CITY HALL ART PLAN

Over the course of six books, this report fully details the activities and outcomes of the Reimagining Columbus project, through which the City of Columbus, Ohio reckoned with its relationship to the explorer Christopher Columbus.

THE SIX BOOKS IN THIS SERIES INCLUDE:

BOOK # 1

provides insights into how the City of Columbus came to display a Christopher Columbus statue on the grounds of its City Hall, why that statue was removed in 2020, and how the Reimagining Columbus project was designed to help the city determine what to do with it going forward.

BOOK # 2

describes research the project team undertook to discover the many stories that have played out among the people of Columbus, Ohio since long before it became a city, the truth of Christopher Columbus and his conduct in the New World, and how an explorer who never reached the United States became a symbol of all its promise.

BOOK # 3

outlines the community engagement methodologies employed throughout this project and chronicles the events and activities offered by the Reimagining Columbus project team, as well as findings from these conversations.

BOOK # 4

connects the project team’s research findings and community engagement results to the design principles that informed concepts for a new space in which residents might one day experience the reinstalled Christopher Columbus statue.

BOOK # 5

applies the design principles developed from research and community conversations, and best practices in placemaking, to articulate how a new statue site should look and feel, how visitors should be able to interact with it, and how it could engender profound experiences that reverberate for generations.

BOOK # 6

offers an Art Plan for City Hall Campus to guide the implementation of future public artworks there.

Original materials developed through this program are available at reimaginingcolumbus.com , or upon request.

Reimagining Columbus is funded by the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project, a multi-year commitment aimed at transforming the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented.

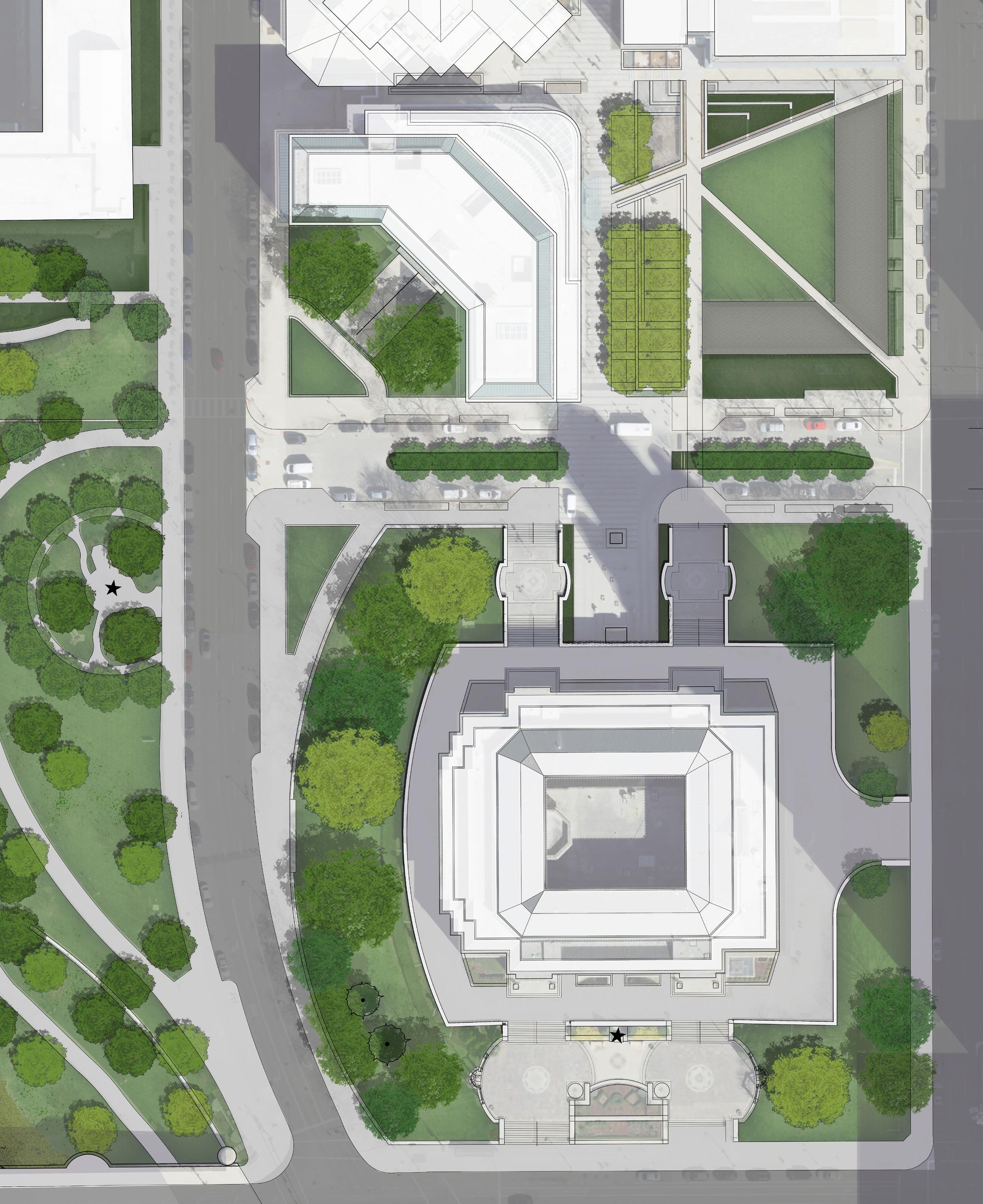

Since July 2020, the plinth at Columbus City Hall where a Christopher Columbus statue stood for 65 years has remained empty, and city leaders are clear that it will not be reinstalled there. Through the Reimagining Columbus project, design recommendations for a new space in which to install the statue were developed (see Books 4 and 5). The project further called for an art plan to inform how the city might develop an art collection to activate City Hall's various exterior spaces. In 2023, the city pledged $1.5 million towards new public art for the campus, with Councilmember Emmanuel V. Remy saying at the time, "I believe this investment...will help move our city forward while creating thoughtful, interactive spaces for our community to share history, stories, and truth." Indeed, the community conversations that occurred through Reimagining Columbus affirmed residents' desire for such spaces.

Book 6 of the Reimagining Columbus Final Report — the Columbus City Hall Campus Art Plan — channels insights from the Reimagining Columbus project, as well as an analysis of the campus' history, site characteristics, and current usage, into recommendations for art that meaningfully reflects all who call the city home. Though it provides examples from other cities for inspiration towards that end, it does not prescribe particular artworks, public art typologies, or artists; the city will need to undertake a process to make these determinations when it is prepared to invest in a new piece or pieces. Next steps to guide this process are provided at the book's conclusion.

All photos, maps, drawings, and renderings in this book were generated by Designing Local from 2024–2025 unless otherwise sourced.

• Art in publicly accessible spaces at City Hall will reflect community engagement findings from the Reimagining Columbus project and be consistent with its goals and outcomes.

• Art on City Hall's Campus will respond to the unique functional and aesthetic conditions of the site and offer a range of experiences for viewers. It will balance weighty topics with those that inspire joy, energize the public, and encourage civic engagement.

• The Art Plan for City Hall builds on the original intention for City Hall to be a welcoming civic space for all Columbus residents.

• The implementation of art at City Hall should be based on national best practices and facilitated through a community-focused process led by experts in the arts, design, landscape architecture, urban planning, historic preservation, and arts administration.

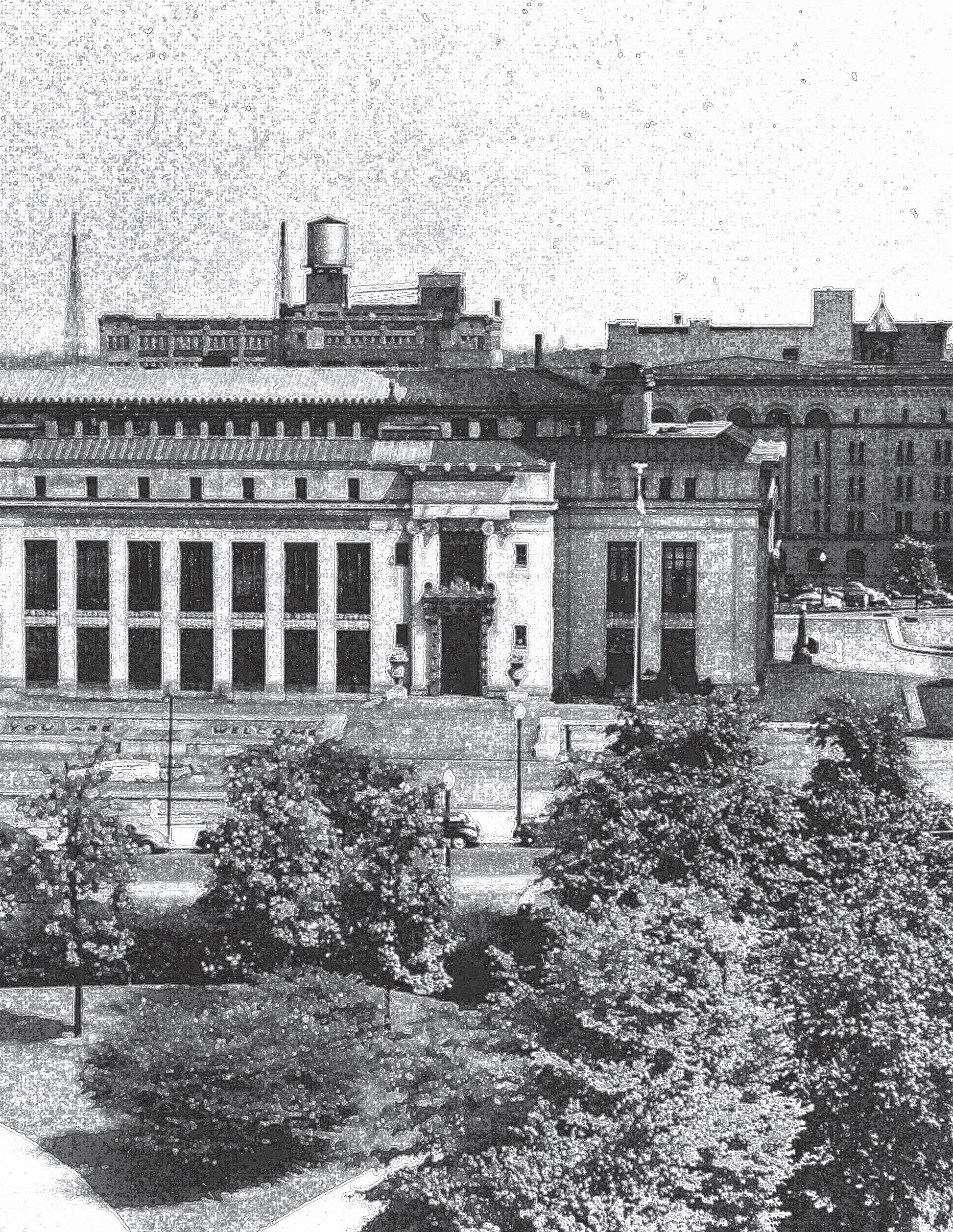

Since 1928, City Hall has been the City of Columbus’ most significant cityowned building, in terms of its function and symbolism. The historic building houses offices for elected officials and city staff, but it is also the primary public space in which democracy unfolds in the city. Symbolically, City Hall represents the city’s democratic government and underscores the importance of Columbus as Ohio’s capital. Designed in the Greek Revival style, City Hall’s architecture and material choices convey democratic values such as prosperity, civic idealism, and symmetry. The building was not the first of Columbus’ administrative buildings, but it has proved the most enduring.

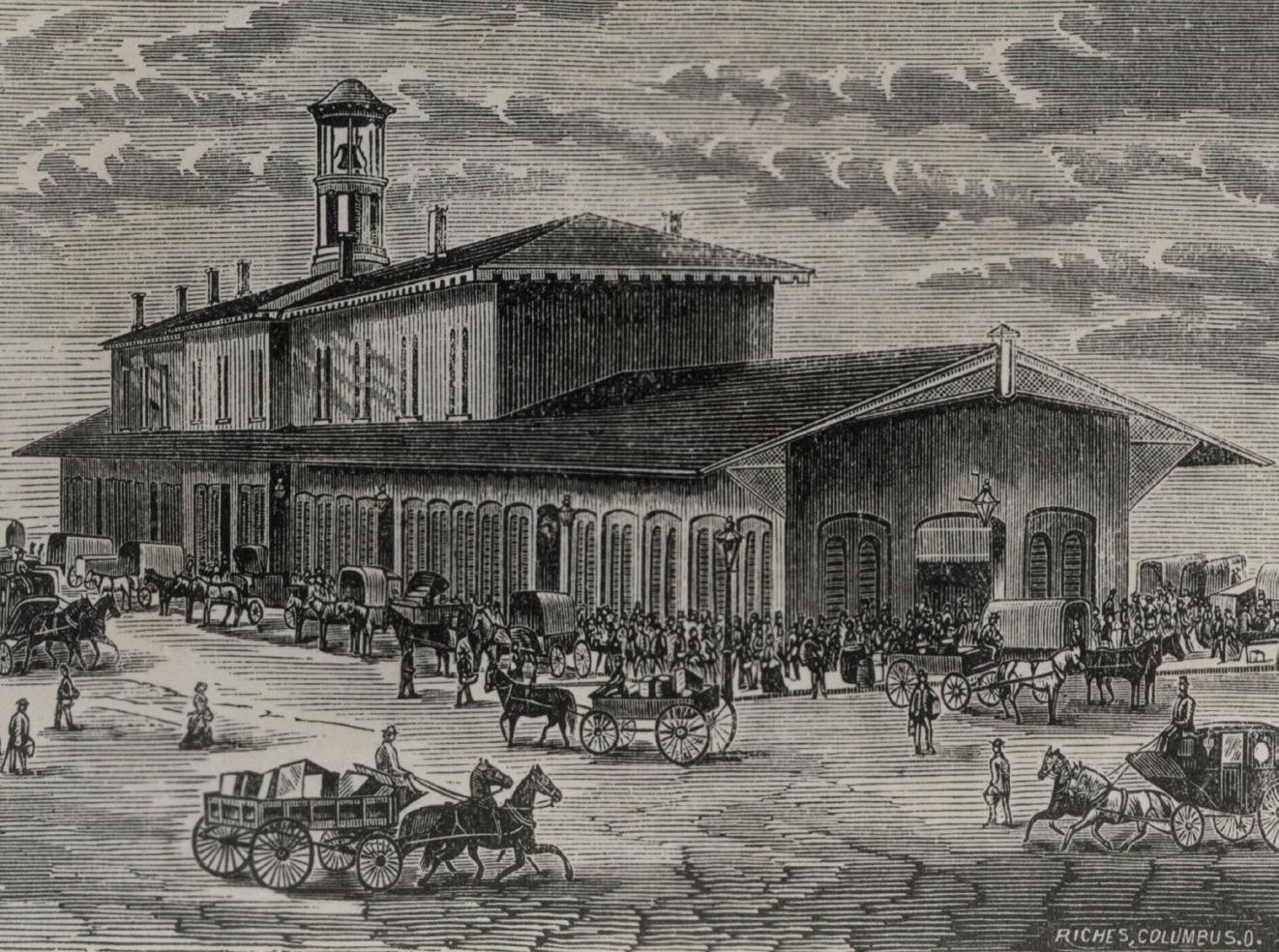

Historical sources are not specific about the location(s) of Columbus’ administration offices prior to 1850, noting only that its first permanent location was on the second floor of Central Market beginning that year. That was also the year that the railroad connected Columbus with Cleveland and Cincinnati, making Ohio a major player in the national economy. Population figures help tell the story: Columbus had just over 6,000 residents in 1840 and more than 51,000 by 1880.

Such growth soon caused the city to look for larger and better accommodations. A site fronting onto Capitol Square, Columbus’ primary urban design element, seemed only appropriate for such an up-and-coming place. Construction began in May 1869 and the new City Hall opened in March 1872. Reflecting tastes of the time — which eschewed the Greek Revival Style of the Ohio Statehouse — the building had a High Victorian Gothic design featuring pointed-arch window and door openings and numerous towers and turrets on all four sides of its stone exterior.

City Hall housed the various functions of municipal government but also had public gathering spaces that hosted meetings, galas, receptions, inaugural balls, and banquets. It even provided a venue for basketball practice, the activity taking place on January 21, 1921 when the building was found to be on fire. Despite valiant efforts by firefighters, the next morning revealed a smoking stone shell. The city weighed repairing the building, but its Gothic charms had apparently faded — even before the fire, it had been considered an aging eyesore. It was time for a new city hall, and a generous invitation from the main library to use their second floor gave the city time to think about what it wanted for its seat of government.

Top: FIGURE 1.1. Riches, William. Central Market. 1873. Engraving. In Columbus, Ohio, by Jacob Studer; last modified November 25, 2021.

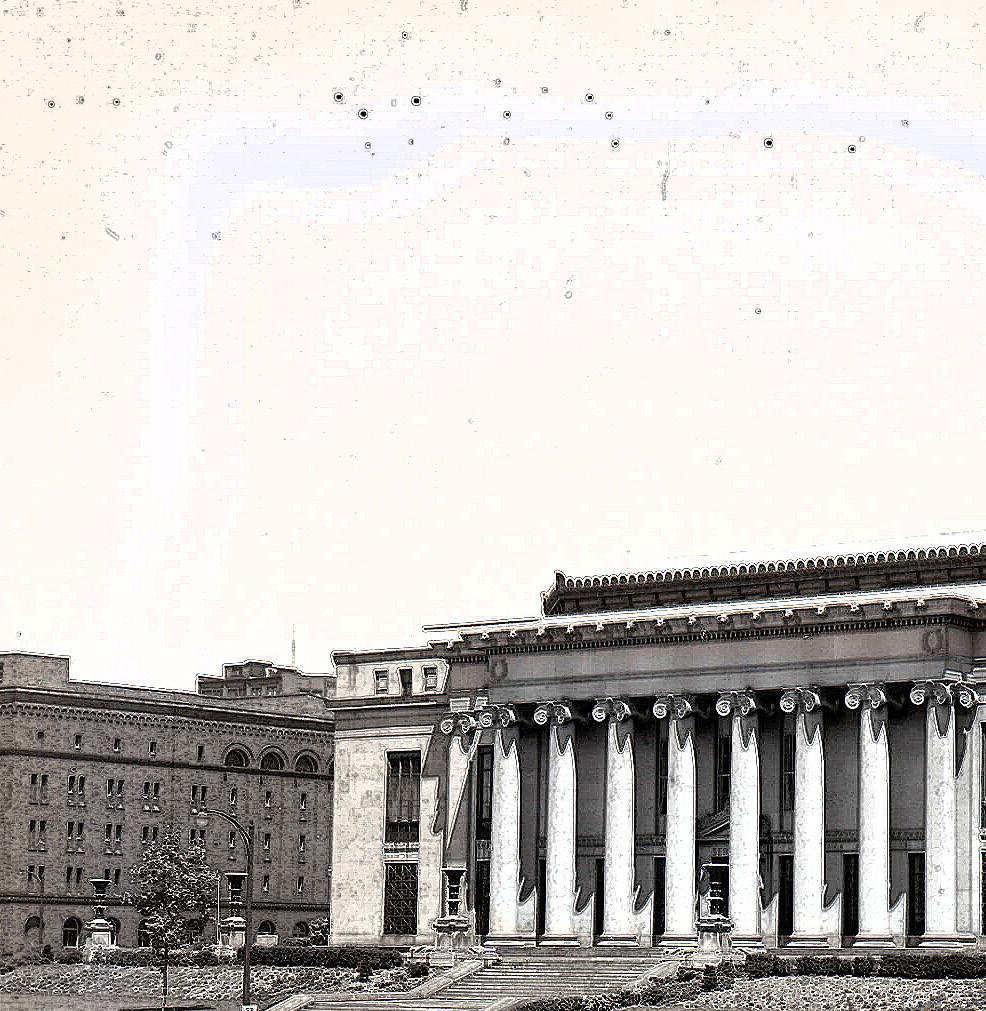

Bottom: FIGURE 1.2. “The City Hall, South Capitol Square,” in Centennial History of Columbus and Franklin County by S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1909; last modified November 25, 2021.

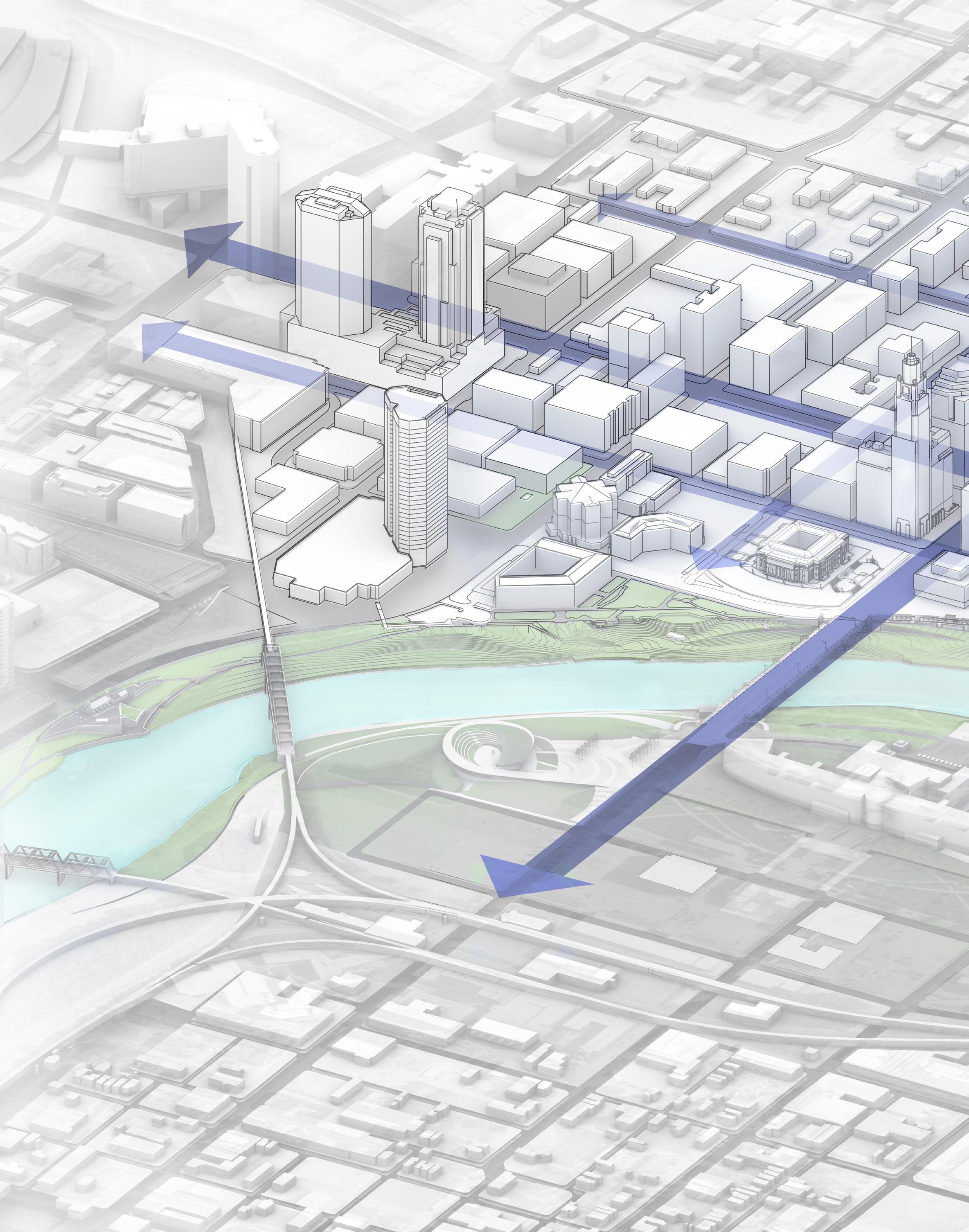

The benefits of rapid growth enjoyed by Columbus in the second half of the nineteenth century was accompanied by a number of ills — overcrowding, unplanned sprawl, shoddy construction, smog, and heavy traffic, particularly along its riverfront — that cities everywhere were experiencing at the time. Like planners in other cities, those in Columbus were inspired to address these ills by the City Beautiful movement that arose from the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893–94, a landmark global event that changed how people thought about urban development. City Beautiful adherents believed that well-designed cities could accommodate high density, if there was a proper balance among streets, public spaces, and new, classically-inspired architecture that inspired people to be engaged, caring citizens.

Taking its cue, Columbus began a modest planning effort with a grant of $350 from the Board of Trade to engage professional services to evaluate parks and other improvements. This was followed in 1906 by City Council’s appropriation of $5,000 to create a plan “to make a study of the streets, alleys, parks, boulevards, and public grounds of the City of Columbus, Ohio and suggest such extensions and additions thereto as may be necessary; and to make a report thereof for the purpose of promoting the future welfare of said city and beautifying the same.” The 1908 Report of the Plan Commission, Columbus Ohio , stated “the importance of Columbus as the capital city of one of the richest states, and as an educational center, especially invited and fully justified a comprehensive scheme of carefully designed improvements.”

Further:

“It is notable that the Centennial of the establishment of Columbus as the capitol [sic] of Ohio is at hand. In 1912, a hundred years will have passed since that event. Surely there could be no worthier celebration, appealing alike to State and city, than the realization of the vision of this city as the most beautiful and best ordered State capital of the Union."

