Over the course of six books, this report fully details the activities and outcomes of the Reimagining Columbus project, through which the City of Columbus, Ohio reckoned with its relationship to the explorer Christopher Columbus.

THE SIX BOOKS IN THIS SERIES INCLUDE:

BOOK # 1

provides insights into how the City of Columbus came to display a Christopher Columbus statue on the grounds of its City Hall, why that statue was removed in 2020, and how the Reimagining Columbus project was designed to help the city determine what to do with it going forward.

BOOK # 2

describes research the project team undertook to discover the many stories that have played out among the people of Columbus, Ohio since long before it became a city, the truth of Christopher Columbus and his conduct in the New World, and how an explorer who never reached the United States became a symbol of all its promise.

BOOK # 3

outlines the community engagement methodologies employed throughout this project and chronicles the events and activities offered by the Reimagining Columbus project team, as well as findings from these conversations.

BOOK # 4

connects the project team’s research findings and community engagement results to the design principles that informed concepts for a new space in which residents might one day experience the reinstalled Christopher Columbus statue.

BOOK # 5

applies the design principles developed from research and community conversations, and best practices in placemaking, to articulate how a new statue site should look and feel, how visitors should be able to interact with it, and how it could engender profound experiences that reverberate for generations.

BOOK # 6

offers an Art Plan for City Hall Campus to guide the implementation of future public artworks there.

Reimagining Columbus is funded by the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project, a multi-year commitment aimed at transforming the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented.

In order to confidently recommend a course of action regarding the City of Columbus’ Christopher Columbus statue, the Reimagining Columbus project team felt it was important to be grounded in truths about the explorer and his legacies, particularly those within Columbus, Ohio. While universal agreement on these topics may never be achieved, the team engaged in a good-faith effort to research and accurately represent facts regarding five key topics:

The team traced multiple histories dating to well before this land was decreed Ohio's state capital in 1812, centered on the Indigenous, Black, and Italian peoples who have been most affected by the city’s Christopher Columbus statue.

The team uncovered contemporaneous, historical, and modern accounts of Columbus and his conduct in the Caribbean.

The team sought to understand why an explorer with no direct ties to the United States became such a prominent figure here.

The team looked into the myriad ways Christopher Columbus has presented within the City of Columbus, Ohio since its founding in the year 1812.

The team learned about the history and artistry of the city’s Christopher Columbus statue and sought design inspiration for a possible new installation site. See the website for an essay by Matteo Foshessati, Curator at the Wolfsonia in Genoa, Italy, about the statue and its sculptor.

Book 2 describes Reimagining Columbus’ research activities and summarizes its findings, as well as the learning exchanges it offered to the public. Though it is presented in linear fashion here, in practice the team’s research process was circular, with topics being investigated and revisited throughout the two-year project period. Learnings from subject matter experts, museums and site tours, original research, community conversations, and arts and culture colleagues nationwide were used to educate the public and inform project deliverables. This information was augmented by feedback from the project's community engagement process, which elicited community members’ “overlooked histories” to present a more complete accounting of this statue and what it means to current Columbus, Ohio residents.

• Community members had numerous opportunities to learn from the project team’s research into various topics pertaining to Christopher Columbus, the City of Columbus, the Columbus statue, design inspiration for a new statue, and more; original content developed by the team remains available to provoke ongoing conversation.

• Those most impacted by the Christopher Columbus statue conversation — the city’s Indigenous, Black, and Italian-American community members — have experienced radically divergent trajectories during their time on this land now called Columbus, Ohio.

• While Columbus the explorer has been lauded for his seamanship, bravery, and religious zeal, for the most part modern historians and contemporaneous documentarians agree that his conduct in the Caribbean was deplorable.

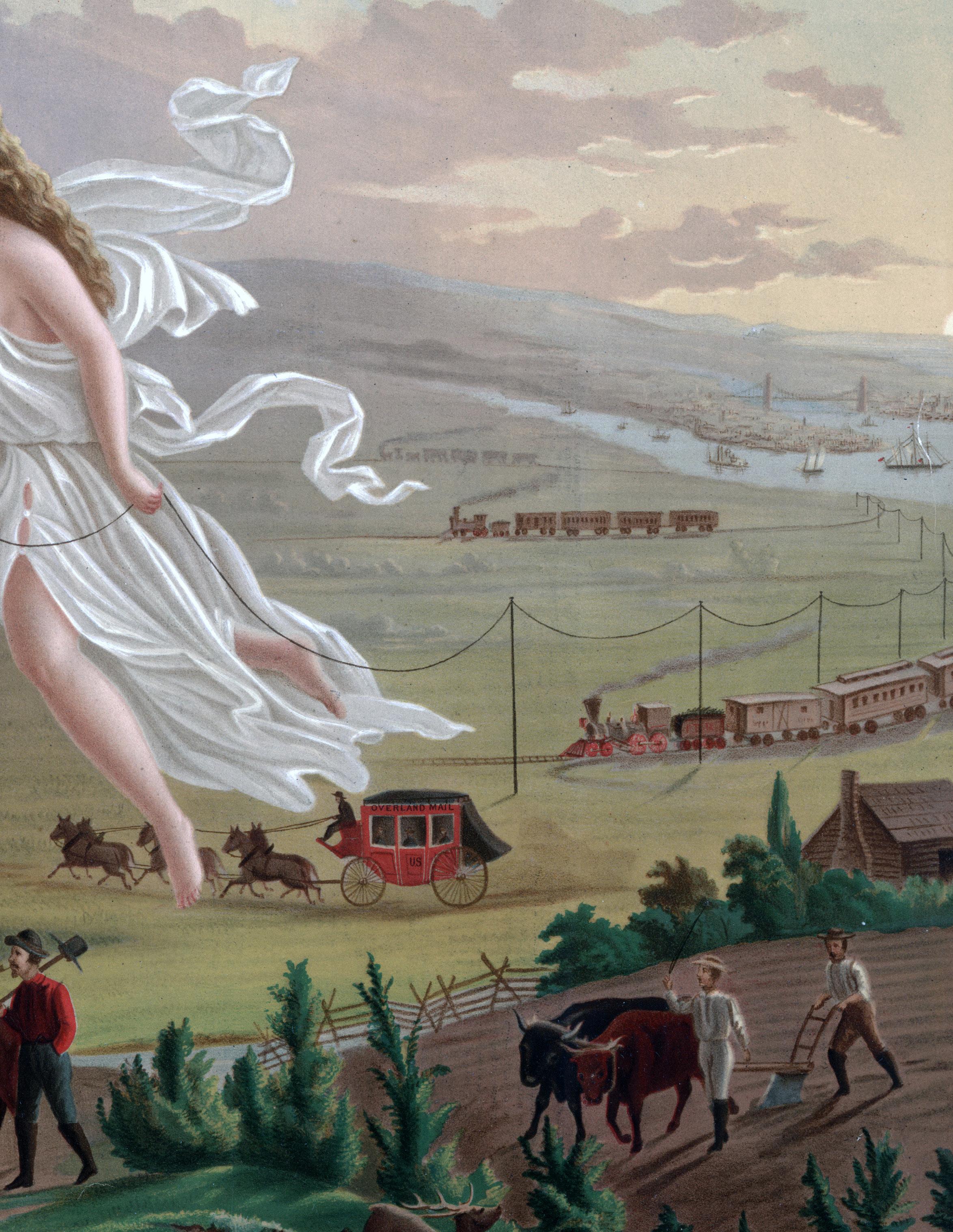

• In early American history, Christopher Columbus was adopted as a symbol of the nation’s righteousness, to the point that a feminized “Columbia” figure personified the fledgling country itself — and ItalianAmericans who sought to be accepted in the United States had much to gain from claiming him as their own.

• Since its founding in 1812, the City of Columbus has been inextricably tied to the explorer Christopher Columbus, and there have been many tangible manifestations of him throughout the city since.

The project team explored many avenues to uncover the truth about Columbus and the extent of his influence in modern America. This section outlines the types of questions that were asked during this project’s research process, and the types of activities employed to answer them; it further links to all the original content developed through the project.

The methods on the following page were used to gather insights with which to educate the public and inform the Reimagining Columbus project deliverables around questions such as:

• Who were the people who settled in this place?

• Why did they come here, and what happened to them after they arrived?

• How have these experiences shaped their current realities?

• What are the modern understandings of Columbus’ voyages and his activities in the Caribbean?

• Why was the City of Columbus named Columbus?

• What tangible and intangible marks have the explorer made on this city?

• Why has a person with no connection to America become so prevalent in the American imagination?

• What has Columbus represented to various groups over time?

• How is the Columbus statue to be understood as a piece of public art?

• How have other cities dealt with their Columbus statues?

• What are some innovative ways to tell complicated histories in public space?

• What can we learn from Indigenous design principles to inform a possible new statue site?

The team included many subject matter experts and consulted with others on topics including art history, City of Columbus history, Indigenous history and design, racial justice, urban planning, exhibit design, landscape architecture, and immigration. Some were invited to share their expertise with community members at special public events.

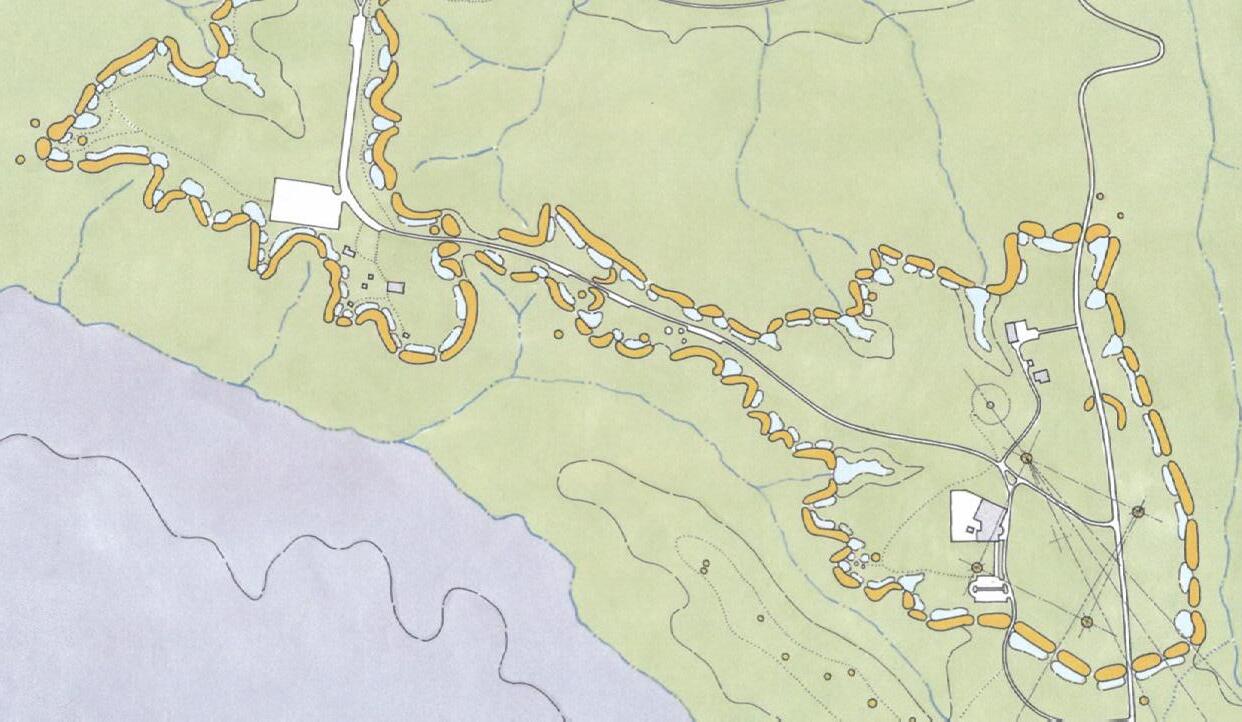

Team members toured the art and architecture of Columbus City Hall and the Ohio Statehouse, as well as the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. The project’s Indigenous Knowledge Consultant, a member of the Lakota tribe, led tours of Highbanks Adena Mound and Voss Mound in Columbus, while a Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks historian led a tour of the Great Circle Earthworks, a recently designated UNESCO World Heritage site in Newark, Ohio.

The team conducted research into various topics to educate themselves and the general public about issues central to project themes and outcomes.

The team invited city leaders and members of Columbus’ Black, Indigenous, and Italian-American communities to share their personal experiences in intimate conversations that were filmed and made publicly accessible online.

Team members attended the Monument Lab Summit in Philadelphia and engaged in year-round conversations with members of the Monuments Project Cities Network (i.e., other municipalities that also received funding to address contested monuments).

STORY MAP | Explore the Events. Local historian Nancy Recchie and Urban Planner Jasmine Metcalf created an interactive timeline of key events in the history of Central Ohio from prehistory to modern times.

VIDEO | Talking Circle Part 1: Unveiling the Indigenous Talking Circle Tradition. Dr. Shannon Gonzales-Miller of The Ohio State University joined Indigenous community members to explore the complexities of historical storytelling, highlighting the overlooked narratives of survival and secrecy that have shaped Indigenous experiences.

