Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Wit & Wisdom® , Alexandria Plan™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2023 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder. Where expressly indicated, teachers may copy pages solely for use by students in their classrooms.

Printed in the USA A-Print

Module Summary 2 Essential Question 3

Suggested Student Understandings 3 Texts 3

Module Learning Goals 4 Module in Context............................................................................................................................... ........................ 6 Standards ............................................................................................................................... ....................................... 7 Major Assessments 9 Module Map 11

Focusing Question: Lessons 1–12

In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge?

Lesson 1 ............................................................................................................................... ............................................... 23

n TEXT: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Crisis Lesson 2 ............................................................................................................................... .............................................. 39

n TEXT: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Coordinate Adjectives

Lesson 3 57

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Words for Understanding Philadelphia in 1793 Lesson 4 69

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Words That Describe Smell Lesson 5 83

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Coordinate and Compound Adjectives

Lesson 6 ............................................................................................................................... .............................................. 97

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson ¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Coordinate and Compound Adjectives

Lesson 7 105

n TEXT: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: ques, quer, quir, quis Lesson 8 115

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy • “The Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia, 1793,” Harvard University Open Collections Program • “Yellow Fever: Symptoms and Treatment,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: cred Lesson 9 ............................................................................................................................... ............................................ 129

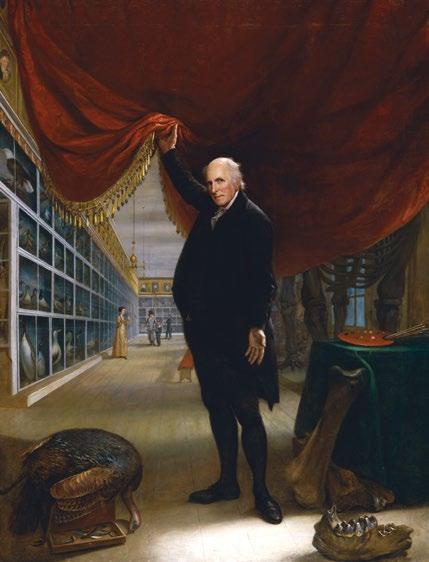

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy • The Artist in His Museum, Charles Willson Peale

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Skill with Compound and Coordinate Adjectives Lesson 10 143

n TEXTS: The Artist in His Museum, Charles Willson Peale • The Long Room, Interior of Front Room in Peale’s Museum, Charles Willson Peale • An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Words in Art and Literature

Lesson 11 159

n TEXTS: All Module Texts Lesson 12 165

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Figurative Language

Focusing Question: Lessons 13–22

What were the effects of the unfolding crisis on Philadelphia and its citizens?

Lesson 13 ............................................................................................................................... .......................................... 177

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • “2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation,” Emily Johnston

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Skirmish, battle, war Lesson 14 191

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • “Yellow Fever,” U.S. National Library of Medicine • “2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation,” Emily Johnston

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Explore Figurative Language: Similes

Lesson 15 ............................................................................................................................... ......................................... 205

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: –ence, –ent

Lesson 16 ............................................................................................................................... .......................................... 221

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Heroic Words

Lesson 17 233

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, History Making Productions

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: plac

Lesson 18 245

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • “Q & A,” Jim Murphy • “2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation,” Emily Johnston

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Formal and Informal Speech

Lesson 19 ............................................................................................................................... ......................................... 255

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • “2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation,” Emily Johnston

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Formal and Informal Speech

Lesson 20 265

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute with Formal and Informal Speech

Lesson 21............................................................................................................................... ........................................... 275

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment

Lesson 22 ............................................................................................................................... ......................................... 283

n TEXTS: All Module Texts

What

Lesson 23 289

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Calamity, mournful, melancholy

Lesson 24 301

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, History Making Productions

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Battalion

Lesson 25 309

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • “Invictus,” William Ernest Henley • “Invictus” (video), Morgan Freeman

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Citation Punctuation

Lesson 26 319

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Citation Punctuation

did the crisis reveal about Philadelphia’s citizens and society?

Lesson 27 329

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Citation Punctuation Lesson 28 339

n TEXTS: Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Fetid Lesson 29 347

n TEXTS: The Artist in His Museum, Charles Willson Peale • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson • An American Plague, Jim Murphy

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Illness Words Lesson 30 ............................................................................................................................... ........................................ 357

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Vilify, vilest Lesson 31 367

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine and Experiment with Strong Verbs Lesson 32 377

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute Strong Verbs

How did people respond to the crisis?

Lesson 33 ............................................................................................................................... ......................................... 385

n TEXTS: An American Plague, Jim Murphy • Fever 1793, Laurie Halse Anderson ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment Lesson 34 393

n TEXT: An American Plague, Jim Murphy Lesson 35 399

n TEXT: An American Plague, Jim Murphy Lesson 36 405

n TEXT: An American Plague, Jim Murphy Lesson 37 411

n TEXT: An American Plague, Jim Murphy

¢

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel: Peer Edit

What is the story of the year?

Lesson

n TEXTS: All Modules 1–4 Texts ¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Review

Appendix A: Text Complexity............................................................................................................................... ..... 425

Appendix B: Vocabulary ............................................................................................................................... ............... 429

Appendix C: Answer Keys, Rubrics, and Sample Responses 439

Appendix D: Volume of Reading 461

Appendix E: Works Cited 463

How could the city have changed so much? Yellow fever was wrestling the life out of Philadelphia, infecting the cobblestones, the trees, the nature of the people. Was I living through another nightmare?

—Laurie Halse AndersonHow do people respond to a crisis? What factors contribute to an individual’s response? How can these responses affect a city, citizens, and government?

Students investigate these questions by traveling back to one of the pivotal crises in American history: the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. As crises often do, this epidemic illuminated and altered realities of power, prejudice, and human fortitude, sparking transformation on both micro and macro levels. Study of this early American plague offers insight into the challenges crises can present to a society and a window into the many decisions, both small and large, that people must make to respond.

Fittingly, the module features deeply researched fictional and informational accounts. They spotlight disparate responses to the fever and spur students’ own research, uncovering patterns of human behavior driven by fear, compassion, an impulse to understand the unknown, and the human drive to survive and thrive.

In An American Plague, Jim Murphy develops content knowledge through a vividly detailed factual account of the epidemic. Students are immersed in eighteenth-century Philadelphia. They learn about medical practices that increased death rates, the young government’s panicked decision to adjourn, and the heroism of individuals like the Free African Society volunteers. Laurie Halse Anderson’s Fever 1793 intensifies the module’s historical immersion by fostering emotional investment. Readers of this novel experience the epidemic through the point of view of Mattie, a fourteen-year-old girl whose motivation must shift from avoiding chores to survival. Concurrent study of these texts cultivates meaningful understanding of the ways individuals can alleviate and exacerbate a crisis’s effects and of how writers of history and historical fiction use research to imbue their works with depth and truth.

By the time students encounter the End-of-Module (EOM) Task research essay, they are prepared to analyze and evaluate the ways Philadelphians responded to the epidemic, deepening their exploration of how times of crisis can affect citizens and society.

