DNT EXTRA | August-September 2019

Our Neighborhoods

LET’SG ET DOWN TO BUSINESS info@apexg etsbusiness.com 218.740.3667 APEXge tsbusiness.com Competitive advantages include: •Rich Natural Resources •Established Infrastructure •Available Real Estate •A DedicatedWorkforce •Excellent Quality of Life APEX drives business development in northeast Minnesota and northwest Wisconsin. Build Expand Grow Agile and connected, our experienced team aligns with the needs of your business.

Rick Lubbers

Duluthians take great pride in where they live. They also are quick to proudly note which Duluth neighborhood they call home. And if the Duluth News Tribune happens to incorrectly identify a Duluth neighborhood in a news, sports or feature story? Our phones ring off the hook and our email inboxes flood. We are very quickly corrected.

You’re passionate about your Duluth neighborhoods … from Fond du Lac to North Shore (and every neighborhood in between).

For this edition of DNT Extra, we’ve decided to focus on Duluth neighborhoods — their history, their future, the people who reside in them. Even a few neighborhoods that don’t exist anymore.

We hope you’ll find this section informative and interesting. Our next edition will be published in October. If you have any ideas for upcoming issues of DNT Extra, please let us know.

Thanks again for reading the News Tribune and DNT Extra.

Rick Lubbers is the executive editor of the Duluth News Tribune. Contact him at (218) 723-5301 or rlubbers@duluthnews.com.

COVER:

The western neighborhoods of Duluth seen at sunrise from Skyline Parkway. (Clint Austin / caustin@duluthnews.com)

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 3

4 First residents

Long before Europeans, tribes called Northland home

6 From many towns, one Duluth

a little rustic’ Lincoln Park

of change

Lost to history

26 ‘Beautiful and

a place

44

Fond du Lac

Gary-New Duluth

Morgan Park

Smithville

Riverside

Norton Park • Bayview Heights • Fairmount

Irving • Cody

Spirit Valley • Denfeld • Piedmont Heights • Lincoln Park • Duluth Heights • Central Hillside • Downtown • Park Point • East Hillside • Kenwood

Endion

Not all Duluth neighborhoods survived to modern times 48 Neighborhoods shape Superior Neighborhoods •

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Chester Park-UMD • Hunters Park • Congdon Park

• Woodland

• Morley Heights

• Lakeside-Lester Park

• North Shore

Page design for this section by Renae Ronquist. Editing by Peter Baumann and Rick Lubbers. Assistance with photos from Clint Austin, Tyler Schank, Steve Kuchera, Jed Carlson and Ellen Schmidt and assistance with graphics from Gary Meader. Advertising Account Executives: Ali Comnick and Barbie Into

First residents

By Kelly Busche kbusche@duluthnews.com

By Kelly Busche kbusche@duluthnews.com

4 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Ojibwe residents and white visitors to a village or camp on Minnesota Point in the 1800s. Courtesy of the University of Minnesota Duluth Kathryn A. Martin Library Archives and Special Collections.

Long before Europeans, tribes called Northland home

The very first people on the land that is today called Duluth were here during the “Paleo Indian” phase, which lasted from approximately 11200 to 7500 B.C. Paleo-Indian people entered the area after the glaciers retreated around 14,000 years ago. They were known for large, leaf-shaped stone spear tips and knives. During their time, Lake Superior was much larger — extending up past where Skyline Parkway is today — and they lived along its shores.

Next came the Archaic period that ran until approximately 500 B.C. Limited information is available about this period, as Lake Superior had much lower water levels. As the lake eventually grew, it covered many remnants of the former residents.

The Woodland period comes next. The Woodland people, marked by a period from 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1750, stayed at their villages and campsites for longer periods of time, as reliable food sources were available nearby. They ate fish, mammals and wild rice, among other things.

It’s not exactly known when other tribes, including the Dakota and Anishinaabe tribes, migrated to the area. But they had their first interaction with French explorers in the 1600s. Many of their initial exchanges centered on the fur trade, with Native Americans trading furs for guns, knives, liquor, cloth and other manufactured goods.

Four tribes were located along the Great Lakes at the time. With a desire to promote trade in the region, French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Luht, held a meeting among tribal leaders from the Dakota, Anishinaabe, Assiniboine and Cree tribes in 1679.

Around 100 years later, traders and settlers then began taking over the land, with the first fur post recorded by a fur trader in 1784.

Government officials then attempted to remove indigenous people from the area, resulting in the Treaty of 1854, in which the tribe ceded a significant portion of the Arrowhead region, and numerous reservations, including the Fond du Lac Reservation, were established.

A notable figure in the Anishinaabe community was Chief Buffalo, who signed the 1854 treaty. He was allowed to select one tract of land for himself and chose a section that now includes downtown Duluth, Lincoln Park, Canal Park and Central Hillside, but after his death in 1855 “others misrepresented and sold his claim,” according to the Fond du Lac Band.

As the place long known as Onigamissing (little portage) became Duluth with new residents arriving in droves, the federal government was going to war with tribes around the country and over the

next century implemented policies of removal, mandatory boarding schools and termination (forced assimilation). The effects of those and other policies were and are still felt here and throughout the nation.

An ethnographic study of the indigenous contributions to Duluth undertaken by the city’s Indigenous Commission showed a widespread “belief among indigenous people living in Duluth that their presence and their history have not been visible to the wider population of the city and to visitors. Aside from highly public disputes about the revenues from the Fond du Luth casino, Native people do not believe that their contributions to the city, either in the past or today, have been appreciated.”

Attempts at reconciliation have been made, as seen at the renaming of Duluth’s Lake Place Park to Gichi-Ode’ Akiing this year, but the 2015 study said “a continuing problem of racism among non-Indians in Duluth would be the biggest obstacle to solving the problem of indigenous invisibility in the city.”

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 5

218.525.2223 budgetblinds.com/duluth Locally owned and operated by the Pearson Brothers Blinds - Shutters Shades Draperies Home Automation Free In-Home Consultation

Brooks Johnson contributed to this report. Information in this article is courtesy of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa’s website Duluth’s Stories and An Ethnographic Study of Indigenous Contributions to the City of Duluth.

From many towns, one Duluth

By Adelie Bergstrom abergstrom@duluthnews.com

From a handful of scrappy townsites founded in the 1850s to the industry and commerce that drove the city’s growth into the 20th century and beyond, Duluth went through booms and busts as it stretched out to the city hugging the Lake Superior shoreline that we know today.

While the name Duluth originally described a settlement at the base of today’s Park Point, the city’s true story begins in its farthest western reaches — today’s Fond du Lac neighborhood.

‘Bottom of the lake’

For many years, French voyageurs used the name Fond du Lac — “bottom of the lake” — for all of what we know as today’s Twin Ports.

French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, passed through the area in the autumn of 1679 on his way to the Dakota village at Mille Lacs Lake. His goal? To set up a fur trade agreement with the native Anishinaabe and Dakota who’d been in the region for centuries.

The Anishinaabe traveled through the region regularly, but they had no permanent settlement at the start of the 19th century. According to “Duluth’s Legacy, Vol. 1: Architecture,” published by the city in 1974, it was John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Co. that established a trading post at today’s Fond du Lac.

Fond du Lac was settled in about 1820 as the first permanent native settlement in the region. By 1835, the Rev. Edmund Franklin Ely had built a mission school here before moving to La Pointe, Wis., and then back to Superior in 1854.

6 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

First Street and Third Avenue West, about 1880.

(Photo courtesy UMD/Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections)

The fur trade dried up by the mid-1850s, and soon a new group of speculators and adventurers arrived, excited about the copper and timber resources.

In 1854, the local Anishinaabe entered into a treaty with the United States, ceding ownership of their land in Northeastern Minnesota. The Treaty of La Pointe opened up the area for non-native settlement.

The original town of Duluth was platted in 1856 and incorporated the next year. Most of the town was at the base of Minnesota (Park) Point, south of today’s Aerial Lift Bridge.

George Stuntz, who arrived in the early 1850s, built the first building on Park Point — a trading

post and later a block house and pier, according to the 1977 book “Duluth: Past to Present” by Mary Lou Germ. George Nettleton and his wife, Julia, soon followed. After the Treaty of La Pointe was reached, Nettleton built a sawmill.

Eleven townsites, including Duluth and Fond du Lac, were established by the end of the 1850s, though an economic panic in 1857 caused many to leave, and it would be another decade before the population began to recover.

The other townsites — from west to east, Oneota, Rice’s Point, Fremont, North Duluth, Middleton (later Park Point), Cowell’s Addition, Portland, Endion

Continued on page 8

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 7

and Belville (later Lakeside) — each had hopes of becoming the region’s epicenter.

Western Duluth

In 1854, Ely, now living in Superior, crossed St. Louis Bay and founded the town of Oneota. Oneota was the site of St. Louis County’s first public school, built in 1860. By 1870, Oneota had a population of 500 with two sawmills, a store, a hotel, a church, a furniture store, and eventually a shipyard, according to Germ’s book.

Oneota became part of the new town of West Duluth in 1888, growing to 6,000 residents by 1892 as the Duluth, Missabe and Northern Railway extended through the town. West Duluth itself joined Duluth in 1894.

