January 2023 Vol. 63 No. 1 $10 Publication 40031215 Display until April 18, 2023 TM Published by www.edcan.ca DECOLONIZING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING Co-designing with Elders n Critical incidents as learning opportunities n Education change networks

THIS SPECIAL EDITION, we partner with Memorial University to present a series of articles exploring how education professionals can “unlearn” colonial ideas and practices and work toward equity in education.

FOR

NOTE A Call to Action 6 NETWORK VOICES Gathering Together for Educational Change

By Joelle Rodway, Carol Campbell, Sara Florence Davidson, Ann Lopez, Sylvia Moore, Nicholas Ng-A-Fook, and Leyton Schnellert

Decolonization Terms Explained 12 Learning How to Co-Design with Elders On the nature of unlearning By Sharon Friesen 16 Critical Incidents in Educational Leadership An opportunity for professional (un)learning By Mélissa Villella 22 Welcoming Indigenous Ways of Knowing Decolonizing and building relationships through education change networks

By Leyton Schnellert, Sara Florence Davidson, Nikki Yee, and Bonny Lynn Donovan

Equity in Teaching and Learning Living, being, doing By Karen Ragoonaden

WEB EXCLUSIVES www.edcan.ca/magazine

Decolonization Through Two-Eared Listening The integral role of listening to Indigenous community voices and stories

By Sylvia Moore, Joelle Rodway, and dorothy vaandering

The Urban Communities Cohort A partnership in professional unlearning and relearning

By Linda Radford and Ruth Kane with Kristin Kopra, Sherwyn Solomon, and Geordie Walker

Professional Learning in a Community of Relations Engaging head, heart and spirit in reconciliation with the Caring Society

By Lisa Howell, Nicholas Ng-A-Fook, and Barbara Giroux

Disrupting “Professionalism” in Education The need to decolonize and create spaces of belonging By Ardavan Eizadirad, Mélissa Villella, and Jerome Cranston

ON THE COVER

Members of the Welcoming Indigenous Ways of Knowing Change Network gather together for land-based teachings from local Indigenous knowledge-keepers.

COVER PHOTO: Leyton Schnellert

WELL AT WORK Wellness Includes the Brain By Jennifer Fraser

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 3

5 EDITOR’S

9

January

Contents 12 22

26

2023 n Vol. 63 No. 1 n www.edcan.ca

PHOTO: AMY PARK, GALILEO EDUCATIONAL NETWORK PHOTO : LEYTON SCHNELLERT

16 PHOTO: ISTOCK

Executive Editor Max Cooke English Editor Holly Bennett

Art Director Dave Donald Operations Manager Mia San José

Program Director of Well at Work Kathleen Lane

Development and Partnerships Manager Renuka Jacquette Marketing Manager Shanice Tadeo

Administrative and Project Coordinator Nour Naffaa

Graphic Designer/Digital Content Publisher Daniel Escate Advertising Sales advertise@edcan.ca

Publisher Canadian Education Association Chair Claire Guy

Canada Editorial Board

Marius Bourgeoys, cofondateur d’escouadeÉDU, conférencier, coach et consultant, L’Orignal, ON

Dr. Curtis Brown, Retired Superintendent, South Slave Divisional Education Council, Fort Smith, NT

Dr. Alec Couros, Director, Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Regina, Regina, SK

Nathalie Couzon, technopédagogue, Collège Letendre, Laval, QC

Grant Frost, President (Halifax County Local), Nova Scotia Teachers’ Union, Halifax, NS

Roberto Gauvin, Consultant en éducation chez Édunovis, Édunovis, Lac-Baker, NB

François Guité, consultant au ministère de l’Éducation, de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche (MEESR) du Québec, Québec, QC

Dr. Michelle Hogue, Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the First Nations Transition Program, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB

Normand Lessard, Secrétaire général, Association des directions générales scolaires du Québec, Sherbrooke, QC

Corinne Payne, Directrice Générale, Fédération des comités de parents du Québec (FCPQ), Québec, QC

David Price, Senior Associate, Innovation Unit, Leeds, UK

Zoe Branigan Pipe, Teacher, Hamilton, ON Cynthia Richards, Canadian Home and School Federation, Chipman, NB

Sébastien Stasse, directeur formation et recherche au CADRE21, Longueuil, QC

Dr. Joel Westheimer, University Research Chair in the Sociology of Education, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON

Andrew Woodall, Dean of Students, Concordia University, Montréal, QC

Dr. Christine Younghusband, Assistant Professor, University of Northern British Columbia School of Education, Prince George, BC

© 2023 Canadian Education Association/l’Association canadienne d’éducation ISSN 0013-1253

Publications Mail Agreement No. 40031215 HST/TVH # R100763416 www.edcan.ca

Rooted in the Canadian education experience and perspective, our English and French articles provide voice to teachers, principals, superintendents and researchers – a growing network of experts who examine today’s school and classroom challenges with courage and honesty. Pragmatic, accessible and evidence-based, Education Canada connects policy and research to classroom practice.

Education Canada is published three times yearly by the EdCan Network. 703-60 St. Clair Avenue East Toronto, ON M4T 1N5 Tel: (416) 591-6300; Fax: (416) 591-5345 publications@edcan.ca www.edcan.ca

Member of Magazines Canada

The EdCan Network no longer sells subscriptions to Education Canada. This publication is available to EdCan Network members only. Libraries, schools and academic institutions can still purchase subscriptions through a subscription agency.

Address all editorial correspondence to: Holly Bennett, Editor Education Canada editor@edcan.ca Tel: (705) 745-1419; Fax: (416) 591-5345

You are free to reproduce, distribute and transmit the articles in this publication, provided you attribute the author(s), Education Canada Vol. 63 (1), 2023, and a link to the EdCan Network (www.edcan.ca). You may not use the articles in this publication for commercial purposes. You may not alter, transform, or build upon the articles in this publication. Publication ISSN 0013-1253.

The views expressed or implied in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EdCan Network. Publication of an advertisement in Education Canada does not constitute an endorsement by the EdCan Network of any advertiser’s product or service including professional learning opportunities.

4 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Education

BY HOLLY BENNETT

A Call to Action

THERE’S A STORY that’s been circulating for too long in our country. It goes something like this: yes, empire-building and colonial rule did a lot of damage, but that was all long ago; over and done with. The problem is, it’s not over. The legacy of colonial attitudes, world views, and institutional structures lingers on.

For this edition of Education Canada, we are proud to partner with Memorial University to present a series of nine articles on Decolonizing Professional Learning, inspired by a gathering of researchers and educators committed to this work that took place in the summer of 2022. In this series, the authors share the decolonizing and reconciliation work they are doing and propose some promising approaches –from “two-eared” (deep, intentional, and non-judgmental) listening to education change networks – that merit more widespread adoption.

While working on this edition, we grappled with how to tackle the systemic racism that unfolds in our school districts every day. We know that colonialist practices are difficult to discern if they are all you’ve ever experienced – so how can educators know what they don’t know? Decolonization is partly about learning to see the harmful assumptions behind and impacts of what we have believed to be the only way or “common sense.” We must make spaces where we can have the “Hard Conversations” (see “The Urban Communities Cohort,” by Linda Radford and Ruth Kane) and challenge our own thinking, so that we can make our education systems more inclusive. Above all, we must listen to racialized educators and students and learn from their lived experiences.

This edition of Education Canada is a beginning – a challenge for us all to reflect upon what’s happening in our schools and classrooms for students and staff who are Indigenous, Black or People of Colour. If you are new to these ideas, you might start with our introductory article, “Decolonizing Professional Learning: Gathering together for educational change,” which includes some definitions of frequently used terms.

In one of those serendipitous moments, I recently received a review copy of Wayi Wah! Indigenous Pedagogies: An act for Reconciliation and anti-racist education, by Jo Chrona (Portage & Main, 2022). If the articles you read here excite, inspire, or call you to action and you want to learn more, this book is a great next step (specifically for an Indigenous focus). With a compassionate and plainspoken voice, the author walks us through chapters on the role of educators in reconciliation and decolonization, Indigenous education and Indigenous-informed pedagogy, understanding systemic racism, and more. Every chapter includes questions for reflections, ways to take action, and resources for further learning and classroom use.

Finally, don’t forget that we now have companion podcasts! For this edition, host Stephen Hurley of voicEd Radio has produced a series of podcast conversations with individual authors. You can listen to them, and read all nine articles, here: www.edcan.ca/magazine/decolonizing-professional-learning. EC

Write to us!

We want to know what you think. Send your comments to editor@edcan.ca –or join the conversation by using #EdCan on Twitter and Facebook.

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 5

editor’s note

Joelle Rodway, PhD, OCT, is an Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy, Memorial University.

Carol Campbell, PhD, is a Professor of Leadership and Educational Change and Associate Chair of the Department of Leadership, Adult and Higher Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto.

Sara Florence Davidson, PhD, is a Haida/Settler Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University.

Ann Lopez, PhD, is a Professor, Teaching Stream of Educational Leadership and Policy at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Sylvia Moore, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the School of Arctic and Subarctic Studies, Labrador Campus of Memorial University.

Nicholas Ng-A-Fook, PhD, is a Professor of Curriculum Theory and Vice Dean of Graduate Studies at the University of Ottawa.

Leyton Schnellert, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the University of British Columbia’s Department of Curriculum & Pedagogy, and Pedagogy and Participation Research Cluster lead in UBC’s Institute for Community Engaged Research.