The plan proposed a new Civic Center, calling for a complete remake of all the land west of Capitol Square between Broad and State Streets and across the river to the west bank:

“The Civic Center will be naturally placed...The design worked out for Columbus proposes an approach to the Capitol from the river — a Mall, which shall be a dignified green, ultimately to be adorned with sculpture...On the east side of the Capitol, there will be a square surrounded by public buildings, municipal and county, here grouped partly for convenience and partly to stand for the civic worth and pride of the municipality.”4

It addressed three elements — first, the State Capitol and its immediate grounds; second, an enlarged business center fronting a parkway or mall leading to the Scioto River; and third, a national and municipal administrative center with City Hall, a future government building, other state buildings, an art gallery, and a music hall.5

Alas, it was not to be. Apparently political and business interests in Columbus did not share the planners' dreams.

As it turned out, Mother Nature forced the issue. The devastating flood of March 23–27, 1913 was the city’s worst natural disaster. Statewide, more than 450 people perished in the flood, and 40,000 homes were destroyed. In Columbus, the entire west side was underwater, leaving 93 dead; all the downtown river bridges failed, and 500 buildings were destroyed. Much of downtown Columbus, however, was spared due to its elevation above the river. The city immediately began to plan flood-proofing efforts that included widening the river channel, constructing upriver dams, and removing buildings along the banks.

It is likely that memories of the 1908 Civic Center plan, along with those flood-control efforts, revived the idea of creating a civic center, this time with a north–south orientation along the Scioto River. A new commission led by renowned Columbus architect Frank Packard took on the task of developing a design. With so much existing riverside development destroyed, it was logical to use the river’s east and west banks as the sites of new public buildings.

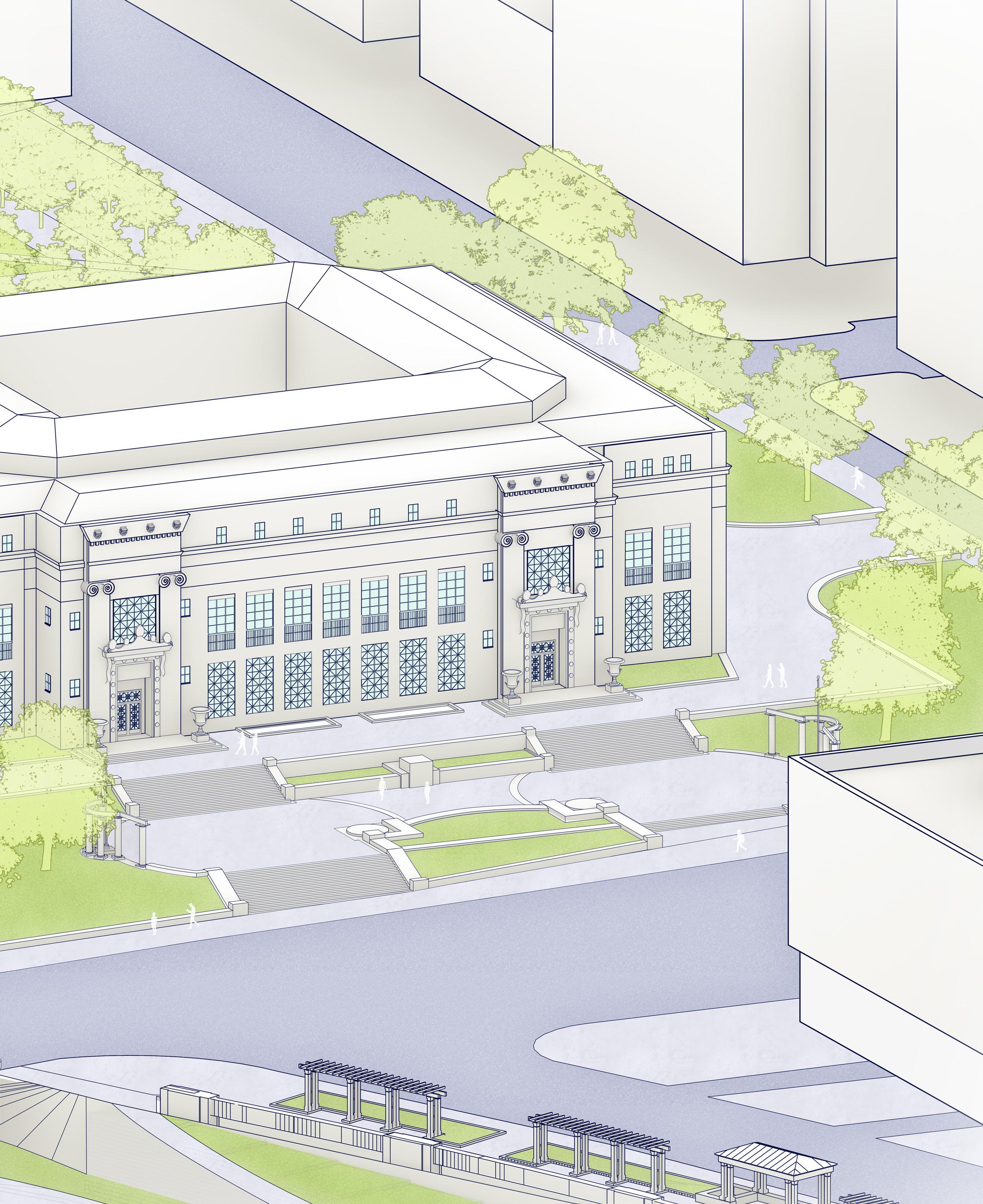

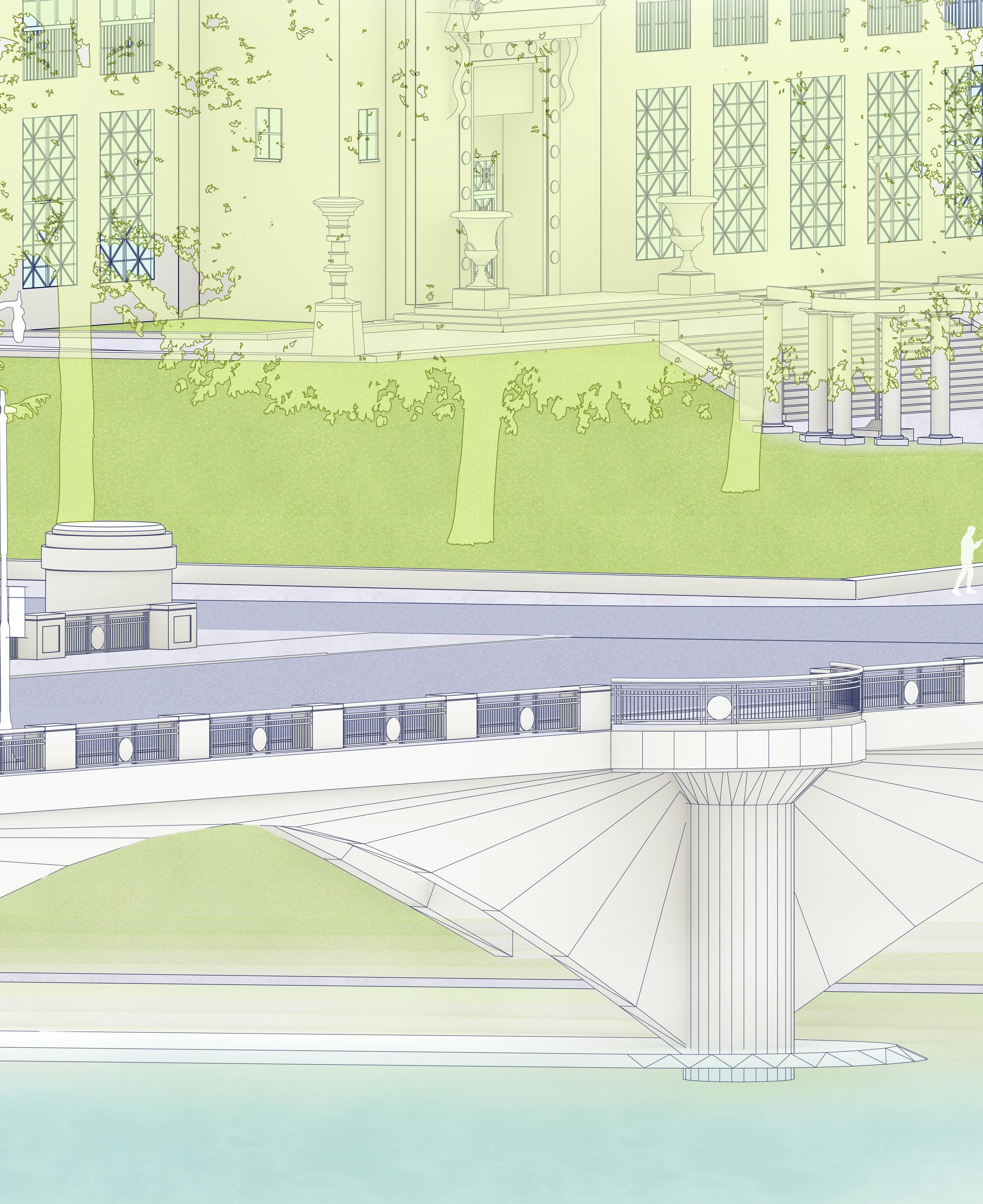

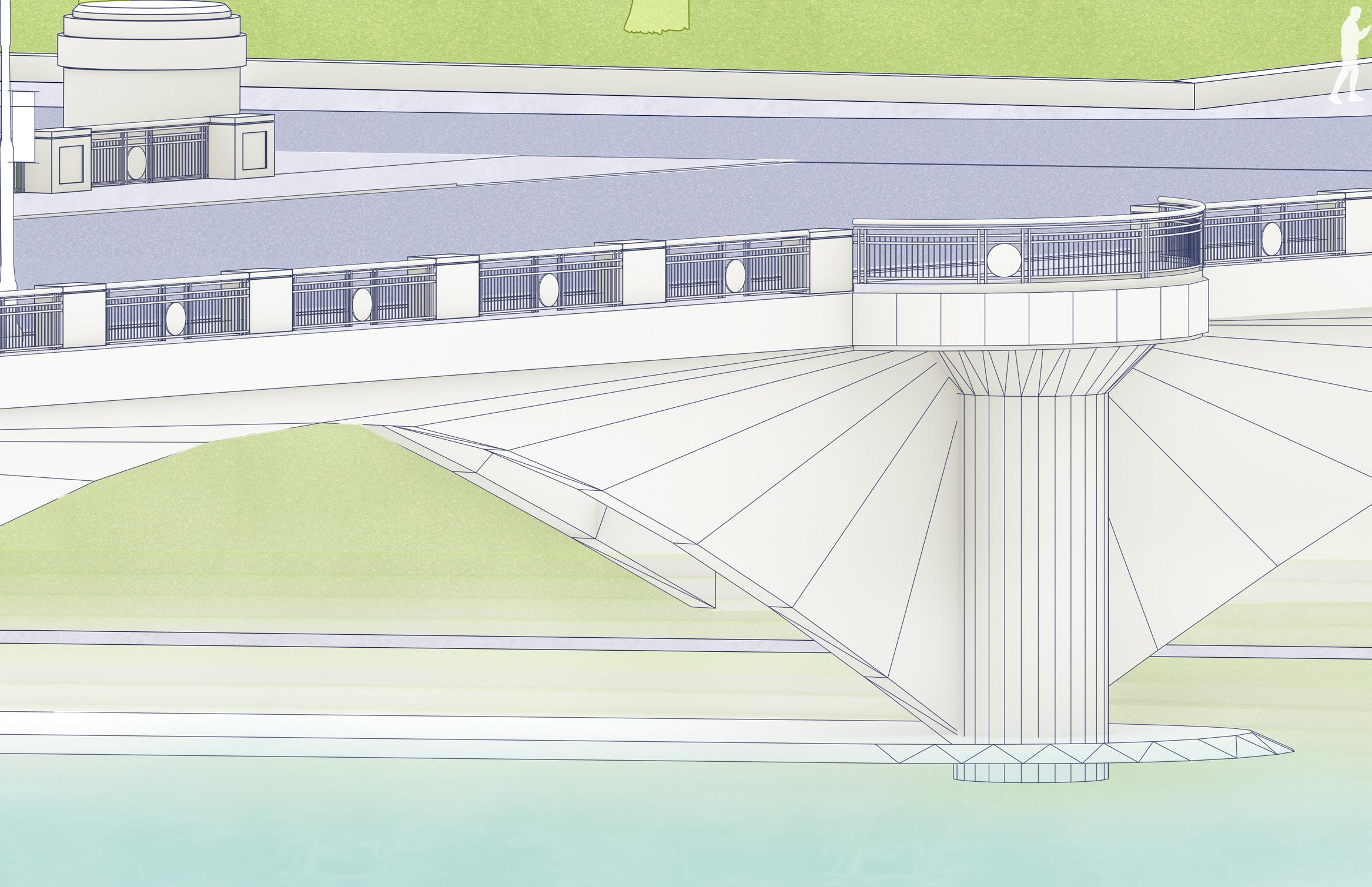

On the north end of the east bank was the (now-demolished) Ohio Penitentiary, a grim place but one with a compelling architectural presence. The 1861 Ohio State Arsenal stood at the south end of the river’s crescent. In between these anchors, a significant collection of public architecture would grow, as much of what Packard’s commission proposed manifested. City Hall was built on the river's east side in 1928, then the Columbus Police Headquarters (1929); the Ohio Departments Building (1933); and the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse (1934). The new Town Street (1917), Broad Street (1921), and Main Street (1935) bridges were concrete arches — unique, yet complementary in their designs, and intended to forge a permanent linkage of the east and west banks. Less development was proposed for the west bank; indeed, there arose only Central High School in 1922. The entire composition extended from Neil Avenue on the north to Main Street on the south.

An artificially elevated site protected Central High School, and a high retaining wall with a balustrade, completed in 1918, protected the east bank. Ground level in this area was filled, raising the east bank building sites and lessening the change in grade from High Street. A new street, Civic Center Drive, connected West Broad and West Main Streets.

Above: FIGURE 1.3. Howe, Henry. Ohio Penitentiary and Scioto River. 1856. Engraving. In Goodale Park Centennial, 1851–1951, published by Columbus Division of Parks & Forestry, 1951; last modified January 5, 2022.

Right: FIGURE 1.4. “Ohio State Arsenal.” 1861-1870; last modified January 5, 2022.

Upon widening the riverfront and adding dams, new development, including a new city hall, could proceed. The city's challenge now was to determine who would design a new city hall building. In November 1922, City Council authorized the Director of Public Service to consult with the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) for advice about the “best and cheapest method, consistent with proper standards to be pursued by the city in procuring architectural services for the construction of a new city hall.” 6 In response, a committee of Columbus AIA chapter members and City Council members outlined three possible methods of architect selection, including direct selection, a competitive process, or the creation of a city department to handle the project and others like it.7 City Council considered the pluses and minuses of all three and then rejected them, suggesting that the local AIA chapter instead work together to complete the project.” 8

The AIA chapter took the challenge and noted that Los Angeles had created an “Allied Association of Los Angeles” in a similar situation. They decided to form such an organization in Columbus — The Allied Architects Association (AAA) of Columbus. AAA was structured with the intention of bringing the best designers into the project, building on Los Angeles’ approach. The organization was a legal entity under Ohio law with a maximum of 25 members. It was open to all Columbus AIA members and those qualified to become members, and had capital stock of $5,000 to be raised from members by a $200 subscription. Their stated purpose was:

“...to provide, by professional cooperation and collaboration, architectural services for the design and construction of a City Hall for Columbus, Ohio and for such other public buildings or improvements in Columbus and Franklin County which because of their civic importance seem to merit the efforts of a group of architects in such a manner as to advance the art of architecture and to contribute to the public good.” 9

Association members included Howard Dwight Smith, a prominent local architect and designer of Ohio Stadium; W. J. Richards, J.E. McCarty and George Bulford, designers of the Ohio School for the Deaf, Lazarus Store, and U. S. Post Office and Courthouse; Robert R. Reeves; Charles St. John Chubb, head of The Ohio State University's Department of Architecture; and Ray Sims, who had a large practice in designing residential buildings.

There was an internal competition among association members for the position of chairman of a Committee on Design. The first stage of the competition called for small-scale pencil drawings showing possible relationships for multiple buildings in the civic center and a general style of exterior design; the second stage involved just three designers, who developed larger-scale drawings of the city hall building only.

The jury was chaired by Professor Charles St. John Chubb and included Harvey Wiley Corbett (New York) and Howard Van Doren Shaw (Chicago). The winner was responsible for overseeing the preparation of contract drawings, working drawings, and scale and full-size models. The competition was handled entirely within the Allied Architects Association, with no input from city officials; City Council was presented with their final design. No record of which Association member won the competition has been found.10

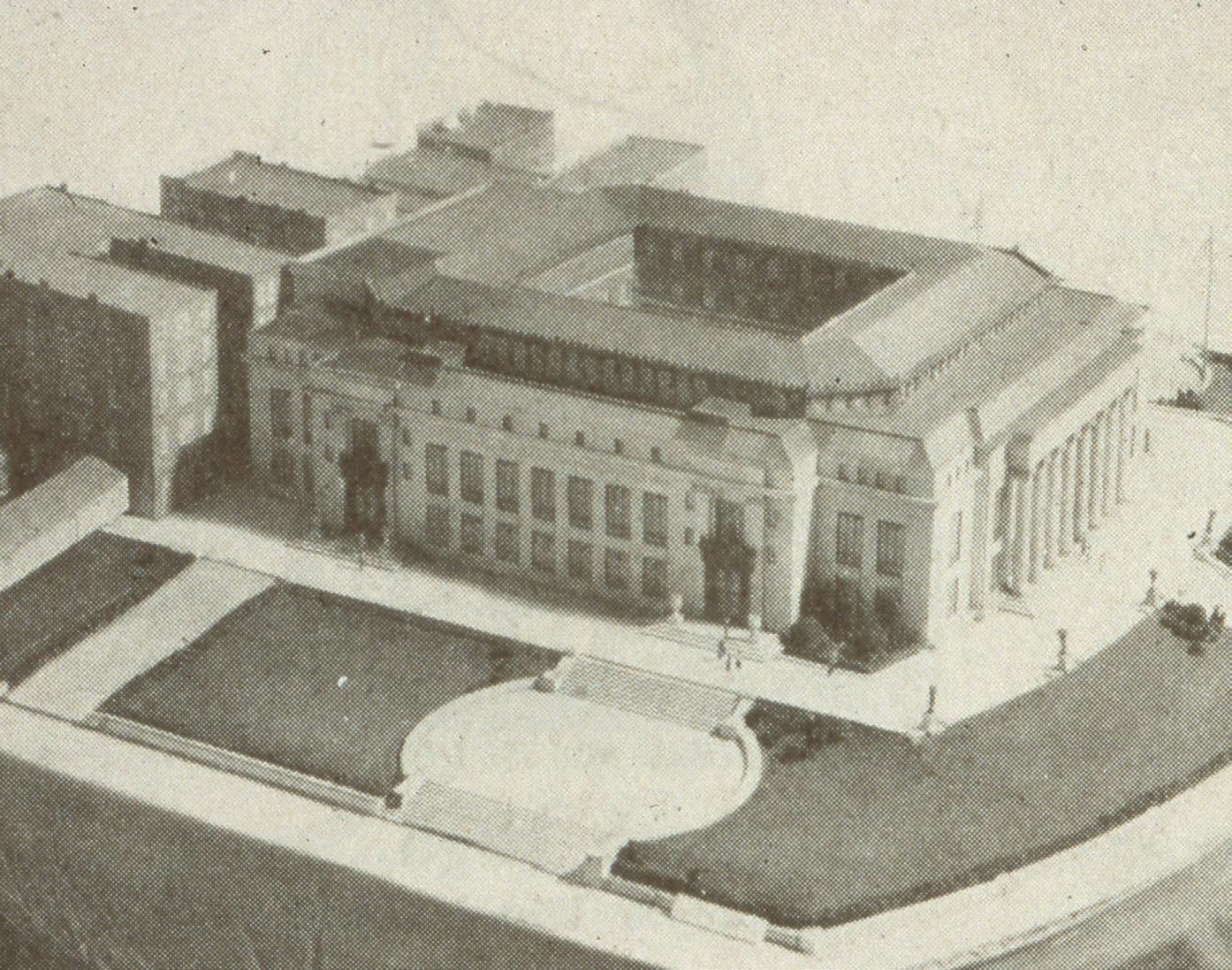

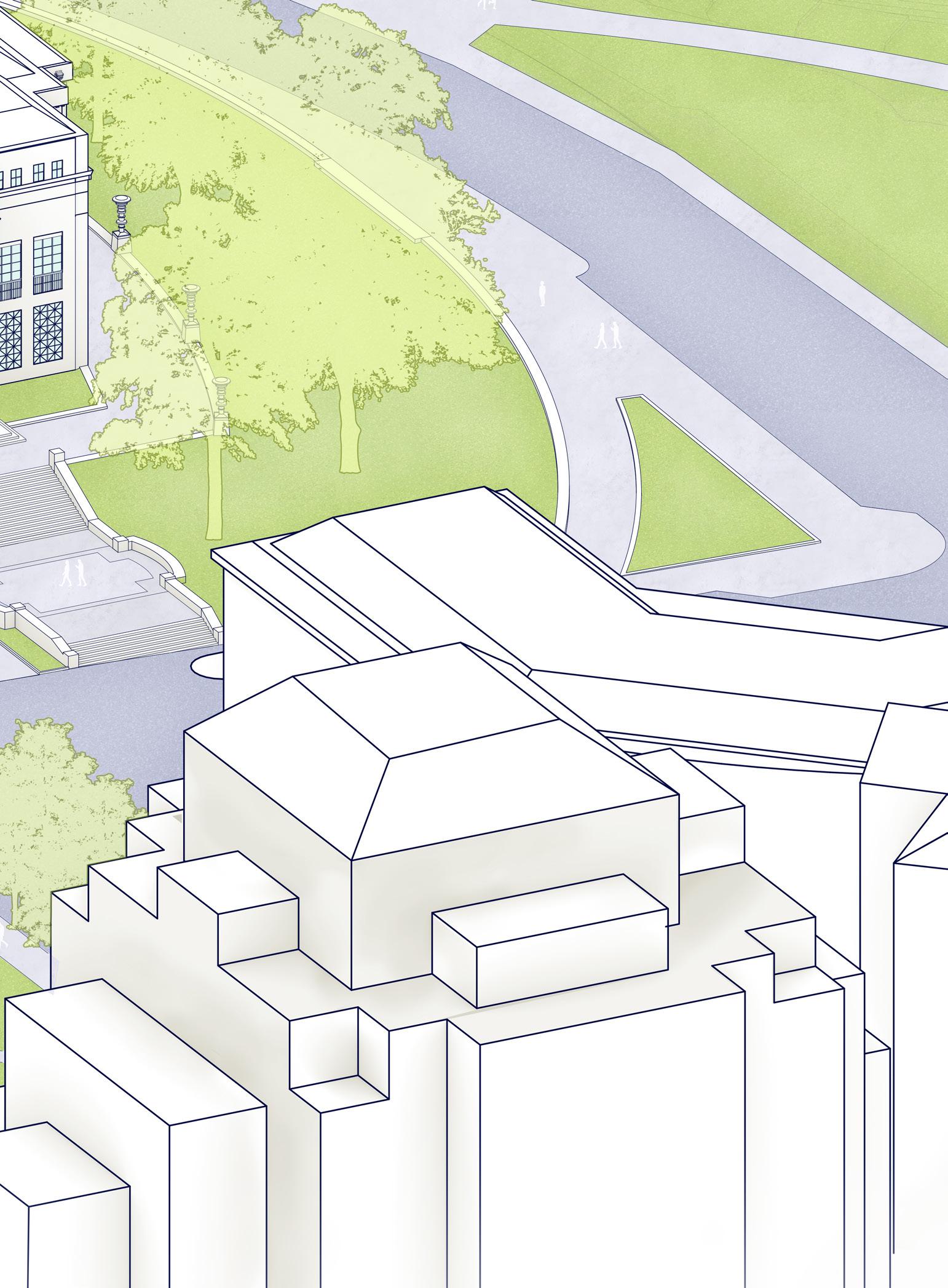

FIGURE 1.5. This view of the model of City Hall looks south at its north elevation. At this time the city had not acquired the entire site. A row of 19th century buildings lined Front Street, making it impossible to build the east elevation. When these properties were acquired, the east wing was built as designed, resulting in a symmetrical composition centered on the landscaped site. The river-facing colonnade and monumental steps (now removed) are on the right side of the model. Photo by Dean Rager (1926); last modified December 23, 2021.

