JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

As the cold freeze of winter sets in across mountains and plains, Colorado’s natural beauty takes on a new kind of grandeur when covered in blankets of snow and ice.

By Matt Masich

30

During World War II, elite winter warriors learned to ski and scale mountains at Camp Hale in the Colorado Rockies, then put their skills to the test fighting Nazis in Italy.

By Matt Masich

46

The beloved getaway of presidents, celebrities and regular folks alike, this historic Colorado Springs resort operates like a city within a city, complete with its own fire department.

By Tom Hess

In the San Juan Mountains near Telluride, a hardy band of mountain dwellers make their home in Ophir, where an avalanche chute runs right through the middle of town.

Story by Caroline Araiza

Photos by Barton Glasser

The bones of two dinosaurs are displayed as though fighting each other at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science – fossils that were separately unearthed by Colorado schoolchildren.

By Tom Hess

Hot Sulphur Springs is...

• nestled in the Rocky Mountains waiting to be explored

• filled with Pioneer, Railroad & Native American history

• the county seat & oldest town in the ❤ of Grand County

• Gold Medal fishing on the Colorado River

• named for the historic hot springs

ON THE COVER

Aspen Highlands is a resort whose heritage ties back to the 10th Mountain Division. Story begins on page 30.

PHOTOGRAPH BY DAN LEETH

Dinosaur National Monument, p 60

Rocky Mountain National Park, p 22, 25, 26

Golden, p 63

Genesee, p 27

Vail, p 30

Rifle, p 24

Aspen, p 16, 20

Ouray, p 27

Ophir, p 52

Telluride, p 70

Dillon, p 25

Leadville, p 30

Arvada, p 13

Denver, p 12, 60, 62

Manitou Springs, p 64

Colorado Springs, p 46

Cañon City, p 60

Great Sand Dunes National Park, p 28

Trinidad, p 14

Sluice Box

Artist finds a fresh new way to paint familiar mountains, waiters sing for dinner guests in Trinidad, furry friends help troubled returning veterans and the “King of the Dump” creates a novel way to coat aspen leaves in gold.

Colorado Trivia

Test your knowledge of Colorado eats and eateries, from krautburgers to sloppers at Gray’s Coors Tavern.

40 Poetr y

Poets from across the state celebrate the people and places of Colorado in all of their colorful, multifaceted glory.

42 Kitchens

Appetizers take center stage with these tasty recipes.

62 Go. See. Do.

A statewide roundup of the best local festivals, events and daytrip ideas gives a plethora of opportunities for fun wintertime adventures in all parts of the state.

70 Top Take

In our editors’ choice photo, remarkable clouds ripple above the snow-covered slopes of Wilson Peak.

ONE OF THE most rewarding experiences as editor of Colorado Life is when a subscriber tells me they read the magazine from cover to cover. It is gratifying to know that every bit of work we put into each page of the magazine is being appreciated.

Still, I sometimes wonder: Do folks who say they read the magazine “from cover to cover” literally start at the front cover and read each page in order until they’ve reached the back cover? If so, that’s different from how I read a magazine. Rather than cover to cover, I read from short to long – starting with the small department stories as an appetizer and saving the features for the main course.

When I open a new issue, I first flip through to look at the pictures and get an idea of what the stories are about. After a quick glance at my Editor’s Letter to make sure I didn’t let any typos slip in, I take a look at the Colorado Trivia section, followed by the shortand-sweet stories collected in our Sluice Box department. Next, I might see what events are in the Go. See. Do. section or check out the recipes in Colorado Kitchens. Only then, with my appetite for reading properly whetted, do I tackle the big features.

Of course, there’s no right or wrong way to read Colorado Life. Several readers have told me they like to start reading each issue with the Colorado Poetry department. I love the idea of kicking off the reading experience with poetic celebrations of our state, and it makes me proud to know Colorado Life is one of few magazines to publish poetry in the first place.

The poetry never fails to give me a new way to look at familiar places. In this issue’s poem “Alamosa,” Keith Grogan writes about the “sour-cream-dollop-topped Sangre de Cristos/looking down on dunes and fields of potatoes.”

My favorite part about the poems is that they are all submitted by readers themselves, giving our audience a voice in the magazine. The most direct voice our audience has is in the Mailbox section, which gives readers the chance to communicate with our staff and their fellow readers to give feedback on the magazine or share their own Colorado stories that our stories have evoked. The Mailbox is another great place to start reading.

Whether you read Colorado Life from cover to cover, skip around like I do or start with the poetry, I invite you to do something once you’ve finished reading this issue. Would you send me a quick note with a thought or memory inspired by one of the issue’s stories? Or perhaps you could tell me what order you read the magazine.

Matt Masich Editor editor@coloradolifemag.com

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Volume 12, Number 1

Publisher & Executive Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Editor

Matt Masich

Photo Editor

Joshua Hardin

Design

Madison Dupre, Open Look Creative Team

Advertising Sales

Marilyn Koponen

Subscriptions

Lea Kayton, Katie Evans, Janice Sudbeck

Colorado Life Magazine PO Box 270130 Fort Collins, CO 80527 970-480-0148

ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $25 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $44. Please call, visit ColoradoLifeMag.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and corporate rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, visiting ColoradoLifeMag.com or emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2023 by Flagship Publishing Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

Free with Museum Admission Gratis con admisión al museo

NOV. 18 − APR. 9, 2023

18 de Noviembre al 9 de Abril de 2023

Here’s to another great year

As a new year begins, I enjoy looking back on the past issues of Colorado Life from 2022. The magazine never fails to entertain, educate and enlighten readers about so many wonderful places and events going on in Colorado. We sure do live in a beautiful and breathtaking state, and the photography with the featured articles captures it very well. I appreciate the balance of content and ads and like to save back issues of Colorado Life as a reference for things to Go. See. Do. Keep up the great work. I look forward to what will be in 2023!

Deb Adams Westcliffe

Snowmobile adventures

We look forward to enjoying each issue of Colorado Life. The stories are diverse and interesting with the stunning photography enhancing the stories. We especially enjoyed “Up Wolf Creek Pass on a Snowmobile,” the story of Forest and Jaclyn Bramwell (November/December 2022). Their lives, at first, seem idyllic, riding around on snowmobiles in that beautiful area around Wolf Creek Pass. As we learn in the rest of the story, it hasn’t been easy for them working long hours seven days a week. They have persevered and now have a successful business showing people around their territory and creating experiences people will remember the rest of their lives.

Phil Watkins Littleton

Thank you to Matt Masich and local Breck photographer Joe Kusomoto for bringing the story of our resort and incredible employees to life in your article “Behind the Scenes at Breck” (November/December 2022). There is so much work that takes place in the background that most people never get to see or hear about but is integral to our resort operations. It was so cool to shine a light on all that happens behind the scenes and off hours through this story, and to highlight some of our dedicated and passionate employees.

Our employees truly are the heart of our resort and the Breck community, and they are the ones that bring the resort to

life, day-in and day-out. Next time you’re skiing or riding at Breck, or any resort, give a high five or a “thank you” to the employees that are out there making it happen. Thank you for sharing this story!

Jody Churich VP & COO at Breckenridge Ski Resort

Ski

I enjoy every issue of Colorado Life, and I especially enjoyed the November/December 2022 issue. I had no idea it would require so many people to keep a ski resort open and running. The article entitled “Behind the Scenes at Breck” helped me understand and appreciate the ski industry. I also was particularly interested in the wildlife pilots (“Four Pilots, Four Planes, One State”). Flying in those small planes would give me a special thrill. What a job!

When sharing my love for this magazine with a friend, she took one of the subscription cards and said it would be a perfect Christmas gift for her son-in-law who had just moved to Colorado. I look forward to the next issue of Colorado Life.

June Tate Loveland

The “Four Pilots, Four Planes, One State” article in the November/December 2022 issue sure brought back some memories. Way back in the early 1960s, one of the department pilots flew me over the sandhills near Wray to locate leks and count

greater prairie chickens when I was working on a graduate degree from CSU. Back in those days, they flew the de Havilland Beaver. I remember the intense eye-strain headache I got from trying to focus on the quad map and the prairie scene simultaneously. The pilot’s previous flying experience was rounding up wild horses in box canyon country, so I was entertained with many wild stories.

Keith Evans South Ogden, UT

I grew up in southeast Colorado, but, as is often the case in the place you grow up, you don’t “tour” it – you go elsewhere to vacation. I’ve lived in Ohio for 30-plus years, but guess where our family always wanted to vacation? Colorado!

In the November/December 2022 issue, I particularly enjoyed the story about Breckenridge Ski Resort, since it is a place we enjoyed skiing. I appreciate the broad scope of stories – from the quilting story (“Boulder Quilt Artist Captures Pet Personalities”) to the meadery (“Severance Couple Crafts ‘Nectar of the Gods’ ”) – and find lots of places we want to go when we visit our daughter, who now lives in Aurora. I’m amazed at all I missed while living in Colorado, but I appreciate the depth and breadth of your features. Not only are they entertaining but educational also. I look forward to each issue and your outstanding photography.

