BOOK # 4 TOWARDS A

DESIGN CONCEPT

2025

Over the course of six books, this report fully details the activities and outcomes of the Reimagining Columbus project, through which the City of Columbus, Ohio reckoned with its relationship to the explorer Christopher Columbus.

THE SIX BOOKS IN THIS SERIES INCLUDE:

BOOK # 1

provides insights into how the City of Columbus came to display a Christopher Columbus statue on the grounds of its City Hall, why that statue was removed in 2020, and how the Reimagining Columbus project was designed to help the city determine what to do with it going forward.

BOOK # 2

describes research the project team undertook to discover the many stories that have played out among the people of Columbus, Ohio since long before it became a city, the truth of Christopher Columbus and his conduct in the New World, and how an explorer who never reached the United States became a symbol of all its promise.

BOOK # 3

outlines the community engagement methodologies employed throughout this project and chronicles the events and activities offered by the Reimagining Columbus project team, as well as findings from these conversations.

BOOK # 4

connects the project team’s research findings and community engagement results to the design principles that informed concepts for a new space in which residents might one day experience the reinstalled Christopher Columbus statue.

BOOK # 5

applies the design principles developed from research and community conversations, and best practices in placemaking, to articulate how a new statue site should look and feel, how visitors should be able to interact with it, and how it could engender profound experiences that reverberate for generations.

BOOK # 6

offers an Art Plan for City Hall Campus to guide the implementation of future public artworks there.

QR CODE

Original materials developed through this program are available at reimaginingcolumbus.com , or upon request.

Reimagining Columbus is funded by the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project, a multi-year commitment aimed at transforming the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented.

INTRODUCTION

As Reimagining Columbus’ research and community engagement phases came to a close, the project’s design team began working to translate the learnings into a design concept for a possible new Christopher Columbus statue placement. Their task was not tied to a particular site or implementation outcome, but rather to the goal of “reimagining Columbus” — in a historically accurate way, honoring community feedback — within a space capable of containing the explorer’s whole story. The team relied on Indigenous design principles to guide their vision for an immersive experience of nature and community togetherness at which visitors could experience the statue (or not), but also learn, play, restore themselves, and heal. So expansive did this vision become that the city, the Reimagining Columbus project team, and community members were inspired to embrace it as a generational vision for an altogether new type of space in Columbus, Ohio. In this way, the team also “reimagined Columbus” — the city — as an evermore courageous, inclusive place, whose people can reckon with difficult truths for the benefit of future generations.

Book 4 depicts the Reimagining Columbus design team’s process from learnings to early conceptual sketches; Book 5 contains the final renderings submitted to the City of Columbus to conclude this project.

All photos, maps, drawings, and renderings in this book were generated by Designing Local from 2024–2025 unless otherwise sourced.

BOOK 4 MAIN IDEAS

• The team worked to incorporate findings from Reimagining Columbus’ research and community engagement activities — outlined in Books 2 and 3 — into designs for a nature-oriented space at which visitors would feel safe to explore a difficult subject.

• Inspiration from Indigenous design principles provided the means to imagine a new placement for the statue that could promote community reconciliation through touchpoints with nature.

• The city’s Christopher Columbus statue is featured in the designs, recontextualized with a timeline truthfully depicting his activities in the Caribbean and by positioning him at a lower, more human scale; visitors would have the option to experience the statue or not.

• The concept for a new place to install the statue includes spaces for community gathering and events, learning, public art, nature play, and reflection.

• This treatment for the Columbus statue would be entirely unique within the United States; most places do not recontextualize their contested statues in a new space, but rather keep them in place, move them to storage indefinitely, sell them, or replace them with different art.

• The concepts herein do not reflect an actual site or approved designs, and no commitment to implementing a site similar to this has been made at this time.

FROM LEARNINGS TO DESIGN

Key insights from research and community engagement sessions directly informed the vision for a place at which the Columbus statue could be reinstalled and recontextualized. This section describes how the project team transitioned from its learning phase to a design phase that honored everything learned.

A RESPONSIVE VISION

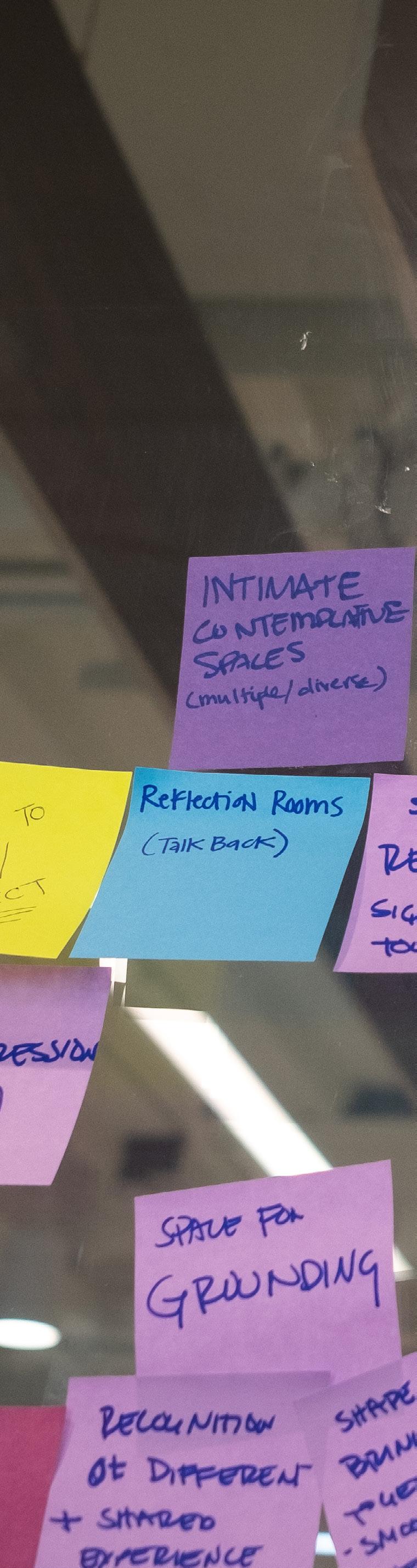

As detailed in Book 3, several themes emerged from the Reimagining Columbus community conversations across all affinity groups. The design team aimed to be especially responsive to community members’ appetite to be surrounded by nature, desire to feel welcome and accepted in public space, need to feel safe and protected in a place that explores difficult subjects, and insistence on truth-telling. Though it was challenging to pull these needs into a coherent physical form, the team effectively did so by incorporating opportunities for reflection and connection, community gathering, and unscripted interactions with nature into their final design concept.

DESIGNING FOR PERCEPTION

A key reminder from community engagement was that people using the same words often mean different things by them. For example, everyone who participated in the engagement conversations indicated their need to feel safe when exploring difficult topics, like Christopher Columbus, in a public space. But the ways they perceive safety were highly variable. People can feel safe in spaces with obvious surveillance or none, enclosures or openness, nature or manmade structures, privacy or people nearby. Accommodating these conflicting needs within the context of a site design is always a challenge, but critically important when the needs arise from the traumas people have suffered in public spaces as a result of their race, gender, physical disability, or other inherent characteristic. A lack of intention when designing for the safety of all intended visitors means that some will opt out of participating in its offerings, to the detriment of the entire community.