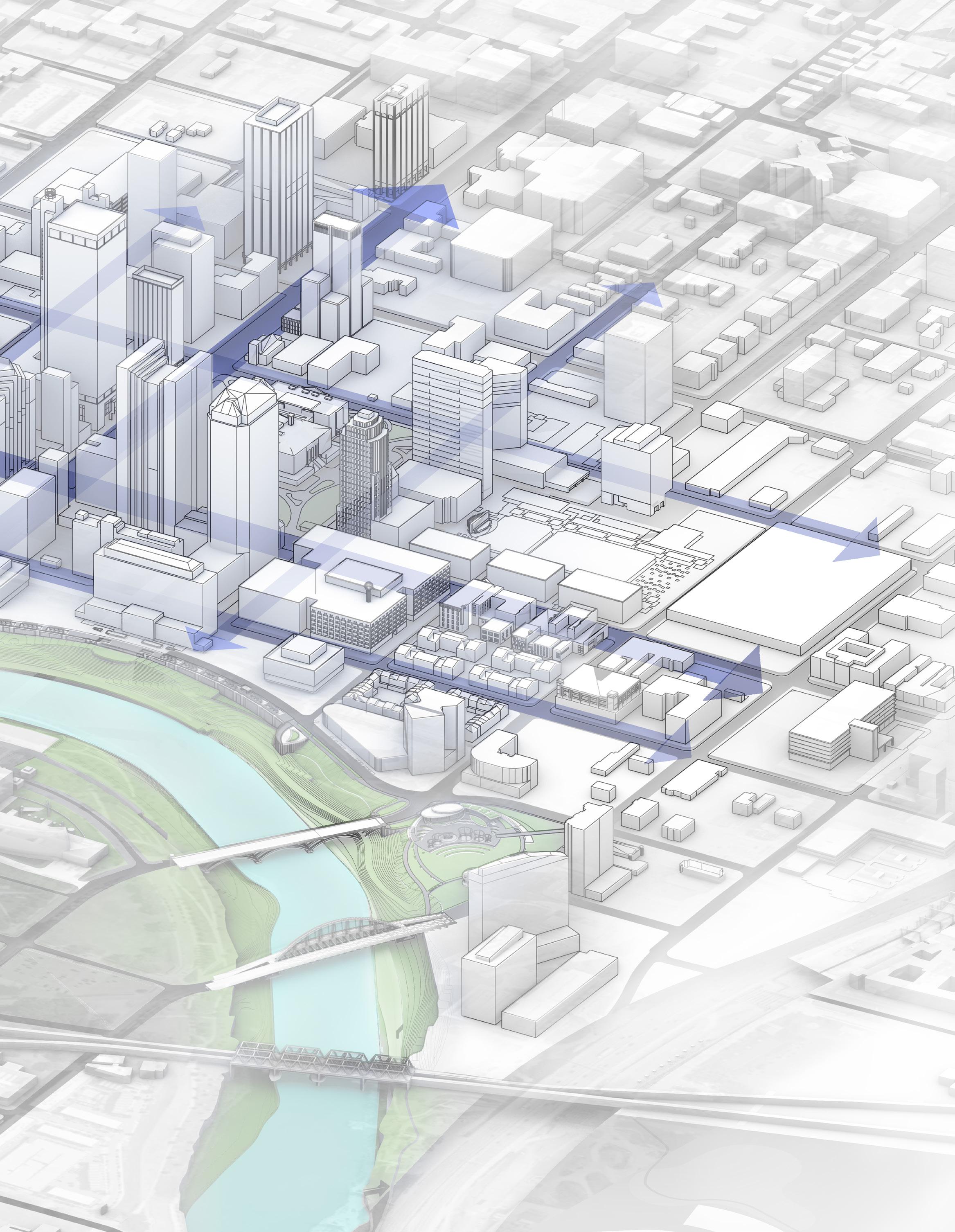

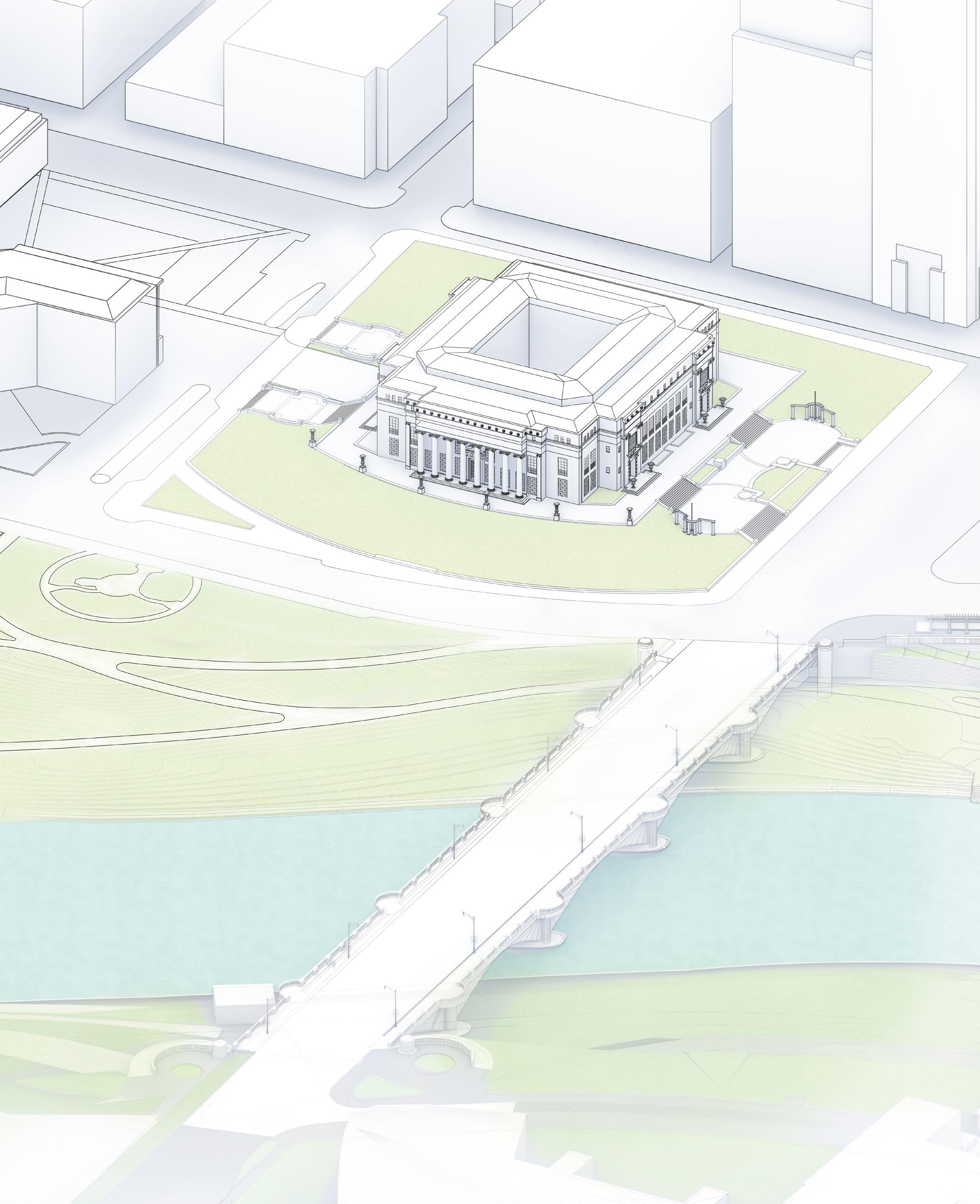

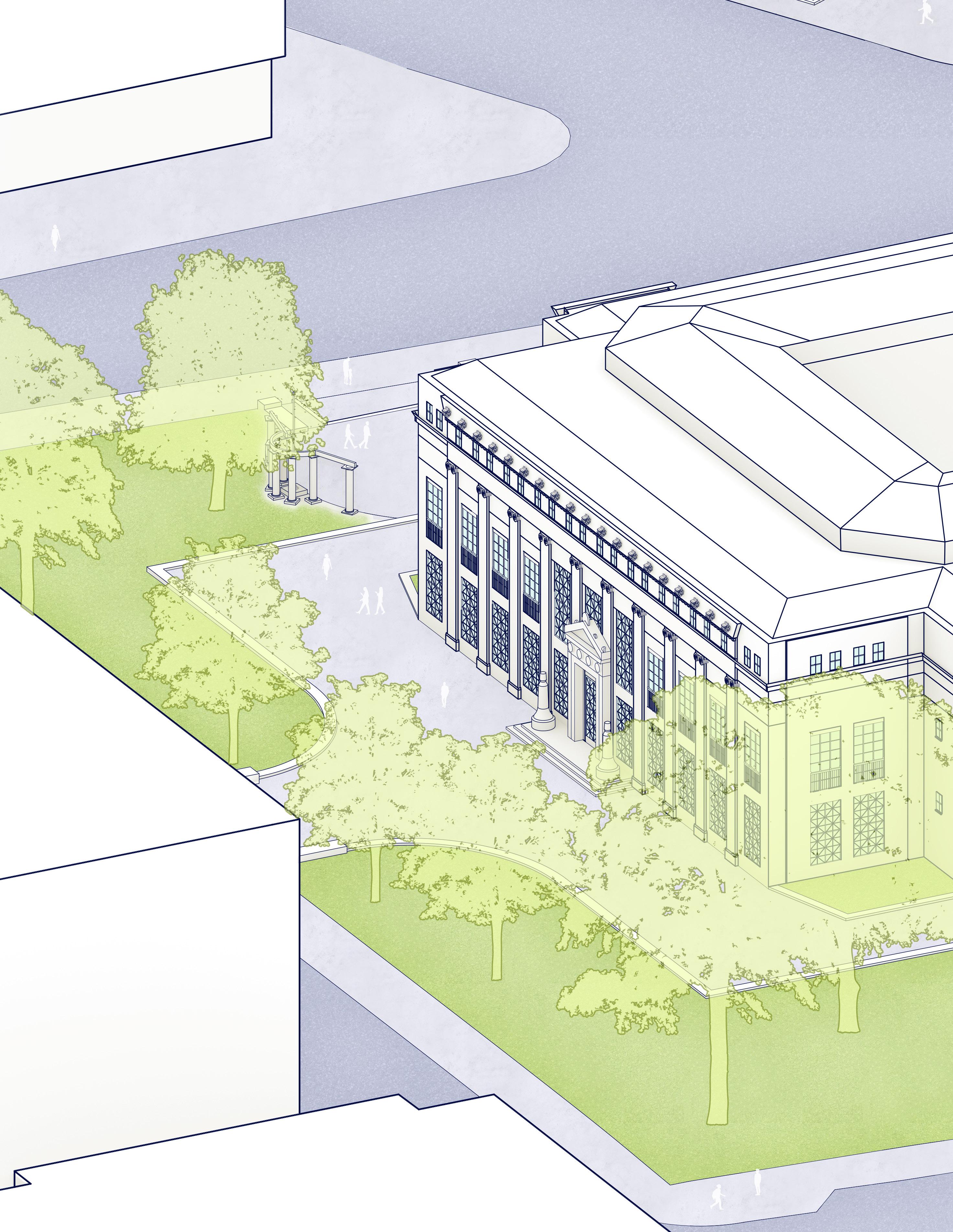

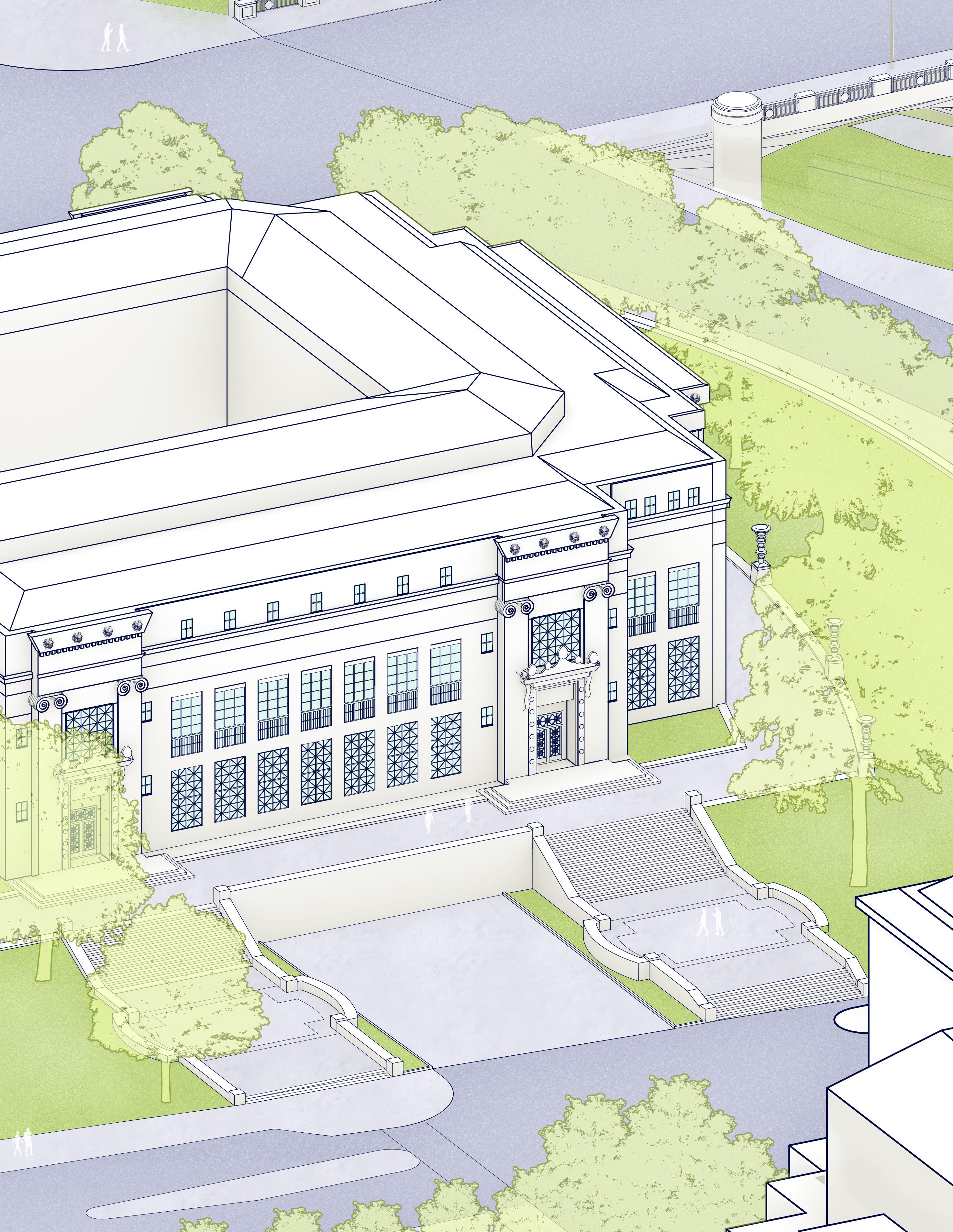

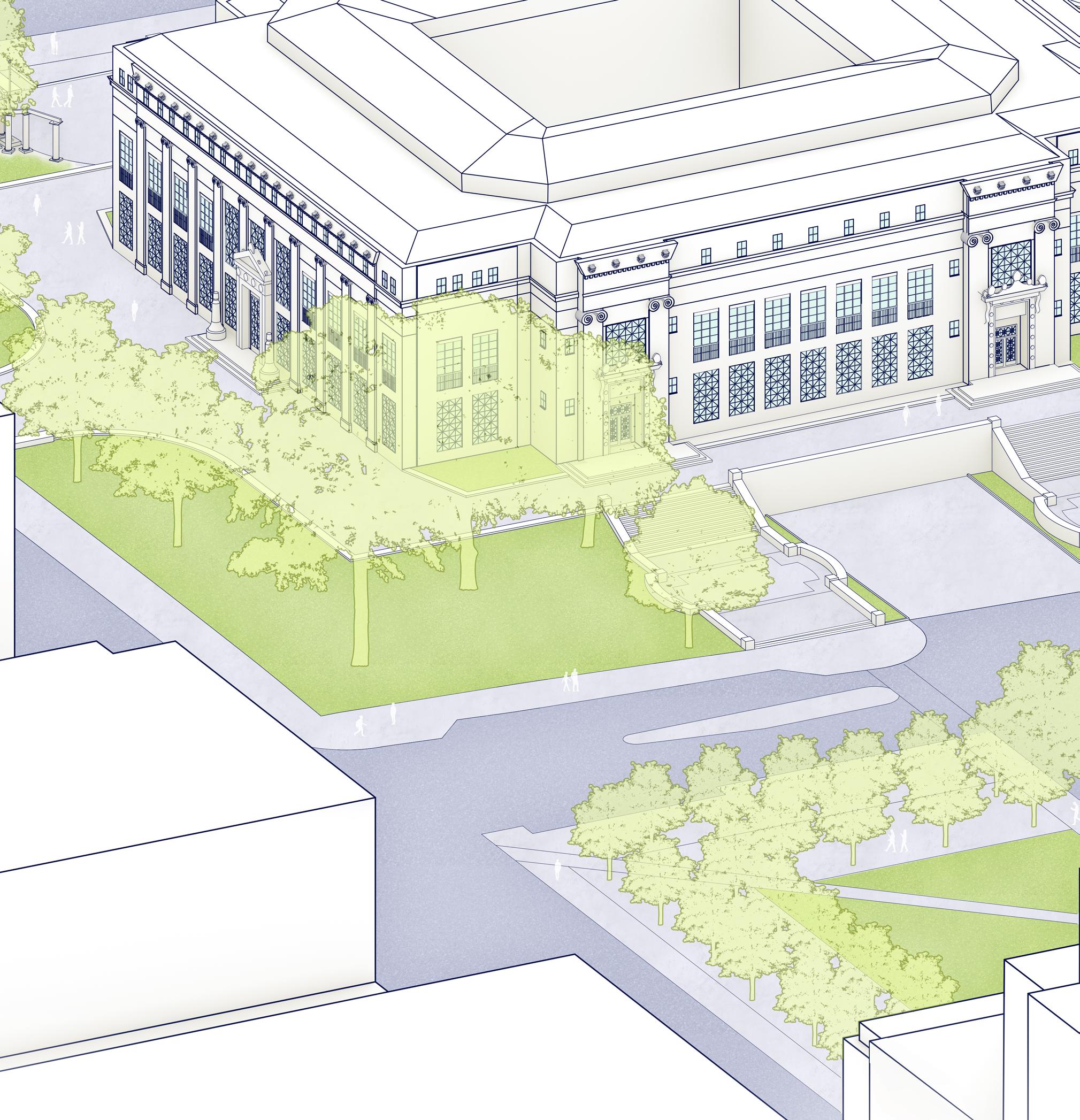

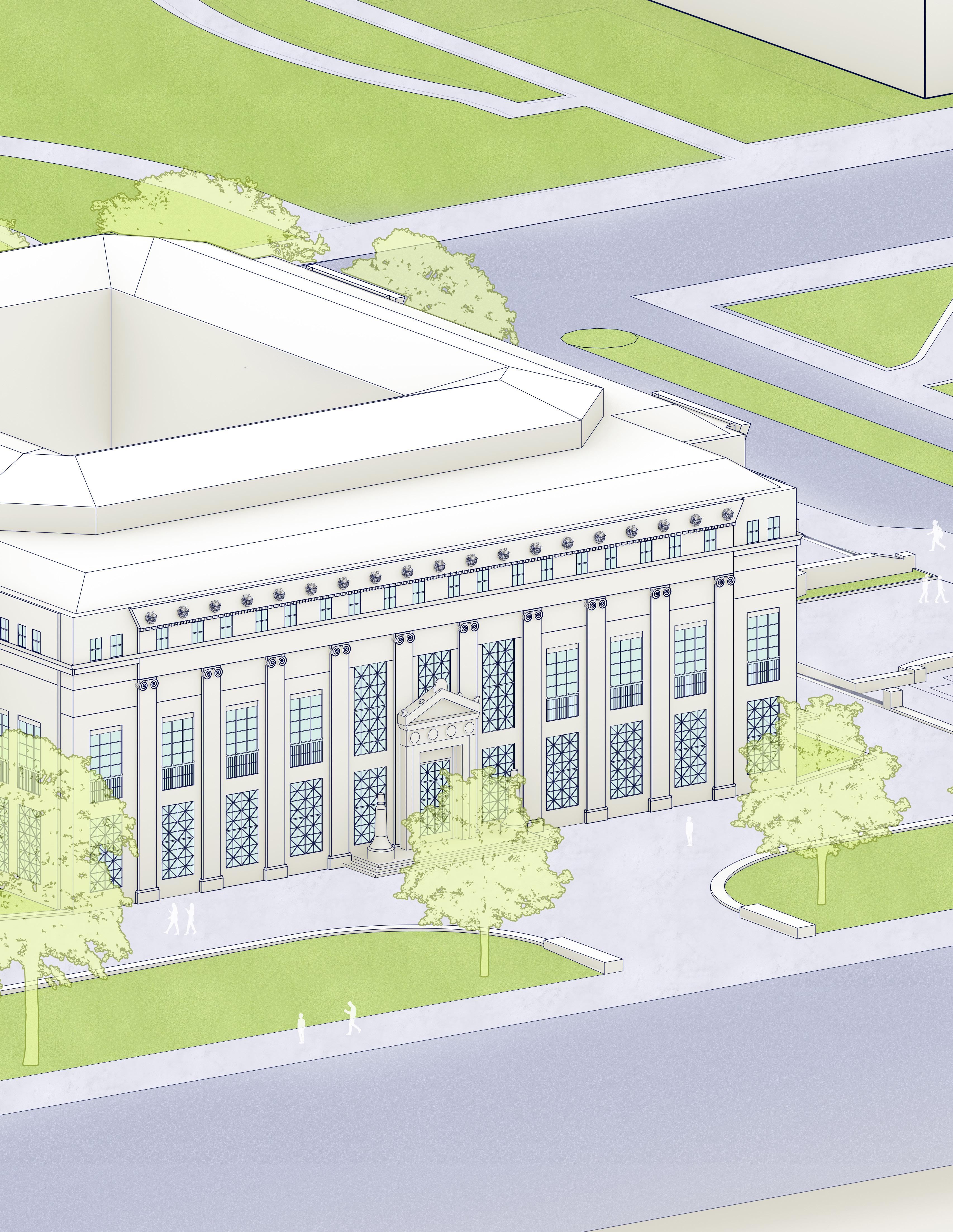

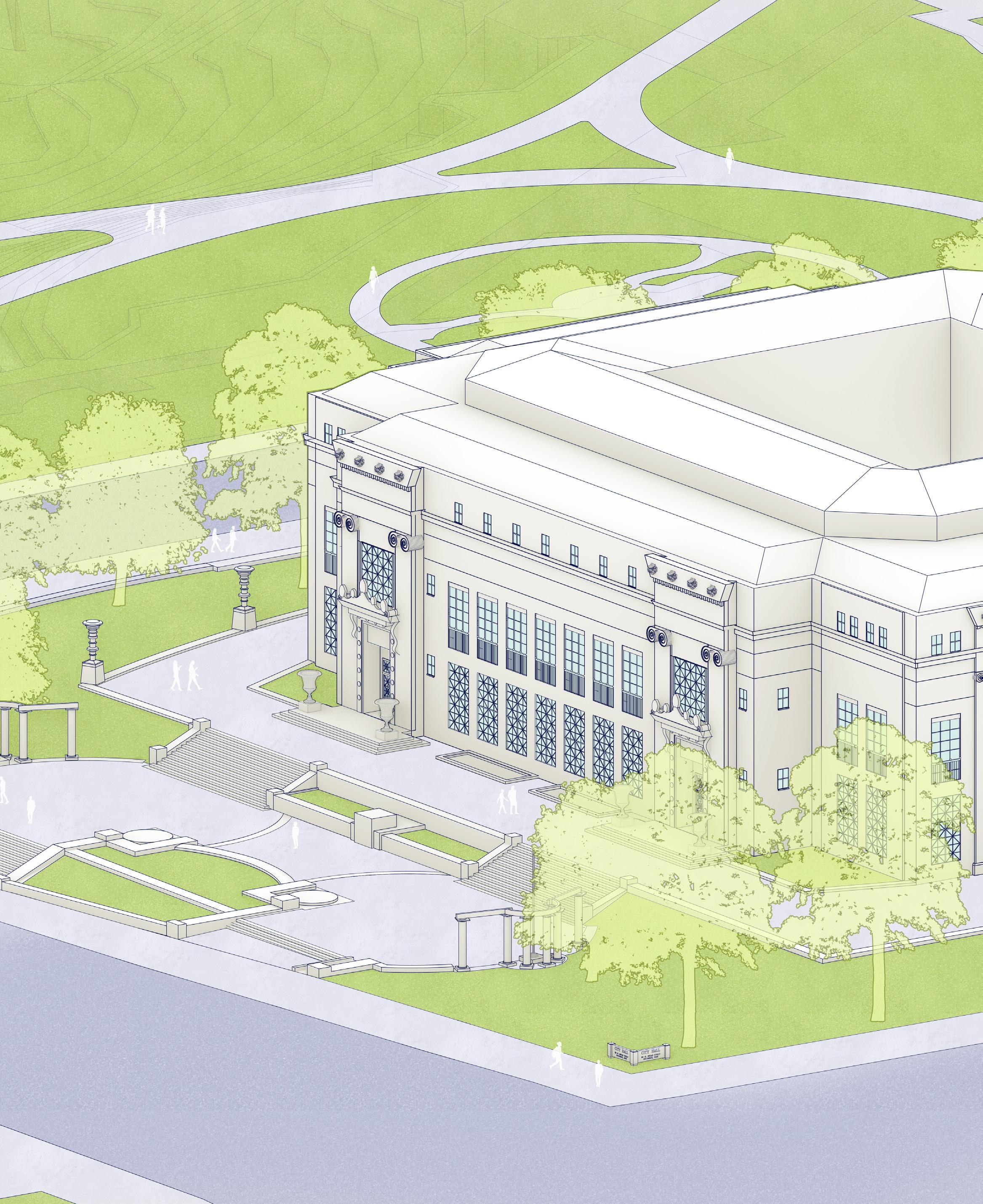

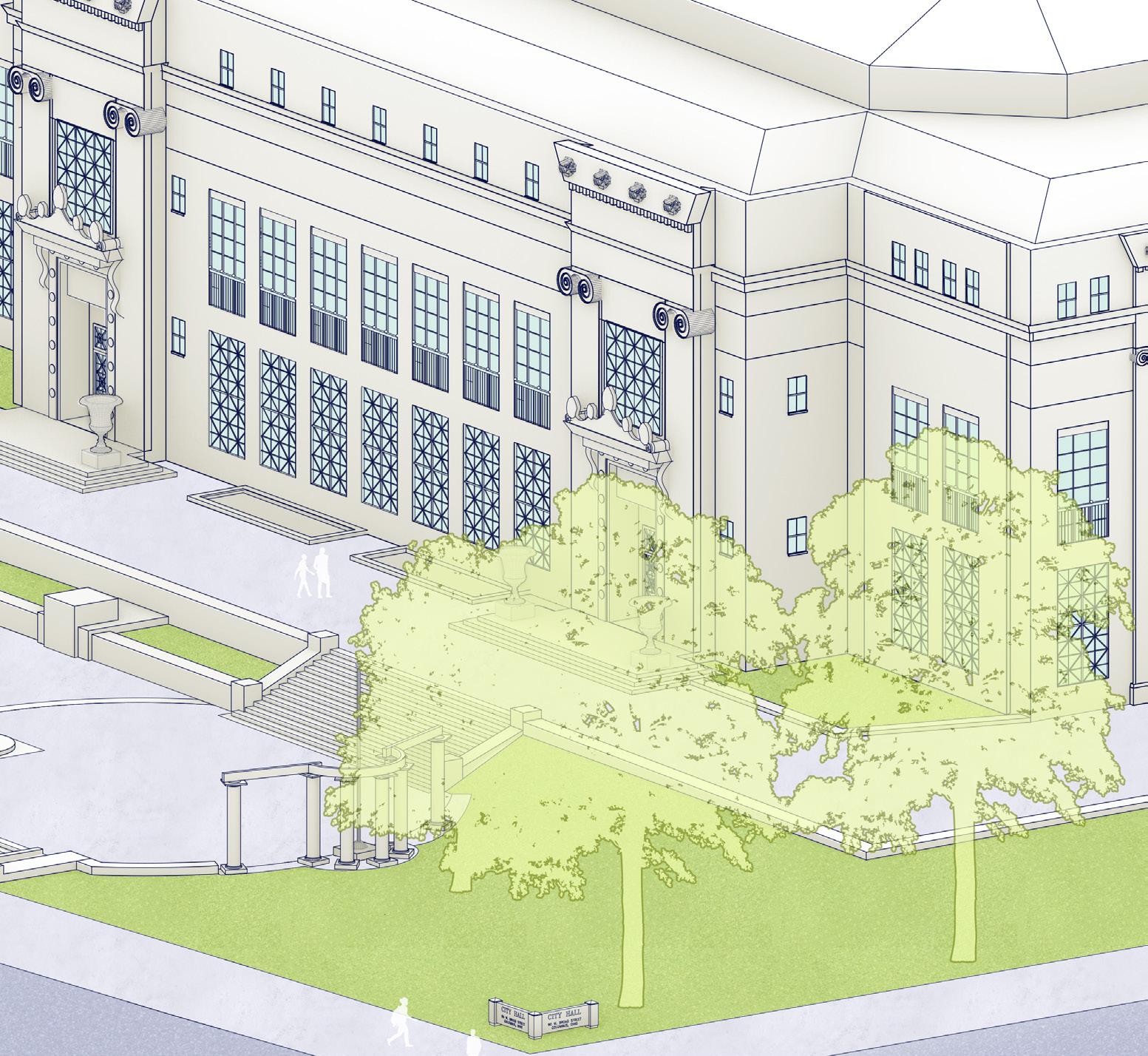

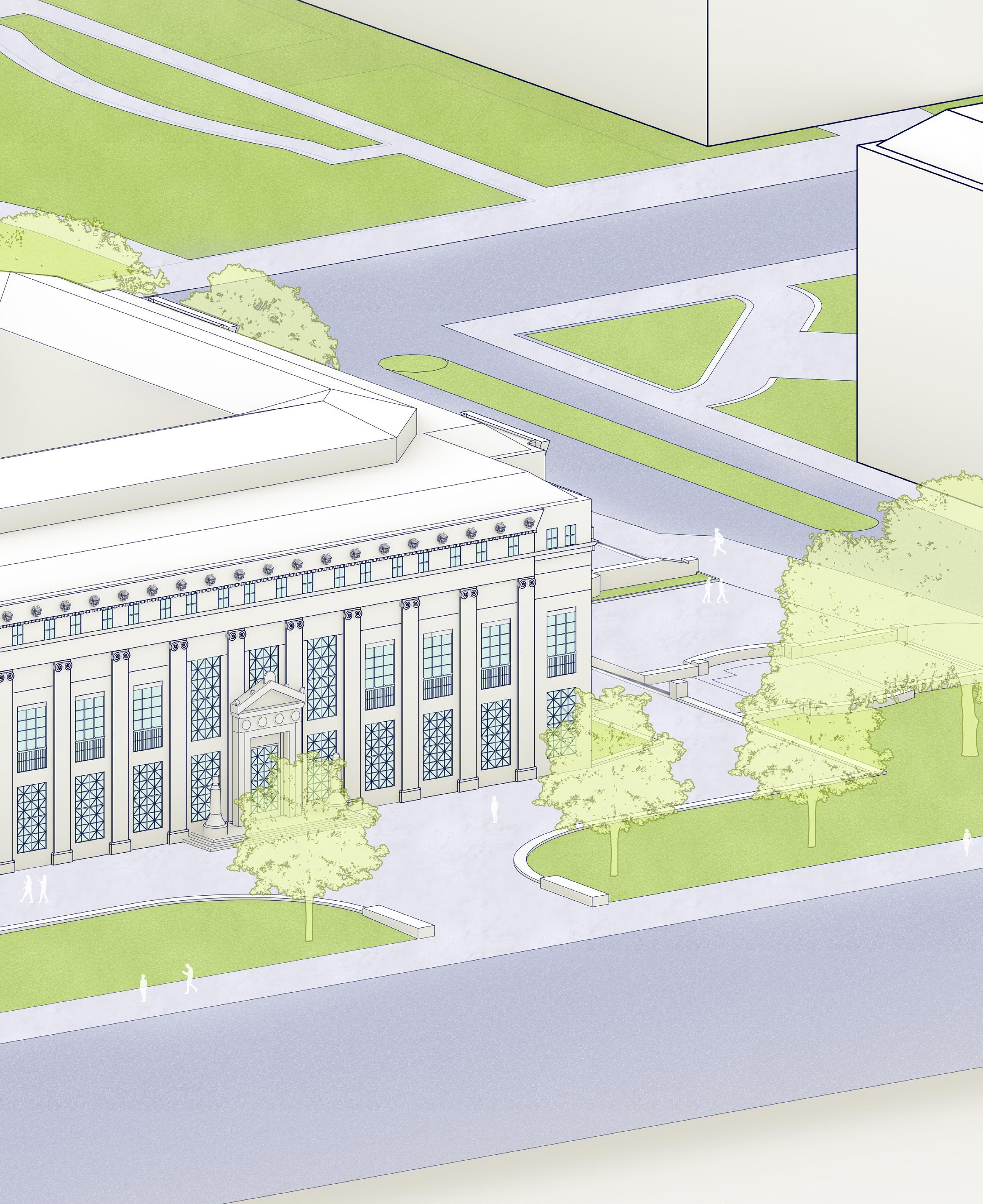

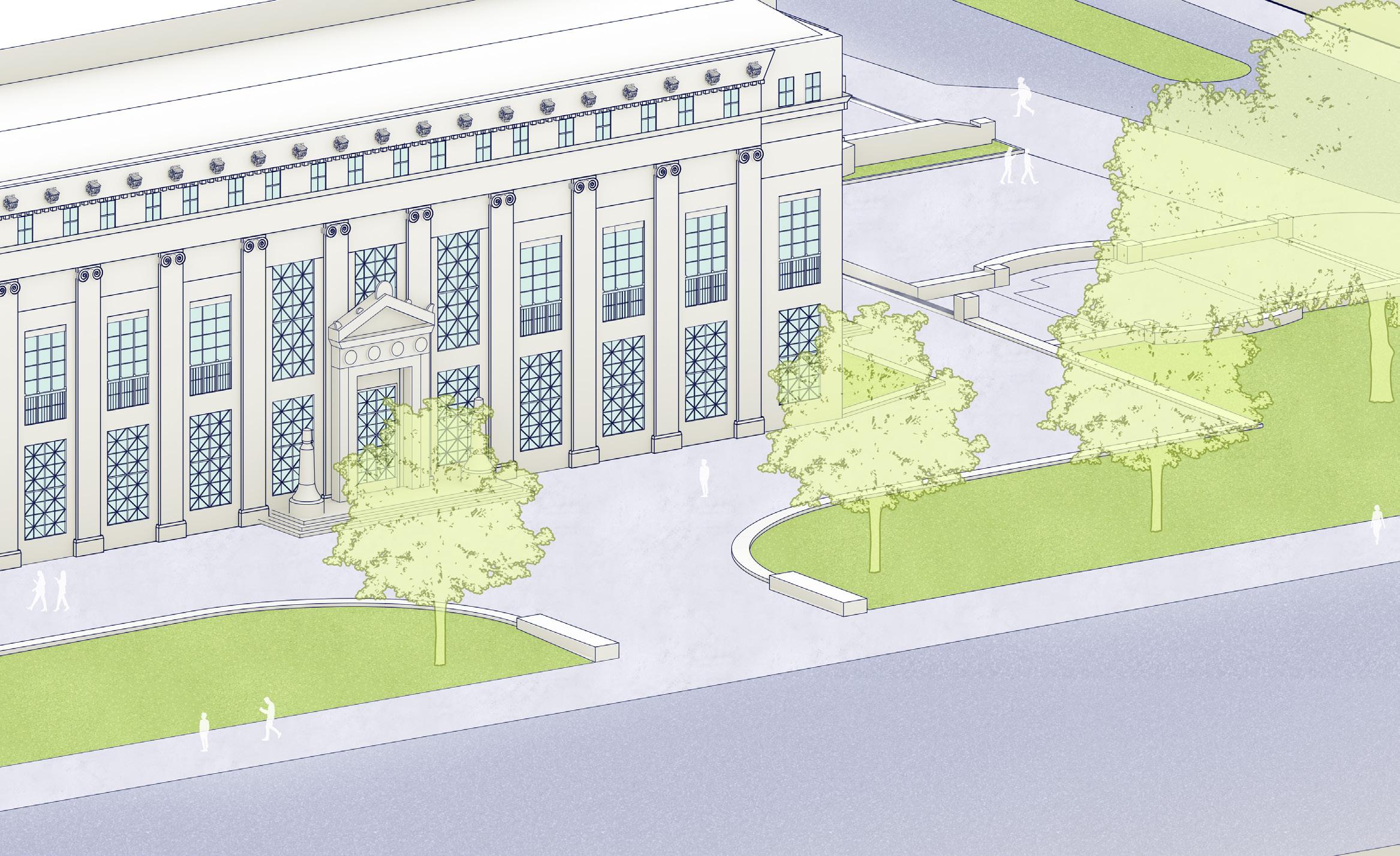

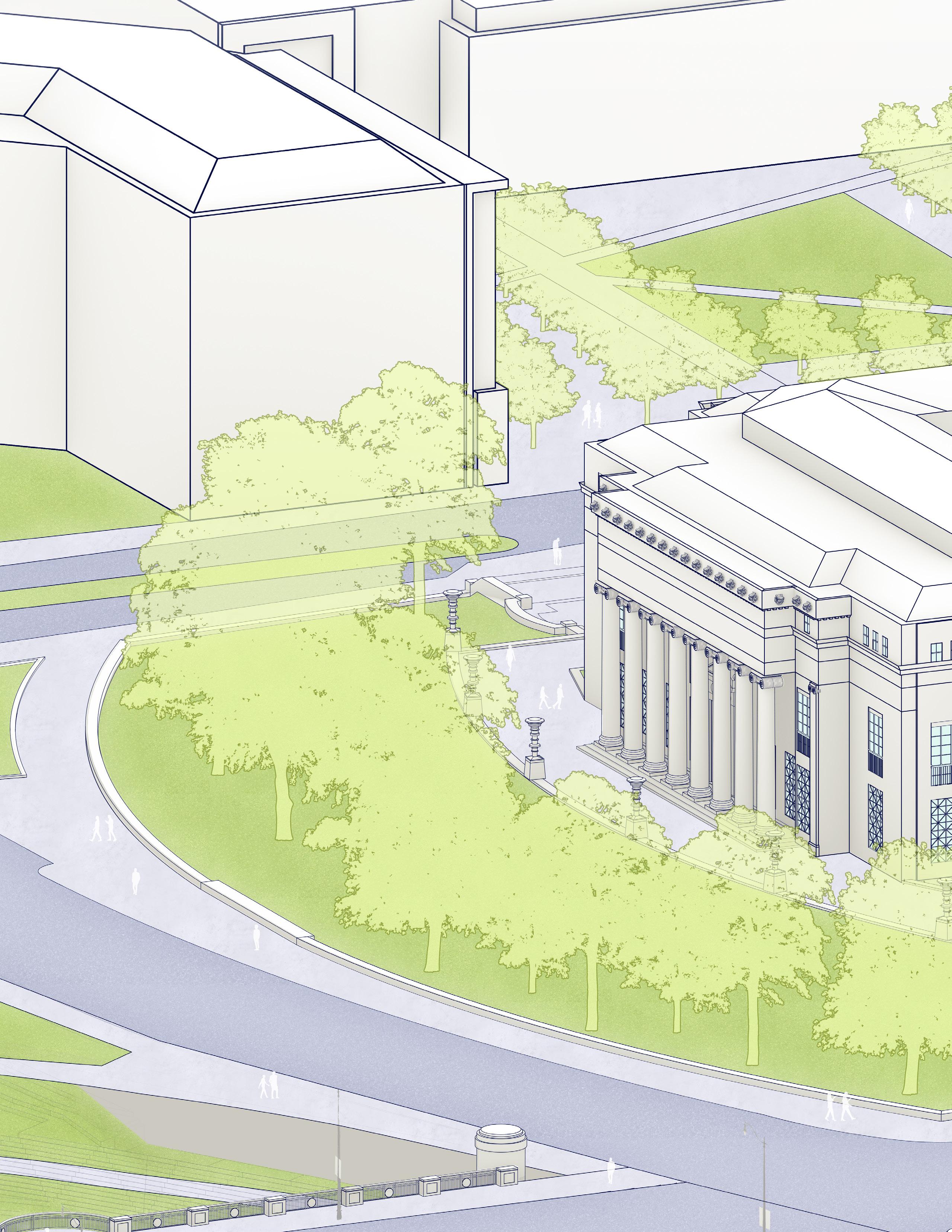

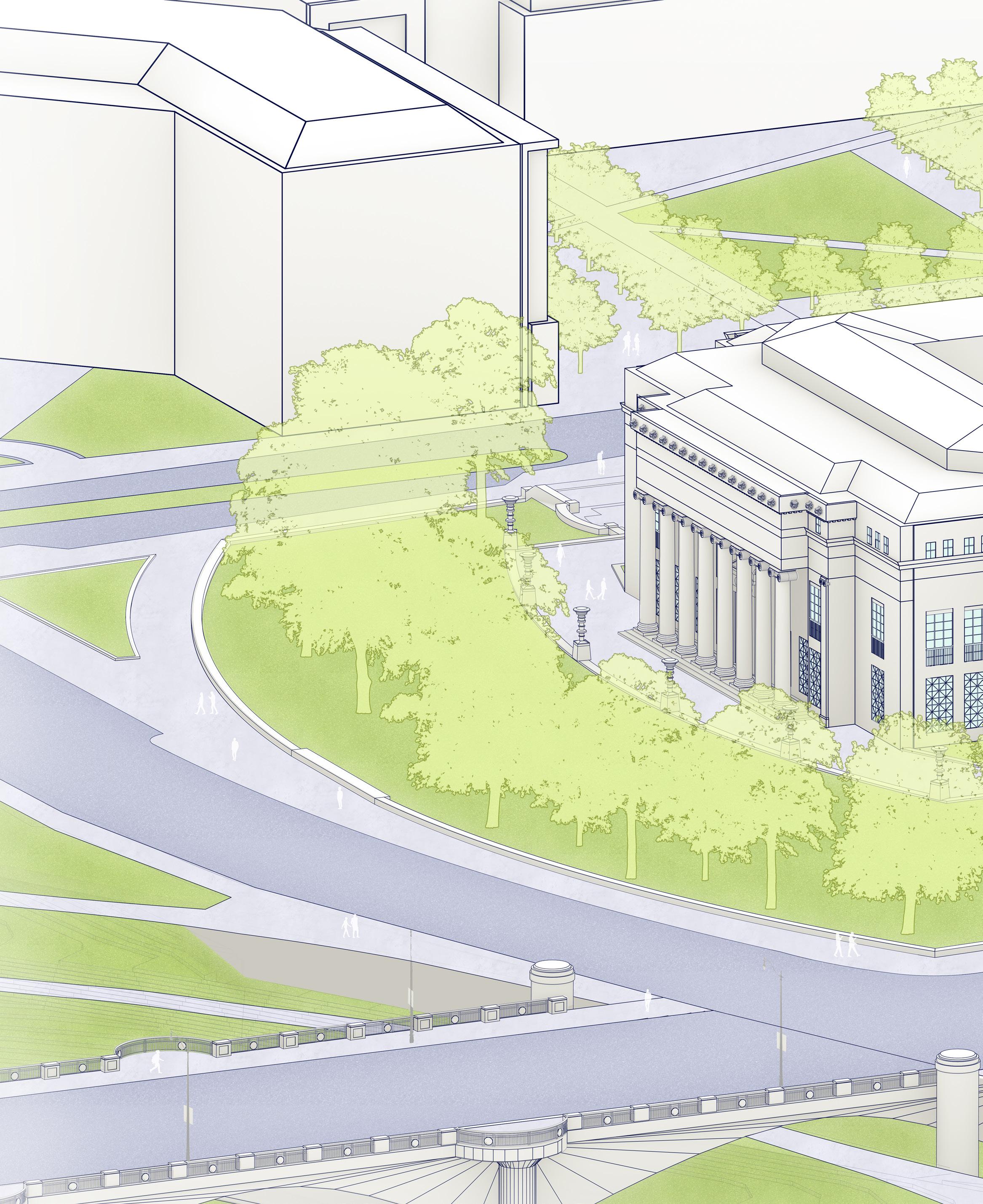

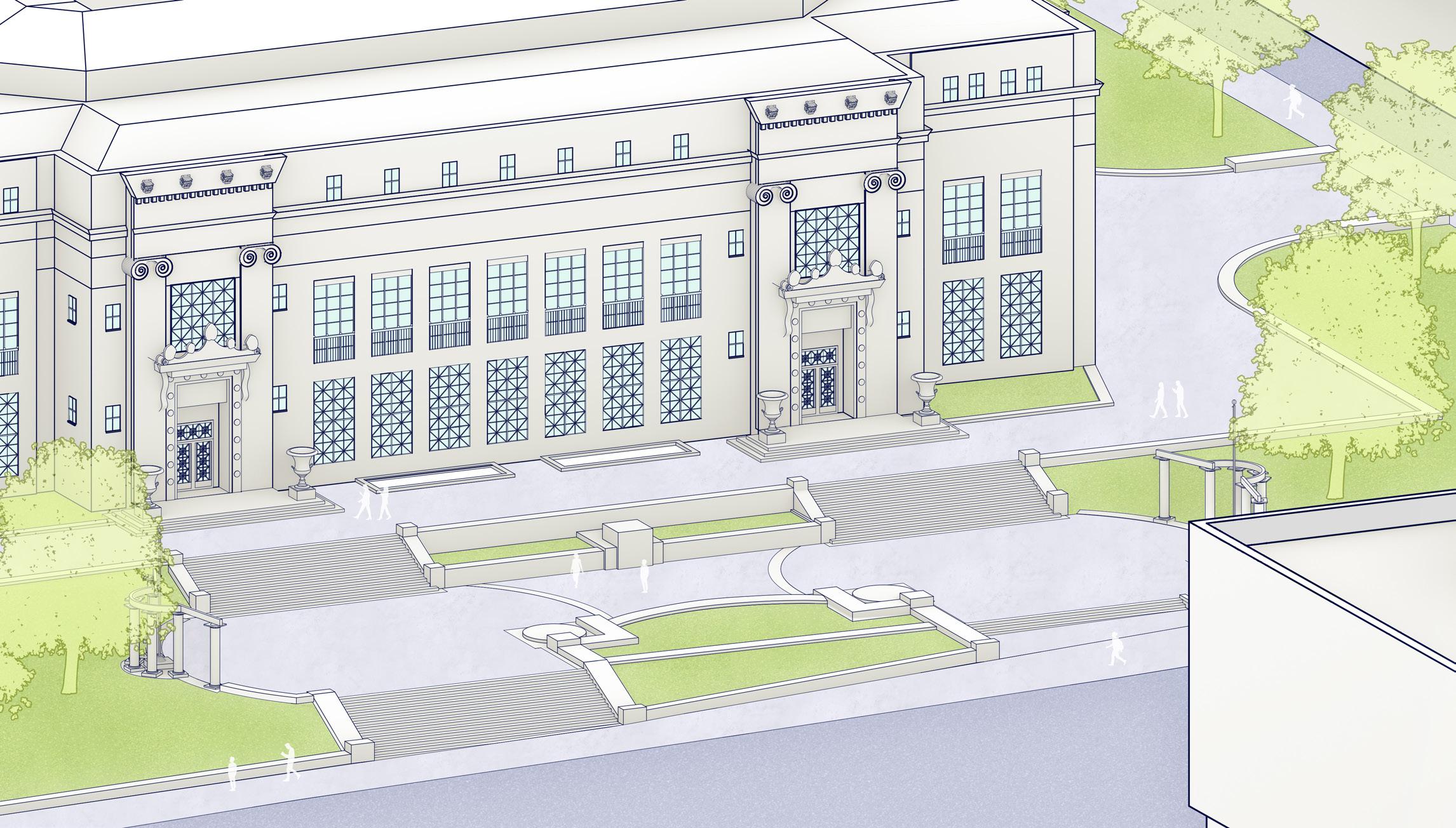

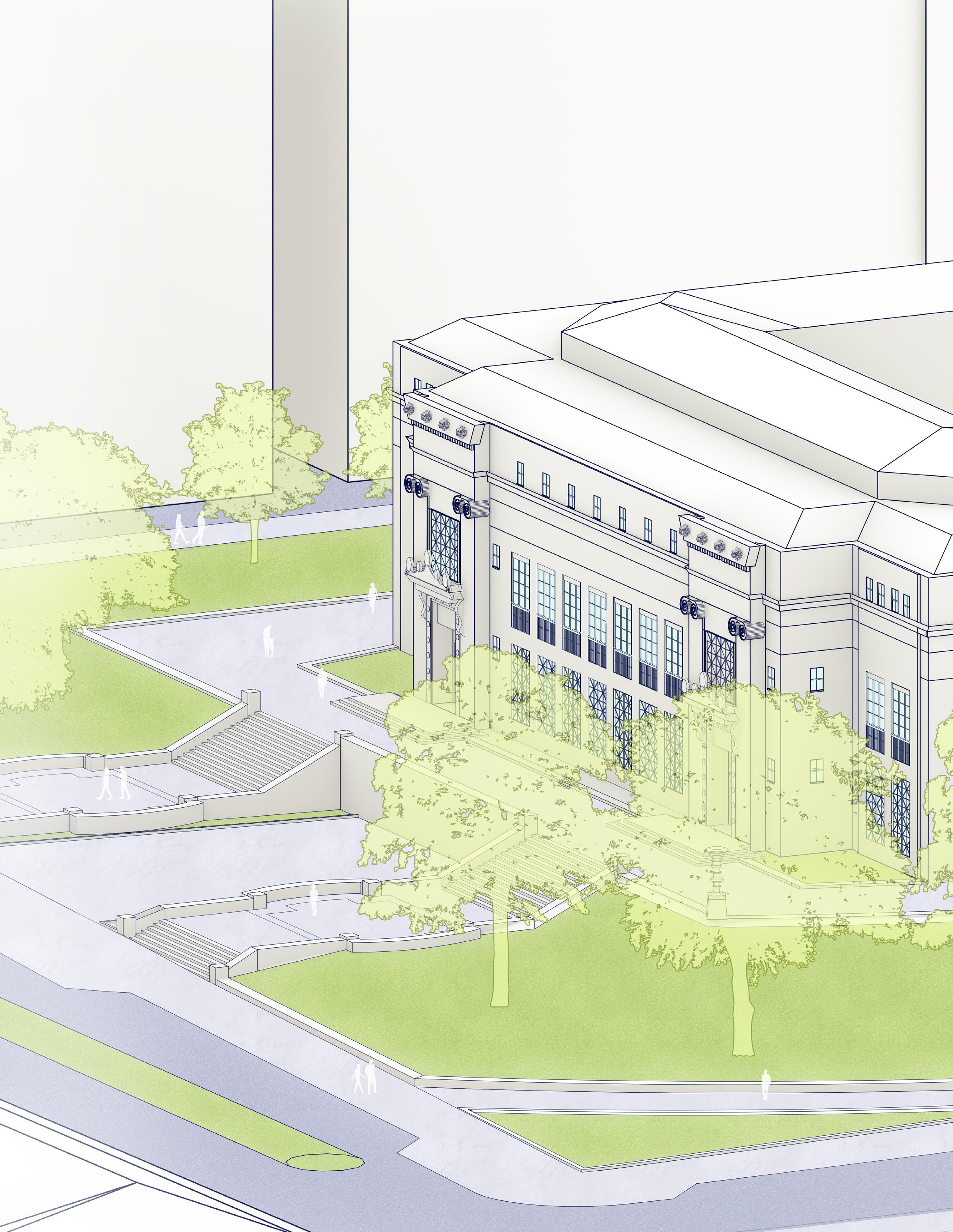

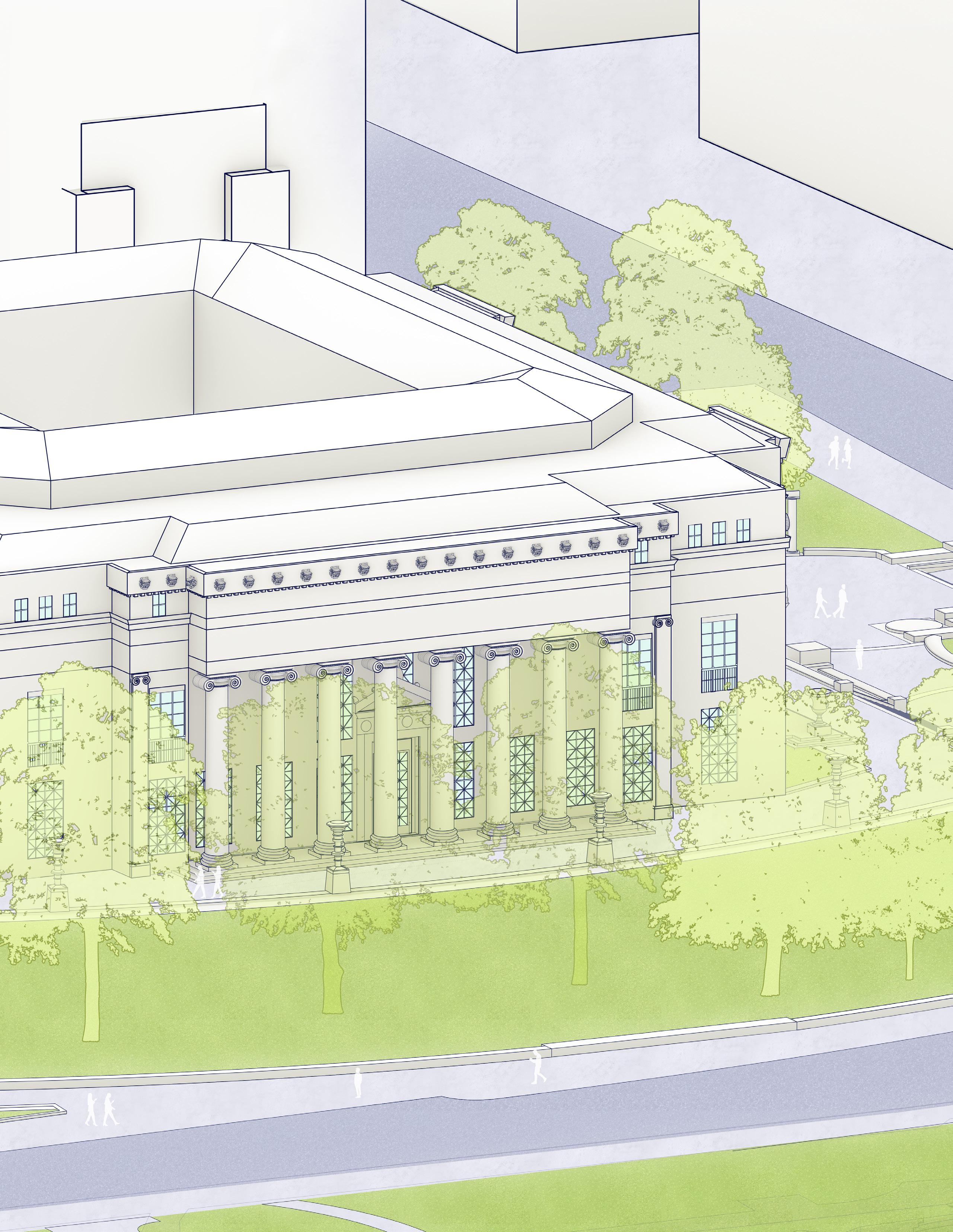

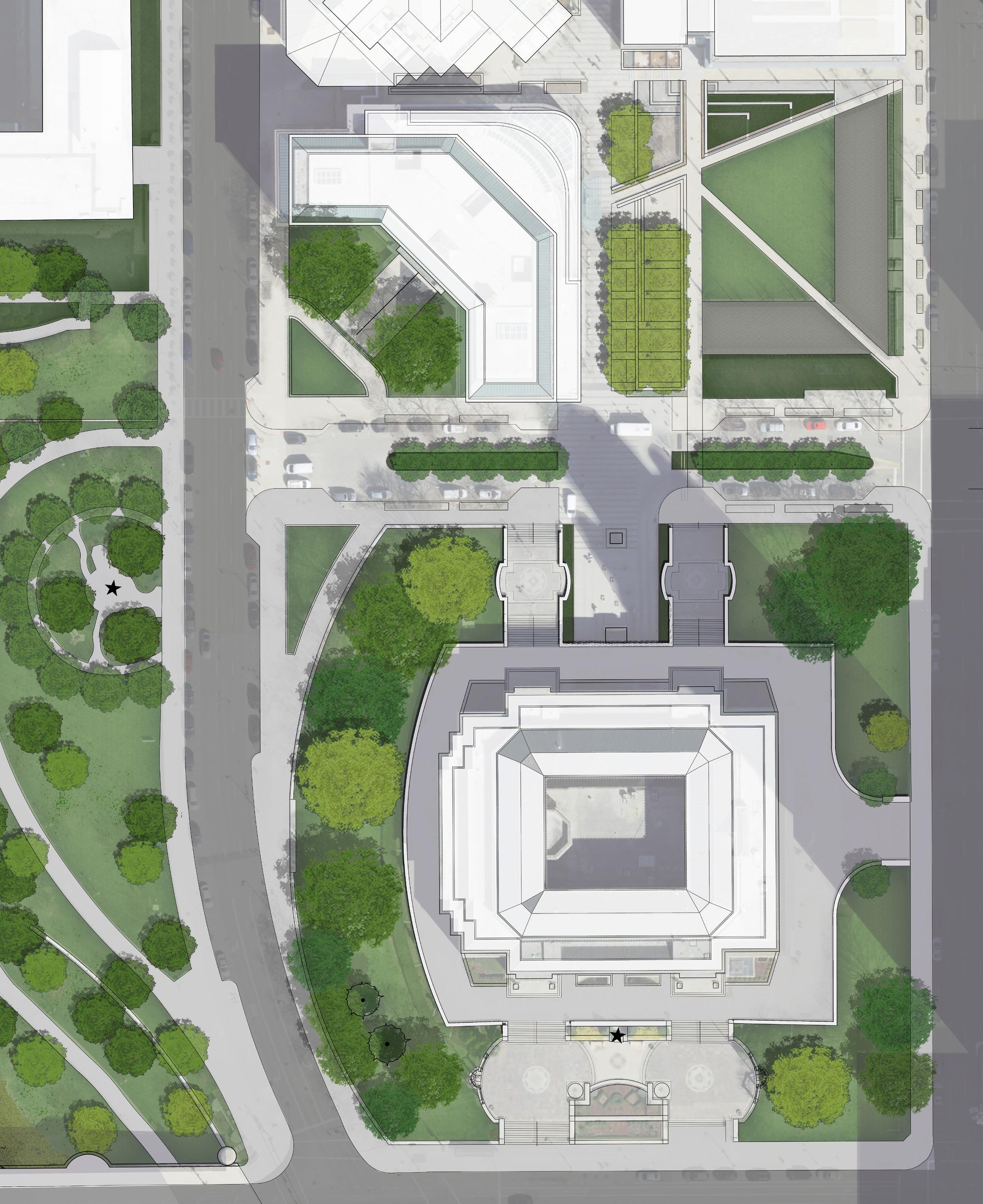

The site selected for City Hall ensured that the building’s stature in the public eye would be raised significantly. No longer would it be just another building in the Capitol Square streetscape like its late predecessor. It would be situated just west of the city’s Broad and High Streets intersection — the city's busiest, and where its East–West and North–South streets meet — and have a presence appropriate to its purpose. Surrounded by a broad paved plaza and landscaped grounds, it would be elevated several steps above West Broad Street, with its main entrance facing that street.

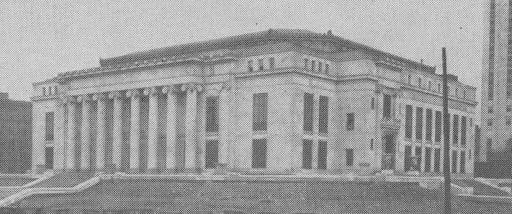

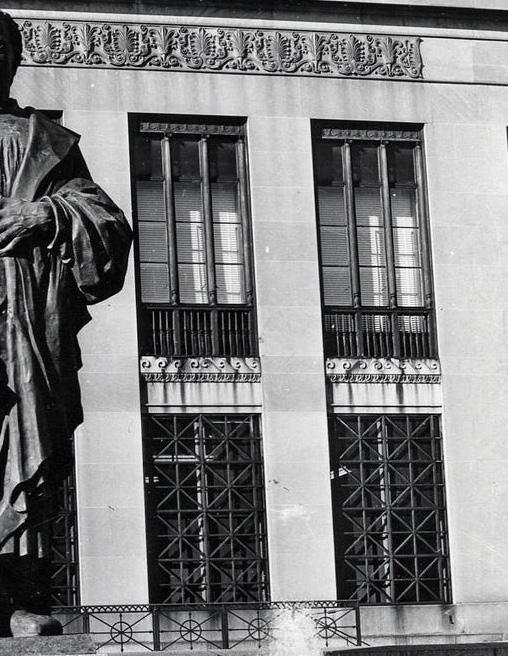

