The Platonic Football

Manuel Neukirchner

The object of desire is the ball. It is a round fetish and a perfectly shaped globe. It lies within the bounded field and yet wants to have those boundaries dissolved. The ball is adeptly chipped or fearlessly hammered, magically conjured up or devotedly kissed. Leonardo da Vinci studied its original form. His drawing of an edge model of a polyhedron made it possible for the first time to see the geometric volume ’ s thirty faces, sixty corners and ninety edges simultaneously. ‘ Truncated icosahedron’ is the name of this three-dimensional form. From a mathematical perspective, then, the football is a truncated icosahedron. That makes it one of the thirteen Archimedean solids. The still-lifeless object becomes round when it is filled with air. Once life has been breathed into it, people set it in motion. Then the ball rolls, flies short or long, low or high, spun with effect or straight as a line. Its rotation is perfect. It rises from the ground, seemingly overcoming gravity in its audacious flight. We watch the ball and are amazed.

We know that the ball is round from the legendary coach Sepp Herberger. That which is round is self-contained. And that which is self-contained is at one with itself. And that which is at one with itself approaches the idea of the perfect. All the points of the surface of a ball are equidistant from its centre. The ball – the circle translated into three dimensions – symbolises completeness and wholeness; it stands for the sublation of geometric antitheses, for the overcoming of time and space and for eternity.

In the beginning was the ball, and in the beginning is Plato. In his late dialogue Timaeus , he describes with fairy-tale-like vividness the cosmos as a spherical body shaped by the creator. God breathed a soul and reason into the round form. That is why an earthly order and beauty can emerge. For Plato, the universe is a complete, spherical living entity, and human beings are likenesses of it. They reproduce the round form of the whole world, which is visibly expressed in their holding their heads

An Icosahedron

(page from the manuscript De divinia proportione ) 1502

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519, ITA)

Colour illustration, 28.5 × 20 cm

38

upright. ‘Four limbs which could bend and stretch’ – the arms and legs with hands and feet set the body in motion and contribute to its control. The anima mundi , or ‘soul of the world’, became a concept in Plato’s philosophy of religion and nature. As the macrocosm, the universe should be structured analogously to the human being, as the microcosmos.

In all eras and on all continents, people have sought the laws of the world in the geometry of circle and sphere. Applied to life, round became the symbol of the perfect, for beauty, but also of the unpredictable, because being round also means taming the inherent dynamic that results from movement. The round, the sphere, the ball became a projection screen of timeless significance, the likeness of God in antiquity, symbolised by the heavenly sphere with a cross or the globe that Jesus Christ holds in his hands. The circle and the sphere as symbols of the all-embracing order, together with the question that people have been asking since time immemorial: what powers rule the cosmos, space and time? Kazimir Malevich, the leading figure of the Russian avant-garde, found an answer for himself. In reality, he believed, the globe has no bottom, no top, no perspective, no weight. It does not have the most important thing on which our knowledge of the world is based: relativity. How profane the rules of football seem given that thought. Rule No. 2, the Ball: it must be spherical, have a circumference of at least sixty-eight centimetres and at most seventy centimetres; at the beginning of the game, it must weigh at least 410 grams and at most 450 grams and have a pressure of 0.6 to 1.1 atmospheres (600–1100 g/cm 2 ). The perfection of the spherical body has found its Platonic pendant in the football.

Painting makes it possible to experience the football and everything connected with that fascinating object: its laws, its secrets, its contradictions, its meaning for people, its aesthetic, its rawness and its disruptive changes. Art narrates the football. It deciphers it, finds the special moment that contains both past and future, that visualises the crucial moment of sudden reversal on which Lessing reflected in his Laokoon, oder Über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie (Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry). Modern artists added an important chapter to the monumental cosmos of reflexions on the football. They are engaging in a unique dialogue; they are creating a fascinating tension between the sport and its mimesis in art. Modern painting sets out in search of clues; it touches on the big questions of the origins of the pitch and the rules, of the unpredictability of foot and ball, of the contingency of the game, of the scenes of unbounded emotions, of the overloading of total media illumination. Why do millions worldwide, on the smallest clay courts, on playing fields, in backyards or in big arenas, succumb to the spectacle? Art provides answers. The artworks emerge from the echo chambers of football and life.

