Hartmut Dorgerloh and Lars-Christian Koch

The collections of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin include a set of around sixty objects from the Umonhon culture that was assembled by the indigenous ethnologist Francis La Flesche between 1894 and 1898 on behalf of the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde. The objects were consciously selected by him at the time with the intention of representing his own culture — that of the Umo nho n — whose extinction he had reason to fear. The Berlin team, which began to study these holdings more closely in 2017 in order to develop an exhibition for the Humboldt Forum, initially focused on the great challenge it must have been to represent an entire culture with just sixty objects. What objects would we select today to represent our own culture? To how many could we perhaps restrict it? The first ideas for participatory projects with open appeals to the visitors were in the air.

Contacting representatives of the Umonhon Nation in Nebraska and a trip there in the spring of 2018 fundamentally changed these ideas for approaching the sixty objects. At the very latest with the first visit to Berlin by a delegation from Nebraska in the autumn of 2018, it was clear that the theme truly interests people who are directly and personally connected to these cultural objects is a very different one: “We are still here!”

In interchange and close cooperation with representatives of the Umonhon, teachers and students at Nebraska Indian Community College, and descendants of Francis La Flesche, the concept for the exhibition changed to an interweaving of past and present. In addition to pieces from the collection that represent their historical life, representatives of the Umo n ho n tell their stories in the exhibition in a film installation arranged in the round — a design that refers to the circle as the cen-

tral form of the Umonhon. The catalogue that Francis La Flesche wrote to be handed over with the objects to the Berliner Museum in the late nineteenth century explains the significance and use of the pieces to visitors then and now | see pp. 37–106 | . The knowledge preserved in his notes is now being incorporated into the teaching at Nebraska Indian Community College.

The catalogue prepared by La Flesche is the center of the present publication — as a unique document being published for the first time, as a facsimile and complete transcription.

While working on the subject matter and design of the exhibition in collaboration with our partners from Nebraska, common museum terms such as “set,” “artifacts,” and even “objects” increasingly seemed inappropriate to describe this collection. These terms seemed far too sober and objective to approach the significance inherent in these objects. The English word “belongings,” which describes things to which you feel you belong or that belong to you, is far better suited to the emotional connection that is relevant here.

Our great gratitude goes out to the representatives of the Umonhon with whom we were fortunate to collaborate in a way that was also very inspiring to us. We also thank the curators in Berlin who accompanied and advanced the development of this wonderful exhibition with sensitivity and open ears as well as the entire team that made it possible to realize it in this space.

For the Humboldt Forum, this exhibition is enormously enriching and a great step on the path to becoming a place of international polyvocality.

Ilja Labischinski and Elisabeth Seyerl-Langkamp

Francis La Flesche lived his life between two worlds: as an Umonhon (Omaha), he fought for their rights, and as a scholar, he researched his own culture. Today, he is regarded as the first Indigenous ethnologist of North America.

Francis La Flesche stands representatively for the wide range of Indigenous actors without whom ethnological collections would never have come into being. We are no longer familiar with most of these individuals today and/or they have intentionally been made invisible. The focus and attention (still) lies on European and North American collectors. Francis La Flesche is an exception here: today, his work offers us the opportunity to focus on insights into Indigenous agency and its resistance to racism and colonialism as well as the active involvement in the trade of objects.

But what does doing research on one’s own culture as an Indigenous ethnologist mean? To answer this question, one must first understand who Francis La Flesche was and where he came from.

Fig. 2

Francis La Flesche in a suit, undated

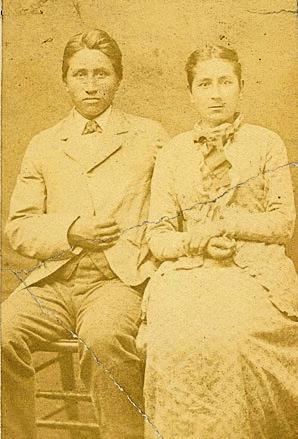

Francis La Flesche was born in 1857 as the son of Ta-in-ne and Joseph La Flesche on the reservation of the Umonhon, in what are today the American states of Nebraska and Iowa. He was his mother’s first child; his father already had three children with his first wife, Mary.

