5 minute read

From many towns, one Duluth

By Adelie Bergstrom abergstrom@duluthnews.com

From a handful of scrappy townsites founded in the 1850s to the industry and commerce that drove the city’s growth into the 20th century and beyond, Duluth went through booms and busts as it stretched out to the city hugging the Lake Superior shoreline that we know today.

While the name Duluth originally described a settlement at the base of today’s Park Point, the city’s true story begins in its farthest western reaches — today’s Fond du Lac neighborhood.

‘Bottom of the lake’

For many years, French voyageurs used the name Fond du Lac — “bottom of the lake” — for all of what we know as today’s Twin Ports.

French explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, passed through the area in the autumn of 1679 on his way to the Dakota village at Mille Lacs Lake. His goal? To set up a fur trade agreement with the native Anishinaabe and Dakota who’d been in the region for centuries.

The Anishinaabe traveled through the region regularly, but they had no permanent settlement at the start of the 19th century. According to “Duluth’s Legacy, Vol. 1: Architecture,” published by the city in 1974, it was John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Co. that established a trading post at today’s Fond du Lac.

Fond du Lac was settled in about 1820 as the first permanent native settlement in the region. By 1835, the Rev. Edmund Franklin Ely had built a mission school here before moving to La Pointe, Wis., and then back to Superior in 1854.

The fur trade dried up by the mid-1850s, and soon a new group of speculators and adventurers arrived, excited about the copper and timber resources.

In 1854, the local Anishinaabe entered into a treaty with the United States, ceding ownership of their land in Northeastern Minnesota. The Treaty of La Pointe opened up the area for non-native settlement.

The original town of Duluth was platted in 1856 and incorporated the next year. Most of the town was at the base of Minnesota (Park) Point, south of today’s Aerial Lift Bridge.

George Stuntz, who arrived in the early 1850s, built the first building on Park Point — a trading post and later a block house and pier, according to the 1977 book “Duluth: Past to Present” by Mary Lou Germ. George Nettleton and his wife, Julia, soon followed. After the Treaty of La Pointe was reached, Nettleton built a sawmill.