BY JOELLE RODWAY, CAROL CAMPBELL, SARA FLORENCE DAVIDSON, ANN LOPEZ, SYLVIA MOORE, NICHOLAS NG-A-FOOK, AND LEYTON SCHNELLERT

Decolonizing Professional Learning Gathering together for educational change

The impetus

IN 2019, THREE of us (Leyton, Joelle, and Carol) attended a conference in San Diego that focused on professional learning networks (PLNs), with a specific emphasis on how they enable educators to “tear down boundaries” to connect and learn with colleagues beyond our own schools. It was a productive meeting of scholars from North America and multiple European countries. The group focused on professional learning, collaborative inquiry, and educational change, sharing varied perspectives. But as we reflected on our learning, we began talking about what wasn’t part of this conversation: the ways in which PLNs can reproduce colonial ways of knowing and being, by:

• excluding the voices and experiences of racialized and minoritized educators

• centring Western ways of knowing at the expense of other knowledge systems

• maintaining strategies that, even though they purport to challenge the status quo by “tearing down boundaries,” continue to operate in ways that maintain

the structural systems that harm and marginalize so many people.

In fact, little attention has been paid to the colonizing practices and assumptions embedded in the vast majority of professional learning (PL) initiatives (Washington & O’Connor, 2020). Donald (2012) describes the colonial project as one of division, excluding ways of being and knowing as well as value systems that are different from a Eurocentric point of view. Present-day education systems are implicated in this colonial project, where curriculum (a focus on constructing subject areas that privilege a particular type of knowledge), pedagogy (approaches to teaching and instruction), and classroom routines (e.g. grading, grouping) contribute to institutional structures that privilege some students to the expense of others who are often racialized and minoritized within this system (Yee, 2020).

Alas, from these observations, the idea for the Decolonizing Professional Learning event, held in St. John’s, N.L., in August 2022, was born. The 30 participants were educators and researchers from across the country who were already working to develop decolonizing education practices. They were focused on cultivating culturally sustaining, relational pedagogies in ethical relationship with equity-deserving communities (Donald et al., 2011; Ermine, 2007). The central goals of the gathering were two-fold: 1. To find synergies between regionally based professional learning (PL) programs of research that take up decolonizing pedagogies and leadership practices; and

6 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

network voices

PHOTO: NICHOLAS NG-A-FOOK

2. To initiate a national PL education equity network that would enable members to leverage one another’s research, policy, and pedagogical contributions in order to decolonize PL practices and policies.

Ultimately, our goal is to rethink and reconstitute professional learning as a collaboratively constructed, transformative, and decolonial practice.

What is decolonization?

At the centre of the gathering was the concept of decolonization Decolonizing professional learning is about decentring settler colonial practices and their curricular and pedagogical Eurocentricities. All levels of education in Canada are working to implement initiatives that respond to the 94 Calls to Action put forth by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015). In turn, terms such as decolonization, reconciliation, and Indigenization are now being taken up in higher education and the K–12 schooling systems.

The scholars and practitioners who attended the gathering came together to discuss their understanding of decolonizing and how they promote this concept in research and professional learning. Some drew on the concept of decolonizing education as intentionally identifying, challenging, and dismantling colonial practices and policies (Lopez, 2021), while others focused on interrogating and unlearning colonial ideologies (Donald, 2022).

The intent of the gathering was not to agree on a single definition of decolonization, but rather to share ideas and create a network for learning in which we move forward together. We came together guided by our “learning spirits” (Battiste, 2013, p. 18), sharing the

stories of our collective work to disrupt colonial school systems in our local settings.

In this special issue of Education Canada, we share some of these stories with you.

Design and processes for authentic unlearning

There is an assumption of neutrality in professional development approaches; therefore, we sought to disrupt the “typical” conference format when designing this event. We wanted a less hierarchical approach – so instead of having a few presenters deliver an address to a largely passive audience, we offered a series of collaborative experiences. Across the three days, we worked to create space for all participants to share their work within small groups of interested teachers, administrators, and researchers.

The gathering was guided by a series of questions, for example:

• Where are we coming from? How do we situate ourselves as educational leaders and researchers in these spaces?

• What work and research are we doing in our representative regions to decolonize professional learning in the context of K–12 education? What can we learn from each other?

• In what ways are we disrupting conventional views of professional learning to create spaces that honour multiple knowledges and ways of knowing?

Coming together: The event began at a small gathering place at a local park. Mi’kmaw knowledge keepers Sheila O’Neill and Marie Eastman welcomed participants to the traditional territory of the Beothuk and Mi’kmaq. Following introductions, they shared some of the history of the land, discussed the ongoing struggle for the

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 7

recognition of Indigenous Peoples in the province, and talked about their work with Mi’kmaw communities to strengthen the language and culture.

Small fires: Each day, participants could choose from among three to five “small fires,” each hosted by one of the attendees. In these small groups, the hosts shared their research and practice related to decolonizing professional learning. Each SSHRC-funded participant served as a small fire host on one day of the program.

Sharing circles: Once each day we came together in Sharing Circles. Participants chose one of three different circles – such as mindfulness practice, nature walks, and talking circles – to participate in. Attendees reflected on what they were noticing or wondering, and connections they were making to their own practice. These sharing circles invited deeper conversations about what we heard in the small fires and our experiences in different contexts (K–12 schools, postsecondary institutions, communities).

Writing activities: To support the building of connections within this emerging community, we embedded daily opportunities for collaborative writing. We began by inviting everyone to write about their own decolonizing work. Next we invited people to explore the connections and intersections between their work and the work of others. We hoped that discovering these relationships would encourage continued collaboration and sharing once everyone returned to their communities.

VoicEd panels: Two live-streamed panel discussions were hosted by Stephen Hurley from voicEd Radio. Colleagues discussed colonization and placelessness, disrupting deficit thinking, inclusion and exclusion, educational change networks, and more. Online participants were encouraged to submit questions to the panel. Recordings of the Decolonizing Professional Learning panels are available on voicEd Radio.

Final sharing circle: To end the gathering, we all joined in a final circle to share our thoughts about our time together and how we might move forward together. Each person had a turn to share what they thought were key themes, next steps, and opportunities missed. Attendees spoke of forming a network, meeting together virtually and/or in person, writing an edited collection of chapters, presenting together at conferences, and this Education Canada issue.

What was evident to us all was that we had not collectively defined decolonization, and that future collaborations between us need to both honour the diversity of our approaches and include opportunities to define key terms and expectations. In this debrief, participants also surfaced the different aspects of power and privilege we carry and/ or do not have in our various roles and contexts. Our identities, roles, and educational change efforts can and must be returned to as part of decolonizing work, and trying to move too quickly to consensus and definitions is counterproductive. This work takes patience and time.

Moving forward

The Decolonizing Professional Learning gathering that took place in Newfoundland was a starting point for what we hope will become a larger conversation and impetus for collaborative action across Canada. There is already some pan-Canadian work that genuinely connects researchers and practitioners with a commitment to educational change and improvement. We know from previous research that a considerable number of professional learning activities are happening across Canada, but there are inequities in access to quality professional learning for people who work in education (Campbell et al., 2017). There is also a need to consider the purpose and content of such professional learning. If educators are to care for all students and support them in developing to their fullest potential, it is essential that professional learning activities for educators are critically examined to ensure that structural inequities are not un/ intentionally reproduced.

We are at a moment in time when valuing Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, fulfilling the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and addressing and undoing systemic racism from generations of colonialism and genocide are urgent and essential. This is the call to move forward with conversations to understand and share approaches to decolonizing professional learning and to act together – researchers, practitioners, and policymakers – for educational equity and improvement in Canada.

An important starting point is for further discussion about the concept of “decolonizing professional learning” itself and the linked work of “unlearning” historically embedded assumptions. As educators, it is our job to continuously learn, but that can be challenging when confronting ingrained colonial ways of seeing and living in the world. We also need to consider what this work looks like in practice. Bringing together practitioners with applied researchers was a beginning, but it is important to share our stories, our evidence, our ideas, and our examples widely. Deprivatizing individual or isolated practices and mobilizing knowledge by sharing in conversations and communications are powerful strategies.

This collection of articles for Education Canada is a way to reach out and call on people across Canada (and beyond) to join in connecting, collaborating, and sharing to advance decolonizing professional learning in and through education. EC

REFERENCES

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing Limited.

8 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Campbell, C., Osmond-Johnson, P., et al. (2017). The state of educators’ professional learning in Canada: Final research report. Learning Forward. https://learningforward.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/state-of-educatorsprofessional-learning-in-canada.pdf

Donald, D. (2022, September 19). A curriculum for educating differently: Unlearning colonialism and renewing kinship relations. Education Canada, 62(2). www.edcan.ca/articles/a-curriculum-for-educating-differently/ Donald, D. (2012). Forts, colonial frontier logics, and Aboriginal-Canadian relations: Imagining decolonizing educational philosophies in Canadian contexts. In A. A. Abdi (Ed.), Decolonizing philosophies of education (pp. 91–111). SensePublishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6091-687-8_7

Donald, D., Glanfield, F., & Sterenberg, G. (2011). Culturally relational education in and with an Indigenous community. Indigenous Education, 17(3), 72–83.

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193–203.

Decolonization Terms Explained

IT IS IMPORTANT TO SHARE the understandings that guide and frame decolonization work. Below we offer working definitions of some key terms, recognizing that these terms can have different meanings in different contexts.

