BRINGING DYNAMISM TO THE MEDIA FACILITY

DARTH FADER

Capturing the sound of Andor

EXCESS ALL AREAS

Behind the scenes at Eurovision 2025

DARTH FADER

Capturing the sound of Andor

EXCESS ALL AREAS

Behind the scenes at Eurovision 2025

id you know that 2025 is a year of major milestones for the TV industry? I’ll be honest, until I started researching it, I didn’t either. But actually, there’s a remarkable number!

The very first successful transmission of a moving, tonal-range television image was achieved by Scottish inventor John Logie Baird on 2nd October 1925. The following year, he demonstrated his invention in public for the first time. Just over a decade later, the BBC launched the world’s first regular television service from Alexandra Palace in London in November 1936.

Fast forward to 1950, and public service media companies across Europe come together to launch the European Broadcasting Union, the successor to the International Broadcasting Union, which itself celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2025. Also in 1950, the BBC broadcast Andy Pandy for the very first time, marking the start of decades of children’s programming (more on that shortly).

Plus, in 2025 we also celebrate 70 years of Independent Television in the UK, 65 years of Coronation Street, EastEnders’ 40th anniversary, and 30 years of Hollyoaks. Plus, CBBC turns 40, and it’s four decades since Live Aid (still an incredible feat when you think about the technology available back in the mid-80s).

All of this just goes to show the rich heritage of the industry that we are all incredibly lucky to be a part of. It also proves the durability of this industry, how it is able to adapt and adopt new ideas, because it wouldn’t have lasted 100 years without being able to do that.

Nowadays, ‘television’ incorporates both traditional broadcasters with modern streaming services, and as we go further into TV’s second 100 years, I wonder how the balance will shift towards streaming (probably quite a lot), But fundamentally, the ‘box in the corner’ is still a huge part of all of our lives. And long may it continue!

JENNY PRIESTLEY, CONTENT DIRECTOR

jenny.priestley@futurenet.com

X.com: TVBEUROPE / Facebook: TVBEUROPE1 Bluesky: TVBEUROPE.COM

Content Director: Jenny Priestley jenny.priestley@futurenet.com

Senior Content Writer: Matthew Corrigan matthew.corrigan@futurenet.com

Graphic Designers: Cliff Newman, Steve Mumby

Production Manager: Nicole Schilling

Contributors: David Davies, Kevin Emmott

Cover image: Getty Images

Publisher TVBEurope/TV Tech, B2B Tech: Joseph Palombo joseph.palombo@futurenet.com

Account Director: Hayley Brailey-Woolfson hayley.braileywoolfson@futurenet.com

SUBSCRIBER CUSTOMER

To subscribe, change your address, or check on your current account status, go to www.tvbeurope.com/subscribe

Digital editions of the magazine are available to view on ISSUU.com Recent back issues of the printed edition may be available please contact customerservice@futurenet.com for more information.

TVBE is available for licensing. Contact the Licensing team to discuss partnership opportunities. Head of Print Licensing Rachel Shaw licensing@futurenet.com

SVP, MD, B2B Amanda Darman-Allen

VP, Global Head of Content, B2B Carmel King MD, Content, Broadcast Tech Paul McLane

Global Head of Sales, B2B Tom Sikes

Managing VP of Sales, B2B Tech Adam Goldstein VP, Global Head of Strategy & Ops, B2B Allison Markert VP, Product & Marketing, B2B Andrew Buchholz

Head of Production US & UK Mark Constance

Head of Design, B2B Nicole Cobban

08 A smarter approach to cloud adoption

By Simon Clarke, chief technology officer at Telestream

11 A dynamic image of broadcast’s future

David Davies explores how the EBU’s Media eXchange Layer standardises media processing functions allowing exchange of data in a containerised environment

14 Excess all areas

Matthew Corrigan visited Basel to find out how the Eurovision Song Contest’s official media services provider NEP Europe prepared to bring the event to a worldwide audience

20 Focusing on the future

Jenny Priestley sits down with IBC CEO Mike Crimp to hear how IBC2025 is driving innovation and collaboration

24 The more things change…

In the first of an occasional column, Matthew Corrigan has some thoughts on the pace of change in the world of broadcast technology

30 Creating the audible wow factor

Frank Foti, executive chairman at Telos Alliance, talks to Jenny Priestley about his work to revolutionise audio with an upmixing technology that transforms stereo into immersive 5.1 surround sound

34 The view from above

V2AIR’s Dr Daniel Guffarth explains how the company’s automated aerial orchestration solution is transforming drone-filmed sports broadcasting

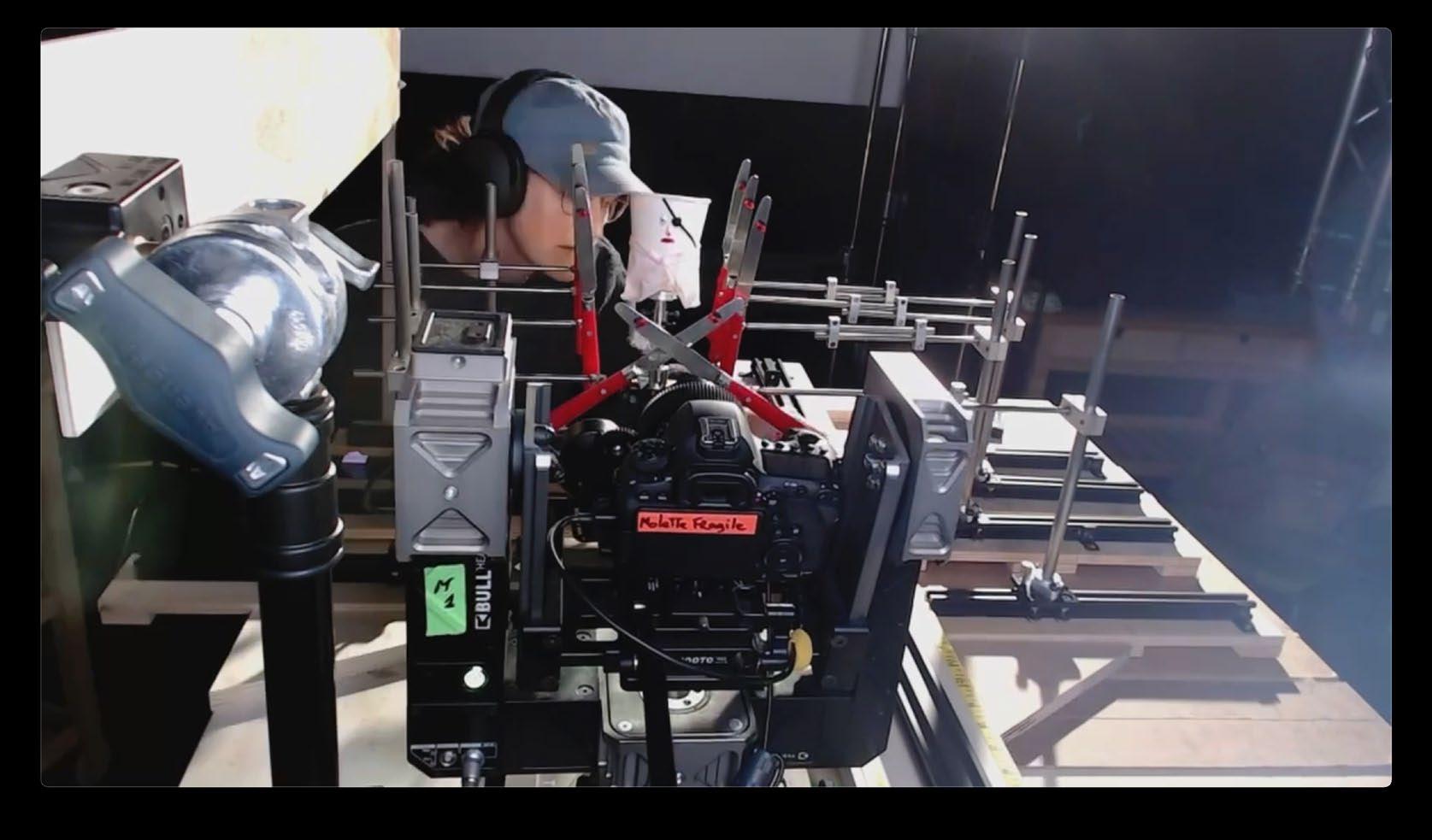

38 Darth faders: capturing the sound of Andor

Kevin Emmott meets Andor’s production sound mixer Nadine Richardson to discover how its intergalactic sounds are created and captured

44 Driving efficiencies with the cloud

BBC Studios’ Emma Ellis explains the decision behind the company’s recent move to the cloud

By Golan Simani, director of cloud operations at TAG Video Systems

As cloud technology continues to transform modern broadcasting, success depends not only on migration but also on the strategic decisions made once operations are moved to the cloud. The goal is not simply technical execution, but long-term efficiency, cost control, and agility across every stage of the media supply chain. The cloud’s real value lies in how efficiently organisations can scale, control costs, simplify operations, and prepare their infrastructure for the future.

This requires broadcasters to shift from static, hardware-centric thinking to dynamic, software-defined architectures built for realtime agility, data-driven optimisation, and financial predictability. The following strategies offer a clear framework for building smarter, optimised, and highly sustainable cloud video workflows.

1. Architect for flexibility, not permanence

Unlike traditional infrastructures, cloud environments allow broadcasters to allocate resources on demand globally. This flexibility is essential for handling fluctuating demand, whether scaling up for live events, breaking news, or special productions—and scaling down afterward to avoid idle resources.

Cloud-agnostic design further enhances this flexibility by enabling broadcasters to operate seamlessly across various platforms. This multi-cloud approach helps optimise pricing, redundancy, and availability without being locked into a single provider.

2. Streamline complex workflows to minimise compute waste

In cloud-based operations, complexity drives up both cost and risk. Every additional format conversion, redundant encoding step, or unnecessary transcoding task increases compute consumption, storage use, and network overhead. Simplifying streaming architecture means designing end-to-end workflows with the right media services that handle multiple formats natively, minimising transformation points wherever possible. Cloud infrastructures should efficiently process ABR (HLS/DASH), MPEG-TS, SCTE, and ST 2110 within a single framework, eliminating processing layers that are avoidable.

