September 2023 Septembre Vol. 63 No. 3 $10/10 $ Publication 40031215 TM MC Published by Publié par SYSTEMS

SUPPORT WELLBEING UNE APPROCHE SYSTÉMIQUE POUR LE BIENÊTRE www.edcan.ca PLUS: Numeracy screeners for early intervention | Apprendre le métier de direction Why staff mental health is a systemic issue How two school divisions prioritized wellness Using Sacred Hoop teachings to foster whole-school wellbeing

quoi le bienêtre?

personnel

ces héros oubliés

THAT

C’est

Le

suppléant,

Contents

5 EDITOR’S NOTE

Is school a good place to work?

6 PROMISING PRACTICES

Minding the Gap in Mathematics

Using a numeracy screener to support early intervention

By Alexandra Youmans, Jo-Anne LeFevre, Heather Douglas, and Tracie Anthony

DEANS’ PERSPECTIVES

on behalf of the Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE)

9 Renewing the Accord on Indigenous Education

By Jan Hare and

Jennifer

Tupper

11 Education’s Climate Crisis

By Kathryn Hibbert

14 Systemic Approaches to Workplace Wellbeing

Concepts and approaches for Canadian provinces and school districts

By Charlie Naylor

18 Exploring the Sacred Hoop

An Indigenous perspective on educator wellbeing and workplace wellness

By Jennifer E. Lawson and Richelle North Star Scott

22 A Focus on Staff Wellbeing

How Black Gold School Division is turning suggestions into actions to impact employee wellness

By Pam Verhoeff

26 Fostering a Culture of Wellness

Medicine Hat Public School Division’s journey to creating a healthy, inclusive environment for staff, students, and families

By Sarah Scahill

30 Educators and Workplace Mental Health

Findings from Mental Health Research Canada

By Akela Peoples

WEB EXCLUSIVES

www.edcan.ca/magazine

Trauma-Informed Practice

Why educator wellbeing matters

By David Tranter, Nadine Trépanier-Bisson, and Katina Pollock on behalf of the Ontario Principals’ Council

Table des matières

5 LE MOT DE LA RÉDACTION

Bien dans un système, ça se peut?

34 Bonheur, qualité de vie ou bienêtre à l’école ? Y voir clair pour mieux intervenir Par Caterina Mamprin

38 Le vécu et le bienêtre au travail des personnes enseignantes suppléantes Des situations et des besoins à étudier Par Philippe Jacquin, Caterina Mamprin et Jean Labelle

41 Un dispositif d’insertion professionnelle pour favoriser le bienêtre des directions d’établissement au Centre de services scolaire des Draveurs

