8 The Power of Poetry

8 | Module 1

8 | Module 1

What are the intersections between stories and poetry?

Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Eureka Math2® , Wit & Wisdom® , Arts & Letters™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2025 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder.

ISBN 979-8-88811-319-6

Fluency Practice | The Crossover, passage 3

Module 1 | Write complete sentences about what you learned. Whole Page Caption: A two-column chart with headings labeled World Knowledge and English Knowledge.

World Knowledge English Knowledge

by Julia Alvarez

Ciudad Trujillo, New York City, 1960

The night we fled the country, Papi, you told me we were going to the beach, hurried me to get dressed along with the others, while posted at a window, you looked out

at a curfew-darkened Ciudad Trujillo, speaking in worried whispers to your brothers, which car to take, who’d be willing to drive it, what explanation to give should we be discovered …

On the way to the beach, you added, eyeing me. The uncles fell in, chuckling phony chuckles, What a good time she’ll have learning to swim!

Back in my sisters’ room Mami was packing

a hurried bag, allowing one toy apiece, her red eyes belying her explanation: a week at the beach so Papi can get some rest. She dressed us in our best dresses, party shoes.

Something was off, I knew, but I was young and didn’t think adult things could go wrong. So as we quietly filed out of the house we wouldn’t see again for another decade,

I let myself lie back in the deep waters, my arms out like Jesus’ on His cross, and instead of sinking down as I’d always done, magically, that night, I could stay up,

floating out, past the driveway, past the gates, in the black Ford, Papi grim at the wheel, winding through back roads, stroke by difficult stroke, out on the highway, heading toward the coast.

Past the checkpoint, we raced towards the airport, my sisters crying when we turned before the family beach house, Mami consoling, there was a better surprise in store for us!

She couldn’t tell, though, until … until we were there. But I had already swum ahead and guessed some loss much larger than I understood, more danger than the deep end of the pool.

At the dark, deserted airport we waited. All night in a fitful sleep, I swam.

At dawn the plane arrived, and as we boarded, Papi, you turned, your eyes scanned the horizon

as if you were trying to sight a distant swimmer, your hand frantically waving her back in, for you knew as we stepped inside the cabin that a part of both of us had been set adrift.

Weeks later, wandering our new city, hand in hand, you tried to explain the wonders: escalators as moving belts; elevators: pulleys and ropes; blond hair and blue eyes: a genetic code.

We stopped before a summery display window at Macy’s, The World’s Largest Department Store, to admire a family outfitted for the beach: the handsome father, slim and sure of himself,

so unlike you, Papi, with your thick mustache, your three-piece suit, your fedora hat, your accent. And by his side a girl who looked like Heidi in my storybook waded in colored plastic.

We stood awhile, marveling at America, both of us trying hard to feel luckier than we felt, both of us pointing out the beach pails, the shovels, the sandcastles

no wave would ever topple, the red and blue boats. And when we backed away, we saw our reflections superimposed, big-eyed, dressed too formally with all due respect as visitors to this country.

Or like, Papi, two swimmers looking down at the quiet surface of our island waters, seeing their faces right before plunging in, eager, afraid, not yet sure of the outcome.

“Exile” | Use the checklist and chart to notice and wonder about the text.

A checklist with the heading labeled Literary. Underneath, a two-column chart with headings labeled Notice and Wonder.

□ skim the title page and copyright page to gather information about the publication.

□ skim the first few lines and last few lines of the text to see if you can determine the main ideas.

□ Identify genre features (e.g., act numbers, line numbers, stanzas, journal entries).

□ skim the entire text.

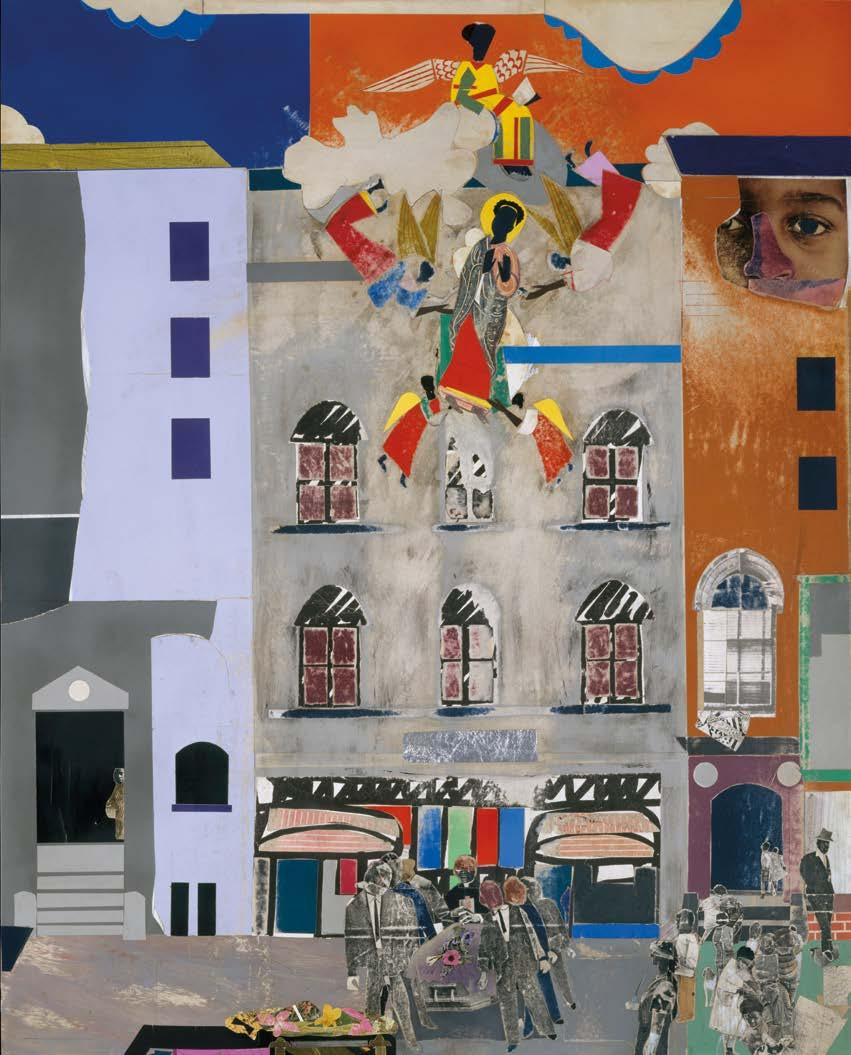

Work of Art | Write what you notice and wonder about the work of art. A two-column chart with headings labeled Notice and Wonder. Notice Wonder

by Robert R. Álvarez Jr.

The Dominican population in the United States, like Puerto Ricans and Mexicans, began arriving at the turn of the twentieth century. Unlike Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic experienced internal domination during the “Trujillato,” the reign of dictator Molina Trujillo from 1930 to 1960, that constricted the migrant flow from the Republic. After the death of Trujillo in 1961, a surge of Dominicans began leaving for the United States. Throughout this period and into the present, the family and its constituent institutions have been a major factor for Dominicans in both initiating migration to the United States and in the initial settlement and adaptation to the United States. Through the institution of the family, Dominicans have maintained a

continuous chain of movement between the Republic and the mainland United States. Understanding the basic causes of the migration helps comprehend the development of the Dominican family as an institution responding to socioeconomic circumstances in both the United States and the Republic.

“Exile” | Complete each column of the chart.

A three-column chart with headings labeled Swimming-Related Language, What the Language Compares, and What Meaning the Comparison Creates.

Swimming-Related Language What the Language Compares What Meaning the Comparison Creates

• “I let myself lie back in the deep waters” (line 21), “instead of sinking down … I could stay up” (lines 23–24)

floating in water to leaving home The speaker feels relaxed about leaving Ciudad Trujillo and surrenders to being carried to an unknown destination.

Module Texts | Complete each column of the organizer.

A three-column chart with headings labeled Element, Definition, and Examples.