3. Use Monitoring data for continuous optimisation

Real time operational data offers broadcasters a powerful tool for ongoing optimisation. Beyond simply detecting failures, monitoring data provides actionable insights into stream performance, network health, and resource utilisation.

Analysing these trends allows teams to fine-tune auto-scaling policies, adjust redundancy strategies, and distribute workloads more efficiently across cloud regions. Over time, these optimisations translate into stronger service stability and tighter financial control.

4. Designing for cost predictability in the cloud

Cloud migration reshapes spending patterns. Without deliberate planning, costs can quickly rise due to overprovisioned resources, excessive data transfers, and unmanaged storage. Achieving cost predictability starts with precise resource planning.

Key tactics include:

• Right-sizing: Choose instance types that fit actual workload needs to avoid waste.

• Storage lifecycle management: Apply policies that align storage costs with data usage stages.

• Workflow efficiency: Eliminate redundant processing across media services.

• Limit push data: Reduce unnecessary outbound transfers to control egress fees.

Cloud providers offer a wide range of configurations, so aligning them with specific operational needs is essential for sustainable cost management. Poor mapping can lead to long-term inefficiencies.

5. Automate operations to enable scalable growth

As cloud video ecosystems become more complex, manual management becomes both inefficient and unsustainable. Automation enables broadcasters to orchestrate complex deployments, monitor operations, and dynamically adjust resources with minimal direct intervention.

Using infrastructure-as-code tools such as Terraform, CloudFormation, and Helm, entire video workflows, from encoding to distribution and monitoring, can be deployed, updated, or decommissioned quickly and consistently. This level of automation is particularly valuable for temporary or event-driven workflows, where entire environments may only need to operate for hours or days.

Cloud-native video architecture offers enormous potential, but only when approached strategically. By focusing on flexibility, workflow simplification, real time data optimisation, proactive cost management, and operational automation, broadcasters can transform their video operations into scalable, efficient, and financially sustainable systems.

By Henry Goodman, director of product management, Calrec

Over the years, the broadcast industry has thrived on the adoption of new technologies. However, never has the introduction of technology presented such a quantum level of change in the fundamental business models across the media industry as now.

We have already seen the impact of cloud-based streaming technology on the distribution and delivery of media content with significant shifts in not only how people consume media content but also to the fundamental financial models the industry is built on.

As technology shifts go, the adoption of cloud-based resources for live TV production has the potential to re-model businesses across the industry from manufacturers to content creators and traditional broadcasters. The disruptive nature of IP and cloudbased technologies makes it more important than ever for us all to ask how the implementation of these technologies will impact the value proposition we offer.

I am as big an advocate of cloud resources being used in live media production as anyone, but whenever someone tells me they want to use cloud resources, one of the first questions I ask is, why? As with all significant technology shifts in business, understanding and weighing the benefit to cost equation is key to a successful implementation and should not be taken lightly.

Significant investment in development time and money has already been made by manufacturers, system integrators, facilities providers, content creators and broadcasters, most of whom have taken a long-term view of the business case and return on investment. In contrast to the flexibility it provides, developing and enabling cloud resources for broadcast production should be anything but whimsical.

The shape of how cloud processing will be utilised in live production broadcast workflows is still being honed, but the key tangible benefits of a cloud-based infrastructure are clear and offer exciting prospects.

In a word, cloud production resources provide “agility”, both in terms of when and where they are deployed but also from a management and cost point of view.

Agility is money

Cloud broadcast production allows for rapid deployment of resources, making it feasible to produce content with minimal

notice or even “on-a-whim”. This is achieved through cloud-based infrastructure that can be spun up or down in minutes, compared to the weeks or months required for traditional setups. This agility enables broadcasters to quickly adapt to changing demands, seize opportunities and even experiment to expand their audiences. It also drives down cost. The traditional model of buying enough processing for your biggest event of the year is redundant when a virtualised DSP engine can deliver the audio quality and feature set in a cloud-native environment.

Also, by their very nature, cloud production resources can be deployed where you need them, whether this is in a public cloud or on dedicated on-premise hardware. Especially relevant to live sports coverage, the flexibility to geographically place resources without the need to transport much hardware can make the difference between covering an event or not.

A key facet of cloud production resources is that they can be scaled to cope with peaks and troughs of production demands. This allows management of both ground and cloud facilities to utilise the equipment and human resources available. The ability to supplement existing ground-based equipment by leaning into cloud resources, as and when demand requires, to boost the processing resources you have for a specific event is a key cloud use case.

Alongside remote-control technologies like Calrec’s True Control 2.0, cloud-based production facilitates remote collaboration among production teams, enabling broadcasters to maximise the usage of their talent and equipment resources from anywhere in the world.

One of the key financial drivers for cloud production is the ability to attribute costs to a specific production or event, allowing content producers and facility providers to move away from the traditional capex models. Certainly, for coverage of live sports events of limited time duration, the ability to licence cloud resources and use them when and where they are required has obvious financial and management advantages.

In summary, like any other technology implementation, creating a cloud-based broadcast production environment should be considered and planned with care. The agility cloud technology provides means broadcasters can utilise live production resources with efficiency and flexibility, even “on-a-whim”.

By Simon Clarke, chief technology officer, Telestream

Cloud technology is redefining media and entertainment (M&E) operations, offering new possibilities for scalability, collaboration, and efficiency. However, cloud adoption is not without complexities. Shifting to the cloud demands a nuanced, strategic approach to manage massive file sizes, strict security needs, and unpredictable workflows.

A 2025 report by Haivision reveals that while 86 per cent of broadcasters use some cloud-based technology, only 2 per cent have fully transitioned to the cloud. Notably, half now employ hybrid workflows, combining SDI, IP, and cloud technologies.

This is why the conversation is evolving from a “cloud-first” mindset to “cloud-smart” strategies. While cloud-first emphasises comprehensive migration, a cloud-smart strategy advocates for balanced, deliberate decision-making.

What is a cloud-smart approach?

Unlike wholesale cloud migration, cloud-smart is all about prioritisation. Organisations identify where the cloud adds the most value while retaining certain workflows on-premises or in hybrid environments. This ensures that transitions are efficient and aligned with operational objectives and budgetary constraints. This often means leveraging cloud scalability for distribution, analytics, and disaster recovery while keeping post production, rendering, and realtime processes on-premises for performance and cost control.

Why cloud-first doesn’t always work for M&E

M&E’s unique demands make cloud-first strategies challenging. Media companies often face multiple roadblocks, such as massive fies, legacy infrastructure, volatile costs, integration complexity and global collaboration challenges.

Instead of treating cloud adoption as one-size-fits-all, M&E companies must customise their approach to maximise benefits while circumventing these challenges.

Cloud without compromise: the hybrid advantage

Enter hybrid cloud solutions that leverage both cloud and on-premise environments to balance agility, scalability, and cost efficiency without compromising control. Quick-turn productions or live events are often more efficient with on-prem resources. For example, recording a daily show at 7pm that airs at 10pm leaves no time for cloud uploads. Companies with legacy infrastructure avoid duplicating efforts by

using hybrid setups, running critical processes locally while shifting auxiliary tasks to the cloud. Productions needing scalability during peak periods can tap hybrid models without long-term financial commitments. An added bonus: hybrid cloud provides an average of 24 per cent cost savings compared to traditional infrastructure.

Simplification and strategic planning

One of the biggest hurdles for media companies is operational complexity. Multiple cloud providers and fragmented infrastructures often creates inefficiencies.

To address this, organisations are turning toward solutions prioritising simplification and seamless integration. Two trends drive this shift.

First, a decoupled architecture allows workflows to operate as smaller, independent services to increase efficiency. However, this can create organisational complexity unless integrated solutions are chosen. A key benefit of cloud-native solutions is faster deployment and iteration. By contrast, lift-and-shift doesn’t change the application architecture, so updates and deployments remain slow and manual.

The second trend is unified platforms. Partnering with cloud providers that offer first-party integration and out-of-the-box functionality can eliminate fragmented workflows, reducing manual configurations. Cloud-native solutions that support DevOps, CI/CD pipelines, and infrastructure-as-code make rapid updates and feature releases seamless.

The cloud is often marketed as the ultimate simplification tool. While cloud can indeed unlock efficiency, businesses must often manage an overwhelming number of vendors and systems.

Rather than delivering simplicity, fragmented ecosystems can compound operational challenges. This highlights the importance of custom cloud strategies, particularly for large networks, streaming platforms, and production companies tasked with juggling agility, security, and cost management.

Adopting cloud technology is no longer a question of “if,” but “how.” Transitioning to a cloud-smart framework is an imperative to scale while remaining cost-effective and operationally sound.

By adopting hybrid models to simplify infrastructure, enterprises can mitigate complexity and make technology work for their operational needs. The future is hybrid, and it starts with “smart.”

TVBEurope’s newsletter is your free resource for exclusive news, features and information about our industry. Here are some featured articles from the last few weeks…

Jim

CLEAR ANGLE STUDIOS PUTS F1: THE MOVIE IN POLE POSITION

Technical operations manager Marco Lee details the many challenges involved in

the

and

environment,

OPINION: IS VVC READY FOR PRIME TIME?

Justin Ridge, principal engineer at Nokia and president of the Media Coding Industry Forum, reports on the current state of play with Versatile Video Coding (VVC) and its adoption across the media and entertainment space.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

WARNER BROS DISCOVERY CONFIRMS IT WILL SPLIT IN TWO The separation is expected to be completed by mid-2026, subject to closing and other conditions.

NOT SIGNED UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER? YOU CAN SUBSCRIBE FOR FREE VIA THIS QR CODE

The Media eXchange Layer (MXL) standardises how media processing functions operating in containerised environments can share and exchange data with each other, writes David Davies

How best to optimise the use of technology in the containerised media production environments that are now emerging is on the mind of many broadcast vendors and organisations these days, including the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). Beginning with a white paper in April 2023, the EBU has been developing an initiative, Dynamic Media Facility (DMF), which fosuses on exploring how future media productions can benefit from “highly flexible and dynamic technology approaches”.

