Great Minds® is the creator of Eureka Math® , Wit & Wisdom® , Alexandria Plan™, and PhD Science®

Published by Great Minds PBC greatminds.org

© 2023 Great Minds PBC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying or information storage and retrieval systems—without written permission from the copyright holder. Where expressly indicated, teachers may copy pages solely for use by students in their classrooms. Printed in the USA A-Print

Module Summary 2

Essential Question 3

Suggested Student Understandings 3 Texts 3

Module Learning Goals 4 Module in Context ............................................................................................................................... ...................... 6 Standards ............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 6 Major Assessments 8 Module Map 10

Focusing Question: Lessons 1–7 How does society influence identity and experience?

Lesson 1 ............................................................................................................................... ...................................... 23

n TEXT: “Identity”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Figurative Language Lesson 2 35

n TEXTS: “The Middle Ages—The Medieval Years” • “Nobles” • “Knights” • “Clergy” • “Tradesmen” • “Peasants”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary

Lesson 3 49

n TEXT: Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Concise Writing

Lesson 4 61

n TEXT: Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Concise Writing

Lesson 5 71

n TEXT: Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Word Relationships

Lesson 6 81

n TEXT: Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary

Lesson 7 93

n TEXT: Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

What do The Canterbury Tales reveal about identity and storytelling?

Lesson 8 ............................................................................................................................... ..................................... 99

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Lesson 9 111

n TEXTS: The Canterbury Tales • Pilgrims Leaving Canterbury • Audio: Prologue to The Canterbury Tales • “Lamento di Tristano” Musical Recording (optional)

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Concise Writing

Lesson 10 125

n TEXTS: “Knights” • The Canterbury Tales, “The Knight’s Tale”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary: Lesson 11 139

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales, “The Miller’s Tale: A Barrel of Laughs”

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive Lesson 12 151

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales, “The Miller’s Tale: A Barrel of Laughs”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Figures of Speech: Lesson 13 163

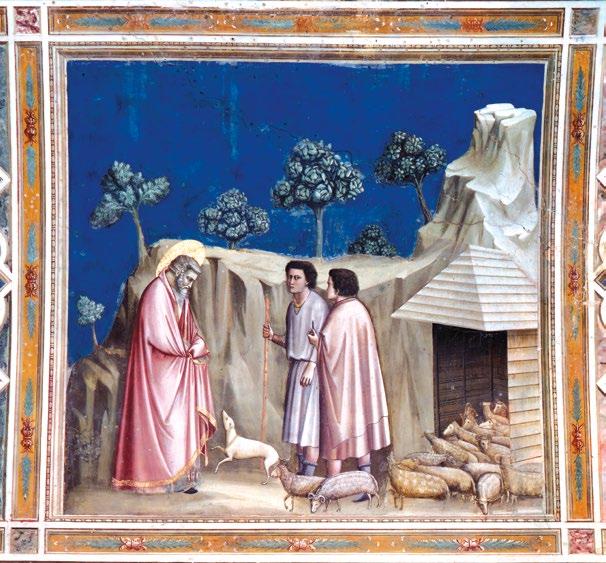

n TEXT: Joachim among the Shepherds

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary Lesson 14 175

n TEXTS: The Three Living and the Three Dead • The Canterbury Tales, “The Pardoner’s Tale: Death’s Murderers”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Figures of Speech

Lesson 15 187

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales, “The Pardoner’s Tale: Death’s Murderers”

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Concise Writing

Lesson 16 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 199

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale: What Women Most Desire”

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary

Lesson 17 211

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment

Lesson 18 221

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Simple and Compound Sentences

Lesson 19 233

n TEXT: The Canterbury Tales

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Complex and Compound-Complex Sentences

In The Midwife’s Apprentice, how does the protagonist’s identity change over time?

Lesson 20 ............................................................................................................................... ................................. 245

n TEXTS: “What Is a Midwife?” • The Midwife’s Apprentice • Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary

Lesson 21 257

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Figurative Language

Lesson 22 267

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Sentence Structures

Lesson 23 277

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Coordinate Adjectives

Lesson 24 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 289

n TEXTS: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary

Lesson 25 301

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 26 317

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Experiment with Coordinate Adjective Sentences

Lesson 27 325

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Content Vocabulary

Lesson 28 337

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Execute with Coordinate Adjectives

Lesson 29 ............................................................................................................................... .................................. 347

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Morphology

Lesson 30 359

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Sentence Structures

What elements make for an engaging historical narrative?

Lesson 31 ............................................................................................................................... ................................. 369

n TEXT: End-of-Module Task Models

¢ Vocabulary Deep Dive: Vocabulary Assessment

Lesson 32 377

n TEXT: The Midwife’s Apprentice

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Phrases and Clauses

Lesson 33 385

n TEXT: All Module Texts

Lesson 34 391

n TEXT: All Module Texts

¢ Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Excel with Language Skills

Lesson 35 401

n TEXT: All Module Texts

Appendix A: Text Complexity ............................................................................................................................. 407

Appendix B: Vocabulary 411

Appendix C: Answer Keys, Rubrics, and Sample Responses 419

Appendix D: Volume of Reading 431

Appendix E: Works Cited 433

What did she want? No one had ever asked her that and she took it most seriously. What do I, Alyce the inn girl, want?... She thought all that wet afternoon and finally, as she served Magister Reese his cold-beef-and-bread supper, she cleared her throat a time or two and answered: “I know what I want. A full belly, a contented heart, and a place in this world.”

—Karen Cushman, The Midwife’s ApprenticeFor an adolescent, perhaps no inquiry is more pressing than the question of the self. As we strive to figure out how we fit in and what our place might be, society’s impact is palpable, calling us to ask: How does society influence identity? Can a social hierarchy limit opportunity? To what extent are we free to shape the course of our lives?

Module 1 explores these questions of identity in society by taking students on a literary expedition across a famously inflexible social setting: Medieval Europe. Though it may seem distant, this medieval exploration illustrates the influence of societal forces on identity formation—an influence that remains undeniable in seventh graders’ modern setting.

Our students begin their literary journey with a stay in a lord’s castle, brought to life through Richard Platt’s historical fiction narrative, Castle Diary. Through the eyes of a curious young page, students observe the medieval social hierarchy’s power in action, meeting nobles, servants, knights, and poachers whose fates are tied to the rigid societal structure in which they live. Next, Chaucer whisks students away on a rollicking pilgrimage through his captivating classic anthology, The Canterbury Tales, retold by Geraldine McCaughrean. On the road to Canterbury, characters from disparate social classes swap stories and bond, revealing the power of narrative to transcend both social divisions and time. Karen Cushman’s novel, The Midwife’s Apprentice, then brings students to the foot of a dung heap, from which an orphaned girl emerges to make her way in the world. Her inspiring fight to carve a place for herself within medieval society illuminates the complexity and rewards of any quest to transform one’s life despite injustice, deepening students’ thinking about the relationship between society and the self.

For their End-of-Module (EOM) Task, students write their own narratives set in the Middle Ages. They apply historical fiction elements learned throughout their study—historical details supplied by Castle Diary, narrative techniques modeled by The Canterbury Tales, and writing experimentation supported by The Midwife’s Apprentice—to demonstrate how society can support and limit the development of identity.

The daily lives of medieval Europeans were shaped by a rigid social order, in which one’s birth determined much about one’s life. Daily opportunities are influenced by social class, but it is possible to challenge the social order and construct personal identity. Historical fiction explores how individuals may have experienced challenges created by society, offering a vivid sense of life in other times and places. Authors purposefully use narrative elements and techniques to create strong characters, striking settings, and compelling stories.

