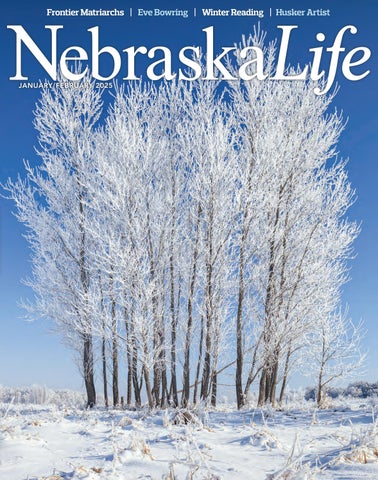

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

Cornhusker State on Canvas, pg. 26

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

Cornhusker State on Canvas, pg. 26

20 Winter Reading Roundup

Nebraska Life’s picks of recent books will fill your winter hours with heartwarming stories, tales of perseverance and architectural wonders. by Lisa Truesdale and Ariella Nardizzi

26 Cornhusker State on Canvas

Ashley Spitsnogle memorializes the Husker’s 400th sellout game at Memorial Stadium, one of many live paintings from the Elkhorn artist. by Ariella Nardizzi

32 Frontier Matriarchs

Many took advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862 to claim land in the Nebraska Territory, but few were owned by women who overcame societal barriers to become pioneers of the Great Plains. by Ariella Nardizzi

38 Following the Eve Bowring Trail

Sandhills ranch shines on with treasures and shadows of Nebraska’s pioneering first female U.S. senator. story by Matthew Spencer photographs by Chris Amundson

Merriman pg. 38

Hyannis pg. 32

Mullen pg. 54

Walworth pg. 32

O’Neill pg. 54

Albion pg. 12

Scribner pg. 12

Omaha pg. 62

Grand Island pg. 12

Lincoln pg. 26

Unadilla pg. 54

McCook pg. 12

10 Mailbox

Letters, emails, posts and notes from our readers.

12 Flat Water News

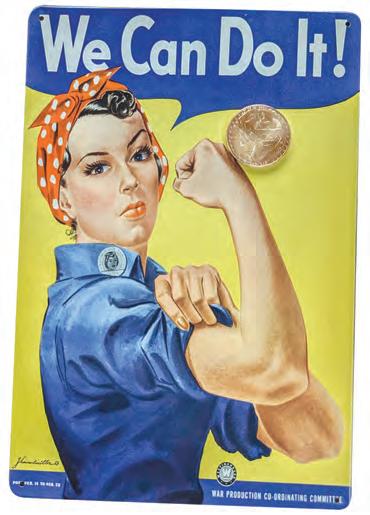

McCook’s own ‘Rosie the Riveter’ receives a Congressional Gold Medal; Nebraska writer reflects on small town life; Scribner’s local grocery store since 1955 reopens in January.

16 Trivia

Celebrate Nebraska with the State Flag. Answers on page 57.

18 Storyteller

A Nebraska Life reader tells of her mother’s German grit living on a farm west of Fairbury. Learn how you can be published, too.

46 Museums

Big or small, these museums preserve Nebraska history and heritage for all to experience.

48 Kitchens

Simple flavors can make for the best sweet treats. Take vanilla out from your pantry and try these vanilla bean recipes.

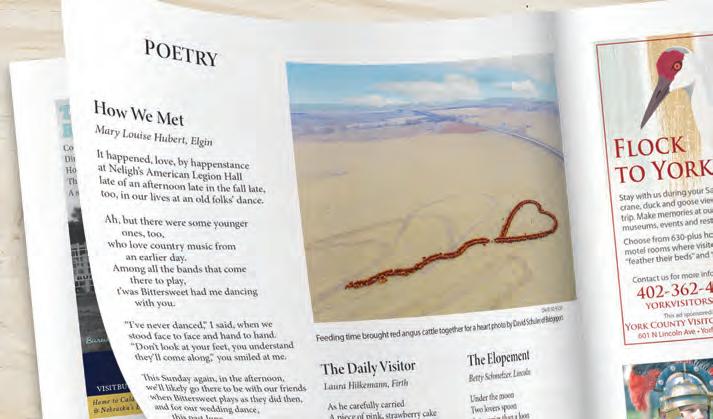

52 Poetry

Our poets preserve cherished memories with loved ones, sharing moments that nourish the heart and spirit.

54 Traveler

Unadilla celebrates Groundhog Day; Wagon riders adorn costumes down the Middle Loup River in Mullen; O’Neill doubles in size for the four-day St. Patrick’s Day celebration.

60 Naturally Nebraska

Alan J. Bartels finds reprieve in a small corner of the Sandhills.

72 Last Look

Photographer Jayson Alder captures Omaha’s Lake Flanagan on a frozen, wind-whipped January morning.

ON OUR COVER

Hoarfrost covers a stand of cottonwoods, the state tree, at Chalco Hills Recreation Area near Chalco on a cold February morning.

BY

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

Volume 29, Number 1

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher Angela Amundson

Managing Editor Lauren Warring

Assigning Editor Victoria Finlayson

Design Jennifer Stevens, Mark Del Rosario

Staff Writer Ariella Nardizzi

Photography Coordinator

Erik Makić

Advertising Sales Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Liesl Amundson, Janice Sudbeck, Anne Canto, Julian Amundson

Nebraska Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130 Fort Collins, CO 80527 1-800-777-6159 NebraskaLife.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit NebraskaLife.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@nebraskalife.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@nebraskalife.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@nebraskalife.com, or visiting NebraskaLife.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@nebraskalife.com.

The editors owe a big thank-you – and a heartfelt correction – to Nancy Galloway Hamar for her letter “Kindness through blizzard” in the September/October 2024 Mailbox section. Now a proud resident of Pleasant Hill, Missouri, Nancy cherishes her Nebraska roots, with family ties to the Sandhills through her father, Jack Galloway. That’s Galloway, not Halloway – our editorial blizzard blew in the wrong name. We’re grateful for Nancy’s graciousness and her Nebraska spirit that shines, no matter the weather.

The “Schoolhouse Fire” article (Storyteller) in the November/December 2024 issue produced my memories from the 1930s, attending a different school in Madison County.

Our school also was a one-room school. Since my dad went to the same school 30 years prior, this story relates to him. From that era, he shared an incident that could have burned down the school.

One day, in 1907, everything was in order for the bi-annual visit of the county school superintendent. After her arrival, one of the older boys tossed some paper in the coal burning stove. Instantly, there was a loud explosion! The 10-foot stove pipe was on the floor – smoke, soot and dust filled the room.

The superintendent fainted. The younger students were crying. Chaos prevailed, and the older student tried to look innocent.

As the teacher regained control, she asked the culprit, “What did you put in the stove?”

His answer: “A little krut” (gunpowder in Swedish).

Gratefully, the school did not burn to the ground.

After reading the magazine, I felt compelled to contribute this story. Your magazine enriches my life every time upon arrival.

Lowell Broberg Puyallup, Washington

Your deadline for poetry submissions for the January/February 2025 issue is Nov. 15, which, as it happens, is my 78th birthday. Enclosed is my poem for your consideration.

Twenty years ago, my first poem ever published appeared in Nebraska Life under my previous name, Mary Avidano. After being a widow for five years, I married again, and my new husband likes to call

me Mary Louise. You accepted a poem for your January/February 2024 issue that tells how Bill and I met (“How We Met”). Why all this personal stuff? Because all through the years, your magazine has encouraged the writing and sharing of poetry, not just my writing, but that of so many others. It is appreciated.

Mary Louise Hubert Elgin

Send your letters and emails by Feb. 1, 2025, for possible publication in the next issue. One lucky winner selected at random will receive a free 1-year subscription renewal. This issue’s winner is Betty Schmelzer of Lincoln. Email editor@nebraskalife.com or write by mail to the address at the front of this magazine. Thanks for reading and subscribing!

Smiles for goats and Holsteins

I love the magazine and have subscribed for many years. In the September/October 2024 issue, the amusing story “The Goat Fence That Never Ends” made me laugh because no Arthur County Sandhills rancher to my knowledge would have a herd of Holstein cows and a Jersey bull unless this was a dairy operation. The photo of cows drinking from a tank does not have a single Holstein cow that I can identify.

The pictures are charming, especially of Fletcher holding a goat. As a child I played with goats, and they are fun.

Betty Schmelzer Lincoln

Blizzard upon blizzard

I was born and raised in Cedar County Nebraska in 1938 – so I was 10 years old when the momentous winter of 1948-49 occurred (Storyteller, January/February 2024; Mailbox, September/October 2024). It was not a blizzard – it was a whole series of blizzards. It started on Nov. 18, 1948, and continued until late March.

We lived 9 miles from town. My mother was in Hartington on Nov. 17, and she

wanted to get to town by her birthday on April 3 – but she didn’t make it until April 12. We walked over telephone lines, and we had tunnels in the snow to a couple of our farm buildings. Thousands of pheasants and quail died of starvation because all their food was buried deep under the snow.

Alan H. Domina Lincoln

BY RON JACKSON

If Phyllis Coolidge had any doubts about the dangers of her job during World War II, all doubts vanished May 26, 1945. On that date, an explosion rocked the Cornhusker Ordinance Plant in Grand Island where she worked, leveling a building and killing nine people.

Coolidge felt the explosion downtown while sitting in a movie theatre with her mother.

“The whole theatre shook,” recalled Coolidge, now 102 and living in McCook. “I knew then something terrible had happened.”

Still, Coolidge harkens back at her wartime job on the plant’s assembly line, building 90-pound bombs, with great humility. The plant operated around the clock, churning out bombs of various sizes, including some as large as 2,000 pounds.

“We just wanted to do our part,” she said matter-of-factly. “We wanted to do it for our country. We were at war, and back then, we were in a bad mess.”

Thanks to Coolidge and some six million other real-life “Rosie the Riveters,” their efforts proved monumental for the victorious Allied Forces. In April, all six million of those selfless women received the nation’s highest civilian honor from Congress – the Congressional Gold Medal. U.S. Representative Adrian Smith, presented Coolidge with her gold medal at an August ceremony, surrounded by family and friends in McCook.

“When I heard I was being honored with a Congressional Gold Medal, I was flabbergasted,” Coolidge said. “You know, I never talked about it. Most of my friends didn’t even know. To me, it was just a job – a way to do my part during the war.”

Coolidge decided to join the war effort in May of 1942 at the age of 20. She

broke the news to her 59-year-old mother, Minnie Hammer, after the death of her father, Lewis. He died after a battle with stomach cancer.

