voices about us

VOICES is the student-run literary magazine of the Duke University School of Medicine. We publish various forms of creative expression from the medical community and welcome submissions from patients, students, healthcare providers, employees, families, and friends. Our goal is to publish a range of unique voices from inside and adjacent to healthcare. As you read this issue, we hope that you will be inspired to submit your own writing or artwork. Send all submissions to voices@duke.edu.

letter from the editors

RENEWAL brings hope for a new day. As brokenness heals, we emerge good as new—or better. Shattered pieces reconstitute into an even more beautiful creation. Deconstruction clears the stage for reassembly and growth. In this issue, we explore different sides of renewal, find strength in putting the pieces back together, and—as much as possible—leave things better than we found them.

RENEWAL also evokes nature. Day after day, the world goes ‘round. Oceans rise and carve out new terrain. Volcanoes erupt and lay down new land. Forests sustain us and breathe life into creation. The cycle continues even as the individual contributing units change. Once again, we also share the renewal of VOICES as another generation takes on the honor, the challenge, and the privilege of bringing each word, each brushstroke, each inky outline to the community at large. We invite you to turn the page with us. Find the passion and energy to spark your own renewal. Pause to remember why you chose this path and the things that fill your soul. Walk down memory lane and bring your whole self into each space, tragedies and triumphs alike. In doing so, we hope you will find your own personal RENEWAL.

As always, we thank the Trent Center for Bioethics, Humanities & the History of Medicine for their immense support and for partnering with us to host our most recent contest, “RENEWAL.” We would love to print your prose, poetry, or artwork in a future issue of VOICES and welcome your submissions to voices@duke.edu. For more information, please visit our website at sites.duke.edu/voices.

Your co-Editors-in-Chief, Lindsey Chew, Linda Li, Lucy Zheng, Devon DiPalma, & Emily Hatheway Marshall, MD

the magnolias have blossomed

All that’s left is the 90 miles from Tuscaloosa to Meridian. Aged concrete carved into the ocean

of green and dying grass. On each side, Mississippi farmland rolls beside the windows

as I race the GPS in a loaned Toyota and pray God gives the extra minutes back to my grandfather. Ponder how to throw borrowed sand back up his hourglass. The sign flies past: Welcome to Mississippi

a shrinking speck in the side mirror. Ahead, more flat. More miles of dry fields and sunbaked soil.

Too hard for the VA to dig you a grave, I think, so you can’t die. And when the sign grew larger in the windshield

after the funeral, I figured that somewhere in the grass were the bullets the army shot at the sky.

The same ground that once sprouted cucumbers behind his mother’s house. Grass he taught me to cut with the riding lawnmower

because a car wasn’t too different— cut around the patches of cabbage and okra. Carefully. Years back, there were peas.

But the cucumbers are what I remember most: massive, more prickly on the outside, more green than the box of seedless pities I find in Aldi

months later; ill-stricken baby carrots at best roll back and forth in the cart. Perhaps the soil was too wet or acidic.

Or in my case, salty— too many tears still in the ground. Which is probably what killed my azaleas—

the magnolias are blindingly white.

excerpt from an end-of-life spiritual guide for rocks

KathrynHenshawisathird-year medicalstudentatDukeUniversity School of Medicine.Without

I found beauty in the tragedy of my blurring to sand. We become more like each other. A sparkling sheen of specks of one-time crystals.

Together, we are her metamorphic vessel. We rest around her rhythmic surge. Our sedimentary surface smooths her thrashing fizz into foam.

She mills us into one. Our ashes are her fairy-dust fencing.

I do not call it death, when I realized I was the ocean.

forgotten remedy

HannaVargaisasixth-yearPhDCandidate inEnvironmentalEngineeringatDuke University,withapassionforrenewable energy,sustainabilityandproblemsolving.

Physicians frequently prescribed the "sun and sea" for patients suffering from illness. Escaping from the polluted city to the seaside or a small mountain village improved physical symptoms, while also healing cognitive burdens over the centuries. Nature's rejuvenating power remains, although modern society often neglects it.

tempest or malevolence, time’s pleated tide dulls the stone.

alchemize

HalleAndersonisasecond-yearDoctorofPhysical TherapystudentatDukeUniversitySchoolofMedicine withaninterestinholistichealthandtheintegrationof EasternmedicalphilosophieswithWesternmedicine. To transmute dark to light. To bring light to dark. To surrender. To heal. To become. This work captures the transmutable nature of all energy on Earth—how air flows like water, water carves out canyons from dirt, and our bodies inevitably return to the ground that provides us with sustenance. Life is as cyclic as the ocean tide, as phases of the moon. The renewal of these cycles heals us from the past and transforms life into new beginnings.

turbulence

JosephYangisasecond-yearPhDstudentin DukeBiomedicalEngineeringwithaminorinliterature, whichhehopeswillnotbeforgotteninfifteenyears.