Just downriver from West Duluth was Rice’s Point, and it was here that the first home on the Duluth side of the bay was built in 1855. The town of Rice’s Point was platted in 1858 and included all of the land back to the Point of Rocks.

Rice’s Point had hopes of becoming St. Louis County’s seat, changing its name to Port Byron in an effort to sound more sophisticated, Germ wrote, but the town lost out to Duluth, and Port Byron soon reverted to its original name.

Eventually, Rice’s Point became a center for sawmills, with as many as 13 in operation at one point, Germ said in her book. Today, Rice’s Point is still a center for much of Duluth’s industrial activity, with its grain elevators and rail tracks along the bay.

Fremont, once between Rice’s Point and Park Point, never got the chance to join the eventual city of Duluth. Before the Duluth Ship Canal was created in 1871, the harbor was filled with a number of floating islands made up of driftwood and vegetation, held in place by moorings, according to Germ’s book.

After the canal was cut, the water currents broke part of Fremont away from the shore and sent it floating into the canal. Residents attempted to chase the floating land by boat, but it disintegrated upon hitting Park Point.

Eastern Duluth

The town of Belville preceded today’s Lakeside and Lester Park, being platted in 1857. Within a few years, the town was renamed New London after broker Hugh McCulloch, who had spent a number of years in the English capital, bought the land.

According to Germ’s book, McCulloch gave the town’s streets a decidedly British flair, with names such as Pitt, Cambridge, Gladstone and the town’s main thoroughfare — London Avenue, or today’s

London Road.

George B. Sargent, an agent for wealthy financier Jay Cooke, bought the land from McCulloch and organized the Lakeside-London and Lester Park additions in 1886-87. The town of Lakeside joined the city of Duluth on Jan. 1, 1893.

Closer in, Endion’s suburban lots were platted in 1856 and grew from land claimed by the Hon. William Wallace Kingsbury, delegate to the Minnesota Territorial House of Representatives and later a member of Congress. Endion was annexed to Duluth in 1870.

Portland was platted in 1857 between about Seventh and Ninth avenues east, running down to the lakefront, though it grew slightly wider over the next decade. Unlike other early settlements, Portland’s streets were laid out to align with compass directions rather than on a diagonal. When Portland was annexed into Duluth in 1870, its streets had to be realigned to fit with Duluth’s, which meant lots had to be resettled and homes had to be moved.

Washington Avenue, today just a stub of a street attached to Seventh Avenue East below First Street, is the only remnant of Portland’s original street plan. The Portland name also survives with Portland Square Park in today’s East Hillside, and with the Portland Malt Shoppe on Superior Street.

Central Duluth

In addition to the original town of Duluth, today’s central Duluth included the settlement of North Duluth, roughly analogous to today’s Central Hillside, and Cowell’s Addition, which includes most of today’s Canal Park.

Minnesota Point beyond the original town of Duluth was known as Middleton. In 1875, residents elected to maintain a separate town from Duluth and began to call the town “Park Point,” according to the Park Point Community Club.

In 1881, the village of Park Point was established. In the meantime, Duluth had lost its city status following the failure of early financier Jay Cooke’s company, on which the city had staked much of its finances, Germ wrote.

When the city regained its charter in 1887, Park Point refused to join the city until a bridge was built to join Park Point with Duluth, though with a promise from the city, it acquiesced and joined Duluth in 1889. There was much talk, but the bridge didn’t become a reality until 1905, when what would later become the Aerial Lift Bridge opened.

8 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Fond du Lac

By Tom Olsen tolsen@duluthnews.com

About 14 miles west of downtown sits Duluth’s oldest inhabited area. Fond du Lac was the site of a Chippewa settlement as far back as the 16th century.

It was here that French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut arrived in the fall of 1679, becoming the first European known to visit what is now Duluth as he sought to broker peace among warring Native American tribes, which have inhabited the western Lake Superior area for thousands for years.

French for “bottom of the lake,” Fond du Lac would soon open for fur trading, with some historical sources indicating Hudson’s Bay Co. may have established the area’s first post as early as 1692. In the early 1800s, John Jacob Aster opened an American Fur Co. post a few blocks east of what is now Chambers Grove Park.

Fond du Lac would go on to serve as the location of two treaty signings between the United States government and the Anishinaabe people, in 1826 and 1847.

By the mid-1800s, beaver pelts had fallen out of fashion, and the area’s economy turned toward logging, copper mining and brownstone quarrying. The village of Fond du Lac was formally incorporated in 1857 and annexed into the city of Duluth in 1895.

As Duluth’s westernmost

point, Fond du Lac today is a quiet, isolated neighborhood, sitting about two miles from the nearest residential area, Gary-New Duluth. In fact, the neighborhood is located closer to Carlton than it is to downtown Duluth.

Fond du Lac serves as the eastern terminus of Minnesota Highway 210, which runs through nearby Jay Cooke State Park and all the way to the North Dakota border. It’s also where

Continued on page 10-11

WELCOME TO

Look for Sue at Chester Bowl Fall Fest - Sept. 21

Lester River Rendezvous - Sept. 28

For all upcoming events and retailers, visit suebrownchapin.com

A city of contrasts and exciting discoveries, Cloquet Minnesota, offers a variety of festivals and events held throughout the year catering for all ages and interests. Spring, Summer, Fall and Winter!

For more Cloquet area information, please visit our website at www.visitcloquet.com.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 9

Cloquet Area Chamber of Commerce and Office of Tourism 225 Sunnyside Drive Cloquet, MN 55720-0426 • 218.879.1551 • 1.800.554.4350 • chamber@cloquet.com

Cloquet Office of Tourism

CLOQUET!

Here we will be featuring lodging, outdoor activities, historical sites and more!

10 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

A drawing depicts the 19th Century J.J. Astor fur post in Fond du Lac. A replica later was displayed in the neighborhood.

Photo courtesy UMD/ Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections

This photo captures a view of the Fond du Lac neighborhood in approximately 1930. Excursion boats like the Montauk, built in 1890, made daily trips along the St. Louis River. The boat landing is at 133rd Avenue West.

(Photo courtesy UMD/ Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections)

A group canoes on the St. Louis River in Fond du Lac. (2014 file / News Tribune)

Minnesota Highway 23 exits the city, continuing to far southwestern Minnesota.

Fond du Lac includes some of the city’s oldest homes and gathering spots, including Chambers Grove Park, a popular picnic space dating back to the 1870s.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 11 1208 Cloquet Ave. Cloquet • 879-4547 419 Skyline Blvd. Cloquet • 879-1501 Download our APP on google play or apple store John Gust, Pharmacist "We strive to make it convenient for you and the people you care about to live a healthy life." Visit our website at cloquet.medicineshoppe.com and learn more health information from the digital pharmacist 001832594r1 ENCORE! PERF ORMING A RTS CENTER, CLO QUET www.count yseattheater.com BOX OFFICE (218)878-0071 The County Seat Theater Co. is a 501 c3 non profit community theater. Thank You for making a tax deductible gift to the County Seat Theater! 2X3 PINE KNOT TEEN THEATER_Layout 1 07/26/2019 3:32 PM Page 1 Brittany L Olson Owner/Agent Lic# 20487431 707 Highway 33 South, Suite 11, Cloquet, MN 55720 olsoninsurancellc.com brittany@olsoninsurancellc.com Office - 218-499-8636 • Cell - 651-497-5377 Auto • Motorcycle• Boat • ATV Home • Farm • Cabin Landlord • Business Life • Umbrella • Flood The Fond du Lac neighborhood is seen in this aerial photo, along with the dam (top) that protects it from flooding by the St. Louis County River. (2005 file / News Tribune)

3931 W. 1St Street * Duluth * 218-722-3925 1114 Cloquet Avenue * Cloquet * 218-879-1575 daughertyappliance.com Daugherty Appliance Sales & Service

Gary-New Duluth

By Brady Slater bslater@duluthnews.com

Fran Morris emerged from her home in the heart of Gary-New Duluth on 101st Avenue West to visit a new neighbor as he painted the door of a church he’s remodeling into his residence.

“Duluth is where all the space is,” said the man, an artist from Minneapolis wary of broadcasting his name.

With a quick “How are you?” Morris invited the man to a concert in the park later in the evening on what was a July day.

“This is a community,” Morris said, describing how the Gary-New Duluth neighborhood that grew up around the old U.S. Steel mill is now centered on its Stowe Elementary School and a burgeoning new community center and recreation area.

“I’ve lived here my whole life,” Morris said. “There’s a lot of older people selling their homes, and young families moving in. It’s a neighborhood in transition and it’s the place to be if you have a young family.”

Morris is a member of the Gary-New Duluth Development Alliance which has been responsible for the growth of the recreation area since 2016.

Located on 101st Avenue West next to Stowe Elementary, there is a new community center building surrounded by soccer fields, an outdoor performance pavilion, a community garden, sports court, and a dog park dedicated to K-9 Haas who was killed on duty earlier this year and whose Duluth Police Department handler, Aaron Haller, grew up in the neighborhood.

On tap are a second pavilion, a disc golf course, and an urban skate park currently under construction.

Leveraging $500,000 from the city’s half-and-half tax dedicated to neighborhoods along the St. Louis River corridor, the Gary-New Duluth Alliance has also used volunteer labor, fundraising and grantwriting to build up the nearly $3 million recreation area.

