Title: It's Shite Being Scottish:An Exploration of Glasgow culture and identity through the lens of Glaswegian artists and Scottish Pop culture.

Author: Keira McGuire

Publication Year/Date: May 2024

Document Version: Fine Art Hons dissertation

License: CC-BY-NC-ND

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/bync-nd/4.0/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20933/100001303

Take down policy: If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.

1 Table of Contents Page No. Title Page…….................................................................................................................................................. 1 Abstract............................................................................................................................................................ 3 List of Illustrations.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 – VisualArts Simon Murphy.................................................................................................................................................... 8 Trackie McLeod 10 Ashley Rawson.................................................................................................................................................. 13 Chapter 2 - Music, Subculture and Pop Culture Johnny Madden (Baby Strange) ....................................................................................................................... 17 Billy Connolly ................................................................................................................................................. 21 Chapter 3 - Literature GraemeArmstrong.............................................................................................................................................. 24 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 27 References.......................................................................................................................................................... 29 Appendices.......................................................................................................................................................... 31

ABSTRACT

The inspiration for my dissertation sprouted from my personal interest in exploring my cultural identity and gaining a deeper understanding of my native city, Glasgow. Through this dissertation, I delve into the unique quirks of Glasgow, the charming personalities of its people, and its working-class identity. To achieve this, I analyse different works created by Glaswegian artists across various mediums such as visual art, music, pop culture, subcultures, and literature. These mediums serve as lenses through which I investigate the various elements that contribute to shaping the Glaswegian experience.

In addition to analysing different works of art, I conducted research interviews with a few Glaswegian artists to gain a better understanding of their creative work and personal perspectives. Their insights offer a unique perspective into their own Glaswegian narratives, providing a rich understanding of Glasgow's cultural landscape. I aim to understand what factors contribute to the unique Glaswegian experience, from the perspective of those who create work exploring their own Glaswegian identity.

I have posed the question to the artists I interviewed, asking them if it really is, in the words of Trainspotting's Renton, "shite being Scottish"? Through this question, I hope to explore the challenges that Glaswegian artists face in their creative work, and how their experiences shape their perception of Glasgow's cultural identity. By combining my analysis of various works of art and the insights of Glaswegian artists, my dissertation aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the Glaswegian experience, its challenges, and its beauty.

2

3

Figures Page Introduction Fig. 0.1 : Glasgow’s Miles Better Campaign M8 (1983) 7 Fig. 0.2 : People Make Glasgow (2013) 7 Chapter 1 Fig 1.1 : Simon Murphy – Govanhill (2023) 8 Fig 1.2 : Simon Murphy – Govanhill (2023) 8 Fig 1.3 : National Records of Scotland - Percentage of children in relative low 9 income families graph (2021-22) Fig 1.4 : Trackie Mcleod – Did ThisArtwork Just Solve Sectarianism? (2021) 12 Fig 1.5 :Ashley Rawson – Glasgow Kiss 13 Fig 1.6 :Ashley Rawson – Too Wide 16 Fig 1.7 :Ashley Rawson – CommunityArts Project 16 Fig 1.8:Ashley Rawson – Donald’s Coronation 16

2.1 : Baby Strange – Photographed by Marilena Vlachopoulou (2020) 17 Fig 2.2 : National Records of Scotland - Drug misuse deaths for selected council 19 areas age standardised death rate 2018-2022 graph (2023) Fig 2.2 : Baby Strange – Viewpoint (2019) 20 Fig 2.3 : Edmund Smith – Billy Connolly’s Big Banana Feet (1975) 21 Fig 2.4

Billy

Feet worn on stage

22

GraemeArmstrong – The Young Team Book Cover

25

List of Illustrations

Chapter 2 Fig

:

Connolly - Billy Connolly’s Big Banana

(1975)

Chapter 3 Fig 3.1 :

(2020)

INTRODUCTION

What does it mean to be Glaswegian? This is a question that, as I’ve got older, I have found myself contemplating more frequently.As we progress and evolve, it's only natural to examine our sense of self and reflect on our origins.

Growing up in the East End of Glasgow, I wholeheartedly embrace the essence of the working-class city, or to put it in Scottish terms, embracing the ‘shiteness’. I cherish the childhood memories of buying pirate CDs from The Barras market on a Sunday morning, the traditional and unpretentious pubs filled with dedicated locals, groups of suspicious-looking young boys lingering outside off-license shops sporting the unspoken uniform of full nylon tracksuits and skip caps, and the ever-present humble humour that infiltrates Glasgow’s public art, traditions, and the spirit of the people themselves. These feelings and attitudes towards the city are not unique to my own. They instead are a shared sentiment among many Glaswegians providing us with a uniquely grounding perspective on both the hardships and simple joys in life.

I’ve always been very proud of being Scottish, but over the recent years my connection to my hometown, Glasgow, has grown more apparent.At 8 years old, my family moved to Dalian, China, and though I’ve always valued the experience, it's only in the past few years that I’ve truly recognised the deep impact it has had on my outlook on life. During my time spent in Dalian, I studied at anAmerican International school. Outside of the mandatory education, the school’s curriculum was very much centred around NorthAmerican history and geography.As the only Scottish person in the school, I refused to speak to my friends and teachers in a Scottish accent as I wanted to fit in American culture and media was always a very prominently idolised part of my childhood through the likes of Disney Channel etc. Consequently, I had abandoned my Scottish identity during this period, in favour of what I perceived as a more culturally appealing identity. Simultaneously, outside of school I had the unique opportunity of experiencing Chinese culture first-hand. In turn, I was eye-opening emersed in both Chinese andAmerican culture from such a young age. Thus, a newfound connection to my hometown was formed, and a profound appreciation for the comforts of home, like the simplicity of a roll and square sausage.

4

Although my experience is quite unique, studies show that many Glaswegian citizens also harbour this profound patriotic bond towards their home city. In a study by Natalie Braber, the concept of local versus national identities (Scottish/British) of Glaswegian people was examined to see which one they resonate with most. During this study, participants' attitudes towards the multiple cultural identities available to them, and what it means to be Glaswegian was also questioned. An important takeaway from the study is that none of the participants living in Glasgow made mention of identifying as British (Braber, 2009). Studies carried out by McCrone (1992), Bond (2000), and Rosie and Bond (2003) found that a Scottish identity was widespread with a sense of Scottish identity being more important than British identity. Some participants were more likely to identify as both Glaswegian and Scottish, with their Scottish heritage being equally as important to them as the city they grew up. Whereas, more working-class participants were more likely to classify themselves as Glaswegian and go into further detail about their local identity and what area they were raised in (ie. East End, South Side). Furthermore, 75% of the participants had positive feelings about Glasgow and referred to the friendliness and humour of the locals. Although there were 25% that expressed negative feelings about Glasgow’s bad reputation, most participants who did so stated they would still say they were from Glasgow if asked by a stranger. Two individuals expressed the importance of mentioning their Glaswegian identity as they desire to distinguish themselves from individuals from other Scottish cities. This demonstrates that a sense of locality can be associated with a negative sentiment towards others. One participant expressed their favour to Glasgow over Edinburgh stating “I don’t like Edinburgh, ‘cos I find them cold, you know, face like a pub carpet.” It is crucial to recognise that the viewpoint of this specific individual may not accurately reflect the opinions of the general public or all facets of the city.Although this participant may prefer Glasgow, it's essential to assess such assertions while keeping in mind their subjectivity and the possibility of overgeneralisation.

So from where do such profound sentiments of patriotism and communal pride within the people of Glasgow emanate? It's necessary to acknowledge the working-class history of Glasgow. The current situation within Britain is arguably problematic as Britain is a state made up of smaller nations, one of which being Scotland. Scotland has faced cultural and political dominance from England since TheAct of Union in 1707, marking the end of Scottish Independence as it joined with England (Braber, 2009). This led to misconceptions regarding the differences between Britain, England, and Scotland, not only among the

5

English and Scots but also throughout the global community (Barrett 2007). It's only in recent years that Scotland has restored a degree of political independence through the establishment of its independent Scottish parliament in 1999. Notably, the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 marked a significant turning point in Scotland’s political landscape. While the overall outcome in Scotland indicated towards a 55% majority against Scottish independence, it is important to recognise that within the Glasgow City Council area, a majority of 53.49% expressed support for independence (Jeavans, 2014).