Decolonization: Decolonization is about decentring Eurocentric, colonial knowledge and practices, and recentring knowledge and world views of those who have been placed on the margins by colonization.

Decolonization involves active resistance to colonial practices and policies, getting rid of colonial structures, and centring and restoring the world view of Indigenous peoples. It demands an Indigenous starting point; Indigenous people will determine appropriate approaches and acts of decolonization. It also involves recognizing the importance of land – in particular, how colonized peoples were cut off from their land and traditions – and the return of land to Indigenous peoples.

Indigenization: Indigenization calls on educational institutions and stakeholders to establish policies, processes, and practices that are led by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples toward ensuring their particular ways of knowing, being and doing are nourished and flourish.

This includes creating opportunities for K–12 school leaders and teachers to learn how to develop and enact curriculum that honours First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples’ histories, perspectives, and contemporary issues. It also calls on school leaders and teachers to embed relational and responsive culturally nourishing pedagogies and curricula as part of the values of their K–12 school community.

Positionality: Positionality refers to one’s identity – how we position ourselves within our society. To identify your own positionality, you need to consider your own power and privilege by thinking about issues of race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, educational background, citizenship, and so on.

As educators, our positionality impacts how we make sense of the world and how we engage in it. It takes self-assessment

Lopez, A. E. (2021). Decolonizing educational leadership: Exploring alternative approaches to leading schools. Springer International Publishing AG, ProQuest Ebook Central.

http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mun/detail.action?docID=6450991

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, education and society,1(1), 1–40.

https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/issue/view/1234

Washington, S., & O’Connor, M. (2020). Collaborative professionalism across cultures and contexts: Cases of professional learning networks enhancing teaching and learning in Canada and Colombia. In Schnellert, L. (Ed.), Professional learning networks: Facilitating transformation in diverse contexts with equity-seeking communities. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Yee, N. L. (2020). Collaborating across communities to co-construct supports for Indigenous (and all) students. [Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia.] UBC Library Open Collections.

https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0392533

and reflection to identify the ways in which our assumptions and beliefs, as well as our own expressions of power, influence how we (co-)create learning environments in our classrooms and schools.

Systemic racism: Systemic racism refers to the aspects of a society’s structures that produce inequalities and inequities among its citizens and specifically, the institutional processes rooted in White supremacy that restrict opportunities and outcomes for racialized and minoritized peoples.

Systemic racism includes institutional and social structures, individual mental schemas, and everyday ways of being in the world. Schools and school systems must engage in anti-racist education practice to address the systemic issues particular to racialized students.

Unlearning: Unlearning involves removing ideas, practices, and values grounded in coloniality and colonialism from everyday practice.

It is rethinking and reframing what we thought we knew about many aspects of everyday life, including traditions grounded in Eurocentric ways of knowing, and replacing it with decolonized knowledge.

RESOURCES FOR FURTHER LEARNING

Culturally Nourishing Schooling for Indigenous Education, University of New South Wales.

www.unsw.edu.au/content/dam/pdfs/unsw-adobe-websites/arts-designarchitecture/education/research/project-briefs/2022-07-27-ada-culturallynourishing-schooling-cns-for-Indigenous-education.pdf

Decolonizing and Indigenizing Education in Canada, Eds. Sheila Cote-Meek and Taima Moeke-Pickering.

https://canadianscholars.ca/book/decolonizing-and-indigenizing-educationin-canada

Indigenization, Decolonization and Reconciliation (chapter in Pulling Together: A guide for curriculum developers).

https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/chapter/ indigenization-decolonization-and-reconciliation

The UnLeading Project with Dr. Vidya Shah, York University. www.yorku.ca/edu/unleading

Universities and teachers’ associations provide myriad resources to support the development of anti-racist practices in schools. See, for example: www.ualberta.ca/centre-for-teaching-and-learning/teaching-support/ indigenization/index.html

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 9

Truth and Reconciliation Commission https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive_ Summary_English_Web.pdf

Learning How to Co-Design with Elders

On the nature of unlearning

BY SHARON FRIESEN

IN 2018, during their 50th anniversary, the Whyte Museum in Banff, Alberta, hosted an extraordinary sculpture exhibit of 100 human busts. Christine Wignall, the sculptor, reflected on her work:

“When I began the project, I thought I would simply start and see where the muse would lead. It wasn’t until I had completed about ten heads that I began to realize who they represented and from where they were coming. My memories and imagination were giving life to the clay and each one of the heads took on the character of someone I had known while growing up… Many of these folks are dead now, a lot of them, but they do haunt my memories. They walked the streets of Banff while the museum was being planned. It is good to remember them all.”

One of the reports on the exhibition stated, “Wignall captured the faces of prominent Banff people… the faces were so full of life” (Szuszkiel, n.d., para. 8). Indeed, the collection was impressive. But when I saw the exhibit with a colleague, what struck me was that 96 of the sculpted busts in the exhibit were those of individuals who had settled in the Banff area. The exhibition included four people from the Stoney Nakoda Nations.

The Stoney Nakoda, comprising the Chiniki, Bearspaw, and Wesley First Nations, are the first peoples in this region. And unlike all the other sculptures in the exhibit, only one of these four sculptures was of a named individual, Walking Buffalo. We wondered, if more people from the Stoney Nakoda Nations were to be included, who might those individuals be. Who were some of the

important members of the Nations?

I was fortunate to lead a professional learning and research organization, Galileo Educational Network (Galileo) in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary. Those of us at Galileo had a history of developing research-practice partnerships to engage in professional learning with teachers, principals, and district leaders. Galileo had an ongoing research-practice partnership with the school district in the Banff corridor, focused on nurturing excellence in instruction and leadership, also known in the district as NEIL. In one of the monthly co-design meetings with educators from the school district, we shared our observation about the exhibit at the Whyte Museum. We proposed that perhaps one of the teachers in the district might want to work with one of our professional learning mentors to engage in a project that would involve members of the Stoney Nakoda Nations to learn who from their Nations they considered to be important and to learn their stories. One of the public schools in the school district, whose population is comprised primarily of students from the Stoney Nakoda First Nations, was put forward by district leaders as the one most likely to have an interested teacher. A Grade 4 teacher, whose students were all from the Stoney Nakoda Nations, stepped forward.

The school’s success coach joined the first meeting between the Galileo mentor and the teacher. The success coach, who had worked with the Stoney Nakoda Education Authority for 18 years, brought a wealth of knowledge and expertise to the first design meeting. While offering to assist with the overall initiative, she also stated

12 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Sharon Friesen is a Professor in the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary. She was the Co-founder and President of the Galileo Educational Network from 1999–2021.

DECOLONIZING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

she could assist with making connections with Elders within the community. It was imperative to us at Galileo that Elders be involved in this project, right from the beginning of the design process. While we had engaged in a number of research-practice partnerships with First Nations communities and Elders prior to this one, this would be somewhat unique as we wanted to invite Elders to collaboratively design (co-design) the classroom activities and tasks with us. Having Elders as co-designers added a new and valuable dimension to this classroom initiative.

As this was not only a professional learning initiative, but also a research initiative, I felt it was important to take a participatory research approach. Within participatory design, the individuals involved in creating the design make a resolute commitment to ensure those who will be impacted by the design be significantly involved in the initial and subsequent iterative work of design (Bødker et al. 2004). In participatory design initiatives, the partners are not merely informants; rather, they are legitimate and acknowledged participants in the design process. In this initiative, the teacher, success worker, and the Elders contributed in all phases of the design work, and throughout all the iterations. As legitimate partners it is important that the participants “be involved in the making of decisions which affect their flourishing in any way” (Heron, 1996, p. 11). For it is through their participation they experience a sense of well being.

At the next meeting, four of the respected Elders from the Nations accepted our invitation to join us in conversation. They agreed to join the initiative; however, when it was suggested they provide the names of members – heroes from the Nations – they were not forthcoming with names. The Elders, although intrigued, spoke of

intellectual property, of acknowledging who “owns” the stories and who has the right to hear or to re-tell the stories. They spoke of the disconnect many students have to their own heritage, their families, and their identities. At this point they saw an opportunity that those engaged in the previous design work had not seen. The Elders saw an opportunity for the students to learn about who they are by having them identify their own ancestors and trace who they are related to. The Elders wanted to work directly with the students to help them connect with their culture, their community, and their own families. They were confident they would be able to help each student trace back their lineage to a Stoney Nakoda “hero.” Through genealogy, students would then have the intellectual property rights to the stories of their own ancestors. As the Elders instructed, the students’ ancestors’ stories are their stories.

Over the following month, the teacher worked with the students and their families to identify the names of family members. Most students came back with family trees that extended to their grandparents. Some had more. Some had less. Regardless of what students were able to come up with, it would serve as a starting point for the next step.

