JESS POUND

DOI 10.20933/100001379

Except where otherwise noted, the text in this dissertation is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4 0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

All images, figures, and other third-party materials included in this dissertation are the copyright of their respective rights holders, unless otherwise stated. Reuse of these materials may require separate permission

Abstract

This dissertation explores the relationship between introspection and distraction in contemporary photography, examining how these opposing states of mind are depicted and experienced by viewers. By curating an immersive exhibition in the historic Studio 54, the study investigates how photography bridges the private and public, fostering both personal reflection and societal engagement.

Drawing on Michael Fried’s concepts of absorption and theatricality, alongside theories from Susan Sontag and Heidegger, this research analyses the works of photographers such as Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman, Larry Clark, and Alex Prager. These artists use photography to capture the tension between moments of focused introspection and fragmented distraction, inviting viewers to navigate their dualities.

This dissertation also considers the curatorial strategies employed to create an inclusive and impactful exhibition experience. These include the spatial design of Studio 54, content warnings, and the deliberate placement of artworks to mirror the exhibition’s themes. Ultimately, this study highlights photography’s unique ability to challenge perceptions, evoke empathy, and connect individuals to both them and the broader world through a shared visual language.

List of Figures

Page

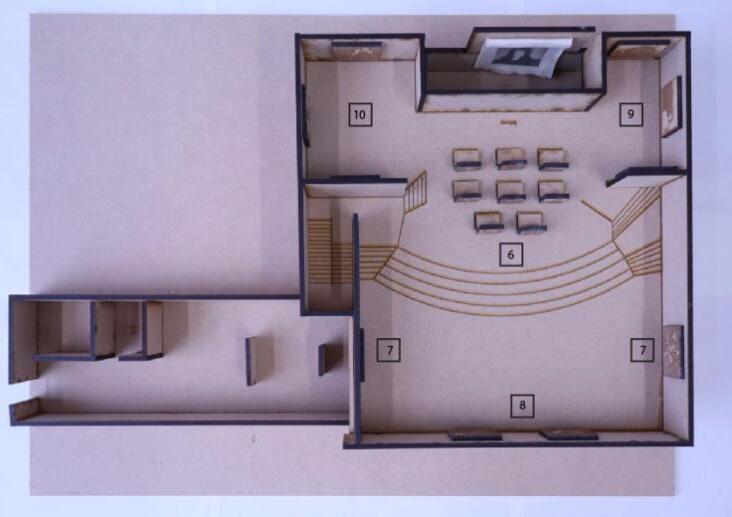

Fig. 1 Pound, J. (2024) Exhibition model Ground floor.

Fig. 2 Pound, J. (2024) Exhibition model Mezzanine.

Fig. 3 Pound, J. (2024) Mock placement of Jeff Wall’s Artwork.

Fig. 4 Wall, J. A Woman with a Covered Tray (2003) [Transparency in lightbox, 164 x 208.5cm]. From Wall, J. (2009) Jeff Wall: the complete edition. London: Phaidon, p190.

Fig. 5 Wall, J. A view from an apartment (2004-5) [Transparency in lightbox, 167 x 244cm]. From Wall, J. (2009) Jeff Wall: the complete edition. London: Phaidon, p186.

Fig. 6 Wall, J. A Woman Consulting a catalogue (2005) [Transparency in lightbox, 165.1 x 133cm]. From Wall, J. (2009) Jeff Wall: the complete edition. London: Phaidon, p188.

Fig. 7 Pound, J. (2024) Mock placement of Bruce Gilden’s Artwork.

Fig. 8 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C. From Gilden, B. (1992)

From Bruce Gilden: facing New York. Cornerhouse, p54

Fig. 9 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C. From Gilden, B. (1992)

From Bruce Gilden: facing New York. Cornerhouse, p60

Fig. 10 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C. From Gilden, B. (1992)

From Bruce Gilden: facing New York. Cornerhouse, p34

Fig. 11 Gilden, B. Untitled (1969-1986) [Gelatine silver print] Coney Island. Available at: https://www.brucegilden.com/coney-island (Accessed: 10 December 2024).

Fig. 12 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C. From Gilden, B. (1992)

From Bruce Gilden: facing New York. Cornerhouse, p19 & 20.

Fig. 13 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Daine Arbus’ Artwork.

Fig. 14 Arbus, D. (1957) Lady on bus [Gelatine silver print, 21.6 × 14.6 cm] N.Y.C.

From Rosenheim, J. et al. (2016) Diane Arbus: in the beginning, 1956-1962. New Haven: Yale University Press, p55.

Fig. 15 Arbus, D. (1951) Female impersonator holding long gloves [Gelatine silver print, 24.8 × 14.9 cm] Hempstead, L.I. From Rosenheim, J. et al. (2016) Diane Arbus: in the beginning, 1956-1962. New Haven: Yale University Press, p13.

Fig. 16 Arbus, D. (1961) Stripper with bare breasts sitting in her dressing room [Gelatine silver print, 24.1 × 16.5 cm] Atlantic City, N.J. From Rosenheim, J. et al. (2016) Diane Arbus: in the beginning, 1956-1962. New Haven: Yale University Press, p185.

Fig. 17 Arbus, D. (1961) Human Pincushion, Robert C. [Gelatine silver print, 24.7 x 16.3 cm] Harrison N.J. From Rosenheim, J. et al. (2016) Diane Arbus: in the beginning, 1956-1962. New Haven: Yale University Press, p186.

Fig. 18 Arbus, D. (1961) Jack Dracula at the bar [Gelatine silver print, 24.9 × 17 cm] New London. From Rosenheim, J. et al. (2016) Diane Arbus: in the beginning, 1956-1962. New Haven: Yale University Press, p175.

Fig. 19 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Nan Goldin’s Artwork.

Fig. 20 Golden, N. (1985) Nan on month after being battered [Slideshow] N.Y.C. From Goldin, N. and Goldin, N. (2012) The ballad of sexual dependency. [New edition]. Edited by M. Heiferman et al. New York: Aperture, p83.

Fig. 21 Golden, N. (1980) Twisting at my birthday party [Slideshow] N.Y.C. From Goldin, N. and Goldin, N. (2012) The ballad of sexual dependency. [New edition]. Edited by M. Heiferman et al. New York: Aperture, p110.

Fig. 22 Golden, N. (1979) Trixy on the cot [Slideshow] N.Y.C. From Goldin, N. and Goldin, N. (2012) The ballad of sexual dependency. [New edition]. Edited by M. Heiferman et al. New York: Aperture, p20.

Fig. 23 The Ballad of Sexual Dependency\ installation view in So the Story Goes, Art Institute of Chicago, 2006. Available at: https://www.artic.edu/artworks/187155/theballad-of-sexual-dependency (Accessed on 27 October 2024).

Fig. 24 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Larry Clark’s Artwork.

Fig. 25 Clark, L. (1971) Untitled, from the series Tulsa [Gelatine silver print]. Clark, L (1971) Tulsa. Edited by Ralph Gibson. Lustrum Press, p47.