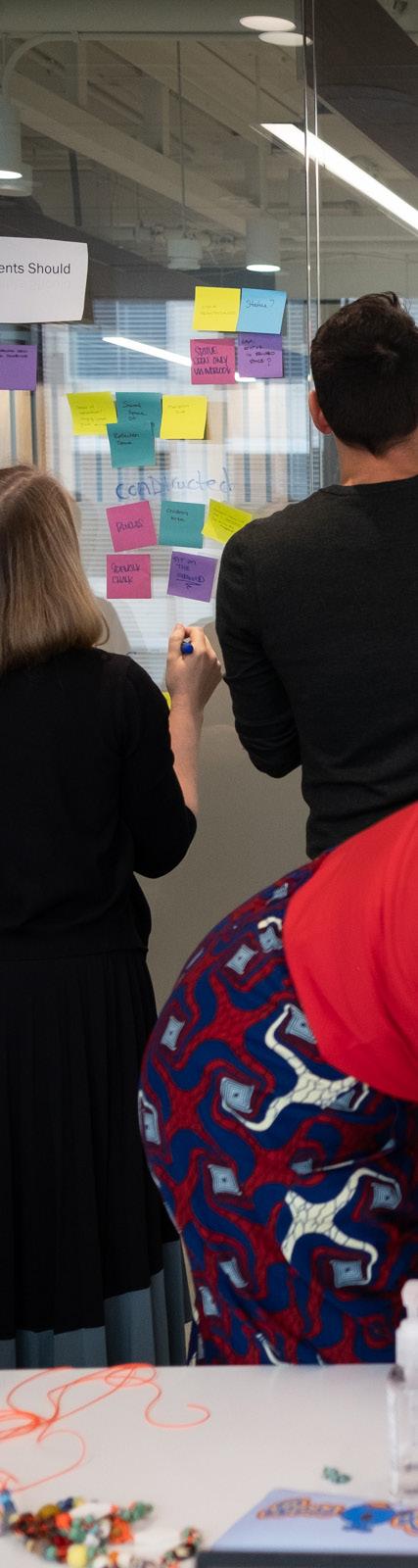

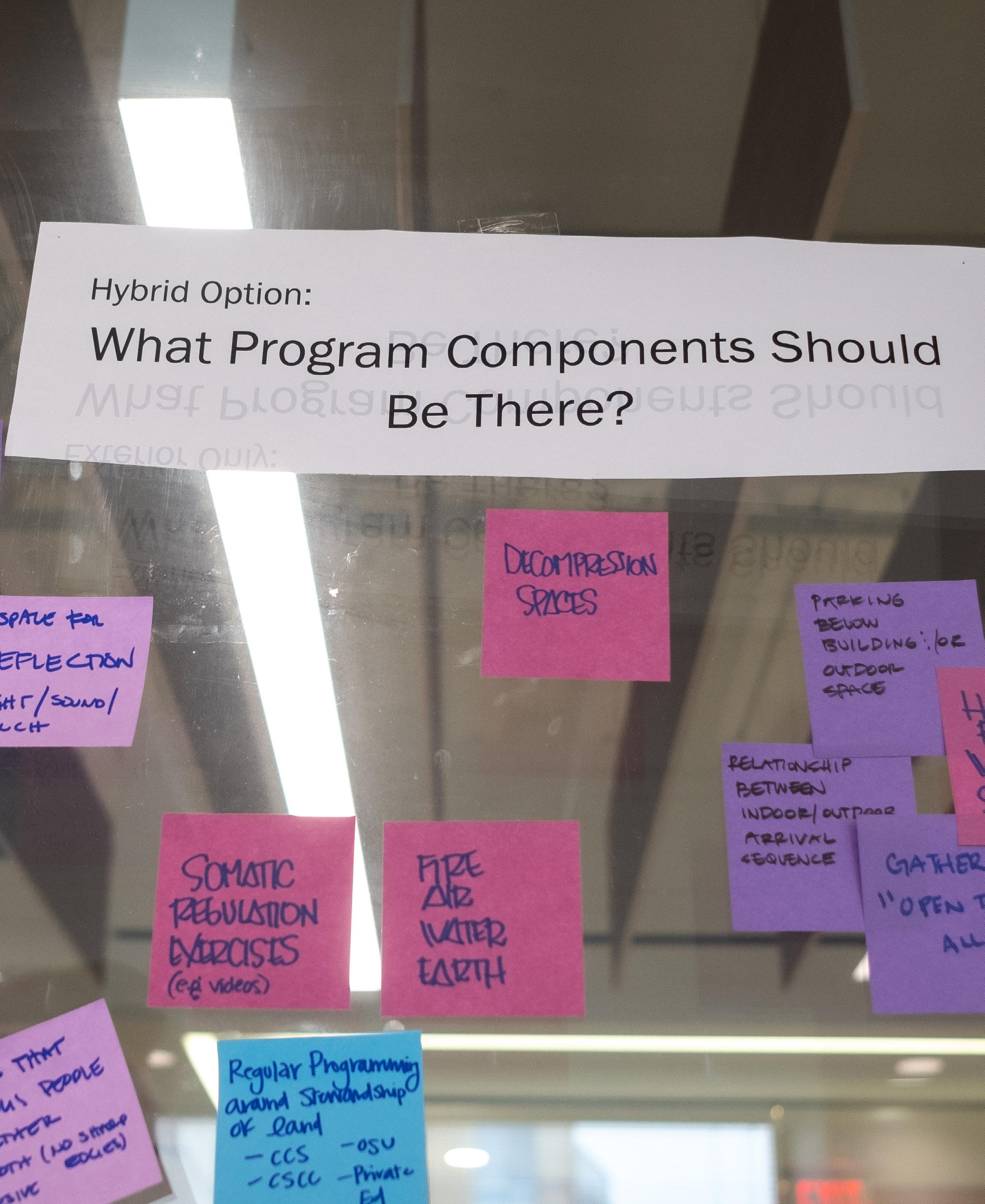

DESIGN KICK-OFF & INSPIRATION

The design team — composed of architects, planners, and landscape architects from Designing Local, DLR Group, and Indigenous Design Studio + Architecture [IDSA], as well as members of the community engagement team — convened for the first time in Washington, D.C. for museum tours and a design charrette to establish a common foundation from which to begin conceptualizing a new placement for the Columbus statue. They first visited the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture to experience how their interpretive spaces addressed difficult histories. Each team member then shared their reflections on how it felt to be in those very different spaces and which elements from them, if any, might be useful to carry into this project. The two-day conversation was the first in a six-month series of weekly sessions to discuss topics such as those on the following pages. A second design charrette was held in Columbus to explore riverfront sites and how they might impact key design choices.

WHAT’S A DESIGN CHARRETTE?

A design charrette is a period of intense work among design team members, sometimes in collaboration with community members, to quickly generate potential solutions for a particular project. The process typically involves sketching, mapping, and dialogue with many people over hours or multiple days, and culminates in a collective project vision to guide the following design phases.

A PROPOSED DESIGN PROGRAM

The project team imagined a future space for the Columbus statue that would be unique to the city and worthy of it. This section recommends the types of activities such a space might offer.

A UNIQUE EXPERIENCE

The design program for this project was a matter of some debate among the design team, with some arguing that the space should be akin to a museum and others arguing for a grander scope. Ultimately, Designing Local led the team to imagine an experience of exterior and interior spaces that would be unparalleled in Columbus, or, indeed, anywhere in the country — a site so spectacular that the statue itself would recede into the background of the city’s evolving story.

LOCATING A SITE

Though a new site for the statue was not identified through the Reimagining Columbus process, community feedback and the proposed design program suggests a site with the following features:

• A flowing natural waterway

• Immersion in nature

• An urban respite

• An experience unmatched in Central Ohio

• Multimodal accessibility

• A central location

• A relationship to other cultural facilities

• Sufficient space to host a variety of activities and experiences

WHAT’S A DESIGN PROGRAM?

A design program is a listing of the physical structures and amenities a site design should include, based on an understanding of the types of activities it will ideally accommodate.

exterior spaces

• A cultural garden that includes the Christopher Columbus statue and numerous interpretive elements

• A large community gathering space that supports events and festivals

• A natural play area with river access

• Publicly accessible spaces for permanent and temporary public art

• Overlooks and viewing areas that showcase the city’s uniqueness

• Infrastructure for temporary food vendors

• Restrooms and other public amenities

• Multiple places for reflection and respite in a natural environment

• Connections to the city’s greenways and blueways

interior spaces

• Additional interpretive features

• Gallery space for both permanent and temporary exhibitions

• Classrooms and small meeting spaces

• A theater to host community performances

• A lobby with reception space for visitors

• Infrastructure to support artist-inresidence programming

• A community library

INDIGENOUS DESIGN PRINCIPLES

To counterbalance Indigenous peoples' erasure in the Christopher Columbus story, the design team chose to center their experience when conceptualizing a new space for the statue. This section provides a brief overview of Indigenous design principles and reveals how a Navajo team member’s poem engendered design values evoking balance, harmony, and healing.

INDIGENOUS DESIGN

The Reimagining Columbus design team agreed that Indigenous design principles would guide their site concept. Indigenous design principles are not universal — different tribes have different traditions around how they build and what activities should be accommodated at a site. For example, most tribes regard water as sacred, but they may disagree as to whether water-oriented activities, such as swimming, are acceptable. As discussed in the What Is Indigenous Design? presentation (available on the Reimagining Columbus website), Indigenous design largely centers on working in cooperation with nature to create structures that connect with and do no harm to Mother Earth and Father Sky. This may involve developing forms that harness the power of the wind and sun to heat and cool a structure; sourcing local, sustainably harvested materials; considering a structure's impact on two- and four-legged beings; and balancing a space according to the cardinal directions, among other considerations. Indigenous design further incorporates the stories of a community’s culture that date back generations and will reverberate into future ones.

The Cardinal Directions

The design for a future statue placement was oriented around the cardinal directions of a medicine wheel. These circular Indigenous structures — which are divided into four quadrants that represent the life cycle from birth to death and renewal; human developmental stages from child to elder; the seasons and natural elements; the four directions; the body–mind–heart–spirit quaternity; and more — have been used by many tribes over the centuries to articulate the interconnectedness of all things. Design team members were mindful to situate site elements according to the symbolic attributes attributed to each of the cardinal directions.

WHAT ARE DESIGN PRINCIPLES?

Design principles are a set of guidelines that inform the choices to be made throughout a design process.

Spring Solstice

March

Planting

Winter Solstice

December

Summer Solstice

June

Harvesting

Disclaimer

Without the written permission of Indigenous Design Studio + Architecture, LLC; it is prohibited to integrate in whole, or in part, any of the published materials into another program or to use them by any other means.

FIGURE 3.0. Medicine wheel design. IDS+A (2025).

This image may not be used for any means without written permission from IDS+A.

THE FIRST ARRIVAL OF HOME

This poem* was contributed by design team member Tamarah Begay, a member of the Navajo nation and one of the few Indigenous architects in the country, as a complete statement of design principles for the space. Given her culture’s reliance on oral communication, she prefers for this poem to be experienced in spoken form.

I Feel the Earth beneath my feet, I feel mother earth.

I could feel her heartbeat.

I feel the breeze, I see the water.

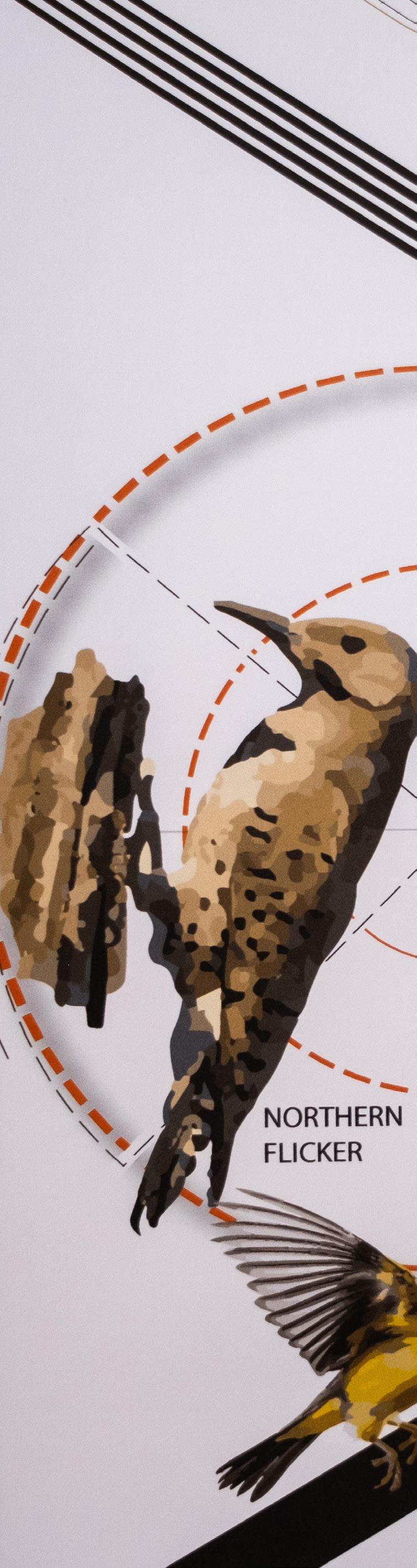

I hear the birds,

I hear the insects, my connection to mother earth, is what I feel. She believes in me, she listens to me, she understands me, her stories are told throughout my body.

My connection is through my people, my connection is to the earth and the sky. I feel her seasons.

I learn from her stories, her stories about how she began. Her stories are about who they are.

My existence, to this earth is through myself, my community, my family I look to the east in the morning, I watch the sunset in the evenings I think about the three generations before me and the three generations after me. I learn through my stories.

Everything around me has a purpose and an existence.

