MAY/JUNE 2022

MAY/JUNE 2022

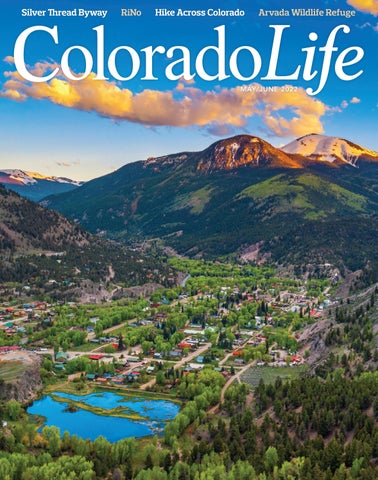

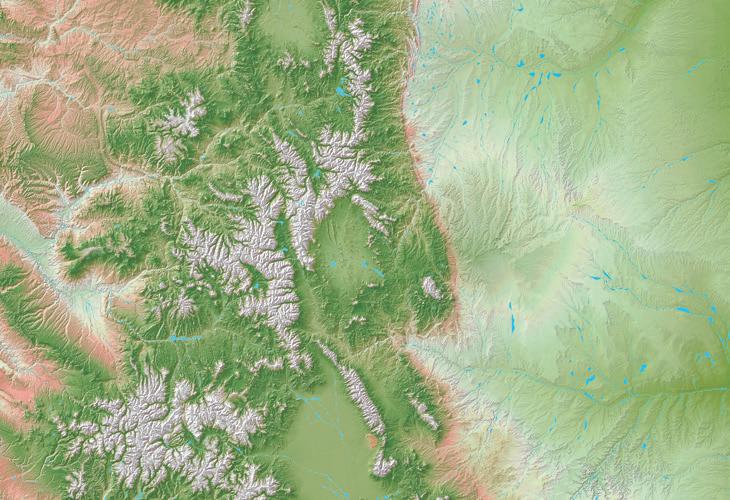

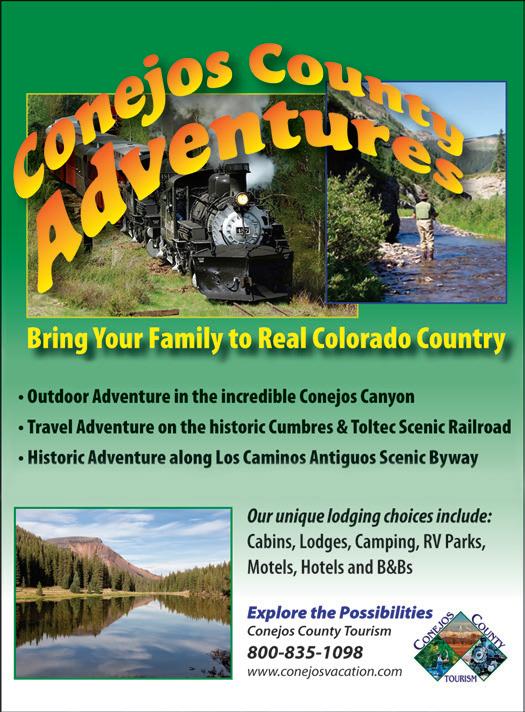

A scenic and historic route travels through the eastern San Juan Mountains on a road trip that makes stops at waterfalls, mining boomtowns and some truly spectacular mountain vistas.

Story and photographs by Joshua Hardin

One of the United States’ smallest national wildlife refuges sits in the middle of Arvada, where it provides habitat to birds and other native species, thanks to the citizens who banded together to preserve it.

Story and photographs by Dawn Wilson

A Boulder woman sets off on an extraordinary journey to traverse Colorado diagonally, hiking from the southeast corner to the northwest corner.

By India H. Wood

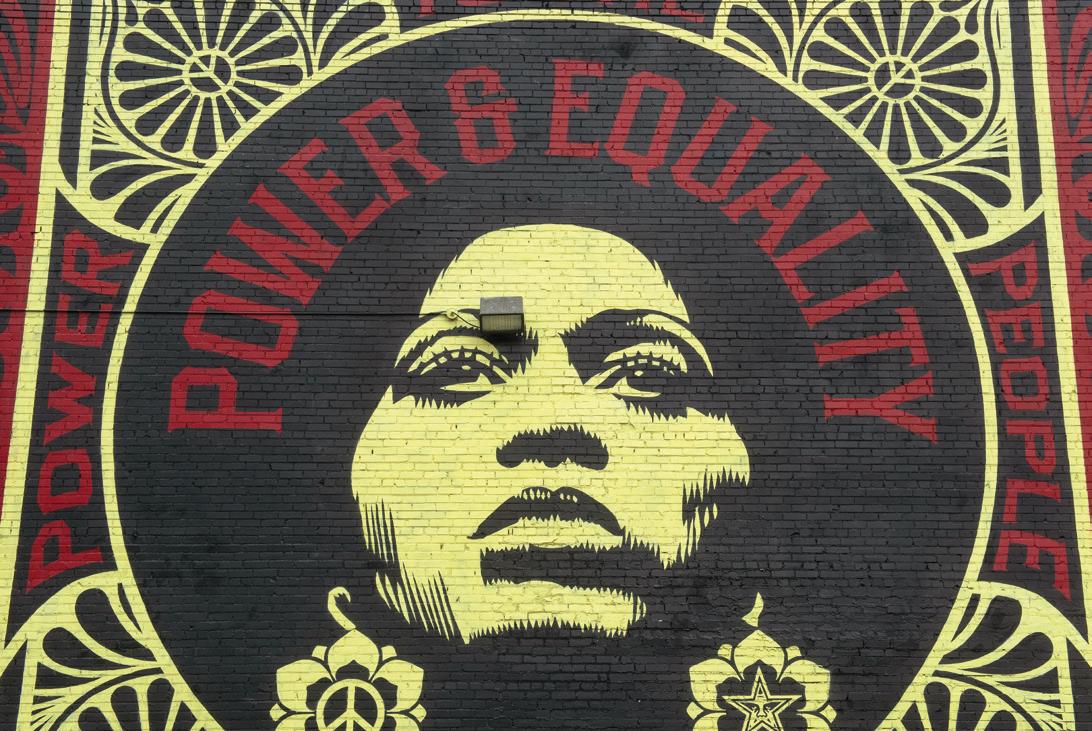

Originally known as the River North Art District, this Denver neighborhood strives to bring art into everyday life while undergoing constant change.

Story by Leah M. Charney

Photographs by Joshua Hardin

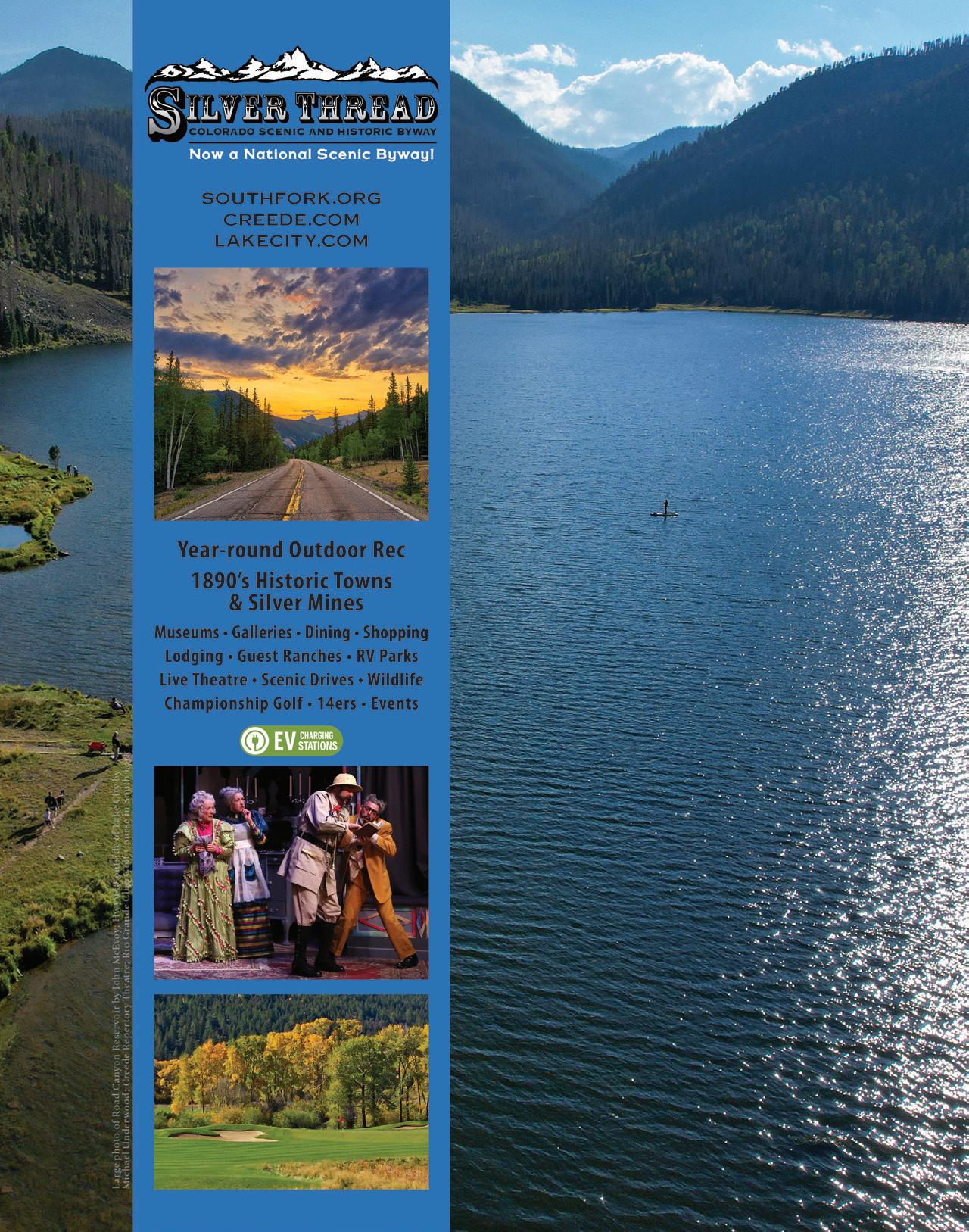

ON THE COVER

Red Mountain glows in the sunset as it rises above Lake City on the Silver Thread Byway. Story on p 22.

