Mexican Power

Reivindicating the community’s value to the USA

MEXICO IS HAPPIER;

THE US IS NOT AS HAPPY

ness in Mexico, individualism has the opposite effect in the U.S.

For the first time since the creation of the World Happiness Report in 2012, Mexico ranks among the top 10 happiest countries in 2025. Meanwhile, the United States has reached its lowest position in history, ranking 24th among the 147 nations in the report

BY ANGÉLICA SIMÓN UGALDE ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

The World Happiness Report, along with the increasing interest in well-being research, owes its existence to Bhutan, the nation that championed Resolution 65/309 (Happiness: Towards a Holistic Approach to Development), which was adopted by the UN General Assembly on July 19, 2011. This resolution called on governments to prioritize happiness and well-being when defining and measuring social and economic development.

This report is the most important publication on global well-being and ways to enhance it. Indeed, happiness matters. It is directly linked to the satisfaction and well-being individuals experience in their lives. Currently, in Mexico, people view themselves as happier, while in the United States—the main destination for Mexicans who decide to leave their home country—happiness is declining.

According to the World Happiness Report 2025, coordinated by Oxford University, Gallup, and the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), Mexico is now ranked among the ten happiest nations in the world.

In 2024, Mexico ranked 25th, indicating that the perception of happiness among Mexicans rose 15 spots in just one year. Experts from the report cite strong family relationships, close support networks, and social assistance as key factors contributing to this improvement.

Regarding Mexico’s position in the World Happiness Report 2025, the Mexican president, Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo, emphasized during the morning presidential press conference on March 20th—the International Day of Happiness—that this reflects the Mexican people’s empowerment.

Mexico is ranked ten in this list, and countries such as Finland, Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden appear among the first places.

THE UNITED STATES: A DROP IN HAPPINESS In the land of the "American Dream," how happy are people according to this report? The finding is surprisingly different: the United States ranked 24th, marking its lowest position in the history of this report. While family is a key factor in happi-

Finland is ranked as the happiest country in the world, while Afghanistan remains the least happy.

The report emphasizes that the percentage of individuals eating alone in the U.S. has risen by 53% over the last twenty years. Experts connect this trend with feelings of loneliness, social disconnection, and decreased overall happiness.

Another important global trend affecting happiness is the tendency to live alone. Living in solitude diminishes personal satisfaction and heightens feelings of isolation and anxiety.

"Happiness isn’t solely defined by wealth or success; it’s rooted in trust, connection, and the assurance that there are people who support you", expressed Jon Clifton, CEO of Gallup.

This year, the report emphasizes that our happiness relies on our social connections. Building and nurturing shared communities is crucial for enhancing our well-being. The key takeaway from the report highlights the significance of human connections.

Costa Rica in 6th place and Mexico in 10th place.

The global happiness ranking is based on a question from the Gallup World Poll: ‘Please visualize a ladder with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top symbolizes the best possible life for you, while the bottom signifies the worst possible life. On which step of the ladder would you say you currently stand?’ Readers, where would you place yourselves on this ladder?

02/03

/ 03 / 24 / 2025

"Research indicates that we tend to be happier when we think about others and show our care for them. Moreover, there are ways to multiply the joy of giving. People, both globally and within our own communities, are more inclined to help one another than we realize," said Jon Clifton during the report’s presentation.

MIGRATION: A FACTOR IN HAPPINESS

Since its first edition in 2012, the World Happiness Reports have explored various factors influencing global happiness, including age, generation, gender, sustainable development, benevolence, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on overall well-being, and migration.

In 2018, the report ranked 156 countries according to happiness levels and assessed 117 countries based on the happiness of their immigrants. That year, alongside its standard ranking, the report also addressed migration both within and between countries.

That study indicates that the ten happiest countries in the world have higher-than-average proportions of migrants. In 2015, these nations had a foreign-born population of around 18%, which is more than double the global average of 8.7%.

These countries not only have the happiest populations but also boast the happiest immigrants. When ranking countries by the happiness of their immigrants, the top ten mirror the overall happiest nations.

Several factors contribute to this outcome, including the appeal of these nations as destinations for migrants, the friendly nature of their citizens, and their greater ability to integrate newcomers into society.

