Denver Preschool Program Year 2 Evaluation Report

December 2024

APA Consulting

Mariana Enríquez, Dale DeCesare, and Brianna Sailor

Executive Summary

The Denver Preschool Program (DPP) engaged APA Consulting (APA) to conduct an ongoing evaluation of DPP operations. This report summarizes findings from the second evaluation year, covering the 2023-24 school year. The evaluation addressed five key topic areas, including:

1. Impact of UPK on DPP Operations

2. Family and Provider Interactions with DPP

3. DPP’s Tuition Credit System

4. Factors Influencing Family Preschool Choices and Access

5. DPP Impacts on Parents and Providers.

The evaluation used a variety of tools to gather data to answer key research questions in each of the five areas listed above. Such tools included city-wide surveys of preschool providers, of families with 4-year-olds in DPP, and families with 3-year-olds also served by DPP. In addition, the evaluation held numerous focus groups to gather qualitative feedback from families, from providers currently served by DPP (including community-based and school-based providers), and providers not currently participating in DPP. These data gathering efforts produced a rich array of data and findings to help inform the program’s current and future operations.

APA used several different lenses to examine the data, and these lenses are referred to throughout this report. These included a focus on responses received by family income tier (with families in DPP income tiers 1-2 identified as low-income families, families in income tiers 3-4 identified as middle-income families, and families in tier 5 as high-income families); geographic location (with GIS mapping of survey responses by neighborhood and region of Denver broken into Southwest, Southeast, Northwest, Northeast, and Far Northeast regions); by age of child served (families with 4-year-olds in DPP and those with 3-year-olds in the program); and by type of provider (including DPP community-based, DPP school-based, and non-DPP providers).

To facilitate use of this report, a list of highlights is provided at the end of each of the five main sections. All these listed highlights are combined together in the Summary of Findings section at the end of the report which has an added brief summary for each section. This Executive Summary identifies a selection of top findings from among the multitude of highlights provided in the Summary of Findings section of this report.

Key Findings

1. Impact of UPK on DPP Operations

As in year 1 of the evaluation, family and provider focus groups in year 2 corroborated the finding that providers are the primary source of information for families regarding the benefits, requirements, and key components of DPP as well as UPK. Providers therefore play a central

role in helping educate the community about these programs. This highlights the importance of: 1) understanding existing gaps in provider understanding of DPP and UPK; and 2) ensuring providers fully understand DPP, as they are essential spokespersons.

However, data found that average provider understanding of five key topics associated with DPP and UPK operations has room to improve. For instance, 65% of providers indicated either low or average understanding of the amount of funding parents can receive from UPK and 55% were either low or average in understanding whether families can qualify for DPP and UPK funding simultaneously. Given that families consistently say providers are their main source of information about these programs, DPP should consider providing added training or information to providers to boost both provider and family understanding of DPP and UPK

Data also found high percentages of parents of 4-year-old children do not understand many key aspects of the relationship between UPK and DPP and the funding these programs provide. Additional efforts are needed to help educate families about these aspects. Low levels of parent understanding were found regarding what the qualifications are for children to receive DPP and UPK funding, the relationship between DPP and UPK, whether all preschool providers in Denver are providers in both DPP and UPK, and the amount of funding families can receive. Families receiving DPP tuition credits would therefore benefit from learning more about these topics. Parents not currently in DPP are likely even less knowledgeable about the programs.

As discussed further in section 2 findings, having two distinct programs, applications, and enrollment processes was also reported to be a barrier to families participating. Information was reported to be lacking about what order parents needed to complete the applications and make their school selections. Some providers reported significant parent frustration with having to provide application information multiple times.

2. Family and Provider Interactions with DPP

A top identified reason families may choose not to enroll in DPP is that they do not know DPP exists. This finding was consistent from Year 1 of the evaluation and was true both for families with 4-year-olds, and those with 3-year-olds in DPP. Another notable finding was that large percentages of parents of 3- and 4-year-old children believe families do not enroll in DPP because they think their income is too high to qualify. These gaps in parent understanding of DPP highlight the need for the program to continue expanding its efforts to provide information that providers can share with parents, as well as to ensure parents can easily find answers to their questions about the program and dispel current misinformation.

As was found in the first section above on UPK and DPP operations, evaluation data highlighted the need to take additional steps to address parent confusion and frustration around current program enrollment processes. Parents were confused about documentation needed, required timelines, why documentation was needed multiple times for DPP and UPK, what months of the

year were covered by UPK or DPP, whether they were approved to participate, how much tuition support they received, and if they still owed money even after receiving the tuition credits. Some potential recommendations DPP could pursue to help address these challenges include:

• Collaborate with UPK to streamline existing application processes. It would be beneficial to refining existing processes so that common data or information is automatically entered into both systems or to create a universal, single application form that can be used by any type of provider (community based, school based) so families can apply simultaneously to both programs.

• Establish a clear point of contact for parent and provider questions about DPP and UPK enrollment processes.

• Track the most frequently asked enrollment questions from parents and providers for each program, including questions about how the two programs interact, why parents should apply, and tips for streamlining the process of applying to both.

• Create and annually revise responses to the most frequently asked questions to be posted on the DPP web site and distributed to providers to share with parents interested in enrolling their children in one or both programs.

• Create a one pager that graphically shows the application process (e.g., flowchart) for both programs with the specific actions/tasks parents must complete, deadlines, timelines, dates by which families can expect a determination of the tuition credit they will receive and contact information and web links for further information.

Regarding provider participation in DPP, data indicated that, while the current quality rating system could keep some providers from participating, providers on average did not think the rating process was a significant discouraging factor. Instead, providers leaned towards agreeing with the statement that the quality rating system accurately reflected the quality of childcare offered. This suggests a general acceptance amongst providers that the rating process has merit.

3. DPP’s Tuition Credit System

DPP tuition credits are having a high level of positive impact on most participating Denver families across the city. Large majorities indicated they would either not be able to afford preschool or would struggle to afford it without DPP tuition credit support, and the percentage who indicated this increased from Year 1 findings.

Large percentages of families also said that DPP tuition credits encouraged them to send their child to preschool. With the ever-growing body of literature extolling the value and positive impacts of attending preschool on later child outcomes, this finding alone suggests the possibility of a massive return on investment from DPP’s tuition credit program.

Survey data did reveal some variations in regional impact of the tuition credits. For instance, most families in Far Northeast and Southwest Denver reported DPP tuition credits encouraged them to send their children to preschool. These same regions of the city showed survey responses

that almost unanimously indicated families would either not be able to afford paying for preschool without DPP or that it would be financially difficult. In the Northeast region family responses were roughly half and half, and the Northwest region showed response variety by neighborhood, likely driven by income level variations. These data can and should be used to help inform targeted future DPP communication strategies by region or even by neighborhood.

4. Factors Influencing Family Preschool Choices and Access

Almost all families indicated that the preschool director and the teachers having the appropriate training, certificate, or license was an important or the most important aspect of a quality preschool. This was true across all income levels and these quality aspects were also rated the most important qualities in year one of this evaluation. Data also showed that most families were unaware of their child’s preschool quality rating, and the preschool’s quality rating was middle of the pack in terms of importance to families when choosing a preschool.

