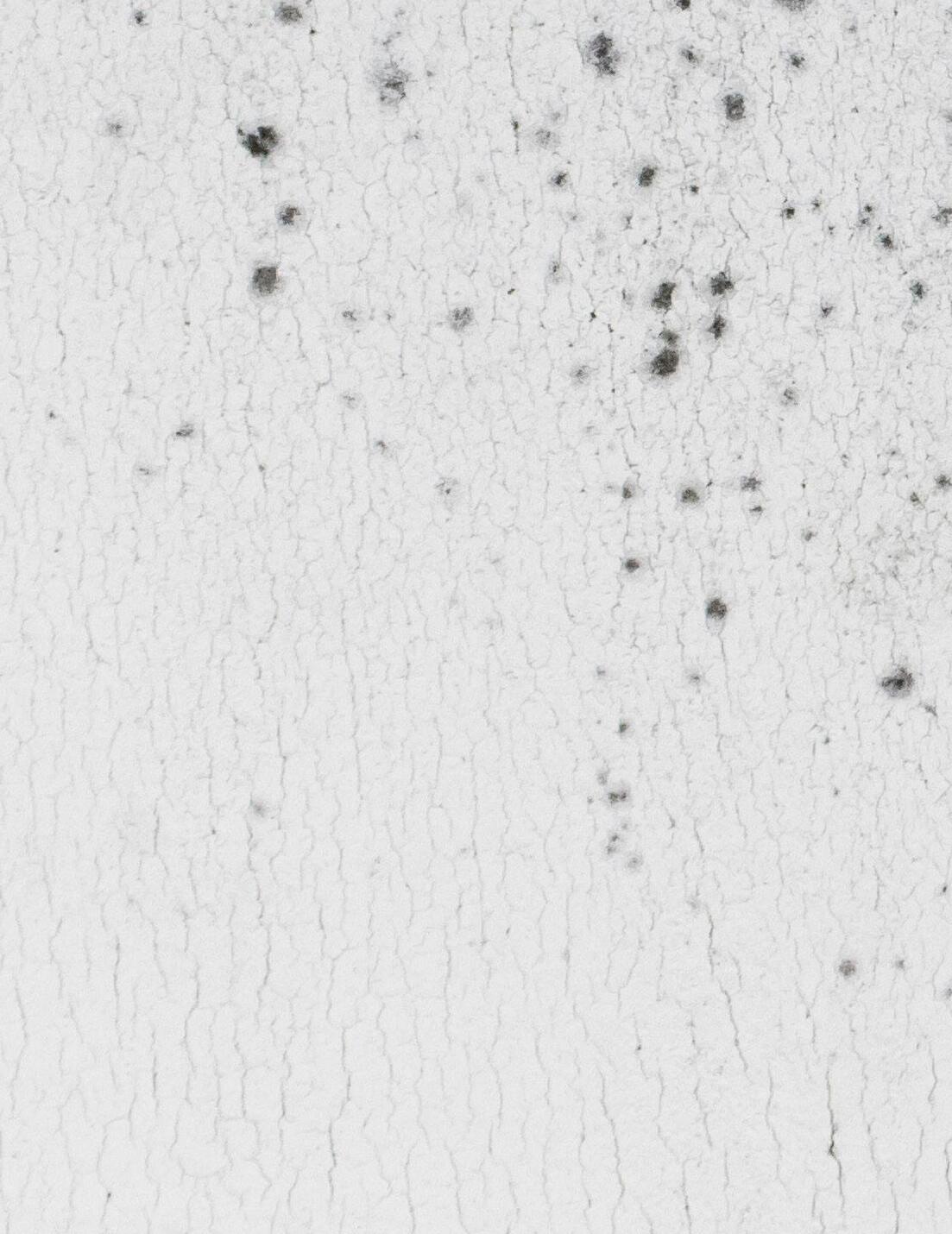

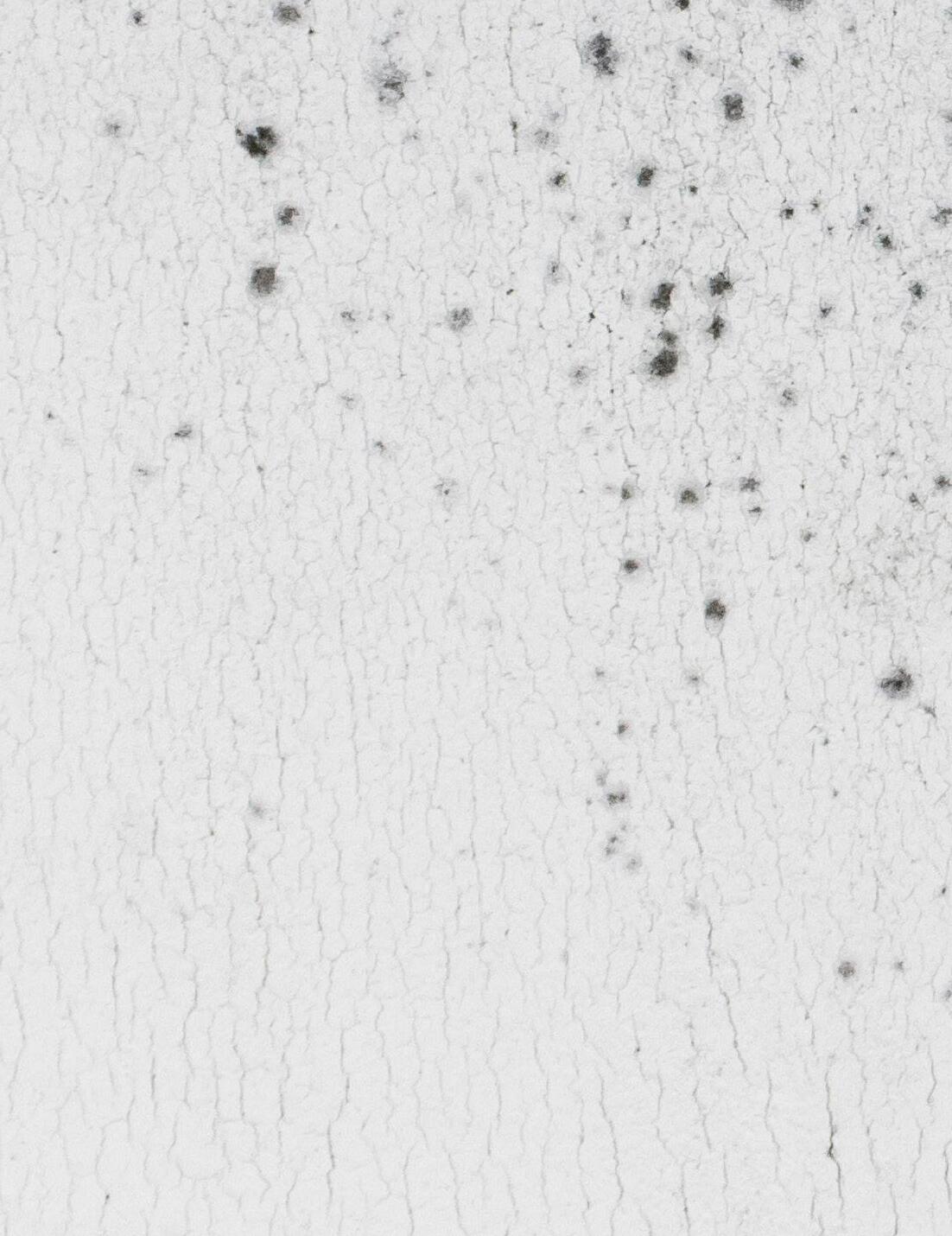

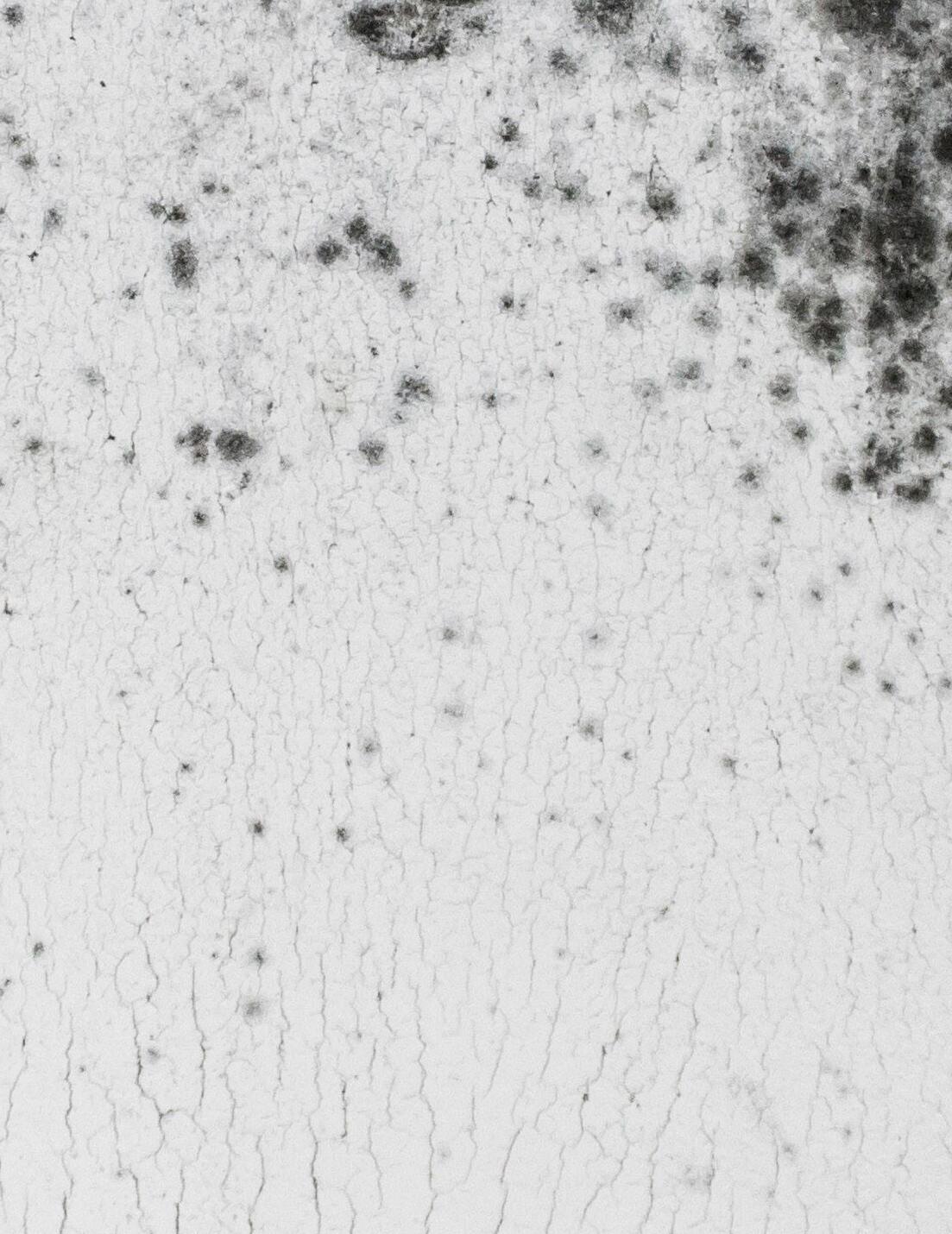

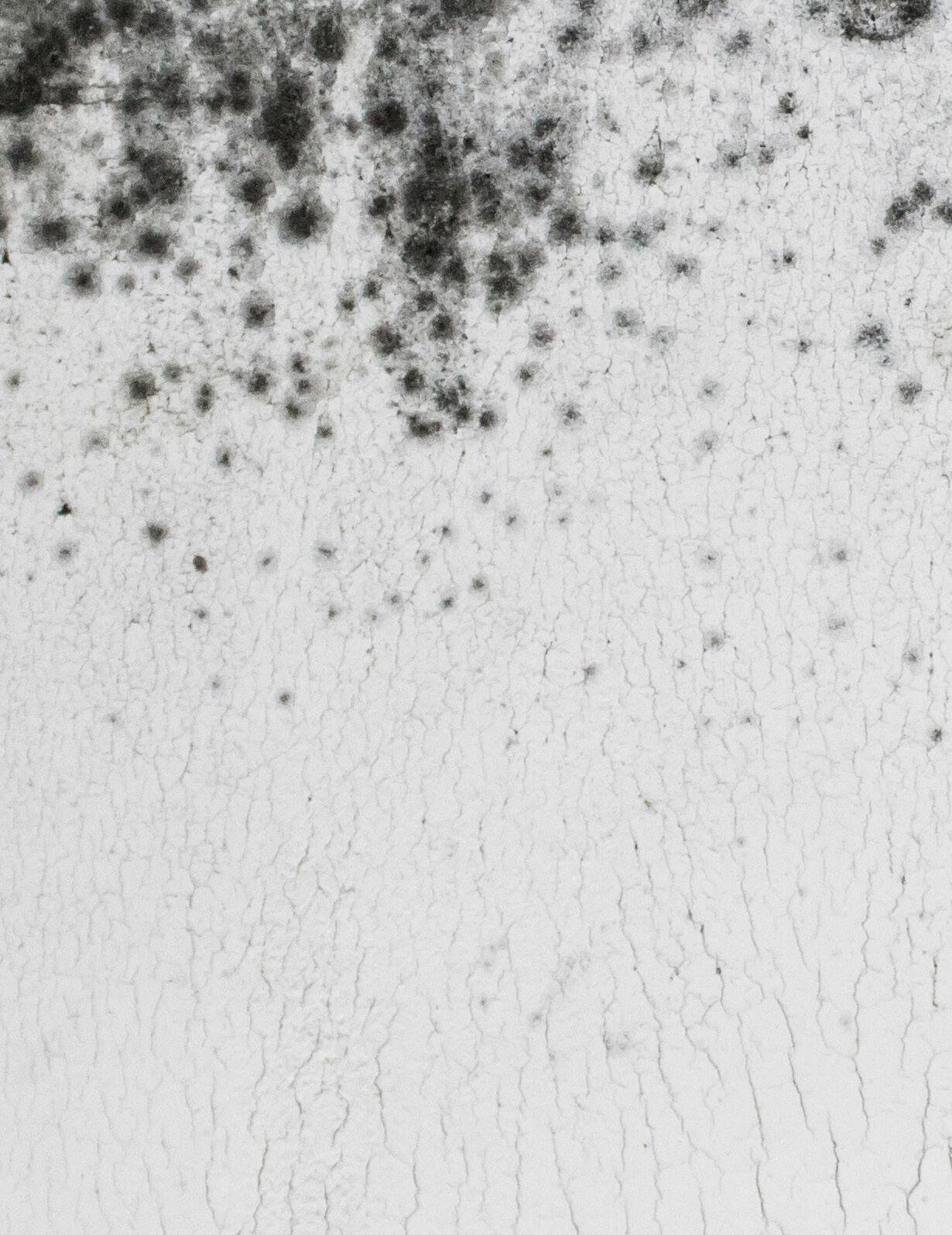

The Mold Matrix:

HOW COURTS UNTANGLE HEALTH CLAIMS, HOUSING CODES, AND LANDLORD DEFENSES

BY CHRISTOPHER L. BEARD, ESQ.

THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION reported in 2014 that approximately 7 million people died in 2012 from household and ambient air pollution; more recent WHO fact sheets cite about 6.7 million premature deaths annually. For attorneys representing landlords or tenants in mold litigation, understanding the interplay between health claims, housing codes, and legal defenses is essential. Mold litigation in Maryland sits at the intersection of property law, environmental science, and medicine, and it is vital to know the legal framework and recent developments affecting mold claims.

Tenant Remedies in Maryland District Court: Rent Escrow as a First Step Maryland tenants facing hazardous conditions like mold can seek relief through district court remedies, most notably rent escrow (Real

Property Article §§ 8-211 and 8-212).1 Tenants may file a Complaint for Rent Escrow (Form DCCV-083) to compel repairs or terminate a lease. Courts may order rent reductions, repairs via third-party administrators, or lease termination if landlords fail to address “serious and substantial” health threats. The 2024 Tenant Safety Act clarified that severe mold conditions qualify under the “serious and substantial threat” standard, even though the statute does not list mold by name. However, tenants must continue paying rent into escrow until resolution.