Par Manon Dufour, Marie-Hélène Guay et Dominique Robert

44 LE MONSTRE JAUNE

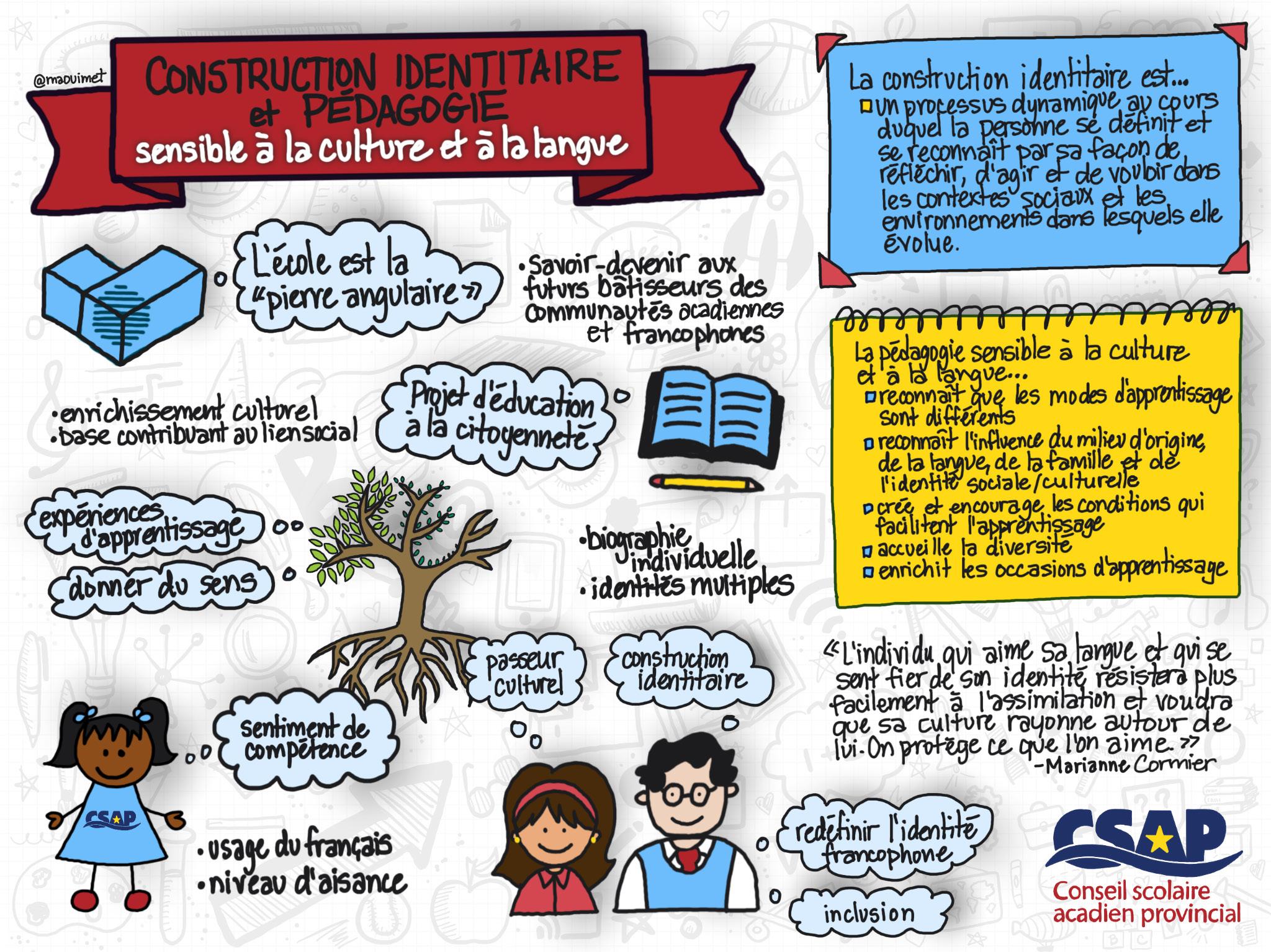

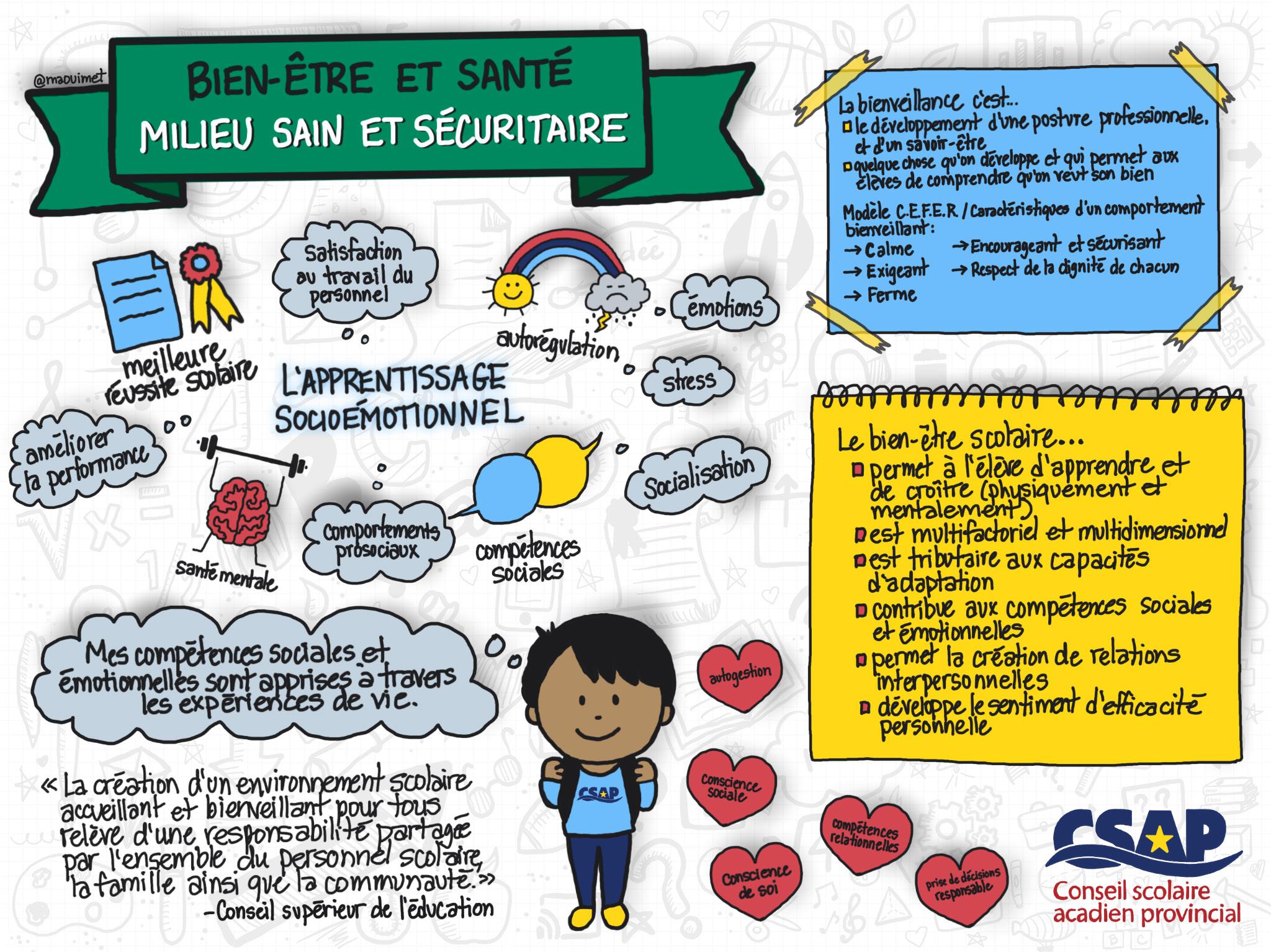

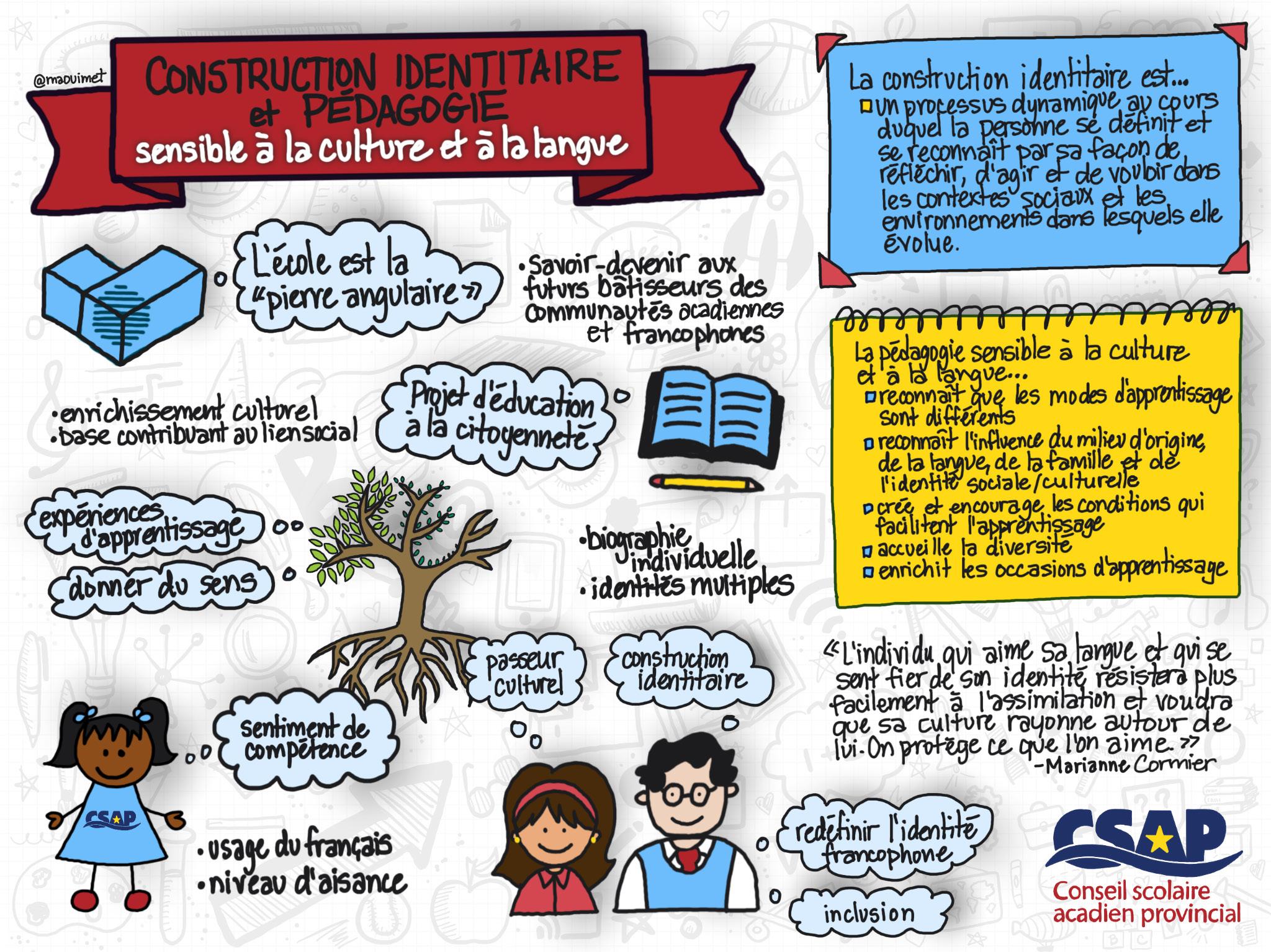

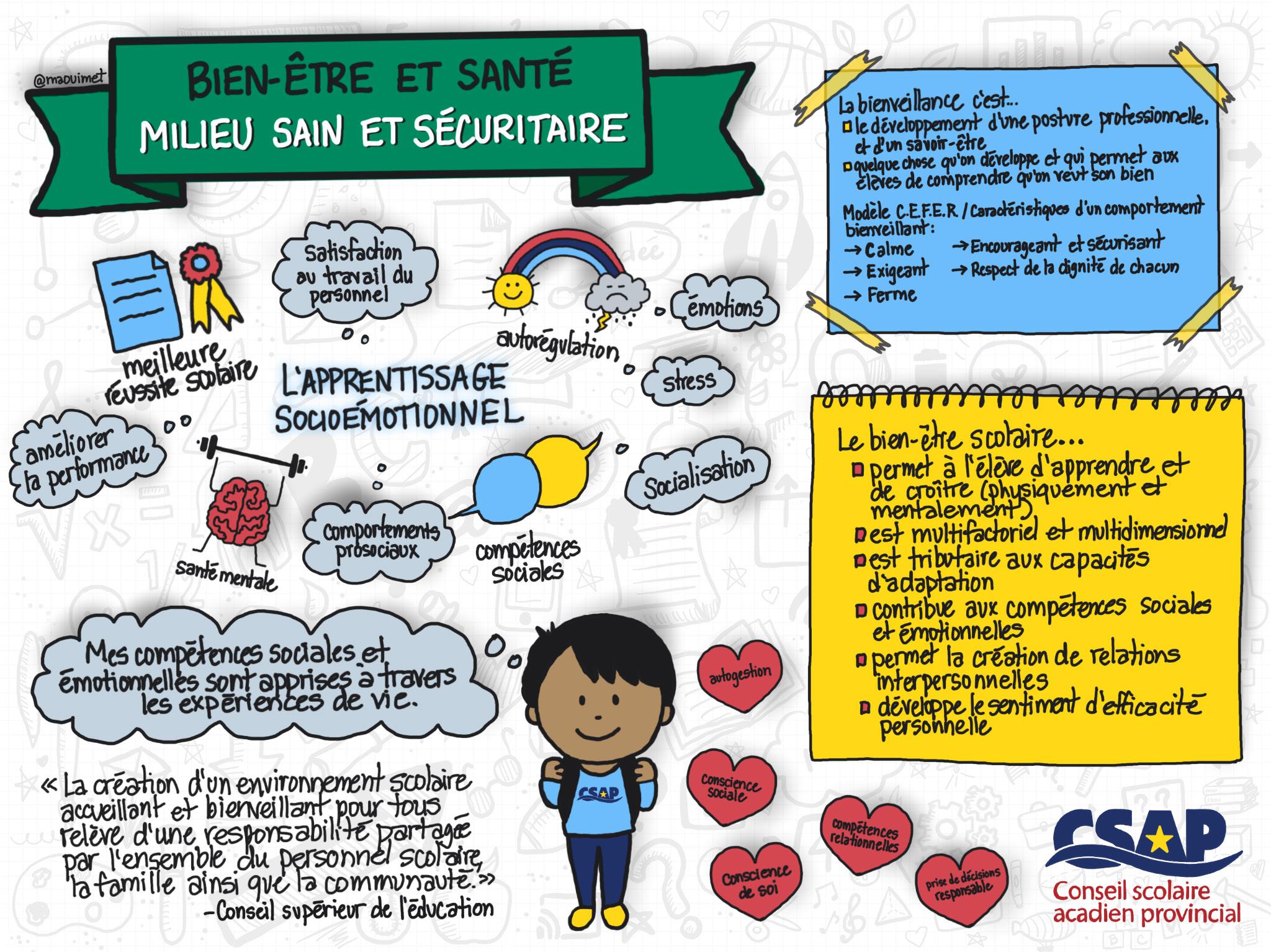

Par Ronald Boudreau

46 Que font les leaders contemporains pour favoriser le bienêtre au sein d’une organisation apprenante?

Par Brigitte Gagnon et Marie-Hélène Guay

50 Concrétiser l’école du bienêtre en réfléchissant autrement

Par Chantale Cyr

52 Santé et bienêtre du personnel

Le processus stratégique du Conseil scolaire acadien provincial de la N.-É.