VIDEO | Talking Circle Part 2: Exploring Indigenous Issues of Today. Dr. Gonzales-Miller and community members continued their conversation from Part 1 by connecting Indigenous histories to their present-day struggles.

VIDEO | Migration, Immigration, and the Growth of Columbus. Dr. Jason Reese of The Ohio State University described how migration and immigration impacted the City of Columbus throughout the 20th century.

VIDEO | A Legacy of Faith, Food, and Family: Columbus Italians. Members of Columbus’ ItalianAmerican community shared their history, traditions, families, struggles, and triumphs, and how these experiences have shaped both them and the city.

VIDEO | Voices of Change in 2020. Black Lives Matter activists offered insights into their movement and the protests of 2020, as well as the statue and what should be done with it.

VIDEO | Recent Discovery Sheds Light on Legacy of Christopher Columbus. Law Professor Pablo Gutíerrez Vega of the University of Seville, Spain used historical documents to challenge traditional narratives of Christopher Columbus.

WHITE PAPER | Beyond Discovery: Uncovering the Motives and Consequences of Columbus' Voyages. Historian Cristina Benedetti, PhD and Urban Planner Josh Lapp uncovered the explorer’s historical context, motivations, and impacts in a paper detailing current scholarship into the subject.

VIDEO | Columbus in the American Imagination and Q&A Session. Dr. Kirk “Monuments Man” Savage of the University of Pittsburgh delivered a public lecture on why Columbus resonated in the American colonies.

VIDEO | The Statue and its Presence in Columbus: Part 1. Columbus leaders Jennifer Fenig, Deputy Chief of Staff to Columbus Mayor Andrew J. Ginther; Jason Jenkins, Chief Diversity Officer & Executive Director, Office of Diversity & Inclusion; and Ken Paul, Former Chief of Staff to Columbus Mayor Andrew J. Ginther (through 2023) — discussed how and why the statue came down in 2020, and what that makes possible for the city going forward.

VIDEO | The Statue and its Presence in Columbus: Part 2. Members of the Columbus Art Commission — Merjin Vanderheijden, Chair; Diane Nance, Former Chair; and Eliza Ho, Member — discussed their process to weigh what should be done about the city’s Columbus statue.

VIDEO | The Arc of Columbus: A City’s Journey with its History and Namesake and Community Discussion. Key community stakeholders discussed their experiences vís-a-vís the Columbus statue and this city.

VIDEOS | Stories & Symbols of Columbus. Local historian Nancy Recchie led a tour of art and architecture in downtown Columbus for the project team, with a history lesson at key sites.

VIDEO | What is Indigenous Design? Architects Tamarah Begay and Jan Tifrea from Indigenous Design Studios + Architecture delivered a public lecture on Indigenous design practices.

REPORT | Toppling Columbus: The Fate of Christopher Columbus Statues in 13 U.S. Cities Since 2020. Urban Planner Meredith Reed compiled a report of how Columbus and 12 other U.S. cities have dealt with their Christopher Columbus statues.

VIDEO | The Future of Monuments Panel Discussion. Kendal Henry, Assistant Commissioner of Public Art at the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, moderated a conversation about the role of monuments in modern America with artists Sandy Williams IV, Melissa Mongiat, and Norman Lee, who are currently working to create, redefine, and contextualize them.

The following sections supplement takeaways from the above materials with original research into each topic. They are intended to provide brief overviews of information considered relevant to the development of Reimagining Columbus deliverables and are in no way exhaustive explorations of the subjects.

Humans have occupied the land now called Columbus, Ohio for at least 12,000 years. Each person who passed through here lived a story that reverberates to this day; legacies of their triumphs and traumas animate all who currently call this place home. This section offers a brief overview of this place, who came here and why, and how they fared after they arrived.

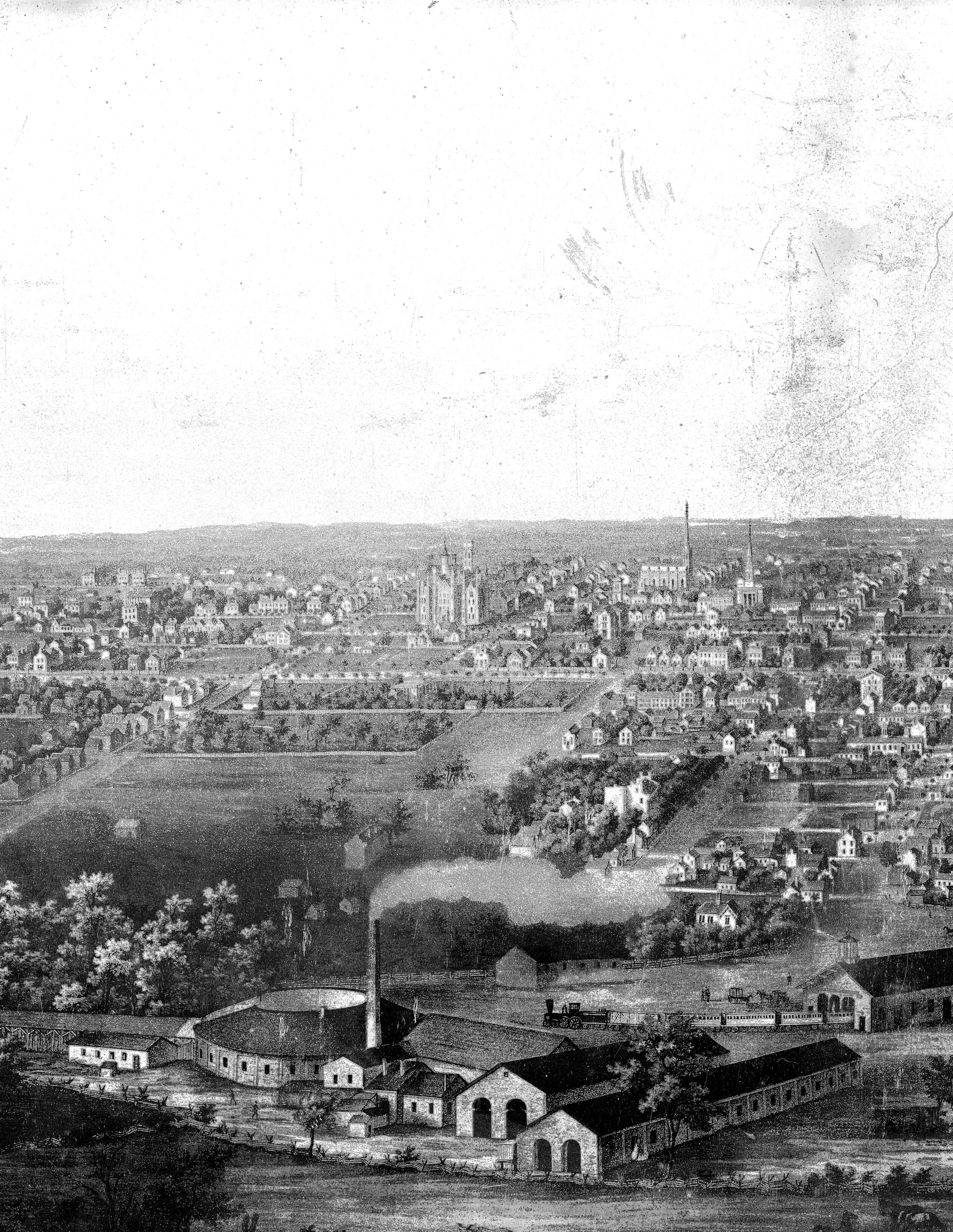

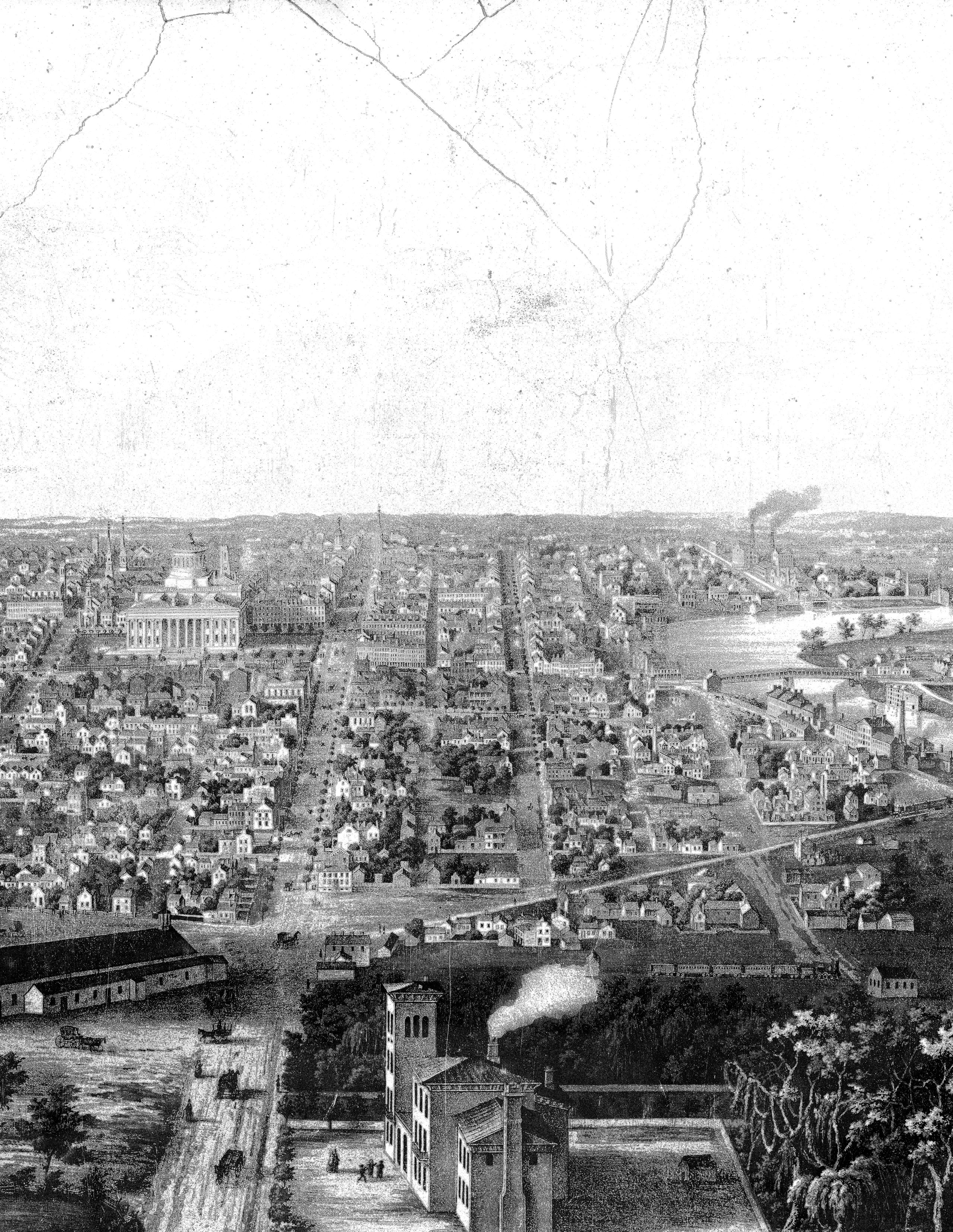

Ohio, meaning “great river” in Iroquois,1 entered the Union as the 17th state on February 19, 1803 with Chillicothe as its capital (1803–1810), followed by Zanesville (1810–1812); when political infighting rendered these sites unworkable, the Ohio Legislature began seeking a new, more permanent capital. The City of Columbus dates to 1812, when the General Assembly voted to establish Ohio’s capital in an altogether new town across the Scioto River from the town of Franklinton. The unoccupied, thickly forested site was chosen over already-established contenders nearby — including Dublin, Worthington, Zanesville, Delaware, and Chillicothe — on the strength of a bid featuring 10 acres of land and $50,000 towards the construction of state buildings that was assembled by several local land and business owners.2 Though this land in the middle of Ohio had no direct connection to Christopher Columbus, Ohio State Senator Joseph Foos was an admirer of the explorer and convinced his colleagues to name the city for him. On February 21, 1812 a resolution of the Ohio General Assembly thereby stated,

"That the town to be laid out at the Highbank, on the east side of the Scioto River, opposite the town of Franklinton, for the permanent seat of government, of this state, shall be known, and distinguished by the name of Columbus."3

As the forest was cleared to make way for a capital building and Columbus’ fledgling community combined efforts to remove tree stumps from High Street, Ohio found itself the western front in the War of 1812. Control of Lake Erie was paramount to ensure supply lines and allow troops to push into Canada, and William Henry Harrison, who commanded the Army of the Northwest, established headquarters in Franklinton to facilitate access to the state’s northern reaches. The influx of soldiers here and in nearby Columbus supported trade and contributed to infrastructure improvements that transformed these frontier towns into stable communities. Columbus was incorporated on February 10, 1816, and state legislators held their first meeting in the new statehouse on December 2 of that year.4