A central aim of the project is the development of a Reference Architecture that offers a structured framework for users to express and evaluate their requirements using common models, interfaces and terminology. The intention is that this will help guide the adoption of relevant technologies and practices from the broader IT landscape, while also highlighting areas where alignment on shared solutions can reduce redundant effort and remove barriers to flexibility— ultimately allowing the media industry to focus on what really adds value to its products.

There are many facets to the DMF project, but in recent weeks, the EBU has announced that one of the “key enablers” has reached fruition. The Media

eXchange Layer (MXL) is a code package that standardises how media processing functions in virtualised environments can share and exchange data with each other. Essentially providing the “virtualised cabling”, MXL will facilitate the DMF vision of supplanting individual hardware boxes with virtual containers running on local servers or, as is becoming increasingly habitual, the cloud.

The first conversations about the project that became DMF took place three years ago at an EBU meeting in Brussels. “We had this bow-tie diagram with the media function as the dot and everything in the wings,” recalls Willem Vermost, senior media technology architect at the EBU. “We realised that a lot of time is spent discussing metadata schemes and various specific details, but they may not bring a lot of value. Instead, the value is actually when you change your media, and that [stems from] the media function. So we saw that if you look at it from a very granular point of view, and

“It was agreed upon that the media exchange layer was the first thing that would bring the greatest value to everyone”

WILLEM VERMOST, EBU

you then start connecting those bubbles as a graph, you can create a process flow which serves as your media workflow.”

There was also a recognition that lessons could be learned from the adoption of SMPTE ST 2110. “When people started to build their own 2110 stacks, including the packet pacing [regulating the rate at which data packets are sent to avoid network congestion and enhance performance], you had to do a lot of interoperability tests before you could be sure that everybody was compatible,” says Vermost. “But if you had all these media functions running in a compute exchanging media with each other through one shared SDK, you wouldn’t have to do interoperability testing on this layer anymore—saving a lot time and money.”

Ultimately, it was determined that the reference architecture would need to comprise “three major blocks: one at the bottom which talks about IT architectures that we’re not allowed to touch because this is what we want to get from the IT industry; the layers on top which are essentially the media infrastructure; and then a third block which includes the aspects that cut across all the layers, such as discovery, monitoring and security.”

The greatest value

A meeting in Geneva in November 2024 was instrumental in determining that MXL should be the next focus of activity. “It was agreed upon that the media exchange layer was the first thing that would bring the greatest value to everyone,” recalls Vermost. “There were also plenty of voices saying that it would only work if it’s open source and everybody can use

it. So the challenge then was to create a community that could write code, within a framework that allowed everyone to work safely.”

Subsequently, a meeting at CBC/Radio-Canada earlier this year led to the Linux Foundation and the North American Broadcasting Association (NABA) becoming closely involved with the development of MXL. Rebecca Hanson, director-general of NABA, recalls: “This project was brought to us by Felix Poulin of the CBC, a member of NABA. He briefed our technical committee numerous times and generated a fair amount of interest. This prompted us to sign an MoU with the EBU regarding how we can support the project, including recruiting North American broadcasters for input.”

As to how NABA hopes MXL will help improve and streamline workflows in the future, Hanson responds: “I think of the greatest interest to NABA members is maximising flexibility and interoperability. This core ‘value’ will provide broadcasters with the ultimate freedom to customise their facilities to their specific needs, and to provide options among vendors.”

Rails for an ecosystem

The resulting code package is now available via Github (link here). In the words of the EBU, it provides “an open framework for real-time ‘in memory’ media exchange that allows seamless integration across compute nodes, production clusters and broadcast platforms. In essence, it is the rails for an ecosystem, and their use is free of charge.”

In terms of the roadmap for MXL, Vermost says that “the charter of this particular project is agreed upon. Within the charter, there’s a technical steering committee—comprising the people who are actually writing the code—that is also tasked with creating a

user requirements committee.” Several workshops and seminars are also on the schedule, after which it is hoped that people will “contribute to the code, look at the code, download the code, and use it.”

In the case of NABA members—most of which are large, multi-station broadcast groups—it seems likely that deployment will occur primarily within cloudbased deployments. “Most are well on their way to moving to the cloud,” says Hanson. “Regarding the DMF/MXL initiative, they are really only starting to get involved now. Since the technical steering committee has completed their initial work and the code is publicly available, now is the time for broadcasters to share their functional requirements ‘wish list’ so that the effort truly works for broadcasters and isn’t purely vendor-driven.”

Whilst MXL is an important part of the DMF project, there are still many other aspects to be addressed, not least connectivity between the virtualised containers. “We need to include at least discovery, registration and connection capabilities; all those things you require to be able to connect your media functions and have them point to the right location in memory to exchange media flows and so on,” says Vermost.

It’s possible that existing specifications from NMOS could provide some of the missing pieces here. “A lot of broadcasters have already invested in NMOS, so there is a logical research stage in looking at NMOS and whether it’s a logical path for us. We need to find out whether it has to be changed [for DMF] or can it be used out of the box? Those are the sort of questions that we’ll be addressing next.”

This core ‘value’ will provide broadcasters with the ultimate freedom to customise their facilities to their specific needs, and to provide options among vendors” REBECCA HANSON, NABA

There are also plans for extensive documentation, including use cases that will benefit from a DMF approach, and a high-level model for the lifecycle of media workloads as part of the Reference Architecture. But although it’s relatively early days, Vermost says there have already been broader hints that the initiative is on the right track.

“I was at an event before NAB and one of the things that was being discussed a lot [among delegates] was DMF, which completely blew my mind,” he admits. “But it did seem to be a vibrant topic already at NAB, and now with what we have announced and are planning, we hope that will continue into IBC.”

To access the full archive of EBU white papers and publications, including those related to DMF and MXL, visit www.ebu.ch/home

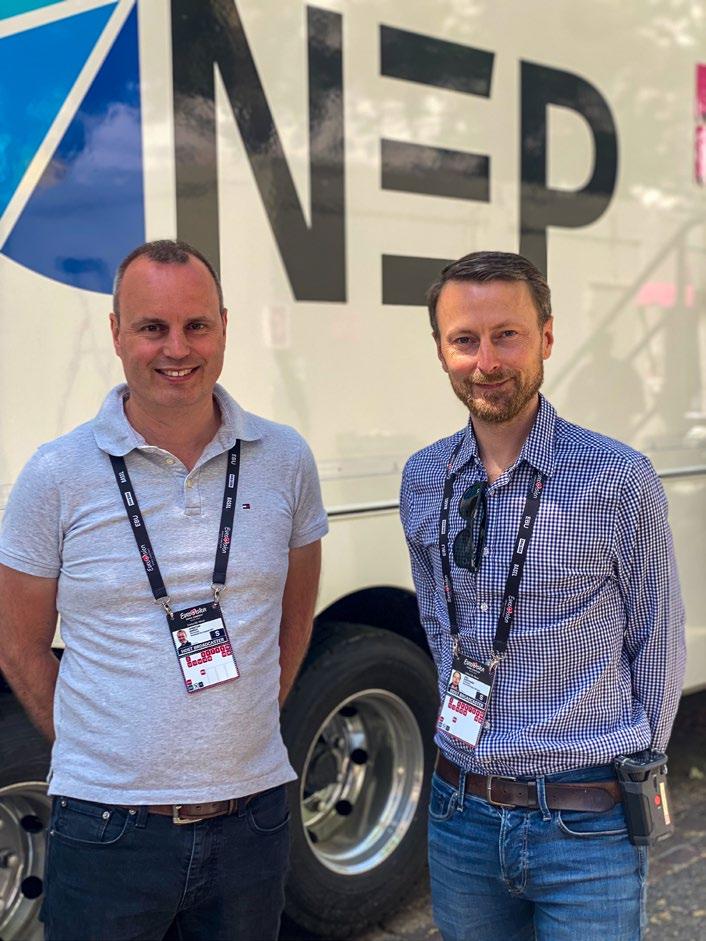

Matthew Corrigan visits Basel to see how the Eurovision Song Contest’s official media services provider NEP Europe prepared to bring the event to a massive global audience

