voices

voices

VOICES is the student-run literary magazine of the Duke University School of Medicine. We publish various forms of creative expression from the medical community and welcome submissions from patients, students, healthcare providers, employees, families, and friends. Our goal is to publish a range of unique voices from inside and adjacent to healthcare. As you read this issue, we hope that you will be inspired to submit your own writing or artwork. Send all submissions to voices@duke.edu.

Endings are often bittersweet. The ending to a good novel leaves a paradoxical sense of both satisfaction and longing; the ending to a relationship is fraught with loss entangled in cherished memories. As we end our first decade as a literary journal, our reflections of the last ten years are bittersweet, complemented with hope for the ways our journal will continue to evolve.

In medicine, endings can often feel more bitter than sweet, and yet the world of healthcare requires us to put aside our grief and turn a new page every day. As we present this issue featuring numerous voices across healthcare, we invite you to consider their postures toward aging, death, and end of life. Whatever emotions you encounter as you read, give yourself permission to embrace them. Take hope in the knowledge that you are not alone.

As always, we thank the Trent Center for Bioethics, Humanities, and the History of Medicine for their unwavering support of our literary journal through the years. We thank you, the reader, as well, for your careful attention to the topics we lay before you. We would love to print your prose, poetry, or artwork in a future issue of VOICES and welcome your submissions to voices@duke.edu. For more information, please visit our website at sites.duke.edu/voices.

Your co-Editors-in-Chief, Linda Li & Lucy

Zheng

JermeyRisenburghasbeenpracticingasanuclear medicinetechnologistfor28yearsandcurrently seespatientsatDukeUniversityHospital.

The Scan—once completed is conclusive

Bearing a ceaseless certitude

The Old man's wife is dying

Her body effete with cancer

In that moment the eyes convey the aggregate

The Abhorrent antipathy of the occasion Grains of sand slipping through an hourglass

Discerning that there can never be a return to normalcy

Their world so carefully co-created is ending

JonathanJoasiliscurrentlyasecond-yearmedicalstudentatthe Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

My first patient was my anatomy lab cadaver. I began each lab session by tying up my lab coat, feallessly pulling on blue gloves, unaware of the tears to come and the unexpected joy that our cadaver would provide. That body and spirit reinforced the importance of gentle hands and compassionate care.

Florence Nash was an editor and research analystatDukeUniversityMedicalCenterand, for16years,sheledthepoetryworkshopat Duke’sOsherLifelongLearningInstitute.She wasasubjectinaUNCnarrativemedicine studyonfallingintheelderly.

SubmittedunderthepseudonymCosmoNatali.

