Sofía Gandarias

45

Carlos Fuentes To Sofía Gandarias: art against violence

A Sofía Gandarias: arte contra violencia

Cntemporary "s treet art" and the art of antiquity share two things: they're unsigned and they don't make any pretense of being original. Fruit of the humanistic superiority of the Renaissance, to pur one's name on a painting or sculpture was an innovation of the collective and anonymous spirit of the Middle Ages. Name and surname, says Montaigne: the cult of me-ism is a feature of western modernity, and despite Pacalconsider it "detestable."

El arte popular y el arte antiguo se asemejan en dos cosas: son anónimos y no pretenden ser originales. Resultado de la soberbia humanista del Renacimiento, tener un nombre y ponerlo al pie de un cuadro o de un monumento es una novedad para la tradición colectiva y anónima de la Edad Media. Nombre y sobrenombre, dice Montaigne: las aventuras del Yo son las de la modernidad occidental, por más que Pascal lo juzgue «detestable».

Regardless, nobody signed the cathedrals of Chartres and Aachen, nor the unassuming "retablos" of the Mexican baroque churches. Entire schools and workshops of the late Middle Ages declare themselves to be Masters of the Legend of Saint Ursula, Masters of the Magdelene. Names, surnames, and images quickly vanish in this spirit of modesty. Avoiding the obstacles of this solipsism, the great European portraitists give to art a social function, occasionally even democratic: we gaze at faces that otherwise leave neither proof nor witness to their passage on earth. A times they acquire a dimension so intimate it projects a kind of melancholy, as with the self-portraits of Rembrandt. Spanish artist Sofia Gandarias, working in the great tradition ofVelazquez for whom the portrait was a mark of identity, proof of existence and ironic balancing act between infamous notoriety and visible invisibility, between monarchy and anarchy, Philip IV and the masked functionaries of God, between Carlo IV and the lovers of the Festival of

Carlos Fuentes was a Mexican novelist and essayist. Fuentes received the Rómulo Gallegos, Cervantes, Prince of Asturias, and Four Freedoms Award, among many other.

#9

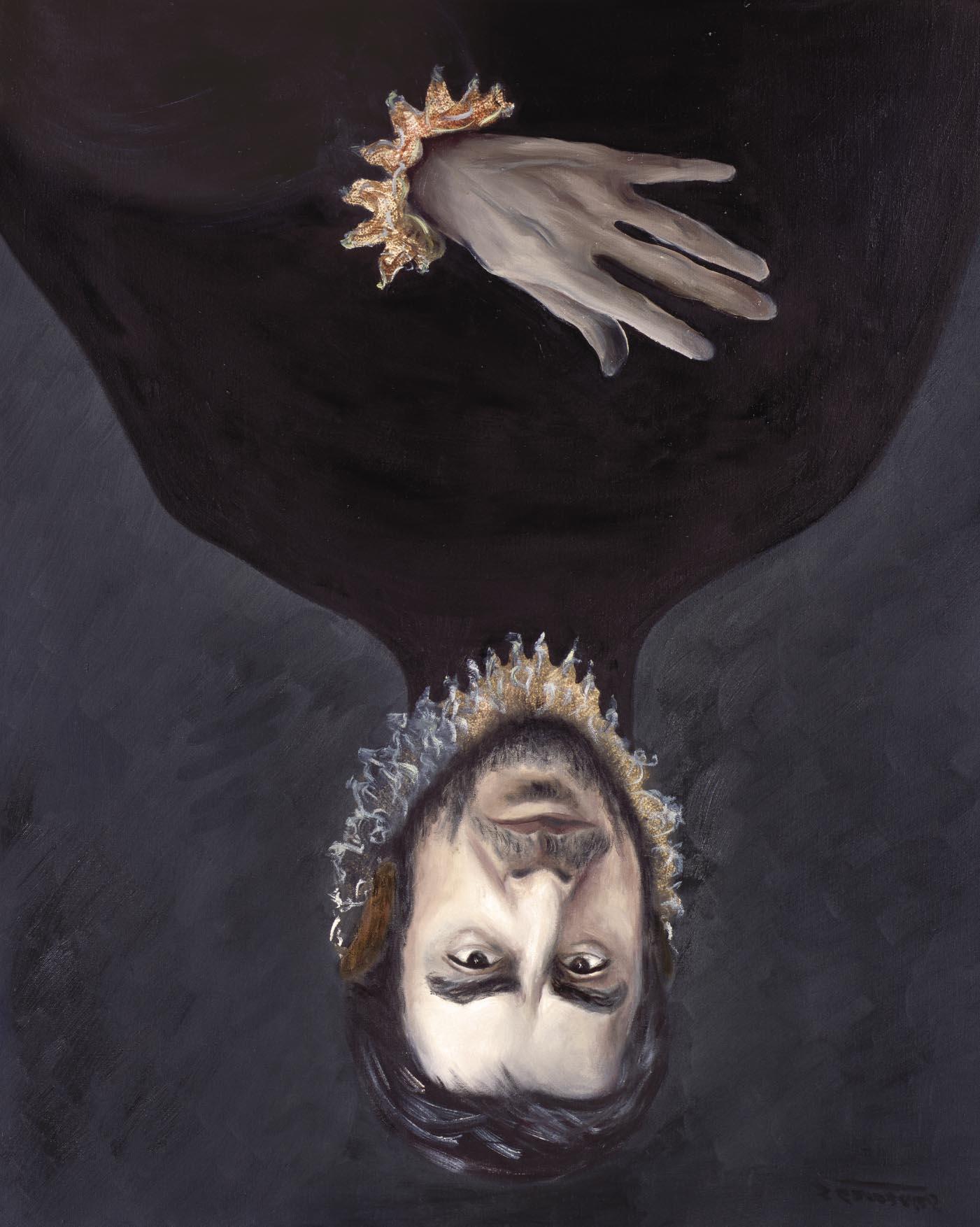

El Caballero Javier Bardem Óleo sobre lienzo / 100 x 81 cm. / 2014

En cambio, nadie firma ni las catedrales de Chartres y Aquisgrán, ni los modestos retablos de las iglesias barroas de México. Escuelas –¿talleres?– enteros del otoño de la Edad Media se presentan como «Maestros de la Leyenda de Santa Úrsula», «Maestros de la Magdalena». Nombre y sobrenombre, hubris, facies, despiden pronto esa modestia. Evitando los escollos del solipsismo, los grandes retratistas de Europa le dan a su arte una función social, a veces hasta democrática: aquí está el rostro que, de otra manera, no tendría evidencia, no dejaría rastro de su paso por el mundo. Le dan, a veces, una dimensión tan íntima que se proyecta con melancolía: los autorretratos de Rembrandt. Sofía Gandarias, en la gran tradición velazqueña, española, del retrato que es seña de identidad, prueba de existencia y ejercicio irónico entre la fama infame y la invisibilidad visible, entre el monarca y los anarcas, entre Felipe IV y los obreros disfrazados de dioses, entre Carlos IV y los enamorados de las fiestas de San Isidro, nos ofrece retratos de nuestro tiempo en los que la figura y su

Carlos Fuentes fue un novelista y ensayista mexicano. Fuentes recibió los premios Rómulo Gallegos, Premio Cervantes, Príncipe de Asturias y el Four Freedoms Award, entre muchos otros.