Prologue to The Canterbury Tales, various readers (http://witeng.link/0710)

“What Is a Midwife?,” Karen Carr (http://witeng.link/0741)

Selections from The Middle Ages Teacher’s Guide, Western Reserve Public Media (http://witeng.link/PBS_Middle-Ages-Teacher-Guide) p “Introduction to the Middle Ages Era” (9-10) p “Clergy” (43) p “Knights” (42) p “Nobles” (40-41) p “Peasants” (45-46) p “Tradesmen” (44)

“Lamento de Tristano,” Anonymous (http://witeng.link/0711)

Joachim among the Shepherds, Giotto di Bondone (http://witeng.link/0712)

Pilgrims Leaving Canterbury, From Lydgate’s Siege of Thebes (http://witeng.link/0709)

The Three Living and The Three Dead, Master of the Dresden Prayer Book (http://witeng.link/0716)

“Identity,” Julio Noboa Polanco (http://witeng.link/0740)

Identify factors that influence identity (what makes us who we are?).

Describe the varied groups that formed the medieval period’s social hierarchy, and explain how one’s social class influenced daily life.

Identify characteristics that make The Canterbury Tales an enduring classic.

Understand narrative elements and techniques, analyzing their function in works of fiction and exploring them in the students’ own narrative writing.

Determine a theme and analyze its development over the course of the text (RL.7.2).

Provide an objective summary of the text (RL.7.2).

Analyze how particular elements of a story interact, especially in regard to how the medieval setting shapes characters’ identities (RL.7.3).

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings (RL.7.4).

Write a medieval historical fiction narrative using effective technique, relevant descriptive details, and a well-structured event sequence with a conclusion (W.7.3, W.7.3.e).

Engage and orient the reader by establishing a medieval context and point of view and introducing a character from the Middle Ages (W.7.3.a).

Use narrative techniques, such as dialogue, pacing, and descriptive detail, and sensory language to develop experiences, events, and characters (W.7.3.b, W.7.3.d).

Notice mood and tone in speaking and listening.

In Socratic Seminars, collaborate by building on and responding to the thinking of others, and track goals toward progress in speaking and listening (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Purposefully use simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences to signal differing relationships among ideas and help pace writing (L.7.1.b).

Choose language carefully, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy, in order to express ideas precisely and concisely (L.7.3.a).

Use context and common, grade-appropriate Greek and Latin affixes and roots to help determine or clarify the meaning of target words and phrases (L.7.4). Interpret figures of speech such as similes, metaphors, imagery, personification, and allusion; and apply these elements in writing to create depth and interest (L.7.5.a).

Knowledge: In Grade 7, students investigate identity in society. Module 1 develops key foundational knowledge by immersing students in the Middle Ages—a period characterized by a rigid social order. Texts from and about the Middle Ages introduce students to the concepts of identity, social order, social class, and hierarchy. Then, The Midwife’s Apprentice prompts students to consider the tension between societal forces and individuals who challenge them. This exploration lays the groundwork for a year of exploring the relationship between identity and complex concepts such as race, crisis, and power.

Reading: Students build a foundation that will support their work throughout the year, developing habits of mind as readers and skills in annotating, identifying textual evidence, summarizing, and determining theme. Beginning most intensively with The Canterbury Tales, students learn to analyze narrative elements and techniques, inferring how the narrator’s point of view shapes the telling of the stories and how the medieval setting impacts character development. These reading skills form a basis for monitoring comprehension and analyzing complex texts.

Writing: This first module activates interest in writing with a focus on one of the most engaging writing forms: the narrative. Students write creatively, examining and experimenting with craft techniques, such as dialogue, pacing, sensory language, and description. Through their experimentation with narrative techniques, students not only prepare to effectively blend content and craft when they complete their historical fiction EOM Tasks for Module 1—they also develop skills they can use to enliven their informational and argument writing in upcoming modules.

Speaking and Listening: Students have ample opportunity to develop their speaking and listening skills in this module’s four Socratic Seminars. To begin, students learn how to set speaking and listening goals, and they track their progress throughout each Seminar. This understanding of discussion goal-setting will serve students as they work to improve their speaking and listening skills throughout the year.

Reading

RL.7.1 Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

RL.7.2 Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text.

RL.7.3 Analyze how particular elements of a story or drama interact (e.g., how setting shapes the characters or plot).

RL.7.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the impact of rhymes and other repetitions of sounds (e.g., alliteration) on a specific verse or stanza of a poem or section of a story or drama.

W.7.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, relevant descriptive details, and well-structured event sequences.

W.7.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

L.7.1.b Choose among simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences to signal differing relationships among ideas.

L.7.3.a Choose language that expresses ideas precisely and concisely, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy.

SL.7.1.b Follow rules for collegial discussions, track progress toward specific goals and deadlines, and define individual roles as needed.

RL.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

RI.7.10 By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6–8 text-complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

L.7.6 Acquire and use accurately grade-appropriate general academic and domain-specific words and phrases; gather vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

1. Write a diary entry from the poacher’s point of view. In it, the poacher should reflect on 1) his place in the social hierarchy and 2) how his society has shaped his identity.

2. List four narrative elements or techniques that exemplify what The Canterbury Tales can teach readers about storytelling. Provide textual evidence that illustrates how The Canterbury Tales models each element or technique.

3. Use descriptive details to slow the pacing and “explode” a moment in the life of Alyce, The Midwife’s Apprentice’s protagonist.

Demonstrate an understanding of how the medieval social hierarchy shapes identity. Use sensory language to convey experiences. Establish character and point of view.

Demonstrate an understanding of how narrative elements and techniques develop strong storytelling.

RL.7.3, W.7.3, W.7.4

RL.7.1

1. Read pages 63–68 of Castle Diary. Respond to multiplechoice questions to demonstrate comprehension, determine word meaning, and analyze Platt’s use of historical detail.

2. Read chapter 10 of The Midwife’s Apprentice. Respond to multiplechoice questions, and write a paragraph to demonstrate understanding of word meaning, characterization, and theme.

Establish a medieval setting. Use narrative techniques to capture action and convey experiences.

Write an engaging beginning and an ending that provides resolution.

W.7.3, W.7.4

Demonstrate understanding of how historical fiction writers use historical details.

RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RL.7.4, RL.7.9

Demonstrate an understanding of characters from the medieval historical fiction.

RL.7.1, RL.7.2, RL.7.4

1. Explain how the medieval social order influences identity, experience, and opportunity.

Demonstrate an understanding of how the medieval social hierarchy influenced identity.

Pose opinions about identity in the medieval social order.

Respond to others’ perspectives about identity in the Middle Ages.

RL.7.3, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

2. Explain what The Canterbury Tales’ varied stories of medieval characters and society teach modern readers about strong storytelling and vivid characterization.

3. Analyze which big ideas are most important to chapter 7 of The Midwife’s Apprentice: sin, justice, good and evil, judgment, and punishment.

4. Explain how medieval society supports and limits Alyce’s identity in The Midwife’s Apprentice

Demonstrate understanding of how writers use storytelling elements and techniques to engage an audience.

Offer relevant critical comments about narrative elements and techniques.

Respond to others’ perspective about narrative elements and techniques.

Demonstrate understanding of themes relevant to medieval customs and beliefs.

Offer opinions about themes relevant to medieval customs and beliefs.