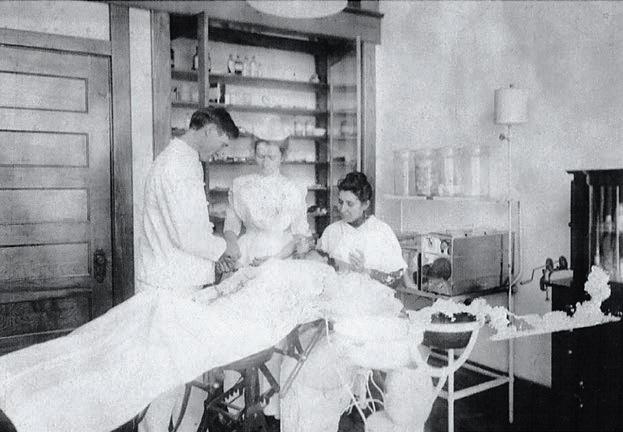

Joseph La Flesche (also known as Estamahza or Iron Eyes) was the son of a Ponca woman (an Indigenous Nation that neighbored the Umonhon) and a French fur trader. After his father’s death, Joseph was adopted by Big Elk, the principal chief of the Umonhon. When Big Elk died, Joseph himself became one of the most influential as well as most controversial chiefs. Along with his first wife, Mary, he was part of a small group that converted to Christianity and lived in an area of the reservation that was disparagingly called the “Make Believe White Man’s Village.” Joseph sent his children to the mission school, where they learned to read and write English on the one hand, but were forced to give up their language and way of life thus far on the other. The mission school offered children additional educational opportunities, which surely also contributed to the fact that two of Francis’s sisters are among the most important personalities of Indigenous North America until today. While Susette La Flesche (1854–1903) became an important activist for the civil rights of Native Americans, Susan La Flesche (1865/66–1915) was the first Indigenous woman in the United State to study medicine and to subsequently establish the first hospital on a reservation. Francis La Flesche was sent to the mission school at the age of eight. He later processed his experiences there in the book THE MIDDLE FIVE . In many of the schools for Indigenous children in North America, violence was part of daily life and systematic psychological and physical abuse of children was common. The motto of the largest of such boarding schools for the Indigenous population, the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, was: “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” The experience of systematic violence and abuse cannot be discerned from the above mentioned book by Francis La Flesche. The experiences at such schools have nonetheless continued to traumatize several generations of Native Americans until today. This system of boarding schools has been regarded retrospectively by those affected, as well as by many historians, as the main reason for events that must be categorized as cultural genocide.

After the mission school was forced to close again in 1869, Francis La Flesche returned to the reservation of the Umonhon. There, Joseph made sure that Francis did not forget how to read and write English. Francis often had to read English books to his father aloud for hours, even though Joseph himself did not understand any English. At this time, Francis La Flesche also took part in important social and religious events of the Umonhon. In contrast to many other Native Americans of his generation, who spent their entire childhood at a boarding school, Francis La Flesche thus learned to live the culture of the Umonhon from a very early age.

Francis La Flesche came into contact with ethnologists and their work for the first time as a young man on the reservation of the Umonhon. James Owen Dorsey (1848–1895) spent several years on the reservation starting in 1878. La Flesche was an important informant and translator for Dorsey. In his work that was published with the title OMAHA SOCIOLOGY in 1884, Dorsey explicitly thanks Francis La Flesche for his support and describes him as a young man who was very interested in the history and culture of the Umonhon. “He has fair Knowledge of English, writes a good hand and is devoted to reading. He is the only Omaha who can write his native dialect.” It was probably this work with James Owen Dorsey that made La Flesche aware of the significance that ethnological methods might have in preserving the culture and history for the Umonhon as well. Through Dorsey, he learned about the possibilities for documenting history, culture, music, and objects and preserving them for subsequent generations.

While Dorsey was still occupied with his research on the reservation of the Umonhon, La Flesche along with his half-sister Susette decided in 1879 to accompany and support the chief of the Ponca, Standing Bear, on his trip through the United States in the struggle to obtain civil rights for Native Americans. Standing Bear’s sixteen-year-old son died as a result of the violent resettlement of the Ponca. When Standing Bear tried to bury his son in the Ponca’s original settlement area, he was

arrested and subsequently brought back to the new reservation of the Ponca in Nebraska. In the court proceedings that followed, Standing Bear was acquitted, with the historically important verdict that Native Americans also have a claim to the fundamental rights provided by the Constitution of the United States of America, which had been adopted roughly one hundred years before. Following the court proceedings, Standing Bear traveled with Susette and Francis La Flesche through the east of the US to campaign for the assertion of the civil rights of all Native Americans that had been recognized by the court.