“It had been nothing,” Morris said, describing the efforts to build the now-sprawling community rec area.

The area that is now soccer fields used to lack drainage and be more suited to kayaking following a rain, she said. But that’s all changed. The YMCA provides after-school and year-round programming at the community center. Saturdays from 9-11:30 a.m. on the sports court are reserved for pickleball.

On Sept. 7, there will be a neighborhood festival and concert titled, “From the Alps to the Adriatic,” celebrating the neighborhood’s ethnic roots.

“It’s really rich in Eastern European history,” Morris said. “Hence our festival. It will feature Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian music and foods.”

Proud of her neighborhood and its new centerpiece, Morris produced a brochure featuring the names of scores of residents and businesses who have contributed to make it happen.

“We developed the area to give the community someplace to go,” she said. “This is the center of the community.”

12 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Audience members applaud Lee “Color Blind” Johnson after he performed a song as a one-man jug band during a free concert at the Gary New Duluth Community Center and Recreation Area earlier this summer. Steve Kuchera / skuchera@duluthnews.com

Morgan Park

By Brady Slater bslater@duluthnews.com

Jennifer Roy has spent the past 14 years in Morgan Park living at Spirit Lake Manor. She works across 88th Avenue West at Iron Mug Coffee House — the de facto neighborhood center.

“I wouldn’t live anywhere else,” she said. “It feels like a small town to me.”

Morgan Park was conceived as a workers’ community for the U.S. Steel plant adjacent to the neighborhood along the St. Louis River.

Though its telltale concrete block homes remain, U.S. Steel left for good in 1981, and the slow march of the neighborhood school came to an end in 2017, when Morgan Park Middle School was demolished.

But apartments are going up in its place. And it’s housing that Roy believes will be the revitalization of the neighborhood.

“Duluth is in so much need of housing,” she said. “It’s what brings people.”

Roy went on to talk about the $17.5 million apartments currently being constructed at the site of the old school along 88th Avenue West. Dubbed Morgan Park Estates, the complex that’s backed by developers from Eau Claire, Wis., will include ample green space to go with 96 market-priced units across eight buildings featuring 12 units each.

Eager to share more, Roy asked, “Have you seen the Thunderbird house?”

It’s yet another living option being constructed in the neighborhood — although a specialized one.

Located on Idaho Street, the ThunderbirdWren halfway house is nearly complete. The

sprawling complex is a $4.5 million treatment facility with 40 beds, 20 each for men and women. It will be operated by Minnesota Indian Primary Residential Treatment Center, which is moving ThunderbirdWren into Morgan Park from space it outgrew in downtown Duluth. It will continue to house Native Americans seeking treatment for chemical dependency or alcoholism.

“Treatment facilities are another service we need,” Roy said.

With two big projects going up in a neighborhood that spent recent decades losing major entities, things are looking brighter for Morgan Park.

“I’m excited,” Roy said. “We’ve got the river here with biking trails and kayaking. The cool thing to do is going to be to move out west.”

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 13

The new Thunderbird-Wren Halfway House is nearing completion in Morgan Park. Steve Kuchera / skuchera@duluthnews.com

Smithville

By Brooks Johnson bjohnson@duluthnews.com

By Brooks Johnson bjohnson@duluthnews.com

Squeezed between historic Morgan Park and expanding Riverside sits Smithville, a pastoral residential stretch below Bardon Peak. Crossed today by Skyline Parkway, the Munger Trail, Grand Avenue and by Stewart Creek down to the river near Munger Landing, the woodsy hillside habitat was first platted by new settlers along Spirit Lake as a “tourist retreat,” according to Zenith City Online.

Beyond the Spirit Lake Hotel, it eventually was home to the Smithville (elementary) School, a post office and the Work People’s College, a folk high school/radical labor college started by Finnish socialists that operated from 1907 to 1941. Tourism and labor politics — would it be Duluth without?

Lately Smithville has gotten a boost from a new $10 million housing project and a reconstructed Grand Avenue — plus the neighborhood lays claim to the new aerospace-focused Ikonics plant.

14 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

A 1927 view of Smithville, left, and Morgan Park, right, from Bardon Peak. University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections

A 1914 class of the Work People’s College, a Finnish folk school/radical labor college that operated until 1941.

Riverside

By Brady Slater bslater@duluthnews.com

The last morning in July started in the Riverside neighborhood of Duluth with a full marina and glassy water on the St. Louis River.

Tucked off Grand Avenue, Riverside is a small neighborhood with its yards and homes impeccably groomed. What was once a hospital is now a charming-looking assisted living facility. The community garden is lush with greens and the most dilapidated building is its biggest — the former business offices to the shipyard that dominated the neighborhood through the first half of the last century. Then, the residences housed the boilermakers, ironworkers and welders used in shipbuilding, specializing in military-grade fuel tankers.

“They employed a lot of people over here back in the day,” marina worker Eric Rice said. “They built like an average of 11 ships a month here — then one month made 43 ships when they were really in the push during World War II.”

Rice enjoyed coffee outside Spirit Lake Marina along with Ron Nelson and Kate Lincoln. The marina occupies the space which once belonged to the shipyard. The trio spoke admiringly of the marina and its owner Charlie Studuhar.

“He’s an activist,” Lincoln said. “He likes getting West Duluth cleaned up.”

“He’s a good guy,” Nelson said. “He strives to make things better.”

The owner sends his crew to trim weeds from public areas in the neighborhood the city workers don’t reach.

Even though it borders the water, the marina, with its seasonal boats and campers, is the center of town — what with its hidden gem of a gift shop and constant, if mellow, activity.

The slips are filled with sailboats

and pleasure crafts mostly. Fishing boats are generally kept closer to the lake and not so far west into the river estuary, Rice said. Seasonal campers, a lot of them retired folks, can rent land lots from May to October.

Recently, the workers built a small beach at the marina to launch the kayaks and canoes for rent.

Some of the largest boats remain perched on land — passion projects in progress, Lincoln said, that find their owners coming down when they can to tinker and renovate.

“Trying to get ready for next year,” Lincoln said, a morning breeze picking up.

Dr . Ve rn a Th orn To n, oB /GYn , is welcoming patients at CMH in Cloquet.

wo me n’ s he alTh se rV ic es:

• Minima lly-invasive surger y

• Menopausa l management

• Management of fibroids and pelv ic masses

• Premenstrual disorders

• Infertilit y, abnormal bleeding, and ot her fema le health issues

No referral necessary. Annual women’s wellness and Pap smear appointments available Patients love our free, convenient park ing.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 15

Geese swim in a slip at Spirit Lake Marina in Duluth’s Riverside neighborhood. Steve Kuchera / skuchera@duluthnews.com

ap po in Tm en Ts call 218-878-7626 our oB/GYn will see you now. cloquethospit al.com

Norton Park

By Kelly Busche kbusche@duluthnews.com

By Kelly Busche kbusche@duluthnews.com

Sestled between the St. Louis River and Interstate 35, the quaint Norton Park is home to numerous notable trails and part of the Lake Superior Zoo. The trailhead of Willard Munger State Trail starts in the Norton Park. It runs all the way to Hinckley, Minn., and its 70 miles pass through Jay Cooke State Park, Carlton, Moose Lake and Finlayson along the route.

The Western Waterfront Trail also zig-zags through the neighborhood and gives hikers or bikers a scenic path right along the St. Louis River. This five-mile trail runs alongside the Indian Point Campground, which is located on a small section of land that juts out into the river. Visitors can rent bikes, kayaks, canoes and pontoons to explore the nearby area and river.

A small section of the 300-mile Superior Hiking Trail also cuts through the neighborhood. It enters Norton Park near the base of Spirit Mountain Recreation Area to the south and leaves near the Lake Superior Zoo.

The neighborhood was the site of major flooding in 2012. While no one died, several animals from the

Lake Superior Zoo did.

A backed-up culvert in Kingsbury Creek, which acts as the border between Norton and West Duluth, caused the major flooding at the zoo. Floodwaters engulfed bird habitats and washed away barnyard animals, according to News Tribune reporting on the floods.

Some animals were able to escape because of the high-water levels. A polar bear named Berlin escaped, but was later found, tranquilized and brought back to the zoo.

Seals also escaped, with one making it as far as Grand Avenue. They were all found, and relocated back to the zoo. While numerous exhibits were damaged, the zoo opened less than one month later.

Throughout the rest of the city, the heavy rainfall and flash floods caused flooding, sinkholes, open manholes and mudslides.

16 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

4 levels of Art, History, and Culture await you! Open daily 9am - 5pm • www.duluthdepot.org Come to the Depot to see the trains...and so much more!

Workers with ATI clean and sanitize the polar bear exhibit at the Lake Superior Zoo, removing the covering of mud and other debris left by the flood in 2012. file / News Tribune

Bayview Heights

By Tom Olsen tolsen@duluthnews.com

Located atop a steep hill overlooking West Duluth, Bayview Heights is largely isolated from the rest of the city. But it serves as Duluth’s front door, offering picturesque views of the city and harbor below as travelers follow scenic Skyline Parkway or descend Thompson Hill along northbound Interstate 35.

One could be excused for mistaking this western neighborhood as part of Proctor. In fact, residents send their children to Proctor schools, including the neighborhood’s namesake Bay View Elementary School.