Element

Definition

setting the time, place, and conditions in which the action of a book, movie, etc. takes place

Examples

by Sean Glatch

riters who want to set their stories in verse may be interested in the narrative poem. One of the oldest literary art forms in the history of written language, narrative poetry puts plot to poesy, combining the art of storytelling with the techniques of poetry writing. … The narrative poem is a form of poetry that is used to tell a story. The poet combines elements of storytelling— like plot, setting, and characters—with elements of poetry, such as form, meter, rhyme, and poetic devices.

Narrative Poem Definition: a form of literature that combines the elements of poetry with the elements of storytelling

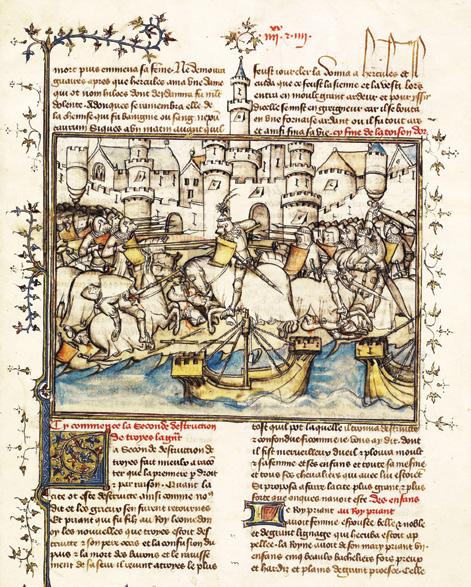

The narrative poem is the oldest form of poetry, and one of the oldest forms of literature. Epics like The Iliad and The Odyssey, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and The Mahabharata are ancient and long narrative poem examples. Long before the written word and the invention of mass publishing, storytellers told their stories in verse, and have done so since (at least) 2100 B.C.

There are several reasons for this, including the challenge of writing in verse and the entertainment value of listening to stories that use meter and rhyme. But the main reason is that those elements served as guideposts for the storyteller. By following the patterns of rhyme and syllabic stress, the storyteller could keep up with which line comes next, so these devices served both mnemonic and entertainment purposes. Today, the narrative poem has evolved to accommodate the storytelling needs of poets, without (necessarily) the constraints of meter and rhyme scheme.

What are the differences between narrative poetry versus lyric poetry? Readers sometimes conflate the two terms, but they are markedly different in intent.

The difference between narrative poetry versus lyric poetry is the poem’s sense of time. In a narrative poem, the measurable flow of time is central to the poem itself. We need time to chart the poem’s story: its order of events, the actions and reactions of the characters, the A causes B causes C. …

In a lyric poem, the poem’s events are suspended in time. While the poem may dwell on time or discuss moments in the past, the poem’s intent is to lift events, emotions, and images from the time they happened, imposing them as something eternal and immutable (though surely interpretable) on the page.

Across several millennia of literature, there are a few different types of narrative poetry that you can try your hand in. While each type varies in style, form, and intent, they all share the same goal of telling great stories through the power of verse.

Among contemporary narrative poems, the novel in verse rules. A verse novel is exactly what it sounds like: a novel-length story told through lines of poetry, not prose. …

Because a novel in verse is largely experimental, there are no solid rules for how to write one. However, many verse novels tend to have first person narrators, short chapters, and non-linear storytelling. Additionally, verse novels emphasize internal dialogue and emotions, sometimes employing stream-of-consciousness techniques. …

The characteristics of narrative poetry include:

• An emphasis on storytelling: Narrative poems convey plot, setting, characters, and other key elements of stories.

• Experimental language: The unexpected, experimental word choice in narrative poems should surprise, delight, awe, transfix, move, inspire, and/or captivate the reader.

• Non-linear story structure: Narrative poems rarely follow a single narrative thread or linear structure. These poems might jump forward or backwards in time, start in the middle, or trace completely disparate events before stitching them into one unified story.

• Contemporaneous forms: You may have noticed that no two types of narrative poetry are written in the same way. Each has its own form, and that form is dependent on the poem’s story, the year it was written, and the region it was written in. Contemporary narrative poems tend to be free verse.

• Mythological elements: Most of the narrative poetry written in antiquity dwelled on mythology. Even some

contemporary examples, like Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red, are retellings of Greek myths, though modern day verse novels aren’t uniformly interested in myth.

• Internal characterization: Many narrative poems focus on the internal. The poetic language of the form allows writers to capture thoughts, feelings, and internal challenges that prose might not properly capture. Modern novels in verse are usually told from the first-person or from a very limited third-person point of view.

“What Is a Narrative Poem?” | Use the checklist and chart to notice and wonder about the text.

A checklist with the heading labeled Informational. Below, a two-column chart with headings labeled Notice and Wonder.

□ skim the title page and copyright page to gather information about the publication.

□ skim for text features (maps, diagrams, captions, subtitles, section headings, bold or italic words).

□ skim the first few paragraphs and last few paragraphs of the text to see if you can determine the topic.

Notice Wonder

The Crossover | Use the checklist and chart to notice and wonder about the text.

□ examine the front and back covers.

□ skim the title page and copyright page to gather information about the publication.

□ skim the publisher’s description of the book to see whether you can determine topics or themes it might cover.

□ Identify genre features (e.g., act numbers, line numbers, stanzas, journal entries).

A checklist with heading labeled Literary. Below is a two-column chart with headings labeled Notice and Wonder. Notice Wonder

assist (n.)

The Crossover | Parts of Speech Key: (n.) noun, (v.) verb

an action (such as passing a ball or puck) that helps a teammate to score

crossover (n.)

1. a simple basketball move in which a player dribbles the ball quickly from one hand to the other

2. a change from one style or type of activity to another

double-team (v.)

to block or guard (an opponent) with two players at one time

dribble (v.)

to move a ball forward by tapping or bouncing it

dunk (v.)

to jump high in the air and push (the ball) down through the basket

fast break (n.)

a quick movement toward the net in an attempt to score before the opposing players can reach their defensive positions

free throw (n.)

a basketball shot worth one point that must be made from behind a special line and that is given because of a foul by an opponent

foul line (n.)

a line from which a player shoots free throws lay-up (n.)

a shot made from a position that is very close to the basket

rebound (n.)

the act of catching the ball after a shot has missed going in the basket

shoot (v.)

to attempt to score a basket (This sense is usually used with sports or games that involve shooting a ball.)

travel (v.)

to take more steps while holding a basketball than the rules allow

The Crossover | In each box, write phrases or sentences to summarize the narrative elements of the text.

Boxes with headings labeled Characters, Setting, Conflict, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Resolution. The Characters, Setting, and Conflict boxes are stacked vertically within a surrounding box labeled Exposition. A flat line under the Exposition box slants upward under the Rising Action box. The line comes to a point next to the Climax box. The line slants downward next to the Falling Action box. The line is flat again under the Resolution box. Exposition

Characters

Setting

Conflict Rising Action

adapted from pages 52–53 of The Crossover by

Kwame Alexander

R1: I walk into the lunchroom with JB.

ALL: Heads turn.

R1: I’m not bald like JB, but my hair’s close enough so that people sprinting past us

ALL: do double-takes.

R1: Finally, after we sit at our table, the questions come:

ALL: Why’d you cut your hair, Filthy? How can we tell who’s who?

R2: JB answers, I’m the cool one who makes free throws,

R1: and I holler, I’M THE ONE WHO CAN DUNK.

ALL: We both get laughs.

Crossover

adapted from page 29 of The Crossover

by Kwame Alexander

[kraws-oh-ver] noun

A simple basketball move in which a player dribbles the ball quickly from one hand to the other. As in when done right, a crossover can break an opponent’s ankles. As in Deron Williams’s crossover is nice, but Allen Iverson’s crossover was so deadly, he could’ve set up his own podiatry practice. As in Dad taught me how to give a soft cross first to see if your opponent falls for it, then hit ’em with the hard crossover.

The Crossover | Complete each column of the organizer. Provide specific examples from the text to support your responses.

A three-column chart with headings labeled Title of Poem (page number), Description of Form, and How Form Impacts the Poem’s Meaning.