39

In modern painting, the genesis of football happens before the viewers’ eyes. In the beginning, everything is in motion. Everything is floating. Everything is particle and disorder. Then lines form. Sign-like and mysterious demarcations appear in space. Outlines of a pitch form and sketch the outlines of the drama. This side and that, our field, your field. Forbidden zones. Elements of a new order are visible – the elements of the new game. But the game needs the body; only then can the dance between earth and heaven begin. Attached shadows bring the new world to life. The bodies of the players take form just as artistic abstraction becomes a figure. If the players are released, they show their skill in wild leaps, aerial duels and diving saves. In its best moments, the football is detached from the earth. Its fate is decided in mid-air. All eyes are aimed at the action. Time seems to stand still. In the fourteenth century, young men in England, the motherland of football, still drove the ball forwards as if on a battlefield. Despite being prohibited by the crown, which feared for the military fitness of its recruits, the villagers arranged to meet for the anarchic struggle over the ball. They faced one another without set playing times or compulsory team sizes. The stronger ones sunk the ball behind the opponents’ goal marking. The early forms of the organised game were bloody; everything was permitted. The anarchic football followed instinct and became the identity formation and conflict management of the village. Only rules civilised the game. Only those who kept to the agreed-upon rules could win the match. The rule-based game become a system among equals; the prerequisite for equality of opportunity was met. The game unfolded in the regulated and legitimised form of the match; the trial of strength in civilised garb acquired a cathartic effect.

The site of the game is a manageable world with its own rules, rituals and clear boundaries for every milieu. The football pitch is an asylum of feelings, from rage to bliss. Emotions spread and multiplied in the live experience in a crowd. The football opened up to its outside world. Ever-larger swarms of people entered the inner world of this fascinating closed system. Yearnings and hopes accelerated the pace. The recurring celebration of enraptured feelings pushes back against the monotony of daily life. Football is true happiness! The entirety of life becomes palpable on the pitch: victory and defeat, rise and fall, teamwork, struggle and pathos carry the powerful experience.

In the stadium, the people become one with themselves and with the team. Bounded in hope and fear, they scream the names of their idols, for they are their representatives on the pitch. The crowd becomes part of a grand narrative. Life dreams become true or are destroyed with the final penalty kick. Team, fan and club – that is the new Holy Trinity. Fans go on a pilgrimage to the home match or enter the stadiums of others like the crusaders of their football god. The football religion is borne by the eternal hope for salvation. In that spirit, both fans and players celebrate their rituals. Identification appears to be the supreme commandment. At the centre of the admiration stand the stars, the team leaders,

Arsenal vs Sheffield, FA Cup Final, Wembley 1936

Charles Cundall (1890–1971, ENG)