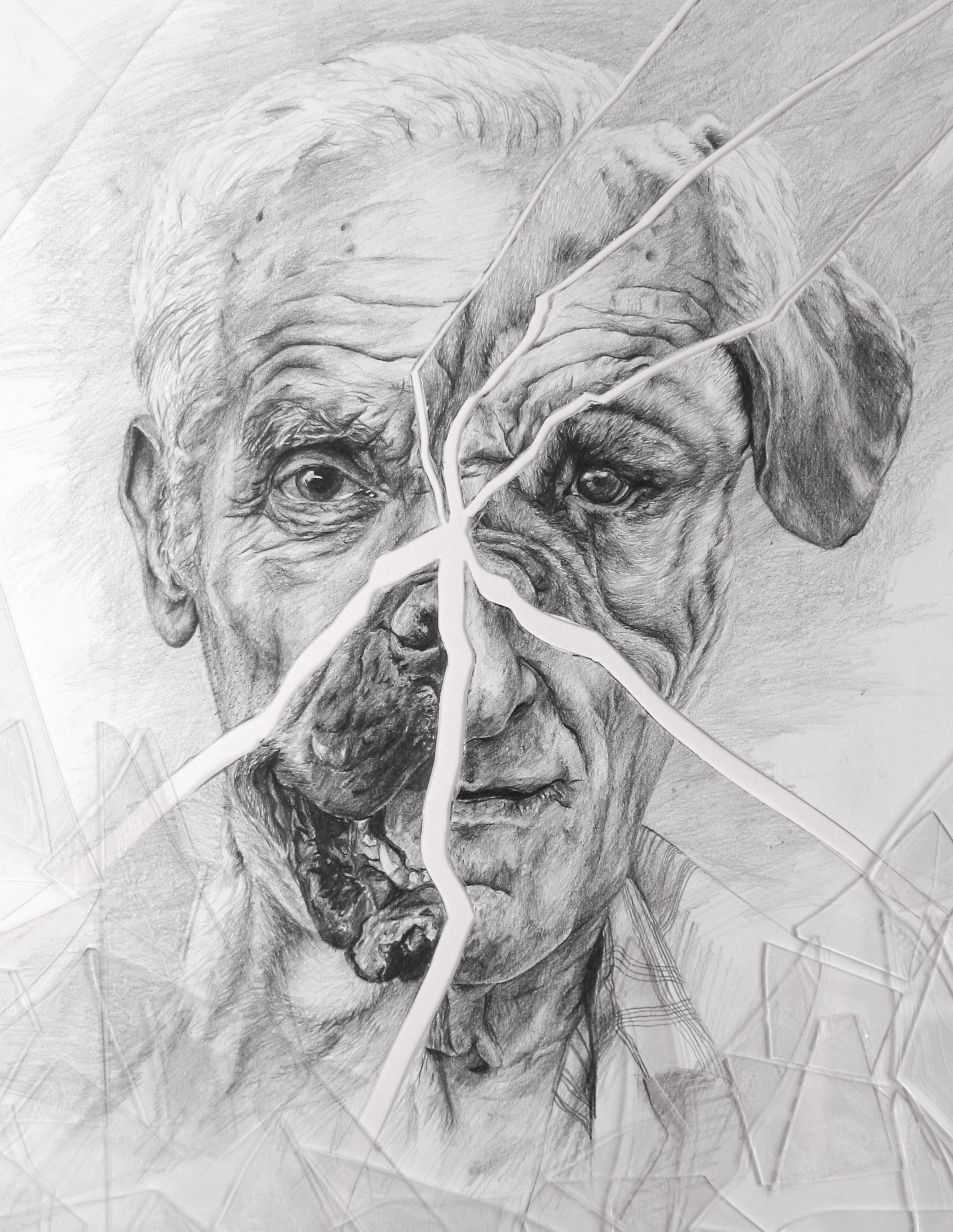

Overwhelmed by the clarifying light of medical knowledge

I have become blind to a component of humanity

There has always been sickness around me but now I have begun to train myself to hunt for disease

What once was cloudy has become clear and I fear that this training pushes me to become something I never asked for

To preserve life

I have become an expert in death

My new eyes scare me

No longer can I catch the gaze of another without scanning for a sign of sickness subconsciously suspecting the worst

My new mind terrifies me

I cannot help but note the bruise on my friend's cheek I find myself guessing for its source

A sports injury vitamin deficiency malignancy

My new heart wounds me

My first patients I gave them everything of what little I could offer But now I understand their pain is a natural part of this progress

My new hands sadden me

Having picked a cadaver from head to toe they have grown callous to human touch

An integral part of human communication now feels trivial

An original innocence lost

But my fear tells me there must be hope that this process is not needlessly cruel

We always knew this might happen in medicine because clinical means cold

And having some distance is healthy for who would want a surgeon put off by the scalpel or a consultant unwilling to order tests for fear of what they might uncover

There is awe in the complexity of the human body a miracle when we are successful in healing

And it is now our job to rediscover that sense of wonder that led us here

And while it is painful when we first step outside into that morning winter air it makes the return to the warmth of home all the more pleasant

So in this time of training we will be remolded to see the human body anew and we will miss the old naivete of youth

We will one day find it to be more beautiful

NeilCornwellisa4thyearmedicalstudent at UNC School of Medicine. Some are given a choice each day: whether they are going to serve patients or be one. For others, it’s not their decision. The culture of medicine needs to recognize that the white coat may simply be worn over the patient gown. Our humility is understanding that these two identities are not mutually exclusive.

