To Barbara

To Barbara

On different canvases, positioned metaphorically for pictorial evidence and examples from art, we turn to a question that has been raised again and again, and that has provoked long and ongoing discussions in the cultural archive of our civilization. Between the suspicion of being an object of addiction, cult or idolatry, and the conviction that the materialization and incarnation of ideas and the transcendent are also part of active life, the dispute about images and image criticism prevails to this day. For images have always made a difference. What humankind regards as truth did not come into the world naked, as a late antique writer already knew, but it came into the world in symbols, images, or idols, and according to this gnostic interpretation, this world will not be able to receive truth in any other way than through images.1 The power that the image has exerted on we humans throughout the ages is, in its Janus-facedness, virtually a mark of modernity, too, which made Paul Valéry think of the pictorially “mad light effects of the great cities of the time.”2 Power likes to frame things: Whoever determines what may be shown has the say politically and discursively. Whoever defines perceptions has control over people’s senses and their cultural orientations. But this depends on the cooperation between transmitter and recipient. The fact that the latter may not believe their eyes points to the flip side, namely that images could also turn out to be dubious testimonies and falsifications. That photo manipulation and image falsification are as old as the respective techniques is a wellknown fact, as are the methods both analog and digital used to expose forgeries or to prove their authenticity and provenance.

Ultimately drawing on a far older political theology, an interpretation today seeks to set itself apart from such claims to power and such legacies through media- critical thinking. The ambivalence, as it speaks of the image controversy, cult prohibition, and art consciousness, can be aptly characterized as a cultural-historical “economy of the sacred”3 and lives on in precisely this duality, it seems to me, in the post-religious concepts of critical image- and cult- discourse of the moderns. In order to understand the might and the menace of images these two big “M”, between which the iridescent third “M” of the Magical oscillates it does not suffice to consider only the last few hundred years in this tense relationship of image controversy, cult prohibition and art consciousness.

As commendably as critical studies today are concerned with three other “M”s with the social and economic historical understanding of art between market, moneymen, and mu -

seums and also discuss the manipulation of the visual worlds 4 , attention is given here to a more far-reaching cultural-historical consideration. My aim is to trace man’s inherently contradictory and guilt- engendering “mimetic desire”, as René Girard puts it, in religions and rituals, cultures and politics from Antiquity to Modernity. For this desire, that is mostly oriented towards sacrifice and the cult of sacrifice, is by no means mere imitation, mere depiction.5 Rather, it also opens up a history of vandalism and destruction that has long been marked by violence and “scapegoats,” by cult productions and the destruction of images. After the Holocaust, all this confronts us today as an abyss in the consciousness of the present past.6

Images from war zones, crimes scenes, torture, or natural disasters are often gruesome and distressing. When an imagery is traumatic, events that are happening far away can feel like they are seeping into one’s brain or body. Disgust, fear and powerlessness may spread individually or collectively, and they are not unusual even for highly resilient professionals like journalists and forensic analysts working with such images or materials. Vicarious traumatization, when exposures are repeated, can even then cause traumata as secondary effects. It is important, however, to understand that trauma cannot be diagnosed in individuals alone, as doctors, brain researchers and psychologists are fortunate enough to be able to do, but rather that it is a social and moral category that tells us about the political consequences and civilizational impacts in past and present. The claim to truth and the lies in such imagery are mixed, and repression and forgetting go hand in hand with a politics of memory that dictates what is to be seen and communicated, or what is not to be said and what is not to be named. Might and menace intertwine in a peculiar way, power and stigma appear as political twins: Past crimes and disasters can be used by a mighty sovereign for healing, recognizing the unjust and strengthening the reconciliation, or on contrary, the remembrance of horror and dishonor can be misused to invoke idolatry, violence, blame, corruption and the preservation of power.7 But in the long term, this claim by the sovereign as to what should and should not apply cannot usually be upheld. In other words, although history tells us about the triumph of the victors and sovereign power, but it is the trauma of the defeated and injured that often guide our remembrance, insights and discoveries in later times. We moderns are characterized by this deep-rooted ambiguity: In view of the dialectic of triumph and trauma, we may dream but still in the wrong way to be in possession of the lance of Achilles the lance that wounds and heals, that kills and resurrects, as told in an ancient myth (Ovid, Metamorphoses 12, 112; Kyprien). The Talmud express this ambiguity likewise when the rabbis are asking whether God first created the remedy before striking a wound in his creatures, or vice versa (Massechet Megillah 1:13b). In all such moments of history and storytelling about the past, the interplay of triumph and trauma says something about the way political power deals with the hopes of citizens or subjects and thus about the images and art works in which the sovereign may recognize himself or against which he acts with destructive rage. Images, especially figurative art, as carriers of emotions of a religious, cultic or collective kind, obviously play an important role in the social and frequently conflict-ridden transformation of the world. Here is not the place to decide whether we are talking about “religion as art” or “politics as art” or an “art of the religious and the political”, in other words: an implied aestheticization of the world in images. Moses Mendelssohn already subsumed his theory of signs under the term of an “aesthetics of religion” in order to mark the distance between the alleged bases

1 Neta Harari Navon painting one of the 18 panels of Judgment Day, Tel Aviv 2020; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

of truth and the political desires of the people.8 However, the fact remains that over the centuries, in countless debates, a way had to be found to understand religions and cults as a cultural system of texts, images, rites and symbols and to understand it in its literary, artistic, musical and theatrical creations. Images played an essential role in this. What we call today with the term “myth” was always an appeal that what was told or drawn into the images must not be repeated and must not happen again as a tragic experience. This presupposes the understanding that symbols and myths are merely a means of communication and must not be confused with the meaning of what is meant, or with a reference object, or an actual event. The conflation of a symbol with what is actually intended would fatally lead to the deities being taken most personally, much ink being wasted unnecessarily out of zeal and precious human blood being shed. This is why the human mind wants to recognize myths, symbols and images critically as tempting and seductive as an insulting insistence on justifying the preferred images and narratives as if they themselves were the message they convey.

Thus understood, myths are also a useful attempt to enlighten, to enforce and to forge new alliances with higher powers. That is why the Enlightenment has used and is still using images and narratives from mythical materials to bring counter-narratives into the arena, often proclaiming them to be forward- looking to human progress. Myths then serve to assert the infeasibility of failure and to illustrate the Enlightenment as a necessity, that is, to present history as a “real” event and as a social reality. Paradoxically, therefore, myths their narratives, their

Prologue to an e xcursion into the h istory of c ulture

images are at the same time a seductive risk, if they act as a revocation, as an addiction to cult concepts believed to be eternal and to prevent alternative ideas.

Images played and still play an essential role in this process of enlightenment described by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno.9 The assignment of their functions in historical and political contexts was and remains helpful in situating the emotional triggers that lead to the production of images and are induced by images. For such triggers point to a struggle for the domination of emotions, for achieving such sovereignty as allows for political communities and individual states of mind to be effectively controlled. This struggle was and still is a struggle for and against images, and it was and is theo-politically, or cultural-politically, intended, depending on the time and space in which this confrontation takes place. When friends or enemies of images stood up for their convictions in different historical eras, to the point of losing their lives, this indicates the seriousness of such disputes. Images, especially images of gods, are not then merely an illustration of religion; rather, they are the object of faith itself or of a worldview about which the dispute is fought.

The idea of how to deal with pictorial representations and sculputural, three- dimensional objects in cultic practices has led to differentiations at different times and in different local spaces, but from the outset in all religious cultures and their chains of tradition. In not a few traditionalist societies, for example, there are requests not to be painted or photographed for fear of thereby losing one’s soul or suffering harm or depriving the community or a shrine of its vitality. Images with sacred content, which have the manifestation of the deity as the object of representation, have by and large always attracted iconoclastic criticism. This criticism took the image seriously, since the image signified dominion over the deity. What happens to the image, what is added to it or taken away from it, then applies to the deity itself. A deity’s name itself is also a significant means of gaining power over the deity and people. And yet, or perhaps because of this, the status of three-dimensional sacred representation, such as statues of Caesars and figures of saints that seemed identical to images of God, has always been controversial. Within Judaism as well as within Christianity, this led to prohibitions of the works of art suspected of being idolatry, which then led anew to a tempering and to artful differentiation in order to partially relativize the strict prohibition.

This ambivalence also resonates in the case of the representation of secular rulers in images and on coins, stamps, or through statutes. The might of the Caesars demanded faces that could be seen and vouchsafed the value of money and the stability of political relations. This is especially evident in broad territorial and trading areas. Thus, in the aftermath of Alexander the Great’s Asian campaign, ancient Indo- Hellenistic, Indo-Scythian and Indo- Roman coins with corresponding portraits of gods and rulers testify to the commercial-political outreach into the area of present- day Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.10 Even in today’s democracies and, above all, dictatorships, such a globalizing control of images is still evident, despite the sacrifices they left us, thus increasing mimetic desire. The communist leaders of the 20th and 21st centuries have been displayed as mummified idols in mausoleums in Moscow, Beijing and Pyongyang lifeless “relics” of the supposedly salvific path of “their” peoples. On the other hand, in Antiquity, the veneration of images of emperors as images of gods was highly offensive to those newly emerging religions that feared an invisible or at least intangible god. However, this in no way

hindered the proliferation of Caesar images. According to Mary Beard, before the end of the 19th century there were “more representations of Roman emperors in Western culture than of any other personages, apart from Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and a handful of saints”.11 They can be found on portraits and paintings, as busts and statues, on bowls, tapestries and inlays, in cabinets and classrooms, as utilitarian and propaganda pieces, in stage productions and feature films. And ever since cinema has existed, Antiquity, first of all the Roman Empire and then the ancient cultures of Egypt, Israel and Greece, has played a significant role in modern feature films. The materials from Antiquity and their images and narratives serve to play the contemporary game of projection and identification in the definitions of the heroes and villains. This book discusses an example that addresses this relationship through irony and as comedy.

