Over the course of six books, this report fully details the activities and outcomes of the Reimagining Columbus project, through which the City of Columbus, Ohio reckoned with its relationship to the explorer Christopher Columbus.

THE SIX BOOKS IN THIS SERIES INCLUDE:

BOOK # 1

provides insights into how the City of Columbus came to display a Christopher Columbus statue on the grounds of its City Hall, why that statue was removed in 2020, and how the Reimagining Columbus project was designed to help the city determine what to do with it going forward.

BOOK # 2

describes research the project team undertook to discover the many stories that have played out among the people of Columbus, Ohio since long before it became a city, the truth of Christopher Columbus and his conduct in the New World, and how an explorer who never reached the United States became a symbol of all its promise.

BOOK # 3

outlines the community engagement methodologies employed throughout this project and chronicles the events and activities offered by the Reimagining Columbus project team, as well as findings from these conversations.

BOOK # 4

connects the project team’s research findings and community engagement results to the design principles that informed concepts for a new space in which residents might one day experience the reinstalled Christopher Columbus statue.

BOOK # 5

applies the design principles developed from research and community conversations, and best practices in placemaking, to articulate how a new statue site should look and feel, how visitors should be able to interact with it, and how it could engender profound experiences that reverberate for generations.

BOOK # 6

offers an Art Plan for City Hall Campus to guide the implementation of future public artworks there.

QR CODE

Original materials developed through this program are available at reimaginingcolumbus.com , or upon request.

Reimagining Columbus is funded by the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project, a multi-year commitment aimed at transforming the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented.

Columbus, Ohio is the most populous city in the world named for Christopher Columbus, and home to the largest statue of his likeness on the U.S. mainland. The 3.5-ton, 20-foot bronze alloy statue was created by the famed sculptor Edoardo Alfieri as a gift from the City of Genoa, Italy to Columbus in 1955. The piece was designed specifically for placement at the front steps of Columbus City Hall and intended as a steadfast symbol of Italian American pride and international cooperation — “a gesture of brotherhood of significance to the entire world.”

Yet 65 years on from its installation, the Columbus statue had come to represent something altogether different to many city residents, as research revealed more of what the explorer had wrought against those he encountered in the Caribbean. In the turbulent summer of 2020, when protests erupted over police brutality against people of color and Columbus and Confederate statues were being toppled and defaced nationwide, Columbus Mayor Andrew Ginther petitioned the Arts Commission to approve the removal of the Columbus statue at City Hall. The Commission voted in favor, and the statue was taken down without incident and stored on July 1, 2020. But — then what? As relieved as some residents were to see it gone, others were bereft and angry. How could the city facilitate a conversation among community members that would honor all perspectives and chart a productive path forward?

In 2023, the City of Columbus became aware of a unique funding opportunity through the Mellon Foundation's Monuments Project, a $500 million initiative launched in 2020 to “transform the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented.”1 The city partnered with Designing Local, a national cultural planning firm based in Columbus, on a proposal to “reimagine Columbus” through a 2-year research, community engagement, and design process. The Mellon Foundation awarded the city $2 million for Reimagining Columbus in spring 2023, and the project team launched an ambitious process to reckon with the statue and imagine a future in which truths about its subject are more accurately conveyed.

• The gift of a Christopher Columbus statue from the City of Genoa, Italy to the City of Columbus in 1955 was a symbol of international friendship and cooperation that established Columbus’ first Sister Cities relationship.

• During the turbulent summer of 2020, people protesting police brutality against people of color toppled and defaced statues of Christopher Columbus — who by that time had become a potent symbol of oppression and exploitation — in cities nationwide.

• Columbus’ Christopher Columbus statue was removed on July 1, 2020 in order to: 1) prevent harm to the protesters who would have torn it down, 2) prevent irreparable damage to the statue, 3) allow time for a community conversation about its future disposition, and 4) signal partnership with the city’s Black and Brown residents in addressing the city’s racial inequities.

• Reimagining Columbus is a $2 million Mellon Foundation–funded project to reckon with a statue exalting the City of Columbus’ namesake, Christopher Columbus, in order to consider a new communal space for confronting his legacy and a more broadly inclusive public art landscape in the city.

“

We shall ever cherish and be guided by its meaning.

“

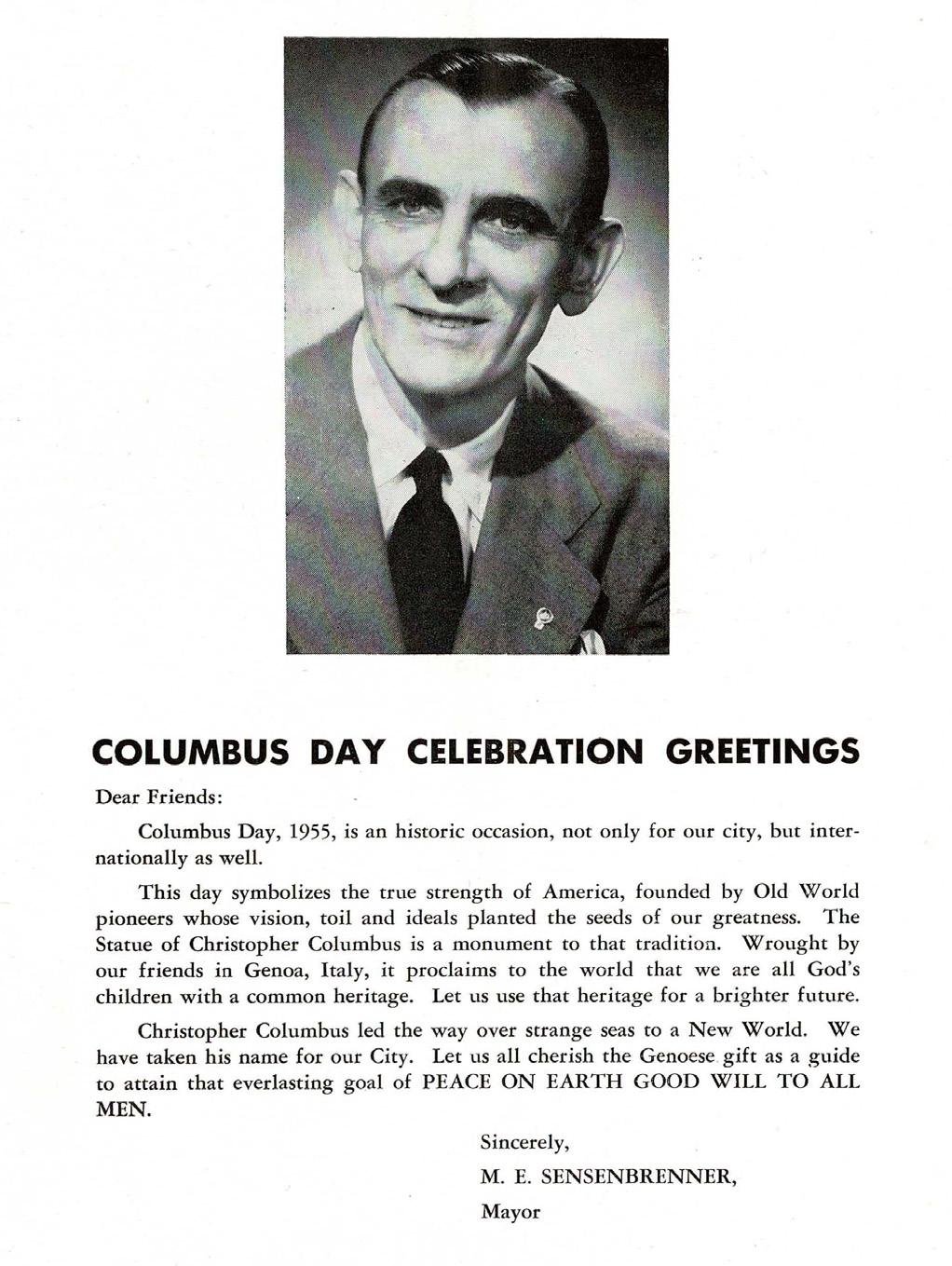

— Mayor Jack Sensenbrenner, inscription on the statue’s plaque (1955)

When it was installed during 1955’s Columbus Day celebration, Columbus, Ohio’s new Christopher Columbus statue was a unifying force that brought the city’s Italian-American community together around a common goal and forged a Sister Cities relationship with Genoa, Italy that has now persisted for 70 years. This section describes how this gift of a statue came to be and what it meant to people at the time of its installation.

In 1950, a Columbus Day wreath-laying ceremony at the state-owned Christopher Columbus statue on Capitol Square drew just 14 people. Among them was attorney Salvatore “Sal” Spalla, an Italian immigrant who worked at his family’s grocery store before serving in World War II and attending school in Columbus. Noting the size of the crowd, Sal was saddened that the largest city in the world named for the explorer did not seem to share his appreciation for the man. He set out to change that, with a multi-year campaign that ultimately included both Mayor James Rhodes and Mayor Jack Sensenbrenner’s administrations; the Italian-American community (including the Italian American Association representing 30 Italian American organizations); local, state, and federal elected officials; the Italian Consul in Cleveland; the Mayor of Genoa, Italy; and the U.S. Ambassador to Italy. This effort culminated in the gift of a Christoper Columbus statue from the Mayor of Genoa to the City of Columbus, in the spirit of friendship between the cities and to recognize the bond between Americans and Italians.2,3,4

In 1955, on behalf of the local Italian American community, Columbus Mayor Jack Sensenbrenner solicited the donation of a 20-foot Christopher Columbus statue from the City of Genoa. The request was accepted, and the city invited five artists to submit sketches for consideration.

From these, noted sculptor Edoardo Alfieri was selected to develop the piece. Alfieri researched Columbus to ensure he faithfully conveyed the gestures, clothing, and facial expression of a man for whom “the challenges of an eventful, tragic life, marked by alternating periods of glory and decline” were apparent. The sculpture showed a contemplative Columbus with his left hand resting on his chest and his right arm stretched along his side, map in hand. His clothing was inspired by the artist Luc Signorelli’s self portrait in the fresco Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist (1499–1502). His face appears troubled and resolute; it is slightly downcast. Once approved, the design was sculpted in clay, then fabricated in four sections and fused at Renzo Michelucci’s Foundry in Pistoia, Italy. It weighed more than 3 tons.5,6

A Columbus City Council resolution had directed that “special plans be made for the dedication of the statue presented by the City of Genoa, Italy, to properly acknowledge this gesture of brotherhood of significance to the entire world.”7

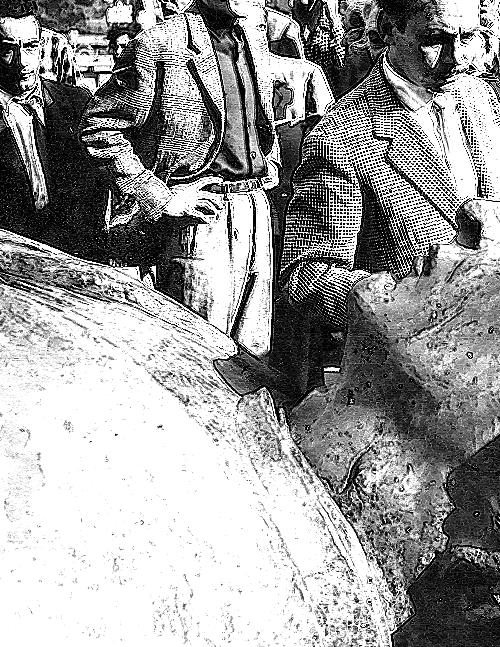

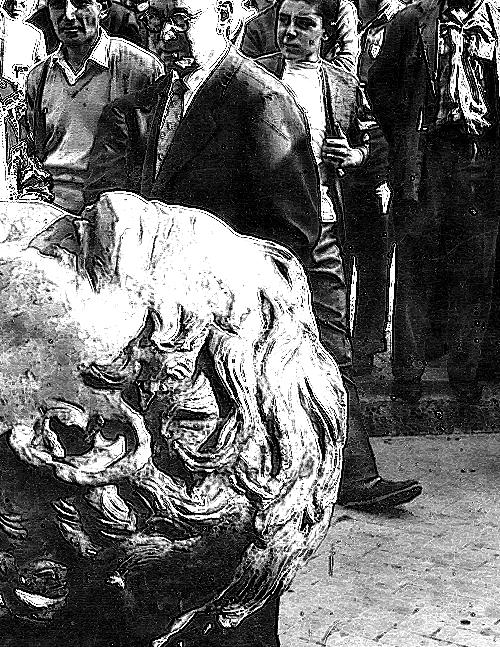

First, the massive statue had to make its way from Italy to Columbus. The statue was publicly displayed at the Port of Genoa before being packed and shipped to the U.S. aboard an Italian Line ship named, appropriately, Cristoforo Colombo. The statue was displayed at port in New York City for several days before being transported by rail to Columbus, where it was unpacked and installed on a new pedestal at City Hall in time for the city’s Columbus Day celebration.

Multi-day festivities culminated in the statue’s dedication on October 12, 1955, with a parade followed by a program at which Alfieri and the Vice-Mayor of Genoa spoke. Then, finally, the statue was unveiled.