“Nebraska opened (four) ammunition plants, and I knew they would need workers,” Coolidge recalled. “The only men they could hire were those that had one arm or one leg or one eye. All the able-bodied men were already gone in the service. I told my mother I was going to work at the plant in Grand Island. I said, ‘I’m going. If you want to, you can join me.’

“It took her two seconds to say yes.”

Both Phyllis and Minnie traveled from Elmwood to Grand Island, signed on at the plant, and lived in a dormitory for single women for the duration of the war. Each day they donned protective gear and worked on Line Three, where they helped

assemble 90-pound bombs that were later loaded on pallets and shipped out.

“Mom greatly enjoyed the experience,” Coolidge said. “She had never worked a day in her life, away from our ranch. In fact, she didn’t even have a Social Security card at the time. We had to get her one.”

For the next three years, Coolidge noted the importance of those trips to the downtown movie theatre in Grand Island.

“We really went to the theatre as much for the news reels as anything else,” Coolidge said. “Back then, that was our only real way to learn about what was happening in the war. It wasn’t like today where you can get information almost instantly from anywhere in the world. So that was always important.”

As important as women like Coolidge.

BY ROB MILLS

The first time I saw Nebraska was a quarter-century ago.

Driving I-80 from east to west, from Lincoln to the Wyoming border, on my way to a new job in Casper, Wyoming, I was struck by how immense the sky seemed the farther west I traveled. I’ll never forget the sight of the North Platte River, brimming with fresh, flowing water, keeping me company with a majestic presence.

Several years later, I found myself in Kimball, managing an AM radio station. I bought some excellent beef there, explored bluff country on weekly drives to Scottsbluff, and witnessed the momentous (for the area) opening of the Walmart Supercenter in Sidney. Long football playby-play trips to McCook and Imperial are still etched in my memory.

I also spent an entire day in a field near Ogallala, playing the role of engineer, measuring off whatever my broadcasting bosses needed for a new tower. That warm late winter day, in an open field with no sign of humanity, left an impression as vivid as my encounter with the North Platte River.

After leaving Nebraska in 2003, I found

over the years that if I encountered something about Nebraska: a book, a calendar picture, or a Husker game on the tube, it set something off inside of me. I found over the years I’d developed a real fondness for the place. As I would tell potential employers in my cover letters, I’d fallen a little in love with Nebraska.

My opportunity to return came in late summer 2024, when a publisher in Albion reached out about a reporting job. Earlier that year, I’d seen an online ‘for sale’ ad for a paper in Albion, featuring a picture of the building’s William Jennings Bryan-era bay windows. When I arrived in late October, I ended up living there for six weeks, stepping in to help the publisher, who was hospitalized for several weeks just two days after I arrived.

During my time in Albion, I worked alongside a past president of the Nebraska Press Association to keep the paper running. The experience allowed me to immerse myself in a small town with a vibrant pulse.

Albion had a great affordable motel, a sports bar and restaurant, a microbrewery, a cozy coffee shop and a bakery with warm rolls fresh off the shelf. And the beef? Outstanding. It also boasted

the most affordable movie theater in the U.S., managed by the local high school entrepreneurship class. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

While there I had an eventful night in Spalding, covering my first high school football game in two decades. There were more people there than are listed on the city limits population sign. The concession stand sold one-story hamburgers. The grill smoke covered the field like Candlestick Park fog. It was a hoot.

As the New Year begins, here’s my advice to anyone who hasn’t been to Nebraska or hasn’t been back in a while: It’s worth the trip. The merchants will appreciate your business, and the vibe you’ll encounter will recharge your soul. You might even find yourself coming back again and again – or uprooting your life to settle there for good.

And as time passes, when you reflect on your journey, I bet you’ll find yourself having fallen a little bit in love with Nebraska, too.

About the author: Rob Mills is a freelance writer published in Albion News and Petersburg Press. He has been in media for 40 years, previously in radio news.

BY KRISTIN DAHL

Joe Wolfgram never set out to own a business, let alone two. As he prepares to reopen Lee’s Market, he’s stepping into an inheritance that’s been the heart of Scribner for nearly 70 years.

Since 1955, Lee’s Market on Main Street has been a cornerstone of Scribner, a place where generations have shopped, met neighbors and shared stories. Beloved owner Lee Burkink, Jr. died in 2021, leaving ownership to his son, JB.

“Lee was a giant in this town,” Joe said. “He wasn’t just the owner of the store. He was the guy who made everyone feel welcome. He was the one who knew your name, your kids’ names, and where you were headed on Saturday. That’s a big act to follow.”

Joe Wolfgram is the new owner of Lee’s Market in Scribner and will carry on the store’s 70-year history.

In 2023, JB died. Though deeply invested in the store, the family decided to sell.

For 18 years, Joe worked for the government, far removed from small-town life. Mel’s Bar, Scribner’s neighborhood watering hole, first pulled Joe into the world of business ownership. “That decision turned into something I never expected, and now, I’m doing it again,” he said.

When Joe took over as the new owner of Lee’s Market in November, he inherited more than just a business – he inherited a legacy. Lee’s Market has been more than just a grocery store; it’s a staple in Scribner.

“Lee’s Market is a place of connection,” Mayor Ken Thomas said. “It’s been here for so long, and it’s a place where people could always count on seeing familiar faces. Now, Joe can carry that torch, and we have faith he’ll do it well.”

For Joe, the task is clear: honor Lee’s legacy while modernizing the store to meet today’s needs. His goal is to keep Lee’s Market as a place where people gather, not just for groceries but for connection.

“The people here are what make this place special,” Joe said. “I want to make sure that Lee’s Market remains a hub for the community, a place where you don’t just shop – you catch up with your neighbors.”

Joe is excited about the future but also deeply mindful of the past. “This is about more than running a store,” he said. “It’s about keeping a piece of Scribner alive for the next generation.”

As Joe walks the same aisles Lee once did, he knows the road ahead won’t be without its challenges. He’s ready to honor Lee’s legacy and write the next chapter in Scribner’s story.

Cottonwood Shine

NEBRASKA ARTIST Beth Cole

See 2025 Workshops and Events at BethColeArt.com

Commissions opening in January

Test your knowledge of our emblematic ensign. Questions by ARIELLA NARDIZZI and CHRIS AMUNDSON

1

In 1867, the year of Nebraska Statehood, Isaac Wiles – a farmer from Plattsmouth and a member of the Nebraska House of Representatives – created the state motto, “Equity Before the Law,” and what else, both used on the state flag?

2

Influencing the wording of the state motto, what significant change to the Nebraska constitution did U.S. Congress demand before it would allow Nebraska to become a state?

3

The state flag became official in 1963, but its design was originally adopted in 1925 as what lower designation that is often used to promote events.

4 What geographic landmark depicted on the state flag is not actually in Nebraska?

5 The flag’s field, or background, features the same blue used in what other well-known flag?

6 The flag shows modes of transportation vital to Nebraskan settlers’ westward expansion and mobility in the 19th century. Which method of transportation was not included?

a. Steamboat

b. Covered wagon

c. Train

7 The seal’s gold accent symbolizes Nebraska’s abundance of what?

a. Gold nuggets

b. Corn and wheat

c. Prosperity and wealth

8 Crops surround a settler’s cabin in the foreground to represent the state’s agricultural roots. Which of these crops is not depicted?

a. Soybeans

b. Corn

c. Wheat

9 What historical preservation organization was instrumental in advocating for the creation of the state flag?

a. Nebraska State Historical Society

b. Daughters of the America Revolution

c. Nebraska State Genealogical Society

10 What river is depicted on the flag?

a. Platte River

b. Republican River

c. Missouri River

Check out our progress and additional spaces on AirBNB!

11

The state flag can be printed on clothing and other consumer goods.

12

In 1925, Nebraska became the last of the 48 continental states to designate a state flag.

13

The first flag was manufactured in Mason City, Nebraska.

14

On the west side of the State Capitol in 2017, the flag was flown upside down for 10 days before someone noticed. This prompted discussions about redesigning it – efforts that were successful.

15

The blacksmith at the center of the flag symbolizes the state’s position as a leading manufacturer of horseshoes.

Set amidst the quiet, small town of York, each light-filled guest room has a private bath and comfortable furnishings. A personal lodging experience tailored just for you.

Book your stay today!

story by JANICE LLOYD

SHE WAS MY mom – Mavis Pleis and later, Mavis Lloyd. She was the oldest of seven children born on my grandparents’ farm west of Fairbury. They attended the Zion United Church in Gladstone, and visiting that cemetery is like a family reunion.

The family farm was a dynasty of sorts, overseen by the family patriarch, mom’s strict German grandfather. Mom used to describe her grandfather coming down the long driveway in his horse and buggy. He would criticize and demand improvements for each family’s farm. She and her siblings were so afraid of him, they would run and hide.

Being the oldest, Mavis was her father’s “boy,” which meant she worked beside him in the fields and whatever else he needed doing.

Mavis had just finished eighth grade at the little country schoolhouse when her father announced that Mavis would not be going into Fairbury to attend high school. He needed her help year-round full-time. My grandmother totally opposed grandpa’s decision. The children were sent to bed, but my mother heard loud arguing downstairs for hours, mostly in German.

My mom pondered her fate all that summer. Then one day in late August, her mother took down the sugar bowl where she kept a few dollar bills, which she gave to Mavis, and told her that she would be going into town to live with Aunt Toots and attend Fairbury High School.

Mom graduated in 1934 with a Normal Training Certificate, entitling her to teach. She was 17 when she began teach-

ing in a small country schoolhouse west of Fairbury and Gladstone. She told us stories about those times, including the day the students discovered a mouse nest, and she turned it into a science project. Or the day one of her little girl students came running in, breathless and excited, to tell them all that she had a new baby sister. Her mother bent over to take bread from the oven, a baby just popped out, she exclaimed. My mom said that was a very tricky moment, shielding questions and changing the subject quickly.

My mom bought a car in 1935. Her father wouldn’t allow her to drive it, keeping it at the farm and transporting her to and from her schoolhouse. In a surprising act of rebellion, she and her girlfriends hatched a plan. It was late when they sneaked into the barn and quietly pushed that old car out and down the driveway to the main road. They picked up a few more friends and headed for the nearest dance hall. They had a great night, but one girl took off with a boyfriend. They managed to get the car back home into the barn but unfortunately that one girl never returned to her home that night. The cat was out of the bag. There were no more late-night shenanigans.