Fig. 26 Clark, L. (1971) Untitled, from the series Tulsa [Gelatine silver print]. Clark, L (1971) Tulsa. Edited by Ralph Gibson. Lustrum Press, p49.

Fig. 27 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Cindy Sherman’s Artwork.

Fig. 28 Sherman, C (1977) Untitled Film Still #05 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

From Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003) Cindy Sherman: the complete untitled film stills. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, p57.

Fig. 29 Sherman, C (1978) Untitled Film Still #17 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

From Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003) Cindy Sherman: the complete untitled film stills. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, p67.

Fig. 30 Sherman, C (1978) Untitled Film Still #07 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

From Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003) Cindy Sherman: the complete untitled film stills. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, p21.

Fig. 31 Sherman, C (1977) Untitled Film Still #03 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

From Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003) Cindy Sherman: the complete untitled film stills. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, p75.

Fig. 32 Sherman, C (1978) Untitled Film Still #21 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

From Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003) Cindy Sherman: the complete untitled film stills. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, p35.

Fig. 33 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Alex Prager’s Artwork.

Fig. 34 Pound, J (2024) Second mock placement of Alex Prager’s Artwork.

Fig. 35 Pragre, A. (2013) Face in The Crowd - Crowd #4 New Haven [59.5 x 75 inches].

Available at: https://www.alexprager.com/part-iiview/szvpc8weirn9qa2c33dk5ek2u28gqv. (Accessed on 15 December).

Fig. 36 Pragre, A (2013) Face in The Crowd - Crowd #3 (Pelican Beach) [59 x 92.85 inches]. Available at: https://www.alexprager.com/part-ii-view/x096detl4zsai9w92qlokpdlwri9c6 (Accessed on 15 December).

Fig. 37 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Phillip Lorca DiCorcia’s Artwork.

Fig. 38 Lorca DiCorcia, P. Marco (1978) [Chromogenic print] N.Y.C. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/46273?artist_id=7027&page=1&sov_referrer= artist (Accessed on 15 December).

Fig. 39 Lorca DiCorcia, P. Marilyn; 28 years old (1990-92)[Chromogenic print] Las Vegas, Nevada. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/50353 (Accessed on 15 December).

Fig. 40 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Sophie Calle’s Artwork.

Fig. 41 Pound, J (2024) Second mock placement of Sophie Calle’s Artwork.

Fig. 42 Calle, S. (1979) Gloria K., second sleeper. [Gelatine silver prints 12.6 x 18.4cm]. From Calle, S. (2000) Les dormeurs. Nimes: Editions Actes Sud, p4.

Fig. 43 Calle, S. (1979) Gloria K., second sleeper. [Gelatine silver prints 12.6 x 18.4cm]. From Calle, S. (2000) Les dormeurs. Nimes: Editions Actes Sud, p5.

Fig. 44 Calle, S. (1979) Gloria K., second sleeper. [Gelatine silver prints 12.6 x 18.4cm]. From Calle, S. (2000) Les dormeurs. Nimes: Editions Actes Sud, p6

Fig. 45 Pound, J (2024) Mock placement of Lee Friedlander’s Artwork.

Fig. 46 Friedlander, L. Shadow (1966) [Gelatine silver print 16.0 x 24.1 cm] N.Y.C. The Met Museum available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/266215 (Accessed 15 December).

Fig. 47 Friedlander, L. Tallahassee, Florida (1934) [Gelatine silver print]. Fraenkel Gallery available at: https://fraenkelgallery.com/portfolios/artist/friedlanderlee#friedlander-lee_lee-friedlander-self-portraits_s-5 (Accessed at 15 December).

Fig. 48 Friedlander, L. Maria (1966) [Gelatine silver print 27.9 x 35.6cm] Minneapolis, Minnesota. Fraenkel Gallery available at: https://fraenkelgallery.com/artists/leefriedlander#image-71993-gallery_s-1 (Accessed on 15 December).

Introduction

This exhibition dissertation examines the relationship we as viewers form with contemporary art, be it introspection or distraction, and how these polarising states of mind overlap while in the presence of the artwork Throughout this thesis, I will attempt to represent this phenomenon by curating an immersive installation. This thesis raises questions regarding the audience's role when observing works, ‘I aim to make the viewer aware of his or her responsibility in what he or she is looking at’ Bustamante, J (2008, p. 20). I will continue to reference Micheal Fried’s book Why Photography Matters as Never Before (2008), as well as Absorption and Theatricality (1988), to discuss and pull from his concepts.

The exhibition audience is set to an age range of eighteen and above and is targeted at those with a keen interest in photography Specifically, photography dating from 1970’s New York, although other works from other regions have been selected, the focus remains within this period and location The exhibition would have been open to all ages, but a restriction has been set as a small percentage of the content exhibited is mature. Some of the images contain references to domestic violence, substance use, and nudity. This could be upsetting to some viewers so precautions will be taken in the form of content warnings before entering the space. Inside the venue, the exhibition’s universal themes foster connection, encouraging viewers to see marginalized individuals as reflections of themselves. This perspective cultivates compassion and challenges biases toward underrepresented groups.

Of the artists and artworks curated the exhibition is prominently represented by digital and analogue photography with one exception; a slideshow of images backed by audio. However, it could be argued that aspects of performance and surrealism are also represented. As analogue photography is a main aspect of the curators’ practice, it could be argued that the format of candid photography plays an essential role when discussing the representation of introspection and

distraction through visual media ‘It used to be thought, when the candid images were not common, that showing something that needed to be seen, bringing a painful reality closer was bound to goad viewers to feel more.’ S, Sontag (Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003, p. 31).

When considering the venue space, it needed to be unconventional. Without criticism of the traditional gallery, the typical sanitary setting was deemed unsuitable for this exhibition. The space needed to be for recreational, social, and collective gatherings. In essence, the location had to be connected to escapism This is my reasoning for selecting 254 West 54th Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, more infamously dubbed, ‘Studio 54’ . Formally Gallo Opera House. Studio 54 operated as an exclusive Discotech from 1977 to 1980, it has since been reformed as a Broadway theatre. Owned by two entrepreneurs and long-term friends, Steve Rubell and Mark Fleischman. This classic New York landmark provided an intersection between social space and exhibition by encompassing the backdrop of historical artistic moments. During its term as the nightclub, Studio 54 offered its contribution to the art world. This included the photojournalistic output the club released to boost its infamous status as well as hosting the celebrities who attended the club Entrance was nearly impossible unless you were someone of notability or a renegade of the fashion renaissance of the era. Studio 54 became an exclusive artistic hotspot for the likes of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Grace Jones, and countless others (Irish, A). During an interview with Steve Rubell, the questioning was coincidentally interrupted by Michael Jackson who explained his recurring attendance ‘It’s where you come to when you want to escape, it’s really escapism.’ (Jackson, M) to which Rubell added ‘That’s what I try to make it too, escapism.’ (Rubell, S ). During another interview hosted by David Susskind, when discussing the likes of Mick Jagger and other A-list celebrities, Rubell noted ‘They like to go up to the Balcony and watch the people dance.’ (1977). The paradox of the performer hunting out an environment in which they can shapeshift into the audience to observe is why I believe this venue is ideal. I want the audience to feel as though the characters depicted could be strolling amongst them

throughout the exhibition. That the casual environment will elicit an unravelling in the way we perceive and form relationships with images.