For all practical purposes, Bayview Heights forms one larger community with Proctor — though the cities are officially divided by the appropriately named Boundary Avenue, which roughly connects the top of Spirit Mountain to the South St. Louis County Fairgrounds. Many neighborhood residents live in Zenith Terrace, the city’s largest manufactured-home park.

The neighborhood was first platted in the 1880s to accommodate anticipated growth in the fledgling industrial city of Duluth. But it never achieved significant population growth — perhaps in part due to its elevation — though the neighborhood did serve to accommodate rail yard workers in the neighboring city then still known as Proctorknott.

Today the neighborhood is mainly accessed via

U.S. Highway 2 or Vinland Street, but in its early days the commute was made by a lesser-known rail incline. Known by various names, including the Duluth Belt Line Railway, it began operation in 1889, carrying passengers 600 feet uphill from 61st Avenue West and Grand Avenue to 77th Avenue West and Vinland Street.

While the rail shuttered in 1916 as new transportation options emerged, its original path can still be seen more than a century later, with power lines now occupying the clearing.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 17

The Duluth Belt Line Incline connected Bayview Heights with lower West Duluth in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In this photo, from approximately 1900, the rail can be seen running up the 600-foot hill from the lower station at 61st Avenue West and Grand Avenue.

(Photo courtesy UMD/Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections)

Visitors take in the view of Duluth, Superior and the harbor from the Thompson Hill Information Center along Skyline Parkway in Duluth’s Bayview Heights neighborhood. (2005 file / News Tribune)

Fairmount

By John Lundy jlundy@duluthnews.com

The sounds that Fairmount neighborhood residents hear at night could include the roaring of lions.

The small West Duluth neighborhood probably is best known as the home of the Lake Superior Zoo — although Fairmount also boasts quiet neighborhoods and hiking, biking and snowmobiling along Kingsbury Creek.

The zoo, founded as the Fairmount Park Zoo in 1923, currently includes military macaws, flying geckos, African lions, snow leopards, laughing kookaburras, prehensile-tailed skinks, shetland sheep, prairie dogs and spectacled owls — among many others — as residents. (See the entire list at its website, lszooduluth.org.)

On rare occasions, an animal or two has wandered beyond zoo boundaries.

In 1950, a 400-pound horned wild sheep went on the loose, according to “Boomtown Landmarks,” a book edited by Laurie Hertzel in 1993. A 14-yearold boy captured the sheep with a flying tackle and probably instantly would have been signed by the Minnesota Vikings if they had existed at the time. A wallaby escaped in 1989 and a second wallaby in 1990, Hertzel reported. Both were struck and killed by cars.

In “Duluth’s Historic Parks,” Nancy S. Nelson and Tony Dierckins tell about Bessie the Asian elephant, which arrived at the zoo in 1929 and left, frequently, of her own accord. In July 1941 she pushed over a portion of the fencing surrounding her enclosure and “roamed about the west end of the city for several hours.”

Famously, Feisty and Vivian the seals and a polar bear named Berlin escaped from their enclosures during the flood of June 20, 2012. Only Feisty made it out of the zoo, being discovered by passers-by on Grand Avenue. All three were moved to other places in the flood’s wake.

One zoo critter escaped in a different sense. A mongoose named Mr. Magoo was donated to the zoo by a foreign sailor in 1962, according to “Boomtown

Landmarks.” It turned out, though, that mongooses weren’t allowed in the United States and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wanted it destroyed. A grass-roots protest was stirred up, and eventually Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall commuted the death sentence, channeling Dr. Suess in a telegram to Duluth officials: “There can be no threat of an excess of mongooses being loosed in Duluth as long as Magoo is not two.”

A fan of warm tea with sugar, vegetables and meat, Mr. Magoo died of natural causes in 1968.

18 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Ozzie the desert tortoise struts past the Lake Superior Zoo’s pavilion shortly after it was renovated in 2014. The zoo is closely identified with the Fairmount neighborhood. file / News Tribune

Mike Janis (left) Sam Maida and Basil Norton surround the final resting place of Magoo the Mongoose at the Lake Superior Zoo. file / News Tribune

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 19 5611 GRAND AVENUE • SPIRIT VALLEY, DULUTH 218 628-2249 Mon., Tues., Wed. & Fri. 9 a.m. — 5:30 p.m. Thurs 9 a.m. — 7 p.m. Sat 9 a.m. —3 p.m. *See sales associate for details. • Largest selection, • Better pricing, • Better warranty, and the styles, colors and patterns you want Get the best under your feet Sales • Installation Carpet, Vinyl, Tile, Hardwood Flooring • Armstrong • Mannington • Karastan • Tigressa • Lees • Florida • Anderson • Lauzon • Happy Floors • Shaw • Bruce • Mohawk • Paramount 2017 & 20 18! The Northland’s Leader in Floor Covering Since 1955

Irving

By Tom Olsen tolsen@duluthnews.com

Situated along the St. Louis River, this western neighborhood is packed with history.

Irving developed in the late 1800s as the region flourished, with the village of West Duluth officially uniting with the city of Duluth in 1894. Its Raleigh Street served as a major business hub in those early days.

Owing to its location along the river, the neighborhood has long been known for industry, and it still retains those roots. The Verso paper mill, Loll Designs and Moline Machinery are just a few of the businesses that line South Central Avenue and Waseca Industrial Road.

Today, the once-active Raleigh Street business district is gone and that industrial hub is off the beaten path for most. But not so long ago Irving was a high-traffic center in West Duluth. The Arrowhead Bridge linked Duluth to Superior’s Billings Park neighborhood from 1927 to 1984, when it was replaced by the nearby Bong Bridge.

While the Superior side is home to a public boat ramp, little remains on the Duluth approach. The city later opened the Grassy Pointe Trail, a short path along the water-filled canal that once housed the bridge near Lesure Street, but it has since fallen into disrepair.

Closer to Interstate 35 is a residential section — which includes the neighborhood’s namesake Irving School Apartments. The Renaissance-Revivalstyle building served as an elementary school from 1895 until 1982, and a decade later it was repurposed as an apartment building.

Another significant landmark was lost more recently. The 75-year-old

Irving Recreation Center was razed in 2014, two years after it sustained significant damage in Duluth’s 2012 flood. With it went two hockey rinks. Today, the park remains, but with playground equipment, a sports court and a large field.

A few blocks away is the beginning (or end) of the Western Waterfront Trail, which offers hikers scenic views of the St. Louis River for more than three miles as it connects Irving with the Riverside neighborhood.

20 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

A flooded Irving Park and surrounding neighborhood as seen from the air in June 2012. The recreation center was severely damaged and was torn down two years later. (2012 file / News Tribune)

A water-filled canal along Grassy Point in the Irving neighborhood used to serve as one end of the Arrowhead Bridge, which closed in 1984. The city later established a short hiking trail near the canal. (1997 file / News Tribune)

The former Irving Elementary School was converted into apartments in the early 1990s. (1993 file / News Tribune)

By John Lundy jlundy@duluthnews.com

The Cody neighborhood has a parochial school, tennis courts, commanding views of the St. Louis River Valley and residential neighborhoods characterized by traditional, older homes. It also includes the length of Cody Street. What it doesn’t have — what it never had — was the Cody Hotel.

That establishment — named for William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody and run by his sister, Helen Cody Westmore — was located at 332 N. Central Ave., in Spirit Valley, according to Duluth News Tribune archives and Paul Lundgren’s “Area Women in History,” an article from the now-defunct The Area Woman magazine.

The Cody Liquor Store and the Cody Drug Store also were in Spirit Valley, on the hotel’s ground level.

For that matter, the home where Westmore lived is in the 2600 block of 77th Avenue West — the Bayview Heights neighborhood.

It’s not entirely clear why the Cody neighborhood carries the Cody name, but it does give the western Duluth neighborhood a sort of Wild West cachet.

The Cody neighborhood was once the home of Denfeld High School, built on the west side of Central Avenue in 1915. When the current Denfeld opened 11 years later, the Central Avenue building became West Junior High School. Laura MacArthur Elementary School was built next door in 1957. West closed in 1983, allowing Laura MacArthur to spread through both buildings.

When the new Laura MacArthur opened across the street in 2011 (to the Denfeld neighborhood), the old building was demolished. That land, bordered by North Central Avenue, West Sixth Street, North 56th Avenue West and Elinor Street, now is mostly green space, with a corner set aside for school system tennis courts and another corner for field events during track meets. Informally, it’s a popular spot for people to play fetch with their dogs and for children to go sledding in the winter.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 21

Cody

FIND YOUR SUPERIOR . star t your journeyuwsuper.edu Macie Steffen Class of 2020 Early Childhood Education FIndYourSuperiorAdvert3.58x6.45.indd 2 7/17/19 1:22 PM

The former location of Laura MacArthur Elementary School in the Cody neighborhood of Duluth. (Clint Austin / caustin@duluthnews.com)

Spirit Valley

By Brooks Johnson bjohnson@duluthnews.com

This is the beating heart of West Duluth; the commercial capital; the boulevards of business; streetlights, people.

Since West Duluth was its own city for a minute (it became part of Duluth in 1894), a central business district grew naturally along Grand and Central avenues as industrial and residential growth took off in the bustling burb.