Mom married a business owner in town and began some memorable years as a housewife and mother to four of us – three girls and a boy. She no longer taught school but seemed to tackle every aspect of home life with incredible verve, including a huge garden (which she worked on at 4 a.m.), canned tons of food, sewed lovely (matching) dresses

for the three of us girls, kept our hair in perfect ringlets, starched every curtain and even ironed the sheets. She seldom walked; I mostly remember her half-trotting or even running from one task to another in those days.

She became president of our West Ward School’s PTA and initiated a “Fun Night” which was a very popular money-maker for years. Then my parents divorced.

The only thing my mom said she knew how to do was teach. I remember the day Mom graduated from Fairbury’s Junior College. The ceremony was held in upper McNish Park. My sister Livia and I sat on our bikes at the edge of the trees, proudly saw our mother, in her cap and gown, march forward to receive her very well-deserved diploma.

Requirements for teaching were now demanding a four-year degree. So, Mother decided we had to relocate. We moved to New York to be near her brother and his family. Mom managed to obtain a fulltime, permanent substitute position while she continued her college work, obtaining a Bachelor of Science degree from Hofstra College. She retired at 62 and moved to Florida, where she had quiet years of rest and contentment.

There is such a thing as “German Grit,” and my mom personified it. Her life wasn’t easy, but she didn’t complain. She took responsibility. She gave us all she could, and then some more. Devotion to family, values of hard work and perseverance, the importance of an education, are all part of her story... and those Nebraska roots. They run deep.

Six books weave together Nebraska’s history and people

As the winter months settle across the state, Nebraskans gear up for ice fishing in Valentine, water tanking on the Middle Loup River or watching bald eagles at the Indian Cave State Park. Between outdoor adventures and family meals, Nebraskans can curl up at home with a hot chocolate or apple cider with a copy of Nebraska Life and a good book. Here are six books to add to your winter reading lists.

by LISA TRUESDALE

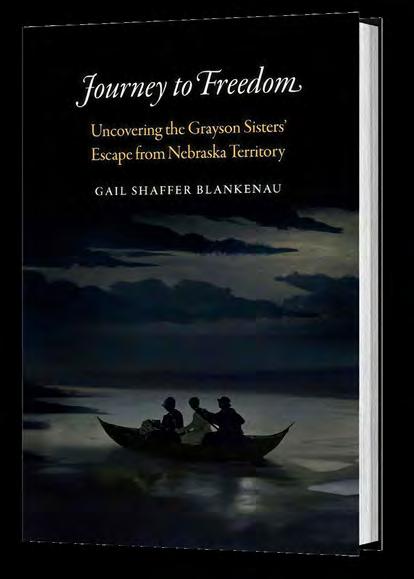

ON A FRIGID, late-November night in 1858, Celia and Eliza Grayson, ages 22 and 20, quietly slipped out of their home in the frontier river town of Nebraska City. Just one rustle of clothing or a creaky floorboard would have meant capture and severe punishment, or worse. They met up with John Williamson, a Black and Cherokee man who had offered to help them escape from Stephen F. Nuckolls, who’d kept them as slaves since they were children.

In her new book, Journey to Freedom: Uncovering the Grayson Sisters’ Escape from Nebraska Territory, author Gail Shaffer Blankenau tells the story of the sisters’ harrowing journey across the icy Missouri River into Iowa, and eventually to the perceived safety of Chicago.

It’s a story filled with sadness, despair and risk. But it’s also about those who fought for justice – brave abolitionists who hid fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, putting their lives on the line to help others be free. Their story made headlines across

the nation at a time when the country was wrestling with the slavery debate– thrusting the Nebraska Territory into the spotlight in the lead-up to the Civil War.

“The more I researched, the more I realized [Celia and Eliza’s] part in the troubled history of enslavement in Nebraska Territory was much larger than previously supposed,” wrote Blankenau, a Lincoln resident who is a professional genealogist, historian and speaker. She dove into primary sources to write Journey to Freedom

Those extensive sources led Blankenau to write a story that’s not just about the sisters, but one that dives into the slavery/ abolition debate– both in the Nebraska Territory and on a national level.

“Was Nebraska Territory slave or free? Could enslavement exist in a Northern climate? Was popular sovereignty working in Nebraska?” Blankenau wrote.“Celia and Eliza’s flight to freedom accentuated these questions and affected the political debate over the future of slavery as well as the future of the country.”

Journey To Freedom: Uncovering the Grayson Sisters’ Escape from Nebraska Territory

By Gail Shaffer Blankenau University of Nebraska Press 280 pp, hardcover, $35

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

IN THE 1960S, a young Ted Kooser faced a dilemma. His tiny Lincoln apartment offered little room for inspiration. As a graduate student at the University of Nebraska juggling coursework and an insurance job to pay the bills, he needed a dedicated space to write.

One day, Kooser found a refrigerator box in an alley, hauled it back to his apartment and transformed it into a makeshift office. In this humble cardboard sanctuary, he crafted poetry in the early morning hours before heading to work.

It was an unassuming start for a man whose words would one day capture the heart of America and earn him a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

In Ted Kooser: More Than a Local Wonder , author Carla Ketner’s writing feels like poetry itself. This heartwarming tribute celebrates the quiet persistence of a writer who found his voice

through storytelling. Ketner’s book, which won the 2024 Nebraska Book Award and the Midwest Book Award for Children’s Nonfiction, is both whimsical and poignant.

Through lyrical prose and watercolor illustrations by Omaha artist Paula Wallace, Ketner tells the story of Kooser’s upbringing. As a wiry, unathletic boy growing up in Iowa, Kooser often felt out of place. Yet his family’s love for the written and spoken word nurtured his curiosity and fueled his dream of becoming a poet.

“You never can tell what will happen when a curious little boy finds stories in the people who surround him and learns to write poems,” Ketner reflects. “When he fills the empty spaces in his soul with his own words and finds ... himself.”

Ketner first met Kooser at the Cattle Bank in Seward, where he was signing copies of Local Wonders: Seasons in

By Carla Ketner Illustrated by Paula Wallace University of Nebraska Press 40 pp, hardcover, $18

the Bohemian Alps, a beloved collection of stories about Nebraska. A year later, Kooser attended the grand opening of Ketner’s bookstore in 2004, where his books sold out instantly.

The vast skies, shimmering horizons and sweeping prairies of rural Nebraska have always shaped Kooser’s storytelling. Now retired to an acreage west of Lincoln, he still rises before dawn to write in a real office and takes long walks through the countryside, soaking in the landscapes that inspire his work.

by LISA TRUESDALE

JUST “AH-ONE, AH-TWO” things (thank you, Lawrence Welk) are required to hold a big community dance: people and music. As for where the people would dance to that music, it never really mattered, if there was room to move.

In his new book, Nebraska Ballrooms and Dance Halls, author Austin Truex helps dance aficionados and Nebraska history buffs waltz, sashay, jitterbug, swing and lindy hop through this fascinating history of dance venues around Nebraska.

Some places are long gone, lost to flood, fire or demolition. Others are still standing in all their glory, like the Hotel Norfolk in downtown Norfolk – now known as the Kensington Building – where a club dance in 1933 was advertised as being “cooled with magic weather.” At the time, this referred to air conditioning, which was not yet common in public buildings.

There’s also the Skylon Ballroom in Hartington, which has doubled as a

skating rink; the huge building has been moved around a bit, including in late 2024, but still retains its distinctive curved roof. And, of course, the Joslyn Castle in Omaha, a 1903 mansion huge enough to have its own dedicated ballroom for fancy events hosted by then-owners George and Sarah Joslyn.

Truex couldn’t possibly include all the hundreds of venues in use when ballroom dancing and big band music were at the height of their popularity in the mid-1900s. These included not just stand-alone dance halls and ballrooms – with their high ceilings, extravagant lighting and grand windows – but also open-air park pavilions, opera houses, grand homes, barns, school gyms, theaters, community centers, country clubs and closed-off streets.

So, Truex traveled around Nebraska to decide which ballrooms were the most interesting places to include in his book, then divided them into five regions, making Nebraska Ballrooms ideal for a danceophile’s road trip.

The book includes descriptions and historic photos of dozens of places where people could dress up in all their finery and bop along to the “wunnerful, wunnerful” musical stylings of Welk and other big names like Tommy Dorsey, Frank Sinatra, Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong and Guy Lombardo. Amazingly, some of the venues still hold dance-related events to this day.

“Dance halls and ballrooms are scattered across the state, from the largest metropolitan centers to the smallest unincorporated communities,” Truex wrote. “For as long as there have been Nebraskans, there have been Nebraskans looking for somewhere to dance.”

Nebraska Ballrooms and Dance Halls

By Austin Truex

Arcadia Publishing 128 pp, softcover $25

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

THEATER LIGHTS BLARED down on Colby Coash, a senior at the University of NebraskaLincoln. In front of hundreds, he dashed across the stage – naked except for dirty, white athletic socks. His brief but unforgettable scene as Hustler in the play Six Degrees of Separation lasted less than a minute. Yet his raw, profane rage directed at the play’s main character delivered an audacious and shocking performance.

In much the same way he bared his body onstage, former State Sen. Coash bares his soul in Running Naked: Surviving the Legacy of Family in Rural Nebraska , exposing the emotional turmoil of a man caught between the weight of his rural roots and the restless ambition that led him to leave. His memoir is as much a tribute to the people and place that shaped him as it is a story of personal reinvention.

Coash grew up in Bassett, a Rock County town of 1,010 people. His father owned and operated a fertilizer plant that was integral to the community’s economy. For many, following in those footsteps would have been the natural course. “[He] could not escape that legacy any more than the clothes he wore could escape the chemical smell, which permeated them,” Coash reflects, capturing the inescapable grip of his father’s vocation.

His mother, on the other hand, made the painful decision to abandon the family for a life outside Nebraska. When Coash was just 14 years old, she asked him to drive with her to California. “I was caught between both of these worlds, and at some point, I would need to chart my own course, but without guidance from either of them,” he writes.

Bassett was a foundation for Coash’s

growth. His writing details hard work, cleaning bins and laboring alongside his father. His dad instilled in him a work ethic and responsibility to serve his community that would serve Coash well in the years ahead. The very drive and determination that Coash felt compelled to leave at the plant eventually became the qualities that propelled him to success.

In 2008, Coash’s “shoe leather” campaigning led him to his first win as state senator for the 27th District in Lincoln. He knocked on doors across his district and even acquired a Razor scooter to reach more people.

His relentless efforts, shaped by the persistent hard work of his rural upbringing, won him the election by fewer than 100 votes. He served as state senator from 2009 to 2017, where he became a vocal

advocate for child welfare and people with developmental disabilities.