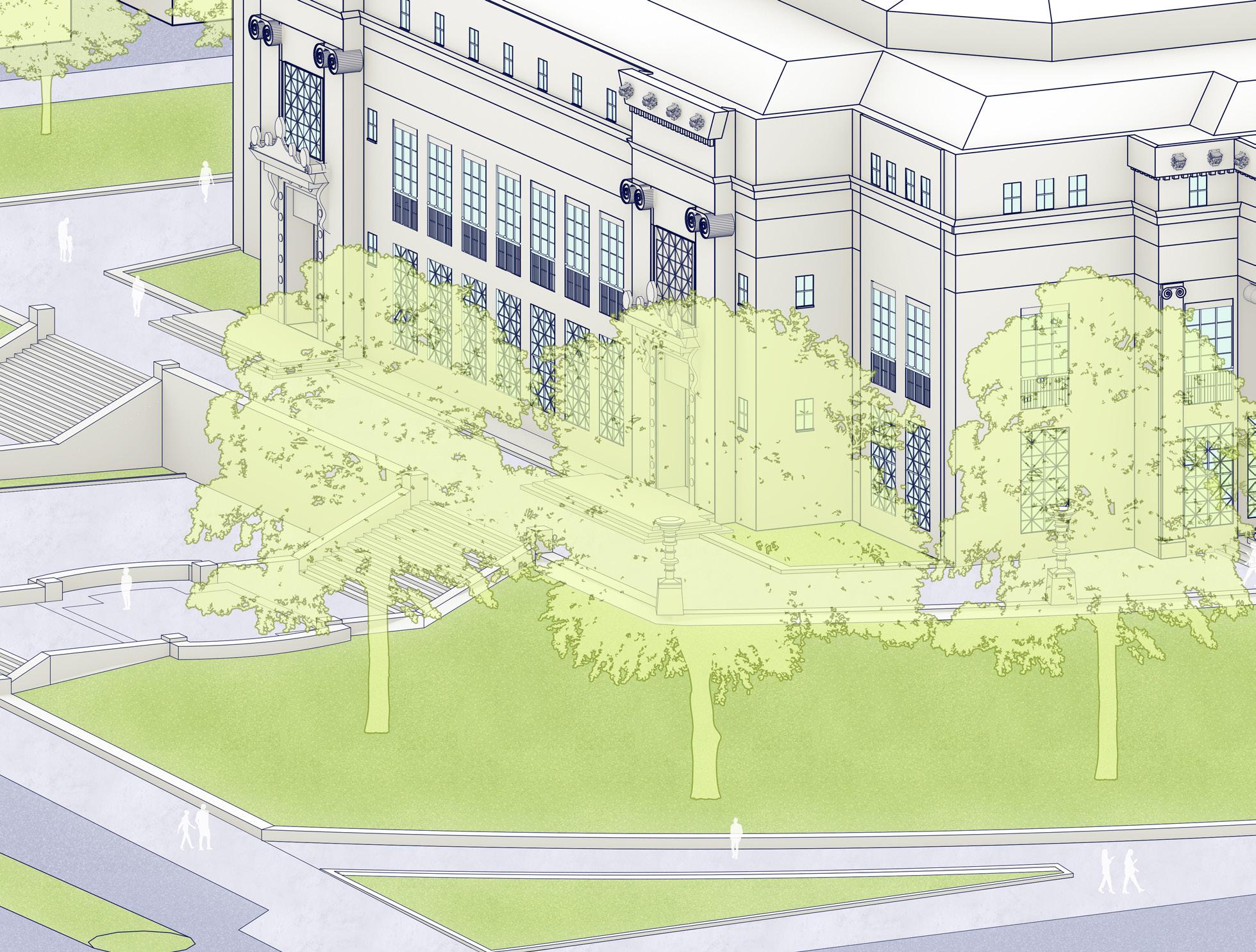

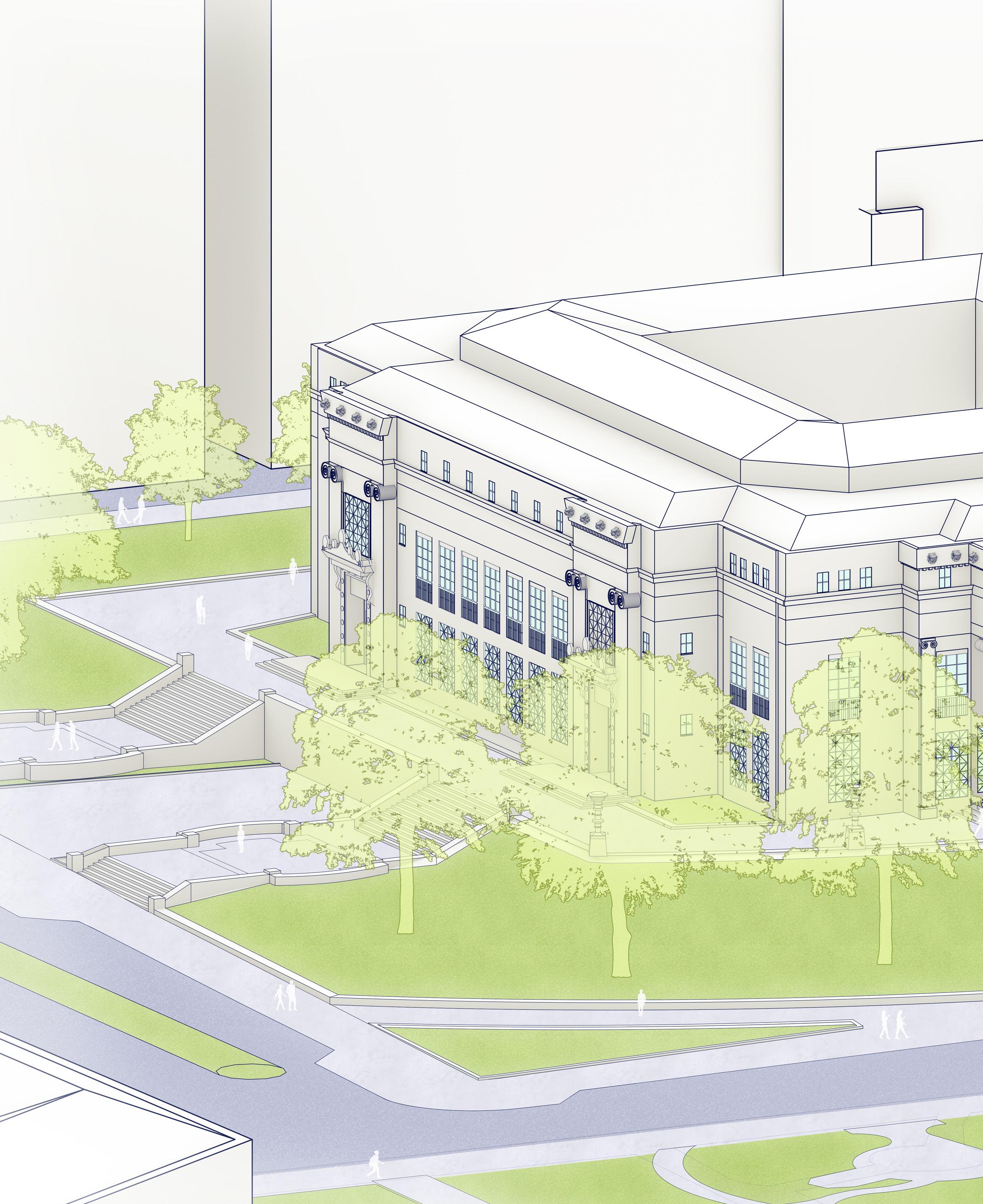

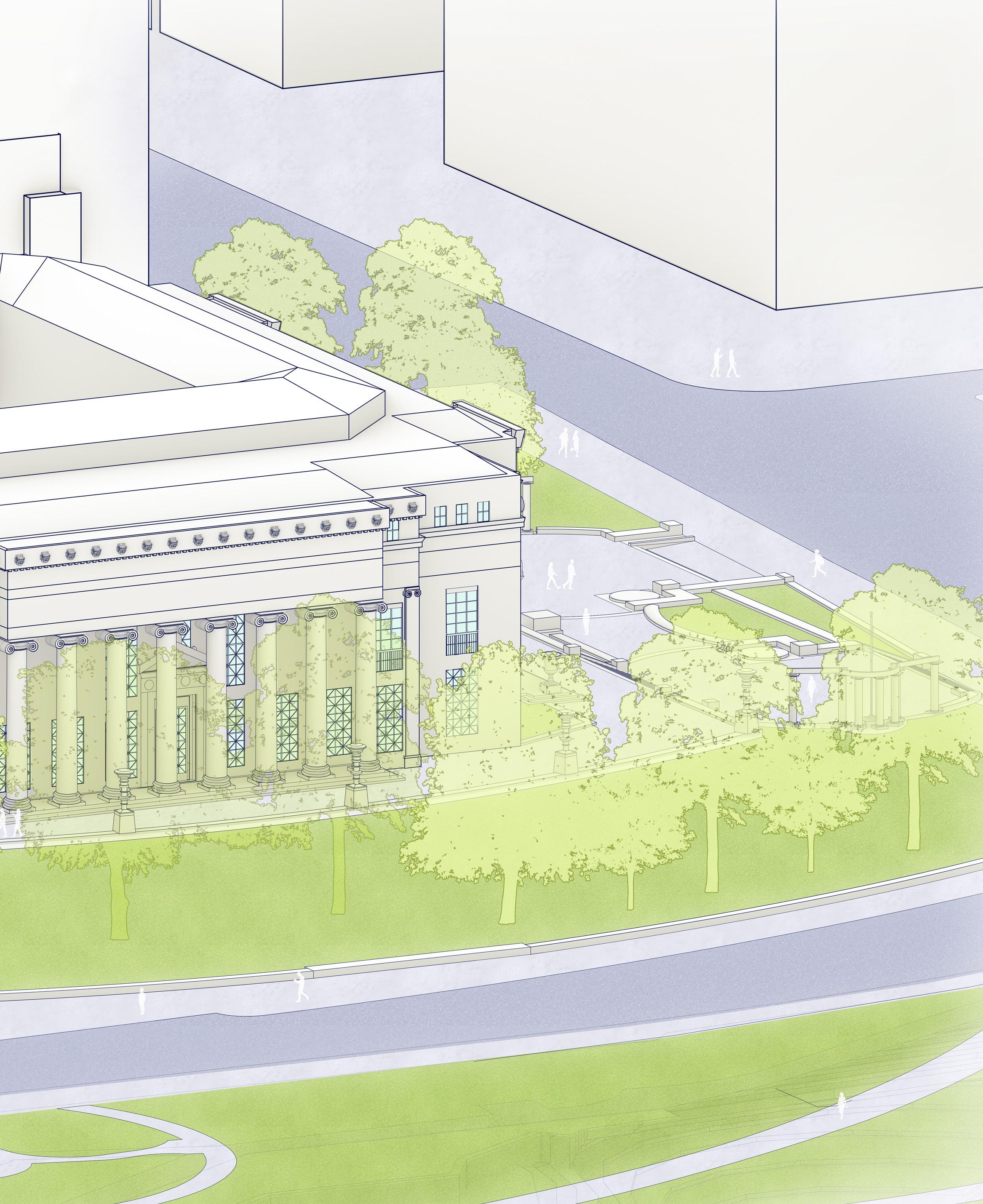

City Hall was designed in the Neo-Classical Revival style and employs elements from architectural history. It features eight two-story Ionic columns supporting a stone entablature on the west elevation. Stone pilasters and engaged columns with carved stone entrances and classical detailing adorn the other elevations. Exterior architectural features include elements visible from any of the four streets that surround the site, and evoke the building’s imposing form, scale, and height: the limestone surfaces and decorative finishes; the pattern, size, and placement of windows; the carved stone entrances on all elevations; and the paved plazas around the building.

1.6. This aerial view of City Hall under construction shows the AIU Citadel (later the LeVeque Tower) in the foreground nearing completion. Also visible in the upper left corner is open space along the riverfront where the retaining wall would soon be built. Source unknown.

FIGURE 1.7. Construction of the east wing completed the four-sided design. Source unknown.

FIGURE 1.8. A view of City Hall shortly after the completion of Phase 1 shows the massive stone columns that mark this imposing elevation facing the riverfront. A large paved plaza with steps leading to the riverfront was an integral part of the design; the steps were later removed. Source unknown.

The building was constructed in two stages. The original portion of the building consisted of the west, north, and south wings, which gave the building the form of a “C,” with a central courtyard; this was completed in 1928. Construction of the east wing in 1936 completed the four-sided composition originally proposed; the central court was roofed over around 1950 to create additional indoor space.

City Hall housed a large number of offices. In addition to the mayor’s office in the southeast corner of the building and the City Council chamber on the west side (both on the second floor), other major spaces included the treasurer’s office on the first floor of the west side and the law library on the north side of the second floor. One of the most elegant features of the building was — and still is — the graceful cantilevered and curved marble staircase on the west side leading to the corridor outside the city council chamber. The open court on the interior of the original U-shaped building allowed all offices to receive natural light. A widely-displayed scale model promoted the new City Hall to the general public; it made it clear that the design was always intended to have four elevations and a generously-sized site compared to the former building on Capitol Square.