In Antiquity itself, images of the emperor had been closely linked to the question of sovereignty. The first panel of Aby Warburg’s pictorial atlas Mnemosyne points back to even earlier times, showing Babylonian boundary stones decorated with constellations which are identified with portraits of rulers.12 Midrashic or Talmudic stories and parables vividly recount the punishments to be expected for violating or mocking the Babylonian or Roman imperial statues those who did so deliberately faced death, those who were guilty by oversight were sent to the ancient Gulag, that is, “driven into the mines.”13 This Talmudic advice to be cautious, which implicitly expresses criticism of rulers and their images, was taken up among the moderns by Erich Fromm, for instance, and developed in the normative humanistic sense through the connection he made between a ruler’s desire to pose and be portrayed as God and totalitarian dictatorships.14

Speaking from the perspective of the gods and their earthly representatives however, their mockery by the people was again connected with the risk that the gods would avenge themselves and show their might to those who despise and insult them. Sacrilege in images was always a sacrilege against the deities or Caesars themselves. It was not until the Enlightenment that this identification of the actions of the gods and the actions of humans was dissociated the gods were then supposed to deal only with gods, humans only with humans. However, this did not discourage people from wanting to act like gods. For it is no less true of the dictators and theocratic states of the present day that the sacrilege of images is still a sacrilege against their power as rulers. In contrast, the theory of the democratic state works based on the values of liberal ideals and mostly quite well without emperors and without gods. Their statues are taken down from their pedestals and then deposited in museums, where they join the busts of generals and philosophers. However, the world of liberalism is far from being a majority everywhere or sustained by the necessary prosperity. The warlords and dictators in worldly and clerical garb have not disappeared. Their images on monumental banners, on television and the Internet are still with us. Thus, our present, confronted with the fact that our world is determined by images and image controversy, is strangely bound up with all sorts of variants of historical theology and philosophy, which justify or shore up the political field.

The telos of historical and current narratives therefore touches on the essence of the Jewish and on the posit of idolatry prohibition, namely the deep aversion to the figurative idolatry of humans and materials. However, Judaism’s supposed imagelessness or image remoteness is all too hastily asserted and ascribed to the field of art. This is the observation that opens this book. Admittedly, one will not be able to understand or deconstruct this forgotten or re -

Prologue to an e xcursion into the h istory of c ulture

pressed view, which spoke of the “God of the Jews” and was the guiding idea of aesthetics as well as theology in the 19th and early 20th centuries, without at the same time bearing in mind the pronounced controversy in the Christian traditions and among their theological thinkers. Attention is paid to this matter too. In Western culture, contentious issues pertaining to so - called “orthodox” and “heretical” tendencies in the various Christian cult communities have meant that those involved have had to deliberate with or against each other regarding what they see as constituting the essence of the image. Attention is also paid to their thoughts on images, since they testify to a high intellectual awareness of the aesthetic, theological, and religiophilosophical implications of Christian cultures.

Negotiations of this kind are also recognizable within the Jewish communities. Moreover, especially in Apocalypticism and Messianism, which are related to questions of likeness and images, there are likely to be mutual Christian-Jewish influences. In the midst of dark times, at the end of the 1930s, the historian Raphael Straus noted, in opposition to any theological apologetics and ethnic segregation, that the relationship between the two traditions could only be clarified “if the observation of difference between religions is not permitted to obscure the commonality of religion.”15 For this purpose, he recommended the metaphor of “neighborhood” to illustrate the necessity of the cultural-historical contextualization of the mutual theological, religio-philosophical and liturgical expressions. No small part is played by the function of the smuggling of knowledge, materials, and narratives, in addition to the open dialogue and more intimate exchanges. The sometimes clandestine interactions between Jewish and Christian as well as Islamic cultures in the different epochs of our history have increasingly come to the attention of research, museums and the public in all their facets.16 To cite a contemporary example as well: In 2015, the Israel Museum exhibited works by prominent Jewish artists spanning nearly two centuries, documenting cross- generational perceptions of Jesus from the European Jewish, Zionist pre- state, and Israeli artistic worlds.17

Whatever transpires in the end, questions of art, cult images, and the prohibition of images are particularly pertinent, even if the rosebush of art is punctuated by more than a single bloom and meanwhile the thorns prick at the same time. For images can be understood as aspects of cultural practices in which every day human life as well as the exchange of ideas take visual shape in the forms of interpersonal communication. Wherever the human soul drew breath and expressed its success or failure in creative form, images necessarily emerged. It is therefore incumbent on us to understand the fractal intelligences of art, religions and the humanities in all their multiplicity.

To tarry in the language of the political: A concept of tradition that assumes that all truth has already been defined is not to be found in any historical epoch. Neither Judaism nor Christianity in their respective Eastern and Western forms nor Islam, Buddhism and the reform movement in Jainism18 , which I very rarely discuss in this book can be assigned in their core to the camp of the friends of images or the enemies of images and thus to a definable geopolitical and cultural-political space. Rather, they are all characterized by the question of how the understanding of images in cultic and ritual terms can or cannot be expressed and lived. Such a differentiating view, however, was not self- evident for a long time. Moreover, they were overshadowed by linguistic, local and ethnic differences, shaped by different customs and mores. We today,

however, should pursue a different endeavor. At the turn of the 20th century, Georg Brandes, the Danish-Jewish literary and cultural scholar who died in 1927, described the task of the observer and researcher as being to strive for the “dual quality” of “approaching the unfamiliar in such a way that we can appropriate it, and distancing ourselves from the familiar in such a way that we are able to survey it”.19 To take into account different strands and to identify their common characteristics is thus both necessary and fruitful. For this in turn permits insights into the historical and current process of emancipation in this case into the gaining of autonomy for the artist and for the work of art as a novel set of beliefs of secular modernity and bourgeois culture. This trend towards the autonomy of the arts was probably already initiated in the early modern and even before the Reformation era. The fact that the arts and their purpose have been, and continue to be, harnessed for the glorification of the religious is not a contemporary phenomenon: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe already saw the autonomy of the artist threatened by the theses of Romantics such as Friedrich Schlegel, Ludwig Tieck, and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, and denounced the mixing of art with religion as a “monkish mischief.”20 The transformation of art into faith has thus at all times affected the quality of images and given rise to enthusiastic approval or disapproval. “The truth is ugly,” wrote Friedrich Nietzsche, whose criticism of religion was sharp and prvocative, but “we possess art lest we perish of the truth.”21

In view of Nietzsche’s harsh utterance, Max Brod “finally found freedom and relaxation of the soul” in Robert Walser’s new tone of writing, in the images of the “sweetest cheerfulness”, which appeared to him as the “Romanticism of our last, Arcadian-imbued spirit.”22

In all such disputes, it becomes apparent that images and image prohibitions served the purpose of self-assurance as well as the justification of claims. In this and beyond, their other, aforementioned side is revealed here. Images have always represented the sovereign himself, embodied his presence as bearer of power, provoked revolts against such images, and brought accusations of blasphemy into the room. Effigies continue to do so today. The indicators, or, if you like, the historical witnesses of such ambivalences, are conceptual pairings such as stigma and miracle cure, icons and violence, incarnation and blasphemy, from which promises of all kinds, the terror always breathing down one’s neck, and the hope for redemption pressing from within, could speak in equal measure through images and against images. The fact that there are images of an act of violence and at the same time of hopes and promises that address a viewer also identifies images as social entities that always have a taint attached to them. The power of images is necessarily bound up with questions about the stigma, the taint, the scars of these images. Flesh and sacrifice, in ancient myths always associated with incarnating deities or at least mythical saints, suddenly appear among the moderns as mass self-harm by humans, as this became real in world wars and genocides and has been remembered ever since by means of visual and linguistic images. This communicative conception results in a chapter on the features and limits of Holocaust remembrance, which is to a significant extent bound up with questions of triumph and trauma, i. e. the power and taint of images. Whether images in films, photographs, and works of art depict the imagination of terror and horror or rather eliminate them is no trivial question, in equal measure as the insight that the Holocaust can be explained in principle but has never been fully explained and probably never can be explained in our speech i. e. in our writings and images.