In its historical context, Glasgow emerged as an industrial city heavily dependent on the shipbuilding industry as a main source of income and employment. However, the city was soon faced with significant challenges as the shipyards and the shipbuilding industry experienced a decline In 1971 This was caused by the withdrawal of financial support by the Conservative Government. This downturn resulted in the rise of poverty and deprivation rates in Glasgow, affecting one in five Glaswegians throughout the 1970’s. In light of the landscape at the time, Glasgow may have acquired a stereotypical reputation, due to the severity of poverty at the time resulting in the resilient nature and attitude of Glaswegians today. Since then, Glasgow has rebranded itself via campaigns of Glasgow's Miles Better (1983), Scotland with Style (2004) and most recently People Make Glasgow (2013).

Fig. 0.1 : Glasgow’s Miles Better Campaign M8 (1983).

Fig. 0.2 : People Make Glasgow (2013)

From this Research, I found myself captivated by the concept of the Glaswegian identity and wanted to understand it better, particularly through the lens of local artists. I was curious to explore how their personal experiences and cultural backgrounds were manifested in their art,

6

as well as to gain insight into the deeper significance of what being Glaswegian means to them.

CHAPTER 1 – VisualArts

Simon Murphy

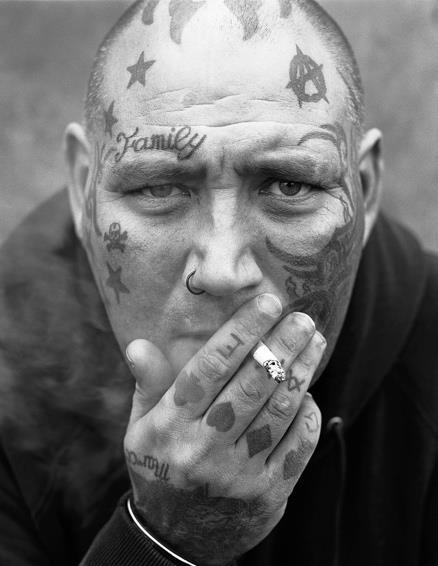

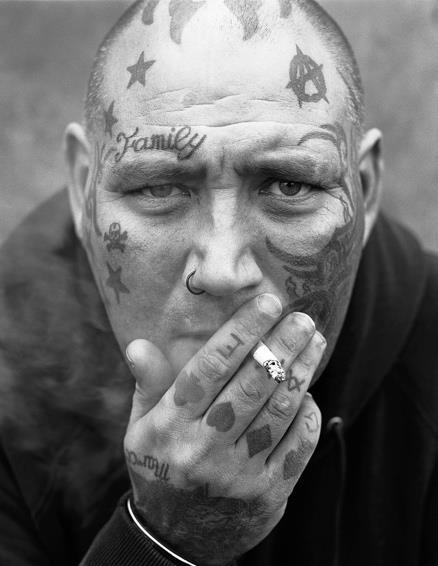

The rationale behind Glasgow’s slogan, award-winning campaign and brand, ‘People Make Glasgow’becomes readily comprehendible following the explanation of the historic roots and the resilient ethos characterising its citizens. The selection of the slogan was meticulously chosen from a pool exceeding 1500 proposals, demonstrating an extremely thorough selection procedure (BBC, 2013). Council leader, Gordon Matheson, stated the slogan was chosen as it “reflects the Glaswegian character”. He confirms the importance and influence of Glasgow’s people, agreeing with Professor Sir Jim McDonald's statement that "it is absolutely fitting that the city is putting its citizens front and centre with the new brand" (BBC, 2013) The concept of “People Make Glasgow’is brought to life by Glaswegian photographer Simon Murphy through his simple yet impactful black and white 35mm portraits of the people of the working-class, culturally diverse melting pot that is Govanhill.

This body of work brings together portraits taken over the course of several years to create a major project, a celebration of the diverse and working-class community in the south side of Glasgow. Murphy expertly presents the faces and narratives of his subjects who range in age,

7

Fig. 1.1 : Simon Murphy – Govanhill (2023)

Fig. 1.2 : Simon Murphy – Govanhill (2023)

gender, race, and religion reflecting the true multicultural mosaic of the Glaswegian neighbourhood. Murphy's lens becomes a powerful medium through which the community's stories unfold, allowing viewers to connect with the identities, experiences and stories of those who may otherwise go unseen or unnoticed.

The project's emphasis on diversity not only recognises the existence of people from different origins and races who reside in Glasgow, but it also emphasises how they are an integral contribution to the sense of community within the city.

Recognising this aspect of Glasgow is crucial since, for almost 200 years, the city has been home to people from all across Britain and beyond (Edward, 2020). Glasgow City Council stats from 2015 show that in 2011, 17.3% of Glasgow’s population belonged to an ethnic minority, “Other White” groups making up 5.8% of the total, and BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) groups at 11.6% (GLASGOW’S POPULATION BY ETHNICITY, 2015). Historically Govanhill is the first location where immigrants move to once arriving in Glasgow. Within the condensed space of about 0.33 square miles, there are an estimated 88 different languages spoken there (Barmwoldt, 2023). Govanhill is an extremely working-class area of Glasgow, with the highest level of low-income families in the city through 2021/2022 at 70%, which is 38.2% higher than the average across Glasgow (Understanding Glasgow, 2022).

Fig. 1.3 : National Records of Scotland - Percentage of children in relative low income families graph (2021-22)

During the 19th century, Glasgow experienced a massive increase of immigrants who travelled from different countries. The primary reason for this migration was the prosperity and opportunities offered by the city's newly industrialised economy Many of these

8

immigrants were fleeing poverty, famine, or persecution in their home countries and the city's newly industrialised economy offered new opportunities for a better life (Edward, 2020).

Murphy's photographs, captured with black and white 35mm film have a visually striking minimalistic feel This puts the focus on the subject of the portrait, stripping the photos of colour, which allows for no distraction to the subject's features and expressions. In turn, making them and their story the sole focal point of the work. The background of the photographs features the unglamorous tenement flats and local shops in the area. This setting provides the viewer with authentic insight into the neighbourhood and conditions of Govanhill. The photographs create an immersive sense of place for the surroundings, giving a better understanding of the area and personalities that reside there.

Overall, Murphy's Govanhill series stands as an honest and unapologetic portrayal of the real lives and everyday people of Glasgow. Thus, showcasing the beauty and complexity of human existence, rather than presenting an idealised or glamorous depiction. Through his lens, Murphy has captured the raw and authentic nature of Glasgow's multicultural and working-class residents. He reveals their struggles, hopes and dreams through the power of a single image. Furthermore, Steven Murphy's portraits from 'Govanhill' act as a moving and well-produced insight that captures the heart and soul of Glasgow and captures a glimpse of Glasgow culture and identity.

Trackie McLeod

Trackie McLeod is inspiring the creative world with his witty and humorous work that explores his cultural identity, masculinity, and queerness Despite being raised in a workingclass background, he is now a rising star, known for his unique perspective and talent. McLeod’s mixed media works often centre around the themes of football, which is undoubtedly the most watched sport in Scotland (Bradley, 1995).

Beneath the acclaimed ‘friendly’surface of Glasgow, it’s important to acknowledge the intense football rivalry and hostility between Glasgow’s two biggest football clubs, Celtic and Rangers. The realm of sports, especially football, is a universally shared interest among many

9

across the world, holding the unique capability of uniting fans from every aspect of life for their love of the sport. However, in Glasgow, there’s a historical rivalry and animosity between its two biggest football clubs, deeply rooted in sectarianism, identity and politics. Therefore, making it a vital factor contributing to the divide in attitudes of Glaswegian people and Glasgow culture.