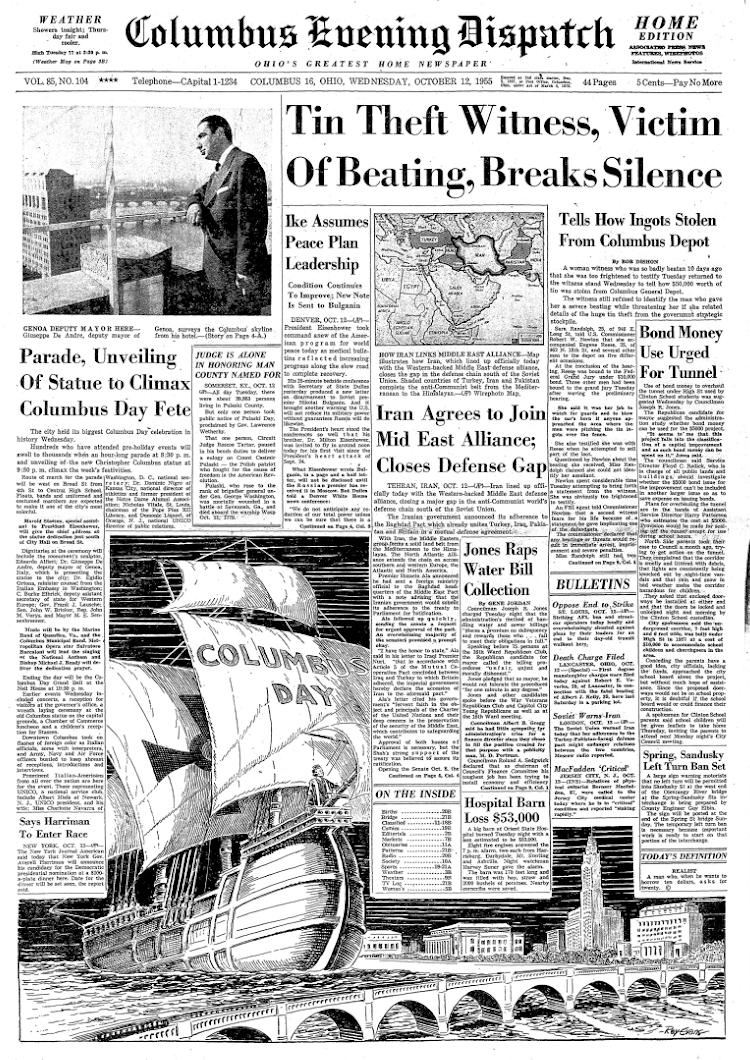

Above: FIGURE 1.4. The statue being unpacked after its journey from Italy to Columbus. Photographer unknown (1955). Right: FIGURES 1.5.–1.6. Front pages of the Columbus Evening Dispatch on the day of and day after the Columbus statue dedication.

The Columbus Evening Dispatch reported the following day:

Presidential Assistant Harold Stassen called it ‘the most thrilling and unusual Columbus Day ever held.’ And it must have come close to that. Because the city’s holiday celebration Wednesday night drew a crowd of 100,000 persons, one of the biggest in local history for any kind of event…It was a time of speechmaking and some kind of record was probably set for sheer volume of tribute to Columbus, the city and the man.8

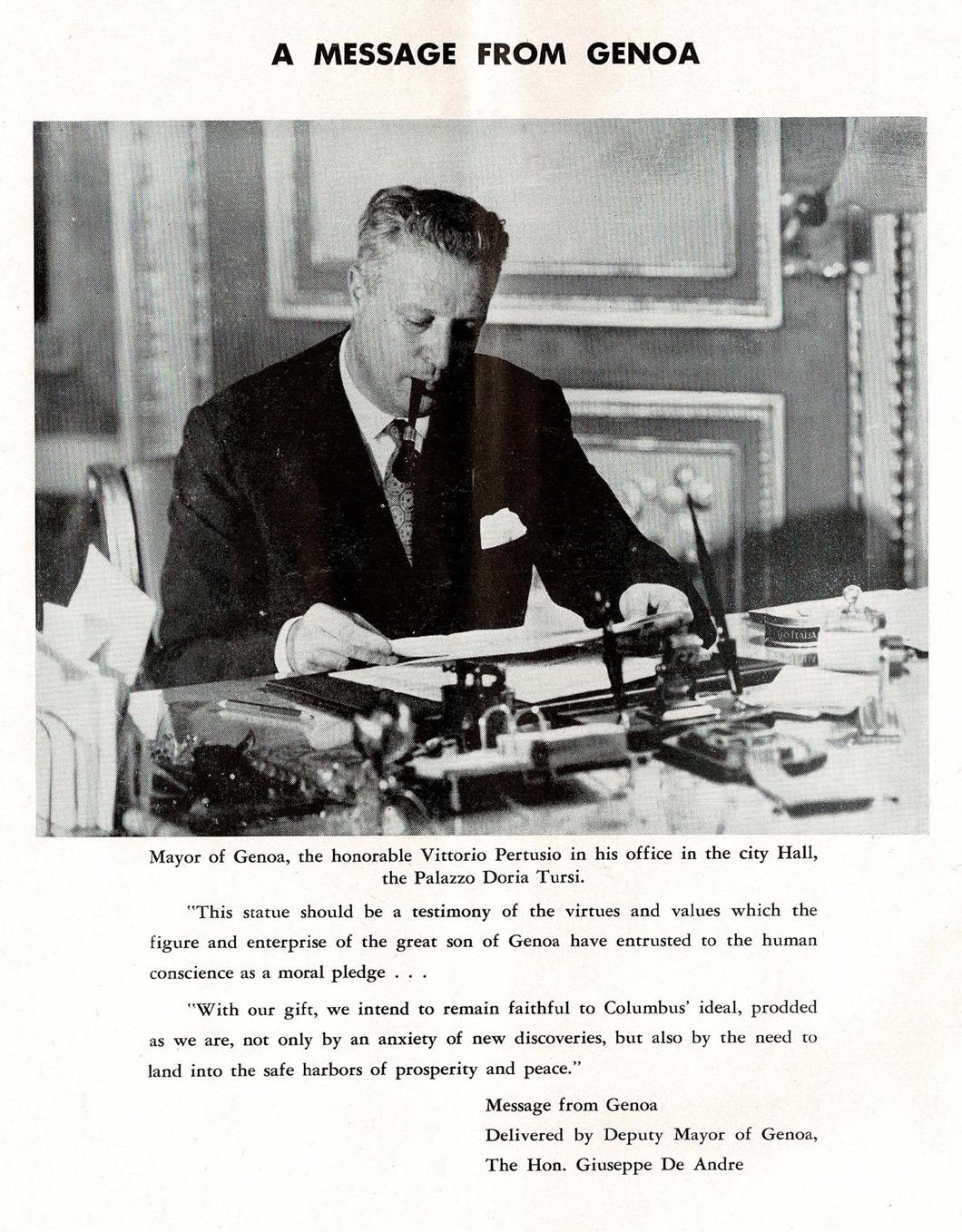

Along with the statue, Genoa Mayor Vittorio Pertusio sent a letter to Mayor Sensenbrenner of Columbus expressing good wishes “at the moment of particular significance because they convey with them a donation which is a symbol not only of a friendship between our two peoples but also a symbol commemorating the special ties between North America and our country…It is a pledge of friendship and of reciprocal esteem between our two cities.” The two cities formalized their “good wishes” toward one another later that year by codifying a Sister Cities relationship — Columbus’ first. The relationship has been maintained by the cities’ mayors for 70 years, and continues to thrive to this day.

Above: FIGURES 1.7–1.8. Pages from the souvenir program for the city’s Christopher Columbus Memorial Dedication Ceremony.

A “Sister City,” county, or state relationship is a broad-based, long-term partnership between two communities in two countries. It is officially recognized after the highest elected or appointed official from both communities sign off on an agreement. Sister city relationships offer the flexibility to form connections between communities that are mutually beneficial and address issues that partners find most relevant.

The concept evolved from partnerships between European cities forged after the first World War and accelerated after World War II when U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the People-to-People program in 1956. In laying out his case for “citizen diplomacy,” Eisenhower said,

“Two deeply-held convictions unite us in common purpose. First, is our belief in effective and responsive local government as a principal bulwark of freedom. Second, is our faith in the great promise of people-to-people and sister city affiliations in helping build the solid structure of world peace.”

Today, sister city relationships “promote peace through mutual respect, understanding, and cooperation one individual, one community at a time” through cultural, educational, information, and trade exchanges that strengthen relationships across borders.9

The City of Columbus has 10 Sister Cities as of 2025: Genoa, Italy (1955); Tainan City, Taiwan (1980); Odense, Denmark (1988); Seville, Spain (1988); Hefei, China (1988); Dresden, Germany (1992); Herzliya, Israel (1994); Ahmedabad, India (2008); Curitiba, Brazil (2014); and Accra, Ghana (2015).10

The relationships are managed by Greater Columbus Sister Cities International, a nonprofit organization established in 1996.11

Greater Columbus Sister Cities International creates exchanges and connections that promote peace and strengthen communities. The organization builds community relationships around the world through education, economic development, and arts and culture, and works to further recognition of Greater Columbus as a vibrant international region through dynamic collaborations with its global network of Sister Cities.