PHOTOGRAPH BY MICHAEL UNDERWOOD

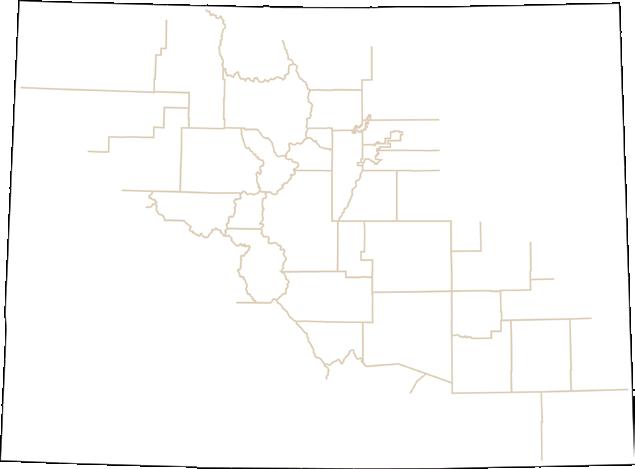

Northwest Corner 44

Maybell p 44

Craig p 44, 61

Meeker p 44

Longmont p 16

Arvada p 30

Frisco p 62

Conifer p 67

Florissant p 44

Crawford p 14

Lake City p 22

Creede p 22

Silverton p 70

Museum celebrates Pikes Peak Hill Climb; Littleton artist creates miniature worlds; Crawford general store is so much more; Longmont novelist pens High Plains mystery.

Test

Flank

byways.

41

Denver p 52

Littleton p 13

Colorado Springs p 12, 44

Pueblo p 44

Westcliffe p 60

South Fork p 22

La Junta p 44

Southeast Corner 44

As a time of rebirth and rejuvenation arrives across the land, our Colorado poets reflect with poems about blossoming.

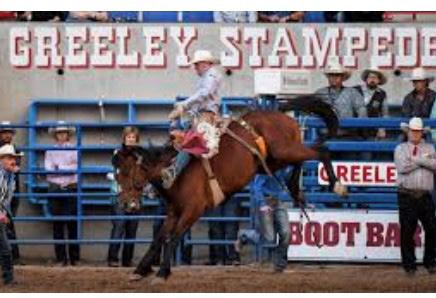

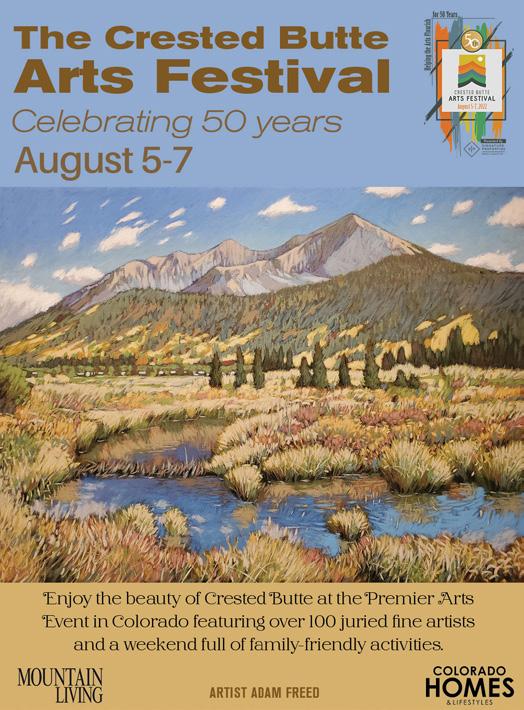

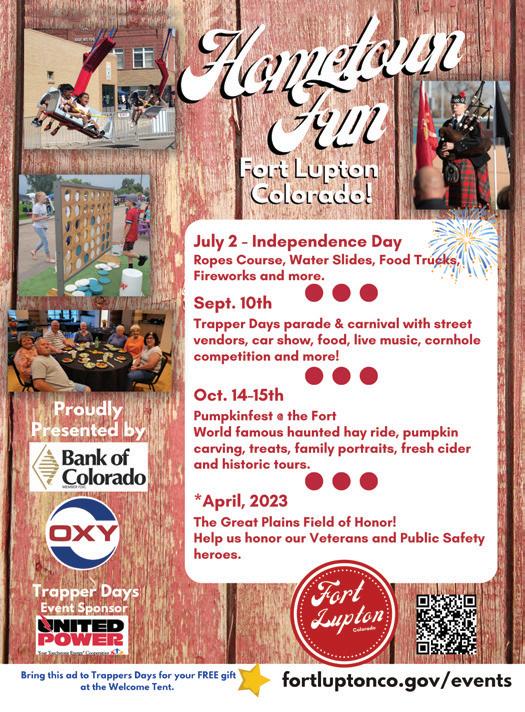

60 Go. See. Do.

Our statewide roundup of the best local festivals, events and daytrip ideas to check out for fun early summer adventures from all parts of the state.

67

Staunton State Park west of Conifer is a walk-in wonder, where campers hike to sites to camp beneath the trees.

70 Top Take

In our editors’ choice photo, hikers take an expedition to a meadow full of vibrant wildflowers beside a mountain lake.

Volume 11, Number 3

Publisher & Executive Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Editor

Matt Masich

Photo Editor

Joshua Hardin

Design

Open Look Creative Team, Valerie Mosley

Advertising Sales

Marilyn Koponen

Subscriptions

Meagan Peil, Lindsey Schaecher, Janice Sudbeck, Teresa Eichenbrenner

Colorado Life Magazine PO Box 430 • Timnath, CO 80547 (970) 480-0148 ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $25 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $44. Please call, visit ColoradoLifeMag.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and corporate rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, visiting ColoradoLifeMag.com or emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2022 by Flagship Publishing Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

ONE OF THE most important parts of my job description as editor of Colorado Life is also one of the simplest: “Know a lot about Colorado.”

Though I thought I already knew a lot when I joined the magazine in 2012, I have spent the past decade learning so much more – and the more I learn, the more I realize how much I still have to learn.

I’ve read a lot about Colorado in my quest for knowledge, but I’ve found that the best way, by far, to know the state is to visit as much of it as possible.

At first, I thought about trying to travel to every single place in Colorado, but I realized that would take me quite a while. Until I could accomplish that dream goal, I decided to get a feel for the breadth of the state by visiting all four of Colorado’s corners. I did just that a few years back, writing about my adventures in the May/June 2018 story “Colorado, Corner to Corner.”

I confess that I felt pretty pleased with myself for driving to the corners of the state. And then I heard about India H. Wood, the Boulder woman who in 2020 walked across Colorado in a diagonal line from the southeast corner in Baca County to the northwest corner in Moffat County.

Perhaps I was a little jealous I hadn’t thought to do what India did, though I readily admit I’d never have the wherewithal to attempt such a thing. I knew we had to have her tell her story in Colorado Life – and she does just that in this issue’s pg. 44 story “Going Diagonal.”

People have walked across Colorado – or most of it – before, but usually it’s on an established route like the Colorado Trail. India had to make up her own trail. The notion of doing such a thing seemed at once outlandish and completely understandable to me. I asked India what motivated her.

“It was born out of a love of the state,” she said. “I wanted to see the state as it is, without just picking the pretty spots or the tourist spots. The best way to do that is to pick a straight line across the state and walk it.”

She could have taken a straight east-west line and had an easier time of it, as there are many more roads that go that direction. She chose to go diagonally “in the spirit of ignoring the boundaries, ignoring the way you’re supposed to do things.”

For instance, conventional wisdom says that someone who lives in Boulder is “supposed to” hang out with Boulder people and do Boulder things. But if she were to confine herself to that, she would never have met people like Kletis Kelly, the rancher she befriended on the southeast Plains who became a sort of mentor to her on her journey.

By the end of her 730-mile trek, India had made friends with so many people from all walks of life whom she never would have met had she not decided to break out of the confines of her normal routine.

I don’t imagine many Colorado Life readers will be attempting to replicate India’s cross-Colorado expedition anytime soon. However, I do hope this magazine can inspire you to travel beyond the bounds of your daily commute and see just how wide and wonderful a place Colorado truly is.

Matt Masich Editor editor@coloradolifemag.com

Here’s to 10 more

Congratulations on your 10-year anniversary. No easy task in this age of iPhones and instant news feeds. Throw in a pandemic and all the uncertainties of the world today, and you’ve got the perfect recipe for creativity.

The world is still a beautiful place, nature is still thriving and there’s nothing better than holding a magazine in your hands that is filled with beautiful images and captivating stories. The Colorado Life story is one of inspiration and perseverance, creativity and teamwork. I look forward to the next 10 years.

Robert Basinger Rifle

My husband and I are octogenarians (that means OLD) and are homebound from making trips in our beautiful state. We anxiously await the arrival of Colorado Life for our next virtual trip. We sit and read it together and love the spectacular photographs and stories about Colorado.

My husband especially enjoys answering the trivia questions, as he is a native Coloradan. I enjoy the recipes a lot. In our 60-plus years of working in Colorado, we have lived and traveled from the north, south, east and west boundaries of Colorado, but Colorado Life always surprises us by taking us to places we have missed.

Like many of your readers, we thoroughly enjoyed the history story “John C. Fremont’s Frozen Fourth Expedition” in the November/December 2021 issue. In the March/April 2022 issue’s “10 Years of Colorado Life” story, I was pleasantly surprised to see the photo of Editor Matt Masich and his daughter in at the marker where Colorado, Wyoming and Utah meet. I didn’t know there was a marker.

We love our “Colorful Colorado.” We plan to keep Colorado Life coming to our home and making us so happy.

Jackie Eurich Fort Morgan

Seeing the Cash Register go up I have lived in Colorado for the past 42 years. I love our state and its natural and

beautiful scenery. The article “10 Years of Colorado Life” in the March/April 2022 issue is most inspiring and brought back such wonderful memories of the years past. The “Architectural Gems” section is very near and dear to my heart, as I saw the Cash Register Building being built from the nearby office at United Bank of Denver, my employer in the early ’80s.

Stepan

Ghadaifchian Denver

Afternoon tea on the menu

As a Coloradan of 23 years, I like to think I know Colorado pretty well. However, it seems I learn something new with each issue. After reading “Glen Eyrie” in the March/April 2022 issue, I feel a visit is definitely in order. It is one of the few places in Colorado Springs that I’ve yet to explore. It looks like a fabulous place to enjoy afternoon tea. We’ve added it and Pleasant Valley Schoolhouse No. 7 to our summer travel list (“Pleasant Valley Past Comes Alive in One Room”).

I thoroughly enjoyed reading “10 Years of Colorado Life,” complete with articles from issues over the past 10 years. This highlighted what I’ve missed out on by not subscribing sooner. Congratulations on reaching your 10-year milestone.

As avid campers, no issue is complete for us without “Colorado Camping.” We’ve been to Cherry Creek State Park for a birthday celebration but have not yet had the opportunity to camp there. Yet another item to add to our Colorado travel list. There is so much beauty here in Colorado

to discover. Thanks for helping us explore this magnificent state.

Tina Dzikowski Cañon City

Heartfelt birthday wishes

The photos and stories in every issue of Colorado Life are top notch, and I read each issue cover to cover as soon as the new one arrives. This magazine has inspired more road trips than I could ever imagine – so many cool places off the beaten path.

The March/April 2022 issue was exceptional for the trip down memory lane, but I really want to compliment Editor Matt Masich for his “Happy Birthday to Us” column. It was so heartfelt and well-written, and the comparison with Charlie at 5 feet and the magazine at 11 inches made me laugh.

