Hon. Louis H. Schiff and Robert M. Jarvis, eds.

REVIEWED BY THE HON. DOUG NAZARIAN

The National Baseball Hall of Fame is a hallowed and exclusive place. Of the tens of thousands who have played, managed, coached, owned, umpired, broadcast, or otherwise contributed to America’s Pastime,1 only 351 have been elected to membership.2 And it’s not just about on-field performance. Both the Baseball Writers’ Association of America,3 which elects former players, or the Eras Committee,4 which elects some former players and all of the non-players, consider “integrity, sportsmanship, character and contributions” alongside the candidate’s record—a character and fitness component that mirrors, in a way, the requirements for admission to the Bar.5

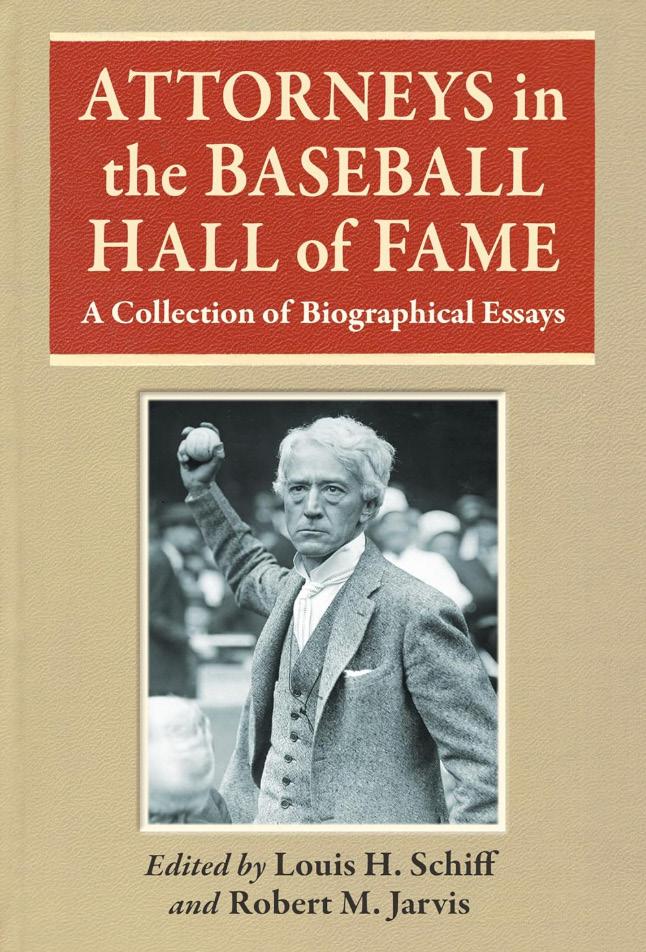

So it’s extremely rare for a person to have a baseball career worthy of the Hall and qualify as a lawyer. Indeed, there are only 11 such people, and the aptly titled Attorneys in the Baseball Hall of Fame anthology, edited by retired Florida Judge Louis Schiff and Nova Southeastern Law Professor Robert Jarvis, offers insightful biographical essays about each.6 Their baseball contributions took many forms, and on balance, those involved in leadership and ownership roles garnered more controversy. Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was the first Commissioner

of Baseball, elected by the owners in 1920. He was meant to clean up baseball after the Chicago Black Sox scandal of 1919, but faced his own ethical challenges and refused to resign his seat on the federal bench for nearly two years after assuming the Commissioner’s role. Happy Chandler succeeded Judge Landis as Commissioner after serving as lieutenant governor and governor of Kentucky and United States Senator, then was elected again as governor before running for President in 1960. Bowie Kuhn, a “terrible athlete,” was a partner at a Wall Street firm that represented baseball clubs, then elected as the fifth Commissioner at age 42. Larry McPhail was also a lawyer first,

1 Baseball Reference lists 23,600 major leaguer players as of September 11, 2025. See Baseball Reference, https://www.baseballreference.com/ (last visited September 11, 2025.

2 “The Hall of Fame is comprised of 351 elected members. Included are 278 former major league players, as well as 40 executives/ pioneers, 23 managers and 10 umpires.” See National Baseball Hall of Fame website, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame (last visited August 31, 2025)

3 Voting “shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played.” Rule 5, Baseball Hall of Fame Election Rules, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/election-rules/ bbwaa-rules (last visited August 31, 2025).