Respond to others’ perspectives about themes.

Demonstrate understanding of how medieval society can support and limit a character’s identity.

Offer opinions about identity development in medieval society.

Respond to others’ perspective about identity development in medieval society.

RL.7.3, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

RL.7.2, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

RL.7.3, SL.7.1, SL.7.6

Write an Exploded Moment narrative that demonstrates how medieval society supports or limits the protagonist’s identity.

Demonstrate how medieval society supports or limits your protagonist’s identity.

Use dialogue, descriptive details, and sensory language to develop your setting, events, and characters.

W.7.3, W.7.4

Demonstrate understanding of academic, text-critical, and domainspecific words, phrases, and/or word parts.

Use details that clearly set your story in the Middle Ages. Use a variety of sentence structures effectively.

Write a beginning that establishes character, point of view, and setting.

Write an ending that provides resolution.

Organize your plot sequence clearly so your reader can follow what is happening.

Write consisely, using precise language.

Use at least three words from your Vocabulary Journal.

Acquire and use grade-appropriate academic terms. Acquire and use domain-specific or text-critical words essential for communication about the module’s topic.

L.7.6

* While not considered Major Assessments in Wit & Wisdom, Vocabulary Assessments are listed here for your convenience. Please find details on Checks for Understanding (CFUs) within each lesson.

Focusing Question 1: How does society influence identity and experience?

1 “Identity” Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about “Identity”?

Experiment

How does figurative language work?

Build knowledge about the concept of identity.

Experiment with figurative language (L.7.5).

Interpret similes, metaphors, and imagery in context, and apply them to a poem (L.7.5.a).

2 “Clergy”

“Knights”

“The Middle Ages—The Medieval Years”

“Nobles”

“Peasants”

“Tradesmen”

3 Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess, pages 7–29

Know

How do these texts build my knowledge of the medieval social order structure?

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about Tobias Burgess?

Experiment

How does figurative language work?

Summarize the structure of medieval society’s hierarchy (RI.7.2).

Use a Frayer Model to analyze new academic vocabulary and clarify its meaning using Greek affixes (L.7.4, L.7.4.b).

Formulate questions and initial impressions of Tobias’s identity based on Castle Diary’s first entries (RL.7.1).

Use figurative language to express personal identity in a poem (L.7.5).

Recognize and explain the difference between precise, concise prose and wordy writing (L.7.3.a).

4 Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess, pages 30–42

Organize

What is happening in Castle Diary?

Experiment

How does figurative language work? Examine

Why are speaking goals important?

Summarize understanding of Castle Diary’s plot, setting, and characters (RL.7.2).

Use figurative language to express key aspects of Tobias’s life and identity (L.7.5).

Identify wordiness and apply strategies to communicate ideas concisely and precisely (L.7.3.a).

5 NR Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess, pages 42–68

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of historical details reveal in Castle Diary?

Experiment

How do speaking goals work?

Analyze details about daily life in the middle ages (RL.7.9).

Experiment with speaking goals (SL.7.1).

Distinguish among the connotations of target vocabulary synonyms and rank them to better understand the words and their context (L.7.5.b, L.7.5.c).

6 Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess, pages 69–90

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of point of view reveal in Castle Diary?

Examine

Why is sensory language important? Experiment

How does sensory language work?

Analyze the poacher’s perspective to determine the medieval social hierarchy’s influence on daily life (RL.7.6).

Build skills in establishing character and point of view in writing (W.7.3).

Clarify the meaning of new content vocabulary using context clues, Greek or Latin affixes and roots, and lexical resources (L.7.4).

Focusing Question 1: How does society influence identity and experience?CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS

7 SS FQT

Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess Know

How does Castle Diary build my knowledge of identity, experience, and opportunity in the Middle Ages?

Engage in a collaborative conversation, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, using formal English, and tracking progress toward goals (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Express understanding of how Castle Diary’s medieval setting shapes characters’ identities (RL.7.3).

Create diary entry using first person point of view and sensory language to express insight into medieval identity (W.7.3).

CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS

8 The Canterbury Tales, Prologue Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about The Canterbury Tales?

Formulate observations and questions about the prologue to The Canterbury Tales (RL.7.1).

Verify the predicted meaning of target words based on the suffix –age, class discussion, and lexical resources (L.7.4.b, L.7.4.d).

9 The Canterbury Tales, Prologue

The Canterbury Tales, audiobook

Pilgrims Leaving Canterbury “Lamento di Tristano”

Organize

What is happening in The Canterbury Tales?

10 The Canterbury Tales, “The Knight’s Tale”

“Knights,” Western Reserve Public Media

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of characterization reveal in “The Knight’s Tale”?

Examine

What are the elements of fluency? Execute

How can I use the elements of an effective summary to write my own?

Analyze how the author’s use of descriptive details supports characterization (RL.7.1, RL.7.3).

Summarize the setting, plot, conflict, and characters of The Canterbury Tales (RL.7.2).

Identify and eliminate redundancy in writing (L.7.3.a).

Summarize the sequence of events in “The Knight’s Tale” (RL.7.2).

Analyze how the “The Knight’s Tale” reflects his character (RL.7.3).

Define chivalrous using context clues and the Latin affix –ous, and apply it appropriately in a sentence (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

11 The Canterbury Tales, “The Miller’s Tale” Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of characterization reveal in “The Miller’s Tale”?

Examine

How do details help narratives come to life for readers? Experiment

How can I incorporate the elements of fluency into my own fluent reading?

Identify specific textual details that help the narrative come to life for the reader (RL.7.1).

Analyze how the author’s choices about plot, description, and narrative structure develop the character of the Miller (RL.7.3, W.7.2).

Identify phrases and clauses and explain their function in specific sentences (L.7.1.a).

Focusing Question 2: What do The Canterbury Tales reveal about identity and storytelling? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS12 The Canterbury Tales, “The Miller’s Tale” Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of language and tone reveal in “The Miller’s Tale”?

What are figures of speech, and how do they work to show character and convey tone?

Execute

How can I demonstrate fluency?

Practice writing figures of speech (similes and metaphors) to describe characters and convey tone (W.7.3.b).

Analyze how the author’s choices about language and tone reveal the character of the Miller (RL.7.3).

Identify and interpret figures of speech and sensory language in the context of “The Miller’s Tale” (L.7.5).

13 Joachim among the Shepherds Organize

How does Giotto use composition and space to tell a story?

14

The Canterbury Tales, “The Pardoner’s Tale”

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about “The Pardoner’s Tale?”

Closely observe and analyze a work by Giotto and cite specific visual evidence to support analyses (RL.7.1, SL.7.2).

Clarify the meaning of target vocabulary using context clues, Greek or Latin affixes and roots, and lexical resources, and apply the target word appropriately (L.7.4).

Formulate observations and questions about “The Pardoner’s Tale” (RL.7.1).

Identify and interpret instances of personification and allusion in the context of “The Pardoner’s Tale” (L.7.5.a).

Focusing Question 2: What do The Canterbury Tales reveal about identity and storytelling? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS15 The Canterbury Tales, “The Pardoner’s Tale” Distill

What is the central idea of “The Pardoner’s Tale,” and how is this idea developed over the course of the story?

Examine

How and why do storytellers pace their stories?

Analyze how the author develops and reveals a central idea in “The Pardoner’s Tale” (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Apply various strategies to communicate ideas concisely and precisely in writing (L.7.3.a).

16 The Canterbury Tales, “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” Organize

What is happening in “The Wife of Bath’s Tale?”