Mary Beth Carpenter Conifer

Cover bird’s a stunner

“Wow” is all I can say about the cover on your March/April 2022 issue featuring Dan Walters’ duck photo. I look forward to receiving every issue of Colorado Life with its incredible photography. My husband and I are both amateur photographers who have been to Colorado to photograph the gorgeous landscapes, so we always spend time studying the photographs in each issue. And as someone who hopes to live there someday, I take great pleasure in reading the broad range of stories about what Colorado has to offer.

Julie A. Murray

New Philadelphia, Ohio

Sharing the joy

My husband and I subscribed to Colorado Life when you were giving away copies at a VFW meeting in Grand Junction. It looked like a good magazine to have, as we both volunteered at the Colorado Welcome Center in Lamar. We read each issue and then passed it along to travelers who stopped at the center for information about things to see and do in Colorado. Colorado Life never fails to have information about some thing or place that helps me advise a traveler.

In the March/April 2022 issue, the article about the Pleasant Valley school reminded me that we have a one-room school near Lamar that might be of interest to a teacher. The “More than Mallards” article inspired me to tell travelers about the Great Plains Reservoirs and the snow geese that navigate through the valley every year.

The short summaries of stories from the last 10 years brought back memories of the times we visited those places and how much we enjoyed seeing them based on your recommendations. I’ve still not visited Glen Eyrie, but that’s on my to-do list for this summer. Every issue is a treasure, and it’s hard to part with a copy. But the joy it brings when an issue is handed to a tourist makes the loss worth it.

Kaye Hainer Colorado Welcome Center Lamar

Greetings from Alaska

Fantastic wood duck photo on the cover of your March/April 2022 issue. I have a vacation home in Estes Park that I have elected not to visit since the pandemic. Your magazine keeps me in touch with “Colorful Colorado.”

The photography is gorgeous, and the statewide articles have alerted me to several sites I plan to visit when COVID becomes manageable and I return to Colorado. I enjoy summers in Alaska from the cockpit of my floatplane, but hopefully I will be able to visit Estes Park for the holiday season this year. I pass your magazines on to local friends who enjoy the articles during the long, dark winter months of Alaska.

Lee Beauman Palmer, Alaska

Thank you, Colorado Life, for your beautiful cover with the wood duck and the article about our indigenous ducks. As an avid birder, I will pull off the road at any water source just to check for migratory waterfowl. Hopefully your article will inspire other people to engage in the fun and rewarding hobby of birdwatching.

Kem Winternitz Colorado Springs

I really enjoyed the March/April 2022 edition of Colorado Life. Who would have thought there would be 20 or more breeds of ducks in this area? The photography in Colorado Life is outstanding. Since I’ve only been receiving the magazine about two years, I enjoyed reading what you’ve covered all 10 years.

Reading Colorado Life makes me want to travel this state and experience all the interesting places I’ve learned about. I especially like that you tell us where to stay and suggest places to eat when we go to the sights you recommend.

June Tate Loveland

US YOUR LETTERS

We can’t wait to receive more correspondence from our readers! Send us your letters and emails by June 1, 2022, to be published in the July/August 2022 issue. One lucky reader selected at random will receive a free 1-year subscription renewal. This issue’s winner is Mary Beth Carpenter of Conifer. Email editor@coloradolifemag.com or write by mail to PO Box 430, Timnath, CO 80547. Thanks for reading and subscribing!

or share with friends and family.

keepsake issue (6 per year) is filled with entertaining stories and beautiful photography about

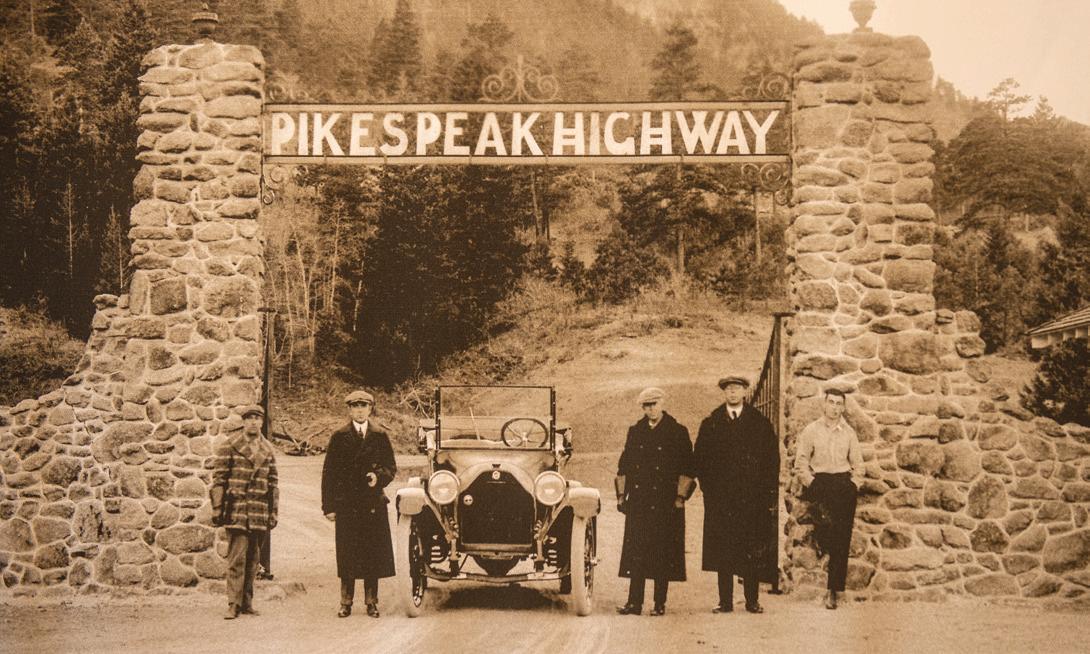

by TOM HESS

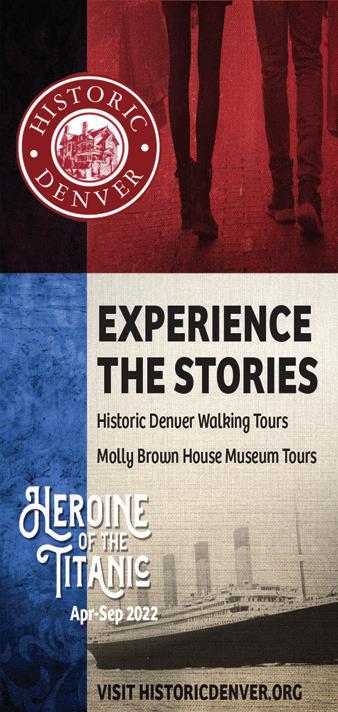

Toward the rocky top of the Pikes Peak Highway, drivers’ slightest errors can send their race cars over the edge and tumbling down a killer ravine, especially when snow and sleet slicken the heaving asphalt.

This is the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, one of the nation’s longest-running races, and among the world’s most dangerous. It is holding its 100th running this year; among major American auto races, only the Indianapolis 500 predates it.

There is no stadium seating for the Hill Climb. Instead, spectators buy tickets that allow them to gather along the 12-mile raceway, sometimes just several feet away from the zooming cars. Folks without a ticket can get a taste of what

the race is all about in the Penrose Heritage Museum’s Hill Climb Experience in Colorado Springs.

The museum is dedicated to Spencer Penrose, the man who started the Hill Climb. Penrose led a busy life – his other projects included building the Broadmoor Hotel, the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo and the Will Rogers Shrine of the Sun, all created to draw national attention to the city and mountains he loved.

The museum’s Hill Climb Experience begins with a ramp as steep as the Hill Climb itself. A number of cars that raced in the Hill Climb are on display. Most look like one would expect race cars to look, but there is one that seems out of place – it is the product of an amateur’s garage, a Frankenstein

assembly of spare Ford Model T parts. To everyone’s surprise in 1922, the ragtag “Old Liz” that cost $50 to build beat all the well-heeled manufacturers of the era: Chevrolet, Essex, Hudson, Mercer, Packard and Lexington.

Some cars that enter the Hill Climb make it into the history books without making it all the way up the hill. In the 2012 race, a Mitsubishi Evolution sailed over the left-hand turn of Devil’s Playground near the summit, flipped 14 times down a ravine and broke into a hundred pieces before its shattered remains finally came to a steaming, smoking rest.

The driver and navigator said afterward they thought they would die, but their safety cage held strong. The mangled car appears vertically, nose down, in its own display in the museum’s Hill Climb Experience wing, as if it’s eternally flying off course. That’s how the drivers described their fall – their brief moment of airtime after leaving the raceway “felt like an eternity.”

These are just a few of the stories that the museum tells, allowing visitors without a roadside ticket to experience the Hill Climb for themselves.

Cars that actually participated in the race appear in the Penrose Heritage Museum’s Hill Climb Experience exhibit.

tells stories by creating miniature Colorado scenes illuminated with LED lights inside old televisions, clocks, radios and more.

by LEAH M. CHARNEY

Stars twinkle, and the moon shines brightly. A campfire flickers next to a classic car pulling a silver trailer. It’s not a scene from a movie but intricate art placed inside the bronze body of a former clock by artist Scott Hildebrandt of Littleton.

Each Hildebrandt piece is a tiny treasure, with miniatures and electronics encapsulated in a vintage vessel. He mixes models, old toys, LED lights and motors to make interactive story art that comes alive with the flick of a switch. In Hildebrandt’s hands, the window of an early-1980s Walkman becomes a record store, complete with a flashing sign and a dog peeking in the windows.

For Denver-based arts education nonprofit CherryArts, he created a commissioned artwork called “Sound of Music,” which travels to schools in a mobile art gallery. The scene invites viewers to jump straight from a city into the wild. Watching deer serenely drinking from a stream, ensconced safely in a beat-up violin case, it isn’t hard to imagine the musical notes of nature – the rushing stream, the chirping birds, the rustling of wind through evergreens.

One thing that doesn’t appear in a Hildebrandt creation is people. Works often contain animals, like an alley cat perched on a trashcan, but the closest thing to a humanoid is a Sasquatch. “I like to create a scene where you can imagine yourself there,” Hildebrandt said, like the recent piece that included a bear sitting fireside to evoke a feeling that “everybody else has gone to bed, and the bear’s out there stargazing.”

His largest creation to date is at Meow Wolf Denver, which features 200 of his dioramas encased in radios and even tube televisions cut in half.

Hildebrandt sells his art at annual juried events, such as the Cherry Creek Arts Festival. He also posts to his Instagram page under the handle @misterchristmas, preferring to keep a personal connection with the people who enjoy or want to purchase his work. He’ll soon be moving into public art as well, creating 10-12 hidden dioramas to be placed along Denver’s South Pearl Street historic shopping district. His dream is to build a fully immersive experience: “I want to create a destination, like an old ice cream shop.” In Hildebrandt’s mind, even the site would be unexpected, like a run-down strip mall or a building in the middle of nowhere. The location would be critical to the art, as it would help determine which animals end up making a cameo in his work.