During this trip, Francis La Flesche got to know the senator from Iowa, who found a position for him as an official at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC. In addition to his work, after a few years, La Flesche began studying law in the evening. He received his bachelor’s degree in law in 1891 and his master’s degree just one year later. At this time, he also got to know Alice C. Fletcher (1838–1923), who would influence his life in the long term.

Alice Fletcher came to Washington, DC in 1882, and also worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She was initially a teacher and had active contact with Indigenous nations while dealing with social concerns as well as land grants. In 1887, she received a commission from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to implement the newly enacted Allotment Act in connection with the Umonhon. The aim of this law was to divide up the land allocated to the Indigenous Nations of North America as a result of the treaty negotiations with the US government into small plots and to distribute them as property to the residents of the reservations. Native Americans were supposed to be reeducated as American farmers who worked their own land. Other forms of land ownership were thus supposed to be made impossible. The objective was also to disrupt the community structures of the Indigenous Nations and to make more land available to white farmers. Alice Fletcher, in contrast, saw this as a possibility to give Native Americans the same opportunities and rights as the entire white American population.

Francis La Flesche accompanied Fletcher on her commission as a writer, translator, and informant. Due to his support for the Allotment Act, La Flesche’s role is regarded ambivalently until today. His commitment was also controversial within his family at the time: his half-sister Susette, who rejected the Allotment Act as violent integration, positioned herself against Francis. Others endorsed this course of action, since they considered it to be the sole possibility to not be driven out of their territory by force, similar to what had happened to the Ponca just a few years before.

Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche simultaneously conducted joint scholarly research on the reservation of the Umonhon. But it was La Flesche who proposed the topic of the research to Alice Fletcher: examining and recording the ceremonies of the Umonho n . Fletcher and La Flesche feared that the objects connected with them would disappear. And along with the objects, valuable knowledge about the nature and significance of the ceremonies that formed the core of the cultural life of the Umonhon would also be lost forever. Alice Fletcher and Francis La Flesche proposed to Joseph La Flesche that the objects be sent to the Peabody Museum at Yale University in Connecticut for safekeeping. Joseph agreed and persuaded the keepers of the objects that this was the right step. The first objects that were sent to the museum were the contents of the Sacred War Tent. They were subsequently joined by the UMON’HON’TI , the Sacred Pole of the Umo n ho n . This was and is the most important object of the Umonhon, which was repatriated to them in 1989.

OMAHA TRIBE . It continues to be the most comprehensive and complete work about the culture of the Umonhon.

Francis La Flesche and Alice Fletcher were closely connected both professionally and in private life. But their professional relationship was not on an equal level. Alice Fletcher was at the time regarded as an established scholar and socialized in corresponding circles. La Flesche, by contrast, despite being held in high regard, was little more than her assistant in her eyes. Over time, however, he received more and more scholarly recognition. Fletcher was not happy about his growing success, perhaps due to the fact that she as a woman in a field dominated by men constantly had to prove herself and was afraid that his success might damage her career.

In 1884, Francis La Flesche was already given the opportunity to present their joint research on the Sacred Pipes of the Umonhon at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In 1890, La Flesche and Fletcher gave separate talks at the National Congress of Music, since they had been

Fig. 3 Francis and his sister Susette La Flesche, undated

After their return to Washington, DC, Fletcher and La Flesche took on different roles at the Bureau of Indian Affairs. But they processed their comprehensive research material together. Fletcher published the first results with the title A STUDY OF OMAHA INDIAN MUSIC and in it honored La Flesche’s role on the title page. In 1910, they finally jointly published all of the results of their research in the 27th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, with the title THE

unable to agree on who should present the results of their research on the music of the Umonhon. In 1895, La Flesche finally traveled alone to the reservation of the Umonhon in order to record and chronicle songs and ceremonies. In 1910, he was hired by the Bureau of American Ethnology as an ethnologist. That same year, he set out to do his field research with the Osage (a neighboring Indigenous Nation of the Umonhon). Fletcher gave La Flesche extensive instructions and advice on how he should conduct his work — an expression of their ambivalent relationship. The results were published between 1922 and 1930 in several volumes consisting of thousands of pages.

