PEACEFUL PREDATORS

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2025

Colorado’s mountain lions endure the wild winter

ISSUE NO. 81 | NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2025

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2025

Colorado’s mountain lions endure the wild winter

ISSUE NO. 81 | NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2025

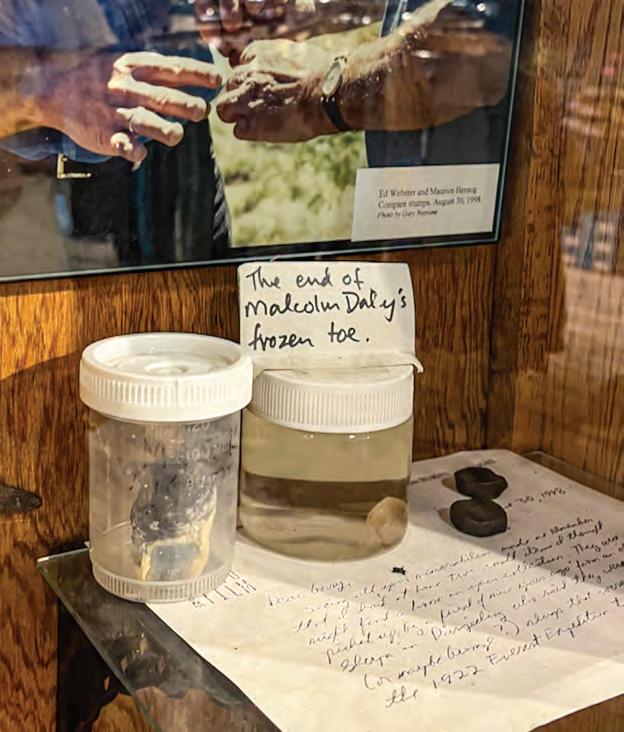

14 The Man Who Collected Mountains

Thousands of alpine artifacts inside Neptune Mountaineering tell the story of outdoor history dating back to the 1800s – including a frostbitten toe. story by Ariella Nardizzi photographs by Matt Crossley

18 Ghosts of Winter

As snow quiets Colorado’s mountains, elusive mountain lions prowl the same land that sustains us, moving throughout the cold half of our shared world. by Ariella Nardizzi and Chris Amundson

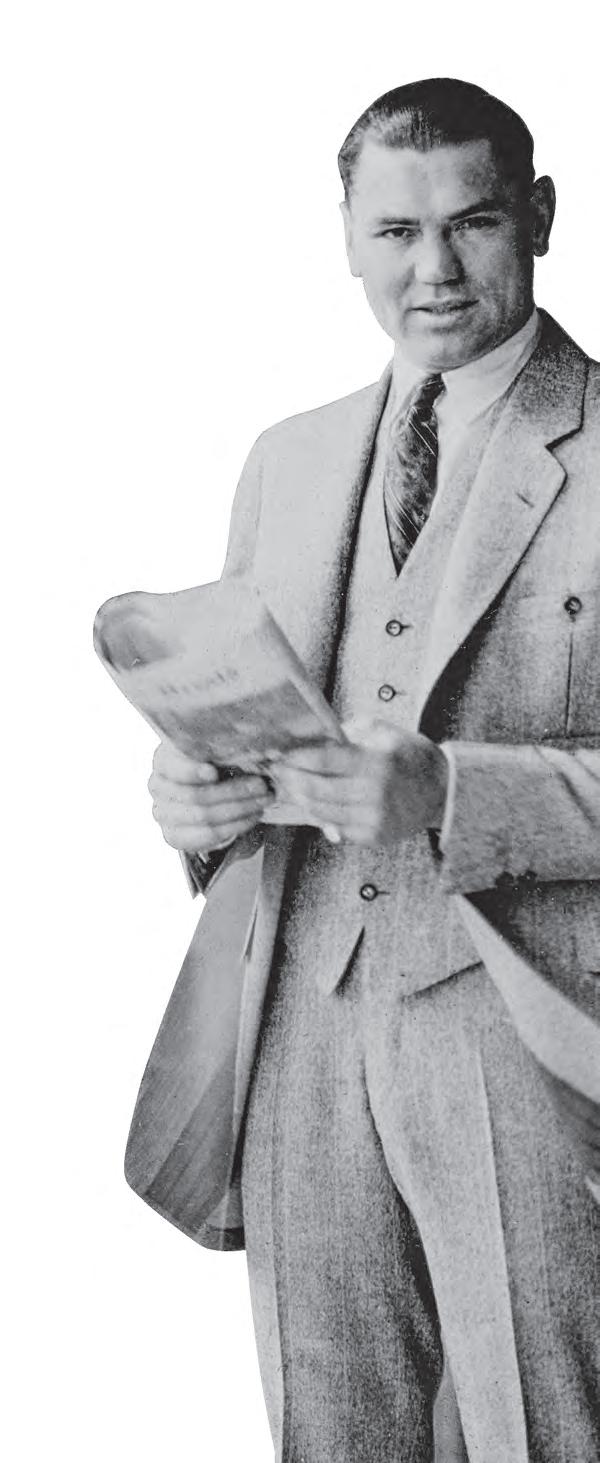

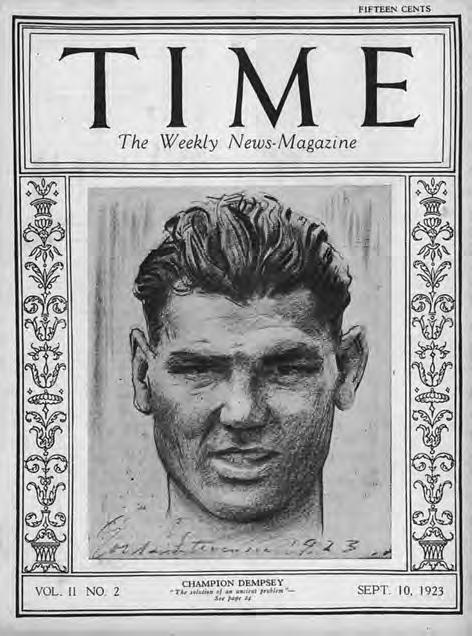

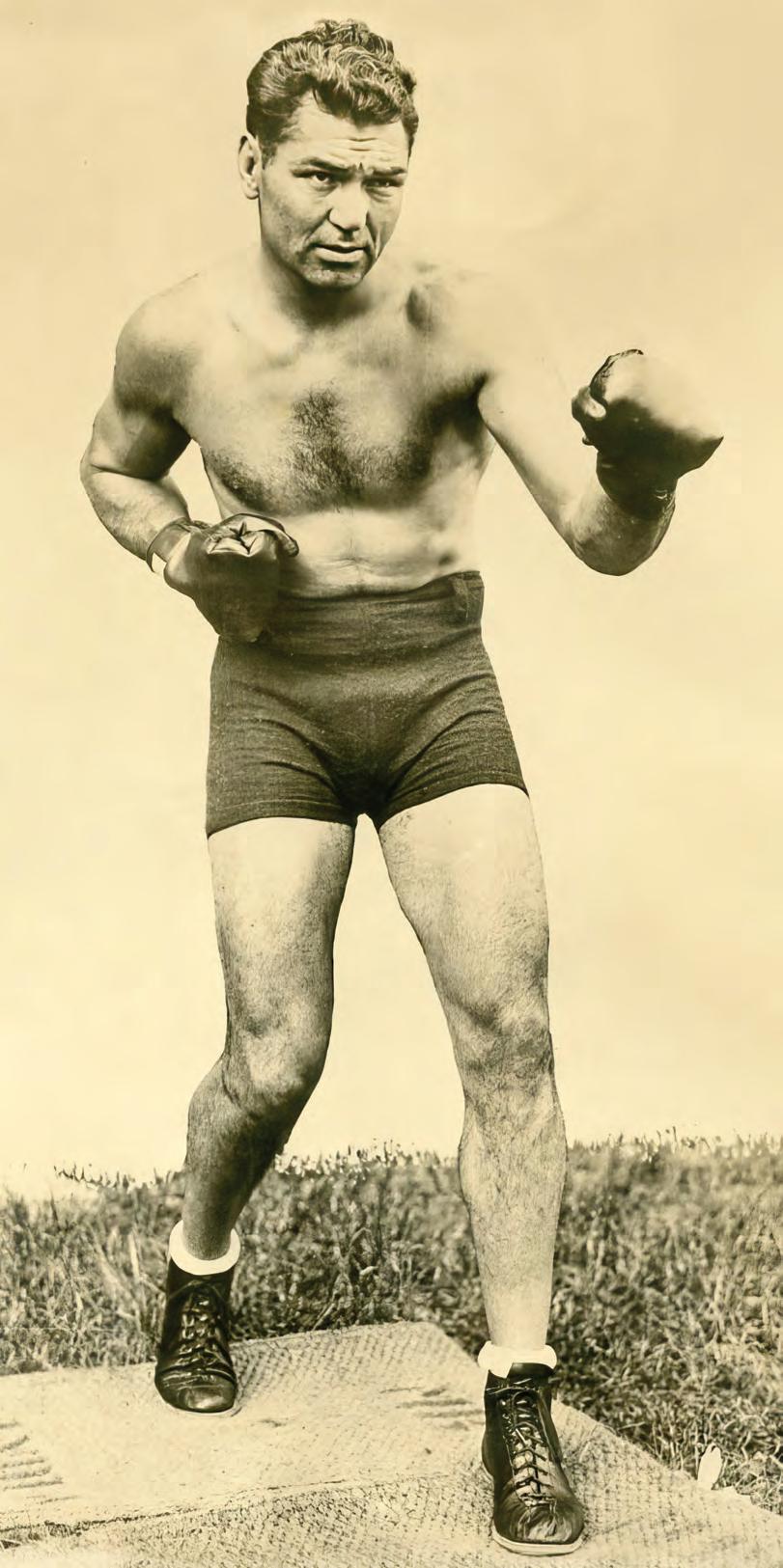

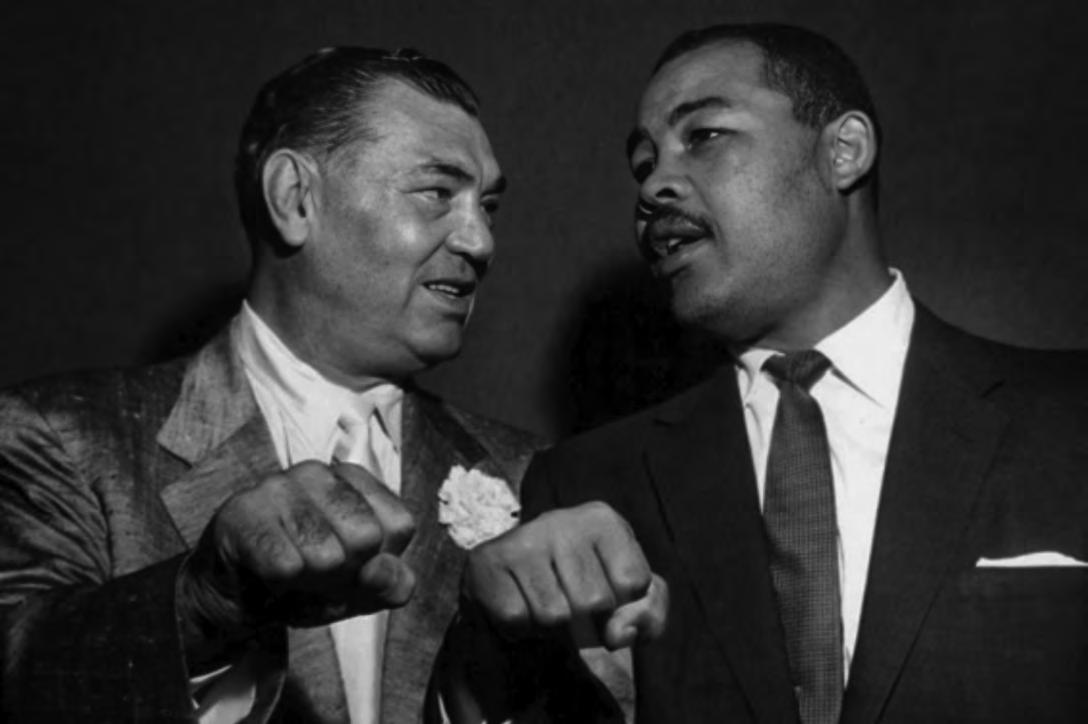

26 The Manassa Mauler

From a hardscrabble childhood to the world arena, Colorado’s legendary boxer Jack Dempsey fought his way from poverty to world heavyweight champion –one punch at a time. by Ron J. Jackson, Jr.