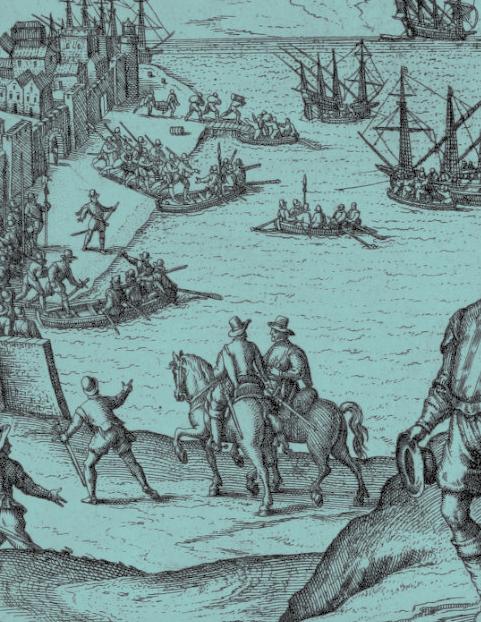

2.0. Palmatary, J. T., View of Columbus O. from Capitol University, (1867).

What is now Central Ohio has been home to a number of Indigenous civilizations dating at least 12,000 years.5 The abundance and significance of Indigenous earthworks in Central Ohio, including a new non-contiguous UNESCO World Heritage property called the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, suggests that this area was a thriving hub of Indigenous life in prehistoric and ancient times. By the mid-17th century, most of these so-called “Moundbuilders” had disappeared from the area, which then became home to tribes including the Shawnee, Mingo, Delaware, and Wyandot. By 1843, these tribes had been removed from Central Ohio,6 though some members remained at great personal sacrifice; approximately 2,500 Native Americans live in Columbus today (0.27% of the population).7

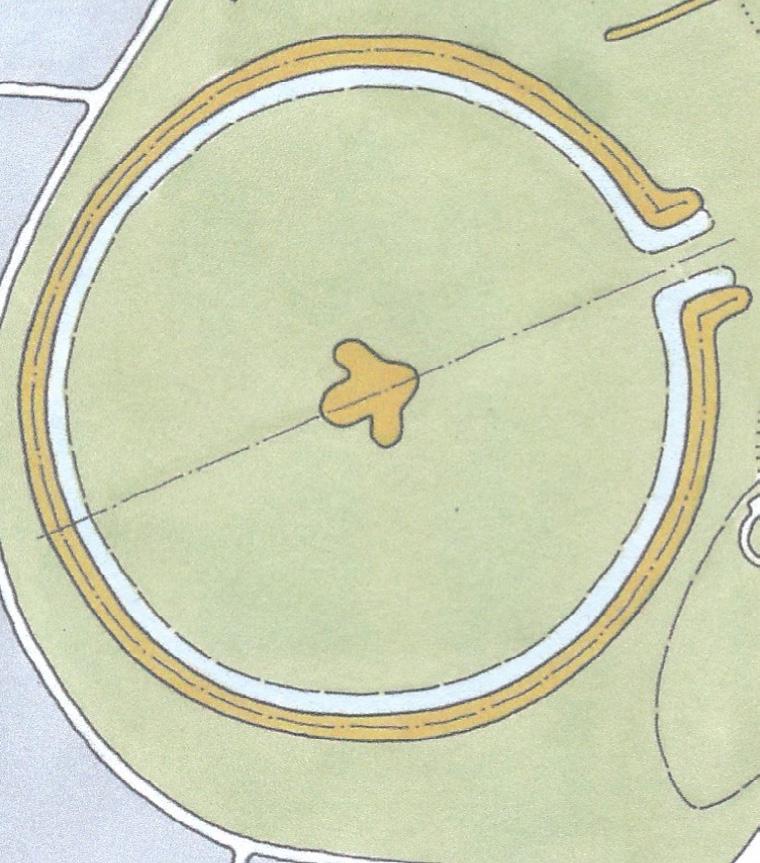

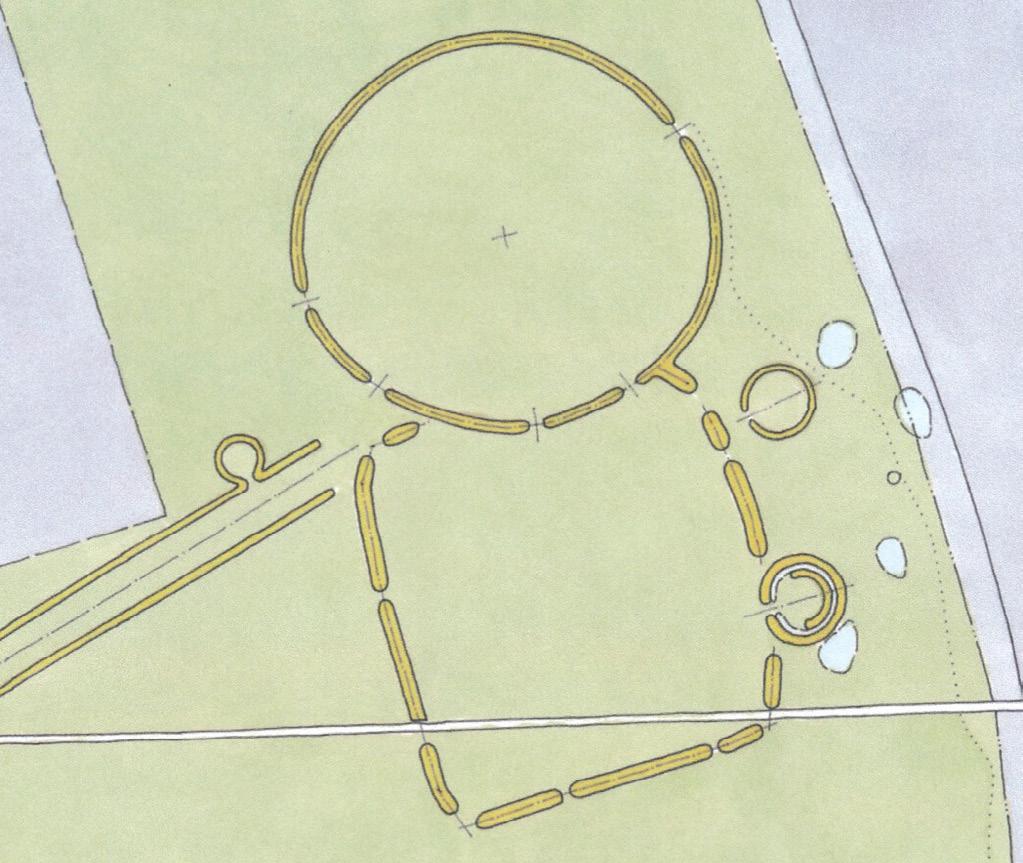

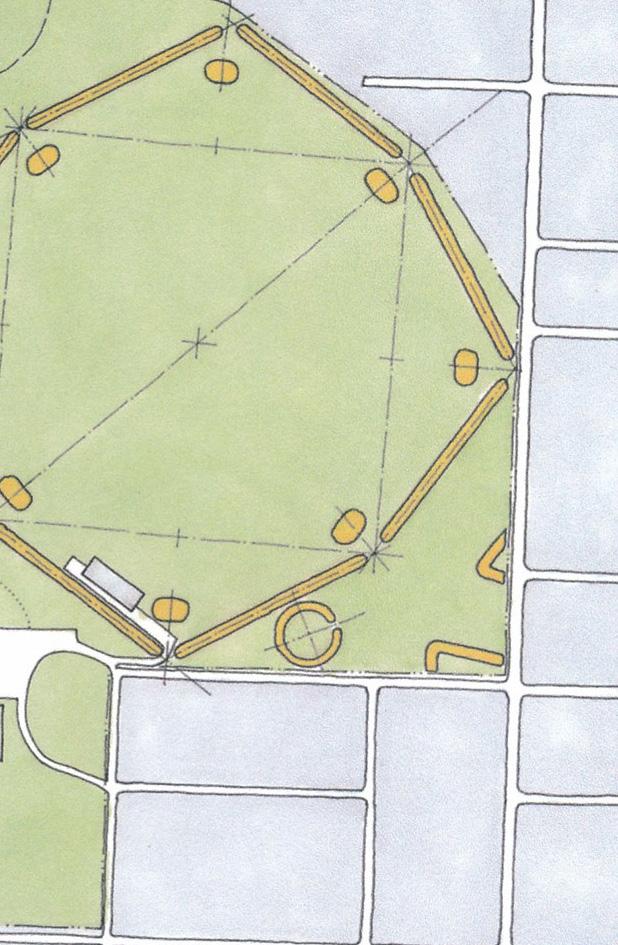

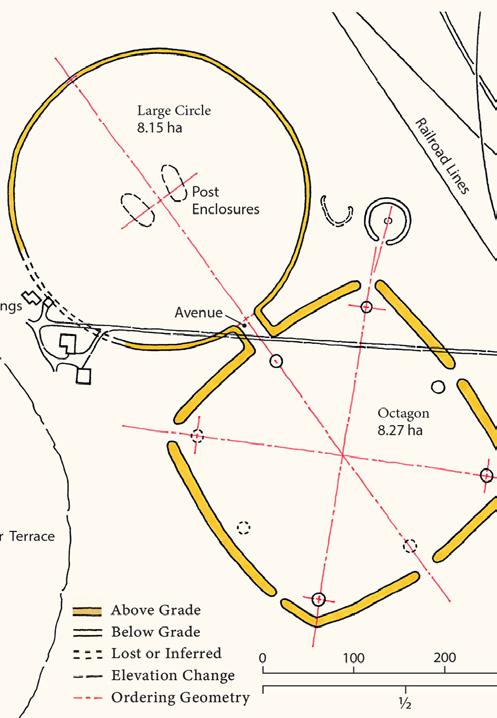

FIGURE 2.1.

From approximately 1,000 BCE to 1,650 CE, the Ohio Valley was populated by the Adena, Hopewell, and Fort Ancient civilizations,* who are best known today for their earthwork and moundbuilding traditions. Broadly speaking, the Adena created large, conical mounds in which to bury their important leaders;8 the Hopewell created sprawling geometric patterns that aligned with astrological phenomena;9 and the Fort Ancient peoples created effigy mounds (i.e., mounds in the shape of animals) for ceremonial purposes.10 For more than 1,500 years, the people of these sophisticated cultures discovered agricultural techniques, invented pottery, created art and music, traded extensively throughout the region and beyond, and lived peaceably. Their disappearance — before European settlers had arrived — is the subject of some debate, and may have been due to disease, migration, conflict, crop failure, and/or climate change.11

*The self-given names of these tribes are not known. The Adena were named by archaeologist William C. Mills in 1902 after his excavations of the Adena Plantation in Chillicothe. The Hopewell were named by Warren K. Moorehead, who excavated land owned by Modecai “Cloud” Hopewell in Chillicothe. The Fort Ancients were named because one of their villages was built near the Hopewell-era Fort Ancient site in Oregonia, Ohio.12

Above: FIGURE 2.3. Hopewell peregrine falcon effigy. Photo by Tom Engberg, National Parks Service. Right: Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks UNESCO sites. Ohio History Connection. Clockwise, from top left: FIGURE 2.4. Great Circle Earthworks. FIGURE 2.5. Hopeton Earthworks. FIGURE 2.6. Mound City. FIGURE 2.7. Seip Earthworks. FIGURE 2.8. Fort Ancient. FIGURE 2.9. High Bank Works. FIGURE 2.10. Hopewell Mound Group. FIGURE 2.11. Octagon Earthworks.

Many mounds were built on the land that is now Columbus, but most have been destroyed. Within today’s city limits, two are especially noteworthy:

This cone-shaped burial mound on McKinley Avenue in Columbus was built approximately 2,000 years ago by the Adena peoples. It measures 20 feet high and 100 feet in diameter, and is one of the last such remaining mounds within Columbus. Its name comes from the Shrum family, who donated it to the Ohio History Connection in 1928.13

The mound that early Columbus settlers encountered as they laid out a street grid for the new state capital in 1812 no longer exists, except in name. Mound Street in downtown Columbus was originally used to divert traffic around the massive 40-ft-high, 300-ft diameter mound that had stood there for hundreds of years. Its clay was used to make bricks for the original Ohio Statehouse (and repurposed for the new building after a fire in 1852) and other buildings until the 1830s, when the mound was removed to accommodate traffic in the growing city. 14

“One of the most pretentious mounds of the county was that which formerly occupied the crowning point of the highland on the eastern side of the Scioto River … on the southeast corner of Mound and High streets in Columbus. Not a trace of this work is left. … When the first settlers came, it was regarded as a wonder. Yet it was not spared. The expansion of the city demanded its demolition and therefore this grand relic of Ohio’s antiquity was swept away.”15

— James Linn Rogers (great-grandson of Franklinton founder Lucas Sullivant, 1888)

FIGURE 2.12. Right. Shrum Mound. Photo by Kevin Payravi (2016).