In Running Naked , Coash takes readers through the heart-wrenching decisions that led him to leave home in pursuit of other dreams. While his memoir describes the difficulties of leaving his hometown, it also underscores the lasting impact that a rural upbringing has on shaping character, values and the drive to succeed.

Running Naked: Surviving the Legacy of Family in Rural Nebraska

By Colby Coash Cahoy & Crook

254 pp, paperback, $20

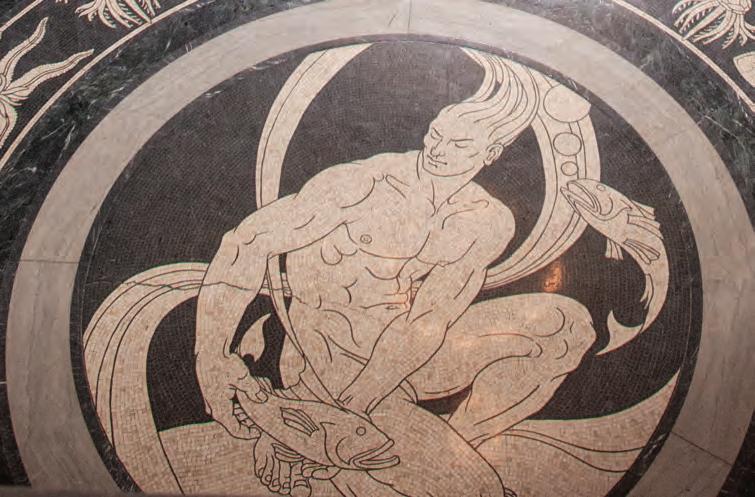

by LISA TRUESDALE

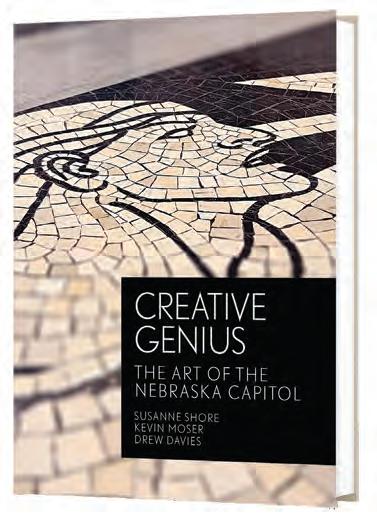

ANYONE WHO HAS stepped inside the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln knows it’s much more than a government building – it’s an art gallery, history museum and architectural masterpiece all rolled into one. Completed in 1932, the 15-story limestone structure houses nearly 150 exquisite artworks, offering visitors a captivating tour of Nebraska’s history – even from before it became a state.

In their new coffee table book, Creative Genius: The Art of the Nebraska Capitol, Susanne Shore, Kevin Moser and Drew Davies showcase breathtaking photographs of the building’s artwork, paired with engaging descriptions of each piece. Davies, founder of Omaha-based boutique design firm Oxide, is joined by professional storyteller Kevin Moser and Susanne Shore, Nebraska’s former first lady and an enthusiastic advocate for the state.

The trio’s collaboration began two years ago with the design of Nebraska’s latest license plate, inspired by “The Genius of Creative Energy,” a series of mosaics in the Capitol. This project sparked an idea: despite the building’s rich artistry, no comprehensive collection of high-quality photographs existed. The result is this remarkable book.

In many state capitol buildings, artwork can seem like an afterthought. Not so in Nebraska’s Capitol. From the beginning, its artwork was a deliberate part of the design. The Capitol features grand murals, vibrant mosaics, ceramic tiles, intricately carved marble columns, paintings, sculptures and detailed limestone reliefs on its exterior. Each piece tells a story, like the shimmering Venetian glass mosaic in the foyer that depicts teacher Minnie Freeman, who courageously led her 13 students to safety during the 1888 blizzard by tethering them together as they battled through the storm.

While the book’s stunning photographs bring the Capitol’s artistry to life, seeing it in person is unparalleled. If you visit, take Creative Genius as your guide. If a trip isn’t possible, the book offers an inspiring armchair journey through what is widely regarded as one of the most beautiful capitol buildings in the nation.

“Together, [the artworks] transform the building from the seat of government to an inspirational monument,” wrote former Capitol administrator Robert C. Ripley in the book’s foreword. “Years of sharing the Capitol with national and international visitors and architects have only reinforced what I knew as a child: Nebraska’s Capitol is remarkable.”

Creative

The

By Susanne Shore, Kevin Moser and Drew Davies Bison Books / University of Nebraska Press 224 pp, hardcover, $40

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

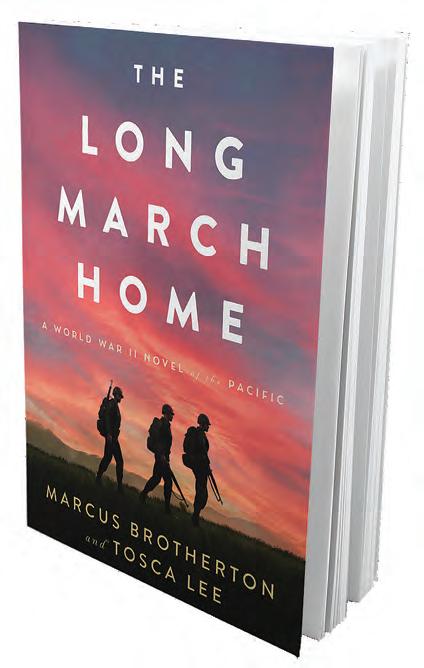

Tosca Lee’s newest book focuses on the Bataan Death March during World War II, following three fictional characters as they endure the true story and history of war in the Pacific.

NEBRASKA AUTHOR Tosca

Lee’s historical fiction novel The Long March Home may take place across the country in Alabama –and across the globe in the Philippines. However, important discussions about an obscure chapter of World War II history are happening right here in Nebraska due to the book’s selection for 2025 One Book One Nebraska.

The reading program is sponsored by Lincoln’s Nebraska Center for the Book and Nebraska Library Commission, which select one book by a homegrown author or with a Nebraska focus each year for book clubs and libraries to unite around. The Long March Home, co-authored by Tosca Lee and Marcus Brotherton, was selected for 2025.

Lee is a New York Times bestselling author of 12 books. She grew up in Lincoln after moving there in 1976. Her third-great grandmother was an early homesteader, and her mother was a native Nebraskan. Lee feels a strong familial connection to the state and now lives on a farm south of Fremont with her husband.

“Nebraska has such a rich history of writers. I’ve always been proud to be a part of that legacy,” Lee said.

The novel centers around the Bataan Death March, one of the most egregious atrocities in modern warfare. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, three fictional characters, Jimmy, Billy and Hank, survive horrific war crimes as they vow to make it home alive, together.

Though the novel is fiction, everything that occurs in the book – the brutality, warfare and events – is all real. Most of what is taught about World War II is set in the Europe stage. The Long March Home shines a light on a chapter of history most aren’t aware of to engender gratitude for unspoken war heroes in the Pacific.

Despite the novel’s heavy topic, it also highlights incredible resilience, brotherhood and sacrifice in the face of adversity.

“As an author, if I can touch someone enough to make them laugh, get angry or cry, I’ve done my job. This is a story worth crying over,” Lee said.

The Long March Home: A World War II Novel of the Pacific

By Marcus Brotherton

and Tosca Lee

Baker Publishing Group

400 pp, hardcover $27; paperback $20

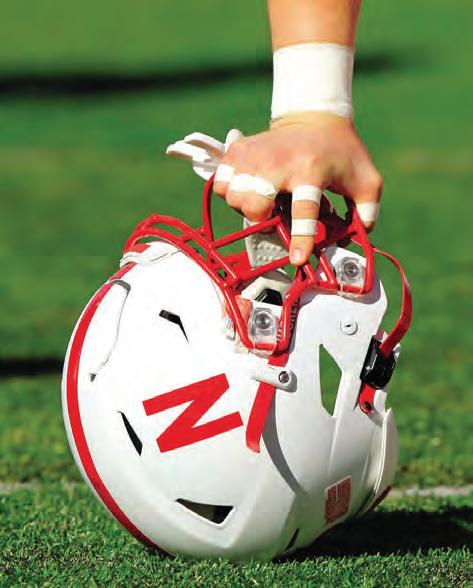

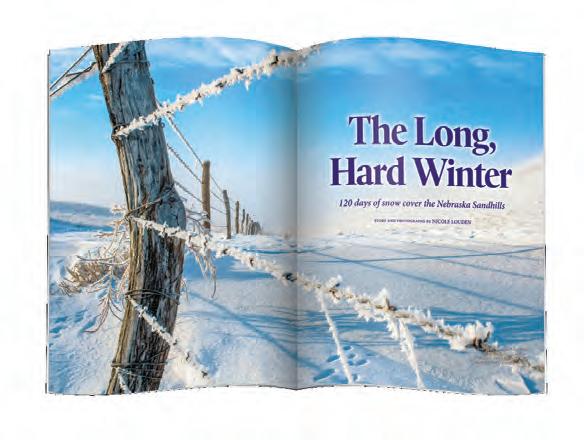

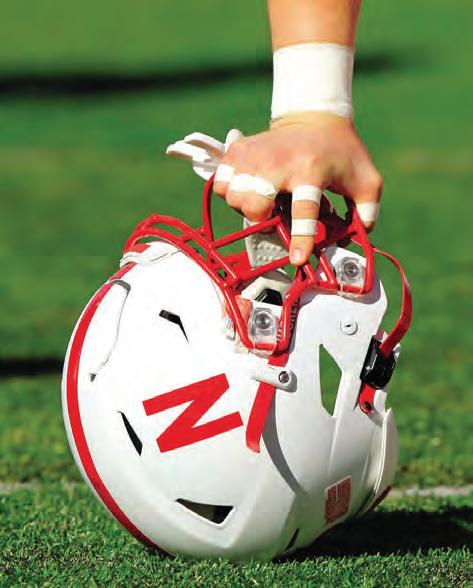

LIKE A SEASONED athlete, Ashley Spitsnogle approaches her live paintings – creating art in real-time – with the precision and mental focus of a championship contender. On Sept. 20, 2024, Spitsnogle stood before a sprawling three-by-five-foot canvas, brush and acrylic paints in hand, ready to capture the Huskers’ monumental 400th sellout game at Memorial Stadium.

Spitsnogle practiced her technique, visualized a win, and crafted a game plan. Now, it was showtime. From the 7th-floor press box, 90,000 fans watched her scarlet brushstrokes come to life.