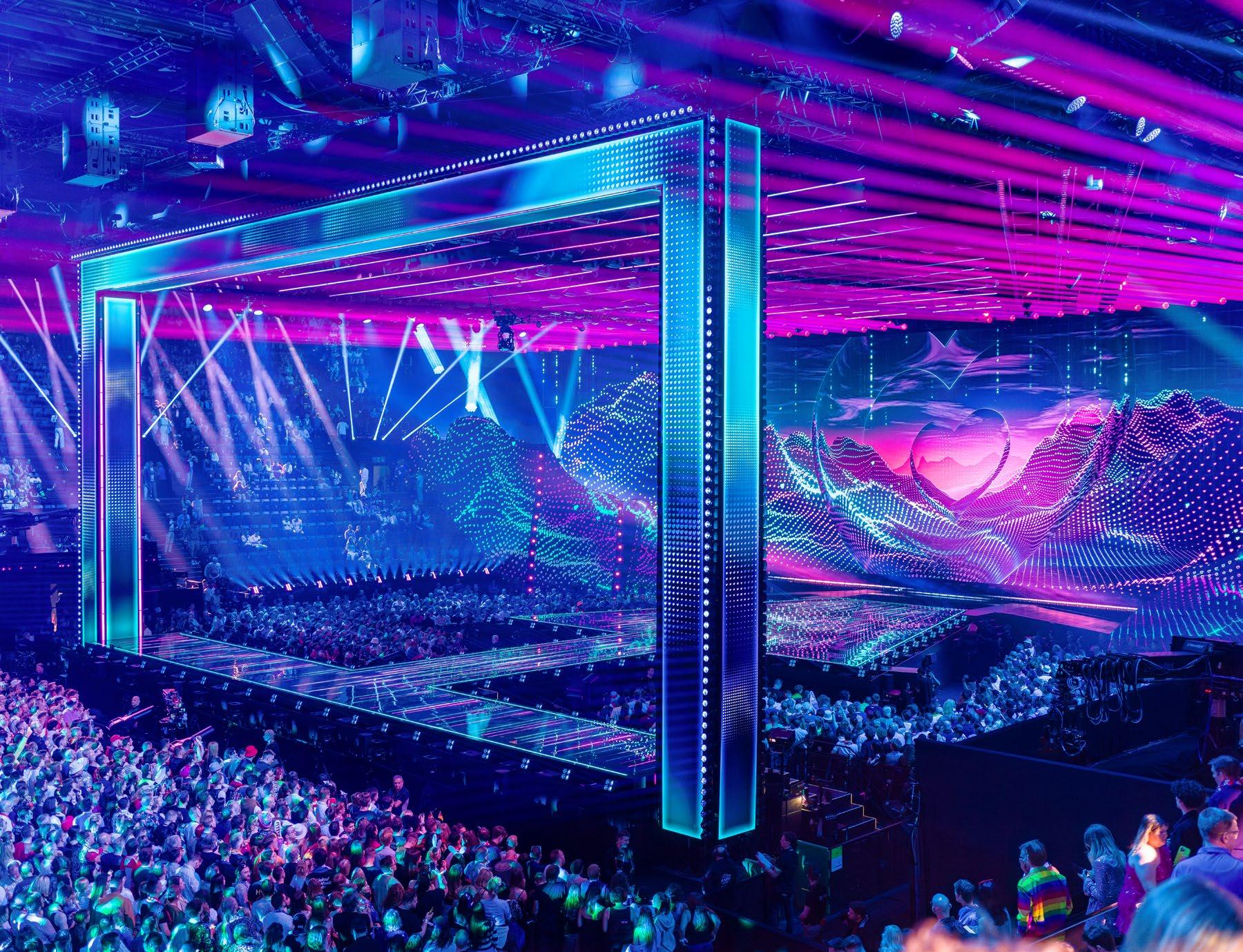

The Eurovision Song Contest has long topped the tables in terms of excessive performance. Every edition of the international extravaganza features a fresh line-up of flamboyantly costumed hopefuls, each apparently determined to upstage their fellow contestants in an event that grows more dazzling by the year. Yet no matter how elaborate the productions on stage may be, they can never match the sophistication of what takes place behind the scenes, as an immense broadcast operation ensures the competition is seamlessly delivered to a worldwide audience that this year reached a record-breaking 166 million viewers.

Nestling in the north-western corner of Switzerland, the city of Basel, where the Rhine forms a three-way border with Germany and France, hosted Eurovision 2025. Swiss national broadcaster SRG SSR produced the coverage, in collaboration with, as ever, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). For the sixth consecutive year, NEP Europe took on the role of official media services provider to Eurovision, having once again won the necessary tendering process.

Planning began in earnest in December, explains Axel Engström, sales lead from NEP Sweden and Eurovision project manager, and COO of NEP Switzerland and Eurovision project lead, Christian Kosek, with a core of around 25 highly experienced crew members arriving

on location five weeks ahead of the event. The company was able to call in resources from across the continent, with the team coming from Sweden, Finland, the UK, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and, of course, Switzerland and quickly rekindling the excellent working relationship that allows them to handle whatever challenges the occasion can throw at them. Over the years, Eurovision has developed a reputation for being predictably unpredictable. “We try to keep the same people involved,” says Engström. “We really come together as a group.”

In the days ahead of the competition, Basel went Eurovision crazy. The hotels, cafes and bars were filled with revellers and the fan zones packed with people enjoying an apparently endless stream of free concerts. The venue for the event itself was the 12,400 capacity St. Jakobshalle arena, just across the tram tracks from the towering edifice of St. Jakob-Park, home to the FC Basel football team. Security was visibly tight. Entry for spectators was strictly controlled with a separate layer to reach the backstage area. Another, unseen element that has become essential in protecting the contest is cybersecurity—reflecting both its inevitable politicisation and vulnerability as a massive, open, prestigious event.

Behind the venue, beyond the gaze of the lengthy

queues of excited fans, a maze of temporary cabins were erected, creating a busy hive of activity as technicians bent over their myriad screens. Two huge NEP trucks were parked alongside, UHD2 and UHD24. “We have two big OB vans on site,” says Engström “One main unit and one backup unit and the reason for that is [the contest] is such a big, high priority event for EBU, with lots of viewers, and it’s really important that we can always broadcast the show, whatever happens.”

Redundancy is a huge consideration, with backups built in everywhere. The trucks have their own power supply, able to continue even in the event of a catastrophic failure. “Basel can go black,” says Koseck, “but the Eurovision Song Contest will continue.”

A third vehicle was parked in front of the others, there to satisfy a request from broadcaster SRG, as Engström explains: “That was a new one for us. In the past, we have tried to do it all in one audio control room but this year they asked for separate music. We have our Music 1 truck with a console where we do the music mix and then we feed into the OB van where we add on the final broadcast with the host microphones etc.”

Underpinning it all was NEP’s TFC Broadcast Control platform. Flexible and scalable to demand, TFC’s (Total Facility Control) software-led infrastructure management solution was a game changer for the team this year. Tried and tested at some of the biggest live event productions in the world, including last summer’s Paris Olympic Games, TFC provided SMPTE ST 2110-based centralised signal management and control across the entire ecosystem. Set-up times were significantly reduced and operations streamlined throughout, with continuous signal monitoring ensuring any problems could be quickly and effectively resolved.

“We need to distribute all the signals between the venue and be able to switch OB trucks,” Engström comments.”Everything passes through the technical operations centre on site. In the cabin where we handle all this infrastructure, the heart of the system is built on our own product, TFC. It’s like a big router, a totally IP-based control system.”

TFC is completely vendor agnostic, ensuring interoperability between all the devices and systems in use by each broadcaster. “It manages all of the 2110 streams between the different users,” explains Koseck. Everyone at NEP is keen to praise the operational partners with which they have built excellent, almost