These remedies address habitability issues but do not preclude claims for personal injury or property damage. Tenants may still pursue separate actions under breach of lease, constructive eviction, and/or the Maryland Consumer Protection Act.2 For example, while rent escrow may secure remediation, compensation for respiratory illness requires a personal injury claim.

Courts may order rent reductions, repairs via third-party administrators, or lease termination if landlords fail to address "serious and substantial" health threats.

Legal Theories and Causes of Action

Negligence claims form the core of mold litigation. Under § 8-211(e), landlords must maintain rental properties in habitable condition.3 In Richwind Joint Venture 4 v. Brunson, 335 Md. 661 (1994), the Court held landlords responsible for known hazards.4 Brooks v. Lewin Realty III, Inc., 378 Md. 70 (2003), later held that prior notice is not required for negligence stemming from statutory violations in a case involving lead paint violations of the Baltimore City Housing Code.5

Tenants are also protected by an implied warranty of habitability, which covers health-related conditions. Persistent mold or moisture problems may constitute a breach of contract. In severe cases, tenants may claim constructive eviction, asserting that mold rendered the premises uninhabitable. To prevail, they must show substantial interference, prompt vacating, and that the interference was persistent or permanent.

The Maryland Consumer Protection Act prohibits deceptive practices like concealing mold during lease negotiations. Violations may result in actual damages or $500 (whichever is greater), with the possibility of up to treble damages for willful violations, and potential award of attorneys’ fees.6

(2013) (“Chesson II”), where the court rejected Dr. Shoemaker’s “Repetitive Exposure Protocol” as lacking general acceptance in the relevant scientific community.7

However, this evidentiary landscape changed dramatically in 2020 when the Supreme Court of Maryland decided Rochkind v. Stevenson, which overruled the Frye-Reed jurisprudence and adopted the Daubert standard. The court acknowledged its “jurisprudential drift” toward Daubert principles and formally embraced them, stating: “The time has now come to plot a new course, overruling our Frye-Reed jurisprudence and finding Daubert factors persuasive, with regard to the analysis of expert testimony.”8 This shift means that the precedential value of Chesson II is now significantly diminished.

Since Rochkind, Maryland courts now apply Daubert principles through Rule 5-702, with the Supreme Court specifying that “a trial court may apply some, all, or none of the factors depending on the particular expert testimony at issue.”9 This framework provides trial courts with greater flexibility in analyzing the reliability of expert testimony, shifting from the rigid “general acceptance” test to a more nuanced analysis.

While Chesson II excluded Dr. Shoemaker's specific "Repetitive Exposure Protocol" based largely on scientific literature from 2007 and earlier, it notably carved out an exception, stating: 'respiratory illnesses identified with mold exposure . . . are not included in the spate of symptoms before us.1

Evolution of Scientific Evidence Standards in Maryland Maryland historically followed the Frye-Reed standard for evaluating scientific evidence, which excluded certain moldrelated expert testimony. This approach was exemplified in the multi-year litigation involving Dr. Ritchie Shoemaker’s methodology. In Montgomery Mut. Ins. Co. v. Chesson, 399 Md. 314 (2007) (“Chesson I”), the Supreme Court of Maryland addressed whether expert testimony on mold exposure required a FryeReed hearing and remanded the case. After proceedings in the lower courts, the case eventually returned to the Supreme Court of Maryland in Chesson v. Montgomery Mut. Ins. Co., 434 Md. 346

3 Md. Code Ann., Real Property Art., § 8-211(e).

4 Richwind Joint Venture 4 v. Brunson, 335 Md. 661 (1994).

5 Brooks v. Lewin Realty III, Inc., 378 Md. 70 (2003).

6 Md. Code Ann., Com. Law § 13-301, et seq.

8 Rochkind v. Stevenson, 471 Md. 1, 28 (2020).

9 Id. at 37.

10 Id. at n16.

11 Chesson II, 434 Md., 351, n3.

Mold-Related Expert Testimony After Rochkind Importantly, the Rochkind court explicitly stated that just because “a court has accepted testimony before, it shall not be accepted again, ‘rejecting the type of ‘consistency’ that would categorically exclude mold-related expert testimony based on older precedent.”10 This change is particularly significant for mold litigation. While Chesson II excluded Dr. Shoemaker’s specific “Repetitive Exposure Protocol” based largely on scientific literature from 2007 and earlier, it notably carved out an exception, stating: ‘respiratory illnesses identified with mold exposure . . . are not included in the spate of symptoms before us.’11

