voices about us

Voices is a student-run literary magazine of the Duke University School of Med icine. We publish varied forms of creative expression from the medical communi ty, and welcome submissions from patients, students, healthcare providers, em ployees, families, and friends. Our goal is to publish a range of unique voices in the healthcare system. We hope that as you read through the pieces published in this issue, you will be inspired to submit something as well. For more information, please visit sites.duke.edu/voices/submissions. Send all submissions to voices@duke.edu.

letter from the editors

In the spirit of sharing our most authentic and transparent selves, we bring you new voices from our community. Some will say that our anxieties only exist in our minds, and—when life becomes unmanageable—that idea may hold partial merit in our anxious excesses. At the same time, many of these worries are rooted in reality. Aging ravages the body while stripping the superficial; our bodies are not always respected as our own; proximity infects us even as isolated distance pries sanity away; pets receive first-class spa treatment and urgent care, while access to life-saving vaccines and procedures remains tenuous. From these realities of life, the mind can explore infinite possibilities. While contemplating these burdens, we encourage you to be kind to yourself, to be patient with yourself, to be honest with yourself and about yourself. In this issue, our authors examine difficult truths. Sometimes—in spite of good inten tions—we cause harm. Sometimes— in spite of good intentions—we are harmed. At the end of the day, we hope that the good will outweigh the bad and that calling attention to the imperfections will be the first step in justice, in becoming our best selves.

As always, we thank the Trent Center for Bioethics, Humanities & History of Medicine for their unwavering support and valiant efforts to save our best selves (“to save our souls” per our own Dr. Baker) before the daily grind of hospital life— whether as a patient or as a provider—burns out the light. We hope you enjoy this issue and invite you to send us your thoughts, questions, and new submissions at voices@duke.edu. Please also inquire about joining the VOICES editing team!

Your co-Editors-in-Chief, Lindsey Chew, Devon DiPalma, Emily Hatheway Marshall, and Linda Li

LAYOUT DESIGN & GRAPHICS: Lucy Zheng

LAYOUT DESIGN & GRAPHICS: Lucy Zheng

takotsubo

No, not like an elephant on my chest, I tell them. It’s a different weight pressing me onto the examining table as we eavesdrop on the sturdy slosh-slosh of my hidden heart.

From one to ten, they ask me, the nurses with their kind, busy hands daubing cold gel, fastening a sagging tangle of wires.

Faster, steeper, sweating, panting, I walk and walk for them.

From one to ten, they ask again,

as if there were a calculus for measuring the burn from wildfires of new fear, the heft of longing for return to some safe world that maybe never was, the stone of sorrow in a body grown this old alone.

The doctor says, “You know, there’s a reason we have words like heartache and broken heart.”

FlorenceNashwasaneditorandresearchanalystat

DukeUniversityMedicalCenterandledthepoetry workshopforDuke’sOsherLifelongLearningInstitute for16years.inseparable

MarieChengisstudyingcomputerscienceand biologyatDukeUniversity,withhopesofpursuinga career in bioinformatics.