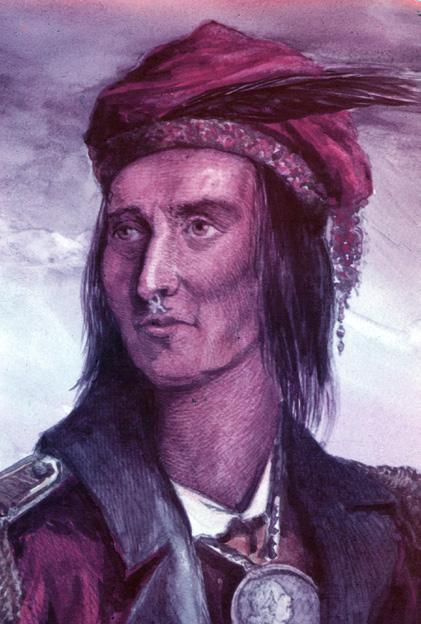

When European settlers began spreading westward in the early 18th century, Indigenous tribes retreated to the Ohio Country, a loosely defined area west of the Appalachian Mountains and South of Lake Erie. Here, they spent the next century defending their villages in near-constant battle with encroaching American colonists, as well as the British and French who were also competing for the territory. The Ohio Country officially became part of the United States via the Treaty of Paris 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War, affirmed U.S. sovereignty, and extended the western border of the United States to the Mississippi River. Nevertheless, the new territory remained contested. By the War of 1812, the Treaty of Greenville (1795) and the Treaty of Fort Industry (1805) had ceded much of Ohio from Native Americans to the Americans, but control of the land was elusive. 16 When Shawnee Chief Tecumseh, who attempted to create a Native American Confederacy of tribes to ward off American expansion, was killed at the Battle of the Thames, the position of White Settlers was solidified and Indigenous tribes were driven from the area. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 legalized the forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their land, and by 1840 few remained.17

“The whites are already nearly a match for us all united, and too strong for any one tribe alone to resist; so that unless we support one another with our collective and united forces; unless every tribe unanimously combines to give check to the ambition and avarice of the whites, they will soon conquer us apart and disunited, and we will be driven away from our native country and scattered as autumnal leaves before the wind.” 18

— Tecumseh (1811)

The small, pluralistic Indigenous community of Columbus today is a testament to the resilience of a people whose histories have been dominated by the pain of erasure; a defining characteristic of these groups today is their invisibility. In this place, where fewer than 0.3% of the population is Native American, Indigenous narratives are often omitted from official public discourse. And with stories untold, histories and lived experiences unknown or forgotten, some Indigenous community members have further retreated from mainstream culture in favor of their own traditions:

"I don’t look outside, in the rest of society, to who’s written the stories, because they’re not reflective of me and my culture. Instead what I do is — I live it. I create my own experiences…I don’t rely on the rest of society to tell me who I am and what life I lived and what my ancestors lived…I am teaching my daughters to not rely on whoever writes the books to tell them who they are.”19

— Shelly Corbin, Lakota tribe member

Many, however, continue to fight for inclusive public spaces of belonging and healing, feeling a responsibility to share what it took for their ancestors to survive. As they work to expose the secrets and tie together the disconnected narrative threads of their pasts, Indigenous communities look to their local leaders to take action in support of their existence and well-being — as opposed to empty acknowledgment of their ancient claims to this land.

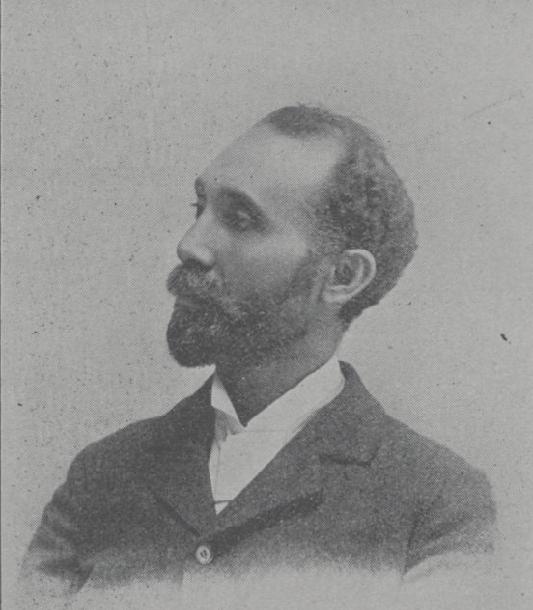

Left: FIGURE 2.13. Portrait of Tecumseh. Owen Staples (attributed, 1915), based on an engraving by Benson John Lossing (1868). FIGURE 2.14. Members of the Central Ohio Indigenous community on a hike. Photographer unknown (2025).

Columbus’ growth began slowly and then accelerated quickly as the city became a transportation and economic hub within Ohio. Twenty years on from its founding, Columbus was still a town of just 2,000 people. 20 When transportation infrastructure eventually linked Columbus to the rest of the country, its vibrant economy and plentiful manufacturing jobs attracted thousands of migrants and immigrants over the next several decades, growing the city to 125,560 by 1900. 21 After the turn of the century, groups from eastern and southern Europe, including Italians, Greeks, Russian Jews, Polish, and Hungarians, began arriving in the city to join the city’s established German and Irish populations. 22

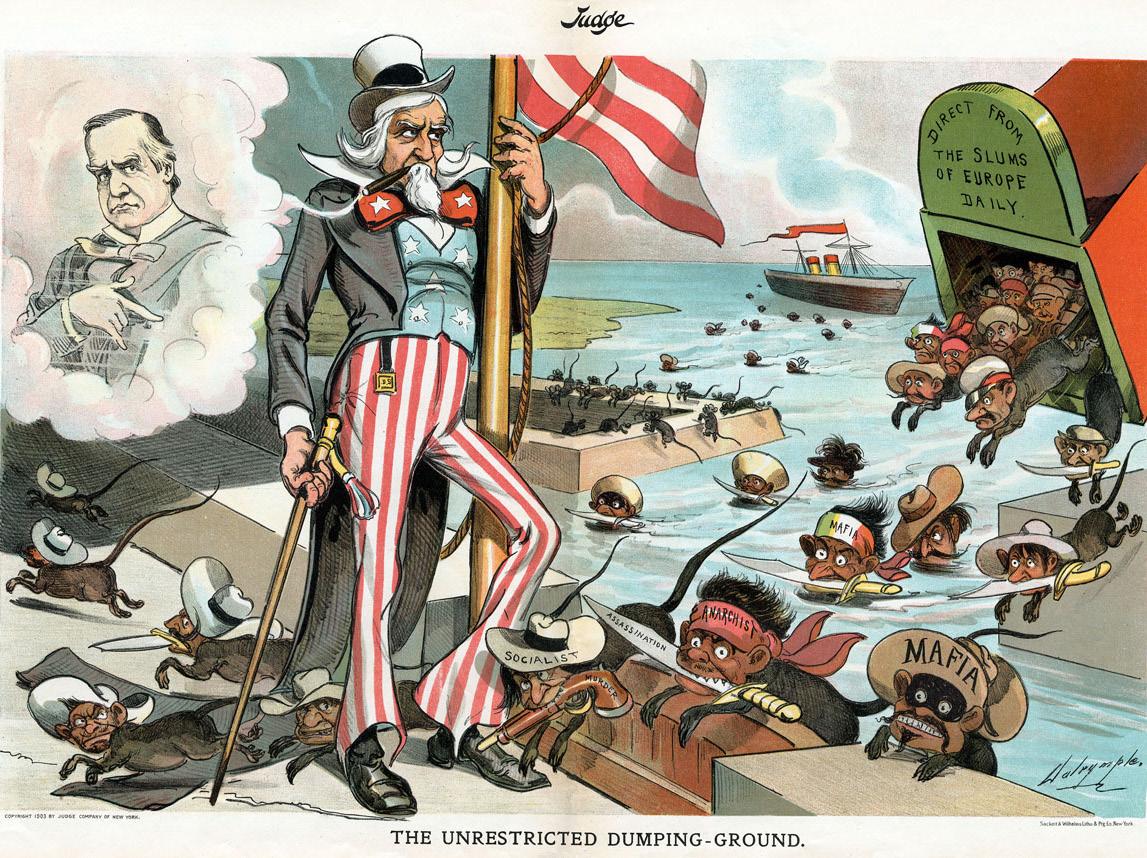

Italian immigration to the United States peaked from 1880 to 1920, when about 4 million Italians, mostly from Southern Italy, fled extreme poverty and disease for the chance of a better life in America. 23 These immigrants occupied a precarious position in American society — on paper, they were White, but their socialization with and acceptance of jobs formerly done by enslaved Black people, combined with their Catholicism, made them a social threat.24

“There has never been since New York was founded so low and ignorant a class among the immigrants who poured in here as the Southern Italians who have been crowding our docks during the past year.”25

— NY Times opinion article (1882)

For decades upon their arrival in the United States, Italians experienced extraordinary levels of discrimination that even threatened U.S. diplomatic relations with Italy. The first federal holiday honoring Christopher Columbus in 1892 was, in part, an apology from President Benjamin Harrison to Italy for the treatment of Italians in America, particularly the lynchings that had occurred in New Orleans the year before.26

In New Orleans in 1891, a group of 19 Italians were charged with murdering the city’s police chief. When their cases fell apart for lack of evidence, a mob of 10,000 stormed the jail where the Italians were being held and killed 11 of them in the largest mass lynching in American history. Historians have cast doubt on whether these men were responsible for the crime; regardless, this incident inflamed prejudices that had already taken hold in the United States. All Italian-Americans were thereafter tied to a supposed secret society of criminals called “the Mafia” — a harmful stereotype, reinforced by hundreds of Hollywood films and television shows, that persists to this day.

27

In the 1920s, the KKK became deeply embedded in Indiana and Ohio, where new leadership expanded its mission to include discrimination against and intimidation of the Jews, immigrants, and Catholics they claimed were responsible for the “national decline.”28 Ohio was home to approximately 450,000 Klan members at the time; 29 the largest Klan rally in Ohio history occurred just 30 miles east of Columbus in Buckeye Lake, where 75,000 “Ohio State Klonklave” members gathered in 1923. 30

World War II ushered in a new era of hardship for Italian Americans. President Roosevelt’s Proclamation 2527 — Alien Enemies, Italian (1941) declared ”all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of” Italy, a hostile nation allied with Axis powers against the United States, ”alien enemies” subject to apprehension, restraint, and removal.31

Subsequent proclamations set curfews for Italians, required them to register with local government, restricted their movements, monitored their communications, confiscated their property, and relocated or interred many. 32 Italian Americans felt forced to choose between their new life in the United States and their family back home in wartorn Italy, with the strength of those relationships being viewed skeptically by Americans and the government.33 Eventually, President Roosevelt realized he would need the support of Italians for his planned invasion of Italy, and the proclamations against them were lifted on Columbus Day 1942. Many then jumped at the chance to prove their loyalty through displays of patriotism and courageous military service.34

Clockwise, from top left: FIGURE 2.16. A depiction of the 1891 lynching of Italian prisoners in New Orleans. Benjamin E. Andrews (1912). FIGURE 2.17. An officer oversees the internment of Italian Americans during World War II. Photographer unknown. FIGURE 2.18. Italian-American women demonstrating their patriotism during World War II. Photo by Marjory Collins (1942 or 1943). FIGURE 2.19. The largest KKK rally in Ohio’s history, at Buckeye Lake in 1923. Photographer unknown (1923).