The teams divide can be traced back to the first initial establishment of Celtic FC in 1888 (Bradley 2008). The pivotal turning point in the annals of Scottish football was catalysed by the intense sectarianism and discrimination endured by Irish immigrants upon arriving in Glasgow. Irish Catholics were excluded from mainstream football due in part to the prevailing socio-religious environment of the period, which was marked by an apparent British Protestant majority.As a result, the Irish Catholic community established their own football team in response.An additional layer to the sectarian division is the historical significance of unionism to Rangers supporters. Rangers, established in 1872 (Smith, 2023), has long been connected to Protestant unionism aligning itself with British identity, meanwhile Celtic proudly maintains its Irish identity. During the referendum debate, Rangers' status as the most significant cultural symbol of unionism in Glasgow was solidified as a potent symbol for those who favoured a "No" vote (May, 2015) and have evolved into a significant symbol for individuals in Scotland who desire to maintain their affirmation with the United Kingdom (Macmillian, 2000). Further adding to the complexity of their relationship is Celtic's affiliation to the Republic of Ireland and the Irish nationalist community of Northern Ireland. Fans have been known to express support for the unification of Ireland through rituals and symbols in Old Firm matches (Rangers v Celtic), as well as singing songs in support of the Irish RepublicArmy (IRA) and endorsing an end to the monarchy at games (May, 2015). Given these strong feelings for the independence of Ireland, Celtic found themselves as a pro-independence symbol during the Scottish Referendum. This link between Rangers and Unionism adds another layer of cultural and political significance to both team's animosity.

Glasgow was formerly known as the murder capital of Europe due to its violent, gang-related, and knife-related crimes, usually in association with the football rivalry. The birth of gangs can be traced back to sectarian rivalry, the most well-known of which is the East Ends Bridgeton Billy Boys. By the 1930s They had recruited around 500 young protestant males,

10

drawing their name from King William of Orange, who established protestant dominance over England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1680 (Davies, 2014). Over the years there have been many efforts to try and resolve the rivalry between the two teams, and although it's not as bad times in the past, it's still evident that there is still internalised sectarianism within Glaswegian football.

Fig 1.4 : Trackie McLeod – Did ThisArtwork Just Solve Sectarianism? (2021)

Despite the sinister history and ambience of Celtic v Rangers, Trackie McLeod’s work ‘Did ThisArtwork Just Solve Sectarianism?’combats the stigma by shedding light and poking fun at the hostility of fans relationship.As both fans have such different political and religious beliefs, it's easy to understand why each team would find the other one stupid. Therefore, by having each arrow pointing at the other it signifies that both reasonings for the ongoing hatred of each other is outdated and irreverent to the current political climate. The choice to use the back of the jerseys is a clever decision by the artist. The use of little branding on the back of the shirt, striping it back to just the team's colours, makes it obvious that the subject of the work is Celtic and Rangers fans, signifying just how recognisable the strips are in this context that they are put together.

11

Over time, the relevance of problems like sectarianism and discrimination have been majorly resolved, yet both teams still hold an undeniable bitterness against each other. I would personally go as far as saying that sectarianism in Glasgow today, mostly exists through, and because of football. McLeod’s inclusion of humorous elements within this discourse makes the viewer think about the evolution of the rivalry, and how the foundation of it must be reevaluated in light of the current socio-political environment. It reminds us that even while the old grudges may not have the same force, the rivalry between the two teams still exists, although on less solid ground. This work on sectarianism by Trackie McLeod provides a well thought out insight into football culture in Glasgow, a cultural identity which is shared and highly valued by many people by Glaswegians.

Ashley Rawson

ArtistAshley Rawson also makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the complexities and divisions resulting from sectarianism in Glasgow's football culture with his painting titled "Glasgow Kiss.

The painting portrays a scene where a young boy wearing a Rangers jersey and a girl in a Celtic jersey share an intimate kiss. The deliberate juxtaposition of rival team members

12

Glasgow Kiss –Ashley Rawson

engaging in an act of love serves to break the barriers posed by sectarianism and forces viewers to see people beyond their allegiance to a particular football team. There is also a level of irony in the title of the painting as a 'Glasgow kiss' is a commonly used Glaswegian slang name for a headbutt in Glasgow, a tongue-in-cheek nod to the violent reputation of the city (Williams, 2020). In my self-led interview with the artist, Rawson explained “I was originally going to make it violent, and it was just going to be a kind of a direct reflection of the phrase… but I thought, no, I'll turn on its head, I'll make it peaceful and talk about sectarianism”. In this context, the artwork challenges conventional expectations of both the teams and connotations associated with the term 'Glasgow kiss'. Instead, portraying an embrace between representatives of both teams, offering an insightful commentary on the enduring issues surrounding Celtic and Rangers Through this minor yet deliberate twist by the artist, the context of the painting has changed, creating an impactful visual gateway to tackling and overcoming the issue of sectarianism in Glasgow

Throughout the interview, Rawson explained the public’s reaction to the painting as a positive one. “It generated loads of humour… Obviously, that painting tackles a really serious issue, because that painting is absolutely loaded with the thing I saw when I was growing up…And so the Glasgow Kiss picture felt like quite a kind of nice reaction to all that, and almost like a love-over-hate thing as well.”

When speaking with the Glasgow-based artist, he discussed the influence of people and how the everyday events in his immediate surroundings impacted the subject matter of his paintings. Of all the subjects that have intrigued Rawson creatively, one in particular sticks out: the Glasgow 'Ned'. This fascinating and seemingly unique species that is exclusive to Glasgow has become a central theme in Rawson's creative endeavours. The 'Ned' is usually seen in groups wearing unusual attire, which functions almost as a uniform among them - a full nylon tracksuit and skip caps, that has developed into an aspect of their identity. Furthermore, commonly seen holding a bottle of Buckfast tonic wine firmly in hand, and their exaggerated nasal twang accent allows one to identify them instantly, overall contributing to the 'Ned Aesthetic'. Ultimately, Neds are a by-product of a working-class subculture of Glasgow which is embraced but simultaneously mocked by other groups/classes in Scotland.

13

The term Ned (Non Educated Delinquent), has earned its place in the Oxford Dictionary described as "A stupid or worthless person; a good-for-nothing; spec. a hooligan, thug, yob, or petty criminal. Also used as a general term of disapprobation" (Oxford English Dictionary 2023). Additionally, it has resonance as the Scottish equivalent of the English phrase, which is referred to as "Chav" (Young 2012).

Through describing the seemingly light-hearted traits of the Glasgow Ned it's easy to understand the somewhat comical and intriguing element this fascinating character brings to the city. Despite this, the prevalence of 'Ned' culture is often intertwined with poverty, limited educational opportunities, and a lack of social mobility. Considering earlier context regarding Glasgow's industrial decline, it becomes evident that the emergence of Neds can be attributed to these working-class struggles that characterised the city then and were still undergoing resolution through the noughties and early 2000s. An interviewee from Pockele’s journal highlights this viewpoint, stating “Neds are a product of the Glasgow society and culture... I find that because of the circle of abuse... obviously, there are still problem areas.” This quote supports the theory that working-class people's isolation, especially through housing estates known as schemes, keeps them trapped in a cycle of working-class, poverty-driven existence, explaining the rise and spread of Neds as a unique subculture in Glasgow. "Neds are the nonworking poor of Scotland, living day-to-day on bleak council housing estates and in some of the poorest areas of the country" (Pockele, 2013).

Their distinctive style can often be understood as an identity-solidifying fashion statement, but it can also be as interpreted a reflection of their low financial resources. Furthermore, the 'Ned' phenomenon is frequently linked to antisocial behaviour, which feeds into preconceived notions about hooliganism and petty crime but it’s important to understand that these actions are part of a more serious systemic problem. It is an issue in which people are trapped in a cycle of poverty and limited opportunities.

In Rawson’s series on Neds, he made a conscious decision to keep the Ned paintings comical and light-hearted to highlight the more positive side of Ned culture as the negative attributes can often overpower the good. "I wanted to do it in a gentle, humorous way because there's so much humour in it. You know, on the one side you've got maybe, you've obviously got issues of alcoholism, poverty... But at the same time, there's this wonderful culture as well, which is

14

kind of linked to it in the humour". His paintings of neds depict them in various childish and petty incidents, like trying to stop busses, putting cones on statues' heads, etc. Through intentionally only acknowledging the humanity and humour found in this unique community, Rawson's art becomes a powerful tool for promoting empathy, understanding, and appreciation for the usually discarded, marginalised people in society.

Fig 1.6 :Ashley Rawson – Too Wide

Fig 1.7 :Ashley Rawson – CommunityArts Project

Fig 1.8: Ashley Rawson – Donald’s Coronation

Rawson mentioned he chose not to include branding on the Neds' tracksuits. He painted them in uniform white shell suits, “almost like marshmallow men”. He explained this simplified motif represents their cultural recognisability in Glasgow. Furthermore, Rawson's approach challenges conventional assumptions by using humour and lighthearted characterisations which serve as a powerful catalyst for cultural reclamation. In turn, transforming negative stereotypes into a celebration of the unique identity and culture of Glasgow's working-class residents.