Lisa Sommerfeld Zuercher Apple Creek, Ohio

The article “Behind the Scenes at Breck” was a refreshingly different perspective on the resorts. It was good to hear from people working there and get more of an idea of what they do, especially in these days with an emphasis (hopefully) on better pay and benefits for those keeping the resorts running.

My favorite section in this issue of the magazine was Colorado Poetry. The first two lines from “September 1976” really touched me as I recalled my first road trip to Colorado and that long wait from crossing the Kansas-Colorado border before seeing the horizon “first morph into mountains.” And “Colorado Kid” – “He came to Colorado,/And fell in love.” I fall in love with Colorado all over again on every trip there.

Ed Leist Bel Air, Maryland

Thank you for another year of excellent poetry from Colorado poets. I have mentioned Colorado Life and Utah Life to several poets who have submitted excellent poems to both magazines. Local poets often don’t get the recognition their work deserves, so I am most grateful to you for affording us this wonderful outlet.

Vaughn Neeld Cañon City

Castle kudos

Thanks to you, we had a totally wonderful getaway in Colorado Springs. We had never heard of Glen Eyrie Castle, and it was terrific (“Glen Eyrie,” March/April 2022). The tour, tea, wildlife, hiking trails and lodging were terrific, and it was close to Garden of the Gods. We use your information and

appreciate learning about hidden gems in every single issue. Thanks for sharing more great tips about our home state.

Clair Beckmann Louisville

Grateful giftee

I received Colorado Life as a gift last Christmas. Love it! I am a native, raised in Idaho Springs and moved to the Denver area after high school in 1951, so I know Colorado. I read each issue cover to cover; I especially enjoy the trivia quiz (not always too swift at the answers), the Top Take photo and everything in between. I am giving two gift subscriptions this Christmas.

Marilyn Campen Centennial

Colorado dreamin’

As winter bears down on us here, we are so looking forward to returning to Colorado in the spring. While we love the snow and the terrific ski resort towns, we are absolutely enamored with the smaller, less “touristy” destinations. We always start off in Estes Park and stay at Romantic RiverSong Inn and venture down the Peak to Peak Highway, stopping along the way in many of the smaller towns. We love Nederland and actually stopped at an overlook to see the site of the famous recording studio Caribou Ranch.

After many visits off road to historic mining communities like Nevadaville, we end up in Alice to view the glacier. The views are incredible. After a night in Georgetown, we’re off to Breckenridge and a drive through Boreas Pass. Next day is Leadville and more mining towns like Alma and Fairplay. We love the great B&Bs we find along the way and love not overset text 433 words

SEND US YOUR LETTERS

We can’t wait to receive more correspondence from our readers! Send us your letters and emails by Feb. 1 to be published in the March/April 2023 issue. One lucky reader selected at random will receive a free 1-year subscription renewal. This issue’s winner is June Tate of Loveland. Email editor@coloradolifemag. com or write by mail to PO Box 270130, Fort Collins, CO 80527. Thanks for reading and subscribing!

Show it in 2023 with our NEW wall calendar

Filled with the gorgeous photography you love about the magazine –ready to hang in your home or office.

Order now for yourself and your family!

In the painting “Vail” by Topher Straus, the ski resort’s corduroy slopes come alive in bold colors. Using his personal photographs of Colorado as inspiration, the artist uses a “digital brush” to create his works, which are sublimated onto aluminum sheets.

by CORINNE JOY BROWN

Some scenes of Colorado’s grandeur appear so often in film and print that they are instantly recognizable. From the Maroon Bells, to Hanging Lake, to Garden of the Gods, the images have become iconic. That is why the art of Topher Straus is so profound, interpreting both the majestic and familiar in a way that allows the viewer to see what is known and loved with new eyes.

A former documentary filmmaker who studied under Robert Altman in Los Angeles, Straus also received a BFA in Fine Art in 1997. Painting the wilderness became an extension of his own love of the outdoors, an environment in which the native Coloradan thrives as a hiker and skier – and also where he lives in a mountain home overlooking Denver.

At his first one-man show, held in Den-

ver in 2019, Straus exhibited a newfound technique that wedded modern technology to the tradition of landscape painting. By selecting specific images from personal photographs, he translates colors and shapes into myriad strokes and marks with a “digital brush,” utilizing a computer’s almost limitless palette of color to bring the image to life.

A sense of depth and atmosphere are enhanced in the process, creating a vivid new reality. The work is further heightened by the scale of the paintings, sized either 30 by 60 inches or 45 by 90 inches. Sublimated onto aluminum sheets, the paintings are brilliant, luminous and long-lasting statements that engage and envelop the viewer.

“I choose the specific Colorado landscapes based on the places people love, places where memories are made,” Straus said.

With deep roots in Colorado – his grandparents helped settle Leadville – he always

dreamed of coming back when he lived outside the state. “From London to New Zealand, I carried a Colorado flag with me and mounted it wherever I lived,” he said.

From exhibitions at the American Mountaineering Museum in Golden to the Grand Tetons National Park Museum in Wyoming, his colorful and dynamic work reaches across cultural and geographic boundaries. His success has been further fueled by a commitment to philanthropy, having raised more than $75,000 to date, funding charities and organizations that assist in food insecurity, welfare and housing in Colorado. Straus also funds young artists starting their artistic careers.

Straus is represented by galleries in Vail, Breckenridge, Winter Park, Telluride, Aspen and Boulder, plus Park City, Utah, and has work on display at locations throughout Colorado. His next solo exhibition is in Telluride in February, followed by the Breckenridge Gallery in March. For more of his work, visit topherstraus.com.

by SARA BRUSKIN

Popular feel-good videos on social media show soldiers returning home to their loved ones. Kids run into the arms of a long-deployed parent; a surprised spouse breaks into happy tears. The scenes are heartwarming, but they don’t capture how difficult the following weeks, months and years may be.

Returning to civilian life after military service can be rough, to say the least. Kelley Forrester of Denver saw how difficult the transition was for her husband, Craig Hildebrand, who spent more than a decade in the U.S. Army. She also saw how much their pets contributed to his recovery.

“On days when he could not do anything – couldn’t go to the grocery store –he could still get the dogs out for a walk,” Forrester said. The exercise, fresh air and socialization Hildebrand got on those walks helped alleviate the isolation and stress of his jarring new adjustment. This realization was part of the impetus behind Black Ops Rescue, a nonprofit based in Arvada that matches veterans with animals in need of a home. They also cover the cost of pet supplies, training and the animals’ medical needs.

Forrester and Hildebrand founded the organization with their friend Nicole Schimming in 2018 to help veterans in the Front Range area, and they’ve witnessed time and again how powerful a balm animal companionship can be. “No matter what the veteran has going on physically or mentally, there’s a being in the house who loves them no matter what, even when they’ve maybe become isolated from family or friends,” Forrester said.

She’s also found that dogs are a reassuring presence for those suffering from PTSD. Knowing that an animal with an acute sense of smell and hearing is looking out for danger makes it easier for a person carrying trauma-related stress to relax the hypervigilance they usually maintain. Of course, the pets are so much more than security systems, and are selected for different qualities.

U.S. Navy veteran Bo Schomburg and his family take a hike with rescue dog Tango. Nonprofit Black Ops Rescue helped match the pup with the veteran.

Bo Schomburg, a U.S. Navy veteran who adopted a dog through Black Ops Rescue, was looking for one that would be good with kids and have the endurance for family adventures.

Through a partnership with The Good Dog Rescue, Black Ops Rescue found an affectionate little pup named Tango who fit right in with the Schomburgs, even getting along with the family cat. To pay it forward, Schomburg raises money for Black Ops Rescue through his insurance business, and his wife, Rena, volunteers as the event coordinator for the organization.

This community of veterans helping veterans is exactly what Forrester hopes to cultivate. She aims to expand into a brickand-mortar location in the future, where they can hold animal training sessions, fun skill-building classes and other group events for veterans.

“We do what we do because animals and veterans deserve it,” Forrester says. “Every homeless animal deserves to be out of a shelter, out of a rescue and in a loving home. And every veteran deserves a buddy they can always depend upon.”

Visit blackopsrescue.org for information on the organization, donations, volunteering and adoptions.

by TOM HESS

At Rino’s Italian Restaurant and Steak House in Trinidad, the waitstaff serve plates of chicken Florentine and penne rustica, and then grab a cordless microphone and start to sing. Leading the meal service and singing is owner and chef Frank Cordova.

Cordova was born and raised in Trinidad. As a boy, he and his brothers played in the tunnels that run beneath parts of the city, lighting torches – coal oil-soaked rags on a stick – to explore the length of them.