Prologue to an e xcursion into the h istory of c ulture

The representations and reflections in this book do not consider images as a reality set apart from other domains, which are just as justified to be seen as expressions of reality. Rather, images are part of a much broader whole and, understood in this way, are open, multi-layered, and contradictory in their expression. The contemplation of images offers us selective insights that go beyond the image and point to complex implications. It demands approaches from us that allow explanations never to be unambiguous or formalistic or even definitive. Thus, we cannot simply reason from the motifs and forms, but must take into account the production, dissemination, and readings of the images. All these contradictions, in which ambivalences and disputes are expressed, are the reason for my reflections. I want to contribute here above all to the insight that the “reading” of images must be practiced, because reading images is as much a technique as the making and banning of images. The resulting work published here is by no means exhaustive and is indebted to several works in the field of these controversial issues. We should keep in mind that the reference to the pragmatic- social-historical context always forms the framework when images and text are to be interpreted the philosophical and theological hypostases follow as “histories of ideas”.

The transformation of the sacred into concepts of humanism, the reshaping of ideas of tradition into perspectives of evolutionary history and secular interpretations of the world, as well as the self-assertions of human beings vis-à-vis an absolute divine sovereignty all this can be seen in extrapolations and reinterpretations of texts that seek out the new in the old and seek to transform the old into the new. These processes of cultural and social history become at least as graphic and accessible in the production and contemplation of images that bear witness to the birth of Modernity. This beginning does not only derive from the spirit of the Protestant confessions in all their manifestations, it can also be read in very early Jewish, Catholic and Orthodox Christian birth pangs since the Antiquities.23 It is rooted in the struggle against cult imagery, as it was in ancient Israelite prophetic literature, to emphasize the Mosaic idea of God. So, we should not ignore the contrasting pagan environment in history as well as current neopagan customs. But it would also be of interest to seek out corresponding conflicts in Islamic, Jain, and Buddhist archives of our cultural worlds, which have their own imagery but are not to be understood in isolation but, on the contrary, in a context of reciprocity as they struggle to sustain and reform their cultures.24 To generalize: The cultural-historical crux lies in understanding that many people were and still are convinced that it is not the knowledge of truths that is particularly important, but salvation and its desire for images and miracles. “Again and again, in the development and unfolding of religious consciousness, the religious [cultic] symbols are at the same time thought of as carriers of religious powers and effects,” Ernst Cassirer notes, when it comes to the interlocking questions of expectations of salvation, cultic images, and destruction of images.25 If my book contributes to these often- opposing processes, if it illustrates the transformation of the sacred into different, sometimes contradictory narratives in the secular pictorial thinking of Western modernity, and if it in some way captures the heated debates about the concept of the image, it will have fulfilled its purpose. It does not follow it should be emphasized a continuity conception of history or the representation of sequences of individual epochs. It does not treat cultural- historical representations as hermetically sealed chapters Christian, Jewish, bourgeois or the modern world, cleanly divided into disciplines, spatial zones,

That one’s own culture should deem all ideas and expectations of former civilizations superseded and irrelevant turns out to be an immodest, unsustainable conviction, which merely consigns to oblivion concepts previously utilized as useful. We forget and then we repress the fact that we have forgotten. But we are caught up unawares by such a lapse, forcing us to remember all over again. The pitfalls of such a process must be considered. From Marcel Proust we have the insight that involuntary forgetting can turn into an intense memory, whose images then appear more real than the reality that was repressed and forgotten. Walter Benjamin’s reading of Proust led him to the paradoxical formula that these are “images that we never see before we remember them”.26

To conclude the introduction about memory calls: My writing is, as it were, the expression of a nomad who wanders through an imaginary, yet fact- strewn, exhibition of different times and spaces in order to testify to the mutual dependence of different cultures across times and spaces. In doing so, I expose myself to the risk of being considered a dilettante, and, in a way, I am, since I have neither the competence nor the intention to appear as a worthy representative of one or the other discipline in my border crossing approach. At best my claim is to follow and understand to some degree the sources, commentaries, and scholarly discussions. What I offer are memory calls that can be summarized and given concrete shape to the extent that the memories presented are understood as a history that hasn’t faded, that unfolded and is still unfolding in images. In the sense of Aby Warburg, the creator of symbol theory and image science, who himself oscillated between the histories of art, idees and religions as well as anthropology and other disciplines, images can be read as living symbolic forms and can, as it were, also be understood “biologically”, i. e. as inescapable testimonies of human existence.27

Times and spaces separate epochs and cultures, but the images therefrom enter a dialogue and evoke associations that, in the sense of Platonic dialectics, inspire imaginary conversation. We find ourselves, as it were, on a journey through these times and spaces. The reader will often have to hop from one exhibition space to the next in order to combine a linear and associative understanding of history and culture. I might have been tempted to write a script consisting only of quotations and canvases presenting motifs and fragments, or even better, of comments on images and pictorial thinking, as the traditional Jewish melitzah often does with traditional written material. It has become more than a colorful mosaic floor of little gems from the Torah, rabbinic literature, Christian and post-religious narratives, secular reflections, and from the liturgical formulas of academic convention. Yet and this is what mattered to me the intertextual and intervisual character is preserved, as is the charm of a guided exhibition or excursion. Anyway, instead of strictly cultural and pictorial continuity considerations, I present my skittish and looping perhaps calls of memory, in order to hopefully draw stimulating insights from the archive of our cultural histories, which readers in turn may continue to weave themselves.

Prologue to an e xcursion into the h istory of c ulture or periods of time. Without disregarding such chronological or disciplinary orders, which are indeed valuable for analytical criticism and make for professional readability, I rather lay out approaches and themes that can lead in several directions. For arguing conceived chronologically only would lack the simultaneity and coexistence of different cultures or religions.

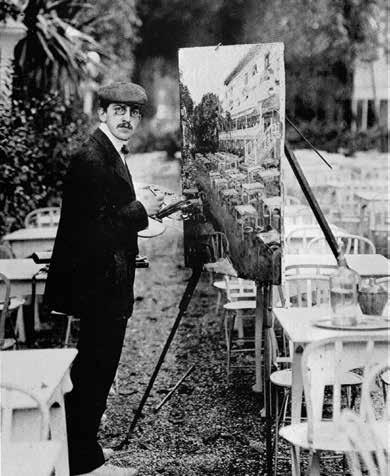

Between 1905 and 1930, a circle of artists from numerous countries of origin came together in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. Among them were Chaïm Soutine, Michel Kikoïne, Amedeo Modigliani, Jules Pascin, Marc Chagall, Emmanuel Mane- Katz, Rudolf Levy, Jacques Lipchitz, Sonja Delauney, Max Weber, Walter Bondy and forty other artists (see fig. 2, 10, 43, 95). Almost all of them were Jews from different regions. Some came from middle-class families in western, eastern and south- eastern European cities, others were from poor backgrounds, and many of them moved into La Ruche, a run- down building in the 15th arrondissement, where they published their own magazine, Makhmadim all driven by the hope of finding success with their art. Scholarly publications in Europe understands this circle as a kind of multinational community of fate, by which Jewish identity could be expressed through artistic nuance but also faded away due to migration from East to West.28 The artistic community, often described as “cosmopolitan”, is at the same time characterized in publications as specifically Jewish, as a “Jewish enclave”. One claim, however, is noteworthy: It is argued in particular that the newly conquered formal and technical means allowed these painters to articulate their feelings and to overcome Judaism’s imagelessness and hostility towards the image and art works. In the constellation of the 1920s, as art historians like to say, “the Judaism that had seemingly been condemned to imagelessness,” was able to create its “special angle” by expanding magical experiences of things into the lyrical and legendary of painted images. 29 In the particular case of Soutine (fig. 10), for example, an alleged Jewish- orthodox hostility to images is claimed in order to characterize his path from a childhood in a Hasidic family to becoming a “cosmopolitan” artist; yet it was rather poverty, hunger and violence that led to a lack of interest in art, which was considered useless, in the small town of Soutine’s birth, as a contemporary Yiddish journalist, Hersh Fenster, reported in 1951.30 The same claim of “Jewish iconoclasm” directed against art is presented in a similar way at art retrospectives in other places. For example, an author whose writing appears in an accompanying volume to a retrospective at the Aargau Kunsthaus of the work of Swiss-Jewish artist Alis Guggenheim (fig. 41) argues in the same vein as respected art historians. In the preface, considering local family and village pictures that show scenes of Jewish life, the author emphasizes that the artist’s pictorial ideas would have emerged in dialectical opposition to a tradition shaped by an abstinence from pictures and prohibition on images.31

2 Walter Bondy, around 1907, painting the “Jardin Bleu” at St. Cloud; Artistes Juifs de l’École de Paris.

We now offer some evidence from literature and philosophy to illustrate our theme, the aforementioned “ban of images” or “Jewish iconoclasm”. First, there are three canvases that serve as introductions to the stated assertions. Others will follow.