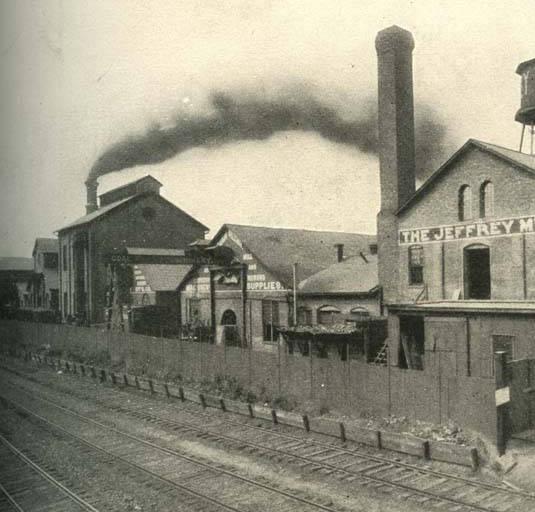

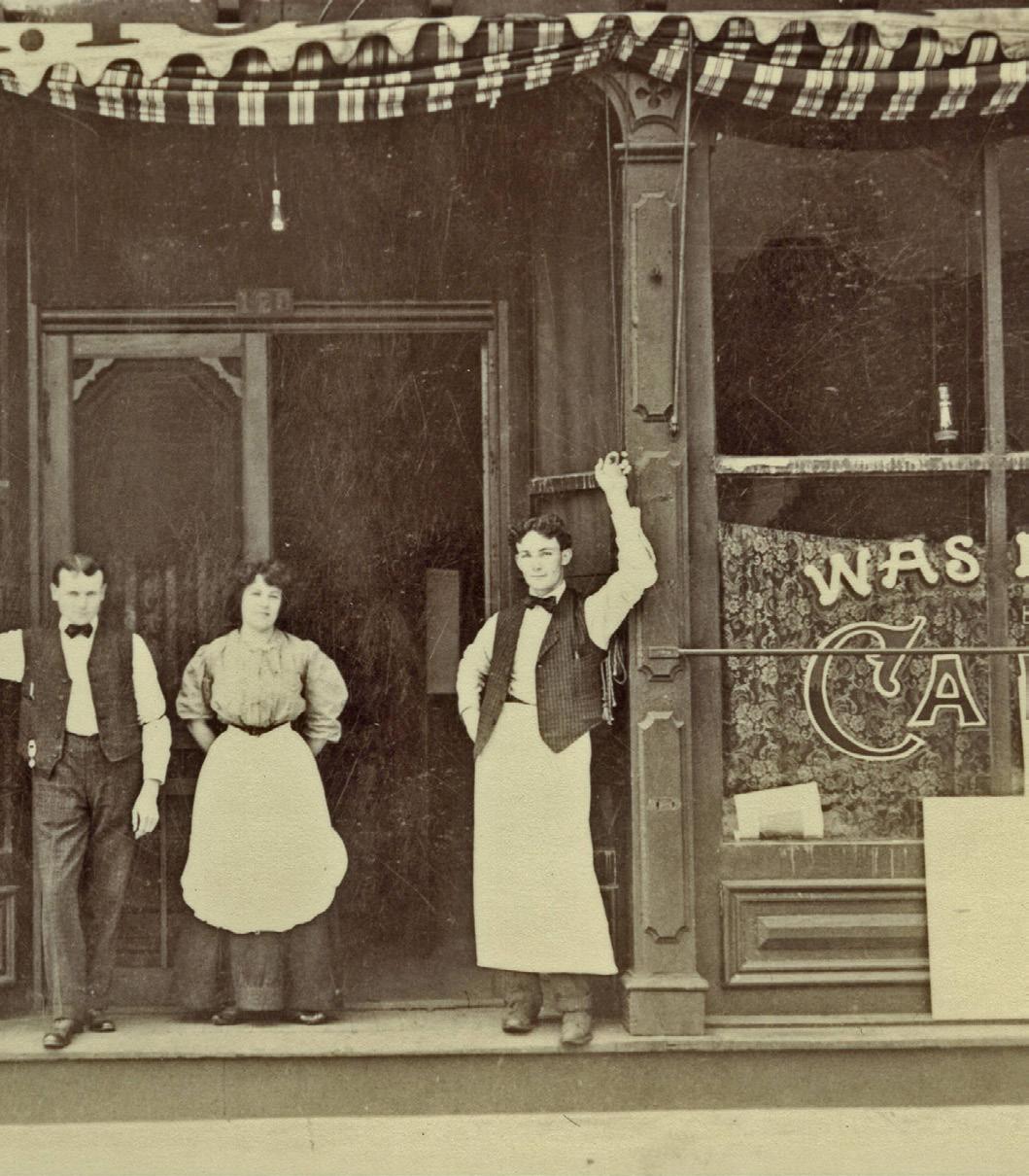

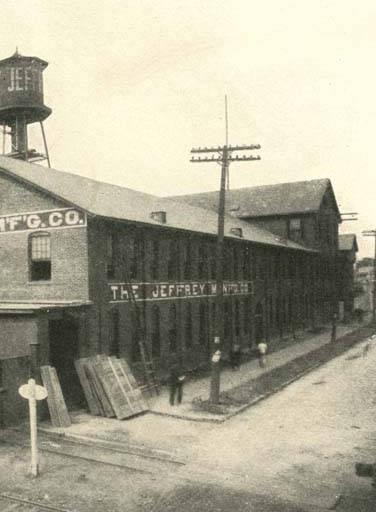

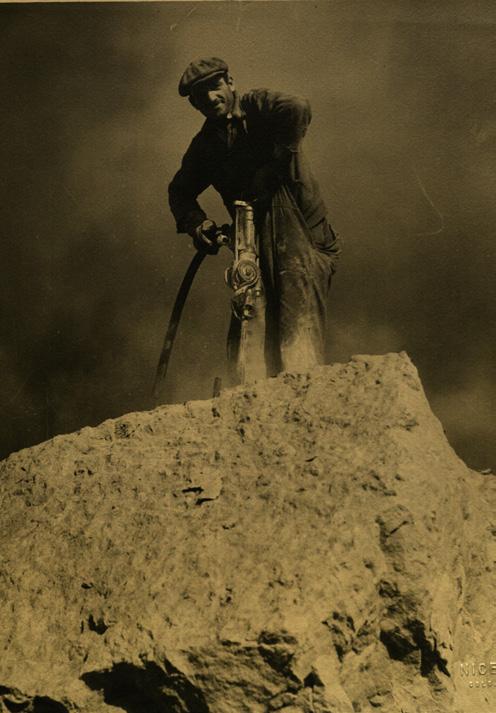

Immigrants arriving to Columbus by train at the city’s sincedemolished Union Station typically settled near the job-rich factories of neighborhoods such as Flytown, Marble Cliff, Italian Village, St. Clair Avenue, and Grandview.35,36 By the turn of the century there were approximately 11,100 Italians in Franklin County, many of whom worked physically demanding jobs at the Marble Cliff Quarry and the Columbus, Chicago, Indianapolis Central Railroad yards.37 Though Italians were known to be an insular, family-oriented group, they nevertheless created restaurants and grocery stores that enlivened their entire neighborhoods and they, like other immigrant groups, were instrumental in developing Columbus’ built environment. Structures including St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, Berry Brothers Bolt Works, and the Jeffrey Manufacturing Company office building, as well as streetcar and rail lines, were constructed using the labor and expertise of Columbus’ local ItalianAmerican community. 38,39 This did not, however, ensure their welcome. Employers refused to promote Italian-American workers to management, and other exclusionary policies were commonplace.40 For example, the boundaries of Grandview were unnaturally drawn to exclude an Italian enclave, with a fence down the middle of the block to keep Italians from crossing into the village; 41 the Grandview Pool opened in 1932 as a private club that excluded Italians and others;42 and restrictive covenants throughout Central Ohio prevented the sale of homes to Jews, Italians, and Blacks. 43 Through at least World War II, Italians who settled in the Columbus area struggled to assimilate and earn the respect of their neighbors.

Clockwise, from top left: FIGURE 2.20. The congregation at the dedication of St. John the Baptist’s Church. Photographer unknown (1898). FIGURE 2.21. The Piscitelli family in Columbus’ Short North. Photographer unknown (1930). FIGURE 2.22. An Italian immigrant at the Marble Cliff Quarries. Photographer unknown. FIGURE 2.23. The Jeffrey Manufacturing Company building. Photographer unknown (1901). FIGURE 2.24. The First and Last Chance Saloon in Flytown. Photo by Laura M. Kuhnert (1916).

Columbus continues to benefit from a strong, vibrant ItalianAmerican community that is more geographically dispersed than it once was but centers, as always, around family, social clubs, church, an annual festival, and food. Prominent names like Carfagna, Pizzutti, Recchie, Tiberi, and Penzone reflect the community’s entrepreneurial spirit and its success at overcoming the discrimination their ancestors suffered. Broadly speaking, Italian Americans in Columbus today have assimilated and, upon benefiting from various post-War World II financial programs, achieved social and economic success. Their pride at these accomplishments, however, can be tinged with sadness for all their community had to sacrifice to succeed in this place.

“[Assimilation] is a process that spans generations and involves a fair share of ambivalence. The loss of traditions and a psychic sense of displacement mix with the benefits of becoming a middle-class American. There are always two sides to every bargain.”44

—Vincent J. Cannato, historian and author of American Passage: The History of Ellis Island

FIGURE 2.25. The San Giovanni Dancers, who perform at the Columbus Italian Festival. Photographer unknown (2019).

Though Ohio is well known for its role in the Underground Railroad, the state also has a legacy of discrimination against its Black residents that dates to its very founding. Through Black Laws, housing discrimination, “blight” removal, and school segregation, the Black peoples who made Columbus their home have faced extraordinary odds and continue to suffer the devastating effects of these racist policies today.

Among the first laws passed by the new Ohio Legislature was “An Act to Regulate Black and Mulatto Persons” in 1804 — an explicit attempt to discourage free Black people and people of mixed races from moving to the state. The law and its 1807 amendment, which touched almost all aspects of daily life, made living as a Black person in Ohio restrictive, costly, and dangerous. Black men were no longer allowed to vote, serve in militias, or hold office. Black residents had to register with the county clerk and pay a fee to obtain a court order attesting to their freedom, which they had to carry with them at all times. White people were incentivized to turn over unregistered Blacks to local authorities, and Whites who employed unregistered Blacks faced steep fines if discovered. Black children were not permitted to attend taxpayer-funded schools. Blacks were made to find two White landowners within 20 days of their arrival to put up a $500 “good behavior” bond for them, payable to local authorities if they got into legal trouble. And Black people could not testify against White people in court, meaning that even the murder of a Black person by a White person would not be prosecuted. The laws did not have their intended effect, as Black people continued moving to Ohio from southern states, but they did make life very difficult for those who chose to make it their home. The Black Laws, as they came to be known, were partially repealed in 1849, but even thereafter Black people in Ohio were prohibited from serving as jurors, joining the militia, and voting.

"I thought upon coming to a free state like Ohio, that I would find every door thrown open to receive me, but from the treatment I received by the people generally, I found it little better than in Virginia… I found every door closed against the colored man in a free state, excepting the jails and penitentiaries.”45

— John Malvin, free Black carpenter who moved to Ohio from Virginia in 1827

The Fugitive Slave Acts enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1793 and 1850 permitted local governments to return escaped slaves to their owners and impose penalties on anyone who had aided their flight — even in free states like Ohio. It was therefore risky for slaves to traverse Ohio on their way to freedom in Canada, and risky for free Blacks and White abolitionists to help them. Nevertheless, a vast, secret network known as the Underground Railroad developed throughout the state, with “stations” at residents’ homes and barns in which escaped slaves could hide until it was safe to move on.46 In Columbus, more than 20 such stations have been identified.47

FIGURE 2.26. The Pauline Home, a station on the Underground Railroad. Columbus, Ohio. Photographer unknown. FIGURE 2.27. The Henry M. Neil House, a reputed station on the Underground Railroad. Photographer unknown (1889).

Throughout Columbus’ history, Black people were widely employed within the city’s thriving economy — but rarely were they welcomed as neighbors.

Beginning in the 1920s, backlash against the influx of southern Blacks and immigrants who moved to Columbus from 1900–1920 manifested in racially restrictive covenants that prevented people of color from residing in White neighborhoods. Property deeds on homes for sale during this time often added clauses that prohibited its sale to specific racial or ethnic groups. By the 1940s, two-thirds of all subdivisions platted in Central Ohio had restrictive covenants placed on them. 48

“That until the 1st day of January, A.D. 1999, said premises or any part thereof, shall not be sold, leased, mortgaged, pledged, given or otherwise disposed of to, or owned, used or occupied by any person or organization of persons in whole or in part of the Negro race or blood, and this restriction shall be a condition and covenant running with the land for the benefit of any present or subsequent owner of other premises shown on said plat; provided that nothing herein shall prohibit a person, while occupying said premises in compliance with this restriction, from employing as a servant a person not of the white race.”49

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) that enforcing such covenants would violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.50 This ruling did not put an end to the practice altogether — it would not actually become illegal in Ohio until the Ohio Fair Housing Act of 1965 prohibited discrimination in housing based on race, color, sex, national origin, ancestry, religion, disability, military status, and familial status. 51 Federal fair housing legislation would follow three years later,52 but even then, people have found legal means to maintain the Whiteness of their communities.53

During the Great Depression in 1933, U.S. Congress created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to prevent mortgage foreclosures by refinancing the 20–25% they estimated to be in default. 54 After distributing most of the $1+ million in loan funding it had available, HOLC created Residential Security Maps that divided cities into “Best,” “Still Desirable," “Declining,” and “Hazardous” zones to assess the levels of risk associated with having made loans within them. 55 Contrary to popular belief, these maps were not used to dictate who should or should not receive HOLC loans; approximately 24,000 Black families had already benefited from the program by the time the maps were developed. HOLC was, however, indirectly involved in enforcing segregationist housing policies at the federal level, in ways that are still being researched today.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), established in 1934, used maps similar to the HOLC maps for more explicitly racist ends in its administration of federal housing loans.56 The FHA insured lenders against losses on the mortgages they originated, allowing them to expand the number of loans they could make.57 But while the agency subsidized the construction of entire subdivisions for White families, it refused to insure mortgages in and near Black neighborhoods, claiming that doing so would threaten White property values and its investment in them.58 The FHA’s Underwriting Manual from 1936 explicitly demanded race-conscious evaluations:

“The Valuator should investigate areas surrounding the location to determine whether or not incompatible racial and social groups are present, to the end that an intelligent prediction may be made regarding the possibility or probability of the location being invaded by such groups. If a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes ”59

Of the $120 billion in FHA-backed mortgages financed from 1934 to 1962, less than 2% benefited people of color.60