Fool's gold plentiful as molten sunshine, crowning the morning's wake (the fallow mountain peaks) with sun-Dew—with inspiration, the wind beneath one's feet; alchemy and clear fires await he who casts away his mortal desires to see the sun renewed.

the fearful symmetry of renewal

JahraneDaleisasixth-yearMD/PhDstudentinthe DukeUniversitySchoolofMedicineandMedicalScientistTrainingProgram.

Rest and renewal are often associated with life and growth, but there is a subtle undercurrent of breakdown as well. In Greek mythology, the personifications of sleep and death are in fact brothers. This piece explores how the stillness of rest allows for the slow work of growing and healing, and how this process of renewal is not only construction but also deconstruction.

the foggy bridge

The horizon surrenders to a hazy swell. Neither fearful nor concerned, they walk aimlessly through the chasm until a boardwalk appears, floating amidst the angelic billows.

What is death but only a transition into a world we cannot see, we cannot feel. Still the presence of those who once ventured across the bridge is palpable.

Their footsteps follow with our daily stride, quietly guiding our pace. Echoes of their voice heard in our favorite dreams. Their familiar smell greets us with warmth in the next room.

When the time comes, and the beacon lit on the other side, they are here, hand in ours, patiently waiting to guide us across the foggy bridge.

kintsugi

David Stevens is a medical student at theDukeUniversitySchoolofMedicineanda

Theology,Medicine,&CultureFellowat theDukeDivinitySchool.He told me about the ancient art of kintsugi: “In Japan, They don’t throw out The old ceramics. Craftsmen put them Back together, Piece by piece, Leaving gold dust In the joinery. How curious, to call attention to the brokenness. Fragments fused with gilt and lacquer: sharp shards Forever frozen in the cast of their undoing.

So, too, I carry the remnants of breakings. The hitch in the stride, the scar on the chin. The accident opens a furrow—blood springs forth. Histamine explodes and the wave crests. Cells rush in and fluid pours out, waging A microscopic battle against entropy. Macrophages devour flesh of my flesh, Metalloproteinases render the matrix insolvent.

Fog clears and dust settles, chaos gives way To the stillness that follows. Stitches dissolve Just as the artisans are starting their work. The scraps and tatters are collected, molded, and Compressed. Fibroblasts, weavers of fabric, Lay down a quilt and cinch the seams tight.

Remember what Hemingway wrote?

“Everyone is broken, But some are strong In the broken places.” We carry the past with us: the scars in Our skin project the chinks in our souls— Memorials to fragility, patched with precious metal.

NoahCassidyisafourth-yearmedicalstudentatthe UniversityofNorthCarolinaSchoolofMedicineand isplanningtomatchintogeneralsurgery.healing healers

I argue that attending to my depression journey and benefiting from the emotional intelligence of my providers will better help me care for patients in residency. My healing will allow me to notice and respond to the beliefs and emotions that may hinder wellness in the patients I treat. To illustrate, I’ll share with you a story. I told Dr. Jones, my primary care physician, that I wanted to discuss pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), an antiretroviral medication to decrease the risk of HIV infection in uninfected individuals. I had been looking forward to this appointment for days and was determined to advocate for my health. For years I had experienced invalidation and judgment from loved ones and members of my faith community for the types of sex I had. I anticipated this visit would not be any different.

During my time in medical school, I’ve come to appreciate how successful care of patients relies on addressing their emotions as symptoms worthy of attention. In a pediatric clinic, I saw a teenager with obesity for a routine visit. As I inquired about his eating habits and activity levels, he and his dad grew annoyed at my line of questioning. I could see their eyes roll and hear the pitch of their voices change. I paused and listened as they explained to me their belief that people are naturally different sizes. Achieving wellness for this young man required naming his emotional reactions to my initial questions and adjusting accordingly. During this encounter, I recalled Dr. Jones’ ability to adjust accordingly when it came to treating my depression.