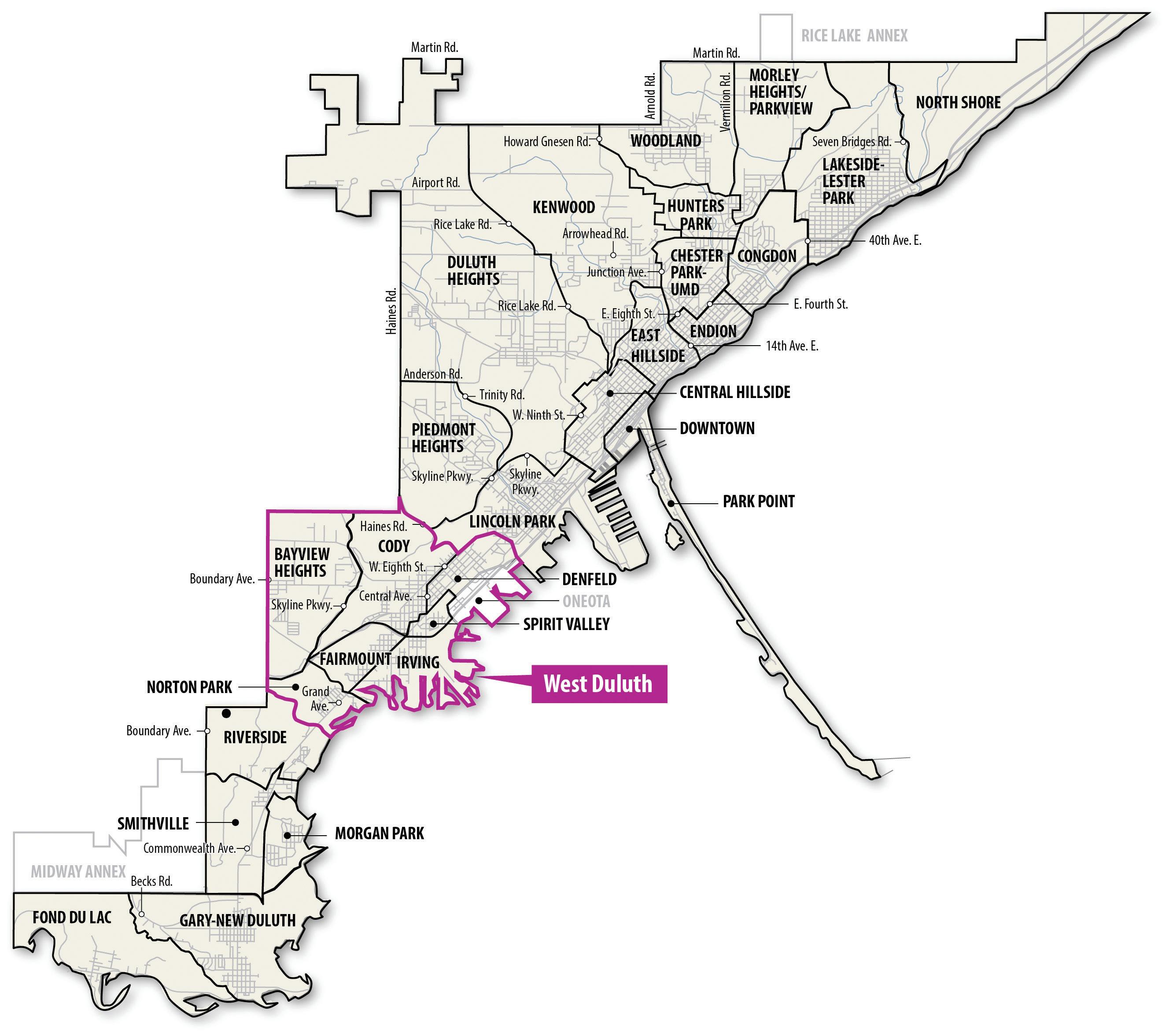

Eleven townsites, including Duluth and Fond du Lac, were established by the end of the 1850s, though an economic panic in 1857 caused many to leave, and it would be another decade before the population began to recover.

The other townsites — from west to east, Oneota, Rice’s Point, Fremont, North Duluth, Middleton (later Park Point), Cowell’s Addition, Portland, Endion

Continued on page 8 and Belville (later Lakeside) — each had hopes of becoming the region’s epicenter.

Western Duluth

In 1854, Ely, now living in Superior, crossed St. Louis Bay and founded the town of Oneota. Oneota was the site of St. Louis County’s first public school, built in 1860. By 1870, Oneota had a population of 500 with two sawmills, a store, a hotel, a church, a furniture store, and eventually a shipyard, according to Germ’s book.

Oneota became part of the new town of West Duluth in 1888, growing to 6,000 residents by 1892 as the Duluth, Missabe and Northern Railway extended through the town. West Duluth itself joined Duluth in 1894.

Just downriver from West Duluth was Rice’s Point, and it was here that the first home on the Duluth side of the bay was built in 1855. The town of Rice’s Point was platted in 1858 and included all of the land back to the Point of Rocks.

Rice’s Point had hopes of becoming St. Louis County’s seat, changing its name to Port Byron in an effort to sound more sophisticated, Germ wrote, but the town lost out to Duluth, and Port Byron soon reverted to its original name.

Eventually, Rice’s Point became a center for sawmills, with as many as 13 in operation at one point, Germ said in her book. Today, Rice’s Point is still a center for much of Duluth’s industrial activity, with its grain elevators and rail tracks along the bay.

Fremont, once between Rice’s Point and Park Point, never got the chance to join the eventual city of Duluth. Before the Duluth Ship Canal was created in 1871, the harbor was filled with a number of floating islands made up of driftwood and vegetation, held in place by moorings, according to Germ’s book.

After the canal was cut, the water currents broke part of Fremont away from the shore and sent it floating into the canal. Residents attempted to chase the floating land by boat, but it disintegrated upon hitting Park Point.

Eastern Duluth

The town of Belville preceded today’s Lakeside and Lester Park, being platted in 1857. Within a few years, the town was renamed New London after broker Hugh McCulloch, who had spent a number of years in the English capital, bought the land.

According to Germ’s book, McCulloch gave the town’s streets a decidedly British flair, with names such as Pitt, Cambridge, Gladstone and the town’s main thoroughfare — London Avenue, or today’s

London Road.

George B. Sargent, an agent for wealthy financier Jay Cooke, bought the land from McCulloch and organized the Lakeside-London and Lester Park additions in 1886-87. The town of Lakeside joined the city of Duluth on Jan. 1, 1893.

Closer in, Endion’s suburban lots were platted in 1856 and grew from land claimed by the Hon. William Wallace Kingsbury, delegate to the Minnesota Territorial House of Representatives and later a member of Congress. Endion was annexed to Duluth in 1870.

Portland was platted in 1857 between about Seventh and Ninth avenues east, running down to the lakefront, though it grew slightly wider over the next decade. Unlike other early settlements, Portland’s streets were laid out to align with compass directions rather than on a diagonal. When Portland was annexed into Duluth in 1870, its streets had to be realigned to fit with Duluth’s, which meant lots had to be resettled and homes had to be moved.

Washington Avenue, today just a stub of a street attached to Seventh Avenue East below First Street, is the only remnant of Portland’s original street plan. The Portland name also survives with Portland Square Park in today’s East Hillside, and with the Portland Malt Shoppe on Superior Street.

Central Duluth

In addition to the original town of Duluth, today’s central Duluth included the settlement of North Duluth, roughly analogous to today’s Central Hillside, and Cowell’s Addition, which includes most of today’s Canal Park.

Minnesota Point beyond the original town of Duluth was known as Middleton. In 1875, residents elected to maintain a separate town from Duluth and began to call the town “Park Point,” according to the Park Point Community Club.

In 1881, the village of Park Point was established. In the meantime, Duluth had lost its city status following the failure of early financier Jay Cooke’s company, on which the city had staked much of its finances, Germ wrote.

When the city regained its charter in 1887, Park Point refused to join the city until a bridge was built to join Park Point with Duluth, though with a promise from the city, it acquiesced and joined Duluth in 1889. There was much talk, but the bridge didn’t become a reality until 1905, when what would later become the Aerial Lift Bridge opened.