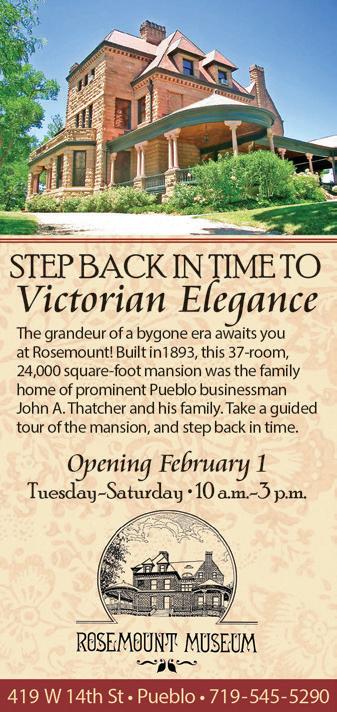

by LISA TRUESDALE

Try as she might, Cherri Olson just couldn’t convince her husband, Dale, to retire to her native Colorado. Then they visited their son in his new hometown of Grand Junction, and Dale fell in love with the Western Slope. They took the plunge, relocating from Florida.

A traditional, low-key retirement life was the goal, but Dale just couldn’t sit still. Perusing the High Country Shopper, he came upon a motel for sale in the small Delta County town of Crawford. He presented Cherri with his idea to buy the business using the magic words he knew would convince her: “But honey, it’s got a hardware store!”

She’d worked in hardware; she loves hardware. That’s all it took. But this business in Crawford also came with a few other responsibilities. It’s also a feed store, a laundromat, public showers – and a 10room hotel.

Cherri and Dale assumed ownership of the Hitching Post Hotel three years ago. “We found this place, and that was it,” Cherri said. “It was home now.” The couple lives in a two-story apartment in the huge building that also houses all their businesses. Together, they do all the managing, reservations, cleaning, maintenance, inventory, purchasing and selling, with the help of their impressive staff of … one.

It’s a rustic-looking building of dark wood, stone and metal, complete with a wagon-wheel railing. Cherri calls the hotel rooms “simple,” but that’s how she prefers it. “We keep it very clean,” she said, “but there are no bells and whistles.”

Except maybe on the shelves in the hardware/feed store. With 6,000 square feet of retail space, it’s got a little of everything. It’s an outpost for adventurers passing through (or resting for the night) on their way to explore the Black Canyon of the Gunnison via the less-traveled north

rim. It’s also a necessity for the 400 or so people who live in and around Crawford, as there’s no comparable store for at least 15 miles. The laundry facilities and showers are equally invaluable for travelers and for area residents who live off-grid.

They don’t serve food, except for a small assortment of chips and candy bars and a cooler of drinks. Instead, they point hungry travelers to the coffee shop across the road.

Also across the road is Crawford’s most famous resident – the late rock singer Joe Cocker, who lived on an area ranch with his wife, Pam, until his death in 2014. If folks ask about Cocker, Cherri directs them to his grave in the town cemetery just across D Street.

“The first time Dale visited the cemetery, he saw that someone had left flowers on his headstone,” she said. “And by flowers, I mean a big bud of pot.”

The store has posted hours, but Cherri and Dale don’t hesitate to open after hours

Cherri Olson owns the Hitching Post with her husband, Dale. They do all the work with the help of one employee.

if there’s an emergency, such as a rancher in urgent need of irrigation parts or fencing. That means they basically work 24/7, but they don’t mind, even though they’re supposed to be retired.

“Instead of retiring, we bought our retirement,” Cherri said. “Every day is memorable, and we have no regrets. It’s a joy to live here.”

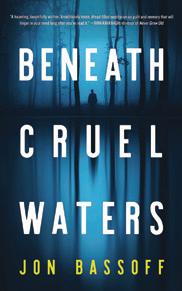

by LISA TRUESDALE

A single loose floorboard. Most people wouldn’t notice, but Holt Davidson does. He just has a feeling – or a repressed memory – that something’s hidden there. He hesitates. Should he be rifling through his mother’s personal stuff, even though she’s gone forever? He finally pulls on the board, straining, until it pops out. He sees what’s under there. He instantly regrets that he looked.

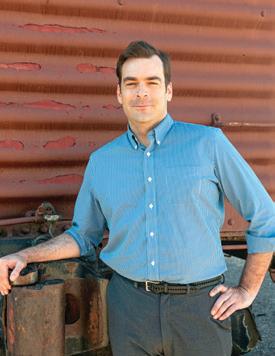

Though Holt’s hometown of Thompsonville in the new novel Beneath Cruel Waters is a fictionalized one, readers might recognize a few locations and street names in and around Longmont, where author Jon Bassoff lives.

“Sense of place is important for all of my books,” said Bassoff, who teaches high school English by day. “I don’t always start with the plot, or with the characters, but with the place.”

Yet he doesn’t really think his Thompsonville is like Longmont at all, unless you were to pick up the whole of Longmont as it was in the 1980s and transport it about 100 miles due east. That’s because, when he was writing this dark, disturbing psychological thriller –in a genre termed “gothic noir” – Bassoff was actually picturing eastern Colorado.

It was a series of images from Longmont-based photographer Jay Halsey, a friend of Bassoff’s, that inspired the book’s setting, and a number of key scenes. Halsey’s photographs, taken on the Eastern Plains, capture subjects like a rusty horse trailer, grain silos silhouetted against a cloudless sky and a dirt road that stretches for miles into the distance.

dead man under that floorboard, and while Bassoff was writing the gripping, traumatic climax, when Holt finally remembers everything.

“Jay’s photos really capture the mood,” Bassoff said. The photos were on Bassoff’s mind as he wrote about Holt discovering a gun, a love letter and a photo of a

This book’s sense of place might not be as strong as in Bassoff’s 2020 book The Lantern Man, set in Leadville and very place-specific regarding that town’s underground tunnels. Yet the setting is crucial to his latest story.

“Out east … it’s a landscape where the mountains seem a million miles away, and where you can go for miles without seeing anyone,” he said. “It’s a feeling my characters take on for themselves, as they’re trying so hard to leave the memories, but they’re being pulled back in and forced to face them.”

When the book was finished, Bassoff was inspired again, this time imagining “a multimedia explosion about eastern Colorado.”

On June 2 at 7 p.m., he’ll be reading passages from the book at the Left Hand Brewing Co. in Longmont, accompanied by a photo showcase from Halsey, music from Wendy Woo and an exhibit of artwork based on scenes from the book.

Experience historic charm at Frisco Lodge Our exceptiona l hospita lit y, ernoon w ine and cheese, awardw inning cour t yard and romantic outdoor replace are just a few reasons our g uests rated us t he #1 bed & brea k fast in Frisco and a ll of Summit Count y!

See why our guests think we are the best: http://bit ly/FriscoLodgeReviews

www friscolodge.com 1-970-668-0195

321 Main St | Frisco, CO

HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS

Test your knowledge of Colorado roads. by

BEN KITCHEN

1 Due to the distinctive straight-line shape it has on a map, the section of State Highway 119 connecting Boulder and Longmont has what nickname?

2

Although it’s now gone, a mile marker on Interstate 70 just outside of Stratton featured what unusual number in an attempt to deter theft? Your answer should be rounded to the nearest hundredth.

One of the most recent state byways to become a national scenic byway is the Silver Thread, which passes by Lake City as well as what nearby lake, the second-largest natural one in the state, that gives the city its name? GENERAL

3 The scenic and historic byway that runs along the Cache la Poudre River is named partly after the river itself and partly after what valley at its western terminus, which does not share its name with a longrunning TV show?

4

Some communities in northern Colorado have renamed sections of U.S. Highway 85 the WHAT Highway? Despite its name, the route passes through Littleton, not a different city south of Denver.

5

6 Which major Colorado interstate highway traverses the greatest distance within the state’s borders?

a. I-25

b. I-70

c. I-76

7 Which official state symbol appears on roadside signs in the logo for the state’s Scenic Byway system?

a. Colorado blue columbine

b. Colorado blue spruce

c. Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep

8

Starting in Golden, Colfax Avenue runs through the cities of Lakewood, Denver and Aurora, but it doesn’t stop there. It ends farther east in what town?

a. Watkins

b. Strasburg

c. Fort Morgan

9

As the name suggests, the Tracks Across Borders Byway goes across one of Colorado’s borders. Which neighboring state does it enter?

a. New Mexico

b. Utah

c. Wyoming

10

One of Colorado’s All-American Roads, Trail Ridge Road runs for 48 spectacular miles through which of the state’s four national parks?

a. Black Canyon of the Gunnison

b. Mesa Verde

c. Rocky Mountain

11

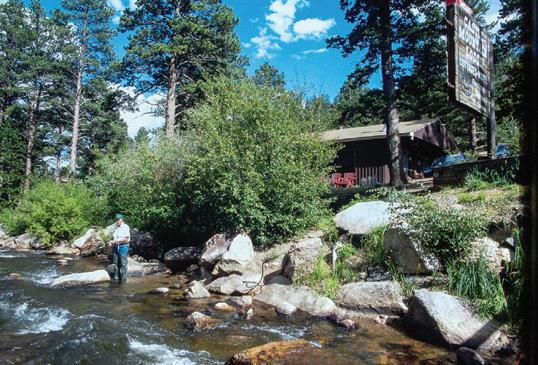

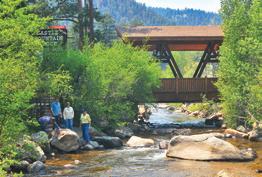

EXPERIENCE the splendor of the Rockies at Aspen Winds. The secluded setting along Fall River, among the aspen and pines, offers a relaxing atmosphere. Aspen Winds is located minutes from Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park. We offer one and two bedroom suites and in-room spa suites.

Top of the Rockies Scenic Byway is home to the highest paved road in the United States.

12 Grand Mesa Scenic Byway actually passes through the town of Mesa.

13

14

Colorado has more All-American Roads and National Scenic Byways than any other state, with a total of 13.

Seven-mile-long Interstate 270 is the shortest three-digit interstate in the country.

15 It is illegal for liquor stores and marijuana dispensaries to participate in the state’s Sponsor a Highway program.

No peeking, answers on page 68.

•

•

•

Scenic byway through San Juan Mountains offers legends, lore and stunning sights

story and photographs by

FEW PLACES IN Colorado have a starker difference between winter and summer than the eastern San Juan Mountains.

Winter in the San Juans is the stuff of legend, such as tales of prospecting parties getting stuck in winter storms and resorting to cannibalism. Such a thing hardly seems possible in summer, when travelers can easily drive wide-open roads under silvery green aspen leaves glittering in the breeze, with snow but a faint, shimmering accent lingering on only the highest peaks. Though the range has a reputation for inflicting hardship, this place couldn’t be more welcoming. Still, there are constant reminders of the region’s colorful, sometimes infamous past.