Parents’ feedback in general indicated that preschool decisions often came down to availability and affordability. But they also indicated affordable, high-quality schools usually had long waitlists, while expensive schools had openings but were not affordable. Parents suggested that, if possible, families should visit prospective sites in person and come prepared with questions to ask teachers and staff. To help support families in this regard, DPP could consider developing a list of research-backed questions parents can ask when visiting preschools to better inform their decision making.

Survey results also showed more than a quarter of providers did not have enough slots to meet parent demand for preschool. The top three existing barriers to increasing the number of available childcare slots were identified as: 1) Inability to pay a high enough salary to attract and retain qualified teachers; 2) Inability to cover the gap between the full cost of providing care and the tuition support provided to families; and 3) Inability to find adequate space to expand their childcare facility. In addition, nearly two-thirds of surveyed providers did not offer infant care. This is particularly critical since providers reported having long waitlists for both infant and toddler care. Overall, childcare demand, especially for infants and toddlers, appears to far outpace current capacity, with some providers describing it as a "crisis."

Evaluation data yielded several suggestions which DPP could explore to help expand preschool supply. Some selected recommendations include: 1) Offering additional professional development for preschool administrators to help them develop their management credentials and grant writing skills; 2) Distribute a monthly newsletter that includes a list of available ECE grants that school administrators could pursue; 3) Encourage state policymakers to pass legislation supporting rent or mortgage assistance for childcare providers to reduce their facility costs; 4) Increase communications to unlicensed providers of the financial benefits of becoming licensed, including the benefit of participating in DPP; and 5) Offer monthly workshops and oneon-one support to help unlicensed providers going through the licensing process.

5. DPP Impacts on Parents and Providers

Evaluation findings identified a multitude of clear and powerful impacts which DPP is having on both parents and providers throughout the city. Large majorities of surveyed families across the city credited their ability to afford more childcare to DPP tuition credits, and this response was consistent across income tiers. GIS mapping of survey data for families of 4-year-olds in response to the question of whether DPP tuition credits afforded them more hours of childcare, revealed the highest proportion of “yes” versus “no” responses in the Far Northeast (about 2.5 times more yes than no responses) and Southwest (nearly 4 times more yes than no responses) indicating an even higher level of DPP tuition credit impact in these regions.

Data also indicated that the increased access to preschool that DPP provides helped parents stay employed or increase their income. GIS mapping of data showed that these reported economic benefits from increased preschool accessibility accrued to families across Denver’s distinct regions and neighborhoods.

More than half of low-income families and over 40% of all families of 4-year-olds indicated DPP tuition credits made their families better able to meet additional basic needs, such as affording groceries, housing, and health insurance. For low-income families, the most consistently indicated need they were better able to afford was food.

In addition, the vast majority of families indicated that the added hours of childcare they could afford because of DPP helped reduce their stress and improved their mental health and self-care. Findings on DPP’s positive impacts on reducing family stress, improving mental health, and improving economic conditions transcended income differences and were consistent across family income tiers.

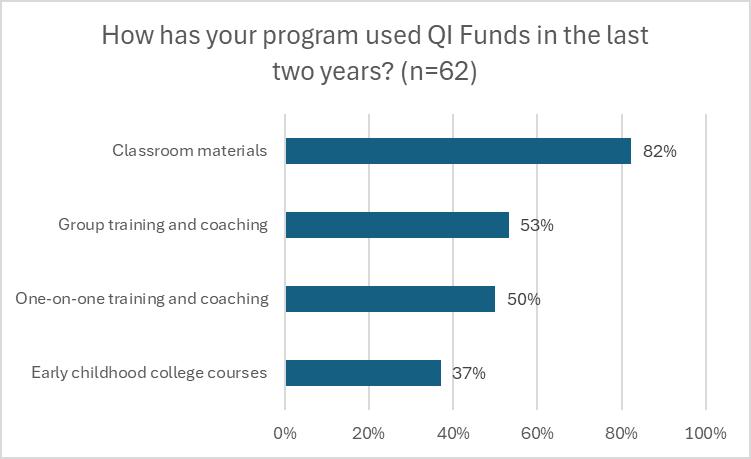

For providers, a key positive DPP impact that was most often cited was that teacher training and coaching paid for with support of DPP’s QI funds was the DPP support that had the greatest impact on child outcomes. Compensation and stipends to recognize teacher time spent in training were greatly appreciated and highly impactful in encouraging teachers to participate in such training. Providers also expressed appreciation for the availability of QI funds to purchase needed classroom supplies and materials, and great appreciation for DPP’s tuition credit system, consistently citing its positive impact on families and the childcare community.

Overall, this Year 2 evaluation underscores the continued importance of clarity, equity, and accessibility in enhancing the impact of DPP and its collaboration with UPK, and in ensuring all Denver families benefit from a high-quality preschool education.

Introduction

Augenblick, Palaich and Associates (APA) was contracted by the Denver Preschool Program (DPP) to conduct a 3-year evaluation of its operations. This report covers the 2023-24 evaluation year, and presents findings in the following five major topic areas:

1. Impact of UPK on DPP Operations

2. Family and Provider Interactions with DPP

3. DPP’s Tuition Credit System

4. Factors Influencing Family Preschool Choices and Access

5. DPP Impacts on Parents and Providers

These areas were selected to address a set of evaluation research questions listed in Appendix A. The APA evaluation team (Evaluation Team) utilized feedback from the Expert Advisory Group (EAG) to establish the priorities regarding DPP’s operations that should be addressed during each year of the evaluation. Dr. Cristal Cisneros, DPP’s Senior Director of Evaluation and Impact, also provided feedback on the design of data collection instruments and data collection activities. The evaluation team wishes to thank the EAG and Dr. Cisneros for their support.

Data were collected from English and Spanish speaking families of 4-year-olds and families of 3year-olds enrolled in DPP who received tuition credits during the 2023-24 school year, from schoolbased and non-school-based 1 childcare providers active in DPP, as well as childcare providers who were not participating in DPP during the 2023-24 school year. Data were analyzed based on families’ income tiers as identified by DPP, by geographic region where they live, and by type of childcare provider, school-based or non-school-based. Based on the results of the analyses conducted on evaluation data from the 2022-23 school year, the evaluation team decided to split the city into five regions (far northeast, northeast, northwest, southeast, and southwest) using Broadway and Alameda Avenue as the primary axes of this geographic division and separating far northeast neighborhoods 2 from the northeast region. These analyses were conducted with the purpose of supporting DPP in promoting equity and ensuring equitable access to high-quality preschool.

It is expected that this disaggregation of data will help DPP and the evaluation team understand families’ different lived experiences as they relate to accessing preschool for their children, as well as availability of services. Findings are presented broken down by the five major topic areas listed above. Key findings are highlighted at the end of each of these five sections and are presented in bulleted form as “Section Highlights.” The overall set of these highlights is also presented in Section IV, along with recommendations from the APA evaluation team in Section V.

1 School-based providers who participated in the data collection include Denver Public Schools and Charter school providers. Non-school-based providers include faith-based and community-based providers and are interchangeably referred to as community-based providers or non-school-based providers.

2 The Far Northeast Region includes the Montbello, Gateway-Green Valley Ranch, and DIA neighborhoods.

Participant Sample

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from childcare providers and families via a mix of online surveys and virtual focus groups. Data were collected in English and Spanish according to participants’ preference. This section describes both groups of participants and the process used to engage them in the evaluation.