Ruben lay back into the couch and weakly tugged the blankets to fill the space where his legs used to be. Amelia, his social worker, knelt beside him and handed him a bag in case he needed to throw up again. “How are you doing?” she asked with a serious tone, indicating that she wanted to know the whole truth. “I’m tired, and I’m in pain,” he whispered. “I don’t want to go to dialysis anymore.” Amelia turned to Ruben’s wife. “He’s ready, Lidia.”

We go way back, Death and I, but I was always more focused on the aftermath. Death had entered my life abruptly in the past, either through tragic accident or willful denial. I knew well the loss of a person from the present and the future and the grief that stretches out ahead in all directions, and I was terrified by it. I was much less familiar with Death’s approach and the expanse of emotions and actions that lay before it.

The day that Ruben decided he was ready to die was the first time I met him. He did not have the energy to sit up or turn his head, but his eyes darted back and forth from my face to the next. As the doctors and social workers told Lidia what to expect in the coming days, Ruben drank in everything around him with intensity. Occasionally he would assert quiet interjections. “I want the hospital bed in here, not in the bedroom…I don’t want to be lonely.” Lidia mostly sat in silence. It took Ruben time to come to this decision, but this was the first that she had heard about it. And now the doctors were tell-

ing her that he only had fifteen days left.

When we came back to the house the next day, Lidia greeted us at the door, shooing away a flock of chickens and dogs. She ushered us back into the living room, where Ruben sat upright on the couch, quietly eating applesauce. It seemed that his decision had given him a new wave of energy overnight. “It’s called the ‘hospice honeymoon,'” one of the doctors later told me. Ruben and I sat together peacefully while people flowed into the room around us. When a doctor asked about a family portrait hanging on the wall, Ruben named his children proudly. His son joined us, and Ruben clasped his hand, smiling softly. His daughter, whom he had not seen in years, was also at the house, making amends. Ruben had been in and out of the hospital for months, and now he was home, resting with his family. He had seen his Death approach and welcomed it, and in doing so, had allowed those he cared for to share it with him.

Death has been looming in my life again recently, and I have not been able to shake the fear that the worst will happen, a consequence of losing my people when I was young. But now I try to see Death through Ruben’s eyes. I try to remember the grace with which he accepted it, and to see the possibility of reconciliation, growth, celebration, and grief that lies between Death and all of us, even if it is only fifteen days away. AnnaKenanisafourth-yearmedicalstudentatUniversity of

For he doesn't understand how their faces, how their stories, haunt me still even while sitting next to him.

For he doesn't understand how much a heart breaks.

"There is nothing more to do." "I am so sorry to tell you that..." "Time of death..."

For he doesn't understand how I give it all to them. Strangers he will never meet. And I have nothing left for him.

For he doesn't understand how the gravity pulls us. Always talking about our latest case or most grueling encounter all while at dinner with friends.

For he doesn't understand how freeing the elation of the perfect procedure, securing the diagnosis, earning trust of the family truly is.

For he doesn't understand yet still there is warm dinner, a made bed, my favorite song.

For he doesn't understand but tries.

HannaVargaisa5thyearPhDCandidateinEnvironmentalEngineeringatDukeUniversity,withapassionfor renewableenergy,sustainabilityandproblemsolving.