46 The Heart of South Park Turns Again

Volunteers rebuild the historic 1881 Como Roundhouse, restoring both the locomotive and Colorado’s vibrant railroad past. story by Eric Peterson photographs by Erik Makić

7 Editor’s Letter

Chris Amundson shares stories from life in Colorado.

8 Sluice Box

The Gondola Shop in Fruita creates and restores colorful cabins; Jared Steinberg paints his love affair with Colorado; The lore of grizzly Old Mose’s reign of terror in the southern Rockies.

12 Trivia

Test your knowledge on Colorado’s steamy hot-springs secrets. Answers on page 42.

A mountain lion (Puma concolor) glides through fresh snowfall before midnight near Estes Park, every muscle and whisker caught sharply by a camera trap. Story begins on page 18.

PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT YONE

Kitchens

Bright, tangy cranberries bring holiday color and cheer to Colorado tables.

Poetry

Poets find endurance in hope and beauty in winter’s quiet, steadfast defiance.

40 Go.See.Do.

Take an Electric Safari at Colorado Springs’ Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, then watch cowboys and bull riders trade horses for skis at the Cowboy Downhill in Steamboat Springs. 52 Camping

Camping doesn’t stop when the snow starts. Hunker down with moose in the backcountry at State Forest State Park. 54 Peak Pixels

Joshua Hardin shares photography tips for capturing lunar landscapes that glow with celestial drama under the full moon.

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2025

Volume 14, Number 6

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Editorial Assistant

Savannah Dagupion

Design

Mark Del Rosario

Photo Coordinator

Erik Maki

Staff Writer

Ariella Nardizzi

Advertising Sales

Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Shiela Camay

Colorado Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130

Fort Collins, CO 80527 970-480-0148 ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit ColoradoLifeMag.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com or visiting ColoradoLifeMagazine.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

BY DECEMBER, DAYLIGHT in Colorado feels scarce. The sun rises late; shadows stretch long before dinner. Golden and slow, morning sun slides through the windows like honey over the counter. Then it’s gone again, leaving that blue hush that belongs only to winter.

It’s tempting to call this the darkest part of the year, but that isn’t quite true. The light doesn’t disappear; it changes character. It lingers in smaller places: a porch lamp glowing through snow, a woodstove’s pulse of orange, headlights winding down a canyon road. Across Colorado, we learn to notice the glow for what it is – something that endures quietly, not something that fades.

Each Thanksgiving morning, I find that kind of light in our kitchen. My wife moves easily between the cutting board and the oven, preparing the turkey and her cranberry bread that fills the house with citrus and spice. Steam curls above the sink as morning sun glints off the counter. The light around her is the softest of the year – half daylight, half devotion.

A day or two before, the sound of tires on pavement and the crunch of snow announce our three children’s return from college. Their headlights sweep across the yard, doors open and voices spill from the mudroom, the kind of laughter that makes a house feel alive again. For a few days, the rooms glow brighter, and the rhythm of family returns.

Out beyond the warmth of town, Colorado’s mountain lions keep to their own quiet paths. They move through drifts with the same steady grace my wife carries in the kitchen – patient and sure that what’s essential endures.

A mother lion carries her young through almost three months of gestation before bringing a litter of spotted cubs into the snow. She shelters them in rock and brush through the hardest season, keeping them hidden until spring light returns. Watching my own family gather and grow – first small hands at the counter, then headlights sweeping back into the driveway – I’m reminded that human love, like that lion’s care, depends on patience and faith. You protect it, tend it, and trust that warmth will return in its time.

When the house quiets again, that light doesn’t fade; it spreads outward. It moves across towns and valleys, settling wherever people put their hands to good work.

The same light that fills a home finds its way into the work of Coloradans whose devotion helps what they tend endure across generations. The gleam of a well-oiled gear in Como and the shine on a boot in Gary Neptune’s museum are small lamps against the dim of time.

But light isn’t just in the gear or glove; it’s in the hands that keep them – in Gary Neptune teaching the next generation of climbers the stories behind his mountains, and in the Como volunteers showing the next pair of hands how to keep the roundhouse turning.

Maybe that’s Colorado’s truest gift: not the spectacle of summer with alpine valleys ablaze with wildflowers, but the steady glow that stays when the color fades. It lingers in smaller gestures – a lesson shared, a knock at a neighbor’s door, a hand offered on the ice, an invitation to share a meal. These moments of care keep the cold at bay, proof that light lasts when it’s shared.

As snow deepens and the year turns, may that enduring light find you, in the quiet of your work, in the patience of your care, in every small kindness that helps keep someone warm.

Even the softest glow can outlast the dark.

Chris Amundson Publisher & Editor editor@coloradolifemag.com

After their mountain days end, Colorado’s gondolas find new lift in Fruita.

by ERIC PETERSON and CHRIS AMUNDSON

Every skier in Colorado knows the feeling – boots clunking on metal, gloves tugging a frosty door, friends crowding into a gondola for the climb. The ride offers a breather between runs, a quiet minute to watch spruce blur past and snowflakes skitter across the glass. For decades, these cabins have carried millions to the high country’s happiest places.

But even gondolas grow old. Their paint fades, their windows scratch opaque from ski poles and board edges. When resorts retire them, they’re lined up like worn-out workhorses behind maintenance barns –relics of long powder days.

That’s where Dominique Bastien comes in. From her 10-acre workshop outside Fruita, she restores the faithful cabins and sends them back into the world – this time as bars, dining pods, DJ booths or backyard hideaways.

Originally from Montreal, Bastien stumbled into the business in 1998 after spotting fogged windows at British Columbia’s Whistler Blackcomb. Curious, she asked to take a few home to practice polishing them back to clarity. Her experiment worked, and Sunshine Polishing Technology was born.

What began as a side hustle soon grew into a career that took her from Canada to ski resorts across North America and Europe. Bastien earned a reputation for speed and precision and even developed custom sandpaper with 3M to perfect the shine. “I love being the only one in the world who does this,” she said. “Whistler tried to hire someone else, and I think he did one gondola in a day. We were doing 45 or 50.”

In 2012 she moved the company to Colorado, where her client list already read like a map of ski country. “For years, we were juggling temporary visas, always stretching things,” she said. “Then my immigration agent finally told me, ‘Maybe

it’s time you just go live there.’ ” Business was steady until the pandemic brought the ski world to a standstill. “Overnight, everything stopped,” she said. “No gondolas running meant no gondolas to polish.” In her Fruita yard sat more than a hundred cabins she’d bought years earlier from Vermont’s Killington Resort, old steel shells waiting for purpose. With resort work frozen, she began repainting them, adding benches, lights and heaters.

A few months later, towns like Mountain Village above Telluride came calling, looking for outdoor dining options. Bastien’s retired gondolas made their comeback, a quirky, perfect Colorado solution born from crisis. The Gondola Shop was officially in motion.

Today Bastien’s 10-employee crew works in 30,000 square feet of shop space, giving about a thousand gondolas new lives. Some roll out as food or beverage kiosks, others as photo booths or private lounges. Each refurbished cabin today can

cost about $20,000, depending on the level of customization.

“We have a massive waiting list,” she said. “The market ranges from companies and event planners to Mrs. Smith, who wants a gondola in her backyard.”

One of those customers, Sarah O’Donnell, runs Mecca Bar Co. in Millcreek, Utah. Searching for a centerpiece for her mobile events business, she bought two custom gondolas in 2024 – one a bar, one a photo booth. “They’re awesome,” O’Donnell said. “It adds that X-factor to our brand.” She also admired the shop’s makeup. “Most of her team is made up of women, which I think is really cool, because the fabrication industry isn’t known to be dominated by women.”

Back in Fruita, Bastien still keeps an eye on the mountains. The same cabins that once climbed Colorado’s peaks now sparkle again under desert light, ready for their next run – reminders that in a ski state, even old gondolas can find new lift.

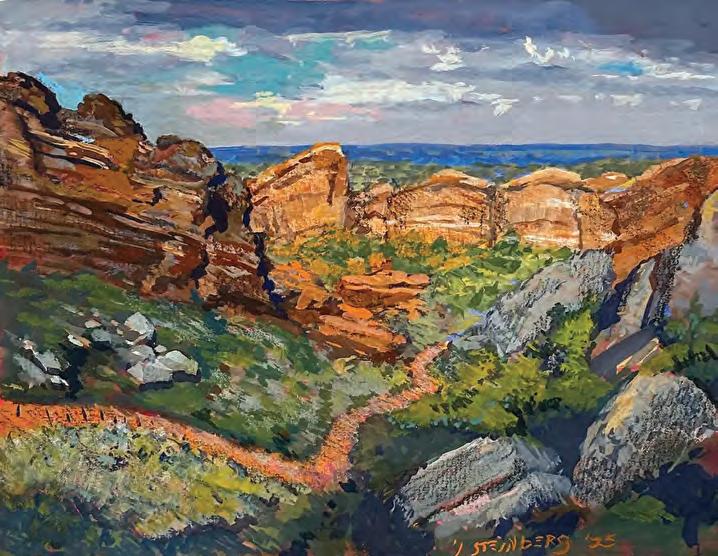

Denver artist Jared Steinberg paints the Colorado he knows by heart

by CORINNE BROWN

The lights of Denver’s RiNo district glow against a deep cobalt sky as artist Jared Steinberg walks the streets. Music drifts from a nearby bar, streetlamps spill yellow across the pavement and murals bloom along the alley walls. He studies the angles of light, the rhythm of color and the fleeting gestures of a place he calls home – scenes he’ll later translate onto canvas in his studio a few blocks away.

A lifelong Denverite, Steinberg has always been drawn to the act of looking. As a boy he filled sketchbooks with city scenes; as an adult he learned to see through paint. Only in his thirties did he commit fully to art, studying at the Art Students League of Denver, Scottsdale Artists’ School and Watts Atelier of the Arts. His early oils centered on the energy around him – jazz musicians, brick facades, neon streets –before curiosity carried him abroad.