The cardinal directions, the transparency and reflection of who I am, The memories and the emotions

She dances, she performs, she laughs, she cries, she sings, she dances. It’s with her, I view the world in peace, in harmony.

She endures the struggles, she tells the truth, she’s prideful

She has balance, she has harmony.

She has a feeling of form and forms her movement, she’s free, she’s home, This is her home, her children will learn from her stories, the elder will pass on the stories from generation to generation.

This is home, a place of story.

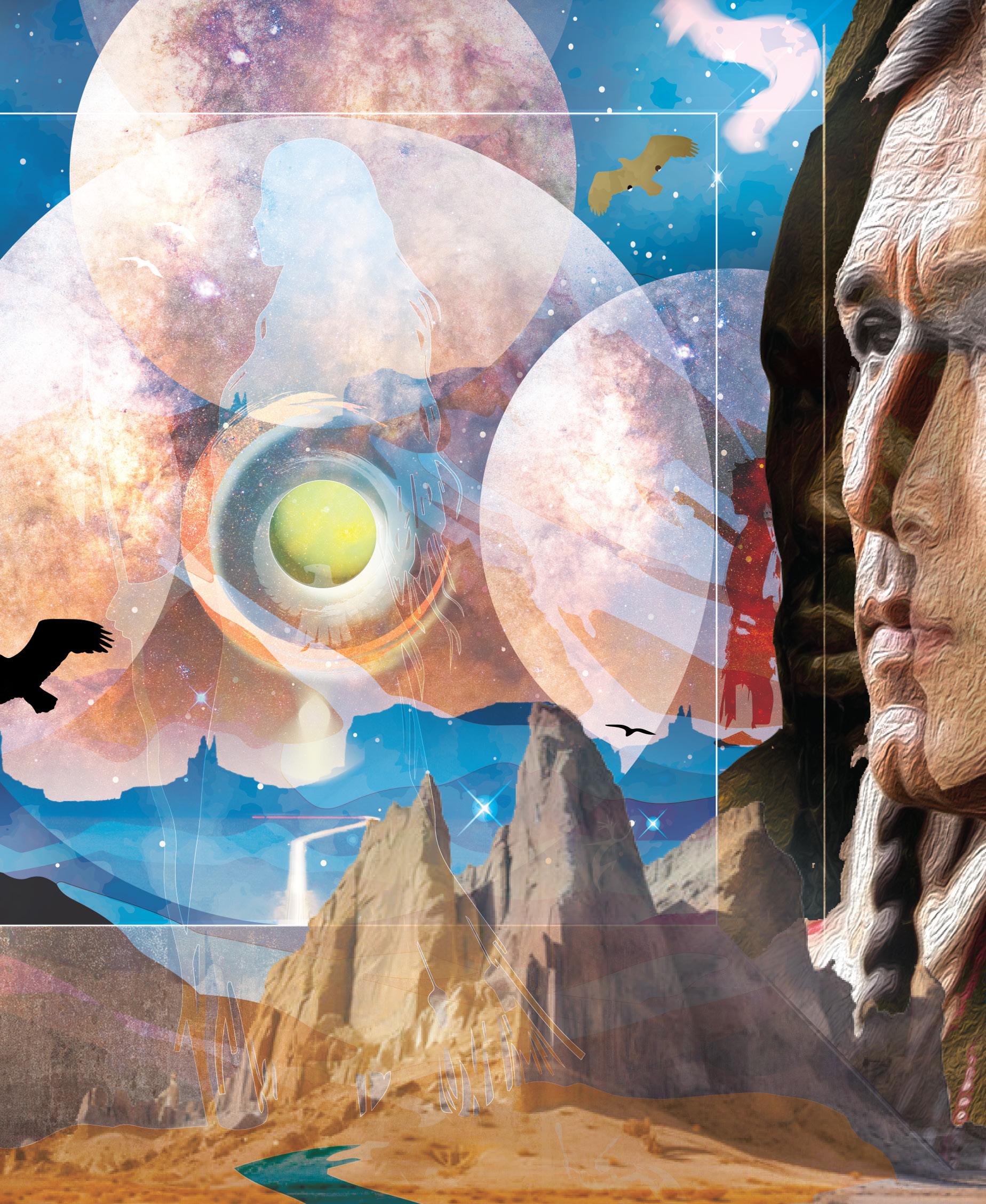

FIGURE 3.1. Design inspiration by IDS+A (2025).

DESIGN VALUES

The poem elicited various reactions among design team members, and robust conversation on culture and tradition that mirrored those among community members during the engagement process. Some felt comfortable with the poem standing alone, without further explanation, as a set of design principles, while others felt it would be better received if accompanied by more conventional design language. They discussed potential compromises that would be both broadly acceptable and culturally responsive, and ultimately extracted the following “design values” from the poem to guide their work.

To honor Indigenous peoples and ways of life, the experience of this new community space should:

1. Center humans’ relationship with Mother Earth and allow people to connect with her in myriad forms

2. Orient people along a continuum of time from generations long past to those in distant future

3. Move, reflect, harmonize, and balance along four axes (associated with time, cardinal directions, elements, and the seasons)

4. Tell true stories and honor the common threads of struggle, resilience, and transformation that have occurred among all peoples

5. Evoke feelings of being in an ancestral home

FIGURE 3.2. Design inspiration by IDS+A (2025).

SKETCHING THE VISION

Once a foundation for the design of a new statue placement had been laid, the team undertook additional exploration to develop specific site elements. This section outlines these efforts and reveals the early stages of putting concepts onto paper.

AN ATYPICAL PROJECT

The project to consider reinstalling the Columbus statue in a new space, particularly one as substantial as that being envisioned here, is unique within the United States. As described in the report Toppling Columbus: The Fate of Christopher Columbus Statues in 13 U.S. Cities Since 2020 , many U.S. cities assessed their Columbus statues during the summer of 2020, and the final dispositions for each have varied widely. New York City chose not to remove its statue and focus instead on adding new pieces to increase the diversity of representation within its public art collection. Philadelphia also kept its Columbus statue, because a judge determined the decision to remove it had no legal basis. In Boston, Newark, and Providence, statues were donated or sold to new owners, who are displaying them at new sites. Norwich’s Italian-American community kept their monument in its original location, but altered it to remove references to Columbus and be less offensive to Indigenous community members. In Houston, the original artist accepted his statue’s return. Statues in Chicago, St. Paul, Richmond, Baltimore, and San Francisco are currently in storage but may be displayed in the future, if not on municipal grounds then in museums or other private property. The Reimagining Columbus initiative in Columbus, Ohio marks the first attempt by a city to consider a new space, grounded in research and community feedback, specifically to reinstall a statue that has been recontextualized to tell a more accurate story of its subject. Adapting to the moment, listening to residents, and transforming the statue into a means for community healing positions the City of Columbus to be a leader in this space and inspire change of this kind across the country.

Clockwise from top left: FIGURE 4.0. New York City. Photo by TarHeel4793 (2015). FIGURE 4.1. Chicago. Photo by James Conkis (2020). FIGURE 4.2. St. Paul. Photo by Ben Hovland (2020). FIGURE 4.3. Norwich, Connecticut. Photo by John Shishmanian (2021). FIGURE 4.4. Houston, Texas. Photo by Elizabeth Conley (2020). FIGURE 4.5. Baltimore. CBS 13WJZ (2020). FIGURE 4.6. Philadelphia. Photo by N Giovannucci (2020). FIGURE 4.7. Newark, New Jersey. Photo by Rebecca Panico (2024).

DESIGN PARAMETERS

As with any project, the design team for Reimagining Columbus was working within a series of parameters that limited what was possible for them to propose. These included:

• The statue would not return to City Hall.

• The statue would remain the property of the City of Columbus.

• The statue would not be destroyed or altered in any way.

• The statue would likely need to remain outdoors (due to its size); the options for securely installing it were unclear.

• No new site for the statue would be provided or identified through this process.

• No budget to implement a final design would be set at this time.

These parameters created unique challenges for the design team. For example, without a site or budget to guide the work, it was difficult to know whether implementing their vision would be realistic. Rather than preemptively shrinking the vision, however, the team opted to create an all-out design that represented the very best of what an inclusive cultural space for the community could be.

KEY CONVERSATIONS & DETERMINATIONS

The design team faced a number of choices when developing their concept for a new Columbus statue placement, and the diversity of the team ensured robust conversations around each. In addition to the design constraints outlined above, the team was also conscious to balance community members’ competing needs and create a space that would be welcoming for all. Several of the conversations, summarized on the following pages, highlight the challenges of this undertaking and illustrate how the team addressed them.

Clarifying the Statue’s Disposition

DESIGN CHALLENGE

A key consideration for the design team was how to position the statue, as this would cue visitors as to how Columbus’ story would be told. Several options were possible. The statue could be positioned on a plinth, towering above viewers in a place of prominence. It could be positioned laying down — either face-up, as if at rest, or face-down, in disgrace. It could be upright, but at a lower elevation relative to viewers. It could be in plain view or hidden, a mandatory experience or an optional one. It could be enclosed within a structure of some kind, placed out in the open, or situated within nature. The statue’s orientation would ideally honor the need of some community members to respect the statue and the need of others to diminish it.