“We used to shoot Roman candles at each other, and they’d bounce off the tunnel wall,” Cordova said. “It’s a wonder we didn’t kill each other.”

One of seven brothers and seven sisters raised by a single mom, Cordova also remembers the family singing in their home on Trinidad’s East Main Street. Music filled their lives.

Cordova’s aunt Ann Rino formed an all-female band, the Colorado Sweethearts, after winning a local talent show in 1947, when Cordova was just 4. Rino received the Colorado Country Music Hall of Fame Pioneer Award in 2013.

Cordova pursued his own music career with his brother Bob, performing in Los Angeles with artists such as the Righteous Brothers and Tina Turner. Frank and Bob formed a successful restaurant in Las Vegas, where they waited tables and sang. They brought that formula back to their hometown in 2002.

At Rino’s Italian Restaurant, Frank Cordova works in the kitchen, preparing dishes with recipes he created, and sings for patrons. He prefers songs by Neil Diamond (“Sweet Caroline”), Tom Jones (“I’ll Never Fall in Love Again”) and at least one Italian clap-along song by the famed singer Andrea Bocelli.

The restaurant occupies a former church building constructed in 1887. The

building later housed a Mexican restaurant, whose orange paint Frank’s wife, Valerie, sanded off to reveal underlying cherrywood.

Valerie created murals throughout the restaurant, in an Art Nouveau style, picturing women in robes and adorned in flowers. A mural above the bar portrays the 1914 Ludlow Massacre, in which local miners and their families were killed during a coal strike.

As colorful and captivating as the murals may be, as tasty as Frank’s recipes may be, it’s the singing that’s most memorable. Taking turns with the microphone is a cook, several waiters and, on Fridays, an Elvis impersonator.

Here’s a suggestion on how best to enjoy the show at Rino’s: Follow the example of the TV show The Voice, turn your chair away from the singers, and you’ll swear you’re hearing American Idol 2006 runner up Katharine McPhee (the voice of purple-haired waitress Melinda sing-

ing “Terrified”) or famed crooner Frank Sinatra (Frank Cordova singing “Fly Me to the Moon”). Then you’ll want to turn your chair back around and applaud.

Inside Rino’s italian Restaurant and Steak House, Frank Cordova holds up a photograph of ancestors Francisco Rino and Maria Chivita Ruscetti.

Using a technique he invented, Freddie Fisher electroplates specially prepared aspen leaves in a gold solution. Fisher sold his leaves in Aspen in the 1960s.

by SARA BRUSKIN

They can be seen in gift shops all over the state: jewelry and ornaments featuring the lacy vein structure of an aspen leaf, sparkling with a thin coating of gold, silver or copper. They’re quintessential Colorado souvenirs, but to look at these delicate, elegant adornments, one would never know their original creator was a champion of corny music and literal trash.

Born in Iowa in 1904, Ferdinand Fredrick “Freddie” Fisher landed in Colorado after a whirlwind music career as “Colonel Corn.” He played a vaudeville-inspired style of big band jazz known as “novelty corn music” with his group, the Schnickelfritz Band. Goofy, spoofy and some-

times slapstick, their act propelled them into movies and a contract with Warner Brothers.

Fisher featured in 15 movies and shorts, and recorded dozens of albums in his time. His band’s 1930s Billboard chart hits included “Horsey, Keep Your Tail Up,” “Sugar Loaf Waltz” and “They Go Wild, Simply Wild Over Me.”

After Fisher’s fame fizzled out and a heart attack slowed him down, he and his wife, Marge, moved to Aspen in 1952 for a quieter life. Fisher opened a fix-it shop on Main Street and would tinker with everything he could get his hands on.

He even placed ads in The Aspen Times, asking people to bring their interesting garbage to him instead of throwing it

Bird watchers are finding their perfect playground on the Pioneering Plains of northeast Colorado. The natural backdrop of Plains areas in Sterling and Logan County invites birders to journey off the beaten track in search of new encounters with a variety of species in an unspoiled environment.

Did you know there are more than 300 species

out. When someone brought him an old cast-iron bathtub, he attached skis to the bottom and rode it as a float in Aspen’s Wintersköl parade. Quickly becoming a well-known character in town, Fisher would jam with other local musicians on his clarinet, and he was known for sifting through trash at the junkyard, earning him the nickname “King of the Dump.”

It was during Fisher’s fix-it days that he developed a process for creating the now-ubiquitous aspen leaf jewelry. He would submerge leaves in a chemical solution that would dissolve the plant tissue but leave the veins intact. These leaf skeletons would then go through a process known as electroplating, which builds up metal deposits on an object’s surface. Fisher made and sold his leaves until he died in 1967 from a second heart attack.

These days, his craft is carried on by the Rocky Mountain Leaf Co. The business opened in Aspen in 1974 using Fisher’s

The Rocky Mountain Leaf Co.’s gold and silver aspen leaves are made using Freddie Fisher’s technique, the details of which his family shared with the company founders.

technique, which was shared by his family and friends. The company is now much larger – picking 100,000 Colorado aspen leaves annually – and based in Golden,

supplying shops all over the world with Fisher’s creation. His memory also lives on in Freddie Fisher Park at 1102 E. Cooper Ave. in Aspen.

Test your knowledge of Colorado food and restaurants. by BEN KITCHEN

1 A plaque outside of an urgent care center in the state’s capital city features a recipe for what breakfast dish? It calls for eggs, ham or bacon, green pepper and onion.

2

In 2021, the creators of South Park purchased what iconic Lakewood establishment, noted for its cliff divers and sopaipillas, after it filed for bankruptcy? It was slated to reopen last summer, but technical issues have pushed that back indefinitely.

3

Silver Grill Cafe in Fort Collins is the oldest restaurant in the city. The “History” section of its website is divided into two portions – one for the history of the establishment, and one for the history of their recipe for what pastry that they specialize in?

4

The first restaurant in what regional chain was founded by its two namesakes in Idaho Springs in 1971? Its website humorously claims that they were founded by a fur trapper named Pete ZaPigh.

5 Colorado Springs restaurant The Rabbit Hole is themed around Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which is reflected in its name and the artwork featured inside. Keeping with the theme, what’s the two-word name of the restaurant’s cocktail menu?

6 In 1935, a trademark for the word “cheeseburger” was granted to Louis Ballast, the owner of what bygone Denver establishment? Some sources say the restaurant invented the cheeseburger, but it is unclear if Ballast ever made this claim.

a. Humpty Dumpty Drive In

b. Kaelin’s Restaurant

c. The Rite Spot

7

Allred’s Restaurant in Telluride is located just a bit off the beaten path. What method of transportation do diners have to take in order to make it there?

a. Dirt bike

b. Gondola

c. Helicopter

8 The following three burritobased chains were founded in Colorado. Which was established first? It opened in 1993, while the other two opened in 1995.

a. Chipotle

b. Illegal Pete’s

c. Qdoba

9

Take a cheeseburger and cover it in green chili. The result is a slopper, a dish native to which Colorado city? Its origins are disputed, but most say it originated at Gray’s Coors Tavern.

a. Fort Collins

b. Pueblo

c. Vail

10 Often found on menus across northeast Colorado, the cabbage and ground beefbased sandwich variously known as the krautburger, bieroch or runza comes from the culinary tradition of what ethnic group?

a. Czechs from Slovakia

b. Austrians from Switzerland

c. Germans from Russia

11

Downtown Denver’s Mizuna is the only Michelin-starred restaurant in the state, earning one star in the 2021 rankings.

12

The root beer float was invented in 1893 by Frank J. Wisner at Cripple Creek Brewing, located in Cripple Creek.

13

Crested Butte’s The Last Steep has been voted Best Bloody Mary and Best Hamburger in Crested Butte. It gets its name from the founder’s favorite ski run.

14

Colorado has a litany of official state foods, including an official state fruit (Palisade peaches), an official state drink (craft beer) and an official state appetizer (Rocky Mountain oysters).

15

More than 40 Colorado restaurants have been featured on Food Network’s Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives, including The Post Chicken & Beer in Longmont, Tacoparty in Grand Junction and Highlands Alehouse in Aspen.

No peeking, answers on page 66.

story by MATT MASICH

photograph by GLENN RANDALL

WITH THEIR ICONIC shape reflecting in the glassy waters of Maroon Lake, the Maroon Bells are the quintessential Colorado scene in the eyes of many. Yet the two mountains – Maroon Peak and North Maroon Peak – are actually atypical of Colorado’s mountains.

While most of the state’s famous peaks are composed mostly of granite, the Maroon Bells are made of mudstone. This is what gives the mountains their maroon color – and their deadly reputation. Compared to granite, mudstone is far softer and easier to break, which makes for dangerously unstable loose rocks beneath the feet of would-be climbers. In 1965, eight people died in five separate climbing accidents on the Maroon Bells, earning them the nickname “the Deadly Bells.”