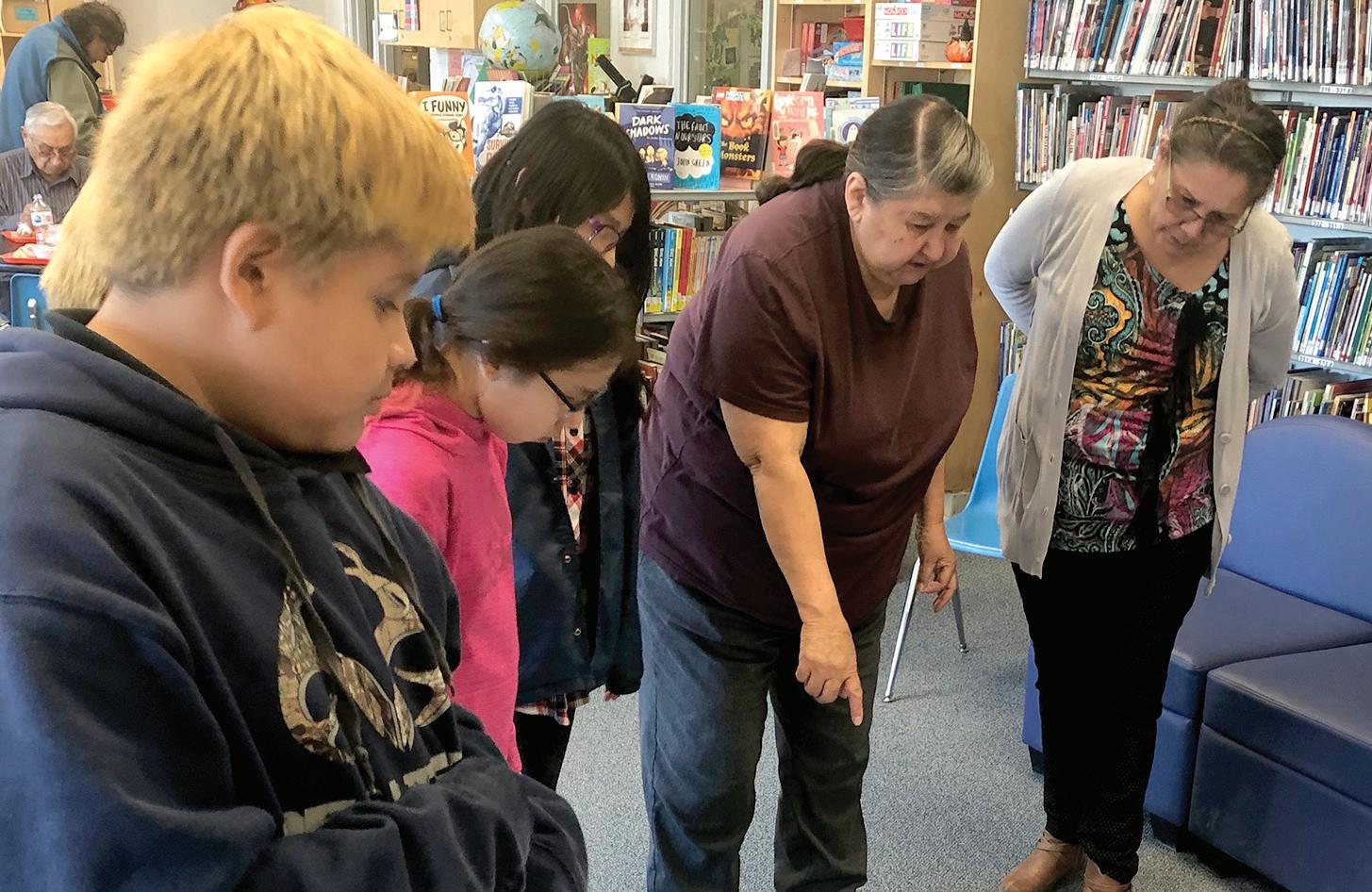

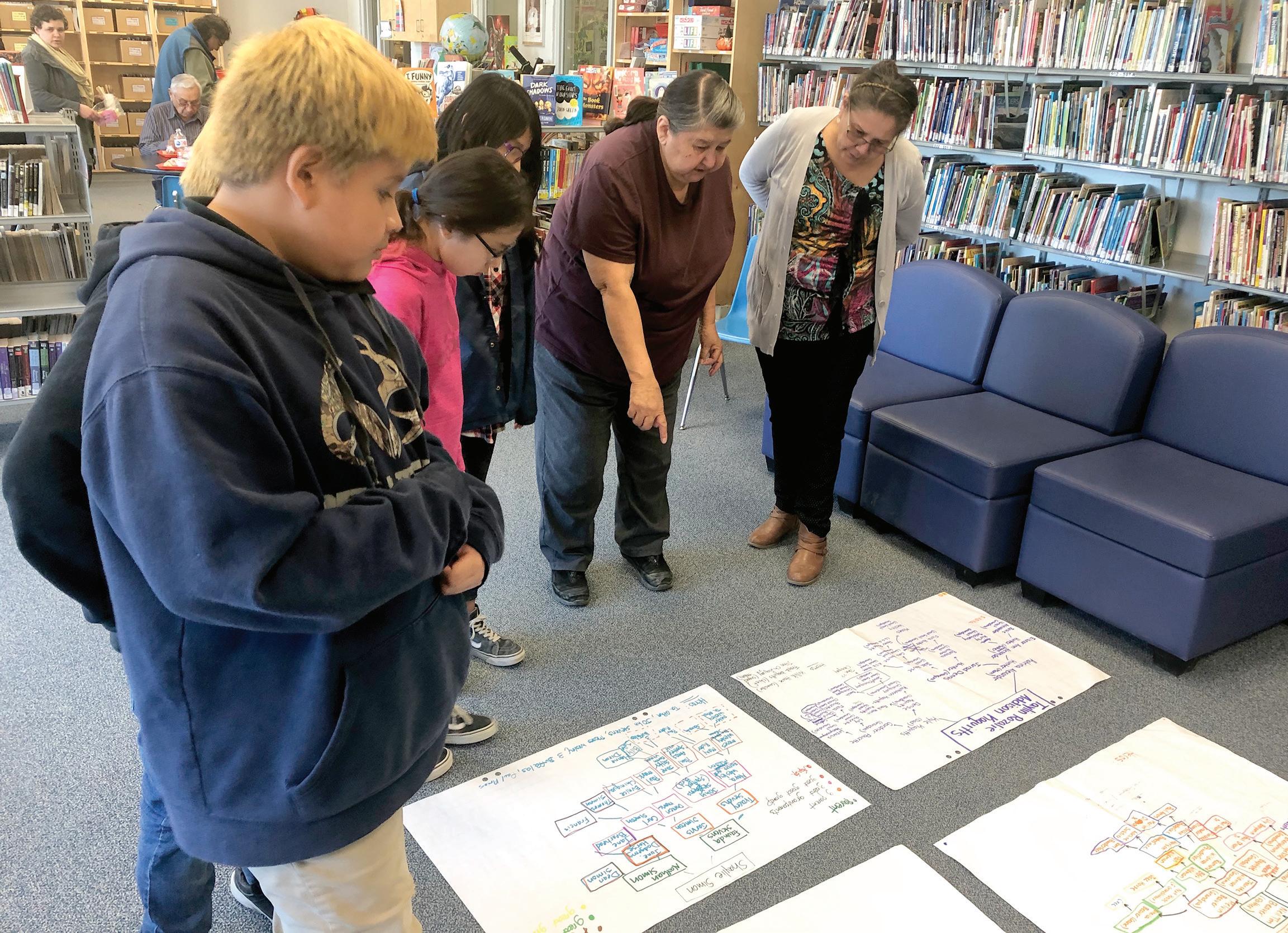

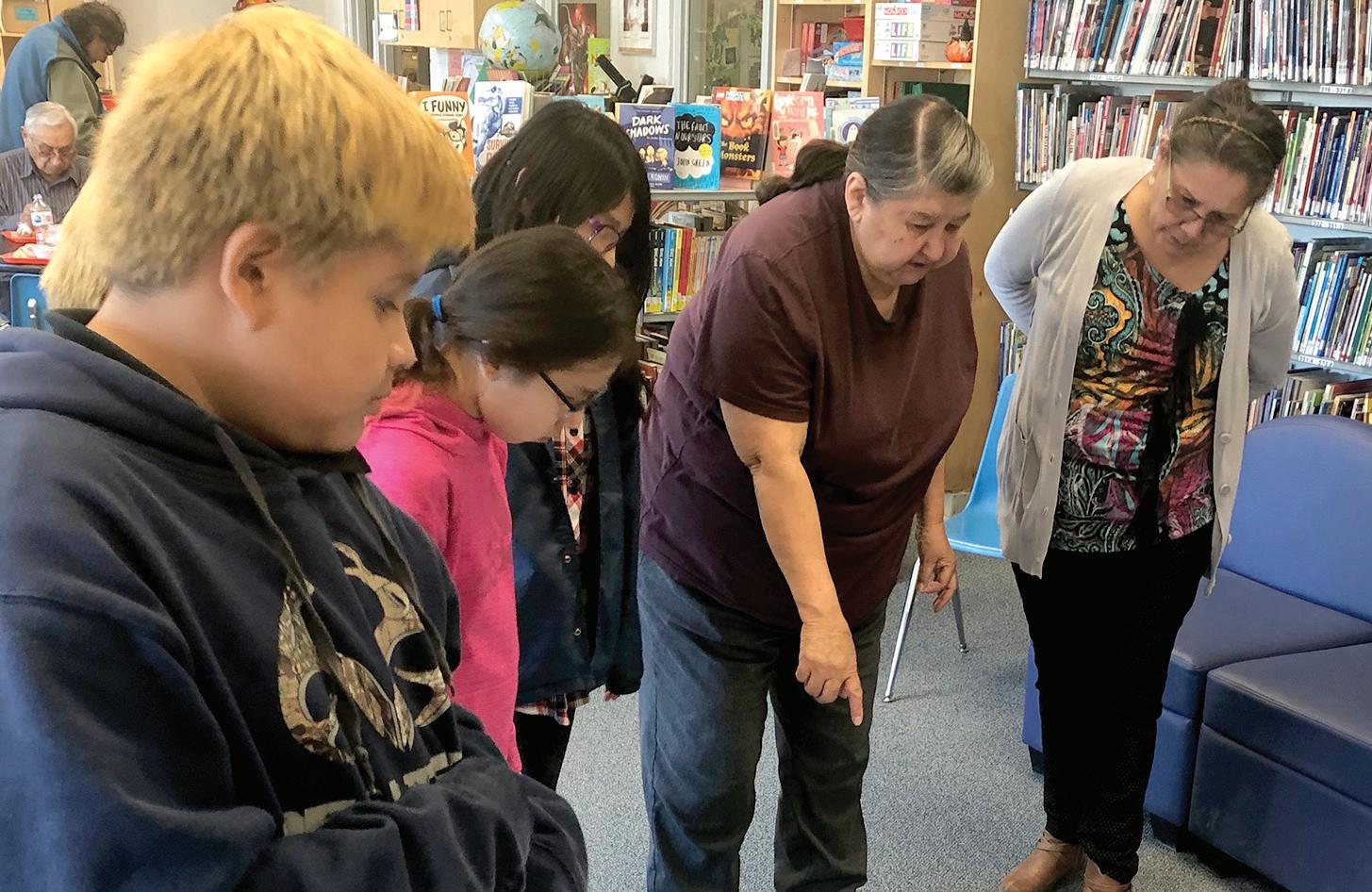

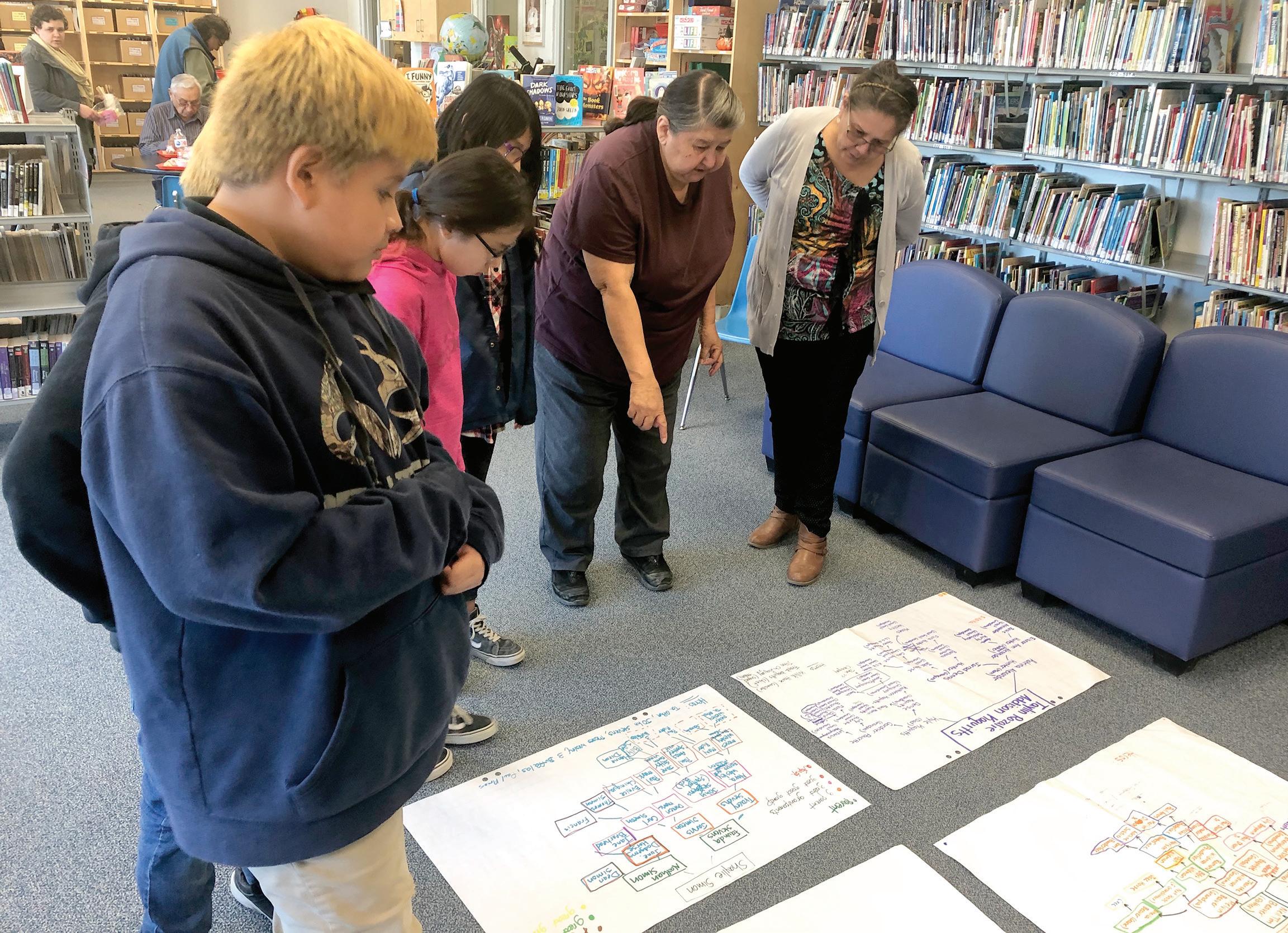

At the next meeting with the co-design team, the four Elders brought an additional four Elders to the meeting. The teacher and her Galileo mentor brought the family trees to that meeting to show the Elders in hopes that the Elders would review the family trees. However, the Elders were clear: the children needed to be present when they reviewed the family trees. This new information necessitated a change to the design. The eight Elders would be invited into the classroom, where the children would share their family trees. What

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 13

PHOTO: AMY PARK, GALILEO EDUCATIONAL NETWORK

became evident to the entire co-design team, is that the initial four Elders recognized their own need to bring in more Elders to help fill in the gaps in students’ family trees. In addition, the Elders were not interested in merely viewing the family trees that students had created without the students; rather, they wanted the students to hear the stories of their ancestors from the Elders themselves.

The eight Elders began their teachings with the children with an opening prayer and a sharing circle in which the students were encouraged to speak their names clearly and proudly. The Elders and the children immersed themselves in the important work of tracing ancestral lineages. Speaking with one child, an Elder stated, “You are a descendent of great warriors. Your name comes from your ancestors.” In another corner of the room, an Elder looked at a child and said, “Your great, great, great grandfather was a powerful Shaman. People came to see him from far away because he had supernatural powers. He could heal people.” Where one Elder’s recollection ended, another one carefully filled in the gaps. The conversations and collaboration between Elders and students were a powerful sight to witness. The Elders circled the room going from one student to another, from one family tree to another, helping each other remember when there was a gap that needed to be filled or confirming each other’s recollections. Throughout the day’s activity, the family trees that initially seemed so small were now expanding beyond the constraints of the chart paper. Notes were added to one family tree to show how this