First Canvas: Horror and Holiness

In Joseph Roth’s novel Tarabas it is not those who destroy cult images whom the peasants and soldiers’ rail against as “enemies”, but rather those who renounce the cult of images and refuse to venerate them. A pogrom soon ensues. The scene: Soldiers amuse themselves in the barn of a Jewish innkeeper, who is absent because it is the Sabbath. They use as target practise some female pornographic images that one of them has drawn on the white-washed wall. This wall

reveals a real “miracle” to them when, after a rifle shot loosens the lime, in the reddish glow of the evening sun, the “blessed, sweet face of the Mother of God” appears behind the spot where the indecent images had stood. This miraculous apparition sets off a chain of events: Soldiers and peasants hurry to the scene, fall on their knees, sing Marian hymns, hit their foreheads against the ground, fall into rapture, eagerly seek to repent and settle their debts and work themselves up into a frenzy of hatred that ends in a pogrom against the Jews that same night: “It was as if the peasants had not only seen the miraculous appearance [of the image of Mary] with their own eyes, but also as if they could remember the individual shameful acts by which the Jew had defiled the image and covered it with blue lime”. Fifteen years after the night of horror, the place where the event took place has become a chapel that the innkeeper, a Jew, had someone make out of the barn. The memory of the horror, however, fades “before the holiness of the image” from whose face forgiveness flows for the repentant. Where there is an image of God, there is the Godhead. For a long time, it had been hidden behind a blue-washed wall. Now, however, when the event of revelation together with its violence fades, “on Sunday the holy mass” is read here, in the tavern and village there is much to do because of the pilgrims, as the Christian servant reports, and so “we earn more than on the days when there is a pig market”.32

In 1879, Max Liebermann painted a large- scale picture depicting the twelve-year- old Jesus in the Jerusalem Temple (fig. 3). The setting is a modern synagogue in Western Europe, probably in Hamburg, with candlestick, reading desk and benches, the interior modeled on the style of contemporary 19th century historicism, the boy Jesus painted without the aura of the sacred. Twenty-five years earlier, the highly respected Adolph von Menzel had already painted a Christ Child in the Temple, which, in contrast to the pious painting style of the Nazarenes, was oriented toward the biblical figures painted by Rembrandt. First and foremost, he shifted the pictorial action to the ambience of Oriental Judaism. Menzel, the master of Realism, often painted sections of the picture that seem random, but were carefully arranged. If Menzel’s picture stood, as it were, in contextual correspondence to a study in the Life of Jesus, Liebermann’s Jesus appeared in the wake of bourgeois Realism as a boy asking for knowledge. Both pictures convey the impression of wanting to be enlightened about the conditions in human history. This also gave Liebermann the impetus to formulate his understanding of the Jewish. Like Menzel, he refrained from depicting Jesus with the glory of the holy. His Jesus lacks the auratic appearance; the only concession to the German audience was Jesus’ long, blond hair. It was precisely the absence of the visually auratic, however, that outraged conservatives who were upset with both artists and their paintings. Both provoked reactions that could be described as scandalous and were perceived as just that at the time.

The fierce public criticism reveals the gap between church and art, which the Nazarenes seemed to have bridged in the spirit of Romanticism when they transformed their art into faith. In the run- up to the 20th century, German Protestants disputed the “Christ ideal in German

c rooked t imbers

art” in an often polemically conducted debate, as the title of an exhibition shown in Berlin in 1896 may state it.33 The question was raised whether commercial art would not drag down high art or how sensibilities could be raised by appropriate representations of Christ in the vein of philosophical idealism. Finally, the debate also touched on the modern, i. e. historical Jesus.

Menzel’s and Liebermann’s early paintings, which sparked off these disputes, must be seen in the context of the entire Wilhelmine period, which also included the rise of anti-Semitic asso -

ciations since 1870. The public scandalization of Liebermann was not exclusively bound up with criticism of his stylistic means, but also with the accusation of blasphemy.34 Public scorn and indignation turned these two cases into a “Jesus-Scandal” in the then- contemporary discussion of art. As if there had not been the first impulse of a David Friedrich Strauss, inspired by Hegel, to distinguish the historical Jesus from the Christ of faith. This thought, however, had already been initiated in the 18th century by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in a distinction brought up by Hermann Samuel Reimarus, when he drew the dividing line between the “religion of Christ” and the “Christian religion”. Jesus, thus set free from Christology, is regarded by both thinkers as a universal example of the religion of reason, which paves the way to the education of the human community.35

Liebermann’s painting, which presented Jesus as a youthful Jew, can be read as targeting the ignorance of the Christian majority society towards historical facts and as a criticism of the ignorance of Jewish communities towards the figure of the historical Jesus and the Acts of the Apostles. While both stances deserve attention, they have often enough been ignored against better judgement. After all, rabbis and historians in Germany since the middle of the 19th century situated the historical Jesus in one of the many currents within ancient Judaism, and these interpretations of the Jesus biography continued into the 20th century in different regions in striking contributions.36 They were not the first voices on European soil; rabbis and poets had already commented on the role of Jesus and Muhammad in the Middle Ages.37

In the 19 th century, Jesus was biographically understood as part of the Judaism of his time. He appears in it as a reformer of the Pharisaic and proto- Rabbinic movement or as a sharp critic of this movement, which he denounces as usurping the universal spirit of Hebrew prophecy in order to defend Mosaic Judaism he has come to fulfill his commandments, and he calls his listeners to understand themselves as faithful servants of God from Sinai. Alternatively, he is seen as a rabbi, as a teacher, either with or without some inclination toward imminent apocalyptic expectations or as a sympathizer of the Essene movement. It is also clear that Jesus was stripped of his various Greek- Hellenistic garments, which served to make him acceptable in the context of Roman reception. In another vein, the Hellenistic influence, which produced its own Hebrew wisdom literature before and at the time of Jesus and is indebted to the Jewish diaspora, is also emphasized as the universal horizon of his sermons. Still others recognize in Jesus a rather conservative Jewish preacher who addressed the marginalized with compassion and sought to integrate this socially ostracized stratum into the center of the Jewish community.

On the other hand, confrontational paths of Jewish debate have been taken which no longer base their argument exclusively on the historical-biographical. In this case, the dogmatic and ritual content was brought into focus and certain definitions were tackled with regard to pre- existence, incarnation, understanding of sacrifice, resurrection and messianism, which exist not only between but also within Judaism and Christianity. It is striking that there is a certain parallel between Jewish and Christian efforts to locate in the present the “essence” of the belief

c rooked t imbers

4 E. M. Lilien: Illustration for the book of Johann von Wildenrath’s novel Der Zöllner von Klausen (The tax collector), 1898, 9 × 12 cm; Zentralbibliothek, Zürich.

systems of both religions as dialectically interpreted truth by means of an actualizing theology of the new.38 It is therefore the faithfulness, the commandment and the comfort with which Jesus addressed the oppressed, the suffering and the aberrant within his Jewish community, as in 1938 Leo Baeck notes; in contrast, this is no longer decisive for Paul later- on, but the sacrament in the name of Jesus, his death and resurrection, with which a messianic doctrine of redemption is brought into the world and the apocalyptic excitement is contained and that is precisely why “the image here is more than the sentence, the visually seen more than the faithfully recognized.”39 In North America and the United Kingdom, important rabbis took an open stance on Jesus and Christianity in the later 20th century, such as Abraham Yehoshua Heschel, Joseph Ber Soloveitchik, Michael Wyschogrod, Jonathan Sacks and Irving Greenberg. And finally, in 2015, in the context of the Shoah remembrance, a group of Orthodox rabbis under the lead of Shlomo Riskin published a “Declaration on Christianity” that once again points in another direction, warmly welcoming Jesus for majestically bringing a double goodness to the world: “He strengthened the Torah” and “removed the idols from the nations”.40 The statement of the Orthodox rabbis in 2015 is remarkable for us here in that it credits Jesus with having brought the second commandment, which forbids the worship of idols and the adoration of images and sculptures, into the world and among the nations. We will deal with this in detail later. In summary, the time when Liebermann’s empathetic painting could still cause outrage in the majority Christian society is long gone. Rather, it now proves to be a historical document that, like many other things, also bears witness to the social and theological needs of the respec-

tive epochs. Jewish intellectuals and artists expressed and continue to express their thoughts thanks to that freedom that has been reached, yet remains unsecured and ambivalent, which Isaiah Berlin figuratively described as the “crooked timber of humanity” after a phrase by Immanuel Kant.41

Art of Jewish provenance has by no means remained untouched by these questions and disputes over interpretation. From the turn of the 20th century and beyond, it has increasingly

c rooked t imbers

6

dealt with motifs from the New Testament. Maurycy Gottlieb’s paintings from the 1870s show Jesus before his judges or as a preacher in Capernaum on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement a rabbi in front of his Jewish audience, among whom is also a Roman. Jewish depictions of Jesus in the history of art in modern times has continued to this day, at times rather restrained and

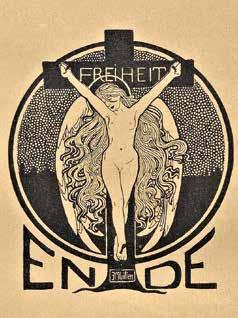

not to a great extent, at other times obsessive and striking in its interpretations, as Amitai Mendelsohn has shown.42 This is no less true of depicted crucifixions that refer to the Jews’ own suffering and fate or are related to the Shoah (fig. 95) or are used as a Zionist metaphor (fig. 97) or are intended as a provocation against all religious and political conventions. The illustration by Ephraim Moses Lilien from 1898, created at a time when the debate on the exhibition was raging in Berlin and barely twenty years after Liebermann painted his empathic young Jesus, would probably have been perceived as incomparably more scandalous: the figure of a sensual woman with wild hair nailed to the cross announcing the anarchic potential of the oppressed and rebellious in the early modern period (fig. 4). Not to mention an installation from 1982, coming more than a hundred years after Liebermann’s painting, when the Israeli artist Igael Tumarkin, born Peter Hellberg in Germany in 1933, exhibited his Bedouin Crucifixion at the Israel Museum (fig. 5). The ancient Christian symbol cited in the title, visually recognizable as a cross, becomes a useful tent pole in the everyday lives of the desert nomads who depend on these crooked timbers for their dwellings. The simple wooden stake and the reinterpretation of the cross as a nomadic tool inevitably elicits empathy with their way of existence, without abandoning the ambivalence of religious cult images. And likewise, Michael Sgan- Cohen, under the evocative title Leaning Crucifixion, thematized the wooden stake on which he nailed one of his self-portraits as if it were the inscription, familiar from so many paintings, of the crucified Jesus as King of the Jews but verily this stake remained empty.43 Instead of a sacrifice on the cross there is a small seized self-portrait, instead of a corporeal man only the image of a human face (fig. 6).