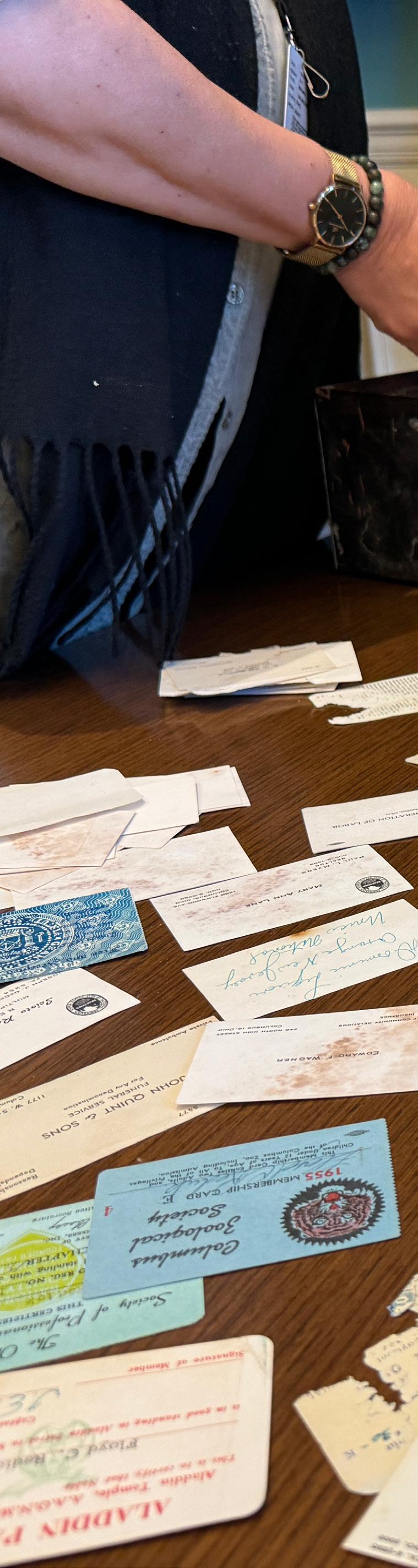

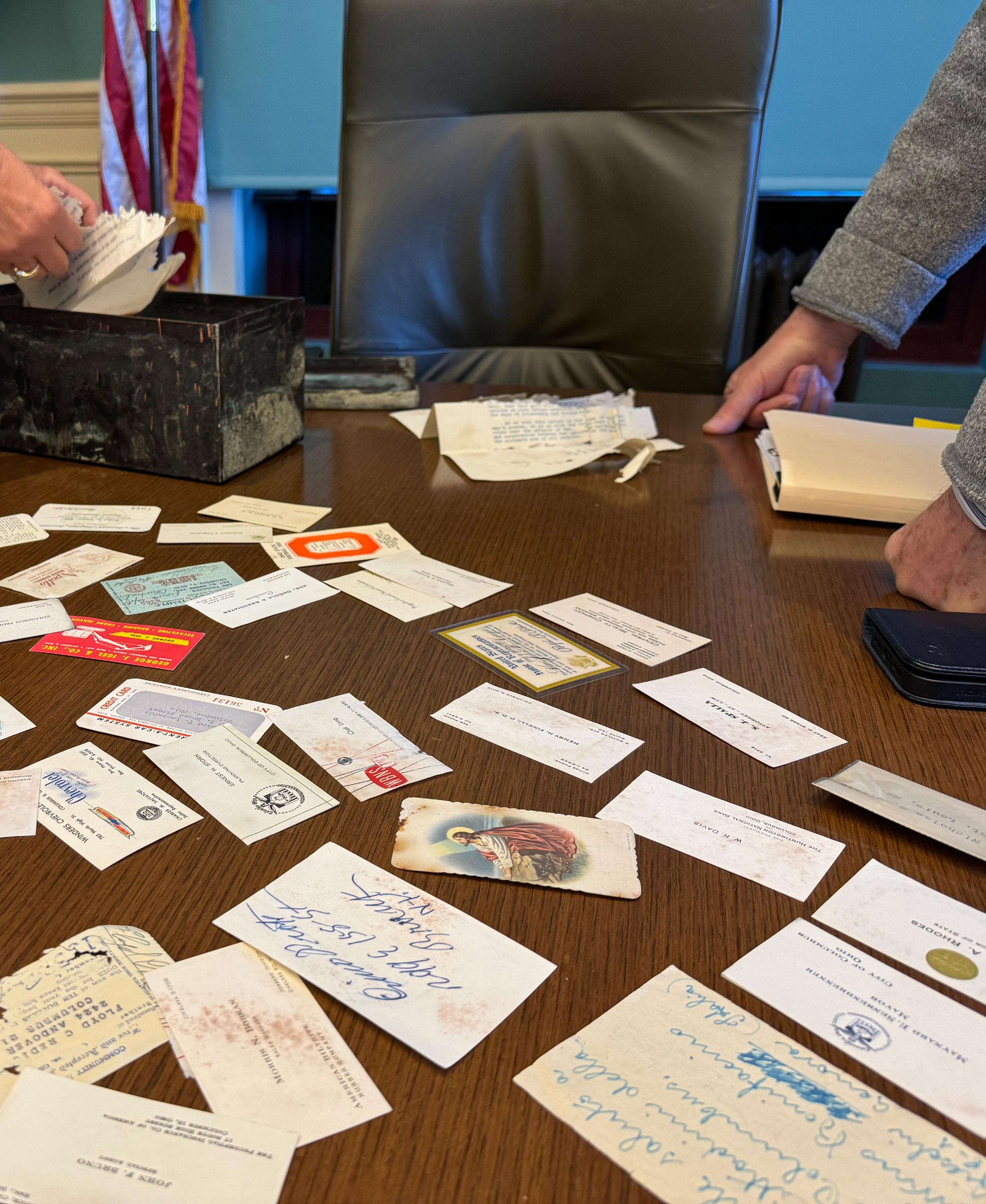

When the Christopher Columbus statue was being repaired in 1979, workers were surprised to find a time capsule had been stashed inside. The metal box included a program from the statue dedication ceremony, business cards and photographs from local supporters of the project, letters to future generations, a railroad bill of lading documenting shipment of the statue, and more. It was stored in a city office until members of the Reimagining Columbus project team gathered to rediscover its contents in December 2023. In addition to the original content from 1955, the box contained a 1979 Columbus Dispatch article about finding the box and a conservator’s report from that year. All materials from the box have now been scanned and added to the Columbus Metropolitan Library’s digital archive.

“

— Columbus Mayor Jack Sensenbrenner, from a letter in the box

“ As we seal this letter in the base of this great man's statue, we do so with the faith that a just God rules over the affairs of man. May universal peace and cooperation between nations of the world be the ultimate aim of all people.

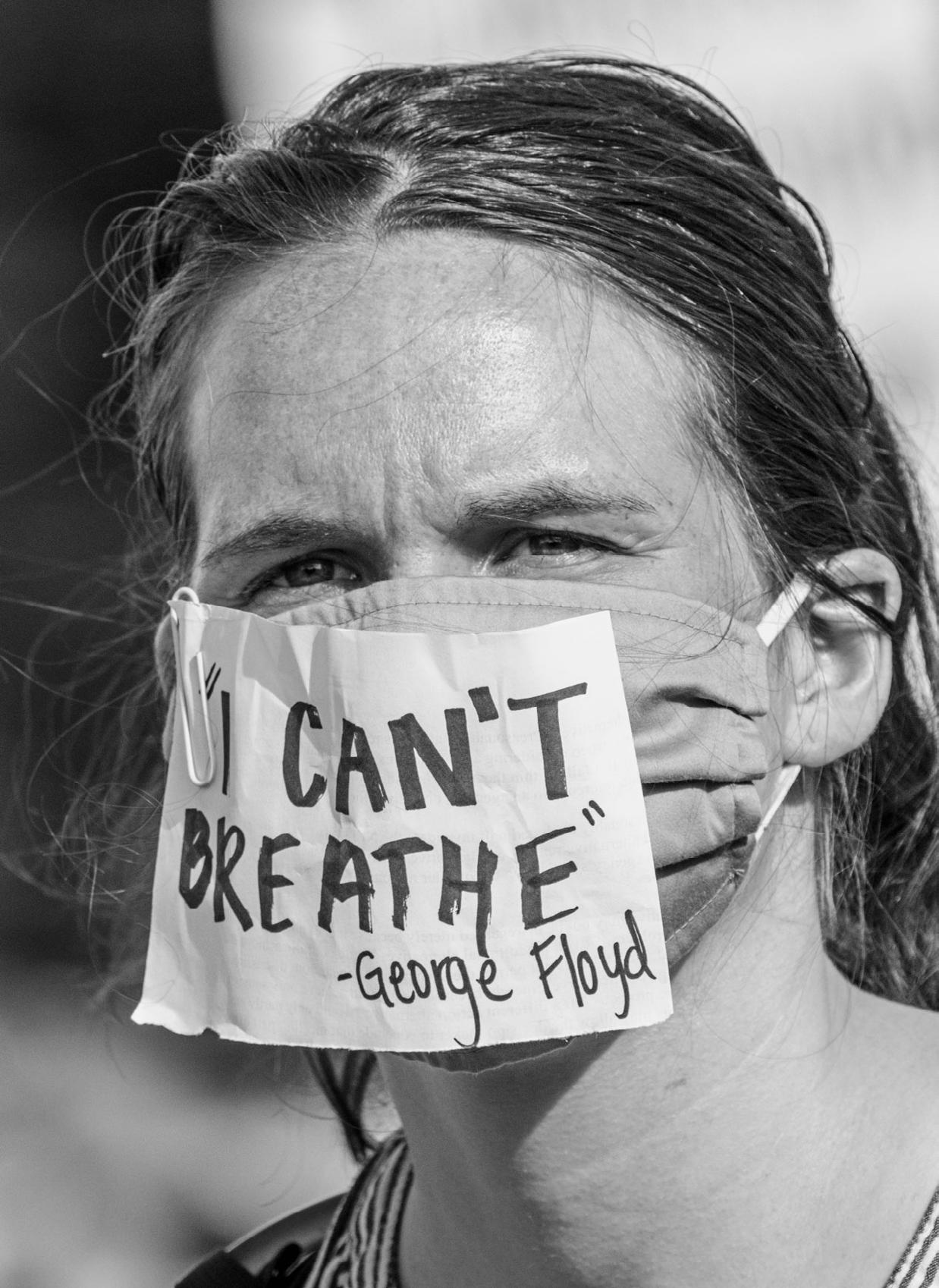

The year 2020 was marked by turbulence — nationwide and within the City of Columbus — stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and the murder of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd, by police in Minnesota. Protests of COVID shutdowns and mask mandates, and those against police brutality towards people of color, dominated downtown Columbus during that year. This section details these remarkable events and provides context for the debate over Christopher Columbus that was to come.

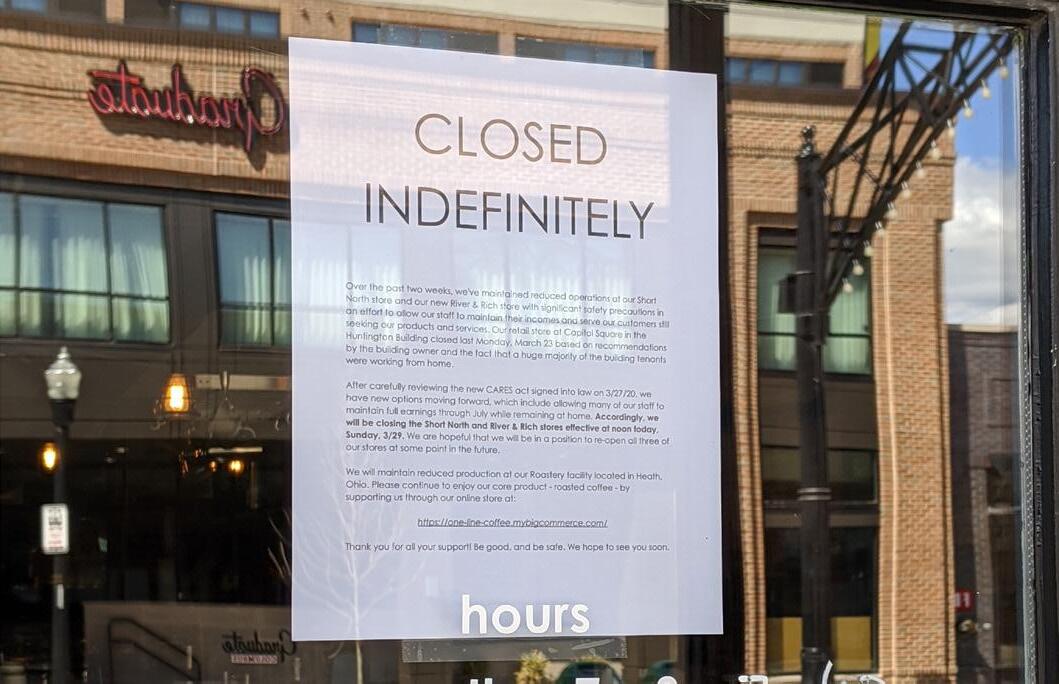

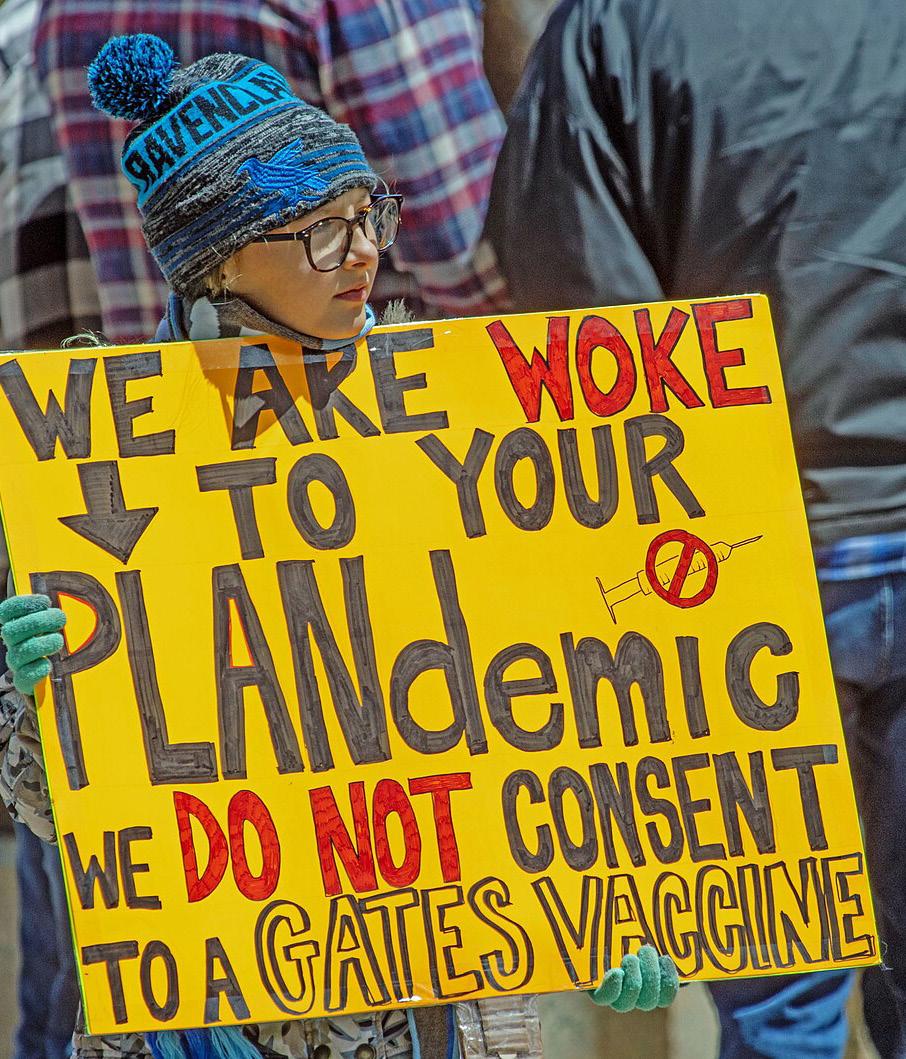

On March 9, 2020, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine announced the first cases of COVID-19 in Ohio and declared a state of emergency to limit the outbreak’s spread.12 The Columbus Board of Health issued a public health emergency on March 13, and Columbus Mayor Andrew Ginther declared a local state of emergency on March 18; the first COVID-related death in Ohio occurred March 20, and Governor DeWine gave a stay-at-home order on March 22. Within just two weeks, most businesses, schools, daycares, special events, and government agencies across the state had been shut down, and it was unclear when they would be allowed to reopen.13 These closures put many out of work, but even those who retained employment risked infection or struggled with telework, often while juggling their kids’ virtual schooling requirements. As early as April 9, protesters began showing up at the Ohio Statehouse demanding a return to normal life, with signs such as “Survival is not living” and “Quarantine worse than virus.” 14,15 The protests only grew more heated as it became clear that the virus spread via airborne transmission, leading Mayor Ginther to institute a face mask mandate on July 2.

