Voices is the student-run literary magazine of the Duke University School of Medicine. We publish varied forms of creative expression from the medical community, and welcome submissions from patients, students, healthcare providers, employees, families, and friends. Our goal is to publish a range of unique voices in and adjacent to the healthcare system. We hope that as you read through the pieces in this issue, you will be inspired to submit something as well. Send all submissions to voices@duke.edu.

Like taut violin strings, the tension in our divided society awaits resolution, but whether we end in sweet harmony or in contentious cacophony depends on how we play our pieces. In this issue, we present the trailblazers of our community who are discontented with the status quo. Three years into the pandemic, we have seen its world-shattering effects: the unveiling of long-existing inequalities in our communities, political divisions over the ethics of vaccination, the realization of our limited infrastructure, and skyrocketing rates of burnout in providers. As society embraces a new “normal,” however, we cannot forget the lessons learned. In fact, our contributors place even brighter spotlights on the faults of our healthcare system and on the flawed breed of providers manufactured by our training, with the hope that change is on the horizon.

As you examine these selected works, we encourage you to speculate on not only what behavior characterizes the best providers, but also what culture might empower them to thrive. How can we cultivate our inner psychiatrists and cope with loss in the OR? When will the era of Big Medicine and Big Pharma end? And how can we change the conversation in healthcare about culture? The answers are far from simple, yet in them lie the blueprints to a new structure of providing healthcare, one that focuses less on simply providing and more on caring.

We hope you enjoy this issue. We thank the Trent Center for Bioethics, Humanities & the History of Medicine for their immense support and for partnering with us to host the ongoing contest “RENEWAL.” Please submit prose, poetry or art to voices@duke.edu and visit sites.duke.edu/voices/renewal for more information.

Your co-Editors-in-Chief, Lindsey Chew, Devon DiPalma, Emily Hatheway Marshall, and Linda Li

We should change the conversation in healthcare about 'culture'

Meredith Cox MS1 Seth Flynn MS4

S. Tammy Hsu, MD PGY4

Judah Kreinbrook MS1

Hannah Maclellan MS1

Kira Panzer MS4

David Ryu MS3

Siraj Sodhi MS1

Dominic Tanzillo MS1

Daphne Zhu MS1

Lucy Zheng MS2

Mariam Ardehali MS3

Karen Jooste MD, MPH

Sneha Mantri MD, MS

Brian Quaranta MD

Jeffrey Baker MD, PhD

Marjorie Miller MA

Nikki Vangsnes

I don’t really know where to start. I guess I’ll start with the color red. It seems as good as anywhere; after all, it was Valentine’s Day.

A voice distorted by static blared from the walkie-talkie resting on the chair next to my head, the flashing red light providing the only illumination in the windowless call room. Groaning, I slung my legs off the side of the lumpy futon and pushed myself upright, untangling myself from sheets and blankets pilfered from same-day surgery. Making mental notes of the details of the level one the granulated voice listed, I shoved feet into waiting shoes and tucked my hair into a scrub cap. I amassed my needed supplies, shears, radio, work phone, cellphone, pager, stethoscope, penlight, and began to make my way to the emergency department. I checked my watch; the red hour hand pointed squarely at three. Hour twenty of my shift. Red. The sheet was red. Alright, maybe more of a burgundy. And where the blood stained the sheet, it was an even darker hue. As I began my evaluation of our patient, a young man, some small disconnected corner of my mind wondered where the sheet had come from. I hadn’t previously noticed any of the local EMS

companies having colorful sheets. I could picture it though.

A sheet snagged from the home by police officers, first on the scene. A uniformed figure clambering up icy concrete steps at 2:40 in the morning. The breath puffing out of him in little clouds made visible by the frigid northern air. A frantic shout at family members requesting something to carry him with. A stunned pause followed by an ineffectual flurry as loved ones fumbled around. “Just a sheet or blanket or something!”

Or had this red sheet clothed a mattress of its own so soon before its fate changed? Had the bed, a place of rest, borne witness to the grisly event?

The shoes were red too. A true, bright red. I didn’t notice until later, as I shoved the personal effects into bags for evidence. Cut clothing, jewelry, a redstained-darker-by-blood sheet, and red sneakers, whose color camouflaged the smears of blood marring their otherwise pristine exterior.