Recognizing my emotional state allowed Dr. Jones to treat both my newly elevated blood pressure and worsening depression. As a Black man, I wanted to lower my already increased risk for hy-

pertension, especially now that my dad would soon need a kidney transplant and my having high blood pressure might preclude me from being a living donor. In addition to medication management, Dr. Jones began to explore lifestyle changes I could make. He noticed my shoulders drop and words elongate as I admitted to exercising less and eating more takeout. Unclear what to make of my demeanor shift, Dr. Jones reflected his observations back to me. I took a deep breath, recalling the promise to advocate for myself. I tearfully shared that I had managed to live past my recent “suicide date,” which I had planned to be one day after my last visit with Dr. Jones just two weeks prior.

During my own bouts of contemplating suicide while in medical school, I also participated in scholarly research involving improving Black youth suicide prevention efforts. In addition to common risk factors such as depression, studies show that, in comparison to their White counterparts, Black youth who die by suicide are more likely to have had a recent crisis, family or relationship problem, a history of suicide attempts, or other suicide circumstances like housing instability.1 Meaning, our ability to effectively address the social and environmental factors that influence mental health is integral to improving clinical outcomes among this patient population. My interest piqued in this growing field some refer to as community psychiatry during my rotation at a Healthcare for the Homeless clinic, located on the edge of historically Black East Durham. Ms. Albright who works in this clinic routinely explains to incoming learners that she rarely implements traditional psychotherapy with those who are actively experiencing homelessness because helping them secure housing, food, and finances takes priority. The myriad social challenges that influence and exacerbate mental illness, such as disconnection from robust support networks, must be addressed for

individual patients and populations to achieve mental well-being.

The social realities contributing to my depression led my psychiatrist, Dr. Tiller, to ask the same question at the conclusion of our visits: “You’re going to stay alive until our next appointment, right?” This statement is reflective of a no-suicide contract, which is an agreement to not die by suicide. Research on the use of no-suicide contracts indicates that, alone, such a contract is not effective for suicide prevention. In this circumstance, however, Dr. Tiller deliberately chose to introduce the no-suicide contract, maybe to address my history of relational discord as an important suicide risk factor to consider among Black patients. In those moments where my suicidal thoughts pervaded, I clung to what Dr. Tiller, looking straight into my eyes, asked after each session.

I have heard therapy described as an effective way to combat the lies we tell ourselves. A lie I believed was that as an aspiring physician, and now a current residency applicant, exploring my sexual identity and addressing my suicidal thoughts would conflict with my ability to care for patients. My therapist, Dr. Maverick, constantly reminds me that there is more to me than my ever-evolving sexual orientation. Similarly, I am more than just an aspiring psychiatrist. With the help of my robust care team, I have learned to see all my identities as informative to the care I will provide for patients. While I gratefully appreciate the increased number of initiatives encouraging health professionals to seek help, I have rarely found space to admit to my colleagues in professional settings when I am struggling and actively working to heal. So, as the beginning of residency approaches, I want to continually practice vulnerability, acknowledging that the burden to share is not an individual’s responsibility. Rather, our medical culture that disincentivizes normalizing mental health, namely through cumber-

some licensing renewal processes for those with mental illness (even when they are currently receiving treatment) must be themselves renewed. This piece encompasses my desire to contribute to this renewal in both formal and informal metrics and cultures that influence the medical trainee experience.

Dr. Brené Brown, a researcher on shame, argues that there is strength, not weakness, in vulnerability.2 Brown’s research captures the essence of vulnerability as risking emotional exposure. Fearfully asking Dr. Jones about PrEP, reflecting on and sharing my journey with depression and suicide, and forging strong interpersonal and cultural ties with Dr. Tiller and Dr. Maverick will help me to connect with patients. Importantly, I am not suggesting that connection only occurs when healthcare professionals experience the exact same things as our patients. However, compassion for patients does require a recognition of one’s own struggles.

“Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a relationship between equals. Only when we know our darkness well can we be present with the darkness of others.”

– Pema Chödrön3So, as I begin a new chapter this July 1, I challenge myself, my fellow colleagues, and the institutions that hire us to facilitate being our whole selves, knowing that it can help us better care for our patients.

1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020, October). African American Youth Suicide: Report to Congress.