Traveling through England, Holland, Italy, Scotland and France, he stood beneath cathedral ceilings and studied masterworks he’d only known from books. “Observation is an act of participation,” Steinberg said. “A painting made from life might never be as exact as a photo, but it’s colored by the emotion and choices of its creator.” That revelation reshaped his practice.

Back home he found new meaning in familiar streets and the open spaces beyond: the alleys of RiNo, the glow of Blake Street at dusk, the broad light over Salida and Ouray. He begins with scenes gathered along his wanderings, translating their shapes and shadows into layered compositions. Adding and subtracting paint, he

builds until the surface hums with rhythm and light. The process, he said, mirrors memory itself – what we choose to keep, what fades and what remains vivid long after the moment has passed.

“My paintings of Denver and the greater Colorado landscape are rooted in a desire to preserve what’s quickly vanishing,” he said. “I try to trust my artist’s eye, painting as if on location but responding to the scene in a way that feels alive.”

Through those responses – from a canyon’s sunlit rim to the shadowed curve of a city street – Jared Steinberg paints connection itself: the pulse between place, memory and the fleeting light that holds them together.

See more of Jared Steinberg’s work or subscribe to his newsletter at jaredsteinberg. com. Follow @jaredsteinbergart on Instagram for upcoming Colorado exhibitions.

‘Old Mose’ terrorized southern

by ERIC PETERSON

As the legend goes, Old Mose was a monstrous grizzly bear who menaced the mountains of south-central Colorado from the 1870s to early 1900s. The bear was said to have killed three men and several hundred head of livestock, shaking off numerous bullet wounds and the loss of two toes to a 50-pound trap in the process.

Rancher Wharton Pigg made a mission of hunting the bear after it killed a few of his cattle, including a Hereford bull that it dragged a half-mile across the pasture. After an unsuccessful 1887 hunt, Pigg said the hulking Old Mose looked like “an elephant covered with hair.”

Newspaper headlines declared victory when hunter James Anthony finally shot and killed the beast in 1904: “Death of Old Mose, Terror of Stockmen,” reported the Cañon City Times The Denver Post echoed, “The King of the Grizzlies is Dead.”

Colorado writer Emma Ghent Curtis published a poem about Old Mose in 1905, telling “a story as grim as an ogre’s whim and wild as a were-wolf tale,” in which the bear terrorized ranchers with its “cursed trapmarked paw and ravenous maw.”

The real Old Mose wasn’t the villain he was made out to be. “The truth is the legend of Old Mose is almost all myth,” wrote James Perkins in Old Mose: King of the Grizzlies. The various human and livestock deaths were likely the handiwork of numerous bears over the course of 30 years, Perkins said. Old Mose just happened to be around to take the fall.

Coloradans in 1904 were hellbent on eradicating grizzlies. The state’s population dropped from about 800 grizzlies in 1880

to zero in 1980. The last confirmed grizzly sighting in Colorado came in 1979, when Ed Wiseman killed a bear in hand-to-claw combat near Pagosa Springs (“Grizzly Attack,” CL September/October 2015).

The bears fight on in Alamosa, where the Grizzlies are the mascot at Adams State University, and a super-sized bronze statue of Old Mose dominates Grizzly Courtyard.

Across town at the San Luis Valley Museum, Joyce Gunn said the saga of Old Mose conjures “sadness more than anything else.” The extirpation of grizzly bears has reverberated through Colorado and the Rockies. “We don’t really understand the ecosystem and how fragile it is,” Gunn said.

Old Mose’s story is much different from the bear’s perspective, she added. That tale involves a hungry bear struggling to survive in the face of human encroachment. Those cows weren’t exactly innocent bystanders.

“History’s written by the winners,” she mused. “As my grandfather always told me, ‘Pretend you’re the loser. It gives you a different perspective.’ ”

Can you handle the heat?

by BEN JENKINS

1 With a depth of just over 1,000 feet, what Archuleta County location, whose name means “healing waters,” is the deepest geothermal hot spring in the entire world?

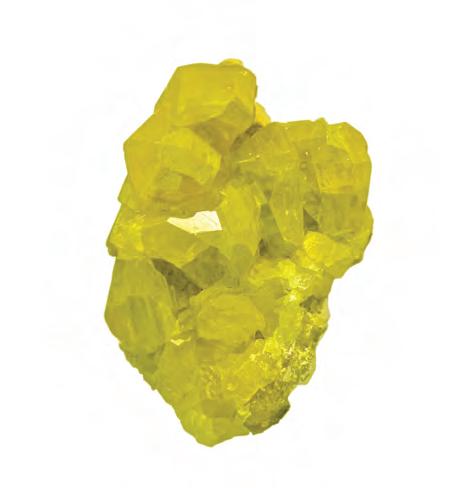

2 Before you see Iron Mountain Hot Springs’ dazzling emerald pool or feel its luxurious geothermal waters, you’ll get a whiff of its distinct odor. What element of the periodic table is responsible for its rotten egg aroma, which is commonly smelled near geothermal pools?

3 Many resorts around Colorado hot springs offer a form of water massage which was developed specifically for hot springs in the early 1980s. Adapted from Zen Shiatsu massage, what is this aquatic therapy called?

4

405 feet long and 100 feet wide at its maximum, what Colorado resort’s Grand Pool is the world’s largest hot springs pool, holding more than one million gallons of water?

5 No word on whether he went for a swim, but the former ghost town of Dunton Hot Springs (now a resort) was once visited by what legendary leader of the Wild Bunch who stopped there after his first ever bank heist in Telluride?

MULTIPLE CHOICE

6

Despite its name, there aren’t actually any hot springs in the city of Colorado Springs. Which of these hot springs comes the closest?

a. Iron Mountain Hot Springs

b. Mount Princeton Hot Springs

c. Valley View Hot Springs

7 Located near the city of Steamboat Springs, Strawberry Park Hot Springs is just outside which of Colorado’s eleven National Forests?

a. Routt National Forest

b. San Isabel National Forest

c. Arapaho National Forest

8

Many states in the Eastern U.S. don’t have any hot springs at all, but thanks to the Rocky Mountains and their shifting tectonic plates, the west is full of them. How many known hot springs are there in Colorado?

a. 819

b. 93

c. 48

9 What is most notably “optional” at Colorado hot springs like Valley View, Mountain Air Ranch and Conundrum?

a. Reservations

b. Clothing

c. Donations

10 Surrounded by the Maroon Bells near Castle Peak, Conundrum Hot Springs are the hot springs with the highest known altitude in Colorado, and among the highest in all of North America. How many feet above sea level are they?

a. 4,800

b. 8,700

c. 11,200

11

The hottest hot spring in Colorado reaches water temperatures as high as 220 degrees Fahrenheit.

12

Dakota Hot Springs in Penrose is located on the site of a former oil well that accidentally tapped into water.

13

Among the many naturally occurring minerals in the water, arsenic is one of the elements commonly found in the hot springs of Colorado.

14

The best is in the west, apparently. There are no major hot springs or hot spring resorts in Colorado east of Interstate 25.

15

Due to the ancient rock there, the water at Radium Hot Springs is as radioactive as getting 10 x-ray scans an hour.

No peeking, answers on page 42.

TUCKED IN A CORNER of South Boulder, a mountaineering shop doubles as a museum. Between racks of new climbing gear, ice axes from the 1930s hang beside expedition jackets and boots once used on Everest. Every climber leaves something behind – wooden skis, a boot print, a story – and Gary Neptune has spent a lifetime collecting them.

Neptune Mountaineering houses one of the most extensive mountaineering memorabilia collections in the country, telling the story of outdoor history through the tools that carried people to the world’s highest places. Half a century after opening the shop, Gary Neptune remains its quiet curator, tending to the glass cases and memories alike.

But the true museum isn’t just in the gear – it’s in Neptune himself.

story by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

photographs by MATT CROSSLEY

For decades, he’s amassed an impressive treasure trove of alpine history, with artifacts dating back more than a century. Leather boots worn on the first known summit of Mount Everest. Wood-plank skis with leather toe straps. Hand-forged alloy pitons from Yvon Chouinard, world-class climber and founder of Patagonia. A comic strip pinned beside tattered jackets pokes fun at the “brain damage” it takes to be a mountaineer.

The most fascinating relic might be Neptune himself – equal parts climber, collector and historian.

NEPTUNE WAS NEVER supposed to become a mountaineer. The son of a traveling oil salesman, he spent his childhood moving – living everywhere from Missouri to Louisiana to New York to Egypt – rarely staying anywhere long, and never near mountains. He also had asthma as a kid, and unable to play team sports, he turned to gymnastics.

The first book he read as a child was Our Everest Adventure, a pictorial account of a British expedition. None of the adults in his life could explain the photographs or terms. “I remembered concepts, names of mountains and photos from that book for years after,” he said. “That’s what lit the spark.” A copy of the hardcover now sits in an exhibit at the back of the store.

Neptune made his way to Boulder in the 1960s, not for the scene but for the outdoor access. “I wanted to live in a place I could climb before and after work. During work, too,” he said.

He spent years fixing boots and scrambling the Flatirons. In 1973, he used a small inheritance to open Neptune Mountaineering. The shop was just barely 1,000 square feet.

In Boulder, Neptune lived in a trailer, grew his own vegetables and biked a mile to the shop each day. He sold climbing gear and offered boot repairs. His customers were dirtbag climbers, his profit margins nonexistent.

But Neptune kept climbing. He saved every penny and summited peaks including Everest, Ama Dablam, Makalu and Gasherbrum II. He repeated ski routes around Colorado with handmade wooden skis and climbed in Eldorado Canyon on old gear to understand what early pioneers felt. He even plucked pillow feathers to sew his own down pants for his Everest expedition. “I never saw it as sacrificing things,” he said. “I was just doing what I loved.”

Years of expeditions left him with more memories – and more gear – than his small home could hold.

“I ran out of room in my basement,” Neptune said. “So I started hanging stuff on the shop walls.” At first, it was his own gear. Then customers began donating, and friends mailed him relics from around the globe, many with handwritten notes or stories passed down for generations.

By 1983, he had moved into a larger space on South Broadway in Boulder’s Table Mesa neighborhood, where the shop still sits at the foot of the Flatirons, a fitting backdrop for a climber’s museum. Alongside his growing collection, Neptune began hosting slide shows and talks by climbing partners recounting their farflung adventures. A small crowd would huddle around a projector as his buddies described harrowing journeys in distant mountains. The store still hosts athletes for speaking events today.

TODAY, THE MUSEUM sprawls throughout the 20,000-square-foot Neptune Mountaineering store in South Boulder, where walls of new gear mingle with relics of mountaineering’s golden age. Neptune sold the business in 2013 and continues to live nearby in Longmont, still curating his exhibits with tireless precision.

He often drifts through the museum barefoot, padding between displays as if walking familiar trails. “I just like it,” he says with a shrug. “Shoes and I don’t really get along.”

When asked why there’s no digital inventory of every single item, Neptune smiled. “There’s a unique value in coming here and looking at it all – the timeline of history laid out across the store.” Hundreds of relics live here, though Neptune can’t be sure of the exact number.