Many migrants find greater happiness, particularly those who can meet their basic needs or achieve their dreams in their new country. However, the journey is not always smooth, as migration often involves leaving behind crucial sources of happiness, such as family, a central theme in the 2025 report.

Two Latin American countries reached the Top Ten:

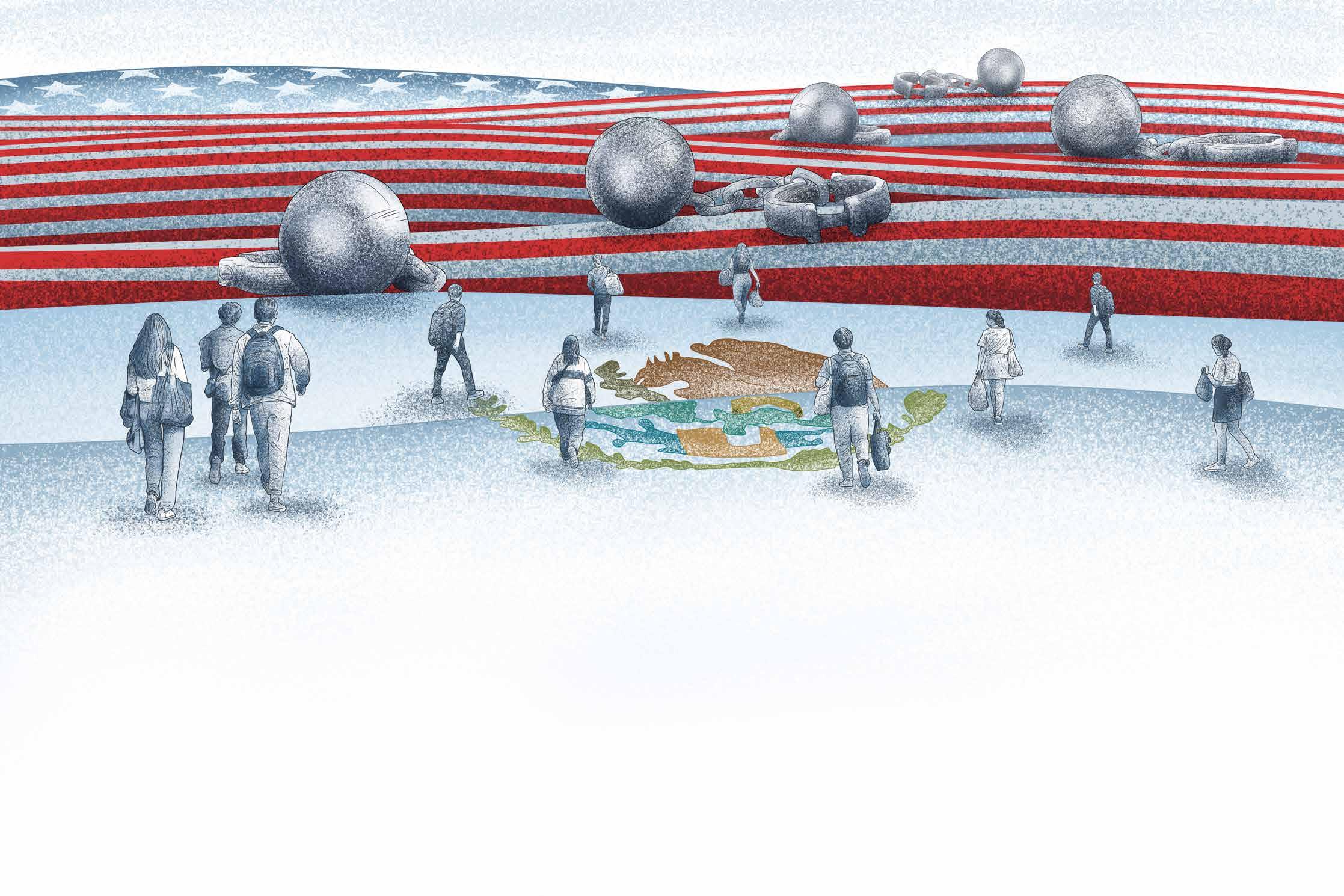

The power of the Mexican community in the United States

THE MEXICAN COMMUNITY IS ESSENTIAL TO THE U.S., YET FACES EXCLUSION. JAIME LUCERO URGES UNITY, REFORM, AND RECOGNITION OF MIGRANTS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

This year marks 50 years since I arrived in the United States. I am part of the great Mexican community that, despite its diversity, is defined by its collective strength—business owners, entrepreneurs, workers, farmers, activists, athletes, and millions of children who live in constant fear that their parents will be deported.