Among moderns in Europe, such as Max Frisch, the image and prohibition of images is closely linked to the idea of the “Jewish,” but in a contrary perspective compared, for example, to Joseph Roth: the internal as well as external image now makes every person a potential “Jew.” This is understood by Frisch as the deeper cause of the guilt of German culture for the Holocaust. The desire to escape the image as a false cult, which in Joseph Roth provides the trigger for the pogrom against the Jews, has for the moderns mutated into a high ideal. That a false attribution of the Jewish could adhere to the true universality has to be avoided. In his drama Andorra, Frisch identifies the fate by which the figure of the social outsider Andri is designated a “Jew” among the Andorrans as the culpable manufacture of an image. This process brings people to the “stake”. In the transition from the seventh to the eighth image, Frisch has a speaker who appears as “Pater” proclaim: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image of the Lord God, nor of mankind, which are his creatures.”44 The violation of the prohibition of images appears as the deeper reason for the death sentence at the stake carried out on Andri, who has been turned into an outsider.

But how can this be staged? It was only during the Zurich stage rehearsals, directed by Kurt Hirschfeld, that Frisch pronounced his illusion as a writer, that justification and narration would have to take place simultaneously, as a categorical trap. To criticize the production of

c rooked t imbers

images and at the same time to end up displaying such an image on stage would only have been to produce a new image of horror. It was precisely this, the bodily representation of violence on stage, that seemed sacrosanct to the Jewish director of the Schauspielhaus. Ancient Greek theater had once limited the depiction of acts of violence to language, to the imagination, from which an image could only emerge from the inside. In any case, Hirschfeld talked Frisch out of showing the execution visually on stage. To him it appeared as “false metaphysics, as metaphysical nonsense”; the theater should be “forum, not pulpit”, which has only one truth, its truth.45 And so, instead, Hirschfeld’s Schauspielhaus presented only the empty stake in anticipation of the condemned man as a symbol of the culpability of society, or of history. Whether the empty stake was perhaps seen by some spectators as a secular substitute for the cross is not known. It is a fusion of wood and carving, a transitional figure from the living tree and the as yet uncarved sculpture, both sacred objects in terms of religious history, which have certainly been suspected of being idols.46 For Frisch, in any case, the empty stake as a symbol denotes the scandal of the broken prohibition of images, which for him makes “Jews” out of people. It stands, as it were, in reverse thrust to Joseph Roth’s scathing depiction of repressed guilt. The interpretation in which Frisch thematized the question of guilt after the Holocaust ultimately presupposes a conception of Judaism that is deeply hostile to images. Yet Frisch, who always questioned himself and his texts, meant it sincerely. The human being, whom we love and therefore cannot describe, cannot be grasped in the image, as he formulated his claim to himself in his Tagebuch mit Marion. It could not be sustained even by him, as he openly says: love is free from any image, but if one were to make oneself an image, it would be “loveless, a betrayal”.47

The fifteenth Documenta in Kassel in 2022, a highlight of the German and international cultural scene, was dominated by “non-Western” art from Asia, Africa, the Near and Middle East, and the Caribbean, by some 1500 artists. The monumental banner painting by the Indonesian artist collective Taring Padi featured, among many figures, an Orthodox Jew with SS runes and a pigfaced soldier with his helmet marked “Mossad.” The banner, a colorful wordless picture book, bore the title “People’s Justice”, which is rendered in German by AI translation machines as the loaded “Volksjustiz” from Nazi history. The German curators found themselves heavily criticized. Unwilled associations with Nazi courts and their arbitrary justice were evoked. Accusations of anti-Semitism were followed by expressions of regret on the part of those responsible who acknowledged that the depictions might unintentionally lend themselves to “anti-Semitic interpretations.” The large-format picture book dealing with the horror of human violence was first covered up and then dismantled at the behest of the authorities (fig. 7).

The concern of the global South to be able to present artistic diversity was lost in this expression of public outrage. The damage is probably permanent. The Indonesian artists, in turn, apologized, but felt drawn into a German discourse that was not factually identical to the Indonesian context in which the painting had been created during the Suharto dictatorship more

7 Covering of the banner image of the Indonesian artist collective Taring Padi, Kassel June 20, 2022.

than twenty years earlier. The statement of the artists’ collective was remarkably cogent: they had known what was painted on the picture book, but they had seen the picture so often in the two preceding decades that they could no longer see what it actually showed. 48 Revealing and concealing intertwined in this self-knowledge: One of many truths appeared in the cloth picture book, but precisely for that reason there was and is no image of truth.

With a tense perspective on the different now and in the past, and in an effort to dismantle colonialist and National Socialist guilt, Germany had maneuvered itself into a state of cultural emergency. The scandal that was thus unveiled and that the Documenta organizers shouldered with the hasty covering up of the picture boiled down to the fact that Israeli artists, namely Jewish Israelis, had not been invited to the 2022 Documenta. They remained excluded from what is called the “global south” although many of the todays Israeli artists are descended of families from Arab, Asian and African countries. In terms of the politics of remembrance, this was bound up, whether intentionally or not, with the historical beginnings of Documenta in the postwar period and its central intention of bringing so - called “Degenerate Art”, outlawed during the National Socialist era, to the attention of the German public. By 1955, however, with one prominent exception Marc Chagall and his allegedly “nostalgic” images of a world that had “perished” no Jewish artists had been exhibited at all; this changed in the 1960s hesitantly only. In this perspective, the historical claim of Documenta contrasted with the global exclusion of anything Jewish in 2022, which can be read as a demonization of Israel.49 A culture that was

imbers

said to be fundamentally “hostile to images” was being denied a platform, since Jews seemed incapable of producing art anyway. The fact that almost half of the 21 Documenta founders had once been Nazi party members themselves, makes the Documenta almost seven decades later look like an unintentional stage for a politics of remembrance that implicitly suffers from handed- down stereotypes of a Judaism devoid of images and art.50 The covering up of the banner image represented an outcry by the German public that had seen with its own eyes that Jewish ie Israeli artists had been suppressed for decades, as if their works heralded a new iconoclasm that pertained to these very works, and only these works, and to their artists.51

The German outcry is no mere catechesis; rather, it is to be taken seriously. It makes the political state of mind of the Federal Republic discursively audible in its legitimate desire to interpret the constitutional dignity of man. The turning point for this development, May 8th 1945, had once been perceived by Theodor Heuss in soteriological terms as the German nation’s “most tragic and questionable paradox of history” because “we have been redeemed and annihilated in one”.52 The process sketched on our canvas often hastily quoted along with generalizing, less meaningful terms such as “anti-Semitism” or “racism” or “postcolonialism”53 is intertwined in the German context with the history of the Holocaust and the will to confront this history. It is, moreover and far more generally, an object lesson in how art is interpreted in religious or ideological terms.

To transform art under the sign of political theology is quickly overshadowed by apologetics and bans on images. In addition, it is a bitter irony that the Indonesian artists found themselves exposed to a colonizing appropriation by Western postcolonialism and must now draw lessons from this in their relationship to Jews and Israel. There would be ample reason for both Israelis and Indonesians to maintain a shrewd skepticism towards their respective holders of power through art. But whether an initiative will develop so that artists from both sides can meet to exchange ideas and thus work out a common future is anyone’s guess.