He runs his hand along the worn wood of an old ice axe from the 1800s, its shaft smoothed by centuries of use. “The gear’s lighter now, more refined. But it’s really not that different,” he said. “Those early climbers figured it out first – we’re just following their lead. They’ve allowed us to go further, faster, higher.”

His collection interlaces with racks of new gear. The walls are lined with old crampons above the latest climbing shoes. Faded expedition posters and skis from Colorado’s 10th Mountain Division date back to the 1940s. Beneath a worn rucksack pinned to the wall, a bright red pack sits on the shelf for sale.

There’s a backpack from Tony Larsen’s unsupported North Pole trek, during which the explorer lost 60 pounds. Look

closely and you’ll notice the padding has been cut from the waist belt so he could pull it tight enough. There’s even a toe, not Neptune’s, but his friend Malcolm Daly’s. The frostbitten appendage sits in a small jar next to another toe, donated by a customer, Mike, who froze both big toes on Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park.

MORE THAN JUST gear, each piece tells a story, and it’s one Neptune usually knows by heart. He can recall who used it, where they went, what the weather was like. Sometimes, he’s the one who wore it. “When possible, I use the original gear if I repeat an important climb or ski route. I try to appreciate the experience from their perspective,” he said.

He’s skied Colorado’s Commando Run near Vail on antique wooden skis and climbed with rope-soled shoes. He even learned to make wooden skis in Minnesota and still uses them today.

Humor threads through the exhibits too. A comic near the crampons reads: “Brain

damage leads to mountaineering, study says.” Laughter often drifts from a corner of the store as a visitor catches one of the quips tucked along the walls.

In the fast-moving world of retail chains and new gear, the Neptune Moun taineering remains defiantly analog. It’s a gear shop, yes – but it is also a living archive. A museum curated by a man who cut his own skis, made his own gear and built a climbing community in Boulder since the 1970s.

“Gary Neptune’s legacy as a pioneering climber, longtime specialty retailer and gear expert lives on through the museum,” said store owner Maile Spung. “The equipment he sold and used for decades is preserved in one of the most unique mountaineering collections in the world.”

But Neptune will never brag. He’ll probably deflect and tell a story about someone else.

That’s the story he’s been telling all along – of the climbers who left something behind, and of the man who chose to preserve it all.

The museum showcases thousands of relics, like primitive ice axes and canes from the 1800s. Neptune frequently utilizes this historic gear for his own outdoor endeavors to appreciate the experience from a pioneer’s perspective. He’s skied in Vail on antique wooden skis and climbed in rope-soled shoes at Eldorado Canyon.

Colorado’s mountain lions share the same mountains we call home

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI and CHRIS AMUNDSON

SNOW SOFTENS EVERYTHING. It quiets the towns that cling to the mountainsides and muffles the highways that thread through the passes. Inside, families gather near the fire, boots drying by the door. Children press their faces to fogged windows while night settles over the Rockies. Skiers will wake early to chase fresh powder; others will snowshoe through forests sealed in silence. Beyond the reach of porch lights, a mountain lion moves.

Near Estes Park, a female and her juvenile investigate a territorial mark. Males may range hundreds of miles but females remain close to their winter dens and young.

Winter reshapes its world as surely as it does ours. When storms seal the high passes, deer and elk drift downslope toward the valleys, and Puma concolor follows. The lions move along the same ridgelines hikers cross in summer – silent as snowfall, muscles coiled under tawny fur. In deep drifts each stride is measured and efficient. Short steps conserve warmth and strength. Snow gathers on their backs and melts in slow rivulets when they pause to listen. They hunt where shadow meets motion. At dawn and dusk when light lies low and the forest glows blue, a lion slips between

Gambel oak and ponderosa pine, waiting for the sound of hooves on crusted snow. The attack comes in a blur, a leap from 30 feet, jaws closing at the base of the deer’s neck. The struggle ends quickly. The cat drags its kill beneath branches, covers it with needles or snow, and returns to feed over the coming nights.

Across Colorado about four thousand lions roam, solitary hunters in an expanse of mountains, mesas and canyons. Males hold territories that can stretch hundreds of square miles; females carve out smaller sanctuaries where they raise their spotted

kittens through the long winter. Those dens are worlds of warmth and vigilance. The mother grooms her young, listens for danger and teaches them to move without sound. Their chirps and mews are the only brightness in the stillness.

While the cats live by patience, people move through winter differently. We chase speed down ski slopes, laughter echoing across white basins. We gather in coffee shops, hands cupped around heat. We drive the same canyons the lions cross at night, our headlights brushing the dark timber but revealing nothing. Sometimes

in morning light a track appears near a trail or the edge of a driveway, a round print the size of a coffee mug pressed deep into new snow. For most, that faint trace is the closest they will come to Colorado’s most elusive predator.

Photographer Robert Yone learned how thin that distance really is. Living near Estes Park he built a camera trap: an old camera sealed in a waterproof case, a motion sensor and a pair of scavenged Nikon flashes. The first weeks yielded nothing, dead batteries, blurred tails, snowflakes caught midair. Then one morning he scrolled through

A mountain lion treads through snow near Fort Collins. As winter deepens, lions follow deer and elk to lower elevations where hunting is easier.

the memory card and found what he’d been waiting for: a lion striding through his frame, muscles taut, eyes bright in the strobe. Later came a pair of kittens pawing at his flash unit, their play frozen in light. Yone realized he was photographing a parallel world, one that began when ours went to sleep.

For the lion, winter is endurance. Each hunt risks failure; each step through snow burns precious energy. A night without a kill means another day of hunger. Still they remain – quiet, enduring, spread across more than half the state, thriving in the same landscapes where we build homes and ski resorts. Colorado Parks and Wildlife estimates their numbers as stable, even rising. They adapt, skirting our noise, slipping through drainages and across ridgelines while we stay inside and call it wilderness.

Now and then the two winters touch. Hikers find fresh tracks on a snowy trail west of Interstate 25. A rancher hears deer scatter in the brush beyond the fence. A motion-sensor camera clicks in the dark. These moments remind us that the boundary is thin, that the wild still moves through the same cold that sends us toward warmth.

By late February the days lengthen. Meltwater trickles down from the ridges, and the lion follows those hidden streams toward spring. The kittens grow bolder, testing their balance on rock ledges dusted with snow. In the foothills people pack up snowshoes and store their skis, ready for mud season and sunlight. Yet even as the world warms, the memory of that other winter lingers, the one lived beyond the porch lights.

Out there the mountains keep their own time. The lion remains, slipping through oak brush and timber, watching without sound. Its prints cross the same slopes we ski, the same valleys we photograph, the same forests where our fires glow at night. It lives in the cold half of our shared geography – patient and unseen – while the rest of Colorado keeps warm and waits for spring.

Captured by a remote camera in the Boulder Creek Watershed, a young male mountain lion prowls through his winter range. Most of Colorado’s population lives in mountain and canyon terrain on the state’s western side.

by RON J. JACKSON, JR.

TENS OF THOUSANDS of boxing fans caught their first glimpse of the rugged young pugilist when he climbed through the ropes July 4, 1919, in Toledo, Ohio, to challenge Jess Willard for his world heavyweight championship. Heat waves shimmered across the ring on a day some said reached 110 degrees. Dempsey’s mop of jet-black hair crowned an otherwise shaved head, and his bronze, muscular frame stretched 6-foot-1 and 180 pounds.

Jack Dempsey – a contender from “out West” – was a virtual unknown on the national stage. That would soon change. Few, however, could have predicted it on that fateful day.

The champion stepped into the ring “like a moving mountain,” Dempsey later recalled in Dempsey: By the Man Himself. The behemoth Kansan who had taken the

crown from Jack Johnson stood 6-foot-6 and 250 pounds, towering over the Colo rado underdog.

Then the opening bell rang.

Fans soon witnessed a shocking display of savagery as Dempsey mauled Willard relentlessly over three rounds. A thun derous left hook midway through the first dropped the champion to the canvas for the first time in his career – the beginning of the end. Dempsey swarmed with re lentless fury, knocking the bloodied giant down seven times in that opening round.

The beating continued through the next two rounds to the crowd’s stunned amazement. To Willard’s credit, he showed heart until finally his cornermen wouldn’t allow him to answer the bell for the fourth. Born into poverty in Colorado, Dempsey was suddenly the new heavyweight king of the world.

Reports from ringside claimed Willard suffered facial fractures, a broken jaw, missing teeth and broken ribs – all plausible given the punishment he took from Dempsey. Yet to those who knew his hardscrabble rise in Colorado, none of it came as a surprise. “The Jack we knew was peaceable,” said Susie Osborne of Uncompahgre, Colorado. “The Jack who got in that ring was downright vicious.”

The late Toby Smith, author of Kid Blackie: Jack Dempsey’s Colorado Days, summed it up best: “Colorado not only provided Jack Dempsey with a beginning, but it also gave him a destiny.”

So began the improbable rise of the Manassa Mauler.

THE SIGNS MAY have been there all along – or, at least, they should have been.

William Harrison Dempsey entered the world on June 24, 1895, in Manassa, Colorado, weighing a whopping 11 pounds. He was the ninth of 11 children born to Hiram and Celia Dempsey, but his mother sensed something special from the start. Years later she told her famous son – by then known as the Manassa Mauler – how that feeling began.

One day, before his birth, a stranger knocked at their cabin door peddling magazines. Celia offered him a glass of milk but explained they couldn’t afford anything he was selling. The man gratefully drank, then insisted on paying before he left.

“I wouldn’t hear of it,” said Celia, a tiny woman who never weighed more than 110 pounds. “So he gave me a useless, battered old book he was toting.” It told the life story of the famous John L. Sullivan, the last bare-knuckle world heavyweight champion. “I finished reading it before you were born,” she said. “When you came, so big and strong, I told everyone, ‘William will grow up to be the world’s champion fighter – just like John L. Sullivan.’ ”

And he did – though against all odds.

Poverty followed the Dempseys like a long shadow. Jack later called his childhood “rugged,” adding, “An old story, perhaps, but a painful one: too many mouths to feed,” and “a father with the wanderlust and almost no ability to make a decent living …”

Religion brought the Dempsey family to Colorado around 1880 from Logan County, West Virginia. A missionary from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints first planted the seeds of faith in the restless Hiram, who soon sold 300 acres of coal and timber land for a dollar an acre and loaded his family of four into a schooner headed west. Their trek ended in Manassa – a San Luis Valley frontier town founded a year earlier by Latter-day Saint pioneers.

Hiram and Celia joined the Church, though Hiram soon fell away. He even called himself a “Jack Mormon” – one who doesn’t entirely live by its teachings. He liked to drink and smoke and freely admitted to breaking most of the Church’s rules. “I know the Church is right,” he’d say with a grin. “I’m just too weak to live up to those rules.”

Celia often filled the breach left by her husband. One neighbor remembered her as the real fighter of the family. Petite yet formidable, she was both strict and tireless. None of her children dared cross her, and all loved her deeply. Still, love and hard work couldn’t always fill an empty stomach. In those desperate times, Manassa offered the Dempseys one enduring blessing: the quiet generosity of Church leaders and neighbors. When bishops sensed an empty cupboard, Jack recalled, it was “filled before nightfall –without comment.”