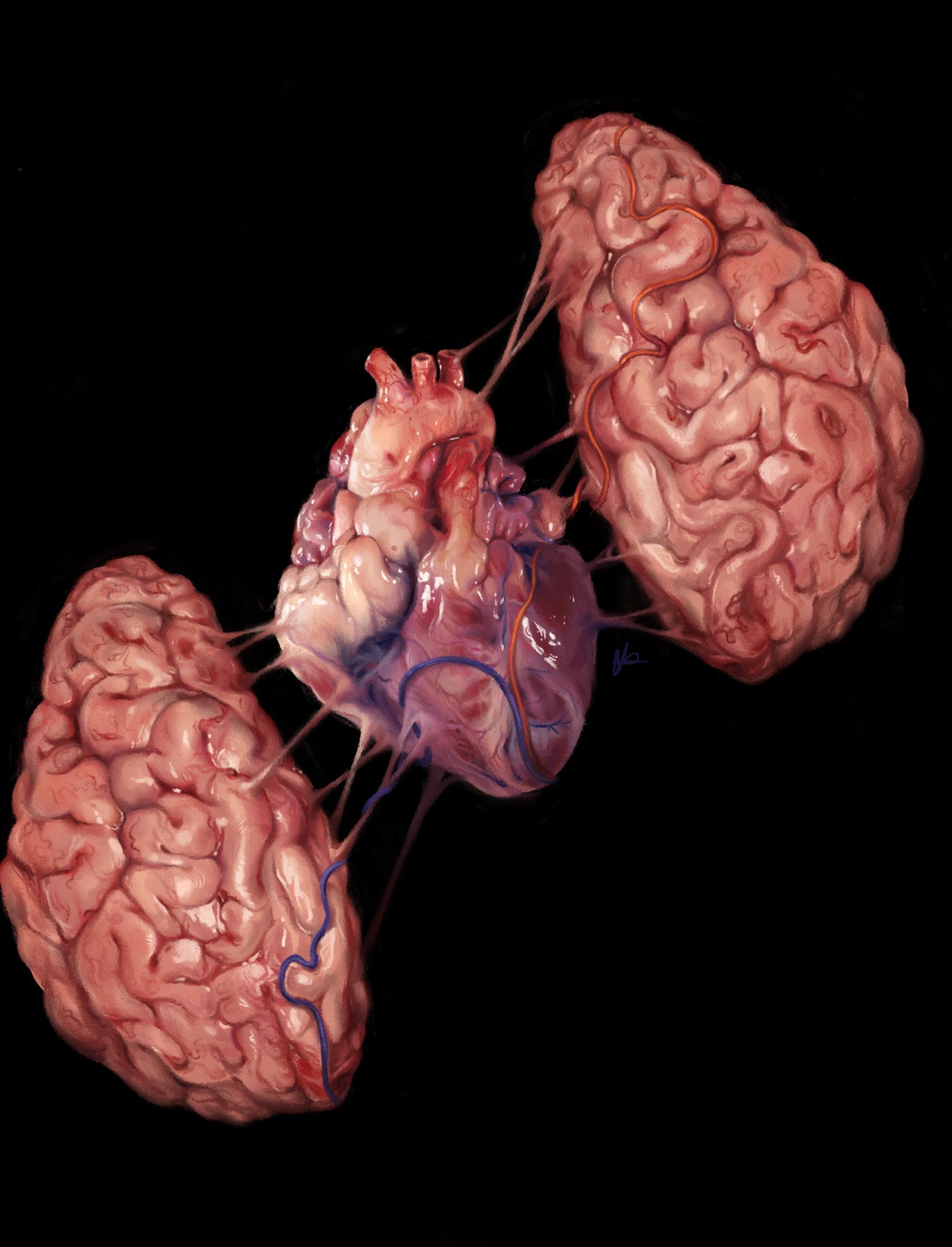

This piece reflects on our understanding of human emotion and its elusive origins. It underscores the tugging between the physiological and social dimensions of emotion and their inseparable nature. Two small wires attempting to blend into the organic shapes serve to question the emerging strides of biomimetics—how do we recreate what we cannot understand?

(medium: digital illustration)

i wish i was a man but only in the way

that a man gets to be a person

contentwarning:men,s*xualharassmentandassault,non-consensualactivity,suicidalideation.

the doctors ask us, “some patients have vaginal, anal and oral sex. what about you?”

crazy how i don’t like to think about my sexual encounters much. when i do, i'm inevitably faced with the reality of coercion into sex with men, relentless in exer cising their power over me.

they heard me say “maybe next time,” but wondered why i didn’t seem so into it. asking over and over until no was no more. over and over until it wasn’t asking anymore. over and over, my body be came a rag doll.

perceptions of penetrative sex vary so widely. me, i experienced fear of sex be fore really knowing what sex was. before ever wanting to kiss someone, i knew the cruel reality thrust upon persons boxed into the category woman. don’t walk home alone. watch your back for stalking strangers. walk facing traffic to deter kid nappers. yet, statistically it probably won’t even be a stranger who harms you. it’ll be someone you know. someone older, more powerful— in physicality and matu rity. someone they will believe over you. someone, you would never challenge. you can never be too careful. can’t go to that sleepover; they have older brothers. can’t go to that party. can’t live one mo ment without fear of death, mutilation, acid attacks, assault, hurt.