Oil on canvas, 63.5 × 91.4 cm

40

the captains, the playmakers, the scorers. Players become legends in their own lifetime. The heroes of the game embody the desires of their admirers. Candles are lit for them and even altars built, as in Naples for the legendary Diego Maradona. The crafty winger, the inspiring artist, the versatile assistant and the unbridled warrior on defence – different types are ascribed to players as if Carl Gustav Jung’s archetype theory had been transported to the pitch. The rebel, the magician, the hero, the lover, the fool, the everyman, the leader, the ruler, the creator, the innocent, the wise, the discoverer – they are all associated with characteristics that always remain the same, in life and on the field. Every generation speaks in awe of heroes and their miraculous deeds. The historical retelling manifested them in the collective memory; the life emotions of entire eras are focussed in them. Epochal triumphs are indelibly preserved in football memory, just as national tragedies are never forgotten. Football’s culture of memory lends a historical dimension to events. Football thus never lives just for the moment but always for memory as well, conserving the instants and making them immortal for eternity. The football stadium is like a large concert hall: the violinists of a symphony orchestra must be as coordinated with one another as the back four of the team in a pressing game. That is the obligatory programme. The free programme is the interplay of the violins with the flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons and brass, with the trumpets, trombones, timpani and xylophones. If one small part fails to mesh with the other, the sonic order is disturbed; only when all members of the team move towards the ball when the opponent has possession of it can the spaces be ideally closed. But what happens when the left fullback keeps too much distance? What happens when the second violin falls out of rhythm? The complex gets out of joint when a single part breaks from the common whole. The football game is a closed system. The players on the field generate order and disorder,however much the coach tries to the influence the rhythm of the game from the sidelines (cat. 155) . No action proceeds like another; the unpredictable plays just as much a role as situational in ability or the splitsecond stroke of genius. The game results from the moment but the moment is insidious. It does not help when plays have to be studied again and again in training like stereotypes – a wrong moment, inattentiveness, a wrong decision can throw things off just as one player’s wrong note can cause the entire symphony orchestra to despair.

Mathematically, the perfect-looking Platonic ball turns out to be a deceptive appearance, since its geometric body cannot be precisely calculated, not with whole numbers nor roots nor fractions. With the help of the transcendental number pi, which is the ratio of the circumference to the diameter, only an imperfect approximation is possible. Once set in motion, law of chaos dominated the path of the sphere. Football is a game, and we know since Novalis that play is experimenting with chance. Therein lies the secret and power of football or, to employ another Herbergerism: people go to the stadium because they don’t know how the game will turn out.

Football has the dramaturgy of a large popular theatre and is even superior to it. In the theatre, the outcome of the struggle is known. The roles are distributed. In Friedrich Schiller’s linguistically and visually powerful tragedy Maria Stuart, Queen Elizabeth I shuts out her rival. In a football game, surprising dribbling can turn the game on its head at the last second. No tragedy can cause the audience to mourn as sincerely as a goal by the opposing team in stoppage time. In the tenth scene of the fifth act, the audience suffers with the Queen

41

of Scotland, foreseeing the disaster approaching her. Mary’s death sentence is inevitable and is carried out. How abrupt, by contrast, the sorrow and tears of the French seemed when Kingsley Coman and Aurélien Tchouaméni lost their nerve in the World Cup final against Argentina in 2022 and stranded the proud Bleus and an entire country in the penalty kicks. Football teaches people to think in the subjunctive form of possibility. Football teaches people that something can change in seconds. Football teaches people that the path to the game always passes through struggle – that is why Bertolt Brecht, too, regarded football as an object lesson for revolutionaries. For him, football was the ironic provocateur, the most fruitful art form of the twentieth century.

In the eye of the camera, which does not miss a single spot in the stadium, football has long since lost some of its magic. Much has changed since Brecht’s football of the 1930s, when the experimental and nonconformist dramatist wrote in the Literarische Welt that the 6–2 victory of FC Schalke 04 over SV Arminia Hannover was the artistic event of the year 1929, with Ernst Kuzorra’s traps, August Sobottka’s flying saves and Hans Tibulsky’s overhead kicks, which he studied in detail with great relish. For Brecht, football was an experience in the stadium with a wonderfully partisan audience who whistle, smoke and sing but are not prepared to tolerate every performance the way a concert or theatre audience in formal attire does. These days, television turns the football stadium into a parallel world. Perhaps Brecht, the founder of epic theatre, would have delighted in the fact that changes in how it is watched have turned football into the total theatre. The perspective of viewing has changed. The cameras serve the sport up as a product; broadcasts distort time in slow motion; they preserve the uniqueness of the moment for eternity in the replay. Games in the top national leagues are broadcast in their entirety worldwide, and even regional league and youth games in Germany are automatically recorded with full HD camera systems and streamed live by specialised providers on the internet. The monitoring of the game has become a habit. Statistics are becoming an obsession; the so-called heat maps of analysts tell us everything about paths, distances, opponents and expected goals. We feel like experts who are in no way inferior to the coaches because we know every detail about counter-pressing, defending in space and winning second balls. When cameras and photographers document and illuminate the game from all angles, when live statistics dissect the activities of players who have become transparent, when the measure of pass completion rates, goal probabilities and radii of movement convey the perfection or imperfection of the game, then coaches, players, fans and all observers will recognise: the final unpredictable factor is the ball.