Red. I guess I had never thought about just how much a head can bleed. Saturated gauze hid the extent of the entry and exit wounds delineating the bullet’s path. Neck down, our survey revealed nothing, simply youth in its prime. My attending and I made to look under the bandage

slapped on by paramedics, the rhythmic plink, plink, plink of blood dripping onto the metal stretcher from the saturated chucks pad seemed now to echo throughout the bay. I lifted the soggy mass and immediately jerked back as blood sprayed the front of my gown. I glanced up at Dr. Khan, who spared me a grim look before pressing on. Red. The monitor chimed constantly, a red bar flashing in the corner as if we were unaware of the dire situation. We hovered restlessly in the radiology room as the patient went through the scanner. A flurry of movement began at the cessation of the scan as we surged back into the room. I positioned my hands on the head, neck, and shoulders of the patient to stabilize for transfer. Red filled the bottom of the open tube of the scanner, spilling down and pooling on the floor on either side. Red soaked through gauze and chucks and sheets onto my gowned forearms. I don’t know how much time passed. It was a haze. Red coolers of blood arrived. Red arrows marked deranged lab findings; acidosis and coagulopathies we strove to correct. A woman with red, bloodshot eyes rolled in on a wheelchair, the mother. Her speech was slurred, and she slumped unsteadily in the chair, in the throes of some unknown substance. Her eyes were glazed, sliding in and out of focus while the doctor tried to explain her son’s condition. I couldn’t decide if I was grateful she was in the present state. After all, who would want to remember their child, their baby, like that? Red. We had made it to the OR. In the five minutes since the dressing had been removed to prep the field, a red pool had formed on the floor. I kicked a towel under. Then another. While passing over the freshly removed bone flap, I glanced down to see that the circulator had thrown a blanket down in an attempt to mop up the ever-expanding blood at our feet; my suctioning and the fluid collec-

tion pouches seemed to have no effect. Above the anesthesia monitors, suction, and various machines, a steady splat, splat, splat echoed; the blood dripping down into pools formed by the folds of the now-saturated blanket.

As we worked, red coolers of product marched through the door like ants. Splat, splat, splat. A red cart rolled in.

Splat, splat, splat. We worked to the seemingly inexorable rhythm of the blood hitting the blanket.

Splat.. Splat… Splat…. I thought, for just a moment, we made progress toward hemostasis. There seemed to be less blood on the field. I took a deep breath, consciously releasing some of the tension in my shoulders present since the radio crackled to life hours before. It was premature. A low voice from the other side of the drape, filled with practiced calm, directed a question to another set of obscured helping hands. “Do we have a pulse?”

Splat, splat, splat. Blood on my gloves. Splat, splat, splat. Blood on my shoes. Splat, splat, splat. Blood on the pole and on the field and on the floor and as epinephrine was given, blood hit my gown. We hadn’t made headway.

At last, the neurosurgery PA arrived. It was hour 27 of my shift. I stepped away from the field. Peeling off gloves sticky and red with blood, I scrubbed out, the sound of dripping blood trailing me long after I left the hallways of the OR.

Red. I drove home in silence, road noise and the occasional sound of my indicator my only companion. The house was empty on my arrival, save a plump orange tabby. I found a donut left for me on the counter. Red sprinkles coated the treat. After all, it was Valentine’s Day.

I scramble back online for the password. I guess you can never be too safe in the era of zoom-bombers. Passcode error! I curse to myself, eyes shifting to the corner of the screen. 5:01pm, an outsider and I’m already late. I fumble through browser tabs—any desktop neat freak’s nightmare—and manage to find the right page. Join with video. I shift in my chair, back to a blank wall now, tilting the camera for better lighting. 5:03pm. Here goes nothing.

They already started. “From the daily reflection…” I want to catch all of it and see more clearly. But what if they see through me and already know. What if they already know I’m not one of them? I catch myself in what feels like judgment, clicking through the speaker grid, assembling stories from maple kitchen cabinets and sprawling backyard greenery. Observing makes me feel dirty for a moment, like a tourist in the zoo, from the outside looking in. I brush the thought off; I remind myself to just listen.

“Admit to God first, then to ourselves, then to another human being…” It gets meta. “My Higher Power had already placed that thought in my mind. He must have—if I’m trying to ignore it, I surely didn’t put it there.” I sit on the thought. It sounds like some kind of spiritual predetermination or an attempt to erase the ocean of the cognitive dissonance spanning between what the body craves and what the mind rejects.

The daily reflection ends and introductions begin with the host. “Hi, I’m E—.” Everyone waves on screen. I crack a half

smile in acknowledgment. Should I be waving too? “I see newcomers. Let us know if you’re new or just new to us. At the end, some of us will stay on to chat and share more.” I try to decide on the least awkward way to avoid more without seeming rude. The participants list keeps growing though and the speaker grid flicks from face to face, no more than a second spent as each person restates their name with a smile and wave. I copycat them, hoping to blend in. I wonder if anyone is clicking through the speaker grid and imagining the story behind my pale walls and picture frames.