Chapter 1 – the duality between introspection and distraction

Introspection

James Baldwin’s Dictionary defined introspection as: ‘Attention on the part of an individual to his own mental states and the process, as they occur, with a view of knowing more about them.’ (The Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, 1934). To refine how I interpret this statement throughout this dissertation, I will compare how the two philosophers Willhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener oppose each other when explaining their philosophical theories on the subject (SimplyPhycology). Willhelm Wundt perceives introspection through the term ‘Apperception’- how we organise and make sense of our experiences. Wundt avoided reflection and during his conduction of tests, he would advise the subject to perceive the internal reflection to its simplest value and nothing more expanded from that core. Where Edward Titchener differs from this portrayal of introspection is through the belief that it allows for multiple and complex experiences with focus and value regarding the thoughts and feelings of the subject. When referring to introspection – regarding the contemporary art world, one that is open to and facilitates broad interpretation on a massive scale. It isn’t without surprise that I intend to utilise Titchener’s understanding of introspection: one that not only allows for intricate cognitive ideas but encourages that same complexity in thought This contradicts Wundt who actively criticised Titchener’s adaptation of the theory.

Through Titchener’s concept, we can speculate the innermost thoughts and emotions experienced by the viewer when engaging with the selected works. Simultaneously to this, I will analyse the introspection and absorption of the subjects represented in those same pieces. Introspection itself occurs unwillingly. But when depicting this state of mind, it must be a consideration of the artist. Curator Jeff Rosenheim states this elegantly in his discussion of introspection in THE MET’s series of connections ‘the artist has to let you in in some way, and when it happens, we can enter a space that’s generally hidden to us as viewers’. It is how artists can represent this subconscious behaviour externally in the presence of their subjects, or subject matter and how this affects our mentality that I am interested in exploring. This representation doesn’t have to be limited to conjuring an emotional response, ranging from abstract and absurd to

the simplistic borderline pretentious movements in the art world, the individual experience is so wide when we develop a relationship with a work that it extends beyond just emotional and sits within us.

Distraction

‘I can scan the subway car and know who is thinking about their emotional present tense, and who is distracted’ (Rosenheim, J). Rosenheim regards distraction as a separate headspace from that of introspection. ‘A distraction is something that turns your attention away from something you want to concentrate on.’ (Collins Dictionary). Distraction is a state of being pushed off our intended course, often to entertain a more pleasurable task to soothe an uncomfortable state of mind, or it can be one of initially intending to pursue an enjoyable exercise to procrastinate from more demanding matters Distractions can range from researching your case study references for an exhibition dissertation and having your attention grabbed by a buzzing notification from your phone to irrationally baking banana bread while ignoring a looming deadline. According to Rosenheim, we can perceive this condition of mentality on ‘one’s exterior form’, which links us back to Fried’s concepts of absorption ‘It was noted that a plethora of eighteenth-century French artists depicted people sometimes solitary, sometimes collective, in a state of wrapt concentration, so much so that they denied the very existence of the beholder as ‘the potential agent of distraction’ (Freid, M, ). Distraction regarding art can also be interpreted as a form of escapism, in the same nuance as introspection, artworks conjure thoughts. In this case, the images of which can be as unalike as Pieter Bruegel’s malformed depiction of The Fall of the Rebel Angels that could urge sentiments of religious context, to Lisa Frank’s Whimsical and often overstimulating depictions of starry-eyed animals which might summon feelings of childhood nostalgia and redirect the focus of the viewers mind to one of contemplation This choice is made by the audience member to interact with the work, forming an interconnected relationship with the images, and forcing the individual to develop a reformed perspective. This forces the individual to develop new views and in turn a reformed perspective. ‘In effect this suggests a ‘de-theatricalization’ of the relationship between the viewer and the protagonist or image. No longer performing before us, but

so engrossed in their actions that we can't help but try to peak over their shoulder.’ (Fried, M). Isn’t it apparent to perceive the duality of these two mental states? Are we not distracted when we engage with art? Are we observing the image in front of us when we project our perceptions upon it? Do the two cognitive behaviours of distraction and introspection overlap? Does the artist depict a subject of deep introspection or has the figure simply unfocused their vision to escape from their thoughts – and is this not an action of will, to protest one’s demons?

Heidegger’s Dasein

If we bring in Heidegger’s concept of Dasein – Essentially the human ‘being’ situated within the world, constantly moving with time through its existence, with an awareness of its inevitable end (Dasein Disclosed). Just as Dasein is inseparable from the task of pursuing meaning within the world, the audience is tasked with oscillating between introspection and distraction when in the presence of art. Drawing from Micheal Freid’s theories of absorption and theatricality, we can observe how some artworks draw the viewer into a state of deep concentration, as seen in his discussion of eighteenthcentury French painting. While others invite a more performative or outward focus that keeps the viewer conscious of their role as a beholder. In this dynamic, distraction often becomes the gateway to introspection, as the initial encounter with an artwork, perhaps in a distracted state, can lead to deeper personal reflection and self-awareness. Conversely, moments of introspection arguably also create a space for distraction, where the mind drifts and reinterprets the work in new ways. Ultimately, the line between passive observation and active engagement invites viewers into a dialogue with their thoughts and emotions, in turn, deepening their understanding of the work and themselves.

Chapter 2 – Curatorial Choices

Artists and their Artworks

Ten artists and thirty-three artworks, primarily from New York City and its surroundings, will be showcased at Studio 54. The dimmed lights of the exhibition and quiet ambience offer a contemplative escape from the overstimulation of the city.

Mock model of exhibition space.

Fig. 1 Ground floor.

Fig. 2 Mezzanine.

No. 1 Jeff Wall

Fig. 3 Mock placement of Artwork.

Fig. 4 Wall, J. A Woman with a covered tray (2003) [Transparency in lightbox, 164 x 208.5cm].

Fig. 5 Wall, J. A view from an apartment (2004-5) [Transparency in lightbox, 167 x 244cm].

Fig. 6 Wall, J. A Woman consulting a catalogue (2005) [Transparency in lightbox, 165.1 x 133cm].

Since Michael Fried's writings Influenced my brief and aided in curating this theoretical exhibition, I’ve decided to open with an artist who Fried references.

Jeff Wall is regarded for his perfectionism in cultivating conceptual techniques in photography. Working in his distinct large-scale lightbox displayed photographs. By depicting diverging representations, he questions the viewer's understanding of his works, creating uncertainty within the curation and authenticity of his images. In making A View from an Apartment (Fig. 4), Wall Rented an apartment for two years and cast a recently graduated female artist to furnish and live within the space (Why Photography Matters). After Wall was satisfied with the subject's acclimation to her settings, he began shooting, having her act out repetitive domestic tasks. A Woman with a Covered Tray (Fig. 6) and A Woman Consulting a Catalogue (Fig. 5) depict similar scenes. ‘Wall has sometimes referred to his photographs as ‘Near documentaries’. This suggests that they are depictions of what might have been.’ (M. Lewis). This documentation of these repetitive creatures guides us into a state of contemplation, one can’t help but ponder the comings and goings of these subjects. This immediately traps the viewer in a state of Dasien for the remainder of the exhibition.