THE MAIN

through the eastern San Juans is the Silver Thread Scenic and Historic Byway, connecting four counties and three towns, including Lake City, Creede and South Fork. Appropriately named for the shiny element extracted by area fortune seekers for centuries, the 120-mile trip takes two to four hours, but more time should be given

for exploring elegantly restored Victorian architecture, beautiful natural landscapes and adventurous backroads.

From Gunnison, travelers drive west on U.S. Highway 50, following the Gunnison River to the shore of Blue Mesa Reservoir, where placid waters provide a prime location for boating, fishing and stand-up paddling. The byway begins at the junction with State Highway 149, veering southward along the river’s Lake Fork.

The road crosses verdant mountain meadows welcoming migratory birds. Beginning in 1985, Lake City resident Helmut Quiram built nesting boxes for bluebird habitat. Students from Western State Colorado University in Gunnison now maintain more than 600 boxes installed along this stretch, known as the Lake Fork Bluebird Trail.

The route climbs to Lake City, where the Hinsdale County Historical Society offers pub crawls with ghost stories and guided walking tours of preserved buildings from the 1870s. Much of the Victorian construction is now used for charming art galleries, many of which participate in the city’s Annual Arts and Crafts Festival

happening on July 19.

Modern motorists enjoy routes forged by wagon toll road builder Enos Hotchkiss, founder of Lake City in 1874, and his contractor, Otto Mears, known as the “Pathfinder of the San Juans.” Mears established Lake City’s first hotel and financed the first Western Slope newspaper, The Silver World, which is still in print. Lake City residents also developed a cultural center and one of the region’s first telephone systems, which connected mining towns with music concerts held over party lines.

However, 19th century Lake City was not completely civilized. Preachers nicknamed “sky pilots” proselytized on pulpits made from barroom tables. Legend has it, two prostitutes horse-whipped a minister when he refused to give a funeral for a fellow call girl. Other colorful characters frequenting the saloons included Alice Ivers, who made a career playing cards after her husband died in a mining accident. Nicknamed “Poker Alice Tubbs,” she sharpened her trade in Lake City before traveling nationwide to amass an estimated $250,000 in winnings – $3 million in today’s dollars.

“We were all gamblers,” Poker Alice said. “Some staked their claims in the mines. Others in cattle or goods. I simply staked my lot in cards.”

WHILE LAKE CITY has about 400 fulltime residents today, generations of summer visitors return to establishments like the Cannibal Grill and Packer Saloon, a restaurant playfully themed on both the Green Bay football team and notorious alleged maneater Alfred “Alferd” Packer.

Hinsdale County Historical Society is working to open tours of the Alferd Packer Massacre Site, 3 miles south, telling the story of how five prospectors hired Packer to guide them from Salt Lake City to the Los Pinos Agency, near present-day Gunnison. When Packer’s group departed in February 1874, Utes warned they would never make it through the mountains due to severe winter storms. Packer’s clients should have heeded the advice.

Packer stumbled into the Los Pinos Agency alone in April, suspiciously flush with cash and possessing a comrade’s

belongings. Packer claimed the party became lost in a storm and ran out of food. As each man died, the others ate the flesh of the dead to stay alive, and Packer was forced to kill the last surviving man in self-defense.

Accused of cannibalism and murder, Packer fled but was eventually captured and brought to trial in Lake City. Judge M.B. Gerry found Packer guilty of murder and allegedly sentenced him to hang for eating “five out the seven Democrats living in Hinsdale County.”

From the massacre site, the highway rises toward 11,530-foot Slumgullion Pass, named after slumgullion stew, a slimy, yellowish soup that sustained destitute miners still attempting to strike it rich. The north side of the pass has a 9 percent grade, the steepest of any paved Colorado road.

A massive landslide on these precipitous slopes called the Slumgullion Earthflow began about 850 years ago, when weak breccia rocks broke from Mesa Seco above. A second slide started about 300

years ago and is still active; unstable soils surrounding it move like molasses at a pace of 20 feet a year.

An overlook provides a view of the turquoise-colored Lake San Cristobal. The lake formed when the slides blocked the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River.

Lake City’s namesake takes its name from a Lord Tennyson poem describing a Scottish loch called Cristobal, and it and looks as idyllic as the poet likely envisioned. Fully grown conifer trees angled steeply along the lakeshore show the only evidence that the sluggish slide is still at work.

Ahead are more equally impressive pullouts. The Windy Point Overlook showcases two 14ers: Wetterhorn Peak, resembling Switzerland’s famous Matterhorn, and the tilted triangular form of Mount Uncompahgre, resembling a witch’s hat. Drivers navigate through fields of fireweed carpeting the landscape with a vivid pink hue while eclipsing a second summit, Spring Creek Pass on the Continental Divide.

North Clear Creek Falls plunges 100 feet down from a willow-covered bench into a steep box canyon about half a mile off the byway.

ONE OF COLORADO’S most spectacular waterfalls lies along an easterly diversion on Forest Road 510. The cascades of North Clear Creek Falls plummet clamorously 100 feet from a willow-covered bench into a steep box canyon appearing like a crater gouged from the lush rolling hills of the surrounding scene.

Photographers line tripod-mounted cameras along the guardrails of a parking area above for closeup views of rainbows that form inside the falls’ spraying mist. A roaring sound echoes from the ravine’s walls as runoff collides with colossal boulders at the falls’ base. South Clear Creek Falls, a second, less-visited waterfall, reached via a short trail from Silver Thread Campground farther along the byway, is like a miniature version of its big brother upriver.

Past the falls, volcanic andesite spires, including one named Bristol Head by a settler reminded of his English origin, are often shrouded by fog and monsoon rains as they tower over the byway. Nicholas Creede discovered precious metals in these mysterious hills and founded the namesake town in 1890. Within a year, the town of Creede’s population increased by 300 people daily and grew to more than 10,000, most with sights set on striking silver.

During Creede’s boom, con man Soapy Smith opened the Orleans Club gambling hall. Smith purchased and exhibited a supposed “petrified man” nicknamed McGinty for an admission of 10 cents, while running shell and three-card monte games to swindle more money from customers waiting in line for the sideshow. When the boom waned, Smith decamped to Denver with McGinty. Creede lost most of its business district, including the Orleans Club, in a fire soon after.

Out of the ashes came institutions like the Creede Repertory Theatre. In 1966, theater lover Jim Livingston mailed letters to universities nationwide, hoping someone would perform for visitors in Creede’s disused opera house. The sole reply came from Steve Grossman, a 19-year-old University of Kansas theater student, who convinced 12 students to sell $1 tickets, sew costumes, collect props, built sets and perform in the first season of shows.

The theater now celebrates its 57th season with five shows on two stages, improv events and workshops. Even if the setting seems little like Broadway, productions bring $4 million in economic impact to Colorado yearly.

A less conspicuous landmark, Creede’s Underground Mining Museum, exists in tunnels inside of a mountain. Providing a look at subterranean mining life, exhibits are viewable in half-hour, self-guided audio tours or occasional extended tours guided by retired miners.

“My aunt visited from Manhattan, New York, and said it was the best museum she’s ever seen,” said Kathleen Murphy, executive director of the Creede/Mineral County Chamber of Commerce. “And it’s not as claustrophobic as you would think.”

Like the boom days of old, Mineral County’s full-time population is about 800 today but can balloon to 12,000 in

summer when festivals occur.

The Taste of Creede kicks off on Memorial Day weekend with the Silver Chef cookoff, where participants compete using surprise ingredients and serve samples to all spectators. The festival, envisioned by renowned watercolorist and gallery owner Steven Quiller, also includes a “quick draw” competition. This is no standoff between gunslingers; rather, artists using a variety of mediums have 45 minutes to create a piece for auction.

Creede’s Independence Day Celebration starting on July 2 features ample live music, food and fireworks, but the biggest draws are the Colorado State Mining Competition and the Days of ’92, which involve arduous tests of miners’ strength.

“The mine bosses found if they had competitions above ground, it increased the miners’ skills underground,” Murphy said.

BEYOND CREEDE, THE BYWAY winds through a nature-lover’s paradise. Up to 1,000 elk gather in Coller State Wildlife Area during summer before migrating northeast in late fall. Bighorn sheep, as well as golden and bald eagles, are often seen along this stretch heading to the highway’s southeastern terminus and one of Colorado’s newest towns.

Incorporated in 1992, South Fork is named for a junction of the Rio Grande. Late 19th century sawmills sprung up to supply local Douglas fir and pine timber as ties for expanding railways and structural props for nearby mines. As the town

grew, residents demanded lumber and roof materials for their own houses, barns and businesses. A local mill employed 100 people in its heyday.

Though logging is no longer as widespread, “Biggin,” a 24-foot lumberjack sculpture carved from a single Douglas fir, beckons visitors to take a selfie beneath the town’s gargantuan roadside attraction. South Fork also celebrates its heritage with the Logger Days Festival, featuring chainsaw carving, ax throwing and other lumberjack competitions, held July 15-17.

A sparkling treasure of Colorado’s state byways, Silver Thread earned national sce-

nic byway designation last year. The lure of the flashy metal that attracted settlers to the San Juan Mountains may have subsided in recent times, but the opportunity for travelers to experience the region’s wild nature, rich history and lively activities will never tarnish.

The byway’s Windy Point Overlook provides travelers with the opportunity to stop for a spectacular view of a pair of 14ers, including witch’s hat-shaped Mount Uncompahgre, at far right.

Golf the award-winning course at the Rio Grande Club & Resort in South Fork, Colorado. The front nine play alongside the Rio Grande. The back nine o er a wild mountain adventure. Stay a little longer to enjoy our townhomes, restaurants, clubhouse and Gold-Medal fishing in private waters on the pristine Rio Grande. The surrounding area o

Two Ponds National Wildlife Refuge is a small but mighty natural enclave in the midst of the city

story and photographs by DAWN Y. WILSON

TRAVELING AT THE 40-mph speed limit on Kipling Street in Arvada, a car can drive completely past Two Ponds National Wildlife Refuge in exactly 17 seconds.

The refuge is easily missed – but shouldn’t be.

Two Ponds is a tiny island of wildlife habitat surrounded by a sea of houses, medical offices and a convenience store. It is a place where the sound of city streets fades into the background, overtaken by the call of songbirds.

At just 72 acres, it is far less than 1 percent the size of the metro area’s much better-known Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge. Yet despite its diminutive dimensions and location in the middle of suburbia, Two Ponds more than earns its place in the National Wildlife Refuge system. In a pocket-size area, the refuge packs in wetlands, wooded areas and prairie, providing a home to native animals. It freezes the land in time, taking visitors back to an era when this city was a wild place.

But none of this would be true if not for the timely intervention of a small crew of advocates.