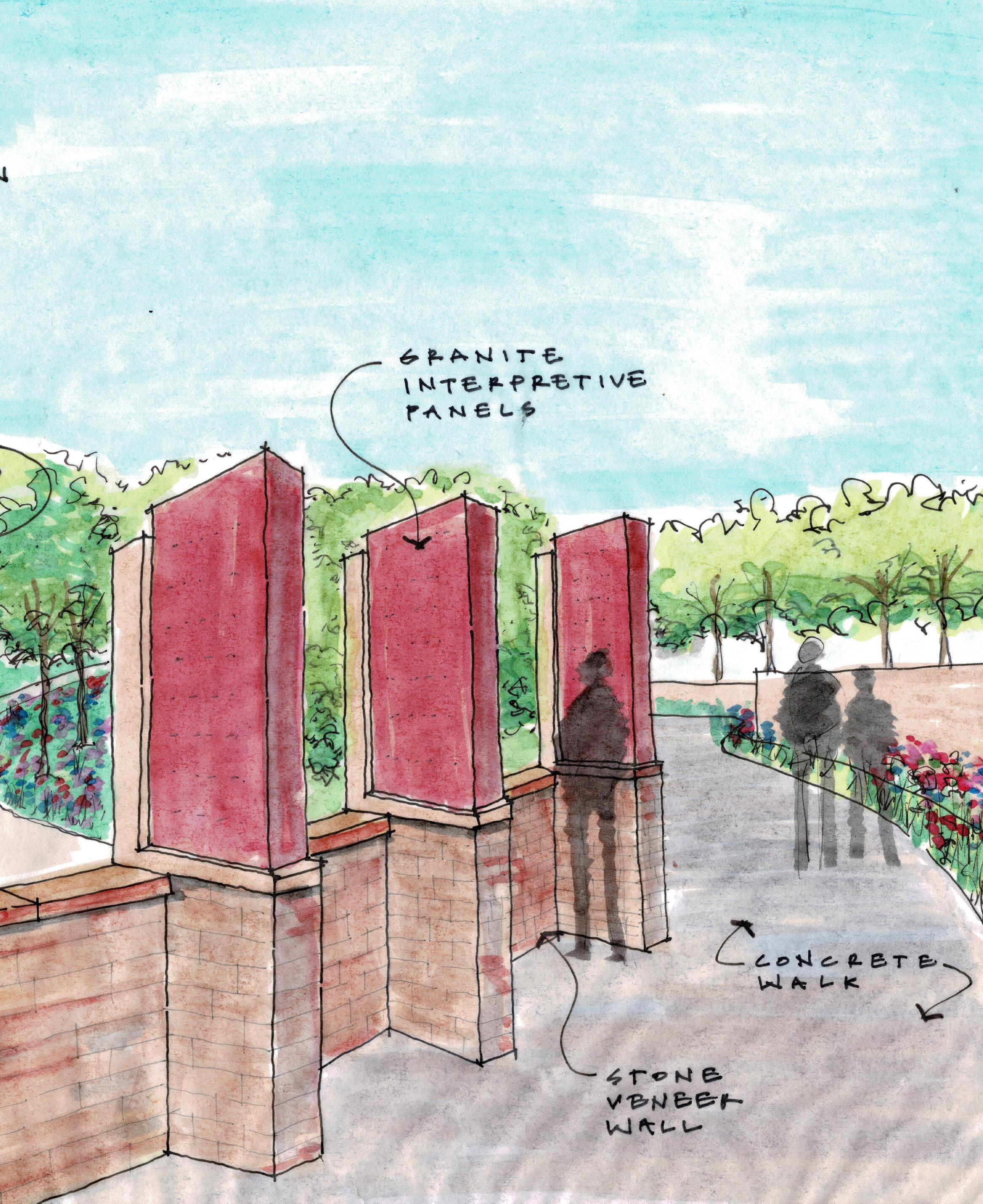

DESIGN TEAM RESPONSE

Ultimately, the team provided a way for visitors to view Columbus from above or eye-to-eye — in a position of power over him — and toe-to-toe, without a plinth to elevate him or his status. The statue is upright and respectfully displayed, but its subject is grounded and not exalted in any way. Interpretive panels lay out the full story of his voyages and his conduct in the Caribbean. In these ways, truth and a more modern orientation towards Christopher Columbus is balanced with respect for the statue and those who continue to care about it.

Cultivating a Broad Experience of the Space

DESIGN CHALLENGE

The design team was mindful that many community members would see no need to invest in a new space for the Columbus statue, and may even be offended by the possibility. A new space would ideally offer many activities and de-center the statue as its primary draw.

DESIGN TEAM RESPONSE

The team debated the proper scope of a new space and what it would offer (i.e., its design program), ultimately settling on an expansive, park-like setting that was less about the statue and more about the experience of the place — about connecting visitors with nature and one another.

Highlighting the Statue’s History & Artistry

DESIGN CHALLENGE

The statue is a thoughtfully designed bronze sculpture by renowned Italian sculptor Eduardo Alfieri gifted to Columbus by Genoa, Italy in 1955 in celebration of the cities’ burgeoning Sister Cities relationship. Though it is controversial today, the statue remains important to some community members and has artistic and historic merit that city leaders and the design team felt the public should be invited to experience. A new space for the statue would ideally make it accessible, but also protect it from harm.

DESIGN TEAM RESPONSE

The team further weighed the statue’s placement and opted to balance accessibility with protection from weather and vandalism by placing it along a paved walking path bordered by stone walls. This would also protect potential protesters from harm, as the lack of open space surrounding the statue would render it impossible to tear down.

Providing Emotional Safety

DESIGN CHALLENGE

Some community members, experiencing the statue through a lens of generational trauma, initially reported they would avoid any space at which it was reinstalled. The design team would need to embed mechanisms of emotional safety into a new statue space for it to attract visitors reluctant to encounter the explorer at all.

DESIGN TEAM RESPONSE

In addition to positioning the statue such that viewers could choose how or even whether to view it, the team provided spaces for people to reflect and process any emotions arising from their encounter with the statue or the accompanying interpretive materials.

THE VISITOR EXPERIENCE

The design team envisioned an experience of seven moments, each with distinct purposes and emotional qualities. They include:

ARRIVAL

HISTORICAL CONTEXT & TIMELINE

THE STATUE

REFLECTION

NATURE PLAY & LEARNING

COMMUNITY GATHERING

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

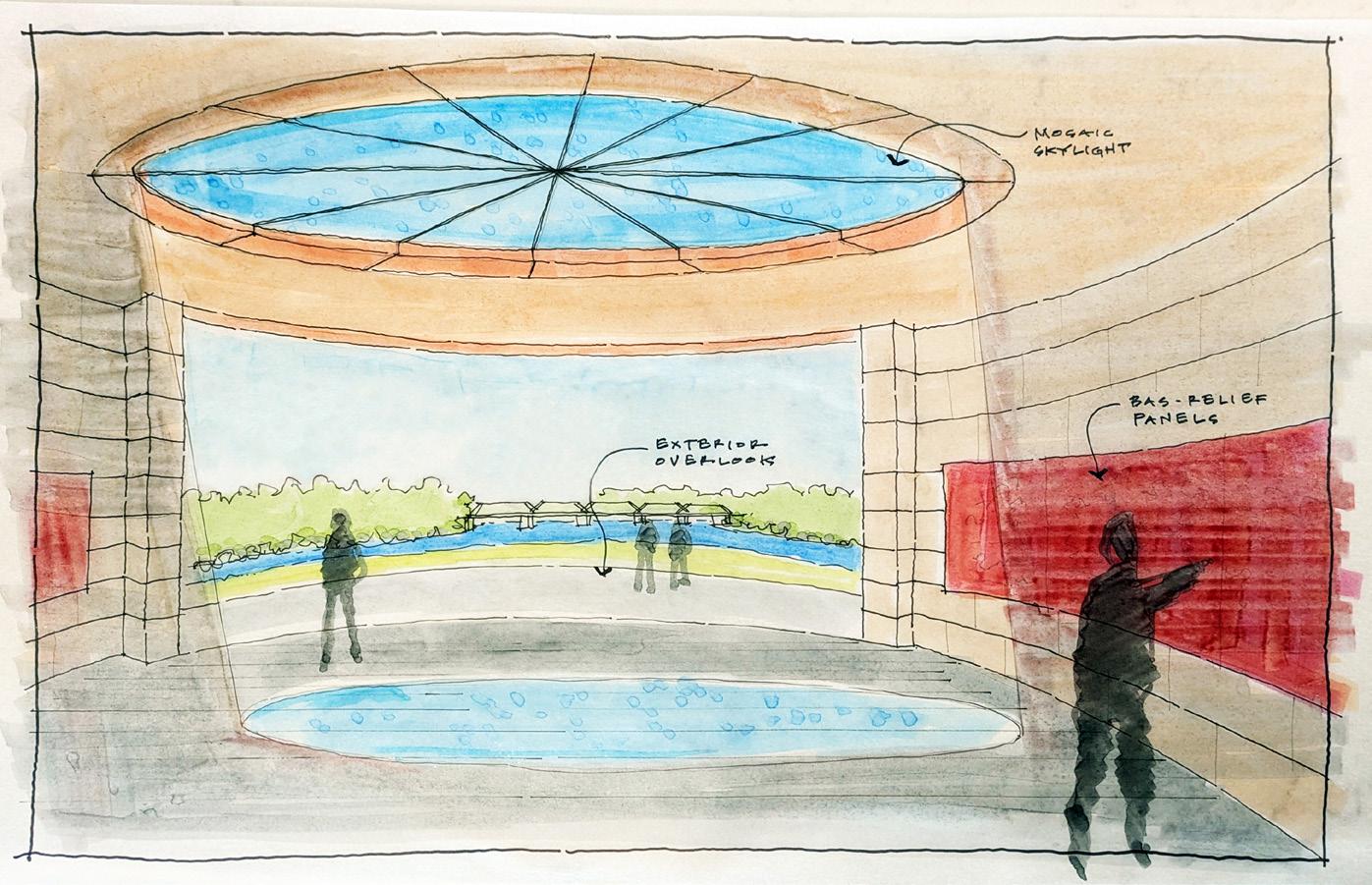

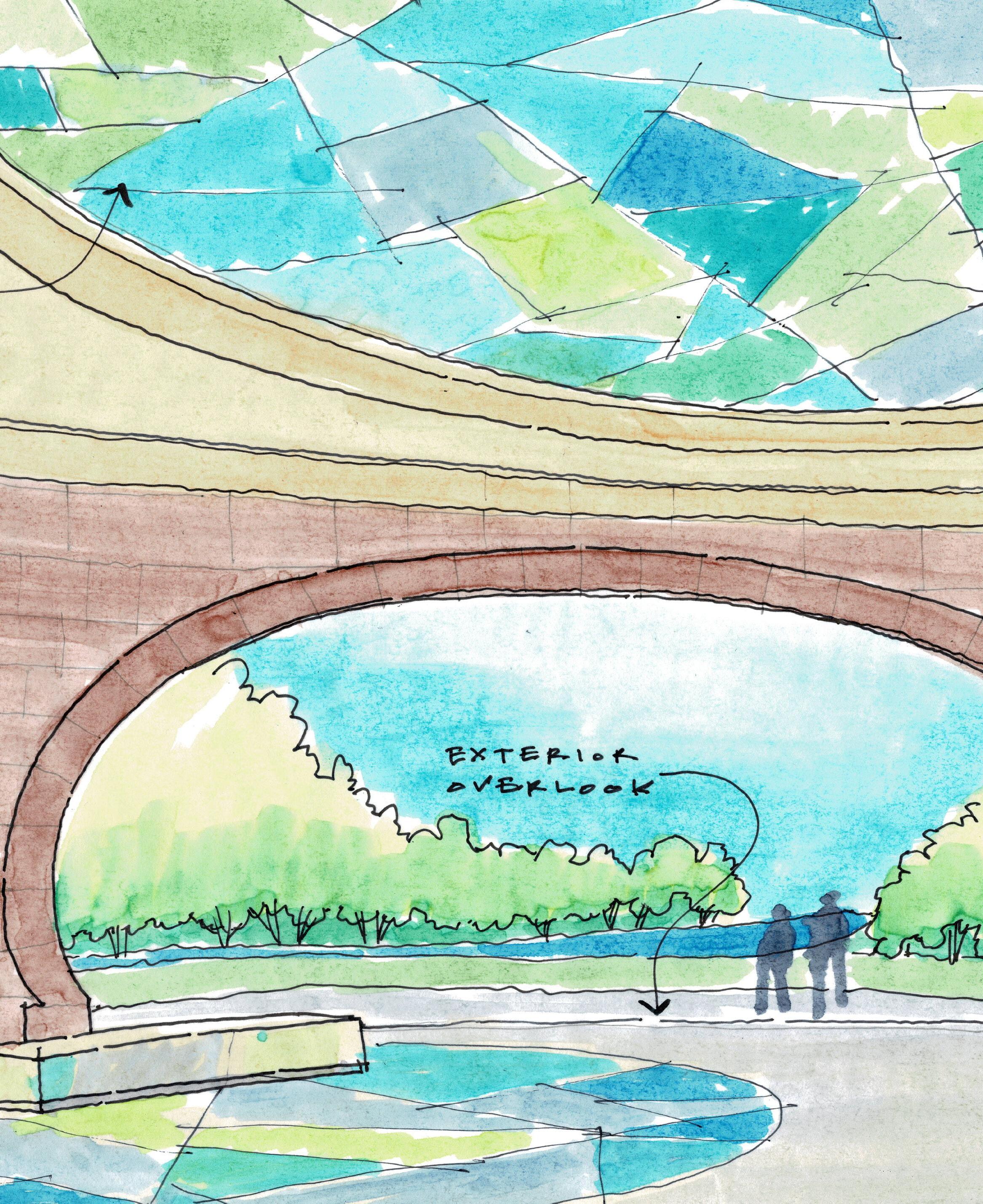

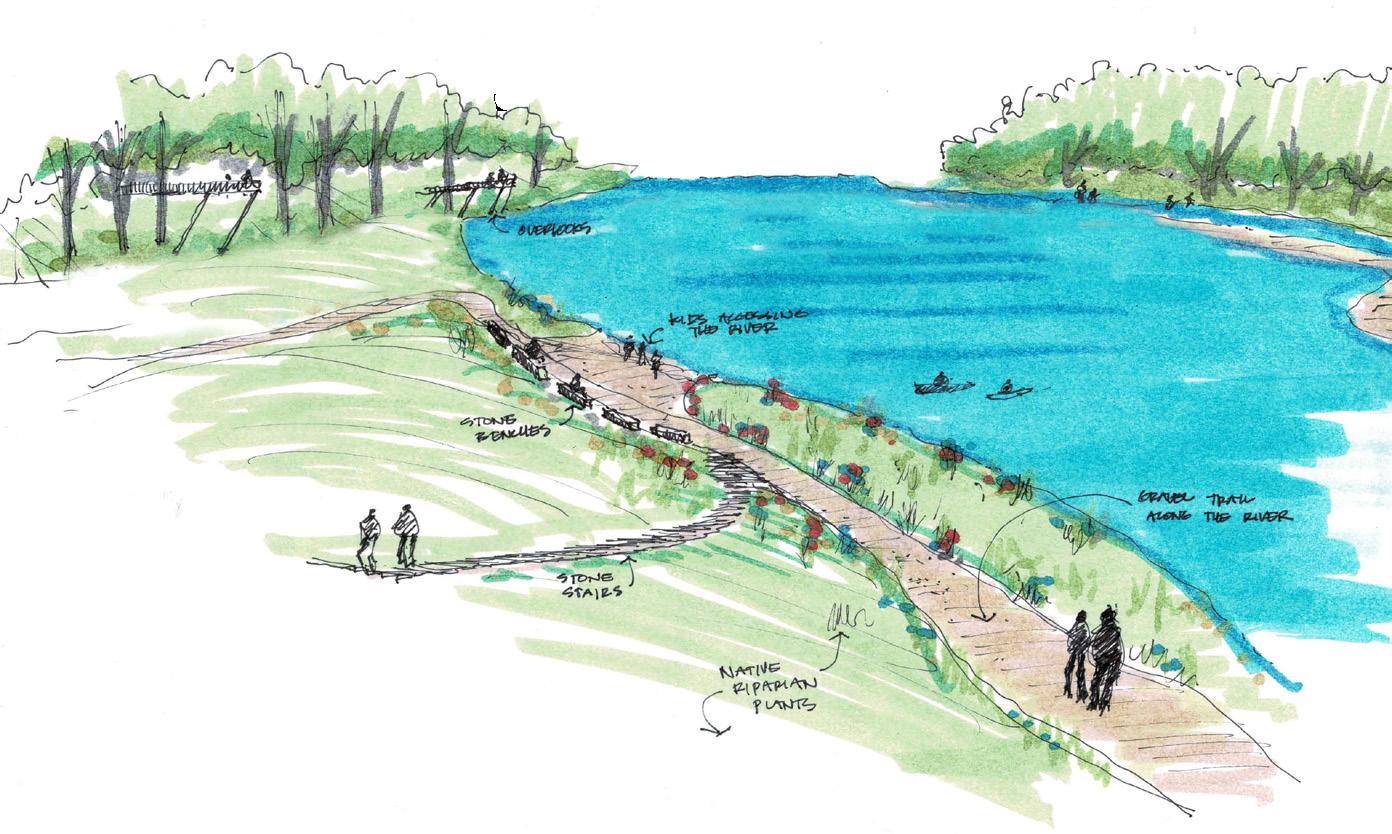

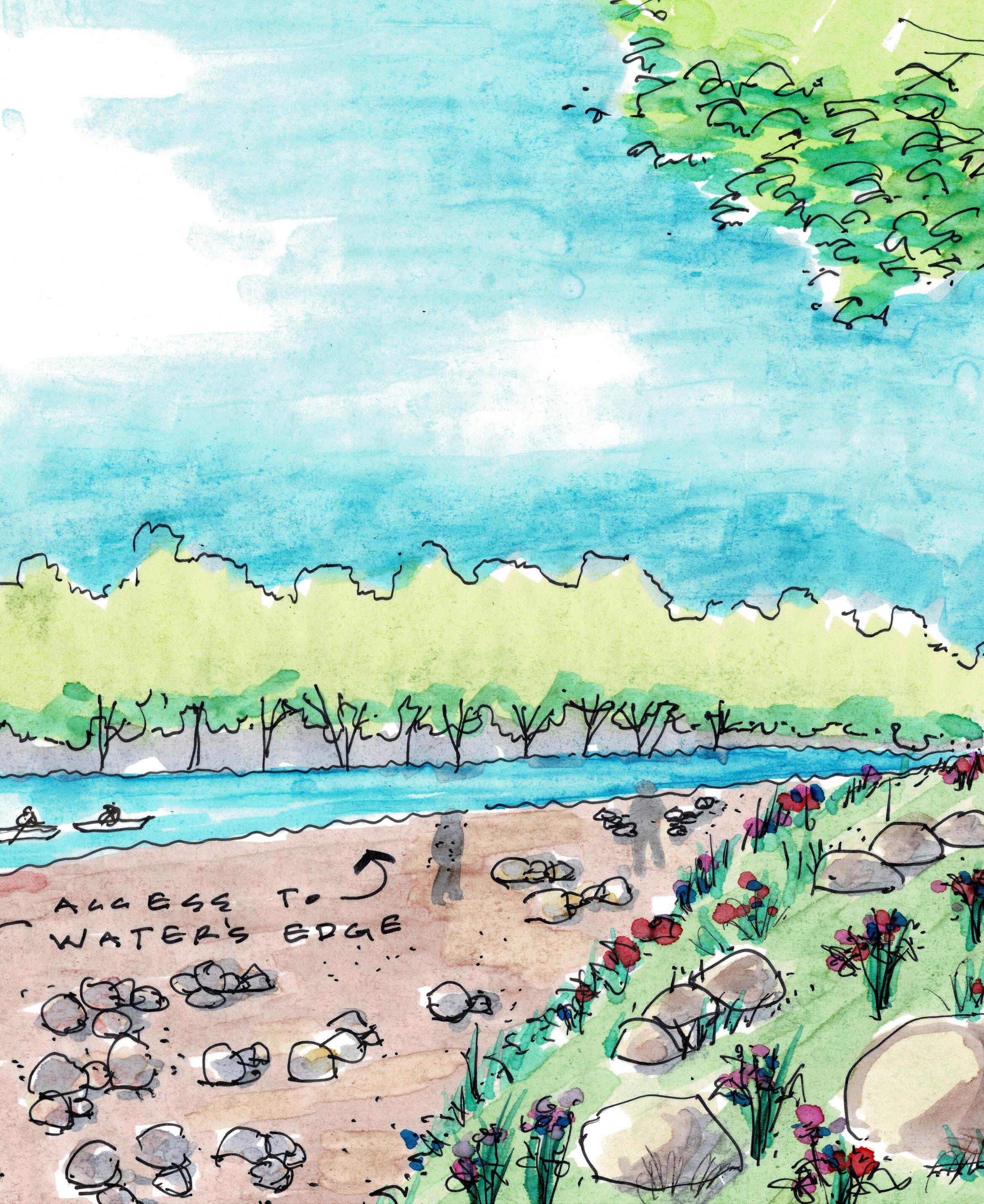

These moments are described on the following pages, with preliminary sketches that demonstrate early thinking about them.