A city publication from 1974 stated that West Duluth “was the result of geographic necessity” for locating expansive industries: “Here were established firms manufacturing engines, mill and mine machinery, woolen goods, beer, lumber, boilers, furniture, bricks and office machinery — the firms generating new exports from the city’s local economy and the all-important opportunity for new breakaway firms which created new products and work.”

The closure of many of those businesses, the arrival of Interstate 35 and the removal of old rail lines has repeatedly threatened the community, but it wouldn’t stay down.

“West Duluth’s industrial, commercial and residential districts have been at times crushed, moved, surrounded, carved into pieces,” reads a 1994 book celebrating the centennial of West Duluth’s union with Duluth, “and yet continue not only to survive, but are commanding the respect and admiration of surrounding communities for the degree of stamina, pride, resourcefulness, flexibility and foresight shown by West Duluth, its residents and its community leaders.”

22 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

The north side of the 5700 block of Grand Avenue in Spirit Valley circa 1960. Businesses include Ben Franklin, Peggy Ann’s Shop, James O. Andersen Pharmacy, and the Doric Theatre. University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections.

1924 Fourth of July parade on Grand Avenue between 57th and 56th avenues. University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections

Denfeld

By John Lundy jlundy@duluthnews.com

Although it includes residential neighborhoods and businesses along Grand Avenue, the heart of the Denfeld neighborhood — and arguably all of West Duluth — is Denfeld High School. The school wasn’t always in what’s now known as the Denfeld neighborhood. It opened as one floor of Irving Elementary School (now Irving School Apartments) in 1905 and later was named Duluth Industrial High School, according to the historical section of the school’s website. The high school was moved to 725 N. Central Ave. in 1915 where it took the name of about-to-retire schools Superintendent Robert E. Denfeld. It found its current home, bordered by Grand Avenue, 44th Avenue West, 46th Avenue West and West Sixth Street, in 1926. The red brick and limestone structure cost $1.25 million to build, according to the school website. It features medieval carvings by master stone carver George Thrana, who came to Duluth from Norway in 1899. The school’s auditorium, built for $25,000, was renovated in 2006 at a cost of $1.2 million.

West Duluth residents are fiercely proud of their high school. When three different plans were considered for restructuring the schools in 2007, the “White Plan” that would have transformed the Denfeld building into a middle school and would have built a new western high school didn’t go over well. That remained the case even when a consultant from Johnson Controls warned that keeping Denfeld as a high school “would take significant changes, like driving bulldozers through parts of

the building,” according to a News Tribune report at the time.

A survey at the time by national research firm Decision Resources found 56 percent favored the Red Plan that kept Denfeld as a high school, 12 percent the Blue Plan that would have kept Central as the only high school, and 10 percent favored the White Plan.

“The results are clear,” said Bill Morris, president of the survey company, according to a News Tribune story then. “You have a solid working majority in favor of keeping Denfeld as a high school in this district.”

The school was closed for the 2010-11 school year while the bulk of renovations took place. The renovated school, open for the 2011-12 school year, combined the new with the old. The skylight from the new commons area provides a view of Denfeld’s iconic clock tower.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 23

Denfeld High School in the Denfeld neighborhood of Duluth. (Clint Austin / caustin@duluthnews.com)

Piedmont Heights

By Tom Olsen tolsen@duluthnews.com

With housing, recreation, business and education opportunities, Piedmont Heights offers a suburban vibe close to the heart of Duluth.

The neighborhood was platted by the city of Duluth in 1891 as a “streetcar suburb” — a primarily residential addition, accessible via rail — built to accommodate Duluth’s flourishing population, which burgeoned from 33,000 in 1890 to 53,000 in 1900.

Piedmont Heights covers a fairly vast area, with borders of Haines Road to the east, Anderson Road to the north, Trinity Road to the west and Skyline Parkway to the south. Piedmont Avenue serves as a main thoroughfare, cutting through the oldest part of the neighborhood where a small business district includes the likes of Big Daddy’s Burgers.

The neighborhood includes abundant single-family homes, with newer development bringing a twisting network of full of culde-sacs, including Exhibition Drive, where residents are known for their annual over-thetop Christmas light displays. While seemingly isolated, residents have quick access to both downtown Duluth and Miller Hill Mall corridor via U.S. Highway 53.

Children today attend Piedmont Elementary School, which was built anew in 2011, but longtime residents will recall the Ensign School, a neighborhood landmark from 1908 until 1981, when it was destroyed by arson two years after closing. On its eastern edge, Piedmont Heights is home to Lake Superior College, which has continued to expand since it was established in 1995 at the site of the former Duluth Technical College.

The neighborhood also offers one of the busiest and most extensive trail systems in the city, used year-round for hiking, mountain biking, cross-country skiing and snowmobiling.

Lake Superior College has continued to expand since it was established in 1995 on the site of the former Duluth Technical College on

24 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Andrea and Dave Hepola walk their mixed-breed dog, Buster, and German wirehair, Hazel, on the Piedmont hiking trail in Duluth. The neighborhood offers an extensive trail system. 2006 file / News Tribune

the eastern edge of the city’s Piedmont Heights neighborhood. 2019 file / News Tribune

Lincoln Park

By Brooks Johnson bjohnson@duluthnews.com

Full disclosure: I live here. I write that first because like every neighborhood in Duluth, Lincoln Park inspires a great deal of pride. As a place, it is sprawling and diverse and beautiful. As an idea of a place, it is a blue-collar community united by human problems and heartfelt solutions. Young families like mine share the beat-up roads with longtime residents, our homes tightly packed and our resolve firm in the face of the damage wrought by opioids and meth. We dream of better lives for ourselves and our children, but not

somewhere else. Right here.

I took my parents up to the shining Lincoln Park Middle School for a look out over the bay this summer. The crossroads of industry, the seemingly limitless sea beyond and all the quiet homes below — this is home.

To read more about Lincoln Park’s past, present and future see Page 26-27.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 25

Clyde Iron and the Essentia Duluth Heritage Center in Lincoln Park. Steve Kuchera / skuchera@duluthnews.com

‘Beautiful and a little rustic’

Lincoln Park a place of change

By Brooks Johnson bjohnson@duluthnews.com

Here’s a neighborhood with a reputation. What kind of reputation? Depends on what you’ve heard.

Some know it for the breweries, cideries, restaurants and shops that have proliferated largely along West Superior Street — the Lincoln Park Craft District. Others know it as a historically downtrodden, highcrime area — the “Friendly West End,” they’ll intone ironically.

But Lincoln Park is too big, too diverse to be so easily pinned down. It embodies both of those descriptions, and so much more.

West End

Before it was Lincoln Park it was the West End. Before it was the West End it was, in part, Rice’s Point, one of Duluth’s founding townships in the late 1800s. As new residents flocked to the swiftly developing port city, many European immigrants made their homes past the Point of Rocks.

“While many skilled and professional transplants to Duluth mostly found places to live north and east of downtown, families of unskilled laborers settled in undeveloped areas, mostly found in the West End, close to the mills and docks where they would find work,” wrote Tony Dierckins and Maryanne C. Norton in their book “Lost Duluth”. Duluth’s first ore docks, those arteries of industry, were joined by a number of other businesses and industries spanning from cigar makers and candy companies to clothing companies and knitting mills: Clyde Iron Works, ZinsmasterSmith Bread Company, The Duluth Brewing and Malting Company, F.A. Patrick Company, The Bridgeman-Russell Company, Duluth Tent and Awning, Anderson Furniture and more.

The neighborhood grew and shapeshifted over the decades as these and other industries drew the residents and businesses needed to support them. In 1920 the neighborhood’s population reached 19,000 — today it is

26 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Looking west on Superior Street at 19th Avenue West circa 1935-1939.

Courtesy Minnesota Streetcar Museum

less than half of that.

Duluth and the West End especially followed many Rust Belt cities into decline in the second half of the 20th century as manufacturing moved overseas, automated or otherwise folded, leaving hollow campuses and broken promises.

A few rebranding attempts would follow.

“Several decades ago the West End Business Association added the word ‘friendly’ to the name of the business district, which became ‘The Friendly West End.’ It suited the area, I thought,” wrote Linda LeGarde Grover in a 2017 column recounting her and her father’s upbringing in the neighborhood. “Sometime during the 1990s the entire neighborhood added another identity, ‘Lincoln Park’ which is a nice name, too: the park itself is beautiful and a little rustic, like the West End. My dad told me, however, that it would always be the West End to him.”

Lincoln Park

It was late in 1995, in fact, that Mayor Gary Doty and West End business/community leaders agreed to change the name to Lincoln Park. It was not immediately embraced, but Craig Lincoln wrote in a News Tribune column in 1996 that the debate over the name was also a debate over the neighborhood’s very character.

“People in the West End knew it was a good place to live and that a lot of big changes were making it better. Some people from other areas of the city thought of the neighborhood as an area plagued by seedy bars and urban blight. The image of seedy bars is one reason business owners and the West End Neighborhood Coalition wanted to drop the old name and adopt the name of the neighborhood school and popular park along Miller Creek. They hoped the new name would reflect those positive changes.”

Visiting the namesake park itself, a wooded trail

follows Miller Creek on one side; a winding road chases it on the other. It is quiet here, in the middle of Duluth’s densest neighborhood, even when you arrive at the empty playground on a warm summer afternoon.