Aaron (bibl. high priest) 48, 88, 101–103, 119, 132, 274

Abraham (bibl. archetype) 101, 115, 118, 126, 153, 211, 316, 427

Abraham Ibn Esra, Rabbi 235

Adam (bibl. archetype) 80, 116, 201, 223, 227

Adler, Cyrus 237

Adorno, Theodor 12, 109, 164–168, 174, 185, 293 f., 325, 351, 359, 373

Ajchenrad, Lajser 258, 326, 335

Alberti, Leon Battista 272

Al-Hawajri, Mohammed 36

Alloa, Emmanuel 174

Amos (bibl. prophet) 365, 382

Anderson, Benedict 286

Antokolsky, Mark 300

Aphrodite (greek goddess) 99–101, 205

Arendt, Hannah 196, 207, 258, 288

Aretino, Pietro 210

Ariel, Yaakov 139

Ariès, Philippe 241

Aristotle 40, 141, 356

Ashkenazi, Zvi 104

Ashlag, Yeguda 346

Ashton, Dore 95

Assmann, Jan 118, 353, 364

Augustine of Hippo 223 f., 241, 277, 367

Avissar, Miriam 82

Azaryahu, Maoz 296, 383

Bach, Johann Sebastian 203

Bachmann, Ingeborg 340

Baeck, Leo 26, 68, 339, 357

Baermann Steiner, Franz 319

Baigell, Matthiew 95

Bak, Samuel 300, 313–315, 320–322, 331

Baldung Grien, Hans 129

Balzac, Honoré de 164 Bamberger, Fritz 67

Banksy (artist) 36, 180

Bar-Am, Micha 170–172

Bardot, Brigitte 170

Baron, Salo 225 Barth, Karl 153, 220, 225, 339

Baudelaire, Charles 164 f., 254

Bauer, Yehuda 291

Baumel-Schwartz, Judy Tydor 310 Baumgarten, Alexander Gottlieb 191 Beard, Mary 13, 373

Beatles (music group) 170

Becker, Howard S. 129 Beckett, Samuel 41

Beckmann, Max 143, 216–218

Beethoven, Ludwig van 253

Bellah, Robert 137

Bellini, Giovanni 219–221, 366 Belting, Hans 109, 351

Benedict XVI (pope), see: Ratzinger, Josef Benjamin, Walter 17, 36, 89, 109, 164–168, 174, 205, 255, 289, 325, 330, 351, 383

Berdichesvsky, Micha Yosef 39

Berenson, Bernhard 344

Berlin, Isaiah 27

Bezalel (bibl. archetype) 77, 84–86

Biale, David 347

Biemann, Asher 52

Binswanger, Ludwig 276

Bland, Kalman 56

Bloch, René 345

Blösche, Joseph 332

Blumenberg, Hans 175, 340

Boas, Franz 142, 208, 273, 276, 375

Böckenförde, Ernst Wolfgang 225

Bol, Ferdinand 163

Boll, Franz 231

Boltanski, Christian 293

Bondy, Walter 21 f.

Born, Friedrich 381

Bosch, Hieronymus 215

Botticelli, Sandro 272, 343

Bourne, Randolphe 273, 373

Braginsky, René 65 f.

Brahms, Johannes 216, 357

Brandeis, Louis 373

Brandes, Georg 15, 338

Bredekamp, Horst 163

Breuer, Marc 227, 367

Brod, Max 15, 164

Brodsky, Joseph 126

Brunner, Emil 216, 366, 339

Bruskin, Grisha 106 f., 167 f.

Buber, Martin 56–58, 75, 192, 252, 302, 339, 362

Buchholz, René 166

Buddha, Gautama 177, 206

Budko, Joseph 213

Bultmann, Rudolf 220

Buonarotti, Michelangelo 47–53, 94, 210, 243, 255 f., 259, 273, 343, 357

Burckhardt, Jakob 45, 254

Burke, Edmund 191

Butler, Judith 141

Butor, Michael 95

Calvin, Jean 42, 230 f., 368

Caminada, Christian 122, 276

Campbell, Joseph 150, 208

Canetti, Elias 354

Carafa, Carlo 210

Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da 161

Cassirer, Bruno 273

Cassirer, Ernst 16, 33, 94, 109, 133, 167, 196, 274, 276, 375

Castel, Moshe 302

Celan, Paul 325–327, 383

Cervantes, Miguel de 304

Chagall, Bella 372

Chagall, Marc 21, 31, 48, 58 f., 90, 134, 250, 298, 300, 302, 329, 338, 346, 372

Chamberlain, Houston 152 f., 358

Charlemagne (emperor) 127

Churchill, Winston 258, 307, 380

Clairvaux, Bernard von 122, 353

Cleopatra (pharaoh, movie character) 159

Coen, Ethan 158–160

Coen, Joel 158–160

Cohen, Hermann 50 f., 56, 127, 139, 141, 344

Cohen, Leonhard 168, 384

Cohen, Richard I. 104

Cohn-Wiener, Ernst 60

Comenius, Johann Amos 131, 176

Comte, Auguste 40

Connerton, Paul 306

Constantine, Flavius Valerius (roman emperor) 115–117, 120, 124, 191

Coppola, Francis Ford 204 Cranach, Lukas 132, 159

Da Vinci, Leonardo 247, 371

Daniel (bibl. prophet) 196, 261 Dante Alighieri 241, 258 f., 349

David (bibl. king) 47, 102, 313, 315

Dayksel, Shmuel 272, 375

Deborah (bibl. prophetess) 47

Delauney, Sonja 21

Democritus (philosopher) 116

Demsky, Noam 312, 381

Dewey, John 373

Diderot, Denis 228, 236

Dilthey, Wilhelm 196

Diner, Dan 154, 379

Dostoevsky, Fjodor Mikhailovich 125 f., 149

Dreier, Horst 225

Droysen, Johann Gustav 45, 47

Du Bois W.E.B. 373

Dubnow, Simon 288

Dürer, Albrecht 216, 232

During, Fritz 172

Durkheim, Emil 200

Dürrenmatt, Friedrich 40, 221, 247, 251, 255–258, 261, 291, 367, 377

Eckart, Dieter 152, 358 Eco, Umberto 161

Eger, Akiva 195, 109

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Irenäus 202

Eichmann, Adolf 225, 333

Elazar ben Samuel, Rabbi 107

Electra (greek narrative character) 48

Emden, Jacob 104

Enelow, Hyman 356

Epicurus (philosopher) 116, 296

Epstein, Marc Michael 64

Erasmus of Rotterdam 104

Erne, Thomas 129

Eve (bibl. archetype) 80, 116, 201, 223 f., 227

Eyck, Jan van 210

Ezechiel (bibl. prophet) 37, 63, 77, 214, 315

Ezra (bibl. priest) 227

Fackenheim, Emil 298

Farber, Eldar 309, 381

Farbstein, David 141

Faulkner, William 233, 368

Feller, Harald 381

Fenster, Hersh 21, 339

Feuerbach, Ludwig 110, 145

Fichte, Johann Gottlieb 90

Fiore, Joachim of 56, 344

Fischer, Eugen 37, 153

Flavius Josephus 64, 104, 122, 350

Flusser, Vilém 161

Fortis, Biniamino 346

Francesca, Piera della 220

Frank, Anne 305, 383

Fredericks, Oswald and Naomi, see: Kucha Hónawuh

Freud, Sigmund 42 f., 50 f., 86, 118, 152, 214, 247, 261–264, 273, 363, 373

Friedländer, Saul 152, 255, 379

Friedman, Benjamin M. 230

Frisch, Max 29 f., 34, 36, 302, 340

Fromm, Erich 13

Fuchs, Eduard 34, 36

Gäbler, Ulrich 136

Gamliel, see: Rabban Gamliel

Gasparri, Pietro 279

Gasparro, Giovanni 36, 341

Gebhard, Rudolf 135

Gehring, Ulrike 96, 328, 371

Geiger, Abraham 44, 139, 142, 339

Géricault, Théodor 238, 369

Gesundheit, Shoshana 312, 381

Getter, Tamar 222

Gideon (bibl. army commander) 47

Ginzberg, Louis 88, 347

Girard, René 10, 34, 340

Gladstone, William 307

Gobineau, Arthur de 152 f.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von 15, 41

Gogol, Nikolai 179

Goldschmidt, Hermann Levin 294

Goldy, Robert 139

Goltzing, Hendrick 163

Gombrich, Ernst 254

Goodenough, Erwin 59 f.

Goschler, Constantin 306

Gossaert, Jan 128

Gotthelf, Jeremias 134, 208

Göttler, Christine 127

Gottlieb Adolph 300

Gottlieb, Maurycy 28

Graetz, Heinrich 56, 75, 339

Grant, Madison 153

Greenberg, Irving 26, 228

Gregory the Great (pope) 112, 242

Grimm, Herman 47 f., 51, 256, 357

Gross, Raphael 225

Grotius, Hugo 369

Grunder, Hans-Ulrich 176

Grundmann, Walter 154, 358

Grunewald, Max 344

Grünewald, Matthias 220 f.

Grüninger, Paul 310 f., 360, 381

Guggenheim, Alis 21, 140

Guggenheim, Paul 287

Gustafsson, Carl 186–188

Guttmann, Julius 56

Haddad, Elie 82

Hadrian (roman emperor) 65, 85, 101 Haendel, Gerorge Frideric 116

Haering, Barbara 236, 369

Haftmann, Werner 95, 349

Hakl Bakl (puppet theatre) 249–251

Halbwachs, Maurice 295

Hallo, Rudolf 60

Hanina ben Dosa, Rabbi 112

Hara, Kenya 93 f.