Par François Rouleau

COVER PHOTO: iStock

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September/septembre 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 3 September/septembre 2023 n Vol. 63 No. 3 n www.edcan.ca

14 38

ILLUSTRATION: ISTOCK

PHOTO : ISTOCK

Executive Editor | Rédacteur en chef Max Cooke

English Editor | Rédactrice anglophone Holly Bennett

Francophone Editor | Rédactrice francophone Gilberte Godin

Art Director | Directeur artistique Dave Donald

Director of Operations | Directrice des opérations Mia San José

Program Director of Well at Work | Directrice de programme de Bien dans mon travail Kathleen Lane

Marketing Manager | Responsable de marketing Shanice Tadeo

Clent andMember Specialist | Responsable des Clients et Membres Miruna Chitoi

Advertising Sales | Ventes de publicité

Dovetail Communications Inc. (905) 707-3526 or/ou advertise@edcan.ca / publicite@edcan.ca

Publisher | Éditeur Canadian Education Association / Association canadienne d’éducation

Chair | Présidente Claire Guy

Marius Bourgeoys, cofondateur d’escouadeÉDU, conférencier, coach et consultant, L’Orignal, ON

Dr. Curtis Brown, Superintendent, South Slave Divisional Education Council, Fort Smith, NT

Dr. Alec Couros, Director, Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Regina, Regina, SK

Nathalie Couzon, technopédagogue, Collège Letendre, Laval, QC

Grant Frost, Public school teacher and educational commentator, Halifax, NS

Roberto Gauvin, Consultant en éducation chez Édunovis, Édunovis, Lac-Baker, NB

François Guité, consultant au ministère de l’Éducation, de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche (MEESR) du Québec, Québec, QC

Dr. Michelle Hogue, Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the First Nations Transition Program, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB

© 2023 Canadian Education Association/l’Association

canadienne d’éducation

ISSN 0013-1253

Publications Mail Agreement No. 40031215

HST/TVH # R100763416

www.edcan.ca

Rooted in the Canadian education experience and perspective, our English and French articles provide voice to teachers, principals, superintendents and researchers – a growing network of experts who examine today’s school and classroom challenges with courage and honesty. Pragmatic, accessible and evidencebased, Education Canada connects policy and research to classroom practice.

Education Canada is published three times yearly by the EdCan Network.

703-60 St. Clair Avenue East Toronto, ON M4T 1N5

Tel: (416) 591-6300; Fax: (416) 591-5345

publications@edcan.ca

www.edcan.ca

Member of Magazines Canada

The EdCan Network no longer sells subscriptions to Education Canada. This publication is available to EdCan Network members only.

Address all editorial correspondence to:

Holly Bennett, Editor

Education Canada

editor@edcan.ca

Tel: (705) 745-1419; Fax: (416) 591-5345

You are free to reproduce, distribute and transmit the articles in this publication, provided you attribute the author(s), Education Canada Vol. 63 (3), 2023, and a link to the EdCan Network (www.edcan.ca). You may not use the articles in this publication for commercial purposes. You may not alter, transform, or build upon the articles in this publication.

Publication ISSN 0013-1253.

The views expressed or implied in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EdCan Network. Publication of an advertisement in Education Canada does not constitute an endorsement by the EdCan Network of any advertiser’s product or service including professional learning opportunities.

Normand Lessard, Secrétaire général, Association des directions générales scolaires du Québec, Sherbrooke, QC

Corinne Payne, Directrice Générale, Fédération des comités de parents du Québec (FCPQ), Québec, QC

David Price, Senior Associate, Innovation Unit, Leeds, UK

Zoe Branigan Pipe, Teacher, Hamilton, ON

Cynthia Richards, Canadian Home and School Federation, Chipman, NB

Sébastien Stasse, directeur formation et recherche au CADRE21, Longueuil, QC

Dr. Joel Westheimer, University Research Chair in the Sociology of Education, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON

Andrew Woodall, Dean of Students, Concordia University, Montréal, QC

Dr. Christine Younghusband, Assistant Professor, University of Northern British Columbia School of Education, Prince George, BC

Ancrés dans l’expérience et la perspective de l’éducation au Canada, nos articles, en anglais et en français, donnent voix aux enseignants, aux directeurs d’écoles, aux administrateurs et aux chercheurs, c’est-à-dire à un réseau croissant d’experts qui se penchent avec courage et honnêteté sur les enjeux actuels de l’école et de la pratique en classe. Pragmatique et accessible, fondé sur des données probantes, le magazine Éducation Canada jette des ponts entre politiques, recherche et pratique.

Le magazine Éducation Canada est publié trois fois l’an par le Réseau ÉdCan. 60, avenue St. Clair E, bureau 703 Toronto, ON M4T 1N5

Tél. : 416 591-6300; Téléc. : 416 591-5345

Courriel : publications@edcan.ca

www.edcan.ca/fr

Membre de Magazines Canada

Le Réseau ÉdCan ne vend pas d’abonnements au magazine Éducation Canada. Cette publication est réservée aux membres du Réseau ÉdCan.

Envoyez vos lettres et manuscrits à : Gilberte Godin

Rédactrice francophone Éducation Canada

redaction@edcan.ca

Tél. : 416 591-6300 Téléc. : 416 591-5345

Il est permis de reproduire, de distribuer et de transmettre les articles de ce magazine, à condition d’en indiquer l’auteur (ou les auteurs) ainsi que Éducation Canada, Vol. 63 (3), 2023, et d’inclure un lien vers le Réseau ÉdCan (www.edcan.ca/fr). Il est interdit d’utiliser les articles de cet ouvrage à des fins commerciales ou encore d’altérer, de transformer ou d’étoffer les articles de ce magazine.

Publication ISSN 0013-1253.

Les opinions exprimées de façons implicite et explicite dans ce magazine sont celles des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement le point de vue du Réseau ÉdCan. La parution d’annonces dans les pages du magazine n’implique aucunement que le Réseau ÉdCan appuie les produits ou services annoncés, y compris les activités de formation professionelle.

Note : Le magazine Éducation Canada adhère à la nouvelle orthographe. Le générique masculin est utilisé sans discrimination et uniquement dans le but d’alléger le texte.

4 EDUCATION CANADA • September/septembre 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Education Canada Editorial Board / Comité éditorial d’Éducation Canada

BY HOLLY BENNETT PAR GILBERTE GODIN

Is school a good place to work?

THE WORK OF education professionals grows more complex and taxing by the year, and over the past three years especially, we have seen school staff at every level step up and adapt to extraordinary challenges. Our goal has been for Education Canada magazine to help our readers think critically about key education issues and meet some of those challenges feeling more informed, better equipped, and even inspired.

But we know that many educators are struggling. As with so many things, COVID exacerbated a problem that already existed: educators are burning out, and mental health problems are on the rise among both staff and students. In response, the EdCan Network has increasingly focused its attention on staff wellbeing, both in the magazine and through its Well at Work program.

In her article “Educators and Workplace Mental Health,” Akela Peoples of Mental Health Research Canada reports that at the height of the pandemic, 38 percent of teachers said they were suffering from burnout. That number has not changed much since. And when over a quarter of your staff have that much job stress, there’s a problem with the job itself. As Charlie Naylor, a Strategic Consultant with EdCan’s Well at Work Advisors program, writes on p. 14, “Teachers, principals, or school bus drivers should bear some responsibility for their own wellbeing, and for positively contributing to their professional workplace, but should not bear responsibility for fixing school systems that may be making them sick.”

That’s why, in this issue, we are looking at systemic approaches to staff and school wellness. We’ve learned some of the key roles and actions, from the provincial level right down to the individual, that are important in creating healthy workplaces. System change doesn’t happen overnight. It’s about capacity building from within, and it takes a commitment from everyone in the system to change the system.

But it’s by no means impossible – just look at the work that’s been done in the two school districts profiled on pages 22 (Black Gold SD) and 26 (Medicine Hat PSD). And they have only just begun. Together, we can learn how to make our schools supportive, healthy places to learn and work – for everyone. EC

Write to us!

We want to know what you think. Send your comments to editor@edcan.ca – or join the conversation by using #EdCan on Twitter and Facebook.

Bien dans un système, ça se peut?

ON DIT DES SYSTÈMES que ce sont des ensembles de pratiques organisées en fonction d’un but. Quiconque est « passé » par un système – et c’est à peu près tout le monde - sait que celui-ci vise habituellement l’uniformité, l’ordre, l’élimination des exceptions et surtout des injustices. Comme bien des professionnels, j’apprécie que les choses soient justes et tournent rondement au travail, mais moi, lorsque je sens que je suis « prise » dans un système, que les élèves ou les personnes passent après le système, et bien… je souffre un peu. Voilà!

Imaginons que ce fameux système soit pensé autrement, non pas pour viser la conformité, mais plutôt l’efficacité de chacun et leur épanouissement. Imaginons que le système joue le rôle de filet de sécurité et qu’on puisse s’y fier lorsque notre motivation nous pousse à foncer vers l’inconnu, lorsqu’on se trompe, lorsqu’on on a besoin d’avis d’experts, d’appui moral ou de bras pour réaliser un projet. Imaginons que ce système est notre meilleur ami.

Le numéro de la rentrée 2023 explore justement cette question. Avant même d’envisager tout changement systémique, Caterina Memprin, p. 34, nous guide à travers les méandres du concept même du bienêtre. Qu’entend-on par ce terme? Pour Ronald Boudreau, p. 44, un système qui bâtit des liens engageants avec la communauté pour soutenir le cheminement à long terme des élèves francophones est un système qui nourrit véritablement le bienêtre de ces élèves et du personnel. Dufour, Guay et Robert, p. 41, insistent sur l’importance d’une insertion professionnelle réfléchie pour les directions d’école et décrivent le travail d’un Centre de services qui prend les grands moyens pour y arriver. Parmi d’autres articles inspirants, se trouvent celui de Jacquin, Membrin et Labelle, p. 38, qui rendent compte de leur étude sur la situation des suppléants qui passent de plus en plus de temps auprès des élèves. Comment le système peut-il tenir compte des défis et du bienêtre de ces alliés indispensables?

Les auteurs et autrices de ce numéro d’Éducation Canada permettent d’entrevoir un système réfléchi et aménagé de telle sorte qu’il pourrait très bien devenir notre meilleur ami. ÉC

Écrivez-nous!