When viewed from the shore of Maroon Lake, however, the Bells pose zero threat to life and limb. Each summer, more than 300,000 people come to see this view of the mountains, which have earned a reputation as the most photographed place in Colorado. The peaks are just a short drive from Aspen, but so many people want to visit that automobile access is restricted –those who wish to see them must take a bus departing from Aspen Highlands.

The vast majority of people who have seen the Maroon Bells in person have seen them during the summer. Maroon Creek Road is only open from May through October, meaning the only way to access the peaks in the winter is by hiking, snow biking, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing or snowmobiling in.

Photographers capture frozen Colorado

by MATT MASICH

THE WINTER AIR was a frosty 5 degrees, and the intense wind made it feel even colder. Standing on the frozen surface of Sprague Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park, photographer Verdon Tomajko did his best to steady his camera on its tripod – the wind was so strong that it sometimes pushed him sliding him across the ice.

Tomajko had come to this area to photograph mule deer during their mating season, but something about the frozen lake spoke to him. He decided to brave the elements to wait for sunset, hoping for some clouds to blow in to catch some color. His hopes were realized as the sun sank below the horizon, its fleeting rays turning the clouds pink and orange. The brilliant sky was reflected in the imperfect mirror of the lake’s ice.

Such are the magical images that can emerge from the depths of winter. Tomajko never lets the cold deter his outdoor photography. There’s something about the season that appeals to him. “Wintertime has a special mood for me,” he said. “It’s quiet; it has a different feel.”

Photographers must prepare well before venturing into the icy wilderness. Tomajko has learned that, no matter how good his shoes are, his feet will get cold standing on ice and snow for long periods, so he uses a Therm-a-Rest inflatable sleeping pad to stand on. His tripod’s legs even have spikes on the end so they won’t slide across the ice.

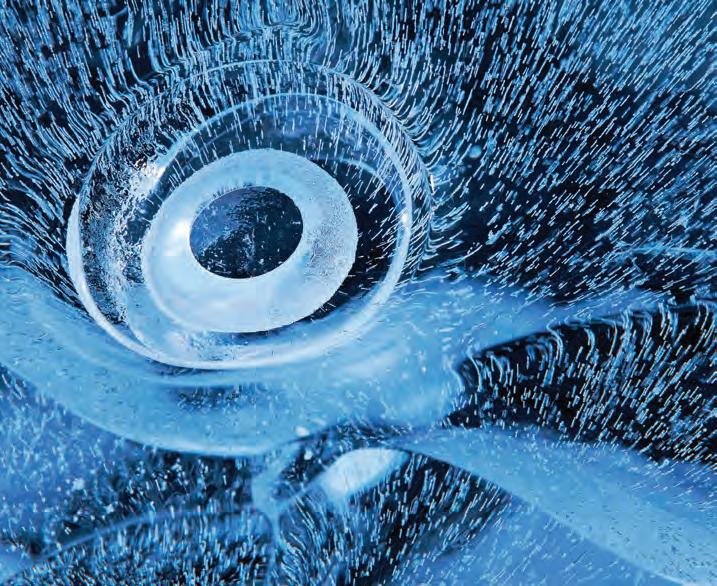

A close-up view of Rocky Mountain National Park’s Lake Haiyaha reveals abstract ice patterns. Ice formations look blue at Dillon Ice Castles. A frozen bubble lies in snow in Fort Collins.

During the winter, landscape photographer Glenn Randall likes to go on multiday camping expeditions to find his photographic subjects. He calls winter “the season of solitude;” the forbidding cold keeps people indoors, meaning he is often the only person around for miles.

Randall recently spent four days snowshoeing in the Gore Range, photographing sunrises and sunsets from a 12,400foot prominence overlooking the Piney River. The first person he saw was on his fourth and final day – someone was snowshoeing in while he was snowshoeing out.

“It feels very wild, very remote,” Randall said. “That’s a rare feeling in today’s world.”

Taking photos in the winter is much more dependent on the elements than in other seasons, so Randall pays close attention to the weather report. Most snowstorms come out of the northwest, he said, but it can be frustrating trying to photograph the resulting snow because they are accompanied by fierce winds that knock all the snow off the trees.

Randall has found that slow-moving winter storms that approach from the east make the best snow to photograph. After the snow stops falling, the easterly wind stops, and there’s usually a brief window of a few hours when all is still before the northwest winds resume. In wintertime, he lives for those moments.

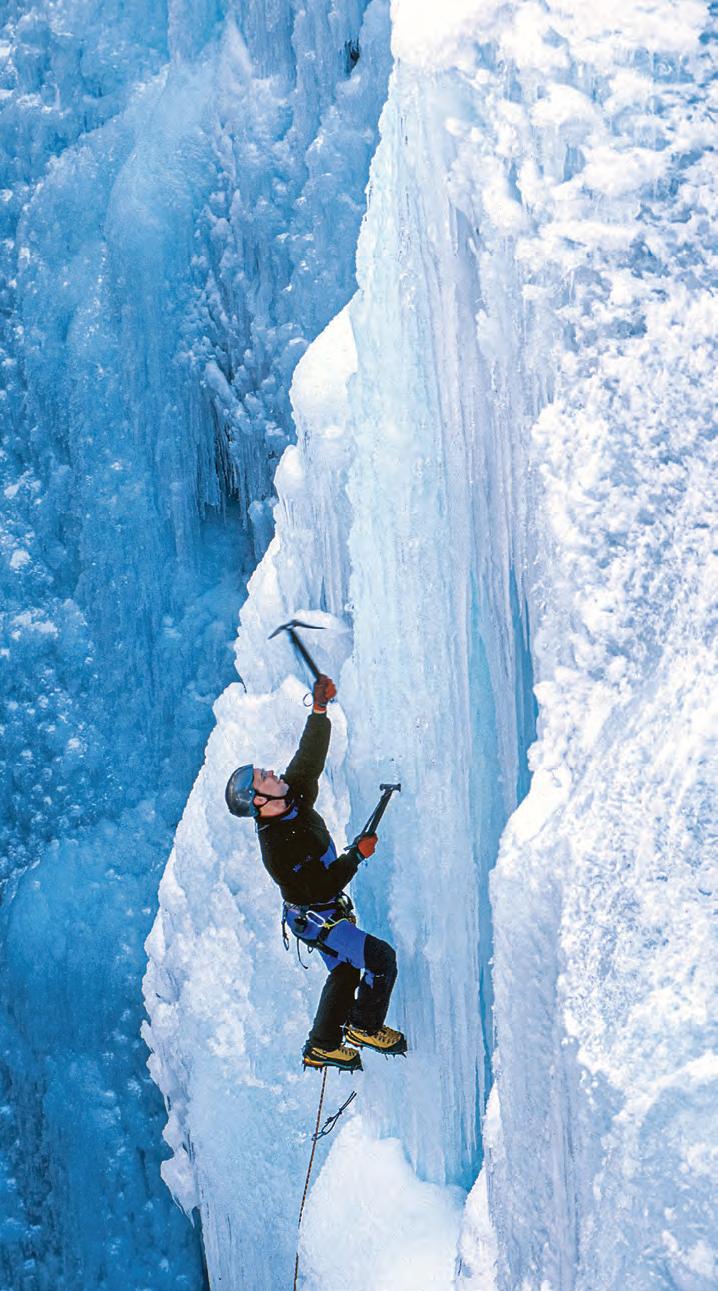

An ice climber scales the frozen wall at Ouray Ice Park during the Ouray Ice Festival. Bison race through the falling snow at the Buffalo Herd Overlook along Interstate 70 at Genesee Park.

Soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division don

while training at

A company performs an “about

Mac Julian/Denver Public Library

10th Mountain Division soldiers trained in Colorado, helped win World War II, then returned to pioneer the ski industry

by MATT MASICH

THE GERMAN SOLDIERS on top of Riva Ridge slept soundly in their dugouts on the night of Feb. 18, 1945. True, enemy American troops were nearby, but to reach the German positions in the mountainous terrain of northern Italy, the Americans would have to scale cliffs as much as 2,000 feet high – a seemingly impossible feat.

However, as dawn broke the next day, the astonished Germans awoke to grenades and gunfire. Somehow, the American soldiers had taken the entire ridgeline in the middle of the night. As it happened, the feat the Germans had considered impossible was just the sort of mission their adversaries had spent years training for. The Americans they faced weren’t ordinary infantrymen; they were the elite alpine troops of the 10th Mountain Division.

This highly specialized fighting force broke the stalemate with German army in Italy at the end of World War II. Part of the reason the 10th Mountain Division was so effective was the training the men received at Camp Hale, situated 9,250 feet high in the Rockies of Colorado, between Leadville and what later became Vail.

These elite mountain troops left a dual legacy. In war, they turned the tide against the Germans in the Italian campaign. In the peacetime that followed, the division’s veterans returned to Colorado to play a huge role in inventing the state’s ski industry.