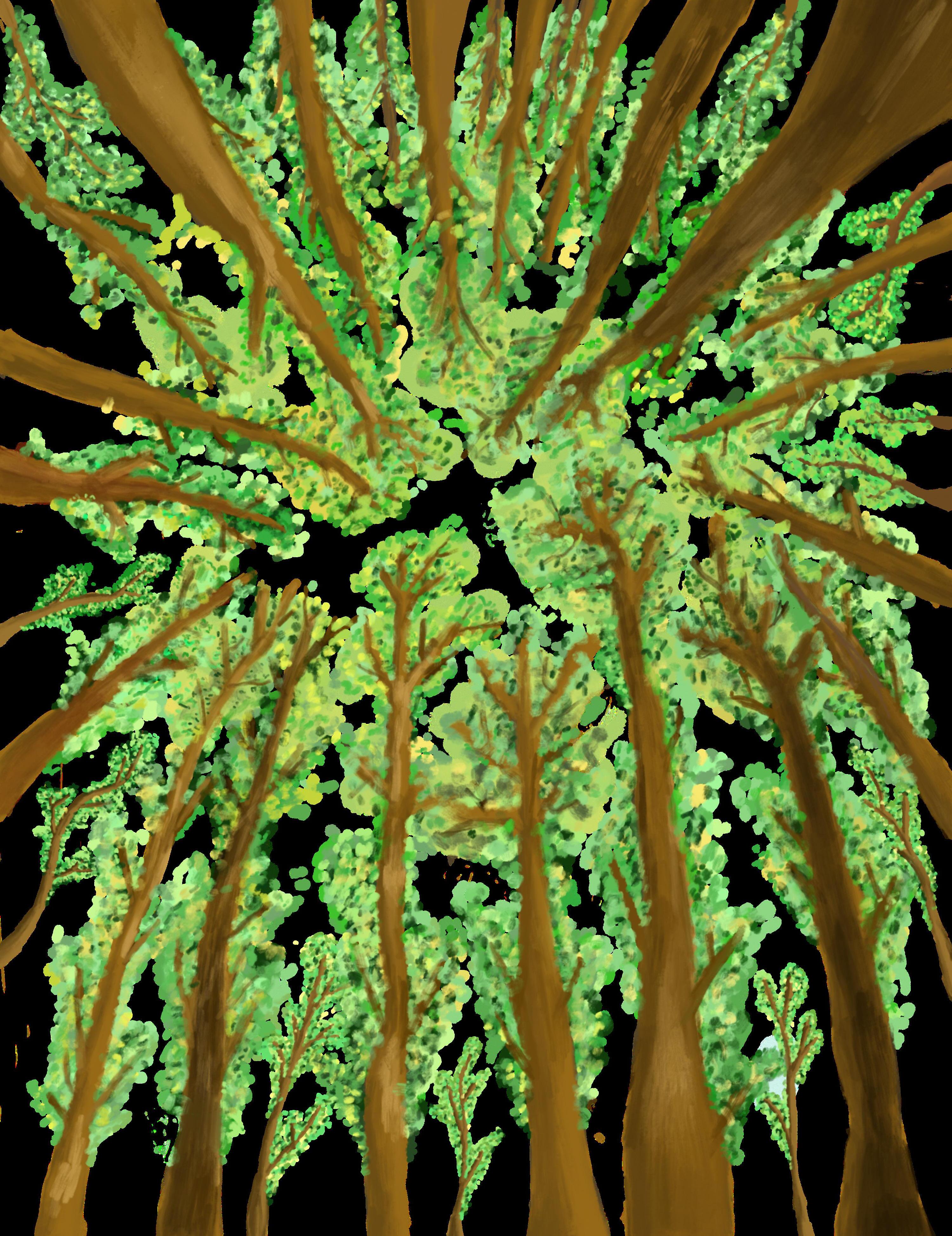

O, pine, I want your opinion about changes you see, as you stand evergreen, unlike the world around you. Silent you tower, as snow and the world fall, flower, wilt around you. And your needles yellow to beige to brown, wither, crisp and drop. And you observe, rooted and helpless.

Seems like a mile down

The corridor to the Duke pre-op clinic

Barred panes of sunlight mark

The slow passage, as if through a prison

Seems like a march to your execution

And perhaps it is

There will be another sentence of surgery;

Recapitulation of the transplant

Pierces like a lethal surge of voltage

You can barely move your

Feet, your legs

Down the sunlit mile

But you feel the sun

Through the panes of light

You see life outside the corridor window

You hope and pray and trust

Above all

As you trudge the sunlit mile

That for once

History does not have to repeat itself

And this time

This time

The sun will shine upon you.

KHHolladaygrewupinTennesseeandreceivedherBAinEnglishfromtheUniversity ofWisconsin.Afiercedevoteeofpoetry,old moviesandtheCarolinacoast,shelivedin Durham,NC,formanyyearsbeforeherdeath in 2016.

SeandeLeonisafourthyearmedicalstudent atCreightonUniversitySchoolofMedicine, whoplanstopursuetraditionalistinternal medicine(equalmixtureofinpatientand outpatientmedicine).