2 Brown, B. (2015). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead.

3 Chödrön, P. (2007). The places that scare you: A guide to fearlessness in difficult times.

ChrisLeaisanalumnusofDukeUniversitySchoolof Medicineandacurrentfirst-yearpsychiatryresidentat theUniversityofPennsylvania.

good death, bad death

With the sunrise just peeking over the horizon, I walked into the hospital looking down at Haiku pulled up on my phone. An unfamiliar name had been added to my list of patients overnight: Mr. M. After getting to the workroom and settling in, I opened up his chart on the computer monitor. This wasn’t a new overnight admission, but a rollover from the ICU to the step-down unit. I skimmed through the deluge of ICU progress notes, getting lost in the unfamiliar language of critical care. The night float resident arrived with handoff, introducing my new patient as a “trainwreck” of an ICU course. I jotted down the phrases I could catch as she rattled them off: “neuroendocrine cancer”, “hip fracture”, “emphysematous cystitis”, “GI bleed with IR embolization”. After giving a shaky presentation to my attending and the rest of the team, we embarked over to the Central Tower to see him.

He lay in bed and turned his head towards the door as our team walked into his room, greeting him with a cheery “Good morning, Mr. M! How are you doing today?” He turned his head to face forward again, saying “I’m doing alright”, unfazed at meeting this new group of strangers. As we did our assessment, I noted how the skin was sunken at his temples, how his wire-rimmed glasses rested low on his nose, how he pursed his lips together when he had nothing further to say. We made small talk about football before leaving, and he became another set of

boxes to check off on my daily to-do list.

On all my patient checklists, the “Family” box was the one I usually didn’t have to worry as much about. Usually, a loved one would be in the room or available over the phone at some point during rounds and can be filled in. Mr. M was usually alone. He had two daughters, R and C, who worked during the day, so it became part of my routine to call daughter R right before I left for the day around 6 PM. No matter how tired I was, how badly I wanted to go home and eat dinner and pass out on the couch, I dialed her number, knowing that I would want someone updating me if it were my dad in the hospital alone. I’d give a quick update of what we did that day and how he was doing, answered any questions she had—she usually had a few—and promised to keep her in the loop.

Unlike most of the patients I took care of on my internal medicine sub-internship—a steady ebb and flow of tidy admissions and discharges—I took care of Mr. M for three of my four weeks on service. We monitored his blood counts, ordering transfusions when they dropped. We gave him medications to keep his blood pressure high enough to tolerate dialysis. We weaned him off TPN, to NG tube feeds, to oral nutrition. His urine output and food intake decreased. He developed sacral pressure ulcers that wouldn’t heal. He shifted in and out of delirium; on especially bad days, he would just moan “Ah” monotonously on a loop, unable to

let us know what was bothering him. “He’s dying,” my senior resident said to me one day with a sigh. I didn’t understand how he was just getting sicker and sicker despite making and accomplishing a new plan for him each day. It felt like we were just doing things to him, not for him.

Across these three weeks, we danced around the subject of palliative care and hospice. I gleaned from previous ICU and palliative care notes that Mr. M and his family were resistant to engaging in any sort of “end-of-life” discussions. He was diagnosed with this neuroendocrine cancer nearly a decade ago and had since exhausted all treatment options his oncologist could offer. He was told over and over again that he was going to die and continued to live, so why should they trust anyone? We did our best to ask him what he wanted, what his goals were. When we first met him, it was, “I want to get up out of this bed”. Then, when he got to the point where he physically couldn’t work with PT anymore, it was, “I just want to live,” as he looked up at us with pleading eyes. “Mr. M, can you tell us what’s important to you?” I asked as a follow-up. “Don’t ask me that,” he responded curtly, turning his head towards the window. Our team decided to call a family meeting to discuss how Mr. M was not meeting his nutritional requirements and didn’t want an NG tube to be put back in. I finally met daughter R in person. At this point, we had talked on the phone nearly every evening for the past 2 weeks. When I got