The sport of football has been marked by a long history of intense identification. Few other cultural phenomena so closely interweave the polarities of human life. No other sport produces such a bond, independently of origin and social milieu. In football, the order and structure of the game meet the emotional tempests

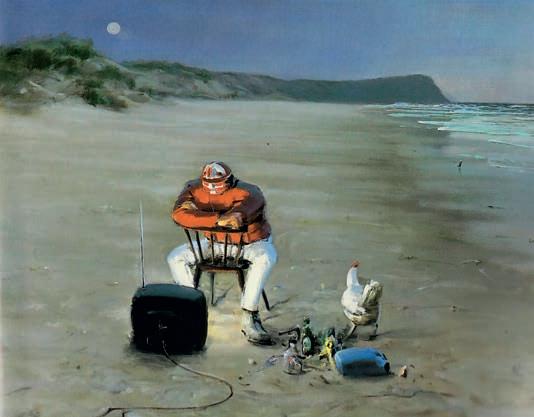

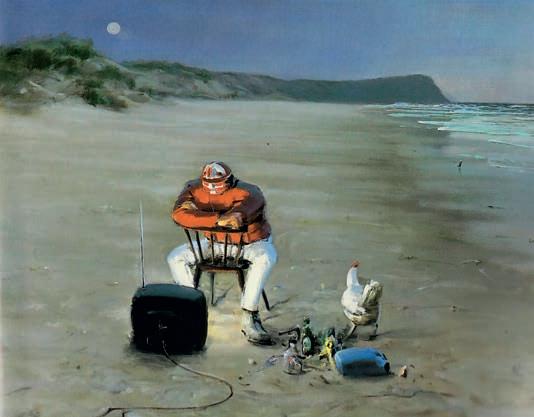

Football Hermit

Poul Anker Bech (1942–2009, DNK)

Oil on canvas

42

and euphoria of the fans. Even the information of data and facts is associated with strong emotions in football. Results trigger enthusiasm or despair – and often excesses and violence as well.

What does it do to football when violent people abuse the big stage of a public stadium to display their hate? When fans turn into fanatics, when their displeasure, their social stress, their problems at work and the emptiness of their lives cause them to resort to violent extremes on weekends? They hide their fears and desires in the anonymity of the crowd. The competition on the turf moves to the stands and becomes a ritual hunt, a stylised battle and symbolic event. The enthusiasm and admiration for the game, teams and players bears a stigma when violent fans cause mass panic, which happened in Heysel Stadium in Brussels (cat. 76) in 1985 and resulted in thirty-nine deaths. On Saturday, football is war, say the fans. Football is always war, said the former Dutch national coach Rinus Michels. Is the ball always still round?

What does it do to football when the eye level between players and fans of the game is only a distant, distorted image? Commercialisation dominates the play. The football-playing millionaires of the new millennium move in entirely different spheres than their cheering fans, who buy their jerseys, sleep in their bedsheets, travel great distances to their away games so they