We are all reflections of a shared reality that has not been fairly represented in this country’s immigration policies.

My story is not just one of personal effort but of millions of Mexicans who came to this land seeking a better future and who, through decades of hard work, have contributed to the economic, social, and cultural development of the United States.

However, today, we face a scenario in which immigration policies are based on fear and exclusion, ignoring our contributions. The dehumanization we experience daily has become a dominant trait in public discourse about migrants, even though we are an essential part of American society.

“Criminalization” should not be our primary concern in this context. The issue runs more profound than the legal labels placed upon us. The fundamental problem lies in how we are perceived—as a threat, as an “other” whose humanity is denied.

This perspective not only stigmatizes undocumented migrants but also all those who, because of their origin, are constantly reduced to negative stereotypes. With nearly 40 million Mexicans in the United States, this dehumanization affects not only our lives but also the potential of an entire nation that depends on our labor force.

We must recognize that our people are not an obstacle to the prosperity of the United States but a driving force for its growth. The discrimination we face today is rooted in racial, historical, and cultural prejudices. However, the solution does not lie in tightening immigration policies or fostering fear of our presence. Actual change will only come when our contributions are acknowledged and we are allowed to participate fully in the development of this nation. Through its work, entrepreneurship, and culture, the Mexican community in the United States is an economic and social pillar that sustains and strengthens this country. I also know firsthand how immigration policies can change the lives of millions. In 1986, the amnesty that allowed more than three million undocumented migrants—including myself—to regularize their status marked a turning point. This amnesty grant-

ed us legal status and opened the doors to full integration into the American economy and culture. It allowed us to be recognized as full members of society, positively impacting our lives and those of future generations.

Today, we need not only comprehensive immigration reform but also social reengineering from a binational perspective. It is time to recognize that the ties between the United States and Mexico are not just geographic and economic but deeply human. The effective integration of Mexican migrants should not be seen as a challenge but as an opportunity, fostering spaces for collaboration and stregthening ties on both sides of the border.

We must recognize that our people are not an obstacle to the prosperity of the United States but a driving force for its growth.

Mexican migrants have never been a burden. We are an invaluable workforce that sustains and drives the growth of two nations.

Today, I work closely with young Mexicans and children of migrants studying at universities in the United States and Mexico to help them understand the importance of empowerment. Through Fuerza Migrante, we are creating spaces where these young people can learn about their rights and the impact they can have on public policy. We want them to feel proud of their roots and understand that they have the power to influence the

future of their community, both here and in Mexico. By embracing their identity, these young people become agents of change.

Over the years, I have witnessed how formal and self-taught education has been a driving force that allows migrants to advance and overcome the obstacles imposed upon us. We must not allow ourselves to be treated as second-class citizens. The solution is not exclusion but active inclusion, reflecting a binational vision for the future. Today, I call for unity. All voices in the Mexican community must join in this effort to change the narrative that has prevailed about us. We are a community that has not only sustained America’s progress but has also been a fundamental pillar of Mexico’s economy. Last year alone, we sent $64.75 billion in remittances—a historic record representing only a fraction of our immense contribution.

Our presence, work, and contributions should be celebrated, not condemned. It is time to move beyond racist rhetoric and pave the way for greater integration. We raise our voices not only for our rights but also for the recognition of our humanity and contributions. The power of our community is not just in our work but in our ability to change the course of history and prove that binational unity is our greatest strength.

* The author is President and Founder of Fuerza Migrante

Jaime Lucero

X: @JAIMELUCEROC

JAIME LUCERO

BY SUSANA MERCADO ALVARADO

IVAN BARRERA

In general terms, the Federal Court of Administrative Justice is the autonomous jurisdictional body of the Federal Judiciary responsible for ensuring that authorities’ actions, which may affect individuals’ rights, comply with established procedures and regulations. In essence, through legal proceedings, the court verifies that authorities do not commit errors or wrongful actions in their processes and decisions.