Examine

How do storytellers engage and orient their readers?

Analyze the interaction between character and plot in “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” (RL.7.3).

Clarify the meaning of new content vocabulary using context clues, Greek or Latin affixes and roots, and lexical resources (L.7.4).

17 VOC

The Canterbury Tales Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of narrative techniques reveal about effective storytelling?

Examine

How and why do storytellers explode specific moments in their stories? Experiment

How can adding description help me show an important moment in a story?

Explore how word choices, details, and other narrative techniques “explode” a moment of a narrative (RL.7.3).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-level vocabulary (L.7.6).

Focusing Question 2: What do The Canterbury Tales reveal about identity and storytelling? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS18 SS The Canterbury Tales Know

How does The Canterbury Tales build my knowledge of strong storytelling?

Examine

Why is noticing another speaker’s mood, tone, or intent important in collaborative discussions?

Experiment

How does noticing mood, tone, and intent work?

Engage in a collaborative conversation, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, acknowledging new information, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Track progress toward specific goals for participating more effectively in group discussion (SL.7.1.b).

Identify and explore how simple and compound sentences signal differing relationships among ideas (L.7.1.b).

19 FQT The Canterbury Tales, Epilogue Know

How does The Canterbury Tales build my knowledge of strong storytelling?

Demonstrate knowledge of what The Canterbury Tales exemplifies about strong storytelling (RL.7.1).

Identify and explore how complex and compound-complex sentences signal differing relationships among ideas (L.7.1.b).

Focusing Question 2: What do The Canterbury Tales reveal about identity and storytelling? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS20 The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapter 1

Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess

“What Is a Midwife?”

Wonder

What do I notice and wonder about The Midwife’s Apprentice?

21 The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 2–3 Organize

What is happening in The Midwife’s Apprentice?

Examine

What narrative techniques do writers use to create an Exploded Moment?

Build content knowledge about the role of midwives in medieval society.

Formulate observations and questions about The Midwife’s Apprentice (RL.7.1).

Use a Frayer Model to study the word relationship between and clarify the meanings of protagonist and antagonist (L.7.4, L.7.5.b).

Identify narrative elements in chapters 1, 2, and 3 of The Midwife’s Apprentice (RL.7.3).

Describe the narrative techniques authors use to develop vivid writing (W.7.3).

22

The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 4–5 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of characterization reveal in chapters 4 and 5 of The Midwife’s Apprentice?

Identify and interpret idioms in context (L.7.5.a).

Describe Alyce’s development between chapters 4 and 5 of The Midwife’s Apprentice (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Experiment with different sentence structures to better understand how to signal differing relationships among ideas (L.7.1.b).

Focusing Question 3: In The Midwife’s Apprentice, how does the protagonist’s identity change over time? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS23 The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapter 6 Distill

What is a theme of The Midwife’s Apprentice?

24 SS The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapter 7 Distill

What is a theme of The Midwife’s Apprentice?

Execute

How can I incorporate the elements of fluency into my reading of The Midwife’s Apprentice?

Analyze how the events in chapter 6 support the book’s theme of identity development (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Identify and correctly punctuate coordinate adjectives (L.7.2.a).

How can I track my progress toward speaking goals?

Analyze how Alyce’s conflict with the villagers develops themes in chapter 7 (RL.7.2, RL.7.3).

Engage in a collaborative conversation, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, acknowledging new information, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Study the word relationship between target content words to help clarify their meaning (L.7.4.d, L.7.5.b).

25 The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 8–9 Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of descriptive details reveal in chapters 8 and 9?

How do snapshots and thoughtshots work?

Analyze how Cushman uses descriptive details to develop Alyce’s story (RL.7.3).

Experiment with descriptive details (W.7.3.d).

Explain how phrases and clauses affect writing (L.7.1.a).

Focusing Question 3: In The Midwife’s Apprentice, how does the protagonist’s identity change over time? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS26 NR The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 10–11

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of conflict reveal in chapters 10 and 11?

27 The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 12–13

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of point of view reveal in chapters 12 and 13?

Experiment

How can snapshots and thoughtshots convey character information?

Independently determine word meaning, theme, and characterization in chapter 10 (RL.7.2, RL.7.4).

Identify and describe Alyce’s conflicts in chapter 11.

Complete sentence frames using sets of appropriately punctuated modifiers (L.7.2.a).

Analyze how Cushman develops the contrast between how Alyce views herself and how others view her (RL.7.6).

Use descriptive details to convey information about characters (W.7.3.d).

Distinguish among the connotations of synonyms of the target vocabulary and rank them to better understand the word and its context (L.7.5.b, L.7.5.c).

28

The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 14–15

Reveal

What does a deeper exploration of character development reveal in chapters 14 and 15?

Experiment

How do baby steps work?

Analyze how Alyce’s interactions with other characters reveal her growth.

Use descriptive details to adjust narrative pacing (W.7.3.d).

Appropriately use coordinate adjectives to add description in writing (L.7.2.a).

Focusing Question 3: In The Midwife’s Apprentice, how does the protagonist’s identity change over time? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS29 The Midwife’s Apprentice, Chapters 16–17 Distill

What is the essential meaning of The Midwife’s Apprentice?

How do narrative beginnings and endings work?

Analyze how Cushman uses descriptive details, historical details, and theme in the resolution (W.7.3.a, W.7.3.e).

Experiment with effective introductions and conclusions in narrative writing (W.7.3.a, W.7.3.e).

Use context and apply common, gradeappropriate Greek or Latin affixes and roots as clues to determine the meaning of a word (L.7.4.a, L.7.4.b).

30 FQT SS

The Midwife’s Apprentice Know

How does The Midwife’s Apprentice build my understanding of the connection between individual identity and society?

Excel

How can I improve my speaking and listening skills?

Execute

How can I use narrative techniques in Focusing Question Task 3?

Engage in a collaborative conversation, drawing on evidence, posing questions, responding to others, acknowledging new information, and using formal English as appropriate (SL.7.1, SL.7.6).

Explain how Alyce’s identity is supported and limited by her society (RL.7.3).

Create a scene that uses narrative techniques to express understanding of Alyce’s identity (W.7.3).

Apply different sentence structures to signal differing relationships in writing (L.7.1.b).

Focusing Question 3: In The Midwife’s Apprentice, how does the protagonist’s identity change over time? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS31 VOC EOM

All Module Texts Know

How do End-of-Module Task models build my knowledge of historical fiction elements?

Examine

What are the elements of a successful historical fiction narrative?

Identify building blocks of effective narratives (W.7.3).

Analyze sample EOM task narratives (W.7.3).

Demonstrate understanding of grade-level vocabulary (L.7.6).

32 The Midwife’s Apprentice, pages 30–32 Know

EOM

How does Cushman’s writing build my knowledge of what an effective historical fiction narrative is?

Execute

How can I use elements of historical fiction to create my own historical fiction narrative?

Analyze narrative elements and techniques in an excerpt from The Midwife’s Apprentice (W.7.3).

Formulate ideas for a short narrative featuring a character from the Middle Ages (W.7.3).

Employ phrases and clauses appropriately to enhance writing (L.7.1.a).

33 EOM All Module Texts Know

How has the study of medieval stories in this module built my knowledge of stories, identity, and the Middle Ages?

Execute

How can I use elements of historical fiction to create my own historical fiction narrative?

Write a short narrative, set in the Middle Ages and featuring a clearly described character, conflict, and resolution (W.7.3).

