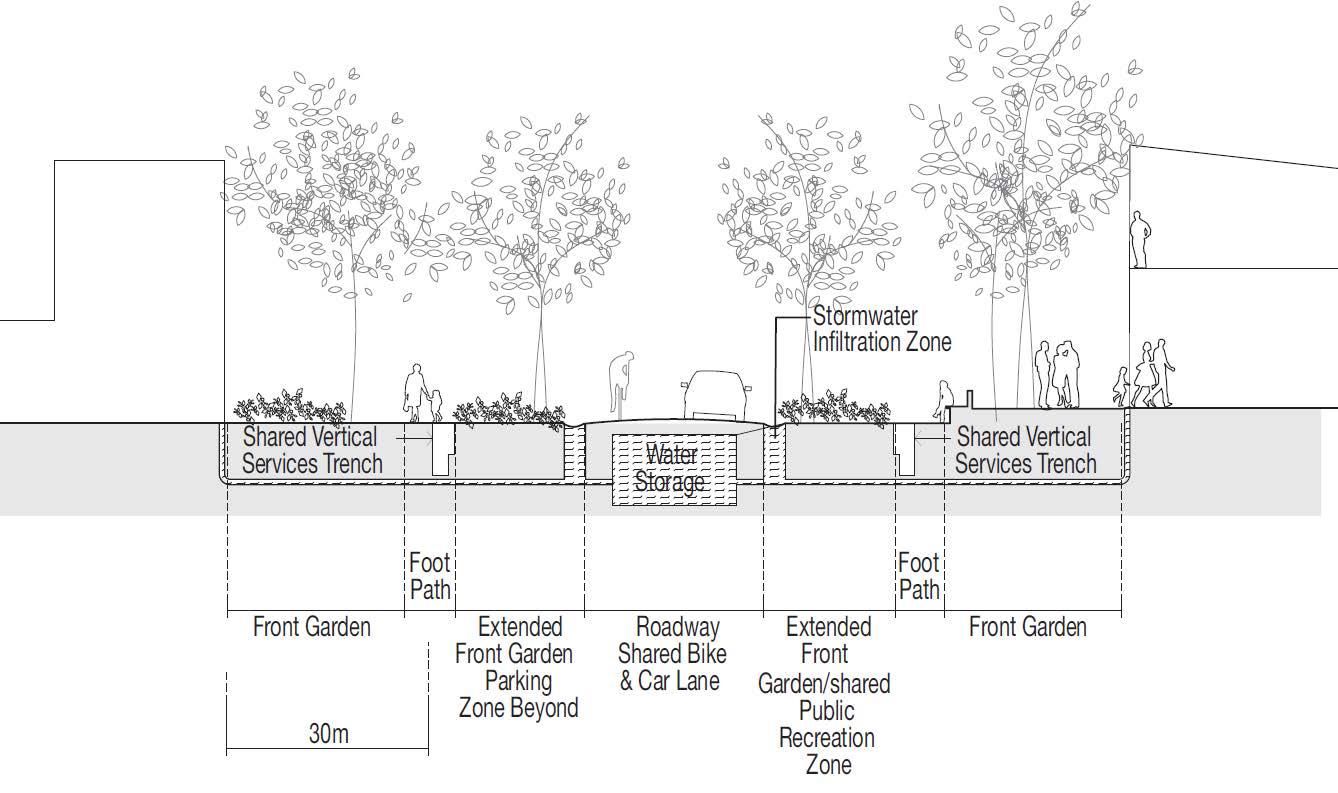

•

Streets will have shared parking spaces for those with their own cars, toward the south of properties and out of view. Shared electric cars will reduce individual car ownership, returning valuable space and amenity to residents and communities.

• Encourage physical activity and walking. Garage doors should no longer dominate street frontages21 as the size required to store a single car equates to a usable living space. Streets will have shared parking spaces for those with their own cars, toward the south of properties and out of view. Return valuable space and amenity to residents and communities.

Widen the nature strip and encourage planting of edible plants and native vegetation, manicured grass lawns that people often park their cars on aren’t good enough. Surround homes with planting to create a sense of separation and privacy that may be lost after removing high fences.

Fig 72 Fig 73

• Reduce hard surfaces to mitigate stormwater runoff while allowing deep soil tree planting.