Providers

A list of 272 preschool providers registered with DPP for the 2023-24 school year 3 was used as the primary source of contact information of preschool center directors to be invited to participate in the evaluation data collection activities, including online surveys and focus groups. This list included 88 school-based (DPS and charter schools) and 184 community-based (community- and home-based) preschool centers. A total of 241 of these providers were located in the City and County of Denver, while the remaining 31 providers were based in other cities in the Denver metro area 4. An additional 21 non-DPP preschool providers were identified through a search of Colorado licensed childcare facilities. Contact information of principals and/or assistant principals of DPS and non-DPP providers was obtained from the websites of each individual school.

All 272 DPP preschool providers were sent an email invitation to complete an online survey on the topics of the impact of UPK on DPP operations, customer service/interaction with DPP, choosing preschool, and maximizing DPP impacts and access to childcare. The survey included a question asking providers if they were interested in participating in a virtual, 60-minute focus group to talk about their experiences with DPP. An email invitation to participate in focus groups was sent to all providers who, in the survey, indicated they were interested, or did not answer the question. Table 1 shows the distribution of providers invited to participate in the data collection, broken down by type of center and region. Figure 1 presents the distribution of all invited providers broken down by region. The northeast region had the highest representation at 33%, followed by the southeast with 22%, the northwest with 20%, the southwest with 16%, and the far northeast with 9%. Community-based preschools were represented by 63% of providers, while the remaining 37% were school-based (mainly DPS) providers

3 This list of active DPP providers was secured from MetrixIQ in late November of 2023. Per MetrixIQ classification, provider type included Denver Public Schools and Community providers.

4 Providers outside of the City and County of Denver included 11 in Aurora, 4 in Littleton, and between 1 and 2 in Centennial, Cherry Hills Village, Commerce City, Englewood, Greenwood Village, Lakewood, Sheridan, Westminster, and Wheat Ridge. These preschool centers provided services to families living in Denver, therefore, qualifying for DPP tuition credits.

Table 1. Region distribution of providers invited to participate in data collection (n and %)

Figure 1 shows these data graphically, again showing that there were relatively similar proportions for the NW, SE and SW regions. The FNE had about half the number of any of these three regions, while the NE region had the highest number of providers. Even when FNE was separated from NE into its own region, the NE continues to have the largest response compared to the other regions as shown in Figure 2.

Providers’ overall response rate to the survey was 31%. Figures 1 and 2 combined show a similar regional distribution of DPP survey providers who were invited to complete the survey compared to those who completed the survey (e.g. 22% of invited providers were from the SE region and 21% of those responding to the survey were from the SE region). This indicates a proportional regional response to the survey from across the city.

Providers’ interest in participating in the evaluation team’s focus groups was low in spite of encouragement to participate from DPP personnel and the evaluation team. Twenty community providers representing the five Denver regions participated in five one-hour virtual focus groups, one per region, while four school-based providers representing three Denver regions participated in a one-hour virtual focus group. The 21 non-DPP preschool providers were also invited to participate in one-hour virtual focus groups, with only two of them, representing two regions, accepting the invitation. Individual virtual interviews were conducted with the two non-DPP providers to accommodate their schedules. All sessions were conducted in English and participating providers received a $40 Amazon gift card in appreciation for their time and input in the data collection.

Families

Families of 4-year-old students

During the 2023-24 school year, 2,642 four-year-old students were identified as receiving preschool tuition credits from DPP 5. Figure 3 shows the distribution of these students’ families

5 The number of families included in the data collection reflects one moment in time in November of 2023, when many students were still pending school assignment/matching through the new enrollment process implemented by UPK. With the purpose of using the most reliable list of DPP participants, the evaluation team removed from the list students who had no school assigned, duplicate cases (e.g., students listed as enrolled in two different DPS schools), families without email addresses, and students listed as inactive, as well as parents of students with more than one student enrolled in different schools. Parents of twins or siblings attending the same preschool were included in the data collection efforts.

by income tier and city region as of fall 2023. Data indicates that families from the NE region had the highest participation in DPP (32%), while all four of the other regions had similar participation levels of between 16% and 19%. The data also show that Tier 1 had the highest participation in DPP, followed by lower participation levels of families in Tiers 5 and 2. Tiers 3 and 4 had the lowest participation levels in DPP at the time these data were secured.

It is important to note that patterns of participation and responses of families in middle income tiers (Tiers 3 and 4) tend to be very similar and distinct from families in lower and higher Tiers. Therefore, for purposes of data interpretation, families in Tiers 1 and 2 will be identified as lowincome, families in Tiers 3 and 4 as middle-income, and families in Tier 5 as high-income families.

These data suggest that DPP is supporting a higher proportion of low-income families, while higher income families are also benefiting from the program. The low participation levels of families from middle-income, Tiers 3 and 4, could be a topic that is worth additional investigation in Year 3 of the evaluation, to gather additional data on factors that might be contributing to a lack of participation in these middle-income groups. However, given that the dataset is representative of one point in time when many families were not yet matched to a DPP preschool, the evaluation team cannot draw further inferences from the data at this time regarding the low participation rates. Further study is necessary to understand what, if any, factors could be preventing these families from participating in DPP.

Figure 4 shows the proportion of families of 4-year-old students receiving DPP tuition credits by income Tier, while Figure 4b shows the geographic distribution of families receiving DPP tuition credits by income Tier in Spring 2023. Data show that more than half of DPP’s families (57%) are in the lowest income levels (Tiers 1 and 2), while almost one quarter of all families (23%) come from high-income households (Tier 5). As stated earlier, a very low proportion (6%) of middle-income families (Tiers 3 and 4), were enrolled in DPP at the time the dataset was obtained by the evaluation team.

Figure 4b. Geographic distribution of families receiving DPP tuition credits by income tier, Spring 2023

Figure 5 shows the proportion of families of four-year-old students receiving DPP tuition credits by city Region. Data show that just over half of these families (51%) reside in the northeast and far-northeast regions of Denver, while the other half live in the northwest, southeast, and southwest regions, with similar proportions of families receiving DPP tuition credits. Data therefore indicate not only that the NE and FNE regions are geographically larger, but also show higher percentages of DPP families living in those regions.

Families were sent an email, in English and Spanish, inviting them to complete the online survey. The email included links to both the English and Spanish versions of the survey. As an incentive, families were offered a $30 Amazon gift card if they were one of the first 100 parents to complete the survey. In addition, they were informed that all parents completing the survey would be entered into a drawing to have a chance to win one of two electronic Tablets. The survey was open for two and a half weeks in July 2024 and parents received two reminders to complete the survey before it closed.

A total of 223 families completed the survey 6, representing an 8% response rate of parents of 4year-old DPP students. The highest representation came from the NE region with 35% of the surveys, followed by the NW region with 22%, the SE region with 18%, FNE with 14%, and SW with 11%. Income Tier representation included 46% from low-income families (Tiers 1 and 2), 31% from high-income families (Tier 5), and 7% from middle income families (Tiers 3 and 4).

Table 2 shows additional details on the family survey respondents.

Table 2. Number of survey participants (parents of 4-year-olds) by income tier and region

Table 3 shows that more than half (59%) of the children of all survey respondents attended a school-based preschool. Data also show that children from low-income families (Tiers 1 and 2) were close to three times more likely to attend a school-based (n=75) than a community/nonschool-based (n=28) preschool. By contrast, high-income families (Tier 5), strongly favored community/non-school-based preschools, with almost twice as many of them (n=45) choosing these preschools, as compared to school-based centers (n=24). Middle income families (Tiers 3 and 4) show relatively similar preference for both types of preschools, with just a slight tendency towards school-based providers from families in Tier 3.