Provide thoughtful and informed peer review (W.7.5).

Focusing Question 4: What elements make for an engaging historical narrative? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALS34 All Module Texts Know

How do effective peer feedback and selfreflection build my knowledge of how to tell a story?

Excel

How do I improve my historical fiction narrative?

Experiment

How can I read my narrative fluently?

Review and revise draft of narrative assignment (W.7.3, W.7.5).

Edit and revise writing to demonstrate command of English conventions and understanding of grade-appropriate words and phrases (L.7.1, L.7.5, L.7.6).

35

How do our historical fiction narratives offer insights into identity and medieval life?

Excel

How do I use my best fluency skills to present my story?

Present writing clearly, fluently, and with expression to engage and entertain listeners (SL.7.6).

Focusing Question 4: What elements make for an engaging historical narrative? CENTRAL TEXT(S) CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION CRAFT QUESTION(S) LEARNING GOALSAGENDA

Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (5 min.)

Learn (55 min.)

Notice and Wonder (20 min.)

Explore Personal Identity (15 min.)

Examine Figurative Language (10 min.)

Experiment with Figurative Language (10 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Share Writing

Wrap (5 min.)

Assign Homework

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Figurative Language: Imagery (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.7.1

Speaking and Listening

SL.7.1, SL.7.2, SL.7.6

Language

L.7.5, L.7.5.a

MATERIALS

None

Build knowledge about the concept of identity.

Create identity webs listing components of identity.

Experiment with figurative language (L.7.5).

Write phrases that use figurative language to convey personal identity.

Interpret similes, metaphors, and imagery in context and apply them to a poem (L.7.5.a).

Incorporate additional imagery into identity webs.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–7

How does society influence identity and experience?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 1

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about “Identity”?

CRAFT QUESTION: Lesson 1

Experiment: How does figurative language work?

Students begin their study with an introduction to the concept of identity. Throughout the module, they will develop their understanding of this concept in relation to the specific context of the Middle Ages, exploring questions such as: What shapes the identities of characters from this time period? How do authors create these characters’ identities? How do stories tell us who a person is, why they are that way, and what makes them unique?

Welcome5 MIN.

Display the following quotations:

“Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.”

—Oscar Wilde

“It takes courage to grow up and become who you really are.”

—E. E. Cummings

“To be nobody but yourself in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight; and never stop fighting.”

—E. E. Cummings

Ask students to respond to the following in their Response Journal: “Choose one quotation, think about what it means, decide whether you agree with it, and explain why or why not.”

Have pairs share their Welcome responses, and then briefly discuss each quotation as a class.

5 MIN.

Post the Content Framing Question, the Focusing Question, and the Essential Question. Explain that because the concept of identity is so important to these questions, this lesson will focus on that word and what it means.

55 MIN.

NOTICE AND WONDER 20 MIN.

Tell students that you will read a poem called “Identity.” Explain that whenever they read a new text, it is helpful to think about what they notice about it and what questions they have so they can begin to understand it.

Display a T-chart with one column labeled Notice and the other labeled Wonder, and have students create the same chart in their Response Journal. Explain that as you read the poem, students should record what they notice and wonder on the Notice and Wonder T-Chart.

Display the poem, and read the first two stanzas aloud. Model the task by thinking aloud about what you noticed and wondered as you read, adding your ideas to the Notice and Wonder T-Chart. Then ask students to add their ideas.

The poem is written in stanzas.

The speaker wants to be a weed.

n It doesn’t rhyme.

n The speaker says he wants to be a tall, ugly weed.

n He wants to be free, not tied down to a pot of dirt.

n He thinks he is different from others.

I wonder who “them” is in the first line.

What does she mean she wants to be a weed?

n What does “harnessed” to a pot of dirt mean?

n Why is this poem called “Identity”?

Read the rest of the poem aloud, as students add to their Notice and Wonder T-Charts.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What did you notice?”

Then, ask what students wondered about, and address some of their questions. For example, you might define words or invite the group to discuss ideas about who the poet is referring to as “them” in the first stanza.

Provide the following definition for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

identity (n.) The qualities and traits that make one person or group different from any other and recognized as such. individuality, personhood

Tell students that you will read the poem again and that this time they should record what they notice and wonder about the speaker’s identity.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What did you notice about what the speaker has to say about his identity?”

n The speaker is proud of who he is. He’s not admired like a flower. However, he’d rather be like a weed even if weeds are considered unattractive.

n He thinks being free and unique is more important than being accepted.

n He conveys another aspect of identity: his personality. He may not be pleasant like a flower, but he is determined, adventurous, and strong.

“What do you wonder about the speaker’s identity?”

n I wonder what has happened in his life that he is so worried about being free and doesn’t mind being ugly or not being seen by people.

n I still wonder who these other people are that he is talking about and why he thinks the way they are is so bad.

n I think he doesn’t like popular people, and I wonder why.

As students answer, prompt them to refer to the text by asking questions such as “What line are you basing that idea on?” “What part of the text makes you ask that question?”

Explain that you now want students to think about their own identities.

Have students create identity webs in which they write their name in the center of their sheet of paper. Explain that students should list words and phrases, extending outward from the center, that describe aspects of their identity.

To clarify expectations and build rapport, display your identity web before students begin. For example, your web might feature words such as “book lover,” “compassionate,” “Greek American,” “shy,” “mother,” etc.

Have students share their completed webs, first in small groups and then with the whole group.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What influenced or led to the words you listed?”

Use your own web to model. For example, you might say that you became a book lover because you had family and teachers that shared their own love of books with you, or you might say that you are Greek American because your ancestors were born in Greece but at some point moved to America.

n I am a big sister because my parents decided to have my brother. I didn’t have much choice about that.

n I play soccer because my parents had me start when I was little, but now I love it and I play because of me.

n I put “brave” on my web. I think I am brave because I’ve had to change schools a lot, and to make it at each school, I had to learn to be tough and brave.

Ask students to categorize some of the reasons they discussed. For example, you might say that you heard many students discuss their families as having influence, so that could be one category. Chart responses.

n Family.

n Personality traits you were born with.

n Beliefs and values you got from your family.

n Your race.

n Your goals and interests.

n Your gender.

Individuals

Display the Craft Question: How does figurative language work?

Tell students that you are going to read “Identity” again and that this time you want them to notice and wonder about the kind of language the author uses.

Read the rest of the poem aloud, as students add to their T-charts.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: “What did you notice?”

Then ask: “What did you wonder about?”

Incorporating what students noticed, explain that the technical term for much of the language the poet used is figurative language.

TEACHER NOTE

This lesson’s Deep Dive explores figurative language. You may wish to complete it at this time.

Individuals

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask: 1) If you were like a nonhuman thing such as an object, plant, or animal, what would you be? Why? 2) What nonhuman things are you most unlike? Why?

Choose one of your ideas or use a student’s idea, and explain why it is figurative language.

If I say, “I am like an arctic fox,” I am using figurative language to express my identity. It’s figurative language because I’m not literally like a fox. I don’t eat rabbits or have a bushy tail. However, I love the idea of running wild in the snow. I am quiet and tough and clever. This is who I am. I wouldn’t be a tame golden retriever. I’m too independent.

TEACHER NOTE Rather than using the example above, consider sharing insight into your identity with a personal response.

Have students add their figurative language examples to their webs.

Land5 MIN.

Remind students that they began the lesson by noticing and wondering about the new text, “Identity.”

Whip Around: One by one, each student shares one of the figurative language phrases they added to their web and why.