No.2 Bruise Gilden

Fig. 7 Mock placement of Artwork.

Fig. 8 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C.

Fig. 11 Gilden, B. Untitled (1969-1986) [Gelatine silver print] Coney Island.

Fig. 10 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992 ) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C.

Fig. 9 Gilden, B. Untitled () [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C.

Fig. 9 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] N.Y.C.

Fig. 12 Gilden, B. Untitled (1992) [Gelatine silver print] Coney Island.

As a member of Magnum Photos, Gilden adopts a peculiar method when capturing his subjects. Armed with a Leica M (Typ. 240) and handheld flash, ‘Flash helps me visualise my feelings of the city. The energy, the stress, the anxiety’ (Gilden, B) he strolls the west side of the street hunting for what he calls ‘characters’ (Gilden. B). Once he has targeted his victim, Gilden leaps out in front of the individual, resulting in an untheatrical image. I believe authenticity in Gilden’s work is derived through his technique, though it lacks sensitivity, it captures the distraction on an individual's face. ‘What I see is, and what the viewer should see is a lot of people walking in the city are lost in thought, they're not paying attention.’ (Gilden, B). Placing the street photographs on the surrounding walls of the ground floor provides the chance for the viewer to reflect on the faces they would have been passing by moments before and how they would have blended into the backdrop of absorbed persons themselves, would they have been surprised if met with their face – would they recognise themselves?

No.3 Diane Arbus

Fig. 13 Mock placement of Artwork.

Fig. 14 Arbus, D. (1957) Lady on bus [Gelatine silver print, 21.6 × 14.6 cm] N.Y.C.

Fig. 16 Arbus, D. (1951) Female impersonator holding long gloves [Gelatine silver print, 24.8 × 14.9 cm] Hempstead, L.I.

Fig. 17 Arbus, D. (1961) Stripper with bare breasts sitting in her dressing room [Gelatine silver print, 24.1 × 16.5 cm] Atlantic City, N.J.,

Fig. 18 Arbus, D. (1961) Human Pincushion, Robert C. [Gelatine silver print, 24.7 x 16.3 cm] Harrison N.J.

Fig. 19 Arbus, D. (1961) Jack Dracula at the bar [Gelatine silver print, 24.9 × 17 cm] New London.

On the dance floor, I have decided to display several images from Daine Arbus’ collection – Daine Arbus in the beginning (1956-62). The collection was curated from MOMA’s archive, which her two daughters gifted after her suicide. Arbus has been criticised for her voyeuristic and exploitative images of curious individuals. Although, observing trusting stares and carefully thought-out framing of the subjects, I believe she opens our eyes to the weird and strange. ‘Arbus framed their images in ways that seem to enfold them in acceptance and potentially grotesque figures are sheltered in her compassionate gaze.’ (Naves, M) ‘What makes Arbus’ use of the frontal pose so arresting is that her subjects are often people one would not expect to surrender themselves… for the camera… Implies in the most vivid way the subject's cooperation.’ (S, Sontag). Seeing eye to eye with Arbus we can reflect on our bizarre qualities and begin to see ourselves within the images. Regarding the display of the works, I've chosen to reproduce the setting of the initial exhibition in New York’s Met Breuer, (2016) which I will discuss further on in this chapter.

No. 4 Nan Goldin

Fig. 20 Mock placement of Artwork.

Fig. 21 Golden, N. (1985) Nan on month after being battered [Slideshow] N.Y.C.

Fig. 22 Golden, N. (1980) Twisting at my birthday party [Slideshow] N.Y.C.

Fig. 23 Golden, N. (1979) Trixy on the cot [Slideshow] N.Y.C.

Projected on the main stage is Nan’s slideshow Collection, A Ballad of Sexual Dependency. The tenderness in Goldin’s work reflects the care she extended to herself and those closest to her. ‘(A Ballad…) Is the diary I let people read. My written diaries are private; they form a closed document of my world and allow me the distance to analyse it. My visual diary is public; it expands from its subjective basis with the input of other people. These pictures may be an invitation to my world, but they were taken so that I could see the people in them.’ (Goldin, N). This statement represents the vulnerability that Goldin offers and allows the world to judge. Diaristic photography is a language created by Goldin to aid her in understanding herself. ‘I want to show exactly what my world looks like, without glamorization, without glorification. This is not a bleak world but one in which there is an awareness of pain, a quality of introspection.’ (Goldin, N). Authenticity blooms from the profound affection in her documentation of her surroundings, inviting us into an underground world. It is a space populated by individuals navigating complex lives, including drug dependency, prejudice and the AIDS epidemic. In Fig. 21, Nan stares back at us with the blackened eyes inflicted by her abusive boyfriend. Her gaze challenges us to reconsider any judgments of her lifestyle—she remains honest, even in her brokenness. This arresting stare compels us to confront our own truths, drawn by the raw power of her credibility.

7. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency\ installation view in

Fig.

No. 5 Larry Clark

Fig. 24 Mock placement of Larry Clark’s Artwork.

Fig. 25 Clark, L. (1971)Untitled, from the series Tulsa [Gelatine silver print].

Fig. 26 Clark, L. (1971) Untitled, from the series Tulsa [Gelatine silver print].

The two images I’ve selected from Larry Clark’s Tulsa (1971) are of compelling origin. Parallel to Nan Goldin’s work, Clark’s photographs embody diaristic storytelling. These images offer a raw glimpse into his everyday life during his early substance use, making them a challenge to view yet deeply intimate. Like Goldin, Clark employs participant observation, inviting us to enter an insider's world. His use of a large aperture and low light lends a glowing, atmospheric quality to these intensely moody images, enhancing their emotional resonance. The depiction of a pregnant figure (Fig.26) encapsulates the link between distraction and addiction. It challenges our instinct to condemn such behaviour, yet through Clark’s sympathetic lens—perhaps shaped by his close relationship with the subject we are compelled to reflect on our own crutches, even when they harm those around us.

No. 6 Cindy Sherman

Fig. 27 Mock placement of Cindy Sherman’s Artwork.

Fig. 29 Sherman, C (1978) Untitled Film Still #17 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

Fig. 28 Sherman, C (1977) Untitled Film Still #05 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

Fig. 32 Sherman, C (1978) Untitled Film Still #21 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

Fig. 31 Sherman, C (1977) Untitled Film Still #03 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

Fig. 30 Sherman, C (1978) Untitled Film Still #07 [Gelatine silver print 19.1 × 24 cm].

In Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, we see Michael Fried’s concept of theatricality brought to life. ‘All Sherman’s personas… project the constructed idea of the woman’s image, the arbitrariness of the female stereotype’ (Artlead). Her work explores the subconscious performance of femininity: ‘A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself.’ (Ways of Seeing).

Through this performative lens, Sherman convinces us that we know her characters, aided by the ‘ambiguity’ (Sherman, C) of her titles she draws viewers into a deliberate trap.

By manipulating perceptions, Sherman capitalizes on the social tendency to form imagined relationships with celebrities, a phenomenon tied to our fascination with the big screen. Our voyeurism is laid bare, and our infatuation with movie stars reflects a psychological instinct to find aspects of ourselves in carefully curated celebrity personas. To enhance this connection, Sherman’s images are mounted on the backs of theatre seating structures, mimicking the cinematic experience and immersing viewers in the performative nature of her work.

No. 7 Alex Prager

Fig. 34 Second mock placement of Alex Prager’s Artwork.

Fig. 33 Mock placement of Alex Prager’s Artwork.

Fig. 35 Pragre, A. (2013) Face in The Crowd - Crowd #4 New Haven [59.5 x 75 inches]

Fig 36 Pragre, A (2013) Face in The Crowd - Crowd #3 (Pelican Beach) [59 x 92.85 inches].

Like Sherman, the next work viewers encounter is Alex Prager’s Face in the Crowd (2013). Both artists share a cinematic sensibility, infusing their work with elements of humour and heightened style. Prager employs bright colours and a nostalgic aesthetic reminiscent of Hollywood’s golden era. She conceived these images in response to her growing phobia of large gatherings, aiming to evoke an emotional reaction to their surreal, plasticlike quality. In an interview with Paris Photo Prager notes ‘Looking at a picture I’ve made, if I don’t feel some kind of emotion from it, for me, it’s not worth putting out into the world.’ (Prager, A).

“Made” is no understatement Prager meticulously curates every detail, from scale and costuming to the unique personalities of each model. This attention to detail allows her to capture the overwhelming sense of being surrounded by countless individual experiences and secrets. Her work invites viewers to reflect on the vulnerability and self-awareness that emerge when lost in a crowd, fostering a personal connection to the collective humanity she portrays.

No. 8 Phillip Lorca DiCorcia

Fig. 39 Lorca DiCorcia, P. Marilyn; 28 years old (199092)[Chromogenic print] Las Vegas, Nevada.

Fig. 37 Mock placement of Phillip Lorca DiCorcia’s Artwork.

Fig. 38 Lorca DiCorcia, P. Marco (1978) [Chromogenic print] N.Y.C

On the wall adjacent to the stage, I have selected two works from different periods of Philip-Lorca DiCorcia's career. Marco (1978) features DiCorcia's brother and marks the beginning of his photographic journey, while Marilyn comes from his first series, Hustlers. In both images, the settings and lighting are precisely staged. In Marco, a flash is synchronized to go off simultaneously with the exposure, while in Marilyn, the model was hired from the streets of Santa Monica to pose and share information about herself.

Each of DiCorcia’s photographs engages the viewer in a narrative that is ‘wrapped in the shimmering package of consumer culture’ (Galassi, P). ‘The inwardness of DiCorcia’s characters is often not mere reverie but something graver, which opens to us the inward depths of our own lives.’ (Galassi, P) DiCorcia expertly navigates the intersection of distraction and introspection through his glossy media, allowing the polished images to contrast against the rugged

No. 9 Sophie Calle

Fig. 40 Mock placement of Sophie Calle’s Artwork.

Fig. 41 Second mock placement of Sophie Calle’s Artwork.

Fig. 42 Calle, S. (1979) Gloria K., second sleeper.[Gelatine silver prints 12.6 x 18.4cm].

Fig. 43 Calle, S. (1979) Gloria K., second sleeper.[Gelatine silver prints 12.6 x 18.4cm].

Fig. 44 Calle, S. (1979) Gloria K., second sleeper.[Gelatine silver prints 12.6 x 18.4cm].

Sophie Calle's The Sleepers (1979) is a thought-provoking exploration of intimacy, vulnerability, and surveillance. Through her invitation to strangers to rest in her bed, Calle creates a setting where human connection is stripped of pretence. The interactions preparing breakfast, questioning the participants, documenting their states establish a fragile yet sincere connection. The act of recording these moments, complemented by her handwritten observations, lends the work a deeply personal texture. In Fig. 42, ‘Gloria K. Sunday 1979, 5:30pm. She is not sleeping,’ (Los Dormeurs) Calle captures a moment of exception a subject conscious and perhaps resisting complete vulnerability. This contrasts with the broader theme of unconsciousness that permeates the series. Calle's quiet spectatorship, combined with her decision to document rather than direct, allows her subjects to exist in an untheatrical, unrehearsed state, emphasizing authenticity. The series poignantly critiques the omnipresent surveillance in society, highlighting the pressure to perform and justify oneself in daily life. By juxtaposing this with the raw and unguarded nature of sleep, Calle offers a meditation on freedom where, in sleep, the individual momentarily escapes societal scrutiny and the need to maintain a facade. This tension between vulnerability and spectatorship challenges the viewer to consider their own relationship with privacy and the gaze of others.

No. 10 Lee Friedlander

Fig. 45 Mock placement of Lee Friedlander’s Artwork.

Fig. 46 Friedlander, L. Shadow (1966) [Gelatine silver print 16.0 x 24.1 cm] N.Y.C.

Fig. 48 Friedlander, L. Maria (1966) [Gelatine silver print 27.9 x 35.6cm] Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Fig. 47 Friedlander, L. Tallahassee, Florida (1934) [Gelatine silver print].

Ultimately, the exhibition concludes with three works by Lee Friedlander, renowned for his inventive self-portraits using the interplay of his shadow. Friedlander's images often provoke mixed responses; some, such as Jeffrey in Photography: A Concise History, describe them as ‘hard to read’ (Jeffrey, I). However, these compositions are celebrated for their subtlety and depth. Friedlander’s use of his shadow, a recurring motif in his work, serves as an understated acknowledgement of the photographer's presence behind the lens. Art critic Michael Fried has interpreted this technique as a solution to the overly performative tendencies of photographers, allowing Friedlander to engage in a quieter, more introspective form of self-representation. By incorporating his shadow into the frame, Friedlander achieves a layered commentary on the act of image-making itself, blurring the lines between subject, observer, and performer. Through these works, Friedlander invites viewers to contemplate the photographer's role not as a detached observer but as an integral presence within the composition. This reflective approach adds a thoughtful dimension to the exhibition’s exploration of surveillance, intimacy, and the boundaries of performance.

Curational Decisions

Slight modifications were made to the venue's original blueprint to enhance the viewing experience and ensure an optimal flow throughout the space. These changes included removing seating and temporary walls and installing lightboxes and other display elements. These adjustments were carefully considered to create an environment that prioritizes both the quality of the exhibition and the seamless movement of visitors.