Any semblance of return to prepandemic life would not occur in Columbus until almost two years after the state first shut down�

A vaccine against the virus became available for high-risk populations in December 2020, but efforts to mitigate the COVID-related caseload and prevent a collapse of the healthcare system took their toll in the meantime, and for months thereafter. Businesses were gradually allowed to reopen beginning in May of 2020, but with restrictions that proved impossible for some to navigate. The entire 2020–2021 school year was undertaken remotely by Columbus City Schools students. Non-essential healthcare procedures were postponed, leading to poor outcomes for many. The city’s mask mandate was not repealed until March 2022. Franklin County ultimately experienced 370,823 COVID-19 cases and 2,881 COVID-related deaths,16 as well as above-average mortality from multiple causes that are not yet fully understood.17

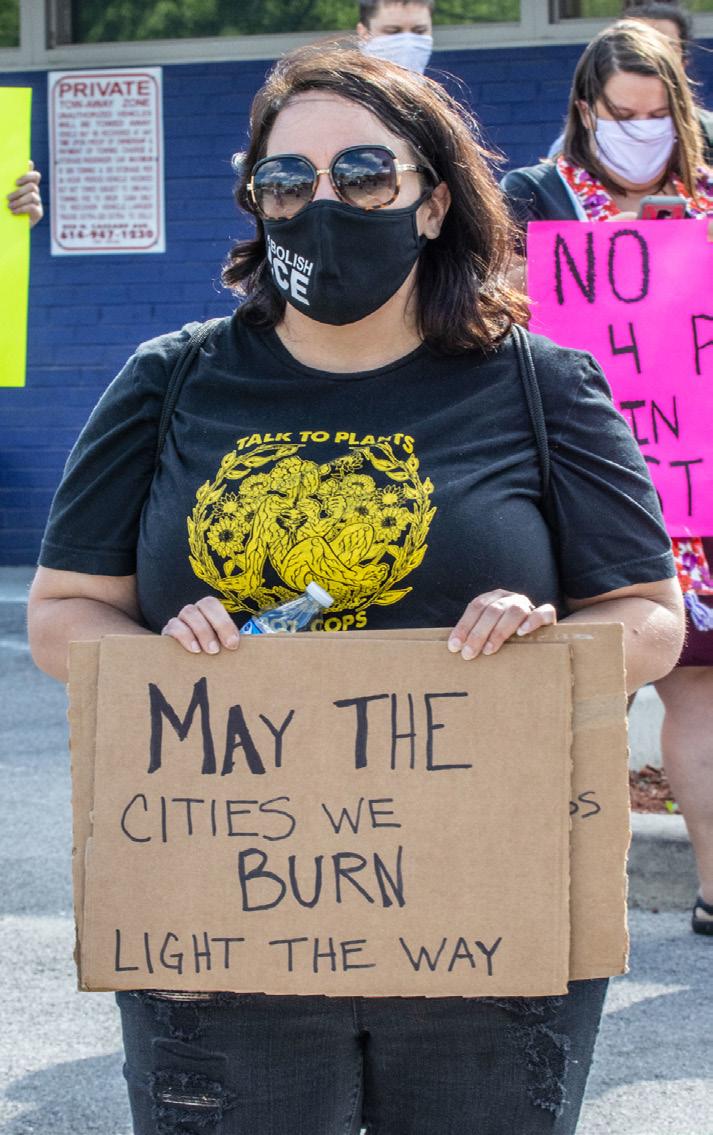

Protest and pandemic scenes from Columbus in 2020. Clockwise from top left: FIGURE 2.1. Photo by Paul Becker (July 9). FIGURE 2.2. Photo by Paul Becker (June 2). FIGURE 2.3. Photographer unknown (March 29). FIGURE 2.4. Photo by Paul Becker (May 9). FIGURE 2.5. Photo by Paul Becker (May 29). FIGURE 2.6. Photo by Paul Becker (July 18). FIGURE 2.7. Photographer unknown (April 18). FIGURE 2.8. Photo by Paul Becker (May 29).

In Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020, an unarmed Black man named George Floyd was arrested by three police officers on suspicion of attempting to pay for cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. Two police officers pinned him on the ground while Officer Derek Chauvin placed a knee on his neck for more than eight minutes, ignoring both Floyd’s cries that he could not breathe and the gathering crowd calling for his release.18 A video of the interaction taken by a bystander went viral, and protests against police brutality erupted nationwide. In solidarity with these actions and in frustration with their own experiences at the hands of law enforcement, local #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) activists organized protests against police brutality that began on May 28, 2020 in downtown Columbus and continued through June. The Columbus Division of Police used pepper spray, tear gas, wooden baton rounds, sponge rounds, and other tactics in an attempt to quash the mostly-peaceful protests, severely injuring many and leading to a $5.75 million settlement with 26 injured plaintiffs, as well as an injunction on the use of several forms of non-lethal force against protesters going forward.19

This heavy-handed response to the protest was largely in keeping with police conduct in Franklin County during the years preceding it. Between 2015 and 2020, the county was found to have one of the highest rates of fatal law enforcement shootings in the country, ranking 18 th out of the 100 most populous counties nationwide. In 2020 alone, 5 people — 2 unarmed — were killed: Joshua Brown, Abdirahman Salad, Joseph Jewell, Casey Goodson Jr., and Andre Hill.20 A separate 2019 report found significant disparities in how force was used against Black versus non-Black residents and revealed that almost one-third of survey respondents within the Columbus Division of Police had witnessed an act of discrimination against a member of the public. 21

Columbus experienced 51 homicides from June to August of 2020, more than the previous two summers combined;22 in 2020, there were 175 homicides in the city, compared to 105 in 2019.23

Researchers cite a number of factors that may have contributed to increased violence during the pandemic, among them the loss of jobs, income, schooling, government support, and loved ones; an increase in available guns; and stress from social factors including racial tension, boredom, and isolation.24,25 As with the COVID pandemic and police brutality, the impact of community violence was disproportionately felt in Columbus’ poor, Black-majority neighborhoods.

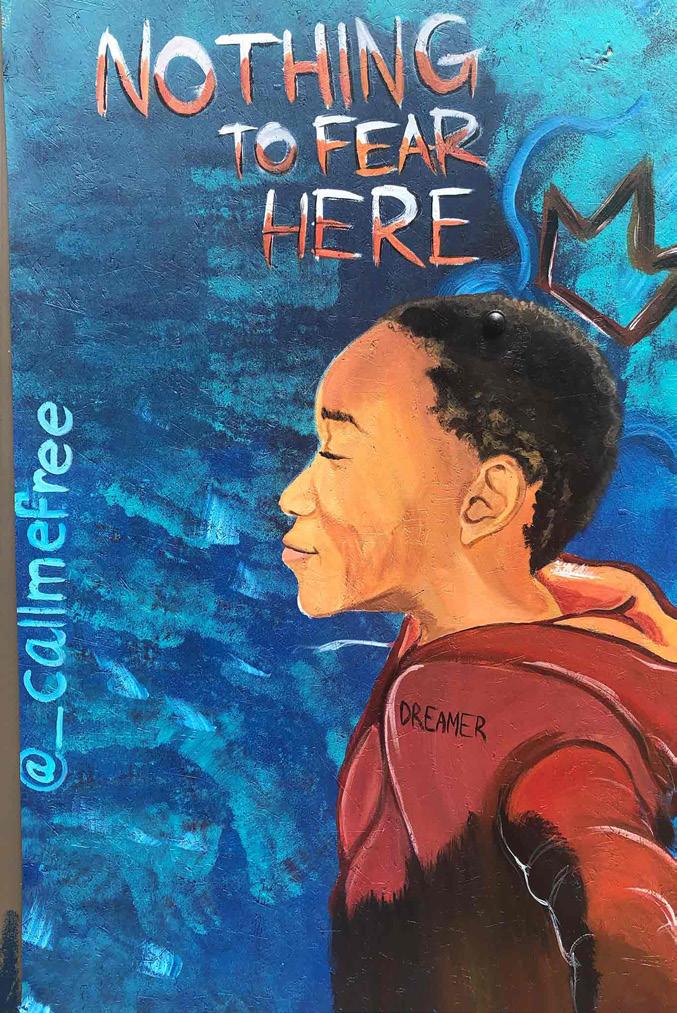

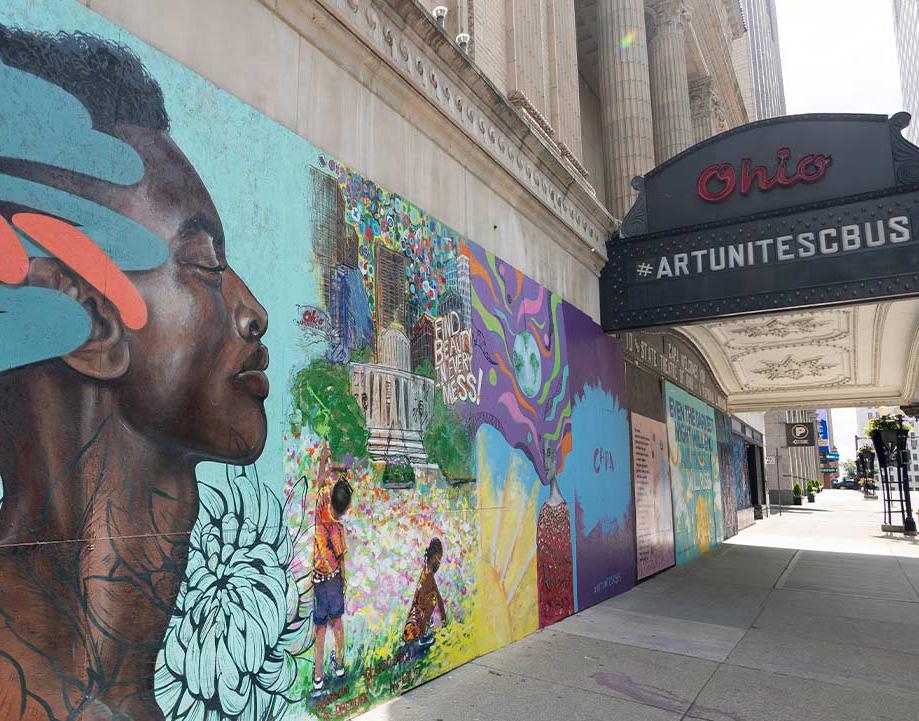

After the initial demonstrations following George Floyd’s death, downtown-area businesses installed sheets of plywood to shield broken windows and prevent new damage to their storefronts. Local nonprofit organizations quickly partnered to hire Columbus-based artists to create murals on these blank plywood canvases, and soon larger businesses joined the effort. By the end of June 2020, more than 200 murals featuring support for Black Lives Matter, grief and outrage at the loss of life to police brutality, and messages of peace and love had been painted on plywood throughout the city. This unique gallery of work brought hope and inspiration to a difficult chapter in Columbus’ history. It has been preserved at the website artunitescbus.com by the Columbus Association for the Performing Arts and the Greater Columbus Arts Council.26

Top left: FIGURE 2.16. Artists in front of their “Empathy” mural. Muralists Hakim Callwood, Kayneisha Holloway, Bryan Moss, and Ariel Peguero. Photo by Max Rodriguez (June 2020).

Bottom left: FIGURE 2.17.

“Nothing to Fear Here,” artist Francesca Miller, photographer unknown (June 2020). Above: FIGURE 2.18. Series of murals at Ohio Theatre. Artists Miss Birdy, Laurie Clements, Brenden Spivey, Wil Wong Yee, and others. Photographer unknown (June 2020).

During the protests against police brutality in summer 2020, Christopher Columbus and Confederate statues in many other cities were vandalized and forcibly removed from their pedestals. During Black Lives Matter protests in Columbus that June, it became clear that the statue at City Hall risked a similar fate. This section discusses how city leaders came to the conclusion that the statue needed to come down, and what happened once they did.