Explain that in the next lesson, students will begin studying identity within the context of the Middle Ages.

By creating identity webs, students develop a solid understanding of identity before exploring the concept within a medieval context. The other Checks for Understanding (CFU) assesses students understanding of how to use figurative language to express abstract concepts (L.7.5). Check for the following success criteria:

Identifies and justifies one nonhuman thing that represents the student’s identity.

Identifies and justifies one nonhuman thing that does not represent the student’s identity.

These figurative language examples represent the first writing technique among many that students execute throughout the module. Students will build on their figurative language examples to create identity poems in Lesson 3. Provide criteria for measuring CFUs, a brief analysis of the lesson’s learning, common student misunderstandings, and/or a brief summary of the next lesson. These poems should be two or three sentences long.

Time: 15 min.

Text: “Identity,” Julio Noboa Polanco (http://witeng.link/0740)

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Interpret similes, metaphors, and imagery in context and apply them to a poem (L.7.5.a).

TEACHER NOTE

In Vocabulary, the Module 1 Student Edition and Deep Dives 17 and 31, you will find a direct vocabulary assessment tool and corresponding directions. To best meet students’ language needs, consider using this tool to preassess students at the start of this module. Do not share results with students, but use the data to inform and differentiate your vocabulary instruction. At the close of the module, reassess students using the same tool to determine their growth against the baseline data.

You may also consider distributing the list of words to be directly assessed so students will know what words they will be held accountable for and can begin studying. Directly assessed words are noted in Appendix B.

Display the question: “Which words in Polanco’s poem paint a picture in the reader’s mind?”

Scaffold:

Ask students to recall their past studies on sensory details and how a writer can reference the senses in order to create an image in the reader’s mind. If they have difficulty remembering, conduct a Think Aloud wherein you read a detailed description and explain the picture that you “see” as you read the words.

Also consider explaining concepts such as line and stanza so students have a vocabulary with which to communicate their thoughts.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share about the imagery in Polanco’s poem. Ask students to annotate the poem as they look for language that paints a picture. Answers will vary.

n The author uses the simile “Let them be as flowers” in the first stanza so we can understand how he feels about people who want to be attractive and safe.

n The author uses the simile “like an eagle” in the second stanza to describe what it might be like to be a weed growing wild and free on a cliff.

n He uses a lot of details throughout the poem like “watered,” “fed,” “ugly,” “wind-wavering,” “pleasant-smelling,” and “musty, green stench” that appeal to our senses.

n He is using a flower as a metaphor—comparing it with people to help us understand how he feels about two different kinds of lifestyles or ways of being.

Explain that similes, metaphors, and sensory language are just a few tools writers use to construct a good poem.

Display a large poster titled Figurative Language that includes the following information on a 3x5 sticky note:

imagery—(n.) visually descriptive language, especially in a literary work

Briefly explain imagery:

Imagery is another tool that writers use to help the reader understand concepts they are trying to express. Imagery is like a complex metaphor and is not literal. It’s the use of words in a way that only makes sense in context.

To review an example of imagery, ask students to read the first sentence of Polanco’s poem with you. Explain that, although Polanco is using a metaphor and comparing people to flowers, there is a word in that line we don’t normally associate with flowers. The phrase “harnessed to a pot” stands out because we normally use the word “harness” when discussing horses or livestock. The use of an unusual word or phrase as description that helps paint a picture in the reader’s mind is imagery.

Ask: “Why do you think Polanco chose to use the word harness when referencing a flower in a pot?”

n We put harnesses on horses or things that we don’t want to escape, so he’s describing a flower—or person—that is confined.

n He might want to give the image of the flower being tied down and not free to grow where it wants.

n He is trying to describe how he feels about certain people who live a certain way; he is saying “let them live that way,” like a horse that’s controlled and not free to roam.

Continue the discussion using the following three examples of imagery from Polanco’s poem. For each example, ask students to explain why they think Polanco chose those particular words and what image they bring to mind. Guide student responses, and redirect inaccurate thinking when necessary.

Stanza 3: “exposed to the madness”

n He wants the reader to imagine how “crazy” big the sky is; and he wants to feel free like the weeds growing under it.

n He is trying to remind the reader how small we are compared to the “vast” universe and how crazy but also comforting that idea is.

Stanza 3: “beyond the mountains of time or into the abyss of the bizarre”

n Mountains are supposed to be forever; they are always there and immovable. He is trying to say that time is also forever. So, he wants his spirit to live beyond that.

n Polanco is presenting choices; he will either live somehow beyond time or go into some other existence.

n “The abyss of the bizarre” would mean something different for every reader because we can only imagine what that would look like. And people’s imaginations can think up very different things.

n “The abyss of the bizarre” could mean he could go on to another place beyond anything we know, like falling through a deep dark hole where weird creatures and landscapes occasionally float by.

Stanza 5: “smell of musty, green stench”

n He uses the word “green” to describe a smell because he wants the reader to imagine the smell of nature or plants growing; it’s like saying something smells purple—like grape.

n The word “musty” goes with “green stench” well when describing a weed; weeds don’t smell nice the way roses do, but they don’t have to be “harnessed” to a pot.

Students work in pairs.

After completing their identity webs, students focus on the imagery they have already written, and then on opportunities to incorporate additional imagery.

If students have difficulty finding imagery or images that make sense, have them discuss with a partner how they could use effective imagery to describe themselves.

These readings (in PDF) are currently available in the PBS Western Reserve The Middle Ages Teacher Guide (http://witeng.link/PBS_Middle-Ages-Teacher-Guide)

“The Middle Ages—The Medieval Years” pages 9–10

“Nobles” pages 40-41

“Knights” page 42

“Clergy” page 43

“Tradesmen” page 44

pages 45-46

Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (5 min.)

Learn (55 min.)

Summarize Text (25 min.)

Independently Summarize Text (30 min.)

Land (5 min.)

Answer the Content Framing Question

Wrap (5 min.)

Assign Homework

Vocabulary Deep Dive: Academic Vocabulary: Hierarchy (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RI.7.1, RI.7.2

Speaking and Listening

SL.7.1, SL.7.2, SL.7.6

Language

L.7.4, L.7.4.b

Entrance Task Visual (for display)

Handout 2A: Frayer Model Hierarchy

Handout 2B: Boxes and Bullets: “The Middle Ages—The Medieval Years”

Handout 2C: Boxes and Bullets: Medieval Groups

Volume of Reading Reflection Questions

Summarize the structure of medieval society’s hierarchy (RI.7.2).

Create summary of central and supporting ideas about medieval social order.

Use a Frayer Model to analyze new academic vocabulary and clarify its meaning using Greek affixes (L.7.4, L.7.4.b).

Share and analyze nonexamples, definitions, and roots/prefixes.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–7

How does society influence identity and experience?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 2

Know: How do these texts build my knowledge of the medieval social order structure?

This lesson marks students’ entry into the historical period of the Middle Ages. In it, students begin building an essential understanding that will be developed throughout the module: the concept of social hierarchy. Students summarize knowledge-building passages using a graphic organizer, Boxes and Bullets, to record the central and supporting ideas in informational texts.

5 MIN.

Display the following before students enter the classroom:

Those who fight

Those who pray

Those who work

Meant to pique students’ curiosity, the statements will be discussed later in the lesson and throughout the module, but students should not have their attention directed to them yet.

Provide the following definition for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

Word Meaning hierarchy (n.) A system for organizing groups, such as people, ideas, or objects, based on levels of their importance, power, or social standing.