Don’t be fooled; Lincoln Park today is full of young families — compared to the city overall there is a higher percentage of children living here, and the population overall skews younger. It is more diverse, as well: One in five neighborhood residents is nonwhite, compared with one in 10 across the city as a whole.

But one in four children in Lincoln Park live below the poverty level — twice the state average — and 60 percent live in single-parent households, again twice the state rate, according to data from Bridging Health North.

“Finding good-paying jobs is tough,” said Jodi Broadwell, executive director of the Lincoln Park Children & Families Collaborative. “And safety is always an issue. One of our moms has video cameras around her house and doesn’t let children play outside without her.”

As opioids and meth continue to ravage poorer parts of the country, Lincoln Park has seen its share of busts, stray needles, overdoses and drug-fueled violence.

But it’s not all bad news.

In Broadwell’s years working and living in the neighborhood, she has seen kids eager to help out and be good neighbors.

“It is like a village and we are trying to take care of each other,” she said. “Kids in general are easy to talk to, they just need to have caring adults in their life and things to keep them busy.”

That new arcade might help keep them busy. The commercial development rapidly remaking several blocks of West Superior Street and beyond isn’t slowing anytime soon as more businesses are added every month to the Craft District.

When Broadwell looks at all that activity she’s excited, because she has money to spend there every now and then. But many residents don’t have a dime left over after balancing their childcare, rent, transportation and grocery budgets — nearly half of renters already spend more than a third of their income on rent. And if rents and property taxes rise as the commercial success draws new residents?

“The business community is touting revitalization, but residents are worried about gentrification,” Broadwell said. “There are two conversations happening.”

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 27

Miller Creek alongside 25th Avenue West in Lincoln Park circa 1900. Courtesy the Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections.

Duluth Heights

By Kelly Busche kbusche@duluthnews.com

One of Duluth’s largest neighborhoods, Duluth Heights, sits atop the hills of the city.

Its lengthy corridor of numerous retail shops along Miller Trunk Highway serves as the area’s main shopping destination.

But on its southern point, a different type of activity is available: Enger Park Golf Course stretches across the neighborhood. Adjacent to the public golf course is Enger Tower. The five-story tall tower, built in 1939, offers astonishing views of downtown Duluth, Canal Park and Lake Superior.

From its southern side, the neighborhood stretches northeast to the Marshall School, up to an area just north of West Arrowhead Road, and then south to the Miller Hill Mall. Numerous parks, like Duluth Heights Park, Web Woods and Pennell Park, dot the neighborhood.

Miller Hill Mall’s 1973 opening transformed the neighborhood into a “regional shopping hub,” Jim Skurla, a University of Minnesota Duluth economist, said in a 2013 interview with the News Tribune. While some malls have faced closure as online shopping dominates the market,

The neighborhood’s other retail spaces include T.J Maxx, Cub Foods, PetSmart, Best Buy, Home Depot and Target, among numerous others.

The initial work for the hill-topping neighborhood came in the late 1800s, when the Highland Improvement Company, which owned over 1,000 acres along Skyline Parkway, had a goal to develop the area into a neighborhood.

A prospectus from the company said in the Duluth Daily Reader that the neighborhood was “one of the most wonderfully picturesque and unique boulevards in the world,” according to Zenith City Press.

To access the neighborhood, an incline railway connected downtown Duluth to housing developments in Duluth Heights. It ran from 1891 through 1939, when it was scrapped as automobiles became a popular mode of transportation.

Now, U.S. Highway 53 and Central Entrance feed the lower neighborhoods into Duluth Heights.

28 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

In 1988, Miller Hill Mall’s front entrance boasted the Glass Block department store and a three-screen movie theater. The movie theater closed in 2000. (File / News Tribune)

Getting up the hill was the impetus for Duluth’s entry into mass transit in the 1880s. The incline railway was built in 1891. Courtesy Aaaron Isaacs

Central Hillside

By Brady Slater bslater@duluthnews.com

The Central Hillside neighborhood in Duluth is one of the city’s oldest, most diverse, poorest and most vibrant neighborhoods.

It is home to myriad social service agencies, shelters and low-income housing options. Because of the steep landscape, it offers some of the city’s best views of Lake Superior. It also features majestic older homes and even some of the city’s most modern examples of residential architecture.

It is home to some of the city’s richest historical markers (Old Central High School) and many of its most active political and cultural voices.

“It’s a super important neighborhood because it shows how diverse Duluth could be,” Lydia Komatsu said. “A lot of people think of Duluth like there’s the lake, the breweries, the trail access, up-and-coming restaurants, cideries and distilleries and that it’s a destination spot. But there are real people living here, trying to survive, make a name for themselves and take care of their families — and a lot of them are here, in this neighborhood.”