Encourage diversity in streetscapes and remove the stigma of congregating or enjoying the shared space of the street. Integrate a diversity of street furniture for different levels of ability and different functions (bike parking, tables, seating, outdoor workshops/ sheds, and exercise equipment).

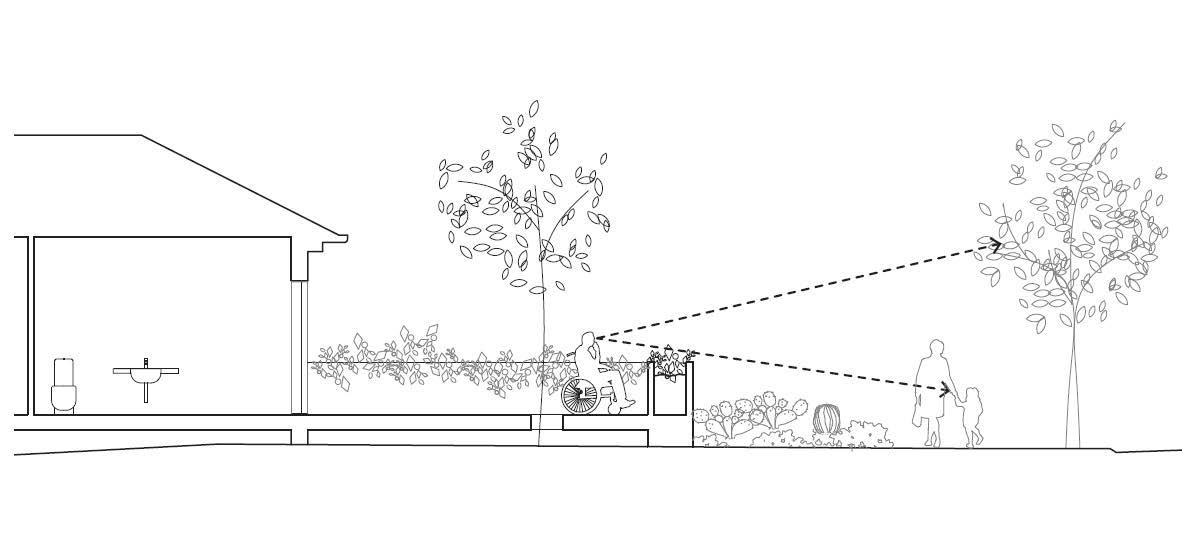

• Promote passive surveillance towards the street. Visibility between homes and the street increases a sense of security and connectedness.

Encourage planning that creates memorable differences between streets and a sense of identity and place based on the natural qualities of the site, solar orientation and view.

Together, these interventions will return the ownership of streets to residents, as difference, community, usability and genuine natural features will make them a more pleasant and sustainable place.

The large swathe of street area required for suburbs will no longer be domainated by cars and unusable, often ill considered space, but will be an extension of residents home, for use as they see fit.

We simply can’t afford, economically or ecologically, to keep building the way we do.

Our homes are too big22, and they’re pushing us further and further away from established infrastructure. Other, equally important factors are being negated in our quest for this Aussie dream.

An holistic approach to design in which siting, construction, form and scale are considered together will unify home design and create a more reasoned architectural suburban language based on longevity, connection and place.