6 The total number of surveys collected was 228, 209 of them in English and 19 in Spanish. The number was reduced after removing surveys that were very incomplete and were not included in the analyses.

Table 3. Number of survey participants (parents of 4-year-olds) by income tier and type of provider

Data from Table 4 show that families in the SW, FNE and NW regions have a higher preference for school-based preschools as compared with community/non-school-based preschools, with ratios of 3:1, 2:1, and 1.5:1, respectively, in favor of school-based centers. Families from the SE and NE regions show an equal or almost equal distribution between both types of preschools. It is unclear, however, whether the different concentrations of families by type of preschool is due to a preference for the type of preschool, the availability of preschools in the area, a combination of these factors, or other factors not evident from the survey data collected. Qualitative data collected from families and providers –reported later in the Choosing Preschool section of this report– will help to get a better understanding of the preschool selection decisions of DPP families.

Table 4. Number of survey participants (parents of 4-year-olds) by region and type of provider

Through survey data we found:

● Half (50%) of families with four-year-olds surveyed had two children under 18 years old living in their household. The most children under 18 years old living in any surveyed family’s household was eight children. The distribution of family size was similar across all five regions of the city, with an overall average of 2.33 children under 18 years old living in the households of the families surveyed.

● Half of the families surveyed (50%) had two people in their household working a paid job and 38% of surveyed families had one person in their household working a paid job. Low-income families (Tiers 1 and 2) account for 67% of families working less than two

jobs and for 25% of families working two or three jobs. On the other hand, high-income families (Tier 5) account for 18% of families with less than two jobs, and for 43% of families who work two or three jobs.

● On average, 64% (n=143) of respondents stated that they worked 25 hours or more a week; 38% of these families are high-income families (Tier 5), while 32% are lowincome families (Tiers 1 and 2). Also on average, 13% (n=28) of respondents indicated that they worked less than 25 hours a week, 79% and 14% of them are low- and highincome families, respectively. A total of 18% of responding families indicated that no one in their household had a paid job, with two thirds of them (66%) being from lowincome families.

Families of 3-year-old students

The evaluation team obtained contact information from 295 families of 3-year-old children enrolled in DPP during the 2023-24 school year. These families were all low-income (DPP’s Tiers 1 and 2) and enrolled in community-based preschools. Tier level and being enrolled in a community-based preschool were requirements to receive DPP’s tuition support for 3-year-old children 7. Figure 6 shows the geographic distribution, by city region, of these families as of fall 2023. Data show that families from the NE region had the highest participation level (36%), followed by FNE families (26%). Families in the SW and SE regions represented less than half (16% and 13%, respectively) the level of participation than those in the NE region. Families in the NW region had the lowest level of participation (9%).

7 Three 3-year-old children started the school year attending community-based preschools, but had switched to ECE3 programs in Denver Public Schools by the time families completed the evaluation survey.

Following the same outreach process used for families of 4-year-old students, families were sent an email, in English and Spanish, inviting them to complete the online survey. The email included links to English and Spanish versions of the survey. As an incentive, families were offered a $30 Amazon gift card if they were one of the first 40 parents to complete the survey. The survey was open for two weeks in July 2024 and parents received two reminders to complete the survey before it closed.

A total of 33 families of three-year-old students completed the survey 8, representing a 12% response rate. Four of those families completed the survey in Spanish. Figure 7 shows the distribution of survey responses by city region. The FNE region had the highest representation (43%), followed by SE (21%), and by NE and SW (18% each). Interestingly, no survey responses were received from the NW region, which had the lowest representation overall of families receiving DPP tuition credits for three-year-old children.

Figure 8 shows a comparison of the proportion of families of 3-year-old children receiving DPP tuition credits against the proportion of families who completed the survey. Data show a 16% increase in representation from families in the FNE region, as well as smaller increases for the SE and SW regions. The proportion of families in the NE region shows an 18% decrease (50% effective decrease) between families receiving the tuition credits and those who completed the

8 There were a total of 35 surveys collected but three were deleted from the database and analyses because they were very incomplete. Two of these surveys were in Spanish.

survey. Families with three-year-olds in the NW region had no representation at all in the survey completion.

Additional survey sample findings from families with three-year-old students:

● Close to half of families surveyed (46%) had two children under 18 years old living in their household, while 30% of families surveyed had only one child under 18 years old living in their household. The most children under 18 years old living in any surveyed family’s household was seven children. Families had an average of 2.21 children under 18 living in their households.

● More than half of families surveyed (58%) had one person in their household working a paid job, while one third of surveyed families (33%) reported that two people in their household were working a paid job. The remaining 9% of families indicated that no one in their household had a paid job.

● 61% of survey respondents reported that they work an average of more than 25 hours a week, 18% work under 25 hours a week, and 21% reported that they do not work.

Section Highlights

The participant sample section of the report included the following highlights:

1. A list of 272 preschool providers registered with DPP for the 2023-24 school year was used as the source of contact information of preschool center directors invited to participate in evaluation data collection activities, including online surveys and focus groups.

2. During the 2023-24 school year, 2,642 four-year-old students were identified as receiving preschool tuition credits from DPP and their parents were invited to participate in evaluation activities.

3. The evaluation team also obtained contact information from 295 families of 3-year-old children enrolled in DPP in the 2023-24 school year. These families were all low-income level (DPP’s Tiers 1 and 2) and enrolled in community-based preschools.

4. Data indicated families of four-year-olds from the NE region had the highest participation in DPP (32%), while all four of the other regions had similar participation levels of between 16% and 19%.

5. More than half of DPP’s families (57%) are low-income, while almost one quarter of all families (23%) come from high-income households.

6. A very low proportion (6%) of middle-income families were enrolled in DPP when the dataset was obtained. Further study is warranted to understand the factors that might contribute to these participation differences, particularly for middle income families.

7. Data were analyzed by five geographic regions of the city, including: Far Northeast (FNE) including Montbello, Gateway-Green Valley Ranch, and DIA, Northeast (NE), Southeast (SE), Northwest (NW), and Southwest (SW).

8. Data were also analyzed by family income tiers grouped into three main categories: Lowincome (Tiers 1 and 2); Middle-income (Tiers 3 and 4); and High-income (Tier 5).

9. Providers’ overall response rate to the survey was 31%. The responses received by region of the city were roughly in proportion to the number of invitations sent by region. Parents of four-year-old children had an overall response rate of 8%, while parents of three-year-old children had an overall response rate of 12%.

10. Survey data show that families in the SW, FNE and NW regions have a higher preference for school-based preschools as compared with community/non-school-based preschools. Families from the SE and NE regions showed a relatively equal preference between both types of preschools.

11. Survey data show children from low-income families were close to three times more likely to attend a school-based preschool versus non-school-based.

12. By contrast, high-income families strongly favored community/non-school-based preschools. Middle income families showed relatively even preference for both types of preschools.

Findings

Findings from APA’s evaluation of DPP’s operations are organized by a set of research questions contained within five major focus areas, including:

1. Impact of UPK on DPP Operations

2. Customer Service/Interaction with DPP

3. Tuition Credit System

4. Choosing Preschool

5. Maximizing DPP Impacts and Access to Childcare

The evaluation team’s description below of Year 2 (2023-24) findings is organized by these five major topic areas.