Her preparation mirrors the devotion athletes bring to training and game day. “You put in the work to practice, you’re dedicated, you’re focused, you make sacrifices. Then, you perform,” Spitsnogle said.

The artist lights up when talking about live painting, describing it with the same passion that fueled her days as a high school and college athlete at Doane College, now Doane University, in Crete. For Spitsnogle, painting is as exhilarating as basketball or volleyball. “Live painting is very thrilling for me,” she said.

Sept. 20 marked the 400th consecutive sellout at Memorial Stadium – a testament to the unwavering dedication of Nebraska fans, who have filled every seat at every home game since 1962.

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI artwork by ASHLEY SPITSNOGLE

As Memorial Stadium filled with a sea of red, Spitsnogle painted furiously. A live painting typically demands three to four hours to complete, but she knew a work this detailed would require her to add finishing touches after the final whistle.

“It was the hardest live painting I’ve ever done. The game started in daylight and ended in night, so the lighting was al-

ways changing,” Spitsnogle said.

First, she sketched an outline in black charcoal to visualize the stadium’s composition. Next, she daubed a thin layer of acrylic paint to establish a base color for each section – a technique called blocking. Finally, she added details: hundreds of blurred dots representing fans in the stands, the iridescent glow of stadium lights on the “N” at midfield, and a moody night sky framing a full moon.

Spitsnogle’s canvas appeared on the big screen throughout the evening, giving viewers glimpses of its evolution. Her intention with this, and every Husker painting, is to commemorate the moment for everyone involved.

“This painting is an appreciation to the fans. Even though we did lose the game, people keep showing up for the next game and the game after that,” Spitsnogle said. “It brings them back to that special moment.”

This live painting event is just one chapter in the larger story of Spitsnogle’s intersection of art and sport. Born in Odell, just north of the Kansas border, she has been a Husker fan since birth.

Her parents were farmers, and Spitsnogle spent her early years helping around the farm. Her childhood companion was Lightning, a stout Shetland pony. The family refrigerator doubled as her art gallery,

cluttered with taped drawings of unicorns, horses and mermaids.

Spitsnogle graduated with an art degree while playing basketball at Doane College in 2008. After graduation, she earned a spot in a rigorous master’s program at Studio Art Centers International in Florence, Italy.

There, she painted for eight hours each day around the Italian city. Her work was critiqued by top-tier professors, including one who collaborated with Jeff Koons, famed for his metallic balloon animal sculptures. Florence marked a turning point. “After realizing I loved painting every day, all day, I knew I wanted to be an artist,” she said.

Spitsnogle’s first major professional work came when she illustrated Josh the Baby Otter, a children’s book promoting water safety. The book sold over a million copies worldwide and led to a partnership with the Michael Phelps Foundation.

In addition to her commissioned work and gallery exhibitions, she began live

painting at major events across Nebraska. In 2016, she painted at the Cattlemen’s Ball in front of 5,000 people. Her auctioned work sold for $8,000 to raise funds for cancer research, an event she participated in until 2021.

Spitsnogle created one of her most moving pieces, “Nebraska Strong,” for the Cattlemen’s Ball in Columbus in 2019. Following the devastating floods that March, the painting honors the resilience of Nebraskans and the support from neighboring states, who brought truckloads of hay to farmers who had lost cattle, land and livelihoods during the crisis.

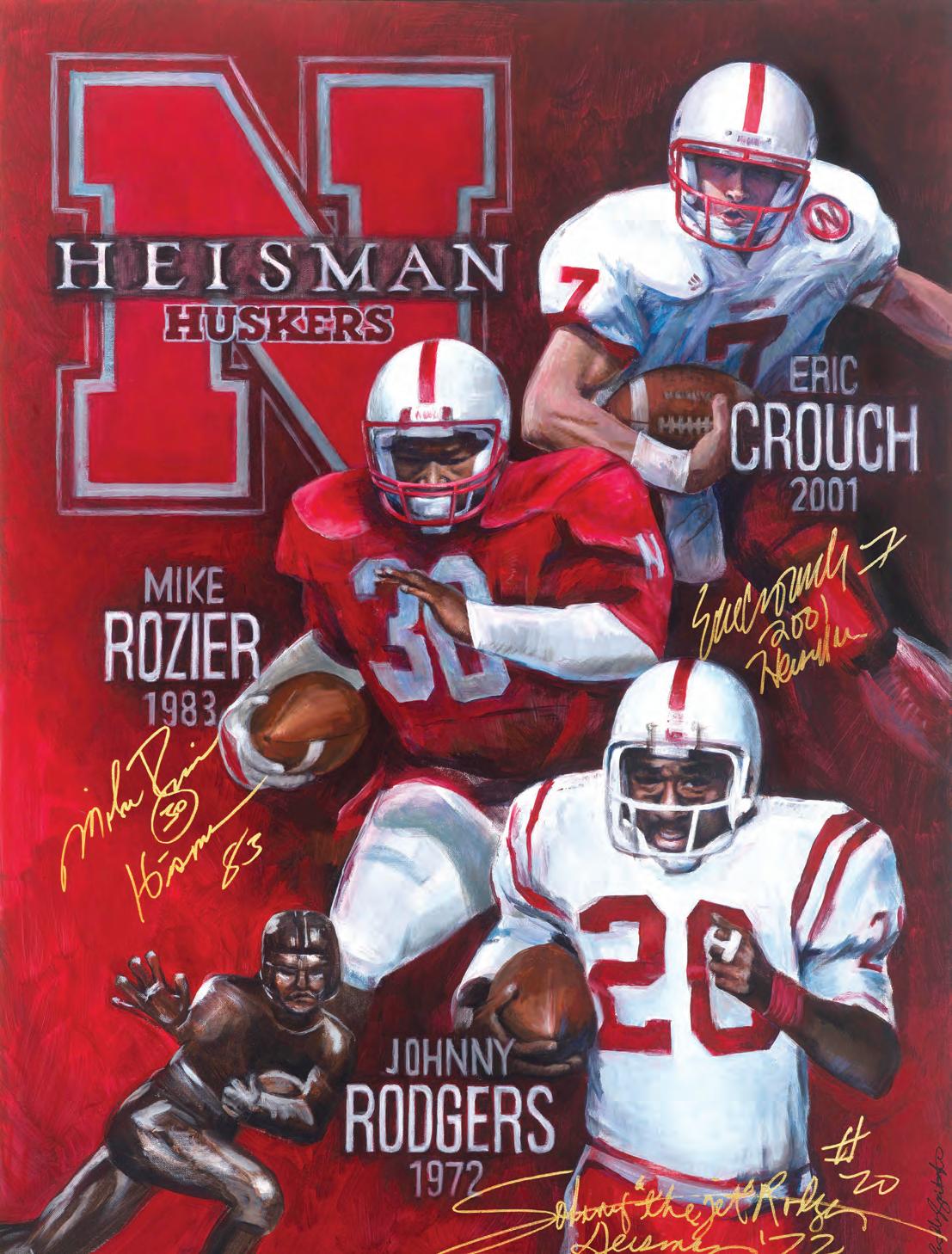

She also painted portraits of legendary figures like Johnny Rodgers, Nebraska’s first Heisman Trophy winner in 1972, and boxer Terence “Bud” Crawford after his historic 2022 win against the undefeated Errol Spence.

Crawford wanted to purchase the painting and offered to take photos with fans and sign prints, arranging a meet-andgreet at his home gym in North Omaha,

“People came from Western Nebraska over five hours away to hang out with Terence Crawford at the boxing ring. It was something people will never forget,” Spitsnogle said.

When fans witness her paintings, they don’t just see a moment in time – they feel their own nostalgic experiences of shared victories, ingrained in paint forever. “My art is capturing history that will live on past me,” she said.

Another transcendental piece, “Last Tunnel Walk,” is a moving tribute to Husker greats Brook Berringer and Sam Foltz. Berringer, who tragically died in a plane crash in 1996, leads Foltz, who was killed in a car crash in 2016, into the light at the end of Nebraska’s famed Tunnel Walk.

In 2018, Spitsnogle painted this emotional piece live at an event for Heartfelt Incorporated, a grief support organization. Foltz’s parents attended and watched her paint.

“This painting was emotionally heavy.

Beyond live paintings, Spitsnogle crafts expansive abstract pieces that pull on emotion, like “After the Storm” and “Taffy.”

Honoring these Husker men is something that’s bigger than me,” Spitsnogle said. Two original prints now hang in Memorial Stadium.

Although she is renowned for her sports-themed realism, there’s another side to Spitsnogle’s canvases at her Elkhorn studio. Abstract painting is where her brush finds freedom.

Some see elegant dancers in her swirling, splattered strokes; others, a winding river cascading down a mountain. “I’m really drawn to the emotional state abstract can evoke for people,” Spitsnogle said. “Each person has different life experiences and a different interpretation.”

This interpretive dance with the canvas contrasts sharply with the detailed nature of her realism imagery. Both approaches are essential to her creative process.

An acrylic painting, “Black Beauty,” depicts a powerful close-up of a black horse on canvas, each brushstroke angled to perfection. For now, she simply paints the horses. She hopes to someday own one again and ride through the prairies outside of Elkhorn.

“I can make something really good in a short amount of time,” Spitsnogle said about her live paintings. “That’s a talent I don’t want to waste.”

Giclée and original prints are available online, while her original canvases are displayed at her Elkhorn gallery on Main Street. For die-hard Husker fans, the iconic Husker Hounds shop on South 84th Street in Omaha doubles as Spitsnogle’s gallery.

Spitsnogle is excited to continue pushing the limits of her art and performing for larger crowds. “I want to keep painting at bigger events and capturing those special Husker moments as they arise,” she said.