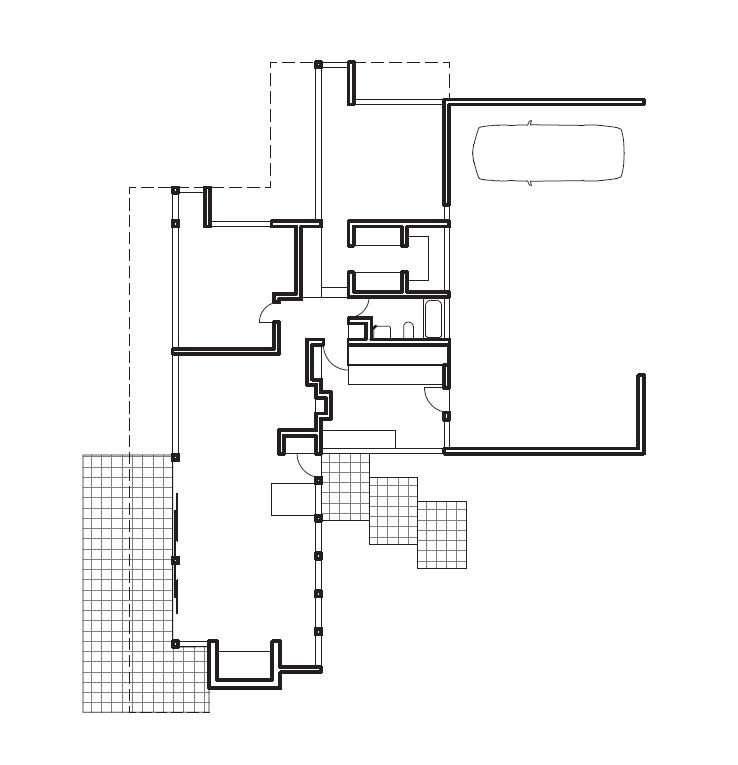

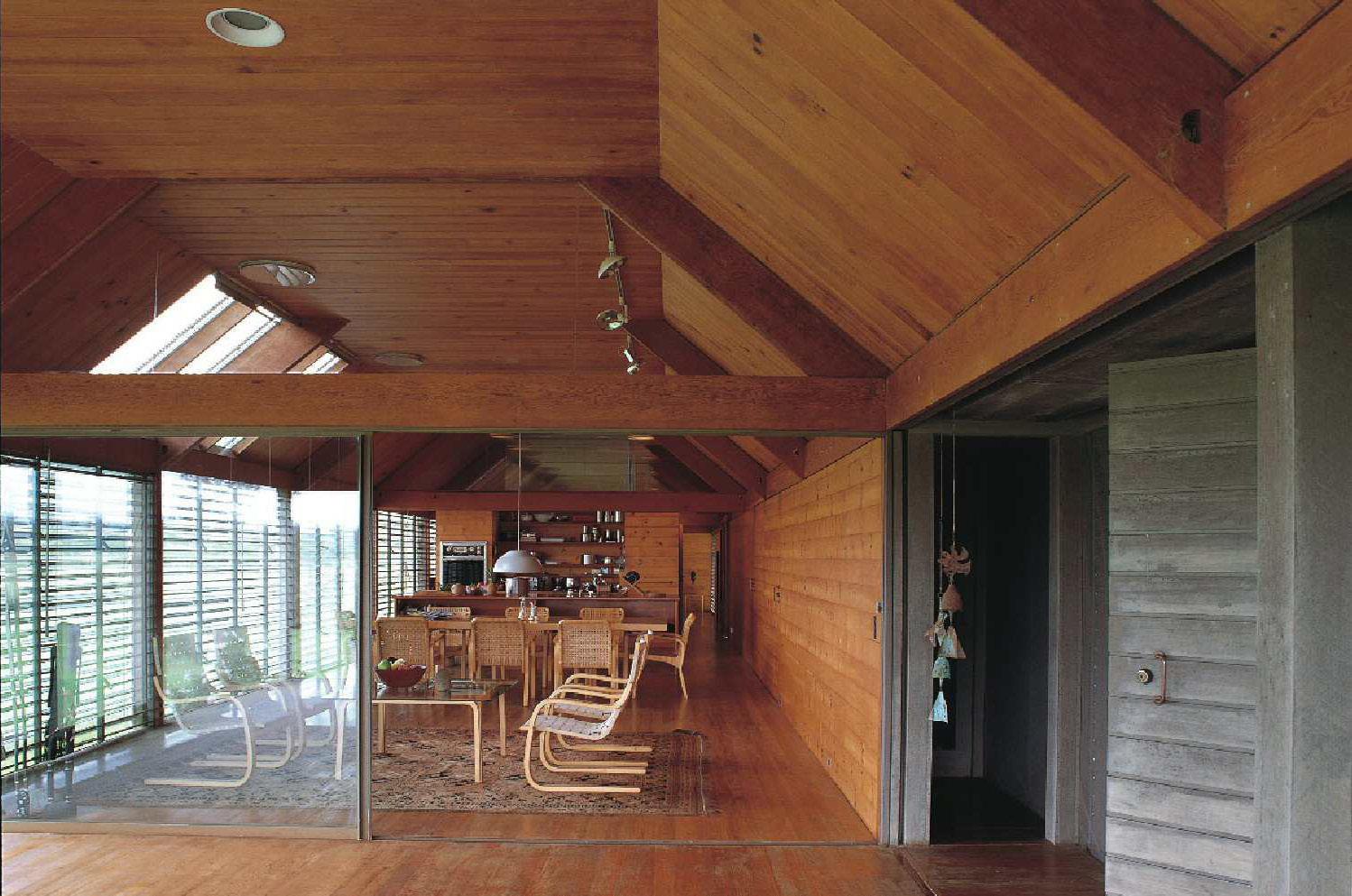

Fig 111

Fig 112

Encourage diversities of home scales from studios to 4 bedroom family homes. Dwelling diversity will bring owner diversity and encourage people to stay in the suburb23 .

• Homes will anticipate adaptation, encouraging residents to age in place or easily modify their homes to meet their changing needs. Frequently moving has been found to negatively impact resident wellbeing as well as the success of suburbs24 .

• Design homes in accordance with Liveable Housing Guidelines as many of us will develop mobility issues throughout our lives, temporarily or permanently25 . This will enable ageing in place, without the need for costly renovations

Prefabricated homes built off site will minimse waste, energy, and construction time, while allowing for precision building, and reduction of acoustic disturbance in suburbs. New recyclable materials will combine insulation, cladding and structural support in one element, reducing the number of building elements required.

• Modular home designs adapted to suit natural conditions, user requirements, and different contexts, unlike current off the plan homes. Ban difficult to recycle, and unsightly toxic veneers. Use local materials and construction systems, in turn supporting nearby industries and businesses while encouraging others to open.

The design of the individual home, rethought, repeated and modified to suit each resident's indiviudal needs will undoubtedly improve suburban living and our relationship to/impact on the environment. To, yet again, quote Robin Boyd “good living is the recognised motivation behind practically all thoughtful architecture and design”29.

"No it won't, let's get on with it!"

We have unwittingly created problems for ourselves and future generations through naive planning, from the scale of the suburb, down to the home.