BY THE TIME Arvada resident Bini

Abbott found Two Ponds, it was all but lost. In late 1990, Abbott brought her dog to Dr. Al Marshall’s veterinary clinic located near the intersection of West 80th Avenue and Kipling Street in Arvada, less than 10 miles from downtown Denver.

Like any other visit in the previous 20 years of taking her pets to his practice, she parked in the lot and walked her dog through the front door. The practice, called Arbor Acres, was a Tudor-style building flanked by bushes with leaves turning into vivid shades of warm autumn tones. The yellow marigolds in the front planter were still blooming. Traffic buzzed up and down the nearby roads that separated the clinic from the surrounding housing developments.

Abbott had visited this clinic and her veterinarian friend dozens of times but had not noticed the oasis that sat just behind the building.

“Come out and see what is happening out the back door,” Marshall told Abbott, knowing that she was a strong, outspoken supporter of preserving natural habitats. “I am about to lose it to developers.”

Abbott and Marshall navigated through the veterinary hospital, passing exam rooms, the surgical suite and the room that housed the hospitalized dogs and cats in a bank of cages before reaching the back door.

When Marshall opened the door for Abbott, she laid her eyes upon a little slice of nature straight out of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. This was Two Ponds.

A hint of moisture lingered in the cool air as Marshall and Abbott walked out into the wooded area. They navigated down a dirt path that cut through the trees and into a small open meadow. Willows and cattails surrounded a small pond at the edge of the meadow where surface fog rose from the water. A small flock of Canada geese honked loudly as they flew overhead.

Marshall and Abbott continued past the pond. As they walked, Abbott noticed a beautiful weeping willow tree on the northeastern edge.

“Twisty,” Abbott declared. “I shall call that tree Twisty for all its reaching branches.”

BY THE END of 1990, then-58-year-old Abbott was hard at work being the leading lady in a zoning melodrama, spreading the story about the pending destruction of this urban jewel.

“Bini came to one of the Urban Wildlife Photo Club meetings telling me she was

a terrible photographer and needed help on a project,” said Wendy Shattil, a conservation photographer based in Denver. “Bini’s words along with some photos had more power than anything else to show how important it was to save Two Ponds.”

Abbott went to numerous Arvada City Council meetings to talk about the benefits of saving Two Ponds. She wrote editorials to the Arvada Sentinel and Rocky Mountain News. She lobbied the Environmental Protection Agency and other government agencies, as well as state and U.S. legislators.

And the responses to her passionate outreach poured in to help the cause.

On Sept. 26, 1992, a group of dedicated community citizens led by Abbott were finally able to declare they won.

TODAY, THANKS TO grassroots citizen involvement, Two Ponds is now permanently protected as a national wildlife refuge. It is smaller than all but two dozen of the National Wildlife Refuge System’s more than 560 refuges. The City of Arvada has grown up around the refuge, but this land has been protected for all to enjoy.

Beyond the ponds, there is a marsh thick with cattails, rolling hills of former farmland that retains remnants of its historic high prairie landscape. From the top of the hills, sweeping, unobstructed views of the Front Range mountains stretch all the way to Longs Peak and beyond to the north. The western and southern edges of the property have groves of mature pines and cottonwoods.

There are also more than 9 acres of wetlands habitat ideal for foxes, raccoons, muskrats, a wide variety of migratory waterfowl and songbirds, great horned owls, snakes, mice, hawks, tiger salamanders, turtles and mule deer that reside in the safety of its cover.

One of the more impressive areas of the refuge is the west side, where maintained natural trails meander through rolling hills covered in short-grass and mixed-grass prairie plants. Especially pretty in late spring and early summer, visitors will also find an abundance of dragonflies, damselflies and butterflies across the hills and in the wetlands around the ponds. People keep an eye out for turtles and frogs near the ponds and use binoculars to scan the wetlands and wooded areas for nesting birds.

Two Ponds hosts hundreds of volunteers, partners with local schools and helps Boy and Girl Scouts achieve their badges.

“Two Ponds is a neighborhood treasure right out our back door,” said Jeff Sweetman, first grade teacher at Meiklejohn Elementary School in Arvada. The kids love the experience of looking at the wildlife in the ponds, woods and fields. They have the rare opportunity to explore a place in their neighborhood set aside to exist in its natural state.

More than 30 years after Abbott’s first view of Two Ponds out Marshall’s door, the veterinary practice and the willow named Twisty have fallen to the fate of time, but excitement still exists at what explorers of this urban oasis can see right out their back door.

Two Ponds National Wildlife Refuge celebrates its 30th anniversary on Sept. 26, 2022. Visit fws.gov/refuge/two_ponds to learn more about visiting Two Ponds, including information on seasonal closures and community programs.

recipes and photographs by DANELLE McCOLLUM

GRILLS FIRE UP as warm weather returns to Colorado. When it comes to grilling beef, perhaps the most versatile cut is flank steak. As these recipes demonstrate, flank steak does just as well in Greek-style gyros, Mexican-style tacos and an all-American dish with Buffalo sauce and blue cheese. The meat is most tender when marinated and cut against the grain into thin strips.

This spin on the classic gyros sandwich uses flank steak instead of lamb for an easy, make-at-home version of the Greek favorite. The tzatziki sauce adds the perfect amount of flavor and moisture.

Place flank steak in large resealable bag or shallow pan. Combine olive oil, garlic, oregano, salt, pepper and juice of half lemon and pour over steak. Cover or seal and refrigerate up to 8 hours.

To make tzatziki sauce, place cucumber and salt in food processor and pulse until cucumber is finely chopped. Add remaining ingredients and pulse until sauce reaches desired consistency. Cover and refrigerate until ready to use. Remove steak from refrigerator 1 hour before grilling to allow to come to room temperature. Heat grill or grill pan to medium-high. Remove steak from marinade and transfer to grill; cook 6-8 minutes per side, or until steak reaches desired doneness. Transfer steak to cutting board and let rest 5 minutes.

Slice thinly against the grain. Serve steak in flatbread or pita bread with onion, tomatoes, lettuce, feta cheese and tzatziki sauce.

Steak Gyros

1 ½ lbs flank steak

1/3 cup olive oil

3-4 cloves garlic, minced

2 tsp dried oregano

1 tsp salt

1/4 tsp pepper

Juice of 1/2 lemon, plus additional wedges for squeezing

1/3 red onion, thinly sliced

1-2 tomatoes, sliced

Chopped romaine lettuce

Flatbread or pita bread

Crumbled feta cheese

Tzatziki sauce

Tzatziki Sauce

1/2 cup seeded, chopped cucumber

1 tsp salt

1 cup plain yogurt

1/4 cup sour cream

1 Tbsp lemon juice

1/2 Tbsp rice vinegar

1 tsp olive oil

1 clove garlic, minced

1 Tbsp chopped fresh dill 1/2 tsp Greek seasoning

Salt and pepper, to taste

Serves 4-6

Traditionally made with skirt steak, these tacos swap in the tenderer flank steak. The beef is seasoned to perfection, grilled and loaded into tortillas along with crema and your favorite taco toppings in this super simple but satisfying meal.

To make crema, whisk together all crema ingredients in small bowl. Refrigerate until serving.

On large baking sheet, drizzle steak with olive oil, turning to coat evenly. Steak can be cut into 10- to 12-inch-long sections, if needed. Season with Montreal steak seasoning, salt and pepper.

Heat grill to medium high. Place steak on grill and cook 4-6 minutes per side for medium-rare. Remove from grill and slice steak into thin strips. Serve in warm tortillas with Mexican crema and your favorite taco toppings.

Tacos

2-3 lbs flank steak

2 Tbsp olive oil

1 tsp Montreal steak seasoning

Salt and pepper, to taste

Small flour or corn tortillas

Pico de gallo, salsa, sour cream, lime wedges, chopped cilantro or other favorite taco toppings

Crema

1/2 cup sour cream

1/4 cup heavy cream

1 Tbsp adobo sauce from canned chipotle peppers

1-2

Tbsp lime juice

Salt and pepper, to taste

Serves 4-6

Buffalo sauce usually goes hand in hand with chicken wings, but to taste this marinated flank steak topped with Buffalo blue cheese butter is to know that its spicy, tangy flavor goes just as well with beef. Corn on the cob makes a great side dish, especially with a little Buffalo blue cheese butter added.

Score flank steak on both sides; set aside. In small bowl, whisk together soy sauce, oil, ketchup, garlic, oregano, pepper and onion. Place steak in large resealable bag or shallow baking dish. Pour soy sauce mixture over top. Cover or seal and refrigerate for at least 8 hours, or overnight.

Remove steak from refrigerator 1 hour before grilling to allow to come to room temperature. Heat grill to medium-high. Remove steak from marinade and grill for 3-4 minutes per side for medium rare. Transfer to cutting board and let rest 5 minutes. Meanwhile, combine ingredients for Buffalo blue cheese butter in small bowl. Mix well. Thinly slice flank steak and top with Buffalo blue cheese butter.

Grilled Flank Steak

2-3 lbs flank steak

1/2 cup soy sauce

2 Tbsp olive or vegetable oil

2 Tbsp ketchup

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 tsp dried oregano

1 tsp pepper

1/4 cup onion, finely chopped

Buffalo Blue Cheese Butter

1/2 cup butter, room temperature

2 Tbsp Buffalo hot sauce

Pinch of cayenne pepper

1/4 cup crumbled blue cheese Salt and pepper, to taste

Serves 4-6

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag.com or mail to Colorado Life, PO Box 146, Timnath, CO 80547.

Colorado blooms back to life as spring returns to mountains and plains. This brief window of blossoming renewal prompts our poets to reflect on this special season in the circle of life. In these contemplative poems, a flower is seldom simply a flower.

Nancy

Dalton, Fort Collins

Outside my window the nexus of winter to spring has begun, not uneventfully, I note. Winter’s exit, new beginnings follow in sequence. The stark, bony architecture of winter now disappears, into softened, gently formed spring.

It begins not unlike the new birth. The bud sets warmed by the sun burst open with life again. Sunlight that poured through my window in winter, barely filters now through the canopy of green.

My bird feeder becomes a hub for new arrivals, all so different from the snowbirds of winter. They sweep the feeder clean and charm me with birdsong. I am awakened each morning by a symphonic nudge into the advent of a brand new day.

There is something in the waiting that seizes my soul. It’s about the attending, the moment before the first sprout of green appears, before the arrow releases, the line pulls, the head crowns. Therein lies the sanctity of new beginnings. It will come in the moment just before it all begins.

Dan Guenther, Morrison

Near that spot where the French trappers used to rendezvous along the Purgatoire River, you watch two archeologists pull prehistoric bison bones from a Paleolithic burial mound. Further up a dry, ephemeral channel, they hope to find additional, ancient human sign, while all around them the massed larkspur blooms as it has for centuries, a floral shroud over what still lies undisturbed, buried deep beneath the short-grass prairie.