Following World War II, the U.S. government passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, more commonly known as the G.I. Bill, to support the country’s returning veterans through access to higher education subsidies and low interest home loans. The bill is widely credited with an unprecedented expansion of America’s middle class — but also with an extreme widening of the country’s racial gap. Though it was race-neutral in design, in practice Black veterans found it difficult or impossible to access their benefits; fewer than 1% of the almost 4 million VA-guaranteed home loans from 1944–1955 went to Black vets and their families.61 Meanwhile, the post-war period proved more beneficial to the immigrant populations who could “pass” as White. The rapid pace of suburban expansion at the time allowed White ethnic populations access to capital that had previously been denied them.62

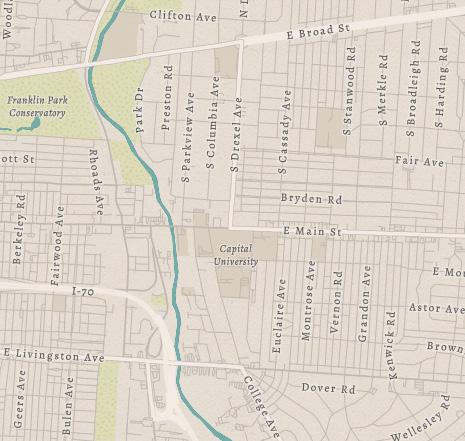

As suburbs, and the “American Dream” itself, became more firmly associated with Whiteness, Blacks were left to fend for themselves in pockets of urban land largely devoid of investment. But from 1949–1974, a series of policies known as the federal urban renewal program led to the destruction of thousands of structures within these Black enclaves to clear space for highways. In some places, entire Black neighborhoods were eliminated, destroying Black wealth, sequestering Black neighbors from one another, and preventing access to opportunity. 63,64

“Not only did you put a freeway through minority areas, but then you walled it off and made one way in and one way out. Once you did that, you cut the economic carotid artery of that neighborhood, and it began to die.”65

— Buzz Thomas, former Columbus East Side resident

FIGURE 2.28. The buildings in red were demolished when I-70 and Alum Creek Drive were built through the neighborhood beginning in 1961. Harvey Miller, ArcGIS map (2023).

Researchers at The Ohio State University’s Center for Urban and Regional Analysis developed the Ghost Neighborhoods of Columbus project to visualize neighborhoods lost to highway construction. In total, they found 380 buildings were demolished in this area, including 286 dwellings, 86 garages, 5 apartments, and 3 stores.66

“Although the highway divides us, our memories are never lost” 67

Hanford is a village founded directly east of Columbus in 1909 that became a largely Black community as southern Blacks moved to Columbus during the Great Migration. In 1946, the Federal Housing Administration financed 146 Cape Cod homes for Black veterans in a new subdivision there called the Hanford Village George Washington Carver Addition — one of the only in the country to offer an all-Black housing program through the G.I. Bill.68 Many of its residents were Tuskegee Airmen, who were the first Black fighter pilots and support crews in the U.S. Army Air Forces and had the lowest loss records of all escort fighter groups in World War II.69 The village was annexed by Columbus in 1955 and, shortly thereafter, targeted as one of the city’s near-east, predominantly Black neighborhoods to be divided by I-70 (as opposed to nearby Bexley, a wealthier community).70 A number of veterans’ homes — which were less than 20 years old at the time — were ruled “blighted” and destroyed. The neighborhood remains to this day, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014, but has never been the same since the highway came.71

Clockwise, from top left: FIGURE 2.29. The Hanford Village historical marker. Columbus, Ohio. Photo by Rev. Ronald Irick (2016). FIGURE 2.30. A map showing the path of I-70, which was drawn to avoid the wealthy Bexley neighborhood and instead pass through Hanford Village. Designing Local (2025). FIGURE 2.31. Maj James A. Ellison reviews the first class of Tuskegee Airmen. United States Air Force, Tuskegee, Alabama (1941).

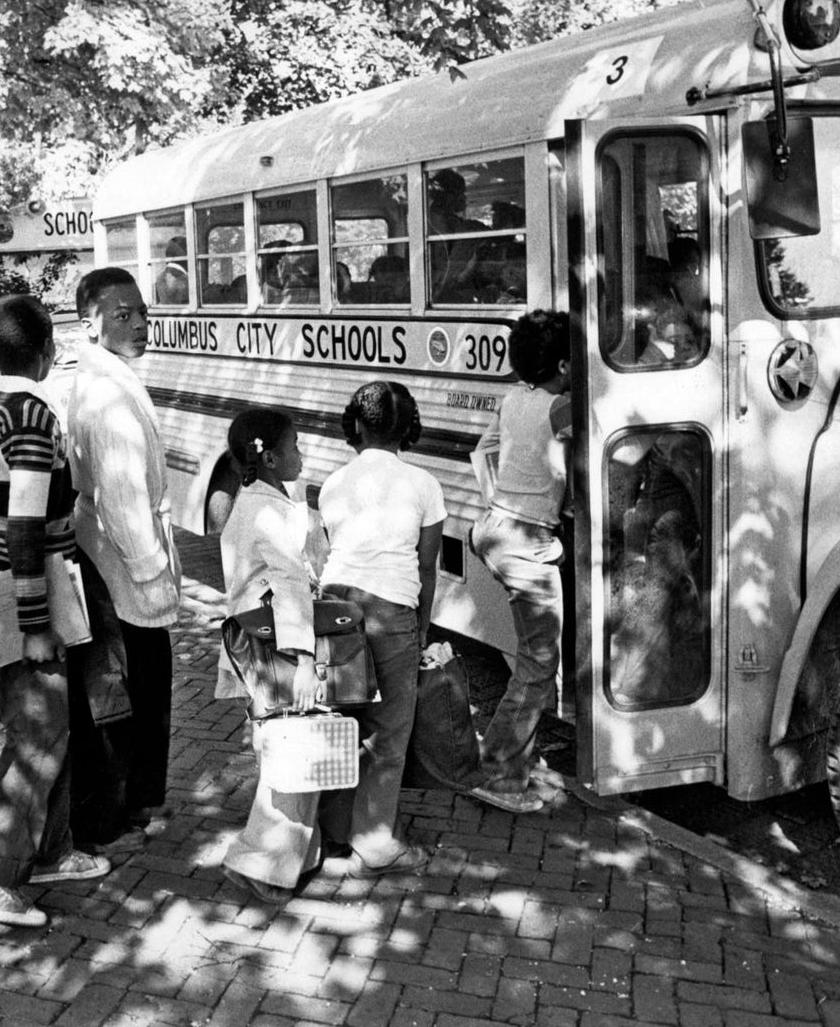

In 1977, 23 years after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case that ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, a class action suit brought by Columbus City Schools students (Penick v. Columbus Board of Education) charged that the Columbus Board of Education was intentionally perpetuating racial segregation within the district, for example by allowing White students to bypass their neighborhood schools in favor of further schools with a lower percentage of minority students. The court ruled in the plaintiff’s favor, forcing the district to provide a systemwide desegregation plan.

Their plan — to bus White students to schools in Black neighborhoods and Black students to schools in White neighborhoods — was peacefully initiated with the support of thousands of community volunteers on September 6, 1979. Approximately 45% of the district’s students were bused, but many families chose to relocate to the suburbs rather than participate in desegregation. When the court ruled in 1977, there were 95,000 students enrolled in the district; by 1985, there were just 67,000. Columbus, one of the first cities in the United States to desegregate, ended its busing program in 1996.72

As of October 2025, the district enrolled just 46,367 students — of whom 82% were non-White. 73

FIGURE 2.32. Columbus City Schools students boarding buses after a federal judge ordered the district to desegregate. Columbus, Ohio. Photographer unknown (1977).

“What we see is a trajectory, then, that these redlined neighborhoods are really devastated in terms of their housing market, in terms of their physical condition — and, in fact, longitudinally now we’ve done studies where we’ve seen a whole host of environmental and social costs of this history of redlining.”74

— Jason Reese, Vice Provost for Urban Research and Community Engagement and Associate Professor at The Ohio State University

The legacy of discriminatory housing policies and other racist policies and attitudes is still being lived in Franklin County, which is in the bottom quartile of all U.S. counties in terms of disparities between White and Black residents. Indeed, according to a study by McKinsey & Company, it would take Black Columbus-area residents more than 700 years to close the city’s prosperity gap, given current rates of progress (as compared with a 300-year average for Black Americans nationwide). 75 One factor continues to be housing. The National Community Reinvestment Coalition published a study of HOLC’s redlined neighborhoods in 2018 and found that, for the most part, segregation and economic inequality characterize those communities to this day.76 In Columbus, 82% of “Hazardous” neighborhoods remain low-to-moderate income, and 89% of the city’s “Best” neighborhoods are middle-to-upper income — and 91% white.77 According to a recent real estate report, homeowners in previously redlined neighborhoods gained 52% less — or approximately $212,000 less — in personal wealth from property value increases than those in greenlined neighborhoods. 78 In Franklin County, Black families today are 32% less likely to own a home than Whites,79 and they fare worse on 24 additional indicators of prosperity.80

FIGURE 2.33. Black Columbus residents enjoyed hanging out in Franklin Park during the late 1960s and 1970s. Columbus, Ohio. Photo by Steve Harrison.

Those most impacted by the Christopher Columbus statue conversation — the city’s Indigenous, Black, and Italian-American community members — have experienced radically divergent trajectories during their time on this land now called Columbus, Ohio. While Italian Americans have largely assimilated and attained economic, cultural, and political success, the Indigenous community has struggled with the pain of erasure and Black people have struggled to overcome centuries of discriminatory policies. The stark differences in their lived experiences is one reason for their differing views of the Christopher Columbus statue and why the conversation about it is so emotionally charged.

Christopher Columbus’ legacy is a complicated mix of greatness and discovery, exploitation and incompetence, made more difficult to untangle by conflicting accounts of his time in the Caribbean. This section excerpts and adapts text from the Reimagining Columbus team’s “Beyond Discovery” white paper to highlight key aspects of what is known about Columbus’ four voyages to the Americas.

Like many boys from working class families in the 15th century citystate of Genoa, Cristoforo Colombo — Christopher Columbus — was destined for the sea. Born in 1451 and educated in a grammar school through early childhood, Columbus joined a ship as a merchant’s apprentice during his adolescence before becoming a sailor aboard Genoese ships in the Mediterranean. He moved to Lisbon upon being shipwrecked in Portugal at age 25, where he remained for the next 10 years. As Lisbon was the epicenter of Atlantic exploration at the time, Columbus had access to the most current maps and centuries of scholarship about cosmography and geography, which he used to calculate that the earth must be no more than 18,000 miles in circumference (it is actually 24,830). He also became absorbed in Marco Polo’s account of East Asia and its riches, and sought to chart a short western sea route to China and its vast trading opportunities. He proposed an exploratory voyage to Portugal’s King João II in the early 1480s who rejected it, in part, because Columbus wanted to keep so much of the voyage’s profits. By the time Columbus arrived in Spain in 1485, his proposal had likewise been rejected by Spain, England, and France.

Only when Granada fell in 1492 did the Spanish Crown consider funding Columbus’ venture. At that point, it was a low-risk opportunity for Spain’s King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I in their quest to overtake Portugal as a state power. In Capitulations of Santa Fe , his contract with the Crown, Columbus was granted the title of governor over any lands that he might find, but he was also made an official representative of the Catholic monarchs, meaning that any land he and his family governed would remain under the Spanish Crown. Capitulations’ terms indicated that the voyage’s goal was to establish Crown-controlled trading posts in east Asia more easily reachable by sea than land, which Columbus and his family would administer and control.