REGARDING ISSUES RELATED TO PEOPLE IN MOBILITY, THE COURT MAINLY HANDLES THREE TYPES OF CASES:

CLAIMS FOR STATE LIABILITY COMPENSATION: This occurs when a person in a mobility situation suffers a violation of their rights due to improper actions or omissions by migration authorities and files a claim for damages.

DENIALS FROM THE MEXICAN COMMISSION FOR REFUGEE ASSISTANCE (COMAR): This involves cases where COMAR issues a definitive ruling denying an individual’s request related to their migration status. The most common appeals are against denying regular residence in Mexico or refusing to recognize refugee status.

MISCONDUCT BY PUBLIC OFFICIALS: This

Out of a sample of 400 cases in which people in mobility situations report misconduct by Mexican authorities, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance and the National Institute of Migration stand out in first and second place, with 215 and 85 rulings, respectively. The three most common nationalities among people in mobility situations who turn

applies primarily to officials of the National Institute of Migration (INM) who violate the regulations governing their public service, committing administrative infractions. On rare occasions, the cases resolved by the court are related to human rights violations. To illustrate this, we will analyze the case of a Colombian migrant that was resolved a few years ago.

THE CASE OF THE COLOMBIAN MIGRANT A HUMAN RIGHTS PERSPECTIVE

In 2019, a Colombian migrant approached the court requesting compensation for damages after being wrongfully detained by migration agents for deportation to Colombia, despite having verbally asked for political asylum and entering the country with a non-immigrant visa for postdoctoral studies. He reported that his detention and transfer were carried out amid mistreatment and that he was illegally banned from entering Mexico for 40 years. After years of litigation—including legal appeals and lawsuits before the National Institute of Migration, the Ministry of the Interior, the Federal Judiciary, and the Federal Court of Administrative Justice—the

The Federal Court of Administrative Justice safeguards migrants’ rights, reviewing wrongful detentions and status denials. This case highlights the need for justice, empathy, and legal protection

A case of rights and resilience Justice for

court ruled in favor of the Colombian citizen, granting him state liability compensation exceeding 1.5 million pesos.

The plaintiff also requested comprehensive reparations for the damages caused by severe and systematic human rights violations. However, this request was denied, as the law governing state liability—which formed the basis of his claim—does not provide for such measures. International bodies, such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights rulings, typically grant these types of reparations.

EXPERT INSIGHTS: A LEGAL PERSPECTIVE

I interviewed lawyer Armando Medina Negrete, a dear colleague with whom I shared classrooms during our law school days—who, coincidentally, was responsible for working on the ruling in the Colombian case.

I asked for his thoughts on the challenges of handling a case like this.

“One of the main challenges in administrative justice is preventing the depersonalization of the cases we resolve. Many of the matters we handle at the court are strictly legal and procedural, which requires

objectivity. However, this should not lead us to the extreme of lacking empathy for the vulnerable situation of individuals seeking justice. A tax dispute is not the same as a case concerning migration status—especially when it involves the right to asylum, refugee protection, or family unity.

“This case highlights the greatest challenge: beyond legal formalities, we must empathize with the migrant’s vulnerability. These individuals are far from their home country, lacking advisors, resources, or family support. Recognizing that, by their humanity alone, they are protected by fundamental rights is essential. Behind every migrant case, there is a life story.”

CONCLUSION

This case underscores the urgent need to ensure that migrants are treated with dignity and respect and strictly comply with international treaties and national human rights laws.

Furthermore, it highlights the importance of providing free legal assistance and transparent access to information, preventing arbitrary detentions, and guaranteeing fair legal proceedings. A framework of international cooperation is essential to protecting migrants’ rights. Ultimately, civil society and institutions must work together to ensure that no migrant suffers violations of their fundamental rights.

to the tribunal are Hondurans, Venezuelans, and Colombians.

ON MARCH 21, WE COMMEMORATE THE BIRTH OF BENITO JUÁREZ. THROUGHOUT HISTORY, MEXICO AND THE UNITED STATES HAVE BEEN INTERTWINED THROUGH HIM, AS HE IS CREDITED WITH SEPARATING CHURCH AND STATE THROUGH THE REFORM LAWS FROM 1855 TO 1863. TODAY, WE TAKE A CLOSER LOOK AT THIS RELATIONSHIP.