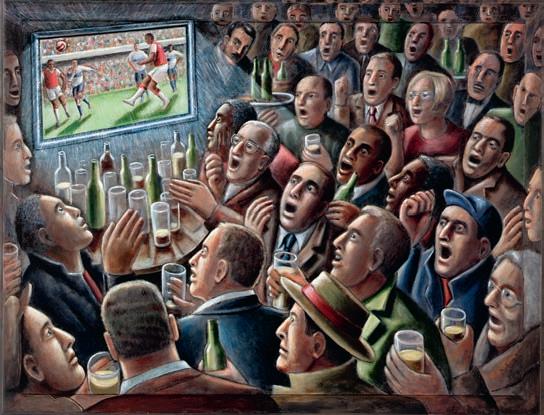

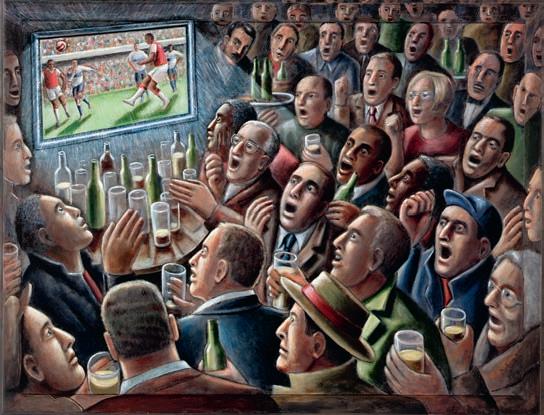

P J Crook (b. 1935, ENG)

Acrylic on canvas, 101.6 × 132 cm

are very close to their clubs and stars even on a small scale. Who is there for whom? The faces of football testify to alienation, to tears in the system. Fundamental issues are in question. The unity of club, team and fans is at risk when the symbolism of kissing the club emblem when celebrating a goal becomes an empty gesture, when symbolic figures chase the next higher salary. The old love needs a new foundation. The ball is losing air.

In stadiums and on playing fields, we experience homophobia, misogyny, racism and other forms of intolerance and exclusion. Homo fanaticus has long since appeared on the stage. It is not easy for people who are enthusiastic about football to prove their fidelity and passion week after week when horrendous transfer payments and exorbitant salaries of players do their part to widen the rift between the business of pro kickers and their fan base. And yet, the crowds stream into stadiums, millions of people of different ages and sex live their dream of football week after week all over the world, on the pitch, in the stands, in their thoughts, in their memories. Their emotions hold them captive; their passion is stronger than the vexing image of ugly football, which they tune out as soon as their own club or own national team makes the unpredictable a reality, when the surprising moment turns everything upside down, when the tragic defeat unites the sufferers in pain, when the small upset the big, when the exuberant joy around you makes you forget everything, when the shared experience becomes a feeling of pure happiness, when our imagination becomes the final paradise from which we don’t want to be expelled, when the fan bluntly reveals himself

43

The Adoration 2006

to the radio reporter’s microphone: Schalke is like the family I never had. The emotions of football are genuine. They make football one with the people. The people never want to cease being part of this utopian and dystopian football. They accept it in all its imperfection. Because the Platonic football is as imperfect as they are.

Chelsea Plays Arsenal

1953

Christopher Chamberlain (1918–1984, ENG)

Oil on canvas, 120.6 × 243 cm

44

Bibliography

Brecht, Bertolt. ‘Das grösste Kunstereignis 1929’. NZZ Folio: Zeitschrift der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung, no. 9 (September 1997).

Bredekamp, Horst. Florentiner Fussball: Renaissance der Spiele. Berlin 2001.

Elias, Norbert and Eric Dunning. Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Civilising Process. Ed. Eric Dunning. Oxford 2008.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Traum und Traumdeutung. Munich 2001

Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim. Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry Trans. Edward Allen McCormick. Baltimore 1984.

Plato. Timaeus. Trans. H. D. P. Lee. London 1964.

Plato. Laws. Trans. R. G. Bury. 2 vols. Cambridge 2014.

Schiller, Friedrich. Mary Stuart. Trans. Sophie Wilkins. Woodbury 1959.

Tates, Sophie, et al., eds. Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde. Exh. cat. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Cologne 2013.

Wullen, Moritz and Bernd Ebert, eds. Der Ball ist rund: Kreis, Kugel, Kosmos. Exh. cat. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Berlin 2006.