Title of Poem (page number)

“cross·o·ver” (page 29)

Description of Form How Form Impacts the Poem’s Meaning

• dictionary format with pronunciation and part of speech

• italicized font

• different line lengths

• repetition of “as in”

The Crossover | Write relevant information in each column.

A three-column chart with headings labeled Details, Emerging Theme, and Supporting Evidence. Details Emerging Theme Supporting Evidence

repeated mention of Josh’s locks identity

“These locks on my head, / I designed it.” (Alexander 33)

con | Write words with the root con.

A circle in the center for the root con. Lines branch off the circle in different directions. The lines connect the central circle to five other circles.

Inferred definition:

con together or with

The Crossover | Add events that contribute to Josh’s reaction.

A representation of the passage of time as a line. Boxes for writing with headings labeled Events and Details.

The Crossover | Use the following list to help you determine the mood in the poems “Second-Person” and “Third Wheel.” amused anxious bleak depressed discontent energetic foreboding frustrated gloomy indifferent irritated lonely mellow optimistic peaceful rejected relaxed shocked silly subdued surprised tense uncomfortable upbeat

The Crossover | Use phrases or sentences to describe a conflict or event and Mom’s influence on pages 137–172. Add the corresponding text evidence. A three-column chart with headings labeled Conflict or Event, Mom’s Influence, and Text Evidence.

Poem

“Suspension” pages 138–141

“Storm” pages 151–152

Conflict or Event Mom’s Influence Text Evidence

Josh throws the basketball at JB’s face.

Mom suspends Josh from the team for breaking JB’s nose.

“You’re suspended … / From the team.” (141)

“I run into Dad’s room” pages 165–167

1

by CARMEN MOLINA ACOSTA

rowing up, there were a lot of pieces of Julia Alvarez that felt like they didn’t fit together the way they were supposed to. Today, Alvarez is an award-winning author, most known for her first novel, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents. But as a young girl, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic and an aspiring writer, she said there were versions of herself that she wasn’t always allowed to share, because they weren’t acceptable to her family and surrounding community.

2

For Code Switch’s summer book series on freedom, I spoke to Alvarez about her 2004 poetry collection, The Woman I Kept to Myself, in which she explores all her different selves—the little girl who recites poetry to herself every night, the sister who fears her family’s reproach, the seasoned professor who prides herself on helping her students—and how she uncovered them with writing. In a way,

it’s a very Code Switch-y collection—an acknowledgement that you’re never all of yourself all of the time, and that so many of us exist perpetually in gray areas. We talked about the selves we don’t share with the world—or that the world doesn’t let us share with them—and how we can find freedom in giving those selves a voice. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You’re most famous for your novels—especially How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents—but you started out as a poet. Where did the inspiration for The Woman I Kept to Myself, your third poetry collection, come from?

Every time I want to touch bottom in myself, I return to poetry. I feel like poems are where I am meeting up against the silence. I’m trying to understand and give word to feelings that are yet to be brought into language.

I wanted to touch on those moments where there’s a little enlightenment or a little awareness. It doesn’t have to be about something big or important, but those little things you keep to yourself— selves that you keep to yourself—and give us language to understand them. Did you find freedom in speaking to those selves, in the process of writing those poems?

For me, maybe because I am a writer, naming is a kind of liberation. I always think of that line from Dylan Thomas: “I sang in my chains like the sea.” There’s something about singing that, even if you’re feeling chained, even if you’re feeling oppressed, the song in itself is a liberation. And because there is a listener, there is community, and there’s a sense that you are connecting with a reader at those deepest levels of the self, and

therefore maybe liberating them. I love the Toni Morrison quote, “The function of freedom is to free someone else.” And I feel that when you give word to these secret selves, hidden selves, outlier and outlaw selves, that you kind of liberate. You pass on the courage to someone else.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the poem that you get the title

The Woman I Kept to Myself from.

It’s called “By Accident,” and in it, you set up this story of how you almost feel like you became the person that you became by chance. You write:

“... nothing prepared the way, not a dramatic, wayward aunt, or moody mother who read Middlemarch, or godmother who whispered, ‘You can be whatever you want!’ and by doing so performed the god-like function of breathing grit into me.”

How did you become the woman that you are, then, and who specifically is the woman you kept to yourself?

To set the scene of the poem, it’s something that really did occur: At night, my sisters and I would be in the room with the lights off, and I would start reciting poems that I had memorized. And Mami, with her chancletas, would come down the hall, turn on the lights, and she would say, “Why can’t you be considerate? Keep it to yourself.” And [the speaker] says that this self that she kept to herself is what drove her to poetry. All those selves that were not acceptable, or that people found irritating or didn’t understand, they went on paper. So it’s not a specific one woman—in fact, it’s all the women that you keep to yourself, which form the woman you get to yourself. You write several poems about how you were defying expectations by taking to writing and taking to writing in English, specifically, as a woman and as an immigrant. Where did you find that freedom to write yourself into existence?

poems are those moments where the speaker realizes that things are not making sense to her. She doesn’t fit in. So out of necessity, you’re needing to make yourself up, because the self that’s getting put on you doesn’t fit, and you will start to wither and die if you just cramped yourself into that definition.

Growing up in a very patriarchal, machista culture in the 50s in the Dominican Republic in a dictatorship, there was a lot of repression. And then when we came to [the United States], all of a sudden, everything had been stripped away that had made meaning for me. So instead of going out to community, I was forced into creating an interior self and a life in there that could feed me and nurture me. That’s where I became a reader, and I [started to] want to be a writer. But back when I was getting started, people like me weren’t in books. So it was definitely a writing that I was doing for myself out of a kind of necessity. I discovered in doing that, that this was where I was really alive, that this had become my homeland. I couldn’t stop doing it. So I was lucky that in the course of my lifetime, the world opened up.

You mentioned earlier how fictionalizing yourself gives you more liberty to explore, that freedom that comes from

fictionalization. How is it different in poetry as opposed to fiction?

Writing in English and writing poetry was a kind of protection, because, as they say, nobody reads poetry. When my first book of poems came out in 1984, with trepidation I gave them as gifts to my mami and papi. And the book sat there proudly on their coffee table, and they never read it. They didn’t know what was inside.

However, when I published How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, I got into immense trouble with la familia. And I thought, “Well, didn’t you read the poems?” When Homecoming came out, I pulled the box into the apartment and I thought, “Oh my god, what have I done? I am going to be in such trouble.” I was trying to calculate how much it would cost me to buy them all and not allow them to be circulated. I was so afraid when I heard my voice in these poems. I was terrified.

It’s that phenomenon where you open the cage of the songbird and it won’t come out. You know, of course, that wonderful title [of Maya Angelou’s memoir] that says, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. But a sequel to that would be, what happens when the door to the cage is open? Will the bird continue singing? Will the bird be silenced, either

world out there, or by the world that you’ve absorbed because you’re afraid? Freedom is a scary thing.

What did it take for you to fly out of the cage, and for you to not be afraid of your own voice anymore? I still am! When a book comes out, I want to pull it. But I feel like I believe in it when I’m writing. I believe in it when I meet another reader and they connect with what I’ve worked on. That connection gives me bravery. Something that is really important, too, about freedom—it’s never a done deal. It’s a continuing process, and you constantly have to be vigilant and keep challenging yourself. I once had a young student who wrote a little poem that I always remember. She said: “Why do I want to reach for the stars, but I never get past the front door?” I said, “Welcome to the human condition.” We want this kind of freedom and release, and yet our little lives and our little containers in our little houses of what we’re prescribed don’t let us achieve that freedom. But it’s important to keep reaching and to keep trying. Because the house gets bigger, and the front door wider, and one day, who knows where you’ll be able to fly.

“How Julia Alvarez Wrote Her Many Selves into Existence” | Use the checklist and chart to notice and wonder about the text.

□ skim the title page and copyright page to gather information about the publication.

□ skim for text features (maps, diagrams, captions, subtitles, section headings, bold or italic words).