JUÁREZANDTHEUNITEDSTATES

THE DREAM OF THE MUSEUM OF LA RAZA

In the memory of Chicago, the echo of an artist resonates—one who devoted his life to capturing in color the history, struggle, and identity of the Chicano people. José G. González, born in Iturbide, Nuevo León, and raised in the United States, was not only a tireless creator but also an activist who aimed to create opportunities for Mexican and Chicano art in a city that, despite its diversity, often pushed its culture to the margins. His legacy, now compiled in the book An Album for José González by scholar Marc Zimmerman, provides a journey through the life and work of this vital artist.

PAINTED CHICANO IDENTITY

in Chicago the artist who

José G. González was a Chicano artist and activist who devoted his life to promoting Mexican and Chicano art in Chicago. Through organizations such as MARCH and MIRA, he advocated for visibility and cultural identity, leaving a legacy now preserved in An Album for José González by Marc Zimmerman

THE AWAKENING OF AN ARTIST

González’s life was characterized by a continuous journey between cultures. In his youth, he served in the military and was deployed to Europe, where he discovered the transformative power of art in the museums of France, Spain, and Germany. In these venues, he encountered the works of Vincent van Gogh—an experience that left a lasting impression on him and sparked his passion for painting. Upon returning to the United States, he brought a renewed determination: to create art that reflected his own experiences and those of his community.

Hoping to deepen his roots, he spent six months studying in San Miguel de Allende, where Mexican muralism thrived under Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. This study period broadened his perspective and allowed him to create a style that combined academic technique with the expression of Chicano activism.

PILSEN AND THE FIGHT FOR CHICANO ART

In 1974, José G. González settled in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, a community that would become the heart of his work and activism. At that time, Chicano artists faced a constant challenge: the lack of venues to showcase their work. Recognizing this need, he founded the Chicano Artistic Movement (MARCH) in the 1970s, an organization dedicated to elevating Mexican and Chicano creators in the city. However, MARCH was insufficient. In the 1980s, González established the Mi Raza Arts Consortium (MIRA) to further promote Chicano and Mexican art in Chicago. Through his initiatives, he organized exhibitions in collaboration with institutions in Mexico, creating a bridge between artists from both countries and enhancing the cultural identity of the Mexican community in the United States.

One of González’s most ambitious projects was establishing a Museum of La Raza in Chicago. His vision was clear: a space where Chicano art could have a permanent home, enabling new generations to learn about their history and draw inspiration from the struggles of their people. He even gained support from then-Mayor Harold Washington, but after Washington’s passing, the initiative fell apart due to a lack of political support.

Despite this setback, González never wavered in his commitment to his community. He worked to rename Harrison Park in Pilsen to Zapata Park and successfully had a statue of the Mexican revolutionary leader erected at his home in the countryside. Throughout his career, his dedication to preserving historical memory and recognizing Mexican and Chicano identity remained steadfast.

A LEGACY AT RISK OF BEING FORGOTTEN

Marc Zimmerman’s book rescues the story of an artist who had begun to fade into obscurity over the years. The author’s decision to write about González came after persistent encouragement from colleagues and friends who believed his story deserved to be shared. Zimmerman’s interviews with González took place at various stages of his life, often in hospitals or transitional homes, as his health gradually declined.

In his final years, the artist battled Parkinson’s disease, which hindered his ability to paint. Nonetheless, his mind remained full of memories and anecdotes, which Zimmerman meticulously recorded and organized to shape a narrative that underscores González’s influence on the Chicano community and the art scene in Chicago.

A BEACON FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS José G. González passed away in 2022 at the age of 89, leaving behind a remarkable legacy. His work stands as a testament not only to the artistic talent of Mexicans in the United States but also to the significance of cultural activism as a catalyst for change. Although his dream of establishing a Museum of La Raza was never fulfilled, his struggle and vision continue to motivate new generations of artists and activists.

Zimmerman’s book serves as an essential tribute—a gateway for more people to delve into the story of this artist and his unwavering commitment to the Chicano community. As González himself believed, art not only beautifies but also shapes identity, memory, and the future.

Present since the early days of New Spain, industrial grape and wine production in Mexico is now evident in 17 states across the country, though in some areas, this activity remains quite nascent.