The scars of poverty hardened Jack’s resolve to climb higher in life. None cut deeper than when his mother fell ill in Leadville. Hiram decided she should travel the hundred miles to Denver to recover with their daughter Florence. Celia refused to go without her baby, Bruce; youngest daughter, Elsie; and Jack, then called Harry. She boarded the train with a single ticket, two ticketless children, a few coins and a baby in her arms.

The conductor wasn’t pleased. He demanded tickets for Elsie and Jack. “I’m very sick,” Celia said weakly, showing her small purse. “Okay, the girl can travel free,” he relented, then glared at Jack. “But that boy has to have a half-fare ticket, or he gets thrown off at the next station.”

The cruelty of those words gave Jack his first true taste of humiliation. Overwhelmed

Though his early life and career were riddled with hardship, it only fueled Dempsey’s determination for greatness. In 1919, Colorado’s native son became World Heavyweight Champion. A Time Magazine cover from 1923 depicts the boxer’s famous intense gaze.

by fear of being left behind, he froze until a kind man across the aisle leaned over. “I don’t think that conductor will bother you, kid,” he said quietly. “But tell your mother not to worry. If he insists on his money, I’ll pay it for you.”

Jack vowed in that moment to never be “humiliated” or “frightened” again – and he would only look back on that day when he needed the pain to drive him forward.

BOXING QUICKLY BECAME Jack’s only hope. Bernie, his brother 15 years older, had been a prizefighter when not laboring in Colorado’s mines. Jack called him his “idol” – not just for his toughness, but because he embodied manhood. Bernie gave Jack what their father never could – a model to follow.

Bernie taught him how to survive with grit, tenacity and a fierce work ethic. He also taught him to fight: how to make a proper fist, how to throw it and how to move. He drilled him on the classics – the feint, the jab, the counterpunch. In training, Bernie would rush forward, broom handle in hand, shouting for Jack to strike the stick to build speed.

By age 11, Bernie had him chewing pine resin to toughen his jaw and soaking his face and hands in beef brine three times a day to harden his skin “as tough as leather.” Jack kept those habits throughout his career.

By age 12, Jack was already training to be a prizefighter. The one thing Bernie couldn’t teach him was power. That came naturally – and first appeared when Jack was about seven, fighting a classmate named Fred Daniels at Manassa’s White House School. A crowd gathered as the boys squared off. Fred’s father shouted, “Bite him, Fred!” When the boy turned, Jack landed a crashing blow to his chin that knocked him cold. Legend says a local veterinarian had to revive him.

From then on, Jack was hooked on fighting.

Records of his early bouts are hazy at best. Most took place in saloons across Colorado, Utah, Idaho and Nevada, where he worked odd jobs in mining towns. By his own account, he began fighting for money around 1911, at 16, and estimated

he’d had “a hundred” such barroom brawls.

Like a young John L. Sullivan, the slender, 130-pound Dempsey would stand in the middle of a saloon and challenge any “son of a bitch in the house” to a fight. He would then add in his high-pitched voice, “For a buck.”

Dempsey discovered every Western saloon generally had at least one tough guy willing to accept his offer. Oftentimes they were hardened miners or rough-and-tumble cowboys, some outweighing him by more than 100 pounds. Dempsey admitted he probably looked like easy prey back then but bluntly added that he “murdered most of them.”

Dempsey’s first known professional fight took place Sept. 15, 1912, at the Moose Hall in Montrose. The Western Slope town held a special place in his heart because it

was where he’d seen his first prizefight as a child. Now, at 17, Dempsey was ready to start his own career, and he didn’t wait for it to come to him.

He ran into an old childhood friend, Fred Wood, a fair country pugilist who went by “The Fighting Blacksmith.” Dempsey asked if he’d be interested in a bout, and Wood agreed. The two promoted the fight themselves, renting the venue, selling tickets and splitting the gate receipts.

Dempsey fought under the name “Kid Blackie.” Bernie suggested the nickname after noticing his brother’s black hair and dark complexion. The name stuck for a while. Only later would he adopt the name Jack Dempsey in honor of his favorite fighter, Jack “The Nonpareil” Dempsey, the world middleweight champion from 1884 to 1891.

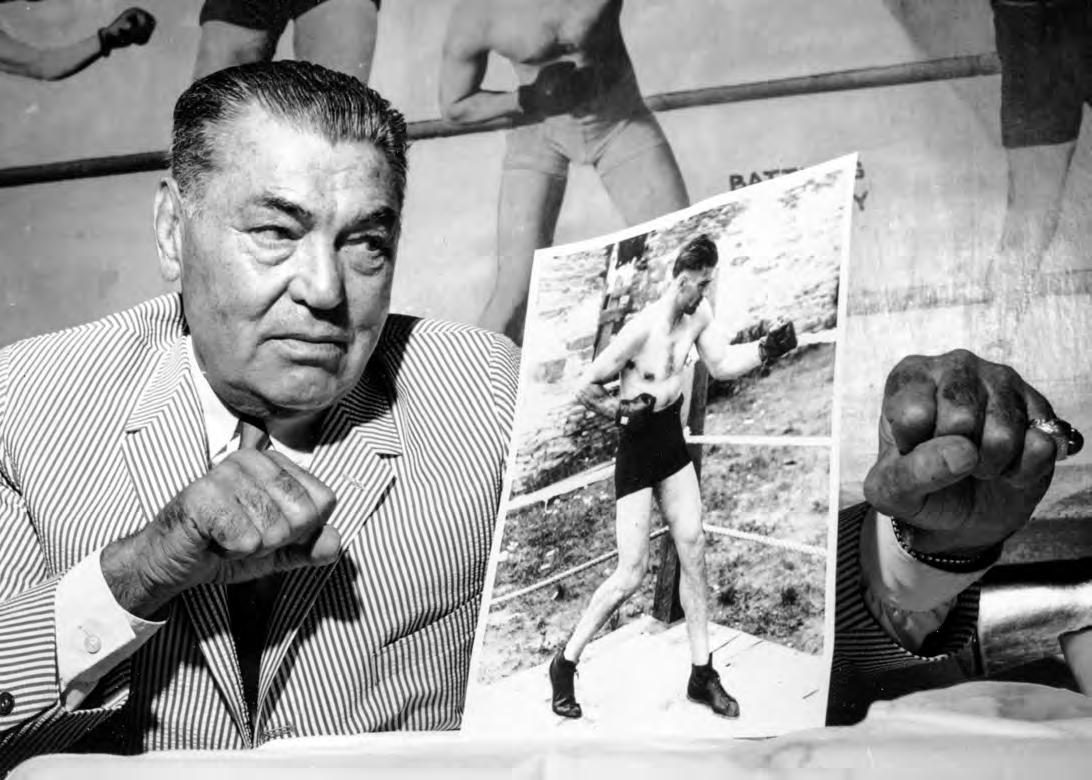

The former heavyweight champion poses with a photo of himself in action at the peak of his career, taken on his 70th birthday – June 24, 1965 – at a restaurant in New York City. During his early career, the fighter went by the name “Kid Blackie” for his black hair and dark complexion.

THE FIGHT WITH Wood didn’t go past the fourth round. Dempsey dropped him in the second but failed to finish him off, hesitating long enough for Wood to recover – a lapse that stood out for a fighter who later became famous for his killer instinct. Dempsey nearly paid for it when Wood came back strong, doubling him over with a shot to the midsection. But a round later, Dempsey surged back, unleashing a flurry of wild punches that knocked the blacksmith cold.

He quickly grabbed a pail of water and doused his game friend back to consciousness. Each man earned $20 that night for his trouble.

Little did anyone suspect Dempsey would go on to become world heavyweight champion less than seven years later.

Hardship paved his road. For the next few years, Dempsey crisscrossed Colorado

– often starving and desperate. He fought in towns like Telluride, Cripple Creek, Colorado Springs, Durango and Salida, logging at least 10 bouts outside the saloons. When he wasn’t boxing or hustling a fight, he took any work he could find. He labored in mines, baled hay, washed dishes, chopped wood, broke wild burros, scrubbed floors, cleaned windows – even begged for a meal when he had to.

“I never turned down a job anybody offered me,” Dempsey recalled decades later. “No matter what the pay. I’d rather go hungry than steal … I was a starving kid, wandering in search of food, sometimes almost like an animal, living as best I could and with the weapons of survival God gave me – my fists. And I guess my chin.”

His motivation in the ring came hardearned. In those days, he traveled like a hobo, “riding the rods” – clinging to two

narrow steel beams beneath a Pullman car. “There’s only a few inches between you and the tracks and roadbeds – and death,” he said. Falling asleep wasn’t an option.

Once, while catching a freight from Grand Junction to Delta, he climbed the ladder of a moving train. A railroad bull appeared above him, swinging a heavy club. He ordered Dempsey to jump, but the train was moving too fast. The man didn’t care. One blow split Dempsey’s head and sent him tumbling down a hillside. Groggy and bleeding, Dempsey picked himself up and walked 40 miles to Delta as the blood dried.

Manassa’s favorite son would rise with that same determination, time and again, in the ring. Dempsey once said, “A champion is someone who gets up when he can’t.”

Unquestionably, Colorado taught him that resolve – and he never forgot the lesson.

by RON J. JACKSON, JR.

THE JACK DEMPSEY MUSEUM – Located in Dempsey’s hometown of Manassa, the museum is dedicated to preserving the legacy of its most famous native son. Visitors will find a collection of original memorabilia from the Dempsey estate, as well as a life-size sculpture, artwork and newspaper clippings that chronicle his rise from obscurity in Colorado to World Heavyweight Champion. Most notably, the collection is housed in the cabin where Dempsey was born June 24, 1895. Open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday through Friday. Admission is free. For more information, call (719) 843-5207.

DURANGO – In this scenic mountain town, visitors will find the famous Durango & Silverton Narrow-Gauge Railroad, whitewater rafting, an abundance of hiking trails and a mural that celebrates Dempsey’s Oct. 7, 1915, fight with Andy Malloy by artist Tom McMurray. The mural captures the moment Dempsey knocked down Malloy for the last time at the Gem Theatre. The mural remains prominently in sight today, located south of the old Gem Theatre and painted on the red brick wall of the El Rancho Tavern.

MONTROSE – The Dempsey family once lived in Montrose, where Jack’s mother opened a ramshackle restaurant. The eatery became a popular hangout for the workers building the Gunnison Tunnel for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. Jack helped his mother in the restaurant, but Montrose is especially noted as the site of two of Dempsey’s earliest fights in 1912. At the time, Dempsey fought under the name, “Kid Blackie.”

Turns out the boxer isn’t the only Jack Dempsey known for throwing his weight around.

Native to Central America, the Jack Dempsey fish (Rocio octofasciata) is a freshwater cichlid with a reputation for being bold, flashy – and downright aggressive when provoked. Aquarium keepers quickly took note of its bad temper and brawler instincts. In the early 20th century, as it entered the aquarium trade, it earned a fitting nickname: Jack Dempsey, after the heavyweight champ who ruled American boxing rings with raw power and unshakable grit.

Like its namesake, the fish is hard to ignore. Its deep, dark coloring shimmers with blues, greens and purples that seem to flare when it’s agitated – or just showing off. And while it won’t break your nose, it has no trouble intimidating other fish in the tank.

Tough. Flashy. Territorial. A fighter by nature.