7 Montgomery Mut. Ins. Co. v. Chesson, 399 Md. 314 (2007); Chesson v. Montgomery Mut. Ins. Co., 434 Md. 346 (2013).

The Appellate Court of Maryland in Chesson II had previously clarified that “it is well settled that exposure to water-damaged buildings can [affect] respiratory issues.”12

It is also worth noting that Chesson II was a workers’ compensation case where, significantly, Dr. Shoemaker admitted on cross-examination that he performed no mold testing of the buildings to determine the level of mold exposure.13 The court expressly stated that looking at the level of mold exposure was “essential.”14 This presents a critical factual distinction from most residential mold cases, where environmental testing is typically conducted.

ailments, allergic reactions, and asthmatic symptoms—all of which may present as either acute or chronic health conditions. Recent technological advances have expanded the toolbox available to plaintiffs. Utilizing DNA analysis to detect mold species in dust samples and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques can offer precise identification of mold species. These tools, while often reflective of past exposure, may support a current diagnosis when interpreted by a certified inspector.

Importantly, Maryland law does not require plaintiffs to meet an overly stringent scientific standard to prove causation in civil cases.

Under the current Daubert/Rochkind standard, plaintiffs’ experts in mold litigation commonly rely on a range of methodologies, including:

• Environmental reviews and mold sampling;

• Clinical history linking exposure to symptoms;

• Blood tests (e.g., IgG/IgE antibodies, HLA genetic markers, and inflammatory indicators);

• Observations of symptom resolution after relocation;

• Peer-reviewed literature and diagnostic criteria from professional bodies.

This multifaceted approach aligns with Maryland courts’ evolving application of Rule 5-702, particularly following the adoption of Daubert principles in Rochkind v. Stevenson, which allows trial courts greater flexibility in evaluating expert testimony methodologies. While Chesson excluded one novel protocol, it did not categorically bar mold causation testimony grounded in recognized science.

Emerging Scientific Methods in Mold Litigation

Following Chesson, Dr. Shoemaker refined his work and developed the “Shoemaker Protocol” for diagnosing chronic inflammatory response syndrome (CIRS), incorporating genetic susceptibility research. Although not yet embraced by Maryland courts, his evolving methodology may gain future judicial consideration, particularly as scientific consensus grows.

In the meantime, according to both the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), evidence clearly shows that mold exposure can cause respiratory

Similarly, urine mycotoxin testing (e.g., for ochratoxins or trichothecenes) is gaining recognition, despite limited use in standard clinical settings. Although still emerging, such tests are increasingly cited to support mold-related claims in litigation.

Environmental–Biologic Match

A particularly compelling causation tool is the finding of the same mycotoxin both in the building environment and in the occupant’s urine. The environmental sample shows the toxin is present at the property; the biologic sample shows it entered the body. While not itself proof of disease, this correspondence strengthens the causal link between exposure and injury.15

Importantly, Maryland law does not require plaintiffs to meet an overly stringent scientific standard to prove causation in civil cases. Instead, they may satisfy the preponderance of evidence burden through a combination of medical testimony, environmental assessments, and evidence of housing code violations. Advanced testing can certainly bolster a claim, but it is not necessary to meet the legal standard.

This practical approach was the topic at the Safe Housing Collaborative Workshop: Mold Law 101, held last October in Austin, Texas. The argument was made that the most effective cases often feature two key players: a certified mold inspector and the client’s primary care physician (PCP). Practitioners should ensure their clients provide certified mold inspection results to their PCPs, as this documentation can significantly aid physicians in their differential diagnosis process, allowing them to more confidently connect respiratory symptoms to mold exposure when considering the patient’s history, symptoms, and environmental factors.

This accessible combination of certified mold inspection documentation and informed medical assessment remains

12 Montgomery Mutual Insurance Co. v. Chesson, 206 Md.App., 569, n10 (2012), aff’d, 434 Md. 346 (2013).

13 Id. at 366.

14 Id. at 374-78.

15 Straus, D.C.,

central to establishing causation in most residential mold cases, even without cutting-edge science.