A single cause can have a wide range of effects. There are patterns of human behavior that can emerge in the midst of a crisis, driven by factors such as fear, compassion, an impulse to understand the unknown, and the will to survive. While each individual has the power to determine their own response to a crisis, social factors such as gender, race, and class can influence an individual’s experience of a crisis. Scientific knowledge is essential to effectively addressing medical crises. A crisis can serve as a catalyst for positive change in individuals, society, and medicine.

“Q & A,” Jim Murphy (http://witeng.link/0407)

“The Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia, 1793,” Harvard University Library Open Collections Program (http://witeng.link/0386)

“Yellow Fever,” U.S. National Library of Medicine (http://witeng.link/0399)

“Yellow Fever: Symptoms and Treatment,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://witeng.link/0387)

Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, History Making Productions (http://witeng.link/0412)

The Long Room, Interior of Front Room in Peale’s Museum, Charles Willson Peale (http://witeng.link/0391)

“Invictus,” William Ernest Henley (http://witeng.link/0413)

“2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation,” Emily Johnston (http://witeng.link/0398)

“Invictus” video reading, Morgan Freeman (http://witeng.link/0414)

Describe aspects of late eighteenth-century Philadelphian life, including living conditions, political structures, and social norms. Explain how the epidemic affected and was affected by these factors.

Explain how eighteenth-century medical practices and lack of scientific understanding contributed to the epidemic’s spread and deleterious effects, as well as how the epidemic provided an opportunity to deepen scientific understanding.

Analyze the impact that individuals had on the development of the crisis and the reciprocal impact that the crisis had on these individuals.

Describe the roles of race, gender, and social class in early American society, and analyze how these factors influenced individuals’ experiences of the crisis. Understand the purposes, benefits, and process of academic research.

Analyze how Mattie’s identity develops as she confronts the conflicts created by Fever 1793’s crisis setting (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Compare and contrast Anderson’s portrayal of the crisis with Murphy’s portrayal as a means of understanding how Anderson uses history in Fever 1793 (RL.7.9).

Analyze the impact of word choice and other devices, such as eyewitness accounts and primary documents, on establishing different perspectives on the crisis (RI.7.4).

Analyze how text structure can help develop ideas about yellow fever (RI.7.5).

Compare and contrast multiple informational texts about the crisis and determine each author’s point of view (RI.7.6, RI.7.9).

Form focused research questions and draw on several sources to answer them (W.7.7).

Effectively search for and select accurate and credible research sources (W.7.8).

Quote or paraphrase the data and conclusions of others, following a standard format for citation (W.7.8).

Clearly communicate research findings in an organized, appropriately detailed research essay (W.7.2, W.7.4).

Use technology to produce and publish writing and link to and cite sources (W.7.6).

Effectively communicate ideas in academic presentations and discussions about the yellow fever crisis, including multimedia components and visual displays to clarify claims and findings (SL.7.4, SL.7.5).

Listen to understand speakers’ insights, acknowledging new information and modifying views when appropriate (SL.7.1.d).

Analyze the main ideas and supporting details in diverse media and formats, and explain how the ideas clarify the crisis (SL.7.2).

Identify the function and correct punctuation of coordinate adjectives, and use them accurately and purposefully in writing (L.7.2.a).

Use common, grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of a word (L.7.4.b).

Consult general and specialized reference materials, both print and digital, to find the pronunciation of a word or determine or clarify its precise meaning or its part of speech (L.7.4.c).

Verify the preliminary determination of the meaning of a word or phrase (L.7.4.d).

Distinguish among the connotations (associations) of words with similar denotations (L.7.5.c).

Knowledge: Throughout the year, students explore the roles of individuals in society, analyzing how one’s societal context can influence experience and identity and vice versa. Module 1 introduced the concept of identity through stories of the rigidly hierarchical Middle Ages. Module 2 depicted individuals’ experiences during World War II. In Module 3, students analyzed the power of authority, words, and media to influence individuals’ thoughts and actions. Module 4 thrusts students into another survival context, an early American epidemic, prompting larger societal questions of how individuals respond to crisis, how crisis can affect individuals, and how a crisis can reveal inequalities or failures of humanity as well as people’s fortitude and generosity.

Reading: Students deepen the skills they developed in prior modules for analytical reading by examining literary and informational texts. Previous modules’ literary analyses focused heavily on tracing themes of identity development and coming of age. In Module 4, students require less scaffolding as they analyze the growth of Fever 1793’s young protagonist. Students also extend their skills by analyzing a novel and an informational text concurrently, comparing and contrasting their portrayals of the yellow fever to deepen understanding of both the crisis and author’s craft.

Writing: In Module 1, students gained narrative writing skills, and in Modules 2 and 3, students gained skills in using evidence and elaboration to support informative and argumentative writing. Here students expand their informative writing skills, particularly as they embark on the research process and generate research essays.

Speaking and Listening: Students participate in three Socratic Seminars, focusing on effectively expressing their ideas and listening to understand classmates’ insights. Additionally, students apply their skills to a new task that builds on their study of orators’ delivery techniques in Module 3: a research presentation.

RL.7.2 Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text.

RL.7.3 Analyze how particular elements of a story or drama interact (e.g., how setting shapes the characters or plot).

RL.7.9 Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors of fiction use or alter history.

RI.7.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the impact of a specific word choice on meaning and tone.

RI.7.5 Analyze the structure an author uses to organize a text, including how the major sections contribute to the whole and to the development of the ideas.

RI.7.6 Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author distinguishes their position from that of others.

RI.7.9 Analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic shape their presentations of key information by emphasizing different evidence or advancing different interpretations of facts.

W.7.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content.

W.7.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. (Grade-specific expectations for writing types are defined in standards 1–3 above.)

W.7.6 Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and link to and cite sources as well as to interact and collaborate with others, including linking to and citing sources.

W.7.7 Conduct short research projects to answer a question, drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions for further research and investigation.

W.7.8 Gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, using search terms effectively; assess the credibility and accuracy of each source; and quote or paraphrase the data and conclusions of others while avoiding plagiarism and following a standard format for citation.

L.7.2.a Use a comma to separate coordinate adjectives (e.g., It was a fascinating, enjoyable movie but not He wore an old[,] green shirt).

L.7.4.b Use common, grade-appropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of a word (e.g., belligerent, bellicose, rebel).

L.7.4.c Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to find the pronunciation of a word or determine or clarify its precise meaning or its part of speech.

L.7.4.d Verify the preliminary determination of the meaning of a word or phrase (e.g., by checking the inferred meaning in context or in a dictionary).

L.7.5.c Distinguish among the connotations (associations) of words with similar denotations (definitions) (e.g., refined, respectful, polite, diplomatic, condescending).

SL.7.1.d Acknowledge new information expressed by others and, when warranted, modify their own views.

SL.7.2 Analyze the main ideas and supporting details presented in diverse media and formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively, orally) and explain how the ideas clarify a topic, text, or issue under study.

SL.7.4 Present claims and findings, emphasizing salient points in a focused, coherent manner with pertinent descriptions, facts, details, and examples; use appropriate eye contact, adequate volume, and clear pronunciation.