...my body became a rag doll.

not for one moment can i escape wom anhood. to be a woman is agony, is dis tress. on top of complex reproductive sys tems that completely change our bodies, minds, and experiences, the potential for harm committed against us by the people we love is so high that no woman reaches adulthood unscathed. it’s disgusting that men are allowed to be like that. they feel entitled to be inside of you, to exert their power. because that’s biology, right? penis enters vagina? because that’s how we make more humans. that’s the standard of normalcy. it seems that people only use biology in the debate over societal constructs when women and gender-non conforming people have something to say. a manipulation of biology against women, to benefit men. “men are just like that. their testosterone inevitably dictates violence, uncontrollable urges.” even in kindergar ten: “what do you expect when he wants to play with the toy you brought for show and tell? he pulls your hair to show he likes you.”

their shock is a striking contrast: “what? you’ve been on your period for three months straight due to birth control com plications? you’re having severe cramps that make you puke and disrupt your dai ly function? well, isn’t that just what the female body does? stacey’s been on her period for FIVE months and she’s not com plaining, so why are you slacking off? we won’t pay you to stay home watching tv.” come and get your grandpas, dads, brothers, and boyfriends. the ones who won’t take no, who demand my number, who can’t accept rejection, who can’t say “have a nice day” and then go about theirs, who expect to be satisfied— the center of attention. instead, they should be kneeling at our feet.

it’s fun walking home alone at night. when men inevitably cat call, i can do nothing— or i can tell them off and watch my back all the way home. i’m always looking for witnesses in case of an am bush on the way to work, clearing my throat in case i need to scream, using a phantom number so i don’t have to give strange men the real one but it’ll still ring if he calls right away. i love worrying about men i don’t know, about men i do know, and potential threats to my physi cal safety. because somehow, they’ll ask what i was wearing and it’ll be all my fault. why can’t i just exist as a person. men get to do it all the time, blend into their humanity. but me? sex appeal > body > face > servitude > cooking ability > mon ey > everything but my personhood. be cause i’ve been labeled a woman, not a person. someone to be deflowered, to birth babies, to raise said babies. for oth ers, not for myself.

every time you did nothing when your shitty friend said something disgusting to a woman, thrust his hips at her, tried to put his hands on her. every time you nev er asked and just assumed she “wanted it” and that “she seemed into it.” your dis gusting little friends aren’t good people. you’re not a good person if you contin ue being friends with people you know have committed terrible acts of violence against the women in their lives. at the very least stop listening to chris brown?

you didn’t give it a second thought as you went on your merry way. but she thinks about it all the time, she has no es cape. it’s not some imaginary ghost un der the bed that hurts us: it’s you.

i just want to exist as a person, but i have been confined to the prison that is a woman’s body. there are questions, but i just want it to stop. remember to wear protection, don’t forget to pee right after or i’ll get a UTI. don’t forget birth control so he can hit it raw. this is actually ruining my life and making me want to die, but at least he’s getting something out of it. i just want to be a person in the way a man can be both person and man, but can

also choose to be just a person or just a man. his gender is not tied to his person hood, but mine is. so yeah, i wish i was a man. but only in the way that a man gets to be a person. sometimes, i get all nihilistic thinking about how much destruction men cause, and the ease of the world they walk through. but then, i think about when men feel safe enough to cry, when they love in a fearless way, when they become accomplices in breaking this painful cy cle. i remember the men in my life. i re member the times he drove a long way to drop something off. i remember how he kissed me and it felt just right when he held me tight. i remember what it’s like to love him and to be loved by him. when i remember, i crack a smile. but it doesn’t matter, because before i can even enjoy the moment, it’s de stroyed by the memories.