Although the situation I have painted seems dire, we should see these well documented design problems as opportunities for longlasting solutions rather than something we’re stuck with.

As a society we can create the suburbs we want to live in.

Suburbs we won’t want to leave.

Unique, thoughtful and responsible places that adapt to our changing needs, whilst creating new sustainable communities that don't damage the natural environments they are built on.

Connected and considered suburbs, at all scales, may be just what we need, and perhaps in turn a healthier New Australian Dream is what we will get.

1 - Sitch, Rob, director. The Castle. Working Dog Productions, 1997.

2 - Kelly, J.-F, Breadon, P., Mares, P., Ginnivan, L., Jackson, P., Gregson, J. and Viney, B. (2012) Tomorrow’s Suburbs, Grattan Institute: 4.

3 - Boyd, Robin. The Australian Ugliness . Melbourne: F. W Cheshire, 1960. 11.

4 - Weller, Richard. “Whatever happened to (Australian) urbanism?,” Architec ture Australia , September/October 2019. 18.

5 - Housing Industry Association (HIA), Window into Housing 2020, Australian Capital Territory.

6 - Kelly et al, “Tomorrow’s Suburbs,” 15.

7 - Freeland, J. M. Architecture in Australia: A History. Ringwood, Victoria: Pel ican Books, 1974. 286.

8 - Boyd, Robin. The Walls Around Us: A popular history of Australian Architec ture. Melbourne: Angus & Robertson, 1982. 121.

9 - Abass, Zainab I, and Tucker, R. “Talk on the Street: The Impact of Good Street scape Design on Neighbourhood Experience in Low-density Suburbs.” Hous ing, Theory and Society (2020). doi: 10.1080/14036096.2020.1724193. 1.

10 - Pawson, H., Randolph, B., Leishman C. “After COVID, we’ll need a rethink to repair Australia’s housing system and the economy, ”The Conversation, Sep tember 2020.

11 - Kelly et al, “Tomorrow’s Suburbs,” 17.

12 - Department of Health 2015, The Victorian Happiness Report: The subjective wellbeing of Victorians, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne.