SL.7.5 Include multimedia components and visual displays in presentations to clarify claims and findings and emphasize salient points.

RL.7.10

By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

RI.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

L.7.6 Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

1. Complete a graphic organizer and short responses to compare and contrast Fever 1793 with An American Plague and your own research.

2. Deliver a five-minute presentation explaining an effect of the crisis, using examples from one or both core texts.

3. Using evidence from An American Plague, write a short essay explaining one thing that Philadelphians learned about their society or government as a result of the crisis.

Engage in and reflect on the research process. Synthesize and cite information from multiple sources. Demonstrate understanding of the epidemic’s context.

Demonstrate understanding of how responses to the crisis affected people in different ways. Cite evidence from multiple texts, including An American Plague

Generate informative writing. Demonstrate understanding of what the crisis revealed about Philadelphia.

Demonstrate understanding of how the epidemic affected particular segments of society.

RL.7.1, RL.7.9, RI.7.1, W.7.7, W.7.9, W.7.10

RI.7.1, RI.7.3, SL.7.4, SL.7.5, SL.7.6

RI.7.1, RI.7.2, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.9

1. Read chapter 7 of Fever 1793. Then answer multiple-choice and short-response questions to analyze theme, story elements, and word choice.

2. Read Jim Murphy’s interview. Then answer multiple-choice and short-response questions to analyze the text’s structure, determine the author’s point of view, and analyze how he distinguishes his position from that of others.

3. View the documentary segment on the Free African Society. Then write a paragraph analyzing how the documentary’s portrayal of the FAS differs from Murphy’s.

Analyze the context of the crisis. Analyze responses to the crisis.

Analyze how the setting shapes events and characters, specifically the roles of class and gender in 1793 and in the unfolding crisis.

Analyze the structure of an informational text. Analyze Murphy’s perspective on the research process.

RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RL.7.3, RL.7.4, L.7.4.b, L.7.5.c, W.7.10

RI.7.1, RI.7.4, RI.7.5, RI.7.6, W.7.10, L.7.4.c, L.7.4.d

Generate informative writing. Integrate facts from An American Plague. Demonstrate understanding of the Free African Society’s role in the crisis.

RI.7.1, RI.7.9, W.7.10, SL.7.2

1. Evaluate Dr. Benjamin Rush’s role in the crisis. Evaluate medical responses to the crisis.

Integrate research from An American Plague and online sources.

2. In the role of eighteenth-century Philadelphians holding a post-crisis town hall meeting, reflect on the epidemic’s effects and on changes the city should make to prepare for future epidemics.

RI.7.1, RI.7.3, SL.7.1, SL.7.6, L.7.6

Formulate opinions about responses to the crisis.

Analyze what the crisis revealed about power and social divisions in eighteenth-century Philadelphia.

Integrate evidence from An American Plague.

3. Analyze the story of the year. Reflect on themes and central ideas from all four modules, including the central ideas discussed in Module 4’s EOM Task.

SL.7.1, SL.7.6, L.7.6

RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RI.7.1, RI.7.2, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

Write a research essay explaining two or three ways that members of a selected group of Philadelphians responded to the yellow fever crisis. Evaluate whether these responses were helpful, harmful, or both.

Introduce the topic and state the thesis.

Explain two to three responses to the crisis.

Develop each response by synthesizing the content of your chosen sources.

Explain whether these responses were helpful, harmful, or both, including and elaborating on relevant, accurate, and sufficient evidence.

Include headings or graphics to aid comprehension.

Cite sources consistently and correctly.

Provide a conclusion that supports the essay.

Use words, phrases, and clauses to make transitions, connect ideas, and to show how ideas are related to each other.

Maintain a formal style featuring precise language and domain-specific vocabulary.

RI.7.1, RI.7.3, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.5, W.7.6, W.7.8, W.7.9, L.7.2.a

Demonstrate understanding of academic, text-critical, and domain-specific words, phrases, and/or word parts.

Acquire and use grade-appropriate academic terms.

L.7.4.b

Acquire and use domain-specific or text-critical words essential for communication about the module’s topic.

L.7.6

* While not considered Major Assessments in Wit & Wisdom, Vocabulary Assessments are listed here for your convenience. Please find details on Checks for Understanding (CFUs) within each lesson.

Focusing Question 1: In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge?

1 Fever 1793 Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about Fever 1793?

2 Fever 1793 Organize

What is happening in Fever 1793?

Examine

Why is using coordinate adjectives separated by commas important?

3 An American Plague Fever 1793 Organize

What is happening in An American Plague and in Fever 1793?

4 Fever 1793

An American Plague

Organize

What is happening in An American Plague and in Fever 1793?

Experiment

How do choosing a research topic and formulating a research question work?

Formulate questions and observations about Fever 1793 (RL.7.1). Understand the connotation and denotation of the word crisis (L.7.5.c).

Describe the protagonist of Fever 1793, explaining how the setting and other characters shape her identity (RL.7.3).

Examine and identify coordinate adjectives in context (L.7.2.a).

Compare and contrast how Murphy and Anderson use historical details and research in their writing about the yellow fever epidemic (RL.7.9).

Employ varied strategies to define content-specific words (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b, L.7.4.c, L.7.5.b).

Analyze how the setting of Fever 1793 shapes the character of Mattie (RL.7.3, W.7.10)

Compare and contrast how Murphy and Anderson use historical details and research in their writing about the yellow fever epidemic (RL.7.9).

Identify a topic and generate a focused question for further research (W.7.7).

Deepen understanding of words describing smell by considering and defining multiple related words (L.7.4.c, L.7.5.b).

5 Fever 1793

An American Plague

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character reveal about society and social class in Fever 1793?

Experiment

How does using search terms to investigate a research question work? Examine

Why are coordinate adjectives separated by commas and compound adjectives punctuated with hyphens important?

Summarize the key developments in Fever 1793, chapter 6 (RL.7.2).

Analyze how Anderson develops ideas about societal divisions through the interplay among the characters, plot, and setting (RL.7.3).

Use search terms to identify sources relevant to investigating focused research questions on a topic related to the module’s content and texts (W.7.7, W.7.8).

Examine coordinate and compound adjectives and their punctuation, and consider their effect in a text (L.7.2.a).

6 NR An American Plague Fever 1793

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character, plot, and setting in Fever 1793 reveal?

Experiment

How does using and correctly punctuating coordinate and compound adjectives work?

Read the next chapter of a novel, and demonstrate comprehension by summarizing the text, analyzing its themes, analyzing the interactions among characters, plot, and setting, and considering relevant words with similar denotations and different connotations (RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RL.7.3, RL.7.4, L.7.4.b, L.7.5.c, W.7.10).

Describe characters, scenes, and settings from Fever 1793 using correctly punctuated coordinate and compound adjectives (L.7.2.a).

7 Fever 1793 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character, plot, and setting in chapters 8 and 9 of Fever 1793 reveal?

Examine the changes in the main character resulting from her circumstances and the events developing around her (RL.7.3).

Use the roots ques, quer, quir, quis to define and use related words (L.7.4.b).