to Mr. M’s room we greeted each other joyfully, finally able to put a face behind the voice. She was wearing an oversized t-shirt and her hair was tied up. She had on a pair of the purple hospital gloves and was vigorously wiping down the surfaces in his room. She had a commanding presence and fierce energy about her that she exuded both over the phone and in person. Before the family meeting started, I passed her a tissue box when I saw her dabbing at her eyes with her t-shirt. “Oh no, I don’t need that,” she scoffed, thinking that I assumed she was crying. We pulled up chairs and sat down around Mr. M’s bed with daughter C joining over a video Doximity call. My senior resident started off with a summary of Mr. M’s hospital course and our concerns about his nutrition. “Pop, why aren’t you eating?” his daughters kept asking him. “You just need to eat,” daughter C implored, her voice grainy on the call, “We need you here pop”. He had nothing to say back besides a quick grunt, lips tightly pursed. As the reality of Mr. M’s decline settled into the daughters’ awareness over the course of the conversation, daughter R’s toughness melted away. She turned away, her shoulders shaking with sobs. She still would not accept the tissue box. I bowed my head and laid my hand on her shoulder, my own tears silently spilling over onto my mask. The love emanating from the adult daughters towards their father—and the anticipatory grief of losing

him—was a palpable force in the room.

Despite our efforts to transition Mr. M to a nursing facility, he continued to get worse. His pressures dropped so low we had to call an RRT, and as the critical care team filled his room, I called daughter R from the hallway right outside, asking her, “Do you want us to transfer him to the ICU?” “Yes,” she said after pausing for a minute to think, “the last thing he told us is that he wants to live so we need to do everything for him to give him a chance.”

After the end of my four sub-I weeks, the gen med teams switched. I started on the palliative care service after that and was able to continue following Mr. M on this new team. We touched base with his ICU providers, letting them know we were on board if they needed anything from us. We walked by his room on rounds but couldn’t talk with him as he was no longer fully conscious. After a few days, the palliative care team signed off. I tried stopping by his room, but his daughters had stepped out for lunch. “You just missed them,” the nurses let me know. Even though the palliative care team wasn’t following him, I couldn’t help but keep checking his chart to see how he was doing. His organs continued to fail, and he was intubated. Some of his

distant family members were able to see him before they decided to transition to comfort care. He died shortly after.

What does it mean to have a good death? Is it knowing that your doctors helped you fight to the end and gave you every chance? Is it being in your home surrounded by your loved ones? Is a doctor’s perception of a good death the same as the experience of the dying patient? I thought back to the times we tried to broach goals of care discussions with Mr. M, and how unfair it was of us to force him to confront his own mortality over and over again when he was in pain or confused. Debriefing with my palliative care attending, I learned that we can never make anyone ready to die. We can never make anyone ready to lose someone they love. After Mr. M died, I had a dream where I could see him standing in the distance, his back casually slouched. He was wearing a red polo shirt and jeans, his wire-rimmed glasses resting low on his nose. I could feel the life and vitality visibly radiating around him–the version of himself that I imagined he grieved the loss of, that I wondered if he could return to in death.