student’s lineage continued onto another student’s chart. Elders continually reinforced to the students, “You are family. Get to know each other. Now you need to look out for each other, because that’s what families do.”

We did not end there. The now 11-person co-design team invited Christine Wignall, the artist whose exhibition inspired this project, to join the initiative. While sculpting busts with nine- and ten-yearolds was a bit daunting to her at first, she willingly agreed to accept the challenge. The local Canmore community arts centre, artsPlace, agreed to open its doors to Christine and the children. The children had all selected one of their ancestors as their hero, had learned the stories of their ancestral hero from the Elders, and now they were ready to sculpt a bust of their hero to fill in the missing people from the original 100-head exhibit. The local news media (Lucero, 2019) featured the work of the students, and the public was invited to attend

14 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

PHOTOS: SHARON FRIESEN, GALILEO EDUCATIONAL NETWORK

Watch the video

The Galileo Educational Network created a short video documenting this project: Stoney Nakoda Heroes Project https://vimeo.com/333252310/5f9b208c95

the exhibition of their hero sculptures as part of the National Indigenous Peoples Day celebrations.

I had more than 20 years of experience in research-practice partnerships with teachers and school leaders. However, with this project, I and my colleagues at Galileo had the opportunity to learn how to weave what we knew with the wisdom of the Elders who participated with us to co-design classroom learning for children. It was our opportunity to engage in a process of unlearning – unlearning professional learning and research, and unlearning classroom and curriculum approaches and processes tethered to “colonial logics of relationship denial” (Donald, 2022, para. 8).