OF THE WINE INDUSTRY IN MEXICO THE CHALLENGES

BY: NORMA BORREGO PÉREZ ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

The culture of wine production intertwines with the unique geographical characteristics of each region, influenced by factors related to the landscape, history, gastronomic traditions, and various production methods. Both locals and visitors are often surprised by the presence of vineyards in Mexico, as at first glance, it may seem impossible to cultivate vines. However, the winemaking industry encompasses other key elements, such as soil composition—combinations of sand, gravel, red clay, and other materials that, when decomposed, interact with the seasons (e.g., humid winters and dry summers), shaping the essential “terroir” where the grapes are grown. Additionally, cultural practices and ancestral knowledge embedded in the farming techniques of each region play a vital role.

Although grape cultivation and winemaking have been documented in Mexico since 1593—when the first commercial winery was established in the city of Parras, Coahuila— both grape production and winemaking have remained somewhat marginal, especially compared to the promotion of other national beverages. Even though Mexico is the birthplace of wine in North America, it is also the newest commercial wine-producing region in the New World (Uncorkmexico, n.d., para. 2).

However, while there is an increasing demand for wine in Mexico—growing at an annual rate of approximately 10%—foreign wines from Spain, Argentina, and Chile still dominate the market. According to the Consejo Mexicano Vitivinícola (Mexican Wine Council, 2023), per capita wine consump-

tion in Mexico remains low, averaging just 1.2 liters per person per year. Additionally, Mexican wine meets only about 30% of the national demand. It is essential to cultivate a stronger wine culture and to recover and document the history of this industry in the country. This prompts us to reflect: How can the wine industry grow sustainably in the coming years? Below are some key challenges this sector faces in Mexico shortly.

ECONOMIC CHALLENGES

In Mexico, wines have high production costs, partly due to taxation. They are subject to two taxes: VAT (Value Added Tax) and the IEPS (Special Tax on Production and Services), with the latter being linked to the alcohol content of the product. This puts them at a disadvantage compared to wines from Argentina, Chile, and Spain, which are 30% to 40% cheaper than Mexican wines of similar quality. One of the biggest challenges is integrating technology and innovations that help reduce production costs while showcasing the unique local and regional characteristics of Mexican wines—i.e., their typicity. Other national-level challenges involve enhancing product quality, drawing in new consumer segments, and growing both domestic and international markets. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed various hidden vulnerabilities within the wine industry despite its over 400 years of history in the country. The most common ways to market wine in Mexico include:

A) Direct sales at the winery, often accompanied by guided tours of the facilities and vineyards.

B) Sales to the hospitality and food service

NORMA BORREGO PÉREZ

Expert at the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), Expert Group on Climate Change (Sustain) member, and recipient of the 2022 Gourmand Awards, 2023 OIV Award, and 2023 SADER Award.

This article is based on the introduction of the award-winning book “La industria vitivinícola mexicana en el Siglo XXI: retos económicos, ambientales y sociales” (CIATEJ, 2022), authored by Vásquez A., Borrego N., Herrera A., and Sánchez E.

industry, particularly hotels, restaurants, and catering (HORECA).

On a larger scale, distribution is dominated by supermarket chains, which advantage well-established wineries with high prestige. Meanwhile, family-owned and mid-sized wineries depend on their brand reputation but frequently lack concrete strategies for long-term market positioning.

ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES

In certain wine regions of Mexico, especially in the central areas outside the so-called “world viticultural belt,” vine cultivation thrives due to the vineyards’ altitude of about 2,000 meters above sea level. Therefore, it is crucial to promote research on possible ecological threats, such as plant diseases and pests, extended periods of intense sunlight, or extreme weather events like storms and hail.

In well-established wine regions, challenges include improving yield per hectare, optimizing production processes, enhancing irrigation efficiency, and training winery personnel—not only in technical fieldwork but also in administrative and customer service roles. For all regions, strengthening producer organizations is essential for addressing urgent environmental challenges, such as the 2019 wildfires in Baja California.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity to the environmental issues facing Mexican wine regions, particularly regarding water availability and quality, as it is closely linked to soil contamination and the overexploitation of aquifers. Climate variations could also promote the emergence of both existing and new pests, resulting in increased use of environmentally harmful products. However, the industry also offers oppor-

tunities for innovation. Using grape byproducts like pomace and seeds could create new commercial avenues. Furthermore, investing in sustainable practices—such as tracking the industry’s water and carbon footprints—would be advantageous. Given the large number of temporary jobs generated during harvest season (500,000 seasonal positions), the wine industry has the potential to promote the development of much-needed “green jobs” in Mexico.