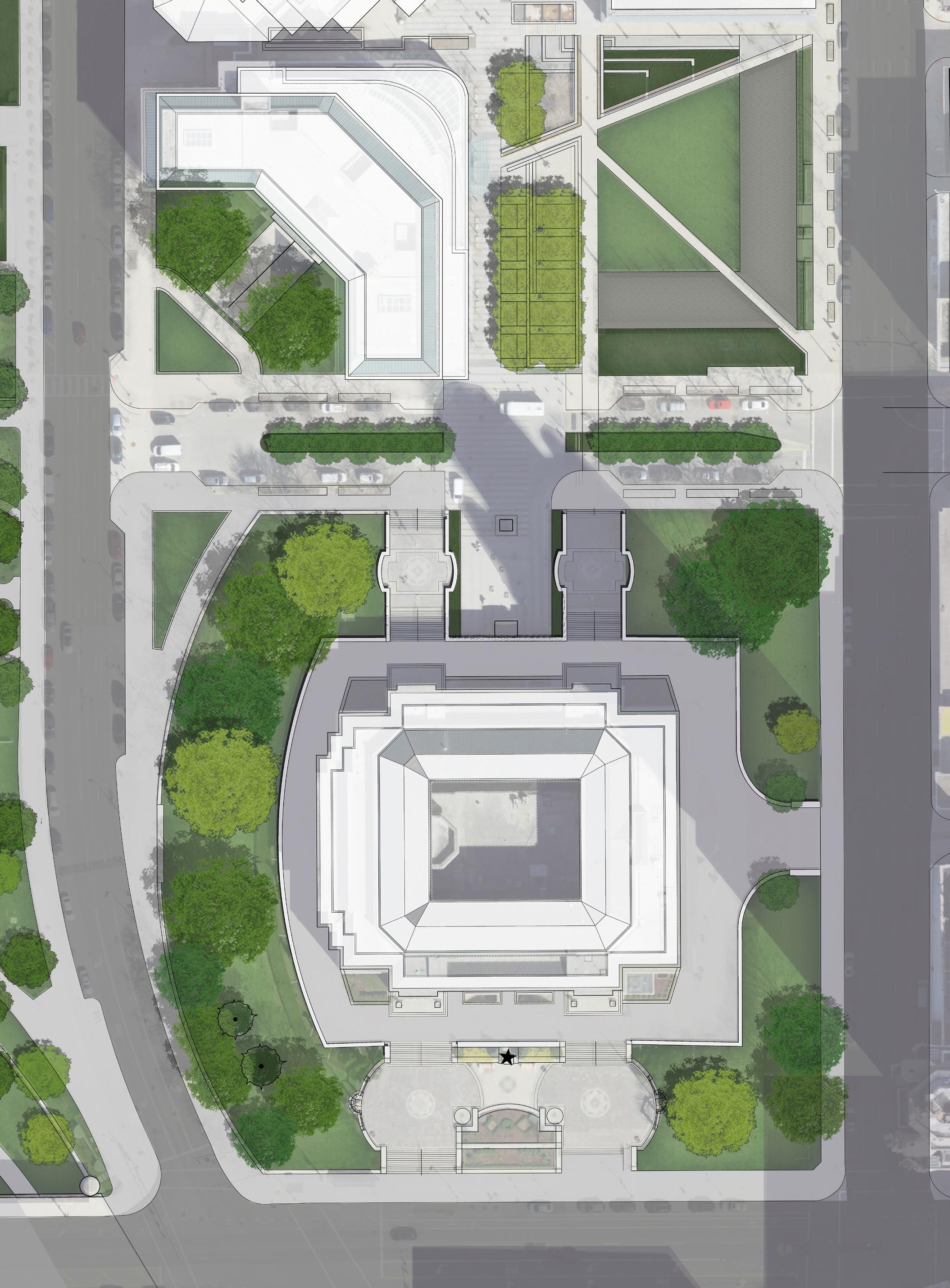

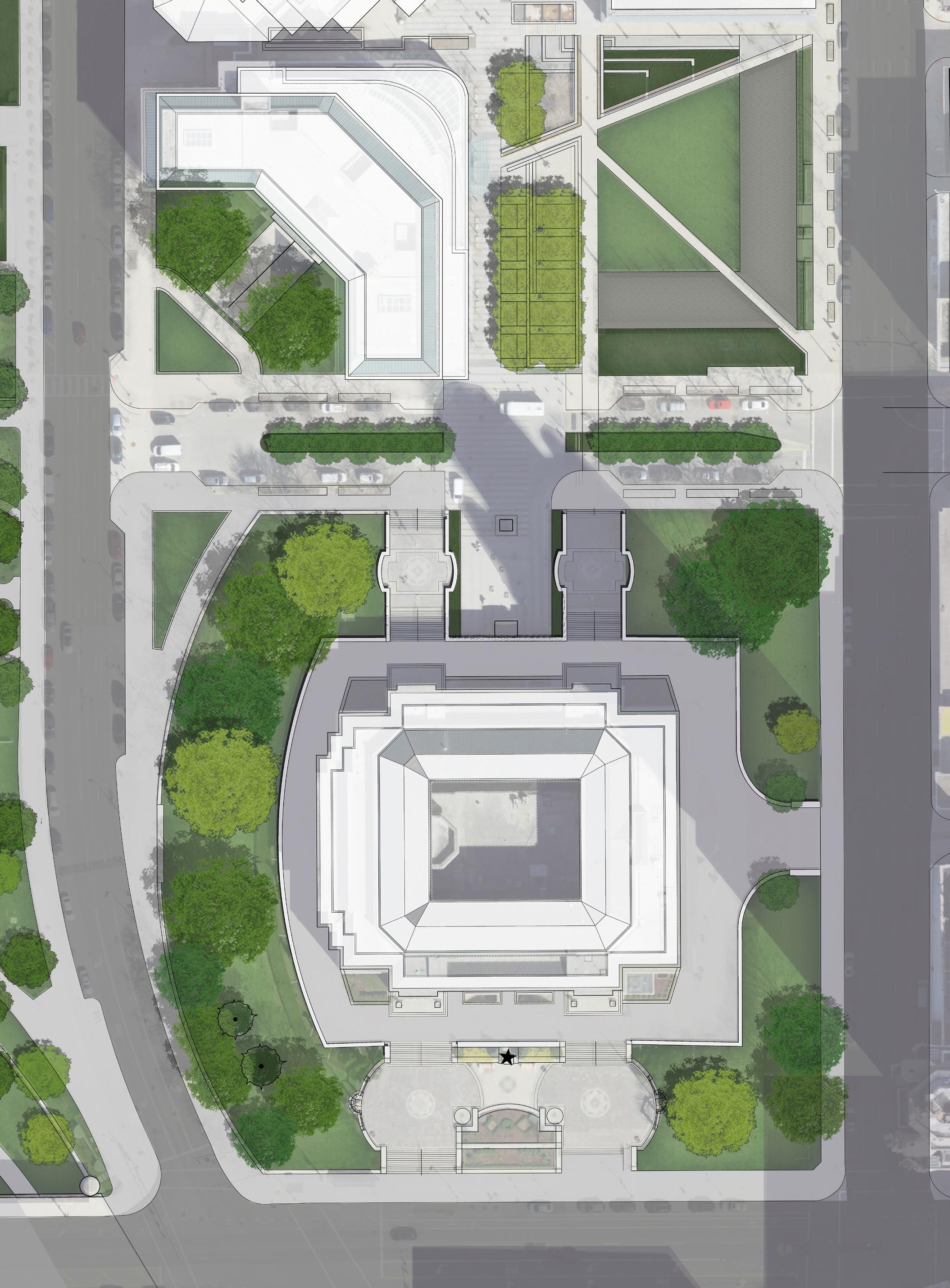

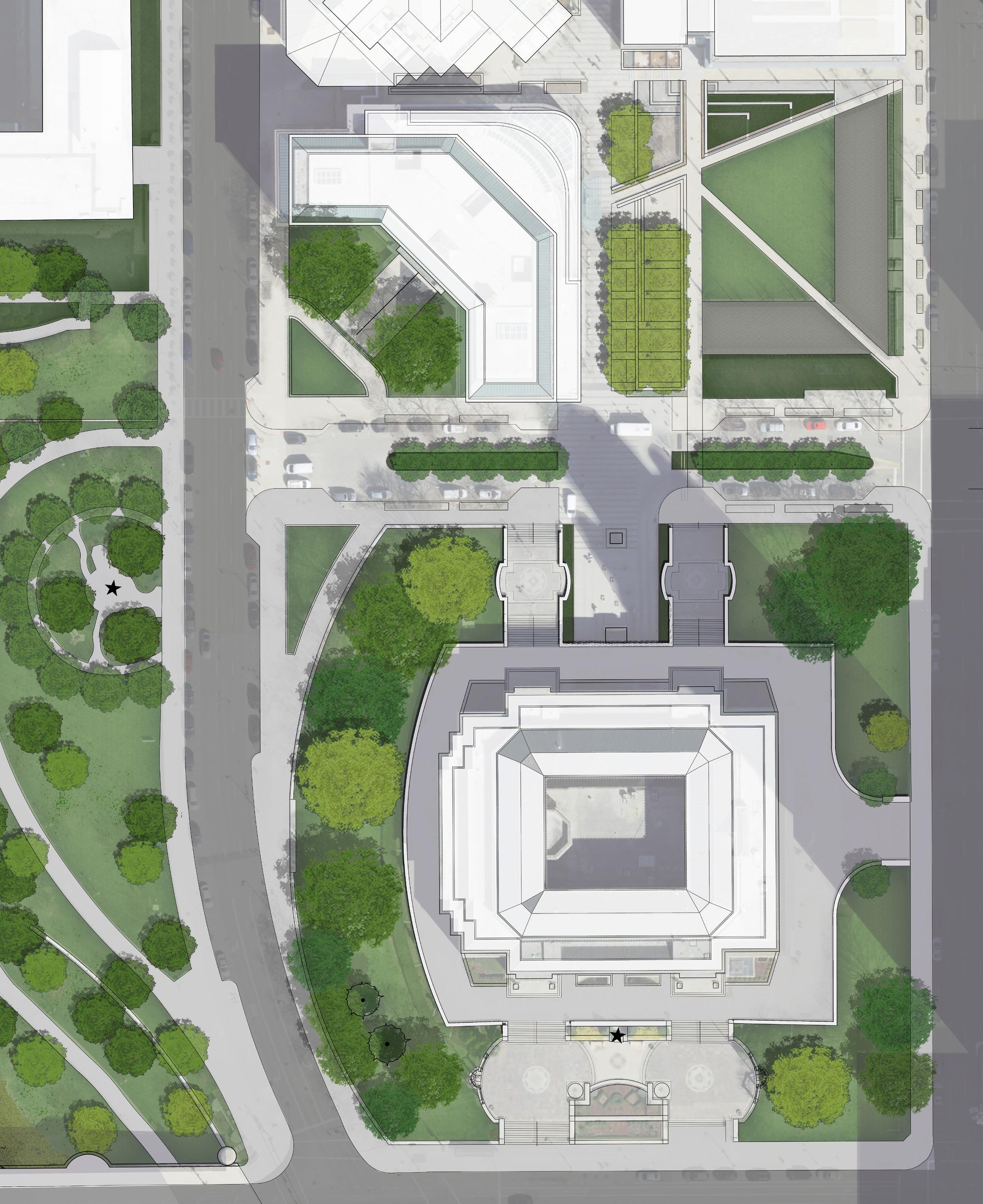

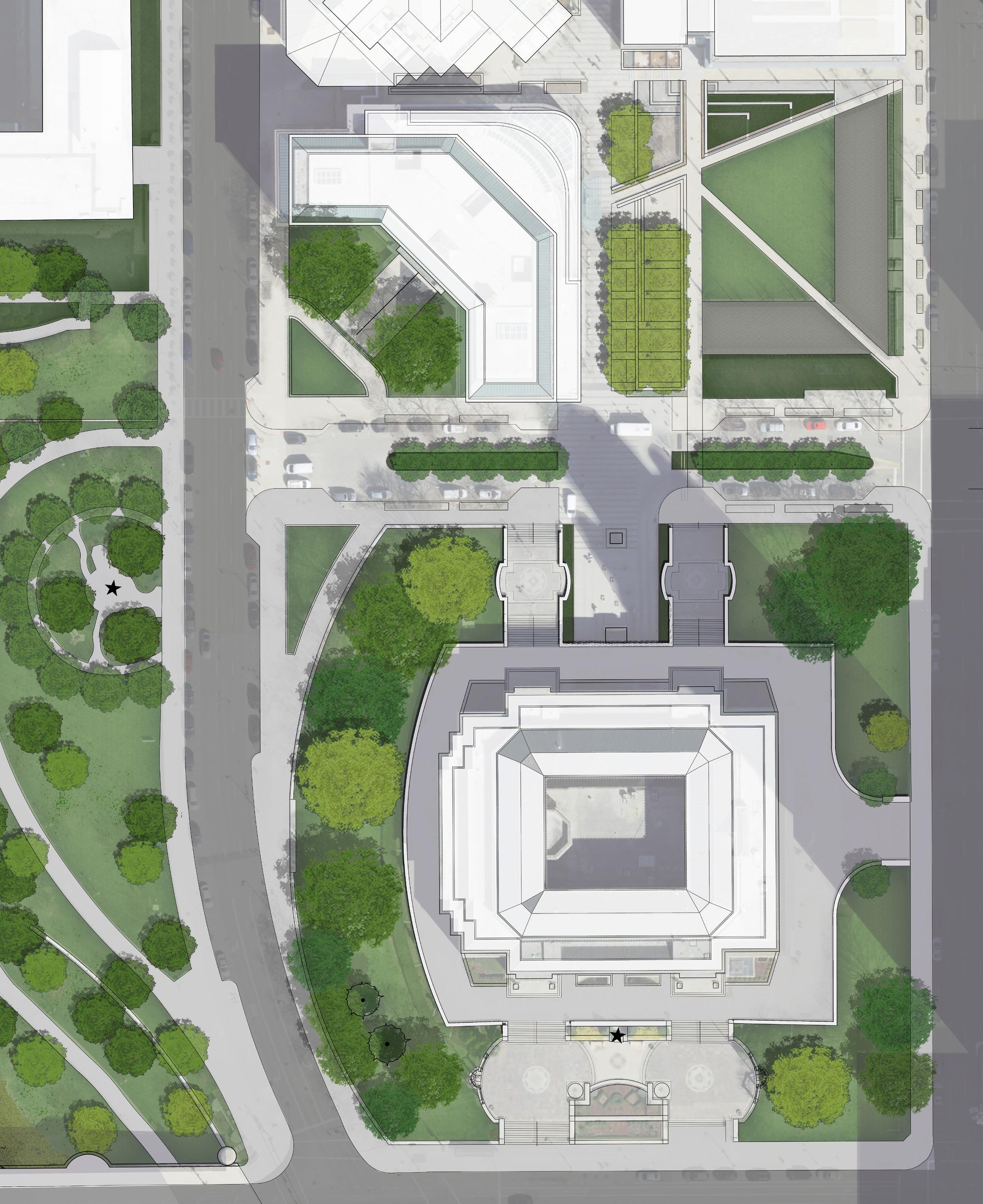

With the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue that had graced the steps of City Hall since 1955, the campus no longer features public art. This section shows the monuments and public art nearby, and the site characteristics that informed the art intervention recommendations in this plan.

Columbus City Hall is a centerpiece of downtown’s public places, greenways, and recreational spaces. Despite its proximity to public art — including sculpture on private developments, art in parks, and numerous murals — City Hall does not feature its own exterior public art collection. Current public artworks and monuments displayed in the vicinity of City Hall memorialize historic events or honor local leaders, leaving space for future public art that uplifts richly diverse histories of the Columbus community and celebrates residents' lived experiences today.

While they may seem interchangeable, public artists working today often understand the words "monument" and “memorial” to have subtle but meaningful differences. Both are tributes to an event, person, idea, or story that can take any number of forms, from statues to buildings, landscaped plazas, murals, and more. The key difference is that monuments are considered to be more triumphant and celebratory in nature — for example exploring themes of military heroism — while memorials are spaces of introspection in which to honor loss or sacrifice. The most successful monuments and memorials are those that thoughtfully reflect a society's most treasured narratives and devastating losses. These critical pieces of public infrastructure help a community tell the story of who they are, where they have come from, and where they are going in the future.

A monument celebrates a heroic person, a significant event or victory, or a social ideal. Its purpose is to stand as a lasting tribute to something considered triumphant. Monuments are typically built to be grand and highly visible, and to inspire a sense of pride or admiration.

A memorial commemorates an event or a person or group, often for their loss or sacrifice. Its purpose is to evoke remembrance and grief or respect for that which has been lost. Memorial spaces are designed to encourage visitors to pause, introspect, and pay tribute to who and what is being memorialized.

Primary Goal

Intended Tone

Thematic or Narrative Focus

Intended Experience

To celebrate and honor

To remember and revere

Triumphant, grand, majestic, powerful Somber, reflective, poignant

An achievement, heroism, celebration, honor Loss, sacrifice, commemoration, remembrance, tribute

Inspiring awe and pride Encouraging reflection and remembrance

Examples Washington Monument, Statue of Liberty, equestrian statues of military leaders Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 9/11 Memorial & Museum, Lincoln Memorial

“Statement piece” of the campus

Historically significant architecture

Ceremonious, official characteristics

Public face of the city, often in photos and national news reports

Functional

Utilitarian

Daily operations

Informal

1" = 80' N

0' 40' 80'

Proximity to the street

Pedestrian-level entry point

Official, yet welcoming

Site for public demonstration

Mixed opinions on the Columbus statue

Entry barriers

W BROAD ST

Deepest setback from the street

W BROAD ST

Sloped elevation

The Christopher Columbus statue that stood at the building's south side for 65 years was the only piece of public art on the grounds of City Hall. When it was removed in 2020, city leaders were clear that it would not be reinstalled there. In 2023, the city announced a $1.5 million commitment to replace the statue with new public art. Through this plan, the process to fulfill on that promise can commence. In the meantime, the plinth where Columbus stood will remain empty, and there is no art to be experienced on Columbus City Hall Campus.

What is now a grand but underutilized space has the potential to enliven downtown Columbus and better serve city residents. This section offers the goals for this plan and a bold vision for what public art could allow City Hall Campus to become.

The City Hall Art Plan will leverage a range of public art and placemaking typologies in order to:

• Revive the original intention for City Hall to serve as the central civic plaza for Columbus

• Provide spaces for public engagement, recreation, cultural expression, civic interaction, and gathering

• Respond to City Hall’s historic architecture and invigorate underutilized spaces

• Support the needs of city staff and operations, while expanding the site’s symbolic role in the community

• Propose processes and policies that support the long-term care, maintenance, and growth of the City Hall Campus Art Initiative

Columbus City Hall Campus is an active public space reflecting residents' shared civic values with temporary and permanent public art and placemaking elements that foster belonging, honor complex histories, and invite exploration.

The following pages break this vision out into its parts to provide clarity about each.

City Hall Campus art declares "there is something to see here" and creates a hub of activity where there had been none.

City Hall Campus art may explore controversial themes and content, but foremost emphasizes that which brings about community connection and, through that, civic engagement.

City Hall Campus art offers a dynamic collection, with both permanent and rotating pieces, augmented by programming and placemaking elements such as landscaping, architectural features, and custom lawn furniture.

City Hall Campus art is welcoming to all and, in its totality, allows everyone to feel they are represented in the space.

City Hall Campus art unflinchingly connects people to the true stories of their ancestors' hardships and resilience.

City Hall Campus art offers multiple types of experiences that people can choose to enjoy as they wish.

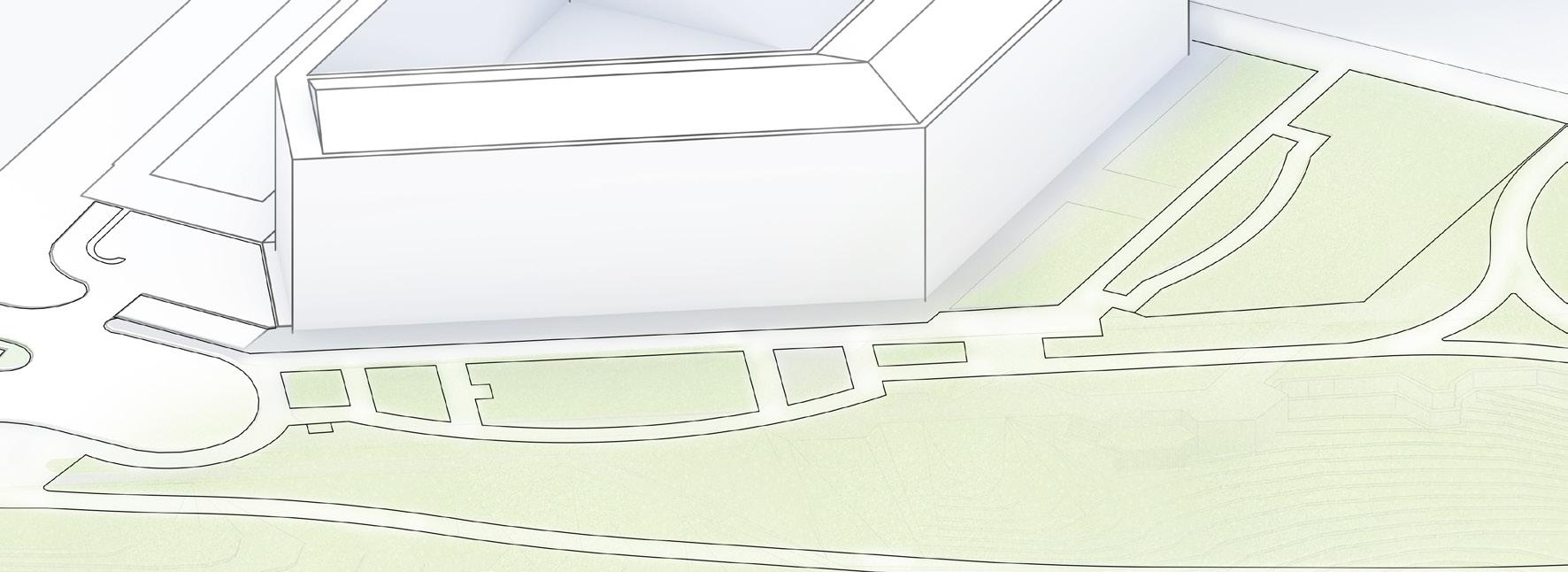

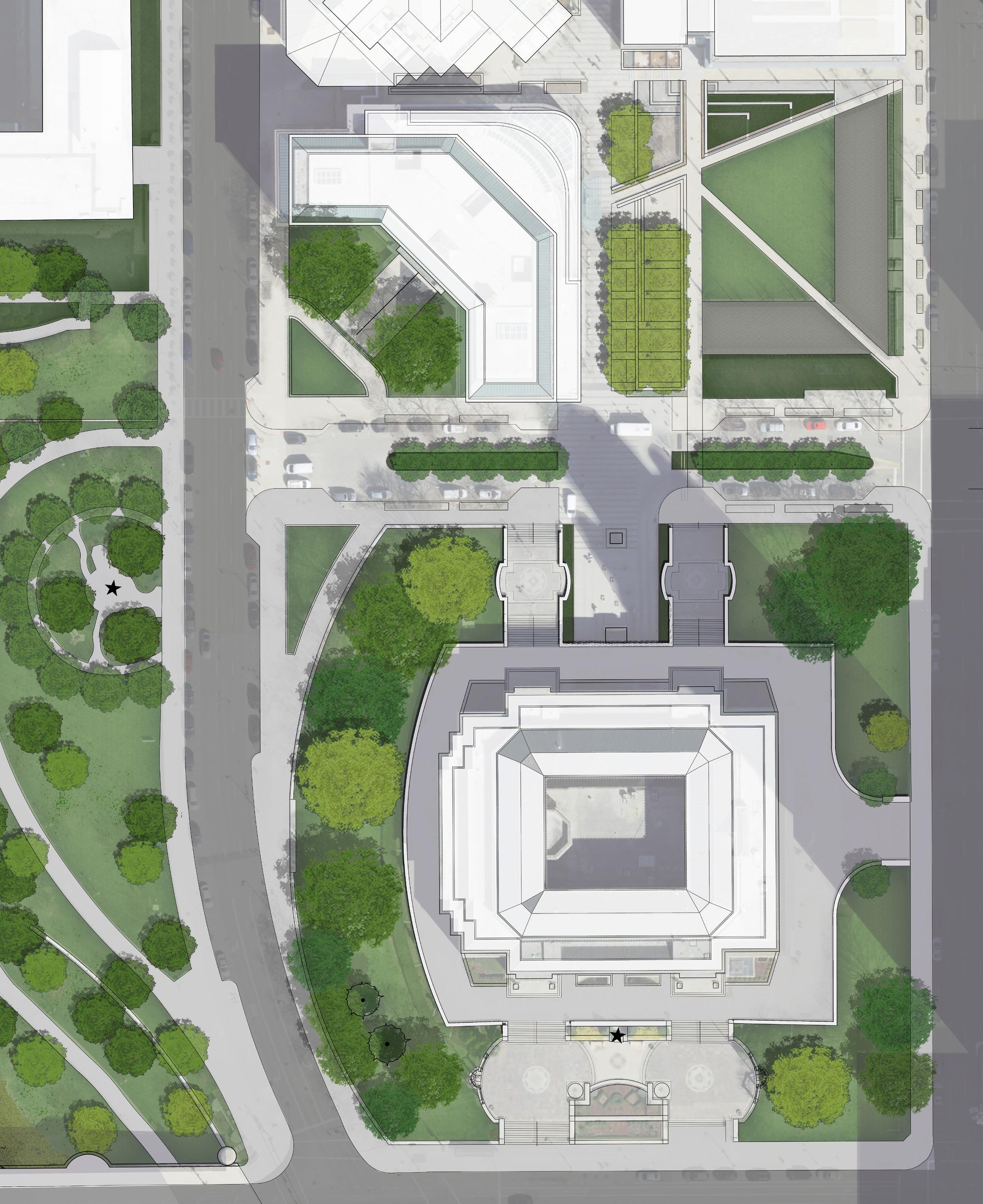

With the Columbus statue no longer standing at City Hall, the campus is devoid of public art. This section recommends art interventions for the building's exterior spaces that respond to the unique functions and characteristics of each side of City Hall, the site's broader history, and the call for more inclusive public art, as expressed through the Reimagining Columbus project.

Functional

Utilitarian

Daily operations

Informal

Responsive to architectural elements

Visually interesting from multiple vantage points

Conceptual and thought-provoking

An outward expression of the city’s character, complexity, and values

Approachable

Calming

Unifying

Harmonious

Site for public demonstration

Mixed opinions on the Columbus statue

Entry barriers

Deepest setback from the street

W BROAD ST

Sloped elevation

The following types of art have been identified as being appropriate for specific areas of the Columbus City Hall Campus.

IMMERSIVE AND SUSPENDED ART

POP-UP EXPERIENCES

A BRIDGE OF STORIES

BROAD ST BRIDGE PLATFORMS

CONTEMPLATIVE INSTALLATIONS

Due to the campus’ administrative function and high-profile status, this location requires a public art strategy that supports both the site’s day-to-day operations and its figurative role within the community.

SOUND INSTALLATIONS

THE PLATFORM

THE COLUMN COMMISSION

CONCRETE INLAY

SOUTH STAIRCASE ACTIVATIONS

PUBLIC SPACE

• Greenspaces

• Contemporary architecture and public spaces

• Offices and staff entrances

• Walkway between campus buildings

• Social nodes or connection points

EXPERIENCE

• Functional

• Utilitarian

• Daily operations

• Informal

0' 40' 80' 1" = 80' N

SOCIAL NODES OR CONNECTION POINTS

WALKWAY BETWEEN CAMPUS BUILDINGS

OFFICES AND STAFF ENTRANCES

CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE AND PUBLIC SPACES

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

POP-UP EXPERIENCE

PUBLIC ART HERE SHOULD FEEL...

ACCESSIBLE

INTERACTIVE

IMMERSIVE AND SUSPENDED ART

POP-UP EXPERIENCE

Pop-up public art experiences assume many forms, ranging from multimedia light and sound installations to playful, otherworldly sculptures. These short-term experiences are ideal in large greenspaces or other public gathering spaces with clear sightlines for maximum visibility.

Investment

Cost Considerations

$15,000–$100,000

Duration of display, ongoing maintenance, existing vs. commissioned

Impact Medium

Complexity Low

Implementation

Considerations

Leveraging partnerships with local organizations to encourage a wider range of audiences to experience the artwork; planning the display period during a popular downtown experience

Exemplar images

As visitors move through the various public art interventions around City Hall’s campus, they will encounter artworks that foster curiosity, playfulness, reflection, and connection. Immersive and suspended artwork can support this goal through their experiential and sensorial characteristics, which simultaneously enhance and shape the feeling of public spaces. An example of the positive impact of this kind of public art strategy is Janet Echelman’s Current , a suspended piece that anchors downtown Columbus’ creative, social, and commercial corridor and has become a highly anticipated seasonal experience. City Hall’s campus offers several green spaces and open areas to place artworks that invite participation and surround visitors in dynamic, unexpected environments that offer contemplative and otherworldly moments.