Ifyouorsomeoneyouknowhasbeenaffectedbysex ualviolence,it’snotyourfault.Youarenotalone.Help isavailable24/7throughtheNationalSexualAssault Hotline:800-656-4673,rainn.org.Wecanalsoallhelp preventsuicide.TheNationalSuicidePreventionLifeline provides24/7,freeandconfidentialsupportforpeople indistress,preventionandcrisisresourcesforyouor yourlovedones:800-273-8255,suicidepreventionlife line.org

fall 2022, vol. 12, issue

connections

MargaretWeberisathirdyearMD/PhD studentatDukeUniversitySchoolofMedicine.

MargaretWeberisathirdyearMD/PhD studentatDukeUniversitySchoolofMedicine.

This piece, titled "Connections", is a reflection on a conversation with a patient about his life, his relationships with both biological and chosen family, and his experience navigating a double hip replacement. The conversation was influ enced by the COVID-19 pandemic and the deep longing for connection that social distancing created. (medium: oil paint and wire on canvas)

Death

Takes so much away from you. You move on, Life takes a new turn. You look at the sky, And he's missing it: The beautiful way That the sun shone today.

death

How he missed this morning, And the mornings after that–That's all that the sky tells you. The smile on you Reminds you of your betrayal, For Happiness should have lost Its way to you.

You moved on, And yet, not quite. The way he crinkled And wrote you poems; His laughter, All reduced Memory.

crinkled his nose, poems; his anger, his desires— reduced to . . . one word, Memory.

It's unfair, That a lifetime of dreams, pain, Suffering, joy, laughter Are reduced to just that, One word.

We weigh our griefs Before taking your name: Who gets to mourn you today, And who gets to be the rock. The ball of blame shifts focus, And yet, no closure.

hand study master copy

StevenZengisathirdyearmedicalstudentatDukeUniversity SchoolofMedicinewhoisinterestedinplasticsurgery.

Thispieceischarcoaldrawingthathighlightshandanatomy. Itisamastercopyfromanunknownartist.

You go to his room, You smell his favorite tee. You try his phone. He is just not there. No, you don't miss him, Because you'll never stop Looking for him.

fall 2022, vol. 12, issue 1

doctoring in the public hospital

Each day on rounds I see sorry sullen sick-wracked souls founder it seems in seas without fathom, freighted with cargo I cannot bear. They turn to me like pilots to the light. But they misread the depths, they do not reckon distance to the shore.

I remember that Irish monks of old pushed off in unruddered leather boats, impelled against the open sea into the Hands of God. What did they take with them? Loaves? Fishes? Some sea-dark wine? An oozy skin hull thrust against the press of sea; an oar; a habit; a heart lifted by piety or faith or foolish hope.

That not theirs but the rough-backed sea’s will be done. To be one with the hunkering spray and gale; the curded clouds; the high thin sun; the petrels and shearwaters; the ravenous clear waters; the inner tick of faith and time. If land came to meet them, it was as benison, the triumph of trust and luck.

My patients set to sea alone; not I nor anyone goes with them; they cast off without chart or compass, believing that the mounting clouds mirror only yesterday’s squall.

The boat rises and twists. Water laps the gunwales. Is that a blast of lightning? Of thunder? Or just the mounting riot of the waves?

F A Neelon

Dr.NeelonretiredfromDukeUniversityin2002after40yearsinthe DepartmentofMedicine’sdivisionsofGeneralInternalMedicine andEndocrinology/Metabolism.

the decolonization of global health

The idea of decolonization1, the dif ficult process of pulling back the curtain on colonial paradigms, is gaining traction in the wake of multiple landmark events, from the triumphant protests at Standing Rock to the murder of George Floyd, as well as thanks to the underlying, ongoing work of BIPOC folks who constantly un dermine colonization. Every inch of our mainstream reality, particularly in North America (aka Turtle Island2) is the result of colonization. That may be hard for us to grasp, as we are the metaphorical fish swimming in water without realizing we are, in fact, surrounded by water. But the way we view education, gender, religion, law and police, resources, nature, chil dren, elders, family units, food, work, and more have all been touched by coloniza tion, the imposition of a particular set of Anglo-European beliefs.