WHEN WORLD WAR II broke out in Europe in 1939, the U.S. Army had no special mountain troops – it was strictly a flatland force, as recounted in The Winter

Army by Maurice Isserman, the source for much of this article. This didn’t sit well with Charles Minot “Minnie” Dole, who had just the previous year founded the National Ski Patrol. Many European nations had ski troops. Finland, for example, was able to stave off much larger Soviet forces thanks to the mobility of its soldiers on skis.

In July 1940, Dole visited the War Department in Washington, D.C., advocating for the recruitment of skiers to create a special unit of U.S. mountain troops. The officials he met with unceremoniously brushed him off. Undeterred, Dole went straight to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, telling him in a letter on July 18, 1940, that “it is more reasonable to make soldiers out of skiers than skiers out of soldiers.”

This set the ball rolling. Dole met with Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall, who authorized ski training for a small number of troops that winter. However, it wouldn’t be for another year, in November 1941, that the Army formed what came to be known as the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, to be stationed at Fort Lewis in Washington state. It was the first regiment of the 10th Mountain Division.

The Army asked Dole and his National Ski Patrol for their assistance recruiting and vetting skiers and other outdoorsy types for the mountain troops. The patrol created a three-page questionnaire for candidates, quizzing them about their outdoor qualifications and asking for three letters of recommendation from athletic coaches or other qualified people.

Soldiers learn to march and ski at Camp Hale, situated 9,250 feet above sea level in the Sawatch Range between Leadville and what eventually became Vail. At its peak in 1944, Camp Hale was home to 12,000 soldiers training for winter warfare.

In the early 1940s, skiing was a pastime largely enjoyed by the privileged classes who could afford to attend college. Consequently, many mountain troop recruits came from college ski clubs. At a time when only 10 percent of U.S. Army soldiers had attended college, some 50 percent of 10th Mountain Division soldiers had – and that doesn’t count the high school graduates who were planning to go to college before enlisting.

Volunteers for the new mountain unit included some of the best-known skiers in the nation, such as Torger Tokle, a young Norwegian immigrant famous for shattering distance records in the ski jump.

The mountain troops, few but steadily growing in number, spent the winter of 1941-42 practicing skiing techniques on Washington’s Mount Rainier. However, their stay in Washington was only a layover until their permanent base was finished being built in Colorado.

In the Eagle Valley of Colorado’s Sawatch Range, home of the state’s three highest peaks, civilian laborers spent the better part of 1942 building Camp Hale for the new mountain units. Workers built barracks, mess halls, warehouses, training facilities, office buildings, theaters and more – enough for the thousands of men who would train here. For ski training, lifts were installed near the camp on the beginner-level B Slope and further afield near Tennessee Pass at the larger, more advanced Cooper Hill.

The Army chose to build Camp Hale in Colorado’s Sawatch Range because the high altitude meant that winter effectively lasted six months a year. When the troops finally got there in late 1942, they would learn just how cold that long Rocky Mountain winter could get.

In addition to their skis, soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division tote heavy rucksacks and M1 Garand rifles. The vast, snowy wilderness surrounding Camp Hale proved the perfect training ground. Donald F. Favreau strikes a pose with his rifle.

Men from the 10th Mountain Division escort German prisoners of war near Rocca di Roffeno, Italy; the division captured many enemy soldiers after breaking through fortified German lines in the Apennine Mountains. Sgt. John K. Coyle paints a sign for the division headquarters during the Italian campaign. Medics tend to a soldier wounded in the leg while fighting in an Italian village.

THE 87TH REGIMENT arrived in full force at Camp Hale in December 1942. It was soon joined by the 86th Regiment and later the 85th Regiment. Together, these three regiments – a combined 14,000 men – would form the 10th Mountain Division.

The soldiers began their training, practicing marksmanship on the rifle range and undertaking long days of skiing. By February 1943, commanders thought the men were ready to go on maneuvers to put their training to use. A battalion from the 87th Regiment was tasked with ascending 13,209-foot Homestake Peak and creating a defensive line below its summit.

The training maneuvers were supposed to last eight days. However, they were canceled when, after the first full day, 25 percent of the troops were already out of commission with frostbite or other maladies largely related to the extreme cold. Part of the blame for the fiasco went to the officers, who were not drawn from the same pool of skiers and outdoorsman as the enlisted men. Afterward, the officers decided to rely more heavily on the expertise of their men.

When the 10th Mountain Division soldiers weren’t practicing skiing and rock climbing, they explored Colorado on 36-hour weekend passes. Some went

to Denver, where a few of them horrified the staff of the Brown Palace by demonstrating rappelling techniques in the hotel’s nine-story atrium. Others went to Glenwood Springs, Grand Junction and Aspen, where at the Jerome Hotel they drank a concoction called “Aspen Crud” –a milkshake fortified with bourbon.

Friedl Pfeifer, who had been a champion skier in his native Austria before joining the 10th Mountain Division, was particularly impressed by Aspen, which didn’t then have a ski area. He could envision ski runs coming down into town. Reflecting on his first visit to Aspen, Pfeifer later recalled that he “felt at that moment an overwhelming sense of my future before me.”

The division spent all of 1943 training, with the exception of the 87th Regiment, which was deployed to the Alaskan island of Kiska. The island had been occupied by Japanese troops since the previous year, and the Allied forces’ amphibious landing on Aug. 15, 1943, was expected to meet with stiff resistance. Yet when the mountain troops and other units came ashore, not a single shot rang out.

The soldiers of the 87th Regiment spent all day ascending the 1,800-foot ridge at the center of the island. As night fell,

gunfire broke out. The shooting lasted all night, but when morning came, no Japanese soldiers could be found. It turned out that the Allied troops had been firing at each other in the dark. Some 28 Americans were killed, including 19 from the 87th Regiment. The regiment rejoined the division at Camp Hale in January 1944.

The next major training event came in March 1944, when the division, nearly full strength at 12,000 men, participated in what was known as the D-Series maneuvers. The soldiers, carrying 90-pound rucksacks, set off into the wilderness on skis to engage in mock combat scenarios in temperatures as low as 35 degrees below zero. The three-week training exercise was so grueling that later, once the men were fighting in the actual war, they joked that if things got any worse, it would be as bad as D-Series.

BY MID-1944, THE soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division were well-trained –too well-trained for many of the men’s liking. After two years practicing for mountain combat, they were ready to see some real action. They shipped out of Camp

Hale in June 1944 and were stationed in Camp Swift in Texas, awaiting deployment. That finally happened at the end of the year, when the division’s three regiments boarded ships in Virginia bound for Italy.

When the 10th Mountain Division arrived in full strength in Naples in January 1945, Allied forces had been fighting the Germans in Italy for more than a year. Rome had been captured, but the Germans were making a stand at what was known as the Gothic Line. This defensive line had strong fortifications in the Apennine Mountains, guarding the Po Valley and its major city of Bologna. The mountain troops would be part of the Allied push to break the Gothic Line.

When 1st Lt. David Brower got to the front lines in the Apennines, the scene was familiar. “We were soon in snow-covered mountains with a cold snowstorm in progress,” he said, “and we could think back to Camp Hale and D-Series.”

The 10th Mountain Division’s position faced a German force that was dug in on the slopes of Mount Belvedere. The Germans also occupied Riva Ridge on the di-

vision’s left flank, which overlooked the approach to Mount Belvedere. The prospect of attacking such formidable positions was daunting. Lt. Col. Henry J. Hampton said it was like sitting “in the bottom of a bowl with the enemy sitting on two-thirds of the rim looking down upon you. There was about as much concealment as a goldfish would have in a bowl.”

Before the division would attempt a full-scale assault, it sent small groups of soldiers on patrols. Though the mountain troops had trained extensively on skis, the only time they used skis in combat was in a few small patrols in the first few weeks after their arrival.

Staff Sgt. Dick Nebeker was on one mission that had the men ski toward some German-occupied stone houses. Someone hit a tripwire, alerting the Germans, who opened fire. The Americans got down on their bellies to take cover. They soon realized they were better off without skis and took them off, never to put them on again. “Two winters at Camp Hale trained us for 10 minutes of creeping and crawling under enemy fire with skis on,” Nebeker said.

During January and the first half of February, Allied commanders were trying to figure out how the division would take Mount Belvedere. Several attempts by other American divisions had failed to capture the mountain, but all of these attempts had ignored Riva Ridge. With Germans occupying the ridge, they could see everything the Americans were doing and call in accurate artillery fire.

The 10th Mountain Division was tasked with scouting out a way up Riva Ridge. During nighttime patrols, the mountain troops found five trails up the steep cliffs, several of which required technical climbing with ropes and pitons, just as they had trained for at Camp Hale.

The attack on Riva Ridge began as darkness fell on Feb. 18, 1945, when men from

two battalions of the 86th Regiment began ascending the trails. They were instructed to hold their fire until morning so as not to alert the Germans that anything was amiss. A fog rolled in during the six hours it took to scale the cliffs, helping conceal the Americans when they reached the top of the ridge at 1 a.m.