15

CHAPTER 2 – Music, Subculture and Pop Culture

Johnny Madden

Today, Glasgow has well-earned acclaim for its vibrant nightlife, and its array of diverse club nights and venues, thereby establishing itself as a hub for subcultural activities. The significance of music has always been a prominent component of the unique culture of Glasgow. The significance has become even more evident with Glasgow being awarded the title ‘city of music’in 2008 by UNESCO (Gilmour, 2021), specifically highlighting the significance of pop and rock genres. More recently, when considering Scotland's iconic T in the Park festival, now rebranded TRNSMT, residing in the city centres Glasgow Green each summer. The Scot’s positive reception for good music combined with the ability of ‘tanning pints’cultivates a subcultural hub. One diverse and varied enough that there’s something for everyone.

I spoke to Songwriter, producer, former frontman of the pioneering punk band Baby Strange, Johnny Madden. Baby Strange assumes a pivotal role in the Glasgow underground music scene, leaving behind an unshakable legacy that continues to inspire the next generation of bands to enter the scene. Established in 2012, Baby Strange were quick to gain recognition for their live energetic performances fuelled by their dark, aggressive melodies intertwined with relatable lyrical narratives portraying the realities of working-class life as a young person in Glasgow.

16

Fig 2.1 : Baby Strange – Photographed by Marilena Vlachopoulou (2020)

Extended Play (EP), released in 2017, is a collection of 6 songs that effectively capture the essence of Glasgow. The song Young Team stands as a strong lyrical ode to youth culture within the working-class areas affected by poverty in Glasgow. The song highlights the significance of gang culture within housing schemes situated on the outskirts of Glasgow, whilst also shedding light on the inevitable exposure to violence, to which younger boys are often introduced to by older gang members. Most groups of youths commonly identify themselves as "young teams" and often associate themselves with a specific neighbourhood or area (Decker & Weerman, 2005). For example, one of the most well-known young teams of the East End of Glasgow is the Real Calton Tongs, who patrolled the area of Calton for around 60 years, marking their territory by vandalising buildings with the word 'Tongland' (Brown, 2011).Although this example is from the East End of Glasgow, the same territorial divide took place in many schemes across the whole of Glasgow. During my interview with Johnny, he explained the inspiration for the song came from his own personal experience growing up around young teams in the area he lived in, Springburn. “Songs like Young Team…that was just me writing about being young and living in Springburn, and kind of almost slipping into that life…”. The lyrics of the song vividly paint a scene of young boys taunting rival gangs for ‘fun’, and the line "shaved my head when I was fifteen" emphasises the young team's unifying image. Johnny then explained that he made a conscious decision to step away from the streets and started to pay attention to the events of his everyday life and use these experiences of working-class culture to fuel his creativity.

The connection between drug use and social issues, particularly in economically deprived regions like the 'schemes', is a multifaceted problem that has found expression in more recent tracks from Baby Strange "Job in the City (Working for Nothing)" and "Viewpoint" provide an insightful commentary on the hardships of working-class life in Glasgow and highlight the ongoing drug problem in Scotland. Scotland has been considered the drug death capital of Europe for many years (Samson, 2023).Although drug misuse deaths are at their lowest rate since 2017, statistics of 1,051 deaths in 2022 solidify this title for Scotland, with the highest drug-related death toll in Europe. (National Records of Scotland Web Team, 2023). Greater Glasgow and Dundee City hold the highest rate of drug misuse deaths in Scotland (National Records of Scotland Web Team, 2023) with Heroin addiction being the most common form of serious drug dependence in Glasgow (Greater Glasgow North Forum, 1999).

17

Fig 2.2 : National Records of Scotland - Drug misuse deaths for selected council areas, age standardised death rate 2018-2022 graph (2023)

Baby Strange's lyrics in the song 'Viewpoint' act as a raw and unfiltered narrative that humanises the challenges faced by individuals trapped in the cycle of drug addiction within schemes. Thus, shedding light on the urgency for societal and public health efforts to address the challenges often associated with drug abuse.

“Everyone’s so crystal eyed Hangin’round the chemist from 9 to 5 Cutting about, wonder when the next hit is Methadone programme’s never gonna solve it When are the government gonna put the fix room here?

Standing on needles, want the pathways clear”

‘Viewpoint’– Baby Strange, (2019)

The lyrics of 'Viewpoint' serve as a call to action, encouraging society to address and work towards undoing the systemic issues that control the cycle of drug dependence in these communities. Since the release of this song, Glasgow has pioneered progressive solutions by becoming the forefront of change, standing as the first city in the UK to implement consumption rooms for illegal drugs, marking a ground breaking stride towards minimising the severe health risks associated with unsterilised needles (Cook, BBC News, 2023).

18

The visual elements in Baby Strange's artwork for 'Viewpoint' contribute significantly to portraying this harsh reality, featuring images of high-rise flats and doctors' prescriptions to effectively convey the message. Moreover, 'Viewpoint' functions as an effective piece in confronting the issues within Glasgow's working-class communities, providing listeners with a troubled yet honest observation of Glasgow's culture and identity.

The appeal of Baby Strange's music not only created a bond amongst young people from the working class but also birthed a whole music scene. This subculture gained recognition from the BBC for its hub of great artists and loyal like-minded gig-goers. The importance of Baby Strange’s music in creating the Glasgow punk scene can be easily explained through Will Straw's definition of a ‘musical scene’. “Acultural space in which a range of musical practices coexist, interacting with each other within a variety of processes of differentiation, and according to widely varying trajectories of change and cross-fertilisation” (Straw 1991: 373). This definition focuses on the importance of how certain musical activities contribute to creating a sense of community, which can be seen in the evolution of Punk in Britain. Punk rock has been historically significant within the UK, as the 1970’s saw the British working-class youth express their dissatisfaction through musical outlets. This period is marked by high unemployment and inflation previously discussed in Chapter 1. This manifested through the emergence of a distinctive subculture, reflected in music, style, and attitude (Simonelli, 2002).

19

Fig 2.3 : Baby Strange – Viewpoint (2019)

Given the context behind the connection between punk music and working-class culture, Baby Strange's music echoes the significance of the past, acting as a pivotal influence in today's musical landscape. The band's music exemplifies a modern-day revival of the Punk Scene in Glasgow, in light of the economic challenges faced by the city today. Moreover, the band's influence extends beyond just creating exciting music, as it fosters a sense of community among working-class youth, contributing to cultural creation. In conclusion, the band have not only rejuvenated the punk subculture within Glasgow but has also left a memorable mark on the city's underground music scene. Overall, their music, local club nights, and ability to foster a shared identity among young people resonate with the historic working-class cultural identity of Glasgow.

Billy Connolly

The charm and humour of the Glaswegian identity and attitude can be found in Scottish Pop culture. Billy Connolly, known to Scots’as the 'Big Yin' is a proud working-class Glaswegian turned globally successful comedian, actor, musician and artist. Furthermore, known for his humorous genius that reflects both his talent and cultural identity. Described by Micheal Parkinson on his TV show Parkinson: The Final Conversation as "a man from the Glasgow shipyards who was merely windswept and interesting before his rise to fame and the world claimed him" (Parkinson, 2007). This quote perfectly captures the eccentric and whacky character that is known and loved not only by Scottish people but treasured by the whole world.

20

Fig 2.4 : Edmund Smith – Billy Connolly’s Big Banana Feet (1975)

Although Connolly's repertoire ranges from roles voicing in Disney animations to acting beside massive Hollywood names like Jack Black and Jim Carrey, his most notable work in Scotland, is his early days of stand-up comedy. The shows would be filled with stories of drunks at parties in Glasgow and rude unpredictable jokes like “Scottish-Americans tell you that if you want to identify tartans, it’s easy – you simply look under the kilt, and if it’s a quarter-pounder, you know it’s a McDonald’s". In true Glasgow fashion, he was also known to pull out his guitar on stage for a song or two. Fan favourites include 'I Wish I Was In Glasgow' and 'If It Wisnae For Yer Wellies'. The success of these shows would build up to one of the most significant and iconic moments in his career.