Healthcare is no exception. There may be pushback to the idea that healthcare could possibly be ‘colo nized.’ Sure, something like art could be colonized because art leaves so much room for interpretation. But healthcare? Medicine? In a culture devout to science and its perceived objectivity, healthcare couldn’t possibly be the result of biases, trends, and popular opinion, right?

Wrong.

First off, much of our ‘scientific’ knowledge of human anatomy itself is a direct result of colonization. Not just the macro-scale colonization of Christopher Columbus landing on Turtle Island, but even the micro-scale colonization of socalled doctors experimenting on and ex tracting from non-white bodies. From the infamous ‘scientific’ experiments3 of the Holocaust on Jewish bodies to the Tuske gee Syphilis experiment4 to the robbed cancer cells of Henrietta Lacks,5 much of what we consider medical breakthroughs

were the direct result of colonization and white supremacy. The justification that Aryan lives could be saved at the cost of non-white bodies is colonization 101. What’s more, much of “western” medicine is stolen, appropriated, uncred ited learnings from other cultures. While simultaneously delegitimizing shamanic, witch-doctor, bruja, curandero, indige nous medicine as “woo-woo,” “hippie,” etc., western medicine at the same time steals from these cultures and rebrands their sacred, traditional medicines. Many pills, tablets, and other medicines on our shelves originated as plant medicines, before we began to artificially synthesize potent medicinal molecules that existed in nature.

In reflection, we know that much of the healthcare we receive in modern day is, in fact, thanks to colonization and lost lives. That is the foundation of many medical procedures and medical care. So how do we decolonize hospitals, medi cine, treatment, death, and more?

One angle to decolonizing medi cine and global health is to first acknowl edge that the white straight male body is not a baseline for all bodies globally. The idea that testing our medical hypothe ses on Caucasian male bodies makes the findings applicable to all people every where is a myth. There is not one ‘food pyramid’ that makes sense for all human bodies (we love the hierarchical pyra mid structure in western society, don’t we? Very feudal/caste when you look at it closely). Humans co-evolved with their ecosystems; some human bodies that coevolved in herd cultures have a higher tolerance for lactose, while other societ ies have a higher tolerance for red meat. Not everyone digests alcohol, fruit, or

fall 2022, vol. 12, issue 1

carbs the same way. The white suprema cist idea that the white body, particularly the white male body, and its medical find ings can be copy-and-pasted onto dis tinct bodies and cultures is in itself based in a colonial, white supremacist mindset. We know that female bodies endure ra diation completely differently than male bodies. These are proven facts but are seldom linked to colonization as the rea son for these discrepancies. Additionally, the very idea that there is a sex binary is a western myth, and its widespread cultural adoption is a direct result of colonization. We know, scientif ically, that intersex people exist, that not every human body is birthed into the world with either XX or XY chromosomes. We study these ‘anomalies’ in high school biology as problems to be fixed, rather than third, fourth, and fifth sexes. We can’t look to nature to support our quasi-Chris tian belief that there are only male and fe male bodies, either. Frog and turtle eggs change sex based on water temperature; seahorse ‘males’ incubate and ‘birth’ off spring; some fish change sex throughout their lives. Bacteria and fungi are sexless. Self-pollinating flowers are “both” male and female. The idea that everything is either a boy or girl did not exist in all cul tures everywhere before European colo nization. For example, many indigenous cultures held special reverence for Two Spirit folk, those who were deemed to carry both the masculine and feminine spirit within them. Many of these Two Spirit people were highly respected and held powerful, spiritual, and ceremonial roles in their communities.

Then there’s our prioritization of white bodies over bodies of color in medicine everywhere, both in preventa tive care and healthcare. In fact, I’d argue there’s a prioritization of pet health over bodies of color in medicine. After living in rural Panama for two years, I realized that