Envoyez vos commentaires à redaction@edcan.ca

Joignez-vous à la conversation en utilisant le #EdCan sur Twitter et Facebook.

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September/septembre 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 5

editor’s note / le mot de la rédaction

promising practices

BY ALEXANDRA YOUMANS, JO-ANNE LEFEVRE, HEATHER DOUGLAS, AND TRACIE ANTHONY

Alexandra (Sandy) Youmans, PhD, OCT, is a Continuing Adjunct Professor of Elementary Mathematics at the Faculty of Education, Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. She is a former Kindergarten teacher and a co-investigator of the Assessment and Instruction for Mathematics (AIM) Collective.

Jo-Anne LeFevre, PhD, is a Chancellor’s Professor of Cognitive Science and Psychology and Chair of the Department of Cognitive Sciences at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ont. She is the Director of the Mathematics Cognition Lab and the Principal Investigator of the Assessment and Instruction for Mathematics (AIM) Collective.

Heather Douglas, PhD, is an Adjunct Research Professor of Cognitive Science at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ont. She is a former elementary teacher and a co-investigator of the Assessment and Instruction for Mathematics (AIM) Collective.

Tracie Anthony, MEd, is the Numeracy Coordinator for the Grande Prairie Public School Division in Grande Prairie, Alta. She is a teacher and a school division partner of the Assessment and Instruction for Mathematics (AIM) Collective.

Minding the Gap in Mathematics

Using a numeracy screener to support early intervention

IF YOU ARE A PARENT, you likely recall your baby’s wellness visits with the family doctor. During these frequent visits, the focus was on monitoring physical growth and development to identify any issues that might require attention. By plotting children’s individual growth curves and comparing them with standardized charts, physicians can determine whether satisfactory growth is occurring and when intervention is needed.

Just as health practitioners monitor physical growth with charts, educators can monitor learning growth with universal screeners. A universal screener is a short assessment administered to all students in a classroom that tests sub-skills predictive of a more complex skill. In the case of literacy screeners, the sub-skills of phonological awareness and alphabet knowledge are assessed because they are essential for decoding (Biel et al., 2020). Similarly, numeracy screeners include counting, number relations, and basic arithmetic items because they are components of early numeracy (Devlin et al., 2022).

To discover any learning gaps and ascertain progress, universal screeners are often conducted three times over the course of a school year. Initial screener use provides educators with a baseline of students’ abilities that can

be used to guide instruction and flag students who may require additional support. A key tracking feature of universal screeners is that target scores are connected with a child’s grade or age. Students who meet target scores are progressing as anticipated, whereas students who are close to or below target scores may be struggling with foundational skills. For students who do not meet target scores, instructional support or intervention is recommended. Tracking students’ progress over time allows teachers, schools, or districts to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, ultimately determining whether learning gaps have been reduced or closed.

As an educator or school administrator, you are probably aware of the importance of literacy screeners for identifying and supporting children who may be at risk for reading difficulties. You may also be familiar with specific literacy screeners and interventions used in classrooms. Unfortunately, information about numeracy development is not as readily available as it is for literacy, since the field of mathematics cognition research is still fairly new. However, strides in understanding mathematics development and growing interest in supporting early mathematics learning have led to the creation of evidence-based universal numeracy screeners. This article features one such numeracy screener, the Early Math Assessment at School (EMA@School), which is licensed by Alberta Education as the Provincial Numeracy Screening Assessment (PNSA). PNSA data was used by the Grande Prairie Public School Division in Alberta to target students for intervention and assess whether the interventions worked as intended to remediate identified students.

6 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

PHOTO: ISTOCK

The creation of a numeracy screener

Math learning is cumulative (increasingly complex skills build on one another), so it is important to lay a strong foundation in early mathematics (Sarama & Clements, 2009). Moreover, when young children begin school, they vary widely in their mathematical understanding and skills, meaning an achievement gap already exists in Kindergarten (Duncan et al., 2007; Jordan et al., 2009). If this math achievement gap is not addressed early, children with less mathematical proficiency will continue to fall behind their peers. Numeracy screeners are a practical tool for identifying students who require extra instruction and intervention to grasp foundational skills.

Data from Alberta suggests that early achievement gaps may have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Child and Youth Well-Being Panel, 2021). In response, Alberta Education has implemented literacy and numeracy screeners for children in Grades 1–3 to help students get back on track. While there is an abundance of evidence-based literacy screeners available for classroom use, comparable numeracy screeners are lacking. For this reason, Alberta Education contacted the Mathematical Cognition Lab (MCL) at Carleton University in the spring of 2021 to discuss the creation of a provincial numeracy screener. Based on their expertise in mathematical development, the MCL constructed a grade-specific numeracy screener for students in each of the primary grades. The screener consists of items assessing number knowledge, number relations, and number operations, because these related subdomains tap into early mathematical knowledge, but they all predict mathematics learning separately (Devlin et al., 2022). Although many tasks are common across grades (with questions reflecting gradespecific knowledge), there are some differences between grades. For

students in the younger grades, the screener has a stronger emphasis on number knowledge and number relations (e.g. counting, number naming, comparing numbers), while there is more of a focus on number operations (e.g. arithmetic fluency, principles of addition) for older grades.

Using the numeracy screener to support early intervention

During the 2021/2022 school year, classroom teachers administered the Provincial Numeracy Screening Assessment (PNSA) to over 50,000 primary students. The Grade 1 PNSA involved both one-on-one testing (5 minutes per student) and whole-class testing (15 minutes). For Grades 2–3, the PNSA was implemented in a whole-class setting during a 20- to 30-minute session. Target scores for the PNSA were established, so the tool could be used to identify students who were at risk for low achievement in mathematics. Alberta Education developed intervention lessons that accompanied the PNSA that included: activities for each numeracy sub-skill encompassing concreteto-representational-to-abstract instructional processes, explicit mathematical vocabulary, and mathematical symbols. The Alberta government provided funding to school divisions to both administer the PNSA and provide needed interventions for students.

In September 2022, the Grande Prairie Public School Division (GPPSD) in Alberta administered the PNSA to students in Grades 2 to 3. Grade 1 students completed the PNSA in January 2023 to allow for some initial mathematics instruction and acclimatization to school prior to screening. To meet the needs of students in the division, the Numeracy Coordinator designed a comprehensive early numeracy intervention approach, consisting of the following elements:

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 7

Figure 1. A math mat used to capture student learning during early numeracy intervention.

• Two lead teachers to oversee the intervention program, and 20 education assistants (EAs) to deliver the program in 15 elementary schools

• Intervention designed by the Numeracy Coordinator consisting of scripted and structured mini-lessons based on sub-skills identified in the PNSA for delivery by EAs

• A pull-out small group (two to four students) delivery model used daily for between 20-30 minutes for six-week cycles

• Student work captured daily on a math mat during intervention (see Figure 1), with progress being evaluated using an assessment mat (similar to a math mat) and tracked in an Excel spreadsheet for individual students

• Multiple check-in points to oversee student growth (e.g. move on to higher numbers, focus on a new sub-skill, assess whether students are ready for discharge)

Resources

For more information about numeracy screeners and early numeracy intervention, check out these resources:

n Assessment and Instruction for Mathematics (AIM) Collective website: www.aimcollective.ca

n Fuchs, L.S., Newman-Gonchar, et al. (2021). Assisting students struggling with mathematics: Intervention in the elementary grades (WWC 2021006). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. http://whatworks.ed.gov/

n Youmans, A., & Colgan, L. (Eds.). (in press). Beyond 1, 2, 3: Strengthening early math education in Canada Canadian Scholars Press.

Once students demonstrate strong understanding in most subskills, they are discharged from the intervention program. Students who exhibit little to no growth have lessons adapted to meet their needs. In the case where growth is limited even after lesson adaptations, intervention work is used as evidence that students may require formal psychoeducational assessments for learning disabilities.

Overall, the intervention is being well received by the school community. One educational assistant commented on the success of the program: “Because we see the students daily, in small groups,

we can target the help they need more individually, giving them the opportunity to ask questions and learn in a small-group setting at their level.” From a classroom perspective, a Grade 2 teacher noted that “the kids come back from intervention with more confidence and willingness to take risks!” To date, intervention tracking data indicates that 431 students (across 15 schools) have received targeted support. Of those students, 330 (77 percent) have advanced to meet target scores in most numeracy sub-skills, earning a discharge from the targeted support. The remaining 101 students, although considered “still at risk” after the six-week cycle, made significant gains, specifically in the sub-skills of number line and computations.

As the GPPSD continues to enhance their early numeracy intervention design, they are focusing on fostering greater collaboration between classroom instruction and the early intervention program to reinforce the learning in both environments. There is no question that numeracy screeners are a powerful tool for helping educators focus on foundational learning needed for future mathematics and life success. EC

REFERENCES

Biel, C., Conner, C., et al. (2022) How does the science of reading inform early literacy screening? Virginia State Literacy Association.

https://literacy.virginia.edu/sites/g/files/jsddwu1006/files/2022-03/How%20Does %20the%20Science%20of%20Reading%20Inform%20Early%20Literacy%20 Screening9888e091cc0c17d238d1c54ce31de7afc4bbc396863e07e1d942a4505c5 a17a0.pdf

Child and Youth Well-Being Panel. (2021). Child and youth well-being review: Final report. Government of Alberta.

https://open.alberta.ca/publications/child-and-youth-well-being-review-finalreport#summary

Devlin, D., Moeller, K., & Sella, F. (2022). The structure of early numeracy: Evidence from multi-factorial models. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 26. https://doi:10.1016/j.tine.2022.100171

Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., et al. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428–1446.