□ skim the first few paragraphs and last few paragraphs of the text to see if you can determine the topic.

A checklist with heading labeled Informational. Below is a two-column chart with headings labeled Notice and Wonder. Notice Wonder

“How Julia Alvarez Wrote Her Many Selves into Existence” | Write relevant information in each column.

A four column chart with headings labeled Paragraphs, Annotations about Poetry, Benefits of Poetry, and Parallels in The Crossover.

• “touch bottom in myself”

• “meeting up against the silence”

• “a little enlightenment or a little awareness” understanding of the self

The Crossover | Cut out each sentence, and work with a partner to categorize the sentences according to what makes Josh angry.

Dad tried to dunk.

I can’t win a championship if I’m sitting in this smelly hospital.

I want to win a championship.

Dad told you he’d be here forever.

I thought forever was like Mars— far away.

It turns out forever is like the mall— right around the corner.

Jordan doesn’t talk basketball anymore.

Jordan cut my hair and didn’t care.

He’s always drinking Sweet Tea.

Sometimes I get thirsty.

I don’t have anybody to talk to now.

I feel empty with no hair.

CPR DOESN’T WORK!

My crossover should be better.

If it was better, then Dad wouldn’t have had the ball.

If Dad hadn’t had the ball, then he wouldn’t have tried to dunk.

If Dad hadn’t tried to dunk, then we wouldn’t be here.

I don’t want to be here.

The only thing that matters is swish.

Our backboard is splintered.

I quickly finish the dessert. I have to jump to get the ball. It is stuck in the goal, evidence of JB not dunking.

I tap it out and dribble to the goal.

The Crossover | Complete each column based on an example of figurative language from the text.

A four-column chart with headings labeled Basketball-Specific Language, Literal Meaning, Josh’s Meaning, and Relationship to Josh’s Conflict.

Basketball-Specific Language Literal Meaning Josh’s Meaning Relationship to Josh’s Conflict

The Crossover | Choose an emerging theme and gather supporting evidence from pages 89–237 of the text.

A three-column chart with headings labeled Emerging Theme, Evidence, and Theme. Emerging Theme

dreary (adj.): causing unhappiness or sad feelings

ponder (v.): to think about or consider something carefully

weary (adj.): lacking strength, energy, or freshness because of a need for rest or sleep

volume (n.): a book that is part of a series or set of books

lore (n.): traditional knowledge, beliefs, and stories that relate to a particular place, subject, or group

rap (v.): to quickly hit or knock something several or many times

bleak (adj.): not warm, friendly, cheerful, etc.

wrought (v.): worked; archaic

morrow (n.): the next day

vainly (adv.): without success; without producing a good or desired result

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

“’Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door—

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;—

This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer, “Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door, That I scarce was sure I heard you”—here I opened wide the door;— Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortals ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token, And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?”

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!”— Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning, Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

“Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice; Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore—

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;—

’Tis the wind and nothing more!”

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door—

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

surcease (n.): an ending entreat (v.): to ask someone in a serious and emotional way

implore (v.): to make a very serious or emotional request to someone; beg

scarce (adj.): almost not at all; hardly

peer (v.): to look closely or carefully especially because something or someone is difficult to see

mortal (n.): a human being

lattice (n.): a frame or structure made of crossed wood or metal strips

flirt (n.): a sudden movement yore (n.): the past obeisance (n.): a movement of your body (such as bowing) that shows respect for someone or something

mien (n.): a person’s appearance or facial expression

Pallas (n.): Athena; the Greek goddess of wisdom

ebony (adj.): very dark or black

beguile (v.): to trick or deceive someone

decorum (n.): correct or proper behavior that shows respect and good manners

countenance (n.): the appearance of a person’s face; a person’s expression

shear (v.): to cut the hair, wool, etc. off an animal

craven (adj.): having or showing a complete lack of courage; very cowardly

ghastly (adj.): very shocking or horrible

plutonian (adj.): related to the world of the dead

quoth (v.): said nevermore (adj.): not happening again; never again

ungainly (adv.): moving in an awkward or clumsy way; not graceful

fowl (n.): a bird of any kind

discourse (n.): the use of words to exchange thoughts and ideas

bear (v.): to have something as a feature or characteristic

bust (n.): a sculpture of a person’s head and neck and usually a part of the shoulders and chest

utter (v.): to say something

aptly (adv.): appropriately or suitably

dirge (n.): a slow song that expresses sadness or sorrow

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore, “Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven, Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning—little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blest with seeing bird above his chamber door—

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as “Nevermore.”

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing farther then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered, “Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.”

Then the bird said “Nevermore.”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken, “Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore—

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never—nevermore’.”

But the Raven still beguiling all my fancy into smiling, Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door; Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore—

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core; This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er, But whose velvet-violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er, She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

“ Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee—by these angels he hath sent thee Respite—respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

melancholy (adj.): feeling or showing sadness; very unhappy

ominous (adj.): suggesting that something bad is going to happen in the future

divine (v.): to discover or understand something without having direct evidence

censer (n.): a container that holds burning incense

seraph (n.): a type of angel that is described in the Bible; an angel of the highest rank

wretch (n.): a very unhappy or unlucky person

respite (n.): a short period of time when you are able to stop doing something that is difficult or unpleasant or when something difficult or unpleasant stops or is delayed

nepenthe (n.): an ancient drug that helps people forget sadness and pain

quaff (v.): to drink a large amount of something quickly

tempest (n.): a violent storm—often used figuratively

balm of Gilead (n.): a medicine mentioned in the Bible

laden (adj.): loaded heavily with something; having or carrying a large amount of something

Aidenn (n.): paradise

fiend (n.): an evil spirit; a demon or devil

plume (n.): a feather or group of feathers on a bird

flit (v.): to move or fly quickly from one place or thing to another

pallid (adj.): very pale in a way that suggests poor health

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore—

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn, It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting—

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

“The Raven” | Use the checklist and chart to notice and wonder about the text.

A checklist with heading labeled Literary. Below is a two-column chart with headings labeled Notice and Wonder.

□ read the title and subtitle.

□ skim the first few lines and last few lines of the text to see if you can determine the main ideas.

□ Identify genre features (e.g., act numbers, line numbers, stanzas, journal dates).

□ skim the entire text.

Notice Wonder

Exposition

“The Raven” | In each box, write phrases or sentences to summarize the narrative arc element indicated.

Boxes with headings labeled Characters, Setting, Conflict, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Resolution. The Characters, Setting, and Conflict boxes are stacked vertically within a surrounding box labeled Exposition. A flat line under the Exposition box slants upward under the Rising Action box. The line comes to a point next to the Climax box. The line slants downward next to the Falling Action box. The line is flat again under the Resolution box.

Rising Action

Characters

Setting

Conflict

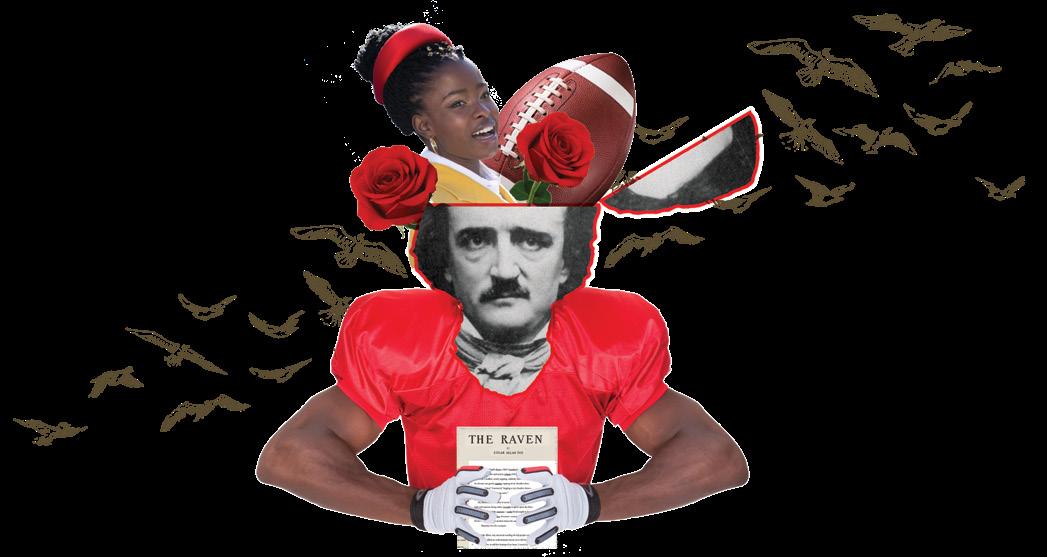

by Brandon Griggs, CNN

Poetry and football. Two words you don’t often hear in the same sentence.