The name just made sense.

recipes and photographs by

DANELLE McCOLLUM

CRANBERRIES ARE MORE than just a sweet treat. When added to dips, appetizers and side dishes, the berries burst with a bit of pleasantly mouth-puckering flavor. We hope serving this quartet of cranberry recipes becomes tradition, part of the warm memories your loved ones will cherish after gathering around tables this holiday season.

White cream and feta cheeses, green onions and crimson cranberries turn traditional pinwheels into a new holiday tradition

In small bowl, combine cheeses and green onions. Stir in cranberries. Divide mixture evenly between tortillas. Roll up each tortilla tight and wrap in plastic wrap. Refrigerate 1 hour minimum. Slice rolled tortillas into inch-thick slices and serve.

8 oz cream cheese, softened 1/2 cup feta cheese, crumbled 1/2 cup green onions, chopped

5 oz dried cranberries

4 10-inch flour tortillas

Ser ves 4

Ready for a holiday color bonanza? With its cranberry topping – making this cream cheese spread is likely to have loved ones skipping other holiday parties to come to your house. Leave this hot and sweet combo out for the Big Man in Red and who knows what you will find under the tree.

In small saucepan, combine cranberries, brown sugar, orange juice, jalapeno pepper, lemon juice and cinnamon. Bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer 10 minutes or until thickened. Cool completely.

In large bowl, beat cream cheese with electric mixer until light and fluffy. Stir in cranberry mixture and green onion. Refrigerate until serving. Serve with crackers.

3/4 cup dried cranberries, chopped coarse

1/3 cup brown sugar

1/2 cup orange juice

1 small jalapeno pepper, seeded, chopped fine

1 Tbsp lemon juice

1/8 tsp cinnamon

8 oz cream cheese, softened

1 green onion, chopped Crackers

Ser ves 4-6

This culinary creation fusing beef and cranberries is a holiday nod to farmers and ranchers and a gourmet gift to seasonal menus.

Place meatballs in lightly greased slow cooker. In large bowl, combine cranberry sauce, chili sauce, brown sugar, lemon juice and Worcestershire sauce. Pour over meatballs.

Cover and cook on low 4 hours or until sauce bubbles. Sprinkle with green onions before serving, if desired.

2 lbs meatballs

1 14-oz can whole berr y cranberry sauce

1 12-oz bottle chili sauce

1/4 cup brown sugar

1 Tbsp lemon juice

1 Tbsp Worcestershire sauce

Green onions, chopped, for garnish (optional)

Ser ves 4

When jalapeno peppers and dried cranberries combine in this cheesy combo, hiding a second batch in the back of the refrigerator is a good idea for when this colorful dip flies off the shelf.

In medium bowl, combine cranberries, green onion, cilantro, jalapeno pepper, sugar, cumin, lemon juice and salt. Cover and refrigerate 4 hours minimum. When ready to serve, spread cream cheese in even layer on plate or platter. Spread cranberry mixture evenly over cream cheese. Serve with crackers.

12 oz fresh cranberries, chopped

1/4 cup green onion, chopped

1/4 cup fresh cilantro, chopped

1 small jalapeno pepper, seeded, chopped

1¼ cups sugar

1/4 tsp cumin

2 Tbsp lemon juice

Dash salt

16 oz cream cheese, softened Crackers

Ser ves 6

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

Evergreens stand resilient through snow and frost, a quiet defiance of winter. They hold the memory of seasons past while sheltering the promise of spring, their vivid green a beacon against the coldest backdrops. In these poems, we’re reminded of endurance and the steadfast beauty of life itself.

Sandy Morgan, Colorado Springs

I am a transplant, born of prairie dust and fly-away hair; a place where in winter the trees are bare.

So when I moved to the foot of the mountains, began to hike and was introduced to spruce and fir, was courted by ponderosa pine, I felt like Cinderella.

Now, in the midnight of winter when I sit by my fire, a wreath of evergreen above the mantle, I remember my roots but my soul rests in the shelter of the mountains.

Davis Saunders, Monument

Outside it smells like smoke today, And it reminds me of the home That I left far away.

Where fires scorched the mountainside, On which the evergreens had grown Up tall with stately pride,

The smoke would turn the sun to red, As it through mountain shadows shone On pines, now black and dead.

Still, I know the rain will fall, And evergreens, burned dry as bone, Will once again grow tall,

As green as they had been before, As tall as they have ever grown, With stately pride restored.

Outside it smells like smoke today, And like the evergreens back home, I will return to stay.

Hal Sponheim, Loveland

From the dark silhouettes of lodgepoles, While hiking in the pre-dawn light. Their foreboding, ghostly spires Are at once awe- inspiring and induce a fright.

To the peace of the ponderosa forest, With its adjacent mosaic meadows. Beckoning and whispering softly, Ancient stories as the breeze blows.

At treeline, gale-force winds roar And age-old bristlecones thrive. Gnarled, twisted and stripped, Through thousands of years and still alive!

And against the white, winter snow, Blue spruce needles sparkle a silvery, blue sheen. Bringing light and joy to the season, Colorado forever, evergreen.

Steven

Wade Veatch, Kingsley, Michigan

The air, a sharp whisper through the pines, feels thin and crisp here. It’s no gentle, leafy sigh of the east, but a constant calm.

Colorado, green braids your rugged soul, from the foothills where ponderosas stand like sentinels, to the high country, where Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir ascend rock faces, defying gravity, clinging to impossible slopes –as if their roots were the thread holding the mountains in place.

Evergreens skip autumn’s fiery show, offering instead a constant, quiet presence. They’re a steadfast green, even when aspens glow gold, even when the ground’s a blanket of white. Their branches sigh and creak, shedding new snow.

Through blizzards, the harsh bite of frost, and the long, bright days of summer, evergreens stand, a testament to endurance. They are the silent, steadfast anchor in a world of changing seasons, the quiet strength that defines this rugged beauty. Colorado, forever green.

Marina J Ashworth, Denver

Evergreen denotes a foothills town Denotes trees forever verdant Denotes the tree that barks a spice Denotes our state that forever enchants

Evergreen trees endure icy cold Stand aye with grand relevance Shed oldies as new needles are born Smiles as sprigs start their dance

EverGreen, Queen who eternal sows a tune that croons to our soul Enduring Spirit most stout implies Colorado keeps spry our drumroll

Colorado accepts no Medal Gold for gifts timeless, meant to be seen On her throne she smiles to ken All is Evergreen as bid by the Queen

Send Your Poems on the theme “First Thunder” for the March/April 2026 issue, deadline Jan. 1, and “Unfolding” for the May/June 2026 issue, deadline March 1. Email your poems to poetry@coloradolifemagazine.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

DEC. 5-JAN. 1 • COLORADO SPRINGS

Nestled 6,714 feet above sea level on the slopes of Pikes Peak, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo transforms into a glowing wonderland each winter during Electric Safari. The nation’s highest-elevation zoo lights up its 50 acres with 85 handcrafted animal sculptures, colossal inflatable creatures and a dazzling drone show visible from every corner of the grounds.

Visitors can wander past lions, sloths, peacocks and orangutans – some made of light, others very much alive – and even hand-feed giraffes inside their barn.

Steaming cups of hot cocoa are available at stations along the journey, and Santa himself listens to the wishes of nice children at the Safari Lodge from 4-8:30 p.m. nightly through Dec. 23. The animals themselves have a wish list, too – donate food, toys and other requested items at Admissions.

At 7:30 p.m. each night, look to the skies for a 15-minute choreographed drone show. It’s visible from anywhere in the zoo – but for the prime viewing spots, head to Elephant Boardwalk or the Lodge at Moose Lake. Hop on the Sky Ride for an aerial view of the lights – just like the Australian budgies get.

Visitors can enjoy the event with advance timed tickets from Dec. 5-23 and Dec. 25-Jan. 1 (closed Dec. 24). Zoo members get free admission and early entry from 4-5 p.m. General admission is from 5-7:30 p.m. Prices range based on age and visitation during peak nights or non-peak nights, available on the zoo’s website.

From giraffe feedings to sloths glowing, Electric Safari is where all of the wild things twinkle this season. cmzoo.org, (719) 633-9925.

TO EAT THE RABBIT HOLE

Hidden eclectic fine dining awaits underneath Colorado Springs.

Nicknamed the Wonderland of the Springs, the seasonally rotating menu includes duck leg confit with strawberry-rhubarb sauce, crispy risotto cakes and a blackberry ember cocktail. 101 N. Tejon St., (719) 203-5072.

TO

THE CLIFF HOUSE AT PIKES PEAK

At the base of America’s Mountain, this 1800s-era Victorian mansion has 54 rooms with opulent amenities such as spa tubs and towel warmers. 306 Cañon Ave., Manitou Springs, (719) 785-1000.

WHERE TO GO THE BROADMOOR SEVEN FALLS

Walk a paved, 0.8-mile trail to the only waterfall in Colorado on National Geographic’s list of International Waterfalls. There are 224 stairs to the top, while the Eagle’s Nest platform can be reached by elevator. 1045 Lower Gold Camp Rd., (855) 923-7272.

Eighty-five animal sculptures crafted from twinkling lights accompany real zoo animals during the Electric Safari through January at Cheyenne Mountain Zoo.

Once the dust settles from the National Western Stock Show in Denver, professional cowboys and bull riders head north to compete in a snowy rodeo stampede at Steamboat Springs Resort, racing downhill in chaps and hats.

JAN. 19 • STEAMBOAT SPRINGS

Each January, as the National Western Stock Show stirs up dust down in Denver, Steamboat Springs swaps spurs for ski boots in one of winter’s wildest traditions: the Cowboy Downhill. This rollicking rodeo on snow began in 1974 when Billy Kidd, Steamboat’s director of skiing, and Larry Mahan, six-time all-around World Champion cowboy, opened their slopes to ProRodeo competitors.

Now, over 100 of the best professional rodeo cowboys and bull riders from around the country compete in a frenzy of events at Steamboat Resort from 11 a.m.4 p.m. Before the snow-spraying chaos, visitors can party at the base of the resort,

where there’s a 4H animal petting zoo, a learn-to-rope clinic, live music, food, drinks and vendors.

In the first event, cowboys and cowgirls duel slalom down a green run. After navigating tight flags in a series of turns, they must land a jump, lasso a person, saddle a horse and cross the finish line.

Then competitors simultaneously race their way to ultimate glory in an epic stampede – a mass race to the base. The entertaining, chaotic event culminates in some lassoing, lots of jumping and sometimes tumbling – with chaps, cowboy hats and grins as wide as the Yampa Valley. steamboat.com, (970) 879-6111.

WHERE TO EAT BACK DOOR GRILL

Tap into your wild side with the Dirty Harry – a burger topped with peanut butter, bacon, cheese, hashbrowns and an egg sandwiched between glazed donuts. 825 Oak St., (970) 871-7888.

WHERE TO STAY RABBIT EARS MOTEL

Family-owned and operated since 1971, this historic landmark greets guests with its famous neon pink rabbit sign. Your stay also grants discounted admission to nearby Old Town Hot Springs. 201 Lincoln Ave., (970) 879-1150.

WHERE TO GO STRAWBERRY PARK HOT SPRINGS

Soak in the healing mineral waters of geothermal pools along Hot Spring Creek in the Yampa Valley, just 20 minutes from downtown Steamboat Springs. 44200 County Road 36, (970) 879-0342.