One of the first protests against Christopher Columbus in the City of Columbus occurred in response to its Columbus Quincentenary Jubilee celebration in 1992. With no Indigenous representation on the festivities’ planning committees, events highlighted Columbus’ accomplishments and ignored the suffering he caused Indigenous peoples. For two weeks prior to Columbus Day that year, Indigenous activists and allies camped out in front of City Hall, fasting, praying, and singing in an attempt to force acknowledgment of the brutality Columbus inflicted. On October 13, 1992, 150 protesters gathered in nearby Bicentennial Park and marched to the city’s newly installed Santa María replica ship, where a mourning ceremony was held. Each year thereafter, Indigenous advocates in Central Ohio organized fasts, walks, and other forms of peaceful protest to mark Columbus Day.27 Mark Stansbery of the Community Organizing Center for Mother Earth said, “We don’t come here to bash the individual. We want to put it in historical perspective, to keep a counterbalance.”28 Nevertheless, the non-Indigenous response to these protests included hostility, death threats, and derogatory jokes and comments about Indigenous culture. 29

After almost 30 years of protest by the local Indigenous community, it was the Black Lives Matter (BLM)/George Floyd protests of 2020 that prompted the City of Columbus to more deeply consider the impact of its Christopher Columbus statue, especially given its place of prominence in front of City Hall. While there was internal debate as to how relevant the misdeeds of a 15th-century explorer were to the present-day concerns of local Black citizens protesting police brutality, city leaders could see that Christopher Columbus statues had become flashpoints for protest nationwide. As these statues were toppled and vandalized in other cities, they further began to understand that their statue would come down, one way or another — and that it needed to. BLM activists had indeed made the connection between their lived experience of oppression and the city’s ongoing exaltation of an oppressor.

...while it’s not something that I thought about much…for a lot of people in our community [the Columbus statue] was a symbol of something that had gone unspoken and left untouched for way too long, and it stirred very deep emotion. And it made it very difficult for them to view the City as credible and as a partner, as someone willing to engage, to do better, as long as it was standing…It was making it difficult to just have that next conversation, to get to a point where we could begin healing, where people were actually leaning in together to make change. And as long as it was standing right there, we weren’t ever going to get to where we were trying to go.30

— Ken Paul, former Chief of Staff for Mayor Ginther

“I’m sorry, whose? Whose pride are you talking about? Because it wasn’t ours. Because our community was being tormented. And that flag is a constant reminder of that torment. This statue is a constant reminder of that torment.31

— Local activist Adrienne Hood, telling a story about her response to a colleague saying the Confederate flag was “about pride” and connecting it to the Columbus statue

The decision to remove the city’s Christopher Columbus statue ultimately came down to several factors. Above all, city leaders did not want protesters to injure themselves toppling the statue, and they did not want the statue irreparably damaged. Removing the statue would allow time for reasoned conversation about it, and signal to the city’s historically marginalized residents that this conversation, as well as others on more pressing issues such as policing reform, would be conducted in good faith. The statue’s removal was not considered a solution in and of itself, but rather a necessary step to move the conversation towards healing and forward progress on mutual community goals.32

For many people in our community, the statue represents patriarchy, oppression and divisiveness. That does not represent our great city, and we will no longer live in the shadow of our ugly past. Now is the right time to replace this statue with artwork that demonstrates our enduring fight to end racism and celebrate the themes of diversity and inclusion. By replacing the statue, we are removing one more barrier to meaningful and lasting change to end systemic racism. Its removal will allow us to remain focused on critical police reforms and increasing equity in housing, health outcomes, education and employment.

Columbus City Council is focused on eradicating systemic racism, police misconduct and social injustice through every means possible. While that is our daily focus, we also hear the raised voices in the streets regarding this monument to Christopher Columbus. Removal and replacement of the statue will not feed families or end racism. We understand this statue is also a symbol of oppression and enslavement. We support it moving and will work with residents to ensure that new public art at this site and memorials all around our city celebrate the best of us, our cultures and our dreams for the city we are working to build together.33

“

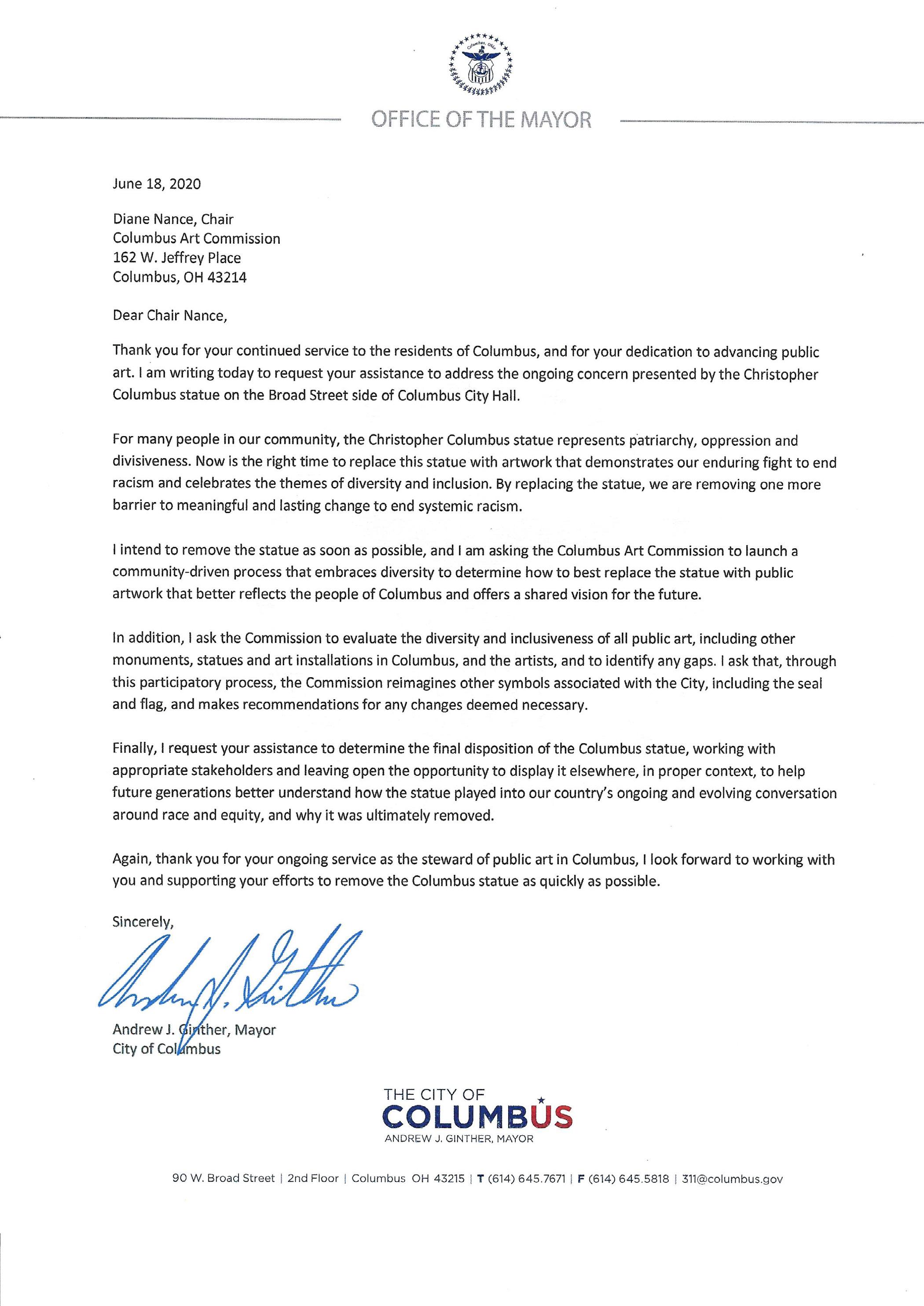

Because the Christopher Columbus statue is part of the City of Columbus’ public art collection, its disposition cannot be dictated by the Mayor or City Council; rather, "The Columbus Art Commission has statutory authority over the design and placement of all works of art to be acquired by the city, placed on land owned or leased by the city, or placed anywhere in the public right-of-way." 34 Among the Commission’s official duties is to “review, examine, and consider the removal, relocation or alteration of any existing work of art in the possession of the city,” and Commission approval is required for “any change to the design or placement of any art subject to Commission approval” (Chapter 3115, Columbus Code of Ordinances; full text in Appendix).35 Therefore, Mayor Ginther submitted a letter to the Commission on June 18, 2020 stating his intention to remove the statue and place it in storage, and requesting approval for these actions. Commission members unanimously affirmed the statue’s removal at their meeting June 24, and the statue was safely taken down on July 1. Though it was removed from public view and remains in storage as of 2025, the statue has not been deaccessioned by the Commission (that is, officially removed from the City of Columbus’ public art collection). 36,37

Call to Order (3:30 p.m.)

Applications

Application: # 20-06-01

COLUMBUS ART COMMISSION VIRTUAL HEARING Streamed to the City of Columbus YouTube Channel

Applicant: Department of Finance

Artist: Eduardo Alfieri

Matter before the Columbus Art Commission:

On June 18, 2020, Mayor Ginther announced that the Christopher Columbus Statue on the south plaza of City Hall would be removed As with many cities across the country, historical sculptures and their representation in contemporary America are undergoing reassessment. The sculpture of Christopher Columbus was given to the citizens of Columbus by the people of Genoa, Italy in 1955 in, “…light of the historic bonds of friendship between the American and Italian peoples.” The gift was accepted by the City of Columbus, “… as an expression of friendship and goodwill between two cities…”

It is often difficult to determine when a permanent work of art is no longer appropriate, yet the community has made it clear that the time is right to remove the sculpture, as its purpose and goodwill extended to the City some 65 years ago, now represents pain and destruction for many. Support for the Mayor’s determination to remove the statue is requested

Presenting to the Commission:

Kathy Owens, City of Columbus Department of Finance

Barry Bryant, City of Columbus Department of Finance

#1 Motion to be considered:

A motion to support the resolve of the Mayor to have the Christopher Columbus sculpture moved from its current location and to recommend an experienced art handler supervise removal and storage of the piece in an indoor location until its disposition is determined.

Commission discussion of the motion

Public Comment

Chair Calls for a roll call vote on the motion

Additional Matters before the Art Commission:

Mayor Ginther, in his recent LETTER to CAC Chair, Diane Nance, shared his decision to remove the sculpture and requested the Art Commission undertake the following actions:

1. Launch a community-driven process that embraces diversity to determine how to best replace the statue with public artwork that better reflects the people of Columbus and offers a shared vision of the future;

2. Evaluate the diversity and inclusiveness of all public art, including other monuments and statues in Columbus and the artists, and other symbols associated with the City, including the seal and flag, and to identify any issues of concern;

3. Determine the final disposition of the Christopher Columbus statue, working with appropriate Stakeholders and leaving open the opportunity to display it elsewhere, in proper context.

In recognition of Mayor Ginther’s decision to remove the Christopher Columbus statue, as outlined in his letter dated June 18, 2020, the Columbus Art Commission hereby resolves to undertake resolution of the actions requested by Mayor Ginther as outlined above. As the Commission begins to clarify its approach and undertake these actions, it requests that the Administration be aware that additional resources may be needed and requested, in order to carry out the Mayor’s requests in the good faith with which they were requested.

Commission discussion of the motion and actions listed above, in the following order:

1. Evaluation of the city’s art collection for diversity and inclusiveness within the context of a 21st century city;

2. Inclusion of the review of city symbols including the flag and seal within the review of the collection;

3. Determining the final disposition of the Christopher Columbus statue; and

4. How best to replace the statue with new public artwork.

Public comment

Chair Calls for a roll call vote on the motion

Please note: The Art Commission is beginning a discussion of, and laying the groundwork for, the next steps in what will be an inclusive process embracing the diversity of our City.

Other Business:

Next scheduled Commission hearing

• July 15, 2020, Third Wednesday at 3:30 Virtual Webex Hearing Streamed to the City of Columbus YouTube Channel l

• Adjournment

3.7. Agenda of the Art Commission’s meeting to discuss Mayor Ginther’s directives regarding the Columbus statue.

With the statue safely in storage, attention turned to the question of what to do next. The community was divided as to whether it should remain hidden away or be reinstalled, and it was unclear whether or how such sharply divergent, emotionally-laden opinions could ever be reconciled. This section provides a broad outline of how people reacted to the statue’s removal and how city leaders wrestled to productively address the discord.

Given the controversy surrounding Christopher Columbus and the polarization of modern America’s political landscape, reactions to removal of this statue were mixed. There were varied, ambivalent, and contradictory opinions about how the statue should be handled, even among the groups most affected by it. For example, some Black Lives Matter activists were thrilled it came down, but others argued that removing the statue directed attention away from real, substantive problems in Black and Brown communities. Some Italian Americans were angry that their hero was removed from public view, while others were eager to explore a different way to honor their heritage. Many Indigenous community members were relieved to see the statue gone, but some felt it to be merely a symbolic gesture. Others within the community believed that removing statues erases history and represents acquiescence to radical social elements — and where does it stop, because aren’t most historical figures problematic in some way? No doubt there were plenty who did not care one way or another, and additional perspectives beyond these. Understanding that the debate was complex, then, what follows is an attempt to articulate the prevailing views of those who advocated for the statue to be removed and those who insisted that it be reinstalled at its original location.

Indigenous and Black Lives Matter activists in Columbus were among the most dedicated to seeing the Christopher Columbus statue removed and, preferably, kept from public view. Their reasoning was that modern scholarship has revealed Columbus committed unconscionable atrocities against the Taíno peoples he encountered in the Caribbean — including rape, enslavement, and genocide — and he should no longer be exalted as a hero. To their minds, a society that continues to honor Columbus today is one that knowingly embraces his full legacy of oppression and, by extension, the oppression they continue to suffer. The violence the statue represents is not an abstraction for them; rather, it is a lived experience of being valued less than their White neighbors and dealing with the everyday and long-term consequences of this. Its presence, especially in a place as prominent as City Hall, is a clear indication that their suffering does not matter, that they are not welcome in this place.