The private relationship between the two of them was also very close. Alice Fletcher even officially adopted Francis La Flesche as her son in 1891. They spent their life together in Washington, DC, until Alice Fletcher’s death in 1923. Francis La Flesche died a few years later in 1932. Even his death revealed how he lived between two worlds and how he was perceived by others: in a photo published in connection with his obituary, his black suit was removed and replaced with a fur cape.

Francis La Flesche’s life path was in no way an assimilation of a Native American to a white American citizen. His path and his development were instead determined by a series of deliberate decisions, characterized by self-assertion and perseverance, by compromises and concessions, and by campaigning for the freedom and interests of Native Americans in the United States.

tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One feels his twoness.” Du Bois thus portrays the internal conflict of colonized peoples, of always seeing themselves through the eyes of a racist white society, and of consequently measuring themselves with the means of a nation that looks backward with disdain.

Du Bois described the conflict related to the experiences of Black people in the United States at a time when the US government was occupied with the then so-called Indian problem. The collective land ownership of Indigenous Nations in the Midwest stood in conflict with the colonialization by white settlers. The US government attempted to ban collective land ownership by means of laws and to thus simplify the expropriation of land. The situation of the Indigenous population was thus shaped by loss of land, racism, and violence.

Fig. 4

Susan La Flesche at the hospital, undated

Fig. 5

Susan La Flesche’s hospital on the Umonhon reservation, 2018

“How does it feel to be a problem?,” asked the Afro-American scholar and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois in 1897 in his essay “Strivings of the Negro People,” in which he described the concept of a “double-consciousness”: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the

Like Du Bois, Francis La Flesche also sought a place for himself and the Umo nho n in the still young American nation. The equally young discipline of ethnology at the turn of the century took on an important role in the process of nation-building in the United States. Scholarly research on Native Americans was important for creating a national American identity, with respect to the relationship to Native Americans as well as in order to distinguish itself from Europe. But this also gave rise to the contradictory situation that studies on the traditions, kinship systems, and music of Native Americans were financed by the government that was sending Native American children to abusive boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their language. Moreover, at the same time, the Allotment Act seized land from Native Americans and thus took away the basis of their existence.

At first glance, Francis La Flesche was a typical ethnologist of his era. He was interested in collecting and documenting data and objects as comprehensively as possible. The shared interest of La Flesche and contemporary ethnologists consisted of preserving objects and knowledge. His work was based on his knowledge and collaboration with Indigenous informants, whom he quite rarely

mentioned or honored in his scholarly publications. La Flesche neither questioned the scholarly assumptions that prevailed at the time, nor attempted to change or steer the then still emerging scholarly discipline of ethnology in a different direction. To him, this presumably seemed to be the only possible way to be able to become a recognized ethnologist. Regardless of his views, La Flesche was offered hardly any other option than to affiliate himself with the prevailing ethnological viewpoints and methods.

Nonetheless, if one takes a closer look at the ethnological works of Francis La Flesche, a more complex picture arises. They reveal quite a lot about his motivation and objectives, which apparently did not include formulating texts that were understandable by a broad audience. While he showed in his short stories and the book THE MIDDLE FIVE that he was very much in the position to write for a broad audience, his ethnological works are characterized by tremendous complexity. What emerges from his texts is that he did not see a broad American readership as his audience. But Francis La Flesche presumably also regarded the target group of ethnologists as being of merely secondary im-

portance. It almost seems as if his works were directed first and foremost at the Umonhon themselves, and very likely even at the Umonhon of future generations. The knowledge of the history, the traditions, religion, and culture of his ancestors that he compiled was supposed to be preserved for subsequent generations. La Flesche was interested in the songs and ceremonies of the Umo nho n. He knew that they were central to their cultural life, but nevertheless in the process of disappearing, which represented a threat to the life of the Umonhon. He therefore set himself the goal of recording as much knowledge and information as possible in his books. They were supposed to be as complete as possible. For La Flesche, this was not only a question of scholarship, but also of the cultural survival of the Umonhon.