13 - Kelly et al, “Tomorrow’s Suburbs,” 22.

14 - Magin, Paul J., Keil, Roger. “The Suburbs can help cities in the fight against climate change,” The Conversation, December 2019. https://theconver sation.com/the-suburbs-can-help-cities-in-the-fight-against-climatechange-127663.

15 - Allen, Stan. Points and Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City. New York, USA: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999. 92-93.

16 - Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam. “Natural Sprawl.” Administration Society vol 48(9) ( 2016): 1128-1150, doi: 10.1177/0095399714527755. 1133.

17 - Abass et al “Talk on the Street: The Impact of Good Streetscape Design on Neighbourhood Experience in Low-density Suburbs.” 18.

18 - “Artisan Designer Homes.” Metricon.com.au, accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.metricon.com.au/New-Home-Designs/Melbourne/Artisan? photo=artisan_atlantic_1.jpg&floorplan=56

19 - Abass et al, “Talk on the Street: The Impact of Good Streetscape Design on Neighbourhood Experience in Low-density Suburbs.” 4,18.

20 - Abass, Zainab I, and Tucker, R. “Residential satisfaction in low-density Aus tralian suburbs: The impact of social and physical context on neighbourhood contentment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 56 (2018): 36-45, doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.02.005. 43.

21 - Freeland, J. M. Architecture in Australia: A History. Ringwood, Victoria: Peli can Books, 1974. 283-286.

22 - McMullan, Michael and Fuller, Robert. “Spatial growth in Australian homes (1960–2010)." Australian Planner, vol. 52, Issue No. 4 (2015): 314-325, doi: 10.1080/07293682.2015.1101005. 319.

23 - Kelly et al, “Tomorrow’s Suburbs,” 8, 17.

24 - Department of Health 2015, The Victorian Happiness Report: The subjective wellbeing of Victorians, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne. 43.

25 - Kelly et al, “Tomorrow’s Suburbs,” 37.

26 - Bertram, Nigel and Murphy, Catherine. “The Space of Ageing,” Architecture Australia, May/June 2018. 46-50.

27 - Okulicz-Kozaryn, Adam. “Natural Sprawl.” Administration Society vol 48(9) (2016): 1128-1150, doi: 10.1177/0095399714527755. 1131-1133.

28 - Gusheh, Maryam, Heneghan, Tom, Lassen Catherine, Seyama, Shoko. Glenn Murcutt: Thinking Drawing / Working Drawing. Tokyo: TOTO Publishing, 2015. 23.

29 - Boyd, Robin. Living in Australia. Victoria: Thames and Hudson. 2013. 22.

Fig 1 - Greg Stimac, “Oak Lawn, Illinois,” 2006. Inkjet Print. Source: Artists website, accessed 3 November, 2020, https://www.mocp.org/detail. php?t=objects&type=tag&f=413&s=&record=0&tag=

Fig 2 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of home in Springvale, Victoria,” January 2019.

Fig 3 - “Aerial Image of Clyde VIC 3978, Australia.” Digital image. nearmap. August 30, 2020. Accessed September 9, 2020. http://maps.au.nearmap.com/

Fig 4-11 - Author’s own photographs, “Image of new homes in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2019.

Fig 12 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of home in Richmond, Victoria,” 2019.

Fig 13 - Ian Strange, “SOS from Island Series,” 2015-2017. Photograph. Source: Artists website, accessed 10 October, 2020, https://ianstrange.com/works/ island-2015-17/gallery/

Fig 14-21 - Author’s own photographs, “Images of letterboxes in Frankston/ Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 22 – David Buckland, “Another World is Possible, Ice Texts,” 2018-2010. Photograph. Source: Art Almanac website, accessed 3 November, 2020, https:// www.art-almanac.com.au/david-bucklands-ice-texts-the-effects-of-climatechange/cenlf25uuaaol5t/.