Just seeing [the statue] there is enough for me to feel even less welcome, just because it shows that the people — not necessarily all the people, obviously, but the people with the power and the influence to erect these statues — don’t see any problem with it, and they believe that it needs to be up. That's enough for me to feel unwelcome or uncomfortable. So I think [the statue] being taken down is very symbolic, and very important.38

— Lakaya Deegan, President, Native American and Indigenous Peoples Cohort (a student organization at The Ohio State University)

Second- and third-generation Italian Americans in Columbus have offered the most organized resistance to the Christopher Columbus statue’s removal. Their ancestors were deeply committed to advocating for the statue and helping fund its installation and maintenance. Therefore, as celebrated as the statue’s removal was within some communities, many local Italian Americans were angered by the perceived slight against their hero and, by extension, their heritage, sacrifices, and contributions to the City of Columbus. These community members want the statue to be returned to its former location or, if a transfer could be negotiated, to private property under their control. Italian-American community organizations voiced this position through public statements:

“The contributions of Italian Americans are under attack in Columbus, Ohio. Through a series of recent events the history, culture and contributions of Italian Americans have come under attack in our community and in the city of Columbus, Ohio — the largest city in the United States named “Columbus.”

Collectively these actions [the statue removal, the decision not to observe Columbus Day, and the renaming of Christopher Columbus Park] offend many citizens of Central Ohio. They marginalize the contributions of Italian Americans and immigrants in general to the founding, growth and prosperity of Columbus and Central Ohio. They disrespect the sacrifices that Italian immigrants and Italian Americans have made while disregarding the history and symbolism that are associated with the statue, the holiday and the name Christopher Columbus.

The Christopher Columbus Park, the statue of Christopher Columbus, and the observance of Columbus Day represent far more than one man, they represent the Italian American community at large as well as the immigrant experience in general.39

“— Online petition, the Columbus Italian Club (2021)

In response to Mayor Ginther’s directive to conduct a communitydriven process to determine what to do with the Columbus statue, the Columbus Art Commission established a 14-member Christopher Columbus Statue Committee and held 5 community meetings from April to August, 2021 to discuss the topic.40 In November of that year, the Committee and the Art Commission officially recommended that the city hire a consultant to identify three draft design proposals for a future reinstallation of the statue, on a site other than City Hall, with narrative text to appropriately contextualize it.41 The city released an initial RFP for this task on December 16, 2021, then re-released it on April 11, 2022.42,43 In July 2022, the Columbus-based firm Designing Local, Ltd., which specializes in creating arts and culture plans nationwide, was set to be awarded a $253,000 contract to facilitate this process. On July 25, however, in the face of opposition from the Italian-American community, City Council tabled the ordinance authorizing this contract indefinitely, to allow time for more community discussion. 44

allowed community members to listen, learn, and be heard in an extended conversation about their histories and values, in service of a more nuanced and responsive statue presentation. This section describes Reimagining Columbus and how it was designed to elicit a productive path forward on a deeply controversial topic.

It had become clear that the conversation about what to do with the city’s Christopher Columbus statue called for a more intensive, sensitive community engagement process than had been attempted previously. When a funding opportunity for "reparative, community-driven actions around existing monuments, including contextualization, relocation, removal, and community visioning and engagement for sites of removed or relocated monuments,”45 became available through the Mellon Foundation in early 2023, the City partnered with Designing Local to submit a proposal for Reimagining Columbus, an initiative to use community engagement, historic and contemporary research, and design studies to inform decisions on city symbols, new public art, and the fate of the Columbus statue. In June 2023, Columbus received a 2-year, $2 million commitment from the foundation; the City of Columbus also committed $1.5 million towards new public art for the grounds of City Hall at that time.46

SCAN THE QR CODE TO VIEW THE FULL GRANT APPLICATION ON THE REIMAGINING COLUMBUS PROJECT WEBSITE.

Today, we take the next step in rewriting our narrative. We take responsibility to tell the truth about colonialism and racism, and to tell the stories of the people who have been overlooked and erased from the telling of our history. I invite the entire community to join us in an inclusive discussion that will allow us to re-envision how we project ourselves to the world and create a symbolic landscape that more closely resembles our shared values and aspirations for our future.47

— Mayor Andrew J. Ginther

I’m so hopeful this process can teach us how — how to have these conversations, in a way that people can feel heard but we talk about the hard stuff. Right now it’s a conversation about symbology, but how can we have the conversation about violence, how can we have the conversation about infant vitality, how can we have conversations about the other change we want to see in our community? I’m excited that this can teach us that.48

— Jennifer Fening, City of Columbus

“

Monuments and memorials — the statues, plaques, markers, and place names that commemorate people and events — are how a country tells and teaches its story. What story does the commemorative landscape of the United States tell? Who are we instructed to honor and uplift, and who do we not see in these potent symbols? Does the civic landscape show an accurate picture of our nation, or propagate a woefully incomplete story?

Today, our public realm disproportionately celebrates a limited few and overlooks the multitudes who have made and shaped our society, limiting our understanding of our collective history. This failure to represent our multiplicity impacts how we perceive, distribute, and demonstrate power in the US.

The Monuments Project is an unprecedented multi-year commitment by the Mellon Foundation that is aimed at transforming the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented. Launched in 2020 as a $250 million initiative — and doubled in 2023 to $500 million — the Monuments Project supports efforts to express, elevate, and preserve the stories of those who have often been denied historical recognition, and explores how we might foster a more complete telling of who we are as a nation. Grants made under the Monuments Project fund publicly oriented initiatives that are accessible to everyone and promote stories that are not already represented in commemorative spaces. All grants under the Monuments Project are distributed across defined areas of activity:

• Fund new monuments (broadly defined), memorials, and historic storytelling spaces;

• Support reparative, community-driven actions around existing monuments, including contextualization, relocation, removal, and community visioning and engagement for sites of removed or relocated monuments;

• Facilitate the production of storytelling and engaged scholarship (e.g., public and oral history, podcasts, websites, and digital technologies) that inform public understanding of how commemorative landscapes communicate, shape, and teach our history; and

• Advance research that informs and supports practitioners, policymakers, and others working to transform the commemorative landscape.49

*This content was pulled from the Mellon Foundation website.

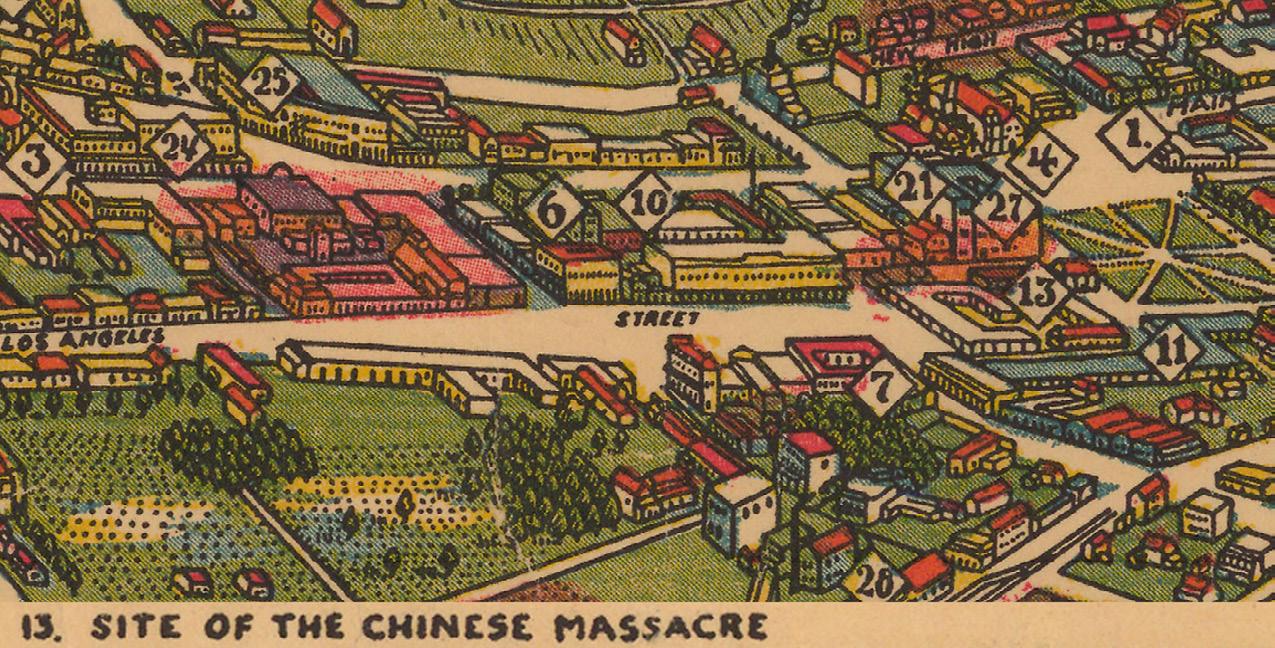

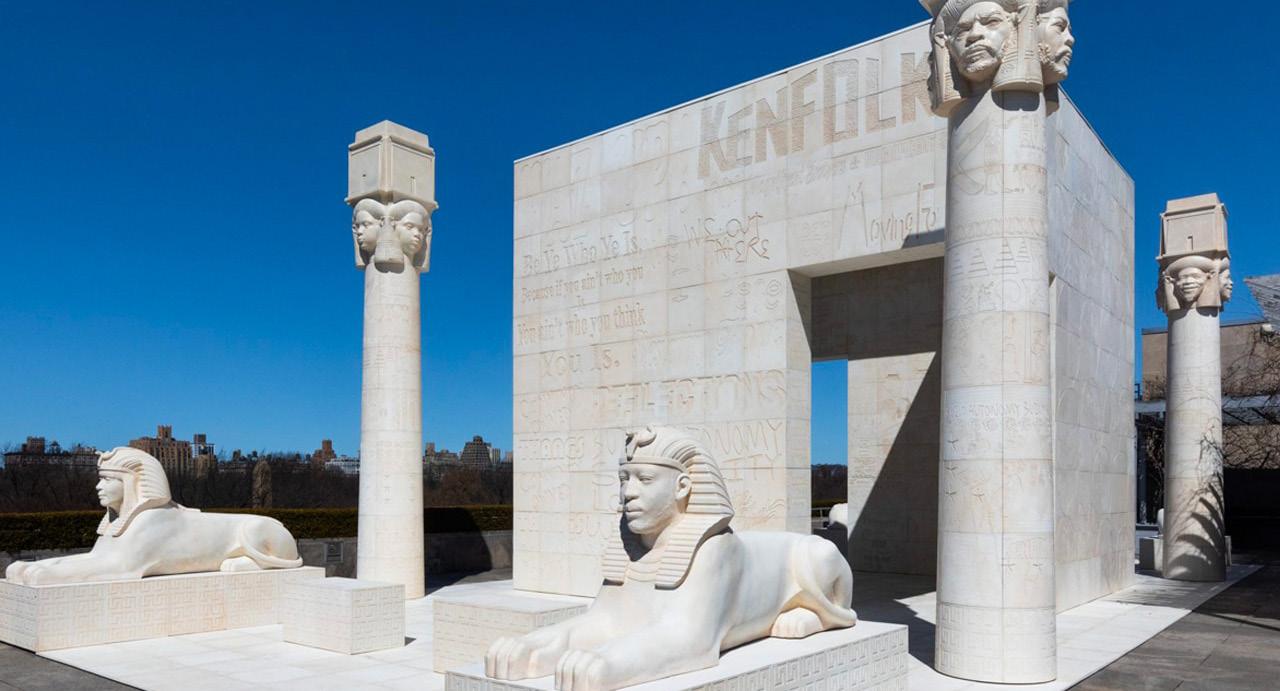

Examples of other projects funded by the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project.

Top left: FIGURE 5.2. Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument. NPS Photo (2020).

Top right: FIGURE 5.3. Map of Los Angeles depicting the site where 18 Chinese men and boys were massacred (1871). Middle: FIGURE 5.4. The Twin Falls farm labor camp. Photo by Russell Lee (July 1942). Bottom: FIGURE 5.5. Halsey, Lauren. the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (I), photo by Hyla Skopitz (both 2022).

Reimagining Columbus was a bold initiative to confront the City of Columbus’ history and build a more inclusive future for all residents, through community conversations centered around the city’s Christopher Columbus statue. Starting with the understanding from Mayor Andrew J. Ginther that the statue would not return to the campus of City Hall and that it would instead be recontextualized and placed elsewhere on public property, the project team was tasked with incorporating community feedback, research into colonial and contemporary history, and best practices in placemaking to cast a vision for how a new statue site should look and feel, how visitors might interact with it, and how the site could engender profound experiences that reverberate for generations. This process presented the City of Columbus with the opportunity to design a preeminent gathering space for visitors to learn hard truths about Christopher Columbus and heal from the harms of his legacy, including ways the city itself perpetuated harm against its citizens by embracing the explorer. A parallel process to create an art plan for City Hall Campus identified recommendations for replacing the Columbus statue with art to inspire all residents.