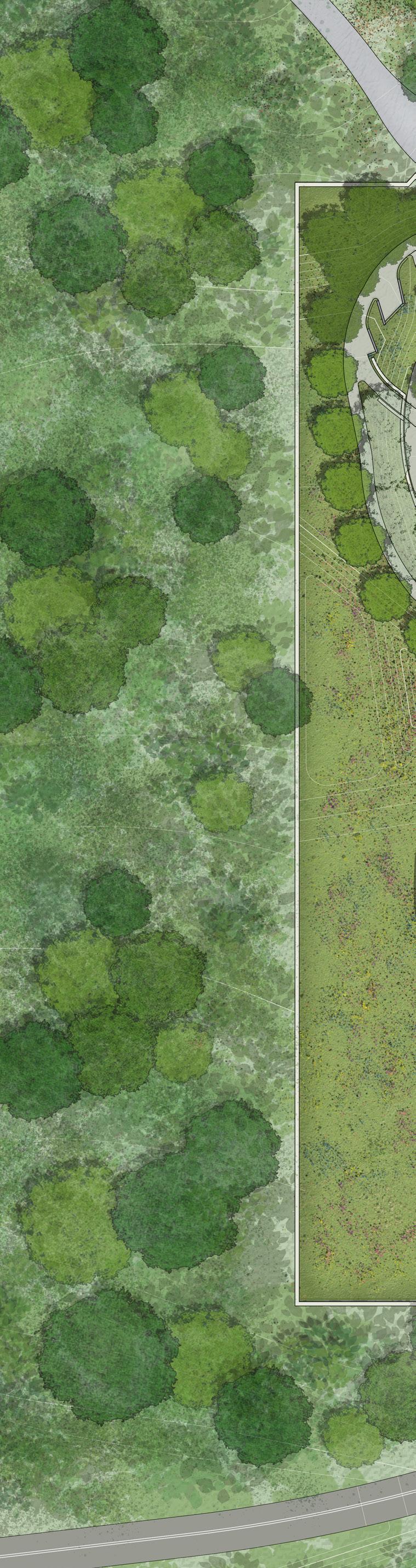

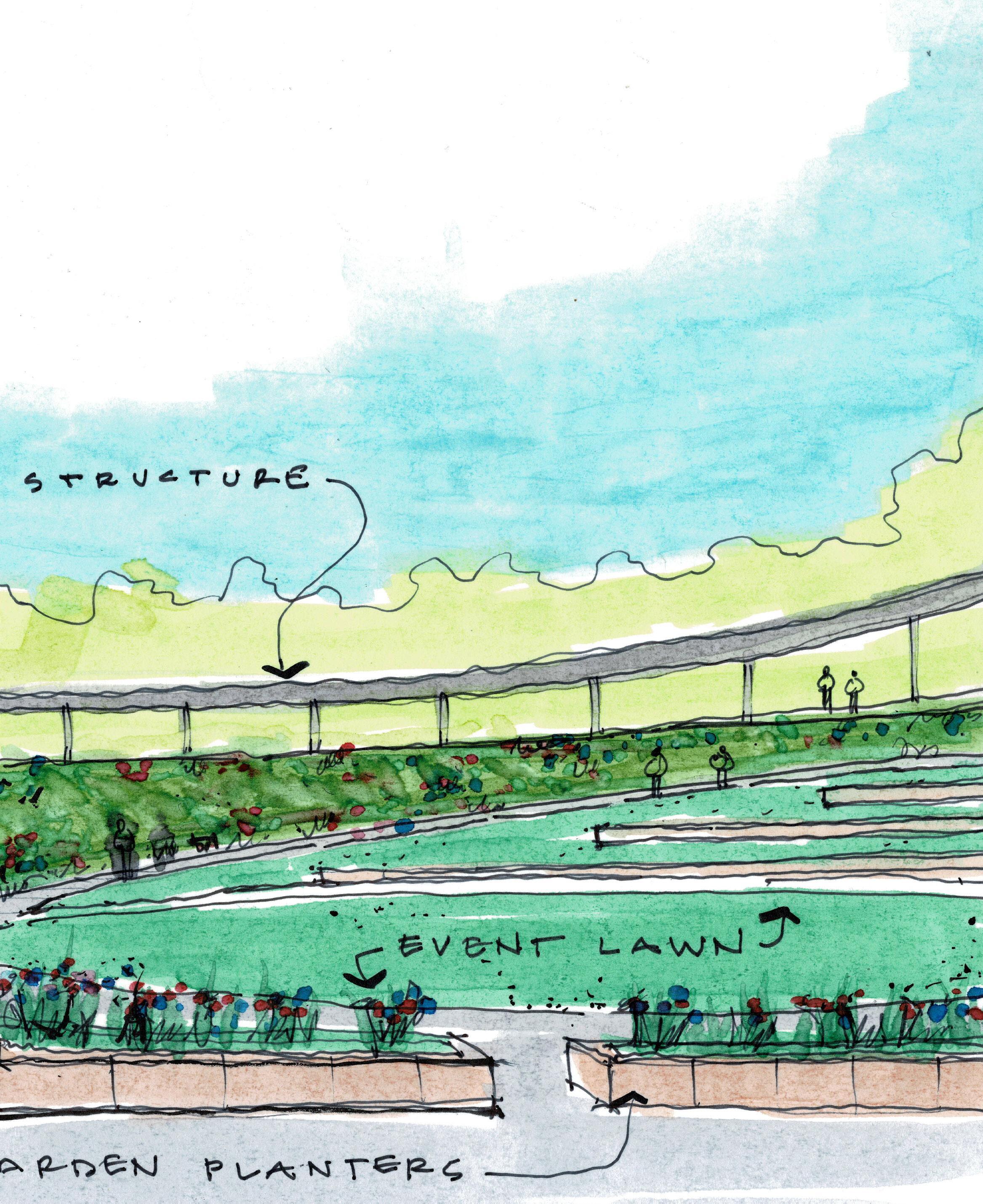

CONCEPTUAL SITE ORGANIZATION

The proposed space was envisioned as a circle or ellipse into which visitors enter from the east and circulate upwards in a clockwise spiral, taking excursions as desired to experience the statue, the river, gardens with native plantings, and other offerings. Key moments radiate out from an outdoor community gathering space to river access in the east and gardens to the north; multi-use public trails connect this place to other Columbus destinations.

LOWER GARDEN (STATUE)

PUBLIC AREA

COMMUNITY GATHERING SPACE

MIDDLE TERRACE

LOWER TERRACE

RIVER ACCESS

THE SEVEN MOMENTS

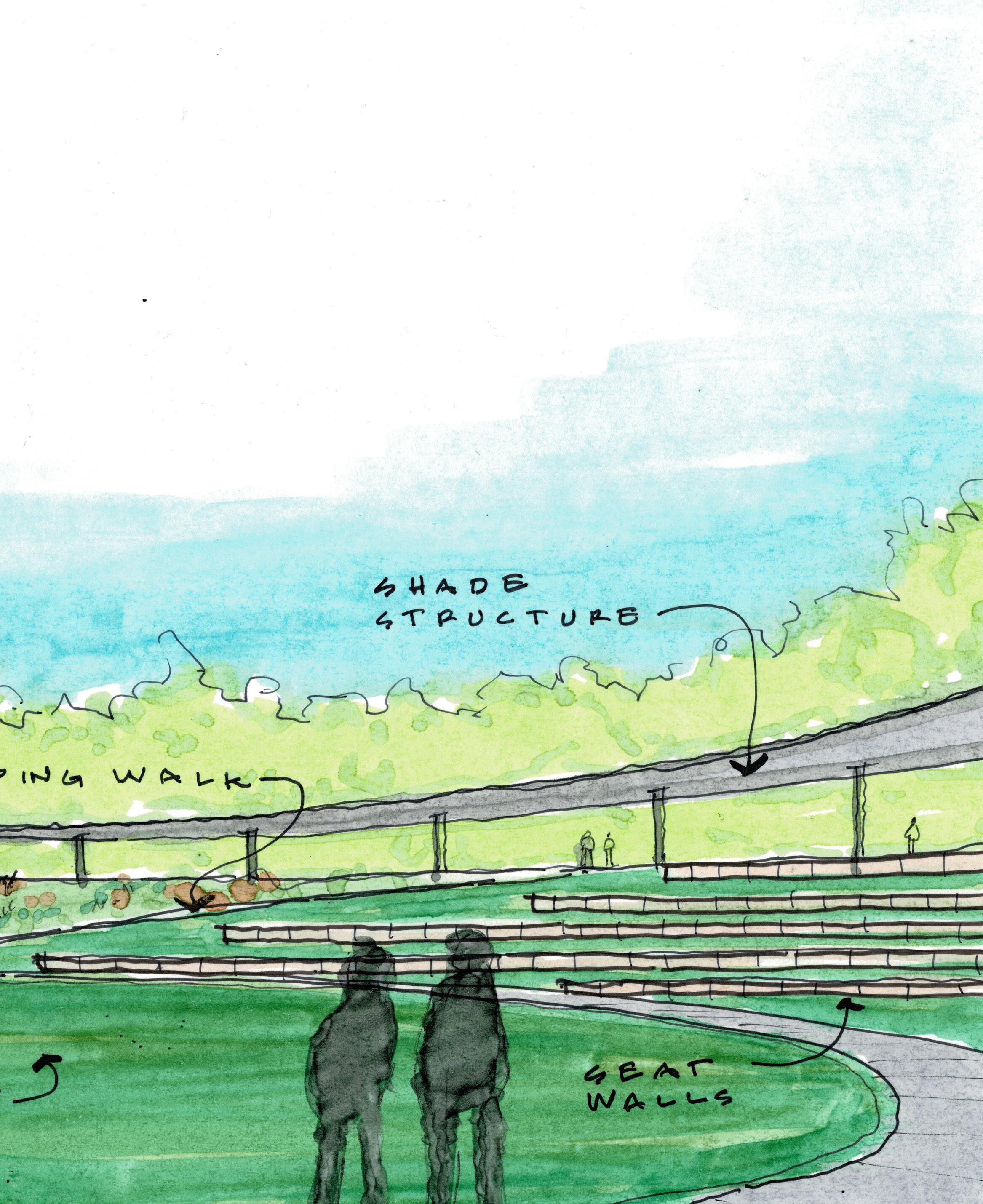

Moment 1: Arrival (Middle Terrace)

Visitors enter from the east — the direction of the sunrise, representing new beginnings — and are welcomed into an expansive space surrounded by trees and native plantings.