Investment $75,000–$200,000

Cost Considerations Loan fees, site preparation fees, related programming fees

Impact Medium

Complexity Medium

Implementation

Considerations Partnering with parks spaces

Clockwise, from top: FIGURE 4.3. Rachel B. Hayes, Horizon Drift (2024), Denver, Colorado. Provided by Black Cube. FIGURE 4.4. Daniel Buren, Photo-souvenir: The Garlands (1982–2019), The High Line, New York, NY. Photo: Timothy Schenck, courtesy the High Line. FIGURE 4.5. Teresita Fernandez, Fata Morgana (2015–2016), Madison Square Park, New York, NY. Photo by Elisabeth Bernstein. FIGURE 4.6. Janet Echelman, Current (2023–2025), Columbus, Ohio.

Exemplar images

PUBLIC SPACE

• City Hall public entrance, the “front door”

• Pedestrian area

• Underutilized hardscape areas

• Greenspaces

EXPERIENCE

• Proximity to the street

• Pedestrian-level entry point

• Official, yet welcoming

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

CONTEMPLATIVE INSTALLATION

PUBLIC ART HERE SHOULD FEEL...

APPROACHABLE

CALMING

UNIFYING HARMONIOUS

CONTEMPLATIVE INSTALLATION

CONCRETE INLAY

City Hall Campus lawns are ideal for both temporary and permanent contemplative installations. In response to this plan’s guiding principles, the City Hall Campus Art Initiative should offer public art that encourages contemplative opportunities. These encounters should be scalable for both individual and collective audiences. Contemplative spaces can assume a number of forms, ranging from a permanent artist-designed landscapes, to temporary, nature-based sculpture, and everything in between. In Rachel Hsu’s temporary project The Weight of Our Living in Philadelphia, the artist drew inspiration from publiclyaccessible reflexology paths in Taiwan's parks, inviting audiences to walk barefoot across the stone surface. Similarly, Jenny Kendler’s Mending Wall provides space for personal and collective gathering, exchange, and rest at a site that features reclaimed local stones and permanent native plantings. Finally, April Banks’ A Resurrection in Four Stanzas in Santa Monica immortalizes local histories of the African American neighborhoods around Belmar Park through a permanent sculpture that simultaneously preserves the past while honoring its absence and erasure. These interventions can inspire thought, joy, or even pain, but should ultimately provide a public space for wonder and restoration.

Investment

Cost Considerations

$75,000–$250,000

Site preparation, engineering, and/or landscape architecture fees

Impact High Complexity

Medium–High

Implementation Considerations

Ensuring that installations represent the widest possible demographics by working with local nonprofits, affinity groups, and cultural organizations to curate these opportunities

Clockwise, from top: FIGURE 4.7. April Banks, A Resurrection in Four Stanzas (2021), Historic Belmar Park, Santa Monica, CA. FIGURE 4.8. Rachel B. Hayes, Round the Bend (2023). FIGURE 4.9. Rachel Hsu, The Weight of Our Living (2024). Photo by Constance Mensh, Courtesy of Association for Public Art. FIGURE 4.10. Jenny Kendler, Mending Wall (2022), Chicago, Illinois. Photo courtesy of the artist. FIGURE 4.11. Daekwon Park, Immersive Cloud (2017), Syracuse, NY.

Exemplar images

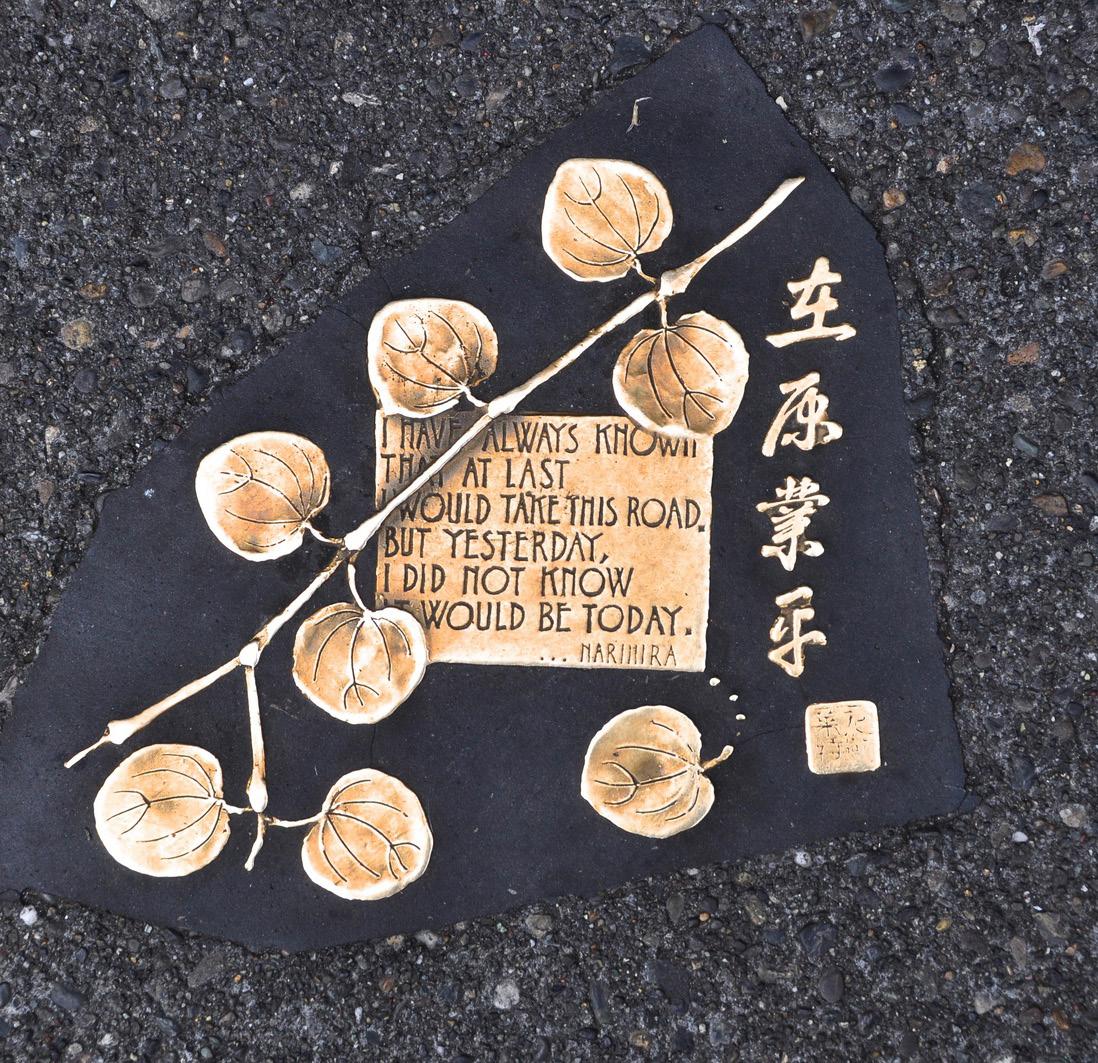

Concrete art includes opportunities to inlay or apply artist-designed patterns and compositions in walkways using mixed metals, mosaics, stamps, or other materials. Using infrastructure as a canvas, these interventions not only add character and visual interest to the area, but also provide opportunities for traffic calming and enhanced safety. A mix of temporary (crosswalk murals or chalk art) and permanent interventions (using metals, pavers, bricks, and beyond) should be explored to maximize visual interest. These permanent strategies offer surprising, yet subtle character to the site’s mixed-use trails and paths, and double as a placemaking opportunity to establish the campus footprint among downtown’s intersecting areas. Projects could include visual histories of the city’s past, portraits of residents and local icons, or written words from the many languages spoken in Columbus.

Investment

Cost Considerations

$75,000–$200,000+

To maximize the investment of this strategy, any anticipated future path repairs or development could include public art in the project scope.

Impact High

Complexity High

Implementation Considerations

Siting on city-controlled property and citymanaged rights-of-way, or exploring easements for privately-owned pathways

Clockwise, from top: FIGURE 4.12. Ryah Christensen, Reflections on the Brazos (2015), Austin, Texas. FIGURE 4.13. Dan Snyder, Listen to the Fish (2003), Stockton, CA. FIGURE 4.14. Unknown artwork, Pike Place Market, Seattle, Washington. FIGURE 4.15. Esther Shalev-Gerz, The Shadow (2018), University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Photo by Robert Keziere.

Exemplar images

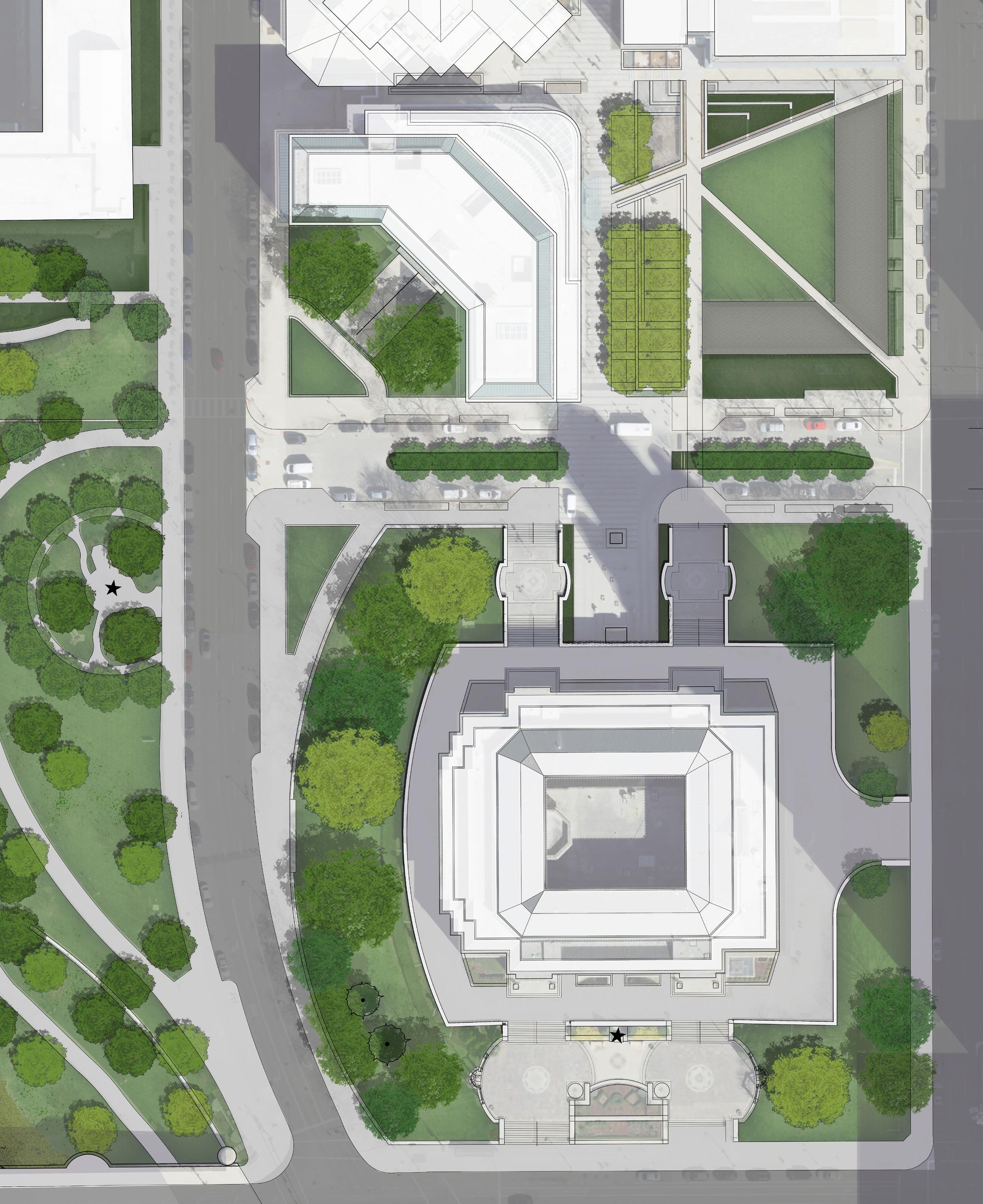

PUBLIC SPACE

• Honorific and memorial spaces

• Former site of the Christopher Columbus statue

• Underutilized hardscape areas

• Grand ceremonial space for gathering

EXPERIENCE

• Site for public demonstration

• Ambivalence regarding the absent Columbus statue

• Entry barriers

• Deepest setback from street

• Sloped elevation

GRAND CEREMONIAL SPACE

GRAND STAIRCASE

FORMER STATUE SITE

HONORIFIC AND MEMORIAL SPACES

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

A BRIDGE OF STORIES

BROAD ST BRIDGE PLATFORMS

PUBLIC ART HERE SHOULD FEEL...

INCLUSIVE UPLIFTING MULTI-DIMENSIONAL WELCOMING

MARCONI BLVD

W BROAD ST

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

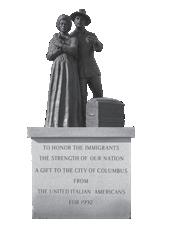

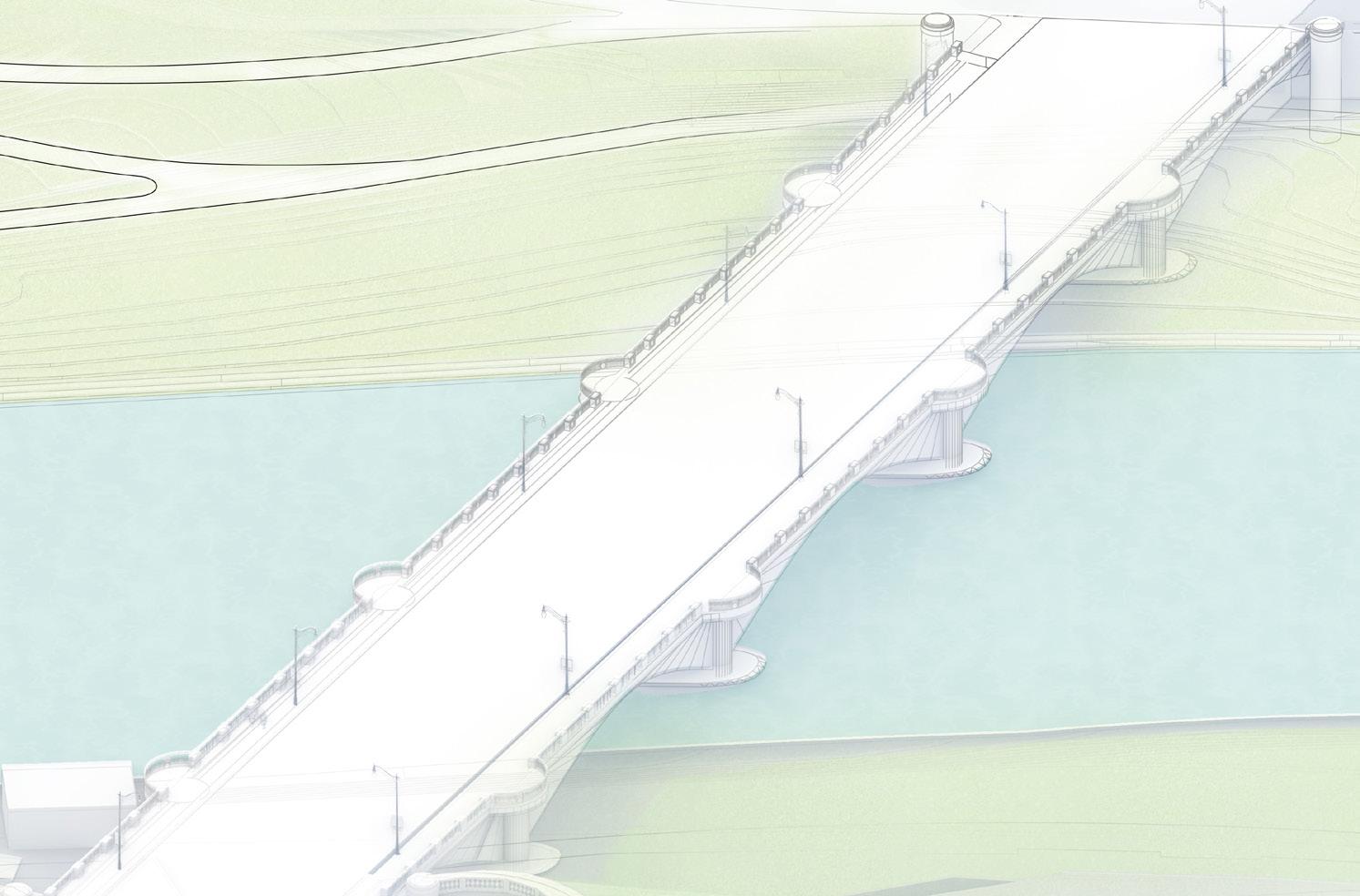

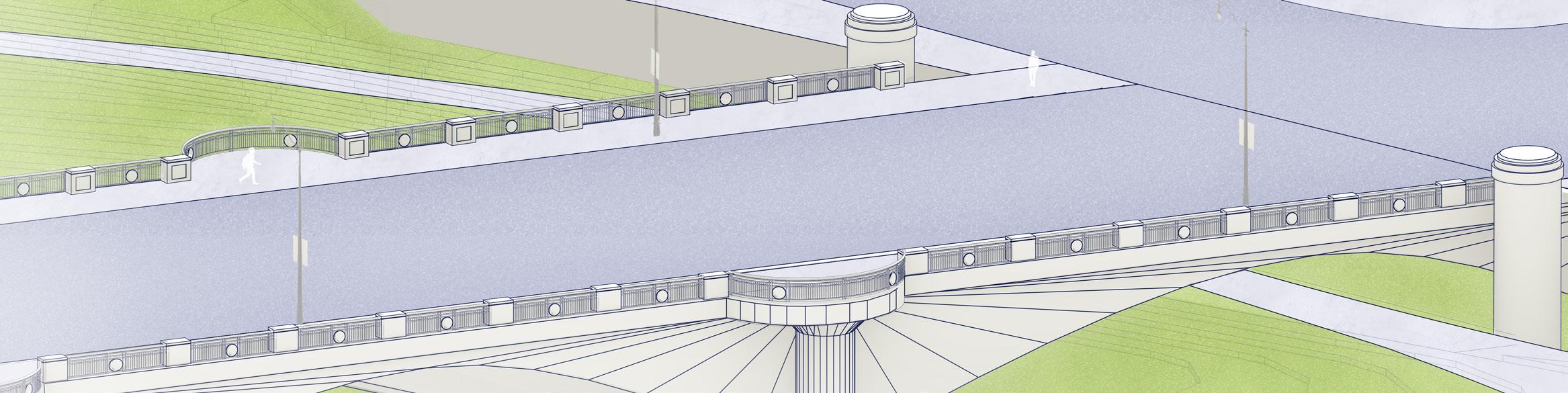

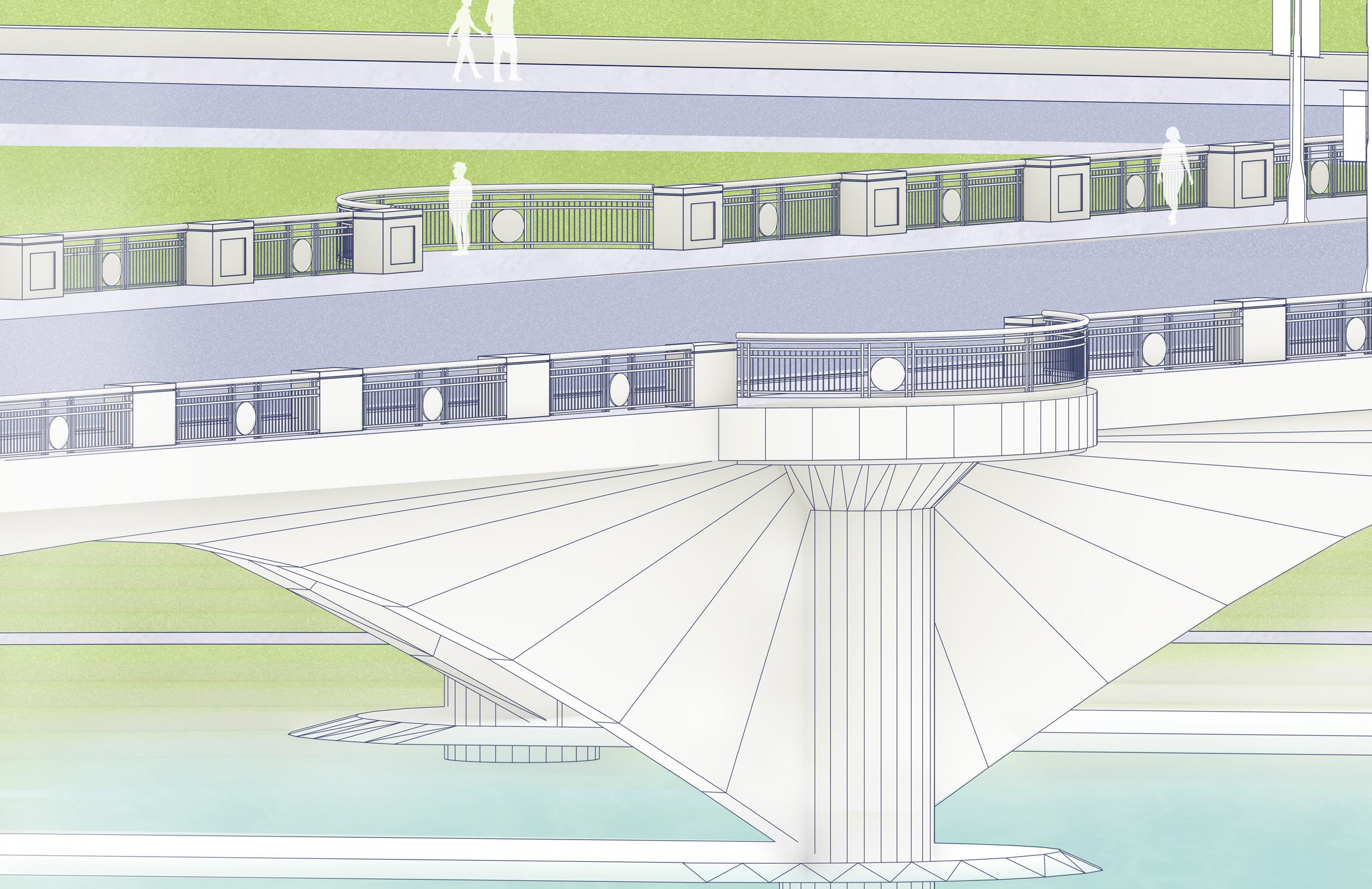

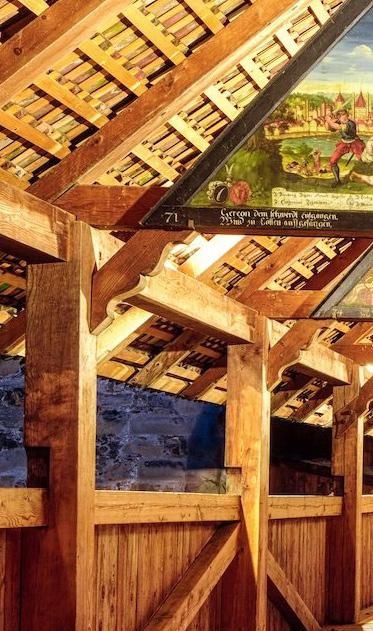

In 1992, as part of the programming in honor of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ voyage, Broad Street Bridge was named “Discovery Bridge” and decorated with 80 cast medallions, half featuring the city’s seal and the other half a design aligning with the quincentennial. The medallions were permanent features integrated into the bridge’s iron railing. For an ongoing, permanent public art project, the 40 medallions featuring the Christopher Columbus–centric design could be repurposed to better reflect the changing city. Using durable, two-sided acrylic discs, the medallions could feature artist-designed, engraved portraits of community-identified heroes and leaders. In order to convey the complexity of layered histories, the acrylic medallions could physically overlay the 1992 bronze medallions. Illuminating the medallions from within would convey the ever-present past, as this “Bridge of Stories” evolves over time.

Investment

Cost Considerations

Up to $5,000 per medallion, including design and fabrication costs

Equipment rental for projection, surface area of projection, content being projected, duration of projection

Impact High

Complexity Low

Implementation Considerations

Using proper materials, for example durable, thicker acrylic that can expand and contract to withstand extreme heat and cold; sizing medallions to 14 inches in diameter; using cables or sign standoffs for installation

Top: FIGURE 4.16. Long Street Cultural Wall, Columbus, Ohio.

Bottom: FIGURE 4.17. Chapel Bridge (2020), Lucerne, Switzerland. Image credit: Boris Stroujko

Exemplar images

Broad Street Bridge was designed with public art in mind, featuring four plinths at each of its corners where public art could be temporarily installed. These highly visible, pedestrian-friendly corners of Columbus’ civic space are prime opportunities to feature public art that represents and responds to contemporary life, history, and community. The High Line Plinth Commission in New York City and Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth Commission in London are internationally recognized sculpture competitions for emerging and established contemporary artists that promise to deliver iconic, ever-changing artwork in public spaces. Both can be considered templates for programming opportunities at the Broad Street Bridge plinths, as the spaces they offer for rotating art share are similarly integral to their respective cities’ unique character and infrastructure. In the same spirit as projects in New York and London, Columbus can activate the Broad Street Bridge plinths through public art and perhaps alternate existing artwork with newly-commissioned projects.