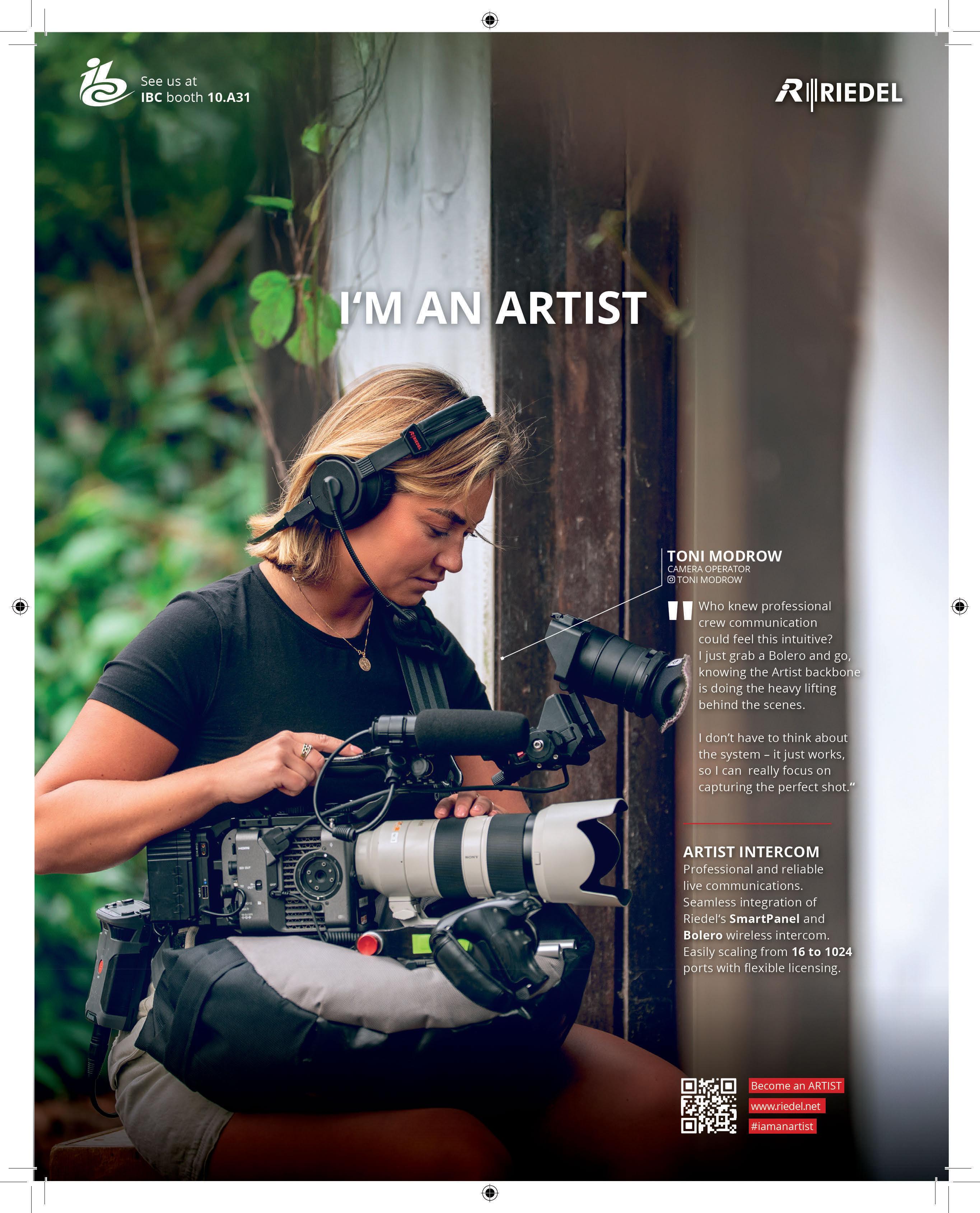

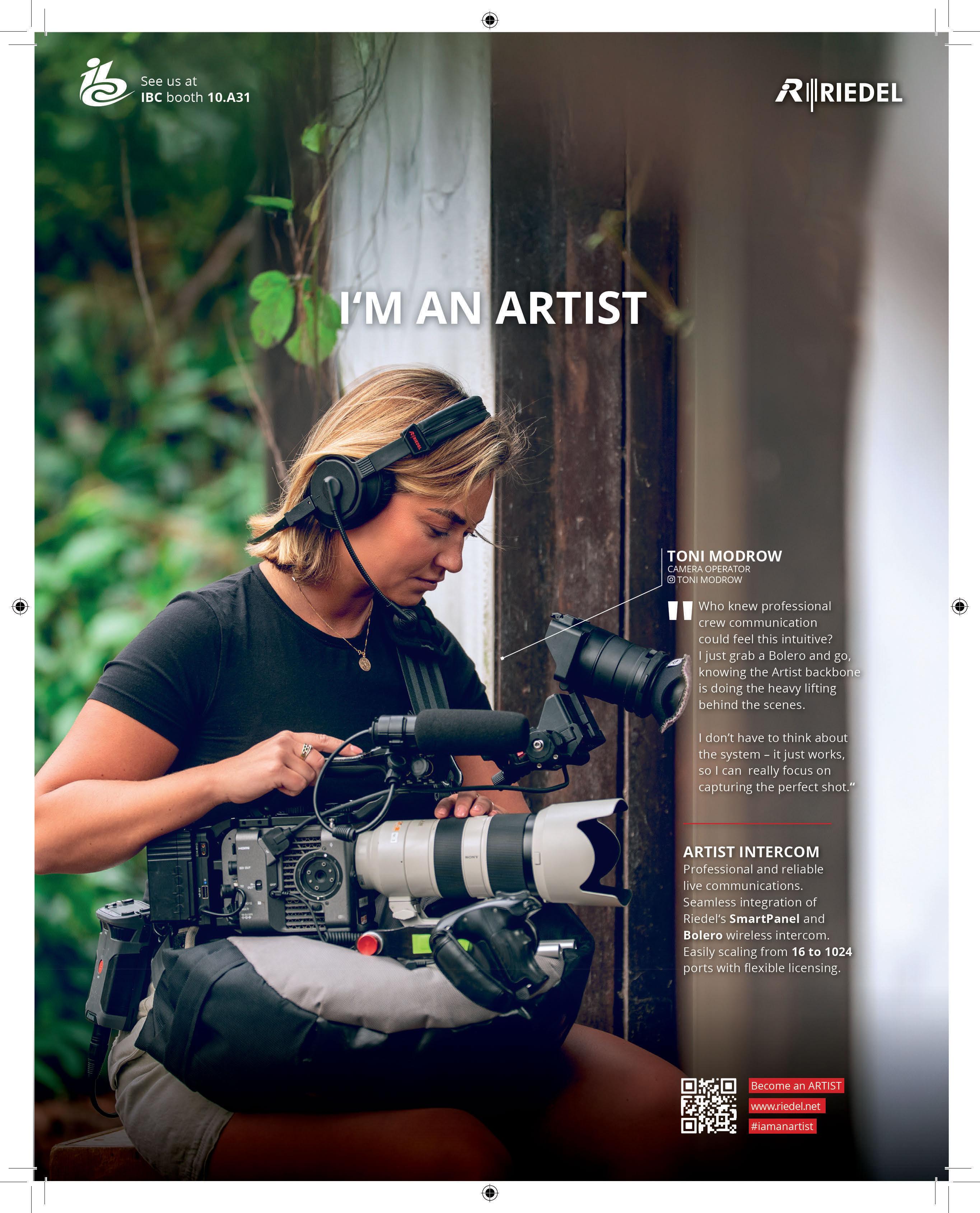

symbiotic relationships over the years. Riedel Communications, for example, provide intercom services for the entire event, meaning their operations are intrinsically linked. “We work really closely with them, there’s a long, good relationship,” says Koseck.

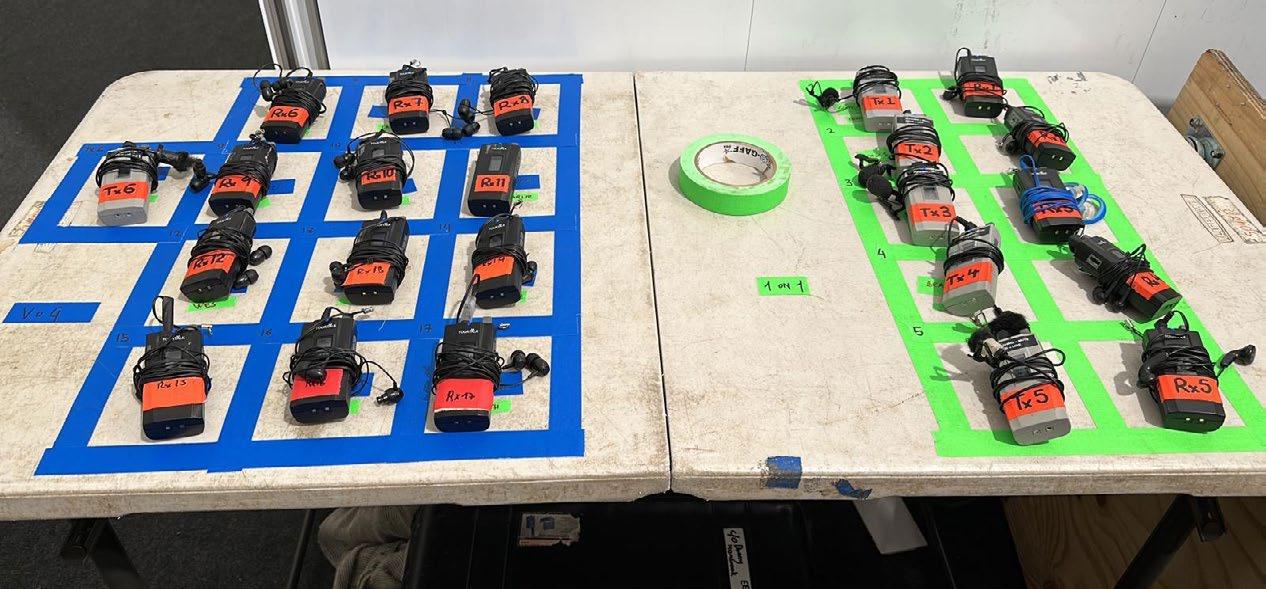

“They are supplying the equipment but we, as engineers, are supporting the intercom setup and settings and handling signal distribution,” adds Engström. In all, Riedel supplied some 230 Bolero units and more than 400 walkie-talkies for use by the engineering and creative crews—another huge number on Eurovision’s logistical ledger.

Dominating the St. Jakobshalle stage was a huge rectangular arch consisting of a number of LED panels which itself formed part of the supporting structure for additional stage elements such as lighting rigs. A Black Marble BM4 LED floor, Vanish V8T transparent LED panels and Graphite 2.6 indoor LED displays provided the creative teams with a vast range of options, bringing every performance to life in a dazzling display of visual exuberance. As in previous years, Augmented Reality (AR) enabled the producers to transition seamlessly from events on the stage to additional content, “This time, it is used much more modestly but effectively,” Engström reveals.

NEP deployed a total of 27 cameras including 6 wireless RF cameras, 2 spider cameras, 3 Steadicams and a railcam mounted to sweep across the front of the stage. While more are often in place for sporting events, Eurovision is fairly unique in that all of the

cameras are actually used during performances. Four EVS live production servers were deployed and more than 320 monitors were in use across the location.

As the crews busily prepared for the evening ahead, an air of calm competence radiated through the cabins, vehicles and technical areas in the hall. This was a thoroughly efficient operation run by a team that was really on top of its game. It was patently obvious that everyone was working in harmony and their determination to succeed was palpable. Engström sums it up perfectly, and in doing so, captures something of the spirit of Eurovision: “The execution of a production of this magnitude is only possible thanks to the tremendous teamwork of everyone involved. From logistics and technology to onsite operations, it was a true cross-border collaboration between our NEP teams in Europe.

By Christian Scheck, head of marketing content, Lawo

hese days, few people in the broadcast and pro AV industries are wary of the cloud. Outfits are either already using it or at least toying with the idea. The reason is simple: less equipment needs to go on-site and the same instances can be used almost back-to-back. Most broadcasters have been familiar with a distinction that may, or may not, change everything: on one hand, there is the so-called “public” cloud provided by universally known tech firms; on the other, there is the “private” cloud that is only accessible to carefully selected operators.

While it still happens that users of a public cloud service are taken aback by unexpected costs that adversely affect a budget everybody thought was fixed, the public cloud has its uses. Especially for essences that only leave the virtual realm after all processing has been completed. Nor is the public cloud just an American affair anymore: even respected host broadcasters have been shopping around for cloud services in other countries, whether for political or other reasons.

Some outfits have been working with data centres in different locations—i.e. private clouds—because privacy and redundancy are high on their list. Such data centres host both dedicated hardware and a growing number of generic servers that run processing and utility apps. All authorised operators, anywhere in the world, can access these processing pools over dark fibre ST 2110 lines, using SRT, WebRTC, etc.

Networks built around one or several data centres belong to an entity that has a vested interest in keeping everything humming, while keeping would-be intruders out to avoid content theft, interference with operations, and so on. With growing security concerns, a lot is being done by manufacturers of broadcast and pro AV solutions to protect both the solutions and essences in accordance with the EBU’s R143 recommendation and similar initiatives. As a result, private clouds,

“A hybrid mix of public and private cloud is possible because not all broadcast or pro AV processing tasks are created equal”

especially of the redundant ST2022-7 type, where issues at one data centre are mitigated by diverting traffic to the other, are a serious alternative to a public cloud.

A hybrid mix of public and private is also possible because not all broadcast or pro AV processing tasks are created equal. Those that do require a lot of essence transfers are best kept in a private cloud, for instance. In situations where 20 or more locations in and beyond Europe contribute to the same production, working through a public cloud might seem attractive, yet the ones using this workflow still favour a private cloud approach. This may change, of course, as the number of reasonable objections dwindles, yet redundancy implicitly means that route B is in no way related to route A. How would one handle redundancy between two public cloud providers, for instance, and what would be the cost?

Processing solutions like HOME Apps that are based on containerised microservices work equally well on generic servers both on-prem and in a public cloud. This is thanks to their all-new architecture. Despite their instantly familiar user experience, no preexisting code has been lifted from pre-existing hardware and shifted to a server or cloud as is. Such processing apps scale exceptionally well as the bare metal (or public cloud service) they run on evolves to provide ever more computing heft and bandwidth.