Focusing Question 1: In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals8 Fever 1793

An American Plague

“The Yellow Fever Epidemic in Philadelphia, 1793”

“Yellow Fever: Symptoms and Treatment”

9 Fever 1793

An American Plague

The Artist in His Museum

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the characters’ actions and reactions reveal in Fever 1793?

Examine

Why is using multiple credible, accurate sources important?

Assess the credibility and accuracy of sources (W.7.8).

Use the root cred to define and use related words (L.7.4.b).

10 The Artist in His Museum

The Long Room, Interior of Front Room in Peale’s Museum

An American Plague Fever 1793

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of historical fact and detail reveal in An American Plague, chapter 3?

Execute

How do I use credible, accurate sources in investigating a research question?

Execute

How do I use and correctly punctuate coordinate and compound adjectives to add description in informational writing?

Determine the meaning of words and phrases used in An American Plague, and analyze their impact (RI.7.4).

Determine the author’s purpose, based on an analysis of content and craft (RI.7.6).

Compare and contrast how Murphy and Anderson use historical details and research (RL.7.9).

Execute skill in using and correctly punctuating compound and coordinate adjectives (L.7.2.a).

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Charles Willson Peale’s selfportrait reveal?

Experiment

How does note-taking work?

Analyze and respond in writing to a portrait (SL.7.2, W.7.10).

Use varied strategies to define words used in art and literature (L.7.4, L.7.5.b).

11 All Module Texts Know

How do various sources build my knowledge to answer my research question?

Identify and take notes on relevant information from multiple, credible print and digital sources (W.7.8).

Focusing Question 1: In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning GoalsFocusing Question 1: In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge?

Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

12 FQT All Module Texts Know

How do the module’s texts build my knowledge of the context (geographical, historical, and societal) of the yellow fever epidemic of 1793?

Compare and contrast the historical basis of a fictional account with an informational account (RL.7.1, RL.7.9, RI.7.1, W.7.7, W.7.9, W.7.10).

Demonstrate understanding of figurative language (L.7.5).

Focusing Question 2: What were the effects of the unfolding crisis on Philadelphia and its citizens?

Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

13 Fever 1793

“2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Mattie’s characterization and responses to problems reveal in chapters 11 and 12 of Fever 1793?

14 Fever 1793

“Yellow Fever”

“2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of scientific information about yellow fever reveal in the texts?

Examine

Why are delivery techniques important in an oral presentation?

Analyze how Mattie and her relationship with her grandfather change as a result of the crisis (RL.7.3).

Understand the connotations and denotations of the words skirmish, battle, and war and their impact in Fever 1793 (L.7.5.c).

Experiment

How does delivering a presentation work?

Determine the meaning of technical and medical terms in a scientific article, and analyze how the article’s structure affects the development of its main ideas (RI.7.4, RI.7.5).

Present findings about an aspect of yellow fever, emphasizing salient points and using effective presentation techniques (SL.7.4).

Interpret and analyze similes in Fever 1793 (L.7.5.a).

15 Fever 1793

An American Plague

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of text structure and visuals reveal in An American Plague and the thesis presentation?

Examine Why are visuals important? Experiment How do visuals work?

Determine the meaning of words and phrases used in chapter 4 of An American Plague, and analyze how the chapter’s structure contributes to the development of its central idea(s) (RI.7.4, RI.7.5).

Design an effective visual for a presentation about chapter 4 (SL.7.5).

Apply understanding of the suffixes –ence and –ent to define words (L.7.4.b).

16 Fever 1793

An American Plague

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of individuals’ roles reveal in Fever 1793 and An American Plague?

Examine Why are direct quotations, paraphrasing, and summarizing important in research papers and presentations?

Determine the meaning of words and phrases used to describe individuals in chapter 7 of An American Plague, and analyze how the chapter’s structure impacts the development of its central ideas (RI.7.4, RI.7.5).

Explain Murphy’s perspective on key individuals from the volunteer committee (RI.7.6).

Deepen understanding of adjectives used to describe heroic figures from the crisis (L.7.4).

17 Fever 1793

An American Plague Philadelphia: The Great Experiment

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the crisis’s effects on people and their relationships reveal in these texts?

Experiment

How do direct quotations, paraphrasing, and summarizing work in research papers and presentations?

Analyze the central idea and supporting details Philadelphia: The Great Experiment presents about Stephen Girard (RI.7.2, RI.7.6, SL.7.2).

Compare and contrast the differing perspectives and accounts of Murphy and the filmmakers on Stephen Girard (RI.7.6, RI.7.9).

Use the root word plac to predict the meaning of words and confirm predictions using a dictionary (L.7.4.b, L.7.4.d).

Focusing Question 2: What were the effects of the unfolding crisis on Philadelphia and its citizens? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals18 NR An American Plague “Q & A”

“2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the research process reveal in Murphy’s texts?

Examine

Why is using multiple sources to verify factual information important? Examine

Why is using formal speech in an academic presentation important?

19 Fever 1793

“2014 Three Minute Thesis Winning Presentation”

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of literary techniques reveal in chapters 18 and 19 of Fever 1793?

Experiment

How does using formal speech in an academic presentation work?

Determine and confirm the meaning of words and phrases in the article, analyze the article’s structure, determine the author’s point of view, and analyze how he distinguishes his position from that of others (RI.7.1, RI.7.2, RI.7.4, RI.7.5, RI.7.6, W.7.10, L.7.4.c, L.7.4.d).

Analyze the impact of formal versus informal language in a presentation (L.7.3.a).

Analyze how characters, setting, and plot interact in a key scene from Fever 1793 and what that interaction reveals about Mattie, Grandfather, or the effects of the crisis (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Identify elements of formal language needed for a presentation (L.7.3.a).

20 FQT All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how the epidemic affected Philadelphians?

Execute

How do I use my presentation skills to plan a presentation about one of the crisis’s effects?

Execute

How do I use my knowledge of formal speech to plan how I will deliver my presentation?

Identify and organize the most salient points for a presentation about a chosen effect, and generate ideas for supporting visuals (SL.7.4, SL.7.5).

Apply strategies for using formal language to the Focusing Question Task presentations (L.7.3.a).

Focusing Question 2: What were the effects of the unfolding crisis on Philadelphia and its citizens? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals21 FQT VOC

All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how the epidemic affected Philadelphians?

Execute

How do I use my presentation skills to plan a presentation about one of the crisis’s effects? Execute

How do I use my presentation skills to share about the crisis’s effects?

Present findings about an effect of the yellow fever crisis, emphasizing salient points; including relevant descriptions, facts, details, and examples; using appropriate presentation skills; and supporting the presentation with multimedia components and visual displays (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, SL.7.4, SL.7.5, SL.7.6).

Analyze a research presentation’s main ideas and supporting details, and explain how that presentation clarifies understanding of an effect of the crisis (SL.7.2).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-level vocabulary and of how to use affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of words or phrases (L.7.4.b, L.7.6).

22 FQT All Module Texts Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how the epidemic affected Philadelphians?

Execute

How do I use my presentation skills to share about the crisis’s effects?

Present findings about an effect of the yellow fever crisis, emphasizing salient points; including relevant descriptions, facts, details, and examples; using appropriate presentation skills; and supporting the presentation with multimedia components and visual displays (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, SL.7.4, SL.7.5, SL.7.6).