Fig 23 – Robin Boyd, “Small Homes Services booklet cover,” Image from Robin Boyd Foundation. Source: Architecture Australia website, accessed November, 2020. https://architectureau.com/articles/what-would-boyd-do/

Fig 24 – Wolfgang Sievers, “Residence designed by the RVIA Small Homes Service in conjunction with ‘The Age’ newspaper, north-east corner of Union Road and Varzin Avenue, Surrey Hills,” 1995. Photogaph. Source: Arts Review website, accessed November 3 2020, https://artsreview.com.au/why-old-is-new-againthe-mid-century-homes-made-famous-by-dons-party-and-dame-edna/

Fig 25 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of development in Carrum Downs, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 26-33 – Author’s own photographs, “Images of real estate advertising in Frankston East/Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 34 – Author’s own photograph, “Image of Milkbar in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 35 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of my family in Frankston North Milkbar, Victoria,” 1999.

Fig 36 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of my family in Frankston North milkbar, Victoria,” 1996.

Fig 37 – Howard Arkley, “House and Garden, Western Suburbs, Melbourne,” 1988. Synthetic polymer paint on two canvases. Source: Arkley Works website, accessed November 3 2020. https://www.arkleyworks.com/blog/2009/11/21/ house-and-garden-western-suburbs-melbourne-1988/

Fig 38 - “Aerial Image of Frasers Rise, VIC 3335, Australia.” Digital image. nearmap. October 12, 2009. Accessed September 9, 2020. http://maps.au.nearmap.com/

Fig 39 - “Aerial Image of Frasers Rise, VIC 3335, Australia.” Digital image. nearmap. December 5, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2020. http://maps.au.nearmap.com/

Fig 40 - Jun Cen, “untitled from The suburb of the future, almost here article.” 2017. Digital illustration. Source: The New York Times, accessed 10 October, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/15/sunday-review/future-suburbmillennials.html

Fig 41-48 – Author’s own photographs, “Detail Images of street plants in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

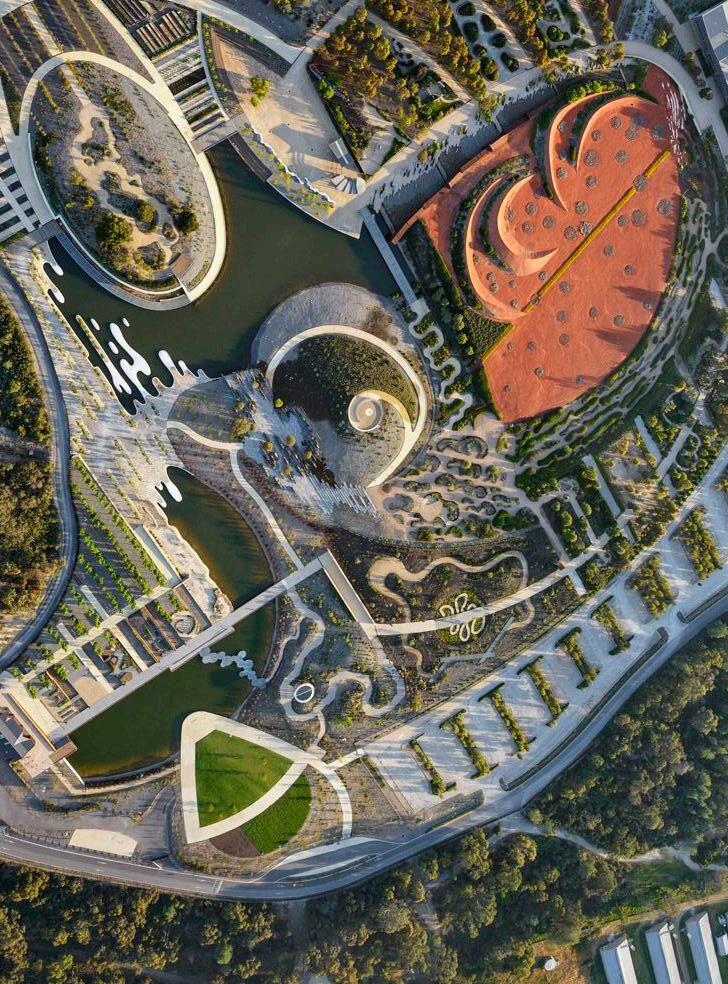

Fig 49 – Mcgregor Coxall. “Little Bay Cove project, Charter Hall Group. Little Bay, NSW 2008-2012”. Photograph. Source: Mcgregor Coxall website, accessed November 10 2020,https://mcgregorcoxall.com/helpdesk/SuperContainer/ Files/ProjectSheets/0165SL/LITTLE%20BAY%20COVE.pdf