The monarchs named Columbus, “now and henceforth, the Admiral in all islands and mainlands that shall be discovered by his effort and diligence in the said Ocean Seas, for the duration of his life, and after his death, his heirs and successors in perpetuity, with all rights and privileges belonging to that office.”81

In the summer of 1492, Columbus assembled ships, a crew, funds, and supplies in the port of Palos, Spain, which helped fund the voyage by providing the caravels Niña and Pinta ; Columbus chartered the Santa María with financial support of merchants from Genoa and Florence. For the most part, local men made up the 85-person crew. They launched from Palos on August 3 and reached the Canary Islands on September 9, from which they charted a southwesterly course. The favorable winds at that latitude helped propel this and subsequent voyages across the Atlantic to the islands of the Caribbean. But on October 10, one month into their sea journey with no land in sight, Columbus recorded in his log, “Here the men could bear no more; they complained of the length of the voyage.” He had intentionally misled the crew about how far they had traveled, under-reporting how many leagues they made each day to hide his miscalculation of the journey’s length. As the crew was contemplating mutiny, however, land was sighted. Columbus and members of his crew disembarked on the Taíno island of Guanahaní on October 12.82

The Taíno people who had populated Guanahaní for hundreds of years by the time of Columbus’ arrival had developed a complex, sophisticated society featuring kings or chieftains called caciques; large towns and ceremonial plazas; sophisticated artwork, religion, and cosmology; and large sea-faring canoes. 83 Columbus described his crew’s first encounter with the Taíno people as peaceful — though his own diaries and letters are the only sources available, and perhaps unreliable. In any case, after Columbus declared possession of the island for the Spanish Crown, he bartered with the islanders and noted both their gentleness and the decided advantage he had in the exchange, given their differing sense of the value of goods. Columbus and his crew then left Guanahaní and sailed a course through the Bahamas, forcing Taíno people to work as guides and interpreters.84 Columbus was convinced the Taíno saw him and his crew as deities, writing confidently in his log about their beliefs despite his ignorance of their language and customs. He believed they had no religion and would readily convert to Christianity.85

When the fleet reached Cuba, Columbus thought they had found the Asian mainland. He sent the Arabic and Chaldean interpreter he had brought to communicate with the Mongol Empire’s Grand Khan along with an envoy to seek his court.86 They did not find it, of course, but they noticed people wearing gold ornaments, fueling Columbus’ drive to find sources of gold on the islands. The fleet continued to the island that is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic — which he named La Española, or Hispaniola in English.87 On December 25, the Santa María shipwrecked on a reef off of La Española. The Taíno cacique Guacanagarí and his people helped Columbus’ crew salvage the ship’s cargo, and Columbus decided to build his first fort at that location out of the ship’s timbers. He named the fort La Navidad (i.e., Christmas) after the day of the shipwreck, which he interpreted as divine providence — a sign from God that the first European settlement in the Americas should be built there: “In truth it was no disaster, but rather great good fortune, for it is certain that had I not run aground there, I should have kept out to sea without anchoring at that place.”88 Columbus left 39 men at the fort with instructions to trade with Taíno people for gold, and was confident in the outpost’s success, writing:

“I have established warm friendship with the king of that land, so much so, indeed, that he was proud to call me and treat me as a brother. But even should he change his attitude and attack the men of La Navidad, he and his people know nothing about arms and go naked, as I have already said; they are the most timorous people in the world. In fact, the men that I have left there would be enough to destroy the whole land, and the island holds no dangers for them so long as they maintain discipline.” 89

Columbus charted a northerly return course to Europe with the Niña and the Pinta . He brought ten Taíno people with him on the journey back to Europe (only two of whom survived to return to the island the following year). While sailing back to Europe, Columbus wrote an account of his voyage now called “Columbus’s Letter on His First Voyage,” which sought to demonstrate how valuable this and future journeys could be to the Spanish Crown. In it, he described islands with abundant resources and friendly people — and maintained, as he would for the rest of his life, that he had reached Asia. When he arrived home, the Spanish monarchs published Columbus’ account of his voyage in Castilian and Latin to establish their claim to the lands Columbus visited.

King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I soon gave orders to begin preparations for another, larger voyage, with the intent of establishing a frontier trading settlement at La Navidad. They provided a fleet of 17 ships that approximately 1,200–1,300 colonists enlisted to man, inspired by Columbus’ account suggesting the possibility of wealth and social advancement in the Americas. The fleet carried provisions, tools, seeds, and farm animals in the hopes of successfully transplanting familiar aspects of European life in the Americas, as well as goods intended for trade with the Taíno that would deepen relations in support of international trade and their conversion to Christianity.90

The second voyage left Cádiz on September 25, 1493 and reached the Lesser Antilles, the island chain to the southeast of La Española, on November 3. Columbus reached La Navidad on La Española on November 27 to find the fort completely destroyed, the colonists dead. 91 Rather than resettle at La Navidad, Columbus chose to continue sailing to find a suitable location for the next settlement. His crew left the ruins of La Navidad on December 7, but due to unfavorable winds it took them 25 days to travel just 100 miles eastward. When they finally spotted a hospitable bay on the northern coast of the present-day Dominican Republic, Columbus decided it was time to end their search. They named their new settlement La Isabella after their monarch, and by several accounts the location they chose seemed promising. Chroniclers described its large river, green and fertile river banks, abundant fish, and stone quarries.

The problems that would plague La Isabella for its entire existence, however, began almost as soon as the ships landed. Food that had been brought on the voyage was largely spoiled, and within a few days of their arrival most of the men fell sick; several died. Historians suggest that parasites new to the colonists may have caused widespread dysentery and gastrointestinal ailments, and that both the colonists and Taíno may have contracted influenza from the pigs and horses brought on the ships. Despite the Europeans’ poor health, Columbus insisted that they immediately start constructing the settlement. Colonist Bartolomé De las Casas wrote, “everyone had to pitch in, hidalgos [low-level noblemen] and courtiers alike, all of them miserable and hungry, people for whom having to work with their hands was equivalent to death, especially on an empty stomach.” Columbus also commandeered the hidalgos ’ horses for agriculture and construction, about which they were outraged.

The first open rebellion among the colonists against Columbus took place in February 1494. Columbus jailed the ringleader and hanged several colonists, which further enraged the hidalgos , and fueled his later discredit in Spain. By March, the first rebellion had been squashed and the colonists’ health had begun to improve. Columbus then organized an expedition of 500 men and several Taíno guides into the region of La Española they called the Cibao to establish forts and search for gold. After a 100-mile march, the group stopped to build Santo Tomás, a small fort at a bend in the Jánico River. They did not find gold there, other than what they traded with the Taíno, so Columbus left around 50 men at the fort to maintain their presence in the region and returned with the rest to La Isabella.

They arrived at La Isabella on March 29 to find that illness had struck again, killing many settlers, and that a fire had destroyed two-thirds of the settlement. Columbus determined that they must build mills to grind the wheat they brought from Spain since other provisions were running low, but he had to use threats and punishments to force the sick colonists to work. Additionally, just a few days after returning from the expedition, Columbus received word from Santo Tomás that the Taíno were fleeing the nearby villages and that the cacique Caonabó was preparing to attack.92 Columbus decided to make a show of force by sending almost 500 men to the fort and ordering the fort’s commander to march 350 of them through the heavily populated Vega Real, Cibao’s central plain. There, violent confrontations between the Europeans and the Taíno escalated.

Although the conditions in La Isabella and the Vega Real were far from stable, Columbus decided the time had come to continue exploring the region by sea, in hopes of finding the Asian mainland. On April 25, Columbus departed from La Isabella to explore Cuba, believing that it might have gold and that it could be Asia, despite what he had been told by the Taíno and his own explorations of the island during his first visit. Columbus’ health deteriorated as he navigated among the many islands along Cuba’s coast — the food on board was poor, he barely slept, and despite constant efforts his ships frequently ran aground in the shallow waters.

After a Taíno man who had been seized during the voyage finally convinced Columbus that Cuba was, in fact, an island, he decided to turn back toward La Española on June 13. Travel was difficult as they continued eastward. They encountered bad weather, their rations were reduced to “a pound of rotten biscuit and a pint of wine,” according to Colón, and Columbus’ ship was taking on more water than they could pump out.

In Cabo de la Cruz, a cape named by Columbus, the crew were saved by the Taíno, who gave them cassava bread, fish, and fruit to eat. Not finding any favorable winds to return to La Española, Columbus decided to return to Jamaica, where they were again saved from starvation by the Taíno. Colón wrote that Columbus wanted to stay in Jamaica, but with their food shortage and deteriorating ship, he decided instead to wait for more favorable weather and continue on to La Española.

When the weather improved, the three ships headed eastward. They lost sight of Jamaica on August 19 and reached La Española a few days later. Colón described the state of relations between the settlers and the Taíno when Columbus returned from Cuba and Jamaica:

“He found the Island in a bad state: the Christians were committing innumerable outrages for which they were mortally hated by the Indians, and the Indians were refusing to return to obedience. All the caciques and kings had agreed not to resume obedience, and this agreement had not been difficult to obtain.” 93

Columbus remained bedridden until January of 1495. A relief fleet arrived at La Isabella that winter with food, wine, medicine, cloth, livestock, and hardware, though far less than Columbus had requested — possibly in response to reports of the settlement’s mismanagement and depleted population.

Columbus decided to build more fortifications along the route to the Cibao to help control the region: the Magdalena fortress on the Yaque River in the province of the cacique Guatiguará, and the fortress of Concepción on the Rio Verde, near the capital of the cacique Guarionex. Guatiguará was quick to attack the fort in his province. 94 Columbus escalated the conflict when he decided to create a show of force against the rebelling Taíno. He launched an expedition against Guatiguará, and while his men were unable to capture him, they seized 1,600 Taíno and marched them to La Isabella — an act that initiated the European enslavement of Indigenous Caribbean people. 95

Some 550 men and women were trafficked back to Spain, while others remained indentured at La Isabella; the 400 or so who remained were set free and fled to remote areas of the island. More than a third of the 550 Taíno people taken to Spain died before the ship landed. 101

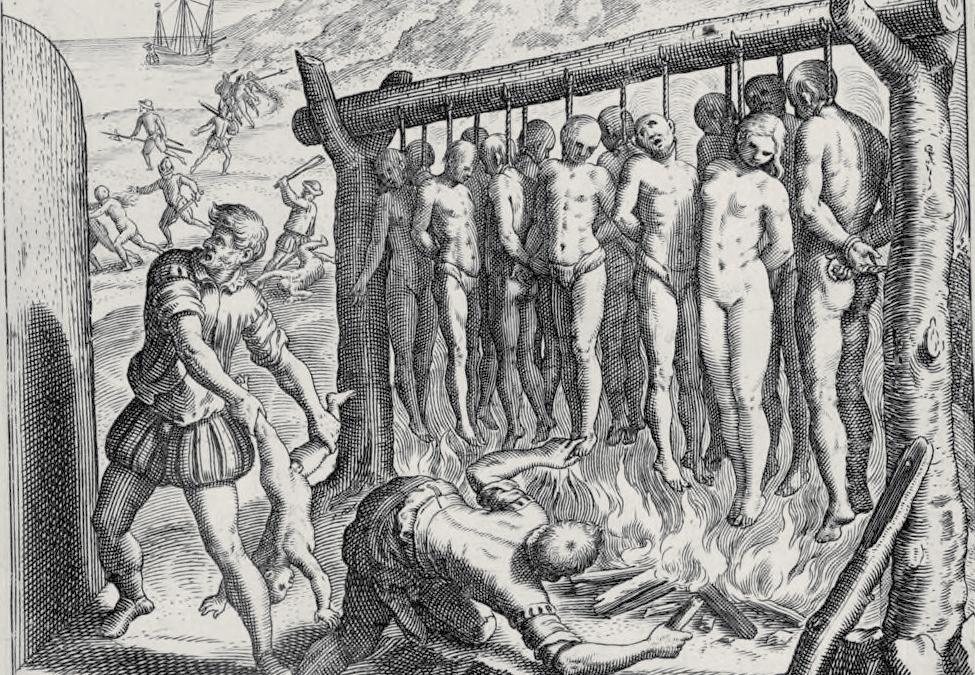

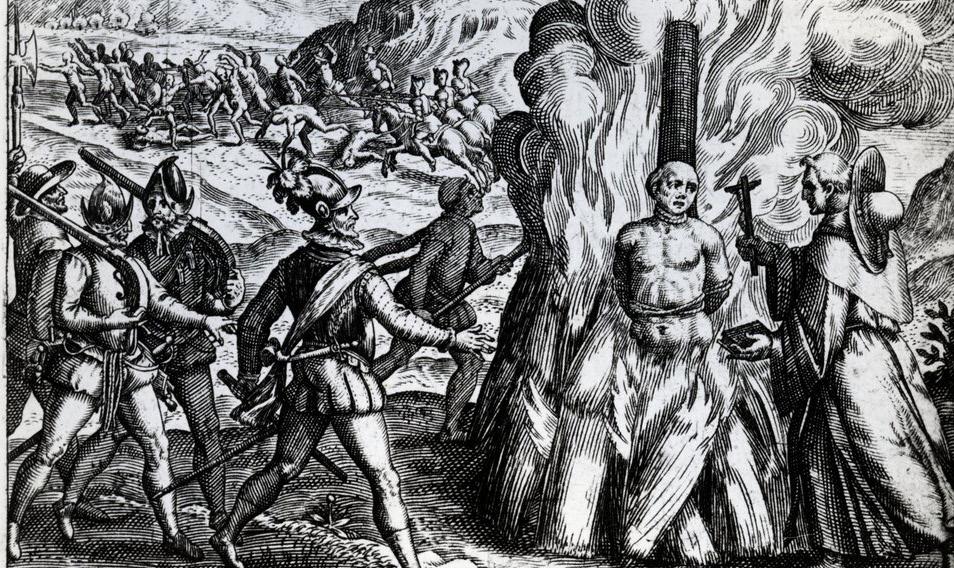

Theodor de Bry was a 16th century engraver who introduced Europeans to the Americas through his Grand Voyages, an encyclopedic 14-volume series of images depicting scenes of everyday life, bizarre customs, and colonialist violence in the New World. He also illustrated A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1542) by Spanish friar Bartolomé de las Casas, which detailed the atrocities de las Casas saw conquistadors inflict upon Indigenous peoples in Hispaniola and elsewhere.96 The artist never stepped foot in the New World himself, but rather took inspiration from the accounts of colonizers and missionaries who had; he was known to have taken liberties with his subjects in order to increase book sales.97 While his engravings cannot therefore be considered historically accurate, they do seem to contain kernels of truth.98

Above: FIGURE 3.1. Theodor de Bry. Self Portrait, engraving (1597). Top right: FIGURE 3.2. Theodor de Bry. Conquistadors attacking a village of Indians. Scene of hangings and stake. Engraving (1598). Bottom right: FIGURE 3.3. Theodor de Bry. The Burning of the Cacique, engraving (1598).