most dogs and cats in the United States go to the doctor for vaccines and check ups more than most folks ever go in some developing countries. While part of that is due to their medicinal knowledge and access to herbal medicine, the amount of money we spend on pet health in North America is concerning considering how many people still lack access to mosquito nets, clean drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, and consistent nutrients. While dog treats now feature turmeric, there are people dying of hunger. This tells me that we are more in tune with animal health than the health of our brothers and sis ters. While care of our non-human kin is essential to global harmony, the idea of performing life-saving surgery on a pet bunny seems like a grossly misplaced use of resources in a globally connect ed world. Aside from pets, we still see that white bodies are less likely to live in chemically toxic areas (think: Flint, Michi gan) and that people of color have high er rates of infant mortality. Food deserts on Turtle Island correlate to communities of color; in fact, the most accurate way to predict how close someone lives to a coal plant is by looking demographically at skin color. Preventable deaths and pre ventable illness are occurring because there has not been enough emphasis on healing black and brown bodies. And healing those bodies cannot and will not look identical to healing white bodies, if we have even mastered that. Af ter working with the indigenous Ojibwe of the Red Lake Nation, it is apparent that a hospital offering true healing services to the Native population should include such practices as regular smudging in hospitals, prayer, boughs of dried cedar and other medicines, access to saunas or sweat lodges, and translators for Ojib we-speaking elders. Teas and other med icines should be in stock, just as aspirin and morphine are on hand. Hospital cafe-

teria food must include Red Lake walleye, foraged berries, and other local cuisine that their bodies are accustomed to and evolved for. There must be an aspect of cultural awareness, not just a gesture that doctors and nurses roll their eyes at, but a genuine, respected, ongoing practice. For people to heal, they must feel wel come. They must feel like the Creator can visit them.

What medicine should not look like for black and brown bodies is voluntour ism clinics that ship out to Central and South America, Africa, and other “Third World” countries. As a Peace Corps Vol unteer in Panama, I observed that volun teers were often called into these clinics to be translators. While I enjoyed my time in the Peace Corps, we were never trained or prepared to fill that kind of role. As the doctors themselves didn’t speak the local language, it is hard to imagine they were fully equipped to greet and treat folks of rural areas. While I respect the idea of what they were trying to do, there must be increased preparation for trips like these such that there is local knowledge being acknowledged, used, and respect ed. Professional translators must be on these trips, and thorough research must be conducted before white saviors touch down in rural areas with low access and high poverty rates to pat themselves on the back. At least in countries like Pan ama, there is high respect for authority; having this cultural knowledge, doctors may know that their clients are unlikely to question them based solely on their white coat, and can alter their care to leave more space for questions and de clining unwanted care. There is also a noteworthy aspect of preventative medicine versus the capital istic, colonial, parasitic way that our health care system currently seems to work— cre ate the illness to profit off the cure. We eat so poorly in this country. We live so out of

balance. Precious few of us are able to ex ercise, eat well, connect with nature, and feel a sense of community. These are the things that keep us well. As I once read in Red Lake, “Medicine isn’t healthcare. Food is healthcare. Medicine is sick care.” Modern medicine should look upstream to treat the cause of so many health prob lems instead of just pulling the bodies out downstream. What if the most pow erful medical innovation we could make is to shorten the U.S. workweek? What if the most healing thing we could do is lobby for better, more culturally-relevant food access? What if we have been go ing about medicine the wrong way… the whole time? In rural Panama, few have lost their lives to COVID-19. Perhaps because they spend so much time outdoors with birdsong, breathing clean air, connect ed to their circadian rhythms, practicing subsistence agriculture, consuming what their forest-gardens provide. What if we should be studying that instead of how to drown an entire population in prozac?

Healthcare is not inherently evil. The idea of healing bodies is beautiful and noble. But we must acknowledge that like other aspects of our culture, it is steeped in colonization, from the way we made medical discoveries to the way we continue to treat human beings, all-too dependent on their skin color, weight, ethnicity, gender, etc. Medicine is not one-size-fits-all. The more we acknowl edge and respect traditional medicine, distinct bodies and stories, distinct reli gions and beliefs, and the value and dig nity of a human life, the more people we can bring to healing. s. at the very least stop lis RachelC.BeglinisareturnedPeaceCorpsVolunteerand farmmanagerinLongmont,Colorado.

Toaccessthefootnotesforthisarticle,pleasegoto: tinyurl.com/fall22decolonization

fall 2022, vol. 12, issue 1

Anxiety