Jordan, N. C., Kaplan, et al. (2009). Early mathematics matters: Kindergarten number competence and later mathematics outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 850–867. https://doi:10.1037/a0014939

Sarama, J., & Clements, D. H. (2009). Early childhood mathematics education research. Taylor & Francis.

8 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

+ –x ÷

Of the students who received targeted support, 77 percent advanced to meet target scores in most numeracy sub-skills.

deans’ perspectives

BY JAN HARE AND JENNIFER TUPPER

On behalf of the Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE)

Jan Hare, PhD, is Dean pro-tem of the Faculty of Education at the University of British Columbia, situated on Musqueam and Syilx territories. Her teaching and research are concerned with centring Indigenous knowledge systems in educational institutions. She holds a Canada Research Chair in Indigenous pedagogy.

Jennifer Tupper, PhD, is Dean of the Faculty of Education at the University of Alberta in Treaty 6. She is an award-winning scholar whose research focuses on treaty education, anti-oppressive approaches to teaching and learning, and critical forms of citizenship.

Renewing the Accord on Indigenous Education

AS A COLONIAL NATION, Canada is founded on the theft of Indigenous lands through settler invasion, which must be understood as a structure rather than an historical event. What this means is that colonialism is not a thing of the past; it continues to shape economic, political, and social structures through its intent to displace and disempower Indigenous peoples. Tuck and Yang (2012) argue that at its core, colonialism and its need to ensure “settler futurity” is about control over the land. Education has been an instrument of colonialism, therefore complicit in the dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands, languages, and livelihoods. As part of the “civilizing” and assimilating agendas of Canadian society, schooling was designed to harm Indigenous people, particularly through the erasure of Indigenous ways of knowing and by disrupting family and community systems. The imperative for Canadians to understand and recognize this foundational context of colonialism has been part of educational directives for some time. This includes the 1996 Canada’s Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, which called for inclusion of Aboriginal perspective, traditions, and worldviews in school curriculum and programs to address stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism as educational priorities for improving educational outcomes for

Indigenous learners and setting directions for Indigenoussettler relations in this country.

In 2010, under the leadership of Indigenous scholars Jo-ann Archibald and Lorna Williams, and Education Deans Cecilia Reynolds and John Lundy, the Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE) launched the Accord on Indigenous Education. This marked the end of a threeyear process of pan-Canadian consultation, engagement, and feedback at a time of limited understanding of the realities of settler colonialism in the consciousness of most Canadians. The Accord aimed to address this through a series of objectives meant to inform and transform both teacher education and K–12 classrooms. The Accord states that “the processes of colonization have either outlawed or suppressed Indigenous knowledge systems, especially language and culture, and have contributed significantly to the low levels of educational attainment and high rates of social issues such as suicide, incarceration, unemployment, and family or community separation” among Indigenous peoples in Canada (p. 2).

The key principles of the Accord include supporting a more socially just society for Indigenous peoples; respectful, collaborative, and consultative processes with Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge holders; promoting partnerships among educational and Indigenous communities; and valuing the diversity of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing and learning. These principles guide the Accord and its overarching vision that “Indigenous identities, cultures, languages, values, ways of knowing, and knowledge systems will flourish in all Canadian learning settings” (p.4). To achieve this vision, the Accord lays out a series of goals, including

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 9

Cover detail from the 2010 ACDE Accord on Indigenous Education, which is now being renewed.

respectful and welcoming learning environments, curriculum inclusive of Indigenous knowledge systems, culturally responsive pedagogies and assessment practices, mechanisms for promoting and valuing Indigeneity in education, affirmation and revitalization of Indigenous languages, Indigenous education leadership, and culturally respectful Indigenous leadership.

Many deans of education have looked to the Accord to advance changes in teacher education, including the creation of mandatory Indigenous education classes in some programs and the intentional weaving of Indigenous knowledges, content, and perspectives into education courses in other BEd programs. The Accord has been used to advocate for revisions to provincial curricula across the country, especially when the curriculum was silent or only superficially inclusive of the historical and contemporary voices and experiences of Indigenous peoples. The influence of the Accord can also be traced to the creation of First Nations education frameworks in several provinces, the creation of teacher competencies or professional

the heightened inequities within Indigenous communities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Styres & Kempf, 2022).

Further orienting Faculties of Education to Indigenous education priorities has been the emergence of the Idle No More movement, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Girls and Women (MMIGW), and the Federal Government of Canada’s commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). For example, in B.C., UNDRIP became legislation through the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act and an Action Plan that specifies Indigenous peoples’ rights to self-determination as a core element of Indigenous-settler relations, including Indigenous people’s right to education in their languages and cultures. Given these emerging policy directives and social and political movements, the time was right to renew the Accord on Indigenous Education. This was precisely the request made to ACDE by the executive members of the Canadian Association for Studies in Indigenous Education in 2019.

standards, efforts by school divisions to improve the experiences of Indigenous learners in classrooms and school communities, and the implementation of policies at local and provincial levels that aim to improve the experiences of Indigenous learners. In Alberta, the Teacher Quality Standards outline a requirement for teachers to have foundational knowledge of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, and in British Columbia, the First People’s Principles of Learning build on the aims of the Accord by centring Indigenous knowledge in education. In addition to policies, principles, and standards for education, the Accord has been cited numerous times by academics whose work challenges settler colonialism, influencing the growing body of research and scholarship in Indigenous and anti-colonial education.

In the years since the Accord was launched, many more efforts to recognize the truth of Canada’s history and improve Indigenoussettler relations have unfolded. One of the most significant is the work of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the resulting 94 Calls to Actions. Reconciliation as a framework for education has inspired Faculties of Education to create reconciliation advisories, hire Indigenous faculty, develop strategic plans, revise and enhance Indigenous offerings in curriculum, and provide professional development for staff and faculty to deepen their understanding of colonialism and Indigenous perspectives and knowledges. As it takes hold in educational spaces, we can all appreciate the way reconciliation facilitates decolonization, equity, and more recently, Indigenization. However, reconciliation has also been subject to critique, especially in light of the growing anti-Indigenous racism, illegal incursion on Indigenous lands, denial of Indigenous rights, and

The process of renewal that is underway draws inspiration from Cree Elder and scholar-educator Dr. Verna Kirkness’s (2013) leadership approach that asks us to consider the following questions: Where have we been, where are going, how do we get there, and how do we know when we are there? Pan-consultation and feedback sessions are being held by deans of education from across Canada over the coming year, who will “listen and lift” the voices and perspectives from early learning, K–12, teacher education, and communities. The process of consultation and the work of the deans emphasize responsibilities and actions that help learners understand their entanglements in settlercolonialism, draw from the diverse and rich Indigenous knowledge traditions in their lives, and advance Indigenous rights and priorities through anti-racist, decolonial, and sovereign approaches. A revised Accord on Indigenous Education will seek to align its goals with the rights acknowledged in UNDRIP, the TRC Calls to Action, and the MMIGW Calls for Justice. Given all that has unfolded since the Accord was first launched, there is an imperative to move from a language rooted in the politics of respect to the politics of rights, creating new opportunities for educators to deepen and expand their understanding and their practice in ways that actively confront the colonial relations of Canada, moving us into an Indigenous-settler future in ethically relational ways (Donald, 2009). EC

REFERENCES

Association of Canadian Deans of Education. (2010). Accord on Indigenous education

https://csse-scee.ca/acde/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2017/08/Accord-onIndigenous-Education.pdf

Donald, D. (2009). Forts, curriculum, and Indigenous métissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts. First Nations Perspectives, 2(1), 1–24.

Kirkness, V. (2013). Creating space: My life and work in Indigenous education University of Manitoba Press.

Styres, S. D, & Kempf, A. (2022). Troubling Truth and Reconciliation in Canadian education: Critical perspectives. University of Alberta Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education& Society, 1(1), 1–40.

UN General Assembly, United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, 2 October 2007, A/ RES/61/295. https://www.refworld.org/docid/471355a82.html

10 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Given all that has unfolded since the Accord was first launched, there is an imperative to move from a language rooted in the politics of respect to the politics of rights.

deans’ perspectives

BY KATHRYN HIBBERT

Education’s Climate Crisis

Are we failing our children’s schools?

WE ARE LIVING IN A TIME of uncertainty, stress, and exhaustion. Our world is facing literal and metaphorical fires, encompassing environmental crises, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the spread of political and religious extremism, escalating violence and war, fragile economies and rising inflation, famine, poverty, and food insecurity.

Education is in the midst of its own profound “crisis of climate.” Teaching and learning cannot flourish in an alienating and inhospitable landscape. Canada and other world partners have set an ambitious goal to achieve netzero emissions by 2050 to tackle the global environmental climate crisis. What ambitious goals are addressing the climate crisis in education for Education 2050 and beyond? Arguing that the “current disruption has changed education forever,” the Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE) met to signal “educational priorities… and where investment is needed in teacher education, teachers and research as a recovery strategy” (2020, p. 3).

A climate recovery strategy for education ecosystems 2050

Schools are ecosystems where children bring their own histories, knowledge, and experiences. These ecosystems have distinct cultures, structures, and access to resources. The wellbeing of children depends upon

having consistent “attuned, non-stressed and emotionally reliable caregivers” (Maté & Maté, 2000, p. 101). However, in the present context, many children, families, and teachers are struggling.

Beista, Priestley et al., (2015) have been studying educational ecosystems for many years. Their interest stems from the fact that as global policies have been adopted, teachers have been positioned as agents of change. However, rather than seeing agency simply as the individual capacity that teachers may or may not possess, they understand meaningful agency as a part of the ecology of the school systems within which teachers practise. Embedding agency within an existing ecosystem clarifies that we are all complicit in the conditions we create for teaching and learning to thrive – or to wither.