The practical effect of Rochkind in mold cases cannot be overstated. Courts now task themselves with analyzing the reliability of the particular testimony presented rather than categorically excluding entire methodologies based on precedent. This means that even if an expert employs methods similar to those previously rejected under Frye-Reed, their testimony may now be admissible if the court finds it reliable under the more flexible Daubert analysis. Practitioners should be prepared to argue the reliability of their expert’s specific methodologies rather than simply citing or distinguishing from Chesson

Update: Maryland’s New Tenant Mold Protection Law (2025) Maryland has passed a major new law—the Tenant Mold Protection Act (SB 856)—that went into effect on July 1, 2025.16 Landlords must provide a state- or EPA-approved mold pamphlet at lease signing and obtain the tenant’s written acknowledgment; thereafter, the pamphlet is provided on request rather than automatically at renewal.

Once a tenant, occupant, or code official gives written notice of suspected mold, the landlord has 15 days to conduct an assessment. If mold is found, remediation must be completed within 45 days after the assessment—or within a reasonable time if 45 days is not feasible—with clear communication to occupants and coordinated access throughout.

Baseline duties include promptly fixing leaks, maintaining ventilation and humidity control, and complying with local housing codes. Tenants should send dated written notice and keep photos or video; landlords should calendar the 15- and 45-day deadlines, use qualified assessors and remediators, address the moisture source, and keep thorough records (acknowledgments, inspection reports, scopes, invoices, completion confirmations). Those records will drive outcomes in rent-escrow, habitability, and consumer claims.

Housing Codes as Enforcement Tools

Maryland has not yet adopted statewide mold standards, but the Tenant Mold Protection Act (SB 856) now imposes a 15/45-day process for assessment and remediation and directs MDE to issue uniform regulations by June 1, 2027.

Until those regulations take effect, local housing codes remain the practical enforcement tools: For example, Baltimore County

16 2024 Md. Laws, ch. 539 (SB 856) (Tenant Mold Protection Act), eff. July 1, 2025; MDE regs due June 1, 2027).

17 Poffenberger v. Risser, 290 Md. 631 (1981).

18 Georgia-Pacific Corp. v. Benjamin, 394 Md. 59, 89 (2006).

19 Georgia-Pacific, 394 Md. at 90.

Code § 35-5-209(a) and Baltimore City Building, Fire, and Related Codes (2024) § 307 require sanitary conditions and abatement of health hazards.

Even without mold-specific language, inspectors’ reports noting “biological growth,” leaks, dampness, or inadequate ventilation can substantiate violations and support remediation orders, rentescrow, and habitability claims. Inspectors need not be moldcertified; their documented observations of moisture sources and ventilation defects are often sufficient.

Landlord Defenses and Tenant Responsibilities

Common landlord defenses include contributory negligence and assumption of risk. Landlords may argue that tenants failed to report leaks or maintain proper ventilation. Tenants often counter with documented repair requests, communications, or inspection reports.

Statute-of-limitations defenses also arise. Under Maryland’s discovery rule, a two-pronged test determines when a claim accrues. The first prong assesses whether a plaintiff has actual notice − either express or implied − sufficient to prompt a reasonable person to investigate the existence of an injury.17

The second prong requires that a diligent inquiry would reveal the causal connection between the injury and wrongdoing, fixing the accrual date when both injury and cause would have been known by sufficient investigation.18

This is a fact-specific inquiry that must be applied on a caseby-case basis; whether limitations apply ultimately depends on particular circumstances.19

Conclusion

Mold litigation in Maryland continues to evolve under Rochkind, the Chesson litigation, and new statutory duties under SB 856. The combined use of environmental sampling and biologic testing is emerging as a particularly compelling way to demonstrate exposure causation. Practitioners must stay abreast of changes to effectively advocate for clients amid shifting evidentiary standards and growing regulatory attention. As courts and lawmakers clarify responsibilities and remedies, the legal framework around mold exposure continues to mature.

Christopher L. Beard, Esq., is an Annapolis attorney focusing on premises liability, negligence law, and mold exposure litigation.