The open-source Media Exchange Layer (MXL) initiative proposed by the EBU looks set to become yet another major breakthrough. It relies on the ability of processing apps from various manufacturers to exchange essences on a shared-memory plane. This avoids unnecessary latency while hopping from one app to the next. Obviously, this is first and foremost a CPU/GPU topic, and the server farms operated by public cloud providers are full of them. Nevertheless, the first attempt to make this work will likely be in a private cloud. There is still some work to do to ensure that all apps by carefully selected vendors play together as expected, but the project looks very promising.

The decision between a private and a public cloud may also be related to scale. Starting with a private cloud, initially on-premise, may be a good first step. As the outfit expands, the HOME management platform and VSM control system are able to organise geographically distributed data centres and processing pools in such a way that there is no noticeable difference with a public cloud. Even latency is staggeringly low. Adding public cloud services is possible along the way. So, it all comes down to flavour, it would seem.

for any trade show, innovation is key. An exhibition and conference will always attract visitors, but what keeps them coming back year after year is the ability to see something new. The team at IBC have made this central to their planning for this year’s show.

In recent years, IBC has been reflecting the ongoing changes in the media and entertainment industry, introducing three central pillars across the whole show: innovative technology, changing business models, and people and purpose. As the industry faces numerous challenges, such as the macro environment or trade tariffs, the theme of IBC2025 is ‘Shaping the Future’.

“We felt that where IBC has always been successful is bringing people together to be able to actually see technology, talk about technology, experience it and move the debate forward,” explains IBC CEO Mike Crimp. “So this year, the overall theme is really about shaping the future at a time of dynamic change.”

Crimp hopes IBC2025 will be a collaborative environment where the industry can thoroughly examine not only new technologies but also innovative ideas. He believes broadcasters and vendors are eager to work together in this way, and IBC has a strong reputation for enabling such interactions.

Doing things differently

One of the biggest disruptors within the industry right now is generative artificial intelligence. This is leading to new entrants in the vendor space, bringing products and services that aren’t just applicable to the media and entertainment industry, but to other markets.

“It’s something that IBC had seen for a while, and we’ve tracked that through our ‘Content Everywhere’ experience,” says Crimp.

“We’ve seen at other shows, such as Mobile World Congress, how they can serve different verticals. So in terms of finding these companies, we’ve been much more, shall we say, hunter-gatherer than we perhaps were before.”

This move will be reflected within the new Future Tech Zone in Hall 14, where attendees can meet companies that they may not be familiar with. “We’ve almost seen it become a trend where people come to IBC and have quite a lot of interaction discussing what they found in the corner or down the alley or in the

Crimp sees these opportunities as a way for IBC itself to be disruptive and lead to things “being done differently”, enabling companies that haven’t traditionally exhibited at the show to enter the media and entertainment market.

“IBC2025 isn’t the old school trade show where you kind of lean on your stand and wait for someone to come past. It’s not just buyer/seller, the whole value chain has to interact with each other. We tried to embrace that as much as possible by creating things that people would think about rather than just receiving information.”

There’s always plenty to see at IBC Show, not least the conference, which takes place alongside the exhibition. Without giving anything away, Crimp promises this year will cover a “wide church of content and sessions” with senior executives discussing some of the industry’s current themes.

“We’ve kind of stirred that up with some more creative people and some people who might just want to challenge the conventional view,” he adds.

Other key features include the Innovation Awards, celebrating industry advances in five categories, such as content creation, social impact, and environment and sustainability.

Winners will be revealed on the Sunday of the show.

The IBC Accelerator Media Innovation Programme has continued to grow since its introduction in 2019. It offers both vendors and their customers the opportunity to work together in the creation and design of a service, whether that be around master cloud control, ultralow latency live streaming at scale or creating a framework for generative artificial intelligence, as featured in some of this year’s projects.

“What’s happened is that the vendors see it as an opportunity to not sell a finished product, but to get broadcasters and streaming companies invested in that idea, literally invested because sometimes they’re sharing IP,” states Crimp.

“It’s kind of moved into being something of a ‘club’ whereby the CTOs and the vendors work together, and they get together for dinners and meetings and so on. It’s got to the stage where the Accelerator projects almost point the way for the direction that the buying market is looking.”

While the Accelerator programme has proven its worth to the industry, Crimp describes it as a “significant sign” that IBC is also delivering on its promises. “If you look at the sandwich board of brands that are involved, it is enormous. It is so impressive.” Visitors can check out this year’s Accelerators in Hall 14’s Future Tech Zone.

One idea that is being revived for IBC2025 is a Hackathon. The show is teaming up with Google on a challenge that will be revealed to everybody at the same time. Without giving away any details, Crimp describes it as “dead central to the themes happening in the industry at the moment”. Teams are invited to take part in the two-day event, with each invited on stage to pitch their solution and the winners receiving a prize. Crimp sees the Hackathon as an opportunity for IBC to deliver on its ‘people and purpose’ pillar, engaging with the next generation of engineers. “It will be really, really interesting to see if a group of hackers can create what they’re going to be asked to create in two days.

PICTURED ABOVE: The IBC Accelerator Media Innovation Programme offers both vendors and their customers the opportunity to work together in the creation and design of a service

“It will also be in the Future Tech Zone in Hall 14. We want to make that hall a destination, so that people will go in there and be in the right frame of mind to be talking about innovation. I think the Hackathon could be really, really interesting, and something which we might be able to build on for the future. It is one of the things I’m most excited about, because I think it’s going to bring in a bit of a new audience. It’s going to show different ways of solving problems. Again, IBC is using our relationships to stage innovation.”

Essentially, innovation is what IBC2025 is all about. Asked to sum up the show in three words, Crimp says: “Innovation, fun, collaboration.” Roll on September.

Registration for IBC2025 is now open. More details are available here

“IBC2025 isn’t the old school trade show where you kind of lean on your stand and wait for someone to come past. It’s not just buyer/seller, the whole value chain has to interact with each other”

Remote production isn’t just a shift in broadcast workflows—it’s a smarter, faster, and more cost-effective way to produce live content. In a world where speed, scalability, and efficiency define media success, remote production is transforming how content is created, managed, and delivered

With over 20 years of experience in broadcast technology and live production, ATM SYSTEM is a first-class player in the industry—trusted, proven, and deeply rooted in professional broadcasting. Today, the company is setting a new benchmark for how remote production can be efficiently delivered at scale.

From international sporting events to studio shows and digital-first content, ATM SYSTEM enables top-tier productions using remote workflows. Forget the makeshift setups or convoys of trucks. Now, one of Europe’s most advanced and fully equipped production centres is available for your next project anywhere.

The ATM SYSTEM Remote Production Hub is a brand-new, purposebuilt facility developed to meet the demands of today’s fast-paced media landscape. Equipped with the latest broadcast technology and designed to support complex, hybrid, and decentralised workflows, it empowers production teams to operate with maximum flexibility, whether on-site, remote, or distributed across multiple locations. Behind the technology stands a seasoned crew of engineers, operators, and producers with decades of hands-on experience in high-profile productions. This is not just a facility, it’s a production

powerhouse that blends innovation with reliability, setting a new standard for remote broadcasting in Europe. The hub is located in Warsaw, just 25 minutes from the airport.

A complete technical ecosystem

At the heart of the facility is a high-performance production ecosystem that brings together the best in professional technology and flexible workspaces. Clients can access:

• Modular workstations configured for roles including directing, editing, commentary, or remote replay

• EVS VIA servers for high-speed ingest, replay, and playout

• Sony and Grass Valley switchers for live vision mixing

• GV AMPP tools for scalable cloud-based workflow management

• Lawo, Riedel, and RTS systems for precision audio handling and real-time intercom communication

The facility features two full-scale Production Control Rooms (PCRs) that can handle up to 14 camera sources, with integrated real-time graphics, multiview monitoring, and latency-free remote camera operation. These PCRs are ideal for high-end sport, live entertainment, esports, or live studio content.

For leaner operations, the Remote Production Facility supports “one-man show” configurations—perfect for podcasts, webinars, or small-scale streaming. These stations allow a single operator to control video switching, audio mixing, graphics insertion, and live streaming

from a single interface. It’s a smart, compact solution that preserves broadcast quality without the traditional crew overhead.

Besides two full-scale PCRs, we have 22 smaller, highly flexible PCRs (modular workstations). They can be configured for:

• Remote Replay

• One-man Show

• Remote VAR

• Remote commentary

With significant resources—over 30 ingest channels on EVS servers, hundreds of terabytes of storage, multiple fibre connections to major exchange points, numerous on-premises COTS servers, and strong integration with AWS—we can run more than 15 events simultaneously, with full operational backup provided by our second site in Wroclaw.

A smarter way to produce, without owning the infrastructure ATM SYSTEM’s remote production model is designed around one key principle: you focus on content, we take care of infrastructure.

Instead of building your own systems or investing in expensive hardware that may sit unused between productions, you gain instant access to our top-tier equipment, IP-based workflows, and scalable resources which are constantly maintained and upgraded by broadcast professionals.

Whether you’re scaling up to cover a large event or running multiple productions in parallel, our Remote Production Hub gives you the capacity, bandwidth, and expertise you need without the long-term cost, risk, and complexity of ownership.

Technology that’s always tested and ready What sets ATM SYSTEM apart is its commitment to continuous real-

world validation. New technologies and configurations are seamlessly integrated into live productions as part of our ongoing development process, so when a client uses a solution, it’s not experimental. It’s already field-proven, optimised, production-ready and fully compatible with your vision.

Network infrastructure that delivers at scale

Central to the remote production model is a high-bandwidth, lowlatency network architecture, connected directly to global Internet exchange points. Dynamic IP routing and signal orchestration are managed via Nevion VideoIPath, ensuring intelligent bandwidth usage, flexible control, and full visibility of all connected endpoints.

Whether your commentators are in another city, your OB truck is at a stadium, or your distribution partner is on another continent, ATM SYSTEM RPH keeps everything in sync.