An educational ecosystem is far more than a collection of physical spaces, policies, and curriculum documents. To empower teachers and bring about positive change, a clear vision is necessary. This involves meaningful engagement with parents, community members, school psychologists, healthcare providers, educational assistants, teacher education students, and teacher education providers. Recognizing the critical role each of these stakeholders plays is necessary for the wellbeing of students’ physical, social-emotional, intellectual, and mental health.

The “critical habitat” for teaching and learning

A critical habitat is essential for children to thrive. Recognizing the lasting impact of the current disruption on education, a thriving environment ensures safety, support, and equitable access to resources like technology and the internet. It upholds the rights of the children (UN General Assembly, 1989) and honours the

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 11

Kathryn Hibbert, PhD, is a Distinguished University Professor, Associate Dean of Teacher Education, and former Acting Dean of the Faculty of Education at Western University.

On behalf of the Association of Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE)

PHOTO: ISTOCK

provisions for francophone and minority language education (Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, 1982). It responds to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action. Educators play a vital role in the recovery, but without strategic and sustainable investment, they face additional risks.

Threats to the educational ecosystem

Globalization has led to an emphasis on competition, excellence, and individualism in education. Despite well-documented disparities, the focus on “recovery” is trained narrowly on “learning gaps” and concern about “falling behind.” Ignoring the critical habitat effectively undermines efforts to close those gaps or achieve higher test scores. The needs of historically marginalized students and families have too often been debated, thwarted, or ignored.

Treating the educational system as a “market” undermines educational ecosystems, prioritizing shareholders over stakeholders. Government involvement in seeking market solutions to public policy problems diverts financial resources to for-profit businesses from schools. An emphasis on testing, for example, driven by the financial interests of publishing companies, devalues educators’ ongoing assessments. The shift redirects efforts toward test scores and global reputation over holistic growth.

When changes in education are subject to short-term, politically driven reactions, the gaze is fixed on the desires of electors with special interests, over the concrete needs of children and educators. Policies emerging from such a limited view can destabilize progress and can entrench traumatizing social conditions, leaving teachers without the agency, autonomy, purpose, and sense of meaning that leads to wellness and motivation. As key resources in the ecosystem, educators and teacher education providers must play a vital role in policy and curriculum planning and decisions.

Many parts of the world, with Canada now among them, have been crippled by a teacher shortage. When the environment in schools is neglected, and calls for support, resources, and safety measures are ignored (or promised but never realized), it can lead to despondence, positioning educators as disseminators of decisions made elsewhere (Hibbert & Iannacci, 2005). When teachers feel ignored, underresourced, or undervalued, they leave the profession (Bryant et al., 2023).

For example, educators are the front-line witnesses to systemic racism and equity. The crisis of climate in education has revealed new depths of inequity. Interpersonal and structural violence became more evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Building safe and trusting relationships is critical as we re-orient students to being in community, developing social-emotional capacity and recovering from their experiences over the past few years. The mental health needs of both teachers and students must be supported.

How do we restore damaged systems?

To build a safe and more sustainable educational ecosystem, we must prioritize the physical spaces, culture, and climate of schools. Schools ought to model advanced standards in air and water quality, as these factors impact students’ health, concentration, and comfort in learning. Implementing energy-efficient and accessible technologies should be a basic requirement to demonstrate care for students and responsible use of resources. All curricula should incorporate cultural safety and human rights principles. By learning in schools that exemplify these shared goals, students can better connect what they learn with what they observe in a safe and sustainable world.

Cree scholar Dwayne Donald argues that “ethical relationality is an ecological understanding of human relationality that does not deny difference, but rather seeks to more deeply understand how our different histories and experiences position us in relation to each other” (2009, p. 6). Bringing a compassionate curiosity that positions us all as part of an interconnected whole – where one cannot thrive without the other – holds promise for developing the trauma consciousness that is so desperately needed to move beyond the damage sustained from years of neglect. The core vision and commitments cannot be subject to change with each new government. Rather, they must address a “security of place” (Neef et al., 2018) that prioritizes a healthier, sustainable and long-term vision and investment in our Canadian educational future – and the futures of all children who participate in these systems.

Refugees, migrants, and immigrants are choosing Canada as a safe place to educate their children. One need only read the news to see that that “safety” can be disingenuous for some populations. We know that “students’ relationships with their teachers are vital to their academic learning and psychosocial development” (Smith & Whitely, 2023, p. 96). Those relationships are made more fragile when the teacher’s own needs are not being met.

“How do we help children achieve and develop to the limits of their potential, particularly those who struggle most in an industrialized system of education that struggles to accommodate individual needs and challenges?” (p. 101). This process begins by establishing a caring relationship between educators and students. However, it is crucial for educators to operate within a caring environment and a system that genuinely values the education and wellbeing of children beyond their future economic contributions. Achieving this requires intellectual humility, collaboration, and investment as education is prioritized and valued for the significant role it plays in all our social futures. EC

REFERENCES

Association of Canadian Deans of Education. (2020). Teaching and teacher education: Preparing for a flourishing post-pandemic Canada. ACDE.

Biesta, Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: an ecological approach. Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474219426

Bryant, J., Ram, S., et al. (2023). K-12 teachers are quitting. What would make them stay? McKinsey & Company.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/k-12-teachers-arequitting-what-would-make-them-stay

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-12.html

Donald, D. (2009). Forts, curriculum, and Indigenous Métissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts. First Nations Perspectives, 2(1), 1–24.

Government of Canada, (n.d.). Net-zero emissions by 2050

https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/ climate-plan/net-zero-emissions-2050.html

Hibbert, K., & Iannacci, L. (2005). From Dissemination to discernment: The commodification of literacy instruction and the fostering of “good teacher consumerism.” The Reading Teacher, 58(8), 716–727. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.58.8.2

Maté, G., & Maté, D. (2022). The myth of normal: trauma, illness and healing in a toxic culture. Alfred A. Knopf Canada.

Neef, A., Benge., L., et al. (2018). Climate adaptation strategies in Fiji: the role of social norms and cultural values. World Development, 107, 125-137.

Smith, J. D. & Whitley, J. (2023). Teaching with acceptance and commitment: Building teachers’ social-emotional competencies for teaching effectiveness. The Educational Forum, 87(1), 90–104. https://doi: 10.1080/00131725.2022.2053620

UN General Assembly. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Treaty Series, 1577, 3. United Nations. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000101215

12 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Systemic Approaches to Workplace Wellbeing

Concepts and approaches for Canadian provinces and school districts

BY CHARLIE NAYLOR

DR. GABOR MATÉ (2022) argues that within the medical world, treating individual health symptoms, without considering wider systems within which individuals exist, ignores multiple factors that contribute to sickness:

“What if we saw illness as an imbalance in the entire organization, not just as a manifestation of molecules, cells or organs invaded or denatured by pathology?

What if we applied the findings of western research and medical science in a systems framework, seeking all the connections that contribute to illness and health?”

Historically, addressing individual symptoms has been the dominant approach in western medicine. The same focus on individuals rather than systems has also pervaded approaches to workplace wellbeing in Canadian schools. A plethora of incentives, from gym membership to yoga classes, suggests that K–12 staff wellbeing can be addressed by encouraging individuals to access such programs to counter stresses in work and life.

This article rejects a dominant focus on individual remedies and argues for systemic approaches to address workplace wellbeing. While individual responsibility has its place, a primary focus on it is misplaced. Teachers, principals, or school bus drivers should bear some responsibility for their own wellbeing, and for positively

contributing to their professional workplace, but should not bear responsibility for fixing school systems that may be making them sick.

So how to create systemic approaches to wellbeing?

1. Provincial governments can play a greater role.

To its credit, the British Columbia government, through its Ministry of Education’s Mental Health in Schools Strategy (2020) has encouraged a focus on workplace wellbeing:

“Research confirms stress experienced by school administrators can negatively impact school staff.

Teacher stress has been directly linked to increased student stress levels, spilling over from the teacher to the student and impacting social adjustment and student performance.”

Funds from the Ministry of Education to address mental health can be utilized for a focus on adults in K-12 school systems.

Addressing two issues would greatly improve the role of provincial governments (including B.C.) in supporting systemic workplace wellbeing:

• Collating and analyzing sick leave and short/longterm disability costs linked to mental health

14 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Charlie Naylor is the Lead Advisor and B.C. Strategic Consultant in the EdCan Well at Work Advisors’ Team. He was formerly a Senior Researcher with the B.C. Teachers’ Federation and is an Affiliated Scholar with Simon Fraser University.

SYSTEMS THAT SUPPORT WELLBEING

Currently in B.C., data for teacher and support staff sick leave usage is held by districts, and short/long term disability data are held by teacher and support staff unions, while principals maintain their own usage data. In Alberta, the Alberta School Employee Benefit Plan provides long-term disability support while employers provide short-term disability and sick leave. Similar divisions exist in other provinces. Provincial governments could develop capacity to ascertain sick leave and disability prevalence, trends, and differences (in terms of age, gender, and roles), data that could provide a basis for more systemic action.

• Addressing the low pay and limited hours of some support staff, with a primary focus on educational assistants (EAs) Low pay and limited hours have led to many EAs working multiple jobs to make ends meet. A recent Globe and Mail article (Capobianco, 2023) reported that Nova Scotia’s lowest-paid EAs earned just $16 an hour, and that, according to the President of CUPE local 5047, “many EAs and support staff work two or three jobs to make ends meet. Some have even left the field for fast food and retail because of the low wages and the tough nature of the work.”