1. Impact of UPK on DPP Operations

To understand the impact of UPK on DPP operations, it was important to first appraise providers and families’ understanding of UPK and DPP, as well as the differences and relationship between the programs. Data were collected from families and providers through online surveys and focus group conversations in reference to these topics. This section describes the findings from these data collection efforts, first for providers, then for families.

Provider Input

Data were collected from community-based and school-based preschool providers 9 participating in DPP as well as from community-based providers not participating in DPP during the 2023-24 school year. The understanding of these groups of providers differed regarding the characteristics and relationship between DPP and UPK. The providers’ description of the two programs included the target population in terms of geography and age, what activities are funded, what the purpose of the funding is, and their funding sources as described below.

Data collected indicate that not all providers who completed the survey were UPK participants, and it is reasonable to expect that those who were UPK participants may have a better understanding of the program’s operations than those who had not established a relationship with UPK. Figure 1.1. shows a comparison of survey participants’ breakdown of their actual UPK participation in 2023-24 and their UPK enrollment status for 2024-25. Responses indicated that 73% of providers were working with UPK in 2023-24. This figure increased slightly by 2.4 percentage points to 75% for the 2024-25 school year. A very small proportion of providers, 1.2%, was unsure at the time of the survey whether they would participate in UPK in 2024-25.

9 All school-based providers who participated in the focus groups were DPS providers.

Figure

1.1. UPK Provider Participation Status in 2023-24 & 2024-25

Table 1.1. shows a breakdown of providers who completed the survey by region, type of preschool (school-based or community-based), and their UPK status in 2023-24 and 2024-25. Data show that providers from the Northeast region had the highest representation overall (35%), followed by Southeast (21%), Southwest (18%), Northwest (17%), and Far Northeast (10%). Eighty percent of respondents were from community-based centers. There were no school-based providers from the Northeast region completing the survey, while Far Northeast respondents were half each from school-based and community-based preschools. The percentage of UPK providers in 2023-24 and 2024-25, by region, fluctuated between 64% (NW) and 88% (FNE). Interestingly, the only region that showed any increase in providers registered with UPK from 2023-24 to 2024-25 was the Northeast region (which went from 69% in 2023-24 to 76% in 202425, for a net increase of two providers). There was no change in the number of providers registered to participate in UPK from the other four regions.

Table 1.1.

(*) Percentages based on total number of providers by region.

Target population. According to focus group data, most providers had a clear understanding that DPP provides funding for preschool children, mostly 4-year-old children, who live in Denver. They also generally understood that UPK provides funding for 4-year-old preschool children across Colorado. Not all providers understood, however, the exact Denver geographic boundaries for DPP, and some indicated in focus groups that they knew there were families who had a Denver address but did not qualify for DPP funding. Similarly, not all providers knew that DPP also funds preschool for 3-year-old children who meet certain criteria. A few community- and school-based providers believed Denver families may not qualify for DPP funding because their household income is too high. Few providers were aware that UPK also funds preschool for 3year-old children who meet criteria such as having an IEP. One community-based provider mentioned that UPK also gives tuition to some two-and-a-half-year-old children.

What is funded by DPP. All providers understood that DPP and UPK provide funding to cover preschool tuition of 4-year-old children. Not all providers understood the range of factors considered to determine the amount of tuition credits DPP families receive, although all were aware that family income was one factor in that decision. Community-based providers were more likely to report the elements incorporated in the formula that calculates the DPP tuition credits awarded to families, including family income, household size, attendance, and the preschool’s quality rating. Community-based providers also generally understood that DPP distributes funding to providers for classroom supplies, coaching and professional training opportunities for teachers and school administrators, as well as stipends that providers use in different ways to support their staff. No school-based providers or non-DPP providers that participated in the focus groups were aware of these additional DPP benefits.

Purpose of funding. All providers in focus groups understood that UPK funding has the purpose of supporting families across the state to send their 4-year-old children to preschool by paying for 15 hours a week of their tuition. By contrast, most community-based providers mentioned that DPP is interested in not only funding preschool, but also in supporting and increasing the quality of preschool education by providing funding to purchase classroom supplies, stipends, coaching, and training opportunities for teachers and childcare directors. In this way, focus group input surfaced a finding that many providers perceive DPP to provide more broad-based support for both providers and parents. A community-based provider expressed it this way, “DPP is really working on offering quality childcare to all children, especially those children in the year before kindergarten…UPK is just trying to make available preschool for all kids, so giving them that limited 15 hours worth of preschool per week.” (SW, DPP community-based provider). 10 11

Funding sources. Providers appeared to have a clear understanding of basic differences in funding sources between DPP and UPK. In fact, all providers participating in the focus groups understood that DPP funding comes from local tax dollars from the City of Denver, and UPK funding comes from the state. A community-based provider went further to explain that when providing funding for a family to send their child to preschool, UPK dollars are applied first to cover 15 hours a week, and then complemented with DPP funds.

Relationship between DPP and UPK. Focus group data showed that the understanding of the relationship between DPP and UPK was different for school-based and community-based providers. School-based providers who participated in focus groups recognized that they did not know/understand the relationship between UPK and DPP, how the programs worked together, or whether the funding for both programs had merged. Providers were also unclear as to how the UPK roll out might have produced changes in the number of students allowed per preschool classroom. One provider explained, “I feel like DPP funding is now rolled into UPK, like it's not separate anymore. And that there's different requirements for each; like with DPP we used to have a cap of 16 students, and now, because it's part of the state, it's 20 [students]” (NW, DPP schoolbased provider).

School-based providers were not aware of the role of DPP within UPK. As one provider in the focus group stated: “I don't know how they work together and if they work together. It's enough so we can provide those seats to children.” (SE, DPP school-based provider). One of these

10 Quotations in the report have been minimally edited to facilitate reading.

11 Throughout the report, parents’ quotations will be identified by the family’s DPP income tier level, Tiers 1 through 6 (T1 to T6), the type of preschool the child attends (school-based or community-based), and Denver’s geographic region where they live (FNE, NE, NW, SE, or SW). Preschool providers’ quotations will be identified by the geographic region where the center is located, their DPP status (DPP or non-DPP), and the type of preschool provider they are (school-based or community-based).

providers also believed that Head Start works with UPK, so their seats are filled with UPKapproved students.

In comparison to the school-based providers, most community-based providers who participated in the focus groups were more familiar with the relationship between DPP and UPK. Very few of them knew the exact role of DPP as one of UPK’s Local Coordinating Organizations (LCO) or the exact role of the LCOs overall. However, most did understand there is a partnership between DPP and UPK and that UPK funding is channeled through DPP to UPK-enrolled families and providers, independently from their own DPP funding. As an illustration of this understanding, one provider explained,

“I don't think it's … and not in a negative way, I don't think it's a collaborative relationship [between DPP and UPK]. I think it's two different entities trying to get their work done and DPP just happens to be the conduit between the state and providers.” (NE, DPP community-based provider).

Community-based providers also knew that DPP and UPK funding sources, application processes, and amount of funds provided were different. Community-based providers saw DPP as the “middleman” between UPK, providers, and families. Providers understood that DPP helps families connect with UPK, and that families can receive funding from UPK and DPP at the same time.