Jingle Mingle Gala

Dec. 5 • Cedaredge

Shop, mingle and jingle to live music at Grand Mesa Arts & Events Center. A live auction garners bids, and DaVeto’s Italian Restaurant provides hors d’oeuvres and desserts. Tickets $65 per person. 195 W. Main St., (970) 856-9195.

Chili and Soup Festival

Dec. 6 • Fort Morgan

Ladle endless bowls of soup and chili for just $5 entry during the 15th annual festival at Glen Miller Park, held from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. The event includes cookie decorating, gingerbread houses, hot cocoa, tractor-pulled wagon rides, a choir performance and dance group, a meetand-greet with goats and Santa with his redneck reindeer. 414 Main St.

Fall into Winter Concert Series

Dec. 11 • Delta

The finale of Stoney Mesa’s winter concert series celebrates with Moor and McCumber – classic folk rock meets modern Americana. 7-9 p.m. $95 for Grand Mesa Arts members, $110 for nonmembers. 195 W. Main St., (970) 856-9195.

Goods in the Woods

Dec. 13 • Keystone

Local vendors sell their wares at Warren Station’s annual holiday market. Shop for handcrafted gifts, art and jewelry while enjoying drinks and live music from Risky Strings. 1-5 p.m. 164 Ida Belle Dr., (970) 423-8994.

Gold Camp Christmas Festivities

Dec. 13 • Cripple Creek

Cripple Creek transforms into Christmas City with cocoa, cider and s’mores. Enjoy lunch at 11 a.m. outside Aspen Mine Center, then a festive float parade at noon. Santa visits at 12:30 p.m. and again from 3:30-5, followed by a moving chorale performance at Baptist Church. (719) 270-1999.

1340 Penn After Hours

Dec. 18 • Denver

Cozy up at the Molly Brown House Museum to share nighttime traditions from the time of Margaret Brown – the socialite and Titanic survivor. Sip a warm beverage while listening to tales of winter’s darkest nights. 1340 Pennsylvania St., (303) 832-4092.

Cirque Musica Holiday Wonderland

Dec. 23 • Loveland

World-class performers flip, fly and swing through the air in this cirquemeets-Christmas extravaganza. Show begins at 7:30 p.m. at Blue Arena, home of the Colorado Eagles. 5290 Arena Cir., (970) 619-4111.

The Musicfest at Steamboat

Jan. 5-10 • Steamboat Springs

Celebrate 40 years of the finest Texas and Americana music at Steamboat Resort. More than 50 bands perform on five mountains during six days of skiing and song. 2305 Mt. Werner Cir., (512) 295-3300.

Winter Skate Party and Bonfires

Jan. 16 & 30, Feb. 13 & 27 • South Fork

On select winter evenings, gather at Rickel Park for ice skating and community. Local businesses host a potluck and provide fireside warmth for skaters and spectators alike. A DJ plays tunes while the rink is open Park Dr., (719) 873-5512.

Creede Pond Hockey Tournament

Jan. 17-18 • Creede

Amateur teams from across the U.S. descend on the snowy San Juans for a weekend of spirited pond hockey at the Golden Puck tournament. Creede locals battle for the trophy on frozen Willow Creek drainage ponds as fans cheer them on. (719) 658-2374.

Skis and Saddles Skijor

Jan. 17-18 • Pagosa Springs

Cowboy skiers get their giddy-up on for the annual Pagosa Springs skijor event at Archuleta County Fairgrounds. Riders race through gates, rings and jumps while being pulled by a horse at high speeds. 344 US 84, (307) 272-0253.

Jan. 23-25 • Aspen

Ski, snowboard and snowmobile athletes push the limits with three days of extreme action at the 25th X Games. Events include Superpipe, Big Air, Knuckle Huck and Slopestyle. 38700 Hwy. 82.

Rio Frio Ice Festival

Jan. 24-26 • Alamosa

Celebrate the Rio Grande River, lifeblood of Alamosa and the San Luis Valley. Race the unique Rio Frio 5K across the frozen river at 10 a.m. on Jan. 24. Registration $15. Ice carving and sculptures, bonfires, a Polar Plunge and festival fun to follow. (719) 589-2105.

Questions on pages 12-13

1 Pagosa Springs

2 Sulfur

3 Watsu

4 Glenwood Hot Springs

5 Butch Cassidy

6 b. Mount Princeton Hot Springs

7 a. Routt National Forest

8 b. 93

9 b. Clothing

10 c. 11,200

11 False, it’s more like 140, maximum.

12 True

13 True, though it gets a bad rep, in trace amounts it may even provide a few health benefits!

14 True

15 False, there’s no extra radioactivity there. Radium was once mined nearby, but it’s perfectly safe to swim.

Trivia Photographs

Page 12, Top Pagosa Springs

Page 12, Bottom Sulphur crystals

Page 13, Strawberry Hot Springs

of this organization and the exempt status for federal income tax purposes: Has not changed during preceding 12 months. (13.) Publication Title: Colorado Life Magazine (14.) Issue Date for Circulation Data Below: Nov/Dec 2024-Sept/Oct 2025. (15.) Extent and nature of circulation: First column: Average no. copies each issue during preceding 12 months. Second column: Actual no. copies of single issue published nearest to filing date.

A. Total no. copies (net press run)

B. Paid and/or requested circulation

1. Paid/requested outside-county mail subscriptions.

2. Paid in-county subscriptions.

3. Sales through dealers and carriers, street vendors and counter sales.

4. Other classes mailed through USPS

C. Total paid and/or requested circulation (sum of 15b. 1, 2, 3 and 4)

D. Free distribution by mail, carrier or other means, samples, complimentary, and other free copies.

1. Free distribution outside county.

E. Total free distribution.

F. Total distribution (Sum of C and E).

G. Copies not distributed.

H. Total sum of F and G.

I. Percent paid and/or requested circulation (15c. divided by 15f. times 100). (16.)

A. Paid electronic copies

B. Total paid print copies (15c.) plus paid electronic copies (16a.)

C. Total print distribution (15f.) plus paid electronic copies (16a.)

D. Percent paid both print and electronic copies (16b.) divided by 16c .times 100).

(17.) I certify that the statements made by me above are correct and complete. Angela Amundson Associate Publisher

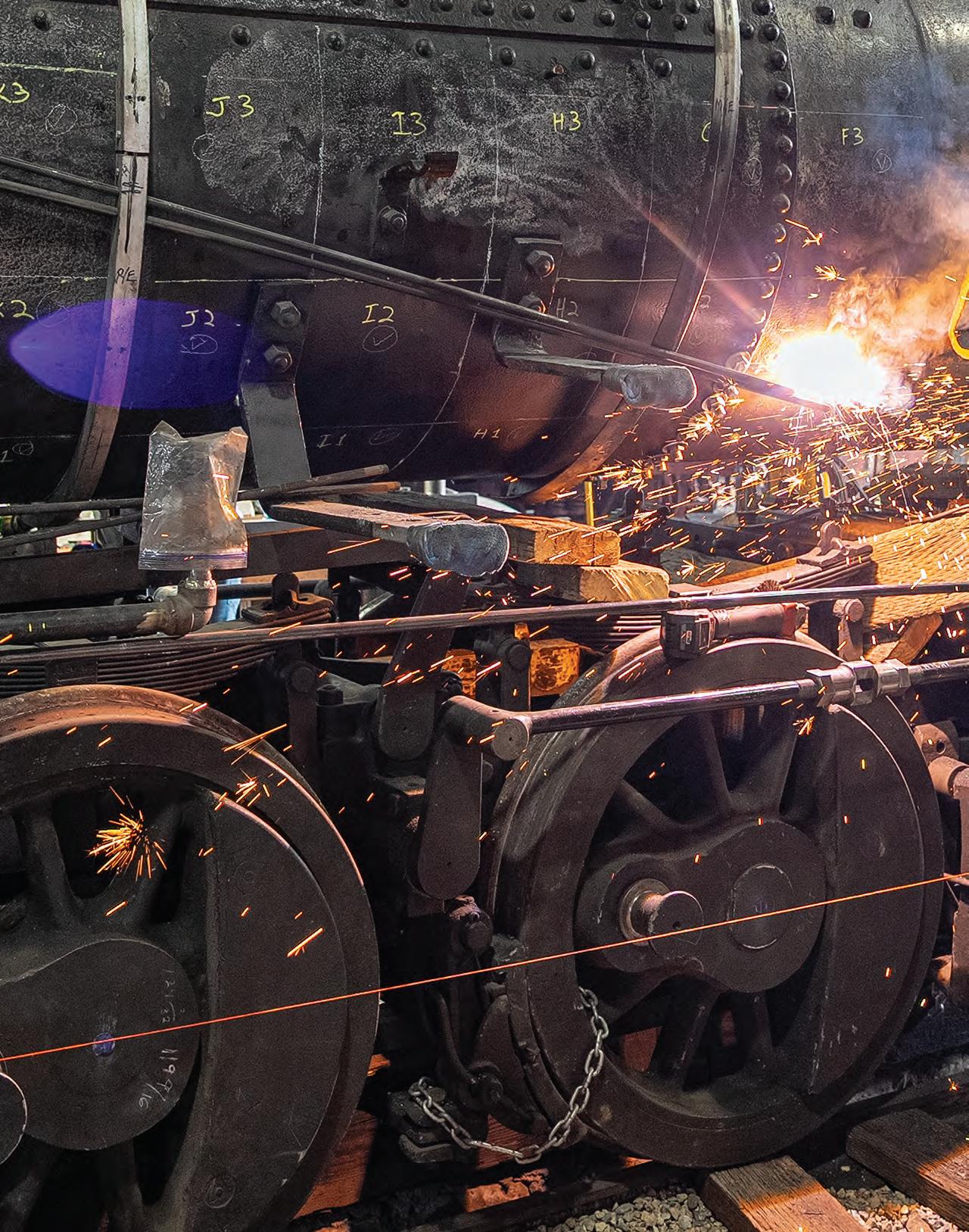

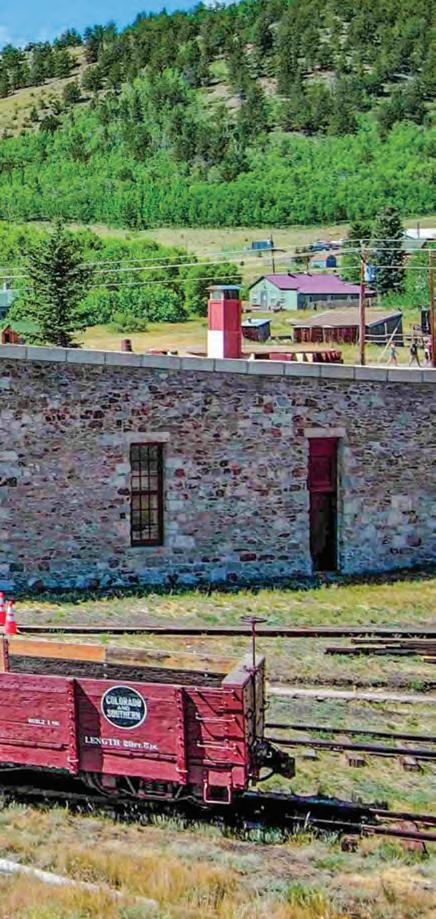

Volunteers breathe new life into Como’s 1881 roundhouse – and into Colorado’s railroading legacy.