Trusted by broadcasters, loved by production teams

ATM SYSTEM RPH isn’t just a facility. It’s the cutting edge of remote production, backed by a trusted company with decades of broadcast expertise. Since 2003, ATM SYSTEM has earned its place as one of the most recognisable names in Central Europe’s production landscape.

With over 600 productions delivered annually, a team of more than 200 specialists, and a fleet of 11,000+ professional equipment units, the company doesn’t just support live content; it integrates with your team, offering not only infrastructure but also insight, support, and a collaborative spirit that elevates every production.

Why clients choose ATM SYSTEM

√ End-to-end capabilities: from venue setup to final distribution

√ Broadcast-complete infrastructure: OB vans, remote facilities, camera and replay systems, intercom systems, film cameras, lenses and stage light

√ Punctuality and reliability: a record of delivering on time and on budget

√ Scalability and customisation: tailor-made solutions for large-scale events or agile productions

√ Operational efficiency: reduce crew travel, shipping, and logistics costs while increasing productivity

Let’s build the future of broadcast together

Whether you're a national broadcaster seeking a competitive edge, an international sports federation scaling global feeds, or a digital media producer running a nimble operation, ATM SYSTEM is the partner that brings your vision to life.

With centralised remote production, you can do more with less, deploy your crew across multiple projects simultaneously, and deliver consistent quality across geographies, all while maintaining creative control and reducing costs.

Learn more at: www.atmsystem.pl

In the first of what will become an occasional column, Matthew Corrigan has some thoughts on the pace of change in the world of broadcast technology

Irecently found myself driving along the Welsh equivalent of the Autoroute du Soleil, the A55 North Wales Expressway, when an elderly pantechnicon-style truck emerged from a slip road and joined the stream of traffic heading east at the end of the holiday weekend. Hunched over a forward control cab, its plethora of vented side panels and full-length roof rails made it resemble something that had been conjured from the imagination of Gerry Anderson. All became clear as I moved across to pass the slow-moving behemoth and the legend adorning its bright, silvery paintwork came into view. Printed in a rather retro but instantly recognisable font were the words “BBC TV Colour”. I was sharing the road with a vintage outside broadcast truck.

The van was registered in the early 1970s and it was tempting to imagine that it had somehow torn itself a hole in the space-time continuum while filming Tom Baker on location for Doctor Who. The likely reality, altogether more prosaic, was that the beautifully restored vehicle had been attending a display at one of the numerous resort towns scattered along the Clwyd coast.

Allowing myself to daydream a while, I wondered what the original production crew would have made of its modern day equivalent, had they suddenly found themselves catapulted 50 years into the future. In May, I was privileged to see such a vehicle in operation myself, thanks to an invitation from NEP Europe (more of which elsewhere in this issue). The technology aboard was astounding, providing teams with capabilities on a level that would simply not have been possible just five short decades ago.

And that’s the thing about technology—it races. Right across the broadcast arena, advances take place at a pace that is scarcely believable. Most people are probably familiar with the well-worn adage about modern mobile phones being more powerful than the Apollo Guidance Computer used by NASA to put astronauts on the Moon, but even the most jaded of industry commentators can’t fail to have been impressed that they were used to film parts of the Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony for its official broadcast last summer.

Of course, it’s not just in broadcast that the

pace of development takes the breath away. Throughout history, in all manner of human endeavour, innovation evolves at breakneck speed.

In 1885, for example, Karl Benz produced what was probably the first proper car. Henry Ford refined the manufacturing process just after the turn of the twentieth century and we’ve never looked back. At about the same time old Henry was knocking out Model Ts in any colour you wanted so long as it was black, the Wright Brothers were hopping across the Kittyhawk sands and into the record books as the first to achieve heavier-than-air powered flight. Less than 50 years later, Chuck Yeager became the first human to break the sound barrier. Today, we think nothing of sipping our G&Ts at 500 miles an hour, six miles above the surface of the planet, in thin metal tubes with fires blazing away just inches from several tonnes of volatile aviation fuel.

For every rule, however, there must be an exception. It was as far back as the middle of the 15th century that a German named Johannes Gutenberg produced the first ever printing machine. William Caxton brought the technology to England soon after, becoming this country’s first ever retailer of printed books. And today, some 600 years later, as everyone who has ever found themselves driven to the very edge of sanity by their printer as it sits there, stubbornly refusing to comply, can exasperatedly testify, we still haven’t managed to make the blasted things work properly.

By Ophir Zardok, head of sports strategy and business development, LiveU

As audiences demand more personalised content, traditional broadcast production faces rising costs and logistical hurdles. Improving efficiency in workflows and logistics is key, while delivering more high-quality content in the most dynamic, engaging and efficient ways has increased the demand for cost-effective, flexible IPbased production models.

Storytellers need to reach more viewers across multiple platforms whilst tailoring content to meet the varying expectations of different demographics, all while reducing costs. While fighting for eyeballs of the older generations, broadcasters and streaming services also have to win over Gen Z, who are more likely to be watching their favourite athletes, brands and shows on TikTok or YouTube. This age group wants dynamic, short, sharp authentic content packaged in a way that relates to them.

For sports broadcasters, building a genuine narrative requires careful planning, especially in the unpredictable world of live broadcast where spontaneity is key. Content creators will increasingly

Ophir

Zardok

PICTURED LEFT : At the International Belgian Judo Open Competition LiveU was part of a PoC that utilised a state-ofthe-art 5G standalone network slice

value innovative technologies with the flexibility that enables them to meet millennials and Gen Z’s demand for daily fan engagement.

Sustainability is another broadcast production driver. Broadcasters are influenced by viewers’ expectations to reduce their carbon footprint. This is evident in production tenders which have seen the development of innovative remote production workflows successfully solidify their place over the last five years, with broadcasters now incorporating standards to ensure sustainable production. These standards encourage carbon-efficient practices, from minimising travel emissions to reducing equipment power consumption, making sustainability a central element of event broadcasting in future.

Cost-efficiency is also a major factor. Broadcasters and other content producers can save up to 70 per cent off their costs with a wireless remote production set-up, removing the need for costly SAT/OB trucks.

The growing use of IP technology for producing live content incorporates these factors and enables dynamic, robust and flexible workflows. LiveU’s EcoSystem provides the technology and tools to facilitate remote production workflows spanning the entire video production chain, from contribution, production to distribution. Built on an interoperable, adaptable platform it delivers business agility with a variety of on-prem and cloud-based solutions and allows broadcasters to seamlessly produce live events using efficient, simplified workflows whilst reducing costs and increasing production value. The LiveU EcoSystem is underpinned by LiveU Reliable Transport LRT ensuring rock-solid reliability and low latency over cellular and other IP networks.

As technology evolves at pace, alternative versions of IP-video bonded connectivity solutions are being

tested in real-world environments, including private 5G, network slicing and the use of LEO (Low Earth Orbit) satellites, such as Starlink.

Network slicing gives telcos the ability to create a dedicated bandwidth “slice”, guaranteeing a certain amount of up and downstream bandwidth for a given period of time—the length of a football match, for example. This provides huge potential when combined with IP-bonding, creating a powerful combination across contribution workflows that overcomes previous network congestion issues.

Private 5G is also set to play an important role moving forward, especially for sports events in remote areas or other temporary scenarios. For smaller events, even without network slicing, IP-bonding works brilliantly with 5G. Further benefits of utilising private cellular networks are that they provide an additional layer of service for customers including network segmentation, prioritisation and greater security, while delivering additional capacity for expanded remote production technologies and employee communications.

Last year, LiveU won a FIDAL Open Call to take part in the ‘Large Scale Field Trials Beyond 5G’ research project, part of the EU Horizon project, co-funded by the 6G Smart Networks and Services initiative. In June 2025, it successfully completed the project, conducting dozens of meaningful beyond 5G tests and trials together with its LU800 PRO multi-cam bonding and LU-Xtend connectivity solution for three main remote production use cases. This included: cloud remote production— leveraging slicing configurations to guarantee bandwidth and latency for cloud-based broadcast workflows; edgebased production—integrating mobile edge computing within an operator infrastructure (like a private cloud); and on-site remote production with cloud-based solutions—testing uplink/downlink slicing configurations for full production workflows.

These solutions will undoubtedly have major benefits for broadcasters who are looking to maximise the latest technology innovations in order to expand remote production workflows.

5G and cloud tech drive a fully remote production Advanced innovative solutions utilising 5G and remote production workflows are not so far in the future. In a recent collaboration, LiveU, Orange Belgium, Atmosfair,

The evolution of broadcasting illustrates a future where technology, audience engagement, and content diversity will continue to shape the world of live sports production

ID2Move and Dreamwall delivered a fully remote, cloud-based production of the International Belgian Judo Open competition. This marquee event on the European judo circuit attracts competitors from around the world. To overcome traditional broadcasting challenges such as extensive travel, high equipment costs, and logistical complexities, a new approach was essential to meet the growing expectations of modern sports audiences.

Leveraging 5G and a remote production workflow, the aim was to produce the most engaging, immersive live sports event with minimum costs and resources on-site. The production team had to ensure seamless connectivity and reliable, high-quality video feeds from remote locations while integrating dynamic visual elements. Ensuring a streamlined workflow, with sustainable practices, was also a key factor.

The event included a PoC that utilised a state-ofthe-art 5G standalone network slice, guaranteeing dedicated bandwidth for uninterrupted transmission. The production leveraged LiveU Studio’s latest story-centric capabilities, such as instant replay, as well as remote guests and commentaries. Real-time augmented reality graphics, provided by Dreamwall, were integrated via the cloud, enhancing the live broadcast with engaging visual elements.

The collaboration resulted in a live broadcast that captivated judo fans across Europe. Audiences experienced the event through immersive visuals and innovative storytelling, setting a new benchmark for live sports coverage.

Using IP-based technologies, cloud and remote production workflows are optimised, and new standards are being set for sustainability and flexibility in live sports coverage. New tech enables new possibilities for increased personalisation with content that speaks directly to the fans, such as commentary in their own language and player stats.

The evolution of broadcasting—from the Paris Summer Games in 2024 to the global football clubs tournament in the US and next year’s Winter Games— illustrates a future where technology, audience engagement, and content diversity will continue to shape the world of live sports production.