We have found the same in B.C. EAs experience difficult work with challenging students, with low pay and limited hours. The results? Increased WorkSafe BC claims,1 more sick leave accessed than other staff, and a high turnover of EAs. EA illness

and turnover have ripple effects2 on other EAs, teachers, and principals, increasing their workloads and reducing wellbeing. Addressing this system-wide problem by creating full-time, better-paid jobs would impact workplace wellbeing for all staff.

2. Rethink school district management/union roles and relationships.

Teacher and other unions tend to be reactive organizations. But addressing workplace wellbeing requires stakeholders to collaboratively consider data and act together to find solutions. When working with districts as EdCan Advisors,3 we have utilized the Guarding Minds at Work survey,4 conducted interviews with a range of staff, and accessed demographic, sick leave, and other data. These combined data sources, as well as reports we generate, can be used in management-union collaborations to jointly develop action plans.

A new form of proactive, collaborative social entrepreneurship might be considered, where ideas to improve wellbeing emerge from all stakeholders, and where consensus should be developed on proposed solutions. Both union and management can build trust by co-creating solutions and by working together to support wellbeing.

3. Rethink the concept of leadership.

Being a compassionate leader is a fine idea, but being a collaborative one is better. Hierarchical school systems are reflected in job titles like Superintendent, CEO, and Executive Team. Many progressive leaders within these roles utilize collaborative approaches and encourage

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 15

ILLUSTRATION: ISTOCK

innovation within their organizations. But others do not, and autocratic leadership, especially in school principals, has been found in our work to have negative impacts on teacher and support staff wellbeing, while more collaborative and less autocratic principals have improved wellbeing in their schools.

Leaders can support systemic approaches by:

• setting policies to guide approaches

• initiating systemic change when there is consensus that such changes are needed

• creating staffing and budgets to implement action

• enabling innovation at schools and worksites

• extending collaborative approaches with unions.

4. Rethink the role of the individual while addressing the core systemic issues that impact workplace wellbeing.

Everyone who works as an employee in a K–12 Canadian school district is part of a system. Yet how often does one hear “the system” discussed as though those working in it are not part of it? If I work in a system, I need to take some responsibility to make it better. But if my workload is excessive, my stress is high, and some of my professional connections and relationships are problematic, giving me one more job is not going to help.

So, what to do? The answer is simple – reduce workload and stress. But how to do it is not. We as EdCan Advisors have found two useful starting points:

• Separate contractual and non-contractual issues. Not all workload issues are contractual, and while ideally, workload might be addressed in contracts, the reality is that much can be done to improve wellbeing outside of contract negotiations. As an example, addressing negative professional relationships can impact wellbeing (Naylor, 2020).

• Find and address the “low-hanging fruit”: steps that can be initiated quickly and with little controversy. These might include improving meeting processes, reducing email use, and limiting after-hours and weekend messaging, or encouraging senior district staff to visit schools and worksites to build connections and relationships while offering positive feedback and encouragement when appropriate.

As these progress, longer-term systemic approaches can be the focus of dialogue and planning, perhaps to address issues of racism or discrimination, or shifting school and district culture into more positive spaces.

5. Address racism and discrimination toward Indigenous and racialized staff and incorporate more

Indigenous approaches into wellbeing initiatives. One way to address racism in schools is to hire greater numbers of Indigenous and racialized teachers and other staff. A Rideau Foundation effort to boost Indigenous teachers was reported by McKenna (2023), and stated that in Winnipeg, 16.9 percent of students identified as Indigenous but only 8.6 percent of teachers were Indigenous. This lower ratio of Indigenous staff compared to districts’ Indigenous student populations is repeated in many Canadian school districts. Systemic approaches to combatting racism and discrimination require more Indigenous teachers and racialized staff in schools. This is a more complex issue than recruitment, as some Indigenous people have stated they are reluctant to participate in what they still consider a predominantly colonial system. Indigenous staff

report hearing racist and discriminatory comments from students, staff, or parents, comments which impact their wellbeing. Indigenous support staff have told me of bullying and harassment at work linked, in their view, to being Indigenous, female, and of low status in school districts.

At the same time, many non-Indigenous teachers are making significant efforts toward respectful access to both Indigenous knowledge and people. Others are apprehensive about cultural appropriation or fear to offend.

Just as decolonization is a work-in-progress, so will addressing wellbeing with anti-racism efforts take time and careful dialogue before significant changes are seen. McKenna also offers some thoughts on the complexity of the issue, identifying historical, cultural and current contextual issues, including “ongoing trauma connected to education that stems from residential schools, as well as colonial curriculums and a general lack of cultural safety in public education.”

While a significant dialogue with Indigenous and racialized people is needed, steps can be made while the bigger picture is explored. In one B.C. school district, Indigenous staff have stated that they do not trust either management or union processes to deal with racism, discrimination, or harassment. They prefer more restorative processes to address racist attitudes and actions. Evidence from districts that have utilized restorative approaches suggests such processes improve wellbeing for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff.

A similar focus to that on Indigenous and racialized staff might be placed on LGBTQ2+ staff in schools, perhaps with a focus on wellbeing for LGBTQ2+ staff in rural areas, where U.K. research (Lee, 2019) has outlined high levels of depression and anxiety among LGBTQ2+ teachers.

6. Address workplace wellbeing as a gendered issue.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health reports: “More than 75% of suicides involve men, but women attempt suicide 3 to 4 times more often than men” (CAMH, 2023).

The Canadian Women’s Foundation (Senior & Peoples, 2021) states: “Women experience depression and anxiety twice as often as men. Women in heterosexual pairings have long taken the position of ‘designated worrier.’ They tend to bear the brunt of the anxiety about family health and wellbeing. Of course, the data shows how worry work comes at the expense of a mother’s own health and wellbeing.”

Women comprise around 75 percent of many school district workforces. Yet there is a surprising lack of focus on women’s wellbeing and mental health in many school systems. Systemic change in a workforce largely populated by women requires a focus on women. Work-life balance can be difficult for women who often still have the primary care responsibilities within families, and even more so for those in the “sandwich generation” who are supporting both children and aging parents.

Teacher demographics in many school districts currently show more younger teachers, as retirements surge. New patterns are emerging with this changing demographic. One I have heard recently in B.C. school districts is that many younger teachers arrive shortly before the morning bell and are gone shortly after schools close in the afternoon, a pattern differing from some more experienced and older teachers, who often chat and collaborate after students leave. Teachers with young families have many demands at home that may limit the “after-hours” time they can spend at school. But younger staff in K–12 schools may also be protecting their own work-life bal-

16 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

ance by putting limits and boundaries on their work.

How to address the wellbeing of women staff in schools?

Look at the data. Are women taking leaves, accessing EFAP or short/long term rehabilitation programs proportionately more than males, and if so, in which roles? But if supporting collaborative approaches with systemic support resonates with districts, it is also crucial to start conversations with women staff at every status level about their wellbeing.

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENTS should be more active in supporting systemic approaches to wellbeing. Adopting some or all of the six factors explored in this article to a school district’s context might create strong foundations. Initiating short-term action would build momentum and ease districts into addressing tougher issues over the longer term. Systemic action is possible with the right leadership, staffing, and funding, a focus on data, and effective collaboration, facilitation, and implementation to build workplace wellbeing.

It’s not easy and there’s no exact recipe, but systemic improvements can be made. Let’s do what we can and share what we learn. EC

NOTES

1 BC WorkSafe accepted claims for EAs rose by 83.33% from 2017-2021. Data from FOI request made by author.

2 Dr. Fei Wang’s (2022) study (p. 76) also considered the concept of “ripple effects” on other staff where there existed limited psychological safety among school principals.

3 https://k12wellatwork.ca/advisors

4 https://www.workplacestrategiesformentalhealth.com/resources/guardingminds-at-work

REFERENCES

B.C. Ministry of Education. (2020). Mental health in schools strategy. Government of British Columbia.

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/erase/documents/mental-health-wellness/ mhis-strategy.pdf

Capobianco, A. (2023, May 24). Halifax education workers’ strike continues. Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-halifax-education-workersstrike-continues/

Lee, C. (2019). How do lesbian, gay and bisexual teachers experience UK rural school communities? Social Sciences, 8(9), 249.

https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/8/9/249#:~:text=Results%20showed%20 that%20LGB%20teachers,%2Dworth%2C%20depression%20and%20anxiety Maté, G., with Maté, D. (2022). The myth of normal: Trauma, illness and healing in a toxic culture. Knopf Canada.

McKenna, C. (2023, March 28). Finding the Knowledge Keepers: The Indigenous teacher shortage. The Walrus

https://thewalrus.ca/finding-the-knowledge-keepers-the-indigenous-teachershortage/

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2023). Mental illness and addiction: Facts and statistics.

https://www.camh.ca/en/driving-change/the-crisis-is-real/mental-healthstatistics

Naylor, C. (2020). The Powell River Learning Group: Improving professional relationships.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1nSs5ZGmqQkYWCxqio42JehlV473kqm_l/view Senior, P., & Peoples, A. (2021, June 7). The abysmal state of mothers’ mental health. (2021, June 7). Canadian Women’s Foundation.

https://canadianwomen.org/blog/the-abysmal-state-of-mothers-mental-health Wang, F. (2022, October). Psychological safety of school administrators: Invisible barriers to speaking out. University of British Columbia.

https://edst-educ.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2022/10/Psychological-Safety-of-SchoolAdministrators-v7-Final.pdf

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 17

Jennifer E. Lawson, PhD, is the senior author of the new book, Teacher, Take Care: A guide to well-being and workplace wellness for educators, as well as the originator and program editor of the Hands-On series published by Portage & Main Press. Jennifer is a former classroom teacher, resource and special education teacher, consultant, principal, university instructor, and school trustee.