One is a lyrical, niche art form. The other is a violent, mass-consumed sport. There’s something discordant about putting them together, like a mash-up gone wrong or two mismatched people on a bad date.

And yet Amanda Gorman, fresh off her stunning appearance at President Biden’s inauguration, will recite an original poem today at Super Bowl LV in Tampa. It’ll mark the first time poetry has been

an official part of America’s biggest unofficial holiday.

Poetry has no business at a football game, you might say. Football games are for stirring renditions of the national anthem, neck-twisting military flyovers, the unfurling of vast American flags at stadiums packed with cheering fans. Pageantry, not poetry.

Poetry, on the other hand, is for Elizabethans, swooning lovers, starving writers and dreamy prep school boys under the spell of Robin Williams. It

is traditionally consumed quietly, in a personal pact between poet and reader, without marching bands or Bud Light commercials.

The two seem SO different. After all, football is measured in yards, poetry in meters.

There’s no crying in baseball. And there’s no poetry in football. That’s the perception, anyway.

The perception is wrong.

“At their best, football and poetry both reach sort of a state of grace,” says Quentin Ring, executive director of Beyond Baroque, a literary arts center in Venice, California, where Gorman took poetry workshops as a teenager. “When you see somebody like Tom Brady when he’s in the zone, it’s sublime. And poetry is also something that large numbers of people can be enraptured by.”

“Football combines two of the worst things in American life,” George Will once said. “It is violence punctuated by committee meetings.”

Poetry, on the other hand, has been called nothing less than “the history of the human soul.”

But yes, there is poetry in football.

thrown spiral, the slow-motion ballet of a halfback weaving through tacklers, ESPN’s Chris Berman rhapsodizing about “the frozen tundra of Lambeau Field.”

There’s also history.

The Baltimore Ravens are named for “The Raven,” the famous poem by Edgar Allan Poe, who spent the later part of his life in the city.

Cleveland Browns defensive end Myles Garrett, the first overall pick in the 2017 NFL draft, is 6-foot-4, 272 pounds and hell on opposing quarterbacks.

He also loves the poetry of Maya Angelou, and writes poems in his spare time.

“If I’m feeling stress or anxiety, I’ll escape into another world. With books, you’re going on an adventure, imagining and wondering. Poetry is different,” he told ESPN. “When you’re a poet, or reading poems, you feel every single word.”

Garrett is just one of numerous NFL players who have dabbled in writing verse.

Another, Seattle Seahawks receiver

Tyler Lockett, wrote a poem, “Reality vs. Perception,” about social injustice and the prejudices Black men face in America. It goes, in part: When I look in the mirror, I see more than a Black man

But what do you see, America?

An entertainer? An athlete? What else do you see?

A gangbanger? A drug dealer?

A criminal? A lowlife?

Why not a lawyer? Why not a doctor? Why not a son? Why not a father?

A video of Lockett and other star NFL players reciting the poem is on the NFL’s website.

Even Tom Brady has been known to share poetry as a way of getting fired up for a game – as he did on Instagram before his last Super Bowl appearance two years ago. It must have worked. He won.

Instead she will recite an original poem recognizing three honorary captains at the Super Bowl – a nurse, a teacher and a veteran – “who served as leaders in their respective communities during the global pandemic.”

It’s just the latest in a flurry of recent triumphs for Gorman, the nation’s first-ever youth poet laureate.

Ring remembers Gorman from her years in the poetry program at Beyond Baroque and was immediately struck by her precocious talent.

“It was pretty clear that she was destined for great things,” he says.

Ring couldn’t have imagined those great things would include bringing the ancient art of poetry to America’s biggest sports spectacle.

But he says the pairing of poetry and football is not the shotgun marriage it may seem. Like football, spoken-word poetry is a communal activity. And like football, its carefully chosen words can land with impact.

“There’s a physicality to it,” he says.

“People can actually feel it when Amanda is reading her poetry.”

Some, watching Gorman tonight, will feel it. Some will shrug and turn back to their chicken wings. But the Super Bowl will never be quite the same.

Module 1 | Add notes about your peer’s declamation to help them improve their articulation and demeanor.

A two-column chart with headings labeled Component and Explanation of Performance.

Component

Articulation: Does your peer pronounce words clearly?

Explanation of Performance

Demeanor: Does your peer appear to be relaxed and confident?

trans | In the ovals, write words that contain the root trans

A circle in the center for the root trans. Lines branch off the circle in different directions. The lines connect the central circle to five other circles.

Inferred definition:

Talking Tool

Can you elaborate on ?

What evidence supports your idea? How does your idea relate to ?

Overall, . For example, Additionally, .

I hear you say that . This changes my mind about

I hear you say that . However, there is also evidence that .

In the text,

According to the author, . The author states that

This evidence illustrates . This evidence proves

Prompt: Write a narrative poem, and then write an explanatory paragraph about the poem.

• Step 1: Write a narrative poem from Alexis’s point of view about a series of events that led to an internal change.

• Step 2: Write an explanation of how you incorporated the following elements of narrative poetry into your poem: narrative arc, form, and figurative language.

Two columns. The first column has a writing sample. The second column is labeled Notes.

Day

Notes I YAWN,

Dad yells, Alexis, get out of bed!

You can’t be late for your FIRST DAY. I got this Dad. I’m the MVP. The aroma of scrambled eggs and toast sneaks into the room. I get dressed to perfection. But I can’t find my green kicks,

which makes me feel like I’m going to be sick. Those sneakers make me the Alexis that I am, but I grab my new pink ones, force their stiff leather onto my feet, and sigh as I lace them.

My game plan was so simple: New school, but the same me.

Alexis with the green kicks, guard attitude, and sweet tea.

Alexis in the starting five.

That’s who I am: Alexis the champion. That’s how everyone knows me.

But at lunch, stiff pink sneakers on my feet, I sit alone, a benchwarmer, but all eyes on me.

I refuse to look in any one direction, feeling the weight of a hundred gazes.

A strange, frightened Alexis shows up out of nowhere. All alone, nerves like a live wire.

I stop, take a deep breath, consider my next move.

Next, I walk up to the twins from English class and say, Hey.

We talk and then I walk away because now she’s back, the familiar, confident Alexis scoring points and stealing plays. My time to shine comes in fifth-period gym.

In the locker room, the girls talk, but not to me.

So I imagine Alexis the starter. She runs across the court in her green kicks. She makes a perfect leap and gets so much air and

my fantasy.

I’m so nervous my breath and body are shaking, the live wire running through me, but I’m finally part of something. I’m demonstrating for all my skill.

I run to the hoop, fake right, run left.

I make the perfect layup. The ball twists around the rim once, twice, then ... falls out.

A missed shot and I become a benchwarmer again.

Pink sneakers, alone, and bad at basketball, is not who I—

A tap on my shoulder shocks me.

A girl on the court smiles.

Love the sneakers, she says.

Thanks! They’re not the ones I normally wear, I reply.

I love pink sneakers too! We could be twins, like Josh and JB.

I look down and see she’s wearing the same pink sneakers I’ve got on.

Who are you sitting with at lunch tomorrow?

Probably nobody like I did today. But it’s okay.

Any chance you’d want to sit with us?

Yeah, I’d love to! Thanks for inviting me!

We talk some more on our way into the locker room.