In 1975, Connolly reached out to designer Edmund Smith commissioning a pair of size 9 banana boots, which emerged on stage for the first time atAberdeen's Music Hall the same year.Adocumentary was released with the title Big Banana Feet, named after the famous boots due to its overwhelmingly positive reaction. They became a trademark for the comedian and today are on display at Glasgow's The Peoples Palace Museum, now regarded as an iconic example of Scottish pop culture.

Although Connolly's decision to wear these boots alone became an iconic moment, the significance of the shoes extends beyond their appearance. The boots are a clever nod to the old Scottish rhyme "Skinny Malinky Long Legs," where the lyrics have been brought into literal form.

“Skinny Malinky Long Legs

Big Banana Feet

Went to the pictures

And couldnae find a seat....”

Skinny Malinky Long Legs

Jaffe (2000) has claimed that a significant part of Scottish humour lies in exaggeration, and this is certainly the case for Connolly's Banana Boots. By wearing the banana boots, Connolly reinforces his Glaswegian identity and creates a comically endearing link between his comedic persona and the cultural identity he represents.

21

Asimilar style of humour can also be found in the popular Scottish TV show Chewin the Fat, which plays on the exaggeration of socially recognisable and stigmatised Glasgow characters Foe example, the previously discussed Glasgow Ned, and the portrayal of a hard Glaswegian gangster named "The Big Man" (Braber, 2017).Additionally, Braber argues that humour in Scotland is much like Coupland's observation of humour in Wales, characterised by "laughter WITH' rather than 'AT" speakers of a Welsh accent, creating a sense of inclusivity and shared cultural experience (Coupland, 2001).

An essential understanding of the Glaswegian attitude is that the humour is light-hearted and the ability to poke a bit of fun at ourselves. This quality about Glaswegians is portrayed brilliantly by Connolly’s shtick with his ‘Big Banana Feet’. Connelly was knighted in recognition of his services to entertainment and charity by the Queen in 2017, truly proving his influential force across Scotland and the World (Kennedy, 2017). I see a lot of Connolly in my Grandad, from their unpretentious sense of humour to their hippy-like fashion sense, and I think this quality is what makes Connolly so well-received internationally. Throughout his career, he has always stayed true to his Glaswegian identity and remained humble in his working-class roots.

22

Fig 2.5 : Billy Connolly - Billy Connolly’s Big Banana Feet worn on stage (1975)

He has become a symbol of Glasgow's resilience, humour, and warmth so much so three murals of him have been painted throughout the city. Through his storytelling, he portrays an honest picture of the people, places, and experiences that make Glasgow unique. His ability to connect with people through laughter has crossed cultural boundaries, making ‘Sir Big Yin’ a beloved figure of Glaswegian identity; not only in Glasgow but also across the world.

23

CHAPTER 3 - Literature

GraemeArmstrong

Hailing fromAirdrie, a small town outside of Glasgow, GraemeArmstrong infuses his writing with an authentic voice, drawing inspiration from the very real events that have shaped his life. Despite being deeply immersed in gang culture from a young age, he defied expectations by channelling his energy into literature after being inspired by "Trainspotting"

By the age of 16, he had accumulated 15 criminal charges, but his determination to study literature led him to secure an offer to Stirling University. After being expelled from school and gaining his troublemaker reputation, teachers labelled him as a bit of a lost cause but Armstrong persevered, earning acceptance into university, later completing a master's degree. His life has been marked by the brutal realities of alcoholism, drug misuse, and violence within the young team, with friends succumbing to murder, suicide, or drug overdoses. Armstrong's conscious decision to break free from this cycle marked a turning point, leading him towards a path of positive change. Today, he stands as a celebrated author, recognised for his debut novel "The Young Team," a compelling fictional story that reflects not only his personal journey but also the broader challenges of working-class life in Glasgow. The story follows main character 'Azzy', through his first encounter with love, drugs, and rehabilitation, all events based on the events of the author himself.

WhileArmstrong's portrayal of life within the young team is insightful and authentic, he also cleverly incorporates his West Central Scots dialect into the dialogue and narrative of the novel. This dialect is a vital tool that helps capture the essence of everyday life in Glasgow and surrounding areas, providing readers with a genuine insight into the characters' experiences.

24

One of the key features of the Glaswegian dialect is the use of 'glesga' slang, which is influenced by working-class culture. Glasgow is known as the 'home of the glottal stops,' (Macafee, 1997) one of the city's most prominent silent features. This is where certain words have no harsh pronunciations of the letter T, for example, the word 'patter,'. Despite being historically stigmatised, there has been an increased use of the glottal stop among younger generations of Glaswegians across the working and middle class (Stuart-Smith, 1999).

Studies have also shown that the use of foul language and swearing is socially accepted in Scottish dialect, forming a natural part of its repertoire (Braber, 2017). These linguistic elements often function as identification of social identity and serve as camaraderie among the working class. The way we use language is one of the most fundamental ways we have of establishing our identity (Thornborrow, 1999).

In a study conducted by Braber on the Glaswegian accent, it was found that the accent can be divided into variations based on location and other factors. The 'common' Glaswegian accent is primarily spoken by working-class people, whereas the 'Kelvinside' variation is associated with the middle class and is often perceived as posh or put on.Almost all participants noted that certain aspects of the common Glaswegian accent are rough or 'ugly', even among those who speak it themselves. The study's findings suggest that despite the negative connotations associated with the accent, Glaswegians take great pride in their Glasgow identity and use their dialect to signal solidarity among working-class speakers, maintaining distinctiveness from other social groups (Braber, 2017).

These factors are evident in the very first sentence of The Young Team, immersing the reader into the raw and unapologetic world of the Glaswegian dialect. The quote "The rain n wind ir fuckin howling," captures the essence of Glasgow slang and mirrors the authentic pronunciation of the Glaswegian accent, as exemplified by the use of 'ir' instead of 'are'. This quotes use of profanity is not gratuitous; rather, it serves as a way of emphasising the characters' attitudes and emotions with a distinctive intensity. This can also be seen in the title of this dissertation and the main catalyst of it all forArmstrong, "It's shite being Scottish!" from Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting. This intentional incorporation of swearing is not aimed at insult; rather, it functions as a means to emphasise their genuine emotions towards different situations. Moreover, the opening sentence of "The Young Team" is a bold, unfiltered introduction toArmstrong's narrative approach, deeply rooted in the cultural and linguistic landscape of Glasgow.

25

Fig 3.1 : GraemeArmstrong – The Young Team Book Cover (2020)

When speaking to Graeme about the importance of dialect within The Young Team, he explained the importance of him being honest in the book regarding his own spoken and written voice. "I said once Standard English is my second language and I truly wasn’t exaggerating,"Armstrong emphasised that the language holds equal significance to the authenticity of the story when writing the book. He believes that genuine storytelling would be incomplete without incorporating the distinct accents and dialect of the individuals involved. "Language is life, to be denied your mother tongue is to be denied your identity."

Armstrong discussed some online reviews of his novel, accusing his book of feeding into the phenomenon of 'poverty porn', which supports the assumption that working-class art is created solely for the consumption and amusement of middle/upper-class readers (Clough et al., 2023). This is something thatArmstrong proclaims cannot be further than the truth, and the message of the novel is to convey respect, especially to the working-class people he knew who have suffered at the loss of violence, substance misuse or suicide.

Armstrong emphasised that to many outsiders, Scotland is often perceived as the picturesque land of kilts, breathtaking landscapes and home to the mystical Loch Ness Monster. However, he delves into the less-explored realities of the ongoing historical problem of gang and knife crime that has troubled the streets of Glasgow for centuries. Through his novel,Armstrong skilfully reveals this darker part of Scotland, steering clear of any romanticisation, while simultaneously, celebrating the resilient and communal spirit ingrained in working-class culture.

AlthoughArmstrong's exploration of Scotland's working-class culture and language has similarities with previous works, such as 'Trainspotting', 'The Young Team' stands out by offering a contemporary and relevant perspective on Scotland's current socio-economic landscape. His work is an updated contribution to the understanding of the country's societal issues.

In conclusion, GraemeArmstrong's debut novel "The Young Team" is a powerful testament to the importance of authenticity and language in storytelling. Through infusing his writing with the genuine voice of the North Scots dialect combined with his genuine life experiences, Armstrong successfully captures the essence of everyday life in Glasgow.