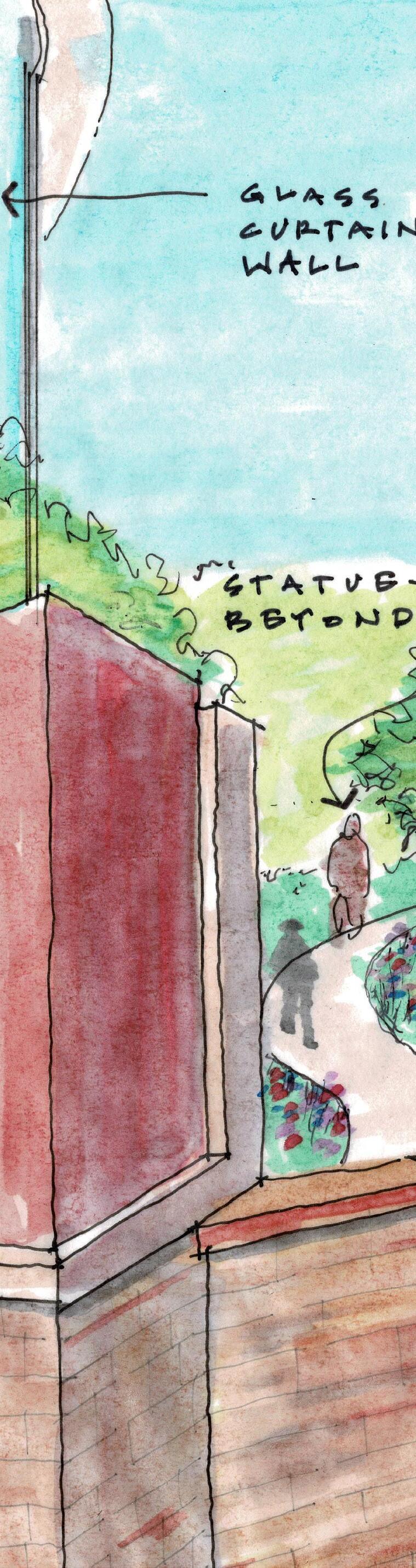

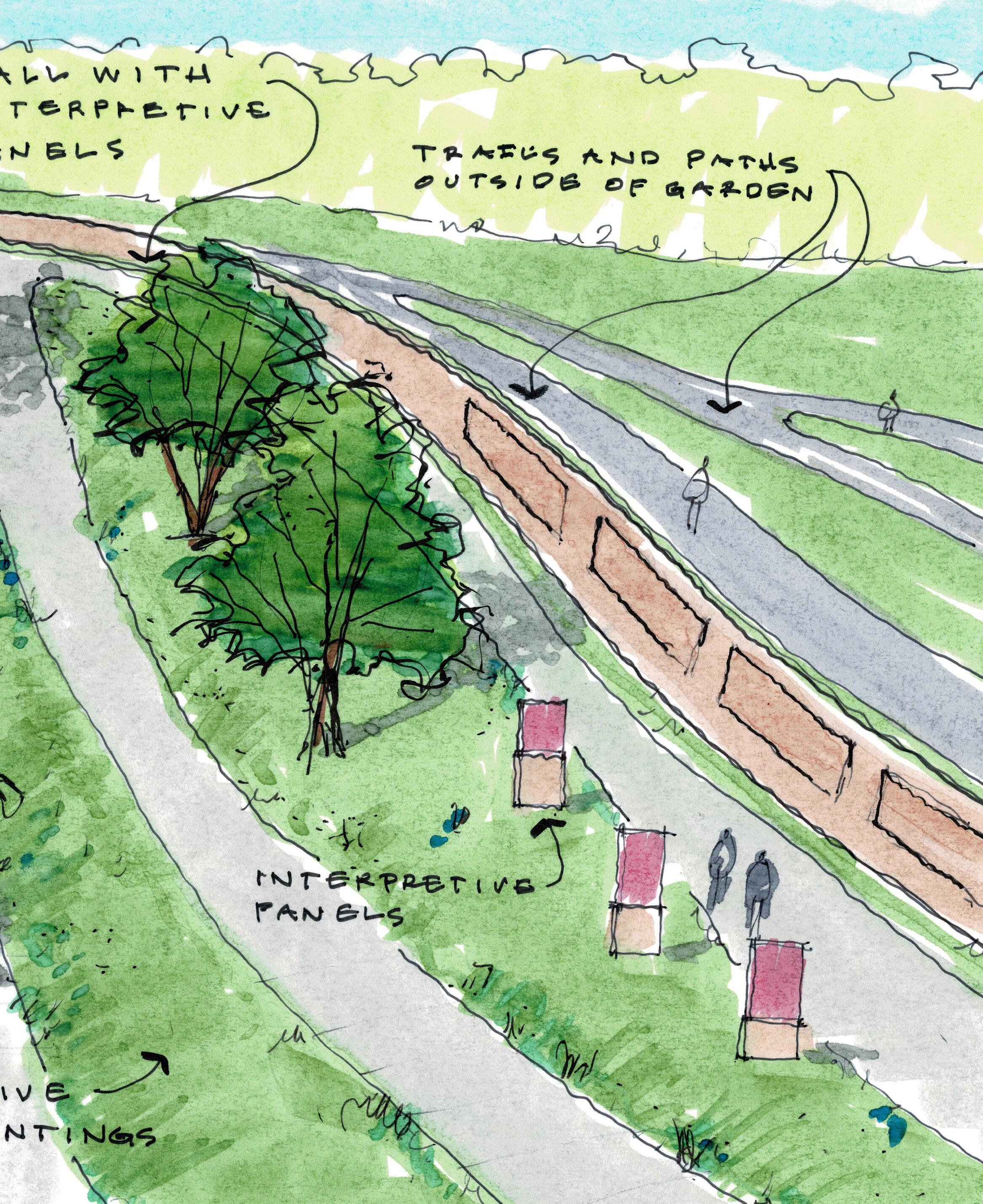

Moment 2: Historic Content & Timeline (Lower Garden)

Visitors encounter a timeline experience that honors community members’ desire for the truth about Columbus and an accurate reflection of their own stories.

Moment 3: The Statue (Lower Garden)

Visitors are invited to experience the recontextualized Columbus statue, which is placed northward — the direction of the winter winds, representing trials and necessary cleansing — and at a more human scale. Standing at ground level and not on a plinth, the statue no longer towers over viewers but allows them to be face to face with the explorer and everything, for better and worse, that he represents.