• PHASE 1: Launch, Administration & Planning

November 2023–January 2024

• PHASE 2: Research, Learning & Community Education

January–September 2024

• PHASE 3: Community Dialogue March–September 2024

• PHASE 4: Synthesis

October–November 2024

• PHASE 5: Design Concepts

November 2024–August 2025

• PHASE 6: Art Plan for City Hall Campus April–August 2025

Per the grant application, Reimagining Columbus was conceived with the following goals:

• Methodically and inclusively host conversations to understand what Columbus residents value most, and how the city’s future symbology and public art landscape can communicate shared values and aspirations

• Provide the public with opportunities to collaboratively ideate on the future disposition of the Christopher Columbus statue and, with requisite community buy-in, design a new space that allows the public to understand and physically interact with difficult history

• Create a replicable model for dealing with difficult topics within the community and pilot new community engagement methodologies, including restorative practices

The Reimagining Columbus project team would deliver the following:

• A series of learning exchanges to provide context regarding Christopher Columbus, the statue of his likeness and public perceptions of it, and the city’s relationship with its namesake, with original videos and reports posted to the project website (see Book 2)

• A unique model of public engagement, with original videos documenting many of the community conversations posted to the project website, and a guide for how to employ this model in future projects (see Book 3)

• Conceptual designs of a new space in which to display and contextualize the statue (see Book 4 and Book 5)

• An art plan for City Hall Campus (see Book 6)

The following team was constituted at the outset of Reimagining Columbus. With support from the Mayor’s office, the City of Columbus’ Department of Development was ultimately accountable for project outcomes.

CULTURAL COMPETENCY COMMITTEE

Dr. Christina Benedetti Historian

Erin Blue City of Columbus

PROJECT MANAGEMENT TEAM

ENGAGEMENT TEAM

Shelly Corbin The Sierra Club

Abby Kamagate Photographer

DOCUMENTATION TEAM

DESIGN TEAM

Theo Edaakie

Indigenous Design Studio + Architecture

Tamarah Begay

Indigenous Design Studio + Architecture

DESIGN TEAM

CULTURAL COMPETENCY COMMITTEE

Dr. Melissa Crum Mosaic Education Network

Nancy Recchie Columbus Historian, Italian American

CULTURAL COMPETENCY COMMITTEE

CULTURAL COMPETENCY COMMITTEE

Dr. Jason Reece Vice Provost of Urban Engagement, OSU

Dr. J Love Benton City of Columbus

CULTURAL COMPETENCY COMMITTEE

Amanda Golden Designing Local

Josh Lapp Designing Local COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Jennifer Fening City of Columbus

Matt Leasure Designing Local Landscape Architecture

Emily Moore DLR Group

Kimberly Danielle KiMISTRY

Kerry Kennedy Cultural Memory

Christina Kruise DLR Group

Dan Williamson Werth PR

Acted as an internal sounding board and review committee for all content generated for this project

• Dr. Cristina Benedetti, PhD, Folk and Traditional Arts Contractor — Ohio Arts Council

• Dr. J. Love Benton, PhD, Equity Manager — City of Columbus

• Dr. Melissa Crum, PhD, DEI Consultant — Mosaic Education Network

• Nancy Recchie, Columbus Historian

• Dr. Jason Reese, PhD, Associate Professor of City & Regional Planning — Knowlton School, The Ohio State University

Developed and facilitated engagement experiences for the general public

• Shelly Marie Corbin (Takóni Kókipešni), Itázipčo/Mnicoujou — Lakota tribe member

• Kimberly Danielle, Community Engagement Coordinator — KiMISTRY

• Kerry Kennedy, Executive Director — Cultural Memory

• Joshua Lapp, AICP, Co-Founder & Principal — Designing Local

• Brian Liles, Engagement Coordinator & Videographer — Designing Local

• Madeleine Philipp, Engagement Coordinator — Designing Local

• Dan Williamson, Senior Vice President — Werth PR

Used engagement content to generate designs for a potential new statue site

• Tamarah Begay, AIA, NCARB, AICAE, CDT, LEED AP BD+C, Principal-in-Charge — Indigenous Design Studio + Architecture

• Charles Benick, Digital Illustrator — CBenick Digital Illustration

• Matt Leasure, AICP, PLA, LEED AP, Principal — Designing Local

• Christopher Loeser, AIA, Principal, Cultural and Performing Arts — DLR Group

• Jasmine Metcalf, Urban Planner — Designing Local

• Emily Moore, Lead Designer, Cultural and Performing Arts — DLR Group

• Jaime Schmotzer, Urban Designer — Designing Local

• Anna Talarico, Public Art Coordinator — Designing Local

Ensured the team was on task to achieve grant goals

• Erin Blue, Special Cultural Projects Coordinator — City of Columbus

• Jennifer Fening, Deputy Chief of Staff — Mayor’s Office, City of Columbus

• Amanda Golden, Co-Founder & Managing Principal — Designing Local

Documented the engagement process and learning exchanges

• Megan Adornetto, Historian — Designing Local

• Aaron Blevins, Videographer

• Lesli Current, Graphic Designer — Designing Local

• Abby Kamagate, Photographer & Artist

• Meredith Reed, Writer — Designing Local

Community leaders also volunteered to provide guidance and offer feedback on each stage of the project

• Darsy Amaya — Nationwide Children’s Hospital

• Landa Masdea Brunetto — Columbus Piave Club

• Fran Frasier — Black Girl Rising

• Jami Goldstein — Greater Columbus Arts Council

• Hannah Mason-Macklin — Columbus Museum of Art

• Kimber Perfect — Mayor’s Office (retired)

• James Sisto — Columbus Italian Club

• Jayme Staley — Greater Columbus Sister Cities International

• Doreen Uhas Sauer — Columbus Historian

• Ellie Wallace — PNC Bank

As written by Amanda Golden of Designing Local to orient team members to the project.

We challenge surface-level narratives and traditional memorial forms. For too long, statues have commemorated individuals’ stories through a narrow, exclusionary lens. As the City of Columbus grapples with deep-rooted inequalities — including systemic injustice, racism, colonization, and beyond — our city is well-positioned to understand and untangle these legacies. The city is addressing the legacy of the Christopher Columbus monument, which to some is a symbol of historical injustice.

We seek truth and eventual reconciliation, not erasure. The outcomes of Reimagining Columbus transcend the outcome for the Christopher Columbus monument and the site where it once stood. Our public spaces and storytelling must actively represent willfully overlooked histories. In-person and digital public initiatives will create spaces for inclusive knowledge-sharing and understanding on the path to reconciliation.

We honor multiple perspectives and lived experiences. Gathering information about why the monument was erected can inform — but not fully shape — the monument’s historical context. While expertise, documentation, and historic findings may represent one part of the monument’s story, these details do not overshadow our commitment to present-day ideals of equity and justice.

We celebrate our city’s diversity, and we recognize that public spaces have not always supported this idea. Upon its founding, Columbus did not equally distribute civic power to all people. Over time, diverse populations have enriched Columbus’ cultural landscape, aligning our present-day civic structures and community ideologies with those that improve quality of life for all. Reimagining Columbus seeks pathways for increased belonging and understanding for everyone who calls Columbus home.

We acknowledge the complexity of Columbus' legacy. Christopher Columbus is a symbol of perpetuated generational trauma for many whose identities and personal histories emerge from the legacies of displacement and erasure, including the transatlantic slave trade and the forced removal of Native Americans. For others, Christopher Columbus is a celebrated figure within the American narrative, and was honored by 19th- and 20thcentury immigrant communities facing discrimination. A collective truth based on shared history emerges from spaces where all stories are heard and honored.

We commit to this process. As we engage in this evolving dialogue about where we are today, we know the path to reconciliation requires patience, respect, and continued learning. We anticipate that feedback may change our assumptions, or shift our approach, but our responsibility to the people in our community remains at the core of this ongoing work.

We accept that healing can be uncomfortable, especially where multiple perspectives exist. This complex statue embodies the contradictions in our national narrative. If we hold space for this complexity, then we can begin to identify our common values and shared truths, which will guide our vision for Columbus’ public art and memorial landscape. By expanding our collection with new works and engaging in public dialogue, we can create a richer and more nuanced understanding of history. Through innovative education and public art rooted in humanity-focused history, we can build a foundation for a future filled with diverse stories and perspectives.

Book 1 of the Reimagining Columbus Final Report tells the story of how a statue that once represented the promise of “universal peace and cooperation” over time came to be associated with the mass atrocities of its subject, and how one American city chose to reckon with that development. During the Black Lives Matter protests of June 2020, the City of Columbus, Ohio removed its Christopher Columbus statue — a gift from the City of Genoa, Italy in 1955 — from City Hall, in part to signal partnership with the city’s people of color in addressing police brutality and other issues. But many in Columbus’ ItalianAmerican community, for whom the statue continued to represent family, Italian heritage, and immigrants’ many contributions to the city, found the statue’s removal wrenching.

A thoughtful community conversation to sort through these strong feelings and conflicting perspectives would be required to determine the statue’s future disposition. Reimagining Columbus was that community conversation. With $2 million from the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project, the city was able to engage residents in a process to reimagine how its Columbus statue might be displayed and what it might communicate to viewers. The following books in this series dive more deeply into how this process unfolded and what was learned throughout. Book 2 describes the research activities undertaken to reveal Columbus the man, Columbus the idea, and Columbus the place and its people; it further describes the original content developed and learning exchanges offered throughout the project.

The Gift of a Statue

1. Mellon Foundation, "The Monuments Project FAQs," accessed December 14, 2024, https:// www.mellon.org/article/the-monuments-projectinitiative-faqs

2. "From the Editor: Columbus Conundrum," Columbus Monthly, February 3, 2021, https://www.columbusmonthly.com/story/ lifestyle/2021/02/03/from-editor-columbusconundrum/115434134/

3. “Columbus Mileposts: Oct. 12, 1955," Columbus Dispatch, October 12, 2012, https://www.dispatch. com/story/news/2012/10/12/columbus-milepostsoct-12-1955/23405289007/

4. Motz, Doug. “History Lesson: Happy Columbus Day,” Columbus Underground, October 14, 2013, https://columbusunderground.com/history-lessonhappy-columbus-day-dm1/

5. Fochessati, Matteo. “Edoardo Alfieri: A Complex Artistic Journey to the Columbus Monument” (Wolfsoniana, October 18, 2022).

6. Smithsonian American Art Museum, "Christopher Columbus, (sculpture)," Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture, accessed July 4, 2025, https://siris-artinventories.si.edu/ipac20/ipac jsp?&profile=ariall&source=~!siartinventories&uri= full=3100001~!315037~!0#focus

7. City of Columbus Clerk Office, The City Bulletin (City of Columbus, August 6, 1955), 693–694.

8. “Statue of ‘Chris’ is Unveiled,” Columbus Evening Dispatch, October 13, 1955.

9. Sister Cities International, “About Us,” accessed December 15, 2024, https://sistercities.org/aboutus/

10. Greater Columbus Sister Cities International, "Sister Cities," accessed December 15, 2024, https://columbussistercities.com/sistercities

11. “Did You Know? | Globally, Columbus shares ties with eight 'sister cities'.” Columbus Dispatch, June 9, 2013, https://www.dispatch.com/story/ news/2013/06/09/did-you-know-globallycolumbus/24152369007/

Columbus, Ohio in 2020

12. Moorman, Taijuan, “Coronavirus Update: State of Emergency, OSU Cancellations, Concerns at the Polls,” Columbus Underground, March 10, 2020, https://columbusunderground.com/ coronavirus-update-state-of-emergencydeclaration-osu-closure-tm1/

13. Wikipedia, "COVID-19 pandemic in Columbus, Ohio," accessed December 18, 2024, https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_pandemic_ in_Columbus,_Ohio#cite_note-4-13_ protest-15

14. Starkey, Jessi, “Protesters gather outside of statehouse saying they want to go back to work,” ABC 6 On Your Side, April 9, 2020, https:// abc6onyourside.com/news/local/protestersgather-outside-of-statehouse-saying-they-wantto-go-back-to-work

15. “Protesters back at Ohio Statehouse during coronavirus news conference,” Fox 8 News, April 13, 2020, https://fox8.com/news/coronavirus/ protesters-back-at-ohio-statehouse-duringcoronavirus-news-conference/

16. “Track Covid-19 in Franklin County, Ohio,” The New York Times, March 26, 2024, https://www. nytimes.com/interactive/2023/us/franklin-ohiocovid-cases.html

17. McKoy, Jillian. “New Analysis Reveals Many Excess Deaths Attributed to Natural Causes Are

Actually Uncounted COVID-19 Deaths,” Boston University School of Public Health, February 6, 2024, https://www.bu.edu/sph/news/ articles/2024/new-analysis-reveals-many-excessdeaths-attributed-to-natural-causes-are-actuallyuncounted-covid-19-deaths/

18. Hill, Evan, et al. “How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody,” The New York Times, May 31, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/ george-floyd-investigation.html