The design of the exhibition fosters a profound connection between the viewer and the artwork. The displayed images serve as mirrors, reflecting the audience and positioning them as part of the larger artistic narrative within the space. Inspired by Michael Fried’s concepts of absorption and theatricality, the curation aims to ‘make the viewer become aware of his or her responsibility in what he or she is looking at’ (Berrebi, S)

Beyond encouraging introspection, the exhibition challenges viewers to reconsider their perception of photography and its expansive possibilities. As Lee Friedlander observes:

‘I only wanted Uncle Vern standing by his new car on a clear day. I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on a fence, and a row of potted begonias on the porch and seventy-eight trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.’ (Friedlander, L).

This reflection underscores the duality within photography: the meticulous curation of a scene versus the organic unfolding of subject matter. The exhibition highlights both approaches, illustrating how each relies on the photographer’s discerning eye to capture something meaningful, capable of representation and connection.

When entering the exhibition, you meet with three of 1. Jeff Walls Lightboxes. The brightness of the back-lit images creates a stark contrast against the dim surrounding interior. Wall’s depictions are that of the painstaking creation, as previously explained. In A View from an Apartment, Fried links the artwork with Heidegger’s ontology of Desen as ‘A View is uncontestably a picture…, which presumably would invalidate it as a work of poetic revealing in Heidegger’s understanding of the concept.’ (Fried, M) Fried

explains that Heidegger would find Wall’s photography distasteful and banal to his concepts. However, Fried expands upon this regarding Heidegger’s writings in The Question Concerning Technology when discussing Wall’s work ‘like all his (Wall’s) photographs, lightbox or otherwise – (it’s) technological at its core.’. I believe ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ (Fried, M) and related texts provide a uniquely productive basis for engaging with Wall’s long-plotted, artfully constructed, yet also mysterious and lyrical tableau’. Though initially Desen is thought to be unconnected to Wall’s lightboxes, we can see through other theories by Heidegger that Wall represents a current depiction of being, one that the present population can engage with.

To engage more deeply with 2. Bruce Gilden’s work, it is essential to examine his methodology. As Philip notes, ‘The street does not induce people to shed their selfawareness. They seem to withdraw into themselves. They become less aware of their surroundings, seeming lost in themselves. Their image is the outward-facing front belied by the inwardly glazing eyes’ (DiCorcia, P). Gilden’s distinctive practice, often regarded as candid photography, captures this introspection moments when passers-by appear absorbed in their thoughts, detached from their surroundings. Susan Sontag echoes this sentiment: ‘There is something that appears on faces when they don’t know they are being observed that never appears when they do’ (On Photography). Through his occasionally blurry, overexposed photographs, Gilden reveals a raw and unfiltered view of New York City—a bustling, chaotic, and unpolished environment. His rough, striking images invite us to explore the connection between distraction and introspection, offering a glimpse into the private, inward moments of the city’s inhabitants amidst its frenetic energy.

The most prominent curatorial decision was to replicate the ambience of 3. Diane Arbus’s In the Beginning exhibition which was first displayed in 2016 at New York’s Met Breuer. Curated by Jeff Rosenheim, this original exhibition arranged its images as ‘small prints without glass or frame, warmly lit, and mounted on narrow, free-floating, fabriccovered panels that stretched between the ceiling and floor.’ (Horwitz, W). This approach created an intimate, small-scale format that, coupled with tightly designed

spaces, compelled viewers to engage closely with the works, evoking ‘both interest and discomfort’ (Horwitz, W).

To further enhance the atmosphere, I incorporated Lauren Mroczkowski’s lighting techniques, chosen for their ability to deepen the space's visual and emotional resonance. This lighting complements the structural design and draws out the intricacies of the works, emphasising their depth and inviting a more personal introspective viewing experience.

4. Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is partially visible throughout the exhibition, its glowing projection seen from both the ground floor and the mezzanine. Accompanied by Loaded (1970) by The Velvet Underground, the soundtrack pays homage to the original screenings of her work, echoing through the space. This immersive presentation challenges viewers to confront the tension between public and private life. Goldin’s unflinching portrayal of addiction, abuse, love, and loss compels introspection, questioning boundaries and the ethics of observation. The interplay of imagery and music fosters both intimacy and discomfort, urging viewers to reflect on their own notions of privacy and vulnerability.

5. Larry Clark’s Tulsa series is intentionally set apart as the first images encountered in the exhibition, creating a sense of privacy for viewers. Due to the potentially triggering nature of these diaristic-style photographs, they are displayed in a quiet, secluded area with appropriate content warnings provided beforehand. This thoughtful arrangement minimizes potential distress while offering those prepared to engage a focused and intimate environment. Here, viewers can fully immerse themselves in Clark’s raw depiction of his early days of escapism, allowing the photographs to resonate deeply without distraction.

Another artist that can be analysed though Freid is 6. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled film stills. ‘In most of the Stills Sherman depicts characters who appear absorbed in

thought or feeling.’ (Freid, M, p. 7) While Sherman performs for the camera, she projects characters who seem lost in distraction, embodying a sense of introspection. ‘In Sherman’s Stills, as seen, this is accomplished in part through motifs of absorption and distraction.’ (Freid, M. p. 13) These elements allow Sherman to tap into the viewer’s intrusive desire to understand her characters, drawing attention to the overlap of escapism inherent in theatre. Through this interplay, Sherman masterfully captures the duality of introspection and distraction, creating a powerful tension that resonates with the audience.

I’ve chosen to mount these images on the back of structures resembling theatre seating, echoing Studio 54's original design. This design decision not only pays homage to the venue’s history but also reflects the audience experience which celebrities sought as escape through the distractions of Studio 54’s nightlife. It serves as a visual reminder of the complex interplay between fame, voyeurism, and the desire for anonymity.

On opposite sides of the mezzanine walls is 7. Alex Prager’s In the Crowd, sandwiching the viewer between the works and recreating the claustrophobic atmosphere that inspired the photographs. This deliberate placement amplifies the sensation of being engulfed in a dense crowd, mirroring the tension and emotional weight present in Prager’s imagery. The empathy evoked by Prager’s photographs fosters a profound connection between the viewer and the artwork. These images draw out a unique form of introspection, often described as sonder the ineffable realization of being linked to the countless lives that intersect with our own, each carrying their own complex experiences. Prager’s work compels us to pause and contemplate these shared yet individual narratives, deepening our understanding of collective humanity.

8. Philip-Lorca DiCorcia’s ‘photographic voice and his distinctive photographic style’ (Galassi, p. 249) are central to discussions in Michael Fried’s Why Photography Matters In reference to Mario, Fried notes, ‘Our first impression is that the man standing before the open refrigerator door is absorbed in what he is doing… yet as with Wall’s

transparency… or indeed Sherman’s Untitled Stills of roughly the same time, an instant’s reflection suffices to rule out the possibility that Mario is a candid photograph’ (Fried, M. p. 24). Despite the undeniable staged quality of DiCorcia’s work, he masterfully captures a profound sense of inwardness.