Fig 50 – Google, “Google self driving car.” Digital Image. 30 May, 2014. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/may/28/ google-self-driving-car-how-does-it-work

Fig 51 – 5 Foot Photohraphy, “Michael Dysart house in Wybalena Grove, ACT 2902.” Digital image. Date unknown. Accessed November 12, 2020. https:// designcanberrafestival.com.au/event/design-revisited-architect-michaeldysart/

Fig 52 – “Aerial Image of Urambi Village (Crozier Circuit) by Michael Dysart, ACT 2902, Australia.” Digital image. nearmap. October 12, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2020. http://maps.au.nearmap.com/

Fig 53 – Stan Allen, “Stitch Map in Points and Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City.” Diagram. New York, USA: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

Fig 54 – Archdaily, “The Australian Garden / Taylor Cullity Lethlean + Paul Thompson.” Digital Image, John Gollings. June 28, 2013. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://www.archdaily.com/393618/the-australian-garden-taylor-cullitylethlean-paul-thompson

Fig 55 – Level Crossing removal project, “Carrum station foreshore park.” Digital Image, photographer unknown. October 15, 2020. Accessed November 11 2020. https://levelcrossings.vic.gov.au/media/news/your-new-carrum-foreshorepark-now-open

Fig 56 – “Aerial Image of Clyde, VIC 3978, Australia.” Digital image. nearmap. October 7, 2019. Accessed September 9, 2020. http://maps.au.nearmap.com/

Fig 57 – Delaray, Clyde North, “Hamptons-style townhomes by Porter Davis,” 2018. Digital rendering. Source: Villawood Properties, accessed 10 October, 2020, https://villawoodproperties.com.au/community/delaray/find-buy/porter-davistownhouses/

Fig 58-62 – Author’s own photographs, “Images of elements in the street in Frankston East and Carrum Downs, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 63 – Nigel Bertram and Leon van Schaik, “Five Dock Lineal Park by Neeson Murcutt Architects, 2007” Cross section drawing. Source: Suburbia Reimagined: Ageing and Increasing Populations in the Low-Rise City, 121.

Fig 64-71 – Author’s own photographs, “Images of garages presented to the street in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 72 – Author’s own photograph, “Image of modified nature strip in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 73 – Author’s own photograph, “Image of modified nature strip with native planting in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 74-81 – Author’s own photographs, “Images of elements in the street pavement in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 82 - Anna Gorman, “Anne Street Garden Villas” 2019. Digital rendering. Source: Anna Gorman Website, accessed 05 November, 2020, https://www.annaogorman.com/anne-street

Fig 83 – Nigel Bertram and Leon van Schaik, “Accessible Garden House, Northeast Melbourne, 2017.” Cross section drawing. Source: Suburbia Reimagined: Ageing and Increasing Populations in the Low-Rise City, 52.

Fig 84-91 - Author’s own photographs, “Detail images of tree trunks in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

