JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

ISSUE NO. 76 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

Colorado’s wild horses find solace and freedom across the 23,000 acres of the Wild Horse Refuge near Craig, part of the Wild Animal Sanctuary’s mission to protect and preserve wildlife. by Peter Moore

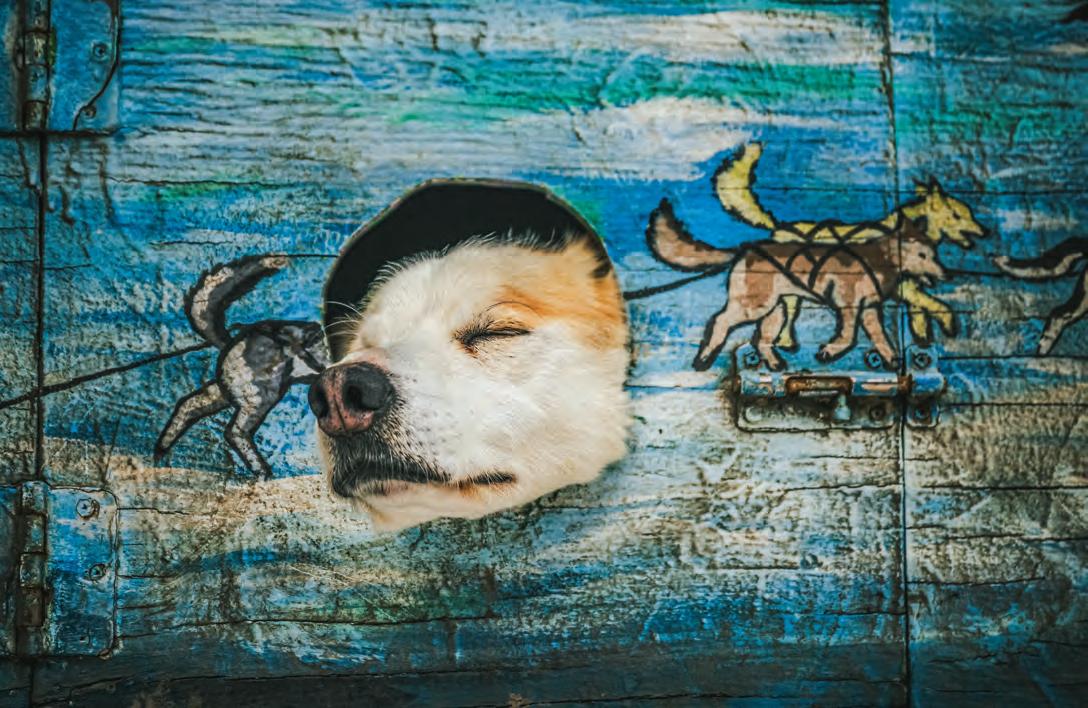

Sled dogs, mushers and skijorers race across the Grand Mesa for the annual Grand Mesa Summit Challenge, the highest altitude sled dog race in North America. story by Heidi Pool and Tom Hess photographs by Keela McCleneghan

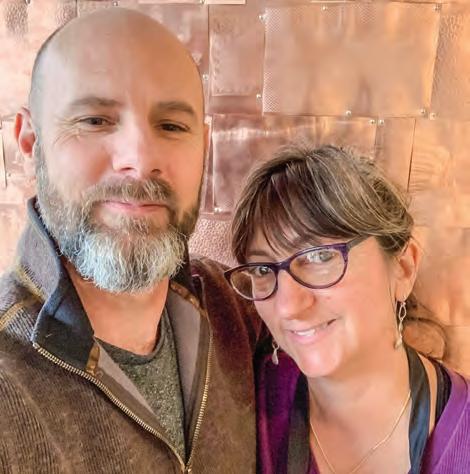

Nicole and Harry Hansen craft hand-forged jewelry and housewares, teaching guests how to make their own pieces from scratch at their shop in Salida. story by Majorie Ackerman photographs by H. Mark Weidman

48

Horses, cowboys and ski bums team up at the San Juan Skijoring competition in Ridgway. While teams come for the thrill and prize purse, crowds come to watch for victory – and wipeouts. by Tom Hess

POSTMASTER: COLORADO LIFE, ISSN ISSN 2166-3823, is published bimonthly for $30 per year by Flagship Publishing, Inc., PO Box 270130, Fort Collins, CO 80527. Periodical postage paid at Denver, CO, and at additional offices. Send address changes to Colorado Life, PO Box 270130, Fort Collins, CO 80527.

As snow falls, sled dogs prepare to race on the flattop mountain for the Grand Mesa Summit Challenge. Story begins on page 24.

PHOTOGRAPH BY

KEELA MCCLENEGHAN

10

Skiers and snowboarders say “I do” at Loveland Ski Area; Self-taught pastel artist Bruce Gómez captures the Colorado wilderness; Denverites celebrate the unofficial “303 Day.”

14 Trivia

Vote for the right answer to these political questions. Answers on page 43.

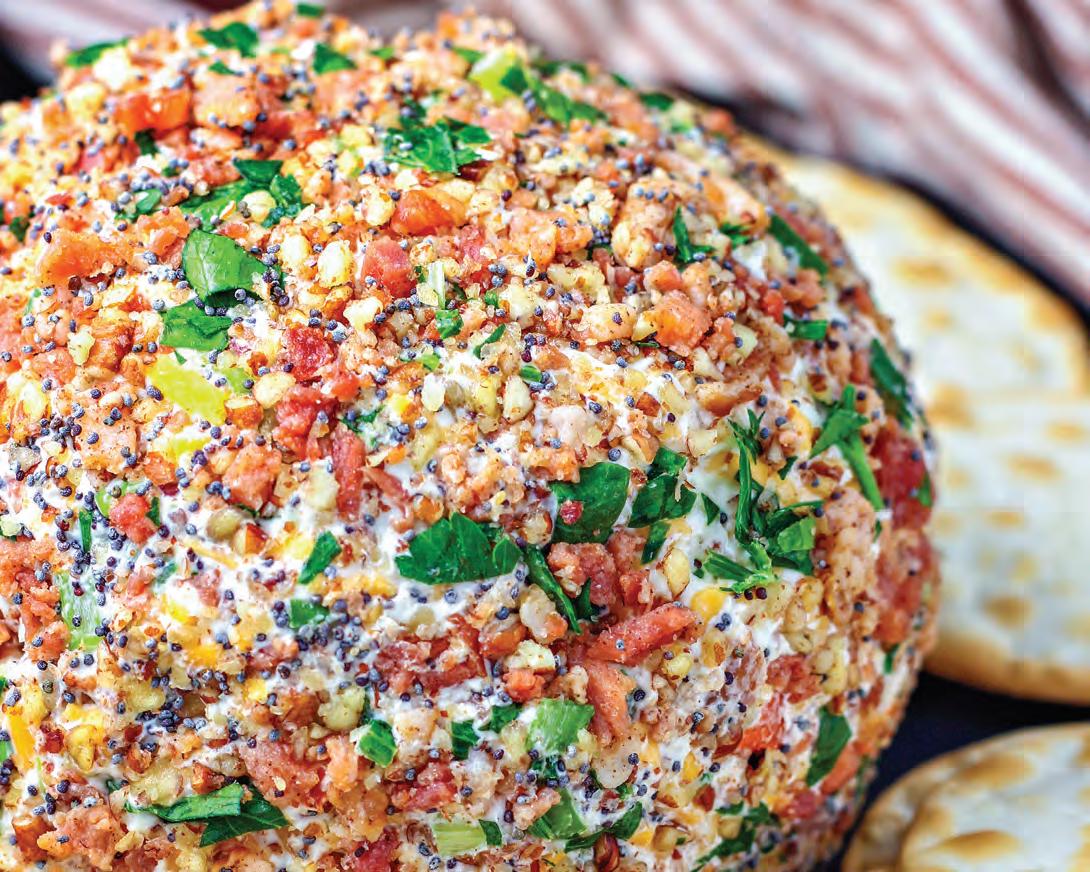

34 Kitchens

Go crazy for these cheese dishes to warm up your appetizers, dinner plates and afternoon munchies.

38 Poetry

Colorado poets reflect on life during the winter months as they drive through the mountains or settle in for a warm meal.

40

Lake City becomes a haven for ice enthusiasts as they climb 170-feet ice towers for the annual Ice Climbing Fest in February; Snow or shine, Steamboat Springs’ WinterWonderGrass is back for its 12th year of mountain festival bliss with local artists, craft breweries and local eateries.

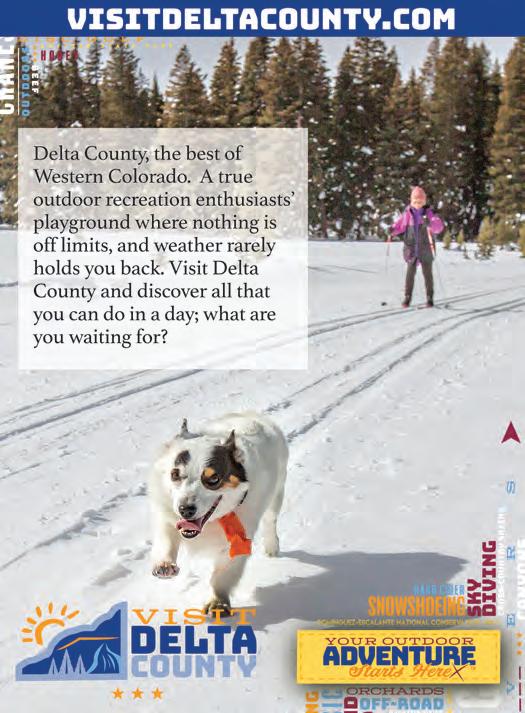

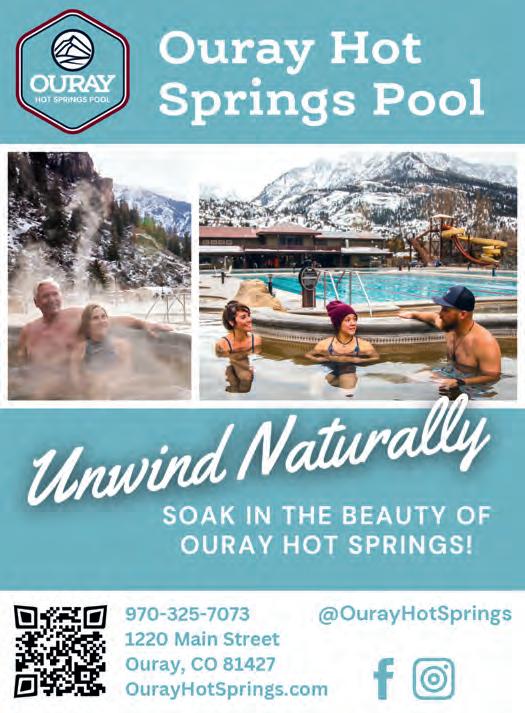

45 Hot Springs

Big or small, these hot springs offer a refreshing reprieve in the Colorado mountains, including the Hot Sulphur Springs Resort and Spa along the Colorado River.

54 Peak Pixels

Colorado’s landscapes are rich for raptor sightings, including a great horned owl perched atop a tree in a Loveland backyard.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

Volume 14, Number 1

Publisher & Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher Angela Amundson

Managing Editor

Lauren Warring

Assigning Editor

Victoria Finlayson

Design

Jennifer Stevens, Mark Del Rosario Lydia Paniccia, Tim Parks

Staff Writer Ariella Nardizzi

Photography Coordinator

Erik Maki

Advertising Sales

Sarah Smith

Subscriptions

Liesl Amundson, Janice Sudbeck Anne Canto, Julian Amundson

Colorado Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. PO Box 270130 Fort Collins, CO 80527 970-480-0148

ColoradoLifeMag.com

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $30 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit NebraskaLife.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and group subscription rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com or visiting ColoradoLifeMagazine.com/contribute.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2025 by Flagship Publishing, Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

A chorus of vows reverberate through Loveland Ski Area on Valentine’s Day. Atop Forest Meadow, towering evergreen groves and pillowy snow flank a pristine valley nestled at 11,215 feet. Nearly two hundred couples gather here in a sea of bright wedding attire to elope or renew their vows. Veils pinned to ski helmets flutter in the wind, and bulky ski boots peek out from underneath white gowns of brides-to-be.

Couples converge for the 34th annual Mountaintop Matrimony: Marry Me and Ski for Free, a beloved Loveland Ski Area tradition. The mass ceremony takes place every Feb. 14 at noon. The lift ferries participants and their loved ones up to the open glade between the Catwalk Trees and Chairlift Six, offering breathtaking views of the Continental Divide.

Each year, about a dozen lovebirds take the plunge to legally marry on the ski hill for the first time. One such couple was Loveland’s safety and risk manager, John DiSciullo, and his wife, Karen. The pair celebrate their 9th wedding anniversary on Feb. 14, commemorating the day they said “I do” as snow flurries fell around them.

DiSciullo participated in the Mountaintop Matrimony event in 2016, back when it still fit inside the Ptarmigan Roost cabin. He rented an oversized tuxedo to fit

Every February, dozens of couples say “I do” on the slopes of Loveland Ski Area. Following the ceremony, newlyweds shred, slalom and schuss down the snowy track. Brides and grooms from previous years join every anniversary to celebrate their mountaintop love.

over his many winter layers and sported a trapper hat with plaid ear flaps to keep out the snow. His wife rented a classy ’20s flapper dress with intricate lace detailing.

“Loveland is my church. It’s not that I’m a religious man – but it’s been my special place for a long, long time,” said DiSciullo, a Loveland pass holder for 30 years. He knows every stump, rock and bump on the mountain.

Couples return year after year to celebrate the milestone, renewing their vows while donning the same snow-white tuxedos, top hats and full-length dresses they wore in years past.

During the 30-minute ceremony, officiant Brett Butson shared his reflections on love. Then, each couple has a moment to share private vows with one another, surrounded by hundreds of other mountaintop couples.

This ceremony isn’t just sealed with a kiss. As a testament to their love for each other – and the mountain – newlyweds strap on their skis or boards and glide down the slopes together. Hundreds of brides and grooms shred, slalom and schuss to the resort’s base, kicking up fresh powder together.

For DiSciullo, skiing down as new-

lyweds was a memory for the ages. His friends and wife’s two children joined the pair for their snowy celebration. “We ripped up the steeps,” he said of the ski area’s notoriously challenging vertical bluffs. “I was still in my tux. My wife rode down in her flapper dress.”

At Loveland Basin, the afternoon culminates in a Honeymooner’s Après Party at 1:30 p.m., where celebrants toast to matrimony with cupcakes and glasses of sparkling apple cider.

Each couple also receives a customized goodie bag, including a collector’s edition can from Golden-based Coors Brewery. Loveland Ski Area partners with Coors to design new can wraps every year, which have become a sought-after keepsake for Valentine’s Day returners.

Kristine Kimbriel and Sage McCririck have organized the cherished event for the last decade. She enjoys reuniting with couples every February and witnessing the avalanche of colorful gowns, veils and attire cascading down the slopes.

“The people that come year after year have a place in their heart for Loveland Ski Area,” Kimbriel said. “They not only can come ski but also express their love –for each other and the mountain.”

by CORINNE J. BROWN

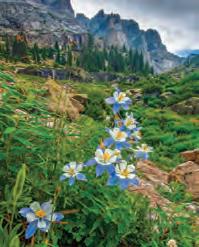

For centuries, Colorado’s sweeping vistas, vibrant wildlife and dynamic light have inspired artists to capture the state’s essence. Among today’s masters of this art is Bruce Gómez, a Colorado native who has spent decades perfecting his craft with pastels. Through his work, Gómez creates windows into the natural world, layering light and shadow to evoke the quiet majesty of the landscapes he loves.

Gómez’s pastel paintings bring to life the intricate beauty of Colorado. In one, a hummingbird appears suspended in time,

its delicate wings a blur against a luminous blue sky. In another, a bee nestles into the heart of a bright yellow flower, the textures so vivid you can almost hear the buzz. His scenes of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, with their striking interplay of sunlight and shadow, radiate a sense of place that resonates deeply with viewers.

Self-taught and intuitive, Gómez has honed his techniques over decades, layering color on specially processed watercolor paper to create radiant compositions. Each piece is the result of meticulous study. He revisits his subjects several times, observing how the light shifts throughout the

day, and adjusts his palette to capture the unique spirit of each location.

“I use my own photographs for reference and when I’m out in nature, I capture what moves me,” Gómez said. “I’m not looking for something specific but when it hits me, it hits hard. When I tackle the canvas, it’s all about emotion – mostly awe.”

Gómez’s connection to Colorado is deeply personal. His family’s roots run deep in the southern part of the state, and he’s spent over 20 years painting the Telluride area, his favorite subject. The jagged peaks and serene meadows of the San Juan Mountains have become a cornerstone of his portfolio, reflecting both the grandeur and intimacy of the Colorado wilderness.

Beyond Telluride, Gómez’s work has taken him across the state and country. Loyal collectors and gallery commissions have brought him to places like Breckenridge and Denver, where his art is displayed at the Shawn Horn Gallery and Abend Gallery, respectively. His ability to capture the soul of a place has made him a sought-after figure in the art world.

Gómez is also a dedicated teacher, sharing his expertise with students across the West. This past fall, he participated in three back-to-back plein-air exhibitions and workshops in Sedona, the Grand Canyon and Zion. Despite the grueling schedule, he returned to his Denver studio invigorated, ready to distill the inspiration of those travels into new works. His studio, bathed in natural light from a polycarbonate ceiling, provides the ideal setting for his creative process.

“Painting is all about light, no matter the time of day. When I sit down to study these photos, I can still feel the light, that moment,” Gómez said. “I paint to capture those rare moments. If one takes a minute or a day, they might catch the magic of beauty, however briefly, to put in their pocket forever.”

As he works, Gómez continues to build on his legacy as one of Colorado’s most gifted artists. His pastels remind us of the state’s breathtaking natural wonders, from the delicate shimmer of a canyon’s morning mist to the vibrant colors of an aspen-lined trail in autumn. Through his eyes – and his art – Colorado comes alive.

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

The number “303” is more than just digits to Denverites. Since 1947, the original 303 area code has symbolized everything from Boulder’s snow-capped peaks and Golden’s mining history to the vibrant River North Art District, Union Station and Capitol Hill neighborhoods.

Every March 3rd, Denverites honor their iconic Front Range code with 303 Day. The city bursts to life with music, food, drinks and hometown pride. While unofficial, this beloved tradition has been embraced by small business owners, local artists and musicians since 2009.

Boulder-born hip-hop duo 3OH!3 headlines the festivities every year. Known for their high-energy synth-pop

performances, Sean Foreman and Nathaniel Motte keep crowds dancing into the night. “The support for live music in Colorado is unparalleled. Every year feels like we’re rocking a house party with our closest friends,” Foreman and Motte shared.

This year, Denver radio station KTCL 93.3 is hosting two shows. 3OH!3 will kick things off early at Cervantes’ Masterpiece Ballroom in Five Points on Feb. 28, followed by their 303 Day debut at the Larimer Lounge in the RiNo Art District on March 3.

Indie 102.3 is also joining the fun, curating live performances by local talent. Listeners vote for their favorite “303” artists, who will perform at Number 38 from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. Past acts include Denver rock band The Trujillo and Colombian

artist Virgi Dart, whose music spans cumbia, ballads and pop.

303 Day also highlights Denver’s thriving local businesses. With no shortage of craft breweries, past years have seen spots like Rhein Haus and Wally’s Wisconsin Tavern offering beer specials. Golden-based brews like Coors Light, Miller Lite and Outlaw Lager have been featured for $3.03 a pint.

For a sweet twist, Flight Club Denver –a cocktail bar near Union Station – offers cotton candy for $3.03 alongside rounds of darts.

“303 Day is a terrific opportunity to celebrate all the amazing things our state has to offer – from incredible restaurants and outdoor recreation to our culture and communities,” said Gov. Jared Polis. “I hope everyone enjoys 303 Day and finds a fun way to celebrate this state we all love.”

While the full list of 2025 promotions is still under wraps, one thing is certain: on March 3rd, Denverites will unite to honor their city’s vibrant history, thriving businesses and creative spirit. 303 Day is a tribute to Denver’s past, present and future.

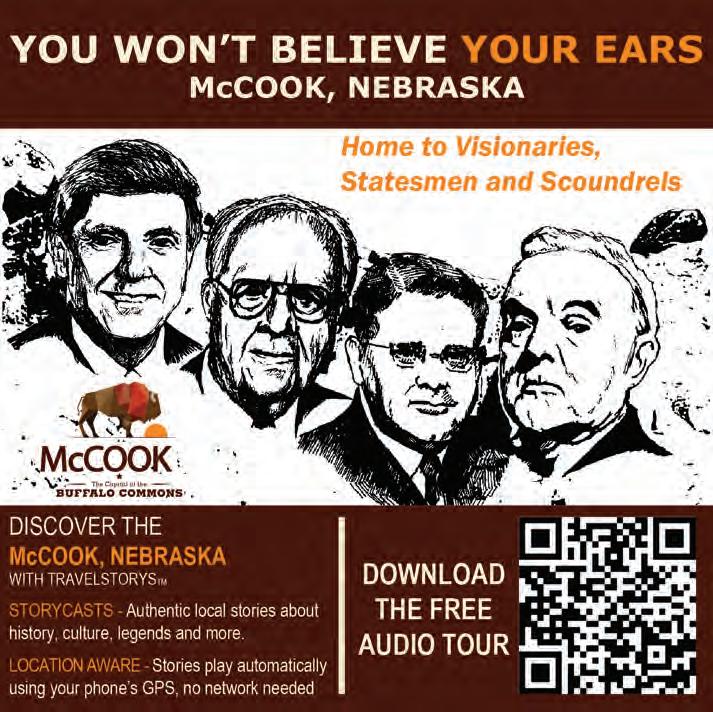

With election season over, we reflect on past politicians. by BEN KITCHEN

1 Colorado’s longest serving senator was Henry M. Teller, who held office from 1876 to 1882 and from 1885 to 1909. What cabinet-level position did he hold from 1882 to 1885, later held by fellow Coloradoans Ken Salazar and David Bernhardt?

2

What Republican is the mayor of Aurora? He served in the House of Representatives for 10 years before becoming mayor. In recent news, he has pushed back on President Trump’s comments about the prevalence of gang violence in Aurora.

3 In 1892, Lafe Pence and John Calhoun Bell were elected as Colorado’s only two representatives in the House. They represented the same political party as James Weaver, the third-party presidential candidate who won Colorado that year. To which party did they belong?

4

Two-term U.S. Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell is one of only five senators in U.S. history to represent what demographic? The only current senator with this distinction is Oklahoma’s Markwayne Mullin.

5 Almost certainly the most famous person to run for sheriff of Pitkin County is what author as a member of the Freak Power ticket? His platform included, among other things, renaming Aspen “Fat City.”

6

In the 2018 film The Front Runner, Hugh Jackman portrays former U.S. Sen. Gary Hart, whose 1988 presidential bid collapsed after the Miami Herald exposed his affair with Florida model, Donna Rice. A famous picture surfaced weeks later with Hart and Rice on what yacht?

a. Monkey Business

b. Off the Hook

c. Trouble Maker

7 In 2010, it was revealed that former Colorado Gov. John D. Vanderhoof had what valuable item now at the Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum in Golden?

a. A moon rock

b. A ruby weighing 50 carats

c. A faceted sample of painite

8

Gaining the title in 2024, what representative from Colorado is only the second person to ever hold the position of house assistant Democratic leader, after South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn?

a. Diana DeGette

b. Jason Crow

c. Joe Neguse

9 Which current Republican representative will have about a six-month tenure, entering office in July 2024 after Ken Buck resigned?

a. Doug Lamborn

b. Greg Lopez

c. Lauren Boebert

10 Rep. Pat Schroeder served 24 years in the House and was Colorado’s first female representative. She famously coined what presidential nickname as a comment on the man’s ability to avoid negative press?

a. “Tricky Dick,” Richard Nixon

b. “Teflon President,” Ronald Reagan

c. “Slick W illie,” Bill Clinton

11

Jared Polis was the first openly gay person elected governor of a U.S. state. The word “elected” is key, as former New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey came out during his resignation speech.

12

Former Gov. John Love resigned his position in 1973 for a very good reason: He was appointed by President Nixon to be the first Secretary of Energy, as the Department of Energy had just been founded.

13

Speaking of former Gov. John Love, he’s in a bit of a political family: his daughter, Rebecca Love Kourlis, served on the Colorado Supreme Court from 1995 to 2006.

14 Between March 16 and 17, 1905, Colorado had three governors in 24 hours: Alva Adams, James H. Peabody and Jesse F. McDonald. Both Adams and Peabody were involved in voter fraud, which led to McDonald taking office.

15

U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper holds the title of Colorado’s current “senior senator” because he is older than fellow U.S. Senator Michael Bennet.

Our ancestors brought horses to this continent, and they helped us build the nation. Now we return the favor.

by PETER MOORE

Once an integral part of our country’s development, wild horses now find freedom in Northwest Colorado.

HORSES AND PEOPLE go way back.

The large herd that’s living happily near Maybell, for instance, may have descended from horses brought to this continent on Columbus’ second voyage in 1493. He arrived with 17 ships loaded with 1,200 colonizers and their favorite mode of transport: on the hoof. Hernán Cortés and others soon followed, also bringing horses. The landscape was altered forever.

I met their equine descendants on a glorious morning last summer, soon after my wife Claire and I pulled into the dirt parking lot of the Wild Horse Refuge, west of Craig in Moffat County. In the northwest part of our state, the land stretches endlessly, wave after wave of low hills extending off to the horizon – not a stoplight in sight.

After Cindy Wright, founder of the Wild Horse Warriors of Sand Wash Basin, emerged from her office at the refuge and fired up her pickup, we set off onto the high plains. It was as much a chiropractic treatment as transportation, as we bounced across open prairie on rutted dirt roads.

“Now where are the horses today?” Wright wondered aloud, with good reason.

There are about 170 wild horses scattered around the 23,000 acres of the refuge, and they can travel seven miles or more a day, according to Wright. Horses really get around when it comes to reproduction, as well. But we’ll get into that a little bit later.

“Horses are part of our heritage,” Wright said, scanning the chaparral. “Our relationship with them goes deeper than words. They are part of what America is –part of our beginnings here.”

By “here,” Wright means North America. Horses helped explore and settle this land. But neither Columbus and his fellow Homo sapiens, nor the domesticated Equus caballus they carried with them, were the first of either species on this continent. Indigenous people had beaten the Spaniards to North America by 16,000 years.

Those early humans arrived long after the first horses who had been evolving here for 10 to 20 million years. The orig-

inal North American horses – some the size of small dogs or towering 7 1/2 feet at the shoulder – went extinct around 12,000 years ago, about the same time humans arrived to hunt them.

It may not be a coincidence.

I learned all about it from Sarah King, Ph.D., a research scientist in the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. She is British by birth and took riding lessons every weekend as a child. It led to a fasci-

nation with horses, so when she entered university, she studied Przewalski’s horses in Mongolia. They are among the last truly wild horses in the world.

So, what about the 80,000 mavericks currently grazing the American West? Aren’t they wild?

“The differences between a wolf and dog are equivalent to the differences between Przewalski horses and our domesticated horses,” King said. “You can tame a feral dog, and it will live in your house.

Formerly known as the Ri Ro Mo Ranch, Wild Horse Refuge west of Craig provides 23,000 acres for captured and relocated wild horses to roam freely. The non-profit’s mission is to give these wild horses untamed freedom to live as closely to how they would in the wild.

You could try that with a wolf pup, but it would never behave like a dog.”

Our so-called “wild horses” have more in common with that friendly dog on your hearth than they do with Canis lupus. King pointed out that, for at least 5,000 years, human beings have been selectively breeding horses to optimize their body shape for riders, their musculoskeletal systems to haul loads, their personalities for training and companionability and their breeding cycles for maximum foal production.

And it worked.

In an op-ed for the Journal of Wildlife Management, King and her co-authors put it this way: “Horse domestication is an important component of human history and significant in humans’ emotional attachment to horses. Horses enabled cultures to disperse and advance agriculture, transportation, industry, commerce and warfare.”

Given those historical bonds between horses and humans, it’s no wonder that Cindy Wright – the wild horse warrior in

chief – and others have been working so hard to save the not-so-wild horses that populate our not-so-wild West.

That’s where the breeding habits of our formerly domesticated animals come in. “A two- or three-year old mare can produce a foal every year into her 20s,” King said. “They do that very successfully out on the range.”

And that’s the problem with our “wild” horses: Their ancestors had been bred to make lots more horses.

PROLIFIC BREEDING worked well when horses were our primary means of transportation and hauling. But during the Industrial Revolution, other means of transport came online, and horses became an expensive hobby for people who could afford to stable, feed and train them. Soon the rest of us were driving our Mavericks, Colts, Mustangs and Broncos off to the mall, instead of saddling them up and riding toward a limitless horizon.

Countless thousands of horses were released by their owners, or escaped their pens, which led to a population explosion on rangelands in the 11 states that comprise the Great Basin. Colorado is the bullseye in that target. Even if the utility of horses as working animals and

companions has passed by, their legend sticks with us. What’s a horse lover to do now, with tens of thousands of animals scouring western land and crowding out native species?

The Wild Horse Refuge is trying to provide an answer. Even though its carrying capacity is only about 300 horses – a mere 1% of America’s wild population – they are at least trying to provide what Wright calls “the ultimate retiremeƒnt home” for the rescue horses that live there.

The refuge has been in operation since January 2023, when the Wild Animal Sanctuary in Keenesburg purchased the former Ri Ro Mo Ranch. They began adopting horses captured in a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) roundup, and then moved

them onto land adjacent to the Sand Wash Basin, already home to herds of wild horses.

Wright was present when the horses moved into their new home. “It’s no different from when horses come together at a water source,” she said. “They posture, they sniff and make acquaintances. It’s the same thing in a crowd of people who have never met each other. Horses react more strongly, but the principle is the same.”

It sounds kind of like a fraternity mixer, albeit one where all the partygoers are orphans and have either been gelded or shot up with contraceptives, through the efforts of the Bureau of Land Management. The message: We don’t need any extra wild horses, thank you. But we’ll take care of these lucky animals for the rest of their lives.

PAT CRAIG IS the Daddy Warbucks of animal rescue in Colorado. Big cats, camels, grizzly bears, wolves or ostriches – he welcomes them all at the Wild Animal Sanctuary in Keenesburg. He has rescued Asiatic bears in Korea, emptied an abandoned zoo in Puerto Rico and removed lions from a facility in a Ukrainian war zone, just to name a few.

Craig first began welcoming threatened creatures to his family farm in Boulder in 1980, then moved to a larger facility in Keenesburg in 1994. As word spread, he gained lots of supporters and volunteers, along with endorsements from Jessica Biel, Edie Falco and other famous animal lovers. All of that reached a new level in 2020, when he worked with the Depart-

ment of Justice to close the roadside zoo run by “Tiger King” Joe Exotic, of Netflix infamy. Craig now operates four rescue facilities in Colorado and one in Texas.

There’s at least one way the Daddy Warbucks comparison is off, however: Craig was never rich. He held down two jobs just to be able to return home and work through the night to care for his rescue animals. His “staff” was his wife and two kids. He started a newsletter and slowly built a donor base that has paid for the wide-ranging rescue efforts in Colorado and beyond.

Though he’s now known for international animal rescues, Craig was first and foremost a horseman. “I grew up on a farm with horses, cows and chickens,” he said.

His lifelong experience with animals eventually led him to focus on rescuing horses.

“We found 10,000 acres in southeast Colorado,” Craig said. “It was remote, and awesome for the animals. We built barns and corrals in Keenesburg and held very successful adoption events.”

But there were always more wild horses to house, so Craig was soon driving along backroads, looking for just the right property to host more rescued horses. Fate intervened when the BLM announced that they were going to begin helicopter roundups of horses in the Sand Wash Basin in Moffat County. The Ri Ro Mo Ranch was just 25 miles east of there, with a similar habitat. It would be a perfect location – “untouched since the beginning

of time,” Craig said – to host new bands of horses. With the help of donors, he bought it.

Craig readily acknowledges that the Wild Horse Refuge is not the final answer to the problem, but it is the best he can do now. “I turn down 50% of the rescues I’m asked to make,” he said. “I have to say no, and the animal will be dead. I’ve had to live with that for 40 years.”

But he hopes that others will follow his model, and that together a new generation of rescuers can make a difference – both by sheltering vulnerable animals and urging legislation against over-breeding and wild-pet nurseries.

“Saving one tiger, one horse, is better than saving none,” Craig said. “It may not change the world, but for that one animal it changes everything.”

OUR PICKUP TRUCK rolls over a rise in the prairie, and there they are: The wild horses we’ve come to the refuge to see. A dozen beautiful animals are clustered around a water hole maintained by the WHR staff. The horses raise their noble

heads to scope us out. Wright greets them like old friends, calling their names with affection: Vega, Michelangelo, Kahlua. Wright says horses at the refuge score an eight or better on a health scale of 1-10. Nearby horses on BLM land are closer to 4 or 5.

These horses, whether thriving or just surviving, owe their existence to human hands. Brought to this continent 500 years ago, they helped build this nation – and now we must help care for them.

For $777 (“lucky sevens,” Craig said) you can “adopt” an acre at the refuge and visit the horses whenever Wright has an opening in her schedule. Every September, Craig welcomes landholders to the refuge for Founder’s Day.

Meanwhile, King, the research scientist, took a more personal approach. Two years ago, she adopted a mustang from a herd management gather in western Utah. “When the horses were put up for adoption, I put up my hand when they offered my horse, and I got him for $275,” she said. King, also a dog and horse trainer, has been working with her horse, Cowboy, using positive reinforcement training. “It

means I have a good relationship with him,” she said. “We’re training at his speed. I’m not riding him yet. That will take as long as it takes. I’m alright with that.”

AFTER OUR MORNING at the Wild Horse Refuge, Claire and I said goodbye to Cindy Wright, and followed her directions down highway 318, over to the Sand Wash Basin. We drove a dirt road onto the Seven Mile Ridge and stopped the car.

We were surrounded by wild horses. It was a peaceful scene, until two stallions decided it wouldn’t be. We were now outside of the preserve, so the nearby mares were probably in heat. The stallions nickered and jostled one another, then rose up with hooves lashing. But the fight ended quickly – plenty of mares to go around.

This is the problem, of course. We human beings brought the horses to this continent and genetically modified them toward abundance. It worked too well. Now, it’s up to us to help them coexist here.

“Horses changed the world,” Wright said. “They’ve given so much. They deserve a chance to stay wild.”

Sled dogs yelp for joy, pulling their humans through the pristine snow of the Grand Mesa.

STORY BY HEIDI POOL AND TOM HESS PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEELA McCLENEGHAN

OON A SUBZERO WINTER MORNING, snow muffles all sound on the Grand Mesa until the sparkling flat-top mountain comes alive with the sharp yips and howls of eager sled dogs.

Those joyful sounds bring tears to the eyes of Shannon Greene, a U.S. Marine Corps wartime veteran. She knows her Siberian Huskies will follow her commands – Gee! (turn right), Haw! (turn left), Hup Hup Hup! (a motivational chant) – even into the teeth of blinding snowstorms. Some days, those storms turn a six-mile sled dog race into a grueling trek that feels like 60 or even 600 miles. Though Shannon might lose sight of what’s directly ahead, her dogs always know the way.

Grand Mesa, located on Colorado’s Western Slope, receives an impressive 300 to 420 inches of snow annually, on par with Wolf Creek Pass. It’s atop this snow-covered mesa that Shannon, who served 23 years in the Marines, brings the Siberian Huskies she’s bred, raised, and trained to compete in the annual Grand Mesa Summit Challenge.

Shannon and her husband, fellow Marine veteran Brian Cockriel, were married in 2014 in Kandahar, Afghanistan. The couple now lives on a few acres north of Elizabeth, Colorado, where United States

and Marine Corps flags fly proudly from their home. The property is spacious enough for their 13 dogs, who trample the backyard, wear down the wooden stairs, and bark insistently when a low-pressure front signals incoming snow.

Brian is Shannon’s handler on the Colorado sled-dog circuit, which includes races from Walden to Silverton. Their daughter, Raicheal Greene-Cockriel, joined the family’s passion as a junior-class sled-dog musher, competing in her first race in early 2024.

The family draws inspiration from the legendary Siberian Husky, Togo, who helped deliver life-saving serum during the 1925 diphtheria outbreak in Nome, Alaska. The Disney movie Togo has become a family favorite. Shannon estimates

she’s watched it a “million” times, crying at each viewing. She even recites lines from the film. Her own lead Husky, Nanook, is her personal Togo, helping her earn the title of Colorado State Rookie Musher of the Year for the 2023-24 season.

Mushers and their dogs come every year to the Grand Mesa to compete in in the Grand Mesa Summit Challenge. Racers with their team of two to 16 dogs prepare for up to 8-mile races across the flattop mountain.

ON RACE DAY, THE EXCITEMENT is palpable. Teams like Montrose musher Jesse Miltier’s eight-dog pack sense the anticipation, jumping and straining at their harnesses as the countdown begins. With each passing second, their barking grows louder until, at the command “Go!”, they leap forward, propelling Miltier’s sled across the snow. Spectators cheer enthusiastically, chanting “Hike, hike, hike!” as the team vanishes into the wilderness, 32 furiously galloping legs kicking up a flurry of snow.

Two additional teams, spaced a minute apart, follow Miltier onto the course. The race’s 6- or 8-mile track winds across Grand Mesa’s rolling terrain, where the wind-rippled snow and breathtaking scenery create a challenging but stunning backdrop.

The Grand Mesa, the world’s largest flat-top mesa, dominates the eastern edge of Grand Valley. At 10,500 feet above sea level, the Summit Challenge holds the distinction of being the highest-elevation sled-dog race in North America. By comparison, Alaska’s nearly 1,000-mile Iditarod peaks at just 3,771 feet.

Preparations for the January event begin a week in advance. Members of the

Rocky Mountain Dog Sled Club, along with U.S. Forest Service Snow Rangers, use snowmobiles to pack the trail. “You need to set a firm base so the dogs won’t sink to the bottom,” says Lynn Whipple, president of the Rocky Mountain Sled Dog Club, a co-sponsor of the race. After three days of packing, volunteers from the Delta SnoKrusers Snowmobile Club use their snowcat groomer to finish the course.

Participants compete in two categories: pro (seasoned mushers) and recreational (newer mushers), and in two disciplines: sled-dog racing and skijoring – a thrilling blend of cross-country skiing and dog power. Sled teams range from two to 16 dogs, with the race length matching the team size (the eight-dog course is 8 miles long).

Before the race, spectators and mushers gather for a course briefing. Popular Grand Junction radio personality MacKenzie Dodge provides live commentary from her repurposed yellow school bus. With her gravelly voice and infectious enthusiasm, Dodge encourages spectators to act as unofficial “handlers,” assisting mushers with unloading and guiding dogs from the parking lot to the starting gate.

A special bond is formed between racer and pup as mushers train throughout the year with their four-legged team. On race day, dogs like Roxie fly out the gate pulling skijorer Gregg Dubit down the track.

EXCITEMENT ON THE TRACK occasionally leads to chaos. Miltier’s team crosses the finish line without him, leaving officials scrambling to locate the missing musher. Volunteers quickly identify his dogs and contain them as Miltier, uninjured, recounts the mishap: “I was past the 8-mile turnaround when I went down into a dip. When I tried to straighten it out, my dogs flipped me.” Despite the setback, Miltier’s team finishes strong on day two, earning second place overall.

Whipple also encounters challenges. Her six-dog sled team, led by Apollo and Odie, becomes tangled at the start of her first race when a spectator lying on the course disrupts their momentum. “Apollo is the brains of the operation, and Odie has the

speed,” she explains. “They’re a bit competitive, but they work well together.” The team recovers and clinches first place in their category with a total time of 49:33 minutes.

Durango Dog Ranch’s Roxie, a tireless competitor, dazzles in both the eight-dog sled race and one-dog skijor. After just an hour of rest, she’s back on the track, eager to pull musher Gregg Dubit across the snow. “She’s unstoppable,” says Dubit, as it takes three people to hold Roxie back before the skijor begins.

While Arctic breeds like Huskies and Malamutes dominate the sport, other breeds also shine. Laurie Brandt of Montrose races Eurohounds – a mix of German Shorthaired Pointer and Alaskan Husky – and compares skijoring to mountain biking. “You’re going up to 25 miles per hour downhill. On the uphill, I really push, like I’m the ‘third dog,’ ” she says.

With the power of eight or more dogs, teams can reach up to 25 miles an hour downhill. To the right, a team of Alaskan huskies charge down the trail, excited to pick up speed for the final stretch.

With two solid runs and no spills, Brandt takes third place in her race.

For many, the Summit Challenge is less about the competition and more about the bond between human and canine. “Dogs have a living-in-the-moment enthusiasm that’s contagious,” says Brandt. “When you’re out there racing with them, the pressures of life and work fall away.”

On the Grand Mesa, it’s always a race of grit, grace and the unbreakable bond between musher and hound.

Want to experience the thrill of the sled dog races for yourself?

Mark your calendar for the 2025 Grand Mesa Summit Challenge, happening Jan. 25-26, 2025 on the breathtaking Grand Mesa. Join us to cheer on mushers and their amazing canine teams, explore the winter wonderland and be part of this unforgettable Colorado tradition. For event details, directions and tips for spectators, visit the Rocky Mountain Dog Sled Club website at rmsdc.org or follow them on social media for updates. We’ll see you on the snow!

Nicole and Harry Hansen craft handforged housewares and jewelry in Salida, teaching others to create their own jewelry at Riveting Experience on F Street.

story by MARJORIE ACKERMANN

photographs by H. MARK WEIDMAN

ONA SWELTERING July day in 2012, Harry Hansen crouched behind a young horse, trimming its hind hoof in his lap. A seasoned Chaffee County farrier, he felt the gelding tug once, then again, and waited for it to relax. Suddenly, the horse yanked its foot free, striking Harry in the back before delivering a sharp kick to his jaw. The blow left him with a gashed chin, three missing teeth and a traumatic brain injury.

At 39, Harry realized his days of shoeing horses were numbered. Plagued by migraines and brain fog, he was unable to work for months. In true small-town fashion, his hometown of Salida rallied around him, helping with groceries and mortgage payments. Six months into Harry’s recovery, he and his wife, Nicole, began imagining a new future. Combining his blacksmithing skills with her expertise as a jeweler, they launched Sterling & Steel.

Neighbors rented them a garage, where they set up a forge and grinder. Soon, they were crafting custom jewelry and housewares that blended stainless steel and sterling silver. Their designs paired rustic elements with refined finishes – like a stainless-steel cuff inlaid with gold or a hand-hammered fork handle crowned by polished silver tines.

Nicole, a fourth-generation Coloradan, had honed her craft in her family’s Boulder jewelry shop, Master Goldsmiths. Harry, meanwhile, grew up off-grid in Arizona, learning to weld and shape iron from his father. The two met in 1991 in Sedona, where Harry lived with his parents and five siblings on a sprawling 177acre tree farm. A shared love of horses and metalsmithing sparked their bond.

By 1997, the couple had relocated to Salida, drawn by Nicole’s longing for Colorado’s change of seasons and the warmth of a welcoming community.

In 2013, they took Sterling & Steel on the road, traveling to arts festivals and juried craft shows nationwide. At home, they hosted workshops for couples designing their own wedding rings.

“The marriage of sterling and steel is a metaphor for our life together,” Harry explained. “Nicole works in precious metals; I work in steel. She works it cold; I work it hot. We don’t compete – we complement each other.”

By 2019, the couple had grown tired of constant travel. Missing their two teenage children and their Salida roots, they pivoted again, opening Riveting Experience on historic F Street. Part jewelry store, part workshop, the space hums with creativity, its brightly lit interior beckoning locals and tourists alike. Copper cuffs, turquoise necklaces and hoop earrings share space on an inspiration wall with belt buckles and embossed metal plates on caps.

On a recent Saturday, the shop buzzes with activity. Denverite Jessica Feiler, wearing a “Bride-to-Be” sash, hunches over an oak laminate workbench with her seven bridesmaids, crafting bracelets and necklaces from copper, leather and silver. Jessica stamps an owl design onto a silver pendant, while her sister runs a copper disc through a rolling mill, embossing it with a laser-cut pattern. Another bridesmaid hammers a dimpled texture into a copper band as oth-

The Hansens’ hand-forged housewares and wedding ring appointments are available at sterlingandsteel.com

To schedule a DIY jewelry workshop, visit rivetingexperiencejewelry.com

ers sift through trays of bangles, beads and gems for their projects.

Guided by Harry and his two assistants, each participant learns to select materials and fabricate their pieces step-by-step.

“Riveting Experience is a chance to share our love of metalsmithing with a much broader audience,” Nicole said. “We saw the pleasure and sense of accomplishment people felt in our wedding ring workshops and wanted to build on that.”

Travelers are known to plan their trips around a stop in Salida to make jewelry with the Hansen team, Harry added. “For us, it’s a pretty special thing to share that creative journey with those who otherwise might not have the time, space or means to make jewelry on their own.”

The Hansens provide the necessary tools and materials for guests to craft their own personal jewelry: rings, bracelets, pendants, earrings, necklaces and hats.

Dishes that pack a punch with bold, crave-worthy flavors

recipes and photographs by DANELLE

McCOLLUM

WARM, BRAIDED JALAPEÑO cheese bread, creamy bacon-pecan cheeseballs and crunchy, tangy corn salad come together for a rich, cheesy appetizer spread. They’re a must-have for any game day, dinner party or family gathering and pair perfectly with barbecue, grilled meats and charcuterie boards.

Cheesy, zesty and braided – this jalapeño bread is the life of the party. Slather it in butter straight from the oven for an irresistible bite. Serve alongside smoky grilled meats or a hearty stew.

Add water, milk and butter to a saucepan over medium heat until butter is melted. Temperature should be 110-115°. Let cool if too warm. Then, stir in sugar and yeast. Let stand for 10 minutes or until yeast is frothy.

Add salt, 2 cups of flour and yeast mixture to a stand mixer bowl. Stir in egg. Mix with dough hook until well combined. Slowly add remaining flour until dough is soft and gathers at the bowl’s center.

Knead dough on a lightly floured surface for a few minutes. Let dough rest for 5-10 minutes, then roll into a 10x14-inch rectangle.

Sprinkle garlic salt, jalapeño and cheeses onto dough. Starting with the long end, roll dough into a tight log. Slice log vertically in half, keeping a few inches connected at the top. You should have two ropes of dough.

On both ropes, rotate the cut side upwards to expose the filling. Then, braid one rope over the other until you reach the end.

Place loaf in a greased, 9x5-inch pan and cover. Let rise in a warm place for 1 hour, or until dough doubles in size. Bake loaf at 350° for 40-50 minutes or until golden brown. Cover with foil for the last 20 minutes to prevent over-browning.

For the bread

1/2 cup water

1/4 cup milk

3 Tbsp butter

3 Tbsp sugar

2 ¼ tsp active dr y yeast (1 packet)

1 tsp salt

2 ½ cups flour

1 egg

For the filling

1 tsp garlic salt

1 jalapeño, minced

2 cups shredded cheddar cheese

1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese

Makes 1 loaf

Bring this cheese ball as your plus one to any dinner party. It’s packed with creamy cheese, smoky bacon and a crunchy pecan coating. Pair with a charcuterie board filled with salty prosciutto, crackers and fig.

Mix cream cheese, milk, cheddar, blue cheese, garlic powder, pepper and salt with electric mixer in a large bowl until well combined. Add green onions, pimento, half of pecans and half of bacon. Mix well.

On a large piece of plastic wrap, form mixture into balls and wrap tightly. Refrigerate for one hour or until mixture is firm.

Combine parsley, poppy seeds, remaining bacon and pecans in a shallow dish. Roll cheeseballs in mixture until evenly coated. Cover and refrigerate. Serve cold with crackers.

1 18 oz package cream cheese, softened

2 Tbsp milk

2 cups shredded sharp cheddar cheese

1/4 cup crumbled blue cheese

1/2 tsp garlic powder

1/4 tsp pepper

1/4 cup minced green onions

1 14 oz jar diced pimento, drained

1/2 cup pecans, finely chopped, divided

10 slices bacon, cooked, crumbled and divided

3 Tbsp fresh minced parsley

1 Tbsp poppy seeds

Pinch of salt

Crackers, for serving

Ser ves 12

The ultimate game day appetizer, this savory salad will be gone before the final whistle. A pop of bold flavor complements rich cheese and crunchy Fritos. Pair with grilled burgers or barbecue chicken for a winning combo.

Toss corn, cheese, bell pepper and green onion in a large bowl. Stir in mayonnaise and sour cream. Just before serving, stir in Fritos. Season with salt and pepper and enjoy.

2 15 oz cans whole kernel corn, drained

1 ½ cups grated cheddar cheese

1 cup chopped red bell pepper

1/4 cup chopped green onion

1/2 cup mayonnaise

1/2 cup sour cream

1 10.5 oz bag coarsely crushed Chili Cheese Fritos

Salt and pepper, to taste

Ser ves 8

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag. com or mail to Colorado Life, PO Box 270130, Fort Collins, CO 80525.

Colorado’s winters hold special memories for our poets. It’s the time of year to both tuck in with some hot cocoa as the snow falls and rise early to race down the slopes at sunrise. These moments of quiet and adventure inspire reflections as vivid as the season itself.

Vaughn Neeld, Cañon City

I cherish short winter days when the sun sends long golden rays across the forest-green carpet as light leaks from snow-chilled windows to pool upon the scarlet blanket that cuddles my knees, my feet, as I drowse within the comfort of warm sunshine and kitten-soft fleece.

Jody Davis, Colorado Springs

Lingering is the light That turns to winter’s blight

Trees in peaceful slumber Frozen grounds encumber The spring thaw.

Shirley Kobar, Loveland

are worth savoring like words of power and resonance. On those days I would stay the sun before it sets, slow time as it passes, taste each flake as it falls, hear snow as it touches my coat; breathing beauty and harmony thought bellows in the silence. Each moment nirvana captured in memory like snow in a water globe.

Sandy Morgan, Colorado Springs

My daughter comes bearing tulips yellow as day-old chicks; a gift that startles the old hen of night whose dark breast settles down on us a minute later each day.

I conjure candlelight and pot pie. We tuck in, hashing over the week, reminiscing, doing what daughters and mothers do when all is well as January turns its face to February.

J. Craig Hill, Grand Junction

Truck-thrown mud-brown slush

Makes windshield wipers worthless

Snow day on Vail pass

Snowflakes on my face

While I soak in the hot springs

Snow day in Ouray

Robert Basinger, Rifle

It was a day of clouds and elevation gain

With snow in the mountains, in the valley rain

I was chasing the horizon in the fading twilight

The sky pink and blue, a child’s delight.

At 20 degrees it was frozen fingers

No time to waste, light doesn’t linger

Out comes the camera, notebook and pen

I will never forget, just where I’ve been.

Cross-country boots and wooden skis

Those deep, dark woods call out to me

One more turn will set me free

So many things I have to see.

Ben Humphrey, Boulder

On cold overcast winter days, it’s a cup of hot soup for lunch a chance for the magic of falling flakes.

Clear weather with snow on the ground, sunshine is reflected, heaven’s dark blue, not hazy ’n hot, as in a daily summer report.

Shorter light, and longer darkness, means more time to see an occasional comet, ample hours to enjoy a bright starry night.

Layers upon layers, you stay warm, prevent freezing. Even naked in June, July, and August, it’s too damn hot. Give me winter, snow, fridge temperatures any old day.

Send Your Poems on the theme “Ascend” for the May/ June 2025 issue, deadline Feb. 1, and “On the Trail” for the July/August 2025 issue, deadline April 1. Email your poems to poetry@coloradolifemag.com or mail to the address at the front of this magazine

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

FEB. 1 • LAKE CITY

Sparkling blue frozen water clings to the cliffs above Henson Creek at the southern edge of historic downtown Lake City. As temperatures plunge, dripping water forms towering ice pillars reaching heights of 170 feet.

Dozens of ice climbers scale these massive ice formations for the Ice Climbing Fest each February. Climbers wedge the toe of their spiky footwear, called crampons, into the wall. With a sharp ice tool – like a pickaxe – in each hand, the climber swings the axes delicately into pockets of ice as they ascend the frozen tower.

Should a climber fall, a climbing rope attached to screws buried in the ice would catch them.

Skilled climbers flock to the ice flows every year to compete in the town’s thrilling ice festival. The competitions showcase each

Dozens of

climber’s speed, the winner being the quickest to ascend one of the area’s 100 routes.

The event includes mens and womens competition categories. The festival raises money to preserve the ice park, thoughtfully maintained by the town each winter to ensure climbers have free access to the ice.

The park also boasts four unique areas ranging in difficulty: the original Pumphouse Park, Beer Garden, Dynamite Shack and the newest Devil’s Kitchen which adds 500 feet of terrain and more than 30 new routes.

Whether pumping out on a challenging route or watching from the heat of a nearby warming hut, the Lake City Ice Festival is a thrilling way to embrace Hinsdale County’s chilling winters. lakecityice.com. (970) 944-2333.

Warm up with a piping cup of chai or a foamy cappuccino before a day on the ice. The boutique doubles as a cafe and boasts delicious breakfast burritos with green chile, biscuit sandwiches, pastries and cookies. 131 N. Gunnison Ave.

Each room in this cozy mountain lodge represents the beautiful environment and community that make up Lake City. Align your passions with a stay in the Fourteeners or Anglers adventure rooms, Antler or Black Bear wildlife rooms or historical Columbine room. 1223 N. Hwy. 149. (970) 944-5200.

ice climbers travel to Lake City to scale 170-feet ice towers for the annual Ice Climbing Fest every February.

FEB. 28-MARCH 2 • STEAMBOAT SPRINGS

The heavens dump thick, fat snowflakes on Steamboat Resort while crisp mountain air carries the sweet, earthy hum of a plucking banjo. Every winter, Steamboat Springs transforms into a snow-dusted wonderland, where cowboy hats and bolo ties bounce in time to flannel-clad locals stomping, hollering and twirling at the annual WinterWonderGrass festival.

The heavy snowstorm doesn’t dampen spirits – it fuels them here in Ski Town U.S.A. The locals only bundle up and sing louder. Their melodious voices accompany the chorus of bluegrass, jamgrass, Americana and roots bands.

The three-day festival enters its 12th year in Steamboat, each iteration only strengthening the city’s close-knit community. The main stage buzzes with anticipation as revelers sip hot whiskey

cider and craft beer from Tincup Whiskey and Montucky Cold Snacks. Some tuck close to firepits, indulging in food truck fare. Others sway with the crowd and sing their hearts out.

The eclectic 2025 lineup will once again feature fiddles, twangy guitars and soulful harmonies. Six-piece band Trampled by Turtles gathers a crowd of bluegrass fanatics, while The California Honeydrops performs blues and R&B for a fervent audience. Jam bands Leftover Salmon and Yonder Mountain String Band represent their local Colorado roots.

A portion of ticket sales will be donated to support hurricane relief in North Carolina. WinterWonderGrass is a community affair beloved by the Steamboat community that shows up year after year, snow, rain or shine. winterwondergrass.com.

Mouthwatering Texas-style barbecue and draft beers flow like the Yampa River at this Steamboat staple. All drinks are served ice-cold from a slurry of rock salt water and ice at 28 degrees. 751 Yampa St. (970) 875-3894.

This ski in, ski out boutique hotel nestles at the bottom of the Steamboat Ski Resort Gondola so that you can catch both first and last chair. Rooms boast an elevated, modern style, and hot tubs and saunas await after a day on the slopes. 2304 Apres Ski Way. (970) 879-1730.

TREAD OF PIONEERS MUSEUM

Revel in Steamboat’s rich heritage and culture. Current exhibits include the history of winter sports in Ski Town U.S.A. and a look into the Ute Indians knowledge of science, technology, engineering and math. 800 Oak St. (970) 879-2214.

High Plains Snow Goose Festival

Feb. 4-6 • Lamar

A white wave of tens of thousands of snow geese roost in southeastern Colorado during their annual migration. Lamar celebrates the magnificent spectacle with one of the state’s largest birding festivals, including sunrise tours and engaging educational seminars. 1900 S. 11th St. (719) 688-9582.

Taste of Chocolate

Feb. 8 • Craig

Delight your taste buds with bitter dark chocolate bars, creamy milk chocolate truffles and other confections throughout downtown Craig. Local chocolatiers display their baked goodness with chocolate tastings and community voting from 4 to 8 p.m. Historic Downtown Craig. (970) 824-2151.

Banff Mountain Film Festival

Feb. 13-14 • Grand Junction

Sweeping mountain vistas and epic adventure sports take over the big screen in Grand Junction. Filmmakers capture climbing, skiing, biking and kayaking athletes, mountain culture and environmental efforts in a cinematic display. Films start at 7 p.m. each night. Avalon Theatre, 645 Main St. (970) 261-1052.

Murder Mystery Dinner

Feb. 15 • Creede

Dinner is served with a side of mystery in Creede. Guests must don their detective coats and solve clues to catch the suspect before dessert. Event begins at 6 p.m. Community Center, 9 USFS Road #503. (719) 658-0811.

Fat Tuesday Festa

Feb. 15-16 • Denver

Party like it’s Mardi Gras with Denver Brass and Festa Bateria. Their toe-tapping horns and brassy trumpet harmonies transport the audience straight from the Newman Center to New Orleans and Brazil’s vivacious celebrations. Shows start at 2:30 p.m. 2344 E. Iliff Ave. (303) 871-7720.

Cripple Creek Ice Festival

Feb. 15-23 • Cripple Creek

International artists handcraft striking ice sculptures of steamer trains, ore diggers, castles and more with nothing but a chainsaw, ice tools and 160-pound blocks. The live, head-to-head competition and open-air galleries are open to the public. Bennett Ave. (719) 689-3461.

Mumbo Jumbo Gumbo Cookoff

March 1 • Manitou Springs

Twenty chefs craft five gallons of spicy Cajun gumbo with dark roux and sausage, okra and shrimp stew, bold New Orleans creole gumbo with crabmeat and bell peppers and other variations of the mouthwatering cuisine. The event kicks off Carnivale Weekend with tastings for the public from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. Soda Springs Park, 35 Park Ave. (719) 685-5089.

Four States Agriculture Expo

March 14-15 • Cortez

Agricultural heritage is rich in the Four Corners region of Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. Over 3,500 farmers and ranchers convene at this expo to preserve this way of life through educational seminars and product demos. Montezuma County Fairgrounds, 30100 Hwy. 160. (970) 529-3486.

Annie

March 24-26 • Colorado Springs

You’ll be fully dressed with a smile at the classic theatrical performance of “Annie” on Pikes Peak Center stage. Little orphan Annie will take the stage each night at 7:30 p.m. 190 S. Cascade Ave. (719) 477-2100.

The Grand Traverse Ski

March 29-30 • Crested Butte to Aspen Racers skate, ski and slalom their way across 40 miles, climbing over 6,800 feet up the rugged Elk Mountains. 12 Snowmass Road. (970) 349-1707.

An Afternoon with the Denver Zoo

March 30 • Denver

The Colorado Symphony Orchestra goes wild, inspired by the Denver Zoo’s furry friends. Zoo animals will join the stage as the music swells. Boettcher Concert Hall, 1000 14th St. (303) 623-7876.

Questions on pages 14-15

1 Secretary of the Interior

2 Mike Coffman

3 Populist Party or People’s Party

4 Native American (specifically Northern Cheyenne)

5 Hunter S. Thompson

6 a. Monkey Business

7 a. A moon rock

8 c. Joe Neguse

9 b. Greg Lopez

10 b. “Teflon President,” Ronald Reagan

11 True

12 False (He was Energy Czar; the Department of Energy was founded in 1977.)

13 True

14 True

15 False (A senior senator is the member with more years in office.)

Trivia Photographs

Page 14 Henry Moore Teller, Colorado’s longest serving senator

Page 15 Alva Adams, Colorado govenor

by ARIELLA NARDIZZI

HOT SULPHUR SPRINGS Resort and Spa offers a peaceful retreat steeped in history and 20 mineral-rich pools. The town of Hot Sulphur Springs, the Grand County seat, is tucked between Granby and Kremmling near Byers Canyon.

The Utes originally soaked in these sacred waters for their healing properties and utilized the land as a winter campground. In 1840, local newspaper founder William Newton Byers recognized the springs’ potential. He took ownership of the waters when he founded Hot Sulphur Springs in 1864. Seven natural springs feed the mineral pools. Heat from volcanic rock 35,000 feet deep spreads through fissures beneath the earth’s crust. The pristine water is untreated and completely natural, flowing down the mountainside from the pools, into the duck pond and eventually the roaring Colorado River. Over 200,000 gallons bubble up from the earthen springs every day to maintain water and mineral levels.

The pools, which range from 95 to 112 degrees, are rich in minerals. Calcium, chloride, fluoride, magnesium, potassium, sodium, sulfate and traces of iron and zinc rejuvenate the body’s skin, reduce pain and regulate blood pressure.

Each pool varies in temperature, minerals and views. A rocky alcove shelters the Ute Pool as a trickling waterfall cascading into the milky blue waters. Another pool boasts a heavy dose of magnesium, best for muscle relaxation and boosting energy levels.

Escape the cold and revel in the warmth of these mineral springs amid Hot Sulphur Springs’ snow-capped foothills this winter.

Ranch hands team up with skiers for Ridgway’s rodeo on snow

by TOM HESS

WHAT SOME CALL the odd couples of winter sports – cowboys and ski bums –travel from Ridgway to Craig to compete in rodeo on snow, otherwise known as skijoring: Norwegian for “snow driving.” Win or lose, crash-free or failure to finish, they form deep bonds on the snowpacked course.

Like a bucking bronc throwing off a rider in rodeo, a crash in San Juan Skijoring at the Ouray County Fairgrounds excites the spectators. If the skier loses his grip on the 50-foot rope that connects him to the speeding horse, and tumbles head over skis in the snow, the rodeo announcer will invite spectators to watch the big-screen replay – cheering for the day’s best crash.

The thrill of victory and agony of defeat play out all day long in Ridgway, a former railroad town with just over a thousand residents living under the shadow of Mount Sneffels, towering at 14,115 feet.

The San Juan Mountains have the biggest purse in Colorado skijoring, so cowboyski-bum-horse teams make certain to put the January event into their calendars.

Most skijoring events in Colorado run on a straightaway track, and teams finish between 16 and 18 seconds, double the

Richard Weber III, founder of San Juan Skijoring, opens each day by riding his horse, Frank and Beans, along the track in Ridgway. Later, he’ll join riders, skiiers and snowboarders to race for gold.

Justin Treptow

time of a rodeo bull ride at 8 seconds. The San Juan event is run on a longer course than most, 1,200 feet, and is shaped like a J.

Teams start at the bend of the J’s curve and end on its straightaway, the skiers and snowboarders swerving around 15 gates, each a foot high, at top speed of 40 miles per hour. Finishing times at Ridgway run 22-24 seconds.

Skijoring friendships take many forms at Ridgway: two Ouray County ranch hands, one a rider and the other a weekend snowboarder; a retired bull rider and a veteran Telluride skier; and a Ridgway earth-moving company owner who started San Juan Skijoring, winning most years.

Skijoring competitor, Josh Hunt, is a cowhand on a multigenerational cattle ranch west of Ridgway. A friend who works at the ranch next door, Brandon Mobley, is a weekender, after-chores snowboarder. Together with Hunt’s horse, Tiny, they formed a team called Pancho and Lefty. They didn’t crash for the cameras; they finished third in the San Juan’s Open Snowboard category, just under three seconds behind the winner.

Hunt said he’s never seen anything like the San Juan event.

“You got some guys like me that are just kind of ranch cowboys, associating with the kind of people that you wouldn’t normally associate with – the hippie dippy snowboarder skiers and everything in between,” Hunt said, “but it’s a welcoming community and a melting pot between two worlds that don’t normally intersect.”

Another skijoring friendship involves a former rodeo competitor and a former competitive skier. Skijoring has extended their time on horses and in ski boots.

“Skijoring is a second life for me, finding something that I could dive into competitively,” said Jed Moore, who retired from professional bull riding in 2010 after 13 years. He’s now a rodeo coach at Colorado Northwestern Community College in Craig. “I’m a competitor and love putting in the work during the week. When the weekend comes, we’re ready to rock and roll.”

Moore teamed up at San Juan with Tel-

Skijoring comes from skikjøring, a Norwegian word for “ski driving.” One competitor races the horse down the track while the other follows on ski or snowboard, pulled by the horse’s momentum. Experienced teams go full tilt, speeding down the track at 40 miles per hour.

luride veteran skier Kolby Ward. Ward won gold and $2,000 in the 2012 North Face Park and Pipe Open competition at Copper Mountain.

Moore said it’s an adjustment for both horse and rider to pull a skier by a rope.

“Some horses get nervous about the rope initially, but it’s all just something that they all get used to and, you know, after a few trips down the track, they get to where they really enjoy it,” Moore said.

Moore brought three of his quarter horses to Ridgway, and rode one, Dashes, to first place in the Sport Division category, pulling longtime professional skier Mike Gardner of Ridgway.

Moore appreciates the support he has received from the skijoring community. He broke his shoulder blade when his horse bucked him on a skijoring run. The injury reminded him of the broken

ribs he experienced in bull riding. “There were so many people volunteering their time to help me, getting my horses ready for the next run, giving me a boost onto my horse,” Moore said. “They helped pay medical bills.” The community support and devotion set skijoring apart from other sports.

in Ridgway for the past five years is Branden Edwards, of Grand Junction. He has narrated the action in other Colorado skijoring events in Meeker, Craig and Leadville. Rodeo announcing is his “bread and butter.”

Whether in the announcer’s booth for skijoring or rodeo, “our main job is to find the humor in the moment,” Edwards said. “That’s the stuff that’s genuine, that’s what people are drawn to.”

Skijoring is ripe for Edwards’ humor.

Skijoring is “old rednecks who have ranches and have a horse, and they think the horse is fast enough,” he said, “and a bunch of ski bums that are looking for a new thrill because they’re not going down slaloms anymore, and they’re not doing Olympic time trials.”

Edwards’ favorite skijoring moment came during the COVID pandemic.

For the January 2020 San Juan event, spectators weren’t allowed in Ouray County Fairgrounds. Spectators were locked out, but they didn’t give up.

“So many people lined both sides of the highway in their cars and had binoculars out to the point that the cops came in, asking people to move,” Edwards said. “They refused. Halfway through the day we turned our speakers around and pointed them out towards the highway.”

The fastest and most extreme event is the Open Skier Division. Top athletes race the hardest course with tighter turns and bigger jumps, including clearing a Toyota Tacoma.

THE IDEA FOR San Juan Skijoring belongs to Richard Weber III, whose company, Weber Welding & Excavation, builds roads and lakes and, otherwise, moves a lot of earth. He also operates a cattle ranch of Black Angus. Preparations for San Juan Skijoring begins in the fall with leveling the fairgrounds, eliminating gopher and prairie dog holes. Ten days before the event, trucks bring in the snow.

The snow is used to build up the track, 10 feet at its highest, with a gap for jumps that event officials measure. Parked in one gap is a Toyota Tacoma, the auto maker sponsoring the jump.

Just before the competition, a giant Jumbotron video screen is hoisted opposite the spectator stands. Everything on all three days is broadcast on Cowboy Channel Plus. Weber opens each day’s events by riding horseback around the track carrying an American flag, his horse’s speed lifting the flag on an otherwise windless day. Later he’ll compete. His primary competitor is his sister, Sarah Smedsrud. Two years apart, they’ve been “dog-eat-dog” adversaries since age 5 or 6, he said.

At San Juan, Sarah finished first in the Open Ski competition, ahead of Richard by 0.52 seconds. At an awards ceremony, she thumbed her nose at him; he responded by raising a certain finger.

Sibling rivalry aside, Sarah and Richard cheered all the winners, even those from out of state. They even cheered for Dennis Alverson from Montana, who took home a pot of Colorado’s money.

After the awards ceremony, at the historic Ouray Elks Lodge, Richard and Dennis and others played pool at Silver Eagle Saloon, a three-minute walk down Main Street, until 1:30 a.m. Richard’s feet had hurt, so he had taken off his boots. He learned later that Dennis had taken the boots, which were on their way to Montana in Dennis’ truck. Richard had only his socks on his feet, and it had snowed on Ouray’s sidewalks.

Richard rode piggyback to his parked truck and vowed revenge. He got it. Richard took Montana’s money, winning the Big Sky, Montana skijoring event. Sarah finished second. The rivalry continues.

whispers reverberate at night through Colorado forests and neighborhoods seemingly calling out, “Who goes there?”

These subtle and hauntingly beautiful echoes come from great horned owls hooting courtship calls. Mating season begins in late December and lasts about six weeks while nesting usually occurs in February and March. Recently, I was lucky enough to photograph a great horned owl perched in a tree from my own backyard in Loveland. Pictured here, the normally nocturnal animal is just waking up from a daytime nap.

With a 5-foot-long wingspan, the great horned is the largest owl species in Colorado – and the most common. Colorado Parks and Wildlife has documented great horned owls in every state park. Great horned owls have amazing eyesight with the ability to see in the dark 100 times better than humans. Their eyes don’t move in their sockets, so instead they rotate their head 270 degrees.

Despite their name, great horned owls don’t have horns. They display horn-shaped tufts of feathers called “plumicorns” on their heads. Special filaments on their wing feathers allow them to fly silently to sneak up on large prey such as skunks, rabbits, squirrels or other birds like hawks and waterfowl. Great horned owls can live for more than 20 years, feeding on an impressive number of animals that humans consider pests.

Though not as closeup as this great horned owl, I’ve seen other owls in Colorado. These include cute, diminutive boreal owls in the high country, burrowing owls from prairie dog towns of the Eastern Plains, barn owls which inhabit their namesake, and screech owls which favor riverbank riparian areas. Occasionally, snowy owls are known to visit as far south as Colorado during winters when their arctic food sources are scarce, though I haven’t had the privilege.

Owls are only some of the birds of prey that winter and nest deep into spring in our region. Statewide, hikers and rock climbers may come across closures of their favorite trails or crags to protect nesting raptors. For example, bald eagles annually return to a communal roost site near the Colorado River on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park. From Nov. 15 through March 15, the park closes a 300-yard-wide zone on both sides of the East Shore Trail for the migrating eagles.

Barr Lake State Park is a popular place to view bald eagles close to the Denver Metro Area. Near the intersection of Interstate 76 and E-470, the park’s 2,715 acres surround a reservoir lined with cottonwood trees and marshes where eagles love to congregate. Plentiful boardwalks and blinds give people places to peacefully observe the birds. The 124th Audubon Christmas Bird Count, a yearly event which extends into early January, counted more than 150 bald eagles at the park.

Golden eagles prefer the rugged cliffs of the Western Slope and canyons of the state’s southeast corner. Year round, they can be found in the state’s central regions, like the foothills surrounding Canõn City. Hawks are also easily viewable along the Front Range and Eastern Plains. Birders identify the “big four” of these raptors as rough-legged hawks, Swainson’s hawks, Ferruginous hawks and red-tailed hawks.

One of my favorite places to look for hawks is the Raptor Alley Route, a series of loops around the towns of Nunn and Pierce near Pawnee National Grasslands. Though some trails into the grassland may be closed for nesting raptors, the crisscrossing roads offer a perfect perch to view birds conveniently from the car.

The American kestrel, also called a sparrow hawk, is the smallest and most common falcon in North America. Their broad diet typically consists of grasshoppers and other insects, lizards, mice and small birds. Birders study these attractive rusty-andblue-feathered raptors at Kestrel Fields Natural Area in Fort Collins and Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Commerce City.

A kestrel cousin, the peregrine falcon is known as the fastest animal in the world. These sleek hunters can reach speeds of more than 200 miles per hour in dives that pluck prey anywhere from rooftops to open fields. While peregrines reliably nest in places like the rock spires of Staunton State Park near Conifer, excited avian aficionados spotted the falcons among the skyscrapers of downtown Denver for the first time in 2024.

With so many raptor species living amongst us, there are ample opportunities to find our feathered friends in any part of the state. You might not have to go farther than your own backyard to see them hard at work, snatching rodents in our subdivisions into their talons, or even taking a well-deserved daytime snooze.

JOSH SHOT THIS photo of a greathorned owl in Loveland with a Nikon D500 and Nikon 200-500mm lens at 500mm, exposed at f/5.6, 1/5000, ISO 400.