“Who would like to chair the next meeting? We also need volunteer speakers for the next month.” For a moment, I feel like I’ve gotten lost at the PTO meeting and “Karen” is looking for participants.

We transition to another reading in the ritual. “Alcoholism is a disease. All we need to understand are the 3 C’s. We didn’t cause it... We can’t control it… We can’t cure it…” In this space that does not belong to me, I cannot help but wonder about this shifting of responsibility. I think back to what Mr. G had told me. I’m not sure why I did that. I try to keep busy. Cycling keeps my mind off of it. More than 50 miles some days. He had brought himself to our doorstep on Fulton St. and checked himself in for the seventh time that year. It had been more than a couple years. You could say he and the VA were in an on-and-off relationship.

“Now for tradition 6.” Another woman begins reading. “…lest problems of mon-

ey, property and prestige divert us from our primary spiritual aim…” This whole process surprises me. The ritual behind everything. More mentions of God than I could count. This God seems hazy. What does God represent here? Sometimes it’s just a higher power. I happen to believe in God, as much or more than the others here. I’m not sure if they’re the same. I bob my head in solidarity anyways.

The woman switches, from reading to sharing. “Focus, focus, focus. Our main goal here: helping family and friends of alcoholics.” More than a few times, I have been told they are people with disease. Patients with diabetes. Patients with alcoholism. Not diabetics. Not alcoholics. But this woman, I hear her reclaim the word.

She continues, “What would keep our fellowship intact if we went after every worthwhile cause.” She goes on about how she now minds her own business. Rather than getting involved in her husband’s medical affairs, she minds her own business. Unless asked directly. “We show up and bring what we learn to others.” It’s like the gospel. They mind their own business and do not bring outside affairs into the space. On the surface, it makes sense. But then, I’m not sure. I think of the ones who were doing exactly that, minding their own business when others barged into their lives uninvited. Now they’re not around anymore. Not everyone can afford to hide behind this gospel.

Someone else chimes in to share. “Sometimes we do things for the wrong reasons.” Don’t we all sometimes? Nods all across the screen. We humans can be

selfish creatures. “To maintain the purity of this space, we can discuss our feelings and how this space impacts them, without bringing in outside affairs.” I’m still skeptical. It sounds like compartmentalizing people into neat little boxes. Trying to open one, without the rest spilling over.

“It means to focus on me and take the focus off of the alcoholics in my life.” They’re reclaiming their narrative. To my inner psychiatrist, this seems like a good first step. At some point, enough is enough and these steps will help them move on to a better place.

“Let go of the anger, keep it simple, and healing will follow.” It sounds so easy when put like that. I can almost hear Amen echoing from “the pews.”

“I stopped giving others advice. I don’t want my foot in the door, and if something goes wrong, I’ll wanna stick around to fix it. And then I’ll just be in deeper. Distracted from my own path, and my immediate people will suffer from my divided attention. So I stopped.” When he put it like that, it seemed clearer. He didn’t have the luxury of multi-tasking. Keeping shit together was already his full-time job.

“It’s a fragmenting disease that divides and conquers. It fragments emotions, relationships, life.” More vigorous nodding and empathetic gestures.

“I used to be married to an alcoholic. Now I’m not.” I think of Ms. Z. That was the

life she rejected; she left that life in lieu of the happily ever after that she knew she and her children deserved.

“We can’t do this on our own, but a higher power intervenes and brings miracles. Even if our higher powers are different, the focus is on sharing what maximizes benefit to the group.” Heads bob in agreement again across the screen. Hard to argue with that. Whatever works. In recovery and healing, to each their own.

The last ritual proceeds, a reminder that “the opinions expressed here are strictly those of the person who offered them. Take what you like and leave the rest.” I remind myself that I just came to listen, to hear them, to see them. I might never know, but at least now I would know.

“Though you may not like all of us, you will love us in a very special way, the same way we already love you.” Shared experiences bond people together. The sentiment is poignant. The world could do with more love and listening. Anyone could agree with that.

Voices synchronize in recitation.

“God, please grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things I

can, and the wisdom to know the difference. Let it begin with me.”

Anyone listening would feel accepted by the group—even if acceptance was being liberally projected onto every body like a thick fleece blanket on a sweltering summer day. Physically gathered or not, the feeling was palpable. In any other space, it would have fallen flat. Think the overly chirpy sophomore English teacher who just wants the class to like her, to be inspired by literary musings. But not here.