Shannon E. Perry, Phoenix, Arizona

Lilacs at my grandmother’s door

The sweet aroma lingers still I remember the lovely color

Of blossoms nodding in the breeze

Today the lilacs of a neighbor

Unfold as the sun appears Florets of petals last a week or two

Until the wind blows them free Memories last but alas

No more sweet scent, no lilacs in bloom

Steven Wade Veatch, Grawn, Michigan

Purple pasque flowers

Open petals to the earth

It’s time to open

Ourselves to each other

While the spring breeze sings Its harmonies

To the waving grass

A bug sits on top of an unopened lupine bloom in a field of purple lupines in Evergreen. Southwest of Grand Lake, lupines blossom around an aspen trunk.

Cher Tom, Palisade

The folded pages of winter’s seed catalogs Whisk dreams of glossy leaves and bright flowers away. Sprinkling seeds over the rich earth, impatiently I watch for vibrant colors and butterfly nectar to emerge

The dirt is cold, still sticking to my bare toes

When I hurry out before morning’s sunrise And touch a small green shoot, bending Toward the bright light, hovering behind the mountain.

Hours and minutes tick by before the splendor erupts, Painting the garden with God-colors. Violets, blues, reds ... twine together like braided fingers. Morning glories have arrived.

Suzanne

Lee, Littleton

I know a woman set these plants, flowering now in the last days of summer, set them at the angles of her house to show this place was not a wilderness.

I can see the man climb up the hill, stop at the gate, put the groceries and the jar full of green stems and leaves on the porch to save steps, then drive off to the barn.

I watch the woman come out, glad of the spring sun, hoping it will heal the thickness in her lungs that makes her tired, almost too tired to stand, too tired to work for more than a few minutes at a time. She has been angry: angry that she is ill, and ashamed that she doesn’t get well.

She carries in a bag of flour, returns and sees the plant among the packages. She picks up the jar, and sits on the steps holding it against her like a child until she has caught her breath, takes it in and puts it on a window ledge. Later she asks the man. He smiles and says a friend sent it, grew it from a cutting. The woman smiles, too.

“A friendship plant,” she says.

Late in May she plants it outside using rotted manure and soft soil from the ravine. She brings water in the bucket every day. In August it blooms, a handful of tender whiteness on five dark stems, bright against the glossy leaves.

Friendship flowers, she thought then.

Each spring she added more, growing them from that first plant, until no matter which way you approached, you saw these white blooms.

DO YOU WRITE poems about Colorado? We’re looking for poems about “Colors” for September/October 2022, deadline July 1, and “Colorado Memories” for November/December 2022, deadline Sept. 1. Send your poems, including your mailing address, to poetry@coloradolifemag.com or to Colorado Life, PO Box 430, Timnath, CO 80547.

The house is gone; the path, without a trace.

Still, I hope she sees me standing here loving the flowers, harvesting her grace.

by INDIA H. WOOD

Boulder woman meets cowboys and butterflies on an epic hike from one corner of Colorado to the other

In 2020, India H. Wood of Boulder drew a diagonal line on a map from the state’s southeast corner to the northwest corner and set out on a 730-mile hike across Colorado. Her goal was to experience the breadth of people and places to be found in the state. She shares with Colorado Life some of the memorable encounters from her remarkable journey.

IPERCHED LIKE A ski racer on a manhole cover set in a dirt road. Dribbly iron welds spelled out “OKLA 1907/ KANS 1861/COLO 1876” – the years of statehood of the three states that meet at this point. I envisioned it also proclaiming INDIA 2020, the year of learning to stand on my own two feet and meeting the land and people along an arbitrary diagonal line across my home state. I began walking May 11.

“We feeling feisty and ready for fun?” I hollered to Dennis Lyamkin, a 23-yearold environmentalist, outdoorsman and the only friend willing to start the hike with me, age 53 and an inexperienced backpacker. “Heck, yes!”

We high-fived each other and strode west on the sandy ribbon of Colorado’s Baca County Road A. We turned north on County Road 57, west on C, north on 56, west on D, forcing my diagonal expedition to temporarily obey our American right-angled civilization. Barbed wire fences around each private section of land – rustling fields of last year’s corn or whispering prairie – prevented any diagonal bushwhacking.

Black and white lark buntings, the Colorado state bird, swooped onto barbed wire fences, calling “birdy birdy birdy wheeee!” Kansas winds carried bovine funk from distant feedlots and the diesel thump of irrigation pumps.

A truck rattled up next to us as we walked the road. The window rolled down and a voice floated out, “What are you doin’ out here?”

“I’m India Wood, and I’m hiking diagonally across Colorado from the southeast to northwest corners. This is my friend Dennis.”

“That’s something new. Never seen hik-

ers out here before. Where you from?”

“Boulder.”

He winced.

My hometown of Boulder, sometimes called “the People’s Republic,” has a reputation as the most liberal in the state, especially compared with rural counties. Boulder County voted 77 percent for Biden in 2020, while southeast corner Baca County voted 84 percent for Trump.

“But I was born and raised in Colorado Springs.”

Trump beat Biden in Colorado Springs’ El Paso County by 10 percentage points.

He nodded.

“You have a good walk.”

WALKING GIVES YOU a license to talk to anyone, and for anyone to talk to you. If I had been in a vehicle no one would have pulled over to say hi. On a “real” hiking trail like the Colorado Trail, I would have met mostly other hikers. On foot, hiking across the state on my own route, I needed to meet locals to get permission to camp and hike on their land. By walking, I became part of the landscape and local community. It helped that I spoke a bit of ranch language, having spent teenage summers on ranches near Limon and Maybell.

My older brother had doubted anyone would help me that year of the divisive 2020 Trump-Biden election and COVID-19. My brother had also doubted I had the strength and outdoor skills to do the hike of about 730 miles. He was right – in January. By early May, I had taken classes in backcountry navigation, wilderness first aid and backpacking, and physically transformed myself from a middle-aged schlub into a backpacking beast.

After shutting a metal ranch gate with a “NO TRESPASSING” sign on it, Dennis and I left the road grid behind to hike 8 miles on the two-track paths of the Kelly ranch to Kletis Kelly’s brick house. Kletis limped out, his knee stiff after a bull had mashed him into the corral fence. At age 79, he still put in a hard day’s work beneath a gentle smile. “You made it!” he said. “I knew you would.”

I had met Kletis a month ago because I would need to walk across his ranch on my diagonal route. The Kellys were Republicans and evangelical Christians who used chemical fertilizers and herbicides on their fields of milo and wheat. They killed coyotes so the predators wouldn’t eat their calves, they said. As a consumer of organic foods, I was horrified at first, but then Kletis’ son told me the price of wheat was one-third what it was in 1960, now so cheap in 2020 there was no money for more expensive organic methods. I read that 99 percent of American wheat, corn, and soy fields use chemical fertilizers and herbicides. What I bought at Natural Grocers did not change 99 percent of the picture. But how could I speak up politically without alienating my new friends?

For now, I kept quiet and listened. I liked Kletis. He said since God loves everyone unconditionally, we should, too. We agreed that was a hard task, but it was part of my “going diagonal” philosophy of talking with everyone, of breaking through the self-created boundaries that divide us in this state.

The Kellys’ home smelled of barbecued pork ribs and dusty work boots. Family photos and Christian inspirational plaques hung on the walls. I kept my chair back from the farm table seating seven of us, so nervous about COVID I started to cough violently and threw my long-sleeved elbow across my mouth. Dennis gave me a stern look. No one wore COVID masks here. To have put one on or asked to eat outdoors would have offended them. Instead, we savored pork ribs, potatoes and salad, and drank iced tea while listening to family stories and the lessons therein.

Kletis reminisced about a 1975 tornado that flattened their farm and killed livestock. Their driveway’s line of elm trees, nurtured for decades on the dry plains, had been ravaged to ragged stumps. He said he began to cry at the seeming impossibil-

ity of rebuilding his family’s life but then heard a voice: “Listen to the birds singing, perched in the broken-off elm trees.”

I often remembered that quote along my hike when I started to lose hope, to feel defeated by what I could not control. Like most city dwellers, I thought I could control most things. Not out here. Listen to the birds.

I REACHED LA JUNTA on May 25, amazed I had hiked 150 miles. Dennis accompanied me the first four days to Springfield, then my 23-year-old youngest child, Charli Mandel, walked six days with me across the Rule Creek and Purgatoire River canyonlands to La Junta. Kletis had called me and left a voicemail in his gentle drawl: “Wondering how you were getting along on the trail. Hope everything is going great. Catch you later.”

Yep, going just dandy, I thought, picking at my cracked and sunburned lips. I called Kletis back and confessed that before La Junta, Charli and I had been cornered in our tent by a drunk in the night, nearly froze to death and been chased off the trail by the Cherry Can-

yon Fire. Kletis chuckled and said, “But you made it to La Junta. You weren’t even sure you’d get that far, but you did.”

He would be my Gandalf, checking in every few weeks as I crossed the state along the Great East roads, through the Misty Mountains and Mirkwood, and into the Lonely Mountain. I would discover my dwarvish companions along the way, in unexpected disguises.

IN EARLY JULY, my feet dragged up the jeep ruts of National Forest Road 146 from Tarryall Reservoir over the hills that border South Park. I was delighted I had made it halfway across the state, past Pueblo, Colorado Springs, Pikes Peak and Florissant. But my heart felt half-dead with loneliness, only a few friends willing and able to hike with me for a couple of days each. I expected this vast land would swallow me whole, or I would drift into the sky like an untethered balloon. I tried to grab hold of something. Grasshoppers clicked and jumped beneath clumps of grass. Limber pines gyrated in the wind. Clouds tumbled eastward over the distant Continental Divide.

At the end of a long downhill, a dozen butterflies ambushed me. They flitted over the two-track and landed to lick salt from the mud in a tire rut. Squatting, I could hear their wings beat and marveled at each butterfly’s unique pattern, like grandmother quilts of black, orange, brown and gold. I grabbed hold of their presence, and my heart steadied.

Hearing a distant buzz, I glanced up to see two motorcycles cresting the ridge ahead. My mind slunk into a Mad Max movie, with closeups of missing teeth and spiked gloves. Many hikers scowl at motorcycles on public land, even on an official Jeep trail like this.

The men slowed down the hill and putt-putted toward me. I contemplated quick strides to a granite outcrop I could climb for safety, but I stood my ground along with my winged friends. As the bikers rolled close, I smiled anyway and gestured at the dozen butterflies in my rut. They cut their engines. Together we witnessed the butterfly dance, talking quietly about where we were from and where we were headed. Smiling beatifi-

cally, one biker told me about an exploding hillside of red Indian paintbrush that I should look for along my route, where they had just come from. I found their flowers.

I found flowers and men in other places, too, kindred spirits I never would have met while driving a car.