Analyze a research presentation’s main ideas and supporting details, and explain how that presentation clarifies understanding of an effect of the crisis (SL.7.2).

Focusing Question 2: What were the effects of the unfolding crisis on Philadelphia and its citizens? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals23 Fever 1793

An American Plague

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the subject of morale reveal in Fever 1793 and An American Plague?

Examine

Why is synthesizing evidence important?

Synthesize evidence from Fever 1793 and An American Plague to describe the epidemic’s effects on Philadelphia’s ability to function and on the city’s morale (RI.7.3, W.7.10).

Understand the words calamity, mournful, and melancholy by exploring their context in An American Plague (L.7.4.a).

24

NR Fever 1793

An American Plague Philadelphia: The Great Experiment

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of the Free African Society reveal in Fever 1793, An American Plague, and Philadelphia: The Great Experiment?

25 An American Plague Fever 1793

“Invictus” William Ernest Henley

“Invictus” (video) reading, Morgan Freeman

26 An American Plague Fever 1793

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of characterization reveal in Fever 1793 and “Invictus”?

Examine

Why is the structure of a research paper important?

Examine

Why is correctly punctuating citations important?

Compare and contrast the Free African Society’s depiction in An American Plague and in the documentary clip (RI.7.1, RI.7.9, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.9, SL.7.2).

Analyze Murphy’s use of the word battalion to describe the Free African Society by exploring context, reference materials, and its Latin root (L.7.4).

Compare “Invictus” and Fever 1793 to analyze how crisis can reveal character (RL.7.2, RL.7.4).

Explain how to punctuate citations (L.4.2.b*, W.7.8).

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of Dr. Rush’s role reveal in Fever 1793 and An American Plague?

Experiment

How does conducting and synthesizing research work? Experiment How does punctuating citations work?

Evaluate Dr. Rush’s role in the epidemic based on research (RI.7.3, W.7.7).

Correctly punctuate and cite quotations in a creative writing piece (L.4.2.b*, L.7.2, W.7.8).

Focusing Question 3: What did the crisis reveal about Philadelphia’s citizens and society? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals27 SS An American Plague

Fever 1793

Distill

What was Dr. Rush’s role in the epidemic?

Execute

How can I effectively explain my ideas in a Socratic Seminar?

Experiment

How does synthesizing quoted and paraphrased information in a research paragraph work?

Execute

How can I use correct citation punctuation in a research paragraph?

Engage in a collaborative conversation about Dr. Rush’s role in the crisis, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, and using formal English as appropriate (RI.7.3, SL.7.1, SL.7.6, L.7.6).

Use quoted and paraphrased information from multiple sources to analyze and evaluate Dr. Rush’s role in the crisis (RI.7.3, W.7.2, W.7.7, W.7.8).

Edit a research paragraph to ensure correct citation punctuation (L.4.2.b*, W.7.8).

28 Fever 1793

An American Plague

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of point of view reveal in Fever 1793?

Experiment

How do introductions and conclusions work?

Analyze how Anderson develops characters’ points of view to portray the epidemic’s differing effects (RL.7.3, RL.7.6).

Introduce and conclude a research paragraph describing Dr. Rush’s role in the crisis (RI.7.3, W.7.2.a, W.7.2.f).

Deepen understanding of the word fetid by distinguishing between its connotation and those of other smell words (L.7.5.c).

29 The Artist in His Museum

Fever 1793

An American Plague

Distill

What are the essential meanings of Fever 1793 and The Artist in His Museum?

Analyze a theme from Fever 1793 (RL.7.2). Distinguish among the connotations of illness words from the core texts (L.7.5.c).

Focusing Question 3: What did the crisis reveal about Philadelphia’s citizens and society? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals30 An American Plague Fever 1793

Distill

What are the central ideas of An American Plague?

Examine

Why is formatting important? Experiment

How does formatting work?

Identify common attitudes toward government leaders, the lower class, and the Black community in the epidemic’s aftermath, and analyze what these revealed about power and social divisions in eighteenth-century Philadelphia (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, RI.7.5).

Craft headings that aid comprehension of the crisis’s aftermath (W.7.2.a).

Deepen understanding of the words vilify and vilest using Latin roots and reference materials (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b, L.7.4.c, L.7.4.d).

31 SS An American Plague Fever 1793

Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of what the crisis revealed about Philadelphia’s citizens and society?

Excel

How can I improve my speaking and listening skills? Examine

Why are strong verbs important? Experiment

How do strong verbs work?

Engage in a collaborative conversation about what the crisis revealed about power and social divisions in eighteenthcentury Philadelphia, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6, L.7.6).

Use strong verbs to ensure precise, concise language (L.7.3.a).

Focusing Question 3: What did the crisis reveal about Philadelphia’s citizens and society? Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning GoalsLesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

32

FQT An American Plague Fever 1793

Know

How does An American Plague build my knowledge of what the crisis revealed about Philadelphia’s citizens and society?

Execute

How can I use elements of strong informative writing in my short essay?

Execute

How can I use strong verbs in my Focusing Question Task response?

Write a short essay explaining one thing that Philadelphians learned about their society or government after the crisis (RI.7.1, RI.7.2, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.9).

Revise Focusing Question Task 3, using strong verbs to ensure precise, concise language (L.7.3.a).

Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

33

EOM VOC

An American Plague Fever 1793

Know

How does An American Plague build my knowledge of individuals’ responses to the crisis?

Execute

How can I use details from An American Plague in my research essay?

Using An American Plague, research and evaluate how members of a particular group responded to the crisis (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, W.7.8).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-level vocabulary and of how to use affixes and roots as clues to the meaning of words or phrases (L.7.4.b, L.7.6).

34

EOM An American Plague Know

How do online sources build my knowledge of individuals’ responses to the crisis?

Execute

How can I use online sources in my research essay?

35

EOM An American Plague Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of individuals’ responses to the crisis?

Execute

How can I organize and draft my research essay?

36

Execute

Research and evaluate how members of a particular group responded to the crisis, using technology to cite sources and collaborate with others (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, W.7.6, W.7.8).

Draft an essay that synthesizes research to discuss and evaluate responses to the crisis (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.6, W.7.8, W.7.9, L.7.2.a).

EOM

How do these texts build my knowledge of individuals’ responses to the crisis?

How can I use the elements of strong informative writing in my research essay?

Finish drafting an essay that synthesizes research to discuss and evaluate responses to the crisis (RI.7.1, RI.7.3, W.7.2, W.7.4, W.7.6, W.7.8, W.7.9, L.7.2.a).

Focusing Question 4: How did people respond to the crisis?

Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

37 An American Plague Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of how times of crisis can affect citizens and society?

Excel

How can I improve my research essay? Excel

How do I improve style and conventions in my research essay?

Provide and receive feedback to revise EOM Task essays to meet criteria for success (W.7.5).

Demonstrate use of precise and concise language, purposeful varied sentence structures, and a style appropriate for informative writing (L.7.1.b, L.7.2.a, L.7.2.b, L.7.3.a, L.7.6, W.7.5).