The mountain troops took the entire ridgeline with only one man wounded and none killed, catching some Germans asleep in their foxholes. The Germans then counterattacked, inflicting more casualties, but the 10th Mountain Division held strong.

Meanwhile, the bigger assault on Mount Belvedere was to commence just before midnight the night after the assault on Riva Ridge. The 85th and 87th regi-

ments had to cross minefields while under heavy machine gun and artillery fire. Despite intense German opposition, the men from the 10th captured the summit of Belvedere just before dawn.

But there were other smaller, connected ridges and mountains nearby still left to capture. Some of the most intense fighting happened on Mount Gorgolesco, where the Germans had heavily fortified the summit. Sgt. Hugh Evans was fighting his way up Gorgolesco when he came across his good friend Tech. Sgt. Robert Fischer lying on the ground, shot through the lungs. Fischer kept repeating: “Oh God. Please not now. Please not now.”

Evans began to tear a piece off a jacket to make a bandage, but Fischer died before he could apply it. Evans’ eyes filled

The American flag flies above the 10th Mountain Division memorial at the summit of Tennessee Pass near Leadville. While only a few ruins remain at Camp Hale, the area was last year designated as Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument.

with tears of rage. He charged up the hill toward the German machine guns. He called for others to join him, and a few did. He and two other men got within a few feet of the German positions and threw grenades, then jumped into the trench.

For the next 10 minutes, Evans kept moving, throwing grenades and firing his automatic weapon. When it was over, eight Germans were dead, 20 were captured, and the objective was taken. Evans was awarded the Silver Star for his exploits.

Commanders had expected it to take two weeks for the 10th Mountain Division to capture all the objectives on the Belvedere massif. Instead, it took them just five days. It was the first significant progress in the Italian campaign in four months. But the cost was steep, with the division losing 192 killed in action and 730 wounded.

BY MARCH 1945, the end of World War II in Europe was in sight. Soviet armies were closing in on Berlin from the east, while American and British armies were entering Germany from the west. Meanwhile, the 10th Mountain Division and other Allied forces in Italy were starting to break the Gothic Line.

The division launched another offensive to take more mountains and hills, losing another 146 killed and 512 wounded. Among the dead was ski jumping champion Torger Tokle, who volunteered to go with a bazooka man to take out a German machine gun. They were hit by artillery

fire, which detonated the bazooka rounds they were carrying, killing them both.

Even with the war clearly drawing to a close with the steady collapse of enemy defenses in Germany, Allied commanders planned one final offensive in Italy to finally break into the Po Valley and Bologna. The assault began on April 14, 1945, when 1,000 Allied bombers and 2,000 artillery guns rained destruction on the German lines.

The Germans were making a last stand, forcing the 10th to pay dearly for every inch of territory. The division’s objectives were a series of numbered hills, with particularly nasty fighting happening on Hill 913 – Medic Murray Mondschein wrote that “913 made Belvedere look like kindergarten.”

Bob Dole, the future U.S. senator and presidential candidate, was a lieutenant in the 10th during this attack. He later wrote that the Germans “started pouring artillery, machine gun and mortar rounds into the clearing in front of us, mowing down

Vail has become one of the nation’s most prominent ski resorts; its longest ski run is named after one of the 10th Mountain Division’s greatest victories. A skier takes a run on Aspen Mountain; division veteran Friedl Pfeifer came to Aspen, co-founded the Aspen Skiing Co. and oversaw the construction of its first lift. On next page, skiers set out from a 10th Mountain Division hut.

dozens of American soldiers, shredding others, pulverizing still more.” While attempting to help a wounded comrade, Dole was shot in the upper back, paralyzing his right arm.

On Hill 909, Pfc. John D. Magrath charged a German machine gun nest, killed two of the gun crew and wounded three. He then dropped his rifle, grabbed the German machine gun and neutralized two more enemy machine gun positions. Soon thereafter killed by a mortar shell, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In the three days it took to take the hills, the division lost 286 killed and 1,047 wounded. But they were beginning their descent toward the Po Valley, entering flat terrain for the first time since arriving in Italy. They were now advancing at a rapid pace.

By April 20, 1945, they reached the valley and captured a bridge. Other Allied troops entered Bologna the next day. That same day, the 10th sent a task force to press the retreating Germans. The task force advanced 55 miles in two days, reaching San Benedetto di Po and crossing the Po River on boats.

The division pushed forward to Lake Garda, where Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had abandoned his villa. Men from the 10th took many of Mussolini’s personal effects as souvenirs. By April 30, the division had advanced 115 miles in 17 days. Two days later, the German armies in Italy surrendered; within a week, the German armies in Berlin did the same.

The war was over for the 10th Mountain Division. All told, 20,635 men – including combat replacements – served in the division in Italy; 983 were killed in action, 3,900 were wounded and 20 were taken prisoner.

WHEN THE 10TH Mountain Division was inactivated at the end of 1945, many of its veterans who fell in love with Colorado during their time at Camp Hale returned to the state. Some came simply to become the first ski bums, but many eventually started careers in the nascent skiing and outdoors industries.

Friedl Pfeifer, who had a vision of his future in Aspen, moved there in fall 1945,

having survived a life-threatening chest wound on the first day of the April offensive. He co-founded the Aspen Skiing Co. and the next year oversaw the construction of Aspen’s first ski lift.

In 1946, Gerry Cunningham founded the Gerry Mountaineering outdoor sports gear company in Ward. He invented the modern triangular carabiner and created tents used in the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953.

Also in 1946, Lawrence Jump, with help from some of his comrades from the 10th, founded Arapahoe Basin Ski Area.

Pete Seibert came to Aspen after the war. First, he had to recover from severe injuries from an exploding shell –shrapnel tore off his right kneecap and knocked out some of his teeth. Seibert dreamed of starting his own ski resort. While exploring the area near Camp Hale in 1957, he climbed to the top of Vail Mountain and had a vision to create his resort there. Vail Ski Resort opened in 1962; the town of Vail was incorporated four years later. The name of Vail’s longest ski run is a tribute to one of the 10th’s greatest victories: Riva Ridge.

Camp Hale was demolished shortly after the 10th Mountain Division finished training there, but the memory of the mountain troops’ time in the Colorado mountains remains strong. On Oct. 12, 2022, President Joe Biden came to the site of Camp Hale to declare its protection as Camp Hale-Continental Divide National Monument. Though only a few concrete ruins remain at the main camp, the soldiers’ training slope at Cooper Hill is still in use as a ski area, now known as Ski Cooper.

The best place to learn more about the 10th Mountain Division is the Colorado Snowsports Mu-

seum in Vail – a town that didn’t exist until a veteran of the division founded Vail Ski Resort. The museum’s “Climb to Glory” exhibit features gear and artifacts used by the mountain troops at Camp Hale and fighting in Italy.

The memory of the division is also kept alive by the 10th Mountain Division Hut System, co-founded in the 1980s by a veteran of the division. More than 30 backcountry huts are located in the Camp Hale area and the mountains beyond. They are rented out to people engaging in backcountry skiing and other outdoor winter pursuits that the men of the 10th Mountain Division did.

Colorado is rich with natural beauty, history and colorful towns. Our poets celebrate the Centennial State in all its multifaceted glory.

Robert Basinger, Rifle

It’s a sweet kind of light, Light that has undergone great change. Cloud-filtered, mountain-brewed sweetness. Icy crystals on my coat

Icy breath, frozen fingers

I’m so thankful our seasons don’t linger. On to the next with an open heart

And deep, sky-blue reflections in my eyes. Brought my camera along, that’s sweet. Best friends, looking for frozen treats.

Charles Ray, Evergreen

night unfolds into quiet darkness sprinkled with sparkles of infinite stars floating in an enormous unexplored sea exciting childlike unanswered wonders to the endless complexity of the universe and my own short-lived simplicity illuminated in the lunar light

Keith Gogan, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Alamosa almost a desert but 7,500 tiny feet lift it just high enough to drink from the sky and the drainage from the sour-cream-dollop-top Sangre de Cristos looking down on dunes and fields of potatoes: no famine here! but up the road the UFOs have landed and down the road lies a New state of Mexico handed the Rio Grande baton-like to carry the sky’s blessing to the sea

Stan Richardson, Colorado Springs

Winter dusk

A crow calls Three caws

Hopeful thoughts Find no purchase

Drifting Away on frigid air

Leo Lohman, Arvada

I met a nice young fellow He asked me where I’m from I told him Colorado

That kingdom in the sun

He asked me if I’d tell him

What it’s really like I told him close your eyes And pretend you’re on a hike

The sky is brilliant azure

The air is crisp and dry

Like silent quotes from angels

The clouds go drifting by

The little brook is singing A simple wordless tune Its breathless cadence follows The rhythms of the moon

The breeze is lightly scented With wildflowers and pine

The impact on your senses Is in a word “divine”

I asked him “can you feel it” He told me that he could He asked me “please continue” And I told him that I would

The flowers paint the meadows With lovely shades of blue And white and pink and yellow And greens of every hue

The chipmunks in the treetops Bicker with the birds

They have a special language That has no need of words

The snow peaks in the distance Sparkle clean and white

Like opals, pearls and diamonds They give off their own light

The young man said, “I’ve got it” I smiled and shook his hand For words can never capture The glory of this land

Richard D. Babcock, Colorado Springs

I moved here. They said, “Don’t come! Too many here already!”