‘It is a striking fact about those works that they do so by flirting with or at least alluding to the idea of absorption and/or reverie and the absorptive ideal of the subject's obliviousness to being beheld as if their stagedness, their to-be-seenness, was given added point, made all the more self-evident, by virtue of that fact’ (Fried, M. p. 252).

This tension is also evident in DiCorcia’s Street work series shot in Santa Monica. Without context, the glazed expressions of the sex workers he photographs reflect the disconnection and lack of self they offer to clients. This dynamic raises questions about exploitation, suggesting that DiCorcia himself might be complicit in the objectification he captures, placing his work in a complex dialogue about gaze, power, and the ethics of representation.

When justifying the inclusion of 9. Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers, I draw upon Michael Fried’s writings on the representation of blind subjects and their unique capacity to embody absorption. In Absorption and Theatricality, Fried remarks on the prominence of blindness in post-1750 French painting, suggesting that its significance arises from the ability to depict blind individuals as ‘unaware of being beheld.’ (Fried, M P 69-70

Fried later observes, ‘Blindness is also the subject of one of the most powerful and influential photographs of the early twentieth century, Paul Strand’s Blind, as an evocation of blindness as experienced from within.’ (Fried, M. p. 93).

This connection resonates with Calle’s work, as the unconscious state of sleep shares parallels with the inward experience of blindness. Both conditions signify an absorbed state of being, derived entirely from within. Calle’s The Sleepers captures her subjects in this duality distracted and unaware when asleep, yet introspective and engaged when awake, as they respond to her probing questions. Through this interaction, Calle bridges the gap between the unconscious and the conscious, creating a compelling dialogue about presence and absorption.

10. Lee Friedlander’s self-portraits cleverly manipulate the camera’s unpredictable nature, using his shadow to reflect the viewer’s participation back at themselves. This approach, both ingenious and deceptively simple, transforms the act of photography into a tool for questioning introspection and self-awareness. By embedding himself into the frame, Friedlander blurs the line between observer and subject, inviting viewers to confront their own role in the act of seeing.

Chapter 3 - Curational Aims

Venue

Refer to Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 to review the exhibition space.

The exhibition will be hosted at Studio 54, New York City a venue steeped in creative history and cultural ties to escapism. This location embodies the exhibition’s themes, offering a space that bridges artistic expression and the pursuit of freedom from societal constraints.

New York City itself plays a vital role in this curatorial decision. As a historical hub for revolutionary art movements, the city has long been a haven for those pushing the boundaries of photography. Many of the artists featured in the exhibition, including Lee Friedlander, Cindy Sherman, Bruce Gilden, Alex Prager, and Nan Goldin, have deep connections to the city. Its vibrant population of photographers, both past and present, ensures a strong resonance with an image-focused exhibition. Moreover, New York’s unique character mirrors the duality at the heart of the exhibition: a place of bustling distraction and ceaseless activity, yet also one where individuals seek moments of introspection amidst the chaos. This dynamic further reinforces the themes of the show, inviting viewers to engage deeply with both the artworks and their own experiences within the space.

Intended Audience

While the audience's age will be regulated, all other subjective qualities are intended to be self-supervised. The exhibition is designed to be broadly accessible, with content warnings placed before specific images to encourage participants to practice mindfulness regarding their own potential reactions. This approach ensures a respectful and inclusive environment while allowing viewers to engage with the works at their discretion. Though the exhibition targets those who regularly engage with photography, the audience does not need to have a pre-disposed interest in the medium.

‘The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera’ (Lange, D)

This sentiment reflects the exhibition’s core objective: to use photography as a tool to shift the viewer's perspective and approach to a body of work. The images invite audiences to explore new ways of seeing and interpreting, challenging preconceived notions about photography and its emotional and intellectual impact. However, the success of this exhibition relies on the openness of its viewers. Without their willingness to expand their understanding and engage with the medium, the exhibition’s aims risk falling short.

Conclusion

This dissertation has sought to explore the duality of introspection and distraction as depicted in contemporary photography and how these opposing states influence the relationship between the viewer and the artwork. By curating a theoretical exhibition in Studio 54, a venue historically associated with escapism and voyeurism, the study has examined how photography navigates the boundaries between private and public, intimacy and spectacle. Through this investigation, the exhibition highlights photography’s power as a medium to evoke emotional responses, challenge societal norms, and inspire self-reflection.

At the heart of this exploration lies Michael Fried’s concepts of absorption and theatricality, which serve as a theoretical framework for analysing the selected artworks. Fried’s ideas highlight how certain images immerse viewers in a deeply personal engagement with the subject while others emphasise their role as observers, drawing attention to the constructed nature of the photographic medium. These notions are particularly relevant to the works of Nan Goldin and Larry Clark, whose diaristic approaches compel viewers to confront their own boundaries between observation and participation. Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency exemplifies this tension, as her raw portrayal of addiction, abuse, and love invites empathy while also challenging voyeuristic tendencies. Similarly, Clark’s Tulsa series provides an unflinching look at his early life of substance use, creating moments of discomfort and connection that resonate with viewers’ own vulnerabilities.

The exhibition further examines how distraction and introspection are mediated through photography by incorporating works that juxtapose the constructed and the candid. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills manipulate the viewer’s perceptions by presenting carefully staged personas that evoke familiarity yet remain ambiguous. This deliberate ambiguity forces the audience to sway between projecting their own narratives onto the images and recognising the theatricality inherent in Sherman’s work. This interplay between the authentic and the performative mirrors the broader theme of distraction

and introspection, highlighting how photography exists at the intersection of these mental states.

Alex Prager’s Face in the Crowd series expands on this theme by recreating the overwhelming sensation of being lost in a crowd. Prager’s meticulous attention to detail, combined with her cinematic aesthetic, draws viewers into a world that feels simultaneously real and surreal. By positioning these works on opposite walls of the mezzanine, the exhibition immerses the audience in a claustrophobic environment that mirrors the emotional weight of Prager’s images. The empathy elicited through her work encourages viewers to reflect on the shared humanity of those around them, blurring the line between personal introspection and outward connection.

The exhibition’s location, Studio 54, adds another layer to this exploration. The venue’s history as a hub for escapism, performance, and observation aligns with the themes of distraction and introspection. It provides a space that bridges the personal and the collective, inviting audiences to reflect on their own relationship with these states of mind. Studio 54’s dual identity as a space for celebrity voyeurism and personal anonymity underscores the dynamic interplay between the public and private, mirroring the tension found in the exhibited works.

Curatorial decisions also played a significant role in shaping the exhibition’s impact. Content warnings and secluded displays for sensitive works, such as Clark’s Tulsa series, ensure an inclusive environment that respects individual boundaries. The decision to partially reveal Goldin’s slideshow throughout the venue invites viewers to engage with her work in fragments, echoing the fragmented nature of memory and experience. Similarly, the replication of theatrical seating for Sherman’s photographs enhances the cinematic quality of her work, fostering a deeper connection between the viewer and the medium.