Investment $75,000–$300,000

Cost Considerations

Loan fees, site preparation fees, related programming fees

Impact High

Complexity Low

Implementation Considerations

Public safety for installations, ongoing program administration costs, programming around the artworks, and the possibility of alternating between existing work and new commissions

Clockwise, from top: FIGURE 4.18. Rachel B. Hayes, Columbus, Georgia, 2014. FIGURE 4.19. Rachel Whiteread, Monument (2023), Trafalgar Square, London. Image ©Rachel Whiteread, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, London. Image credit: Michael Crimmin / Greater London Authority. FIGURE 4.20. Simone Leigh, Brick House (2019), The High Line, New York, NY. FIGURE 4.21. Pamela Rosenkranz, Old Tree (2023–24), The High Line, New York, NY. FIGURE 4.22. Samson Kambalu, Antelope (2022), Trafalgar Square, London.

Exemplar images

Visitor traffic into City Hall is routed through the east-facing entrance on Front Street, leaving the staircases on the north and south sides of the building unused, yet highly visible to passersby. Staircase interventions ranging from two-dimensional vinyl murals to social furniture would activate these prominent, underutilized spaces. Other sidewalk or pedestrian surfaces could feature rain-activated art, which temporarily reveals images or poems.

Investment

Cost Considerations

$75,000–$200,000

Loan fees, site preparation fees, related programming fees

Impact High

Complexity Low

Implementation Considerations

Ensuring that installations represent the widest possible demographics by working with local nonprofits, affinity groups, and cultural organizations to curate these opportunities

Clockwise, from top: FIGURE 4.23. Mark Reigelman, Stair Squares (2008), Brooklyn Borough Hall, Brooklyn, NY. FIGURE 4.24 Njaimeh Njie, The Village (2016–19) Pittsburgh, PA. FIGURES 4.25.–4.26 Mass Poetry, “Raining Poetry” (2016), Boston, Massachusetts. Rainworks, Seattle, Washington.

Exemplar images

The plinth on which the Christopher Columbus statue once stood remains in place today, as it is integrated into the south plaza’s overall design. Rather than remove the plinth, this site could be recontextualized as “The Platform” where all communities, identities, and forms of expression are celebrated and encouraged. The Platform can be a site for temporary projects ranging from site-specific dance, spoken word poetry, sculptural display, and more. Inviting local organizations, artists, and cultural leaders to activate this site would result in unique interventions that reclaim this space as a shared location for exchange, reflection, and empowerment.

Investment

Cost Considerations

A fixed budget to cover programming costs, materials, and honoraria, ranging from $4,000–$7,000 per intervention

Ongoing administrative costs, such as marketing materials, program coordination, etc.

Impact High

Complexity Low

Implementation Considerations

Ensuring that installations represent the widest possible demographics by working with local nonprofits, affinity groups, and cultural organizations to curate these opportunities

Clockwise, from left: FIGURE 4.27. Kelly Kristin Jones, Plinths for the People (2023). FIGURE 4.28. Antony Gormley, ONE & OTHER (2009). Trafalgar Square, London. Photograph by Matthew Andrews. FIGURE 4.29. Nick Selenitsch, Folly (2014), Edinburgh Gardens, Fitzroy North, Melbourne Australia. Installation view, Plinth Projects, April 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne.

Exemplar images

Permanent audio installation infrastructure would offer opportunities for soundscapes throughout the City Hall Campus. Soundscapes, or sonic art, offer limitless opportunities to immerse site visitors in an array of audio formats: oral histories, sound collages, musical performances, spoken poetry, and more. Soundscapes can offer a deeply enriching experiential element that allow people to connect with the city’s history and culture on a unique sensory level. With its heavy foot traffic, wide plaza, and history as the site of the former Christopher Columbus statue, the South-facing plaza is an opportunity-filled space for a public artwork that is ambient and soulful, rather than fixed and physical.

Investment

Cost Considerations

$150,000–$500,000+

Ongoing maintenance costs, any related programming fees

Impact High Complexity High

Implementation Considerations

Speaker placement, sound bleed into public spaces; partnership with local and state-wide history organizations to support gathering oral histories, especially if artworks are commissioned

Clockwise, from top left: FIGURE 4.30. Christine Burgin and Max Neuhaus, Times Square-Sound Installation (1977), New York, NY. Photo by Rob Wilson (2002). FIGURE 4.31. Daily Tous Les Jours, Hello, Hello (2024), Cambridge, Ontario. FIGURE 4.32. Christopher Janney, Reach New York: Urban Musical Instrument (1996) at 34 Street-Herald Square, New York, NY. Photo by Gregory Heisler. FIGURE 4.33. Ronald van der Meijs, Sound Architecture 5-Bicycle Bells (2014), The Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden, Surrey, England. FIGURE 4.34. Kevin Beasley, Who’s Afraid to Listen to Red, Black and Green? (2016), Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Exemplar images

PUBLIC SPACE

• Honorific and memorial spaces

• Former site of Christopher Columbus statue

• Underutilized hardscape areas

• Grand ceremonial space for gathering

EXPERIENCE

• “Statement piece” of the campus

• Historically significant architecture

• Ceremonious, official characteristics

• Public face of the city, often in photos and national news reports

STATEMENT PIECE OF ARCHITECTURE

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

PUBLIC ART HERE SHOULD FEEL...

RESPONSIVE TO ITS ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS

VISUALLY INTERESTING FROM MULTIPLE VANTAGE POINTS

CONCEPTUAL AND THOUGHT-PROVOKING LIKE AN OUTWARD EXPRESSION OF THE CITY’S CHARACTER, COMPLEXITY, AND VALUES

THE COLUMN COMMISSION

Columns have traditionally been an architectural symbol of government and justice, though they have more recently been associated with officially sanctioned oppression. Through public art, grand columns can transcend both symbols to become sites for celebration and reconciliation, reflection and reverence. City Hall’s eight columns remain in place —a remnant of the abandoned plan to make its western elevation the centerpiece of a grand riverfront Civic Center — though the steps leading to this former main entrance were removed long ago. To honor the history and grandeur of these architectural features, and draw the public's attention back to them, a regularly rotating public art intervention can be employed. Many historic sites around the country, including major museums and civic institutions, have activated similar elements through contemporary art using non-harmful mediums, such as light installations and vinyl wraps. The columns at City Hall could come to serve as canvases for highly inventive temporary public art projects that appeal to both local and national sensibilities.

Investment

Cost Considerations

$200,000 per project, with a $30,000 fixed artist fee out of this budget

Ongoing program operating costs (marketing, administration, coordination, etc.); a fixed budget for fabrication and artist stipends should be considered

Impact High

Complexity High

Implementation Considerations

Offering mentorship opportunities for Central Ohio-based artists led by the selected artist, for both fabrication and installation; offering adjacent programming opportunities for youth or emerging artists; rotating the Commission every two years

Clockwise, from top: FIGURE 4.35 Daniel Buren, Les Deux Plateaux (1985–1986), Palais-Royal, Paris, France. FIGURE 4.36. Jeff Dobrow, Brighter Together (2021), University of Virginia. Photo by Sanjay Suchak. FIGURE 4.37. Dan Perjovsch, Anti-War Drawings (2022), Documenta 15, Kassel, Germany. FIGURE 4.38. Nairy Baghramian, Scratching the Back (2023). Photography by Bruce Schwarz/courtesy the artist, Kurimanzutto, and Marian Goodman Gallery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

Exemplar images

Whereas once pubic art was designed to be static and remain installed indefinitely, today artists have many more options for siting their art and creating highimpact temporary experiences. This section outlines some of the options to activate City Hall Campus, and specific sites for temporary or permanent installations.

Temporary art interventions, whereby a piece is on display anywhere from 3 to 24 months, are a growing trend in the public art sphere. Short-term art installations allow a space to remain nimble and responsive to cultural conversations as they unfold in real time, and compressed presentation windows encourage deep engagement with these conversations while the art is available. Without the expectation that they must be maintained for many years, cities have fewer maintenance responsibilities and artists are free to experiment with different forms and materials than they otherwise would. Curating an ongoing series of temporary art exhibitions therefore enables unique, constantly evolving arts experiences — and sustained community interest in the spaces containing them.

Rotating art is a type of temporary art in which the exhibit site is fixed and the public art it features rotates at routine intervals (whereas temporary or short-term art may be exhibited at various sites throughout a space). A fixed site, which might include, for example, a bridge pillar or utility box, tends to have more constraints than the myriad options at a space like City Hall Campus, but can nevertheless be activated in interesting ways that change over time.

Long-term and permanent public art invites reflection about the city’s long-term goals for its public spaces, and how it can represent the widest range of values, identities, and narratives. Because permanent public art is a significant financial investment, artists should consult a fine art conservator to ensure that the artwork is designed using materials that are most appropriate for outdoor placement and public interaction. Sites for such projects should be carefully selected for maximum public visibility, contextual specificity, and artwork protection. In addition, site improvements may be included in the artist’s or team’s scope of work, in order to maximize the public experience of their art. While the complexity and risk associated with investing in long-term and permanent art projects can be substantial, their impact on a city's public art landscape can positively shape the community for generations to come.

City Hall Campus has many site features that frame and define the exterior public spaces, including walls, plazas, walkways, seating areas, shade trees, and planting beds. These would be enhanced by public art interventions that complement them and bring fresh energy to the campus. Any site improvements would likely require coordinating permits between multiple city departments through the site compliance review process. If possible, such projects should avoid costly construction items such as utility modifications, new stormwater management facilities, or substantial new pavement areas or site walls. An upto-date site survey and a thorough review of city code would be helpful first steps in determining whether substantial upgrades are necessary, and what they might cost.

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

0' 40' 80' 1" = 80' N

A BRIDGE OF STORIES

BROAD ST BRIDGE PLATFORMS

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

POP-UP EXPERIENCE

IMMERSIVE AND SUSPENDED

POP-UP EXPERIENCE

CONTEMPLATIVE INSTALLATION

THE PLATFORM SOUTH STAIRCASE ACTIVATIONS

THE COLUMN COMMISSION

TEMPORARY INTERVENTION

PERMANENT INTERVENTION

TEMPORARY OR PERMANENT INTERVENTION

POP-UP EXPERIENCE

IMMERSIVE AND SUSPENDED

CONTEMPLATIVE INSTALLATIONS

CONCRETE INLAY

POP-UP EXPERIENCE

CONTEMPLATIVE INSTALLATION

SOUND INSTALLATION

THE PLATFORM

SOUTH STAIRCASE ACTIVATIONS

THE COLUMN COMMISSION

A BRIDGE OF STORIES

BROAD STREET BRIDGE PLATFORMS

Bringing this plan's vision to life calls for a dedicated team of experts who can facilitate substantial works of public art in high-profile civic spaces. This section broadly discusses the process to assemble this team and set them on the path to commissioning art pieces for City Hall Campus.

The following steps are recommended to ensure the process of implementing public art on Columbus City Hall Campus will be governed by sound and transparent policies and procedures.

1 2 3 4

IDENTIFY & CONVENE EXPERTS TO SERVE ON THE COLUMBUS CITY HALL CAMPUS ART ADVISORY COMMITTEE.

CREATE DOCUMENTS TO SUPPORT PUBLIC ART IMPLEMENTATION.

CREATE A WORK PLAN.

IDENTIFY ARTISTS & SELECT PROJECTS FOR IMPLEMENTATION.

A City Hall Campus Art Advisory Committee, composed of local and national leaders in the arts, design, landscape architecture, urban planning, historic preservation, and arts administration, should be established to:

• Create a work plan for campus public art investments

• Develop criteria for project applicants and the awarding of projects

• Connect with artists whose practices align with desired public art programming at City Hall

• Report public art–related expenditures to the city

• Support duties pertaining to collection management and stewardship

• Promote the Committee's activities and, when appropriate, solicit public feedback into them

• Provide curatorial direction for all public art interventions on City Hall Campus

• Act in an advisory capacity to the city in any matter pertaining to public art on City Hall’s campus

• Oversee a review of City Hall's interior art collection and plan for its maintenance and expansion

CREATE CORE DOCUMENTS TO SUPPORT THE INITIATIVE’S IMPLEMENTATION.

The following documents should be developed in consultation with city staff, in particular the City Attorney's Office:

• Loan agreement template

• Commission agreement template

• MOU template for art that may be displayed at sites outside of City Hall

• Invitational Request for Proposals (RFP) template

Any art on City Hall Campus would be governed by the city’s public art and purchasing policies, as well as any others that apply.

The City Hall Campus Art Advisory Committee should develop a strategy for the $1.5 million dedicated to public art at Columbus City Hall that identifies:

• Project locations

• Implementation timelines

• Project budgets

• Project themes and goals

• Any partnerships, alternative funding opportunities, and/or special project considerations

• Necessary feasibility studies for artwork sites, possible projects, and programs

The plan and progress towards its implementation should be presented to the appropriate entities within the city on a regular basis.

The City Hall Campus Art Advisory Committee should procure art projects and commissions through an invitational RFP process that welcomes local and national artists. RFP materials should provide this plan and the following curatorial statement, which synthesizes the vision and goals for art on City Hall’s campus:

Columbus' City Hall is an active public space reflecting residents' shared civic values with temporary and permanent public art and placemaking elements that foster belonging, honor complex histories, and invite exploration. The artworks featured on City Hall Campus are intended to animate underutilized spaces, respond to the building's historic architecture, engage with the past, engender conversation, and create connections across all who have called this place home.

Book 6 of the Reimagining Columbus Final Report provides the City of Columbus with a guide to facilitate the next phase of this work — a process to acquire art for City Hall's campus that replaces the Columbus statue and adds new types of experiences for people to enjoy. Through activating its exterior spaces with art that reflects all city residents, Columbus harks back to the planners of 1908 who envisioned the grounds of City Hall as a grand civic plaza and responds to recent calls by Reimagining Columbus participants for public spaces in which to remember, heal, celebrate, and connect. Weaving together these strands of history allows Columbus an opportunity to expand City Hall's functional and symbolic roles in the community.

The ten interventions within this plan are intended to draw people in to experience City Hall in a new way. Outside of official business, people who pass by City Hall Campus today mostly do so without stopping. The site offers little to experience, few places to sit, and no one to interact with. The Ohio Statehouse, just blocks away and more centrally located, it is more often where people go to eat their lunch, enjoy an event, or attend a protest or rally. Art installations will invite people to visit City Hall to learn, to interact with others, to be inspired. They will transform the grounds of City Hall into a place where people experience feeling connected to and welcomed by the city — a first step to their civic participation. A legacy of Reimagining Columbus will thereby be a place more engaged and connected than ever before.

1 Report of the Columbus Plan Commission, 1908, p. 6.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., p. 7.

4 Report of the Columbus Plan Commission, 1908, p. 10.

5 Ibid. p. 52.

6 City Council Resolution adopted 11/13/22.

7 The Architects’ Journal. August 1, 1928, p.150.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid. p. 185

10 Ibid. August 15, 1928, p. 234.

Chapter 1: The History of City Hall

FIGURE 1.0. “The City Hall, South Capitol Square,” in Centennial History of Columbus and Franklin County by S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1909; last modified November 25, 2021. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/ohio/id/21665/rec/18

FIGURE 1.1. “Columbus City Hall and old Post Office Building,” c.1936–1943; last modified February 22, 2018. https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/p267401coll34/id/914

FIGURE 1.2. Riches, William. Central Market 1873. Engraving. In Columbus, Ohio, by Jacob Studer; last modified November 25, 2021. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/ohio/id/11626/rec/2

FIGURE 1.3. Howe, Henry. Ohio Penitentiary and Scioto River. 1856. Engraving. In Goodale Park Centennial, 1851–1951, published by Columbus Division of Parks & Forestry, 1951; last modified January 5, 2022. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/ohio/id/20191/ rec/8

FIGURE 1.4. “Ohio State Arsenal.” 1861–1870; last modified January 5, 2022. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/ohio/ id/10524/rec/3

FIGURE 1.5. Rager, Dean. “City Hall model photograph,” in Columbus This Week 3, no. 5 (October 31, 1926); last modified December 23, 2021. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/ohio/id/12237/rec/22

FIGURES 1.6.–1.8 Sources unknown.

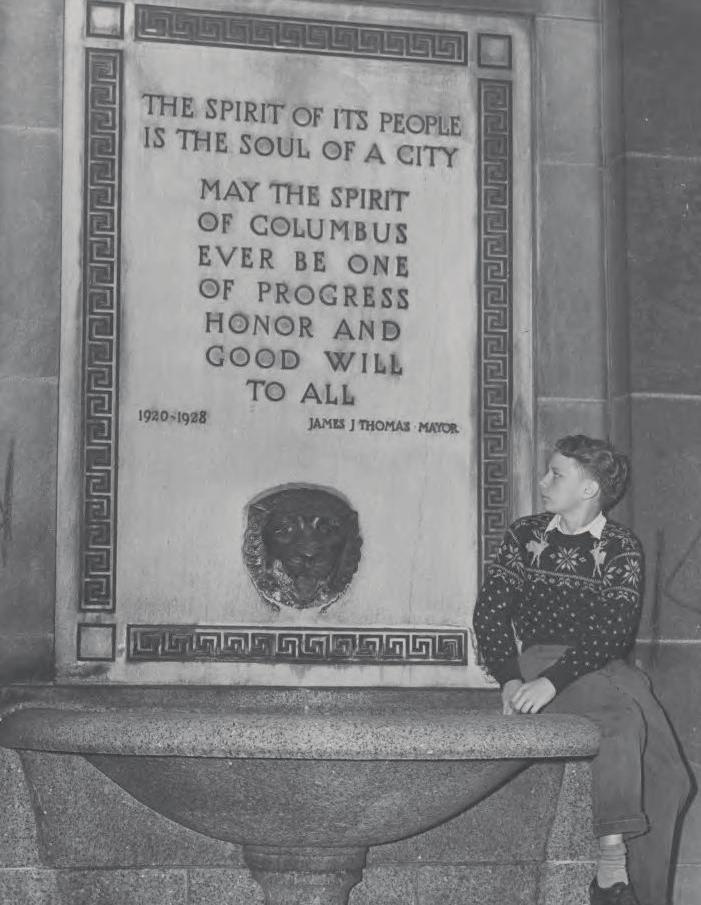

FIGURE 1.9. “Plaque at Columbus City Hall,” in Columbus Citizen Journal (September 3, 1945). https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/p16802coll7/id/24690/rec/9

FIGURE 1.10. Source unknown.

FIGURE 2.0. Photo by NormanB (2012). https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_York_-_National_September_11_Memorial_South_Pool_-_ April_2012_-_9693C.jpg

FIGURE 4.0. Columbus Dispatch (1959). https:// www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/local/2020/06/13/photos-christopher-columbus-statues-in/65896288007/

FIGURE 4.1. Sui Park, Summer Vibe (2021), Riverside Park, New York, NY https://suipark.com/ SUMMER-VIBE

FIGURE 4.2. CHIAOZZA, Lumpy Notes (2021), Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts https://www.eternitystew.com/Lumpy-Notes

FIGURE 4.3. Rachel B. Hayes, Horizon Drift (2024), Denver, Colorado. Provided by Black Cube. https://www.denverpost.com/2024/08/12/ denver-public-art-horizon-drift-rachel-hayes/

FIGURE 4.4. Daniel Buren, Photo-souvenir: The Garlands, work in situ (third version), 1982–2019, The High Line, New York, NY. Part of En Plein Air. A High Line Commission. On view April 2019–March 2020. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy the High Line. https://www.westsidespirit.com/cityarts/high-art-on-the-high-line-YK804537

FIGURE 4.5. Teresita Fernandez, Fata Morgana, (2015–2016). Photo by Elisabeth Bernstein. https://www.designboom.com/art/teresita-fernandez-fata-morgana-mirror-mirage-above-madison-square-park-06-01-2015/

FIGURE 4.6. Janet Echelman, Current, 2023–2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Current,_Columbus,_OH,_2023_By_Janet_Echelman.jpg

FIGURE 4.7. April Banks, A Resurrection in Four Stanzas (2021). https://publicartarchive.org/art/AResurrection-in-Four-Stanzas/d0d0fbda

FIGURE 4.8. Rachel B. Hayes, Round the Bend (2023). https://www.rachelbhayes.com/exhibitions

FIGURE 4.9. Rachel Hsu, The Weight of Our Living (2024). Photo by Constance Mensh, Courtesy of Association for Public Art. https://www. theartblog.org/2024/09/rachel-hsus-art-on-theparkway-invites-contemplation-of-tendernessthe-body-community/

FIGURE 4.10. Jenny Kendler, Mending Wall (2022), Chicago, Illinois. Photo courtesy the artist. Highland Park, Brooklyn, NY. https://jennykendler. com/artwork/5046146-Mending%20Wall.html

FIGURE 4.11. Daekwon Park, “At the site of the installation Immersive Cloud, by assistant professor of architecture Daekwon Park, students focused on a theme of reflection.” Photo by Akshara Raman. https://www.syracuse.edu/stories/architecture-students-connect-photography/

FIGURE 4.12. Ryah Christensen, Reflections on the Brazos (2015), Austin, Texas. https://publicartarchive.org/art/Reflections-on-the-Brazos/ eba54a28

FIGURE 4.13. Dan Snyder, Listen to the Fish, (2003). https://publicartarchive.org/art/Listen-tothe-Fish/99d01a93

FIGURE 4.14. Unknown artwork, Pike Place Market, Seattle, Washington. https://www.schcounselor.com/2011/07/i-have-always-known-that-atlast-i.html

FIGURE 4.15. Esther Shalev-Gerz, The Shadow (2018). Photo by Robert Keziere. https:// slash-paris.com/fr/evenements/esther-shalevgerz-the-shadow-1

FIGURE 4.16. Kojo Kamau, “Long Street Cultural Wall” (2014). https://www.columbusmakesart.com/ place/8891-long-street-cultural-wall

FIGURE 4.17. Boris Stroujko, Shutterstock (2020), Lucerne, Switzerland. https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/lucerne-city-switzerland-view-jesuit-church-1769416778

FIGURE 4.18. Rachel Hayes, Columbus, Georgia 2014. https://www.rachelbhayes.com/works

FIGURE 4.19. Rachel Whiteread, Monument (2023), Trafalgar Square, London. Image ©Rachel Whiteread, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, London. Photo by Michael Crimmin / Greater London Authority. https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront. net/w1200h1200/collection/PUBSCULPT/WC2/ WC2_FPC_S003-001.jpg

FIGURE 4.20. Meg Whiteford, "The Making of Simone Leigh’s Brick House." Simone Leigh, Brick House, 2019 ©Simone Leigh. Photo by Timothy Schenck.https://www.hauserwirth.com/ursula/28500-making-simone-leighs-brick-house/

FIGURE 4.21. Pamela Rosenkranz, Old Tree, (2023–24). Adobe Stock Photo.

FIGURE 4.22. Samson Kambalu, Antelope (2022). https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/28/samson-kambalu-antelope-fourth-plinth-trafalgar-square-london

FIGURE 4.23. Mark Reigelman, Stair Squares, (2018). https://culturalfluency.info/portfolio/ mark-reigelman/

FIGURE 4.24. Njaimeh Njie, The Village (2016–19). https://pahumanities.org/conversations/2021/10/26/grantee-spotlight-office-ofpublic-art-pittsburgh/

FIGURE 4.25.–4.26. Mass Poetry, Raining Poetry (2016). https://www.bostonmagazine. com/2016/05/19/invisible-poems-hidden-boston-sidewalks/

FIGURE 4.27. Kelly Kristin Jones, Plinths for the People (2023). Photo by Mariah Karson. https:// www.kellykristinjones.com/plinths-for-the-people

FIGURE 4.28. Antony Gormley, ONE & OTHER, (2009). Photograph by Matthew Andrews. https://www.artichoke.uk.com/antony-gormley-interview-10-years-since-one/

FIGURE 4.29. Nick Selenitsch, Folly (2014), Edinburgh Gardens, Fitzroy North, Melbourne Australia. Installation view, Plinth Projects, April 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne. https://plinthprojects.com/about

FIGURE 4.30. Christopher Janney, Reach New York, An Urban Musical Instrument (1996). https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/gig-alerts/

episodes/christopher-janney-reach-new-york34th-streetherald-square-subway-station

FIGURE 4.31. Daily Tous Les Jours, Hello, Hello, (2024). https://archello.com/project/hello-helloa-giant-interactive-arch-to-greet

FIGURE 4.32. Christine Burgin and Max Neuhaus, Times Square- Sound Installation (Installed 1977). Photo by Rob Wilson (2002). https://culturenow.org/site/times-square---sound-installation

FIGURE 4.33. Ronald van der Meijs, Sound Architecture 5 (2014). https://wonderlicious. blog/2023/10/23/nature-inspired-soundwalks-in-europe/

FIGURE 4.34. Kevin Beasley, Who’s afraid to Listen to Red, Black and Green?, (2016). https://www. studiomuseum.org/magazine/harlem-art-walk-tour

FIGURE 4.35. Daniel Buren, Les Deux Plateaux (1985–1986), Palais-Royal, Paris, France. https:// www.roselinde.me/paris-colonnes-de-buren/

FIGURE 4.36. Jeff Dobrow, Brighter Together (2021). Photo by Sanjay Suchak. https://news.virginia.edu/content/bright-spot-look-back-springsemesters-pop-shows

FIGURE 4.37. Dan Perjovsch, Anti-War Drawings (2022), Documenta 15, Kassel, Germany. Photo by Felix Schmitt for The New York Times. https://www. nytimes.com/2022/06/10/arts/design/documenta-ruangrupa.html

FIGURE 4.38. Nairy Baghramian, Scratching the Back (2023). Photography by Bruce Schwarz/ courtesy the artist, Kurimanzutto, and Marian Goodman Gallery. https://www.surfacemag.com/ articles/nairy-baghramian-met-museum-facade/#