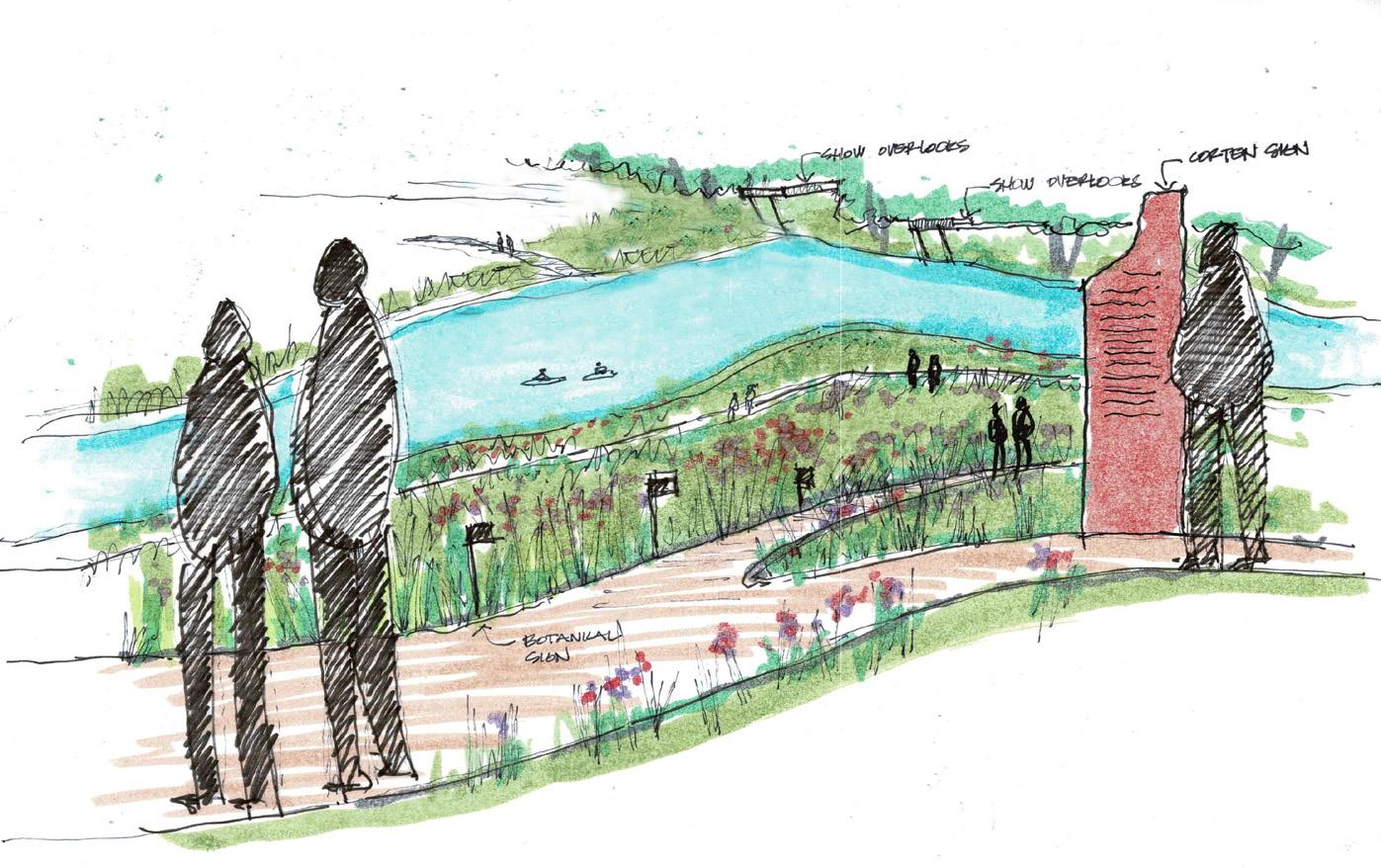

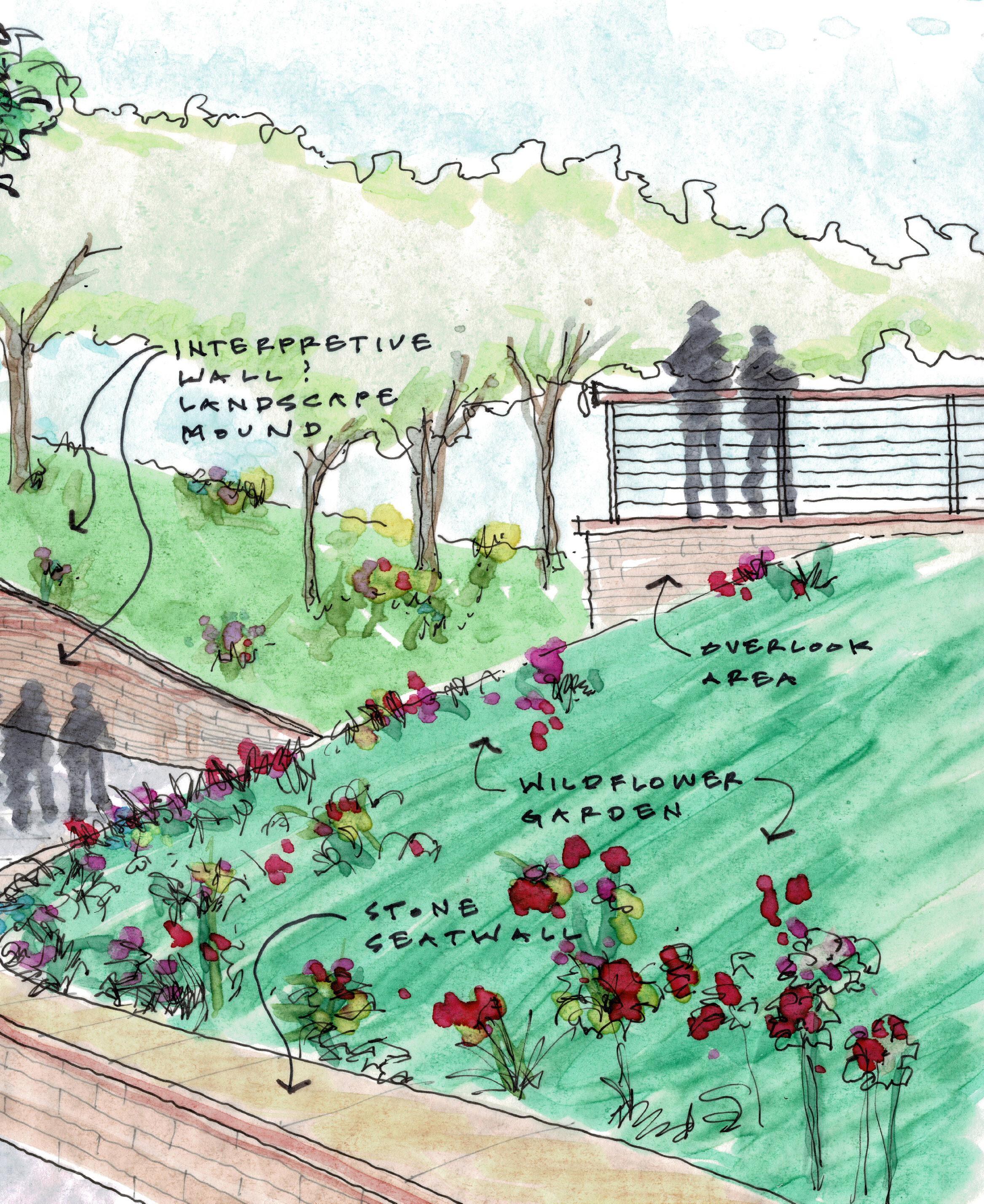

Movement 4: Reflection (Lower Terrace)

Following the statue experience and timeline, visitors can choose to reflect upon their experience and ground themselves in nature within a sheltered space that offers an expansive view of water and native plantings.

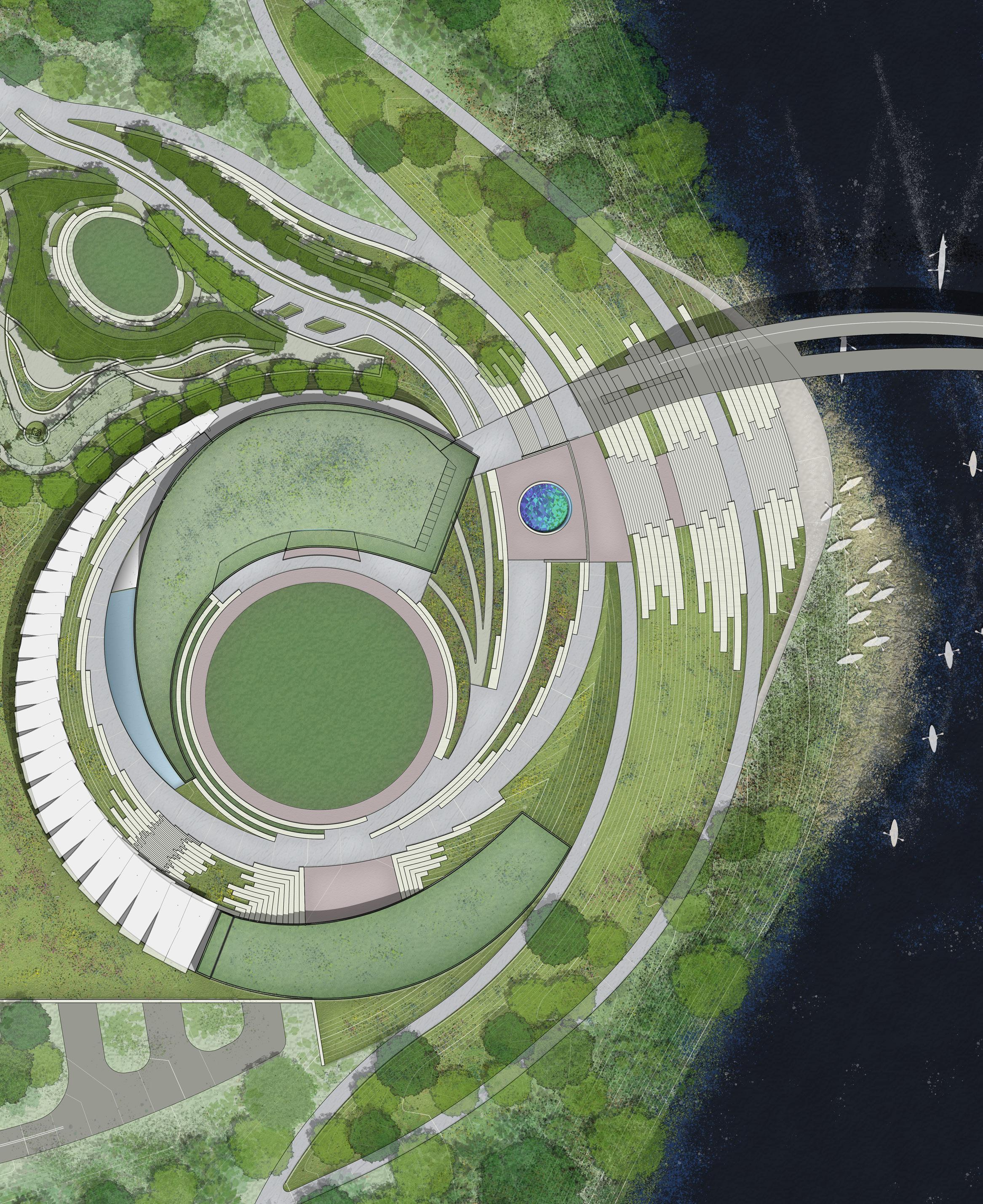

Moment 5: Nature Play & Learning

Opportunities to interact with nature are scattered throughout the space, with some options that are designed and others that are wild. Access to water, rocks, trees, and dirt allows visitors endless possibilities for unscripted play, exploration, recreation, and groundedness.

Moment 6: Community Gathering Space

Visitors head westward — the direction of community, introspection, and maturity — to gather with others at the central lawn, which is fully equipped with event infrastructure and features concentric seat walls and shade structures. An indoor community hall and event venue (not pictured) borders the space and invites deeper understanding of the difficult ideas presented throughout.

Moment 7: Looking to the Future (Upper

Garden)

Visitors experience breathtaking views of the gardens, the space in its totality, the river, and the city skyscape beyond. They are inspired by the scene before them, and at peace.

CONCLUSION

Book 4 has traced the process to envision a space in which to reinstall and recontextualize the city’s Christopher Columbus statue, in a way that honors the truth of his legacies and their impacts. The design sketches presented here were undertaken soon after the team coalesced around values inspired by an Indigenous poem evoking what the site should be, and upon exploration of other places where difficult histories are truthfully told. They reflect the early stages of an effort to create a space that is about more than the statue, a space that also offers opportunities for individual and community healing through nature, togetherness, learning, play, and reflection. Final project renderings can be found in Book 5, which is the culmination of all the research, community engagement, and design exploration for the Reimagining Columbus initiative.

SOURCES

FIGURES

Indigenous Design Principles

FIGURE 3.0. Indigenous Design Studio+Architecture, composite digital image, 2025.

FIGURE 3.1. Indigenous Design Studio+Architecture, composite digital image, 2025.

FIGURE 3.2. Indigenous Design Studio+Architecture, composite digital image, 2025.

Sketching the Vision

FIGURE 4.0. TarHeel4793, August 25, 2015. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columbus_Circle_in_New_York_City.jpg

FIGURE 4.1. Conkis, James, July 25, 2020. https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christopher_Columbus_Monument_Arrigo_Park_Chicago_2020_ July_25-2126.jpg

FIGURE 4.2. Hovland, Ben, "Facing criticism, Walz says there will be consequences for those who toppled Columbus statue." Pioneer Press, June 10, 2020. https://www.twincities.com/2020/06/11/facing-criticism-walz-says-there-will-be-consequences-for-those-who-toppled-columbus-statue/

FIGURE 4.3. Conley, Elizabeth, Houston Chronicle, June 11, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/houstonchronicle/photos/a-statue-of-christopher-columbus-holds-a-sign-and-is-painted-red-at-bell-parkin/1661151997378072/?paipv=0&eav=AfbQqDsV42yvxEymSE8chg-2j8b04mlAJPOtGQflhmh3MaCPf-VItxL9qhUvuo-vHyw&_rdr

FIGURE 4.4. Shishmanian, John, "From Columbus to Italian Heritage: The evolution of a Norwich monument." NorwichBulletin.com, October 8, 2021. https://www.norwichbulletin.com/picture-gallery/news/2021/10/08/replacing-christopher-columbus-norwich-italian-heritage-monument/6057504001/

FIGURE 4.5. "Christopher Columbus Statue Pulled From Water In Baltimore." CBS 13WJZ. Still image from video footage, July 6, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bFdjWNYJ6ek

FIGURE 4.6. N Giovannucci, August 27, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christopher_Columbus_Monument_boxed_in_Marconi_Plaza_Philadelphia_PA_(June_2020)_(DSC_4035).jpg

FIGURE 4.7. Panico, Rebecca, " Columbus statue removed from N.J. park in 2020 to be loaned to church." NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, April 10, 2024. https://www.nj.com/essex/2024/04/ columbus-statue-taken-down-from-nj-parkin-2020-to-go-on-loan-to-church.html#:~:text=A%20monumental%20statue%20of%20 Christopher,church%20with%20Italian%2DAmerican%20roots.