While the sample size of non-DPP providers participating in APA’s focus groups was small, participants understood that DPP and UPK are two different programs and that providers can participate in one or both programs independently. These providers understood that UPK funding is channeled through DPP, an organization that has been in operation for many years, while UPK is a new program that is still working out glitches in its delivery.

The online survey completed by 84 providers included eleven items addressing their level of understanding of topics related to the relationship between DPP and UPK. 12 Overall findings show that providers self-rated their understanding mostly as high or average. However, provider survey data show areas of weakness such as understanding how families are matched with UPK providers, the amount of funding that families can receive from UPK, and DPP’s and UPK’s funding sources. Regional variations were observed, with Northeast and Southwest providers consistently showing the highest and lowest levels of overall understanding, respectively. In general, data show that providers had a better understanding of details surrounding DPP as compared to their understanding of UPK, a not surprising trend given that all survey respondents were DPP providers, while only 73% of them were UPK providers, as already described.

12 Survey items were set in a 5-point Likert scale with the following anchors: 1=Very low understanding, 2=Low understanding, 3=Moderate understanding, 4=High understanding, and 5=Very high understanding. For purposes of data interpretation and reporting, scores 1 and 2 are grouped and labeled as Low understanding; 3 as Average understanding, and 4 and 5 as High understanding.

Figure 1.2. shows that, overall, the majority of providers reported having an average or high level of understanding of general operations, rules, and procedures for both DPP and UPK. When considering the five survey items together, 72% of providers reported a high or average level of understanding of both programs’ operations. Providers reported the highest level of understanding of children’s age eligibility requirements for DPP and UPK funding (51%), while the matching of families to UPK providers was the least understood of these five components (37%). These data are supported by focus group findings where providers indicated that families are often matched to preschools that are not a good fit for the child, the family, and/or the preschool, with a lack of understanding of the process that resulted in such incompatibility.

Figure 1.2 Percentage of providers rating their level of understanding of DPP and UPK operations (n=75*)

(*) n value for these items varied between 75 and 76; 75 was chosen as the most common of the two values to facilitate reading.

Table 1.2. shows averages of providers’ self-rating of their level of understanding of DPP and UPK operations across five key areas. Responses were assigned numeric values of between 1 (Very low understanding) and 5 (Very high understanding). Data show that providers from the Northeast region self-rated their understanding the highest in four of the five items, while Southwest providers self-rated their understanding the lowest in four of the five. These results yielded an almost one-point average difference between providers of these two regions (NE = 3.52, SW = 2.61).

Regional averages across the five key areas indicate that Southwest providers rated their understanding of these combined topics between low and moderate (2.61); Far Northeast, Northwest, and Southeast providers rated theirs in the moderate range of understanding, and Northeast providers rated their understanding between moderate and high (3.52).

Data in the Table’s “Average by item” column also lists the five components in descending order from easiest to hardest to understand (top to bottom). Interestingly, average understanding of these topics was not rated as high or very high by any group of providers. Given that families identify providers as their main source of information about DPP and UPK, these findings suggest that additional training and/or information offered to providers could produce an overall community-level improvement in the understanding of these important programs.

Table 1.2. Providers' average level of understanding of DPP & UPK operations in Five Key Areas (n=76*) (**)

Providers' understanding of…

The age groups of children eligible for funding from DPP and UPK

The difference in enrollment processes for families in DPP and UPK

families are matched with UPK providers

(*) n value for these items varied between 75 and 76; 76 was chosen as the most common of the two values to facilitate reading.

(**) Understanding rating scale: 1=Very low understanding, 2=Low understanding, 3=Moderate understanding, 4=High understanding, 5=Very high understanding.

These survey findings are supported by qualitative data collected from providers in APA’s focus groups. For example, as discussed above, most community-based providers understood there is a relationship between DPP and UPK in which DPP is the entity with whom providers and families interact to reach UPK, e.g., DPP supports providers and families to maneuver, understand and connect with UPK, and DPP passes UPK information down to providers. Although most providers did not understand the exact function of DPP as UPK’s LCO, they understood that DPP and UPK work in partnership, that there is no programmatic crossover between both entities, and that DPP ultimately funnels UPK’s money to providers. Finally, providers recognized and understood that UPK’s first year of operations was very challenging

for all involved and indicated their belief that DPP became the providers’ and families’ lifeline due to its long experience working with them.

Figure 1.3. shows that providers reported generally having a high level of understanding of the activities that DPP and UPK fund, as well as of providers’ requirements to participate in DPP. This was not the case for their understanding of other aspects of DPP and UPK funding. There was a difference for instance in providers’ understanding of the amount of funding parents can receive from either program: for DPP, 43% of respondents reported a high level of understanding, while the same was true for only 36% in regard to UPK.

On the other hand, over half of respondents (54%) reported a high level of understanding of the providers’ requirements to participate in DPP, which was higher than their understanding of the requirements to participate in UPK (for which 39% of respondents reported a high level of understanding, representing a difference of 15.3 percentage points between the two programs). The gap between the level of understanding of DPP components as compared to those of UPK is perhaps not surprising given that all survey respondents were DPP participants while only around 70% of them were UPK participants.

Figure 1.3 Percentage of providers rating their level of understanding of DPP and UPK funding and participation requirements

(*) n value for these items varied between 75 and 76; 76 was chosen as the most common of the two values to facilitate reading.

Table 1.3. presents averages of providers’ self-rating of their level of understanding of DPP and UPK funding and providers’ participation requirements, with responses assigned a numeric value from 1 (Very low understanding) to 5 (Very high understanding), broken down by item and region. The first four items relate to DPP and UPK funding, while the last two refer to providers’ requirements to participate in both programs.

Data show that, overall, Southeast region providers rated their understanding of DPP and UPK funding and provider participation requirements the highest of all five regions, compared to Far Northeast providers whose ratings were the lowest showing almost one point average difference between providers of those regions (SE=3.44, FNE=2.45). Southwest providers were second lowest in rating their understanding overall of these topics. Regional differences indicate that Southeast providers rated their understanding of these topics between moderate and high, Northeast and Northwest providers also rated their understanding between moderate and high, although much closer to moderate, and Far Northeast and Southwest providers rated their understanding between low and moderate.

Of note, understanding of providers’ requirements to participate in DPP and in UPK was rated higher (fifth and sixth items), in general, than most DPP and UPK funding topics (first through fourth items), by providers of all five regions. The moderate to high levels of understanding of the providers’ requirements to participate in DPP and UPK makes sense given that providers in DPP have to renew their enrollment with DPP on an annual basis, and the fact that UPK, as a new program, has received ample media coverage and providers have been encouraged to participate. It is interesting, although not surprising, however, that one of the two non-DPP providers interviewed by the evaluation team is a UPK but not a DPP provider and knew more about UPK than DPP requirements. The second non-DPP provider interviewed was not a UPK or DPP provider and expressed not being familiar with the requirements of both programs.

Table 1.3. Providers' average level of understanding of DPP and UPK funding and participation requirements (n=76*) (**)

Providers' understanding of…

The amount of funding that families can receive from DPP

Whether families can qualify for both UPK and DPP funding at the same time

The amount of funding that families can receive from UPK

DPP's and UPK's funding sources

The requirements for providers to participate in DPP

The requirements for providers to participate in UPK

Average by region:

(*) n value for these items varied between 75 and 76; to facilitate reading 76 was chosen as the most common of the two values to facilitate reading.