While the exhibition targets photography enthusiasts, it remains accessible to a broader audience. As Dorothea Lange aptly stated, ‘The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.’ (Lange, D). This sentiment reflects the exhibition’s

aim to use photography as a tool for shifting perspectives, encouraging viewers to see beyond the immediate image and engage with the emotional and intellectual layers embedded within. However, the success of this endeavour ultimately depends on the openness of the audience to embrace new ways of seeing and interpreting. Without this willingness, the exhibition risks falling short of its potential to foster meaningful connections and insights.

The dissertation also highlights the ethical implications of photography as a medium, particularly in its ability to capture moments of vulnerability and marginalization. Artists like Sophie Calle and Philip-Lorca diCorcia navigate these complexities by presenting works that challenge notions of power, gaze, and representation. Calle’s The Sleepers and DiCorcia’s Hustler’s series confront the ethics of observation, urging viewers to question their own complicity in acts of voyeurism. These works highlight photography’s dual capacity to document and distort, to reveal and obscure, creating a space for critical reflection on its role in shaping societal narratives.

In conclusion, this exhibition exemplifies photography’s unique ability to bridge the duality of introspection and distraction, offering a medium through which viewers can explore their own emotional and intellectual landscapes. By curating works that range from the diaristic to the performative, the exhibition challenges traditional notions of viewership and encourages a deeper engagement with the medium. Through its thoughtful integration of curatorial strategies, theoretical frameworks, and diverse artistic perspectives, the exhibition not only celebrates photography’s potential as an art form but also its capacity to connect individuals to themselves, each other, and the world around them. Ultimately, this study reaffirms photography’s enduring relevance in a contemporary context, as both a tool for personal exploration and a catalyst for collective understanding.

Bibliography

Araujo, S. de F. (2016) Wundt and the Philosophical Foundations of Psychology A Reappraisal. 1st ed. 2016. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024].

Baldwin, J, M. (1918) The Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology. New York: Macmillan Co.

[Accessed: 5 Nov. 2024]

Berger, J. (2008) Ways of seeing. London: Penguin. P. 45.

[Accessed 15 Dec 2024]

Berrebi, S. Jean-Marc Bustamante: ‘Its Crap but in the Right Way’ interview. Available at: http://eyestorm.com/feature/ED2narticle.asp?article_id=140

[Access unavailable]

Bussard, K. and Dorin, L. (2008) ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’, Museum studies (Chicago, Ill.), 34(1), pp. 72–96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/20205594.

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024].

Bustamante, M. (2008) Why photography matters as art as never before. New Haven: Yale University Press, p20.

[Accessed: 27 Oct. 2024].

Calle, S. (2000) Les dormeurs. Nimes: Editions Actes Sud. P. 12.

[Accessed 05 Dec. 2024]

Collins Dictionary. Distraction Available at: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/distraction

[Accessed: 15 Nov. 2024]

Curtis, A. (2019). Art History Society. [online] Art History Society. Available at: https://arthistorysociety.org/essays/the-theatricality-of-the-everyday

[Accessed 7 Nov. 2024].

DiCorcia, P (2003) The storybook of life. Santa Fe, N.M, p. 5.

[Accessed 08 Dec. 2024]

Fried, M. (2008) Why photography matters as art as never before. New Haven: Yale University Press. P. 7, 13, 24, 62, 65, 93, 252, 355.

[Accessed 07 Dec. 2024]

Fried, M. Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980), p. 69-70 and p. 156

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024]

Friedlander, L. An Excess of Fact, in The Desert Seen, New York, 2005, p. 14.

[Accessed 7 Nov. 2024].

Galassi, P. Phillip-Lorca DiCorcia (Museum of Modern Art New York, 1995) p. 5, 11. [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024]

Goldin, N. and Goldin, N. (2012) The ballad of sexual dependency. [New edition]. Edited by M. Heiferman et al. New York: Aperture. P. 12, 35.

[Accessed 25 Nov. 2024]

Haugeland, J. and Rouse, J. (2013) Dasein disclosed: John Haugeland’s Heidegger. 1st ed. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674074590

[Accessed 15 Nov. 2024]

Historic Films Stock Footage Arc (2024) 1979 INTERVIEW WITH STUDIO 54 DISCO

OWNER STEVE RUBELL. Available at: DOI or name of streaming service/app or URL

[Accessed: 31 Oct. 2024]

Horwitz, W. (2017) ‘Diane Arbus: In the Beginning’, Afterimage, 44(4), pp. 36–37.

[Accessed 27 Oct 2024]

Irish, A. (2020). The Artistic and Cultural Legacy of Studio 54. [online] Art & Object. Available at: https://www.artandobject.com/articles/artistic-and-cultural-legacystudio-54.

[Accessed: 27 Oct. 2024].

Jeffrey, I. (1981) Photography a concise history. Thames and Hudson. p. 216.

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024]

Latta, R. (1902) ‘Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, etc. James Mark Baldwin’, International Journal of Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, etc, pp. 114–121. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/intejethi.13.1.2376246.

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2021].

Lopez-Garrido, G. (2023) What is Structuralism in phycology? Available at: https://www.simplypsychology.org/structuralism.html.

[Accessed: 5 Nov. 2024]

M, Lewis. (2009) Jeff Wall : the complete edition. London: Phaidon. P. 34.

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024].

Meltzer, M. (2000) Dorothea Lange : a photographer’s life. Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press. P. 7.

[Accessed 15 Oct. 2024]

Modern Classics: Cindy Sherman – Untitled Film Stills, 1977-1980 Available at: https://artlead.net/journal/modern-classics-cindy-sherman-untitled-film-stills/.

[Accessed: 17 Dec 2024]

nalonso68jackson (2024) Michael Jackson Studio 54 interview 1977 sub-Spanish. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDhsf5NFT9c.

[Accessed: 31 Oct. 2024]

Naves, M. (2016) ‘Diane Arbus: in the beginning’, The New criterion (New York, N.Y.), pp. 84–85.

[Accessed 7 Nov. 2024].

Paris Photos. (2019) ALEX PRAGER – Interview 2019. 27 Apr. 2020. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dIsfiptvREk&t=184s

[Accessed 30 Nov. 2024]

Romeyn, K. (2018). Studio 54’s Paradigm-Shifting Design. [online] Architectural Digest. Available at: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/studio-54-documentarydesign.

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024].

Rosenhiem, J. Introspection/ Connections [Podcast]. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/connections/introspection/index.html#/Feature/.

[Accessed: 15 Nov. 2024]

Sherman, C. and Frankel, D. (2003) Cindy Sherman : the complete untitled film stills. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. P. 11.

[Accessed 15 Dec 2024]

Sontag, S. (1977) On photography. London: Penguin. P. 37, 50.

[Accessed 08 Dec. 2024]

Sontag, S. (2003) Regarding the pain of others. London: Hamish Hamilton, p. 31.

[Accessed: 27 Oct. 2024]

Titchener, E.B. (no date) A Beginner’s Psychology. Project Gutenberg

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2024].

WNYC (2008) WNYC Street Shots: Bruce Gilden. May 15, 2008. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kkIWW6vwrvM&list=WL&index=62.

[Accessed: 25 Nov. 2024].