I laughed and packed anyway. Drove the plains of Kansas And Eastern Colorado till I found my home in the Black Forest of the Colorado foothills.

Now, I say, “Don’t move here! It’s too crowded. Too many here already!”

We are like that, we humans.

Vaughn Neeld, Cañon City

Garnered from the gravel lying along the shore of the lake –a rock – nondescript except for ribboned striations.

At home, it yields to my hammer, splits too easily asunder revealing its crystalline cavity, a tiny Carlsbad, a creation only time and mystery could sculpt –

Nature’s tiny jewel resting in the palm of my hand.

DO YOU WRITE poems about Colorado? The next poetry theme is “Sunrise” for March/April 2023, deadline Jan. 15; the theme is “Gardens” for May/June 2023, deadline March 15. Send your poems, including your mailing address, to poetry@ coloradolifemag.com or to Colorado Life, PO Box 270130, Fort Collins, CO 80527.

recipes and photographs by DANELLE MCCOLLUM

THERE ARE FEW foods that aren’t improved by adding bacon – especially when it comes to appetizers. Whether you’re having a party or simply need something to snack on while watching the big game, you can’t go wrong with these baconized apps.

Cherry tomatoes are stuffed with a mixture of crispy bacon, mayonnaise, fresh veggies and Parmesan cheese in these adorable little appetizers. For scooping out the tomatoes, small measuring spoons work well. Don’t skip the step where you allow the tomatoes to drain on paper towels. If you’d like your tomatoes to stand up on the serving platter, slice a very tiny bit off the bottom so they sit flat.

Cut thin slice off top of each tomato. Scoop out the pulp and discard. Invert tomatoes onto paper towel and allow to drain for about 30 minutes. Meanwhile, in medium bowl, combine bacon, mayonnaise, Parmesan cheese, red pepper, green onion, parsley and salt and pepper. Generously stuff each tomato with bacon filling. Cover and refrigerate for at least one hour – and up to three hours – before serving.

2 10-oz packages cherr y tomatoes

6 slices bacon, cooked crisp and crumbled

1/2 cup mayonnaise

1/4 cup Parmesan cheese

1/4 cup finely diced red pepper

2 green onions, chopped

1-2 Tbsp chopped fresh parsley

Salt and pepper, to taste

Ser ves 12-14

Miniature crusts are filled with a mixture of bacon, tomatoes, basil and Swiss cheese in these simple and delicious appetizers. These can be made ahead, frozen, then reheated. Mozzarella and Monterrey jack cheese can be used instead of Swiss.

Fry bacon until crisp; drain on paper towels and crumble into medium bowl. Cut biscuits into quarters. Press each biscuit piece into one section of lightly greased mini muffin tin to form a cup. Add chopped tomato, green onion, cheese, mayonnaise and basil to bacon and mix well. Season with salt and pepper, to taste. Divide bacon and tomato mixture evenly among the muffin cups. Bake at 375° for 10-12 minutes, or until heated through and golden brown.

10 slices bacon

3 Roma tomatoes, chopped

2 green onions, chopped

6 oz shredded Swiss cheese

1/3 cup mayonnaise

1/2 tsp dried basil

1 16-oz can Pillsbur y Grands biscuits or similar

Salt and pepper, to taste

Ser ves 18-24

This hot, cheesy dip is loaded with green chiles, bacon and chorizo for an over-the-top appetizer or game-day snack. The queso dip can be made in a skillet and served right from the pan, but it also can be transferred to a slow cooker to keep warm.

In large skillet over medium heat, cook bacon until crisp. Remove from pan and drain on paper towels. Set aside. Add chorizo to skillet, along with onions and garlic, and cook until no longer pink, breaking up as you cook. Drain grease from chorizo and set aside with bacon. Wipe out skillet.

Add diced tomatoes, green chiles and Velveeta to skillet and cook until cheese is melted. Stir in shredded pepper jack cheese and evaporated milk and continue to cook and stir until cheese is completely melted and smooth. Return bacon and chorizo to skillet and stir to combine. Stir in cilantro and serve hot with tortilla chips.

6-8 slices bacon

8 oz chorizo

1 small onion, diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 10-oz can diced tomatoes and green chiles

1 4-oz can diced green chiles

1 lb Velveeta cheese, cubed

2 cups shredded pepper jack or Monterrey jack cheese

1 12-oz can evaporated milk

1-2 Tbsp chopped fresh cilantro Tortilla chips, for serving

Ser ves 8-10

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag.com or mail to Colorado Life, PO Box 270130, Fort Collins, CO 80527.

Historic Colorado Springs resort creates its own special world at the foot of Cheyenne Mountain

by TOM HESS

EXITING INTERSTATE 25 at Lake Avenue in Colorado Springs and heading uphill and west toward Cheyenne Mountain, the view through the windshield evolves – from a series of traffic lights and a swarm of retail signs to a leafy canopy. As Lake Avenue ends, The Broadmoor resort rises above the trees, with its flowered roundabout.

The drive is a revelation: that The Broadmoor is to Colorado Springs what the tiny nation of Vatican City is to the metropolis of Rome – a place set apart, a shimmering bubble of curated beauty where guests find room for contemplation and, in hard times, consolation.

Both the late founder and newer owner of The Broadmoor embrace a 1910 cowboy poem, “Out Where the West Begins,” bronzed at the hotel’s main entrance, offering a heartfelt howdy to those who make their way to the always-open front door of this outpost of Old West hospitality. The poem begins:

Out where the handclasp’s a little stronger, Out where the smile dwells a little longer, That’s where the West begins

The Broadmoor is a city within a city, a place that has developed its own rich history and culture in its 105-year existence. The hotel complex and sprawling grounds are immaculately kept, creating an air of perfection. An enormous and enormously busy staff works day and night to maintain that perfection.

Guests have included the world’s richest and most famous, starting with John D. Rockefeller, who was the guest of honor at the Broadmoor’s private opening ceremony. Since then, the resort has regularly welcomed presidents – including Dwight D. Eisenhower and both Bushes – and Hollywood legends, from John Wayne to Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Built in 1918, Broadmoor Main is the centerpiece of the 5,000-acre resort at the edge of Colorado Springs. The Broadmoor has hosted some of the world’s most famous people.

The Broadmoor covers 5,000 acres with three distinct hotel structures – Main, South and West – which have a combined 784 guest rooms and suites. Some 2,000 staff members keep things running, with more staff added in the summer. The hotel buildings encircle The Broadmoor’s scenic Cheyenne Lake, with its resident swans and close-ups of the Rockies, the structures united by their pretty-in-pink stucco.

Guests sometimes choose to stay instead in luxuriously rustic cabins that The Broadmoor opened in nearby wilderness: Cloud Camp atop Cheyenne Mountain’s The Horns peak, Emerald Valley Ranch deep in Pike National Forest and Fly Fishing Camp on a private stretch of river to the northwest, each of them a narrated Broadmoor drive away.

The resort has had just three private owners since it opened in 1918. First were its founders, Spencer and Julie Penrose, and later their foundation, El Pomar. Next came the Gaylord publishing family of Oklahoma, which also owns Opryland in Nashville. In 2011, Philip Anschutz – the namesake of the University of Colorado medical campus – purchased the Broadmoor for a reported $1 billion.

RUNNING THE BROADMOOR is a monumental task, led by two executives: one a former Michigan girl who learned about family and hospitality in her father’s factory bar, and an aspiring Ohio golfer who rose through the ranks at a famed West Virginia resort.

Together, they apply their years of hospitality experiences to the logistics of leading the large staff of a place that seems more like an independent city than a resort.

The Broadmoor resort isn’t a city in a legal sense, but it has had the services typical of one. The Broadmoor at one time ran a one-car police force, its own water district, sanitation district, gas station, grocery, florist and pharmacy. However, all that is gone.

Among the Broadmoor structures that locals miss most is the original Broadmoor World Arena, built on the hotel grounds in 1939 and demolished in 1994, making way for Broadmoor West. From 1948 to 1976, the venue hosted U.S. and world figure skating championships.

President Dwight Eisenhower chats with his golfing buddies before a round at The Broadmoor Golf Club. All told, 10 presidents have stayed at the resort over the years.