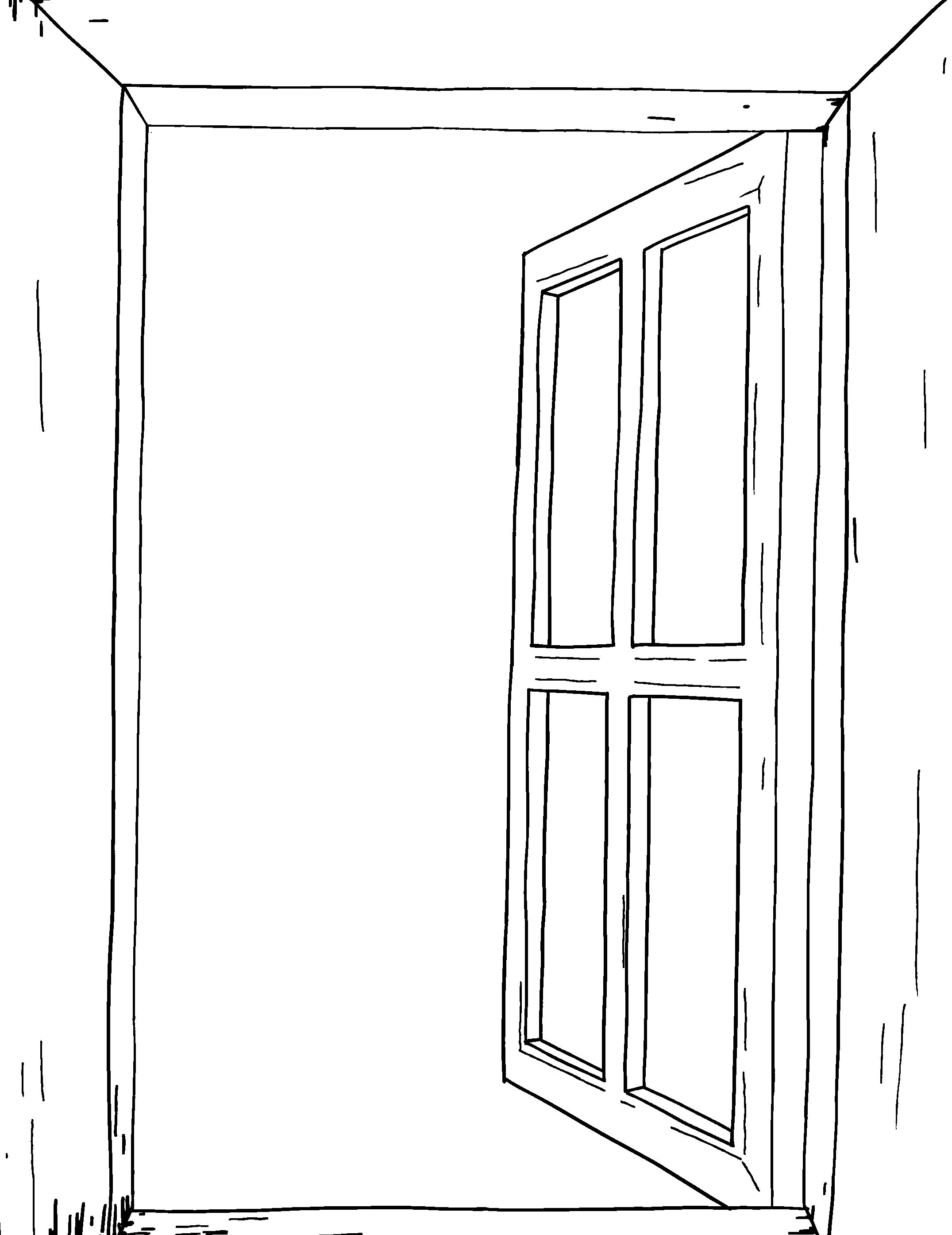

KellyGooisafirst-yearPrimaryCareInternalMedicine residentatYaleUniversity.through the window

It should be close. Happiness, that is. Not yet achieved, but promised on the other side of this education. Four years of carrying around a perpetual back ache, heavy bags under my eyes, and guilt from minimal phone calls home were endured for a purpose. Yet I feel no different, even as the diploma, title, and profession have finally come into vision. The breath of air I was promised is nowhere to be found. Anger floods my body, soon replaced by disappointment and melancholy. Perhaps I am not close enough. If I give myself a year of residency that might do the trick. The promise of success can motivate me to keep going. I tell myself this, but for the first time, I do not believe it.

A noise outside shakes me from my distress, and I turn toward my window. It allows soft, golden beams to catch my face. It reminds me of late summertime. My favorite season, filled with walks in the early evening glow. As I pause and think, I remember the scent of fresh waffle cones downtown, and the exact bench I sit at to change songs before my trek home. Small, gentle things. It seems I have forgotten to appreciate them.

I get up and venture a bit closer. Thinly lined with dust, the cream-colored windowpane has scattered chips of paint and dented wood. Aging can be so cruel. It makes me remember stretches of time where I too felt broken and beaten. I can feel my gut twist, as I recall the memories of my heavy sobs, created from a cadence

of my own gasps for air. Heartbreak is a tricky thing—equal parts soul-crushing and redefining. Striving to love and be loved, especially in this field of work, is no easy task. Despite every up and down, I feel peace in being in my own presence. At last, alone but not lonely. I rarely admit the strength it took to reach this point.

My gaze lingers outside, where my window overlooks the street. I see an elderly resident in my building. He often rides the elevator around 7:40 am and 5:20 pm too. I smile to myself, thinking of our small conversations. It did not matter if we talked of the weather or a new restaurant opening nearby, he somehow made me feel cared for in a short passing of time. Even his small, but intentional smile would brighten my mood. There is something contagious about kind strangers with good hearts. I do not stop to admire that simple joy enough.

In the pursuit of medicine, I fear I often overlook what it means to be human.