Harari Navon, Neta 93 f., 247, 255. 259–261, 263, 267

Harnack, Adolf von 135, 339

Hasaas, Olaf 222

Heer, Friedrich 358

i ndex of n ames

Hegel, Georg Fridrich Wilhelm 23, 36 f., 39–53, 55 f., 68, 72, 80, 91, 130, 134, 142, 146, 158, 166, 193–196, 208, 225, 254, 294, 345

Heidegger, Martin 196, 207

Heimann-Jelinek, Felicitas 71

Heine, Heinrich 56, 60, 86, 145, 196, 204, 252, 348

Heller, Vera 312

Heraclitus of Ephesus 214

Heschel, Abraham Joshua 25, 80

Heschel, Susannah 154

Hess, Moses 53

Heuss, Theodor 32

Hezekiah (bibl. king) 19, 274–276

Hieronymus (church father), see: Jerome

Hildesheimer, Wolfgang 41

Hirsch, Emil 356

Hirsch, Samson Raphael 227

Hirsch, Samuel 104 f.

Hirschfeld, Kurt 30

Hirszenberg, Samuel 51 f.

Hitchkok, Alfred 159

Hitler, Adolf 152–154, 157, 168, 205, 225, 258, 291, 298, 318, 326, 342, 358

Hobbes, Thomas 207, 253 f., 318

Hofmannsthal, Hugo von 161

Holbach, Paul Henry Thiry de 236

Holmes, Oliver Wendell 373

Holzer, Anton 180

Homer (greek epic, poet) 101

Honi HaMe’agel (the circle-drawer) 112

Horkheimer, Max 12, 141, 166, 291, 304, 360

Horvath, Ödön von 161

Hosea (bibl. prophet) 110, 160

Hugo, Victor 243

Humboldt, Wilhelm von 141

Hyrcan (hebrew high priest) 104

Ibn al-Chattab, Umar 69

Idel, Moshe 346

Isaac (bibl. archetype) 81 f., 115, 126

Isaac, Abraham 356

Isaiah (bibl. prophet) 77, 92, 125, 274, 305, 335, 384

Jabès, Edmond 326 f.

Jacob (bibl. archetype) 47, 64, 75, 95, 115, 335, 343, 346

Jakob ben Reuben, Rabbi 78

James, William 246, 276, 373

Jastrow, Morris 356

Jehuda, see: Yehuda

Jeremiah (bibl. prophet) 100

Jerome (church father) 223

Jesus (Christ) 13 f., 23–29, 37, 39, 43, 52, 54, 74, 86, 91, 94, 111 f., 115 f., 118, 120 f., 124 f., 130, 134–137, 145–154, 158, 178, 193, 210 f., 227, 248, 265, 274, 302, 338 f., 341, 352, 366, 371

Joas, Hans 41

Job (bibl. archetype) 139, 203, 220, 249–252, 261, 299, 334, 367

Jochanan ben Nappacha, Rabbi 64

Jochanan ben Zakai, Rabbi 86

Jochum, Herbert 44

John (apostle) 53, 115, 201, 216, 274, 276

John of Antioch 116

John of Damascus 120

John the Baptist 213, 216

Jonas, Hans 40

Joshua (bibl. leader) 40

Joshua ben Hanania, Rabbi 101

Josiah (bibl. king) 132 f.

Judas Iscariot (bibl. archetype) 36, 150, 184, 265

Julian (roman emperor) 115

Jung, Carl Gustav 277

Kafka, Franz 41, 207, 210, 299

Kallen, Horace 273, 373

Kandinsky, Wassily 216

Kant, Immanuel 26, 51, 53, 55, 72 f., 80, 122, 130, 141, 146, 166, 191, 228, 236, 239, 246, 263, 274, 328, 356

Kaplan, Mordechai 138, 273, 339

Katz, Eliezer Susman ben Salomon 87

Katz, Jakob 107

Keel, Othmar 69

Keller, Augustin 143, 353 Keller, Erich 288

Keller, Gottfried 286

Keller, Stefan 310

Kelsen, Hans 342

Kermani, Navid 366

Kershaw, Ian 258

Khomeini, Ruhollah Musavi (ajatollah) 176

Kikoïne, Michel 21

Kilcher, Andreas 347

Kim Phúc, Phan Thi 180–184

Klee, Paul 168, 255, 258

Klüger, Ruth 293

Knightley, Phillip 180

Kogman-Appel, Katrin 78

Kohler, Kaufmann 67, 139, 356

Koselleck, Reinhart 143, 291

Kraus, Karl 258

Krauss, Salomon 344

Krautheimer, Richard 60

Kriß, Rudolf 122

Krüger, Malte Dominik 130

Kucha Hónawuh, Naomi Fredericks 269

Kucha Hónawuh, Oswald Fredericks 269

Kuhn-Loeb Bank 375

Kuisz, Jarosław 119

Laderman, Shulamit 117

Landsberger, Franz 60

Lanzmann, Claude 293–295

Laqueur, Thomas 286

Las Casas, Bartolomé de 369

Latour, Bruno 185

Lavater, Johann Caspar 189–192

Lazarus (bibl.) 222

Lazarus, Moritz 141–143

Le Goff, Jacques 241, 370

Lehmann, Julius Friedrich 153

Leibowitz, Yeshayahu 89

Lenin, Vladimir Iljitsch 168, 170, 186

Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim 25, 132, 152, 187, 189–192, 356, 362

Levi, Jehuda, see: Yehuda ha-Levi

Levi, Paolo 341

Levi, Primo 305

Lévinas, Emmanuel 291, 298, 305, 327

Levy, Daniel 306

Levy, Rudolf 21

Lévy-Bruhl, Lucien 199

Leyden, Lucas van 210, 216

Libeskind, Daniel 335

Lichtheim, Sarah 249

Liebermann, Max 23–25, 33, 36, 39, 114, 127, 134, 249

Lilien, Ephraim Moses 26, 29, 48, 57

Lipchitz, Jacques 21

Lipton, Sara 36

Lissitzky, Eliezer 83, 347

Locke, Alain LeRoy 89

Locke, John 240

Loeb, Nina 273

Lucas, George 150

Lucretius (philosopher) 116, 200, 240

Lukaschenko, Alexander 174

Luke (apostle, gospel) 116, 128, 147, 276, 352

Luria, Isaak Rabbi 75

Lurie, Bories 329 f., 383

Luther, Martin 42, 129, 132 f., 143, 224

Lüthy, Herbert 45

Lyotard, François 91–94, 97, 99

Maccabees (makkabbīm, Jewish rebel group; books) 73, 104, 122, 214

Magritte, René 157, 185

Maimonides, see: Moshe ben Maimon

Malachi (bibl. prophet) 81 f., 365

Mané-Katz, Emmanuel 21, 151, 300

Manieri, Anthony Patrick 172

Mann, Barbara 53

Mann, Thomas 261

Manuel, Niklaus von 131–133

Mao Tse Tung 184 f., 187

Marc, Franz 123, 216, 218

Marcuse, Herbert 158 f., 167

Mark (apostle, gospel) 147, 160, 217, 221, 276, 352, 366

Martin, John 204

Marx, Karl 132, 136, 145, 158, 163, 168, 185, 194, 240, 246, 354 f.

Matthew (apostle, gospel) 37, 341, 352

Mauss, Marcel 122, 199, 231, 353

McCarthy, Joseph 159

Mear One (Kalen Ockerman) 36, 341

Mei, Ru’ao 380

Meijer, Cormelis 237, 239 f.

Meir Simcha ha-Kohen, Rabbi 89, 349

Meir von Rothenburg, Rabbi 78

Memmling, Hans 210

Menachem Mendel Zaks, Rabbi 349

Mendelsohn, Amitai 29, 304, 373

Mendelssohn, Moses 10, 33, 40, 73, 127, 132, 137, 139, 141, 189, 191–196, 228, 356, 362

Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Felix 145 f.

Menzel, Adolph von 23 f., 33, 134

Messiaen, Olivier 366

Meyerbeer, Giacomo 145 f.

Michelangelo, siehe: Buonarotti, Michelangelo

Michelet, Jules 287

Milano, Attilo 53

Miller, Lee 205 f.

i ndex of n ames

Miriam (bibl. archetype) 48

Modi, Narendra 172

Modigliani, Amedeo 21

Momigliano, Arnaldo 279

Mommsen, Theodor 47

Mondzain, Marie-José 112, 158

Montagine, Michel de 42 f., 240 f., 279, 362

Moses (bibl. leader) 36, 47–54, 84 f., 89, 101–103, 113, 118 f., 132 f., 163, 189–196, 214, 262, 273–276, 302 f., 313, 317, 343, 346, 348, 351, 359, 363, 365, 375

Moses Sofer, Rabbi 103 f., 107

Moses von Coucy, Rabbi 78

Moshe ben Maimon (Maimonides) 78, 141, 339, 356

Mosse, George 272

Motherwell, Robert 47, 54

Mougenot, Frédéric 308

Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus 216

Muhammad (arabic prophet) 25, 68–70, 177 f., 339, 366

Mumford, Lewis 273

Munch, Edward 118 f.

Mundkur, Balaji 202, 277

Münkler, Herfried 150

Mussolini, Benito 279

Nancy, Jean Luc 202

Natan, Efrat 301 f.