She used to be the new girl and struggled to be herself too.

During dinner,

I start to tell my dad about my day.

I found your green kicks in the garage, Alexis, but you can’t resist change. It will keep coming for you.

I know that now. But I don’t have to let it completely redefine me.

My day at school was like a game of basketball. I missed a few shots, in gym class and at lunch, but I rebounded and kept playing, so I walked away with a win: a friend.

Because I’m still Alexis the starter, even if I have different shoes on my feet, even if I have to sit out a quarter as a benchwarmer.

I’m still Alexis the champion and I can still get to the goal, even if I travel to it a different way.

And I smile because if one thing never changes and always makes perfect sense, it’s basketball.

Notes

I decided to make Alexis’s first day of school the narrative arc. The rising actions are Alexis getting ready for school and eating alone at lunch. Alexis really likes basketball, so her missing the shot in gym class is the climax. When she meets a new friend, that’s the falling action. Her lesson that things in life change was the resolution. I wrote the poem in free verse so I could use different things from the poems in The Crossover. I used couplets when Alexis talks to the smiling girl because that shows how their conversation was like passing a basketball back and forth. I used the metaphor “alone, a benchwarmer” to show how Alexis feels left out and to point out how important basketball is to Alexis. I repeated the word “alone” to help emphasize that feeling to the reader.

Notes

Prompt: Write a narrative poem, and then write an explanatory paragraph about the poem.

• Step 1: Write a narrative poem from Alexis’s point of view about a series of events that led to an internal change.

• Step 2: Write an explanation of how you incorporated the following elements of narrative poetry into your poem: narrative arc, form, and figurative language.

Two columns. The first column has a writing sample. The second column is labeled Notes.

I YAWN, GROAN, and

Dad yells, Alexis, get out of bed!

You can’t be late for your FIRST DAY.

I got this Dad. I’m the MVP.

The aroma of scrambled eggs and toast sneaks into the room.

I get dressed to perfection like I dribble up the middle.

But I can’t find my green kicks.

They’re not in my closet.

They’re not in my bed.

They’re just a vision in my head.

I feel like I’m going to be sick. Those sneakers make me the Alexis that I am,

But I grab my new pink ones, force their stiff leather onto my feet, and sigh as I lace them.

My game plan was so simple: New school, but the same me.

Alexis with the green kicks, guard attitude, and good sweet tea.

Alexis in the starting five.

That’s who I am: Alexis the champion.

That’s how I’m known and how I make friends.

But at lunch, stiff pink sneakers on my feet, I sit alone, a benchwarmer, but all eyes on me.

I refuse to look in any one direction, feeling the weight of waiting under a hundred gazes.

A strange, frightened Alexis shows up out of nowhere.

All alone, nerves like a live wire.

I stop, take a deep breath, consider my next move.

Sometimes intimidation is an easy path to victory.

I walk up to the twins from English class and say, Hey.

We talk and then I walk away because she’s back, the perfect rebound, the familiar, confident Alexis scoring points and stealing plays.

My time to shine comes—fifth-period gym.

In the locker room, the girls chatter and chill while

I visualize Alexis the starter, racing and running across the court in her green kicks. She makes a perfect leap and gets so much air and

The whistle interrupts my reverie. Then I’m on the court for real.

I’m so nervous my breath and body are shaking, the live wire running through me, but I’m finally part of something. I’m demonstrating for all my skill, my passion, my play.

I run to the hoop.

I fake right. I run left.

I make the perfect layup, a graceful arc in the air.

Pink sneakers, alone, and bad at basketball is not who I—

A tap on my shoulder shocks me, like too much lemon in a sweet iced tea.

Love the sneakers, a girl on the court smiles. Thanks! They’re a different color but my same style.

I love pink sneakers too! We could be twins, like Josh and JB.

I look down and see she’s wearing the same pink sneakers on her feet.

Who are you sitting with at lunch tomorrow?

Probably nobody like I did today. But it’s okay.

Any chance you’d want to sit with us?

Yeah, I’d love to! Thanks for inviting me!

We talk some more on our way into the locker room.

She used to be the new girl and struggled to be herself too.

Over meat loaf and mashed potatoes, I start to tell my dad about my day.

I found your green kicks in the garage, Alexis, but you can’t resist change. It will keep coming for you. I know.

Life is like basketball.

Champions don’t let the unexpected throw them off their game. Champions rebound and keep playing.

That’s what I did today.

I’m still Alexis the champion, whether I’m in green or pink kicks or whether I get benched

because I keep my focus on the hoop even if I realize the path to it may need to change. I decided to shape the narrative arc around Alexis’s first day to show what her experiences at a new school would have been like. The rising actions are Alexis eating alone at lunch and saying hi to the twins. Because Alexis is obsessed with basketball, the climax occurs when she misses the shot in gym class. Her conversation with the smiling girl is when Alexis begins to feel better. This ultimately leads to the resolution of her story because Alexis feels less conflicted about being the new girl and having to accept change. I wrote the poem in free verse to allow me to use different elements from the poems in The Crossover, such as couplets during the discussion between Alexis and the smiling girl. Their conversation mirrors the act of passing a basketball back and forth. I used similes and metaphors like “dressed to perfection like I dribble up the middle” and “alone, a benchwarmer” to highlight how basketball is an integral part of

Notes

Alexis’s life. I repeated the word “alone” to help the reader understand how isolated Alexis feels as the new girl.

Notes

Writing Model | Write a narrative poem, and then write an explanatory paragraph about the poem.

Step 1: Write a narrative poem from Alexis’s point of view about a series of events that led to an internal change.

Step 2: Write an explanation of how you incorporated the following elements of narrative poetry into your poem: narrative arc, form, and figurative language.

Checklist with headings labeled Knowledge, Writing, and Language. To the right are two columns labeled Review 1 and Review 2. At the bottom are two boxes labeled Review 1 Comments and Review 2 Comments.

Step 1

Knowledge

shows knowledge of how narrative poetry combines elements of storytelling with poetic form shows knowledge of how figurative language creates comparisons and images shows knowledge of how external events prompt an internal change

Writing

1

2

1

2 uses narrative elements to logically establish, propel, and reflect on narrated events and experiences uses a consistent point of view from which to develop characters and events uses description, dialogue, and reflection to develop characters and events uses transition words and phrases to sequence events and signal shifts in time and place uses one or more of the poetic forms in The Crossover uses descriptive details, including precise words and phrases and/or sensory language, to convey action, events, and experiences

Language

1

2 uses commas and ellipses to indicate pauses or breaks spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Step 2

Knowledge Review 1 Review 2 shows knowledge of narrative arc elements and refers to specific examples shows knowledge of form and refers to specific examples shows knowledge of figurative language and refers to specific examples

Writing Review 1 Review 2 uses precise language and topic-specific vocabulary to explain ideas in the reflective paragraph

Language Review 1 Review 2 spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Writing Model | Use this planner as a resource as you expand your ideas into a draft of a narrative poem for the End-of-Module Task.

A two-column chart with headings labeled Narrative Structure and Images and Sensory Details.

Narrative Structure Images and Sensory Details

Exposition

Characters and Important Characteristics

Main

Alexis Supporting Alexis’s dad

JB

Josh coach girl on court

Setting Where Alexis’s home new school gym lunchroom

When before, after, and during her first day

Conflict

Alexis wants to be her old self even though it’s a new school.

• loves basketball

• pink sneakers

• basketball court

• noisy lunchroom

• image of new Alexis versus image of old Alexis

Rising Action

First

First, Alexis wakes up and gets ready for her first day of school.

• dresses well

• sweet tea

• acts like her old self is a rebound

• screech of a whistle

Next

Next, Alexis sits alone at lunch, but she decides to introduce herself to the twins.

Then

Then, Alexis goes to gym class and plays a game of basketball.

Climax

So or When

When Alexis misses her final shot, she loses confidence in her ability to be her same self …

Because

… because being good at basketball is an important part of Alexis’s identity.