Has it always been so close? Perhaps not happiness, but rather contentment. It has been sitting here patiently, surrounding me, yet remaining unclaimed. It is like the window —both nothing and absolutely everything. It is neither a place nor a destination, but an element of each day. At last, I take a deep breath.

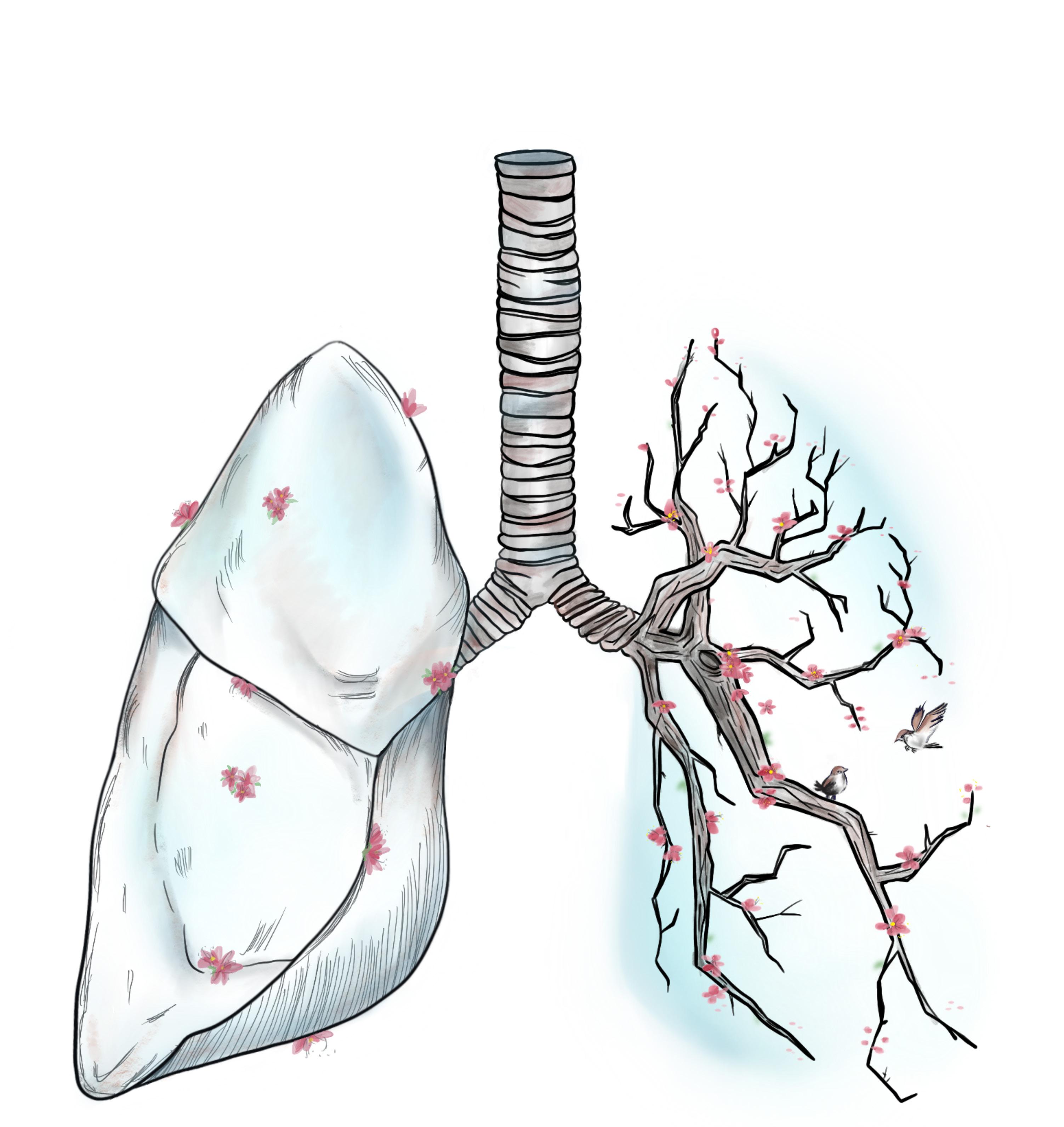

front cover artwork: Breath of Hope

LauraTanisasecond-yearDoctorofPhysicalTherapystudentat DukeUniversitySchoolofMedicine.

The flowers bloom and the birds sing, A song of hope arises amidst the darkness. I am restored, There is new breath in my lungs. sites.duke.edu/voices