45

The Art of the Game

Michael J. Browne (b. 1963, ENG)

1997

Oil on canvas

305.5 × 254 cm

National Football Museum, Manchester (on loan from Éric Cantona)

Éric Cantona rises Christ-like from a sarcophagus, in front of which several fellow players have gathered. Apart from his stoic gaze and the tattoo on his chest, few details disturb the historical look of the scene, not least because a triumphal march is making its way in the background. The title of Michael J. Browne’s monumental painting is deceptive in that sense. Nevertheless, it makes no reference whatever to the sport of football. The Art of the Game instead addresses United’s return to the grand stage of football allegorically by referring to two masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance.

The British artist adopted the pose and attributes of the protagonist of Piero della Francesca’s fresco The Resurrection from around 1463 – indeed, apparent allusions to it, such as the prominently placed foot and supposedly English flag, turn out to be direct borrowings. By contrast, the modern faces of the men resting in front of the tomb are distinct from the original: rather than sleeping soldiers, Nicky Butt, David Beckham and Phil and Gary Neville watch over the risen Cantona. The halo above the head of the figure of Christ has given way to a laurel wreath, which leads us to a second story in the background.

Down to the triumphal arch that is the upper termination, the painter was inspired by a work by Andrea Mantegna from 1488, which showed the victorious Julius Caesar in a chariot. In Browne’s work, in turn, it is no one less than Alex Ferguson who is enthroned as the spiritus rector of the success, higher even than

Cantona; he, too, is honoured with a laurel wreath. During his twenty-six years as manager of Manchester United, the Scotsman won thirteen national championship titles – four of them together with the French enfant terrible, whom he had signed in 1992.

The picture tells yet another story, however, since while it was being painted Cantona was sitting out an eight-month ban for having kicked a fan in reaction to a racist insult. The Art of the Game thus alludes not only to the ‘resurrection’ of the club but also to the long-awaited return of its key player, who sat for the artist during his suspension. Cantona purchased the painting as soon as it was completed; that same year, he surprisingly ended his career at the age of thirty.

Before Michael J. Browne completed his studies at the Chelsea School of Art and Manchester Metropolitan University and became famous for his allegories of sports legends, he grew up in Moss Side in south Manchester, less than two kilometres from Old Trafford. It is all the more understandable that he responded to the question of the art of the game by portraying Cantona, the player who stands for Manchester’s triumphs of the 1990s more than any other. In this composition, in contrast to his team members, he has long since departed from the earthly sphere. The painter paid a similar homage to only one other United player: for his depiction of George Best in 2009, he had recourse to Raphael’s Transfiguration FS

126

127

Football

Robert Delaunay (1885–1941, FRA) 1918

Watercolour on two superimposed sheets of paper mounted on grey cardboard

46 × 47 cm

Centre Pompidou, Paris

The format of Robert Delaunay’s watercolour already shows that he was playing with the world of football. Two coloured sheets are mounted on grey cardboard; the outer one is circular. Numerous circles lie around a yellow centre that suggests the sun. This radial arrangement and the constantly changing colours set the system in motion. At first glance, it looks like a planetary system. The colours of the rings and circles are determined by the primary colours red, yellow and blue, and their corresponding complementary colours are also employed. The inner circles are dominated by red, yellow and orange, creating an impression of warmth, while cool blue tones dominate the edges.

In 1915, Robert Delaunay and his wife, Sonia, met the Russian curator and ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev in Madrid. Their collaboration led to set designs and costumes for the ballet Cleopatra in London in 1918. The artist created the football watercolour for a project that he wanted to develop with the dancer Léonide Massine and the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla. A letter from Delaunay to Massine testi es to his enthusiasm for the project and contains several details about how he imagined the stage design for the ballet performance. He wanted to shoot the ball into the universe and create a mad oeuvre full of joie de vivre. Full of hope, the artist wrote about the great success he hoped to achieve by combining an avant-garde stage design with modern

music. Delaunay was inspired by the idea of presenting dancers in colourful costumes on rotating, coloured disks. The stage set was to be complemented by syncopated jazz music. The ambitious project failed. What remains is a watercolour that was supposed to set the world of the stage in motion by turning the football into a cosmic symbol and making all emotions shine with its colours.