SOCIAL CHALLENGES

Mexico’s wine regions, especially the most historic ones, face significant social challenges due to the growing urban expansion from nearby cities and metropolitan areas. Aside from the Sectorial Program for Urban-Tourism Development of the Northern Valleys of Ensenada Wine Region (published on September 14, 2018) and its regulations, there are no specific protections in Mexico for wine-producing areas that would preserve their ecological, landscape, and biocultural integrity. These regions provide essential ecosystem services that benefit both the industry and local communities, including natural soil protection and water resource conservation. The absence of legal frameworks negatively impacts related industries, such as wine tourism and gastronomy. It is essential to create legal instruments that establish clear and protected zoning regulations—serving as buffer zones—to ensure the optimal development of wine regions. Additionally, incorporating long-term planning into emerging wine-producing areas is crucial. Tools such as legal declarations for municipal or state-level protection zones could help preserve the cultural, historical, and natural heritage associated with the industry. Another pressing issue is social instability in certain areas of Mexico, which could affect the wine industry and its related sectors. A decrease in visitor numbers to popular wine tourism routes, as well as falling sales at these centers, could lead to significant economic consequences. Furthermore, incorporating minority groups—including women, young people, and indigenous populations—into local development agendas is crucial for achieving balanced growth in Mexico’s wine regions.

BY NAYELY RAMÍREZ ARTWORK: ALEJANDRO OYERVIDES

The iconic rock band Caifanes recently debuted a new track titled “Y caíste” (“And You Fell”), which they performed live for the first time during the 25th edition of the Vive Latino Festival, held at the GNP Stadium in Mexico City. The song, described as dark, was a creative challenge for the band members.

“There’s always some pressure around expectations. Whenever we work on something new, we try to block out the outside world—it’s not easy because it’s always in the back of our mind—but we try to walk into the studio or rehearsal space and leave everything else behind. Be as pure as possible, and not let those expectations influence our work,” said drummer Alfonso André in an interview.

He added: “It doesn’t matter what the industry expects from you, what other artists are doing, what your fans want you to do, or what’s trending on the radio or in the media. The goal is to leave all that behind and do your work as honestly and purely as possible—create something that truly captivates and convinces you before anyone else. What matters most is that we like it first. Then we release it, put it out into the world, and from there, it’s out of our hands.”

Caifanes took the main stage at Vive

CAIFANES WAS FORMED IN 1987, EMERGING FROM THE BAND LAS INSÓLITAS IMÁGENES DE AURORA. THEIR FIRST LIVE SHOW OCCURRED ON APRIL 11, 1987, AT ROCKOTITLAN. THEY RECENTLY PERFORMED A TRIBUTE TO DAVID BOWIE AT A VENUE IN AZCAPOTZALCO.

Latino, a moment that stirred emotion for the band. “We’ve played the festival several times—we’re not the band that’s performed the most, but we’ve been there for many key moments, with surprise appearances and special guests. It’s a special place. It felt like a high school reunion—it was a great moment to celebrate Latin American music,” André said. Alfonso considers it a privilege for fans to still connect with their music. “We’re not exactly sure why, but I think it’s because we were never trendy. People found our music because they genuinely liked it, not because it was fashionable—and they stuck with us. They wore the jersey and stayed through the highs and lows: when we changed our name when we came back. They’ve passed the torch from generation to generation. The odd uncle would give

the cassette to his nephew, and it kept growing. We see many young people at every show—many who probably weren’t even born when we recorded those albums.”

As for the new single, André explained, “It’s a bit heavy. It’s about a guy from the neighborhood whose best days are behind him. Time catches up with him, age hits hard, and he realizes he’s no longer who he used to be. It’s like a Caifán who becomes aware of time slipping by.”

1988

they released their self-titled debut album, featuring the hit “Mátenme porque me muero.” 1990 El Diablito came out, featuring hits like “La célula que explota” and “Antes de que nos olviden.” 1992 they released El Silencio, with songs like “Debajo de tu piel” and “No dejes que.”

Their final album came in 1994 featuring “Afuera” and “Aquí no es así.”