Leader Electronics of Europe’s Kevin Salvidge looks at how broadcasters can mitigate the growing threat of

here have been some notable live broadcast outages in the past few years—but much of the coverage of such incidents has tended to focus on cybersecurity and IT infrastructure failures. However, there is another growing risk factor that broadcasters need to start prioritising as part of their crisis planning: GPS jamming of satellite-related broadcast services.

It’s hardly unexpected to find that the potential for broadcasting to be deliberately disrupted has expanded as the world has become significantly more unstable. With geopolitical and military tensions as a backdrop to various technological developments, the notion that a bad ‘state actor’ or extremist group might seek to employ GPS jamming to disrupt broadcast production is one that can no longer be ignored.

The threat is generally regarded to be especially high in live and/or remote production scenarios, where GPS jamming can variously disrupt transmission site synchronisation, affect transport stream timing in SFNs (Single Frequency Networks), and impair remote production tools and satellite uplink coordination. Broadcast centres that utilise GPS for their internal synchronisation needs—as with the use of Precision Time Protocol (PTP) in SMPTE ST 2110 IP standards—can also suffer synchronisation problems or sudden time changes when the GPS signal is no longer being jammed.

It’s important to note that many broadcasters and service providers have already taken proactive steps on this issue, especially those operating in some of the world’s most turbulent areas. For instance, it’s reported that broadcasters working in parts of the Middle East and near the borders of Russia are now, as a matter of routine, deploying GPS jamming detection tools and identifying redundant time sources in case of disruption.

However, there are other scenarios that should give broadcasters cause for pause, such as planned and highly sensitive events like a Papal or US Presidential visit. In this case, to help protect the VIPs involved, GPS jamming would be utilised by the security services—albeit only when the individual(s) are in close proximity to the venue. But with the broadcast set-up for such events usually beginning at least several days in advance, there would be ample time to establish connections and achieve synchronisation with GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System). So as long as all SPGs (Sync Pulse Generators) have previously locked to GNSS, they will transition into ‘Stay-In-Sync’ or holdover mode once GNSS is lost. For single OB truck operations, internal timing remains stable so there is unlikely to be a problem there. But with multiple OB truck productions, it’s vital that each truck’s SPG is synchronised with the others.

This presents an unavoidable extra level of complexity that requires scrupulous planning to guarantee that timecode and genlock remain consistent across all units.

There are other steps that broadcasters can take to mitigate the threat of GPS jamming, and to help get the show back on the road as quickly as possible if they do suffer disruption. Principal among these is the acquisition of a sync pulse generator, such as Leader’s own LT4670 ‘True Hybrid’ IP and SDI SPG, with multiple constellation GNSS receivers that —in addition to the US-owned GPS—can use other satellite navigation systems including Galileo (EU), BeiDou (China), GLONASS (Russia) and QZSS (Japan).

Use of a multi-GNSS receiver brings welcome robustness into the setup; after all, jamming all GNSS simultaneously is far harder than jamming one of them. Additionally, SPGs like the LT4670 also use an internal OCXO (Oven Controlled Crystal Oscillator) that can frequency- and phase-lock to a GNSS. Consequently, if and when connection is lost, the LT4670 can continue to provide reference signals based upon the internal OCXO.

The name for this particular functionality is ‘Stay-in-Sync’ mode or PTP Clockclass 7. Another feature that can benefit broadcasters wishing to minimise their GPS jamming exposure is ‘Slow Sync’, which reduces the shock when synchronisation is re-established based on stay-in-sync. Thanks to its application to BB/TLS, SDI, digital audio and PTP references, ‘Slow-Sync’ supports the construction of a very reliable synchronisation system by gradually bringing the timing in-line when GNSS contact resumses.

For a variety of reasons, these are challenging times for broadcasters, and so it’s perfectly understandable if news of this further risk to operations does not receive the warmest of welcomes. However, it’s also an issue where the threat can be dramatically reduced if the correct steps are taken—ensuring that you have the best possible chance of keeping those all-important live and remote productions on the air.

“The threat is generally regarded to be especially high in live and/or remote production scenarios”

Frank Foti, executive chairman at Telos Alliance, tells Jenny Priestley about his work to revolutionise audio with an upmixing technology that transforms stereo into immersive 5.1 surround sound

While many broadcasters and streamers are moving towards higher resolutions in terms of what viewers see, sound is being left behind, with the majority of TV programming still delivered, and heard, in stereo.

But Frank Foti, executive chairman at Telos Alliance, is on a mission to change that. Foti is the driving force behind Déjà Vu, upmixing technology that can take a piece of audio to the next level, turning it from stereo into 5.1 surround sound.

The idea for Déjà Vu began in 2002, during the early

days of digital radio in the United States. Foti and his late partner, Steve Church, noticed that the transition to HD radio lacked the ‘wow factor’ that accompanied the advent of HD television. This prompted a question: Could they deliver discrete surround sound over the existing FM HD system?

Foti and Church discovered Fraunhofer’s MPEG surround technology, which enabled surround sound transmission, and created a way to do the same on FM in America.

However, at the time, there wasn’t much content available in surround sound. Foti realised that for broadcasters to fully embrace surround, all their

content would need to be upmixed. That set him on a journey to develop a method for creating a true 5.1 surround presentation from stereo audio, without relying on “tricked-up” effects. “There are other upmix items out there, and they sort of work, but they use electronic tricks like phasing and time delay and reverb and things of that nature to create the surround effect,” he says. “I wanted more than that.”

The core idea was to generate a true centre channel from stereo audio. “When we listen in stereo, what comes to our ears, and what we feel is in the centre, is known as phantom centre,” Foti explains. “There is no centre channel. Déjà Vu creates the actual centre channel based on the mix that’s there. There’s no steering, it’s based on the actual mix. So from that, I’m able to then derive the other channels.”

it sound as if everything was originally mic’d for surround. The same transformative effect applies to older stereo films, placing dialogue front and centre while immersing the viewer in ancillary effects.

Currently, Déjà Vu is available as a standalone application for Mac and Windows, and as a plugin in three different formats. It can also operate in the cloud, and an SDK is available for broadcasters or streaming services looking to incorporate the technology.

Having created what he believed to be a breakthrough, Foti sought feedback from various musical experts. He was able to showcase Déjà Vu to music producer Gary Katz (of Steely Dan fame), who immediately recognised its potential. “Next thing I know, we’re on a plane to London, and Gary booked an afternoon at Abbey Road,” Foti says. There, they met with Hugh Padgham and Giles Martin, who both gave the technology the thumbs up. “If people who have Grammys and hit records to their credit say you’ve got something, well, I think we’ve got something!”

While initially focused on music, Foti and the team at Telos Alliance began to explore Déjà Vu’s potential beyond the music industry. “None of us, including myself, had ever really ventured into playing around with movies or television,” he says. Over the last year, the technology has been tested on older stereo films and sports broadcasts.

At NAB Show in April, Foti demonstrated Déjà Vu with clips from Monday Night Football. “The announcers were in the centre, the team chatter was left front, right front, the crowd was all around you, which would be what you want to have happen,” he explains. This proved Déjà Vu could be a tool for broadcasters and streamers to deliver a true 5.1 surround presentation from a stereo mix, making

The future of immersive audio Foti sees Déjà Vu as an alternative to Dolby Atmos, but it can also be used to augment the technology. “With Atmos, to get the effect, you have to start with the multiple channels; it doesn’t create them. It’s basically a rendering system,” he explains. “Say you have some old film that’s only in stereo, Déjà Vu could render it into discrete 5.1 and then from that, use the multiple channels into the Atmos renderer, so you’re able to create an Atmos presentation.

“Also, we can take the 5.1 audio channels and route those to whatever surround encoder is going to be used in the television system. In many ways, it can serve multiple masters.”

The technology works with any encoder and doesn’t rely on data reduction to create its effects, operating in a “very linear fashion.” For the optimal experience, Foti says Déjà Vu is best enjoyed with speakers because of its multiple channels. However, it can work with headphones, and Foti has developed Déjà Phonic, a separate application that can render immersive audio for headphones, offering an even more threedimensional effect.

Looking ahead, Frank believes the future of sound in TV and film will be driven by consumer demand and the ability to leverage existing home audio setups.

“Something like Déjà Vu is perfect because you get a combination of wow factor and emotion,” he concludes. “You’re watching some wonderful scene in a movie, and the sound is just right, and it moves you to tears. At that moment, you’re not thinking, oh this is great because I heard something out of the left rear speaker. It comes about because of what you’re hearing. If we can serve that visually and audibly, we all win.”

Rami Moussawi, senior product manager at ST Engineering, offers an insight into how the DVB-NIP standard is bridging the gap between broadcast and IP content delivery

The transformative DVB-NIP standard is poised to have a dramatic impact on the satellite broadcasting industry. Allowing the integration of satellite delivery into the wider IP-based content delivery ecosystem, content can be distributed efficiently and at scale.

Pioneered by an active group of DVB members in 2021, and then commercially developed by a group including Eutelsat and

ST Engineering iDirect, it opens the door to truly converged media delivery. The standard was published in 2024 and enables the delivery of OTT content using broadcast technology, whether satellite or terrestrial. It allows for the seamless delivery of IPbased content to VSAT networks and low-cost set top boxes (STBs) with ultimate delivery to IP-based devices such as smart TVs, smartphones and other mobile devices.

DVB-NIP helps service providers overcome the problem of congested networks that reduce quality of experience in high usage environments. The standard addresses many of the challenges that service providers face in trying to deliver a consistent user experience to a broad audience, by offering a multicast solution that allows content at its highest quality to be delivered simultaneously to multiple endpoints without overloading the network. Further optimisation is gained by caching content at these endpoints. This essentially creates micro-CDNs or media hotspots much closer to the end users that can be refreshed with content during off-peak hours and further reduces the load on networks. This not only enhances the quality of the delivery but can also be used to enhance and complement other types of networks.

It also provides satellite reach to streaming video services by allowing IP-based video services to reach users, wherever they are, helping to close the digital divide.

Market adoption and business justification