(**) Understanding rating scale: 1=Very low understanding, 2=Low understanding, 3=Moderate understanding, 4=High understanding, 5=Very high understanding

The relatively low average ratings of understanding DPP and UPK funding sources by survey respondents differs from the input received through APA’s focus groups. All the focus group participants for instance knew that DPP is funded by taxes from the City of Denver, while UPK is funded by the state. This discrepancy in findings with the survey data could be due to various reasons, including, a bias in the self-selection of focus group participants (those who agreed to participate might have been more informed overall about DPP and UPK than average providers across the city), the difference in sample size for both groups of respondents, or the wording of the survey question as compared to the opportunity that focus group participants had to explain their understanding of this topic.

Families Input

APA collected both survey and focus group data from families to gauge their understanding of the relationship, roles, and differences between DPP and UPK. Most parents of 4- and 3-year-old children who participated in the focus groups explained that they found out about UPK from communications with their preschool providers, however, the extent of the information was mainly that families needed to complete a new application (UPK) to receive the funding that would pay for their children’s preschool. One parent was told that applying to UPK would benefit both the child and the school. Other parents found out about UPK from friends or

neighbors, through online conversations with other parents, or through searches for preschool options on the Internet.

Most parents in the focus groups had limited understanding of what UPK was or that completing the UPK application was optional. For example, one parent of a 3-year-old child indicated their belief that UPK enrollment was a requirement to get DPP support, while a Spanish speaking parent was told she needed to complete two applications to get free preschool for her child, one application was for DPP and the other to be placed in a waitlist to get a spot in the school closest to home.

Survey data collected from parents indicated that 92% (n=196) and 73% (n=33) of parents of 4and 3-year-old children enrolled in DPP, respectively, were aware that Colorado has a Universal Preschool Program. Data show that 13 of the 15 (87%) parents of 4-year-old children who were not aware of UPK were low-income parents, while 5 of the 15 (33%) lived in the Southwest region of Denver.

A total of 182 parents of 4-year-old children answered a question about their child receiving UPK tuition support, 63% of them indicated that their child was receiving such support, while 20% said their child was not receiving UPK support, and 18% were not sure/did not know if they were receiving UPK support. 13 Of the 20% that stated that their child did not receive UPK tuition support, 40% were high-income families, 46% lived in the Northeast region, and 32% were located in the Southeast region. Of the 18% that stated that they were unsure if their child was receiving UPK tuition support, 77% were low-income families. Figure 1.4 displays a map of these parent responses. This map shows a number of the grey “unsure” responses in and around the Southwest region of the city.

13 Totals may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 1.4 Family Survey Question: Is Your Child Receiving Tuition Support from UPK?

Parents’ comments about learning about UPK from providers is consistent with providers’ observations that parents usually do not show up at a preschool asking about DPP or UPK, they go to the school looking to enroll their child and then ask how they will be able to afford the tuition. This is typically when providers inform them about DPP and UPK and, as they move through the enrollment process, answer parents’ questions. This process of informing families about UPK by answering their questions is unstructured, and therefore less likely to be consistent across provider or parent experiences. It also means that providers typically are not set up to provide parents with a full and consistent explanation of the relationship between UPK and DPP. Two non-DPP providers also shared that their experience is that parents do not ask about UPK or DPP, instead, they ask if there were any funding opportunities that would help them lower and afford the cost of tuition. Working with providers to ensure they have access to succinct, consistent messaging about the relationship between the programs could help ensure that DPP parents are more consistently informed over time.

Most providers in APA’s focus groups mentioned that they do their best to help parents complete their applications and troubleshoot when issues arise, although this is challenging for preschool staff. Several parents mentioned struggling with completing their applications and ensuring their children were actually enrolled in school. One of them reported having completed the application, but close to the beginning of the school year she found out that her child was not registered; when she sought help from DPS to resolve the problem, she learned that she had

completed either the DPP or the UPK application but not the school application; she did not know she also had to complete a school application for her child every year.

Providers in APA’s focus groups indicated that even when parents have been told they need to complete applications for each program, DPP and UPK, to get full financial benefits, many of them continue to confuse DPP with UPK, or believe they are the same program. It also happens that when parents are encouraged to enroll in one program, they frequently respond that they are already enrolled, without realizing they have only enrolled in the other program. Having families enrolled in DPP benefits not only the family, but the preschool also benefits from DPP support. In addition, once families get the financial benefit of the programs, they often enjoy the school more as shared by one of the providers, “Once [families] get enrolled and they see the financial benefit, then they enjoy our school more because it costs less.” (NW, DPP community-based provider).

Some parents who participated in the focus groups indicated that they knew that DPP and UPK were not the same program, others mentioned they did not know if they were the same or different. A few parents said they did not know what UPK was at all. Very few focus group participants shared that DPP is a program for Denver families, while UPK is a program for Colorado. Although all focus group participants knew they were receiving financial support to cover their child’s preschool tuition, some of them did not know who was paying for the tuition, DPP or UPK. When asked to explain their understanding of how the two programs were related, most parents reported that they did not know how DPP and UPK were different, if there was a relationship between them, and what that relationship might be. One parent said that UPK is the general program and DPP is available as a secondary program for assistance.

Many parents also were very confused about the relationship and/or differences between DPS, UPK, DPP, and school choice. During focus group conversations some parents mentioned DPS when asked about DPP, and sometimes talked about the relationship between DPS and UPK, instead of DPP and UPK. A Spanish speaking parent of a 3-year-old child mentioned that she was interested in enrolling her child in DPP but did not understand whether students in DPS could receive financial support only from UPK, and indicated she believed many parents do not enroll in preschool at all and instead wait to enroll their children until kindergarten because they do not know they can be enrolled when they are 3 years old.

These findings are supported by data collected through the online surveys administered to parents of 3- and 4-year-old children enrolled in DPP. Figure 1.5. shows that high percentages of parents of 4-year-old children do not understand or understand very little of five out of six aspects of the relationship between UPK and DPP and the funding these programs provide. The lowest level of understanding was around the topic of what the qualifications are for children to receive DPP and UPK funding for which 72% of respondents indicated they did not

understand or understood very little about the qualifications. Parents also indicated low understanding of the relationship between DPP and UPK (68%), whether all preschool providers in Denver are providers in both DPP and UPK (64%), and the amount of funding families can receive from DPP and UPK (59%).

The only item that more than half of parents (52%) indicated they understood well or very well was whether DPP and UPK were the same or two different programs. This was corroborated by parents’ comments during focus group sessions, where parents mentioned they knew DPP and UPK were two different programs. Again, however, this indicates that nearly half of parents (48%) do not understand that these are two different programs.

Figure 1.5. Percentage of families of 4-year-old children reporting their understanding of various aspects of DPP and UPK

When parent survey responses were mapped using GIS mapping, the data revealed some interesting potential patterns. For instance, as shown in Figure 1.6 below, there appear to be a higher concentration of parents in the Far Northeast region of the city who either do not understand (shown by grey dots) or understand very little (shown by red dots) whether families can receive tuition support from DPP and UPK at the same time.