Among the skaters who helped make the arena famous is Peggy Fleming, a Cheyenne Mountain High School graduate who won U.S. and world skating titles and a gold medal at the 1968 Winter Olympic Games in Grenoble, France.

What’s newer at The Broadmoor: Café Julie’s, a coffee and confection shop in the main hotel building, where guests and visitors watch chocolatiers in action behind glass. Across Cheyenne Lake, in Broadmoor West, chefs prepare pasta for dishes served at The Broadmoor’s Italian restaurant, Ristorante Del Lago, in front of a rapt audience.

Consider Jack Damoli, the golfer, as The Broadmoor’s resolutely positive and proper mayor. His official title is president and chief executive officer. Damoli keeps his eye on continuous improvement of aging infrastructure – Broadmoor Main is more than 100 years old. That would explain why he doesn’t always have time for a weekly round of golf on The Broadmoor’s courses, though his Callaway bag of clubs stands ready in his office.

Think of Ann Alba, who worked in her father’s bar, as the fireball vice mayor. Alba spends most of her waking hours darting from place to place managing the day-today, keeping the hotel’s guests happy from reservation to arrival to departure and beyond. That requires a lot of cheerful patience, and sometimes bringing her fearsome hammer down on support staff who fall short, with a pat on the back and maybe a hug when they catch on or catch up.

It’s all a Sisyphean task for everyone involved, from the executive suite to the massive laundry operation, to sustain the Broadmoor Bubble – like rolling a boulder up a hill and doing it again the next day, employees reassuring each other that “we’re living the dream” of building guests’ lifelong memories.

Memories count. Alba keeps in regular contact with five-generation guest families – those that return generation after generation for photographs in the same places their forebears once stood, often in the mezzanine with Cheyenne Lake in the background, and for more memory making.

Penrose made his fortune in Colorado gold and Utah copper, and he invested his wealth in Colorado Springs. First, he completed the Pikes Peak Highway in 1916, as auto travel gained popularity. That same year Penrose started the Pikes Peak Hill Climb, the nation’s second-oldest auto race, behind the Indianapolis 500, to promote his highway. The Hill Climb ran its 100th race last summer.

Penrose completed The Broadmoor in 1918. He lured New York travelers west to the frontier property by hiring the designer of New York’s Central Park to design the grounds of his hotel, and the architectural firm that designed New York hotels.

Crisis struck soon after The Broadmoor opened its doors. First came the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, and then in 1920, the federal government banned the production, importation, transportation and sale of alcohol. Penrose denounced the law as unfair. Penrose’s guests wanted alcohol, so he served it to them anyway. Proof of it can be seen in the Main ho-

tel, in Bottle Alley, a display next to the Broadmoor steakhouse La Taverne. Bottle Alley displays empty bottles that were stashed away during Prohibition and later exhumed.

A bottle of more recent vintage is also on display – an empty bottle of Jordan Cabernet autographed by George W. Bush, later the 43rd president of the United States. Bush told the Broadmoor staff that after viewing his bar bill, he never wanted to drink again, a vow he kept.

Penrose joined his guests in drink, and for etiquette’s sake, he made certain adjustments for it. He had lost an eye in an accident and, for social drinking, he ordered a blood-shot replacement to match his surviving eye. He would swap back and forth the blood-shot and a white one as needed.

As with alcohol policy, Penrose had an independent streak in his choice of politics, and friends. He voted straight Republican but counted a few Democrats as friends and allies. He voted for Franklin Roosevelt, a Democrat elected president

An ornate ceiling and chandelier greet guests in the lobby of Broadmoor West. Dinner is served at the rustically elegant Cloud Camp, one of The Broadmoor’s satellite properties in the mountains.

four times, because Roosevelt supported repeal of Prohibition.

The Broadmoor community joined in Penrose’s stubbornly independent political streak. The hotel’s immediate neighbors and Penrose’s friends preferred not to pay taxes for Colorado Springs city services, so they opposed annexation.

The Broadmoor community formed its own fire district in 1949 after Colorado Springs said its fire department wouldn’t respond to its calls. Like death and taxes, though, annexation was inevitable. The Broadmoor became part of Colorado Springs in 1980.

THE BROADMOOR FIRE Department is still operating; Broadmoor-area residents keep voting to fund it. The hotel and the fire department do not report to each other; they are separate but work closely together. The fire station is the first to respond when the hotel calls on a dedicated line. It receives 1,000 calls a year, 80 percent of them medical.

The department has a four-minute response time for Broadmoor guests, said Chief and Paramedic Noel Perran, a 44year veteran of the district, and fire chief

since 2000. The fire district serves not just The Broadmoor but also 1,100 properties in the Broadmoor community.

The fire district also responds to calls from the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. When a veterinary dentist prepared to clean the teeth of a Bengal tiger named George, the zoo needed a paramedic to run an IV to anesthetize the animal. Perran is a trained paramedic. He shaved a spot on the tiger’s haunch and started the IV.

With all of The Broadmoor resort’s deep history, there’s something else new: weekly chapel services.

On Sundays, Broadmoor guests and locals attend 9 a.m. services at the Pauline Chapel, the stand-alone church done in the same pink stucco as the hotel. Julie Penrose had the chapel built in 1919 and named it after her granddaughter.

The chapel is an experience important to Broadmoor owner Anschutz, because, as his favorite cowboy poem says, the Broadmoor is out West, “where there’s more of singing and less of sighing, where there’s more of giving and less of buying.”

Anschutz is a Presbyterian, a form of Christianity that, among other things, promotes orderliness. He asked a local friend

in the faith to relaunch chapel services in 2012. Anschutz bought the red hymnals to place in the pews. The friend created an orderly 30-minute service.

The chapel marked the 10th anniversary of its reopening last June. Hotel guests and locals alike joined in singing from the Anschutz hymnals and then warmly greeted each other on the green, green grass of its precisely trimmed lawn.

e Wild West is alive and well in Colorado Springs and the Pikes Peak Region. From gold mining to cowboy potlucks and historic trains, the area is rich in western heritage. Strap on your boots for a western adventure that will transport you back to centuries past. learn more at VisitCOS.com/heritage

Avalanche chute bisects a tiny, resilient mining town

IN THE TOWN of Ophir, 13 miles south of Telluride in the San Juan Mountains, one will see fences made of skis, wooden houses equipped with prayer flags and hand-painted signs smattered with children’s handprints urging visitors to drive slowly.

Established as a mining town in 1881, the town is split into East and West Ophir. The two halves are separated by a blank strip of land perhaps half a mile wide. This stretch is deliberately left empty because that’s where avalanches come down in the winter.

No one is allowed to build in the empty land, and the avalanches sometimes close off the whole town for days on end. In these cases, the truly dedicated might cross-coun-

try ski their way out of the valley. Locals in years past dubbed the town “Oh-Fear.”

But people still live here; in fact, Ophir is purely neighborhood, encompassing around 50 houses, 180 humans, 51 dogs and a few local legends such as Scott Smith – born in 1957 and raised with his two brothers as mountain boys in “Appalachia Ophir.”

“The people in Ophir are a different breed,” Smith said. “We always were.”

He and his brothers covered every inch of the Ophir Valley growing up and saw countless avalanches of all different sizes and locations.

“We would be outside playing and hear this noise, and once you hear it once or twice you have no doubt what it is – it

sounds like a freight train as it comes down the mountain,” Smith said. “You’d turn around and look up and one of the chutes would be coming loose.”

If you’re indoors, you often don’t hear the avalanches; if you do, that means you’ve built your house too close to the avalanche chute.

But Ophirites are used to planning around extreme winter conditions: Some may leave vehicles on the other side of a normal avalanche path, and then walk, snowshoe or ski out if necessary. San Miguel County workers will also trigger avalanches before they get too loaded up. People in Ophir will sit on their porches with their cameras and phones ready to capture the slide.

Smith described one historic spring slide, the one of ’56, as told to him by an Ophirite neighbor who recently died at age 92. Winter avalanches, he says, are just fast, often descending at speeds of 200 mph. But spring slides move more like lava flows, with tremendous force and tons of water, and can snake around instead of being pulled straight down by gravity.

“At that time, there was a mercantile at the east end of West Ophir, and this slide came right down towards it,” Smith said. “It didn’t destroy the mercantile but pushed the whole building across the street towards the river, a good 100-150 yards down slope. There it sat until spring came, and the miners rediscovered it under the snow.”

Although that slide happened before Smith was born, he grew up around the miners and ranchers who used to populate the Ophir Valley until the early ’80s.

“Those miners kissed their spouses goodbye and went into their little ant holes, working in really dangerous conditions hundreds or thousands of feet under the ground,” Smith said.

The miners forged a sort of brotherhood with each other while working together underground.

“Forevermore, they had this bond that they all shared, and if someone got hurt or maimed or killed, the rest of the community would marshal together and make sure that person’s family was taken care of,” Smith said. “It was a beautiful thing to see during childhood.”