As Johnny Rodgers once told her, she captures history with her brushstrokes. By preserving the spirit of Nebraska sports, Spitsnogle not only leaves her mark on the canvas but on the hearts of Husker fans worldwide.

and

These Nebraska women defied norms to homestead and ranch in the Great Plains

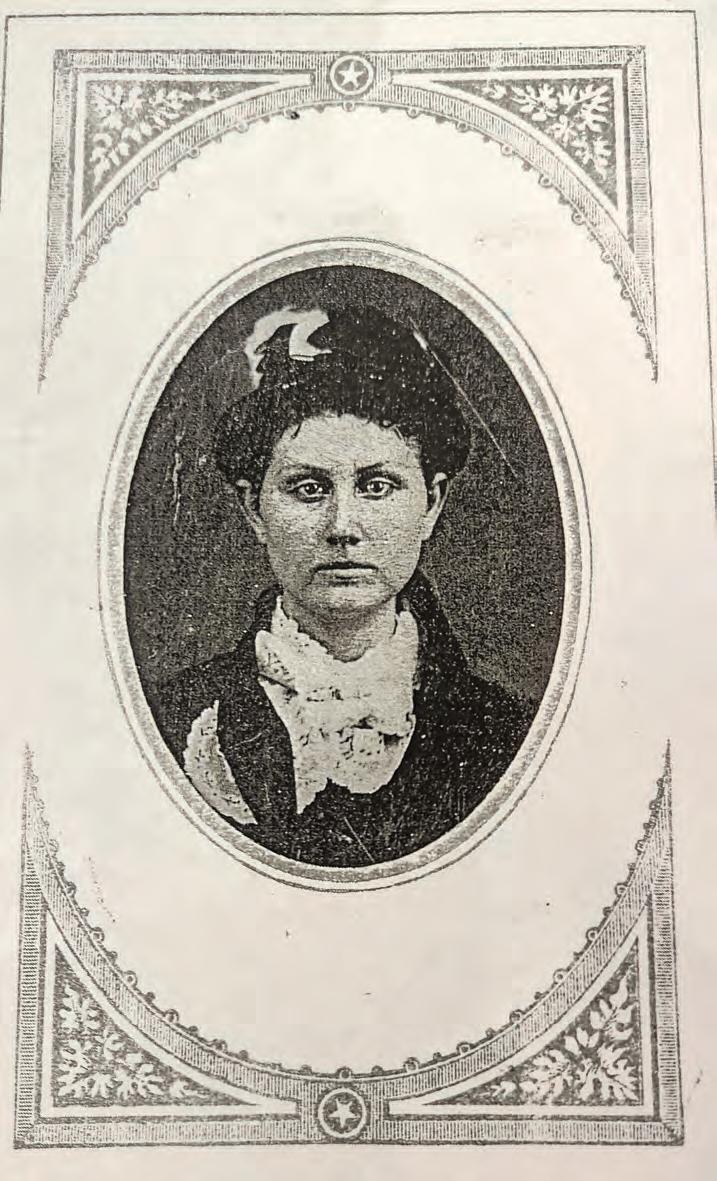

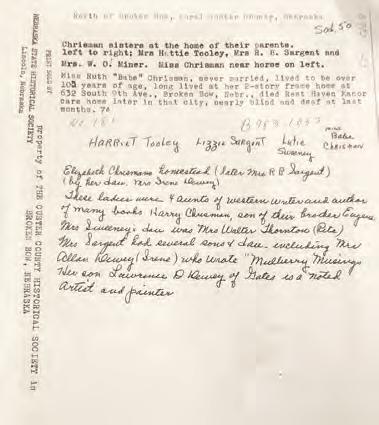

Women were among the many landholders that claimed 160 acres of the Nebraska Territory under the Homestead Act of 1862, including the Chrisman sisters, from left: Hattie, Lizzie, Lutie and Ruth.

story by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

photographs by NEBRASKA HISTORY

MUSEUM and HOMESTEAD

NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

TTHE RUGGED, WINDSWEPT prairies of the Great Plains and the rolling knolls of the Sandhills posed formidable challenges for homesteaders and ranchers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Women made up nearly a quarter of those who braved the unknown to claim up to 160 acres of land under the Homestead Act of 1862.

Essie Davis, a hatmaker turned rancher, forged a life of resilience and innovation in Cherry County. She transformed her late husband’s 3,000-acre ranch into one of Nebraska’s most successful operations during the Great Depression, earning national recognition for her cattle breeding and conservation efforts.

Lucinda Tann Stone, a Canadian immigrant, built a life on the Nebraska frontier in Dawson County during the 1880s. She overcame racial and gender barriers to become a successful homesteader. Meanwhile, the Chrisman sisters – four unmarried women – claimed land in Custer County during the same era. Choosing to delay marriage, they labored tirelessly to establish themselves as pioneers on the Great Plains.

Together, their stories highlight the tenacity and determination of women who helped shape Nebraska’s agricultural and ranching legacy.

Outside their sod home, the Chrisman sisters – Elizabeth “Lizzie,” Lucy “Lutie,” Harriet “Hattie,” and Jennie Ruth “Ruth” – wore brown-and-white gingham and percale dresses. Two saddled horses, Bet and Jessie, stood protectively on either side of the sisters. Behind them was Lizzie’s modest house, constructed from sod blocks and prairie grass, located on the Goheen settlement near Lillian Creek in 1886.

The women gazed stoically into photographer Solomon D. Butcher’s camera. It was common for proud landowners to display their possessions in photographs as a testament to their hard-earned success. However, Ruth, who was only 11 when her family moved to Custer County, later expressed her dislike of the image. “I looked like a horse thief,” she said of her messy hair hanging over her forehead.

Because the government only recognized husbands as heads of households, women like the Chrisman sisters delayed marriage to maintain ownership of their land claims. The four sisters prioritized pioneering on the Great Plains over societal expectations.

Lizzie, the eldest, purchased her land from the government in 1886 for $2.50 per acre under the Preemption Act of 1841. Lutie filed her claim the following year using the Homestead Act of 1862, and Hattie later followed suit.

The youngest sister, Ruth, never claimed land. Although she received a patent, so did another. Lewis Cushman went to the courthouse before Ruth, leaving her without her own land. She lived with her sisters before becoming a teacher and later a nurse.

In 1883, the sisters traveled with their parents and three brothers in five wagons from Nemaha County to Custer County. Their father settled 14 miles north of Broken Bow, while the siblings claimed adjoining land totaling 2,281 acres, according to land management records.

Hattie, Lizzie and Lutie (left) each held three landholder claims by forestalling marriage, allowing them to maintain ownership in their own names without a husband.

The unmarried sisters rotated between living together and establishing their own farms, building lives of self-sufficiency on the prairie. Ruth fondly remembered gathering fruit during the summers. “I can remember how we used to gather wild fruit in the canyons. Such delicious plums and raspberries – and the grass would be over our heads,” she wrote in a letter to Martha Turner, a Nebraska State Historical Society librarian. “Summer months were beautiful, such wonderful rains –never heard of droughts those days. But the winters were quite severe.”

Ruth also recounted surviving the Blizzard of 1888, known as the Schoolchildren’s Blizzard. She was at school during the deadly storm, which claimed the lives of more than 100 Nebraskans on January 12. “We had no fuel to burn but corn stalks – so we had to ‘move out.’ We went with the storms to the nearest neighbor, a widowed lady. She was out of fuel, too – had to burn some old chairs to keep us warm.”

While Ruth never married, her three older sisters eventually did, proving that marriage and a successful life of homesteading were not mutually exclusive.

Lizzie, the eldest, spent her later years farming with her husband near Broken Bow. Ruth wrote, “[She] still loves to gather the wild fruit every summer – walks and carries it home. Says it reminds her of the early days in Custer Co.”

Many Black women in the 1880s lacked the education to read, write or even sign their own names. Lucinda Stone Tann, a prominent homesteader who moved from Buxton, Canada, to Dawson County in the late 1800s, was one of the few who could.

At age 21, Lucinda immigrated to the United States in 1879. Shortly thereafter, she hired a local man named Elijah Tann to build a 14-by-24-foot sod house on a small plot of land, paying $25 for the construction.

Elijah and Lucinda married in November 1881, just a few months after the house was completed. Despite their union, Lucinda never added or signed over the deed to her husband – a rare practice for women in the 19th century.

At the time, the doctrine of coverture dictated that a married woman’s legal rights, including property ownership, were transferred to her husband. Wives could not own property in their own names, and husbands held control over any land their wives brought into the marriage.

However, Nebraska’s Married Women’s Property Act of 1871 marked a turning point. It granted women the right to own and control property independently, preventing husbands from selling their wives’ property or using it to pay off debts. This legal shift allowed Lucinda to retain ownership of her homestead, but the law was still relatively new and far from socially accepted when she filed her claim in 1881.

Over the next five years, Lucinda and Elijah welcomed three children: Ada, Clinton and Ida. Lucinda later had three more children and officially gained American citizenship on Dec. 18, 1886.

The family thrived on their homestead, cultivating five acres of planted land and

breaking ground on an additional 50 acres. Their farm featured six fruit trees, two horses, three cattle, six hogs and 50 chickens. The fertile soil provided bountiful harvests of corn, wheat, and oats. Together, Lucinda and Elijah worked tirelessly to plow, plant and harvest their crops. Lucinda also shouldered the domestic responsibilities of cooking, cleaning and caring for their children.

Though she could not vote – a right that women in Nebraska wouldn’t gain until 1920 – Lucinda’s landownership provided her with significant economic and social power. Because the home remained in her name, decisions about the property rested solely with her.

In the 1890s, the family was forced to sell their Nebraskan land due to prolonged drought and low farm prices. They relocated to Mustang, Oklahoma, where they started anew on 160 acres. Today, visitors to Homestead National Historical Park in Beatrice, Nebraska – 200 miles east of the Stone family’s original plot – can explore

the state’s homesteading history. The park showcases preserved landmarks such as a hardwood cabin, a red-brick schoolhouse and tallgrass prairie reminiscent of Lucinda Tann Stone’s land.

Visitors learn about other individuals such as the colony of DeWitty, the most populous and successful settlement of Black homesteaders in Nebraska. Black homesteaders, like Lucinda, defied systemic barriers to own land and carve their own space in the Great Plains.

Cherry County Essie Davis had no agricultural experience when she inherited her husband’s 3,000-acre ranch north of Hyannis following his death in 1915. A hatmaker by trade, Davis had owned a shop in Ogallala before embarking on her unexpected journey into ranching.

She met Arthur Thane (A.T.) Davis in 1911 while traveling to the Denver Stock Show with her father. A.T., the owner of a Cherry County ranch, married Essie in June 1913. The couple welcomed their son, A.T. Jr., a year later.

Tragedy struck just four months after A.T. Jr.’s birth when her husband passed away, leaving Essie with a small child, a ranch and $80,000 in debt. Undeterred, Davis took on the challenge of running the ranch, determined to succeed.

Martha McKelvie later chronicled her story in the biography Sandhills Essie. Reflecting on her early hardships, Davis said, “I decided to live my life each day and live it so that I could look any man in the face and tell him to go to hell!... A woman’s ranch problems are no different than a man’s, except that they are often emphasized or exaggerated.”

In 1930, the Great Depression wreaked havoc on the ranching industry. Cattle prices plummeted to as low as $2 per head, wages stagnated and the Dust Bowl drought devastated the plains. Despite these challenges, Davis steadily expanded her ranch, earning income from cattle sales, land leasing and loans.