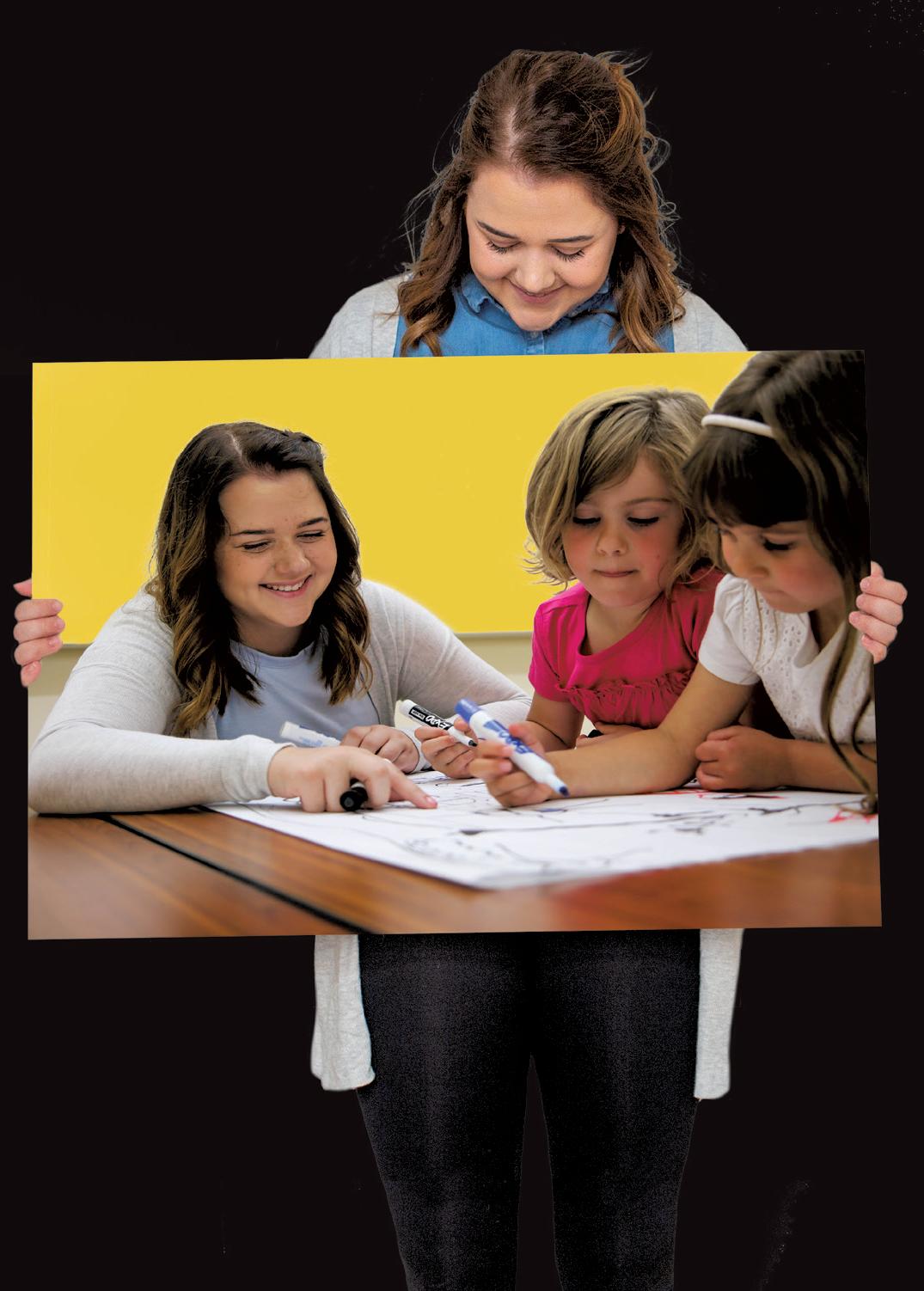

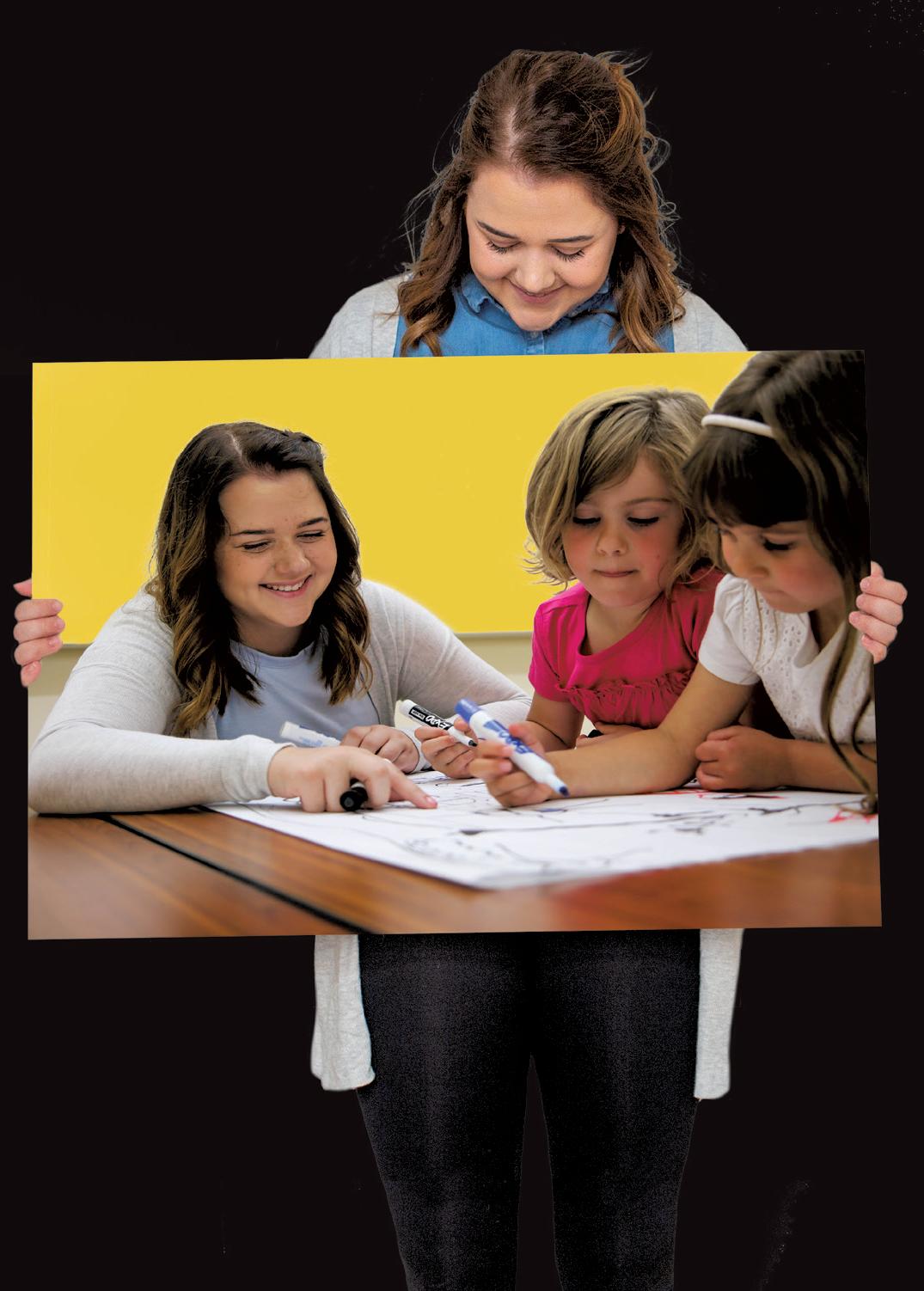

Komatsu was speaking from inside the Washington Community Center at the corner of West Fourth Street and Lake Avenue. She’s program coordinator of Neighborhood Youth Services, a yearround drop-in center for school-age children. As many as 70 children access the center on any given weekday throughout the year.

They use the gymnasium, computer lab, go on field trips to parks and destinations throughout the city and have access to a cafeteria with regular meals and snacks.

Community partners offer regular programming, including one from Men as Peacemakers called Champions Building Champions.

Affiliated with The Hills, which operates juvenile justice and residential treatment centers in Duluth, Neighborhood Youth Services has been operating for

more than 30 years, Komatsu said. Free to families, it was designed to look after children from the Central Hillside and is open to other areas of Duluth.

“It’s a safe place for kids to come,” Komatsu said. “Neighborhood Youth Services was built to provide a buffer for kids from entering the juvenile justice system. It’s a healthy place for kids to stop in and just be themselves, while also serving as a preventative measure from participating in less safe activities on the streets.”

Open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. in summers and 2:30-7 p.m. during the school year, Komatsu said it’s hard to quantify the results, but calls it an “extremely rewarding and invigorating space.” As she spoke, a host of children sped into a gymnasium bouncing basketballs and throwing up shots.

“Neighborhood Youth Services is definitely in this neighborhood for a reason,” Komatsu said. “We know there are child care needs that are maybe not accessible to some of the families living in this neighborhood.”

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 29

Ziyah Xzandra, left, smiles as Star Perry finds a word in her word search during the Juneteenth celebration at Central Hillside Park on June 15 in Duluth. Ellen Schmidt / eschmidt@duluthnews.com

Downtown

By John Lundy jlundy@duluthnews.com

There are a billion reasons why everything is going to change for Duluth’s downtown.

“Downtown is going through a major transformation, one that we haven’t seen the likes of in a long time,” said Kristi Stokes, president of the Greater Downtown Council. “When you have more than $1 billion of investment coming into a neighborhood in the next year or two, that will make some significant changes to the neighborhood.”

Stokes was referring to the $1 billion investment planned in new construction between Essentia Health and St. Luke’s — already underway in the case of St. Luke’s and scheduled to begin this fall for Essentia.

Although the hospital construction will technically take place in the East Hillside neighborhood, Stokes is confident of a ripple effect — or, perhaps, more of a tidal wave — surging into downtown.

It dwarfs another big project, the reconstruction of Superior Street downtown, which is in the middle of its three-year lifespan.

“That was going to be a transformation for the downtown,” Stokes said. “The engineer even jokes that this is now one of the smaller projects in the downtown.”

As an example of the residual effect, she pointed to the plans for a 15-story, 204-unit apartment building in the 300 block of East Superior Street, at the site of the Voyageur Lakewalk Inn.

It underscores that downtown is becoming a place

to live as well as a place to work and play, Stokes said.

While new development is grabbing attention, Stokes pointed to three aspects of downtown that might get overlooked:

The Skywalk system offers 3.5 miles of out-of-theweather connections. Many people use the indoor pathway for exercise, Stokes said, especially in the winter.

The Clean and Safe team. Wearing bright safetygreen shirts and navy pants or shorts, they operate as ambassadors for the Greater Downtown Council. “We hire for personality and train for skills,” Stokes said. “They all have great personalities.”

The historic. “If you look up, you see so much of our history, the architecture, the years on some of the buildings,” Stokes said. “We are the heart of our community, and we were the heart of our community when we started. It’s really great to be able to share that story.”

30 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

Duluth’s downtown takes on additional vibrancy during special events, such as this scene from Sidewalk Days in 2018. file / News Tribune

Park Point

By Peter Passi ppassi@duluthnews.com

Duluth is home to the longest natural freshwater sand spit in the nation, stretching about seven miles from Minnesota’s shore across the mouth of the St. Louis River. But this narrow strip of sand known as Minnesota Point (or Park Point) really is more of a man-made island these days, since residents punched a shipping channel through it in 1871.

Long before the canal, Minnesota Point was a popular summer gathering place for the region’s indigenous Anishinaabe people.

In 1679, the first documented European explorer arrived on the scene, when Duluth’s namesake, French Canadian Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Luht, and his crew arrived at the short canoe carryover indigenous residents used to cross the spit into Duluth’s natural harbor. They called the path Onigamiinsing, meaning “little portage.”

After European contact, Duluth soon emerged as a fur-trading center, with French and English fur companies vying for valuable pelts.

The Twin Ports also came to serve as an important harbor, offering the westernmost access to the Midwest via the Great Lakes.

Initially, Duluth’s neighbor, Superior, had the edge in attracting ship traffic via a natural point of entry to the east.

In 1870, however, the Minnesota Legislature authorized funding for a canal to be dug on the Duluth-side of the harbor, opening the city to new shipping opportunities. Superior objected out of fears that its port facilities would be disadvantaged and sought to block the project in court.

While Superior did succeed in obtaining an injunction to stop the work in the spring of 1871, it was too late. The Duluth Entry had already been dug, and subsequent court decisions ensured the city could keep the passage.

While Park Point, also once known by locals as Middleton, was part of the original city of Duluth

when it incorporated in 1857, the city unincorporated just 20 years later in the face of economic headwinds.

Minnesota Point incorporated as a village that same year but later rejoined the city in 1889, after Duluth officials pledged to build a bridge to connect the Point with the mainland. It took more than 15 years to make good on that promise, with the construction of an aerial transfer bridge.

This original structure used a gondola to convey vehicles and people across the Duluth Entry. It was modeled after a similar structure built across the Seine River in Rouen, France.

The gondola was replaced with the modern-day Aerial Lift Bridge in 1929.

Minnesota Point emerged as a popular beach destination and was home to a number of summer cottages, including a colony of “hayfever cabins” marketed to people across the nation suffering the effects of severe seasonal allergies and seeking refuge in the relatively pollen-free breezes of Lake Superior.

But increasing numbers of people began to make their year-round homes on the Point, where the value of land has appreciated greatly in recent years. Today the neighborhood contains a mix of modest older homes sprinkled amid lavish beachfront residences.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 31

Duluth welcomes its first foreign saltwater ship, the Ramon de Larrinaga, on May 3, 1959, after the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. (Photo courtesy of UMD Kathryn A. Martin Library Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections)

East Hillside

By Peter Passi ppassi@duluthnews.com

Perhaps no other part of Duluth will undergo such a transformation in the next several years as the city’s East Hillside neighborhood.

