3 minute read

Lost to history

While some Duluth neighborhoods no longer exist in name — absorbed by a next-door neighborhood or rebranded like Lincoln Park (formerly known as West End) — others have been wiped out to make way for highways, parking lots and buildings.

By Jimmy Lovrien jlovrien@duluthnews.com

Essentia Health’s current footprint within the Central and East Hillsides, an area city leaders now call the “Duluth Medical District,” was once home to Duluth’s first mansion district: Ashtabula Heights.

People flocked to Duluth in the late 1800s as the shipping, logging and mining industries emerged, and the wealthiest among them built large Victorian homes between Second and Sixth avenues east and First and Fourth streets. Some of the houses were designed by famed architect Oliver G. Traphagen, who was also behind some of Duluth’s most recognizable buildings — Central High School, Chester Terrace and Munger Terrace.

On June 15, 1907, The Duluth News Tribune described Ashtabula Heights as “one of the foremost residence sections of the city.”

As for the neighborhood name, that was carried over by its original residents, many of which were business leaders from Ashtabula, Ohio, a port city on Lake Erie, according to Tony Dierckins’ book “Lost Duluth.”

By 1914, Ashtabula Heights had lost its luster and Duluth’s elite began moving east.

“The social center of Duluth has left its former home and is now hovering along the shores of the lake from the East End to Lester River and out to Woodland,” The Duluth News Tribune wrote on Feb. 9, 1914.

But Josiah Davis (J.D.) Ensign, who served as a district court judge, St. Louis County Attorney and mayor of Duluth, remained in his 504 E. Second St. home.

He was one of the few that stayed in Duluth long enough to watch the city evolve from a place where “Everyone should bring blankets and come prepared to rough it at first” as the Duluth Minnesotian, the city’s first newspaper, advised in its 1869 debut issue, to an industrial giant with gleaming buildings in just over four decades.

“How few of the early residents of the first seat of beauty and fashion have survived the change and lived to see their fondest hopes realized,” the News Tribune wrote in 1914. It added later, “(Ensign) can now fix his uninterrupted gaze on what his dreams depicted, West Superior, with her many and magnificent docks and elevators, the beautiful white way. Superior bay and the hundreds of boats, docks and mills, hotels and business blocks, and the dream of many Duluthians now dead and gone — the United States Steel corporation’s plant,” the News Tribune wrote.

Ensign’s Victorian home has long been demolished, and Essentia’s Miller-Dwan Building now occupies its space.

Since St. Mary’s Hospital, Essentia’s predecessor, opened at 404 E. 3rd St. in 1889, the hospital has slowly expanded its footprint into what used to be Ashtabula Heights.

In the late 1980s, one of the neighborhood’s last structures, the Ashtabula Flats apartment building, was leveled for an Essentia parking lot.

But one of the old Victorian houses still stands today,

Dougherty Funeral Home, the former Henry and Alameda Bell house designed by Traphagen in 1887, still stands at 600 E. 2nd St., but its characteristic turret and other details have been lost.