What began fairly naively as a school project to connect children with their community grew and surpassed any of our expectations. The Elders brought us into relationship with each other, the children’s ancestors, and historical events that not only shaped this region, but also so many regions across Canada. One of the Elders commented, “Not only was this experience incredibly beneficial for the children,

but for the Elders as well.” A number of the Elders noted that as they helped each other remember, they were reminded of stories, family members, and cultural histories that have not been spoken of in some time. As one Elder stated, “This is good for our community.” I would add, this was so good for me as well. I witnessed the ways in which even the best intended curriculum approaches often remain tethered to colonial logics. Opening myself to the teachings of the Elders and being in the presence of their work with the children showed me how to begin the work of unlearning in a good way – a way that honours and respects. Perhaps my unlearning is best captured by the words of an Elder who was such an integral part of this entire project, Elder Skyes Powderface. Elder Powderface has now passed on to the spirit world, but I am left with his words: “This is what reconciliation is all about.” EC

REFERENCES

Bødker, K., Pors, J. K., & Simonsen, J. (2004). Implementation of web-based information systems in distributed organizations: A change management approach. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 16(1).

https://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol16/iss1/4

Donald, D. (2022). A curriculum for educating differently: Unlearning colonialism and renewing kinship relations. Education Canada, 62(2).

www.edcan.ca/articles/a-curriculum-for-educating-differently Heron, J. (1996). Quality as primacy of the practical. Qualitative Inquiry, 2(1), 41–56. doi.org/10.1177/107780049600200107

Lucero, K. (2019, June 20). Stoney Nakoda heroes: Uncovering lost family history with guidance of elders. RMOTODAY.com.

www.rmotoday.com/mountain-guide/stoney-nakoda-heroes-uncovering-lostfamily-history-with-guidance-of-elders-1574369

Szuskiel, D. (n.d.) Whyte Museum 50th anniversary. https://whererockies.com/2019/05/10/whyte-museum-50th-anniversary

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 15

Critical Incidents in Educational Leadership

An opportunity for professional (un)learning

BY MÉLISSA VILLELLA

IN 2021, A WHITE, French-language Catholic school principal was removed from his school two years after wearing a Black student’s shaved-off hair as a wig during a cancer fundraiser, and again for Halloween months later – but only once these two occurrences were reported on social media by Black Lives Matter London (CBC News, 2021). Since school improvement is unlikely to be successful without effective educational leadership (Rodgers et al., 2016), it is imperative for leaders to examine the verbal, behavioural or environmental indignities they – intentionally or unintentionally – communicate toward, or about, racialized persons through racial microaggressions. A racial microaggression is a brief, everyday indignity that (re)produces racial slights or insults toward Black students, principals, or teachers (Brown, 2019; Frank et al., 2021; Sue et al., 2007.)

What do we know about systemic anti-Black racism in French-language education? A limited number of studies have explored systemic anti-Black racism within minoritized French-language education in Canada (Ibrahim, 2014; Jean-Pierre, 2020; Villella, 2021). These studies pro-

vide insight into how systemic anti-Black racism manifests itself within this context. For example, Schroeter and James (2015) found that Black francophone immigrant students felt that white school staff, including a school principal, give white immigrant students more help to reach their career goals. Madibbo (2021) identifies three conditions that illustrate and/or enable systemic anti-Black racism within this context:

• A lack of equitable representation of Black people within la francophonie

• the rejection of multiculturalism

• a “franco-centric” approach to the social construction of race and racism.

Examining critical incidents

My PhD thesis (2021) details systemic anti-Black racism critical incidents in educational leadership within francophone Ontario and their impact on Black and francophone students, teachers, families, and community partners. This narrative case study explored the intercultural and anti-racist competency of educational system lead-

16 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

Mélissa Villella, PhD, is a white, francophone Professor of School Administration at Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue, as well as Director of the Educational Institution Management Diploma program.

DECOLONIZING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

PHOTO: ISTOCK

ers through critical incidents in leadership. A system leader, such as a school principal, is an individual who also represents a professional organization, and creates and or implements a society’s policies, procedures, and regulations (Villella, 2021). A critical incident is a positive or negative experience that affects one’s leadership by confirming it, by changing it, or by shattering it (Sider et al., 2017; Yamamoto et al., 2014).

Nine educational and system leaders, most of whom were, or had recently been, school principals, completed three semi-structured interviews and a survey. Data analysis revealed that almost all the critical incidents mentioned by the nine participants as being intercultural in nature centred around Black school community members, and mostly Black boys and men, including a Catholic priest. While their survey responses suggested that most of the nine participants’ intercultural competency was well developed, the way in which they dealt with critical incidents involving Black students, staff, families, and community members indicated that their anti-racist competency needs further development. In the case of intercultural and anti-racist competencies, little to no university courses or workshop training was reported by the participants; they mostly trained themselves through international volunteer work, reading, and personal experi-

ence sharing. As such, they mostly did informal training (Villella, 2021). It should therefore not come as a surprise that critical incidents revealing systemic anti-Black racism and racial microaggressions manifested themselves in the participants’ leadership.

What the data reveals:

Multiple racial microaggressions

Below, I present and analyze four systemic anti-Black racism critical incidents (translation by the author) through Brown’s (2019) racial microaggression framework of pathologizing, cultural insensitivity, persistent devaluation of Black teachers’ competency, second-class citizenship in schools, and the myth of meritocracy. Brown indicates that such microaggressions are not only steeped in anti-Black ideology, but they are also documented reasons why Black teachers1 leave the teaching profession.

1. Some Black principals are experiencing racism from their fellow white colleagues. A self-identifying Black male school principal explains how systemic anti-Black racism still persists in the staff room of a school where he used to work:

“I had a meeting with the principal. So, I think that there is a

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 17

former colleague of mine, I will go and see him… He says, ‘[Hassan], you’re in the white people’s staff room with me here.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘You don’t see? The immigrant table is over there.’ So, I have to tell you that even when I was there, there were two staff rooms.”

In this school, Black teachers (and especially Black immigrant teachers) are the targets of systemic anti-Black racism in the staff room in the form of second-class status (Brown, 2019; Frank et al., 2021).

2. A self-identifying Métis female educational system leader details the behaviour that some Black teachers are subjected to in the classroom:

“[Students] were telling him off, I mean, plus [he] spoke with a rather pronounced accent. This was probably one of the first Black people they saw in person… it was one of the first classes that he had in Canada, because he had just been substituting in Montreal, if I recall correctly… In the corner at the back of the class [were] four young men who had fun putting him down: ‘Sir, I don’t understand anything, I don’t understand when you talk. It makes no sense.’”

In this example of racial microaggressions toward a Black teacher, there is a persistent devaluation of his capabilities for teaching (Brown, 2019; Frank et al., 2021) by the students and as well as by the participant, but there is also racialized linguicism

(Madibbo, 2021), i.e. a combined linguistic and racial discrimination toward a Black person who is also a recent immigrant.

3. Some principals are removing Black francophone teachers from the classroom when a disagreement arises or their teaching practices differ from the school’s usual practices. A self-identifying white, male, Canadian-born French-language school principal describes how he responds to such incidents involving Black immigrant teachers:

“They’re unable to integrate… and that, that’s despite trying to coach them. We tried… the traditionalism is too entrenched in their practices… you get into a conflict, and that’s where there are layoffs, where there are unsatisfactory assessments.”

Here, we can observe another racial microaggression whereby a white administrator pathologizes Black teachers through his fixed vision of competency based on conformity to French-language education that can be traced back to the white ideologies historically normalized within educational policies and practices.

4. Some hiring teams are not always examining Black teachers’ competency objectively at the onset. One self-identifying white, female, Canadian-born French-language school principal noted her critical incident:

“I’ve done interviews, and the questions we were asking, we already had an idea of what we wanted as answers… A few times,

18 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

I realized that we weren’t talking about the [Black] person’s competency. Someone said, “Well, the person said this or that… and they may hit the child to discipline them.”

In this example, the racial microaggressions manifest themselves as a form of pathologizing (Brown, 2019 ; Frank et al., 2021).

5. Finally, some teachers are not always open to seeing beyond dominant nationality and cultural norms in terms of pedagogical milestones.

“I’m doing a follow-up evaluation with… a teenager from mainland Africa… who had had very large gaps in schooling… and I had concerns about the level of work he is being given [by his classroom teacher]. Because sometimes… if a student does not know how to read, there is a tendency to pick up materials for learning to read in the younger ones… but it’s not cognitively stimulating… because I have a 15–16-year-old [male] who… is practising bobo -baba [sounds]. But this is a young person who is being treated

like a… student who has a disability.”

Here, one can identify that this Black student is experiencing microaggressions in the form of micro-invalidations regarding his reading needs that are grounded in second-class citizenship, cultural insensitivity, and persistent devaluation of competency (Brown, 2019 ; Frank et al., 2021; Sue et al., 2007).

Although these are only some of the critical incidents of anti-Black systemic racism within educational leadership that emerged from my study, they are informational vignettes representing a snapshot of how systemic anti-Black racism (re)produces itself about and toward Black school-community members within French-language schooling in Ontario.

How can studying critical incidents help us (un)learn systemic anti-Black racism?

Yamamoto et al. (2014) explain that the stories we tell ourselves, share, and tell others, and once again tell ourselves regarding a critical incident is a loop allowing leaders to evaluate if they will maintain the same practices, slightly adapt their leadership, or completely change their practice in the future. As such, these critical incidents are not only formational (Sider et al., 2017), they are also informational (Villella, 2021), revealing the professional (un)learning that is required to combat systemic anti-Black racism. The question that now emerges is: what can French-language educational system leaders, such as

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 19

Studying critical incidents in relation to systemic anti-Black racism provides educational leaders the chance to change how they respond in future situations.

school principals and teacher educators, learn by examining such critical incidents?

First, it is important to remember that systemic anti-Black racism is not just an Anglo-Canadian issue. It is present in education, regardless of the language of instruction.

The analysis of critical incidents in leadership in French-language education can help school administrators, trainers, school principals, and superintendent associations, as well as French-language community organizations, understand how certain practices contribute to marginalizing Black children and adults that they serve. The ways in which leaders respond to Black teachers can contribute to the reproduction and thus persistence of systemic anti-Black racism, rather than contributing to building a more inclusive educational environment and society that mitigates against it. Either way, educational system leaders send a clear message to Black students, staff, and family members about whether or not they are valued in society.