26

CONCLUSION

Overall, as I have reflected on the difficulties Glasgow has confronted throughout this dissertation, it becomes evident that the city is not defined solely by its struggles, but by the collective determination to overcome the hardships faced by working-class people. Glasgow has proven that adversity can be a catalyst for positive change, establishing a well-deserved underdog title among the other cities in The United Kingdom. The city's resilience and commitment to social progress serve as an inspiring narrative, challenging preconceived notions associated with the city and highlighting the strength and character that emerges from a community united in purpose.

Additionally, the variety of artistic expressions that arise from Glasgow echoes the city's distinct character and spirit of its people. The proud nature of Scottish people is undoubtedly reflected in the art of the discussed artists. Glasgow showcases a diverse culture, from the iconic sounds of its most influential indie bands to the underground rave scene, and from a Glasgow Kiss to Big Banana Boot, Glasgow's art is a reflection of its people and serves as a medium through which the city can communicate its identity to the world.

To end the interviews with the discussed artists, I raised the question, in the words of Trainspotting's Renton 'Is it shite being Scottish?' to which I received an overwhelming amount of positive feedback on Glasgow and Scotland.

Johnny Madden's answer to the question was " It's not shite being Scottish. I love being Scottish!" In his response, Johnny mentioned that many individuals in the creative field tend to relocate to larger cities in the UK, especially London, as soon as they are presented with the opportunity. However, Johnny himself has been offered such opportunities and he would rather reside in Scotland due to his strong fondness for Glasgow. "As much as it can be a bit of a shitehole at times, it's my shitehole." This perspective, shared by many Glaswegians including myself, encapsulates a unique pride in our identity. It suggests that, despite occasional challenges, there's collective humour and loyalty to our hometown. It reflects a shared understanding that our city may not always be glamorous, but it holds a special place in our hearts.

Ashley Rawson shares Johnny Madden's optimistic view, expressing, "I don't think it's shite being Scottish! "I believe Scotland is an amazing place; it's not shite to be Scottish!" Rawson, who has been criticised for portraying negative aspects of Glasgow in his art, responded candidly, "I base my art on my experiences and life, and that's all there is to it”. He defends his art by exploring an overlooked cultural side of Glasgow that is a fantastic part of the Scottish experience. Rawson aims to contribute to a nuanced understanding of being Glaswegian or Scottish by creating art that highlights an underrepresented side of the city's culture.

27

"It definitely has its moments being Scottish" was Armstrong's reply. Like Madden, Armstrong disclosed about moving to London for an escape to a new world, which ultimately led him back to Scotland, feeling almost disconnected from his identity whilst living there.

"It’s easy to love home and hate it simultaneously". Armstrong expressed that Scotland has caused many hurts in his lifetime, but the sense of community, family and togetherness that has been established here, is something he doubts he could find anywhere else. 'As a sound Scottish cunt yi wid generally be well received. Plus, the burds love it, it’s no that shite being Scottish, Irvine...’ (The Young Team, 382)

As I conclude this dissertation, I stand proud in my Glaswegian and Scottish heritage. No matter where life takes me, I will always hold the memories of my hometown dear, just as I believe Glasgow cherishes its history of hardworking people.

Let Glasgow Flourish.

28

REFERENCES

Ahistory of the world - object : Billy Connolly’s Banana Boots (no date) BBC.Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/_Cx09IbmQ-e0FiCw2R7ZJQ (Accessed: 30 November 2023).

Anderson, R. (2015) Strength in numbers:Asocial history of Glasgow’s popular music scene (1979-2009).

Armstrong, G. (2020) The Young Team. London, UK: Picador .

Barber, N. (2017) PERFORMING IDENTITY ON SCREEN Language, identity, and humour in Scottish television comedy[Preprint].

Barmwoldt, L.E. (2023) Simnon Murphy - Govanhill Handout.pdf, Google Drive.Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BBxqhz-j7wpEUCEVE60mW1_0fPNHS5ou/view (Accessed: 22 December 2023).

Bradley, J.M. (2008) ‘Celtic football club, Irish ethnicity, and scottish society’, New Hibernia Review, 12(1), pp. 96–110. doi:10.1353/nhr.2008.0028.

Bradley, J.M. (1995) ‘Football in Scotland:Ahistory of political and ethnic identity’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 12(1), pp. 81–98. doi:10.1080/09523369508713884.

Braber, N. (2009) ‘“I’m not a fanatic Scot, but I love Glasgow”: Concepts of local and national identity in Glasgow’, Identity, 9(4), pp. 307–322. doi:10.1080/15283480903422780.

Brown,A. (2011) How we Ran Glasgow’s biggest gang out of town, Daily Record.Available at: https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/how-we-ran-glasgows-biggest-gang1110167 (Accessed: 23 December 2023).

Cassidy, P. (2018) The history of Glasgow’s street gangs: Tongs Ya Bass, Glasgow Live. Available at: https://www.glasgowlive.co.uk/news/history/history-glasgows-street-gangstongs-12252432 (Accessed: 09 January 2024).

Clough, E., Hardacre, J. and Muggleton, E. (2023) ‘Poverty porn and perceptions of agency: An experimental assessment’, Political Studies Review, p. 147892992311524. doi:10.1177/14789299231152437.

Cook, J. (2023) UK’s first consumption room for illegal drugs given go-ahead, BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-66929385 (Accessed: 04 January 2024).

Cook, J. (2020) The young team by Graeme Armstrong Review – a swaggering, incendiary debut, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/mar/13/theyoung-team-graeme-armstrong-review

29

Davies,A. (2014) City of gangs: Glasgow and the rise of the British gangster. London: Hodder.

Decker, S.H. and Weerman, F.M. (2005) European street gangs and troublesome youth groups. Lanham (Md.): AltaMira Press.

Devine, T.M. (1991) Irish immigrants and Scottish society in the nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. John Donald.

Edward, M. (2020) Who belongs to Glasgow?: 200 years of migration. Edinburgh, Scotland: Luath Press Limited.

Falk, G. (2024) Here are 80 of sir Billy Connolly’s best jokes and one liners, The Scotsman Available at: https://www.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/heritage/billy-connollys-bestjokes-80-of-the-big-yins-funniest-jokes-and-one-liners-4458332.

Greater Glasgow North Forum (1999) Tackling drugs together in Greater Glasgow: Strategy 1999-2003. Glasgow: Greater Glasgow DrugAction Team.

‘People make Glasgow’unveiled as New City Brand (2013) BBC News.Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-23084390 (Accessed: 15 December 2023).

Gilmour, L. (2021) Glasgow dubbed UNESCO City of music thanks to ‘iconic’ venues, Glasgow Times. Available at: https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/news/19649030.glasgow-dubbed-unesco-city-music-thanksiconic-venues-barrowlands-hydro-king-tuts/ (Accessed: 09 January 2024).

GLASGOW’S POPULATION BY ETHNICITY)

https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/councillorsandcommittees/viewSelectedDocument.asp?c=P62A FQDNT12U0GDN2U.Available at:

https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/councillorsandcommittees/viewSelectedDocument.asp?c=P62A FQDNT12U0GDN2U (Accessed: 22 December 2023).

Jeavans, C. (2014) In maps: How close was the Scottish referendum vote?, BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-29255449 (Accessed: 27 November 2023).

Kennedy, M. (2017) Billy Connolly leads the way in queen’s birthday honours list, The Guardian.Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/jun/16/billy-queensbirthday-honours-list-billy-connolly-jk-rowling-paul-mccartney-delia-smith (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

Lappin, S. (2007) Parkinson: The Final Conversation. 16 December.Available at: https://player.stv.tv/episode/4jbl/parkinson-final-conversation (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

30

May,A. (2015) ‘An “anti-sectarian” act? examining the importance of national identity to the “offensive behaviour at football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) act”’, Sociological Research Online, 20(2), pp. 173–184. doi:10.5153/sro.3649.

Munro, M. (2013) The complete patter. Birlinn.

National Records of Scotland Web Team (2023) National Records of Scotland.Available at: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/news/2023/drug-related-deaths-decrease (Accessed: 28 December 2023).

Oxford English Dictionary 2023, 'Ned, n.2', Oxford English Dictionary Online,Available at: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/ned_n2?tab=meaning_and_use#35026046 (Accessed: 14 December 2023).