• ball spins around and around and around the rim

Narrative Structure (continued)

Falling Action

Next

Next, a girl in gym class notices Alexis’s pink sneakers.

• used to be new girl too

Then

Then, the girl invites Alexis to eat lunch with her the next day.

Resolution

Finally Alexis gets to know her classmate.

Reflection

What the Character(s) Learn

Finally, Alexis realizes she doesn’t have to be exactly the same as she was at her old school in order to make a new friend.

Why It Matters

Life always involves change as we grow.

1. Identify a poetic form that could support your poem’s content. couplets to show back-and-forth of a conversation

2. How does this poetic form support the content? conversation like passing a basketball back and forth—one person throws, then the next person throws

3. Identify an example of figurative language that you could use in your poem. the image of the basketball court to explain the isolation Alexis feels

4. How does this example of figurative language support the content? reinforces Alexis’s love of basketball and the importance of her loneliness

Prompt: Write a narrative poem about The Crossover, and then write an explanatory paragraph about your poem.

Step 1 | Write a narrative poem about the beginning of The Crossover from a character’s perspective. Choose one character from the list.

• JB

• Dad

• Mom

Step 2 | Write an explanation of how you incorporated specific examples of figurative language into your poem.

Module Task 1 | Write a narrative poem about The Crossover, and then write an explanatory paragraph about your poem.

Step 1: Write a narrative poem about the beginning of The Crossover from a character’s perspective. Choose one character from the list.

• JB

• Dad

• Mom

Step 2: Write an explanation of how you incorporated specific examples of figurative language into your poem.

Checklist with headings labeled Knowledge, Writing, and Language. To the right are two columns labeled Review 1 and Review 2. At the bottom are two boxes labeled Review 1 Comments and Review 2 Comments. Step 1

Knowledge

shows knowledge of how narrative poetry combines elements of storytelling with poetic form shows knowledge of how figurative language creates comparisons and images shows knowledge of The Crossover

Writing

1

2

1

2 uses narrative elements to logically establish the exposition and rising action of a single event uses ideas from “Warm Up” and “First Quarter” to inform narrative choices

uses a consistent point of view from which to develop characters and events uses description to develop characters and events uses transition words and phrases to sequence events and signal shifts in time and place uses descriptive details, including precise words and phrases and/or sensory language, to convey action, events, and experiences

Language

1

2 uses commas and ellipses to indicate pauses or breaks spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Step 2

Knowledge Review 1 Review 2 shows knowledge of figurative language and refers to specific examples

Writing

1

2 uses precise language and topic-specific vocabulary to explain ideas

Language Review 1 Review 2 spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Review 1 Comments Review 2 Comments

Module Task 1 | Add ideas to plan a narrative poem in response to Module Task 1.

A two-column chart with headings labeled Narrative Structure, and Images and Sensory Details.

Narrative Structure

Exposition

Characters and Important Characteristics

Main

Supporting

Images and Sensory Details

Rising Action

Prompt: Write a narrative poem about The Crossover, and then write an explanatory paragraph about your poem.

Step 1 | Write a narrative poem that develops the beginning, middle, and end of the basketball game in “Fast Break” and “Storm” from one character’s point of view. Incorporate one of the poetic forms that appears in The Crossover. Choose one character from the list.

• JB

• Dad

• Mom

Step 2 | Write an explanation of how you incorporated one or more specific examples of a poetic form used in The Crossover into your poem.

Module Task 2 | Write a narrative poem about The Crossover, and then write an explanatory paragraph about your poem.

Step 1: Write a narrative poem that develops the beginning, middle, and end of the basketball game in “Fast Break” and “Storm” from one character’s point of view. Incorporate one of the poetic forms that appears in The Crossover. Choose one character from the list.

• JB

• Dad

• Mom

Step 2: Write an explanation of how you incorporated one or more specific examples of a poetic form used in The Crossover into your poem.

Checklist with headings labeled Knowledge, Writing, and Language. To the right are two columns labeled Review 1 and Review 2. A the bottom are two boxes labeled Review 1 Comments and Review 2 Comments.

Step 1

Knowledge

2 shows knowledge of how narrative poetry combines elements of storytelling with poetic form shows knowledge of how external events can prompt an internal change shows knowledge of The Crossover

Writing

uses narrative elements to logically propel a single event in The Crossover through climax, falling action, and resolution uses ideas from The Crossover to inform narrative choices uses a consistent point of view from which to develop characters and events

uses dialogue and reflection to develop characters and events uses transition words and phrases to sequence events and signal shifts in time and place uses one or more of the poetic forms in The Crossover uses descriptive details, including precise words and phrases and/or sensory language, to convey action, events, and experiences

Language Review 1 Review 2 uses commas and ellipses to indicate pauses or breaks spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Step 2

Knowledge Review 1 Review 2 shows knowledge of form and refers to specific examples

Writing Review 1 Review 2 uses precise language and topic-specific vocabulary to explain ideas

Language Review 1 Review 2 spells grade-appropriate words correctly Review 1 Comments Review 2 Comments

Module Task 2 | Add ideas to plan a narrative poem in response to Module Task 2. A two-column chart with headings labeled Narrative Structure and Images and Sensory Details.

Narrative Structure Images and Sensory Details

Exposition Characters and Important Characteristics

Main Supporting

Setting Where When

Conflict

Narrative Structure (continued)

Falling Action

Resolution

Reflection

What the Character(s) Learn

Why It Matters

Images

1. Identify a poetic form that could support your poem’s content.

2. How does this poetic form support the content?

3. Identify an example of figurative language that you could use in your poem.

4. How does this example of figurative language support the content?

Prompt: Write a personal narrative poem, and then write an explanatory paragraph about your poem.

Step 1 | Write a narrative poem about an event or series of events in your life that could be considered a crossover. In your poem, incorporate one of the poetic forms that appears in The Crossover

Step 2 | Write an explanation of how you incorporated the following elements of narrative poetry into your poem: narrative arc, figurative language, a poetic form used in The Crossover.

End-of-Module Task | Write a personal narrative poem, and then write an explanatory paragraph about your poem.

Step 1: Write a narrative poem about an event or series of events in your life that could be considered a crossover. In your poem, incorporate one of the poetic forms that appears in The Crossover

Step 2: Write an explanation of how you incorporated the following elements of narrative poetry into your poem: narrative arc, figurative language, a poetic form used in The Crossover.

Checklist with headings labeled Knowledge, Writing, and Language. To the right are two columns labeled Review 1 and Review 2. At the bottom are two boxes labeled Review 1 Comments and Review 2 Comments. Step 1

Knowledge Review 1 Review 2 shows knowledge of how narrative poetry combines elements of storytelling with poetic form shows knowledge of how figurative language creates comparisons and images shows knowledge of how external events can prompt an internal change

Writing Review 1 Review 2 uses narrative elements to logically establish, propel, and reflect on narrated events and experiences uses a consistent point of view from which to develop characters and events uses description, dialogue, and reflection to develop characters and events

uses transition words and phrases to sequence events and signal shifts in time and place uses one or more of the poetic forms in The Crossover uses descriptive details, including precise words and phrases and/or sensory language, to convey action, events, and experiences

Language Review 1 Review 2 uses commas and ellipses to indicate pauses or breaks spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Step 2

Knowledge Review 1 Review 2

shows knowledge of narrative arc elements and refers to specific examples shows knowledge of form and refers to specific examples shows knowledge of figurative language and refers to specific examples

Writing Review 1 Review 2 uses precise language and topic-specific vocabulary to explain ideas

Language Review 1 Review 2 spells grade-appropriate words correctly

Review 1 Comments Review 2 Comments

End-of-Module Task | Add ideas to plan a narrative poem in response to the End-of-Module Task.

A two-column chart with headings labeled Narrative Structure and Images and Sensory Details.

Narrative Structure Images and Sensory Details

Exposition Characters and Important Characteristics

Main Supporting

Setting Where When

Conflict

Rising Action

Falling Action

Resolution

Reflection

What the Character(s) Learn

Why It Matters

1. Identify a poetic form that could support your poem’s content.

2. How does this poetic form support the content?

3. Identify an example of figurative language that you could use in your poem.

4. How does this example of figurative language support the content?

Module 1 | Use the space below to draft sentences that use the strategies you learn throughout module 1.