19. Columbus reaches $5.75M settlement with people injured during 2020 protests,” ABC 6 On Your Side, December 10, 2021, https:// abc6onyourside.com/news/local/columbus-topay-more-than-5-million-federal-lawsuit-injuredfalsely-arrested-black-lives-matter-protestorssummer-2020-12-9-2021

20. “Here are the names of people killed in police shootings in Columbus,” Columbus Dispatch, April 21, 2021, https://www.dispatch.com/story/ news/local/2021/04/21/makhia-bryant-andrehill-casey-goodson-and-others-killed-columbuspolice-say-their-names/7283680002/

21. Doyle, Céilí. “Franklin County has one of highest rates of fatal police shootings in Ohio and the U.S.,” Columbus Dispatch, February 23, 2021, https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/ local/2021/02/23/franklin-county-has-toprating-fatal-police-shootings-u-s/4507751001/

22. “Under fire: Behind the increase in violence in Columbus,” Columbus Dispatch, October 13, 2020, https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/ crime/2020/10/13/under-fire-series-behindincrease-violence-columbus/3638924001/

23. Behrens, Cole. “Columbus reaches 100 homicides in 2020 at slower rate than record 2021,” Columbus Dispatch, September 22, 2022, https://www.dispatch.com/story/news/ crime/2022/09/22/columbus-reaches-100homicides-in-2020-at-slower-rate-thanrecord-2021/69509958007/

24. Cogan, Marin. “Why the US had a violent crime spike during Covid — and other countries didn’t,” Vox, July 8, 2024, https://www.vox.com/ politics/358831/us-violent-crime-murderpandemic

25. Wolff, Kevin T., et al. “Violence in the Big Apple throughout the COVID-19 pandemic: A boroughspecific analysis,” Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 81 (July–August 2022), https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S0047235222000496

26. “Art Unites Columbus,” accessed July 7, 2025, https://www.artunitescbus.com/

27. Pember, Mary Annette. “Those statues didn't topple overnight,” ICT News, June 25, 2020, https://ictnews.org/news/those-statues-didnttopple-overnight/

28. “Two sides to Columbus,” Columbus Dispatch, October 13, 2009, https://www.dispatch. com/story/news/2009/10/13/two-sides-tocolumbus/23656698007/

29. Ibid. (Pember)

30. Designing Local, “Reimagining Columbus: Christopher Columbus - The Statue and Its Presence in Columbus Part 1,” Reimagining Columbus Channel, February 26, 2024, https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=a9TUOtfQdkc&t=4s

31. Designing Local, “Reimagining Columbus: Voices of Change in 2020,” Reimagining Columbus Channel, September 17, 2024, https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=HbW2lqLrpvE&t=7s

32. Ibid. (Designing Local, “Reimagining Columbus: Christopher Columbus - The Statue and Its Presence in Columbus Part 1.”)

33. “Mayor Ginther announces Christopher Columbus statue outside city hall will be removed,” 10TV WBNS, June 18, 2020, https://www.10tv. com/article/news/mayor-ginther-announceschristopher-columbus-statue-outside-city-hallwill-be-removed/530-33d0f90f-344b-4f1881d9-ddc3f8fbe926

34. City of Columbus, "Public art," Ordinance No. 1508-2013, § 1, July 122, 2013, https:// library.municode.com/oh/columbus/codes/ code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT33ZOCO_ CH3323EAFRDI_3323.23PUAR

35. City of Columbus, "Commission duties," Ordinance No. 1087-2011, § 2, September 10, 2011, https://library. municode.com/oh/columbus/codes/code_ of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT31PLHIPRCO_ CH3115COARCO

36. City of Columbus, “Special Meeting: Art Commission,” City of Columbus Channel, June 24, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=sqIgNIYtJUs&t=1s

37 Designing Local, “Reimagining Columbus: Christopher Columbus - The Statue and Its Presence in Columbus Part 2.” Reimagining Columbus Channel, February 26, 2024, https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EPy0rK8wto&t=3s

The Empty Plinth

38. Ibid. (Designing Local, “Reimagining Columbus: Voices of Change in 2020.”)

39. Columbus Italian Club. “Help Save Columbus Day Statue and Park,” accessed January 8, 2025, https://columbusitalianclub.com/christophercolumbus-park/

40. “City Begins Discussing What To Do With Christopher Columbus Statue,” WOSU Public Media, April 8, 2021, https://www.wosu.org/ news/2021-04-08/city-begins-discussing-whatto-do-with-christopher-columbus-statue

41. Columbus Art Commission Christopher Columbus Committee, Motion for Consideration, Regular Commission Meeting, November 10, 2020, https://documentcloud.adobe.com/ gsuiteintegration/index.html?state=%7B%22 ids%22%3A%5B%2213ew9xE-lSkJEJGccU QEfKS7reOVKaVkY%22%5D%2C%22acti on%22%3A%22open%22%2C%22userId%2 2%3A%22117445857273493120964%22%2C%22resourceKeys%22%3A%7B%7D%7D

42. City of Columbus, “Request for Proposals for EXAMINATION OF THE POTENTIAL REINSTALLATION OF THE CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS STATUE,” RFP No. RFQ020695, December 16, 2021, https://documentcloud. adobe.com/gsuiteintegration/index.html?state =%7B%22ids%22%3A%5B%22110SRmdp8pJ ZK0yEorD-oClnbJ04PJXb7%22%5D%2C%2 2action%22%3A%22open%22%2C%22userId %22%3A%22117445857273493120964%22%2C%22resourceKeys%22%3A%7B%7D%7D

43. City of Columbus, “Request for Proposals for EXAMINATION OF THE POTENTIAL REINSTALLATION OF THE CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS STATUE,” RFP No. RFQ021527, April 11, 2022, https://documentcloud.adobe.com/ gsuiteintegration/index

44. Bush, Bill. “Christopher Columbus statue still in hiding as City Council pauses return to public view,” Columbus Dispatch , July 26, 2022, https://www. dispatch.com/story/news/politics/2022/07/26/ christopher-columbus-statue-ohio-city-noreturn-public-view-soon/10131853002/

45.Ibid (Mellon Foundation)

46. City of Columbus, “Columbus announces $3.5 Million Plan to Reimagine Public Art,” news release, accessed January 8, 2024, https://www.columbus. gov/News-articles/COLUMBUS-ANNOUNCES3.5-MILLION-PLAN-TO-REIMAGINEPUBLIC-ART-AND-COMMEMORATIVESPACES

47. Ibid. (City of Columbus)

48. Ibid. (Designing Local, “Reimagining Columbus: Christopher Columbus - The Statue and Its Presence in Columbus Part 1.”)

49. Ibid (Mellon Foundation)

FIGURES

The Gift of a Statue

FIGURE 1.0. Jensen, Derek, May 25, 2006. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columbus-ohio-christopher-columbus-statue-2006.jpg

FIGURE 1.1. Edoardo Alfieri Archives. October 12, 1955. https://archivioalfierimaisano.com/historical-photos/

FIGURE 1.2. Columbus Dispatch, October 5, 1935. https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/ local/2020/06/13/photos-christopher-columbus-statues-in/65896288007/

FIGURE 1.3. Edoardo Alfieri Archives. 1955. https://archivioalfierimaisano.com/historical-photos/

FIGURE 1.4. Columbus Dispatch, October 12, 1955. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/dispatch/id/54109/rec/1

FIGURE 1.5. Front page Columbus Evening Dispatch, October 12, 1955.

FIGURE 1.6. Front page Columbus Evening Dispatch, October 13, 1955.

FIGURE 1.7. Christopher Columbus Memorial Dedication Souvenir Program, page 6, October 12, 1955.

FIGURE 1.9. Golden, Amanda, Designing Local, December 2023.

Columbus, Ohio in 2020

FIGURE 2.0. Becker, Paul, June 3, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columbus_Protests_Day_7_(6th_downtown)_38.jpg

FIGURE 2.1. Becker, Paul, July 9, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columbus_BLM_Protests_(06-11-07-04)_IMG_5562_ (50095565877).jpg

FIGURE 2.2. Becker, Paul, June 2, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Downtown_Columbus_Protests_2_June_41.jpg

FIGURE 2.3. March 29, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columbus,_OH_-_ COVID_02.jpg

FIGURE 2.4. Becker, Paul, May 9, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27Free_Ohio_Now%27_%28Columbus%29_ bIMG_0868_%2849876163551%29.jpg

FIGURE 2.5. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_40.jpg

FIGURE 2.6. Becker, Paul, July 18, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protests_in_Columbus,_2020-07-18_(7336).jpg

FIGURE 2.7. April 18, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COTA_COVID_poster_01.jpg

FIGURE 2.8. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_46.jpg

FIGURE 1.8. Christopher Columbus Memorial Dedication Souvenir Program, page 5, October 12, 1955.

FIGURE 2.9. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_18.jpg

FIGURE 2.10. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_45.jpg

FIGURE 2.11. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_03.jpg

FIGURE 2.12. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_07.jpg

FIGURE 2.13. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:George_ Floyd_protests_in_Columbus_(2020-05-28)#/media/File:George_Floyd_protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_19.jpg

FIGURE 2.14. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_29.jpg

FIGURE 2.15. Becker, Paul, May 29, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Floyd_ protest_2020-05-28_Columbus,_Ohio_25.jpg

FIGURE 2.16. Callwood, Hakim and Kayneisha Holloway, Bryan Moss, and Ariel Peguero. Paint on plywood. Photographer Max Rodriguez, [614 Now], June 2, 2020. https://614now.com/2020/ culture/community/columbus-artists-employed-to-paint-boarded-up-downtown-for-artunitescbus

FIGURE 2.17. Miller, Francesca. Nothing to Fear Here, paint on plywood. June 2020. https://www. artunitescbus.com/artwork/nothing-to-fear/

FIGURE 2.18. Miss Birdy, Laurie Clements, Brenen Spivey, Wil Wong Yee, and others unknown. Paint on plywood. June 2020. https://www.artunitescbus. com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CreditLydiaMiller_Birdy23.jpg

The Statue Removal

FIGURE 3.0. Chenoweth, Doral. Columbus Dispatch, July 1, 2020. https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/2020/07/01/ photos-christopher-columbus-statue-removed-from-city-hall/42158937/

FIGURE 3.1. Squillante, Fred, Columbus Dispatch , October 13, 1992. https://www.dispatch.com/story/ news/history/2024/10/13/this-week-in-historyamerican-indians-protest-celebration-of-columbus-day-in-1992-by-ship-replica/75378928007

FIGURE 3.2. Squillante, Fred, Columbus Dispatch , “Demonstrators curse Columbus as ‘murderer,’” October 13, 1992.

FIGURE 3.3. Becker1999, July 19, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:April_2021-_2_ BLM_Protests_(Columbus,_OH)_aIMG_9376_ (51323732319).jpg

FIGURE 3.4. Chenoweth, Doral. Columbus Dispatch, July 1, 2020. https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/2020/07/01/ photos-christopher-columbus-statue-removed-from-city-hall/42158937/

FIGURE 3.5. Chenoweth, Doral. Columbus Dispatch, July 1, 2020. https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/2020/07/01/ photos-christopher-columbus-statue-removed-from-city-hall/42158937/

FIGURE 3.6. Scan of Mayor Andrew Ginther’s letter to the Columbus Art Commission, June 18, 2020.

FIGURE 3.7. Scan of Columbus Art Commission meeting agenda, June 24, 2020.

FIGURE 4.0. Talarico, Anna, Designing Local, 2025.

FIGURE 4.1. Bickel, Joshua. Columbus Dispatch, July 3, 2018. https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/local/2020/06/13/photos-christopher-columbus-statues-in/65896288007/

FIGURE 5.0. Columbus Dispatch, October 12, 1955. https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary. org/digital/collection/dispatch/id/54135/rec/1

FIGURE 5.1. Kamagate, Abby, Reimagining Columbus photographer, 2025.

FIGURE 5.2. National Parks Service, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/trump-administration-establishes-medgar-and-myrlie-evers-home-national-monument.htm

FIGURE 5.3. Map of Los Angeles, 1871. https:// www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/chinese-massacre-1871

FIGURE 5.4. Lee, Russell, July 1942. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSAOWI Collection, LC-USF34-073771-D. Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II , Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission. http://www.uprootedexhibit.com/2014/09/ photographs-of-twin-falls-farm-labor-camp/

FIGURE 5.5. Halsey, Lauren. the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (I), 2022; photographer Hyla Skopitz, 2022, Hypebeast.com https://hypebeast. com/2023/4/lauren-halsey-metropolitan-museum-of-art-south-central-installation

FIGURE 5.6. NormanB, 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_York_-_National_September_11_Memorial_South_Pool_-_ April_2012_-_9693C.jpg

FIGURE 5.7. Chenoweth, Doral. Columbus Dispatch, July 1, 2020. https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/2020/07/01/ photos-christopher-columbus-statue-removed-from-city-hall/42158937/

FIGURE 5.8. Highsmith, Carol M., Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. October 9, 2016. https://www.loc.gov/resource/highsm.41472/ ?r=0.639,0.362,0.112,0.056,0