AHAMMER RANG against steel, echoing through the high stone bays of the Como Roundhouse. The air was thin and carried the scent of oil and coal dust. Morning light cut through tall windows as volunteers moved between tools and timber, their voices rising softly beneath the curved roof. The roundhouse hummed with more life than it had seen in generations.

Every other weekend, a shifting crew of men and women from across the Front Range gathered here to restore what history nearly erased. Steve Thompson, a retired Navy pilot and now president of the South Park Rail Society, watched the bustle with quiet pride. “They’re just interested in railroads and Colorado heritage,” he said. “It’s an eclectic group and that’s what makes it fun.”

The Como Roundhouse was built in 1881 by Italian stonemasons and housed 19 stalls which serviced approximately 25 trains per day. The central round table was engineered to be perfectly balanced so that a single person could spin a train engine to any of the attached tracks.

Como sits 75 miles southwest of Denver, tucked against the eastern base of the Mosquito Range in a broad mountain valley once crisscrossed by narrow-gauge tracks. Once home to several hundred residents in its railroad heyday, the town now counts only a few dozen year-round inhabitants. In the late 1800s this remote outpost linked the mines of Breckenridge, Leadville and Gunnison to the capital.

Trains bound for Breckenridge climbed over Boreas Pass, the 11,493-foot summit that ranked among the highest and most difficult railroad crossings in North America. At 9,800 feet, the town of Como served as the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad’s division point – a place where locomotives were turned, serviced and sent back into the peaks. From its beginnings,

the town grew around the roundhouse itself – a structure built to keep trains and people moving through the high country.

Built in 1881 by Italian stonemasons using local granite, the roundhouse originally held six stalls that later grew to 19. In its prime, about 25 trains a day steamed in and out of Como. A roundhouse like this functioned as a semicircular workshop centered on a turntable that swung locomotives from one bay to another.

Then the whistles faded. When silver prices collapsed in 1893, South Park’s mining traffic slowed to a crawl. By 1910, trains were scarce; by April 1937, the last passenger run was documented through Como. Crews soon tore up the rails for scrap. Across the wide basin, the silence of the mines spread quickly and even South Park itself seemed to exhale and wait.

Wind replaced the sound of steam and the valley held its breath for half a century.

, the Como Roundhouse was already marked for demolition when Bill Kazel, a precious metals miner from Idaho Springs, stepped in. Park County had posted warning signs by the time he bought the property in 1984 – the roof sagged, windows gaped, and half the bays lay open to the weather. With help from a bearded stonemason – “a former Hell’s Angel who looked like ZZ Top,” one volunteer recalled – Kazel rebuilt the roof and reset every stone by hand, saving the roundhouse from collapse.

When Chuck and Kathy Brantigan of Denver bought the property in 2001, they became its next stewards. “Our intention was just to preserve it and make sure noth-

ing bad happened to it,” Kathy said. She credited Tom Lawson, the South Park Rail Society’s tireless vice president, for channeling donations and volunteers. “He’s an Energizer Bunny,” she said, with a laugh.

Today, two intertwined nonprofits – the South Park Rail Society and the Denver South Park & Pacific Historical Society –share responsibility for keeping Como’s legacy alive. Their signature project is the restoration of a steam locomotive affectionately known as Klondike Kate.

Built in 1912 by Baldwin Locomotive Works, the 2-6-2 narrow-gauge engine once hauled ore in Yukon Territory before returning to Colorado. After blowing a cylinder in 2021, she became the heart of the roundhouse revival. Volunteers led by Dan Silbaugh – a commercial pilot and former aircraft mechanic from Dumont –

The Como Roundhouse and Depot are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In its heyday, the railroad hub connected mines in Breckenridge, Leadville and Gunnison over Boreas Pass – one of the highest and most difficult railroad crossings in North America.

logged thousands of hours rebuilding her with help from welders at the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad.

“The project is right up my alley,” Silbaugh said. “Parts are no longer coming off – they’re going on.” Around him, the clang of metal rang through the stone bays as two volunteers hand-cranked a reamer, boring holes just as their predecessors did in 1898. Oil and steel scented the cold air.

Klondike Kate’s arrival in 2017 drew more than 100 onlookers as flatbeds eased her into South Park. Volunteers laid half a mile of new track by hand in time for Boreas Pass Railroad Day that August. For the first time in 80 years, steam filled the roundhouse again.

“Our greatest resource here is volun-

teers,” Thompson said. “People call us up: ‘You want a milling machine?’ We’ll come get it.” The Denver South Park & Pacific Historical Society has grown from a dozen members in 1999 to more than 300 today. Many are retirees, but new faces arrive each summer – students, machinists, history buffs – all drawn by the chance to keep something tangible turning.

“The Como Heritage Project is an incredible grass roots success story that bears witness to railroad life in the Rockies when Colorado was just getting started. Future generations will now be able to fully share in that experience,” Thompson said.

Beyond ongoing maintenance, plans call for whitewashed walls, new wood flooring and three reconstructed stalls matching the

originals. Long-term, the group intends to extend track across Park Gulch and reconstruct the King Wye to enable trains to turn around. A $250,000 grant application with History Colorado is pending and matching funds are nearly secured.

The effort sits within the South Park National Heritage Area, one of only three such regions in Colorado. Here, railroads, ranching and mining shaped a landscape still defined by open space and persistence. Standing in the roundhouse doorway, Thompson gestured toward the horizon. “Let’s be honest,” he said. “This stuff wasn’t built to last this long.” Yet the walls held.

Luke Miller, a 19-year-old Colorado State University student, represents the next generation. His fascination with

model trains eventually drew him to the real thing. He now drives up from the Front Range several weekends each summer to help restore Klondike Kate, proud to see the century-old locomotive taking shape under his hands.

As daylight faded across South Park, the Mosquito Range cast long shadows over the rails. The valley that once roared with engines now listened to the rhythm of restoration –steel on stone, wind through open doors, the echo of work that refused to end.

The South Park Rail Society welcomes visitors and hosts open houses on the third Saturday of each summer month; the third Saturday in August (Aug. 15, 2026) is Boreas Pass Railroad Day. Visit www.southparkrailsociety.org for details.

More than 300 volunteers assist the Denver South Park & Pacific Historical Society, in tandem with the South Park Rail Society, to restore the roundhouse and railyard. Students, machinists and history buffs come together to restore Klondike Kate, a century-old locomotive, as well as lay track and help with ongoing maintenance. On the locomotive itself, welders attach a steel plate to the bottom of the steam chamber and create custom-made rods and bolts for the train’s wheels – a tedious work of craftsmanship.

among Colorado’s

by DAN LEETH

LOCATION

Along Colorado Highway 14 between Walden and Cameron Pass

TENT RV/SITES

Both

ACTIVITIES

Camping, hiking, biking, fishing, wildlife viewing, snowshoeing

HOOVES SOFTLY CLOMPED through the snow outside. Donning jackets, my wife and I opened the door of our backcountry yurt and quietly gazed down from its wooden deck. In the snow-covered clearing beyond, a pair of moose cows rummaged for sustenance beneath a blanket of white. Powdery snow frosted their foraging snouts.

That winter encounter with moose decades ago marked our first camping adventure in Colorado State Forest State Park. This oddly named enclave in the Medicine Bow Mountains began in 1938 with a 70,980-acre land exchange between the U.S. Forest Service and the Colorado State Board of Land Commissioners. The mission was to “provide for and extend

the practice of … forestry.” In 1971, Colorado State Parks began managing recreation here. Today, in addition to hunting, grazing and timber harvesting, Colorado’s largest state park offers outstanding camping, hiking, mountain biking and fishing opportunities.

My wife and I have returned many times, sometimes camping in the park’s developed campgrounds and other times booking remote stays in one of the secluded yurts. Managed by a park concessionaire, these cupcake-shaped shelters feature bunk beds, a dining table and kitchen counters stocked with pots, pans, dishes, utensils, percolators and electric cooktops. Heat comes from wood-burning stoves –best stoked when anyone waking at midnight tosses on another log.

While yurts remain open year-round, we generally tow our own lodging in the summer. State Forest State Park offers 244 campsites, 15 cabins and one group site scattered among five campgrounds. Anglers favor Ranger Lakes Campground, where 31

electric hookup sites sit beside trout-filled ponds. For those preferring full hookups, there’s the North Park Campground on the western edge of the park. Until a few years ago, it was a KOA, its signature A-frame office still standing, though in need of paint. Deer are common visitors, but moose sometimes wander through, too.

Not native to this region, moose were introduced here in 1978 when wildlife officials released a dozen animals, followed by two dozen more later. Lacking predators, they thrived – roughly 600 now inhabit the park. Since our first encounter, spotting these majestic mammals up close has become our goal when camping here.

With 90 miles of hiking and 130 miles of biking trails, State Forest State Park offers plenty of opportunity to see North America’s second-largest mammal in the wild. A volunteer at the Moose Visitor

Center suggested we hike the Gould Loop Trail, a six-mile path between the visitor center and Ranger Lakes Campground. It circles a willow-choked meadow along the Michigan River. Since moose crave willows like my wife craves chocolate, we expected success. The hike was pleasant, but the only moose we found was the seven-foot-tall barbed-wire sculpture outside the visitor center.

Perusing the park map later, I noticed a “Moose Overlook” marked on County Road 41. Figuring it would be false advertising if none appeared, we drove the graded roadway past North Michigan Reservoir and into the forest and meadows beyond. We reached the overlook and gazed outward. Nary a moose graced the view, but we couldn’t argue that the overlook was inappropriately named. Apparently, Moose Overlook’s moniker simply honors its

At Colorado’s State Forest State Park near Walden, visitors can enjoy camping opportunities year-round in backcountry yurts. The park is also home to roughly 600 moose, North America’s second-largest mammal, which thrive on the park’s secluded willowy meadows.

builder – Moose Lodge 275 from Fort Collins. As we motored back, my eagle-eyed spouse spotted movement in a distant meadow. Through binoculars, we watched a bull moose and his companion dine on willows a quarter mile away.

We’d finally found moose in the wild, but my honey wasn’t satisfied.

“I want to see them up close like before,” she complained. “Let’s book that yurt again this winter.”

I pointed out that our sighting years ago was just a random fluke, with no guarantees that we’d ever encounter moose there again, but of course, that didn’t matter. Instead of warm camping somewhere in the desert this winter, it appears we’ll be enjoying another sub-zero campout, once again bunking in a yurt.

I scanned my calendar for available dates.

Colorado State Forest State Park reservations (800-244-5613), cpwshop. com) open six months in advance. Fees range from $41 for full-hookup sites to $18 for primitive tent sites, plus a $12 daily entry fee for those without a Keep Colorado Wild Pass or other valid state park pass.

Reservations for any of the park’s eight yurts are made through Yonder Yurts (970-819-8768, yonderyurts.com). Rates run $175-225 per night and most sleep six to nine guests. Most require a short hike – or snowshoe trek in winter – for access. Guests must bring bedding, water and trash bags. Vault toilet outhouses, which can be a bit nippy in winter, stand a few steps from each yurt. Dogs are not allowed in winter.