Evaluators from the Butler Institute for Families at the University of Denver explored Denver Preschool Program (DPP) educators’ physical and psychological well-being. Evaluators surveyed 410 educators in fall 2022 and interviewed 14 educators in spring 2023. Evaluators asked educators about their job burnout and stress, including the supports and self- care practices they used to reduce the impact of burnout and stress.

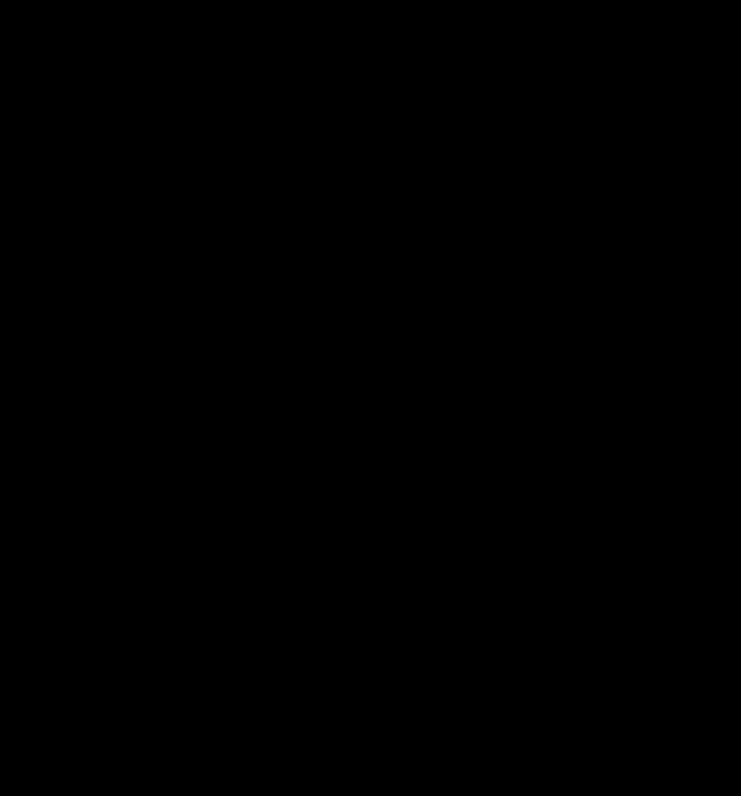

Evaluators asked educators how often they experienced jobrelated stress and burnout, including physical or emotional exhaustion or lack of motivation. Overall, educators indicated feeling symptoms of burnout between once a month and a few times a month (M=3.67), and the most common symptoms they experienced were fatigue and feeling emotionally drained. Figure 1 shows educators’ average frequency of burnout symptoms.

Figure 1. Frequency of Educators’ Feelings of Burnout (n = 389-395)

I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning.

I feel emotionally drained from my work.

I feel burned out from my work.

I feel I'm working too hard on my job.

I feel frustrated by my job.

Working with people all day is really straining for me.

I feel like I'm at the end of my rope.

Additionally, almost three-quarters of educators (71%) reported that they sometimes, often, or very often didn’t have enough energy to spend time with their families. About half of educators (47%) also reported experiencing work-related pain or discomfort in the past.

Teachers’ job stress was positively associated with their burnout, meaning that the higher an educator’s job stress was, the higher their burnout was.

To combat stress and burnout, educators engaged in personal (see Table 1) and professional self- care practices (see Table 2).

Teachers’ most common job stressors:

• Buying supplies for children using their own money

• Regularly working overtime or extra hours

• Feeling pulled between the demands of their job and the needs of their own children

Reasons for not engaging in professional self care:

• Lack of time at work

• Lack of staff/coverage at work

• High child-to -staff ratios

• Negative workplace culture not supportive of self- care practices

Educators appreciated their coteachers and supportive administrators who offered to cover their classroom so they could take a break. Some educators, however, felt like their workplace environment and leadership were not very supportive of their self- care. Only 57% of educators surveyed agreed that the policies at their workplace were flexible enough to meet different employees’ personal and family needs. One educator explained staff at their school “feel like they can’t ask [for a break] because then they’re burdening someone else” and wished for “a more positive culture where it feels a little more accepted to ask for a break.”

Staff must have the time to take care of themselves. One educator frankly said, “Breaks and lunches are a human need. It should be normal that everyone deserves a lunch and a break, period.” Evaluators’ analysis of survey data found that self- care was a statistically significant predictor of educator job satisfaction, meaning that higher frequencies of professional self- care were associated with higher job satisfaction. Professional self- care was also associated with lower levels of educator burnout. DPP can encourage educators to engage in self- care to bolster their job satisfaction and decrease their burnout.

Higher self-care ratings were associated with:

Higher job satisfaction

Lower rates of burnout

Several educators offered recommendations to increase staff’s opportunities for self- care and promote educator well-being To increase breaks and time off, educators wished for more staff to cover their classrooms, a dedicated space to take breaks at their programs, and more planning time. One educator explained that a lack of planning time impacted their mental health, and although opportunity for planning time has increased in recent years, staff shortages made it impossible for the entire early childhood education (ECE) team to plan lessons together. They thought more substitutes, especially those who are comfortable working with children who have unique needs, would also help educators take more time off.

Educators thought trainings about managing their stress, setting boundaries, and preventing burnout would be beneficial. They also emphasized the importance of mental health support like paid mental health days and access to mental health services. They felt like their current benefits do not provide enough financial coverage for mental health services, and they also struggled to find mental health providers who understood the unique challenges educators face. One educator explained: “I’m spending a ton of money just on mental health support that I need but particularly in this field with how quickly you can burnout, our mental health should be prioritized.”

Educators’ recommendations to promote educator wellbeing:

• Staff to cover classroom during breaks

• Dedicated breakroom

• Planning time

• Access to substitutes, especially special education substitutes

• Well-being-focused trainings

• Mental health support (e.g., paid mental health days, access/financial support for mental health services)

• Team building

• Increased pay

programs who have larger classrooms to help them create more opportunities for educators to take breaks. DPP could also continue to advocate for increased pay for educators that would decrease the need for educators to work multiple jobs, which causes more stress and less time for self-care.

3. Support educator mental health: Early childhood educators experience frequent stress and feel burnt out. DPP could advocate for paid mental health days. DPP could also consider partnering with mental health providers who specialize in supporting early childhood educators and provide financial support to access these providers’ services.