Studying critical incidents as professional (un)learning in relation to systemic anti-Black racism provides educational leaders the chance to change how they respond in future situations, in order to be proactive and reduce harm to Black community members. As such, narrative case studies can help leaders decipher systemic anti-Black racism through professional (un)learning.

What we can do now: A few recommendations

System administrators, such as superintendents, need to support all staff who wish to develop preventative strategies to decrease the

likelihood of systemic anti-Black racism from being (re)produced through racial microaggressions. The provincial government and school boards/districts need to require measures that track systemic anti-Black racism incidents, and to transparently report on them. Developing a mixed approach of both qualitative and quantitative data collection is important for better understanding of the underlying issues, which should not be reduced to a case of immigration status or mother tongue language as central identifiers.

Finally, initial and continual training opportunities need to be allocated to educational system leaders at all levels who wish to be trained, or to train their school teams, about racism and anti-racism. Specific areas of needed training include: culturally sustaining pedagogy and leadership, race-based data analysis, and questioning school board pedagogical and discipline policies regarding students as well as hiring practices related to staff. Such training requires that resources not only be developed in French, but also that critical incidents of systemic anti-Black racism are based on examples collected within

20 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

These incidents should cause school and system leaders to reassess how to better build relationships with each Black student, staff member, and community partner.

francophone education systems.

Although some educational leaders may be more aware of systemic anti-Black racism incidents related to their leadership, such critical incidents still exist and persist. That said, we should not be dissuaded nor discouraged from developing inclusive and equitable French-language education systems. Instead, these incidents should cause educational school and system leaders to reassess how to better build relationships with each Black student, staff member, and community partner, and how to go beyond the deficit thinking and stereotypes that lead to racial microaggressions. That process begins and continues with fully participating and engaging in decolonizing professional (un)learning. The knowledge then needs to be applied within local communities to create more equitable and inclusive spaces of belonging for Black students and staff, and for those from other equity-deserving groups within la francophonie. Not only do Black students need Black educators, so does the rest of Canadian society. Inclusion is, after all, meant for each and every one. EC

NOTE

1 While the Brown (2019) study focused on Black teachers, Frank et al.’s (2021) study focused on Black math teachers specifically.

REFERENCES

Brown, E. (2019). African American teachers’ experiences with racial microaggressions. Educational Studies, 55(2), 180–196. doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2018.1500914

CBC News. (2021, May 31). London, Ont., principal removed for wearing Black student’s hair like a wig says he’s sorry, ‘ashamed.’ CBC News. www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/luc-chartrand-black-student-wigapology-1.6047068

Ibrahim, A. (2014). The rhizome of Blackness. A critical ethnography of hip-hop culture, language, identity and the politics of becoming. Peter Lang Publishing.

Jean-Pierre, J. (2020). L’appartenance entrecroisée à l’héritage historique et au pluralisme contemporain chez des étudiants franco-ontariens. Minorités linguistiques et société/Linguistic Minorities and Society (13), 3–25. doi.org/10.7202/1070388ar

Frank, T. J., Powell, M. G., & View, J. L. (2021). Exploring racialized factors to understand why Black mathematics teachers consider leaving the profession. Educational Researcher. doi.org/10.3102/0013189X21994498

Madibbo, A. (2021). Blackness and la Francophonie: Anti-Black racism, linguicism and the construction and negotiation of multiple minority identities. Les Presses de l’Université Laval.

Rodgers, W. T., Hauserman, C. P, & Skytt, J. (2016). Using cognitive coaching to build school leadership capacity: A case study in Alberta. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue canadienne de l’éducation, 39(3). www.jstor.org/stable/canajeducrevucan.39.3.03

Schroeter, S. & James, C. (2015). “We’re here because we’re black”: The schooling experiences of French-speaking African-Canadian students with refugee backgrounds. Race, ethnicity and education, 18(1), 20–39. doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.885419

Sider, S., Maich, K., & Morvan, J. (2017). School principals and students with special education needs: Leading inclusive schools. Canadian Journal of Education, 40(2). http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2417

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M. et al. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life. American Psychologist, May-June. https://gim.uw.edu/sites/gim.uw.edu/files/fdp/Microagressions%20File.pdf

Villella, M. (2021). Piti, piti, zwazo fè niche li (Petit à petit, l’oiseau fait son nid) : le développement d’une compétence interculturelle et antiraciste de neuf leaders éducatifs et systémiques d’expression française de l’Ontario, formateurs bénévoles en Ayiti. Unpublished thesis. University of Ottawa. https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/42728

Yamamoto, J. K., Gardiner, M. E., & Tenuto, P. L. (2014). Emotion in leadership: Secondary school administrators’ perceptions of critical incidents. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(2), 165–183.

Suggested Reading

For the most effective self-study experience, read in the order presented.

CANADIAN STATISTICS

n Canadian Race Relations Foundation & Environics Institute for Survey Research. (2021). Race relations in Canada 2021: A survey of Canadian public opinion and experience. (The link leads to an introductory page about the survey, with links to the final report and other study documents.)

www.environicsinstitute.org/projects/project-details/ race-relations-in-canada-2021

n Statistics Canada. (2019). Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview. www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657x2019002-eng.htm

n Statistics Canada. (2022). Black History Month… by the numbers. www.statcan.gc.ca/en/dai/smr08/2020/smr08_248-1

BLACKNESS

n Ibrahim, A. (2014). The rhizome of Blackness. A critical ethnography of hip-hop culture, language, identity and the politics of becoming. Peter Lang Publishing.

n Madibbo, A. (2021). Blackness and la Francophonie. Anti-Black racism, linguicism and the construction and negotiation of multiple minority Identities. Les Presses de l’Université Laval.

BLACK FRANCOPHONE EXPERIENCE

n Pierre-René, M. C. (2019). Hey “G!” An examination of how Black English language learning high school students experience the intersection of race and second language education. [Doctoral thesis, University of Ottawa]. uO Research. https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/39108

CRITICAL RACE THEORY

n Thésée, G., & Carr, P. R. (2016). Triple whammy and a fragile minority within a fragile majority: School, family and society, and the education of Black, francophone youth in Montréal. African Canadian youth, postcoloniality, and the symbolic violence of language in a French language high school in Ontario. In A. A. Abdi & A. Ibrahim, (Eds.), The education of African-Canadian children (pp. 131–144). McGillQueens University Press.

Additional French-language resources are listed in the French version of this article: https://www.edcan.ca/magazine/?lang=fr

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 21

Welcoming Indigenous Ways of Knowing

Decolonizing and building relationships through education change networks

Leyton Schnellert, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the University of British Columbia (UBC) Department of Curriculum & Pedagogy, and Pedagogy & Participation research cluster lead in UBC’s Institute for Community Engaged Research.

Sara Florence Davidson, PhD, is a Haida/Settler Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University.

Nikki Yee, PhD, is a settler scholar of Chinese and Mennonite ancestry in the Teacher Education Department at the University of the Fraser Valley.

Bonny-Lynn Donovan is a Métis PhD student in Community Engagement, Social Change, and Equity at UBC Okanagan.

BY LEYTON SCHNELLERT, SARA FLORENCE DAVIDSON, NIKKI YEE, AND BONNY-LYNN DONOVAN

HOW CAN EDUCATION CHANGE NETWORKS (ECNs) support Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators and community members to create relationships and ultimately better meet the needs of Indigenous (and all) learners? We have been investigating this question as part of an emerging field of research concerned with developing decolonizing education practices in relationship with Indigenous communities. Overall, we have found that ECNs based on relationality within ethical spaces of engagement have the greatest potential for positive change. Specifically, our research has found that ECNs are most effective when they keep the focus of the learning explicit, acknowledge local protocols, make space to engage with local Indigenous knowledge and Knowledge Keepers, and identify and address structural barriers.

Colonialism in Canadian education

We recognize that colonialism continues to shape educational systems and student experiences across Canada (e.g. Pidgeon, 2022). For example, many educators may communicate lower expectations for Indigenous students as opposed to the other students in their classes (Yee, 2021). Colonial learning contexts can be traumatizing for Indigenous and other historically marginalized students, families, and communities, and deeply troubling for teachers and administrators struggling to meet the needs of Indigenous (and all) students (Yee, 2021). Educators often do not know how to begin a process of transformation or what changes to make (Donald, 2009). At the same time, Indigenous communities may be eager to work with and influence Western educational systems, but may not have opportunities to participate

in educational change (Yee, 2021).

Decolonizing possibilities in education

We propose that to move away from colonial practices, educators can begin by exploring decolonizing possibilities. Niigan Sinclair (Kirk & Lam, 2020) suggests that decolonization involves dismantling racist and oppressive ideas. It requires us to reflect on our beliefs and assumptions and how they are connected to the various forms of privilege we experience (e.g. cultural, socioeconomic, gender, etc.). In education, decolonization involves disrupting classroom and school practices that maintain power imbalances. However, it is vital that educators do not stop there. As Graham Smith (2000) suggests, it is critical to reimagine what is possible and what should be implemented, in relationship with Indigenous Peoples. Gaudry and Lorenz (2018) talk about Indigenization as including and advancing the perspectives and intellectual priorities of Indigenous communities to support Indigenous cultural resurgence. When we collaborate with Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and educators, we can create more inclusive learning communities for Indigenous (and all) learners.