4 Voting “shall be based upon the individual’s record, ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character and contribution to the game.” Baseball Hall of Fame Election Rules, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/election-rules/era-committees (last visited August 31, 2025).

5 This explains why players responsible for some of the greatest on-field accomplishments haven’t been elected. In addition, “[a]ny player on Baseball’s ineligible list shall not be an eligible candidate,” a list that until recently included Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson. See also Rule 3.E, Baseball Hall of Fame Election Rules, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/election-rules/bbwaa-rules (last visited August 31, 2025).

6 The individual essays are authored by an impressive array of law professors and law librarians in addition to Judge Schiff and Professor Jarvis.

It’s extremely rare for a person to have a baseball career worthy of the Hall and qualify as a lawyer.

then a businessperson, then an executive with three different teams (he retired to a horse farm in Harford County and owned the Laurel Park racetrack before an incident that led to his removal). Walter O’Malley was a lawyer who represented the Brooklyn Dodgers, then bought them, and then, much to my father’s chagrin, moved them to Los Angeles in 1957. Branch Rickey forfeited his eligibility to play college baseball by playing on a semi-pro team, but coached the baseball team at the University of Michigan while in law school and in private practice before embarking on a four-decade career as a transformational baseball executive. Perhaps not surprisingly, these men overlapped and intersected: Rickey recommended McPhail for the Reds’ job, then both, and then-Commissioner Chandler and O’Malley all played roles (not all supportive) in the integration of baseball in 1947. Not all were beloved, then or after, but their legal training and experience influenced their contributions.

Most recently, Tony LaRussa went to law school toward the end of his 16-season (mostly minor league) playing career, passed the Florida bar exam, was affiliated with a Sarasota law firm, and went into the Hall as the third-winningest manager of all time.

These historical sketches bring to life the professional versatility of our law degrees. Even so, the combination of a Hall-worthy on-field career and a law degree seems even more unlikely now than it was in the past (and it was pretty unlikely then). Top baseball players frequently begin their careers directly from high school or before graduating from college, and anyone good enough after college to play well in the major leagues will be long removed from their studies— and, in today’s game, will have made plenty of money. Major leaguers no longer need off-season jobs and devote the winter to fitness and improvement rather than schooling.

The combination of a Hall-worthy on-field career and a law degree seems even more unlikely now than it was in the past (and it was pretty unlikely then).

Others had primarily on-field roles, and history has tended to view them more positively. Hughie Jennings played 12 seasons with four different teams, coached in the minor leagues while attending law school at Cornell (he never graduated, but passed the Maryland bar exam), then managed the Detroit Tigers and New York Giants for 15 years and practiced law in the off-season. Gentleman Jim O’Rourke played 13 years, completed Yale Law School (without a college degree) while playing for another eight, then settled into private practice and civic life in Connecticut. Miller Huggins was a solid majorleague player who became player-manager of the Cincinnati Reds and managed the first New York Yankees’ dynasty, including the “Murderers’ Row” team of 1927; he entered law school at the University of Cincinnati without a college degree and played on the baseball team, passed the bar exam, but never practiced. John Montgomery Ward was a Hallworthy pitcher who earned law and philosophy degrees from Columbia, wrote extensively for magazines and newspapers, founded the upstart Players League in 1890, then played and managed five more seasons before practicing law in New York City (and serving briefly as part-owner and president of the Boston Braves and Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the Federal League).

And almost nobody goes to law school anymore without a college degree or qualifies for the bar exam without a Juris Doctor. There undoubtedly are future Hall of Fame lawyers among the executive ranks—Theo Epstein comes first to mind—but tomorrow’s Hughie Jennings, Miller Huggins, or Gentleman Jim O’Rourkes is hard to picture. I hope I’m wrong.

The Honorable Douglas R. M. Nazarian has served on the Appellate Court of Maryland since January 2013. He joined the Court after five years at the Maryland Public Service Commission and 15 years as a litigator in law firms in Washington and Baltimore. He is a graduate of Yale College and Duke Law School and clerked for Judge James B. Loken of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. He serves as a Senior Adjunct Professor and Member of the Board of Visitors at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law.