Katie Schultis, a fourth-year University of Nebraska Medical Center student, is from Diller, a town of 250 in southeast Nebraska. Like many rural areas, Diller faces a critical shortage of health professionals.

“Growing up, I was well aware of the limited access many communities in our state have to the care they need and deserve,” Schultis says. “That’s why, when my education is complete, I’ll be going home.” Schultis is not alone. Nearly 60% of the physicians, dentists, pharmacists and physician assistants practicing in Greater Nebraska – outside of the Omaha and Lincoln metro areas – were educated at UNMC and received training at Nebraska Medicine, the university’s primary clinical partner. But there is still work to be done. UNMC and Nebraska Medicine, a leading American academic health system, are committed to addressing the growing health care needs of all Nebraskans - UNMC, as the state’s only public sciences university, and Nebraska Medicine, as a major clinical partner of UNMC and the primary teaching hospital for the state.

In collaboration with the University of Nebraska at Kearney, UNMC has grown in central Nebraska, adding new facilities and expanding programs. This includes a $95 million Rural Health Education Building and medicine, nursing, pharmacy and public health programs.

The expansion builds upon the success of the Health Science Education Complex, which opened in 2019 through a partnership between UNMC and UNK. Due for completion in late 2025, the new project will increase the number of health professions students training in the region by more than 250% and help fill shortages in medical professions around Nebraska.

Kaitlyn Schultis & Edson DeOliveira UNMC College of Medicine, Class of 2024

“The combined campus in Kearney will be the largest interdisciplinary health care rural training campus in the United States,” UNMC Chancellor Jeffrey Gold, MD, says. “It’s just another way that Nebraska is leading the world.”

When fully operational, the Rural Health Education Building and existing Health Science Education Complex will have an annual economic impact estimated at $34.5 million.

Nebraska Medicine, as the primary clinical partner of UNMC, is dedicated to providing health care for all Nebraskans. As a non-profit, integrated health system, its providers care for patients from every county in the state.

Across Nebraska, 70 specialty and primary care clinics offer a wide range of services. This includes 20 satellite clinic locations in towns such as Alma, Broken Bow, Cambridge, Columbus, Cozad, Grand Island, Hastings, Kearney, North Platte and York.

Nebraska Medicine – like many hospitals across the state – relies on UNMC to grow our health care workforce and on students like Schultis.

“Medical students just like me, from rural communities throughout Nebraska, are getting their education at UNMC and training at Nebraska Medicine,” she says. “And like me, they’ll be going home to provide much-needed care.”

While expanding Nebraska’s health workforce is crucial, it’s only one step UNMC and Nebraska Medicine are taking in and across Nebraska. Explore this “once-in-a-generation” opportunity for Nebraska at unmc.edu/next.

Equipping the Huskers, pg. 22

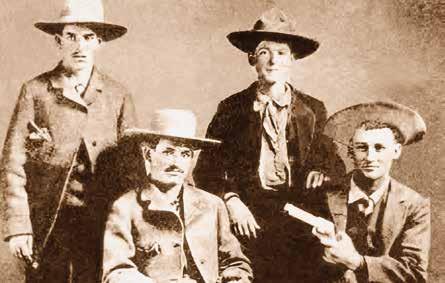

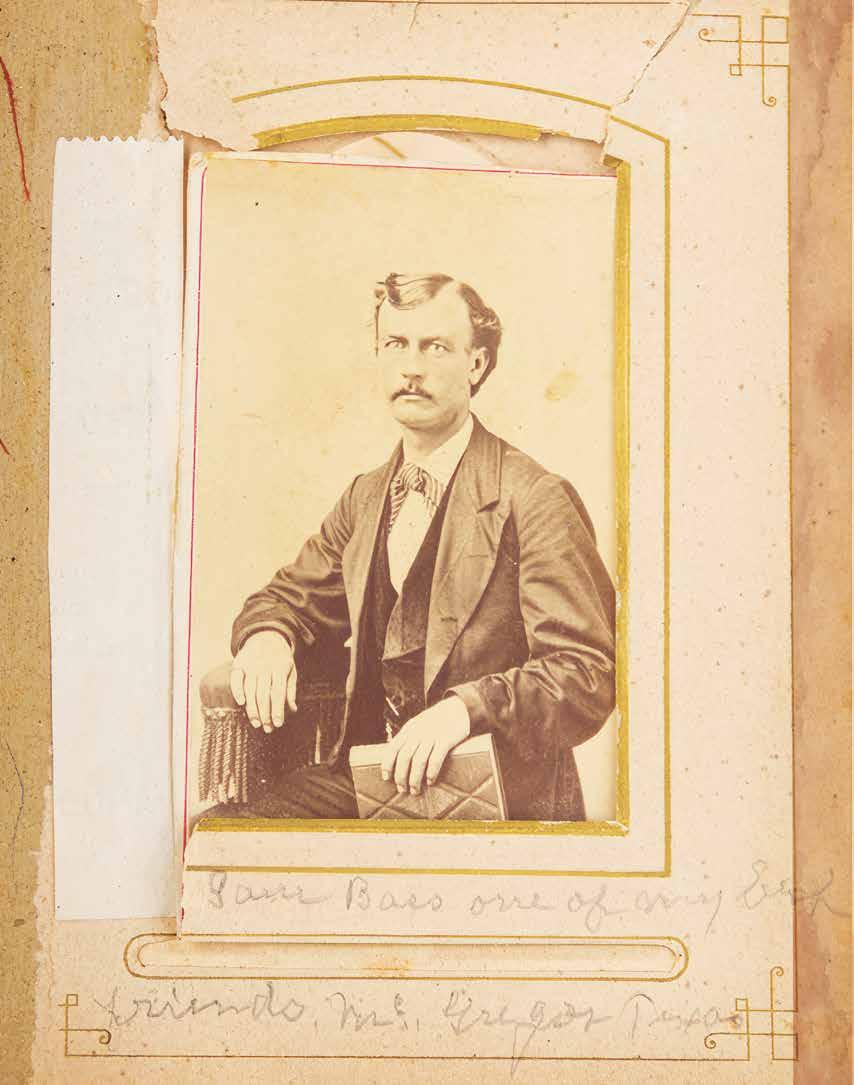

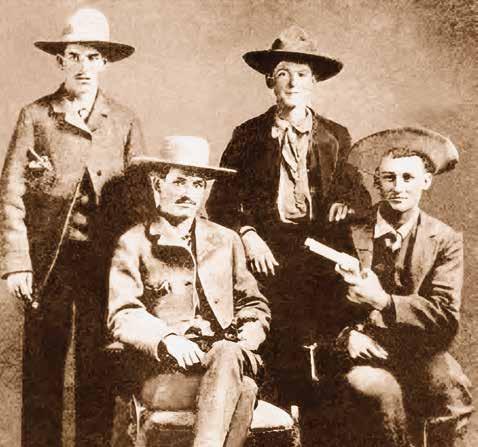

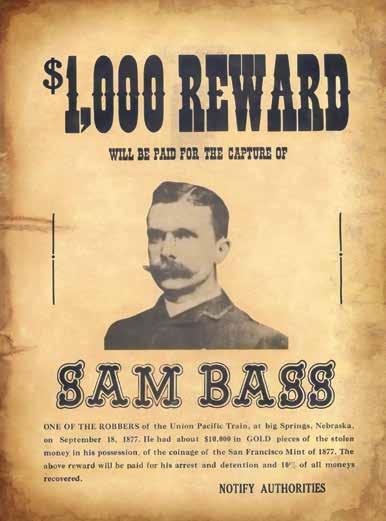

Outlaw Sam Bass, pg. 30

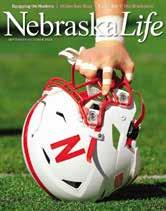

22 Equipping the Huskers

Behind-the-scenes at the University of NebraskaLincoln, equipment managers ready Husker teams for practice, game day and travel. story by Brady Oltmans photographs by Jeremy Buss

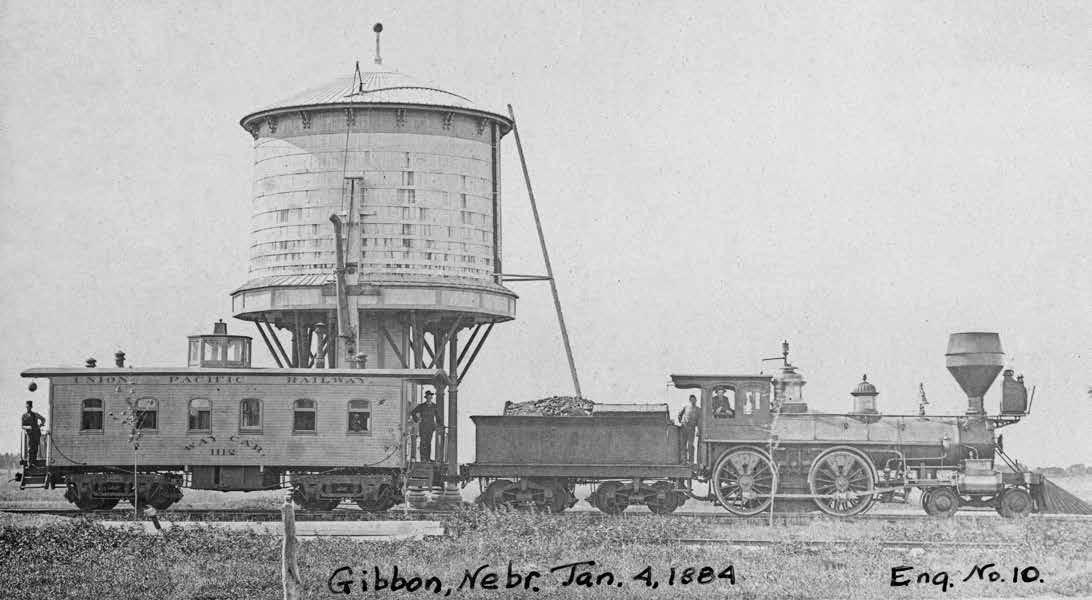

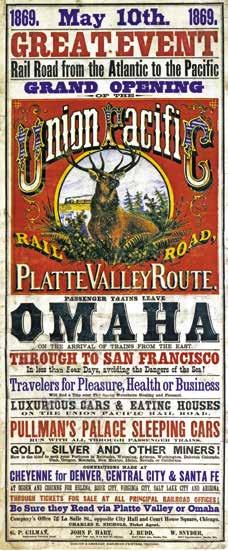

30 Outlaw Sam Bass

After a successful $60,000 haul in Big Springs, Sam Bass and his crew faced off against the law, unknowingly betrayed by one of their own. by Ron J. Jackson, Jr.

46 Buck’s Bar

Venice’s only bar brings big crowds as new musicians and talented artists perform each weekend. story by Jackie Fox photographs by Jeremy Buss

60 Photographer Don Brockmeier

For over 40 years, photographer Don Brockmeier has found serenity as he documents Frontier County wildlife and nature near his home in Eustis. story by Tom Hess photographs by Don Brockmeier

Photographer Don Brockmeier, pg. 60

10 Mailbox

Letters, emails, posts and notes from our readers.

12 Flat Water News

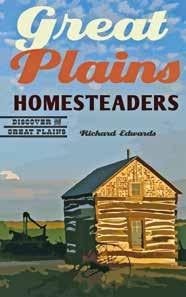

Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha reopens as Nebraska’s largest art museum; A Merna artist trades piano keys for a paintbrush; The newest book in the Discover the Great Plains series focuses on the history and legacy of homesteading.

18 Trivia

Have no fear and creep toward these questions about horror movies, books and sightings in Nebraska. Answers on page 55.

20 Storyteller

A Nebraska Life reader from Arthur County tells of life on her ranch and one particular, never-ending goat fence. Learn how you can be published, too.

40 Kitchens

Every fall soup, stew and cookout deserve a hearty cornbread companion. Try these savory and sweet recipes to spice up your meals.

44 Poetry

Our poets share their love for the land and fertile grounds that they tend and cherish, from gardens to harvesting to family and legacy.

52 Traveler

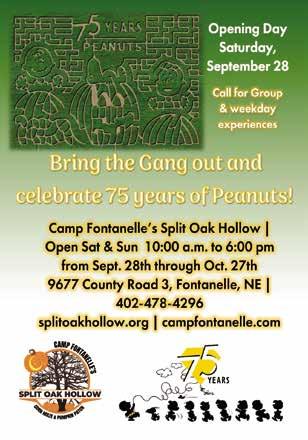

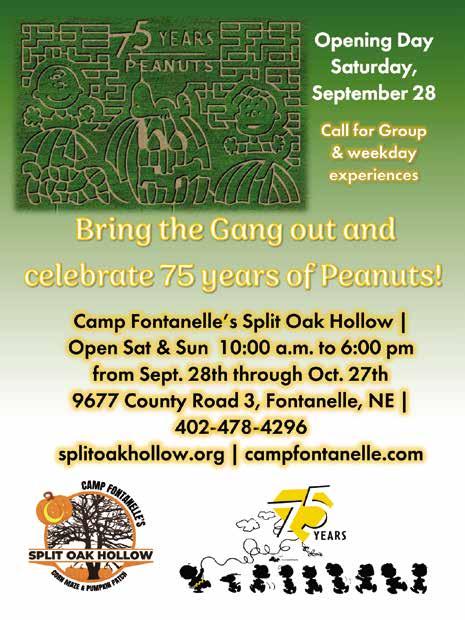

Lincoln celebrates Johnny Carson’s 99th birthday with a full night of performances; Camp Fontanelle’s nine-acre corn maze honors the 75th anniversary of Peanuts with pumpkins, wagon rides, zip lines and more.

66 Naturally Nebraska

Alan J. Bartels doesn’t hesitate to smile at happy cows on his drives across the state, even lending a hand for an unexpected delivery.

ON OUR COVER

On and off the field, equipment managers and their teams work hard to ensure Husker athletes are ready for game day. Story starts on page 22.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2024

Volume 28, Number 5

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Production Assistants

Victoria Finlayson

Lauren Warring

Design

Jennifer Stevens

Mark Del Rosario

John Anton Sisbreño

Tim Parks

Senior Editor

Tom Hess

Advertising Sales

Karla Steele

Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Carol Butler

Janice Sudbeck

Nebraska Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130 Fort Collins, CO 80527 1-800-777-6159 NebraskaLife.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit NebraskaLife.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@nebraskalife.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@nebraskalife.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@nebraskalife.com, or visiting NebraskaLife.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2024 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@nebraskalife.com.

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Editor’s reply: Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis

nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Name City

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Name City

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco

Name City

Send your letters and emails by Oct. 1, 2024, for possible publication in the next issue. One lucky winner selected at random will receive a free 1-year subscription renewal. This issue’s winner is Hank Schwartz of Falls City. Email editor@nebraskalife.com or write by mail to the address at the front of this magazine. Thanks for reading and subscribing!

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Name City

Lorem ipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Name City

BY LISA TRUESDALE

After nearly two and a half years of being closed for renovations, the Joslyn Art Museum in downtown Omaha reopened on Sept. 10. Though it cost an estimated $100 million to build a new pavilion, add a 3-acre sculpture garden and acquire more than 100 new works for the collection, general admission is still free for everyone. That’s just how Sarah Joslyn would have wanted it. She and her husband, George, a successful Omaha businessman at the turn of the 20th century, were well known for their philanthropy that supported a variety of causes. They donated to child and animal welfare, nature preservation, higher education and more; it’s estimated that they donated $7 million towards the arts alone.

George died in 1916, and in 1928, Sarah gave the City of Omaha another $3 million, this time to fund the Joslyn Memorial, a cultural center intended to

Nic Lehoux, Joslyn Art Museum

help make the arts accessible to all. The building featured a concert hall, and galleries filled with artwork donated by private collectors. From the center’s opening in 1931 to Sarah’s death in 1940 at age 88, Sarah spent much of her time in the building’s reception room, greeting visitors to the center.

The original Art Deco building, heralded in the 1930s as one of the nation’s grandest buildings, remains an integral part of the museum’s campus. The Joslyn Memorial was renamed the Joslyn Art Museum in 1987, and it was expanded in 1994 to include the Suzanne & Walter Scott Pavilion.

Now, the new Rhonda & Howard Hawks Pavilion adds another 42,000 square feet, including gathering spaces, art-class studios and 16,000 square feet of gallery space. The museum is now comprised of three distinct yet separate buildings, including a new outdoor space with 22 sculptures set among winding paths

lined with native plants. It is now the largest art museum in Nebraska.

The inaugural exhibition in the Hawks Pavilion showcases 52 paintings from the Phillip G. Schrager Collection, including works by Roy Lichtenstein, Richard Diebenkorn and Richard Artschwager. A commission by Dyani White Hawk, Wopila | Lineage III, 2023-24, is a shimmering, beautifully beaded painting crafted with nearly half a million glass bugle beads, woven into strips by a team of Native American woodworkers. The six hourglass-shaped symbols “represent the Lakota aesthetic and spiritual concept of balance between the cosmos and the earthly realm,” according to the artist.

If you can’t make it to the museum in person, or want a preview before your visit, download the free Bloomberg Connects app, which includes a free digital guide to not only Joslyn Art Museum but also more than 550 other museums around the world.

BY LISA TRUESDALE

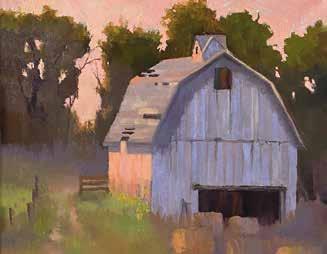

Like many artists, Beth Cole is quick to give partial credit for her success to her family, her friends, her faith and everyone who has ever purchased one of her oil paintings. Yet the true passion behind her work comes from her years of playing the piano, beginning at a young age.

“Piano was my first art form and remains a faithful friend to this day,” said Cole, who grew up on a wheat farm in Chappell and now lives in the tiny village of Merna in Custer County. “I give piano the credit for helping me learn the value of practice. I was disciplined and, in turn, I was able to see the payoff.” She approached her journey into painting in the same way, knowing that she would need many hours of study and practice.

Cole began painting in 2012, mostly

through online workshops. After gaining a few years of practice and experience, she switched to in-person workshops where she was able to learn from other artists.

When painting her muted, almost ethereal landscapes, Cole’s approach is to simplify what she’s seeing to create a peaceful, calming piece of art for others to view and enjoy. Playing the piano all those years helped with that, too. “It taught me when to use a delicate touch and when to use speed and force,” she explained. “In the same way, my painting gestures and brushstrokes communicate a certain energy or calmness.”

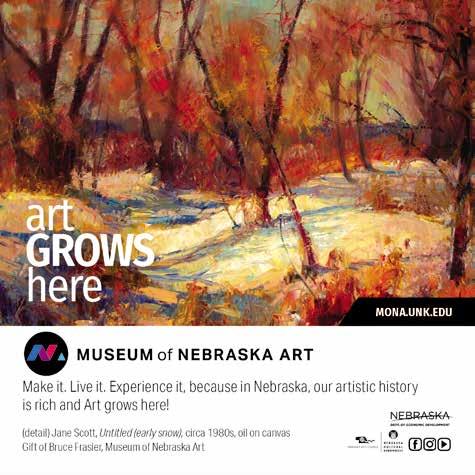

Cole’s works have earned accolades and awards all over the state, connecting her with people around the country and the world. “Subtle Shifts,” a painting of the morning sky, lives at the Museum of Nebraska Art in Kearney, after receiving

the MONA purchase award via the Association of Nebraska Art Clubs. (MONA is currently closed for renovations, but the collection can be viewed online.)

“The Golden Hour,” a studio painting of a barn Cole created based on a plein study, hangs at Bryan Medical Center in Lincoln, in honor of a retired board member. Cole also teaches her own in-person workshops now, including one at MONA next March after the museum reopens.

As for her ability to convey feelings in her paintings, Cole credits her pianoplaying for that, too. “Sometimes my emotions are strong and I can’t find the words to talk about things. Piano helped me process those feelings that I couldn’t articulate. Painting is like that, too; it helps me speak without saying a word.”

www.bethcoleart.com

BY LISA TRUESDALE

Under the Homestead Act of 1862, any U.S. citizen over 21, including single women and freed slaves, could acquire a quarter section of land on the Great Plains. They only had to pay a filing fee of $10 – a little over $300 in today’s dollars – for 160 acres. Then, they were simply required to live on the land for at least five years, build a dwelling and farm the land. After five years, they would be granted full title to their acreage.

Sounds like a no-brainer, right? Solomon D. Butcher thought so. The Nebraska resident filed a homestead claim in eastern Custer County in 1888 and got right to work – and lasted all of two weeks. Apparently, it was too hot, too buggy and too dirty for him.

In Great Plains Homesteaders, Richard Edwards tells Butcher’s story among other stories of failure and success throughout 10 chapters that explore the history, impact and legacy of homesteading. The book is ninth in a series called Discover the Great Plains, which also includes Great Plains Geology (2017), Great Plains Birds (2019) and Great Plains Forts (2023).

Edwards, director emeritus of the Center for Great Plains Studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, dives deep into the history of homesteading on the Great Plains, which stretch across a swath of North America that includes Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Colorado, Wyoming, Minnesota, South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana and three Canadian provinces. He begins with the origins of such an idea, tracing it all the way back to Julius Caesar. He also makes it clear that the land being offered up was all land the government forcefully took away from Indigenous peoples.

In a text peppered with engaging graphs, maps, illustrations and photos, Edwards discusses the many perils of homesteading including dangerous rattlesnakes, thunderstorms powerful enough to obliterate crops, blizzards that trapped farmers in the field without warning, prairie fires and grasshoppers.

He dedicates a full chapter to Black homesteaders and another to women homesteaders. He ends with a chapter called “The Homesteaders’ Legacy”; though homesteading was largely over by the late 1920s (and officially ended in 1976), many of its effects are apparent today.

“By plowing the prairie, the homesteaders transformed the Great Plains into a food-producing colossus,” Edwards wrote. “Homesteading created a society of small property holders that was much more egalitarian than our modern urban culture is, with its wide divisions between the rich and poor. It prompted neighbors to work together and make decisions together concerning matters that affected them all.”

As for Butcher? Although he failed at homesteading, he became a well-known photographer, spending the next four decades chronicling the saga of homesteading, mostly in central Nebraska’s Custer, Buffalo, Dawson and Cherry counties. His more than 3,000 powerful images are now available for viewing online, thanks to the Nebraska State Historical Society.

Great Plains Homesteaders by Richard Edwards

Bison Books/The University of Nebraska Press 192 pp, paperback, $18

Communities throughout Nebraska receive care from health care providers educated with us.

If you’re getting health care anywhere in Nebraska, there’s a good chance your provider was educated at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, and trained with Nebraska Medicine. We’re proud of the knowledge and training we provide countless health care professionals, who settle in communities throughout our state and improve the lives of people and their families.

Learn more about how we’re transforming the lives of Nebraskans at unmc.edu/next.

Relax

Look

May-Sept.: Daily, 1-6 p.m.; Friday, 1-8 p.m. Oct-April: Friday-Sunday, 1-5 p.m.

Check ourwebsite and Facebook forwinter hours.

An Estate of Fine Wine feather-river.com • 308-696-0 078 5700 SE State Farm Rd • North Platte

1

In Stephen King’s Children of the Corn, what’s the name of the child who orchestrates the children of Gatlin, a fictional Nebraska town, to sacrifice the adults to “He Who Walks Behind the Rows?” Somewhat appropriately, his biblical namesake was nearly sacrificed.

2

Former state senator Colby Coash played Mr. Janson in a Nebraska-set film titled for the legacy of what Long Island village? Dozens of films have been named after the settlement, going back to as early as 1979.

3

In Halloween III: Season of the Witch, a TV commercial threatens to kill people who wear what item? A montage features a child in Omaha wearing one while riding a bike, which sounds unsafe.

4 Brett Simmons, the director of Nebraska-set horror flick Husk described the film’s cornfielddwelling villains as “predators in their natural habitat.” What normally inanimate objects attack the movie’s helpless motorists?

5 The critically panned 2007 movie The Reaping features a small town in Louisiana facing biblical plagues. What Lincoln-born, two-time Oscar winner portrays the main character, Katherine Winter?

6

Speaking of Stephen King’s Children of the Corn, Gatlin is located near what other fictional Nebraska town, the setting of 1922 and part of The Stand, and shares its name with a real village in Western Nebraska?

a. Gurley Gulch

b. Hemingford Home

c. Melbeta Meadows

7 What 2017 horror novel by Stephanie Perkins tells the story of Makani, a high schooler who moved from Hawaiʻi to Nebraska, whose classmates start getting killed by a mysterious murderer? A film adaptation was released to Netflix in 2021.

a. Lola and the Boy Next Door

b. There’s Someone Inside Your House

c. The Woods Are Always Watching

8

What 2010 psychological thriller stars Cillian Murphy as a character with dissociative identity disorder who tries to convince the residents of a small Nebraska town that the identities are actually different people?

a. Hulu

b. Max

c. Peacock

9 July 4 of this year marked the 50th anniversary of the first sighting of what monkey-faced, bearlike cryptid in Oakland?

a. Oakland Creature

b. Oakland Monster

c. Oakland Thing

10

“Kill Switch,” an episode of The X-Files written by Hugo-winning author William Gibson, primarily takes place in the Washington, D.C., area, but the final scene reveals that the antagonist may still be on the prowl in North Platte. What is it?

a. An AI

b. A genetically-engineered supersoldier

c. A poltergeist

11 In addition to being the voice of Tony the Tiger and singing “You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch,” Norfolk-born Thurl Ravenscroft also provided the spoken word narration in Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

12 Though the titular conflict takes place in Antarctica, an early scene in Alien vs. Predator features a station in Nebraska picking up mysterious activity in Antarctica, setting the film’s events in motion.

13 Mike Bockoven’s thriller novel Pack is set in the fictional Nebraska town of Cherry, where several of the residents are secretly vampires.

14 The TV show The Walking Dead: World Beyond takes place 10 years after the start of the zombie outbreak. The show begins in Omaha and the fictional Nebraska State University, which have remained decently safe during the apocalypse.

15 Found footage horror film The Gallows takes place in director Chris Lofing’s hometown of Beatrice, though none of the scenes filmed in Beatrice made the final cut.

Visit us and discover the latest arrivals – new artists showcasing their wonderful work.

Explore the heart of Nebraska’s fine art at Main Street Gallery.

Open Wed-Sat, 10 am-5 pm or by appointment.

dynomitered.61@gmail.com

308-219-0382 • Join us on 414 1st St • North Loup, NE

Wide-open spaces and cozy campfires. Time to relax and time to work. Journey alone or become part of something bigger. That’s what you’ll find here—a small town with deep roots.

story and photographs AINSLIE WILSON

ILIVE IN AN old house on a dirt road on a ranch in the Sandhills of Arthur County with my husband (Brad), three boys (Fletch, Jake and Buck), a few chickens and too many hounds. We run mainly black cattle, Holsteins, and a really mean Jersey bull.

We also have a few goats. Brad and I may not agree on the definition of “a few,” which means all those goats need a fence to keep them from the garden.

One day in mid-summer, the sun beating down from an endless blue sky, we headed out to check cattle in our northern pastures. The horses are already wet with sweat as we top the first hill at a trot, through grass faded and brassy in the heat. There’s a breeze up here, but it turns hot and muggy as we drop into the draws.

Fletch sees a lizard and is set to bail off his horse, but I convince him to leave it: “It has a family to look after and we still have three sections to ride.”

Jake heads west at a long trot on Sombrero to check the big solar well and can be heard in the distance, singing, “Don’t shoot! It’s a man on a buffalo.” As he came out of the next draw, his song becomes, “Don’t shoot, ’cause my horse is better than yours.”

Though it is already 88 degrees, the boys are happy to ride this morning because the other option is to build the goat fence, which is almost done after weeks of early mornings to beat the heat. Even so, the mention of the goat fence elicits groans of, “I’m never building a goat fence ever again ...” as they roll out of bed.

The cows and calves are all in the lake at the east end, belly deep in water and surrounded by tall grass and reeds, lazily swatting flies and content until the sun drops. The horses are hot and thirsty and bury their noses in the tank, slurping noisily around their bits. The boys hop off, drink from the lead pipe and douse their heads with cold water.

Brad calls on our way home to say the cows on the sections south of town are out of water, and he’s waiting on the well repairman. And Buck wants to talk – he chased a bull through a pond, his horse Hatchet laid down, and now his boots are full of water.

With the goat fence as their perspective, the other jobs on the ranch are now so much more enjoyable. There’s even a race for the side-by-side when there’s water to be checked and mineral lick to be put out.

Now we wait at the next tank. Jake shows up, his hat bent. Apparently, Sombrero spooked and threw him. “But I landed on my feet!” he said with a grin.

With our horseback chores done, everyone heads home and begins to cool off when we find out bad news from the well repairman: the south well is full of sand and the only option is to drill a new one.

That means moving the cows.

It’s 5:30 p.m., and we saddle fresh horses and load up.

Storm clouds are building to the west. The wind has picked up. We split up to circle the pasture and send the cattle toward the old windmill that no longer pumps water, then on up the hill through the gate.

Brad tries to count the cattle, but between the wind whipping through the valleys and the young cow dog, Tess, doing her job very enthusiastically, the cows mill around and bellow, making it impossible.

By the time he does get them counted and on their way to water, we can see lightening and hear thunder. We’re on the highest peak of the ranch.

Fletch loses his hat, and Buck says he feels a drop of rain. “We’re gonna get soaked!” he shouts. We leave the cows on water and head down the hill, skirting around draws and washouts.

We get back to the trailer and Brad looks at the time. “It’s only 8:30 boys – there’s still some daylight left. Enough time to build some goat fence when we get home.”

“Nooo!”

story by BRADY OLTMANS

photographs by JEREMY BUSS

ERIN SMITH KEEPS a box of toddler essentials conveniently tucked under her desk, inside the heart of the Bob Devaney Sports Center in Lincoln. It’s loaded with everything washable and reusable that a working mother could want. Toys, wipes, towels, cups and long-forgotten goodies are buried underneath.

She considers herself immensely lucky that her 18-month-old son, Jaylen, gets to join her at work. Her husband, Tanner, works retail hours for Verizon. She works sports hours – long and unconventional. So, Jaylen sometimes gets in the car,

walks the winding hallways inside Devaney and joins his mother in a cathedral of sports gear.

Jaylen loves it. He gets a massive space to run and play in. That crate at his mother’s desk is his home base. The rest is a massive room full of athletic apparel. Red lockers filled with dirty and clean clothes cover most of the walls. Jerseys, shorts, shoes, tank tops, socks – even shoestrings for 11 of Nebraska’s varsity sports teams – lie either neatly folded or hang in the lockers.

Smith is one of five equipment man-

agers at the University of NebraskaLincoln. She oversees equipment for the Husker volleyball, women’s basketball, track and cross-country programs. While Nebraska football takes a much larger operation inside the new Osborne Legacy Complex and Memorial Stadium, Smith runs daily equipment checkouts and laundry for the sports she oversees. Athletes come to her for gear and guidance only to light up when they see Jaylen. That’s when the demands of the job dissipate, and she becomes a guardian inside a cozy Husker athletics community.

“Say, if I have staff who need something, if I’ve also got a kid who needs something I will drop (the staff member),” she laughed. “Because this kid is the one that’s out there doing the thing.

“The relationships. That’s the most rewarding part.”

Stars aligned – and realigned – for Smith to work in Lincoln. She grew up in Wichita, Kan., as a soccer player alongside her twin sister, Abby. They both played at Wichita Northwest High School and even in college at Missouri Western State University. Her roster profile said she’d like to become a director of basketball operations – and have dinner with former Nebraska football coach Bo Pelini.

She started her equipment journey at Missouri Western by helping with laundry for the baseball and football teams. Her mother would say Smith’s path to where she is now started much earlier.

“You’re going to pick a school by what’s in their bookstore,” she’d tease her daughter. “The t-shirts and the sweatshirts.”

At the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, equipment managers and their team ensure players have what they need for practice and game days. If a helmet becomes damaged, no matter how minor, the helmet is replaced. Every part is inspected before it is taken to the field.

Smith always liked gear. She immediately applied to graduate school after getting a degree in recreation sports management from Missouri Western. She dove into one of two equipment positions at Wichita State University, even helping log the school’s first inventory system. Thousands of items – differentiated by articles of clothing and size –

logged across all sports.

She arrived in Nebraska after leaving a two-year internship at the University of Connecticut after five months. Someone she knew from Wichita State moved to Nebraska and passed along a job. Smith joined the Husker equipment department in 2015.

In 2018, her husband accepted a new

position in Iowa. She resigned and started working in retail for a year. That wasn’t for her. Then she saw the person who replaced her at Nebraska left.

“So, I applied again and (assistant athletic director for equipment operations) Jay (Terry) took me back,” Smith smiled. “The kids were happy to have me back. It’s nice to build those relationships with athletes. They can just come down and sit for a minute. The Ralfzen twins came down and hung out, it was so fun.”

She officially rejoined the staff in July 2019. It’s been hectic ever since.

It is a running joke between equipment managers to ask, “What summer?” when athletes ask how their summers went. Smith called September her “ramp-up” time. Volleyball has its stranglehold on her schedule with daily practices and home invitationals. In addition to Nebraska, she makes sure visiting volleyball teams are accommodated when at Devaney. She also runs checkouts for track and cross-country teams four days a week.

October, November and December are what she calls her “I don’t know what day it is” time. Women’s basketball and volleyball seasons overlap. Track begins. If the Nebraska volleyball team makes a top four seed, it would host matches on the first and second weekends of the NCAA Tournament. A theoretical week would then involve a basketball game on Wednesday, volleyball on Thursday, track meet on Friday, volleyball again on Saturday and basketball on Sunday.

“You take your moments to sit and breathe but just knowing that we are bouncing between here and Pinnacle Bank Arena and getting everyone ready for travel, practices and making sure all the kids have what we need,” she explained.

An in-season sport gets priority. Smith said she will text athletes to let them know when her schedule has slight openings so they can see her when they can. Hundreds come to her for their game uniforms, practice warmups, coordinated travel gear and anything else they could need for game day. Equipment managers ensure the athletes and coaches are prepared. A mistake would be disastrous.

With the introduction of Name, Image and Likeness, equipment managers help

coordinate equipment for photoshoots involving athletes. It is another new wrinkle in the ways equipment managers are essential to Husker sports.

“You’re not the shining star. That’s not ever what we want or need to be,” she said. “But we just kind of navigate all of that and know that we’re here to be the support and we don’t need to be center stage.”

AS SMITH HAS REALIZED, Husker athletes truly are shining stars. She’ll never forget when she dug out a No. 26 jersey for Lauren Strivins to wear for a red-white scrimmage after she had already graduated. Smith was near Strivins after the match when a middle-aged woman shook hands with Strivins. That woman turned to her

friends with her hand shaking of excitement and bewilderment.

It’s the same look children get when meeting the team during the annual fan day. Husker diehards started lining up for this year’s event at 5 a.m. to get pictures and autographs with the team.

“Coming from not Nebraska, y’all are crazy,” Smith said. “The support, you real-

ly don’t get it anywhere else.”

Husker fans have sold out Devaney Sports Center and Memorial Stadium through seating expansions of both venues for over 300 straight games each. But the logistical differences between arranging the two sports are astonishing.

Jay Terry, the man who hired Smith back, has been the head equipment manager since 2002. The Cozad native leads a dedicated team of five full-time equipment managers that maintains the football locker room, ensures communication

equipment and transports all football equipment for road games.

Terry and his staff ensure each pad, sock and jersey are perfectly tallied for nearly 150 football players. They maintain apparel and communication equipment among a few dozen coaches. They sort equipment by numbers in the background to ensure every locker inside the 315,000-squarefoot Osborne Legacy Complex is pristine. Head coach Matt Rhule’s large backroom staff also moved from the north end of Memorial Stadium into the new state-of-

the-art complex.

For road games, they load each piece of equipment into a semi that needs to leave at a set time to arrive at the opposing stadium at least a day in advance. Every item is numbered and curated.

“That truck is nuts,” Smith said. “I’ve seen them packing it and the checklist and how they plan is nuts.”

The same detail applies to the work schedule. Their training camp schedule is pinpointed down to the minute from 7:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Each entry in

the schedule is meant to ensure a seamless operation come game day. Yet, their hours are unnoticed by the public. The only times Terry makes national television is if the camera captures Rhule handing off his radio equipment to the Cozad native at the end of the game.

That’s fine for Smith. It’s just part of the job. Sure, she has separate monthly and weekly calendars at her desk with entries in eight colors denoting a different sport or personal appointment. If the Huskers want equipment for 2025, she needs to order it this October. Those needs are arranged in binders and folders across her desk – above her son’s crate in the corner.

“You try to be able to take that family time and still balance when you can,” she said. “Even with that you know it’s going to be more job-heavy than life-heavy.”

But they aren’t always exclusive. Nebraska volleyball standout Harper Murray likes to carry Jaylen when he’s courtside, sometimes even after matches. Jaylen came with his mother to Devaney in early September for a tournament. The first match didn’t involve Nebraska. A quiet-to-loud turn from the scattered crowd startled him. But when the Huskers played after, Jaylen stood in the player tunnel unphased by the imposing cheers of Nebraska fans.

He even added his own cheers, pitching in support for the athletic department family he’s raised in.

“He’s already in it,” Smith said. “He’s already that fan. The fans are always so loud and that’s just normal for him.”

Outlaws steal over $60,000 in the Union Pacific’s greatest railroad robbery

by RON J. JACKSON, JR.

Fillmore Leech certainly didn’t look the part of a manhunter. He offered an unassuming appearance as a short, wiry gentleman who wore old shoes, ragged pantaloons, a new hat, and a loose coat with the tails crudely cut off. Although hidden under his coat he carried a .45-caliber pistol and two belts full of cartridges, and to one observer, there was the unmistakable “brilliancy of his eyes.”

Leech put those eyes to use – and his life on the line – on the evening of Sept. 22, 1877, while single-handedly tracking a gang of outlaws. Four days earlier, the gang executed the greatest heist in Union Pacific Railroad history. The bandits stole $60,000 in freshly minted gold coins from the San Francisco Mint, as well as lifting another $1,300 from a stunned lot of the train’s passengers. The robbery occurred at a desolate railroad depot in the far western reaches of the Nebraska prairie called Big Springs, a station 21 miles west of Ogallala and 350 miles west of Omaha.

A frenzy of telegraph dispatches went out in the immediate aftermath, which ignited a massive manhunt that included railroad detectives, regional lawmen, U.S. soldiers, and private citizens enticed by the $10,000 reward. Beyond speculation, no one knew the identity of the outlaws, the total number of gang members, or even which direction they were fleeing. In fact, no one had knowingly even laid eyes on any of the robbers since they departed Big Springs.

Leech would change everything. E.M. Morsman, Union Pacific Railroad Express Company superintendent, hired the 27-year-old on a hunch. Leech, who once investigated moonshiners in Tennessee, had already taken it upon himself to survey the scene of the crime at Big Springs before ever meeting the railroad executive. The shopkeeper also knew most people in the region and was intimately familiar with the countryside from various hunting excursions. Morsman was sold on Leech, who soon proved his worth. He trailed the band of ruffians to a camp in a thicket on the

Republican River a few miles from the Nebraska-Kansas state line.

“I was 24 hours behind them, but as they rode in a body, I had no trouble with their trail,” Leech told The New York Times in 1895. “I made 60 miles that day and about 11 o’clock p.m. came upon them on the bank of the Republican River.”

Tying his horse down at a safe distance, Leech cautiously approached the camp until he could draw no closer for fear of giving himself away. He then waited, hoping the bandits would fall asleep. Hours passed. Once he heard no noise, he made a decision that was not only bold but bordered on reckless. He began to crawl on his hands and knees in complete darkness until he found himself within feet of the camp. There, in the glow of a campfire, he scanned the scene to note every detail.

Leech instantly recognized four of the six outlaws – Joel Collins, Jim Berry, Sam Bass and Bill Potts, who sometimes used the aliases Bill Heffridge or Bill Heffery. A posse led by Sheriff Asa Bradley of North Platte may have been the first to discover the gang’s trail near Big Springs, where the bandits brazenly journeyed to buy supplies after the robbery. They buried their gold somewhere on the trail before entering town. Bradley and his men later found an empty, iron-clad strongbox that once held a batch of gold coins, half a handkerchief, an old pocketbook, and a tobacco box left by the outlaws about 10 miles from Big Springs.

Leech traced the piece of handkerchief to a store in Ogallala, where he also located the gang’s camp nearby with a distinctive boot print – one that belonged to a new pair of boots he sold Collins, who purchased them on behalf of Berry. Leech remembered how he refused to sell Berry the boots on credit because of his nefarious reputation around town.

Now Leech confirmed that both men were involved. If that wasn’t enough, he also spotted a large, seamless grain bag sitting in the middle of the gang’s camp. Leech instantly suspected the bag held the stolen gold coins. Or, at least, a portion of them. Curiosity drove him to lift the bag, and although he admitted to never seeing one coin, had no doubt as to the bag’s content based on its extraordinary weight.

Leech decided to tempt death no further. He crept out of camp, retrieved his horse, and waited for daybreak before he continued to trail the gang. The next day he employed a local ranch hand to report his findings to the Union Pacific officials in Ogallala. Telegraph messages were again sent with urgency, now with the identity of several gang members based on Leech’s daring exploits.

The outlaws, meanwhile, traveled oblivious to the fact they were no longer unknown. They divided the loot into $10,000 parcels and headed in pairs in three different directions. Yet, throughout the region, a prolific manhunt closed in on them with lawmen hellbent on making them pay for their deeds. As for the bandits, they parted ways thinking they had pulled off the perfect crime.

But did they?

Union Pacific station agent and telegraph operator George W. Barnhardt glanced at the cloudless sky and noticed how the moon shone brightly upon the

prairie. The agent manned the lone

ly outpost, which consisted of a depot, a water tank, his house, and separate quarters for the railroad section hands. As 10 p.m. approached, Barnhardt waited for the eastward bound Union Pacific express No. 4 to pass en route from San Francisco to Chicago.

As usual, all appeared quiet and peaceful.

Barnhardt then turned in his small office only to see the barrels of four cocked revolvers staring back at him. Two masked bandits – each with both hands filled with a revolver – ordered the station agent to destroy the telegraph instruments. He initially tried to deceive the outlaws by pulling up his sounder, which wouldn’t render the telegraph inoperable.

“Hold on there!” one gunman squawked authoritatively. “That won’t do. We don’t want any damned foolishness in this business.”

Barnhardt obeyed. The gunmen ordered him to hang out the mail bag and red light, which signaled the engineer to stop the train. Engineer George W. Vrooman pulled the No. 4 into the depot

at 10:40 p.m., shutting off the steam and reversing the engine. As the train slowed to a halt, two masked men pointed rifles at him. Thinking it was a joke, he stooped to pick up a piece of coal to chuck at the pranksters. A rifle ball whizzed past his head. Startled, Vrooman jumped down from his perch and tried to hide behind the engine, only to have another armed man point another rifle at him.

The outlaws quickly and systematically subdued the key members of the train’s crew.

Finally, they turned their attention to the express car messenger Charles Miller, who sat behind a locked door with the train safe and other valuable cargo. Miller was awakened by a knock from Barnhardt, who had a gun pointed at his head. Miller cracked the door open, just enough for Bass and Jack Davis to force their way into the car and thrust their revolvers in Miller’s face.

Bass and Davis proceeded to mercilessly beat Miller until he opened the

safe. Miller repeatedly pleaded with the outlaws, explaining that he didn’t know the combination. The more he pleaded, the more he was beaten, until he finally begged the bandits to kill him. Outside, the train’s conductor M.M. Patterson heard Miller’s cries and shouted that Miller was telling the truth. No one knew the combination. The men guarding Patterson told him to shut up.

The outlaws removed Miller from the car, but the beatings continued.

Bass and Davis frantically searched through the car’s cargo until they stumbled upon several iron-clad boxes. They asked Miller what they contained. Bleeding profusely from the head and mouth, he said he suspected they held some sort of “castings” given their hefty weight. One of the outlaws hammered at a box with an axe, revealing something that would leave them astonished.

The boxes contained $60,000 in freshly minted gold eagle coins from the San Francisco Mint. Forty-thousand dol-

lars were consigned to Wells, Fargo & Company in New York, while another $20,000 were to be delivered to the New York Bank of Commerce. In addition, the robbers found 535 silver bars worth a total of $682,476. But each bar weighed 100 pounds, rendering them too heavy to haul off.

At the same time, the outlaws demanded the passengers surrender all their money and valuables. One passenger – Andrew Riley of Omaha – saw four masked gunmen quickly approach his first-class coach with cocked revolvers. The outlaws fired twice at Riley, grazing his left hand with one shot, and piercing his coat with the other.

“Hold up your hands, every son of a bitch, and keep still,” one outlaw shouted. “We want your money, but will give each man $10 back, and we won’t hurt a man unless he makes a break. We’ve killed one man and don’t want to kill anymore, but your money we will have; so, damn you, keep still and give it up – all of it, quietly.”

Riley surrendered $480 in cash, a $300 gold watch, and a railway ticket to Chicago. Riley would later reveal to railroad agents that he recognized one of the masked outlaws as Joel Collins. Riley said he had become acquainted with Collins in the fall of 1876 in the Black Hills, where the native Texan was running a dive saloon that only attracted the dregs of society. Riley further revealed that only two weeks prior, he had smoked a cigar with Collins in Ogallala.

Leech would later confirm Riley’s suspicions as the noose tightened on the gang.

Joel Collins and Bill Potts rode into Buffalo Station, Kansas on Sept. 26, eight days after the great heist. Buffalo Station, like Big Springs, was another remote train depot on a vast prairie. Unbeknownst to Collins, his name as the gang’s ringleader had already reached the Buffalo Station agent William Sternberg via a telegraph wire.

So, by the time Collins stopped to buy a few supplies from the depot store, Sternberg took note of the writing on an envelope Collins dropped: “Joel Collins, Ogallala, Nebraska.” Sternberg instinctively, and foolishly, asked if he was Joel Collins. The outlaw hesitatingly answered in the affirmative. The agent said he thought he recognized him from a previous meeting, and then hurriedly excused himself.

Little did Collins know but Ellis County Sheriff George W. Bardsley and a posse of nine cavalrymen from Fort Hays were camped nearby, on the lookout for the bandit and his cohorts. Sternberg informed Bardsley of his encounter. Soon, the sheriff caught up with Collins and Potts and asked them to ride back to the station to answer some questions. At first, the two outlaws agreed. Then Collins sensed a trap.

“Pard, if we are to die,” Collins said to Potts, “we might as well die game.”

A shootout ensued. Bardsley shot and killed Collins, while a private rode up behind Potts and gunned him down. In a matter of seconds, two of the six train robbers had been sent to their graves. The posse recovered $19,456.67.

Twenty days later, on Oct. 16 in Mexico,

Missouri, Jim Berry died from gangrene poisoning after being shot by Audrain County Sheriff Harry Glasscock with buckshot in his left leg. Only $2,768 was recovered from Berry, who stepped off a train with Tom Nixon in Mexico on Oct. 5. Nixon then supposedly caught the first train bound for Chicago and vanished from history.

Berry, unwisely, went on a spending spree and caught the attention of local authorities.

Like Nixon, Jack Davis also mysteriously disappeared after parting with Bass in Texas. Bass himself later claimed Da-

vis ventured to New Orleans, although those might have been the lying words of a dying outlaw.

Bass met his fate in Round Rock, Texas in July 1878. By then, he had already cemented himself as an infamous outlaw. He led a gang in the aftermath of the Big Springs’ heist that successfully robbed two stagecoaches and four trains within 25 miles of Dallas during a six-month period, drawing the full attention of the vaunted Texas Rangers. His dramatic death – triggered by betrayal from within his gang –only added luster to the legend.

Bass and his comrades camped outside Round Rock, intent on robbing the Williamson County Bank on Saturday, July 21, after deposits were received on Friday. The outlaws envisioned a big score at the bank and then disappearing into Mexico. First, they scouted the town for any last-minute details that might assist them in their heist. Bass and two of his associates – Frank Jackson and Seaborn Barnes – thus rode into town on Friday one final time to surveil the bank.

Unbeknownst to Bass, Texas Rangers and local law enforcement officials were already in town, laying a trap. They had been tipped off to the prospective bank robbery by Jim Murphy, an old friend of Bass who agreed to infiltrate the gang. Murphy, somehow, managed to peel off from the threesome as they continued into town that fateful day.

Maurice B. Moore, a Travis County deputy sheriff in nearby Austin, was one of those asked to assist in the apprehension of the outlaws if the robbery unfolded. Moore agreed, adding only “if the pay is good.” Williamson County Deputy Sheriff A.W. “Caige” Grimes – an ex-Texas Ranger – was with Moore when the three desperadoes first appeared in town.

The three strangers leisurely passed the lawmen, giving them a hard stare as they entered a store. Moore thought he saw one of the strangers wearing a six-shooter under his coat. He turned to Grimes and said, “Let me go over and see.” With that, Moore and Grimes followed the three men into the store.

Grimes carelessly walked up to the men, placed a hand on Bass and asked if he had a pistol. “Yes,” Bass replied, and

Big Springs, Bass went on to rob two stagecoaches and four trains near

met his end on his 27th birthday on July 21, 1878. His

suspecting they had been discovered, all three outlaws immediately opened fire. Grimes bolted for the door with his pistol still holstered and cried, “Don’t boys!” He dropped dead outside the store, riddled by bullets.

A slug also pierced the left lung of Moore, who miraculously kept firing. One of his bullets struck Bass, taking two fingers on his right hand in the process. The crackle of gunfire instantly attracted other lawmen and townspeople as the three outlaws shot their way to a nearby alley where their horses awaited.

Trying to mount his horse, Bass received a slug from the pistol of Texas Ranger George Herold. Bass cried out, “Oh, Lord!” He had been struck from behind, near his spine. The bullet tore through a kidney and exited inches from his left navel. Jackson covered Bass while assisting his wounded leader climb aboard his horse. Nearby, a single bullet dropped Barnes dead as he tried to

mount his horse.

Jackson and Bass then rode furiously out of town. They did so as Jackson struggled to keep the badly bleeding Bass aboard his horse. A pursuit of the outlaws ensued, but the chase entered terrain marked by rocks and cedar brakes at dusk and the trail went cold.

The outlaws made it to their campsite to grab additional firearms before continuing their desperate escape. The men didn’t get more than three miles from their camp when Bass told Jackson he could no longer ride. No one knows what was said between the two bandits, but Jackson continued alone and disappeared from history.

Bass remained in the woods, in pain and bleeding throughout the night. A posse found him the next day, sitting beneath a tree. They approached cautiously, only to have Bass yell, “Don’t shoot! I surrender.”

The rangers summoned a doctor, who

informed Bass that his wounds were fatal. They took the outlaw back to Round Rock, laid him on a cot in a shack, fed him and made him as comfortable as possible. Repeated attempts to entice Bass to relate the activities of his gang proved futile. He remained tight-lipped until the end. The next day – Sunday, July 21, 1878 – Bass drew his last breath at 3:55 p.m. on his 27th birthday.

Texans hailed Bass as a sort of “Robin Hood” for generously spending his stolen money with those who crossed his path. Songs and books would also later glamorize his criminal deeds.

Leech, meanwhile, became a footnote to Nebraska history – albeit one worth remembering. Due to his daring actions and whit, the shopkeeper-turned-investigator became the lynchpin in a manhunt that tracked down four of the six train robbers. His exploits alone proved those desperadoes had not pulled off the perfect crime.

BANCROFT

John G. Neihardt State Historic Site p 38

BROKEN BOW

Custer County Museum p 8

CHADRON

Museum of the Fur Trade p 38

FREMONT

Dodge County Historical Society Museum/Louis E. May Museum p 38

GOTHENBURG

Gothenburg Pony Express Station p 58

GRAND ISLAND

Stuhr Museum of the Prairie Pioneer p 37

HENDERSON

Henderson Mennonite Heritage Park p 39

KEARNEY

Museum of Nebraska Art p 37

LA VISTA

Czech and Slovak Educational Center and Cultural Museum p 38

MADISON

Madison County Museum p 38

NEBRASKA CITY

Wildwood Historic Center & Period House p 37

NORTH PLATTE

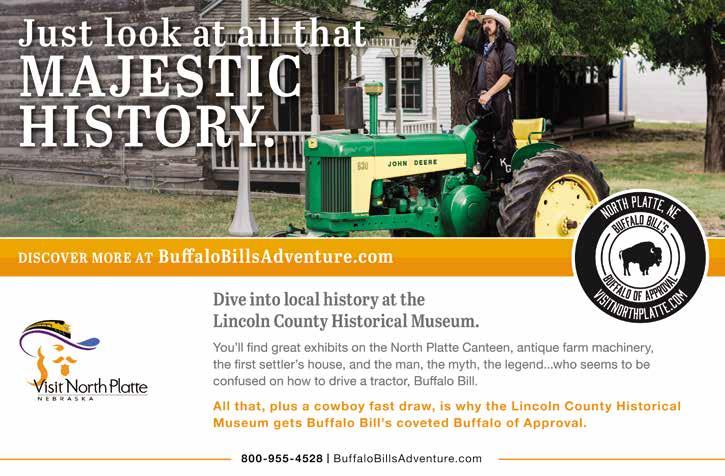

Lincoln County Historical Museum p 57

OMAHA

Durham Museum p 36

RED CLOUD

National Willa Cather Center p 56

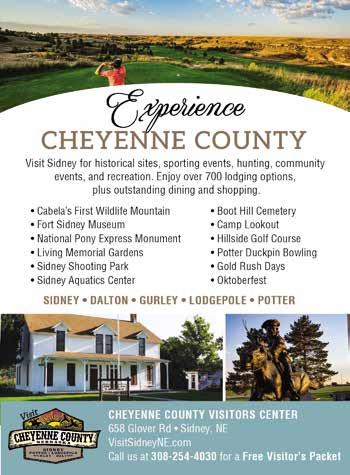

SIDNEY

Fort Sidney Museum p 58

TEKAMAH

Burt County Museum p 38

WEEPING WATER

Weeping Water Valley Historical Society/ Heritage House Museum Complex p 37

YORK

Clayton Museum of Ancient History at York University p 39

UNIQUE

John Kinzie’s gun

HBC officer’s sword

Brass handle cartouche knife

William Clark fabric samples

Chief’s coat

Kit Fox Society lance

Russian American Co. note

Oldest dated trap 1755

Parchment HBC officers certificate

Andrew Henry’s leggings

3

Celebrate the power of education with us as we spotlight the Good Cheer School, District 48, alongside 80 K-8 one-room schools and other notable institutions.

Hours: 1:30-5

Mon-Fri or call for appointment

Explore ancient Rome, the Near East and much more. Special Bible exhibit shares the story of scripture from scroll to modern translations. Children’s interactive Little Kingdom now opened!

View rare artifacts from the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia and Roman Empire! Young and old can experience the museum’s Little Kingdom interactive area. Uncover objects in an archaeological dig, “live” in an ancient house and “shop” a Roman market. Admission is FREE with donations always accepted.

ADMISSION IS FREE Check Facebook page for hours

Open Tues-Fri, 10 am-5 pm • Sat 1-4 pm claytonmuseumofancienthistory.org

ClaytonMuseumOfAncientHistory.org

Explore our 8 1/2 acre site with its turn-of-the-century farmstead, depot, country church, and school, where stories of Henderson’s Mennonite immigrants come to life!

402-363-5748

402-363-5748 • 1125 E 8th St • York

1125 E 8th St • York, NE

Paid for in part by a grant from the York County Visitors Bureau

Paid for in part by a grant from the York County Visitors Bureau

Tue-Sat, 1-4 pm or open upon request

Lower level of the Mackey Center on the York University campus

Located in the lower level of the Mackey Center on the York College campus

Settle the cornbread controversy with bursts of fruit and a bite of spice.

recipes and photographs by DANELLE McCOLLUM

THERE’S NO NEED to settle for dry, predictable cornbread, or wonder if it’s better savory or sweet. Choose your side of the debate and compliment your autumn soups and stews with bold ingredients and pairings you might not normally think to add.

Pepper jack cheese gives this savory pumpkin bread a bit of a kick; cheddar and mozzarella make for milder alternatives. Or go the opposite direction and spice things up even more with sliced jalapeños. Serve alongside fall soups, stews and chilies.

Combine cornmeal and milk in a medium bowl; let stand for 10 minutes. In another medium bowl, combine flour, sugar, baking powder, salt and nutmeg.

Stir eggs, pumpkin and melted butter into cornmeal mixture. Mix well. Stir wet ingredients into dry ingredients. Fold in pepper jack cheese.

Pour mixture into a 10-inch cast iron skillet or lightly greased 9-inch square baking pan. Bake at 400° for 25-30 minutes or until a toothpick comes out clean.

1 cup yellow cornmeal

1 cup milk

1 cup flour

2 Tbsp sugar

2 tsp baking powder

1 tsp salt

2 eggs, beaten

1 cup pumpkin

3 Tbsp butter, melted

1 cup shredded pepper jack cheese

Pinch of nutmeg

Serves 8-10

Cornbread can sometimes be dry, but not when your first bite of this recipe includes the burst of juice from fresh blueberries. Avoid using frozen blueberries; it will render your bread soggy.

In a large bowl, mix cornmeal, flour, sugar, baking powder and salt. Toss fresh blueberries in the dry ingredients before adding them to the batter so that they don’t sink to the bottom of the pan.

In a separate large bowl, beat eggs, buttermilk, oil and sour cream or yogurt until smooth. Add the dry ingredients and coated blueberries and mix until combined. Pour into a greased 8-inch square baking dish. Bake at 400° for 25-30 minutes, or until a toothpick comes out clean.

1 cup cornmeal

1 cup all-purpose flour

1/2 cup white sugar

1 Tbsp baking powder

1/2 tsp salt

2 cups blueberries, fresh

2 eggs

2/3 cup buttermilk

1/2 cup vegetable oil

1/3 cup sour cream or plain yogurt

Serves 8

Use cheddar or the odds and ends of cheese in your fridge to compliment the jalapeños for this tasty addition to hearty Southwestern-style soups and stews.

In a large bowl, combine the flour, cornmeal, sugar, baking powder and salt. In a separate bowl, whisk together the milk, egg, egg yolk and melted butter.

With a wooden spoon, stir the wet ingredients into the dry mixture until most of the lumps are dissolved. Don’t overmix.

Stir in 1 cup of the cheese along with the green onions and jalapeños. Allow the mixture to sit at room temperature for 10-15 minutes.

Pour the batter into a greased 9x9-inch square baking pan and smooth the top. Sprinkle with remaining cheese.

Bake at 350° for about 23 minutes, or until a toothpick comes out clean. Place on a wire rack to cool slightly before slicing and serving.

1 ½ cups flour

1/2 cup cornmeal

2 Tbsp sugar

1 Tbsp baking powder

1 tsp salt

1 cup milk

1 egg + 1 egg yolk

1/2 cup butter, melted

1 ½ cups shredded cheddar cheese

2 green onions, chopped

1 small jalapeño, seeded and finely diced

Serves 8-10

WE’RE RAVENOUS TO taste (and publish) your favorite family recipes and stories that accompany them. Send recipes and stories to kitchens@nebraskalife.com or to the address at the front of this magazine.

Nebraskans have always been connected to the land, its bounty and the soil that yields a harvest each season. Children grow up in the fields, riding atop tractors, learning to till the soil. Family farms and ranches become a generational legacy – a history of why we call Nebraska home.

Laura Hilkemann, Firth

The sun-creased farmer

In a faded, red seed-company cap

Insists it’s not dirt on his work shirt – it’s soil.

Soil initially plowed by Brownie (Great-grandpa’s bay quarter horse with four socks) Before the Kenny-Colwell tractor came from Norfolk. Rich soil that crumbles

Like the delicious chocolate cake

In his granddaughter’s fists on her first birthday.

Soil comprising the precise ingredients for life itself

Eagerly awaiting forthcoming recipes. No, it’s definitely not dirt – it’s soil.

Duane Anderson, La Vista

A prairie blanket of golden black earth, fresh clear water from a newly fallen rain, a brightly lit sun shining high in the sky, and one little seed, bringing a new birth to our earth.

Steven M. Lukas, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Too many kids and too few acres drove us to seek our fortunes elsewhere. But when diminished by the cold hardness of concrete corporate conference rooms, I return to the land to be replenished.

I come back to drive the Bohemian mountains tops, to wander down low-maintenance byways, until I can stand behind the old farmhouse and hear the howl of gusts in long-needled pines.

I wander down the pasture lane and remember our plodding of a small herd of milk cows we knew by name.

I listen for the rustle of wildlife in protective plum thickets along fence lines.

I am serenaded by evening choruses of Meadowlarks from their stage on weathered fence posts.

I inhale deeply the richness of fresh turned earth where roots are still being made.

Finally, I come to that quiet corner surrounded by rows of rustling green sentinels and offer a windborne prayer of thanksgiving and love over those who came before, who stayed and gave it their all, so all this could be given to me.

Vaughn Neeld, Cañon City, Colorado

Along the far horizon, the sun dips behind a sea of green-leafed corn whose blades shake silver edges as a slight breeze ripples through the fields.

Distant cumulus clouds display a parade of colors –blue, yellow, rose, lilac –transitioning to gold-red before bleeding into a cloud mountain of rippling red.

Tomorrow the sun will rise to the east over the yellow tassels of ripening grain glistening yellow within husks of green; the land lying breathless beneath a banner of billowing clouds.

Dennis C. Radil, Comstock

To find the path that’s been less trod Takes up our time and thought; A lifetime is a precious gift Not something easily bought.

The wind blows steady treetops bend The grass now running still; Such beauty each direction seen We drink but never fill.

This moment’s dear, ne’er come again Alive our senses thrive; A buzzing bee, a pesky gnat Glad too they are alive.

The beauty in a field of corn

Spaced far to share the rain; This land when dry seems like no friend There’s only loss, no gain.

But hard times come and go away Behind a few remain; With time and decades passing slow We’re glad we stayed for rain.

August Hamilton, La Vista

When the sun comes up I’m ready Like a lion chasing its prey I ran outside with my grandpa

To go to the farm

When we got there We did work with the combine

To get corn

My grandpa was done and Dumped it into a big vehicle that Held the corn

Then I hopped into the big vehicle And played in the corn Then I played on the hay bales At my cousin’s farm

It was some of the most Fun I’ve ever had But eventually the fun ended The sun was going down And the beauty of the outdoors Was lost

SEND YOUR POEMS on the theme “Forever Love” for January/February 2025 issue, deadline Nov. 15, “Still Nights” for the March/April 2025 issue, deadline Jan. 1, and “New Beginnings” for the May/June 2025 issue, deadline Feb. 1. Email your poems to poetry@nebraskalife.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

Buck’s Bar and Grill is the go-to hub for live music performances by new and renowned artists

story by JACKIE FOX photographs by JEREMY BUSS

VENICE IS A blink-and-you’ll-miss-it village tucked between Omaha and Yutan near the Platte River. Its handful of businesses includes Buck’s Bar and Grill, which serves plentiful food at reasonable prices. Their prime rib draws families and friend groups from miles around. Taco Tuesdays are also a big draw.

This is exactly what you’d expect from a small-town dive bar that’s good at food. What you may not expect is that when the dinner crowds wind down, it transforms into a live music venue with a national reputation. Musicians from both coasts and everywhere in between want to play at this bar that’s so tiny it doesn’t even have a stage. Buck’s has gained a reputation as a launching pad, with Buck’s alumni selling out storied venues like Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium and appearing on national TV. Many have made it to the hallowed Grand Ole Opry.

That’s impressive for a bar that’s only been around since 2012. Buck Bennett never expected his business to snowball the way it did. “I wanted to have some live music, some karaoke and a little bit of food,” he said.

Bennett moved from Stratton to the Omaha area roughly 30 years ago and was drawn to the thriving ’90s country music scene. He came by his love of country music honestly as a former bareback bronc rider who took the name Buck Bennett from a Chris LeDoux lyric. (His given

name is Brad League.)

“Omaha had five big honky tonks back then and I’d go to country dance,” Bennett said. “It was cool to get to see live music that we didn’t get in Stratton.” He saw big names like LeDoux, Merle Haggard, Kenny Chesney and the Dixie Chicks at the now-defunct Guitars and Cadillacs.

Today, musicians who got their start at Buck’s give the bar shout-outs from arena shows and even show up at the bar afterward. Indie country stars Cody Jinks and Ward Davis are legendary in Buck’s circles for making

an unscheduled appearance when their large outdoor show was rained out.

More recently, up-and-comer Tanner Usrey did a pop-up show at Buck’s after opening for Dierks Bentley at Omaha’s CHI Health Center Arena. It sold out and an overflow crowd in the parking lot waited to meet him. Small venues like Buck’s provide a rare chance to get close to artists without spending hundreds of dollars for VIP meet-and-greets.

Buck’s reputation as a music mecca is only one of the things that makes it spe-

cial. Nebraska’s small-town bars serve a vital role as gathering places, and Buck’s is no exception. Friendships are forged there. Birthday parties, baby showers and celebrations of life take place there. When asked what surprises him most after more than a decade in business, Bennett said, “It’s the culture, which kind of evolved on its own.”

The best example involves Buck’s most beloved patron, the late Carl Seieroe. Carl was a Friday night fixture into his 90s. He’d arrive on his golf cart, order coffee and a meal and hold court, asking the bands to play slow songs so he could dance with the ladies. When it was time for him to leave, everyone would yell “Good night, Carl” like he was Norm at Cheers.

There were many nights when Bennett, his staff or regulars gave Carl a ride or followed him home, especially in winter. “He’d show up on that golf cart when it was 10 below,” Bennett said. Buck’s patron Neil

McAlexander shot a video inside his pickup while he followed Carl home one New Year’s Eve. It was 13 degrees, and they had to jump start Carl’s golf cart in the parking lot. “I hope when I’m over 90 years old I can be jamming at the honky tonk bar and asking all the ladies to dance,” McAlexander said in the video.

Carl died in June 2023 at age 93, and his family asked the Buck’s family to share pictures for his celebration of life. Many did and some attended his service. Quite a few didn’t even know Carl’s last name until Buck’s Facebook music group shared his obituary. As Buck’s regular Trish Ferryman noted, “Carl was epic like Cher! Only needed a first name.”

HUSKER SPORTS FEATURE prominently in Nebraska’s culture, and Buck’s follows its seasonal rhythms. It has large TVs showing Husker games, and musicians adjust as needed. Indie country

artist Jason Eady joked that he had never postponed the beginning of a set to accommodate a college volleyball game. He did at Buck’s (and the Huskers won). On football Saturdays, Bennett has learned the bar does well when the Huskers win and not great when they don’t. And if you’re a Husker football fan hoping to run into Coach Rhule somewhere, you may find the coach and music fan at Buck’s during the offseason.

Buck’s has also had to adapt to natural disasters. The massive flooding in spring 2019 covered the bar’s parking lot, stranding Bennett for a week in the RV he kept parked there. Musicians scheduled to play Buck’s were shifted to Chance Ridge in Elkhorn and the Dog House in Wahoo. Slowdown, a popular music venue in downtown Omaha, also offered their space. “Our venue is your venue,” owner Jason Kolbel told Buck. When Covid shut businesses down

in 2020, Buck’s pivoted to takeout. “We created a system where we started taking orders at 2 and started cooking at 4,” Bennett said. A silver lining was being able to stagger prep and pickup times, unlike when the doors are open and a party bus shows up. “Takeout got so popular that when we opened again, we had to stop answering the phone because it just kept ringing. Even today, don’t look for carry out on Friday or Saturday.”

Balancing the food and music sides of the business can be tricky, but it’s necessary. “I wouldn’t want to try survive just doing music,” Bennett said. “We started the Buck’s Music Facebook group because if we announce a band on the Buck’s Bar and Grill Facebook page, the food crowd won’t come.” And while music gets the lion’s share of social media attention, local foodies share praise for Buck’s food there.

“With the restaurant, you want to be proud of the product you put out, but the

music makes me happiest,” Buck said. “My business model is to have a place I want to go to and hopefully there will be other people like me.” His business model must be working, because there are plenty of people who keep coming back for Buck’s food and music.

Visit bucksbarandgrill.com to see the menu and learn more about upcoming music events. Rotating weekend menu specials are posted on their social media accounts on Facebook and Instagram. Buck’s Bar also has live performance videos on their YouTube channel and a Spotify playlist featuring all the artists who have played there.

Dinner reservations: No

Seating capacity: 85

Seated and standing capacity: 125

nwordswefindahiddenspace,Wherefeelingsweaveand timecantrace,Awhispersoft,ashoutsoclear,Poetry holdstheheart’ssincere.Itpaintstheworldinshades unseen,Givesvoicetodreamsandwhatmightbe,With rhythm’sdanceandrhyme’sembrace,Itcaptureslifeingentle grace.Ineveryline,atruthresides,Ineveryverse,the soulconfides,Forinitsart,wefindourway,Andthrough itsbeauty,nightturnsdaynwordswefindahiddenspace, Wherefeelingsweaveandtimecantrace,Awhispersoft, ashoutsoclear,Poetryholdstheheart’ssincere.Itpaints theworldinshadesunseen,Givesvoicetodreamsandwhat mightbe,Withrhythm’sdanceandrhyme’sembrace,It captureslifeingentlegrace.Ineveryline,atruthresides, Ineveryverse,thesoulconfides,Forinitsart,wefind ourway,Andthroughitsbeauty,nightturnsday

on First Tuesdays Virtual, Free, Open to the Public

Virtual Poetry Workshops are FREE to members Membership $35/year (Scholarships available on website)

Satisfy your taste buds in Burwell with hot, fresh pizza! Dine in for lunch buffets, carry out or take home from our grab-and-go freezer.

Enjoy our wines, hard ciders, craft beers and appetizers. Hike our walking trails, enjoy our creekside fire pits and stay in our quaint cottages.

308-324-0440 • macscreek.com

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

Dive into the world of nostalgia as Nebraskans celebrate what would have been Johnny Carson’s 99th birthday with a special evening of entertainment and laughter at the Lied Center for the Performing Arts. Often touted as the king of late-night television, Carson’s charm and wit captivated millions during his legendary 30year run on “The Tonight Show.” Now, fans can relive those magical moments through a star-studded lineup of variety artists who graced Carson’s stage.

Hosted by comedian Pat Hazell, the evening will commence on Oct. 23 at 7:30 p.m. Master magician Lance Burton’s mind-blowing illusions and interactive sleights-of-hand mesmerize, while ventriloquist Jay Johnson breathes life into whimsical puppets. The laughter continues with brilliantly sharp-witted comedian Cathy Ladman, and Jon Wee and Owen Morse of

The Passing Zone dazzle the audience with their juggling prowess.

Adding to the evening’s allure, enchanting jazz singer Nicole Henry will serenade audiences with her soulful voice alongside the talented UNL Jazz Orchestra, led by conductor Gregory Simon, performing original numbers from “The Tonight Show” Orchestra.

This extraordinary one-night event, produced by Carson Entertainment Group, serves as a heartfelt tribute to Johnny Carson’s enduring connection to his beloved hometown of Norfolk, which honors the very man who defined latenight entertainment.

Join fellow fans and immerse yourself in the laughter and artistry that defined an era. Experience an evening that’s sure to bring as much joy to the audience as Johnny Carson brought to America.

Contemporary culinary flair meets traditional pub at this casual outpost. The historic 130-year-old building in Lincoln’s Haymarket boasts a welcoming atmosphere, innovative dishes like a raspberry beret burger and a rotating selection of local brews and exciting cocktails. 301 N. 8th St. (402) 261-8849.

Lincoln’s first and only boutique hotel promises neoclassical architecture blended with local heritage. With luxurious, thoughtfully-designed rooms and exceptional service, unwind in comfort while enjoying craft cocktails at Boitano’s Lounge. 216 N. 11th St. (402) 261-7800.

Govenor’s Pheasant Hunt

Nov. 1-2 • Beatrice

Governor Pete Ricketts joins hunters, for the annual Pheasant Hunt. Kick off the weekend with an open shoot at Beatrice Gun Club, followed by a festive dinner. Saturday brings thrilling hunts and a sporting clay shoot, concluding with the highly anticipated Grand Champion trophy. (402) 223-3244.

Crawford Cattle Call

Nov. 2 • Chadron

Get the whole family moo’vin to Downtown Crawford for an impressive cattle corral three blocks long. Display your artistic flair with a hay bale decorating contest, enjoy a jaunt in a historic stagecoach or groove along with a medley of local musicians. 2nd St.

Frost Frolic Holiday Market

Nov. 2 • Fairbury

Now in its 34th year, shoppers explore more than 100 booths just in time for holiday shopping. Admission is only $2. Jefferson County Fairgrounds, 56885 PWF Road. (402) 300-1139.

Autumn Festival

Nov. 7-10 • Ralston