Display this visual:

(Source: Microsoft Word, Smart Art, Hierarchy)

In their Response Journal, students explain how these images relate to the word hierarchy.

TEACHER NOTE To promote deeper understanding of the work hierarchy, you may wish to complete the Deep Dive at this time.

5 MIN.

Post the Focusing Question and the Content Framing Question.

Tell students that in this module they will explore identity through books set in the Middle Ages. Remind students of their exploration of the concept of “identity” in the last lesson. Explain that in this lesson, they will build knowledge of the Middle Ages to provide a context for the books they will read.

Students share their Welcome responses about the term hierarchy.

Learn55 MIN.

SUMMARIZE TEXT 25 MIN.

Ask and briefly discuss: “What do you think you know about the Middle Ages?”

Explain that the social order of the Middle Ages was a hierarchy.

Read aloud the first sentence of the first text: the excerpt of the seven paragraphs in the section titled: “The Middle Ages—The Medieval Years” (http://witeng.link/0700)

Ask students to try to determine the meaning of the word medieval using context clues. Then, provide the following definition for students to add to their Vocabulary Journal.

medieval (adj.) Related to the Middle Ages.

As you read the rest of the text, model questioning by periodically stopping to ask questions such as: “The beginning was called the Dark Ages? What would it be like to live in an age that’s considered dark?”

Instruct students to note in their Response Journal any questions that they have during the Read Aloud. After you finish reading, briefly discuss students’ questions.

Display Handout 2B.

Tell students they will reflect on what they just learned about the Middle Ages by identifying the central idea and supporting details during a second read.

Read until the end of the first paragraph, and conduct a Think Aloud to model how to identify the central idea.

To identify the central idea, I need to figure out what is being said about the topic, which is the Middle Ages. What point is being made about the Middle Ages? All the details here support information about when the Middle Ages took place. So, the central idea is: “The Middle Ages is the period from 476 to 1450.” That also makes sense because I know that the central idea is usually the paragraph’s topic sentence.

Read the second paragraph aloud, and ask students to identify the sentence that best captures its central idea.

n Life was very hard in the Middle Ages.

Now ask: “How does the author support this central idea?” Think Aloud to model how to identify supporting details.

What details support the idea that life was very hard? This says, “Very few people could read or write.” Life is more difficult when you are illiterate. It’s hard to communicate, and you have fewer opportunities. This supports the idea that life was very hard, so I’m adding that as a supporting detail.

Ask for other supporting details, and continue reading and collaborating to complete Handout 2B.

Central idea:

Life was very hard in the Middle Ages.

n The beginning was called the Dark Ages.

n “Very few people could read or write.”

n People did not believe they could improve their lives.

n People didn’t have laws to protect them.

n Many peasants were not free.

n “The Crusades were launched”; Christians and Muslims were fighting.

n Other groups were invading.

n “Almost half the people in Western Europe died from the bubonic plague.”

n “Medical care and cleanliness were lacking.”

Next, model how you might summarize the text.

The Middle Ages lasted about 1,000 years, from 476 to 1450. During this time in Europe, life was very difficult. People had little knowledge, freedom, or rights. They were in danger from war and disease. They had very little hope that their lives would change.

Highlight the important features of your summary and explain that effective summaries should:

Capture the central ideas.

List only the most important details.

Restate the text briefly.

Be written in the student’s own words.

Students write these features in their Response Journal.

Assign each small group a segment of the medieval social order—nobles, knights, clergy, tradesmen, or peasants—to study.

Provide each group with a copy of their respective text, or if students have online access, provide links to each text.

“

Nobles” (http://witeng.link/0701)

“Knights” (http://witeng.link/0702)

“Clergy (http://witeng.link/0703)

“Tradesmen” (http://witeng.link/0704)

“Peasants” (http://witeng.link/0705)

Have students read the text individually.

Differentiation:

If some students need support with this text, you may wish to group students reading below grade level, read aloud to them, and then support them as they complete the following activity.

Distribute Handout 2C.

Tell students that they will work in small groups to reflect on what they learned about their assigned social class by identifying the central idea about the identity of their assigned group and then recording supporting ideas and details.

Remind groups of their Discussion Rules, and provide the following sentence stems to facilitate conversations:

The “big idea” that I would box for this passage is …

I agree with that “big idea,” and I would add …

I disagree with that “big idea,” and, instead, I would box …

One supporting detail I would bullet is …

Another supporting detail I would bullet is …

Select a Discussion Rule that will be particularly helpful for small groups to follow, such as disagreeing respectfully. Ask: “What will you need to do in your small groups to follow this Discussion Rule?”

n To disagree respectfully, we need to use a kind tone of voice and not be rude about what we think.

n We should give a reason and not just say, “That’s wrong.”

n We should listen to what the other person says in case that person is right.

Small groups complete Handout 2C, identifying the central idea and supporting ideas.

Groups create a brief summary of their passage based on graphic organizers. (Provide length guidelines based on time.) Remind students to refer to the elements of an effective summary in their Response Journal.

Once groups have completed their summaries, revisit the Discussion Rule you identified previously. For example, ask: “How did you do with disagreeing respectfully? What could you do better next time?”

Then have students line up in front of the classroom by rank from the highest group to the lowest.

Have groups share their summaries, beginning with the highest group and continuing in order to the lowest ranking group. After each group shares, invite other students to ask questions to clarify their understanding of the central ideas about each medieval class.

Tell students that some thinkers described the hierarchy in the Middle Ages as being made up of three orders:

Those who fight

Those who pray

Those who work

Challenge each group to identify the group to which their class would belong, and display the results:

Those who fight Nobles Knights

Those who pray Clergy

Those who work Tradesmen Peasants

Pose the question: “Who would you be? Think back to the identity webs you created last lesson.”

Students complete the following 3–2–1–+ activity in their Knowledge Journal.

Write the three most interesting facts you learned about the Middle Ages today.

List two new vocabulary words you learned, and write their definitions.

Write one idea that is important about the Middle Ages.

Answer this question: “What was the structure of medieval society?”

Students read their remaining unread passages about nobles, knights, clergy, tradesmen, and peasants. Students write a one-sentence central idea for each passage.

Distribute and review the Volume of Reading Reflection Questions (see the final page in the Student Edition). Explain that students should consider these questions as they read independently and respond to them when they finish a text.

Students may complete the reflections in their Knowledge Journal or submit them directly. The questions can also be used as discussion questions for a book club or other small-group activity. See the Implementation Guide for a further explanation of Volume of Reading, as well as various ways of using the reflection.

The CFU assesses students’ ability to identify and summarize the central idea (RI.7.2). This is a key foundational skill that students build on throughout the year.

Consider collaborating with students working below grade level in a small group, asking questions such as, “What is this text mostly about? What idea do all these details lead us to believe? What is the author’s point here? What is the topic sentence?”

Time: 15 min.

Text: Online texts from Western Reserve Public Media: “The Middle Ages—The Medieval Years,” “Nobles,” “Knights,” “Clergy,” “Tradesmen,” and “Peasants”

Vocabulary Learning Goal: Use a Frayer Model to analyze new academic vocabulary and clarify its meaning using Greek affixes (L.7.4, L.7.4.b).