IN EARLY AUGUST, I strode a fourwheel-drive trail east of Meeker, near the summit of Sleepy Cat Peak, my last of a dozen ascents above 10,000 feet. Stands of white-trunked aspen and dark spruce and fir jostled meadows of skunk cabbage and wildflowers – red, yellow, white and purple. Two familiar border collies and a grulla-colored horse turned their heads to watch me grow from a distant dot to a hiker coming up the ruts.

“Howdy!” I called. A lariat circled the horse’s neck and disappeared into the knee-high grass and wildflowers. “Hiker coming through.”

A brown-plaid arm arose from the bouquet, then a head squinting from sleep. The 60-something sheepherder with a deeply tanned face and merry eyes

ambled toward me. Two border collies gamboled at his feet. The sheepherder made one hand gesture, and his work buddies slunk to the ground, grinning.

“¡Buenas tardes, Toledo!” I said. I had met this Peruvian shepherd, Toledo Echeberria, while scouting my route. I rubbed the heads of the border collies now leaning against my legs.

“¿Los perros grandes?” I asked “¿Grrrrr?” I mimed a fierce dog and pointed over the hill, where I could hear baaing and barking.

“Sí,” Toledo said. “Four dogs.”

I pointed to myself, then grimaced and held out my hands, as if to ask the question, “What should I do when I get to those dogs?”

“You say BACK!” he shouted. “Point to sheep. Dogs no hurt you.”

“Whew!” I put my hand on my heart. “Good to see you. Muchas gracias, señor.”

The two-track meandered north through grassy meadows and archipelagoes of evergreens. Sheep trotted away from me and shook their wooly heads as I called quietly to them, “Hey, sheep. Comin’ through. Hey there.” Two skinny

dogs tore away from the herd toward me, barking, hackles raised like stegosauruses.

“Oh, God help me.”

Ice flashed through my innards. I never before thought of myself as a dog’s dinner, surely much tastier than coyote if they could get through the nylon wrapper.

“BACK!” I pointed toward the sheep as I vaulted away from them into a squelchy marsh, feet wobbling on boulders as my hiking poles fought to prop up me and my 35-pound pack. The dogs came within a few yards, barking madly while two more hellhounds appeared on the ridge. “BAACK! You bastards!” I pointed at the sheep. “BACK!!” The dogs paused as I hobbled frantically around the herd. The closest dog wagged his tail high, triumphant, and they trotted back to their sheep.

I sent good vibes to Toledo in thanks for his advice. Growing up summers on ranches, I had learned there were people who managed the rangeland sustainably and those who did not. What I saw on Sleepy Cat Peak confirmed this. Up toward Toledo’s grazing area, the meadows

Finding a place to camp isn’t always easy. Signs point to private cabins near Florissant, where a friend had to ferry Wood to a campground. South of Craig, a sign marks private property that pushed Wood on a long walk to a friendly rancher’s cot.

looked good, with a wide range of plant species. Good sheepherders like Toledo kept the herd moving daily to fresh forage, a neighboring rancher explained.

That night, after the stegosaurus-hackled dogs, as usual I lay terrified of some man coming after me in the middle of nowhere. I felt like a speck of dust on black glass, alone in the universe. Then I thought of Toledo, as content alone beneath the sun as I was. He must go to sleep each night beneath the stars trusting God or nature to look after him. So I had a chat with the nature goddess, asked her to look after me. And slept. There was something special about Sleepy Cat Peak, my antidote to the Lonely Mountain I had climbed so many nights.

Two more weeks, one more mountain to climb way up in the northwest corner, where the cowboy T. Wright Dickinson and a Great Old Broad held my expedition in their hands.

I HIKED FROM Sleepy Cat Peak downhill a few days and a vertical mile to the Yampa River, past Maybell, northwest on Highway 318, then turned north to Irish Canyon. I had made my homes in cow pastures, on an army cot in a rancher’s workshop, at derelict Juniper Hot Springs, in a friendly Maybell backyard, and at Vermillion Falls, where a new friend delivered fried chicken and chocolate milk to me from Craig.

Along the way, Kletis left me a voicemail: “Wondering how things was going. Maybe you can catch up with me later.” I called my friend to soak up his positive energy, my own ebbing after nearly three months of mostly solo hiking and difficult route reconnaissance. Kletis chuckled at my story of a herd of inquisitive yearling cattle who chased me for a mile up a jeep road, like cats after a grasshopper.

Highway 318 just about killed me: three days of joint-pounding pavement in 90-degree heat and a rowdy crosswind that twisted each stride. The sign at the start of the road just outside of Maybell says, “No services next 120 miles.” Back in the spring, I expected I would hike mostly trails and bushwhack. But Colorado is surprisingly short of hiking trails. And bushwhacking is a martyr’s task with

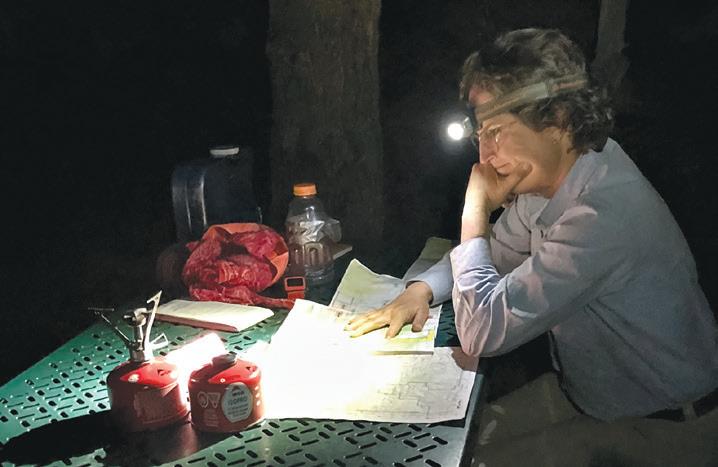

By light of her headlamp, Wood puzzles over rancher T. Wright Dickinson’s handmade map of possible routes for her final push to the northwest corner. Irish Canyon campground offered picnic tables and a pit latrine – rare luxuries along her route.

barbed-wire fences to squeeze under about every half mile, plus cactus, cliffs, downed trees to hurdle and landowners who provide free lead to trespassers. So my feet traveled about half dirt roads and four-wheel trails, one-third hiking trails and ranch two-track, and the remainder two-lane paved roads like Highway 318.

Tears carved trails down my sunscreen-and-dirt-crusted cheeks as I reached the Irish Canyon campground on Aug. 14. I felt like I had chisels in my hip joints. A day off, then three more days of hiking, and I would reach the northwest corner! I sourly regarded Cold Spring Mountain, a 2,000-foot climb between me and the end. My body said, “Nope.” Maybe this was the end, 20 miles from the real finish line. I could come back some other time and finish. My stomach felt like a sack of cow patties.

A chickadee hollered “dee dee dee” from a pinyon tree.

Cristina Harmon, co-chair of the northwest Colorado band of Great Old Broads for the Wilderness, arrived in an aura of cigarette smoke. Back home in Boulder, anyone who smoked was considered deficient. I had never met her in person – she had offered to help me with my hike after seeing the Colorado Sun article about my walk.

A few minutes after we met, I said something crabby about her smoking around camp. Then I wisely shut up. Cristina had the carnivorous smile and

husky voice of a lioness with a mane of gray curls. The Broads advocated for public lands and tight limits on cattle grazing by ranchers like T. Wright Dickinson. Cristina said she wouldn’t argue with him – that wasn’t her way. She said the Broads often showed up with cookies, disarming a contentious environmental meeting with older-woman charm. She had the courage of her convictions. Mine had gone all mushy after listening to every viewpoint for three months.

T. Wright Dickinson clattered into camp in his flatbed farm truck after Cristina’s Subaru. He was fresh-shaved and wore a tailored striped shirt and cowboy hat the color of a pronghorn’s legs. A former Moffat County commissioner and president of the Colorado Cattleman’s Association, newspaper articles described him as a formidable advocate for private land. I was grateful he took the time to help me. It turned out he had checked a cowboy reference I’d given him. My friend had said, “She won’t cause trouble and will shut the gates. She’s too good for Boulder.” I was probably the only Boulderite they’d ever sat down with.

T. Wright’s articulate hands spread out a map of a potential route to the corner across his family’s land and leased holdings on Cold Spring Mountain and Klein’s Hill, six sheets of office paper he had color photocopied and taped together. He grew effusive about his proposed route for me, pointing out springs, places

for grand views across Brown’s Park, and where I might see sage chickens. It sounded lovely. I did my best not to limp as I walked T. Wright back to his truck.

The August evening sun painted the west-facing sandstone cliffs of Irish Canyon gold as Cristina and I talked about my route options on the maps. “I vote Cold Spring Mountain,” I said, my eyes avoiding the lioness.

“But your hip is all messed up,” she said. “You’re walking like an elderly donkey.” Cristina’s eyes caught mine. “Stick to the roads along here.” She tapped her Great Old Broads fingertips on the edge of T. Wright’s map. “You can do each segment as a day hike, and I will shuttle you.”

“You sure you don’t mind?” I squinted at her, a woman I had known only a couple of hours.

“I said I would help you complete your hike, and I will.”

“Thank you.”

I sipped my rooibos chai tea. Things had a way of working out, especially if kindred spirits decided to help. A cowboy and an environmentalist: I needed to listen to both, but like Cristina, I needed to own up to my environmental priorities. Like a guy I met on the road near the Colorado River said, “I got good friends, some I don’t get along with, but they’re still my friends.”

A gray jay called “weep, wurp” from his perch as he awaited our dinner crumbs.

Start date: May 11, 2020

End date: Aug. 18, 2020

Miles hiked: 730

THE NEXT MORNING, I strode northward toward Talamantes Creek, where T. Wright had helped me contact a neighbor whose land I also needed to cross. T. Wright clattered to a stop next to me in his F-350 dually and asked if I needed anything. I said no, just conversation.

He rested his arm on the open window as we talked about sage grouse, which he called sage chickens and the environmentalists called an endangered species – a good tool to stop energy development. T. Wright was proud his region provided natural gas to heat Denver homes, not that anyone there had ever thanked him for it. I told him I appreciated it.

He explained that ranchers helping out sage chickens before the disturbance of energy development was far more effective than remediation afterwards. But the “’ologists,” as he called the degreed biologists and ecologists, favored remediation after. The ’ologists preferred to stare at a computer screen of numbers and mostly refused to listen to people like T. Wright, who had observed nature over decades of drought cycles. He cared deeply for this land, his home.

Those three days on the Dickinson and Raftopoulos ranch lands, owned or leased from the state and federal government, I saw more wildlife than in any other part of Colorado. A badger charged me when I interrupted her digging for ground squirrels. Herds

of pronghorn hustled away from the strange sight of a hiking human. A golden eagle regarded me from a fence post, as did a rattlesnake on the road. The tracks of a bear preceded me over Klein’s Hill, the last rise before the state corner.