Slab Town and Below the Tracks

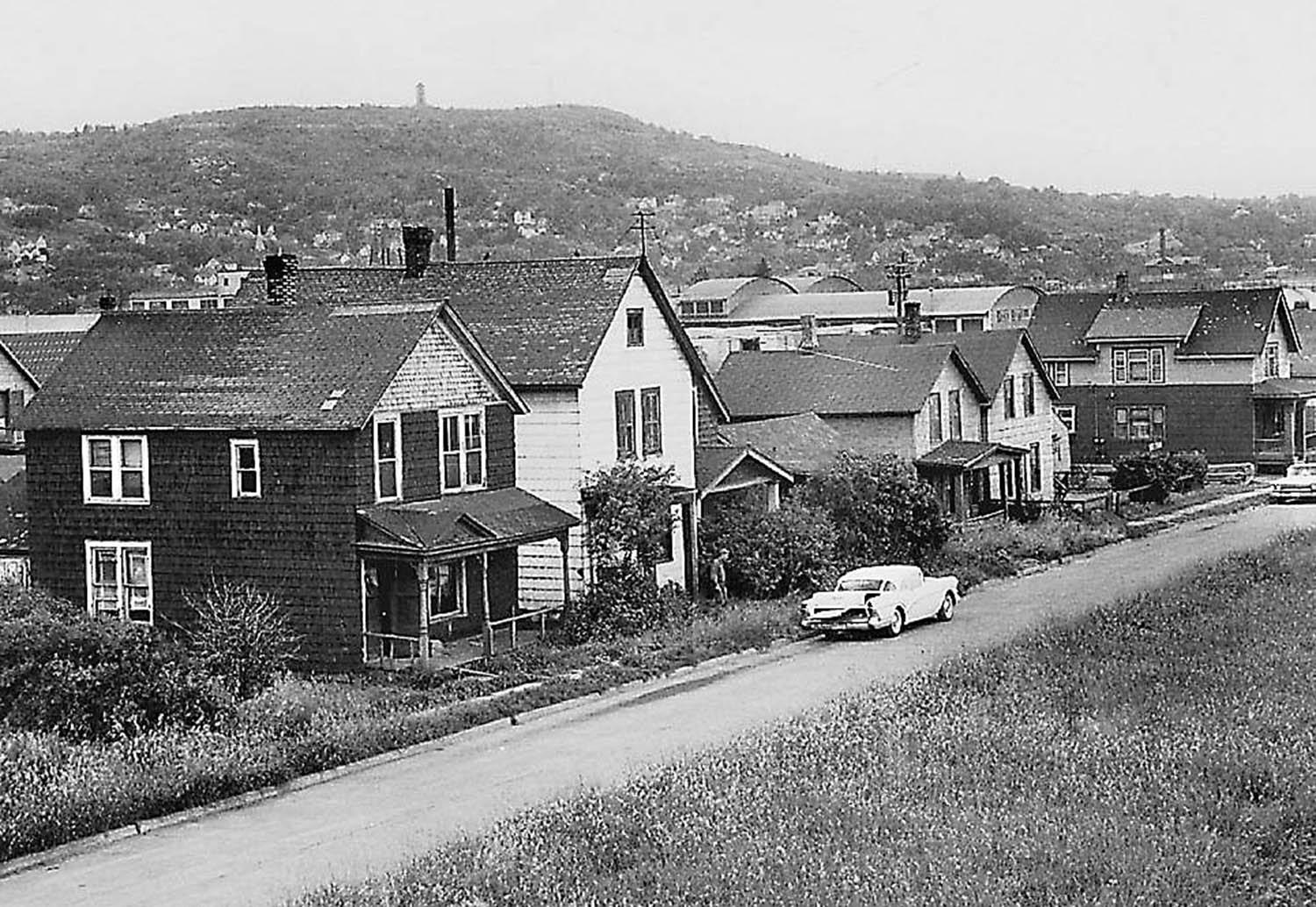

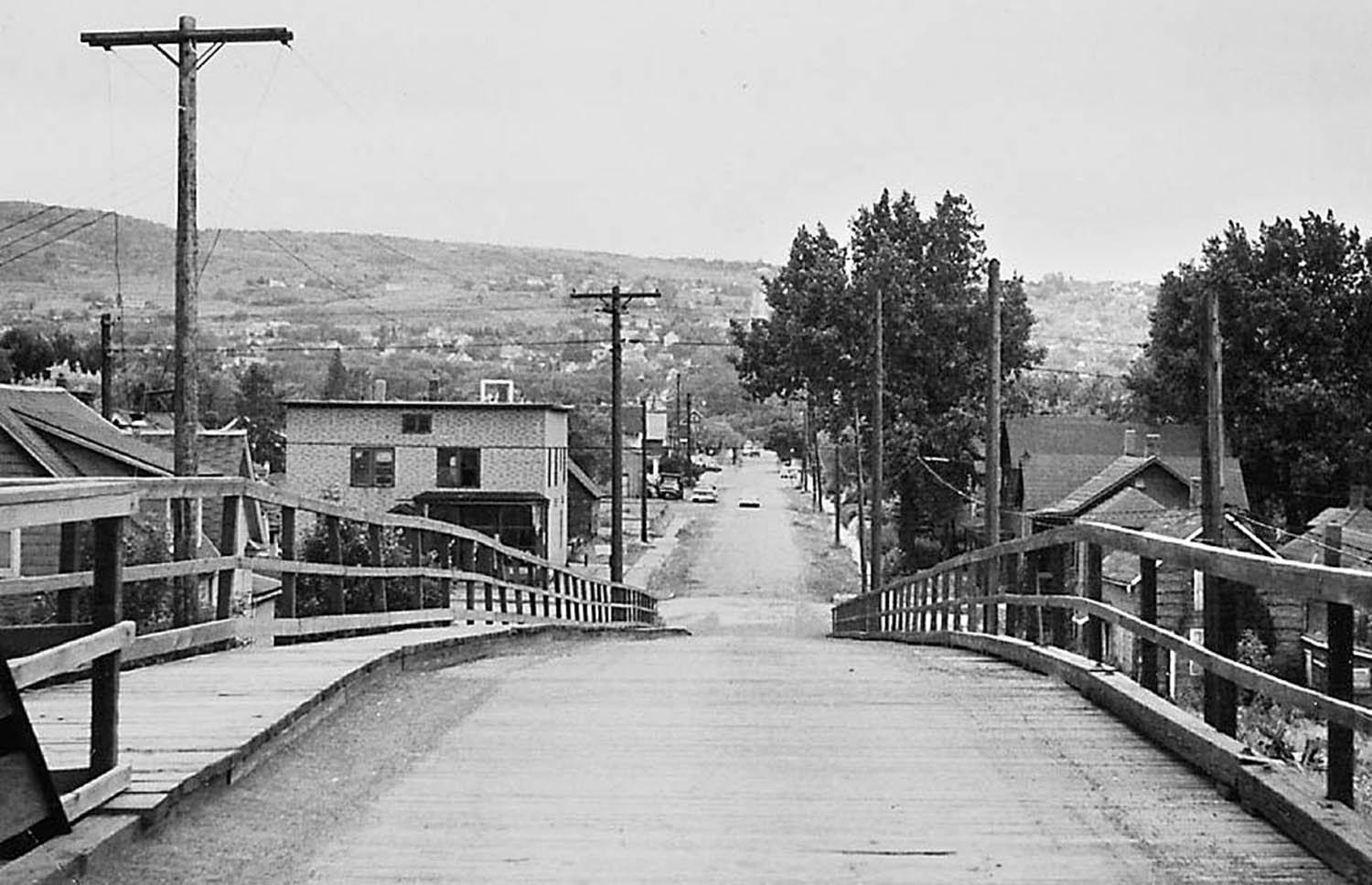

More recently, two former adjoining west Duluth neighborhoods were bulldozed to make way for development.

In the last half of the 20th century, the 232 houses that made up Slab Town and Below the Tracks neighborhoods between 21st and 27th avenues were replaced by the main post office, Western Lake Superior Sanitary District and Interstate 35, according to a 1998 News Tribune article highlighting an annual reunion for the neighborhoods’ former residents.

In the late 1800s, Slab Town and Below the Tracks were settled by immigrants who worked in the nearby factories.

The lumber industry dominated Slab Town, along the St. Louis Bay where WLSSD now sits. Logs would float down the river to the neighborhood’s waterfront mills where they were cut into lumber.

According to the News Tribune’s 1998 article,

Continued on page 46 workers threw the rough slabs from the logs’ exteriors back into the river. Residents then removed the slabs from the water, piled them up on shore to dry and burned them to heat their homes. The area came to be known as Slab Town.

Further inland, where the main post office now sits, was called Below the Tracks, a reference to the railroad tracks that still run parallel to Michigan Street.

“People don’t realize how many homes were down there where the post office and WLSSD are now,’’ Dick Yagoda, a former resident and police officer, told the News Tribune in 1998.

“It was a working-class, blue-collar place, just a plain old good neighborhood.”