Display the following graphics:

Tell students to study the two triangles and then try to explain what they have in common. Direct them to jot their ideas in their Vocabulary Journal and then share them with a partner. Afterward, invite a few volunteers to share their ideas with the class.

n The picture on the left shows the importance of people according to their rank in life. The person at the top rules the people on the bottom.

n The upside down triangle shows the order of animals all the way down to cats.

n So both triangles represent the order of something.

n Both graphics show how groups are categorized or organized, except one deals with power and the other with physical traits.

Learn

Distribute Handout 2A: Frayer Model Hierarchy

Display a blank 4-Square graphic organizer with the word hierarchy in the middle. Explain to students that they will take notes and fill in their graphic organizers during the class discussion.

(n.) 1. a system for organizing groups, such as people, ideas, or objects, based on levels of their importance, power, or social standing

Like a pyramid, the most powerful person is at the top. While the least powerful person/people are at the bottom; the people at the bottom follow rules from those at the top

With things, items are grouped together by a common characteristic and then further broken down and categorized by other, less common characteristics.

Animal Kingdom: kingdom > phylum > class > order > family >genus> species [vertebrates > reptiles > snakes > cobra]

- US Army: president > secretary of the army > general > colonel > captain > lieutenant > etc.

- medieval social order: church/king > nobles/ clergy > knights/vassals > merchants/farmers/ craftsmen > peasants/serfs

monarchy (n.) a nation or government ruled by a king or queen. Mon–/mono– Greek affix meaning “one” or “alone.”

oligarchy (n.) a government or state in which a few people or a family rule. Olig–/oligo– Greek affix meaning “government by the few.”

patriarchy (n.) a social system in which a father rules, and descent and succession are traced through the father. Patri– Greek affix meaning “father.”

Many students may struggle with note-taking because they have difficulty gauging what information is important. Guide them through the process by posting essential points from class discussion. Explain that whatever is written on the board is important and should be noted on their graphic organizer or Vocabulary Journal.

A Frayer model for hierarchy has been completed for you in this lesson to help you determine what to use for your displayed notes and class discussion.

Remind students that, when learning a new word, it helps to review its affixes and roots. Display the Latin affix, hier–, and Greek root, archy, for hierarchy. Then explain that the word hierarchy is made up of two morphemes. The affix hier– is a Latin prefix meaning “leader of sacred rights,” and archy is a Greek root meaning “first in rank or time.” Have students copy the information on their graphic organizer in the Definition square.

Extension:

After the morphology review, invite students to brainstorm other words with the morphemes of the word hierarchy Explain that their prior knowledge of morphemes can help them determine a word’s meaning and learning a new morpheme can help them learn new words.

http://witeng.link/dictionary and http://witeng.link/wordsmyth are two good resources for finding morphology information.

Ask: “How do these morphemes connect to the meaning of the word hierarchy?”

Allow students ample time to think or discuss the possiblilities.

n A hierarch is a leader of sacred rights that’s first in rank.

n Hierarchy means a group ruled by a holy person that’s the high-ranking leader.

n It refers to a sacred order ruled by a high priest.

n It could mean an organization ruled by a leader of sacred rights.

Display the dictionary definition of hierarchy for students to copy in the Definition section of their 4-Square organizer.

Explain that the word hierarchy has multiple meanings. In reference to the medieval era, it is a system of people or things ranked one above another. Today, hierarchy could refer to any system of people or things that are ranked or categorized one above another, as in the animal kingdom models above.

Tell students to prepare to take notes in the Characteristics section of their 4-Square organizer. Display the underlined information below as you discuss.

Say: “If you were to map out the medieval hierarchy, it would look like a pyramid. The most powerful person or people are at the smaller top of the pyramid. Can anyone tell me why this is so?”

n Because there are only a few important people at the top.

n Because there’s usually only one ruler or a handful of people making the rules compared to the number of people that follow.

n The peasants and serfs make up the majority of the people, so they are at the bottom—the larger part of the pyramid.

n Most of the people, who are at the bottom of the pyramid, follow the rules made by the ones at the top.

Guide students as needed to understand that the least powerful people are at the bottom, and they follow rules appointed by those at the top.

Students pair up and complete the remainder of the graphic organizer. They should include the following:

1. Under Characteristics:

Additional characteristics reflecting the first definition of hierarchy discussed in class.

2. Under Examples:

At least two examples that represent the two meanings of hierarchy discussed in class.

3. Under Nonexamples:

At least two other types of governments whose labels end in the suffix –archy Brief definitions for the two examples. The meaning of their prefixes.

Circulate to assess understanding and offer guidance as needed.

When finished, volunteers offer their nonexamples, definitions, and roots/prefixes. Address misinformation as necessary.

If time allows, discuss whether we live in a hierarchy today, and ask students to explain why or why not.

Castle Diary: The Journal of Tobias Burgess, Richard Platt, pages 7-29

Welcome (5 min.)

Launch (10 min.)

Learn (45 min.)

Notice and Wonder (25 min.)

Experiment with Figurative Language (20 min)

Land (10 min.)

Express Tobias’s Identity

Wrap (5 min.)

Assign Homework

Style and Conventions Deep Dive: Examine Concise Writing: Recognize Precise, Concise Writing (15 min.)

The full text of ELA Standards can be found in the Module Overview.

RL.7.1

Speaking and Listening

SL.7.1, SL.7.6

Language

L.7.5 L.7.3.a

MATERIALS

Handout 3A: Recognize Precise, Concise Writing

Formulate questions and initial impressions of Tobias’s identity based on Castle Diary’s first entries (RL.7.1).

Create Tobias’s identity web based on textual evidence.

Use figurative language to express personal identity in a poem (L.7.5).

Write a poem modeled after “Identity” by Julio Noboa Polanco.

Recognize and explain the difference between precise, concise prose and wordy writing (L.7.3.a).

Compare paragraphs for precision and conciseness.

FOCUSING QUESTION: Lessons 1–7

How does society influence identity and experience?

CONTENT FRAMING QUESTION: Lesson 3

Wonder: What do I notice and wonder about Tobias Burgess?

CRAFT QUEST ION: Lesson 3

Experiment: How does figurative language work?

Students begin reading Castle Diary, annotating and discussing what they notice and wonder. Students also continue to work on figurative language by taking the identity webs from Lesson 1 and writing a poem with figurative language based on “Identity.”

5 MIN.

Have pairs share their Knowledge Journal entries about what they learned about the Middle Ages in the last lesson. Invite them to add information based on what they discuss with partners.

10 MIN.

Post the Essential Question, Focusing Question, and Content Framing Question.

Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share to restate the Essential Question in their own words.

Explain that this module’s texts all center on identity during the Middle Ages. The first text, Castle Diary, is centered on Tobias Burgess, a young man growing up during that time period. Explain that this is a work of historical fiction, written recently, yet set in the Middle Ages.

Invite a few students to share what they learned about the medieval social hierarchy in the last lesson.

Remind students about the Notice and Wonder T-Chart they used to analyze the poem “Identity” in the first lesson. Reiterate that when beginning a new book, it is important to pay attention to all its details to help determine what the book is about. Explain that the information on the front and back cover gives readers a preview.

Distribute Castle Diary. Instruct students to Think–Pair–Share, and ask what they notice and wonder based on their examination of the front and back cover details.

Display the following T-chart, and add student responses. Have students create the same chart in their Response Journal.

Notice Wonder

Characters

n There’s a boy on the front trying to walk on stilts.

n On the back, it says he keeps a detailed journal of what happens to him at his uncle’s castle.

Setting n On the back, it says it’s the year 1285.

n The back also says he’s going to be a page in his uncle’s castle. We read about pages in our “Knights” group last time.