Paterson, S. (2023) Humza Yousaf says Scotland stands ready to take refugees from Gaza, Glasgow Times.Available at: https://www.glasgowtimes.co.uk/news/scottishnews/23861952.humza-yousaf-says-scotland-will-take-refugees-gaza/ (Accessed: 04 January 2024).

Pockele, S. (2013) NedAesthetics in contemporary Glasgow : Performing classes, appropriating races [Preprint]. doi:10.22215/etd/2013-07007.

Rawson,A. (no date)About.Available at: https://www.ashleyrawson.com/about (Accessed: 15 December 2023).

Samson, K. (2023) Scotland drug deaths decrease, but rate still highest in Europe, Channel 4 News.Available at: https://www.channel4.com/news/scotland-drug-deaths-decrease-but-ratestill-highest-in-europe# (Accessed: 28 December 2023).

Simonelli, D. (2002) ‘Anarchy, pop and violence: Punk rock subculture and the rhetoric of class, 1976-78’, Contemporary British History, 16(2), pp. 121–144. doi:10.1080/713999447

Smith, I. (2023) The orange effect - duo.uio.no, The orange effec. Available at: https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/105388/1/Ian-Smith-MITRA-MastersThesis.pdf.

https://www.glasgow.gov.uk/councillorsandcommittees/viewSelectedDocument.asp?c=P62A FQDNT12U0GDN2U (Accessed: 22 December 2023).

31

APPENDICES

Interview with GraemeArmstrong

1. In your opinion, is there anything about Glasgow that makes it such a unique and/or special place in terms of Scottish culture and heritage?

Glasgow is naturally the cultural epicentre of Scotland’s West Coast. I grew up around 5 miles east in North Lanarkshire. The city was the focus of almost all the artistic depictions of working class life that resonated and were reflective of my experience growing up in Airdrie. Chewin the Fat, Still Game and latterly Burnistoun, were sitcoms or comedy sketch shows laden with exaggerated caricatures which, as well as being incredibly funny, were deadly accurate in capturing not only the community’s ticks and tells, but something more profound about the Scottish psyche: dark humour, self-deprecation, resilience in the face of adversity. There was a darker side to life here explored more so in the works of social realism like Ken Loach’s My Name is Joe (1998), Sweet Sixteen (2002) and Peter Mullan’s NEDS (2010), although set before my generation’s exposure to young team gang culture. These showed honestly the often-ugly side of poverty, violence and working class struggle. These films reflect a particularly monochrome world, where happy-ever-afters are sadly in short supply. This is a reality for many lives here. Despite Glasgow’s proximity to North Lanarkshire and its shared culture for the most part, it is still a large city versus a collection of decaying post-industrial towns: Airdrie, Coatbridge, Bellshill, Motherwell, Hamilton, Carluke, Larkhall, etc. – a series of attached mining villages – and new towns such as Cumbernauld and East Kilbride. Experiences within these urban town, sub-urban and semi-rural settings, often surrounded by natural countryside and limited social mobility are different from inner-city stories, or even Loach’s Greenock in Sweet Sixteen. That said, the city feels familiar and like we have some ownership of it. We might not belong to Glasgow, but does Glasgow belong to us? I think so, at least artistically.

2. As a Scottish artist/author, what messages and emotions do you aim to convey about working-class Scotland and its people through your work?

One of the most over-repeated and irrelevant critiques of working class literature, by both native working class readers and hostile critics, is that working class art is created solely for the consumption by and for the amusement of middle/upper class readers/viewers. The ‘poverty porn’ phenomena is likely to blame for this. This doesn’t come with any satisfying set definition or parameters but is typically used as a derogatory statement towards working class writing or film. This can be seen in representations which are engineered to lure working class people into situations or discourses which cast them in a poor light for the amusement of higher audiences and are often sadistic in tone. The Scheme (2010) The Jeremy Kyle Show (2005-19) etc. These were staged in such a way which would inevitably leave subjects appearing foolish or othered, like a form of modern blood sport. Other works are overly sentimental and are designed to illicit a reaction of pure sympathy, a sort of Dickensian pity party for the underserving poor. I have read readers’ online reviews and at least one critical review in a broadsheet which accused me of this very thing. Of course, this is complete bollocks. I wrote The Young Team from a genuine desire to explore Scottish gang culture gang and to interrupt their powerful allure young people. It’s a modern work in the sense that it deals with debates such as masculinity, mental health and addiction in a way that many past examples don’t. Culture and discourse in a society evolves, its literature is reflective of this. My novel is the artistic result of an incredibly potent and lonely experience of the consequences of a decade of violence and substance misuse. Trainspotting initially inspired me to pursue the study of English literature as a sixteen-year-old, so the transformative power of the written word was never lost upon me. The predominant message I tried to convey is

one of respect, especially to the young men and women I knew who lost their lives to violence, substance misuse or suicide. My intent was never to create a sense of voyeuristic wonder or amuse those situated above The Young Team’s characters, but to create hope and a sense of a tangible beyond for those who lived this life as I did and for young people still living within this reality.

32

3. Being from outside of the city, do you feel like you have a strong cultural identity within your hometown?

I have always felt being from North Lanarkshire was uniquely its own thing. Airdrie and Coatbridge have often escaped cultural representation, but in recent years with Coatbridge native Des Dillon’s numerous novels and play Singing I’m No a Billy, He’s a Tim (2005), David Keenans’ This is Memorial Device (2017) and even New York Times Bestselling author and comic book writer Mark Millar Wanted (2008) Kick Ass (2010) etc. starring a raft of international A list stars – well, it feels like anything is possible here. I’m pleased, like Mr Keenan, to have been successful in creating an artistic rendering of a place often forgotten. Our experience in the fringes of a city were different and our identities a should be given the freedom to be autonomous, both artistically and linguistically. Our rendering of the Scots language has its own lexicon, syntax and rhythm which are unique, if almost undetectable to the outside ear. I’m proud to be from that particular mix of Airdrie and Coatbridge that many feel is home.

4. Knowing of your strong connection with ned/gang culture, does this play into your connection to your local identity? In this work, I consider how neds and young teams have been such a prominent part of Scottish culture and are unique to Scotland. Do these identities play into each other or are they completely separate?

The sense of a local or national identity are absolutely fundamental to young team gang membership in Scotland. Gangs are and have always been a global phenomenon. Immediately we conjure LA’s Bloods and Crips, MS13, City of God’s Brazilian favellas, even more kitsch renderings West Side Story or The Warriors etc. People are unlikely to immediately associate Scotland, the land of tartan tat and the Loch Ness fuckin Monster with a hundred years of serious territorial violence, life changing maiming with blades and murder; Nor the most part of central Scotland forming a patchwork quilt of territories spanning the endless schemes – with unique names and acronyms sounding more like Northern Irish paramilitaries – e.g. (Y.C.B – Young Crazzy Bush - in Airdrie or the LL TOI – Lang El Toi - in Coatbridge). Yet, this is the reality for generations of young and old in Scotland, including myself. We almost love to hate neds and young team members in Scottish culture, but there is a sort of warped pride at play. Even recent Indie band The Snuts affectionally named their smash debut Album, an elusive W.L – a reference to the ‘Whitburn Loopy’ – their local young team. Lewis Capaldi tans Buckfast wine on stage. These identities both local, national and gang for many are inseparable, a source of shame and simultaneous pride.

5. One of the most noticeable stylistic choices in The Young Team is that it’s written in Scots language. How important was it for you to write the book this way?

The choice to use a full Scots language portrait in The Young Team was a crucial one to me. It was absolutely emboldened by Irvine Welsh’s multiple East Central Scots narrators in Trainspotting. This was my baptism of fire into the world of Scottish literature. While Kelman knocked down the door for cultural recognition, winning the then Man Booker in 1994 with How Late It Was, How Late (1994), he and his contemporaries, such as Janice Galloway, The Trick is to Keep Breathing (1989) used a more Anglified Scots language, peppering in odd words and phrases, breaking the strict rules of Standard English on the page and in the gatekeeping prone and stuffy world of UK publishing in English literature. These are fairly mild in comparison to Welsh’s full throttle Trainspotting narrators, distinguishable by a series of vocal tells, motif phrases and words, profanity bombardment and beautiful and brutal Scots rendering. The Young Team’s West Central Scots dialect is undeniably indebted to this. It was important for me to be honest on the page around my own spoken and written voice. Every realised written rendering of Scots has its own patterns in lexicon and syntax. There is no set standardisation and the largely celebrant Scots of Burns etc. bears little resemblance to most modern Scots speakers. I said once Standard English is my second language and I truly wasn’t exaggerating. My own voice, my true voice – is West Central Scots. I possess another language: a formal one which is sometimes demanded and allows me to respond in academic writing, such as this. This is the deviation for me, not the other way around. I stand by that. Language is life, to be denied your mother tongue is to be denied your identity.