“They erected certain Gibbets, large, but low made, so that their feet almost reached the ground, every one of which was so ordered as to bear Thirteen Persons in Honour and Reverence (as they said blasphemously) of our Redeemer and his Twelve Apostles, under which they made a Fire to burn them to Ashes whilst hanging on them.” 99

— Bartolomé de las Casas

“When tied to the stake, the [Taíno] cacique Hatuey was told by a Franciscan friar who was present… something about the God of the Christians and of the articles of Faith. And he was told what he could do in the brief time that remained to him, in order to be saved and go to heaven. The cacique, who had never heard any of this before and was told he would go to Inferno where, if he did not adopt the Christian faith, he would suffer eternal torment, asked the Franciscan friar if Christians all went to heaven. When told that they did he said he would prefer to go to hell.” 100

—Bartolomé de las Casas

In late February on La Española, the cacique Caonabó and his army marched against the fortresses of Magdalena and Santo Tomás, which they held under siege for a month. Shortly after Caonabó’s retreat, he was captured and taken to La Isabella, then to Spain for trial. The other caciques of the island allegedly planned an insurrection in the Vega Real to march on La Isabella in retaliation, but Columbus organized a preemptive strike against them. The Taíno alliance was severely weakened by losing the battle, and Columbus took the opportunity to impose a forced tribute system on them to benefit the colonists. Colón celebrated that “the Christians’ fortunes became extremely prosperous,” and said that “Hispaniola was reduced to such peace and obedience that all promised to pay tribute to the Catholic sovereigns every three months.”102 The tribute system was enforced by Columbus and his brothers as they made expeditions throughout the island.

The years 1495–1496 were further devastating for the Taínos of La Española. Diseases brought by the Europeans continued to kill them, and the labor required to maintain the tribute system decreased their own subsistence food production (which was also being cut into by the colonists). In addition, the accounts of Las Casas and Peter Martyr D’Anghiera suggest that Taínos exercised an organized resistance to the colonists’ theft by burning their fields and destroying crops, rather than giving them to the Spanish.

In October of 1495, a fleet of four ships from Spain arrived, led by Juan De Aguado. The ships carried supplies and reinforcements, along with instructions from the Spanish Crown to investigate the administration of the colony in response to reports from its former leaders. The monarchs had also sent a master miner and several assistants to focus on finding profitable sources of gold. Aguado found many extremely dissatisfied, sick, and disabled colonists at La Isabella, and collected their stories for the monarchs. Columbus decided he must return to Spain to plead his own case to the Crown, but all voyages out of La Española were delayed when hurricanes destroyed Aguado’s fleet (Columbus’ own anchored fleet had been destroyed by a hurricane in June 1495). While the fleets were repaired and rebuilt, Columbus sent Bartolomé, soldiers, and the miners to explore the southern part of the island around Río Haína, which was thought to contain gold mines. The region did prove more productive for mining, and was named San Cristóbal. Columbus was able to take news of the gold mines back to Spain, and his last orders for Bartolomé before departing in March of 1496 were to build and fortify a settlement in the region, which would become the city of Santo Domingo.103

When Columbus arrived in Spain, he received a lukewarm welcome — news of the disastrous settlement on La Española was circulating in the court, and the monarchs were occupied with their war with France for control of the southern Italian Peninsula. In the summer of 1496, the monarchs sent a fleet to La Española with supplies and royal orders to abandon La Isabella and establish a new settlement in Santo Domingo. They further gave instructions to enslave the Taíno caciques and any of their subjects who had used armed resistance against the Europeans. When those ships returned to Spain on September 29, 1496, they carried 300 Taíno prisoners. Many died during the journey, and others died soon after arriving in Spain.

It took a full year for the crown to give orders for a third voyage led by Columbus. King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I authorized only 330 colonists, but this time it was more difficult to recruit a crew and they resorted to commuting prisoners’ sentences to persuade them to make the journey. They also sent six women artisans, more soldiers and priests, and a group of government officials, in an attempt to establish a sense of order on La Española on behalf of the Crown. All of these new colonists would be salaried by the monarchy, and Columbus was permitted to grant land to the settlers so that they would establish households, work, and live on the land.104

The third voyage left Spain on May 30, 1498, more than two years after Columbus last left La Española. Three of the ships headed straight for La Española with the colonists and provisions, while Columbus led the other three on a southwesterly course to try to find the “mainland” he so doggedly sought. On July 31, his fleet sighted land — an island off the coast of South America that Columbus named Trinidad (as it is still called today). They explored the island and the coast of what is today Venezuela on the South American continent, and according to various accounts, traded peacefully with the people they met. He had finally reached the mainland — not of Asia, but of South America.105

On August 15, Columbus left his exploration of the South American continent and sailed back to La Española. In the almost two and a half years since he had been there, the tribute system he imposed upon the Taíno had had a disastrous effect on the population.

Colonists continued to die of disease and starvation, and Francisco Roldán, who Columbus had appointed as the mayor of La Isabella on his departure, organized a rebellion against Bartolomé and Diego Colón in May of 1497. Roldán and the allied colonists rejected the deplorable conditions of life in La Isabella, and instead formed a new polity in the province of Xaraguá. The livelihoods they established there looked very different from those attempted in La Isabella, which unsuccessfully replicated European lifeways. These colonists lived among Taíno communities and forged exploitative alliances with them, including taking Taíno wives and creating mestizo families. They survived by learning Indigenous ways of life, while ultimately maintaining their social power over the Taíno.

When Columbus arrived at Santo Domingo, he found his authority seriously threatened by Roldán and his followers. In an attempt to keep the power given to him by the Crown, Columbus granted the rebels amnesty and gave them repartimientos — land, and the right to exploit the Taíno as vassals — at Roldán’s insistence. This was not according to the Crown’s plan. In the European feudal system, vassals lived as tenants on land owned by lords, and received access to land and protection in exchange for their service, labor, loyalty, taxes, or other forms of tribute. This concession to Roldán effectively began the Spanish-American institution of the encomienda, in which European colonists were granted the right to demand labor tribute from Indigenous people in exchange for presumed instruction in Christianity.

Seeing these rights granted to Roldán and his followers, the other colonists also demanded Taíno labor tributes, which Columbus granted to prevent more revolts.

In October of 1498, five ships returned to Spain carrying 300 returning settlers and 500 of their enslaved Taíno vassals. Queen Isabella I was reportedly outraged at their arrival, demanding, “What right does my Admiral have to give away my Vassals to anyone?” Hearing additional complaints about Columbus from the colonists, the monarchs sought to end his governance. In the summer of 1499, they sent Francisco de Bobadilla to Santo Domingo to take control of La Española. When his ships arrived in August, Columbus and his brother Bartolomé were attempting to put down rebellions elsewhere.

As Bobadilla sailed into the Ozama River, he saw gallows on both banks from which hung two Spanish rebels. He stormed the fortress at Santo Domingo, which was being defended by Diego Colón and a mob of angry colonists. When Columbus and Bartolomé returned to Santo Domingo, all three brothers were arrested, and in October 1500 they were sent back to Spain in shackles, with their financial rights and privileges stripped.106

On the journey back to Spain, Columbus composed a letter to Juana De la Torre, the mistress of prince Juan of Spain’s household. In it, he described how he had been wronged and how the rebellion on La Española was not his fault, and pleaded to be let back into the Crown’s good graces. When the letter was shown to Queen Isabella I, she called him back to court and his financial privileges were restored, but he would never again be allowed to govern in the Americas. Columbus initiated a lawsuit to have all his powers and privileges restored (and passed down to his heirs), which continued well past his death. The testimony, evidence, and records from this trial now provide a major source of information about Columbus and his voyages.107

“...from

1494 to 1508, over three million people [on Hispaniola] had perished from war, slavery, and the mines. Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it…”

108

—

Bartolomé de las Casas

In 1499, navigator Vasco da Gama achieved the feat of reaching and returning from India via a southerly route around the African continent, pushing the Portuguese closer to a reliable sea route to Asian trade networks that circumvented Muslim territories. King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I believed that continuing to explore the Americas would reveal a shorter route, so they accepted Columbus’ proposal for what would be his final voyage in 1502, as a strictly exploratory venture that would continue the search for trade routes that could compete with da Gama’s route to India. He was expressly forbidden from bringing back any enslaved people or captives. Among Columbus’ crew were his brother Bartolomé and his son Fernando. He departed with four small ships on May 9, 1502, and on June 29 he reached La Española. He had also been forbidden by the monarchs to land on the island.

The fleet sailed through storms for 88 days before they reached the coast of present-day Honduras. Columbus’ health was extremely poor, and remained so for the rest of the journey. They finally landed somewhere along what is now the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua. There, Columbus met Indigenous people who indicated that gold fields were present throughout the region. Columbus was guided to a place called Carambaru, where he observed people wearing gold discs around their necks, but they were unwilling to trade for them. Columbus’ fleet continued east along the Central American coastline in search of information about gold and goldfields.

Storms continued as Columbus’ fleet pursued the coastline eastward, and their ships became increasingly weather-beaten. They would pause to make repairs where they could, but eventually decided to turn around and travel west back along the coast to stop fighting unfavorable winds and currents. When they reached the region of Veragua on January 6, 1503, they found a river and a safe harbor where they rode out more torrential storms until February. The cacique there indicated that gold was abundant in the region and Columbus decided to build a settlement there, but between his worm-eaten ships and the threats against his crew members from the native population, he was unable to sustain life on both land and sea.

Columbus decided to return to sea in his two least-damaged ships, leaving on Easter Monday and landing among the archipelagos south of Cuba on May 13. Dangerous weather returned as they sailed along the coast of Cuba, and the two remaining ships sustained more damage. Once the weather improved they headed for Jamaica in the hopes of eventually reaching La Española, where the Crown had permitted them to stop briefly before making the return voyage to Spain. Instead, by the time they reached Jamaica at the end of June, the two ships were damaged beyond repair, and the crew was stranded on the island.

From Jamaica, Columbus wrote a letter to the monarchs on July 7, 1503, detailing his journey, extolling the riches of the Central American sites he had visited, and asking for a ship with provisions to come rescue him and his crew. He eventually entrusted the letter with Diego Mendez, a young crew member who, according to his later testimony, had established alliances with the Taíno caciques in Jamaica who had saved the stranded Europeans from starvation. Mendez secured a canoe through trade, and Columbus asked him to embark on a canoe journey from Jamaica to La Española to purchase a ship to rescue the rest of the crew, since he suspected they would not be welcome or fed by the Jamaican Taíno indefinitely.109 When Mendez arrived in Jamaica he stayed with its governor, Ovando, for several months, during which time he was conducting a brutal campaign to subjugate the remaining Taíno chiefdoms not under Spanish control. Mendez was present for Ovando’s brutal massacre of 84 cacique — who had welcomed an expedition of colonists with feasts and festivities — in which they were burned alive before colonists destroyed the rest of the village and killed its inhabitants.110

Mendez eventually made his way to Santo Domingo, where he purchased a ship and provisions to send to Jamaica to bring back Columbus and the rest of the crew. From there they returned to Santo Domingo, and then to Spain, where they arrived in November 1504. Queen Isabella I, his strongest supporter at court, died soon thereafter.

After his fourth and final voyage, Columbus’ already-poor health continued declining rapidly. He spent his last years lobbying the Crown to restore the governing and title privileges they had revoked, in order to pass them down to his heirs. With difficulty he traveled to the royal court, pleading his case with King Ferdinand II on multiple occasions. Those privileges were never regranted, and Columbus died in Valladolid on May 20, 1506. Though he was not able to pass down a title to his son, Diego inherited the wealth that Columbus had accumulated and married into the highest aristocratic lineage.111 For decades, Columbus’ kin continued to litigate against the Crown for their right to governorship in the Americas. In 1536, after years of appeals on both sides, the Crown and Columbus’ heirs submitted to arbitration. Though the title of Governor General of the Indies was not permitted to them, Columbus’ heirs received the title of Admiral of the Indies in perpetuity, lordships in Jamaica and Central America, land rights and titles on La Española, and a payment of 10,000 ducats annually.112

While Columbus the explorer has been lauded for his seamanship, bravery, and religious zeal, for the most part modern historians and contemporaneous documentarians agree that his conduct in the Caribbean was deplorable. Through their quest for personal gain and converts to Catholicism, Columbus and his crew exploited and caused the deaths of millions of Taíno peoples. This was unlikely to have been their intent. Their total disregard for Indigenous lives, however, shocked even people at the time and demands to be taken seriously today.

A Catholic Spanish explorer who never set foot on the U.S. mainland, Christopher Columbus seems an unlikely American hero. His mythos, however, has inspired thinking about the American identity, and who has a rightful claim to its promise, since its founding. This section discusses why Columbus has resonated so deeply here, and why Italian Americans have so strongly identified themselves with him.