Francis La Flesche surely found himself in a conflict between obtaining recognition in the professional community of ethnology and his origins as an Umonho n. In order to receive recognition as an ethnologist, he also had to repeat various underlying ethnological assumptions about the Umo nho n and Native Americans in general, regardless of his personal views. This ambivalence specified, so to say, not only the framework in which La Flesche was able to conduct his research, but also his work to preserve the cultural life.

In his work in connection with the Umonhon, La Flesche relied on their cooperation and willingness. It was not only his role as an insider and his personal knowledge that made this research possible. He was able to do his work because he was a recognized and knowledgeable member of the Umonhon. But just as Alice Fletcher depended on him, La Flesche also relied on other Umonhon. Deciding what information he would share and what he would not therefore must have been an ongoing conflict for La Flesche. In 1894, he thus wrote to the director of the Peabody Museum, Frederic Ward Putnam: “Too much of the private affairs of many of the Omaha has already been published by the Bureau of Ethnology without their consent and I do not wish to add more.”

It is therefore not surprising that Francis La Flesche is regarded today as a very controversial individual. Owing to his special position as an Indigenous ethnologist, La Flesche had access to many culturally sensitive areas and data and made them available to scholarship and museums. La Flesche is also controversial until today particularly as a result of his handing over of the UMON’HON’ TI , the Sacred Pole, to the Peabody Museum. Did he do the right thing by bringing objects into safety for future generations, or did he betray his community by handing these objects over to a museum for his own professional advantage?

FRANCIS LA FLESCHE AND BERLIN

A unique insight into the specific perspective of an Indigenous ethnologist of the nineteenth century is offered by a catalogue that Francis La Flesche produced for a collection of objects that he sent to the Königliche Museum für Völkerkunde (Royal Museum for Ethnology) in Berlin in 1898, which are found along with this catalogue today

in the collection of the Ethnologisches Museum. Besides hand-colored photos of the objects and their contexts, the catalogue provides extensive descriptions of individual objects, their significance, and uses. La Flesche thus made use of the photos to illustrate how the objects were used.

In 1894, the Königliche Museum für Völkerkunde commissioned La Flesche to put together a collection of objects from his own culture, the Umonhon. Four years later, the collection, with roughly sixty objects, arrived in Berlin. The collection consists of objects that represent various aspects of the culture of the Umonhon, including ceremonial objects, a war shirt, tools, games, and musical instruments. While we know today that the objects were assembled by Francis La Flesche, the producers of the objects and their previous owners nonetheless remain unknown.

The Umonhon collection in Berlin has a different background in many respects than La Flesche’s collections in American museums: not only was La Flesche commissioned to assemble it specifically for the museum; he also had a large number of the objects produced, since they no longer existed or were already in use. La Flesche’s self-proclaimed goal was

to present a picture of his culture that is as comprehensive as possible. In particular, he selected objects of everyday use.

In his letter to the museum in Berlin, La Flesche repeatedly called attention to the situation of the Umonhon. He thus wrote that there were no weapons in the collection, since all the men who had been warriors were dead, and therefore nobody was left to make these kinds of objects. He also explained that young people were no longer able to produce many of the objects, since knowledge about them had been lost. Materials were no longer available, something connected with the eradication of the buffalo in the course of colonization. The delay in sending the objects to Berlin was not due to the fact that the people did not work hard enough; work on the objects was instead protracted because of their poverty.

told in Berlin. Over one hundred years after La Flesche sent the objects to Berlin, this is now happening in the exhibition AGAINST THE CURRENT: THE OMAHA, FRANCIS LA FLESCHE, AND HIS COLLECTION at the Humboldt Forum.

Fig. 8

Francis La Flesche, original photo, 1933

Fig. 9

Francis La Flesche, retouched photo for his obituary, 1933

10

In the catalogue, Francis La Flesche makes a remarkable assertion: “The breakup of the Omaha’s native organization, the overthrow of their religious rites, of the authority of their Chiefs and of tribal order, and the confusion of mind incident of this sudden overwhelming of ideals, pursuits, and all familiar forms of social life, although a story full of pathos and instruction, must be omitted here as it forms no part of my present duty.”

It almost seems as if Francis La Flesche hoped that the history of the Umonhon would also be

Wynema Morris

Francis La Flesche lived his life during a time of transition in which the Umonhon (Omaha) people faced drastic changes. His monumental work, along with his coworker, Alice C. Fletcher, resulted in what is known as the 27th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. What is written below is a brief description of the social structure of the Umonhon as documented by Francis La Flesche.