33

6. In your documentary film Street Gangs (2023), a point is made around the decline of a visible presence of gang members on Scottish streets, especially wearing typical ‘uniform’ of tracksuits and Berghaus jackets. Is this an evolution of the ned subculture or is in in terminal decline?

Gang culture is always subject to cultural evolution. Neds in Peter Mullan’s NEDS (2010) are wearing flares and leather trench coats – a world away from our fitbaw trackies and primary colour Mera Peak jackets. The gang names are the same, however, and the geography is a constant. Cultures and fashions come and go. The core truths, drivers and behaviours of gangs remain the same. Rather than a new alien culture, generations use what they have available to cause chaos and chase the buzz and fight others and boredom. We saw the advent of drugs like Ecstasy, which changed our patterns of substance abuse and behaviour. Social media played a backseat role, which now takes centre stage. Our musical interest was rave and self-generated Scottish PCDJ culture, a subculture of DIY bedroom bootleggers. Rave has declined among working class youth in 2023. From the investigation in Street Gangs and from many testimonies – the dominant cultural influence is an import from the US and London in the form of Drill/Grime music. The themes are largely similar: poverty, drugs, gangs, violence. We listened to Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls. It’s horses for courses. In a few years time, a rave resurgence might happen when Drill’s moment has passed. Are neds gone forever? Unlikely. As with all cultures, it’s cyclical. Football hooliganism/ Casual Culture seen a massive resurgence in the 2010s (The Green Brigade / Union Bears) which was dominant in the 80s and early 90s. Neds may return yet.

7. There are obviously lots of negatives tied to ned/gang culture: violence, alcohol and drug problems etc. Do you think these problems are still as relevant in this ‘new era’ of gang culture? In this work, I speak to an artist who celebrates and makes light of ned culture through his art... Do you think there are any positives which come from ned culture?

It would be foolish and untrue to completely disregard ned/ young team culture as purely negative. Almost all youth cultures have risk taking behaviour attached and lots are simply attributable to rebellious youth itself. Neds and young teams are the result largely of a social reality of hardship. It’s no mistake that the vast majority of Scottish gang members are working class young people from schemes. Neither they nor the prison estate are filled with the middle and upper classes, people who have many opportunities, prospects and wealth. Both gang members and prisoners are predominately from the most challenging socio-economic backgrounds. It’s also a question of geography. If you are born in Easterhouse, do you have the same opportunity as someone born in St. Andrews? Unlikely. There is a tendency to try and gentrify and commodify all youth subcultures. It happened notably to rave and is still happening. Many DJs now are not the working class heroes they once were, but people from higher social standings with the necessary network and finance to break in. Neds and gangs are very difficult to imitate in this way. I suspect this is the reason why both young teams and PCDJ culture have never really been celebrated, canonised, or replicated. They offer no opportunity, neither in commercial terms nor in cultural capital, to the middle classes, undeniably the purveyors of culture. They are treated as repugnant, something to be mocked and forgotten. I am often suspicious of working class representations by people without lived experience. There is a valid debate about the right to represent these groups. People in the working class and/or who experience poverty are not a protected category. It would be unlikely for anyone to attempt this for any other group classified in this way. Working class people, largely voiceless and disenfranchised culturally and in the media, are easy targets to demonise. Any positives are to be determined only by those who lived it. The brother/sisterhood, camaraderie, and unique Scottish experience of being a young team gang member was fraught with danger and seldom had a happy ending – but offered a moment in our shared history – for good or bad – it’s hard to say. I’d direct people to The Young Team and offer no further comment. See for yourself.

7. And finally, in the words of Trainspotting's Renton... Is it shite being Scottish?

It definitely has its moments being Scottish. I’m proud equally to be Scottish and from Airdrie and Coatbridge. Being Scottish is inseparable to me from that sense of mental humour, patter fur days, Scots language, a globally revered history of defiance, national struggle and always underdog, but ultimately never defeated. Braveheart, Trainspotting, Glencoe, Glasgow, tartan, The Old Firm: It’s all these things simultaneously to me. I lived in

34

London for a few years and felt adrift for most of it, excited by the prospect of escape to a new world but also pulled unmistakably back towards home. Is it Stockholm Syndrome? Probably. It’s easy to love home and hate it simultaneously. Scotland has caused many hurts in my life but also given me a profound sense of community, togetherness and family, which I doubt I would find elsewhere. Maybe the future holds another place out there for me, but Scotland is always home. Plus, where else has a Time Capsule, apart from the mighty Brig? Young Mavis, ya bams! LL TOI fur dayz n dayz! ‘As a sound Scottish cunt yi wid generally be well received. Plus, the burds love it, it’s no that shite being Scottish, Irvine...’ (The Young Team, 382)

Interview withAshley Rawson

Keira: So I wrote down a couple of questions here. You don’t need to stick to them or anything. It's just kind of like prompts. But the first one is, in your personal opinion, what is it about Glasgow that makes it such a unique and special place in terms of Scottish culture and heritage?

Ashley: Oh, that's a tricky one. I think. I think it's probably to do with, so Scotland obviously is a, you know, there's probably quite a lot of different sides to Scotland itself, you know, so if you go up north, it's quite, it's almost like it can feel a bit like a different country because it's so kind of, you know, it's very scenic, it's not industrial. And even if you go through to Edinburgh, there's a very different, you could almost be in another country again. So I think Glasgow is kind of, you know, the weird thing is, I actually think Glasgow is quite like places like if you've ever been to Liverpool.

Keira: You know what, someone else I was interviewing also said the exact same thing.

Ashley: It's like, I think Glasgow and also maybe Dundee, they almost feel a bit like outliers because they're both really industrial and that's their heritage and they're a bit more like somewhere like Liverpool or Manchester or Belfast.

Keira: That's so funny, the last person I interviewed said the exact same thing.

Ashley: Yeah, yeah. And I think it's because of the people. So Glasgow and Liverpool probably have a lot of people who are of maybe Irish descent, who are, but also, you know, indigenous to Scotland, but they're all working class, it's working class culture. And I think from that comes a kind of a banter and a kind or maybe a sense of humour that's quite kinda different. I often think Edinburgh and Glasgow are worlds apart in terms of their culture and the people are different. I'm not saying, you know, I think they both have an amazing culture, I mean, you go through Edinburgh and the first thing you see is the skyline and you're like, wow, this is amazing, it's an amazing city. But there's definitely a difference there. So, Glasgow, I think, contributes something really special to Scotland. It's a massive contributor to Scottish culture. I think, you know, across things like, you know, the humour, the dry humour. I think the kinda working class traditions, you know, I hate to say it, but football, drink, and there again, they are things that you find in Liverpool and places like that. You know, it's quite, it's quite stark. Some of the similarities that you find in big industrial cities. And you find it in Dundee as well. So I think that's what Glasgow contributes to Scotland. If you even think about the arts and art itself, I think in Edinburgh, or certainly to a certain extent, art is viewed as what's to fine arts and everything has to be, you know, beautiful oil paintings and actually the galleries kind of, you know, I know there's the modern gallery but I think in general there's a kind of more of a, maybe a less open view to what art can be, you know. I think it can feel a bit more intimidating maybe? I mean with my art I just do what I want to do. I reflect what's around me, that's it. And everything I do, it comes from an authentic experience. So, every painting I've done pretty much comes from things I've seen or things I've imagined off the back of things that have been around me when I've been growing up.

35

Keira: Yeah, that was one of my questions as well. I have wrote, why Neds and what makes that such a standout part of Glasgow to you?

Ashley: Well, so for me, so growing up in Glasgow, so I grew up in Baillieston.

Keira: Oh did you? I’m from Tollcross! but I went to St Francis of Assisi Primary School…