Focusing Question 5: What is the story of the year?

Lesson Text(s) Content Framing Question Craft Question(s) Learning Goals

38 SS All Module 1–4 Texts Know

How do this year’s texts build my knowledge?

Engage in a collaborative conversation about the year’s themes, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, and using formal English as appropriate (RL.7.2, RI.7.2, SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Review and deepen understanding of words, phrases, and morphemes learned throughout all four modules (L.7.6).

33 34 2 1 3 5 6 7 15 26 11 19 30 9 17 28 13 24 21 32 8 16 27 12 23 20 31 10 18 29 14 25 22 4 35 36 37 38 WIT & WISDOM®

FOCUSING QUESTION: LESSONS 1–12

TEXT G7 M4 Lesson 1 © 2023 Great Minds PBC

Welcome (4 min.)

Launch (8 min.) Learn (58 min.)

Notice and Wonder (46 min.)

Identify Research Questions (12 min.)

Land (3 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (2 min.)

Assign the Volume of Reading

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Crisis (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

Reading RL.7.1

Writing W.7.7, W.7.8

Speaking and Listening SL.7.1, SL.7.2

Language L.7.5.c

MATERIALS

Handout 1A: Research Overview Chart paper

Six large cards or pieces of cardstock paper

Formulate questions and observations about Fever 1793 (RL.7.1).

Complete a Notice and Wonder T-Chart.

Understand the connotation and denotation of the word crisis (L.7.5.c).

Distinguish among words with similar denotations to crisis, and describe an appropriate context in which to use the word crisis

How can times of crisis affect citizens and society?

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–12

In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 1

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about Fever 1793?

Lesson 1 begins Module 4’s exploration of a society in crisis: Philadelphia during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. Students begin the module’s core literary text, Fever 1793, noticing and wondering as the author introduces the setting, the protagonist, Mattie, and other important characters, and sets the plot events into motion with the shocking death of Polly at the end of chapter 2. This lesson also begins Module 4’s focus on the research process, as students begin to identify topics and questions for possible investigation.

4 MIN.

Instruct pairs to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What challenge or challenges has a character faced in one of the books we have read this year? How did the character respond?”

8 MIN.

Post the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and Content Framing Question.

Invite students to share responses to the Welcome questions and then connect these ideas to the Module’s Essential Question: “How can times of crisis affect citizens and society?”

Ask: “Did the challenge that the character faced rise to the level of a crisis? Explain why or why not.”

The Deep Dive for this lesson provides an opportunity for a deeper exploration of the word crisis. At this point in the lesson, make sure students understand its meaning.

If students are unfamiliar with the word, provide the following definition.

crisis (n.) A time of serious difficulty or danger.

A period or situation of instability or upheaval, for a society or an individual.

The moment when a disease or fever turns better or worse.

emergency, disaster, catastrophe

If the challenge that the character faced was not a crisis, challenge students to identify another real-life person or fictional character who faced a crisis. Ask: “How did that crisis affect the people involved?”

Tell students that in this module, they will reflect on the Essential Question using one specific historical crisis as their focus of study. Preview that in this lesson, they will read the opening chapters of Fever 1793 and begin to discover the setting of the crisis

58 MIN.

46 MIN.

Ask students to examine the front cover of Fever 1793, and ask: “What do you notice and wonder about the front cover?”

n The girl’s eye is yellow. It looks like something is very wrong.

n The title is Fever 1793. I wonder if it takes place in 1793.

n The review says, “The plot rages like the epidemic itself.” I don’t know what an epidemic is.

n The book won an award. I hope that means it will be good!

Instruct students to create a Notice and Wonder T-Chart in their Response Journal. Explain that as they listen to the text read aloud, they should follow along in their texts and consider what they notice and wonder.

At pause points in the Read Aloud, students identify and record key details and questions about the book.

Read the first page, stopping after “… there’s work to be done” (1).

After giving students time to record, ask: “What did you notice and wonder?”

n The chapter starts with a date. I think that is when the story begins: August 16th, 1793.

n The chapter opens with a quotation about the city of Philadelphia. I think this is where the story is going to take place—in Philadelphia.

n I noticed that they live above a coffeehouse. I thought people only drank tea in the olden days.

n I wonder who Polly is.

Read the next page, ending with: “No balloon trips for me” (2). Pause for students to note what they noticed and wondered. Ask: “What did you notice and wonder in this part?”

n It seems like the girl’s relationship with her mom is not easy.

n I’m still not sure who Polly is. Is it her sister?

n I wonder what war the mother lived through.

n It sounds like the girl is not a perfect, hard worker like her mother. She wants to lie in bed and daydream.

n Why does the author keep mentioning the mosquitoes?

n I wonder what Blanchard’s giant yellow balloon was. Did they have hot-air balloons then?

As students share their questions, address or have students address those necessary for students to understand the text, such as those about a vocabulary word. However, let students know that the book will address many of their questions, and they will have a chance to research to find out more, so it is fine for them to keep wondering about some of them.

Read page 3. Give students time to record what they notice and wonder. Instruct them to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What did you notice in this section?”

n We are learning a lot about the girl, Matilda. She does not think her mom appreciates her. She is growing—she hits her head, and her clothes are too small. She does not seem too worried about how she looks. She decides not to clean up in the washbasin.

Continue reading to the end of the chapter. After students have had time to record, ask what they noticed in this last section of the chapter.

n Now we know who Polly is—she is a servant.

n And the balloon must have been a hot-air balloon.

n There are a lot of details to show this is taking place a long time ago. The streets are filled with horses and carriages. A pig is running in the streets.

n Matilda is not scared of things. She picks up the mouse and throws it out the window. She wants to get away.

Then ask students about any questions the text raised.

n There were some words I didn’t know, like teemed, anvil, and wharves

n What does a blacksmith do?

n When Matilda looks out, she sees the State House “where the Congress met” (4). I thought Congress met in Washington, DC. Did Philadelphia used to be the capital?

n She says that Nathaniel Benson did not laugh at her. I wonder who he is.

n I wonder if Matilda is a real person from history.

If students have not yet brought it up, ask: “What did you notice about the way the story is being told? How is it similar to or different from other books we have read?”

n Matilda is telling the story herself, from the first-person point of view.

n This is a little bit like Castle Diary because it is told in the first person.

n It also seems a little like The Midwife’s Apprentice because it is about a girl and it takes place a long time ago. I think it is historical fiction.

Now, tell students that you will read all of chapter 2 aloud while they follow along and continue to notice and wonder.

Read aloud the chapter while students follow along. (Allow about ten minutes for this ReadAloud. Or, play aloud from an audiobook version of the novel.)

Because of the volume of reading in this module and the amount of class Read Alouds, you may want to use an audiobook version of the core texts to share with your students. Audiobooks can be helpful as models of strong, fluent oral reading and can help students engage in the text’s ideas or story.

As you read, clarify potentially challenging vocabulary by reading the word or phrase as you encounter it, briefly defining it in context, rereading the word or phrase, and continuing on. For example, explain that the word grippe on page 6, which the mother defines as “a sleeping sickness,” is a word people of the time used to describe a mild virus or flu.