To explore decolonizing possibilities in education, researchers, school districts, and Indigenous communities can come together in ECNs to de-centre dominant ways of knowing and reimagine teaching and student success. ECNs are learning networks that engage diverse teachers, administrators, community members, parents, and students as collaborative inquirers and co-constructors of equity-oriented teaching practices (Cochran-Smith, 2015; Schnellert et al., 2022). Collaboration between edu-

22 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

DECOLONIZING PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

cators and Indigenous community partners within ECNs offers tremendous potential for co-creating teaching practices that foreground local Indigenous ways of knowing and being, and for supporting system and practice change.

Education change networks in action

The Welcoming Indigenous Ways of Knowing ECN, where Indigenous and non-Indigenous teachers, school administrators, academics, and school district personnel work together with syilx Elders and Knowledge Keepers, provides an example of how ECNs can support educational change (Schnellert et al., 2022). Five times during the school year, on professional development days, this B.C. ECN meets as one large group to experience land-based teachings from local Indigenous Knowledge Keepers. Then in the afternoon, educators complement this learning by participating in smaller inquiry groups (6–15 educators) to plan and implement their new understandings in classroom practice (Schnellert et al., 2022). In this way, ECNs can support disrupting and transforming classroom teaching and learning, thus taking up Principle of Reconciliation 4 that requires engagement in “constructive action on addressing the ongoing legacies of colonialism that have had destructive impacts on Aboriginal Peoples’ educa-

tion” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015, p. 3).

Ethical relationality

In our work we have found that efforts to decolonize are best realized when they are shaped by ethical relationality. Nêhiyaw (or Cree) scholar Dwayne Donald explains, “Ethical relationality is an ecological understanding of human relationality that does not deny difference, but rather seeks to more deeply understand how our different histories and experiences position us in relation to each other” (2009, p. 6). This understanding means that members of the ECN embrace their Indigenous or non-Indigenous positionality, and vulnerably speak about their own understandings, experiences, and the learning they feel they need. Within ECNs, this kind of approach allows us to open decolonizing possibilities through critique and the recognition of diverse ways of being and knowing. Building from a stance of ethical relationality helps create a solid foundation for the work to be done in ECNs, but can only unfold in an ethical space of engagement.

Ethical spaces of engagement

Even though ethical relationality requires vulnerability, non-Indigenous ECN members may fear being called out for their role in colonialism and Indigenous ECN members may fear continued colonial violence. As such, creating an ethical space of engagement is key. According to Ermine (2007), when Indigenous and Western knowledge systems come together, a space to “step out of our allegiances” (p. 202) can emerge. This ethical space of engagement invites us to share assumptions, values, and interests we each hold, while creating opportunities to learn (and unlearn) more deeply and authentically. Members can co-construct this space by discussing how they understand respect, for example, or how they might centre Indigenous perspectives as part of their decolonizing process. Creating an ethical space means taking a holistic stance – considering and attending to our personal thoughts, feelings, and actions and their often unintended impact on others. If members build this space together, agreeing on processes for sharing, decolonization becomes more relevant and responsive to those in the room. To summarize, ECNs can be structured as an ethical space to support Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators and community partners to collaborate in disrupting and transforming classroom teaching and learning by valuing and welcoming Indigenous ways of knowing.

Lessons learned

LEYTON SCHNELLERT

Our collaborative research with ECNs offers insights that can support similar efforts in other Canadian contexts. In the next section we reflect on a few lessons we have learned through the ECN described above, but also from our diverse experiences working in this area over the last decade.

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 23

PHOTO:

Land-based learning with Knowledge Keeper Anona Kampe.

1. Make the focus of the learning explicit Central to exploring decolonizing possibilities is asking educators to interrogate their own identities and their role as educators, deconstruct ways that classrooms and schools reproduce privilege, and reimagine their practice to welcome Indigenous ways of knowing. We have found that explicit attention to these goals and activities is important. Educators attend professional development opportunities – and networks – with the assumption that they will receive strategies to take away and use in their contexts. While this may be part of the work of ECNs, decolonizing processes first and foremost require educators to examine their own privilege through multiple lenses. To reference Donald’s work (2022), surfacing and addressing unconscious bias within ourselves and our teaching involves unlearning. This unlearning is uncomfortable, but ECN members report that it is also powerful; educators need opportunities to encounter colonial truths, explore their identities, commit to a co-constructed vision of education, and then work to align their practice accordingly. Participants in one ECN shared that they are more confident in identifying and disrupting teaching practices that reproduce privilege as a result of these kinds of experiences within the ECN (Schnellert et al., 2022).

2. Create protocols that make space

Also key has been the introduction of protocols that make space for Indigenous and historically marginalized participants to share their experiences and insights within the larger work of the ECN. Circle protocols, where each participant has an opportunity to share and other ECN members are invited to listen without judgment, have been important. Other strategies include building in time for IBPOC

educators and participants to meet (caucus) as a separate group, and ensuring that Knowledge Keepers are introduced and thanked with appropriate recognition of their role, the knowledge they bring, and the responsibilities they carry. Sometimes we demonstrate respect and reciprocity through food. When working with Indigenous communities, it is also important to clarify how knowledge can be shared. Some knowledge is sacred and not to be shared freely. It is key to be responsive to and respectful of local protocols as a way of centring Indigenous perspectives.

3. Engage with local Indigenous knowledges and Knowledge Keepers

One of the most impactful aspects of ECNs has been the opportunity to engage with local knowledge and Knowledge Keepers. ECN members in one study expressed appreciation for local Indigenous Knowledge Keepers, the impact of engaging with foundational ideas over several convenings, and opportunities to work with Knowledge Keepers to apply what they were learning in their classrooms with students (Schnellert et al., 2022). For these ECN members, a particularly transformative aspect of the work with Knowledge Keepers involved land-based learning. Educators said that they engaged more deeply with local Indigenous stories and concepts when ECN meetings happened on the land (Schnellert et al., 2022).

4. Identify and address structural factors and barriers

From our work with ECNs, we have identified several factors related to systems-level educational change that need to be identified and addressed in order to open decolonizing possibilities within education systems. Lack of knowledge has consistently been surfaced as

24 EDUCATION CANADA • January 2023 | EdCan Network www.edcan.ca/magazine

a significant concern (e.g., Schnellert et al., 2022; Yee, 2021). Most educators were not educated with a decolonizing or Indigenizing lens as students or in teacher education. Educators valued learning about how colonial history has influenced what is taught and how we teach in schools. Using this lens, we can disrupt perceptions of neutrality in the school system. Another key structural factor to consider is pervasive anti-Indigenous racism – in particular, the racism of low expectations (Auditor General of British Columbia, 2015). Increased awareness has led teachers to engage with Indigenous learners from a strength-based perspective, to mentor and encourage Indigenous students, and to explicitly address comments that perpetuate stereotypes (Schnellert et al., 2022).

EDUCATION CHANGE NETWORKS are a strong tool for opening decolonizing possibilities across the educational system and within schools. Specifically, we explore decolonizing and Indigenizing possibilities as we work in ethical relationality across difference, in ethical spaces of engagement. In our collective experiences, we have found it important to keep the focus of the learning explicit, acknowledge local protocols and make space, engage with local Indigenous knowledge and Knowledge Keepers, and identify and address structural barriers. In this way, educators can come together to more effectively open decolonizing possibilities within themselves, and for the next generations in our classes. EC

REFERENCES

Auditor General of British Columbia. (2015). An audit of the education of Aboriginal students in the B.C. public school system. Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia.

www.bcauditor.com/sites/default/files/publications/reports/OAGBC%20

Aboriginal%20Education%20Report_FINAL.pdf

Cochran-Smith, M. (2015). Teacher communities for equity, Kappa Delta Pi Record, 51(3), 109–113. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2015.1056659

Donald, D. (2009). Forts, curriculum, and Indigenous Métissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts. First Nations Perspectives, 2(1), 1–24.

Donald, D. (2022, September 19). A curriculum for educating differently. Education Canada, 20–24. www.edcan.ca/articles/a-curriculum-for-educating-differently Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 193–203. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/article/view/27669 Gaudry, A., & Lorenz, D. (2018). Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: Navigating the different visions for indigenizing the Canadian academy. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(3), 218–227. doi.org/ 10.1177/1177180118785382

Kirk, J., & Lam, M. (Hosts). (2020, October 8). Indigenizing education (No. 26) [Audio podcast episode]. In Leaning in and Speaking Out. BU Cares Research Centre. www.bucares.ca/podcast/n5c2968wkajahe2

Pidgeon, M. (2022). Indigenous resiliency, renewal, and resurgence in decolonizing Canadian higher education. In S. D. Styres & A. Kempf (Eds.), Troubling truth and reconciliation in Canadian education: Critical perspectives (pp. 15–37). University of Alberta Press.

Schnellert, L., Davidson, S. F., & Donovan, B. (2022). Working towards relational accountability in education change networks through local indigenous ways of knowing and being, Cogent Education, 9(1), 2098614. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2098614

Smith, G. H. (2000). Protecting and respecting Indigenous knowledge. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 209–224). UBC Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_ Action_English2.pdf

Yee, N. L. (2021). Review of inclusive and special education: Final report. Department of Education for Yukon Territory. https://yukon.ca/en/review-inclusive-and-special-education-yukon-final-report

www.edcan.ca/magazine EdCan Network | January 2023 • EDUCATION CANADA 25

Equity in Teaching and Learning

Living, being, doing

Karen Ragoonaden is the Associate Dean of Teacher Education in the Faculty of Education, University of British Columbia. She is an award-winning educator whose research focuses on culturally sustainable pedagogy and antiracist education.

BY KAREN RAGOONADEN