Joining as an outsider, but somehow leaving in the know. How many of us had that epiphany? Every year, we come in, we listen, we reflect, and we feel enlightened. Like we really get it now, like we realy understand the inner workings behind each face. Then we leave.

Some of us give those moments a second thought, genuinely drawn by the raw unfiltered humanity. We take a posture of humility and allow ourselves to learn from whoever is willing to teach, dropping the armor of

“academic medical professional” just long enough to sit side-by-side (or screen-toscreen, as it were). As peers tackling the human experience, power dynamics lifted to whatever extent possible, we share in an equal exchange leaving both humans more connected, hearts happier.

Some of us never turn back. Sometimes, preoccupied by our own unrelenting current of life. Other times, believing we already learned those lessons well enough. A decade of training later, we are learned experts on the patient and have seen nearly every kind. Like human encyclopedias cataloging their kind. As experts, we are enlightened.

Few of us commit a lifetime to that inner psychiatrist. In the ivory tower, countless lecturers open with “the deficit of mental health providers.” Recognizing the many “patients in underserved communities,” they call us to service.

Maybe it is better this way—with an already sanctified space to focus, focus, focus on the human beings in the room. At least that’s what we tell ourselves.

After all, what do we really know?

TheartistisaprospectiveNeurosciencemajoratDukeKushan Universitywhoisinterestedinmedicalresearchandpsychiatry.

The brain is divided into two distinct hemispheres that get to know each other by sending messages across a channel. The Corpus Callosum lets these two halves, represented here as people, get to know each other. (medium: oil pastel)

The word culture is heard quite often in healthcare — and more specifically in undergraduate and graduate medical education (UME/GME). Profound issues ranging from burnout, resilience, implicit bias, trust, and psychological safety reflect organizational culture in healthcare.

Organizational culture is, by definition, an integral part of everyday life across healthcare settings (clinics, operating rooms, classrooms, anatomy and histology labs, admin offices, etc.). Just like all organizations, every healthcare organiza-

tion and medical school has a culture. It is the result of the climate set and reinforced primarily by leaders. Arguably, there is nothing more important in healthcare than culture as it informs and influences everything that happens or doesn’t happen, from patient safety and satisfaction, to employee engagement and motivation, to student learning.

In the academic literature, culture has been defined as “the learned beliefs, values, rules, norms, symbols and traditions that are common to a group of people."1

Leadership developer Robert Stringerdefines culture as “the unspoken assumptions (values, beliefs, myths, traditions, and norms) that underlie an organization."2 Psychologist Edgar Schein characterizes culture as “…a pattern of behavior of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration."3

To summarize, culture is often referred to with terms like norms, beliefs, values, processes, or traditions. Here we argue that culture has become a buzzword that is meaningless, vague, philosophical, and/or academic. With this intellectualization of “culture,” a third-person element is assumed — as in “I am not responsible for the 'Culture' in this clinic, they are” or worse, the “Culture” is othered and not associated with any group or individual.

In reality and without parsing words, culture in healthcare is ALL about the behaviors of the human beings in an organization — or more specifically, how the people in an organization treat each other. This starts with the individual, and how

cords (EMRs) are a system that greatly influences doctors and patients. Clinic schedules and OR times are an integral part of healthcare organizations. These systems and processes did not invent themselves. Humans created them, and therefore, created these culture components. How a surgeon delivers feedback to a student or resident is a reflection of that MD’s values and beliefs. If they choose to embarrass and ridicule the learner in front of others, that behavior may be accepted or ignored and perhaps modeled by others. This surgeon’s behavior is a reflection of the culture that he or she is creating and reinforcing in the OR.

How the humans in an organization treat each other, and perform, is in part the result or outcome of how the leaders in the organization behave. Behavior drives behavior, which is really about leading by example. And the sum of all the behaviors equals culture.

Culture, of course, is a culmination of individual interactions.

Perhaps this definition can better address the issues of culture — "the worst behavior or process that will be tolerated in an organization." Which, in turn, implies that culture is the worst behavior tolerated by individuals.

one human being chooses to interact with their fellow human beings.

Words such as processes, systems, artifacts, values, beliefs, and traditions are often used to describe or explain culture. But where do these processes, systems, artifacts, and traditions come from? Human beings create them (they don’t create themselves — in direct contrast to the othered ‘Culture’ often described). How the humans in healthcare talk, listen, think, create, and behave is the culture and climate in that healthcare organization.

For example, electronic medical re-

If healthcare, or more specifically UME/ GME, really wants to teach and improve culture, then they should consider emphasizing that the quality of the interactions between human beings in an organization generates and reinforces culture.