The current exhibition in the Humboldt Forum reflects the Umo nho n pattern of circularity and the wholeness of a circle. The circle itself was regarded as holy and sacred as this was perceived to be a favored shape by Wa’kúnda, the Creator.

The Umonhon expressed in their social structure the firm belief in the duality of life. Two opposites make a whole. As an example, night and day make a full day. The cardinal directions of north and south make a whole. The sun follows an east to west path, thereby giving the four cardinal directions that are most familiar to humankind. However, the Umonhon were aware of and acknowledged three more additional directions resulting in seven directions: up, down, and the center.

What Francis La Flesche described and what comes down to

the Umonhon of today is the Sacred Circle represented by ten clans placed in specific spaces within this circle. The duality reflected in the formation of the circle consisted of the two halves of north and south. The northern half was considered as representing the Sky, while the southern half represented the Earth. Thus, you have the joining of Earth and Sky to complete a whole. The opening to the sacred circle, particularly during the Umonhon annual bison hunting enterprise, always faced to the east toward the rising sun. Each side of the circle, north and south, was represented by five clans each for a total of ten clans reflecting the formation of the Sacred Circle. This completed the wholeness of the People, in accordance with the form most beloved by Wa’kúnda.

ELK CLAN. The first of the clans, as you enter the Sacred circle going left to right, is that of the Elk Clan. Each of the clans had major responsibilities for the overall welfare of the tribe; each guided and led by a “head man.” According to La Flesche, the Elk clan also possessed a “Sacred War Tipi” and was responsible for the conduct of warfare. One of the head of this clan’s specific duties included maintaining the sacred tent of war. It was constructed close to the headman’s tipi. This was referred to as the “War Tent.” The term “tent” is used to refer to the term “tipi” as is used today. The Elk Clan Headman’s duties were to ensure the care and maintenance of all the sacred items in ceremonies in preparation for going to war when necessary. Among the many items to be taken care of were the “Sacred Pipe for War.” It was the most sacred item and was smoked in a sacred manner prior to warfare. According to La Flesche, going to war was the act of last resort. The Umonhon did not engage in warfare as an aggressive act. It was primarily to resume peaceful means. Afterall, the Umonhon realized that constant warfare yielded only starvation and death. It was the Elk Clan’s duty to protect the tribe, to train its warriors, and

Inshta'cunda Tapa'

to conduct retaliatory warfare and to maintain peace at all costs.

Interestingly, La Flesche tells that after the last retaliatory response to war, the headman and his assistants announced their duties were at an end. The United States had taken most of the original lands set aside for the Treaty of 1854 and reduced the reservation lands even further in 1882. In addition, the United States Cavalry kept close watch on those tribes who traditionally attacked the Umonhon. War was no longer necessary. As such, the War Tent was no longer needed. In regard and reverence to elk, deer, and antelope this clan did not touch or eat any part of these animals.

SHOULDER

FALO). This clan, in reference to the large dark hump of the American bison, was next in line after the Elk Clan. The major responsibility carried out by the Black Shoulder Buffalo Clan was that of providing internal peace and order among the people. In addition, they sang the marching songs and set the pace for

a – Sacred Tent of War b – Tent of Sacred Pole

c – Tent of Sacred White Buffalo Hide – Location of Pole during He'dewach

the people when going on their buffalo hunt, from approximately April through September, each year. According to La Flesche, the people when on the march formed a group that was one and half miles long and two miles wide. It must have been quite a task to get everyone together in order to reach the destination together.

Another of the Black Shoulder Buffalo clan’s tribal obligations was that of distributing the butchered buffalo meat to every family in a fair and equitable manner. Larger sized families would obviously receive larger shares of fresh meat. Smaller families received smaller shares, and no one disputed the amounts received. After all, every family had a male member who would be involved in the hunt. They all had to rely upon each other to make the hunt successful for the entire tribe. Hoarding by any family was strictly frowned upon and viewed as greed.

Those belonging to this clan were forbidden to eat any part of

Fig. 2 Tribal Organization of Sacred Circle.

Based on The Hu’thugah – The Umonhon Tribal Form

Fig. 3

The participants of the Umonhon and Ponca language conference at NICC, 2021