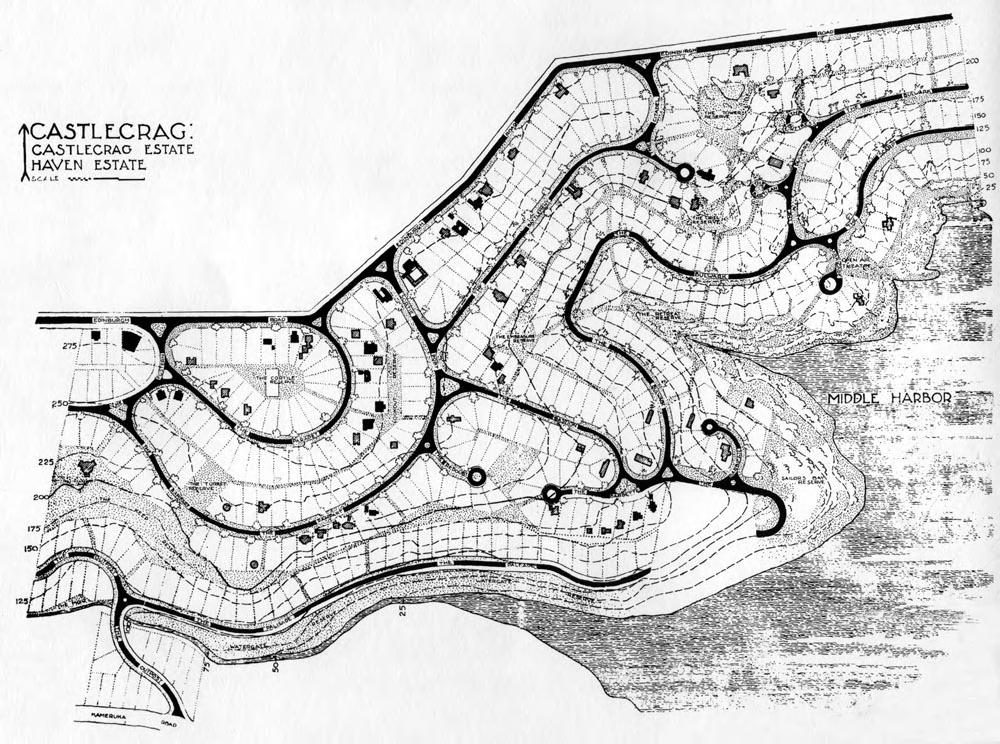

Fig 92 – Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin, “Castlecrag Estate, NSW ” Plan. 1932. Accessed November 10, 2020. https://abc17603.wordpress.com/history/ suburbs/castlecrag/

Fig 93-100 - Author’s own photographs, “Images of road safety signs in Frankston and Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 101 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of asphalt road in Carrum Downs, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 102 - Author’s own photograph, “Image of development in Carrum Downs, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 103-110 - Author’s own photographs, “Images of home fences to the street in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 111 – Neuefocus, “Case Study House 20 exterior.” Digital Image. Source: Galerie Magazine Website. July 20, 2020. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://www.galeriemagazine.com/richard-neutra-bailey-house-real-estate/

Fig 112 – Nigel Bertram and Leon van Schaik, “Case Study House 20 by Richard Neutra. Los Angeles, USA 1945-1966.” Source: Suburbia Reimagined: Ageing and Increasing Populations in the Low-Rise City, 15.

Fig 113-120 - Author’s own photographs, “Images of post war suburban in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 121 – Allen Kong Architects, “Castlemaine Wintringham - Alexander Miller Memorial Homes.” Digital image. Wintringham. May 14, 2012. Accessed September 9, 2020. https://www.wintringham.org.au/castlemaine.html

Fig 122 – MAS. “Adaptable House.” Floor Plan. Antarctica Architects. 2020. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.monash.edu/mada/research/habitat21-adaptable-house

Fig 123-130 - Author’s own photographs, “Images of street elements in Frankston South, Victoria,” 2020.

Fig 131 - Wilson, A, Wilson, C. “lean to house.” Digital image. warc. February 8, 2016. Accessed September 09, 2020. http://www.warc.com.au/oakleigh-residence

Fig 132 – Peter Stutchbury and Oscar Martin, “Dimensions X prefab home interior.” Digital Rendering. 2020. Source: Domain website, accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.domain.com.au/living/architect-peter-stutchbury-andpedestrian-tv-co-founder-oscar-martin-launch-sustainable-homesproject-992603/

Fig 133 – Rory Gardiner, “Interior of Repair (Australian Pavilion) at the 2018 Venice Biennale by Baracco+Wright Architects in collaboration with Linda Tegg.” 2018. Photograph. Source: The Planthunter website, accessed 11 November, 2020, https://theplanthunter.com.au/people/life-lessons-artist-linda-tegg/

Fig 134 – Anthony Bowell, “Interior of Marie Short House by Glenn Murcutt (1975), renovated in 1980.” 2019. Photograph. Source: Ozetecture website, accessed 11 November, 2020, https://www.ozetecture.org/marie-short-glenn-murcutthouse

Fig 135 - Anna Gorman, “Social housing demonstration project in Southport QLD” 2020. Digital rendering. Source: Architecture Australia, accessed 10 October, 2020,https://architectureau.com/articles/home-building-and-renovationgrant-scheme-misses-the-mark-says-institute/#:~:text=The%20federal%20 government's%20%E2%80%9CHome,the%20Australian%20Institute%20 of%20Architects