Behaviordrives behavior, which is really about leading by example. EmilyHathewayMarshall,aFellowHuman,isafourth yearmedicalstudentatDukeUniversitySchoolof Medicinepursuingacareerinpathologyandmedical education. 1 Peter Northouse, Leadership: Theory and Practice, pg 336 2 Robert Stringer, Leadership and Organizational Climate, pg 14 3 Edgar Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, pg 18

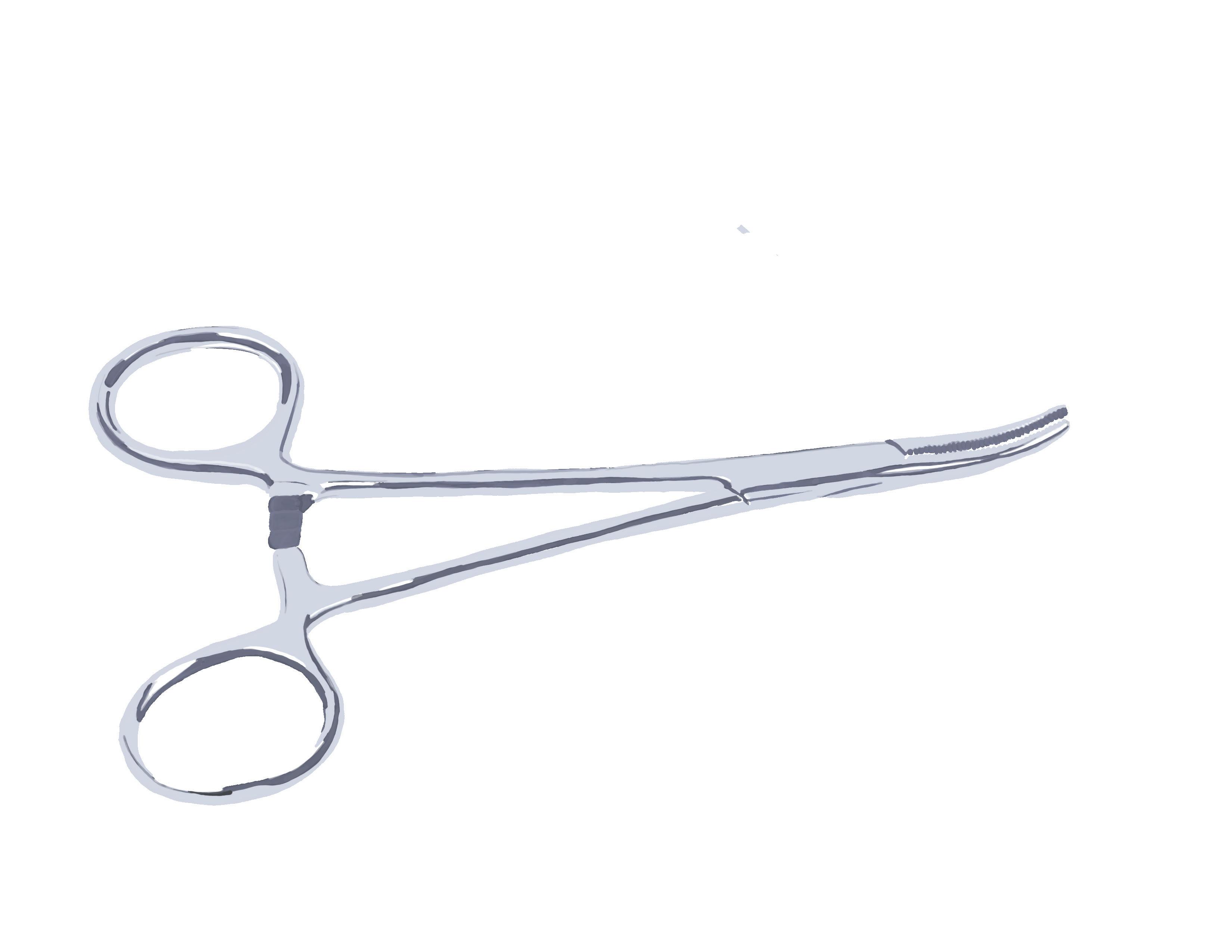

front cover artwork: The Catch

LucyZhengisasecondyearmedicalstudentat DukeUniversitySchoolofMedicine, withinterestsinpsychiatryandmedicalhumanities.

This artwork was inspired by a patient the artist met on the wards who was awaiting a heart transplant. The stories this patient shared of her life, her devoted partner, as well as her love for fishing came together in a piece that aims to capture not only the turbulence and uncertainty of healthcare, but also the joy of their lives and the warmth of the hope they have for the future. sites.duke.edu/voices