By 1934, she had grown the ranch from 3,000 to 25,000 acres. Davis specialized in purebred Hereford cattle, prized for their high-quality beef, and worked diligently to improve her herd’s genetics by acquiring healthy bulls and avoiding inbreeding. As one of the few female ranchers of

her time, Davis stood out in a male-dominated industry.

Her tenacity was famously highlighted during a bidding war with former Nebraska governor Sam McKelvie. When Davis held her ground on a Hereford bull, McKelvie reportedly exclaimed, “Who in hell is that woman who thinks she can outbid me!” McKelvie’s neighbor replied, “That’s Essie Davis, and she can!”

Davis also embraced innovative practices like range management, balancing the needs of her animals with sustainable grazing techniques. She and her son planted 250,000 trees across the ranch, further cementing her commitment to conservation.

In 1939, Davis became the first woman in Nebraska – and the fourth in the nation – to receive the prestigious Master Farmer Award. Her contributions to prairie conservation and cattle breeding earned her a lasting legacy as one of Nebraska’s most successful ranchers.

Essie Davis passed away on Feb. 6, 1966, but her influence endures in the Sandhills and in Nebraska’s ranching practices. Her life story is documented in Sandhills Essie , available in libraries and online.

Essie Davis prioritized her herd’s long-term health by introducing new bulls to promote healthy genetics. Her impact is among the many stories of female homesteaders who shaped the region’s history and future.

History Nebraska

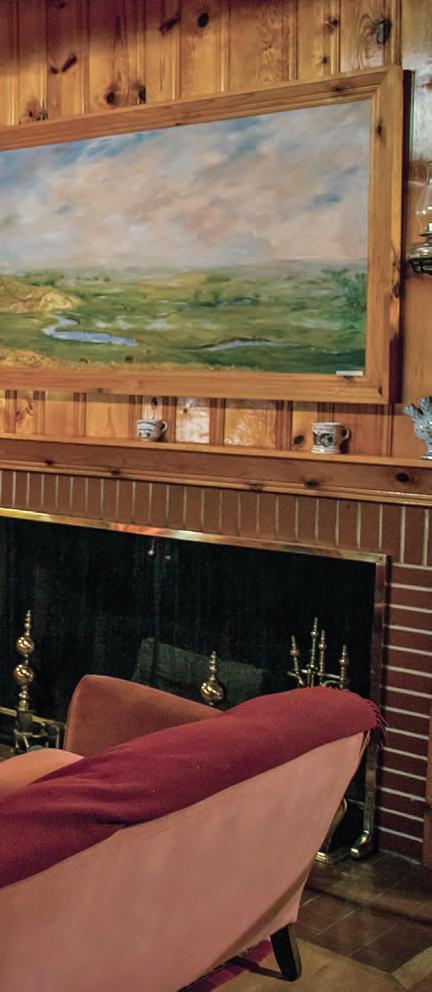

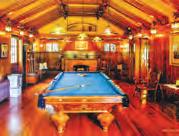

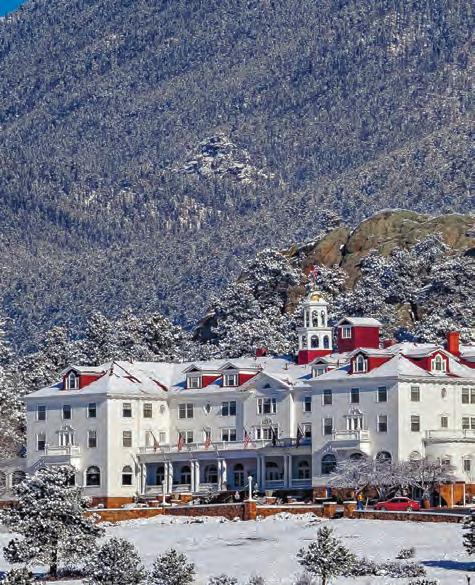

Sandhills cattle heiress dined with presidents and left a legacy of land for the world

VISITORS have traveled here from as far away as Greenland to see the finest of sterling silver. Tourists from China have gazed at the prized glass crystal and china, but then they notice something shining out that is even more valuable. Land.

During her years in Washington, D.C., Eve Bowring was right at home with presidents and kings, pioneering new political territory in 1954 as Nebraska’s first female U.S. senator. But she was truly at home on this massive Sandhills spread, where the first fence posts were pounded into the ground by a pioneering rancher in 1894.

That pioneer was her beloved husband, Arthur Bowring, and for decades after his passing, Eve watched over their thousands of acres on her own, a distant boss lady to the ranch hands who cared for her beefy Hereford cattle. The land belonged to her, and now the working cattle ranch still stands.

Now 40 years after Eve’s death on the eve of her 93rd birthday, the magnificent Arthur Bowring Sandhills Ranch State Historical Park lives on near Merriman. Her wondrous gift to Nebraska of these 7,200 acres was also her final gift of loyalty to her beloved late husband; the donation preserves the land as he knew it, forever barring real estate interlopers from acquiring the Barr 99 Ranch he started in 1894, two years after Eva Kelly “Eve” Bowring was born. Now, each day of the year, travelers are welcome to stop and visit, and to walk about a place where time has stood still for more than 100 years.

Eve’s foundation donated her land, and the ranch that once frowned on visitors now is an open gate to the past. Visitors can stop in and witness a working cattle ranch, replica sod house and the magnificent collection of glass, china and silver that Eve brought from all over the world to this lonely yet precious land a few miles outside of Merriman off Highway 20.

In its heyday, Arthur and Eve Bowring’s ranch extended over 13,000 acres, but there are still plenty of pristine meadows and trees to gaze over, and the serenity of this Sandhills land is perhaps an even greater treasure than the many Bowring collections.

“This facility is a diamond in disguise,” said Diane Burress, former Bowring State Park superintendent who cared for the cattle and maintained the upkeep of the ranch as part of her skilled juggling act of duties here.

It was said that since Eve had such a vast collection of the finest china, a plate would never be served on her dining table more than once. She also was known as a shrewd shopper of the finest Persian rugs, where a half dozen of the carpets would be brought to the ranch and then all the furniture would get moved out of the home and rearranged each time with a different rug. Eve would carefully eyeball each arrangement and then decide on a single carpet choice.

There are many tales of her folksy nature and fearless ranching spirit, but a neighbor remembers her as often distant, aloof, stern and almost never home. Despite all the elegance and luxury, and the

meetings with presidents and kings, this elderly lady would sometimes find herself alone at this stately house, miles away from the nearest living soul.

“She could be hard, but most of the time I found her to be a jolly person,” said Gerald Goodwin, who ran the ranch for her from 1955 to 1965.

Even though Goodwin quit the foreman’s job with a sour taste in his mouth when Bowring suddenly became the most demanding of boss ladies, he later returned in those final years after she asked for his help during calving season. “She treated me like her son, really.”

There were many happy days, and also one of his saddest mornings.

On the night before her 93rd birthday, the first woman to serve Nebraska as a U.S. senator was reading a James Michener book when she drifted into a final sleep. The housekeeper found her on that bed in the grand home of her ranch with the

novel Chesapeake still open and resting by her side. The final chapter on the amazing story of Eve Bowring closed on Jan. 8, 1985, 93 years from the day she was born on Jan. 9, 1892, in Nevada, Missouri.

Goodwin had been sitting in the Bowring home on Eve’s final evening when suddenly the housekeeper came from the bedroom and told him that Eve had passed away. Just hours later, Goodwin endured the hardest job he ever faced on this ranch. That morning, he helped lift Eve’s lifeless body from her bed.

Eve endured and celebrated a long life full of change, and yet in many ways she remained the same with her powerful personality that could be both as warm as the Sandhills’ summer breeze, and as cold and harsh as its winter wind.

Her biggest change came when she was sworn in at the U.S. Capitol by Vice President Richard Nixon on April 26, 1954, to become the state’s first fe -

male senator. She served the final seven months of a seat left open by the death of Sen. Dwight Griswold.

DESPITE EVE’S EFFORTS to immortalize her husband through the creation of the state park, he trails far behind the pioneering political legacy of his widow. Still, Arthur Bowring’s accomplishments in ranching and public service are worthy of filling much of the 7,400 square feet at the ranch’s visitor center.

Arthur was the seventh of 10 children of the British-born railroader Henry Bowring, who brought his family to the Sandhills determined to farm and ranch on homesteaded land near Gordon. By 1894, just three days before he turned 21, Arthur joined his father’s ranching quest and acquired his first 160 acres off homesteaded land near Merriman.

Arthur made great strides in ranching when he started raising the white-

faced Hereford cattle. His grazing land kept growing thanks to the creek flowing through the ranch. He built a sod house on his land in 1894 and lived inside his dwelling until 1908 when he married a schoolteacher from Hooper named Anna Mabel Holbrook.

Within months Arthur built a fourroom wooden home onto the sod house. The couple soon were expecting a child, but in August of 1909, as Ar-thur was trapped with a haying crew in a violent thunderstorm miles from home, Anna and their son died during childbirth in front of helpless family and friends.

For nearly 20 years, Arthur went through life alone, expanding his herd

and the rooms on his ranch house. Then on an autumn day in 1927, fate and a broken-down car brought a turning in the road.

By this time, Eve was trying to cope with her own severe challenges. One of her four sons died at just 3 months old, and according to Bowring Ranch records, she endured for nearly a dozen years of abuse from her alcoholic husband, a livestock feed salesman named Theodore Forester, whom she married in 1911. Eve fled her husband in Kansas City, Mo., taking her three sons to Lincoln. She eventually divorced Forester in 1924.

Eve soon began blazing her own trail as a traveling saleswoman with Norfolk

Descendants of the prized white-faced Hereford cattle raised here generations ago still roam about the 7,200 acres at the Bowring Ranch state park overseen by Superintendent Diane Burress. Burress worked on the ranch for nearly 17 years until she retired in November.

Steam Bakery. She not only had an unusual job for a woman in the mid-1920s, but even more remarkable was the 40,000 miles she drove on rural roads each year to cover a sales region that ranged from Norfolk to the Wyoming border.

It was on a long journey of sales calls that her car broke down near Merriman. Arthur was heading back to the ranch and came to the rescue. The automobile soon was back on the road, and after they exchanged addresses, the courtship got rolling, too.

After many letters, the romance bloomed and the 55-year-old rancher married the 36-year-old Norfolk sales gal in Valentine on April 13, 1928. Eve not only joined her husband’s trail into the ranching world but also into public service, where Arthur was a county commissioner, state legislator, justice of the peace and deputy of the Nebraska Game and Fish Commission. Arthur died on March 19, 1944, at 71, leaving Eve standing alone to watch over the 12,000 acres of ranchland. Political insiders soon starting watching the Sandhills heiress.