Navenad (theatre group) 249

Neumann, Erich 199, 277

Newman, Barnett 91, 95, 99, 300

Newton, Isaac 239 f.

Nicolai, Friedrich 189

Nietzsche, Friedrich 15, 33, 37, 39, 47, 57, 118, 145–150, 164 f., 175, 188, 196, 199, 223, 243, 272, 277, 287, 326, 341, 346

Nightwish (Metal Rock Band) 372

Nilsson, Mikael 358

Nordau, Max 37, 39

Nossig, Alfred 57 f., 73

Odysseus (greek archetype) 48

Oedipus (greek archetype) 48

Onias (bibl. high priest) 122

Oppenheim, Daniel Moritz 49–53, 189 f., 192, 343

Origines (church Father) 117

Orley, Barend van 210

Ortega y Gasset, José 40, 363

Otto, Rudolf 201

Ouaknin, Marc-Alain 71, 349

Overbeck, Franz 43

Ozick, Cynthia 61, 305

Panini, Giovanni Paolo 147–149, 154

Pascal, Blaise 207

Pascin, Jules 21

Paty, Samuel 177

Paul (apostle) 26, 45, 86, 115, 117, 122, 141, 147–149, 185, 193, 220, 227, 274, 276, 350, 352, 367

Paul, Gerhard 181

Pelagius (theologue) 223, 367

Peretz, Isaac Leib 242, 251

Perugino, Pietro 343

Peter (apostle) 208

Petronius, Titus Arbiter 200

Pharaoh (egypt. god king; movie character) 51, 58, 114, 274, 343

Philo of Alexandria 74, 85 Picard, Henri 123, 354

Picard, Max 203

Picasso, Pablo 265–267, 280

Pincus-Witten, Robert 91

Plato (philosopher) 17, 80, 113, 164, 188, 206, 262 f., 356

Plummer, John 181–184

Pollack, Martin 286

Pompeius, Gnaeus Magnus 111

Postman, Neil 186 f.

Potok, Chaim 90

Proclus (philosopher, narrative character) 80, 99 f., 350

Prodolliet, Ernest 381

Proust, Marcel 17, 41 Provoost, Jan 215 Purja, Nirmal 173 Qin Shinhuangdi 184 f.

Rabban Gamliel 80, 97, 99–101, 350

Rabinowicz, Fishel 323, 327

Radbruch, Gustav 289, 377

Ragaz, Leonhard 136, 141, 143, 356

Ramuz, C. F. (Charles Ferdinand) 255

Raschi, see: Shlomo ben Yizhak Ratzinger, Josef (Benedict XVI) 43, 153, 342, 369

Rauterberg, Hanno 163

Rawls, John 216, 244, 366

Reich, Léon 285 f., 333

Reich, Ruth 286

Reich, Steve 321

Reichmann, Eva 312

Reimarus, Hermann Samuel 25

Rembrandt: siehe Van Rijn

Revere, Giuseppe 53

Ricœur, Paul 95, 306

Ris, Abraham 103 f.

Riskin, Shlomo 26

Roeck, Bernd 129

Rokeah, David 326 f.

Rosen, Aaron 95

Rosenzweig, Franz 192, 252, 326, 372, 379

Roskies, David 326

Roth, Cecil 60

Roth, Joseph 22 f., 29, 33 f., 36, 60, 333

Rothko, Mark 61, 91, 95–98, 99, 113, 300, 328, 383

Rubens, Peter Paul 50, 216, 259, 300

Rubin, Reuven 346

Ryback, Issachar Ber 82 f., 347

Sachs, Nelly 326

Sacks, Jonathan 26

Safdie, Moshe 322

Safranski, Rüdiger 41

Salamo, see: Shlomo, Solomon

Samson (bibl. hero) 47

Samuel, Pascale 339

Sandler, Irving 91

Schäfer, Peter 227

Schama, Simon 163

Schapiro, Meyer 344 f.

Scheiner, David 372

Schiff, Jacob 375

Schiller, Friedrich von 167, 187, 228, 253, 328

Schlegel, Friedrich 15

Schlote, Olaf 292, 381

Schmidt, Mattias 146

Schmitt, Carl 44, 153, 225 f., 342

Schoenberg, Arnold 41, 261, 346

Scholem, Gershom 75, 90, 142, 304, 346, 377, 379

Schongauer, Martin 122

Schopenhauer, Arthur 41

Schwartz, Benjamin 206

Schwarz, Karl 60

Schwarz, Ruth 249 f., 337

Schwarz, Simche 249 f., 329

Schweppenhäuser, Herbert 206

Sellin, Ernst 50

Sendak, Maurice 176

Seneca, Lucius Annaeus 37, 39, 364

Sgan-Cohen, Michael 28 f., 107, 302–304

Shimon bar Yochai, Rabbi 100, 200

Shlomo ben Yizhak, Rabbi (Raschi) 78, 363

Shostakovich, Dmitri 179

Signorelli, Luca 343

Simmel, Georg 51 f., 116, 142, 196, 254

Smith, Adam 231

Solomon (bibl. king) 84, 103, 322

Solomon Ibn Gabirol, Rabbi 141

Soloveitchik, Joseph Ber 26, 319

Sonar, Anand 278 f.

Sontag, Susan 180

Soutine, Chaïm 21, 38, 258, 302, 338 f.

Spengler, Oswald 150, 225

Spiegelman, Art 176

Spinoza, Baruch 127, 141, 236, 249

Srbljanin, Predrag 181 f.

Stalin, Josef 168, 254, 318

Starnina, Gherardo 215

Stasov, Vladimir 60

Steiner, George 98, 192, 293, 383

Steinheim, Salomon Ludwig 50

Straus, Raphael 14, 75

Strauss, Heinrich 56

Strauß, David Friedrich 25, 134

Stroop, Jürgen 332

Suárez, Francisco 369

Susman, Margarete 299

Sutro, Abraham 103 f.

Sütterlin, Christa 203

Sutzkever, Abraham 258, 326, 382

Szechter, Pela 249

Szittya, Emil 339

Sznaider, Natan 306

Szold, Henrietta

Tacitus, Publius Cornelius 39

Talayesva, Don 270

Tanner, Jakob 137

Taring Padi (artist group) 30–32

Taubes, Jacob 141, 195, 220, 360, 365, 367

Taubes, Zwi 85, 297, 348

Tavel, Rudolf von 133, 355

Taylor, Charles 138

Terach (bibl. character) 101

i ndex of n ames

Thomas (gospel) 352

Tieck, Ludwig 15

Tintoretto, Jacopo 259, 262

Titus, Flavius Vespasian 111, 165

Treitschke, Heinrich 45, 47, 357

Trnovský, Jan 312, 381

Trnovský, Julia 312, 381

Troeltsch, Ernst 40–44, 47, 53, 99, 137, 196

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph 285

Tumarkin, Igael 27, 29

Tyconius, Bishop 117

Tylor, Edward 199

Tzur, Dan 315, 322

Ut, Huynh Cong Nick 177, 180–184

Uziel, Isaac ben Abraham 363

Uzzah (bibl. character) 88

Valéry, Paul 9

Van Leyden, Lucas 210, 216

Van Oranje, Wilhelm 163

Van Rijn, Rembrandt 23, 163, 196, 220

Van Voolen, Edvard 95

Varlin, alias Willy Guggenheim 256–258, 262

Vasari, Grigorio 247

Vattel, Emer de 369

Verdi, Giuseppe 216

Vermeer, Jan 247 f., 371

Vernant, Jean-Pierre 40

Vetterli, Martin 265

Veyne, Paul 47

Vischer, Friedrich Theodor 45

Vögelin, Friedrich Salomon 134–137, 141, 143, 145, 222, 366

Voltaire 46, 164

Vonrufs, Ernst 381

Voth, Henry R. 271

Wackenroder, Wilhelm Heinrich 15

Wagner, Cosima 152

Wagner, Richard 39, 41, 47, 145–147, 148–154, 165, 302, 357

Wallenberg, Raoul 381

Walser, Robert 15

Walzer, Michael 141, 195

Warburg, Aby 17, 42–44, 50, 53, 99, 109, 196, 199, 202, 231, 236, 238, 268–280

Warburg, Felix 375

Warburg, Paul 237

Weber, Max (artist) 21

Weber, Max (sociologist) 116, 199, 230

Wegmüller, Walter 168 f., 232 f.

Weil, Simone 188

Weiss, Oskar 315

Wellhausen, Julius 134

Wells Ida B. 373

Wertheimer, Jürgen 229

Wiener, Max 357

Wiesel, Elie 252

Wigura, Karolina 119

Winkler, Heinrich August 246

Wischnitzer, Rachel 60, 345 Wise, Isaac Mayer 356 Witt, Hubert 326

Wundt, Wilhelm 199

Wyler, Otto 138, 370

Wyschogrod, Michael 26, 92, 291, 297 f., 354

Xenophanes von Kolophon 110, 229

Yahalom, Lipa 315, 322

Yehuda ha-Chassid, Rabbi 78

Yehuda ha-Levi 339

Yehuda ha-Nasi, Rabbi 99

Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim 50, 305

Zadoff, Mirjam 307

Zechariah (bibl. prophet) 370