Richelle North Star Scott (Giiwedinong Anong) is a Knowledge Keeper and writer of Anishinaabe and Métis descent, and her Ancestors are from St Peter’s Reserve. She is a Mide woman, Pipe Carrier, Water Carrier, and Sundancer. She has completed her mystery* in land-based education. (*She doesn’t use “master,” as it is a gender-binary word.)

Exploring the Sacred Hoop An Indigenous perspective on educator wellbeing and workplace wellness

BY JENNIFER E. LAWSON AND RICHELLE NORTH STAR SCOTT

HOW DO WE INFUSE INDIGENOUS perspectives into our work on educator wellbeing and workplace wellness? This is the question our writing team asked ourselves as we began working on the book, Teacher, Take Care: A guide to wellbeing and workplace wellness for educators. We wanted to infuse Indigenous knowledge throughout the book as a means of widening the lens on what it means to be well. Our Elder, Stanley Kipling, and Knowledge Keeper, Richelle North Star Scott, guided us in this process, using the Sacred Hoop as a model for wellbeing. We used this image as a foundation for understanding how to find balance and harmony within ourselves and within our schools. This article will explore the Sacred Hoop, its meaning, and the ways in which we have applied it to educator wellbeing and workplace wellness.

A holistic view of wellness

“The circle [Sacred Hoop], being primary, influences how we as Indigenous peoples view the world. In the process of how life evolves, how the natural world grows and works together, how all things are connected, and how all things move toward their destiny. Indigenous peoples see and respond to the world in a

circular fashion and are influenced by the examples of the circles of creation in our environment. They represent the alignment and continuous interaction of the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual realities. The circle shape represents the interconnectivity of all aspects of one’s being, including the connection with the natural world. [Sacred Hoops] are frequently believed to be the circle of awareness of the individual self; the circle of knowledge that provides the power we each have over our own lives (Dumont, 1989).”

We each have our own definition of wellness, whether we have articulated it or not. One understanding of holistic health and harmony is reflected in the Sacred Hoop. The Sacred Hoop is a representation of how some Indigenous Peoples view the world. It is also known by other names, such as Cosmological Circle, Circle Teachings, Hoop Teachings, Medicine Wheel, or Wheel Teachings. (Many Indigenous communities are trying to break free from using references to the Medicine Wheel and Wheel Teachings, as these are colonial terms.) There are many different perspectives on the Sacred Hoop, depending on nation, territory, and personal interpretations. A common

18 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

SYSTEMS THAT SUPPORT WELLBEING

theme, as represented in the Sacred Hoop by the Four Directions, is that wellness involves the whole person – their Physical, Emotional, Mental, and Spiritual selves. The Sacred Hoop shown here is the one that Elder Kipling and North Star are most familiar with. It supports their thoughts and ideas and has shaped the teachings they have received throughout their lives. When using the Sacred Hoop, it also is a reminder that we are not perfect – that as individuals we will go around the Sacred Hoop many times in our lifetime and that we are never done our healing. Wellness is not a destination, so we must think of it as endless teachings as we venture through life.

In the Sacred Hoop, the Physical dimension is represented by babies and children, as their physical bodies do much growing and learning when they are new to this world. The Golden Eagle sits in the East as a teacher of unconditional love for our children. The colour yellow represents the rising sun and the gift of a brand-new day.

Nourishing a healthy body through exercise, nutrition, and sleep are ways to promote physical wellness.

The Emotional dimension is represented by teenagers, who experience a wide range of emotions during a time of hormone changes in their lives. The Wolf sits in the South as a teacher of humility. As true leaders, wolves are humble. Although often misrepresented as wild and dangerous animals by settlers, they care for the pack even if it means their needs are not met. The colour red represents the red-hot emotions we may have during this life stage. We are teaching emotional wellness when we allow ourselves and others to experience feelings in a safe environment. Expressing emotions is a natural way to bring ourselves back into balance.

The Mental dimension is represented by adults, who spend much of their time in cognitive thought. Actually, they also often overthink and then worry about the decisions they have to make or the con-

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | September 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 19

Sacred Hoop image from Teacher, Take Care: A guide to well-being and workplace wellness for educators, by Jennifer E. Lawson. Copyright 2022, Reproduced with permission from Portage & Main Press.

sequences of the decisions they have already made. The Black Bear sits in the West as a teacher of courage, as it takes courage to go deep within our minds and learn about patterns that no longer serve us. The colour black represents our minds and the introspection it takes to journey through our lives. Being engaged in the world through learning, problem-solving, and creativity can improve our mental wellness. Learning is an ongoing, ever-evolving, lifelong process. It keeps us forever moving and growing and prevents us from getting stuck or becoming stagnant.

The Spiritual dimension is represented by Elders because they have great knowledge, having travelled the path around the entire Sacred Hoop. The White Buffalo sits in the North as a teacher who teaches us about facing the toughest of challenges head-on. Because of this, both the Elders and the White Buffalo deserve much respect. The colour white represents the harsh weather we must face and the wisdom our Elders have gained, often turning their hair white in the process. The Spiritual is that which fills us up. For some, Spirituality means connecting to our higher power, whether we call it Creator, God, Buddha, or Allah. For others, it means something different, such as that which embraces our soul, giving our lives meaning. The Spiritual also means the fire within us – our pursuits that fill us up when we feel empty. These can be dancing, singing, attending ceremonies, or painting – things that make us feel whole again. As we go deeper within ourselves, committing to another walk around the Sacred Hoop, spirituality keeps us grounded, creative, and inspired.

Finding balance

So, how do we live in harmony and find balance using the Sacred Hoop? It begins with an understanding of the equal importance of our Physical, Emotional, Mental, and Spiritual dimensions. It means acknowledging and caring for those four aspects of our whole being by keeping them in balance. Think, for a moment, about standing on a Bosu ball at the gym, and imagine that the ball’s round, flat circle is your Sacred Hoop.

not eating properly because I’m constantly on the move from one school to another and I’m not eating lunch at appropriate times. In addition, once I’m at a school, I am either teaching in a classroom or I am attending meetings in small conference rooms, requiring me to sit. So my Sacred Hoop is out of balance. I’m not eating well or exercising and that throws my Physical wellbeing out of balance. As soon as my Physical self suffers, my Emotional wellness also becomes askew. In contrast, my Mental health and Spiritual life are strong. I am constantly learning, reading, and writing, and I challenge myself mentally all the time. I am always in ceremony, so my spirit is strong. This means that I must be aware of both my strengths and challenges in my Sacred Hoop. As I become aware of where I am the strongest on my Hoop and where I am needing some support, I can seek out help to rectify this, knowing that the Physical and Emotional aspects of my life are out of balance. One thing that has always helped me with my diabetes and supporting the Physical and Emotional aspects of my Hoop is being out on the land. There I find I’m moving more and releasing any negative emotions, and so I often try to teach out on the land. I am taking care of myself, as well as my colleagues and students, as I introduce them to healing out on the land.

Jennifer: I find it important to be cognizant of my strengths and challenges in terms of my four dimensions. For example, in a Physical way, I am quite strong, active, and healthy. I walk outdoors daily and take Zumba classes several times a week. I also see my Mental dimension as quite strong, as I challenge my learning and thrive on gathering new knowledge. My Spiritual dimension is enhanced by my time immersed in music and nature. However, my Emotional dimension is where I struggle. I am what one would call an empath, highly sensitive, and can be easily overwhelmed by my own emotions. This makes it difficult for me to balance my own Sacred Hoop. I try to recover this imbalance by focusing on my strengths (Physical activity, Mental stimulation, Spiritual endeavours), while also acknowledging, articulating, and accepting my Emotions. This helps me to find balance, harmony, and wellbeing in daily life.

We are at the centre of our own wellbeing and healing. If we keep ourselves at the centre and take care of ourselves, then we can also take care of others. Often, as teachers, we are constantly taking care of everyone else, in both our personal and professional lives, and we can forget to take care of our own daily needs. As we journey around the Sacred Hoop, we need to be having that internal conversation about how we’re feeling throughout the day. Are we in balance?

Community and workplace wellness

Using this analogy, the goal is to keep yourself steady and balanced in all four dimensions of your being. If you are struggling in one area, it will indeed affect your overall sense of harmony. If you are challenged in more than one area, it may be difficult to maintain equilibrium at all.

How can we manage to find balance? Here, we will provide an example from each of us on how we strive to maintain a sense of wellbeing and harmony in our daily lives.

North Star: I am diabetic, and I struggle from day to day to maintain my blood sugar levels. Teaching can often be stressful, and my job keeps me extremely busy meeting 26 schools’ needs. I’m often

The Sacred Hoop can also be used to determine and strengthen balance, harmony, and wellness in the workplace. For example, in schools, we need to consider all four dimensions – the Physical, Emotional, Mental, and Spiritual – as having equal influence on workplace wellness, and also the school community’s wellness.

The Physical dimension of a school, for example, involves every aspect of the community’s physical wellbeing, including the building itself. It is the right of every member of a school community to feel physically safe at all times. Unfortunately, this dimension also includes physical violence and injury, which puts both students and staff at risk. In addition, everything from temperature control and air quality to icy sidewalks and leaking ceiling tiles need to be attended to in order to maintain a well school. There is no easy answer to addressing these issues, but it is of utmost importance that Physical wellness and safety be at the forefront of managing facilities and

20 EDUCATION CANADA • September 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

PHOTO: ISTOCK

creating a well school. For many students, the land surrounding the school is important not only for their Physical needs, but also for their Emotional, Mental, and Spiritual dimensions. Many schools recognize this and are now actively integrating outdoor classrooms and land-based learning.