Delaunay was essentially a self-taught artist from a wealthy family. In France, he created the first abstract painting in the 1910s. He already had recourse to the circle for that. The synesthetic connection of painting and music was at the same time important to his artistic work: he speaks of dissonant and consonant colours that simultaneous contrasts cause to resound. His openness to new musical paths is also demonstrated by the fact that he painted a portrait of Igor Stravinsky the same year as the football picture. The artist’s themes also prove he was a decided avant-gardist. His interest in aviation and jazz and his penchant for repeatedly depicting the Eiffel Tower testify to his modern world-view.

On the German art scene, Delaunay had become known above all thanks to his participation in the Blaue Reiter exhibition at the Galerie Thannhauser in Munich around the turn of the years 1911–12. The couple spent the First World War on the Iberian Peninsula and did not return to Paris until 1920. JM

148

149

Picture Credits

Cover Dieter Asmus, Torwart, 1970–71

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Page 4/5 Umberto Boccioni, Dynamism of a Soccer Player, 1913

© Heritage Image / Fine Art Images / akg-images

Page 36/37 Torsten Schlüter, Stadionskizze X, 2003

© Torsten Schlüter, Berlin 2024

Page 38 Leonardo da Vinci, De divina proportione

© akg-images / Mondadori Portfolio / Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana

Page 40 Charles Cundall, Arsenal v Sheffield, FA Cup Final, Wembley, 1936

© Estate of Charles Cundall. All rights reserved 2024 / Bridgeman Images

Page 42 Poul Anker Bech, Fodbolderemit

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Page 43 P J Crook, The Adoration, 2006

© Pamela June Crook. All rights reserved 2024 / Bridgeman Images

Page 44 Christopher Chamberlain, Chelsea Plays Arsenal, 1953

© Wingfield Sporting Gallery, London, UK / Bridgeman Images

Page 127

Page 149

Michael J. Browne, The Art of the Game, 1997

© Michael J. Browne, Manchester 2024

Robert Delaunay, Football, 1918

© bpk / CNAC-MNAM / Philippe Migeat

The publisher and editors have endeavoured to obtain all image rights. If rights holders were unintentionally omitted, their claims will be addressed within the framework of the usual arrangements.

Editor

Manuel Neukirchner

Managing Editor

Carina Bammesberger

Authors

Marion Ackermann, Horst Bredekamp, Lutz Engelke, Josephine Henning, Jürgen Müller (JM), Manuel Neukirchner, Malte von Pidoll, Frank Schmidt (FS)

Editorial Assistance

Knut Hartwig, Janine Horstmann

Copy-Editing, German

Michael Konze

Translation, German to English

Steven Lindberg

Copy-Editing, English

Aaron Bogart

Editorial Design

K-werk Kommunikationsdesign, Dortmund

Eva Lotta Landskron

Printing and Binding

Grafisches Centrum Cuno GmbH & Co. KG

Published by Deutscher Kunstverlag

Ein Verlag der Walter de Gruyter GmbH

Berlin Boston

www.deutscherkunstverlag.de www.degruyter.com

© for this edition: Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH

© for the texts: DFB-Stiftung Deutsches Fussballmuseum gGmbH and the authors

© for the illustrated works and photographs: VG Bild-Kunst and the artists/ photographers and their copyright successors and representatives

First edition 2024

Cover and Jacket Illustration

Dieter Asmus, Goalkeeper, 1970–71

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.dnb.de.

All rights reserved

ISBN: DE: 978-3-422-80134-9 / EN: 978-3-422-80178-3

Colophon