Strategy 1: Use participles to add description or details.

participle (n.): a form of a verb that is used to indicate past or present action and that can also be used like an adjective

Examples: deserted, moving, dressed, posted

Sample Sentence: Narrative poems contain fascinating plots.

Your Turn

Narrative poetry includes interesting . the narrative poem “exile” contains a number of settings, such as the imagined

In “exile,” the narrative arc includes the speaker’s fleeing family . the swimming metaphor in “exile” highlights revealing

Strategy 2: Use infinitives to add description or details.

infinitive (n.): the basic form of a verb, usually used with the word to Examples: to develop, to gloat, to dress

Sample Sentence: To convey narratives, poems may include elements of narrative arc such as conflict, character, and setting.

Your Turn

Poets create comparisons to develop .

A feature of narrative poetry to include in one’s writing is

Narrative poets want to communicate .

Internal conflict can help to move

Strategy 3: Use gerunds to add specific and precise details. gerund (n.): an english noun formed from a verb by adding -ing Examples: walking, playing, listening, going

Sample Sentence: Reading narrative poems aloud allows the reader to hear unique sound devices that poets craft.

Your Turn

Developing themes and universal ideas .

Poetic form can be used for creating,

Writing a narrative poem .

Crafting figurative language

“Exile”

1. Ask a friend or adult to listen to you read.

2. Read aloud the fluency passage three to five times.

3. Focus on the day’s fluency element as you read.

4. Ask the listener to initial and comment below. A two-column chart with headings labeled Initials and Comments.

Initials

Comments

Day 1

Accuracy

Day 2

Phrasing

Day 3

Expression

Day 4

Rate

Performance

Fluency Elements

Accuracy: Correctly decode the words. Phrasing: Group words into phrases, and pause for punctuation. Expression: Use voice to show feeling. Rate: Read at an appropriate speed.

“Exile,” lines 17–36

by Julia Alvarez

Something was off, I knew, but I was young and didn’t think adult things could go wrong. So as we quietly filed out of the house we wouldn’t see again for another decade, I let myself lie back in the deep waters, my arms out like Jesus’ on His cross, and instead of sinking down as I’d always done, magically, that night, I could stay up, floating out, past the driveway, past the gates, in the black Ford, Papi grim at the wheel, winding through back roads, stroke by difficult stroke, out on the highway, heading toward the coast.

Past the checkpoint, we raced towards the airport, my sisters crying when we turned before the family beach house, Mami consoling, there was a better surprise in store for us!

She couldn’t tell, though, until … until we were there. But I had already swum ahead and guessed some loss much larger than I understood, more danger than the deep end of the pool.

The Crossover, passage 1

1. Ask a friend or adult to listen to you read.

2. Read aloud the fluency passage three to five times.

3. Focus on the day’s fluency element as you read.

4. Ask the listener to initial and comment below. A two-column chart with headings labeled Initials and Comments.

Initials

Comments

Day 1

Accuracy

Day 2

Phrasing

Day 3

Expression

Day 4

Rate

Performance

Fluency Elements

Accuracy: Correctly decode the words. Phrasing: Group words into phrases, and pause for punctuation. Expression: Use voice to show feeling. Rate: Read at an appropriate speed.

“Dribbling,” The Crossover, passage 1, page 3 by

Kwame Alexander

At the top of the key, I’m MOVING & GROOVING, POPping and ROCKING— Why you BUMPING? Why you LOCKING?

Man, take this THUMPING. Be careful though, ’cause now I’m CRUNKing CrissCROSSING

The Crossover, passage 2

1. Ask a friend or adult to listen to you read.

2. Read aloud the fluency passage three to five times.

3. Focus on the day’s fluency element as you read.

4. Ask the listener to initial and comment below. A two-column chart with headings labeled Initials and Comments.

Initials

Comments

Day 1

Accuracy

Day 2

Phrasing

Day 3

Expression

Day 4

Rate

Performance

Fluency Elements

Accuracy: Correctly decode the words. Phrasing: Group words into phrases, and pause for punctuation. Expression: Use voice to show feeling. Rate: Read at an appropriate speed.

“Mom shouts,” lines 1–16, The Crossover, passage 2, page 74

by Kwame Alexander

Get a checkup. Hypertension is genetic. I’m fine, stop high-posting me, baby, Dad whispers.

Don’t play me, Charles—this isn’t a basketball game.

I don’t need a doctor, I’m fine.

Your father didn’t “need” a doctor either. He was alive when he went into the hospital.

So now you’re afraid of hospitals?

Nobody’s afraid. I’m fine. It’s not that serious.

Fainting is a joke, is it?

I saw you, baby, and I got a little excited. Come kiss me.

Don’t do that … Baby, it’s nothing. I just got a little dizzy.

You love me?

Like summer loves short nights.

Get

The Crossover, passage 3

1. Ask a friend or adult to listen to you read.

2. Read aloud the fluency passage three to five times.

3. Focus on the day’s fluency element as you read.

4. Ask the listener to initial and comment below. A two-column chart with headings labeled Initials and Comments.

Initials

Comments

Day 1

Accuracy

Day 2

Phrasing

Day 3

Expression

Day 4

Rate

Performance

Fluency Elements

Accuracy: Correctly decode the words. Phrasing: Group words into phrases, and pause for punctuation. Expression: Use voice to show feeling. Rate: Read at an appropriate speed.

“Second-Person,” The Crossover, passage 3, pages 114–115

by Kwame Alexander

After practice, you walk home alone. This feels strange to you, because as long as you can remember there has always been a second person. On today’s long, hot mile, you bounce your basketball, but your mind is on something else.

Not whether you will make the playoffs. Not homework.

Not even what’s for dinner. You wonder what JB and his pink Reebok–wearing girlfriend are doing. You do not want to go to the library. But you go.

Because your report on The Giver is due tomorrow.

And JB has your copy. But he’s with her. Not here with you. Which is unfair.

Because he doesn’t argue with you about who’s the greatest, Michael Jordan or Bill Russell, like he used to.

Because JB will not eat lunch with you tomorrow or the next day, or next week.

Because you are walking home by yourself and your brother owns

The Crossover, passage 4

1. Ask a friend or adult to listen to you read.

2. Read aloud the fluency passage three to five times.

3. Focus on the day’s fluency element as you read.

4. Ask the listener to initial and comment below. A two-column chart with headings labeled Initials and Comments.

Initials

Comments

Day 1

Accuracy

Day 2

Phrasing

Day 3

Expression

Day 4

Rate

Performance

Fluency Elements

Accuracy: Correctly decode the words. Phrasing: Group words into phrases, and pause for punctuation. Expression: Use voice to show feeling. Rate: Read at an appropriate speed.

“At

Noon, in the Gym, with Dad,” lines 1–31, The Crossover, passage 4, pages 194–195

by Kwame Alexander

People watching

Players boasting

Me scoring

Dad snoring

Crowd growing

We balling

Me pumping

Dad jumping

Me faking

Nasty shot

Nasty moves

Five–zero

My lead

Next play

Dribble bounce

Dribble steal

Dad laughs

Palms ball

You okay?

Dad

Watch

He

Sweat

1. Ask a friend or adult to listen to you read.

2. Read aloud the fluency passage three to five times.

3. Focus on the day’s fluency element as you read.

4. Ask the listener to initial and comment below. A two-column chart with headings labeled Initials and Comments.

Initials

Comments

Day 1

Accuracy

Day 2

Phrasing

Day 3

Expression

Day 4

Rate

Performance

Fluency Elements

Accuracy: Correctly decode the words. Phrasing: Group words into phrases, and pause for punctuation. Expression: Use voice to show feeling. Rate: Read at an appropriate speed.

“The Raven,” lines 1–18

by Edgar Allan Poe

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December; And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before; So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating