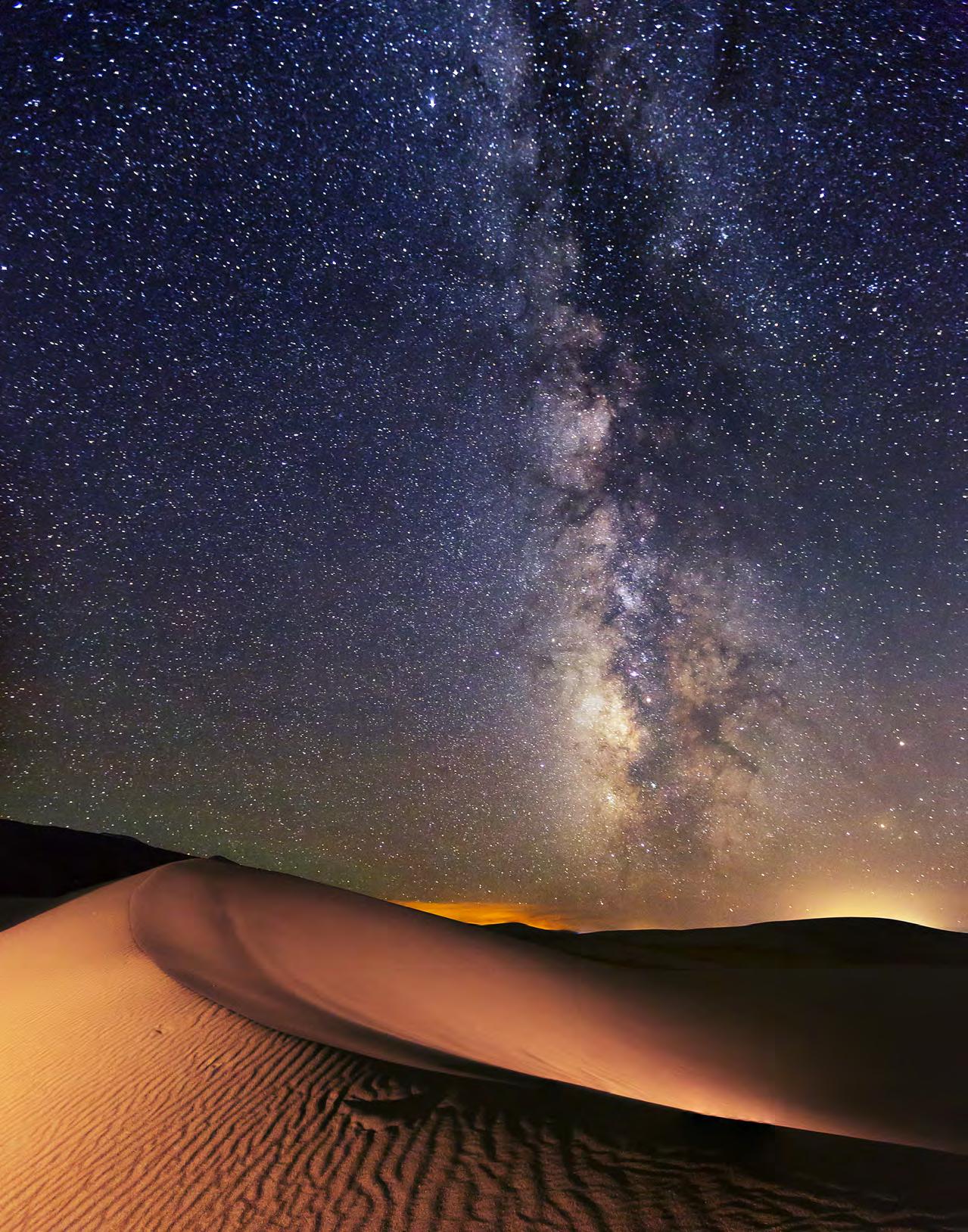

The Milky Way inspired this photographer to seek the wonders revealed after the sun sets.

By Glenn Randall

The Denver Botanic Gardens offer aroma therapy for urban dwellers. By

Tom Hess

North Park is known for moose. Residents simply look out their front door.

By Tom Hess

Colorado Springs chef Brother Luck is drawing the roadmap to elevated regional cuisine. By

Tom Hess

Publisher

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Creative Director

Darren Smith

Senior Editor Tom Hess

Senior Designer

Jennifer Stevens

Production Assistants

Victoria Finlayson

Lauren Warring

Advertising Sales

Marilyn Koponen

Subscription

Carol Butler, Janice Sudbeck

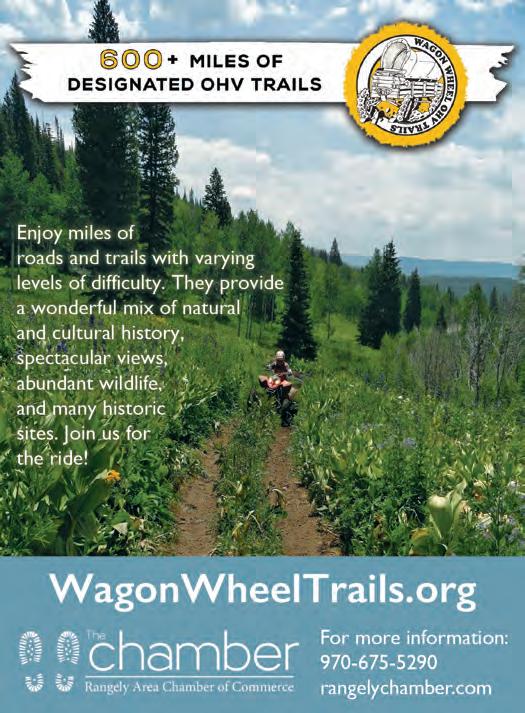

Help make Colorado a safer place to play when you buy a $29 Keep Colorado Wild Pass with your next vehicle registration.

Your pass purchase can support search and rescue and avalanche safety teams across Colorado — paying it forward to the outdoor first responders who have your back.

cpw.info/KeepColoradoWildPass cpw.info/KeepColoradoWildPassSpanish

ON OUR COVER

Park Range Ranch cowhand Scott McKay (white horse), his dog Ty, and cowhand John Guthrie III cross the North Platte River. Story begins on page 30.

CAROL M. HIGHSMITH

Dolores, pg. 58

8 Sluice Box

A Salida artist paints animals with eyes that “bounce;” Springfield keeps its historic theater open to help its kids; a 1917 Larimer County cabin offers a kind of time travel.

12 Trivia

Step carefully through a quiz on Colorado’s mud season.

40 Poetry

Storms stir the hearts and sharpen the vision of Colorado poets.

Walden, pg. 30

Salida, pg. 8 Alamosa, pg. 16

Fort Collins, pg. 10

Denver, pg. 22, 52

42 Kitchens

Pie for dessert will elevate any dinner.

52 Go. See. Do.

Replicas of orcas seem to float in the Denver Museum of Nature & Science; take a spin on a carousel in Burlington.

58 Camping

Visit Canyons of the Ancients National Monument in southwestern Colorado.

62 Peak Pixels

Spring flowers entice pollinators from afar to Colorado.

Colorado Springs, pg. 46

Burlington, pg. 54

Springfield, pg. 9

Colorado Life Magazine PO Box 270130 Fort Collins, CO 80527 970-480-0148

ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1 year (6 issues) for $30 or 2 years (12 issues) for $52. Please call, visit ColoradoLifeMag.com, or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and corporate rates, call or email subscriptions@ coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@ coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, visiting ColoradoLifeMag. com or emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2024 by Flagship Publishing Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

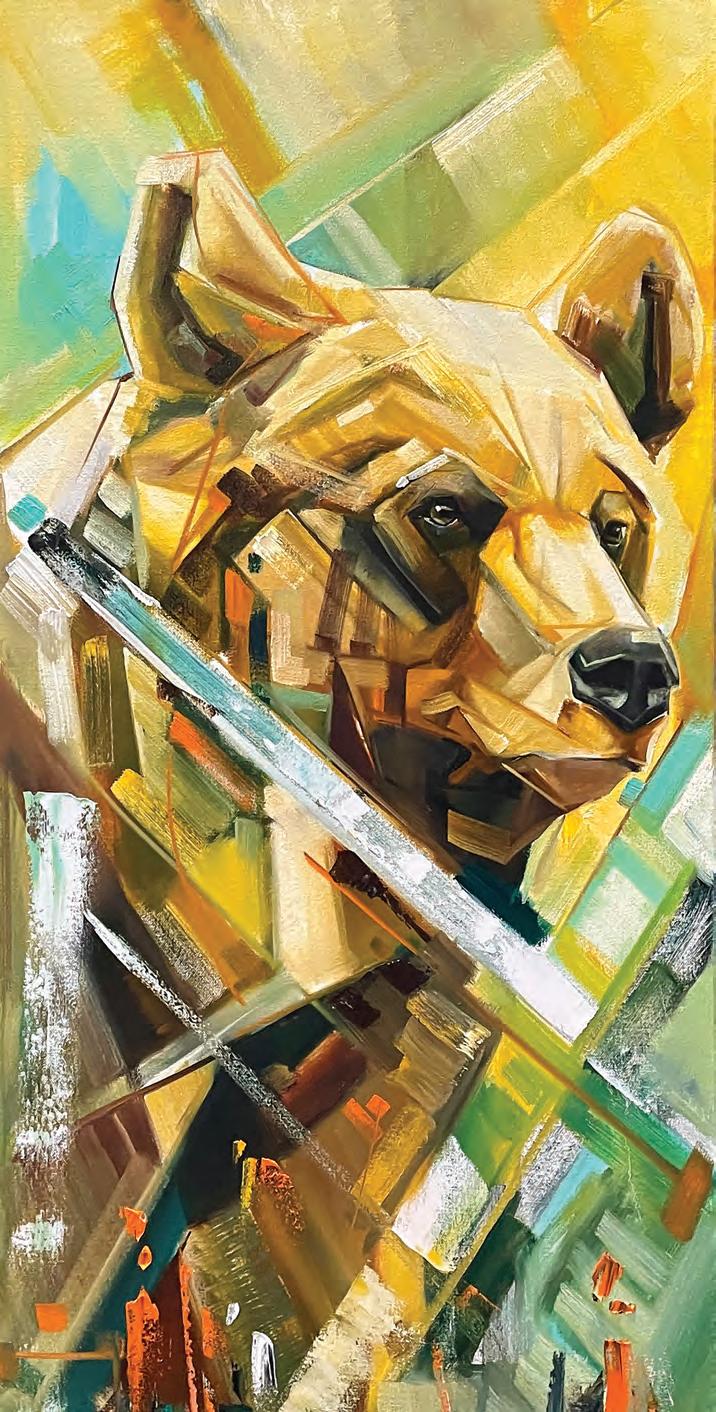

by MARJORIE ACKERMANN

On a frigid morning in 2008, artist Katie Maher peered at the snow swirling outside the log cabin she had rented near Gunnison. She spied a bighorn sheep hunkered down in a drift on a slope above the cabin. The lone ram returned to the same spot every day, pawing at the snow to forage grass and bed down. Captivated by its massive, curved horns and solitary manner, Maher knew she had to paint it. Her journey capturing Colorado’s wildlife on canvas had begun.

Originally from Iowa, Maher had just moved to Colorado, lured by its wide-open spaces and wilderness. Fifteen years and thousands of paintings later, a tiger stares out the gallery window at Katie Maher Fine Art in downtown Salida. Its amber eyes are piercing, almost hypnotic, and the cat vibrates with bold colors and brush strokes.

Maher calls her unique style “fractured,” and it literally reflects the way she sees the world due to an eye condition known as accommodative lag. Her eyes perceive movement in stationary objects. Her paintings shimmer with motion and energy.

“I notice when I chop things into geometric shapes and flip warm and cold colors, it starts to vibrate in your vision and look like movement,” she said. “It’s a live animal; I want it to look alive.”

A reference photo of a moose glows from a computer screen to the left of Maher’s easel as she begins work on a new painting. Dancing to a hip-hop beat, she works quickly, first outlining the animal, then brushing

By using large brush strokes with warm and cold colors juxtaposed, Maher makes her art “bounce” as if it is a alive. Her subjects reflect her love of Colorado wildlife.

in swaths of color, oils running down the canvas, filling in the animal’s features and background. She focuses on the eyes, trying to capture the soul of the animal.

Drawn to Salida’s artist community, Maher moved to town in 2011 and first opened a tattoo parlor – a skill she learned in Gunnison. The small town embraced her, including “the little old ladies who came after church for tattoos of crosses and doves,” she said.

After inking thousands of tattoos, other Salida artists encouraged her to return fulltime to painting, and in 2016 she opened her gallery. As a tattoo artist, she was used to working precisely and up close. Artist Carl Ortman helped her reinvent her style of painting. Handing her huge brushes and giant blobs of paint, he placed her palette on the other side of the room, forcing her to walk across the room, scoop up some paint on her brush, walk back to the canvas, do a few brush strokes, then walk away. “It made me paint faster and freer,” Maher said.

Carol and Alan Kelly happened into Maher’s studio a few years ago and thought her work would be perfect for their Portfolio Gallery in Breckenridge. She is now their best-selling artist. “Katie’s work is original, stunning and captures the spirit of Colorado’s magnificent animal and bird population,” Carol said. “The technique of fractured geometry makes you look twice at every piece – to see not only what is ‘in the piece’ but also ‘what has been left out.’”

Their Breckenridge gallery sells nearly everything Maher paints, so she now sells canvas and metal prints at her own gallery and through her website, katiemaherfineart.com.

After discovering Colorado, Maher says she is “overwhelmed” by how her life has evolved here. Seeing the world through different eyes has made all the difference.

Capitol Theatre isn’t just a youth jobs program. Patrons say it serves the best pizza in town.

Springfield won’t quit on its kids, nor its movie theater

by TOM HESS

Adults say there isn’t much else for youth to do or to keep them in Springfield, a southeastern Colorado town of about 1,400 in Baca County, which borders three states – Kansas, New Mexico and Oklahoma. Springfield considers itself the “Capital of the Dust Bowl” that devastated the region in the 1930s.

There’s a Capitol (Capitol spelled with an “o,” Theatre ending in “re”) in Springfield, too – the Capitol Theatre. Community leaders work hard to keep the Capitol open because the next closest theater outside Springfield is in Lamar, 47 miles north in Prowers County. That’s a long distance for car-less teens looking to show colleges and future employers their work ethic.

At the Capitol, kids can volunteer, get free popcorn and a Coke and watch movies. Capitol Theatre shows movies Thursdays through Sundays.

Converted from a livery stable built in 1927, Capitol Theatre passed through many hands over the years. Ike and Ruby

Ross purchased the Capitol in 1963, along with the Kar-Vu Drive-In, and formed Baca Theaters. After Ike’s death, Ruby owned the Capitol till 2000, when she sold it to Trent and Anna High. Kar-Vu Drive-In closed after high winds blew out the screen; Dollar General stands in its place on U.S. 287 south of downtown. Pamela Saldana owned the Capitol in 2008 when the fire at the entrepreneur’s other business, Hometown Burrito, broke out at 2 a.m. and killed her and her family.

In the next few years, the ranching and farming community held fundraising barbeques and auctions to fund improvements, such as digital projection, replacing metal-framed wooden seats that had no cup holders with cushioned, cup-holding ones, heating and air conditioning, commercial-grade refrigeration, and more.

The theater serves pizza using the recipe first developed by the late Ruby Ross of Baca Theaters. It’s the favorite local pizza of hometown newspaper publisher Kent Brooks of the Plainsman Herald.

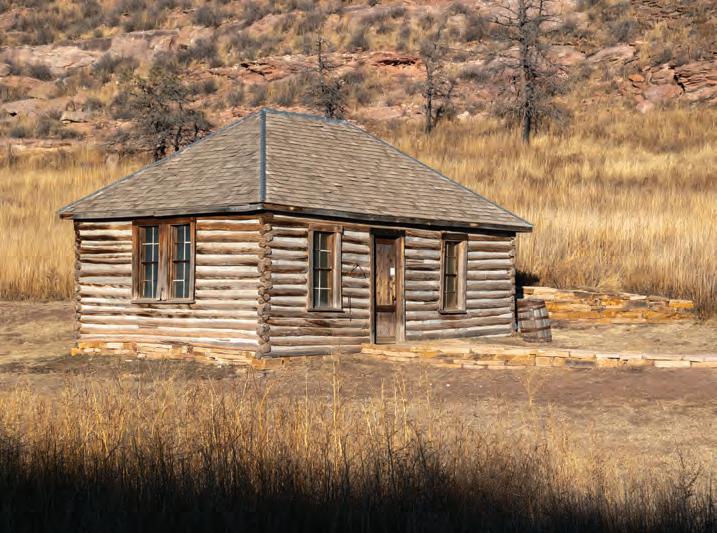

by DEAN ALLEN

The hogbacks of Bobcat Ridge Natural Area near Masonville separate a quiet and lonely glade from the sprawling Front Range towns of Loveland and Fort Collins. These sharp ridges have always separated people, isolating early settlers who arrived in the valley through Buffum Canyon.

Hardy folk who chose to settle west of the ridge lived among sweeping grass, cottonwood trees and the forested mountain slopes. They raised their families and birthed cattle here until the 1950s, after which the land went through a variety of owners until 2003, when Fort Collins purchased it.

Today’s valley visitors hike, bike, or ride horseback to a little cabin nestled in a low draw. Constructed in 1917 by the Kitchen family, the cabin is a journey of the imagination, entering a forgotten time. A collection of antique food cans with brand names such as Rawleigh’s Pure Ground Allspice and The Best Elton’s Stone Ground Flour line the kitchen hutch.

I’m fascinated by the dirt floor, handhewn and chinked log walls, and yes-

teryear appliances. One of them is an old wooden “Birthing Chair,” six inches wide with a tall back. Women would lean against it, supporting their lower back through the exertions of labor.

Settlers raised animals here, slaughtered them, and their families ate heartily. Children grew up and had their own children, mothers birthing them in the chair. Families lived each day, month and year in a perpetual present with each other.

A visitor accustomed to modern busyness on the other side of the ridge might pause in this stillness and experience what settlers did, the air they breathed, the dust they smelled, the sounds they heard –they’ve been here all along.

That’s when you recognize the miracle of living. I’ve been asking myself, “What would it mean to feel as if I were living my life to the fullest?”

This.

Experience historic charm at Frisco Lodge. Our exceptional hospitality, a ernoon wine and cheese, award winning courtyard, outdoor hot tub and romantic replace are just a few reasons our guests rated us the #1 bed & breakfast in Frisco and all of Summit County!

See why our guests think we are the best

www.friscolodge.com 1-970-668-0195

321 Main St | Frisco, CO

questions by BEN KITCHEN

1

Which of Colorado’s national parks is starting a timed-entry reservation system on May 24 and ending it in October to avoid overcrowding in the summer? As a result, going in mud season means you won’t need a reservation.

2

One way to avoid getting muddy is to not touch the ground! In mud season, the Colorado Adventure Center recommends their Sky High Combo in Idaho Springs, a package of two activities that’ll keep you well above ground level. Name either.

3

Several sources say Colorado’s mud season is a great time to visit what natural features historically used for their medicinal properties? Examples are in towns with names starting with Glenwood and Pagosa.

4

What’s the name of the river running through Steamboat Springs? During mud season, the city’s website recommends using a paved trail alongside the river.

5

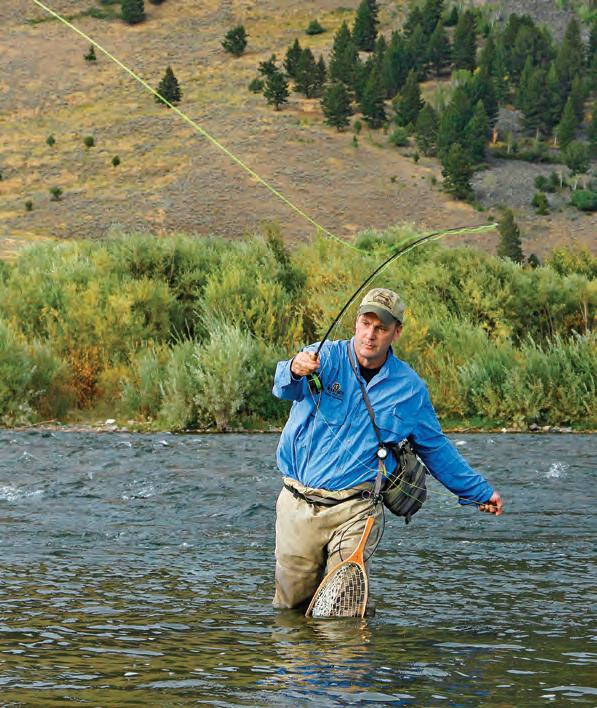

Lisa Blake at ColoradoInfo recommends going fly-fishing in mud season because it is during spring when the rainbow and cutthroat varieties of what fish are spawning?

6

Mud season is occasionally referred to by what body partinspired name? The name is also used for parts of the fall, though the fall isn’t nearly as muddy.

a. Head season

b. Shoulder season

c. Knee and toe season

7 According to a 2022 Axios Denver article, which of the following is not a reason to stay off the trails during mud season?

a. In trying to avoid mud, people trample plants

b. The sound of footsteps in the mud can scare away wildlife

c. Walking on a muddy trail can cause it to erode faster

8

One way of avoiding getting muddy is to stay away from dirt. Great Sand Dunes National Park is a popular destination during mud season because melting snow fills what creek that only runs through the park in the season?

a. Daemon Creek

b. Emodan Creek

c. Medano Creek

9

While most of Colorado’s ski areas typically shut down in April, which one is frequently open until early June, making it skiable during mud season? It was the last to close last year.

a. Arapahoe Basin

b. Hesperus

c. Ski Cooper

10 Crested Butte’s website recommends an activity it abbreviates SUP during mud season. What does SUP stand for?

a. Seeking unusual pastimes

b. Sleeping under the Pleiades

c. Stand-up paddleboarding

11

Grand Junction’s mud season is particularly brutal: trails in and around the city get so muddy that they’re entirely shut down from early March to late July.

12

One upside of mud season is that hotel prices in some ski resorts drop substantially. One of the starkest differences is at the Park Hyatt Beaver Creek: per a 2021 5280 article, nights there average $900 during peak season but just $199 in mud season.

13

The melting snow that heavily contributes to mud season’s muddiness also helps to fuel Colorado’s rivers. Since the mud keeps tourists away, this makes mud season a great time to go whitewater rafting.

14

The 2012 Matthew McConaughey movie Mud is set in a fictional Colorado mountain town and tells the story of a tourism director trying to get people to visit in mud season.

15

The Telluride Film Festival was established to boost tourism to Telluride during mud season, which is why it’s always held the first weekend of May.

EXPERIENCE the splendor of the Rockies at Aspen Winds. The secluded setting along Fall River offers a relaxing atmosphere among the aspen and pines. Aspen Winds is located minutes from Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park. We offer one and two bedroom suites and in-room spa suites.

tc hen/Ki tchenettes • Gas Fire pla ces Fire Pit

05 1 Fall River Cour t • Es t es Par k, CO ASPEN

Send your taste buds on a statewide tour of Colorado with our Best of Colorado Life Recipes cookbook. Try over 90 recipes including mouth-watering mains, creative sides and delicious desserts spanning 76 pages.

The Milky Way inspired this photographer to seek the wonders revealed after the sun sets

spent nine hours

GLENN RANDALL

At its best, wilderness landscape photography captures moments of awe. I began pursuing those moments professionally in 1993.

For nearly 15 years, I made virtually all of my images during daylight hours. When the sky grew dark, I put my camera away. No film camera was capable of capturing the night sky as I saw it.

In addition, the idea of shooting landscape photographs deep in the wilderness at night was rather scary.

Then, in the mid-2000s, I began experimenting with the new-fangled digital cameras. By the early 2010s, anyone with a relatively new digital camera, a tripod and a fast, wide-angle lens could make photographs at night that film photographers could only dream of.

Armed with a new camera, I knew it was time to overcome my fear of the dark. After all, awe is often tinged with fear. What could be more awe-inspiring than photographing the Milky Way, a comet, a lunar eclipse, or a meteor shower over one of Colorado’s magnificent peaks?

I clearly remember my first nighttime shoot, deep in the Colorado wilderness. It was August 2012. I put my new Canon 5D Mark III to the test: a shot of the Milky Way taken from the summit of 14,267foot Torreys Peak.

I had waited for a day with good weather followed by a night with no moon. When a weather window opened, I drove to the trailhead and hiked the steep trail to the summit. I met a few people heading down as I was heading up, but when I reached the summit, I was alone.

I shot sunset, then settled down to wait, trying hard to stifle my unease.

Slowly, the few remaining clouds dissipated, and the stars began to come out. The silence was profound. Then the glowing heart of the Milky Way, the center of our galaxy, emerged directly over Grays Peak, another Fourteener.

Never before had I seen the most spectacular part of the Milky Way from such a dark and elevated perch. The sight was breathtaking. I left the summit about mid-

night as the best part of the Milky Way set to the southwest. Two hours later, I reached my truck. Two hours after that, I collapsed into bed after a 21-hour day.

I examined my images later that afternoon. They were far from perfect. Today, as I look back at them, I can see how improved cameras and lenses, better software, and a deeper knowledge of planning, shooting, and processing night images would allow me to make much better images should I ever return to the summit of Torreys Peak. Despite the obvious flaws, the potential for ground-break-

ing new images was clearer even then, and I embarked on a series of night shoots to take advantage of the new technology.

In the dozen years since that first shoot, I have spent many magical nights under the Colorado stars. Sleep is for photographers who don’t drink enough coffee.

For my first shoots, I concentrated on photographing the Milky Way, particularly the galactic center, the Milky Way’s brightest and most photogenic part.

The Milky Way is the easiest and most beautiful subject for a novice night photographer. In Colorado, the Milky Way season

runs from about March 1 to Oct. 1. This is the time of year when the galactic center is above the horizon during the period between astronomical dusk and astronomical dawn, when the Colorado sky is as dark as it will get.

My advice: First seek out a location as far from city lights as possible. Go on a moonless night. Consult a desktop app like Photo Ephemeris (you’ll need the Pro version) or a mobile app like PhotoPills or Sun Surveyor (available in both iOS and Android) to get information on the times of astronomical dusk and dawn, when the galactic center will rise and set, and its location in the sky. In Colorado, the galactic center can only be seen in an arc from southeast to southwest. Its exact position depends on time of night and time of year.

Bring your camera, a tripod, and your fastest, widest lens. A 16-35mm f/2.8 lens set to 16mm is ideal. You can rent such a lens if you don’t own one. Arrive in daylight so you can focus your camera and scout out any possible hazards. Then set up and wait. Try an exposure of 30 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400. You may be astonished at what your camera can capture.

For a complete guide to making professional-quality images at night, check out my book Dusk to Dawn: A Guide to Landscape Photography at Night, 2nd edition, published by Rocky Nook.

The night sky offers many photogenic subjects besides the Milky Way. Consider the Perseid and Geminid meteor showers, which arrive like clockwork every August and December. A good meteor shower, viewed from a dark location on a moonless night, is nature’s most spectacular fireworks display. Lunar eclipses and comets are rare but even more spectacular.

Subscribe to an astronomy newsletter (I like EarthSky) to learn when the next lunar eclipse will occur and when a bright comet is approaching Earth. You can even shoot star trails, which capture the graceful arcs inscribed in your photos by the stars as Earth rotates. Once you begin venturing into the dark, you’ll lose your irrational fear of things that go bump in the night and experience awe in a way you could never imagine.

For more information on Randall’s work, please visit glennrandall.com.

by TOM HESS

In Colorado wilderness photographer Glenn Randall’s new edition of his 2018 book on landscape photography at night, he says up front that he expects that the reader will know the fundamentals of photography: camera, lenses, focus, composition.

Readers who don’t know much about the difference between aperture and f-stop will want to read the book anyway, because it is filled with spectacular nighttime photography of the Milky Way arching above Colorado landmarks: Mirror Lake in Indian Peaks Wilderness, Missouri Mountain in the Sawatch Range, Mt. Antero, and many more.

The words can get a bit technical, but there are interesting tidbits for the novice. Randall mentions fear of wildlife at night, and from his experience, offers reassurance.

“I was hiking out from Lost Remuda Basin in the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness, alone, at night, when I was suddenly terrified by the thunder of pounding hooves,” Randall writes. “An entire herd of elk had bedded down next to the trail and been spooked by my approach. The herd leaped to its feet and sprinted across the trail in front of me. I was astonished that elk could run so fast in the dark without breaking their legs.”

Navigating wildlife at night requires care. So does photographing the Milky Way and surrounding scenery.

“Shoot the land just before moonset, when the moon will be approaching the western horizon and providing good texturing light on the land as you look southeast toward the Milky Way, then shoot the Milky Way after moonset,” Randall writes.

Judging from his images, and his survival, Randall’s advice is spot on.

Dusk to Dawn: A Guide to Landscape Photography at Night

Glenn Randall

Rocky Nook, 232 pages, $40

The Denver Botanic Gardens offer therapy for urban dwellers

The Gardens boast over 50 curated gardens that feature both native and adapted plants from the

Denver Botanic Gardens cover 24 acres alongside York Street in the Cheesman Park neighborhood of Denver, the land a former burial ground that’s now filled with trees, plants, flowers and other ground coverings from all over the world. This is where a Denver International Airport employee said he finds rest three or four times each summer.

People who fly in the window aisle on United Airlines to Concourse B at DIA and look out at the tarmac below might see Jonathan Millett, helping unload luggage from a nearby Boeing 787. Whether it is minus 16 or 110 above outside, raining or snowing, he’s certain to keep luggage in sync with their owners in making a tight connection, something he’s done for 16 years.

Millett likes his job, but today, he is seated on a shaded bench at the Gardens, relaxing. This is his spot to unwind.

The park offers 170 benches and 10 chairs on which visitors can rest, reflect and renew. The Boettcher Memorial Trop-

ical Conservatory opened in 1966, yet it is the peace of the outdoors that Millett and others sought out.

The peace begins at the Gardens’ entrance. A Sensory Garden, run by a horticultural therapist, is the first stop but just one stop in the journey that the Gardens offer to relieve the stress and busyness of Denver urban life.

Millett was born in Littleton, attended Arapahoe High School in Centennial, enrolled in what is now Metropolitan State University, and now lives in an apartment in Aurora. He mowed his lawn growing up, but he’s free of that now. He enjoys the beauty of the Botanic Gardens, without having to do the yardwork. The garden is peaceful.

“Maybe that’s why I like it so much,” Millett said.

The Sensory Garden is run by Angie Andrade, Associate Director of Horticulture and Therapeutic Horticulture Program for the Gardens. She grew up in Castle Rock, growing and eating tomatoes and snap peas that she started inside and transplanted after Mother’s Day.

Volunteers are an important part of the Gardens’ mission to help people connect with plants, opportunities ranging from welcoming and educating visitors to planting (top).

The

benches on which visitors can rest, reflect and renew.

As a child, Andrade joined a field trip to the Gardens. “It was magical, otherworldly, with big trees and secret areas,” she said. “It takes you out of your head.”

Andrade’s Sensory Garden is magical for visitors. A group of Boy Scouts can’t believe that a yellow flower in the sensory garden smells like buttered popcorn. The peppermint geranium smells like peppermint. And then there’s lemon balm and cinnamon basil.

Andrade has worked at the Gardens for 20 years. “Gardening is a relationship,” she said. “You have to check everybody out every day. It’s not a schedule; it’s observing.”

She observes visitors’ reactions as well, watching for a change of behavior, and she often sees it, because the visitors are outside, in nature. They have arrived stressed, and now they show signs of delight.

Elsewhere in the Gardens, a Westminster High School graduate now in his 22nd year with the Gardens is delighted to tell a visitor how his work deepens his appreciation of life in Colorado.

Mike Bone is the Associate Director of Horticulture and Curator of the Gardens’ Steppes Collections. Steppe is a word in both German and French, derived from a Russian word, for a flat, grassy, arid plain, typically in the rain shadow of mountains.

Denver is at the western edge of the Great American Steppe, what most people think of as the Great Plains.

As a kid, Bone visited his grandfather’s farm in the panhandle of Texas, where he learned to love the outdoors. His dad, a schoolteacher, took him on frequent summer trips in Colorado: to the southern Rockies, Guanella Pass in Clear Creek County, Fairplay, South Park and the Arkansas River drainage, where he learned to camp, fish and hunt.

As an adult, Bone worked at Miller Landscaping, at 70th and York, where he learned about controlled environments and mechanical spaces. Then, at a wholesale nursery, Nursery Green Acres in Golden, he discovered what plants grow

Visitors are encouraged to use their five senses at the Gardens, whether it is discovering texture, inhaling the smells or simply resting along the paths.

and survive in the Front Range environment. Both businesses have since closed.

In his 22 years at the Botanic Gardens, Bone has traveled to climates around the world similar to Denver’s: arid regions of central Asia, South America and Southern Africa. He spent three weeks in 2018 gathering seeds from Lesotho, a land-locked African nation featuring a steppe, the

Drakensberg escarpment. The seeds Bone brought back from Lesotho grew in Denver. That realization tugged at Bone’s soul.

“I feel a genetic pull to the steppe, an ancient, human genetic pull,” he said. “Humans migrate through steppes. The Silk Road ran along a steppe.” And Bone isn’t the only one who sees it, senses it.

“Visitors ask us all the time, out of natural curiosity, what is that plant,” Bone said. “I’ve had people come up and say, ‘I think I know what that plant is, it’s a summer hyacinth. I saw it on a hillside in South Africa.’” Steppe brings humanity together, Bone said.

Denver Botanic Gardens partners with Colorado State University on Plant Select, a non-profit organization that offers plants that can thrive in Colorado’s steppe environment. The selection is in part informed by Bone’s work.

Bone travels with another Gardens staffer, Kevin Philip Williams, Manager of Horticulture. Williams oversees many gardens, like the Dwarf Conifer Collection. There are more than 50 themed gardens at Denver Botanic Gardens, which is why the name is plural.

Williams is excited by the Gardens’ efforts to create environments that closely

match what plants, flowers and trees would experience in the wild, as opposed to a traditional garden. He’s helping establish a dwarf conifer environment in a section of the park that matches a Colorado montane. Surrounding the conifers are what you would expect to see where they grow, between 7,000 to 10,000 feet elevation, with dry understory and rocky terrain.

Next to the conifers is a willow glade that will eventually include all 40 known species of willow in Colorado, from the South Platte to Cottonwood Pass. Williams travels with Bone, the steppes collector, gathering willow cuttings on federal lands, with the agencies’ permission.

“Willows are important host plants for everything from flies to moose,” Williams said.

With the diverse gardens on 24 acres, some with rare species, how does Williams protect more vulnerable plants?

“We curate, we edit,” Williams said. “I prefer that the species have self-autonomy. I want to partner with plants to make decisions in their own way. I let species flow. But if Columbines are overwhelming rare plants, I’ll use our territorial hand.”

Williams said his Botanic Gardens work, going on 10 years now, is inspiring him to curate the front and back yards of his Sherrelwood home in Westminster.

The front yard is what he calls a cool ranch thicket, like a meadow – a mix of sumac, mahogany, thick shrubbery, grasses, perennials and annuals. The shrubs will grow in the next five to seven years, and others will be interstitials.

The backyard will be Iggy’s Herb Meadow, named for his Jack Russell terrier and the plants Williams is establishing. “We’re hoping he runs through sage and scented plants, and comes back smelling nice,” he said.

Williams will have the option of Iggy smelling like peppermint, or popcorn.

North Park is known for a large, curious animal that can make you late for work.

by TOM HESS

Park is home to many transplants from across the nation, including the now largest herd of moose.

North Park and Jackson County are virtually one and the same – an over 8,000-foothigh basin that forms the headquarters of the North Platte River, its waters running downhill to its next-door neighbor, Wyoming.

Feeding the North Platte are the snows from the mountain ranges that surround North Park: Park and Sierra Madre to the west, Never Summer and Rabbit Ears to the south, and Medicine Bow to the east. Roughly in the middle of the basin is the town of Walden, seat of Jackson County, and ground zero for Colorado moose and not a lot of humans. The park’s population is 1,316; the county’s, 1,363. The county’s square mileage is 1,613. That equals about one person per square mile.

Moose arrived in North Park in 1978 when the then-Colorado Division of Wildlife (now Colorado Parks & Wildlife) transplanted 24 animals from Wyoming and Utah, hoping the moose would breed and thrive. The moose obliged and now number about 3,000 statewide, the healthiest herd in the country.

Like the moose, some people come to North Park from elsewhere, see the wideopen spaces, stay and thrive.

An Oklahoma millionaire who saw this isolated place envisioned regaining a treasure that America had lost: the Old West. He bought a 3,000-acre ranch on the eastern edge of the park and began building a 107,000-square-foot log cabin that 20 years later is still under construction. He purchased buildings in downtown Walden. He constructed the Western lodge-style River Rock Cafe and Antlers Inn in town, using logs he shipped from Canada, on the site where an outdated restaurant, the Coffee Pot, burned to the ground in an electrical fire in the early 2000s.

Another transplant to North Park, a California chef, arrived in his 50s and knew right away that he belonged in the park more than he had anywhere else. He later served a term as mayor of Walden.

A North Park native who grew up in rural Jackson County, riding her horse to

a country school, never wants to leave, either. Her family moved away for a time to Meeker but returned to Walden. “This was my home, and I didn’t ever feel safe and secure anywhere else,” said Nadia “Tootie” Crowner.

Crowner calls North Park “God’s country” for its clean air, open spaces, sometimes friendly moose, and friendlier people. The moose make themselves at home in Walden. “A young bull sleeps at the courthouse, he sleeps in my driveway, he’s over on main street,” Crowner said.

Crowner – just call me Tootie, she says – meets on the sidewalk outside the River Rock Café on Walden’s main street with her longtime friend, the California transplant and former Walden Mayor James Carothers. He’s got a moose story, too.

“I walked out of my house, and coming around the corner of the garage, and … hello moose! He’s standing right there in the yard.”

The native Crowner and the transplant Carothers speak highly of Jim Moore, the Oklahoma millionaire. Moore helped Carothers with the restaurant he owned when the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the economy. Moore provided tables and chairs for people to eat breakfast provided by the Lions Club cook wagon after the Coffee Pot burned down and while work began on the new cafe. Moore sponsors Walden’s Christmas celebration.

The historical anchor of Walden is a grandiose 1913 courthouse. The building seems like it belongs somewhere else. Maybe that’s because the Jackson County

courthouse was designed by a Colorado architect who also designed a Front Range County courthouse in Greeley, pop. 109,323, and the City and County Building in Denver, pop. 711,463.

Walden’s population, around 600, is less than Silverton, county seat of the least populous county in Colorado, San Juan. That’s plenty of room for moose to roam. And that’s exactly what they do, anywhere they very well please. That’s what architect William Bowman’s design sketches of the Jackson County courthouse didn’t anticipate – moose lingering on the lawn surrounding his courthouse.

Ekho Wyatt, the county treasurer, said her co-worker, who preferred not to talk to a reporter, called in late for work one day because a moose was on her porch

across the street. A moose had also attacked her miniature poodle.

Why do moose attack dogs? “They smell like wolves,” Wyatt said. Lately, wolves have begun attacking and killing cattle and dogs in North Park, home of Walden and Jackson County. “We can’t defend ourselves,” Wyatt said. “We can’t kill them.” Colorado law protects wolves.

Moose stroll casually among Walden humans from April to the middle of July.

Born in Fort Collins, Wyatt values North Park outdoor recreation. She and her husband camp three weekends a month in summer along various local creeks: Indian, Camp, but especially Sawmill. She catches Brook trout, “brookies,” she calls them, rolls them in flour or cornmeal, and fries them.

She intends to stay in Walden. “I just want to breathe,” she said. “Everything is perfect up here.”

Behind Wyatt’s office at the courthouse, on the same block, is the North Park Pioneer Museum, displaying some of what Walden has lost, a beloved movie theater, and those it remembers, an accomplished artist. The building itself has history. It began as a cabin in 1882, moved to Walden in 1961 and opened as a museum in 1963.

The Park theatre opened in 1946, with 350 seats – about half the current population of Walden – its first film The Big Sleep starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren

“This was my home, and I didn’t ever feel safe and secure anywhere else.”

– North Park native Nadia “Tootie” Crowner

Bacall. The museum displays The Park’s two Western Electric Simplex E-7 movie projectors, massive devices, each weighing several hundred pounds. Two were required because the projectors ran 20-minute reels of film. Also in the museum is The Park’s popcorn machine.

On the walls of the museum are paintings by North Park artist Raphael Lillywhite, 1891-1958. Lillywhite painted scenes from Alaska, the Bering Strait and Guatemala for dioramas at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. His main interest was the American West. Lillywhite had worked in the Empire molybdenum mine for a time, and after saving his money, moved to Denver. There, Lillywhite met the owner of The Art Nook, who offered Lillywhite his North Park homestead, which became Lillywhite’s studio and homestead.

Like North Park moose, Lillywhite found his time in North Park productive, creating 423 paintings in six years.

Walden is named for the area’s first postmaster, Marcus Walden, in what was then Larimer County. Ranchers helped establish Walden as a commercial hub in 1890. Jackson County was formed out of a portion of Larimer in 1909. The next year, North Park had 165 farms with 31,000 cattle and 2,000 sheep.

Jackson County farms now number 131, averaging 2,301 acres, mainly pastureland for cattle.

Oil jack pumps around the park, many on Bureau of Land Management Land and some on private land, produce little oil these days, and other wells are orphaned, their equipment idle. Some wells, though, still produce enough natural gas to fuel a new industry: block-chain computing for bitcoin.

Crusoe Energy Systems of Denver uses Jackson County natural gas which cannot be flared – Colorado law prohibits it – and cannot reach market. The gas supplies the high energy demands of crypto mining and cloud computing. A single bitcoin transaction consumes as much energy as an average American household does in 50 days. Crusoe installs a machine that makes 140 trillion calculations per second.

The Jackson County gas fuels generators that power the machines, all of it contained in a shed the size of a small

cabin, within feet of the wells. Eighteen bitcoin sheds stand in Jackson County, and they’re changing more than just the landscape. Flaring consumes 93 percent of a well’s methane; Crusoe’s generators consume 99.8 percent. Flaring in Jackson County has been cut 75 percent. Still a concern among some, though, is that the generators emit carbon dioxide.

The 18 cabins and reduced gas flaring is overall good news for Crowner. She wants her sky and her seasons to be like those she remembers.

Crowner was born on April 15, 1944, in a Laramie, Wyo., hospital – Walden didn’t have one then but does operate a medical center now – and rode her horse to a country school at age 7 and 8 along with six other children, all riding their horses. Working on a ranch, she milked cows morning and night. Her school-principal mother closed the country schools and consolidated the students in Walden.

Crowner was mayor of Walden from 1992 to 1995. Her first act was to restore natural gas to the town after Kansas-Ne-

braska Energy suspended service. Crowner organized a campaign for town support of a 46-mile gas pipeline from Walden to Laramie, and won. She asked for variances from endangered species restrictions along the pipeline’s path, and won. The pipeline was built, which is why Walden households can heat their homes with natural gas.

North Park is known for short summers, about three months. Its annual Never Summer Rodeo, held at the Jackson County Fair Grounds in Walden, is named for the fact that locals have seen snow every month of the year.

Melanie Leaverton with North Park Chamber of Commerce remembers one winter when weather stranded 150 students from the University of Missouri-Columbia, heading for a sky weekend at Steamboat Springs, in Walden.

“Everybody in town banded together, bringing crockpots of food,” Leaverton said. North Park High School opened the gym, and the kids slept on wrestling mats. “I had seven college guys at my house,

Moose can be found throughout the area around Walden. A bull moose takes a sip on a chilly summer morning in a high alpine valley near North Park.

stuck on wrestling mats, here for three days, with their stinky socks.”

It takes a community effort to help a lot of people all at once in crisis. That’s true in a weather disaster, and it’s true in solving a cold case.

Kayla Rizor works dispatch in the Jackson County Sheriff’s Office, which recently helped solve the identity of a 24-yearold man found dead along a U.S. Forest Service road in October 1987. Kayla remembers as a kid seeing a poster of the unidentified man in the Sheriff’s office.

With new technology available, such as DNA analysis, and new information, Kayla talked with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI) about reopening the case. The not-yet-unidentified man’s body was exhumed from the Walden Cemetery, where he had been buried. Jackson County provided a backhoe that got things started, and Kayla and others from the Sheriff’s Office and CBI used shovels to complete the job. They scanned the body with a metal detector and found a key clue to the man’s identity, provided by his family: a titanium rod in his right femur.

The family of Jerry Mikkelson of South Dakota finally had some answers. The family, Jackson County and Kayla had waited decades for those answers.

Most of the calls Kayla receives involve ranch accidents, usually someone who’s been bucked off a horse. Her uncle Jim and aunt Becky are Jackson County’s only two paramedics.

Traffic accidents with wildlife are common. A moose would sun on the road leading north from Walden and was hit by vehicles multiple times, surviving impact time and again. He met his end after destroying a young man’s new car and charging at the driver. Kayla’s dad was the responding deputy, and found the moose severely injured.

Of course, Kayla has her own moose story.

“It was late spring, I was running late for work, and a moose was outside my house, on my front step, eating my tree,” Kayla said. “I waited till he left, and it made me 15-20 minutes late.” That’s the most reasonable excuse for tardiness in Colorado.

MICHAEL deLEÓN

Whether it be snow, rainfall or lighting, spring storms stir the hearts and sharpen the vision of Colorado poets.

Joe Mehesy, Dolores

Looking for signs of soft green grass

For clear blue skies and warming breeze

But here instead we see the seasons clash

Biting winds and icy sleet still pierce our skin

Thunder sounds from threatening clouds

Forecasts change by the hour

As Nature shows her fickleness

Suddenly bright sun beckons again

Go out with coat, boots or sandals?

A thaw brings slush, mud and potholes to dodge

Then a short hike brings sweat to our brow

Hope renews for continued warmth and constant days

But don’t look for spring in Colorado Winter fights summer until summer wins

Robert Basinger, Rifle

A rainy walk down a muddy road

The air is moist and fresh

The mud is deep and earthy rich

Springtime is the best.

All the trees and shrubs are sporting sprouts

Soon we will arrive

As I give thanks for answered prayers

The future will survive.

My skin is wet

My mood is soft

As I traipse along

I can’t help but smile

And crane my neck

The rain is getting strong.

These are scribbled notes

From a poet’s heart

The page is streaked and wet

But it’s my job to write things down,

So we all don’t forget.

Vaughn Neeld, Cañon City

Pushing aside the heavy barn doors, we stepped within the cool darkness. Hundreds of little trees stood in rows, their roots wrapped in porous burlap.

We planted the orchards that springapple trees, pear trees, peach, cherry, and plum - anticipating an abundance of fruit in only a few years’ time.

We loaded the trees onto the back of the truck.

In the field, we sat on the sideboards, pushing the trees onto the conveyor, which dropped them into moist, brown holes.

We walked behind the truck, ripping off the burlap, filling in dirt around the trees, feeding fruit trees into the ground, then waited, and prayed, for rain.

Every afternoon clouds built, boiled into thunderheads, but the sky would clear, so we hauled water to the trees, praying, “Don’t let our trees die, Lord, please.”

Every night, back at the house, we sat resigned, but finally, it happened. The rain came, filled the ditches, the creek, the pond - too much rain.

The fields were seas of mud, the little trees took a beating, looking half drowned, so we prayed, “Okay, Lord, you can stop now. Please, stop now.”

And during the night, the rain stopped; the fields dried out, and when we inspected the trees, they were standing firm, spouting new leaves, thriving - after the rain.

Ann Thacker, Lakewood

Batons bend Aspen-like pointing prisms of serrated light down icicles dripping, discord, treble in the night.

Ping, ting, ding-a-ling ... droplets glimmer, glissading melody on the forest floor rhythmic rivulets changing pitch concerto of a rolling river.

Rapids, tonal in the torrent, toss trilling piccolos aside. Tympanic interludes, crescendo, cascades crest and suddenly subside. Finale!

Harmony in a pond.

Sandy Morgan, Colorado Springs

In the groomed and plotted beds of tulips in the park,

one scarlet beauty couldn’t wait - she opened full-throated as an opera singer in early warm sun.

I admire her abandon, even though her star will fade before the show begins.

Dan Guenther, Morrison

Late in the afternoon a lightning strike spooked our buckskin filly, a steep pyramid of a thunderhead arriving from out along the Kansas line, a dense, vertical wall climbing to heights beyond the reach of eagles:

Out here on the tumultuous high plains the personal bonds we make are strong, and those of us who still buck hay for a living do so by a creed of hard work, keeping our promises with a handshake when the spring storms burst upon us, turning the dusty void into a sea of flowering sage.

Nancy Cummins Bierman, Littleton

snow child plants fat sloppy kisses on my nose my dog turns white shakes herself black turns white again tree trunks bundle up in wooly jackets my coat is coated the air aswirl with silky sparkles a snow-globe big enough to stand in

SEND YOUR POEMS on the theme “Bounty” for the September/October issue, deadline July 1, and “Dark Skies” for the November/December issue, deadline Sept. 1. Send to poetry@coloradolifemag.com or to mailing address at front of the magazine.

Eye-appealing desserts liven up dinnertime

Recipes and photographs by DANELLE McCOLLUM

NO MATTER WHAT main dish takes center place on the dinner table, expect plenty of side glances at the pie table with one of these recipes. Chances are your pie will be so memorable that you’ll be asked to make it again next month. The focus of these recipes is on the filling. For the crust, you can either use uncooked refrigerated pie crusts or build up on your own favorite crust recipe.

Fresh cranberries, dark chocolate and pecans join forces in this decadent pie. The pie looks beautiful and colorful, and the balance of sweet and tart is just right. This recipe can be made several days in advance, which comes in handy when preparing for big dinners. Filling the crust with pie weights or uncooked rice while baking is necessary to prevent the crust from sliding into the middle.

Transfer uncooked pie crust to 9-inch pie plate. Trim pastry about 1/2-inch beyond rim of plate and flute edge. Refrigerate 30 minutes. Prick pie crust all over with fork, then line with double thickness of foil or parchment paper. Fill with pie weights, dried beans or uncooked rice. Bake at 450° for 10-15 minutes, or until edges are light golden brown. Remove crust to wire rack and remove foil and weights. Reduce oven temperature to 350°.

In large bowl, beat eggs, sugar and melted butter until well blended. Whisk in flour until smooth. Stir in vanilla extract. Stir in pecans, cranberries and chocolate chips. Pour into crust. Bake at 350° for 30-35 minutes or until top is bubbly and crust is golden brown. Cool to room temperature before serving. Refrigerate leftovers.

1 uncooked 9-inch pie crust

3 eggs

3/4 cup sugar

1/2 cup butter, melted

3 Tbsp flour

2 tsp vanilla extract

1 cup chopped pecans

1 ½ cups fresh cranberries

1 ¼ cups semisweet chocolate chips

Ser ves 8

This recipe takes a few shortcuts to create a “tastes like homemade” apple pie in almost no time at all. Rather than a traditional pie tin, the pie is cooked and served in a castiron skillet. The pie can be served in slices like normal, but it’s also fun to scoop a bunch of ice cream on top and let everyone dig in with a spoon right from the skillet.

Melt butter in 9-inch cast iron skillet over medium heat. Remove 1 Tbsp of butter for top crust. Add brown sugar and stir well. Continue cooking for a few minutes until mixture just begins to bubble and sugar is dissolved.

Remove from heat and lay one pie crust in skillet, over melted butter and brown sugar mixture. Spread apple pie filling evenly over crust. In small bowl, toss together white sugar and cinnamon. Sprinkle 1 Tbsp of cinnamon sugar over apple pie filling. Top filling with second pie crust, folding the edges over to form a border.

Brush top crust with reserved 1 Tbsp butter. Sprinkle with additional cinnamon sugar, as desired. Cut vents in center of pie. Bake for at 400° for 30 minutes or until golden brown. Serve warm with vanilla ice cream.

1/2 cup butter (1 stick)

1 cup brown sugar

2 refrigerated 9-inch pie crusts

1 21 oz can apple pie filling

2 Tbsp white sugar

1 tsp cinnamon

Vanilla ice cream for topping

Ser ves 8

A rich, brownie-like filling is topped with a traditional German chocolate frosting in a pie loaded with pecans and coconut. The frosting is so good, you’ll be tempted to eat it straight – but the recipe makes a generous amount, so feel free to sample a few bites.

In medium bowl, combine melted butter, sugar, vanilla and eggs until well blended. Stir in flour and cocoa until smooth. Stir in chocolate chips and pecans. Pour mixture into prepared pie crust and spread evenly. Bake at 350° for 25-30 minutes or until center no longer jiggles and inserted toothpick comes out clean. Cool completely.

Meanwhile, make frosting by stirring together condensed milk, egg yolks and butter in medium saucepan. Cook over medium-low heat, whisking constantly until thick and bubbly. Remove from heat and stir in vanilla extract, coconut, pecans and pinch of salt. Cool completely before spreading over pie. If desired serve pie topped with chocolate fudge sauce and/or pecan halves for garnish.

Pie

1 uncooked 9-inch pie crust

1/2 cup butter (1 stick), melted

1 cup sugar

1 tsp vanilla extract

2 eggs

3/4 cup flour

1/3 cup cocoa

1/2 cup semi-sweet chocolate chips

1/2 cup chopped pecans

Frosting

1 14 oz can sweetened condensed milk

3 egg yolks, lightly beaten

1/2 cup butter (1 stick)

1 tsp vanilla extract

1 ½ cups sweetened flaked coconut

3/4 cup chopped pecans

Pinch of salt

Ser ves 8

story by TOM HESS

photographs by STEPHEN MARTIN

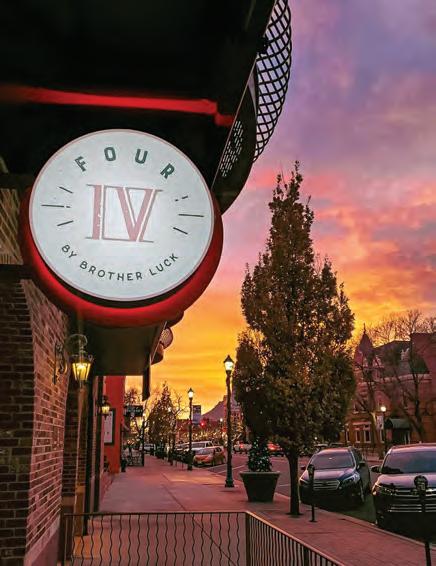

Colorado Springs chef Brother Luck is writing the roadmap to elevated regional cuisine, and to finding happiness.

Brother Marcellus Hayward Luck IV is the fourth Brother Luck in his family. That helps explain why he counts four as his lucky number, the number he has built his most enduring restaurant around, Four by Brother Luck in Colorado Springs.

On a busy Thursday night, Luck guides a guest through Four’s many fours: his four-course menu, built on four types of local suppliers, through the four seasons of the year.

Luck has settled with his wife, Tina, into the seasonal rhythms of downtown Colorado Springs, with its grid of streets with names derived from four foreign languages: Spanish (Vermijo, meaning “reddish”); French (Cache la Poudre (meaning, “Stash the (gun)powder”); Ute (Sawatch, meaning “blue-earth spring”), and Mexican (“Tejon” meaning an animal in the raccoon family).

321 N. Tejon Street is now Luck’s address for providing a roadmap to the culinary diversity of southwest Colorado. He began his restaurant career cooking in the grimy kitchen of a Colorado Springs punk rock bar until a brawl among customers ended in lawsuits. He moved to the peace and security of a standalone restaurant but admits he had no business plan, no concept he could describe. Then, on a business trip to Japan, the concept for a new restaurant occurred to him: Four.

Luck carefully curates every dish, like seared scallop with piquillo puree, fennel fronds and foie gras foam.

Four’s menu changes with the seasons, but the creativity continues. Sous Chef Geri Woesner and Chef Brother Luck create dishes like duck green chili and jalapeño poppers.

Four by Brother Luck, a block north of downtown Colorado Springs’ Acacia Park, is a fine-dining experience – no brawls, no busted bar chairs – built on the number four: four menus a year reflecting the region’s four distinct seasons; four culinary sources (farmers, fishers, hunters and gatherers); and, of course, the fact that Luck the Fourth is the fourth male to bear that name Brother Luck.

Inside Four, Luck uses stylized petroglyphs, an ancient form of Indigenous art, to portray in frosted glass the four seasons and his four culinary sources – crossed arrows for hunting, a tractor for agriculture, a plant for gathering, and a fish. The menu is, you guessed it, four courses.

Luck attended to every detail of the restaurant’s interior, choosing the opposite of the space’s white walls that reminded him of a cafeteria. “We had to grow into this space, we had to learn this space,”

Luck said. The interior is dark and quiet. The tablecloths are black. The earthenware crafted by Mark Wong of Manitou Springs is black and red and both large and small and heavy. Acoustic tiles, rugs and canvases absorb sound.

On his Thursday night restaurant tour, Luck orders for a guest all four items in the first course.

First up is blue cornbread, a native American dish with a Brother Luck twist and the most Colorado item on the menu. There’s convincing evidence that the native American society known as the Hopi grew blue corn before European settlers arrived in the Four Corners region. Luck combines blue cornbread, warm and crisp outside, smooth inside, with Wojapi, a native American berry sauce, adding the kick of Pueblo chile, the sweetness of Black Forest honey and the aroma and mouthfeel of crema. Luck has prepared

the dish for other chefs around the nation, to their delight; they’d never had anything like it in Chicago or San Francisco.

Another first-course meal, the jalapeno poppers with the cream cheese center, dissolve on the tongue, and kicks it too, with jalapeno syrup and a jalapeno slice on top. By comparison, the blood orange salad is light and fruity, a mix of red apple, gorgonzola, walnut and blood orange segments, dripping with spiced maple orange vinaigrette. Finally, the lamb albondigas, with a fried quail egg, poblano coulis, cheese aioli spread and crostini, is an addition to the menu from Four’s female Chef de Cuisine, Ashley Brown.

Courses two and three soon follow, featuring another southwest-favored dish: duck green chile. The pork belly with apricot jam, peanut butter mole and crispy tostone (twice-fried green plantain) is Luck’s take on PB&J. Salmon comes with a salsa macha glaze alongside caramelized mushroom and watercress salad. Achiote chicken breast offers Luck the chance to give a history lesson – achiote being the annatto seed (Bixa orellana), with uses beyond spicing his chicken.

“Achiote was used for war paint for na-

tive American culture,” he said. “It was used to stain anything originating west of the Mississippi.”

The fourth course – four dessert choices – proves difficult to choose from, after three satisfying courses. The flourless chocolate and cherry cake, with black cherries, rosemary and white chocolate snow, is rich complement to the jalapeno and green chile that came before. Luck said he likes doing research, “digging” for recipes, ingredients, and history that will add excitement to his dishes.

A few years ago he found a survivalist who trained at the Air Force Academy. The man took Luck and his staff on a gathering trip to show them what ingredients they can find locally around Colorado Springs. They came back with wild asparagus, wild raspberries, wild strawberries from near Rampart and Fountain Creek. He introduced them to wild edible weeds, which Luck now uses in his dishes.

The menu includes vegetarian courses like tofu sofritas with frisée, avocado crema, yucca root, turmeric dust and fresno jam.

Four also includes an extensive wine and drink menu including the Bartenders R&D, a daily rotating concoction made by bartenders such as Kyle McNerney.

Luck keeps his eyes open for local farmers. For a time, he had a local supplier of pork, Mary Miller of Triple M Bar Ranch in Manzanola. “She would pull in the back of my restaurant, in a Subaru with a lamb in the back,” Luck said. Miller has since retired, so Luck keeps digging. He’s had to go beyond Colorado for some items. He ships duck from an Amish farm in Michigan and salmon from the Faro Islands.

Luck likes to build relationships with local gardeners. “I had the coolest deal worked out, two little old ladies, who would grow on plots near 8th street. They would bring me beautiful baskets of all kinds of greens, garlic, herbs and berries. And squash.”

Luck’s longtime mentor, Steve Kander, keeps a garden at his Colorado Springs home. He often stops by Zander’s house to pick squash blossoms in the early morning, and to check-in with an old friend.

The two chefs met when Zander moved to Colorado

Springs and joined the staff of Cheyenne Mountain Resort. Zander has walked with Luck through 17 years of emotional highs and lows. Luck has struggled with depression, but tries to use his life to bolster others.

His journey with depression began when Luck lost his father at age 10 and his mother at age 16. Kitchens became his refuge, his way out of poverty, but not his salvation. One of his lowest lows came on national television.

Luck appeared on Bravo network’s Top Chef. He did not win and got cut, then had a second chance to come back, then got cut again. “I walked away feeling like I wasn’t good enough,” he said. Luck hit bottom emotionally, alarming his wife, Zander and other friends. Luck admits he still wrestles with the pain of that public rejection.

At the same time, Luck vows to smile more. He attends a nourishing church. He’s lost 50 pounds. He hasn’t had alcohol for more than six months. Tina surprised him with a renewal of their vows on a Las Vegas weekend in January. There are four chambers in the human heart, and Luck’s heart is full.

Fans of the 1993 movie Free Willy know that the film starred a captive Atlantic Ocean male orca named Keiko, who was eventually re-introduced into the wild. The landlocked Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS) hosts on its third floor a temporary exhibit, Orcas: Our Shared Future, that includes a poster of the movie, other memorabilia and whale biographies, plus life-size replicas of three orcas from the so-called J pod orcas – residents of the southern Pacific Northwest. Southern Orcas are critically endangered.

The orca replicas are modeled from three J pod orcas: Ruffles, a 59-year-old male with a wavy dorsal fin, who was last

seen in 2010 and presumed deceased; Slick, a 51-year-old female who’s considering the oldest whale in the J pod; and Slick’s last calf, Scarlet, named for the rake marks on her body from the teeth of another of another whale. Scarlet was last seen in 2018.

Slick can still be seen in the waters of the Pacific Northwest, and all over social media. Ruffles and Scarlet can be seen alongside Slick at DMNS, in a setting that gives visitors a sense of being underwater.

Also on display are artifacts and artwork – wood and stone carvings, textiles, watercolors – that indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest produced in their reverence for the orca.

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE, THROUGH SEPT. 2

The zoo offers Gorilla Trek, a virtual reality experience that immerses the viewer in a family of gorillas.

2300 Steele St., (720) 337-1400

The restaurant has a 500-piece display of game. Buffalo is on the menu, too.

1000 Osage St., (303) 534-9505

Of the 46 hand-carved animals in the carousel, the 16 animals on the outside row of this 1905 carousel are the largest on the ride, and include a giraffe, a zebra, a camel, and a lion. Visitors favor the nicknamed Hippocampus, a horse with a fish tail, and the armored horse. Each animal’s details are faithfully recreated, including teeth, tongues and hooves. The antlers on the deer and horsehair tails on many of the horses are authentic. The animals’ glass eyes match the temperament of their animals. Intricate flowers adorn many of the inside row animals. Saddle trappings are reminiscent of those used on cavalry mounts in the 18th Century Napoleonic Wars.

Elitch Gardens of Denver, when it was located at 38th Avenue and Tennyson Street, ordered the carousel from a Philadelphia manufacturer. Elitch Gardens sold the carousel to Kit Carson County in 1928 for $1,200, including shipping. The carousel and its Wurlitzer organ fell into disrepair; following a 25-year restoration effort, the carousel opened to the public. 815 N. 15 St., (719) 346-7666

MAY 25-SEPT. 2, BURLINGTON

Old Town Museum

Can-can dancers, gun fights, and a dinner theater bring life to a sprawling display of historic buildings, vehicles, machinery and collections. 420 S. 14th St., (800) 288-1334

Parmer Park

Shaded picnic areas and a playground, including a rocket, offer a welcome break. Next to a pool. 1858 Ben St.

The Dish Room Wagyu/Angus beef raised near Telluride and Berkshire pork raised by J&J Farms near Armel and Idalia lead the menu. Burgers include the John Wayne. Sandwiches include the Chuck Norris. 218 S. Lincoln St., (719) 346-8790

IRON HORSE BICYCLE CLASSIC

MAY 24-26, DURANGO

Bikers race the Durango Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad steam locomotive along the Million Dollar Highway, U.S. Route 550, pedaling over two 10,000-high mountain passes from Durango to Silverton, a 50-mile ride with 5,700 feet of elevation gain. The race is one leg of the McDonald’s Citizen Tour. registration@ ironhorsebicycleclassic.com

NATIONAL DONUT DAY ON PIKES PEAK

JUNE 7, PIKES PEAK

The first 250 guests – whether they hiked, cycled, drove or rode the Cog Railway to the top, at 14,115 feet - will be greeted with a free donut upon entry. Choose from plain, cinnamon sugar or Donut of the Day (such as frosting and sprinkles).

(719) 385-7325

HOT SULPHUR DAYS

JUNE 7-9, HOT SULPHUR SPRINGS

Friday begins with a 9:45 a.m. botany walk along Parshall Divide, with a kids’ carnival, pie contest and sale, and a concert to complete a busy first day. Saturday begins with an 8 a.m. flag ceremony conducted by the Boy Scouts, followed by a pancake breakfast served by firefighters, then a parade from Pioneer Park to Town Park, and then a BBQ lunch by Amber Flames – ribs, pulled pork, chicken. Sunday is a 5K run from Mini Merc to the cemetery and back. Calvary Church will conduct worship services at Town Park, followed by a friendly softball game. info@hotsulphurdays.com

Upcoming Events in Monte Vista, Colorado

Ski-Hi Stampede, July 11 –14

Faith Hinkley Memorial Fundraiser, July 27

SoCo Suds & Sounds, Aug. 17

Potato Festival, Sept. 7

Come stroll through town and experience The Swoop of the Cranes

These beautiful works of art are hand painted by local artisans and will be on display until September!

Campground offers comfort while exploring Canyons of the Ancients

Years ago, my buddy and I decided to explore Canyons of the Ancients National Monument in southwestern Colorado. There are no public campgrounds within the monument, so we decided to just load wives and camping gear into our 4x4 trucks and find a suitable spot off a back road to pitch our tents, leaving our trailer behind.

Following an abandoned roadway into the backcountry, we found a flat, bare ground site ideal for setting up camp. After grilling steaks, we spent the evening sipping adult beverages around a campfire, barely noticing that the star-studded sky was being slowly cloaked by oncoming clouds.

Sometime before dawn, snow, graupel and hail fell, turning the flat, bare ground into a boot-clinging quagmire of mud. In unison, our wives declared the camping trip over. We packed up, and with muck flying from wheel wells, we fishtailed up the mud-mired roadway in four-wheel low. Next time we visit Canyons of the Ancients, my wife declared, we’ll bring the trailer and stay in a formal campground. While there are several commercial RV park options nearby, we prefer overnighting in public campgrounds where rigs are not sardined together like cars in a Walmart parking lot. We found that the McPhee Campground, located above the reservoir of the same name, provides an

McPhee Campground is 8.5 miles northwest of Dolores off Colorado Highway 184.

The campground offers 71 sites in two loops; 50 of them may be reserved by calling (877) 444-6777, or visiting recreation.gov. A few offer electric hookups. Open from May 3 to Sept. 29, McPhee offers potable water spigots, toilets and trash dumpsters. Fees range from $36 for an electric site to $26 for a tent-only site.

excellent, mud-free alternative for camping near the Ancients.

Managed by the Forest Service, McPhee offers 71 well-spaced sites atop a piñonand juniper-covered mesa, 500 feet above what is now Colorado’s second largest res ervoir. Built in the 1980s, McPhee would store much needed municipal and agricultural water for the area. Unfortunately, the impounded water would submerge a wealth of Ancestral Puebloan sites in the Dolores River Canyon. Archeologists rushed in, surveying more than 1,600 sites and collecting more than 1.5 million artifacts.

Those treasures from the past are housed at the Canyons of the Ancients Visitor Center and Museum. Located a quick 5.5-mile drive from the campground, it serves as a good first stop for those of us out here to explore the 174,000acre monument. Two archeological sites, Dominguez and Escalante Pueblos, lie on the Visitor Center Grounds, whetting our appetite to see more.

Maps available at the museum can be used to locate three more easy-to-access Ancestral Puebloan sites. Largest and most impressive is Lowry Pueblo, a 1,000-yearold, multi-room ruin lying 24.5 miles northwest of the campground. A steel roof covers one of the site’s kivas where painted plaster sporting geometric patterns once covered the walls.

Painted Hand Pueblo, the tower ruin that graces the monument’s handouts, lies 32 miles from the campground. The name comes from a nearby boulder where Puebloan artists spray-painted the outline of hands. Getting to the ruins once required navigating a high-clearance road not suitable for grandma’s Buick. A new, improved roadway now leads to the site with expanded parking, picnic tables and a grandma-approved bathroom awaiting visitors.

Nineteen miles from the campground lies Sand Canyon Pueblo. Occupied in the 1200s, this Ancestral Puebloan village held about 420 rooms, 100 kivas and 14

towers. After excavating the ruins, archeologists backfilled the site to protect standing walls and to preserve what’s left for future archaeologists. A half-dozen interpretative signs explain what lies beneath the rubble.

Nearby lies the upper end of the 6.5-mile-long Sand Canyon Trail, which leads down a broad canyon peppered with cliff dwellings and granaries. From here, it’s a 1,400-foot, out-and-back descent with a half-mile section of trail plunging down a 700-foot-tall cliff in a sinuous series of switchbacks. While I’ve hiked the trail from the top down, I prefer the bottoms-up approach, beginning at its lower trailhead off Road G west of Cortez.

These are but a few of the sites in what archeologists claim is the highest density of Ancestral Puebloan sites in the country. To discover others, we’ll drive down back roads like the one beside which we once camped. Parking above a promising draw, ravine or canyon, we’ll set off on foot and see what we might find.

At day’s end, we can retreat to our campsite at McPhee, grill up some steaks and spend the evening sipping adult beverages around a campfire with nary a worry about what might happen should the star-studded sky be cloaked by oncoming clouds.

Questions on pages 12-13

1 Rocky Mountain National Park

2 Zip line; ropes course

3 Hot springs

4 Yampa

5 Trout

6 b. Shoulder season

7 b. The sound of footsteps in mud can scare away wildlife

8 c. Medano Creek

9 a. Arapahoe Basin

10 c. Stand-up paddleboarding

11 False (Grand Junction doesn’t really experience mud season)

12 True

13 True

14 False (Mud is name of character; movie takes place in Mississippi)

15 False (it is on Labor Day weekend and is unrelated to mud season)

Trivia Photographs

Page 12 (top) Medano Creek in Great Sand

Dunes National Park

Page 12 (bottom) Whitewater kayaking

Page 13 Muddy trails

Bird watchers are finding their perfect playground on the Pioneering Plains of northeast Colorado. The natural backdrop of Plains areas in Sterling and Logan County invites birders to journey off the beaten track in search of new encounters with a variety of species in an unspoiled environment.

Did you know there are more than 300 species of birds in this area?

story and photographs by JOSHUA HARDIN

Camera-wielding travelers and casual tourists alike seek out the bright blooms of summer but may overlook what spring reveals. Here are a few of the species that warrant a trip in spring.

Named for the Easter holiday, pasqueflowers, also known as prairie crocus, are some of the first surfacing buds of the season. They can be found in a variety of places statewide, amongst shady evergreen stands padded by fallen needles or in sunnier hillsides and open fields. Though the plants usually don’t grow taller than about three inches, their hairy, triangular purple-and-white petals and yellow stamens are unmistakable.

Hearty Indian paintbrush begins to appear in late March and remains into October in some locations. The prolific plant is found in all Colorado regions, from the canyon rims on the Western Slope to the pastures of the Eastern Plains. Its fiery red flares, dabbled with magenta pigments, appear in thick bushy arrangements on the muddy edges of melting snowbanks, and solitary, palm-tree like twigs in dry desert soils.

The Calypso orchid, also called the Fairy Slipper, is shy. Named for a Greek word meaning concealment, the flower favors the cool, moist soils of the montane forest floor including those in Rocky Mountain National Park and can be difficult to spot. When keen-eyed searchers do find the elusive flowers, they appear like firework sparklers. The plant’s bright fuchsia pink flowers seem to explode from straight, upright stems into a starry plume on top of a shoe-shaped bud.

One of my personal favorite flowers is wild iris. Similar in appearance to the commercially available varieties of iris seen in backyards, the stalks of Colorado’s

Some of the most recognizable pollinators are hummingbirds. They journey from Central America to the Colorado mountains in late spring.

wild versions rise about 1-2 feet and are capped by spreading showy displays of blue-purple, gold and white stripes. Iris appears as early as April and usually lasts through June, favoring marshy wetland environments on the edges of ponds or lakes. Hotspots include the high mountain valleys of South Park near the reservoir of Eleven Mile State Park, and the banks of the Rio Grande River in the San Luis Valley.

Just before summer starts, Rocky Mountain penstemon pushes its bushy groupings of multi-spired, tubularly lobed flowers upward into the state’s higher elevations. The purple-hued plants tower between one to three feet and can tolerate heavy, rocky ground and snowmelt. Penstemon is equally at home in the sagebrush sea of the northwestern counties or the coniferous foothill communities of the Front Range.

Such diverse flora require pollinators that assist the plants’ reproductive cycle.

Some pollinators, including many bees, seek out pollen. Others, like many butterflies, beetles, birds and bats, transport pollen that sticks to their bodies while they’re doing other things. A great example of unintentional pollinators are ladybugs, small beetles that not only assist with successful pollination, they also feast on destructive aphids. A ladybug can eat up to 5,000 aphids in its lifetime.

Some of the most recognizable pollinators are hummingbirds. They journey from Central America to the Colorado mountains in late spring. The birds’ long beaks are specially adapted to extract nectar from the protruding stamens of specific plants. Broad-tailed hummingbirds have scarlet necks and green bodies with resplendently fanned tailfeathers.

Broad-tailed hummingbirds are often followed by rufous hummingbirds, a spunky cinnamon-colored species. The rufous stage dazzling displays of territorial aerial acrobatics around feeding sources. The dance for dominance entertains photographers willing to work with fast shutter speeds in flower-filled meadows.

Visitors should refrain from picking Rocky Mountain penstemon, coneflower, bee balm, milkweed or other native drought-resistant species for their own backyards. Such actions may be illegal at some sites. Instead, take a photograph and bring it to a local greenhouse.

Spring is fleeting in Colorado, yet the memory of early-season wildflowers lives on in photographs, and perhaps in transformed backyards across Colorado.

JOSH SHOT this photo near Eleven Mile State Park with a Nikon D300 and Nikon 70-300 mm lens at 270mm, exposed at f/5.3, 1/200, ISO 200.