The region’s two largest health care providers — Essentia Health and St. Luke’s — plan to invest a combined $1 billion in their medical campuses in the coming years. The projects will consolidate operations into tighter footprints and should free up additional land in the area for redevelopment, including highlysought-after housing.

Duluth’s East Hillside offers impressive lake views, yet at a modest cost compared to housing in some other parts of the city.

The neighborhood brushes up against Chester Bowl and Chester Creek. It also includes an attractive waterfront, featuring Leif Erickson Park and Rose Garden, as well as a heavily traveled segment of the Lakewalk, part of which is still undergoing repairs in the wake of recent storm surge damage.

While Duluth’s vibrant East Hillside displays

2011

letters of a new sign on Essentia Health’s First Street Building in 2011. Both Essentia and St. Luke’s plan massive investments in their East Hillside medical campuses in the next several years. Together, they’re expected to pour $1 billion into new facilities.

diversity in its population, it is also the seat of one of the most privileged and exclusive of institutions — the Kitchi Gammi Club, founded in 1883. The private clubhouse, built at Ninth Avenue East and Superior Street in 1913, remained the domain of some of Duluth’s richest and most powerful business leaders, but women weren’t able to join as independent members until the 1980s.

The Kitch has long since become a more inclusive organization, welcoming members of both sexes, but its reputation as a seat of wealth and deal-making remains.

On the opposite side of Superior Street, another historic structure remains — Fitger’s Brewery Complex.

Fitger’s traces its roots back to the late 1850s, when Duluth’s first brewery, the Luce/Busch Brewery, launched in East Hillside, drawing its water supply from a stream aptly dubbed Brewery Creek.

The upstart brewery struggled and in 1882, it changed hands, eventually becoming the A. Fitger & Co. Lake Superior Brewery.

The brewery survived Prohibition by producing non-alcoholic beverages and candy, and distributing cigars. It came back strong when Prohibition ended. At its peak, the brewery employed about 250 people and produced 150,000 barrels of beer annually, but the operation folded in 1972, forced out of business by larger producers. The complex has since been reborn as a hotel, boutique retail center and a brewpub.

32 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

This photo, probably taken sometime between 1905 and 1908, shows the Fitger & Co. bottling department and brewhouse. The brewery closed in 1972, crowded out of the market by larger mass producers. The building in the 600 block of East Superior Street now houses a hotel, boutique retail shops and a brewpub operating under the Fitger’s flag. Photo courtesy of UMD Kathryn A. Martin Library Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections

File photo/Workers with Lakehead Sign install the

Kenwood

By Kelly Busche kbusche@duluthnews.com

While residential homes make up most of the Kenwood neighborhood, the College of St. Scholastica serves as the neighborhood’s key feature.

But the Catholic-affiliated school wasn’t always located in the neighborhood.

In 1892, dozens of nuns from St. Benedict’s Convent in St. Joseph, Minn., opened a Benedictine convent and academy in Munger Terrace, according to CSS’ website.

Enrollment quickly grew, causing it to move several years later to a building near downtown Duluth. More growth came to the area in the early 1900s, leading the school to move once again — this time, to its current location.

The land in Kenwood that the school now sits on was previously known as the “Daisy Farm,” according to reporting from CSS’ student newspaper, The Script.

While Mother Scholastica gazed on the land that was just purchased for the school, she said: “My dream is that someday there will rise upon these grounds fine buildings, like the great Benedictine Abbeys. They will be built of stone; within their walls higher education will flourish.”

Mother Scholastica’s dream was realized: The campus’ landmark Tower Hall, which was built in the early 1900s, is made of bluestone.

The nuns’ contributions also extend to Duluth’s health care industry.

In response to a typhoid outbreak in 1898, the nuns started St. Mary’s Hospital, according to News Tribune reporting.

After a few mergers, this hospital eventually became the flagship hospital for Essentia Health. The school still has a strong connection to health care, as it offers degrees in nursing, occupational therapy and athletic training, among numerous others.

Just over 4,000 undergraduate and graduate students attended the private school during fall 2018, according to the school’s website.

Higher-density housing arrived in the neighborhood, with the opening of the $21 million

Kenwood Village in 2017. Mixed-use space at West Arrowhead Road and Kenwood Avenue also opened near the apartment building.

But other efforts to introduce higher-density housing came with staunch resident opposition.

Last year, neighbors opposed changes that would allow for higher-density housing, like apartments. Duluth City Council rejected the proposal to rezone in late 2018.

August/September 2019 • DNT Extra 33

NIGHT OUT? WE'VE GOT YOU COVERED. 222 East Superior Street | zeitgeistarts.com Movies, Live Theater, Improv Comedy, Art, and a Restaurant & Bar!

This aerial photo of the College of St. Scholastica taken in 2017 shows how much the college has expanded since its early years. (file / News Tribune)

Endion

By Adelie Bergstrom abergstrom@duluthnews.com

Endion, platted in 1856, began as a township that grew from land claimed by the Hon. William Wallace Kingsbury, delegate to the Minnesota Territorial House of Representatives and later a member of Congress. Endion was annexed to Duluth in 1870.

Duluth’s East End, as Endion was primarily known at the time, grew out from the city’s central district as the 19th century drew to a close. Between 1890 and 1910, Duluth’s population more than doubled, from about 33,000 to about 78,000, and the East End became a fashionable residential district for many of the city’s businessmen and civic leaders.

Today’s Endion neighborhood officially runs between 14th and 26th avenues east and from the lakefront up the hill to either Fourth or Eighth avenues, depending on where you are.

East Superior and East Fourth streets are two main thoroughfares, as well as 21st Avenue East, which connects Interstate 35 with the city’s two universities and several nearby neighborhoods on top of the hill.

London Road is Endion’s other major artery, with a mix of businesses and a few remaining residences.

Pictured in about 1910, the Richard M. Sellwood home at 2215 E. Second St. exemplifies the Endion neighborhood’s grand homes. Between 1890 and 1910, many of Duluth’s business leaders moved into what was then called the East End. Photo courtesy UMD/Northeast Minnesota Historical Collections

The name comes from the New London town settlement that preceded today’s Lakeside. In the 1870s and 1880s, the “New London road” connected the town with Duluth to the south, and the name stuck, first as London Avenue and then London Road by the mid-1890s.

The neighborhood “reflects the prosperity the Zenith City enjoyed in the decades bracketing the turn of the 20th century, when it emerged from a collection of ramshackle pioneer villages to become, by 1910, an urban metropolis 28 miles long and 3 miles wide,” according to a publication from the Duluth Preservation Alliance.

“It was during this time that the population boomed, with the wealthy settling in the East End in part because the terrain was rocky and too costly for the working class to develop — which explains the neighborhood’s concentration of mansions and other luxury homes.”

Today, those homes, many set back on large lots, line the neighborhood’s shady, well-kept streets, dreamed up by well-known Duluth architects of the time such as Oliver Traphagen, W.T. Bray and I. Vernon Hill. Endion is an enduring legacy of one of Duluth’s most prosperous eras as a center of industry and commerce in the great Northwest.

34 DNT Extra • August/September 2019

218-940-9274 915 John Ave., Superior, WI OPEN Monday - Saturday 10 - 3 Afterlife is a locally owned electronics recycler in Superior, WI Check out our website www.aegraveyard.com for a list of electronics we accept for free, prices on other electronics, and satellite events

Chester Park-UMD

By Adelie Bergstrom abergstrom@duluthnews.com

This neighborhood is, quite literally, defined by its two namesakes — Chester Park, and the creek that flows through it; and the University of Minnesota Duluth campus.

The district is one of competing landscapes, stretching roughly from Chester Creek to about Wallace Avenue and from Arrowhead Road to Fourth or Eighth streets, depending on where you find yourself.

Woodland Avenue serves as a main shopping district, anchored by the Mount Royal Shopping Center and the BlueStone development. Other retail and businesses are found along Eighth Street.

Only part of Chester Park itself actually lies within the neighborhood. The park was one of Duluth’s first, founded in 1891. It was named after Charles Chester, a homesteader who lived on a land claim here as early as 1857.

The park lies along Chester Creek and originally ran from what is now Skyline Parkway to Fourth Street between 14th and 18th avenues east. In 1920, Chester Park expanded above the parkway with land bought by the Duluth Ski Club, which used the park for ski jumping tournaments until 2005, according to the city. The park’s historic ski jumps came down in 2014.

Meanwhile, UMD’s roots lie in the Duluth State Teachers College on Fifth Street at 23rd Avenue East.

In 1947, the school became a branch of the University of Minnesota system. That same year, the city set aside 160 acres from a former dairy off Woodland Avenue for an expanded school, and the first building on the “upper campus” broke ground in

December 1948.

Today, the campus is 244 acres, with an enrollment of about 11,000. Many of those 11,000 students live in the neighborhood, along with students from nearby St. Scholastica.

The neighborhood is a mix of single-family homes as well as many rental properties — a mix that sometimes has led to clashes among neighbors. The BlueStone development added some student housing, and UMD is planning a new 10-story dormitory to open in 2021.