Figure 1.6. Family Survey Question: Please rate your level of understanding of whether families can receive tuition support from DPP and UPK at the same time

Similarly, patterns can be observed across regions of the city when examining GIS mapping of family survey data from the survey question asking families to rate their level of understanding of whether DPP and UPK are the same or two different programs. As shown in Figure 1.7 below, concentrations of red dots indicating low levels of family understanding on this topic can be seen particularly in the Far Northeast and Northwest regions of the city.

Figure 1.7. Family Survey Question: Please rate your level of understanding of whether DPP and UPK are the same or two different programs

Parents of 3-year-old children receiving DPP tuition credits also rated their level of understanding of the same DPP and UPK aspects. Interestingly, the parents of 3-year-olds indicated higher levels of understanding than parents of 4-year-olds for each aspect as shown in Figure 1.8. The item that received the highest level of understanding from both groups of parents was Whether DPP and UPK are the same or two different programs (52% for parents of 4-yearolds and 72% for parents of 3-year-olds), while Understanding the relationship between DPP and UPK was the least understood by parents of 3 year olds (56%), and second least understood by parents of 4-year-old children (68%). The aspect with the greatest difference in level of understanding was the Children’s qualifications to receive DPP and UPK funding reported as well or very well understood by 28% and 52% of parents of 4- and 3-year-old children, respectively. These data, supported by similar providers’ comments in focus groups, indicate that, overall, families receiving DPP tuition credits are mostly unfamiliar with important aspects of DPP and UPK, suggesting that they would benefit from learning more about the programs. It is reasonable to infer that, if parents who are DPP participants do not know much about it, other parents not in the program may still be less knowledgeable about it and possibly less likely to benefit from this important funding. Figure 1.8. shows additional details on these data.

Figure 1.8. Percentage of families of 3-year-old children reporting their understanding of various aspects of DPP and UPK.

Awareness of DPP because of media on UPK

There is almost total consensus among providers that the intense media coverage of UPK has attracted families to enroll their children in preschool. Most parents, they explained, are not knowledgeable about DPP or UPK, but they have heard that UPK would make preschool affordable to them, and this has encouraged them to enroll their children, even when they do not know how to get the financial assistance, or how UPK operates or specifically applies to them. On the other hand, neither of the two non-DPP providers interviewed reported experiencing increased interest in their programs because of the UPK media coverage.

A community-based provider shared that their center has seen an increased number of families interested in preschool and touring the school because of their awareness of UPK; they shared how important this financial assistance has been for the community they serve,

“Now we're able to serve more of our community from Montbello having UPK just being announced everywhere. So, we definitely got a lot of families interested that were not interested before because they can't afford it.” (FNE, DPP community-based provider).

Providers also mentioned that for many parents, preschool is the entry point to the education system, and they are very unaware of programs and services available to them,

“I think with preschool being the entry point of education for families, 80% of our families are coming in completely blind as to what's available to them because they're just so new.” (NE, DPP community-based provider).

Once families reach out to the preschool centers, it is up to providers to educate them about the programs, and this is when parents start learning about those services. One school-based provider explained it this way,

“That's when all of those terms start coming up to them, and quite frankly, they get overwhelmed like, “this is difficult to navigate!” And they don't know the questions to ask, like they're not asking because they don't know what to ask. They just want to know [how to get their child in school].” (SE, DPP school-based provider).

Providers indicated it is not uncommon that families have not heard about DPP, but noted there are differences in the family awareness levels about DPP and UPK, ranging from those who have never heard about the programs and just want their child in school, to those who have informed themselves through different avenues and are more knowledgeable about the school system and the registration process.

One school-based provider explained in APA’s focus groups that the main difference between families is their affluence and proceeded to describe affluent families as families that are more knowledgeable about the schools, about how UPK works, about the enrollment process and having to apply through UPK to get a spot in the school of their choice. According to providers, these families are more likely to be white, monolingual English speakers with more means. Less affluent families mostly rely on the school staff to help them work through the enrollment system and tend to focus on finding a school that is close to home; these families tend to be parents of color, sometimes multi-language learners who have a language other than English as their primary language. This provider explained,

“We say affluent, but we know in effect that it's more than just the money, it's the knowledge, it is the experience navigating systems. And some of these systems aren't as friendly to our multi-language families, it's not as user friendly to those who haven't been through the process before, or who have been proactive about researching what it takes to get students into preschool.” (SE, DPP school-based provider).

Finally, there were a few providers representing Catholic preschool centers participating in APA’s focus groups. These were preschools participating with DPP but not with UPK. They mentioned having several families with children enrolled in their centers or wanting to enroll in their centers interested in getting the UPK financial support; these families had asked why they could not get the UPK support. Providers mentioned that it was very difficult to explain to parents why their center was not with UPK and had to tell parents that it had to do with being a religious provider. Some told families that UPK had many regulations about religious

preschools, while others told them that they were still working with UPK on the logistics of becoming UPK providers.

Impact of UPK on DPP enrollment: The providers’ perspective

Most providers who participated in the focus groups reported a significant decrease in student enrollment in DPP during the 2023-24 academic year compared to previous years. One provider described the decrease as “drastic,” others as “significant.” Only a few reported a slight increase in families enrolling their children in DPP at their center and one did not see any difference in their enrollment numbers.

One school-based provider indicated the enrollment decrease at their preschool center was small due to the strong family outreach efforts they conducted with the help of their on-campus Head Start liaison who helped all families with their enrollment process. Although providers were not certain about the specific reason for the enrollment decreases they experienced, they mentioned that factors such as low birth rate, families moving out of Denver, issues with UPK registration, or a combination of those and other factors may have contributed to the decline. Providers that were not enrolled in UPK, including Catholic schools, saw different rates of decrease in enrollment and believed that families were migrating to preschools that allowed them to receive UPK funding, as one of them expressed,

“Especially for the schools like us that aren't a part of UPK, if you get a chance to take advantage of [UPK funding], then I understand why families would do it.” (NE, DPP community-based provider).

In general, providers attributed some enrollment challenges to the complexity of the UPK enrollment process that they indicated was especially burdensome for families that did not find the support needed to enroll. This barrier was identified as significant for non-English speaking families,

“I would attribute UPK as far as running a bit of interference. I think before UPK the process was much easier, much more accessible for families, all families, and especially families who … would otherwise qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, or qualify for DPP, or qualify for Head Start. With UPK it's been harder for families to navigate access to that system.” (SE, DPP school-based provider)

A community-based provider shared the different experience they had with DPP and UPK, and how UPK has taken away some of the control providers used to have over their own enrollment processes:

“DPP has no impact on my enrollment process, how I offer spots, how I reach out to families, how I enroll families, DPP isn't a factor. They wait until I've matched with the family and then the school and the family say, ‘Hey, DPP, we're matched, we'd like funding.’ Whereas UPK has taken that control out of our hands. And it's UPK that does

the matching and says you have to take this family, and we've had to change a lot of our policies around UPK enrollment whereas DPP never impacted our enrollment processes.” (NW, DPP community-based provider).

Providers mentioned several other possible reasons for how UPK might have impacted DPP enrollment, as well as issues that might have impacted preschool enrollment in general, including:

● Confusing DPP with UPK. Because many families confused DPP with UPK, they might have thought they were already enrolled or had completed all the paperwork when that was not the case, and they had only completed paperwork for one or other of the programs. As one provider stated, “When I approach them about DPP, they say I've already done this, I've already filled out the paperwork, I don't need to do this again.” (SE, DPP community-based provider).