Eve became the first woman to chair the Nebraska Stockgrowers Association Brand Committee and quickly became a force in Nebraska GOP politics. Then in 1954, she reluctantly agreed to Gov. Robert Crosby’s repeated requests for her to fill Griswold’s seat. She was appointed U.S. senator on April 16. She was escorted to the front of the Senate chamber on April 26 by Nebraska Sen. Hugh Butler, who died just months later.

During the swearing-in ceremony, Nixon playfully announced Butler’s message to the gallery: “The senior senator from Nebraska has asked the chair to announce that no implication should be drawn from the fact that the senior senator from Nebraska is a widower and the junior senator from Nebraska is a widow.”

“I’m going to have to ride the fence a while until I find where the gates are,” Eve told a reporter shortly after she joined Maine’s Margaret Chase Smith as the only women in the U.S. Senate.

By June, Eve closed those Senate gates and decided not to run for an odd 60-day term to fill out Griswold’s term. Instead, educator Hazel Abel won the election, but to add to the voters’ confusion, the first

Nebraska woman to follow another Nebraska woman into the U.S. Senate in the nation’s history also resigned from office on Dec. 31, 1954.

Despite her short service, the 5-foot-7 Bowring was no shrinking violet on Capitol Hill. Her stature with her colleagues quickly grew when she gave an impressive speech on the Senate floor backing President Dwight Eisenhower’s plan to provide flexible price supports for farmers.

After her term was up, Eve seemed to spend even more time in Washington and away from her ranch. She was on the advisory council to the National Institutes of Health. Ike appointed her to serve on the federal Board of Parole, a post she held from 1956 to 1964.

Eve and Ike became good friends. Ike naturally bonded with this witty cattlewranglin’ gal because of his Kansas roots, and his wife, Mamie, was said to have sparked Eve’s interest in collecting finecut crystal. The Eisenhowers planned to vacation with Eve at her ranch, but the president suffered a heart attack in 1955 and that dream visit was canceled.

WHEN SHE RETURNED to Merriman in 1965, ranch manager Gerald Goodwin suddenly saw a different Eve.

“She wasn’t there to boss me very much when she was with the parole board,” said Goodwin, who claims the Bowring cattle flourished when he was manager. “Then she came home and I couldn’t do anything right. She wanted to show her authority, that she was Mrs. Bowring. She didn’t want me to run the ranch anymore. That’s what it amounted to.”

Ken Moreland grew up in the 1950s on his family’s ranch, where Eve was a neighbor, and always a distant one. He also worked on the Bowring ranch over several decades, helping with the spring brandings. He recalls Eve’s appearances in her big Cadillac. He said she often would wear fancy gloves, but those gloves never reached out with a friendly wave.

“She wasn’t much of a social person around the Sandhills,” said Moreland, whose family still maintains its 3,200acre ranch at the Bowring borders. “She didn’t have much to do with the common

folk around Merriman. She’d always come to the branding in a Cadillac and summons her foreman like it was an audience with the pope. Pretty soon she’d be done and roll the window up and drive off. She had a hands-on approach without being hands-on.”

Moreland said Eve could be an unreasonable haggler about cattle crossings. It was no big deal for his uncle to allow the Bowring cattle to use his land during the seasonal migrations, but Eve drew the line about letting Moreland cattle munch on her grass while they rested.

On

On the day of her funeral, Moreland’s father served as a pallbearer, and Goodwin asked Moreland to stay in the Bowring house to guard against thieves. Moreland said it was an eerie experience roaming alone in her big house in the dark. His creepiest encounter at the ranch came years earlier when he was pushing calves up chutes deep into the night, and then he was suddenly spooked by Eve’s voice behind him in the darkness.

“Out of nowhere she says, ‘How you boys doing?’ ” Moreland recalled. “It scared the living hell out of me. Then she turned around and walked home. But it was pitch black and she never even had a flashlight.”

One of the most memorable Moreland family stories of the ranch matron comes from Steve Moreland, a cousin of Ken’s who grew up near the Bowring ranch. Steve

tells of the day Eve fired a veteran ranch hand so she could hire some guy who had blown into town and had impressed the boss lady. The fired man stuttered when he spoke, and when he came to pick up his final paycheck, Steve says he got the last word: “M-m-m-mrs. B-b-bowring, I hope all your d-d-damned cows d-ddie.” The story took another twist when the hotshot new worker stole a pickup and fled the county. Eve hired back her slow-taking, hard-working rancher.

Goodwin saw some of those hard ways from a tough lady, so tough that she once drove all the way home on her own after hip surgery in Omaha. She pulled up the Caddy, and Goodwin helped her limp into the house. He mainly looks back with fondness at her caring nature, like those times she’d bring ice cream out to him when the Sandhills heat was baking

over the hay fields. His wife, Inez, says Eve was always very grateful when they had her over for supper; several times Eve invited them to her house and prepared delicious meals.

“She was a really good cook and she appreciated anything you did for her,” Inez said. “I think maybe a lot of people were jealous of her. She might have come across as aloof if you didn’t know her as well as we did. She was never that way to us.”

Moreland’s wife, Sharon, also saw that kindness as a young schoolteacher in the mid-1970s. Sharon didn’t have a car and was walking to work in the cold when that Cadillac pulled up and Eve warmly welcomed her inside.

Moreland got a firsthand look at Eve’s charm when he came by to collect a bill for cattle feed. The boss lady decided to give him a personal tour of her magnificent

home. She showed him all of the finest silver and china and a massive Persian rug, but the greatest treasure for Moreland was when Eve pointed to a dress and shared the story of John F. Kennedy and the pool. She was wearing it at a presidential inauguration party for JFK when the elegant gown took a soaking after a drunken reveler pushed her into the pool.

“She was as charming and witty and as friendly as you could ever ask,” said Moreland of Eve on the grand tour. “She could be absolutely the most gracious person in the world. She was elegant and very educated. I don’t know how educated she was school-wise, but she was wise in ways of the world.”

People from around the globe have come to take the tour Ken got as a young man. They can see a painting of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, who met with Eve to

seek her expertise on using Sandhills irrigation strategies in the Ethiopian desert. The African ruler was said to have gotten invaluable guidance from Eve on accessing the desert groundwater, which had the potential to prevent the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives during the drought famines. But before the plan was implemented, he died in 1975 after a military coup.

There are the pictures of another presidential pal, Richard Nixon, with whom she shared a birthday. But when the Watergate scandal hit, a disgusted Bowring was said to have turned all of the Nixon photographs around in her home so she no longer had to look at the leader whom she felt had turned his back on the nation.

In many ways, Eve’s spirit is seen through former park superintendent Diane Burress herself. She shares a ranch with her husband south of the former town of Eli, but most of her time over the last 15 years was spent watching over the land Eve once ruled. She’s had to mow all the lawns, maintain the buildings and care for dozens of cattle, some of them direct descendants of Arthur’s first Herefords.

“These cows are not used to horses, so I do everything on foot or a pickup,” Burress said. “When you go to sort them, you just point at them and they’ll walk through the gate.”

Sometimes the days started as early as 6:30 a.m. and ended at 9 p.m., but it is those final rays of light that are the brightest of all for this guardian of Sandhills history.

“I love the evening because you can look out over the meadow with the sun setting and it’s just absolutely gorgeous,” Burress said. “I did not know Mrs. Bowring personally, but as long as I have worked here, I like to think that I do know her.”

She stared out over the vastness of the land as the sunlight fades into the Sandhills. Perhaps the woman who brought so many treasures here would gaze upon that evening meadow and find the most precious prize of all.

This story originally published in the November/December 2012 issue.

BROKEN BOW

Custer County Museum, p 47

FREMONT

Dodge CountyHistorical Society Museum /Louis E. May Museum, p 47

GOTHENBURG

Gothenburg Pony Express Station, p 57

GRAND ISLAND

Stuhr Museum, p 47

KEARNEY

Museum of Nebraska Art, p 46

LA VISTA

Czech and Slovak Educational Center and Cultural Museum, p 47

MADISON

Madison County Museum, p 46

YORK

Clayton Museum of Ancient History at York University, p 47

Madison County, NE

Where families overcame challenges of blizzards, droughts, floods, tornadoes, grasshoppers, epidemics and hard times!

Remember the PAST Build the PRESENT Create the FUTURE

Please call ahead. Museum may be closed for bad weather, illnesses, etc.

Hours: 1:30-5 pm Mon-Fri or call for appointment 402-454-2313 or 402-649-1881

Admission:

Louis E. May Museum

Explore our exhibits featuring the Immigration Room, Music Room, Sokol Room and Josef Lada calendars from the 1940s.

Our gift store offers many beautiful Bohemian items from the Czech land.

recipes and photographs by DANELLE

McCOLLUM

THESE THREE SWEET dishes prove that vanilla is the subtle star of any dessert table. From crunchy shortbread to fluffy waffles and vanilla-infused syrup to moist, banana-packed cake, each bite celebrates vanilla in all of its delicious forms.

Fall in love with these buttery shortbread bars bursting with vanilla. The secret? Vanilla bean powder, which gives it that lovely “spotted” look and a flavor baking can’t fade out. Dust with sparkling sugar for that extra “wow” factor.

Add flour, sugar, salt and vanilla bean powder into a food processor and pulse to mix. Add butter and pulse until fine crumbs form. Don’t over process to avoid crumbly dough.

Press dough evenly onto a 8- or 9-inch baking dish lined with parchment paper. Bake at 325° for 40-50 minutes until golden. Transfer to wire rack. Cut into bars and sprinkle with sparkling sugar while warm. Allow bars to cool before serving.

2 cups flour

2/3 cups granulated sugar

1/2 tsp salt

3/4 tsp vanilla bean powder (or 1 tsp vanilla extract)

1 cup cold butter, cubed Sparkling sugar for dusting, optional

Ser ves 12

Crispy on the outside and fluffy on the inside, these waffles drizzled with decadent vanilla syrup are what breakfast dreams are made of. Top it off with whipped cream and fresh banana slices.

In a large bowl, beat eggs with hand beater until fluffy. Beat in flour, milk, vegetable oil, sugar, baking powder, salt, cinnamon and vanilla until smooth.

Spray waffle iron with non-stick spray. Pour 1/3 cup of batter onto hot waffle iron and cook until golden brown.

Whisk water, sugar and cornstarch in a medium pan. Bring to a boil and stir constantly for 3-5 minutes.