Then, ask students in small groups to choose one of the following questions to discuss. Be sure that at least one group chooses each question.

What did you notice and wonder about the narrator of the story and her family?

What did you notice and wonder about what it was like to be a girl or a woman in 1793?

What did you notice and wonder about the way Anderson develops the plot in this chapter?

What did you notice and wonder about what it was like to be an African American in Philadelphia in 1793?

What did you notice and wonder about the city of Philadelphia and its citizens?

If students seem to be struggling, offer hints like the following:

Draw a conclusion from the narrator’s daydreams on page 12.

Notice the quotation that opens the chapter. Think about what the statement, “a coffeehouse was a respectable business for a widow” (7), means.

Contrast the family’s discussion on page 10 of where Polly might be with the chapter’s conclusion on page 13.

Reread pages 8—9 about Eliza.

Think about who Washington was and why he might live there.

After about five minutes of small-group discussion, come together as a whole group for each group to share their findings with their classmates.

Provide time for students to add notes to their Notice and Wonder T-Charts.

12 MIN.

Tell students that as they continue reading Fever 1793 and learning more about the developing crisis, they will also build skills in research.

Ask: “What kinds of historical details does Anderson include in chapters 1 and 2, and what do those details suggest about the kind of research she probably did in order to write Fever 1793?”

n She describes what Mattie was wearing, so she must have researched clothes from the time. Maybe she looked at old paintings.

n She starts the chapters with quotations, so she must have read books written at that time.

n The author describes the city of Philadelphia. She must have visited the city, or at least studied maps to know the layout of the streets and rivers and the buildings.

n She must have read a lot of history books so that she could imagine life at that time—with a pig running in the streets, a blacksmith, the horses in the streets.

Invite volunteers to share what they know about the process used for the kind of research that Anderson engaged in (that is, source-based research, looking at primary and secondary visuals and texts, rather than scientific or experimental research).

n You start by identifying a topic for your research or asking a question you want to answer.

n Then you look for information about your topic or to answer your question.

n To research, you might look in the library or search online for sources. If you were doing science research, you would set up an experiment.

n Then you have to evaluate what you find. Is it true? This is just like how you would redo your experiment to double check that it worked.

n Once you have your sources, you take notes.

n You might go back and look for more sources if you still have questions.

n Then you write a paper or present what you learned.

Distribute Handout 1A. Create and display an anchor chart (on chart paper or using available technology) to provide an overview for students, as in Section 1 of the handout.

Step 1: Identify a topic, and ask a research question.

Step 2: Seek information to answer the question.

Step 3: Evaluate sources.

Step 4: Read and take notes.

Step 5: Synthesize the research findings.

Step 6: Integrate and credit sources.

Step 7: Share the research.

An anchor chart provides a shared resource for reference. Keep this anchor chart posted throughout the module to help students keep the big picture in mind as they learn skills involved in research. Additional anchor charts will be used in the module to capture the characteristics of specific elements of research (such as research questions) and to record ideas for research topics and questions. Determine a system that will work for you to record and keep these anchor charts for display throughout the module.

Incorporating students’ earlier comments, briefly review the steps of research. Clarify that although the handout uses the word steps and lists those in order, research is not linear. Researchers do not always go through steps in order but may instead go back and forth as needed.

Provide a minute or two for students to make any additional notes to the handout, or ask clarifying questions. Tell students that they will continue using this handout throughout this module but will do so gradually, learning about one or two steps at a time.

Having students take notes on the handout throughout the lessons will help them solidify their understanding of skills involved in research and give them a meaningful opportunity to practice note-taking. However, if students struggle with note-taking or time is limited, consider making a new version of each section of Handout 1A with the notes filled in from the class discussion and creation of class charts. Make copies for students to keep.

Explain that although research is not always done in sequential steps, research typically begins with asking a question or questions about which the researcher is curious or interested. Tell students that in this lesson, they will start this way.

Ask students to go back to their Notice and Wonder T-Charts and think about which questions will likely be answered as they continue reading, which questions can be answered by asking a friend or checking in a dictionary, and which questions can most likely only be answered through outside research.

Invite students to share ideas as a whole group.

n Questions that might be answered by the book have to do with the characters and the story. For instance, I want to find out what happened to Polly.

n Questions about words might be something I would ask a friend or check a dictionary. I wasn’t sure what an apothecary was.

n Research questions might have to do with Philadelphia or the time period of the book.

Organize students into small groups, and ask them to brainstorm and list more questions in the last category—those about ideas, people, places, or events in chapters 1 and 2 that might be interesting to investigate through research.

Provide time, at least five minutes, for the group to generate multiple ideas of research topics and questions based on what they read in chapters 1 and 2.

If students need help getting started, model one or more examples for the whole group. Encourage students to look back at their Notice and Wonder T-Charts for the questions they asked while reading.

Come back together as a whole group and share ideas.

n The first chapter is named, “August 16th, 1793.” What was happening on this day in 1793?

n The opening quotation for chapter 1 talks about the city of Philadelphia. What was Philadelphia like in 1793?

n Mother talks about “the War” on page 2. What war was it? Who fought in the war? Where and why was the war fought? Page 7 calls it “the War for Independence.”

n Matilda daydreams about “Blanchard’s giant yellow balloon” on page 2. Who was Blanchard? What was the balloon?

n On page 4, Matilda looks out at the rooftop of the State House “where the Congress met.” I thought Congress met in Washington, DC. Why was Congress meeting in Philadelphia? Page 7 says President Washington’s house was there, too.

n The girl’s family owns a coffeehouse. I thought people drank tea in the olden days and coffee shops became popular more recently. Were coffeehouses popular a long time ago in the United States?

n If I were a scientist, I might want to find out why people were getting sick close to the river.

n Eliza was a free Black woman. Chapter 2 says, “Philadelphia was the best city for freed slaves or freeborn Africans” (8). Did they have slavery in Philadelphia? What was life like for free Black citizens then?

As students share, create and display a Research Topics and Questions Anchor Chart (on chart paper or using available technology) that can be displayed, refined, and added to in future lessons. For example:

Topic Research Question

Philadelphia, 1793 What was Philadelphia like in 1793? What were people’s lives like?

The United States Capital When and why was the United States capital in Philadelphia?

Cook’s Coffeehouse Were coffeehouses common and important in the United States in the 1700s?

The Epidemic Why was yellow fever more likely to spread near water?

African Americans in Early America Was there slavery in early Philadelphia? What was life like for free Black citizens?

NOTE

In the next lesson students will learn in more detail what constitutes a strong research question. At this point, record students’ questions without worrying about whether they may be too broad or unanswerable. Do point out the distinction between the Research Topic and the Research Question. Research might be conducted about the topic of African American experience in colonial America, but a research question is more focused: “What was life like for free Black citizens in Philadelphia in the 1790s?” A topic can be more general while a research question should point the researcher in a more focused direction.

3 MIN.

Have students think about their understanding of the word crisis. Then ask students to complete an Exit Ticket in response to this question: “What is one detail from chapter 1 or 2 that seems to foreshadow a coming crisis?”

Wrap2 MIN.

Distribute and review the list of additional texts from Appendix D: Volume of Reading and the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions. Explain that the list contains books with further information about topics discussed in the module. Tell students that they should consider the reflection questions as they independently read any additional texts and respond to them when they finish a text.

TEACHER NOTE

Students may complete the reflections in their Knowledge Journal, or submit them directly. The questions can also be used as discussion questions for a book club or other small-group activity. See the Implementation Guide for a further explanation of Volume of Reading, as well as various ways of using the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions.

For homework, students write in their Response Journal about a crisis, one that happened in the past or more recently in their lifetime. Students answer the question: “What made this event a crisis?”

If students have access to technology, they can search for information or a news report about a crisis and share this with their description of the crisis.

Students use a T-chart to record what they notice and wonder as they read the opening chapters of Fever 1793 (RL.7.1). Check for the following success criteria:

Identifies important ideas and details in the text.

Recognizes and articulates misunderstandings, questions, or ambiguities in the text.

If students struggle with noticing key details or asking questions, give them additional time to reflect and work with partners or small groups. Also consider providing prompts, such as:

What do you notice about ?

What do you wonder about ?

What words or sentences stand out?

Which descriptions or ideas seem important? Why?

Which words or sentences are confusing to you?

Time: 15 min.

Text: None

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Understand the connotation and denotation of the word crisis (L.7.5.c).

TEACHER NOTE

Vocabulary Deep Dives 20 and 32 provide direct vocabulary assessment tools and corresponding directions. To best meet students’ language needs, consider using these tools to pre-assess students at the start of this module. Do not share results with students, but use the data to inform and differentiate your vocabulary instruction. At the close of the module, reassess students using the same tools to determine their growth against the baseline data.

Explain that this lesson will help students develop a strong and precise understanding of the word crisis to ensure that their writing and discussions about the yellow fever crisis are clear and purposeful as they explore the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and texts.

Ask: “In what kinds of situations have you heard people use the word crisis?” Invite students to generate phrases that use the word crisis.

n A mid-life crisis.

n A financial crisis.

n A personal crisis.

n A medical crisis.

n The water crisis.

n A mental health crisis.

n A hair crisis.

Invite volunteers who share to describe a situation in which their phrase might be used. For example, the Great Depression was a financial crisis for the United States. A drought in California could create a water crisis.

Using students’ examples if possible, explain that people sometimes use the word crisis in an exaggerated way. As needed, explain that this usage may also be called hyperbole, which describes “exaggerated statements that are used for emphasis or humor.” Explain that students should be alert to such usages of the word crisis. Discuss several examples, such as:

“I was so embarrassed; I could have died!”

“If I get home after curfew, my dad is going to kill me!”

“I love that place; I’ve been there a billion times.”

Tell students that in this Deep Dive, in order to understand the meaning and usage of crisis, they will explore the connotations of words related to crisis and then will think about situations in which to use each of the words appropriately.

If students are also familiar with the word crisis as used in the English language arts to describe the conflict’s turning point, or the moment when the conflict must be resolved, consider having students include this literary definition in their list of literary terms or their Vocabulary Journal.

Share with students that the origin of the word crisis is from the Greek word krisis, meaning “decision.”

Ask a student to remind the class of the definitions of crisis from their Vocabulary Journal.

n A time of serious difficulty or danger.

n A period or situation of instability or upheaval, for a society or an individual.

n The moment when a disease or fever turns better or worse.

Ask: “How do these definitions of crisis relate to a point of decision?”

n They all describe a turning point, when something could get better or something could get worse, and people have to make decisions or judgments in response to those turning points and to try to steer events in a positive direction, rather than for the worse.

Display the following words and their definitions.

1. Predicament: an unpleasant or embarrassing situation.

2. Emergency: a dangerous situation that requires immediate action.

3. Disaster: a sudden event that brings severe damage or loss of life.

4. Tragedy: an event that causes great suffering and sorrow.

5. Situation: a set of circumstances or condition one finds oneself in; a sudden problem.

6. Crossroad: a point where a decision must be made.

Then, display the following sentences, each with a blank for a missing word:

At the beginning of chapter 1, Mattie oversleeps and finds herself in the of her mother having to nag her to wake up and get to work.

When the cat is about to eat a mouse on Mattie’s mother’s quilt, this could be described as a

When her father fell off the ladder and died, and Mattie’s family had to find a way to support themselves, that must have been an for them.

A great flood is a natural that can quickly and unexpectedly damage people’s houses and put their lives at risk.

The news that Polly has died must seem to be a true for Mattie.

In many novels, there comes a in which the main character must make an important decision.

Ask: “Which of the words best completes each sentence?” With student input, add the appropriate words to the display.

Ask students to generate additional example sentences for each word in which the word is used as hyperbole. For example: “The party was a total disaster; no one came, and the music was terrible.”

Write each of the words on a card, in large font, visible to the whole group. Then, have the group consider all six words and rank them in order from least to most terrible, discussing the rationale for the ordering. (You might ask six students to hold the cards, one card each, and line up in the order to enhance the visual of the ranking.)

Students list the words in order of their class ranking and then decide where to place the word crisis within that ranking. Then, students complete an Exit Ticket:

Describe why they ranked crisis in the order in which they ranked it.

Use crisis in a sentence, with context to show the connotation of the word.

33 34 2 1 3 5 6 7 15 26 11 19 30 9 17 28 13 24 21 32 8 16 27 12 23 20 31 10 18 29 14 25 22 4 35 36 37 38 WIT & WISDOM®

FOCUSING QUESTION: LESSONS 1–12

TEXT G7 M4 Lesson 2 © 2023 Great Minds PBC

Welcome (4 min.)

Launch (1 min.)

Learn (65 min.)

Organize Ideas (10 min.)

Analyze the Characters (20 min.)

Explore Causes and Responses (20 min.)

Identify Research Questions (15 min.)

Land (4 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (1 min.)

Assign Homework

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Coordinate Adjectives (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.7.1, RL.7.3

Writing

W.7.7, W.7.8, W.7.10

Speaking and Listening

SL.7.1, SL.7.2

Language L.7.2.a

Handout 2A: Character Analysis

One bean, marble, or other small object

Handout 1A: Research Overview

Research Overview Anchor Chart

Research Topics and Questions Anchor Chart

Handout 2B: Fluency Homework (optional)

Chart paper

Describe the protagonist of Fever 1793, explaining how the setting and other characters shape her identity (RL.7.3).

Respond to the Land prompt.

Examine and identify coordinate adjectives in context (L.7.2.a).

Write an Exit Ticket identifying coordinate adjectives in an example and explaining their purpose.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–12

In what context did the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 emerge?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 2

Organize: What is happening in Fever 1793?

Students delve more deeply into the story of Mattie and the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, building content knowledge about the historical characters, setting, and events. Students also begin to develop the basic skills they will need to begin a research project. Students first consider the Focusing Question and organize their ideas about the social, political, and economic conditions in Philadelphia during the beginning of the epidemic. Then, they closely consider the character of Mattie and the causes and effects of the emerging epidemic. To close the lesson, students build their knowledge of the characteristics of effective research questions.

4 MIN.